The Return to Lunar Exploration: Why Artemis II Represents a Turning Point

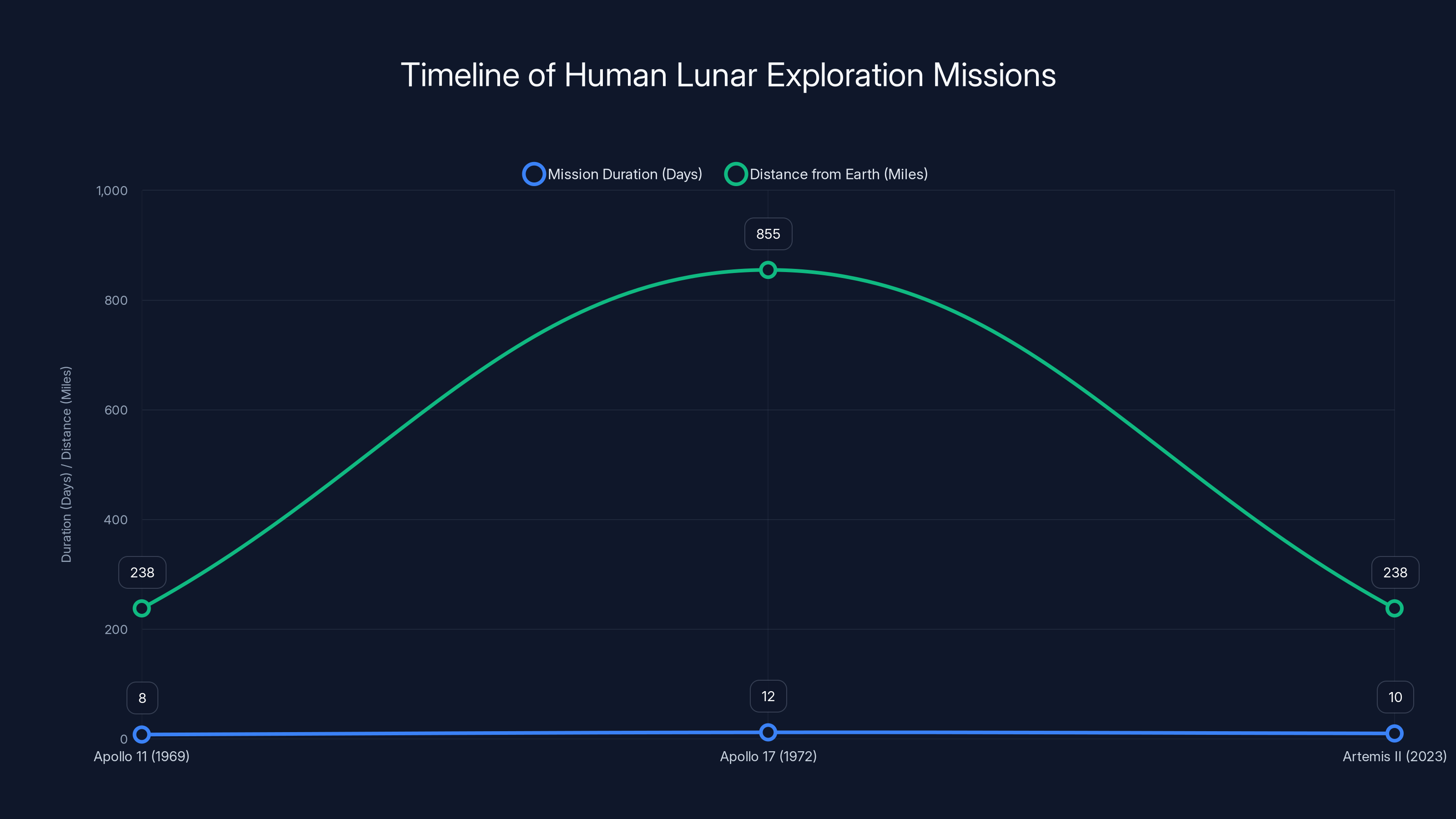

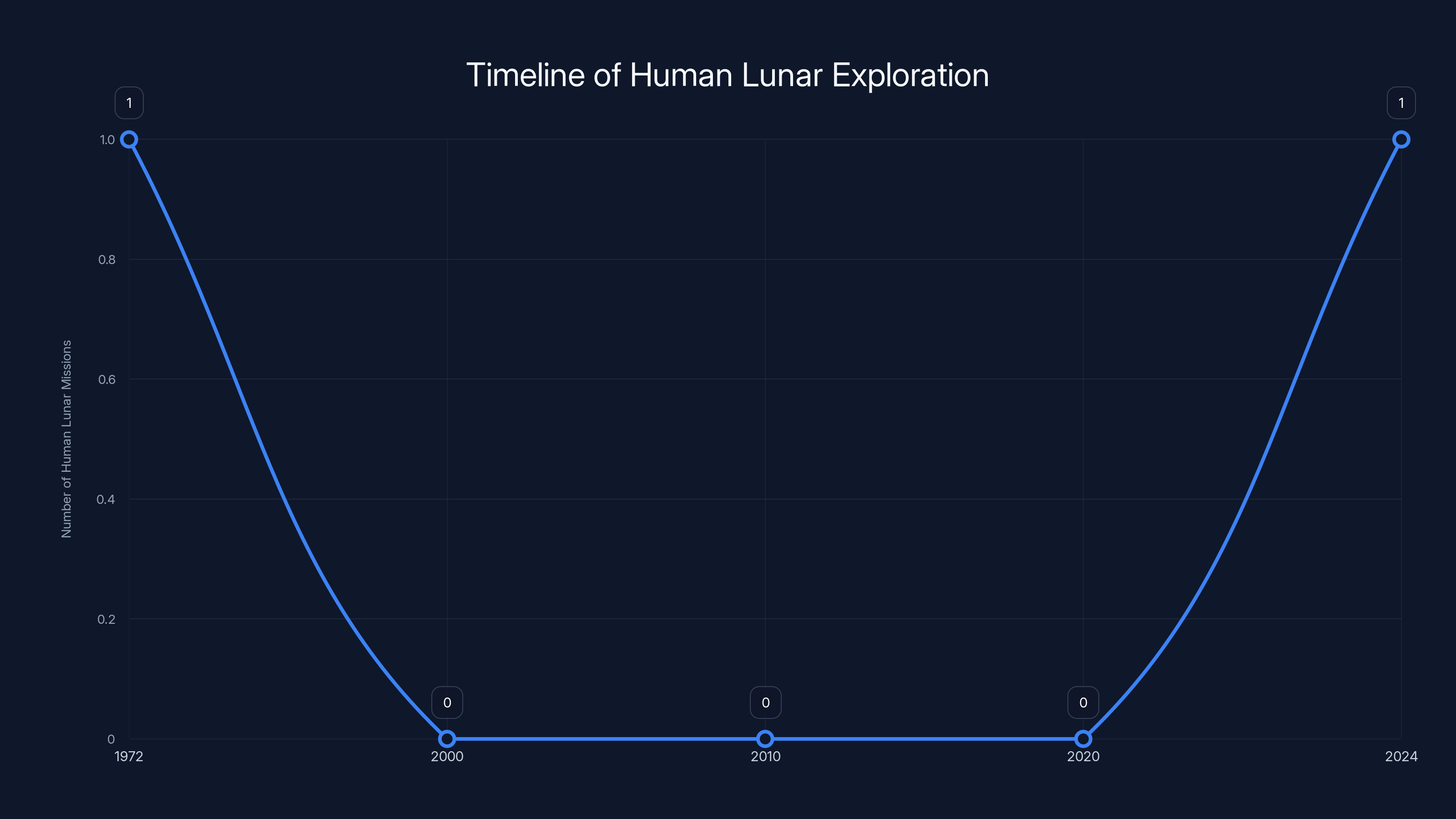

The last time humans walked on the Moon, disco was dominating the charts, the Vietnam War was ending, and the average new car cost less than $4,000. That was December 1972, during the Apollo 17 mission. For over five decades, Earth's natural satellite has remained visited only by robotic probes and landers. Now, after years of development, engineering challenges, and persistent delays, humanity is finally ready to make its way back.

