Apple Vision Pro: Why This $3,500 Headset is Actually Dying

Remember when Apple Vision Pro launched in early 2024? The tech world collectively lost its mind. A $3,499 spatial computing device from the company that perfected consumer electronics. It felt inevitable—Apple would dominate mixed reality the same way they dominated phones, tablets, and wearables.

Except that's not happening.

And honestly? I'm not even surprised.

When you look beyond the marketing hype and the breathless tech press coverage, the Vision Pro tells a story we've seen before. An expensive product solving problems nobody has. A vision so narrow it excludes the actual market. A commitment so half-hearted that even Apple's legendary ecosystem advantage couldn't save it.

This isn't a conspiracy theory or pessimistic prediction. The data is already there. The reviews tell you what you need to know. The sales numbers speak louder than any press release. And most importantly, the actual use cases reveal something uncomfortable: Apple created a gadget, not a platform.

Let me walk you through what's actually happening with the Vision Pro, why it failed to dominate, and what this tells us about the broader AR/VR landscape in 2025.

The Vision Pro's Fundamental Problem: Solving Invisible Problems

The Vision Pro's core pitch is elegant. It's a $3,500 headset that lets you work in mixed reality, blend digital content with your physical environment, and access computing in a fundamentally new way. On paper, it sounds revolutionary.

In practice, it solves almost nothing that actually matters.

Here's the uncomfortable truth that Apple won't admit publicly: most people don't want to work in mixed reality. Your desk isn't magically improved by projecting screens into your field of vision. Your productivity doesn't skyrocket when you're wearing a ski goggle-sized device that costs more than a Mac Book Pro.

Apple discovered this the hard way. Early adopters—the people most likely to embrace new technology—found themselves in a peculiar situation. They had a $3,500 headset, but no software to justify the purchase. The default use cases presented by Apple boiled down to watching movies and using existing iPad apps in a virtual space.

That's not a platform. That's a very expensive way to watch TV and pretend you're working.

The problem isn't the technology itself. The Vision Pro's hardware is genuinely impressive. The display clarity is stunning. The hand and eye tracking work better than you'd expect. The processing power is legitimately fast. But impressive hardware without a reason to use it is just expensive jewelry.

And unlike jewelry, most people aren't willing to spend $3,500 on an item they'll use twice and then leave in a drawer.

Apple's track record suggests they understand this. The iPhone dominated because there was an immediate need: a better phone with an intuitive interface. The iPad succeeded because it found a role in specific workflows: creative professionals, students, casual users consuming media. The Apple Watch became essential because it solved the small problem of checking notifications without pulling out your phone.

The Vision Pro doesn't solve a small problem. It doesn't even solve a big problem. It creates its own problem, then offers itself as the solution.

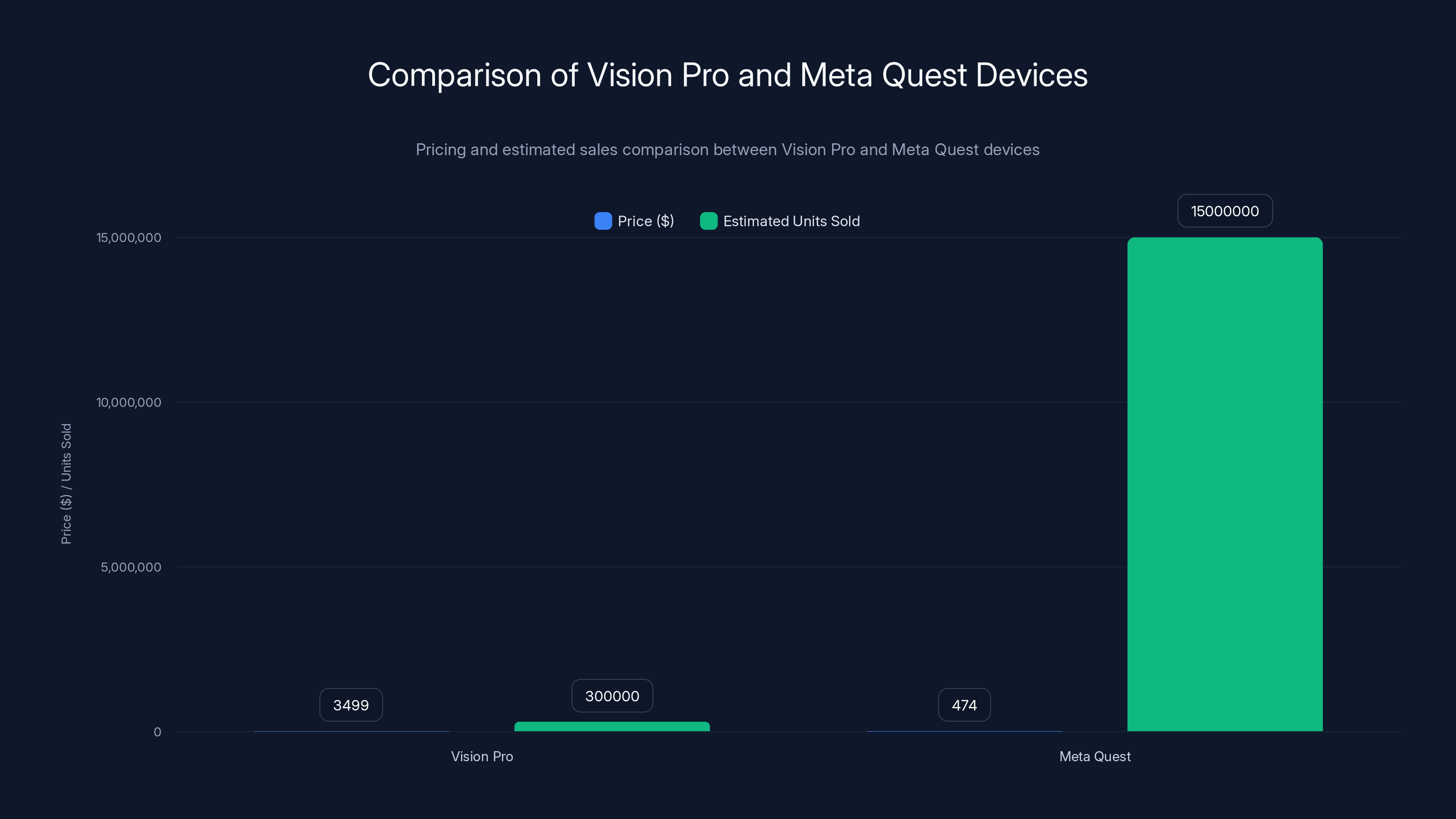

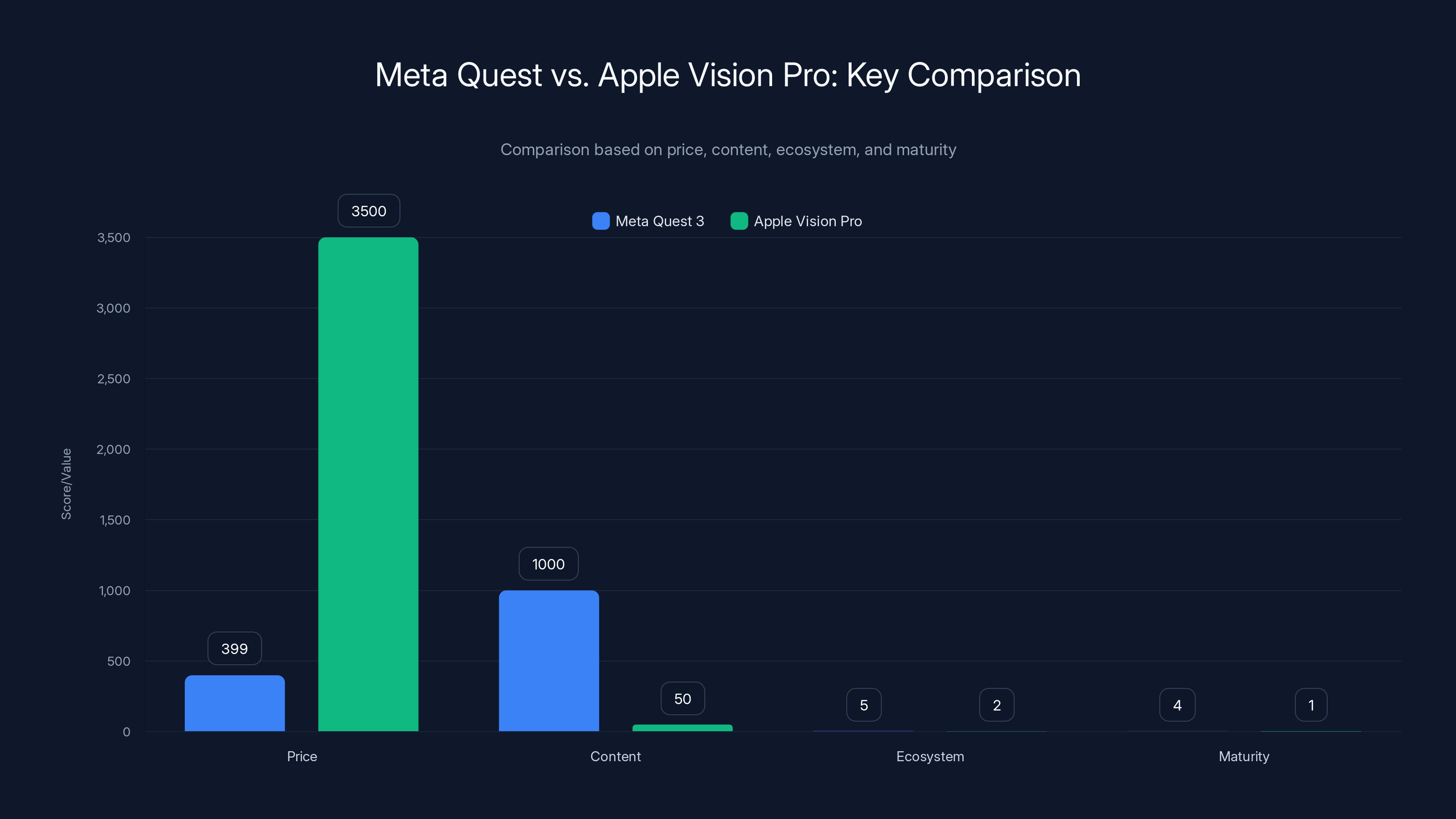

Meta Quest devices are significantly more affordable and have sold millions more units compared to the Vision Pro. Estimated data highlights the stark contrast in market performance.

The App Ecosystem Problem: Building Excitement from Nothing

When the Vision Pro launched, Apple faced a critical challenge: making developers actually build for it. This was the entire foundation of their strategy. The company needed a thriving ecosystem of native apps that would justify the $3,500 price tag and give users reasons to pick up the headset daily.

What happened instead was telling silence.

Developers weren't eager to rebuild their applications for a spatial computing interface. They weren't excited to create new experiences for a device with an unclear market size. And they certainly weren't interested in investing significant time and money into a platform with less than one million users.

This was the opposite of the iPhone launch in 2007. Back then, developers flocked to iOS because the market was clearly massive and growing fast. There was money to be made. There were users waiting.

The Vision Pro faced the reverse dynamic. The market was unclear. User demand was minimal. And dedicating resources to Vision Pro development meant pulling engineers away from platforms where they could actually reach customers.

Apple's own app store tells the story. Yes, there are Vision Pro apps. But most are either ports of existing iPad applications or tech demos that showcase the hardware rather than delivering actual utility. Looking at the available apps, you get apps for watching movies (which you could do on an iPad), viewing 3D models (neat, but specialized), and productivity software that mostly duplicates what desktop and tablet versions do.

The irony is that Apple's best shot at creating an app ecosystem came from this exact scenario: forcing developers to engage. They could have thrown money at developers. Offered revenue sharing guarantees. Subsidized development costs. Instead, they asked developers to build on faith.

Faith doesn't fund engineering departments.

Meanwhile, competitors were doing something different. Meta was investing aggressively in Quest content. Meta Quest devices cost

Apple broke this flywheel before it could start spinning.

The app ecosystem problem isn't just about available software. It's about the fundamental economics of platform development. When a company releases a device this expensive with such an unclear use case, developers understandably hesitate. The Vision Pro's app situation today—sparse, uninspired, mostly existing ports—is exactly what you'd expect from a platform nobody's sure will survive.

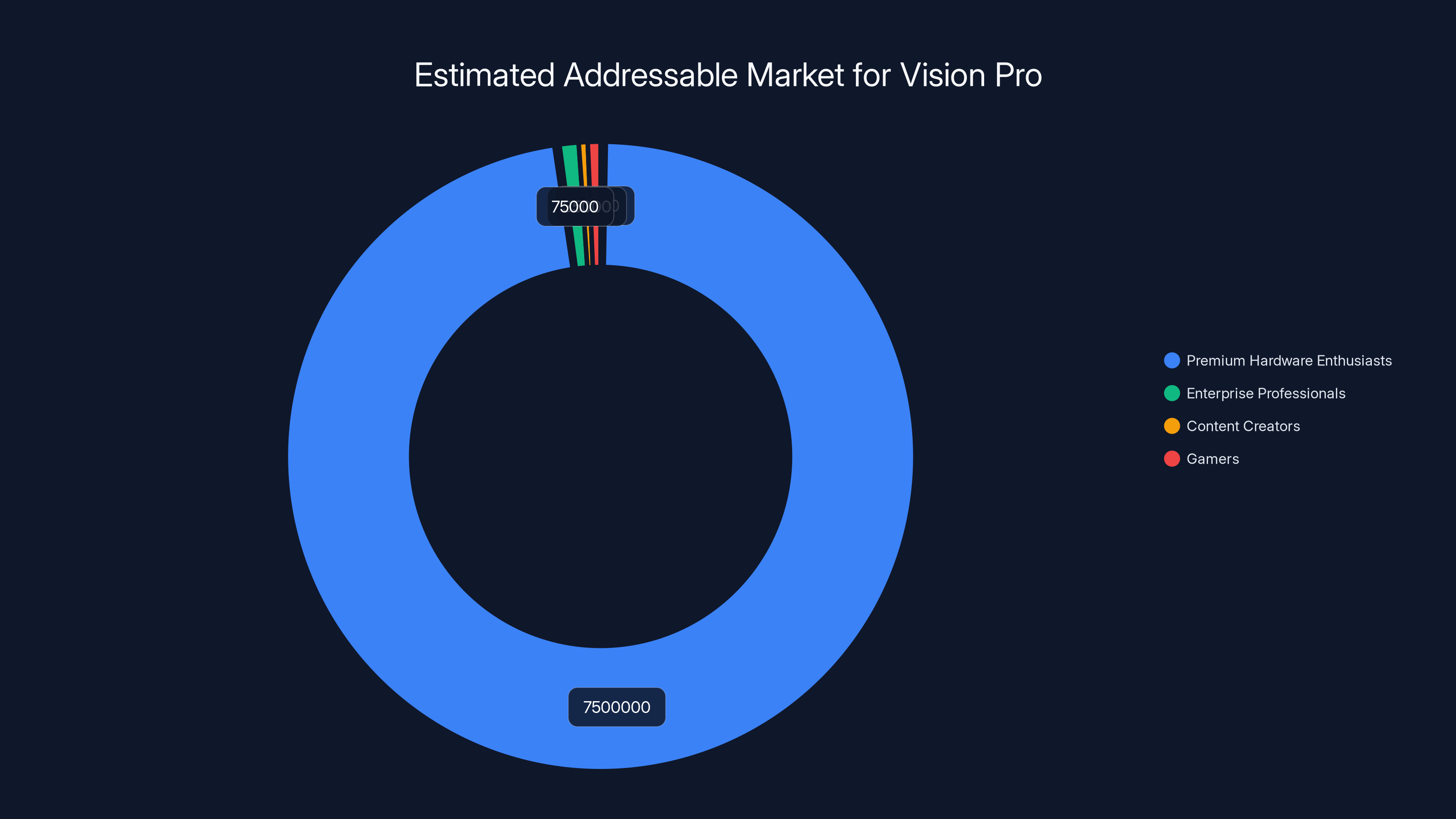

Estimated data shows that premium hardware enthusiasts form the largest segment of the Vision Pro's addressable market, followed by enterprise professionals, content creators, and gamers.

The Market Size Problem: Who Actually Buys a $3,500 Headset?

Let's talk numbers, because the Vision Pro's sales figures tell a story nobody at Apple wants to discuss.

Estimates suggest Apple sold somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000 Vision Pro units globally in the first year. For context, Apple sells roughly 230 million iPhones annually. Samsung's Galaxy Z Fold and Z Flip fold phones—niche products by any standard—sell more units than the Vision Pro manages in a month.

Apple's own Watch platform sells roughly 30 million units per year. The Vision Pro is tracking at less than 2% of Watch sales volume.

Even more telling: these aren't global sales. The Vision Pro is available in a handful of countries. Availability in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, and a few European nations means it's missing roughly 80% of the world's wealthier populations.

Why so limited? The cynical answer is that Apple knows the addressable market is tiny. The market for a $3,500 spatial computing device that doesn't solve any critical problem is inherently small. Expanding availability wouldn't fix this—it would just make the low adoption more visible.

Here's the actual addressable market breakdown:

Premium hardware enthusiasts: People willing to pay top dollar for new technology. Maybe 5-10 million people globally who fit this profile AND have the disposable income.

Enterprise professionals: Companies that might purchase Vision Pro devices for specialized tasks. Architects, engineers, medical professionals. Realistically, maybe 50,000 to 100,000 units worldwide annually across all enterprise use cases.

Content creators: Filmmakers and artists exploring spatial video and 3D environments. Perhaps 20,000 to 50,000 potential units annually.

Gamers: People excited about immersive gaming experiences. The market exists here, but Meta Quest has already claimed most of this audience, and they're doing it at 1/6th the price.

Add these up, and the total addressable market for Vision Pro looks closer to 500,000 to 1 million units annually—globally. And that's being generous.

Apple's annual revenue is roughly $391 billion. The Vision Pro division contributes less than 0.1% of that. For a company of Apple's scale, platforms need to be multi-billion dollar opportunities. The Vision Pro simply cannot reach that scale given its fundamental constraints: absurd pricing, unclear use cases, and limited market demand.

Apple's problem isn't market timing or market skepticism. It's that they've priced the Vision Pro out of the market that actually exists.

The Price Problem: Why $3,499 Is Fundamentally Wrong

Let's be direct: the Vision Pro costs too much.

I understand Apple's thinking. Premium hardware. Advanced display technology. Cutting-edge processors. Custom silicon. This is what Apple does—they charge premium prices for premium products. And people pay.

Except they won't pay when the value proposition is this unclear.

The iPhone cost

The Vision Pro costs

The Vision Pro doesn't replace anything. It doesn't add to your workflow in ways that justify the cost. It's additive, not transformative.

Apple has sold some units to wealthy early adopters and professionals with specific use cases. But the Vision Pro is proving what economists have known forever: demand curves slope downward. Make something more expensive, and fewer people want it. Make it

Could Apple reduce the price? Sure. But here's the catch: the Vision Pro's bill of materials (the actual cost to manufacture) is estimated between

Wait—so $3,499 is double what the company needs to charge just to hit normal margins.

This suggests Apple's pricing strategy isn't based on cost recovery or margin targets. It's based on something else: positioning the device as premium, limiting supply to artificial scarcity, and maximizing per-unit profit rather than total platform profit.

This strategy works great for luxury goods. It doesn't work for computing platforms.

The Vision Pro's launch price of $3,499 is significantly higher than previous Apple products, yet its perceived value is lower, indicating a mismatch in pricing strategy.

Enterprise Adoption: The Last Viable Argument

Apple's final hope is enterprise. Maybe the Vision Pro won't become a consumer phenomenon, but perhaps companies will buy thousands of units for training, collaboration, and specialized tasks.

This is theoretically plausible. Enterprise buyers care less about price and more about utility. If the Vision Pro could genuinely accelerate surgeon training or architectural visualization or collaborative design, companies would pay $3,500 per unit.

But here's what's actually happening: enterprise adoption is moving at a snail's pace.

Yes, there are pilot programs. Harvard's medical school conducted Vision Pro training pilots. Some architecture and design firms are experimenting. But these are experiments, not deployments. Companies aren't buying Vision Pro units in bulk. They're testing them in small numbers, evaluating whether the technology actually delivers benefits, and—in most cases—deciding to stick with existing solutions.

Why? Because specialized enterprise applications often have better alternatives. Surgeons training with mixed reality can use dedicated surgical simulation systems, many of which offer better fidelity and more refined workflows than the Vision Pro provides. Architects designing in 3D can use professional CAD software on high-end workstations, which offers more precise control and better performance.

The Vision Pro works okay for both applications. It doesn't work better than the specialized alternatives that already exist.

Moreover, enterprise deployments require ecosystem thinking. A company buying 500 Vision Pro units needs support, custom software, fleet management, repair services, and a commitment from the hardware manufacturer that the product will remain available and updated. Apple's track record with the Vision Pro—minimal software updates, unclear roadmap, already signal that this isn't happening.

Companies investing in large-scale Vision Pro deployments are essentially betting on a platform that might be discontinued in three years. That's not a bet most enterprises are comfortable making.

The enterprise opportunity was real. But Apple squandered it by treating the Vision Pro as a consumer product first and only considering enterprise as an afterthought. Successful enterprise platforms are purpose-built. They're designed around specific workflows. They're supported with dedicated sales teams and customization services.

The Vision Pro is a consumer device that some businesses might use. That's a fundamentally different thing.

The Software Roadmap Problem: Where's the Vision?

Here's where it gets genuinely frustrating. The Vision Pro's biggest problem might not be hardware or pricing—it might be that Apple hasn't articulated what this device is actually for.

Since launch, Apple's vision for spatial computing has been remarkably vague. "A new category of personal computing" is the phrase they've settled on. But what does that mean in practice?

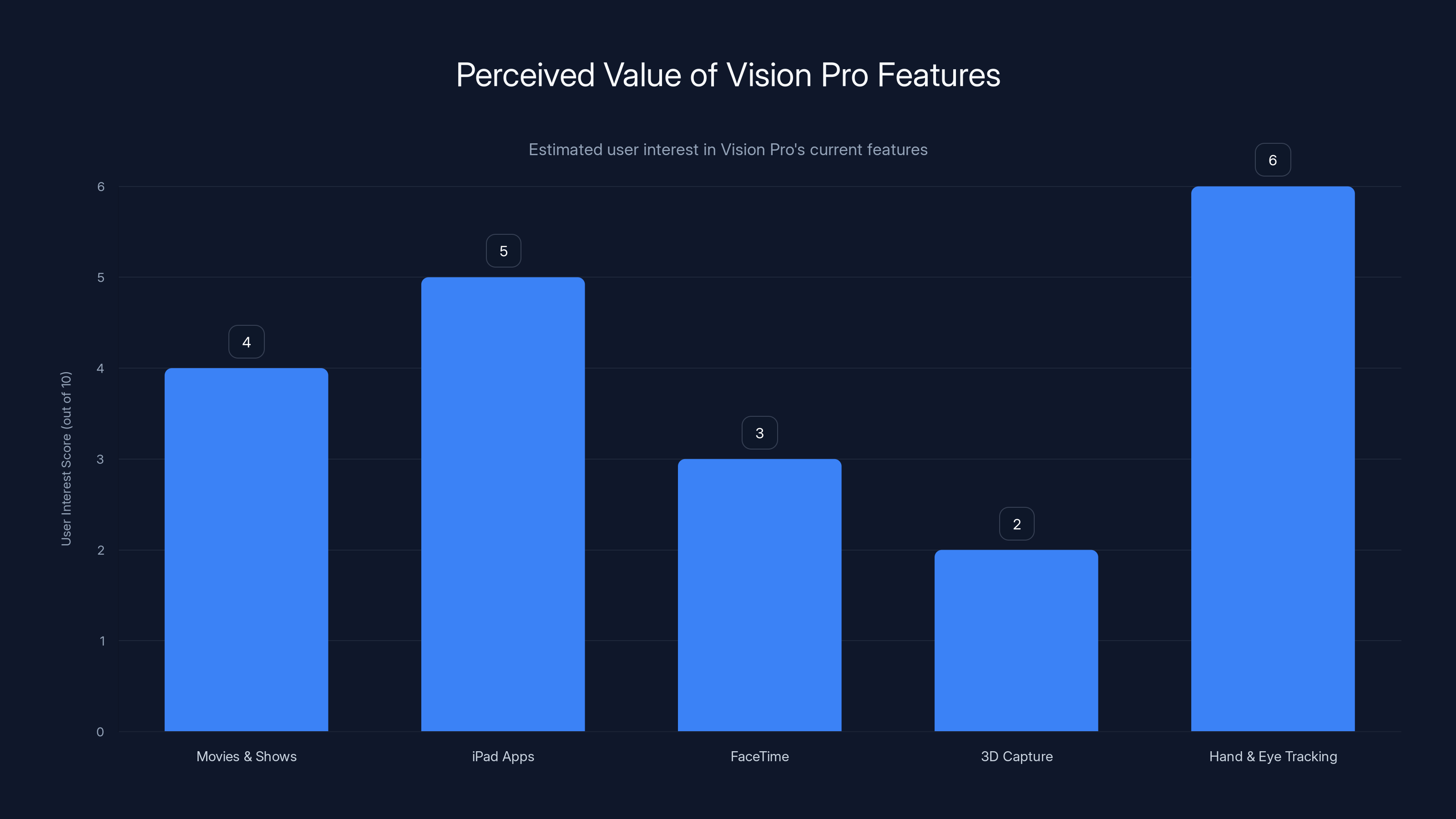

We've seen:

- Movies and shows on your headset (that's just existing media in a new format)

- iPad apps scaled up to a bigger screen (that's existing software)

- FaceTime with spatial audio (nice, but not essential)

- 3D photo and video capture (interesting for 0.1% of users)

- Hand and eye tracking to replace controllers (cool technology, but does it improve anything?)

There's no killer app. No software experience that makes someone say, "I have to have this." There's no roadmap showing where spatial computing goes next. There's no narrative that suggests Apple has a clear vision beyond "we made a really expensive headset with impressive hardware."

Compare this to the iPhone. In 2007, Steve Jobs showed the vision: a device that was a phone, an email machine, and an internet device. That vision felt concrete. The execution was limited at first—no third-party apps, no copy and paste—but the destination was clear.

The Vision Pro has no equivalent clarity. Apple shows you the headset, then asks you to imagine what you might do with it. That's not a vision. That's asking customers to justify a $3,500 purchase based on speculation.

Without a clear software roadmap, developers can't build. Without developer momentum, the ecosystem doesn't improve. Without an improving ecosystem, users have fewer reasons to buy. This is a self-reinforcing downward spiral, and the Vision Pro is already trapped in it.

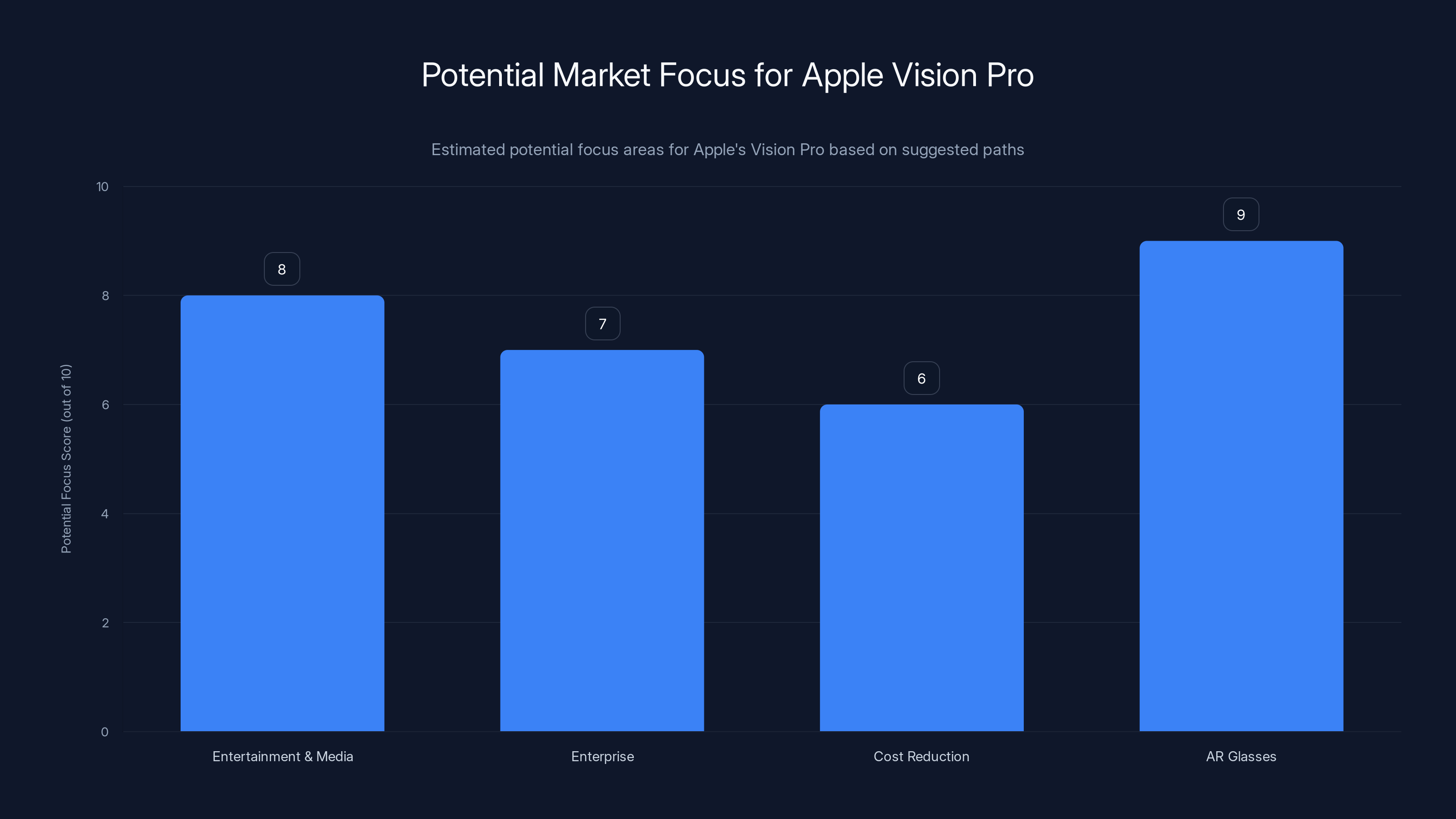

Estimated data suggests AR glasses and entertainment/media focus could have been stronger market strategies for Apple Vision Pro.

Meta Quest's Dominance: The Real Competitor Nobody Talks About

The thing nobody wants to admit is that Meta Quest already won the VR market.

Apple positioned the Vision Pro as something different—spatial computing, not VR. And technically, they're right. The Vision Pro passes through video of your surroundings. Quest devices are fully immersive VR. But in practice, consumers don't care about this distinction.

What consumers care about is:

- Price: Meta Quest 3 costs 3,500.

- Content: Quest has thousands of games, apps, and experiences. Vision Pro has dozens.

- Ecosystem: Meta has invested billions in VR development, studios, and exclusive content. Apple has offered conditional support and vague gestures toward developers.

- Maturity: Quest devices are in their fourth iteration with proven reliability and constant software improvements. Vision Pro is first generation with no roadmap.

- Clear use case: VR gaming and entertainment are proven markets. Spatial computing as Apple frames it is still speculative.

Meta has sold roughly 15 million Quest headsets since launching the platform. That's 30-75x more units than the Vision Pro has managed in its first year. Meta's platform generates substantial revenue, attracts genuine developer interest, and has created an actual market for VR experiences.

Apple created the Vision Pro but hasn't created a market.

The frustrating part for Apple is that they could have dominated this space. Their brand power is enormous. Their design expertise is unparalleled. Their ability to drive adoption is legendary. But they entered the market at the wrong price point, without a clear use case, and with an implicit assumption that being Apple would be enough.

It wasn't.

The Return Rate Secret: What the Data Actually Shows

There's a number Apple won't discuss publicly: the Vision Pro return rate.

According to various reports and retailer statements, a significant percentage of Vision Pro units purchased are being returned within the standard return windows. Some estimates suggest return rates approaching 50%, which would be catastrophically high for Apple.

Normal Apple hardware sees return rates of 3-5%. Even products that underperformed commercially typically see returns under 10%. The Vision Pro's suspected return rate suggests something worse than typical product failure.

It suggests the product doesn't deliver on its promises to actual users.

When someone buys a Vision Pro, they're likely expecting one thing: a revolutionary computing experience that justifies the $3,500 price. What they actually get is expensive hardware with limited software, unclear use cases, and the uncomfortable realization that they've spent more money than a MacBook Pro on something they're not sure they need.

After two weeks of using it, many buyers apparently decide they don't need it. They return it. Lesson learned: expensive gadget ≠ computing platform.

High return rates are devastating for consumer electronics platforms. They signal to retailers that demand is soft. They damage resale value (used Vision Pro units are flooding secondhand markets at steep discounts). They reduce word-of-mouth recommendation rates. And they signal to potential buyers that existing users aren't satisfied.

This is the death knell for a luxury product. When the wealthy early adopters who can afford to buy anything decide a device isn't worth keeping, the platform's credibility collapses. If the Vision Pro isn't compelling to people with unlimited budgets, why would anyone else buy it?

Estimated data suggests that hand and eye tracking generate the most user interest, while 3D capture is the least compelling feature.

What Apple Got Right (But It Wasn't Enough)

To be fair, the Vision Pro isn't a complete failure. There are aspects of the hardware and experience that genuinely impress.

The display quality is legitimately stunning. The micro-OLED displays deliver clarity and color accuracy that makes watching content on the Vision Pro genuinely engaging. If Apple had priced this at $1,500 and marketed it primarily as a premium entertainment device, they might have found a viable niche market.

The hand and eye tracking actually works. This is harder than it sounds. Apple spent years perfecting eye tracking, and it shows. The responsiveness is fast. The accuracy is reliable. And it genuinely feels better than holding controllers.

The industrial design is exceptional. The headset is beautifully made. The curved glass, the aluminum frame, the fabric bands—everything feels premium and deliberately crafted. This is Apple doing what they do best: making expensive products that feel worth their price tag. The exterior, at least, justifies some of the cost.

The performance is snappy. Apple's custom M2 and R1 chips power the headset, and it shows. There's no lag when you're interacting with spatial UI. Apps load quickly. The frame rate is high and consistent. Performance isn't the problem.

Spatial audio and the external display are cool. Being able to see the person wearing the headset through the external display is clever. Spatial audio positioning actually enhances immersion in a way standard headphone audio doesn't.

But none of this is enough. Perfect hardware means nothing if there's no software. Beautiful industrial design doesn't matter if the device doesn't solve real problems. Exceptional performance doesn't drive adoption without compelling experiences.

Apple built a technically excellent device that addresses no actual market need.

It's like building the most beautiful chainsaw in the world and then selling it to people who don't need chainsaws. The craftsmanship is admirable. The engineering is impressive. The product is fundamentally pointless.

The Discontinuation Timeline: When Is Apple Pulling the Plug?

Let's talk about the inevitable end.

Apple won't announce that the Vision Pro is being discontinued. That's not their style. Instead, we'll see a slow fade. Production will quietly decrease. New hardware revisions will be delayed indefinitely. Software updates will become infrequent, then occasional, then stop.

Meanwhile, Apple will shift its narrative. "We're focusing on other areas of spatial computing," they'll say. Or: "The Vision Pro was part of an exploration that's now moving into different directions." The headset won't be dead, officially. It'll just be... done.

Historically, Apple's bad hardware decisions follow predictable patterns:

Years 1-2: Launch with optimistic marketing, announce ambitious plans, suggest this is just the beginning of a new era.

Years 2-3: Realize the market is smaller than expected, issue modest updates, quietly reduce marketing spend.

Years 3-4: Stop mentioning the product in earnings calls, phase out retail presence, shift to "Apple is exploring" language instead of "Apple has built."

Years 4-5: Final discontinuation notice buried in corporate filings, focus on next big thing.

The Vision Pro is currently somewhere between Year 1 and Year 2 of this cycle. Apple is still defending the product publicly, still suggesting it's the future of computing. But internally, the narrative is probably shifting.

My estimate: the Vision Pro reaches end-of-life status (no new units produced, limited support for existing units) by 2026 or 2027. Apple will have moved on to something else by then. Spatial computing might still be part of Apple's long-term vision, but it won't involve the Vision Pro.

The question isn't whether the Vision Pro will be discontinued. The question is how long Apple will pretend it's a strategic priority while that's happening.

Meta Quest 3 outperforms Apple Vision Pro in terms of price, content availability, ecosystem development, and maturity. Estimated data for content and ecosystem scores.

What This Means for AR/VR Technology Going Forward

Here's what's genuinely important about the Vision Pro's failure: it suggests that the AR/VR revolution isn't happening on the timeline anyone predicted.

For the past 15 years, venture capitalists, tech journalists, and futurists have insisted that AR/VR is the next major computing paradigm. Virtual reality will revolutionize entertainment! Augmented reality will transform how we work! Spatial computing will replace traditional monitors!

The Vision Pro was supposed to be the harbinger of this future. Instead, it's becoming a cautionary tale.

The uncomfortable truth is that humans have successfully optimized for how we interact with computers over the past 40 years. Keyboards, mice, touchscreens—they're boring and familiar, but they work. Introducing radically new interaction paradigms (spatial computing, full immersion VR) creates friction and requires solving new problems you don't have with existing interfaces.

Is spatial computing better than a monitor? Maybe, for some applications. But it's also bulkier, heavier, requires more computation, drains battery faster, and creates ocular fatigue. For 95% of computing tasks, a monitor and keyboard are still superior. The Vision Pro doesn't change this calculus.

What the Vision Pro's failure tells us is that killer apps for spatial computing either don't exist yet or aren't compelling enough to drive mass adoption. Gaming is the one AR/VR space showing promise (Meta Quest gaming is thriving), but that's because immersive entertainment benefits from full immersion in ways productivity software doesn't.

The next major computing paradigm probably exists. But it might not arrive by 2025. It might require different hardware than the Vision Pro. It might come from an unexpected direction. And it definitely won't come from asking people to pay $3,500 for a device without clear use cases.

Apple was right that spatial computing is interesting. They were just wrong about whether the world is ready to buy it yet.

The Broader Lesson: Why Expensive Gadgets Fail Without Clear Use Cases

The Vision Pro isn't the first expensive Apple product to fail. It's just the most recent and most expensive.

The Apple Watch was derided as useless in 2015. Smartwatches, critics argued, solve no real problems. You already have a phone. Why would you pay $400 for a smaller screen that does less?

But Apple solved that problem. The Watch became genuinely useful for quick notifications, fitness tracking, and payment. It found a role in your daily life that justified the cost. Today, the Watch is a multi-billion dollar business for Apple.

The Vision Pro is the opposite trajectory. Apple released the product first, then tried to find problems it could solve. That's backward. Successful products solve clear problems. They're designed around specific use cases. They deliver obvious value.

The Vision Pro delivers vague potential.

This is the lesson Silicon Valley keeps learning and forgetting: consumers don't pay premium prices for technology. They pay premium prices for solutions. They buy iPhones because phones are essential, and the iPhone does phones better than competitors. They buy MacBooks because laptops are necessary, and Apple's execution is unmatched.

They don't buy $3,500 headsets to maybe, possibly, potentially experience computing in a new way. That requires much stronger proof points.

The vision was always there. Pun intended. Apple envisioned spatial computing as the future. The problem was delivering a product that made the vision tangible, affordable, and immediately useful. They failed at all three.

The Comparison to Failed Products: Why Some Get a Second Chance and Others Don't

Apple has killed plenty of products. The original Newton was a disaster. The Ping social network lasted five years and then vanished. Apple Maps launched broken and took years to become competitive. MobileMe was so bad it spawned iCloud as replacement.

But some products got a second chance. The Apple Watch seemed pointless until people realized it was useful. AirPods seemed ridiculous until they became ubiquitous. Apple TV seemed like a hobby project until it became a genuine revenue stream.

The question for the Vision Pro is: can it become useful like the Watch or AirPods? Or is it destined for the graveyard like Newton and Ping?

The signs suggest the latter. Here's why:

Utility for the Watch was immediate and obvious once delivered: After wearing a Watch for a day, you understand why it's useful. Glancing at notifications without pulling out your phone is genuinely convenient. Fitness tracking is inherently valuable. Apple didn't have to convince anyone of the value proposition—users felt it immediately.

Utility for the Vision Pro is abstract and speculative: After wearing it for a day, you're left wondering what you're supposed to do with it. Working in mixed reality isn't obviously better than working with existing tools. Watching movies isn't improved by a headset. The value proposition requires explanation, marketing, and faith.

The Watch's adoption curve was immediate: Apple sold millions of Watches from year one. Demand was instant. Retailers couldn't keep them in stock in early markets. This signaled that people wanted the product.

The Vision Pro's adoption curve is flat: Sales have plateaued well below expectations. Retailers don't struggle to keep them in stock. Nobody's camping out for availability. This signals indifference.

The Watch created its own category because the category didn't exist: Smartwatches existed before the Apple Watch, but the Watch redefined the category and made it actually useful. Apple didn't try to force an existing category—they evolved one.

The Vision Pro is trying to force spatial computing as a category when that category doesn't clearly exist: Apple is asking people to adopt a product category (spatial computing) that they didn't know they needed. That's much harder than refining an existing category.

The Vision Pro could potentially become useful if Apple's software roadmap suddenly revealed killer applications. But the track record so far suggests that's not happening. Apple is building a headset and hoping developers will figure out what to do with it. That's not a strategy for success.

Where Apple Should Have Gone Instead

This is the frustrating part. There were viable paths for Apple in spatial computing that would have actually worked.

Path 1: Release a $1,500 version focused on entertainment and media consumption. Market it as a premium TV and movie device. Deliver excellent spatial video content. Dominate the premium home entertainment space. This is defensible, profitable, and actually matches the product's strengths.

Path 2: Build a $1,000 version for enterprise first. Focus exclusively on doctors, architects, engineers, and designers. Build software around their actual workflows. Create support and customization services. Prove value in enterprise before trying consumer markets.

Path 3: Wait until the technology cost less. Hold off on launching until the hardware could be delivered at

Path 4: Release AR glasses instead of VR headset. Build something lighter and more socially acceptable. Focus on mobile AR applications rather than spatial computing. This aligns better with how people actually want to use technology.

Apple chose none of these paths. Instead, they chose premium positioning, vague use cases, and a price that kills demand. It's like they wanted the product to fail.

Except that's not fair. Apple clearly believed in spatial computing. The team that built the Vision Pro put genuine effort and innovation into the hardware. This wasn't a cynical cash grab. It was a vision that missed the market.

Which might be the most important lesson: having a great vision and amazing engineering isn't enough. You also need to understand your actual market, price appropriately, and deliver clear value propositions.

Apple is generally excellent at all three. The Vision Pro is the exception that proves the rule.

The Bottom Line: What Happens Next

Here's my prediction for the Vision Pro's trajectory through 2027:

2025: Continued modest sales, but no growth. Apple continues defending the product publicly while quietly staffing down Vision Pro dedicated teams. Marketing budget shifts elsewhere.

2026: Sales flatline or decline. Apple announces a second-generation Vision Pro, hinting at improvements and addressing criticism. In reality, this is damage control signaling that the company hasn't abandoned spatial computing entirely.

2027: Second-gen Vision Pro launches at a slightly lower price point (

Post-2027: Vision Pro becomes a "legacy product" receiving minimal support and rare updates. Apple shifts to discussing spatial computing in abstract terms while moving investment to next big thing.

The Vision Pro won't be murdered. It'll be slowly abandoned while Apple pretends it was always a niche product serving niche needs. This is how Apple ends products that represent ambitious failures.

But here's the thing: Apple doesn't need the Vision Pro to succeed. Apple's business is healthy enough to absorb expensive failures. The company generates $400+ billion in annual revenue. Writing off the Vision Pro as a strategic loss is an acceptable corporate maneuver.

What matters is what Apple learns from this failure. If the company recognizes that spatial computing needs much stronger value propositions before mainstream adoption, that's valuable. If they understand that pricing matters and that "premium" doesn't mean detached from market reality, that's a lesson.

If they build the next product with clear use cases, reasonable pricing, and actual market understanding, the Vision Pro might become a useful failure—the kind that teaches important lessons.

But if Apple repeats the Vision Pro playbook with the next product category, then this becomes more than just one headset's failure. It becomes a sign that the company that once reinvented computing categories is losing its ability to understand markets.

That would be the real tragedy.

Will Runable or AI Automation Tools Change the Spatial Computing Landscape?

There's an interesting question lurking here: could AI-powered automation platforms like Runable eventually create compelling use cases for spatial computing?

Consider this scenario: Runable uses AI agents to automatically generate presentations, documents, reports, and images. What if spatial computing allowed teams to collaborate on these assets in three-dimensional space? What if you could visualize a data report as a spatial environment, manipulate variables in real-time, and see immediate results?

This is theoretically possible. But it's not what the Vision Pro currently enables. The platform would need to mature significantly, and developers would need to build entirely new spatial-first tools. We're talking years, not months.

For now, the Vision Pro and AI automation tools are living in separate worlds. Neither is currently helping the other solve its problems.

FAQ

Why is the Apple Vision Pro failing when Apple usually dominates product categories?

The Vision Pro fails where Apple typically succeeds because it's priced without a clear market need and solves problems nobody has. Apple dominates categories like smartphones and tablets because those products offer immediate, obvious utility. The Vision Pro offers vague potential. Additionally, Apple entered the spatial computing market at

What would need to happen for the Vision Pro to succeed?

The Vision Pro would need killer apps that make the value proposition obvious. Imagine software that genuinely improves professional work, entertainment, or daily life in ways existing tools cannot. You'd also need a significant price reduction (

How does the Vision Pro compare to Meta Quest devices?

Meta Quest devices cost

Is the Vision Pro an enterprise solution?

The Vision Pro could theoretically serve enterprise customers in specialized fields like medical training, architectural visualization, or engineering. However, adoption is moving extremely slowly. Companies are hesitant to invest heavily in a platform with an unclear future and no guarantee of long-term support. Specialized enterprise solutions already exist and often outperform the Vision Pro for specific workflows.

What are the rumored return rates for Vision Pro?

Various reports and retailer statements suggest Vision Pro return rates might approach 50% within standard return windows, which is catastrophically high compared to Apple's typical 3-5% product return rates. This suggests actual users find the product doesn't deliver on its promises, making it a warning sign for the platform's viability.

When will Apple discontinue the Vision Pro?

Based on Apple's historical pattern with failed products, discontinuation will likely occur between 2026-2027. The company won't announce an end of life publicly. Instead, production will quietly decrease, software updates will become infrequent, and marketing will shift away from the product. Apple will reframe its spatial computing ambitions in vaguer terms while moving investment elsewhere.

Could AI and automation change how we use spatial computing headsets?

Potentially, but not with current products. If AI platforms created specialized spatial-first applications that offered clear advantages over traditional interfaces, spatial computing could become more viable. This would require years of development and wouldn't help the Vision Pro's current problems. For now, AI automation and spatial computing remain separate technologies serving different markets.

What did Apple get right about the Vision Pro hardware?

Apple built technically excellent hardware. The micro-OLED displays deliver stunning clarity, hand and eye tracking works reliably, performance is snappy, industrial design is exceptional, and spatial audio adds genuine value. The hardware itself isn't the problem. The problem is that amazing hardware means nothing without software that gives people reasons to use it.

Could the Vision Pro succeed as a niche product?

Yes, the Vision Pro could survive as a premium niche product serving specialized professionals. But "niche product" is a very different thing from what Apple envisioned. They didn't design and price the Vision Pro as a niche tool. They positioned it as a new computing paradigm. If it ends up as a specialty device for 50,000-100,000 professionals worldwide, that's success—just not the success Apple wanted.

What can we learn from Vision Pro's failure?

The fundamental lesson is that technology companies need to understand actual market needs before pricing and positioning products. Apple excels when targeting clear needs (better phones, better laptops, better watches). The Vision Pro tried to create demand for a product category that doesn't clearly exist. That's a much harder problem, and it requires much more work to solve than Apple demonstrated with this product.

The Vision Pro won't explode in a dramatic failure. It'll fade quietly, replaced by newer initiatives while Apple pretends spatial computing remains a long-term priority. This is how billion-dollar companies end ambitious products that miss markets.

But the lesson endures: great hardware and Apple's brand are insufficient when fundamental product strategy is flawed. The Vision Pro proves that even the world's most successful technology company can misjudge a market.

The question isn't whether it's the end for Vision Pro. The data already answers that. The question is whether Apple learned anything from this expensive mistake.

Key Takeaways

- Apple Vision Pro's $3,499 price eliminates 85% of potential market demand, fundamentally breaking the addressable market economics

- Estimated 200k-400k first-year sales vs 15M+ for Meta Quest proves that pricing and clear use cases matter more than brand power

- The Vision Pro app ecosystem remains sparse because developers won't invest in a platform with unclear future and minimal user base

- High return rates (estimated near 50%) indicate the product doesn't deliver on its value proposition to actual users

- Enterprise adoption is failing because companies won't invest heavily in a platform lacking clear roadmap and long-term support guarantees

- Apple's strategic error was pricing for luxury positioning rather than market dominance—the opposite of their iPhone strategy

- The Vision Pro will likely be quietly discontinued by 2026-2027 as Apple shifts focus and investment to other initiatives

- Hardware excellence (display quality, tracking, design) cannot overcome fundamental problems with software, use cases, and market understanding

Related Articles

- Lego CES 2026 Press Conference: Live Coverage & Announcements [2025]

- CES 2026: Why AI Integration Matters More Than AI Hype [2025]

- Audeze Maxwell 2 Gaming Headset Review: Features & Pricing [2025]

- Samsung's CES 2026 AI Revolution: Complete Product Breakdown [2026]

- The End of Smartphones? How AI Wearables Will Reshape Computing in 2026 [2025]

- Amazon Ember Artline vs Samsung Frame: The Complete Comparison [2025]

![Apple Vision Pro: Why This $3,500 Headset is Actually Dying [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/apple-vision-pro-why-this-3-500-headset-is-actually-dying-20/image-1-1767636570352.jpg)