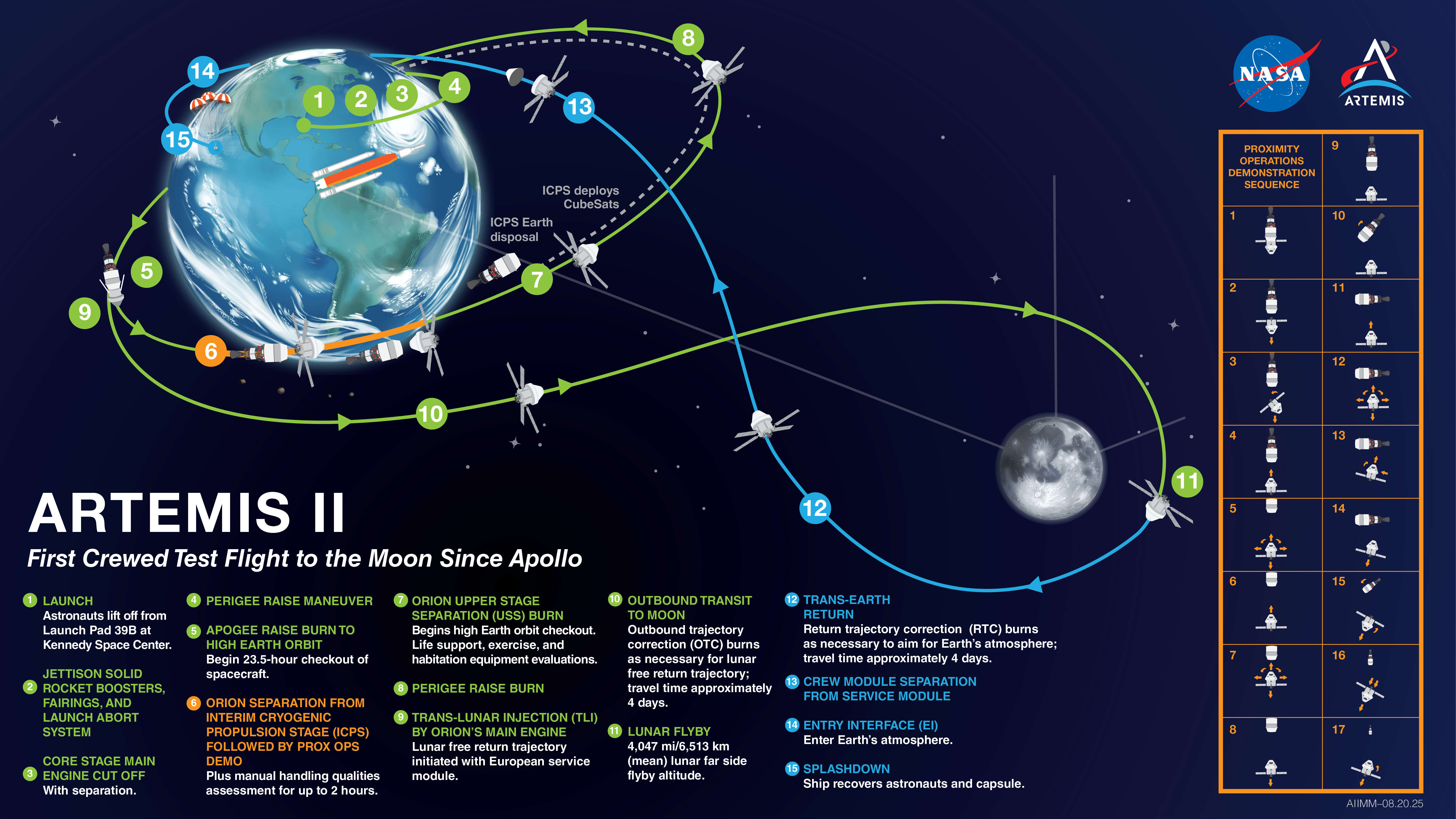

Artemis II isn't just another spaceflight. It represents NASA's commitment to restoring human presence beyond low Earth orbit and establishing the infrastructure for sustained lunar exploration. Unlike robotic missions that can take years to reach their destinations, this crewed spacecraft will accomplish its objectives in about ten days. The mission combines the latest advances in rocket propulsion, spacecraft design, life support systems, and autonomous navigation with lessons learned from fifty years of spaceflight operations.

What makes this mission particularly significant is what it achieves without actually landing on the lunar surface. The four astronauts will venture farther from Earth than any human in history, experience unprecedented velocities during atmospheric reentry, and conduct groundbreaking science and navigation experiments that will pave the way for future landing missions. They'll also demonstrate the reliability and capabilities of systems that future crews will depend on when establishing a permanent presence on the Moon.

The engineering and logistical effort required to reach this moment has been substantial. NASA's launch teams, contractors, and support personnel have worked methodically through countless technical challenges, integration processes, and safety reviews. Understanding what makes Artemis II possible requires examining the rocket that will carry it, the spacecraft that will protect the crew, the astronauts themselves, and the intricate dance of systems that must work flawlessly together.

The Space Launch System: Building a Rocket for Lunar Exploration

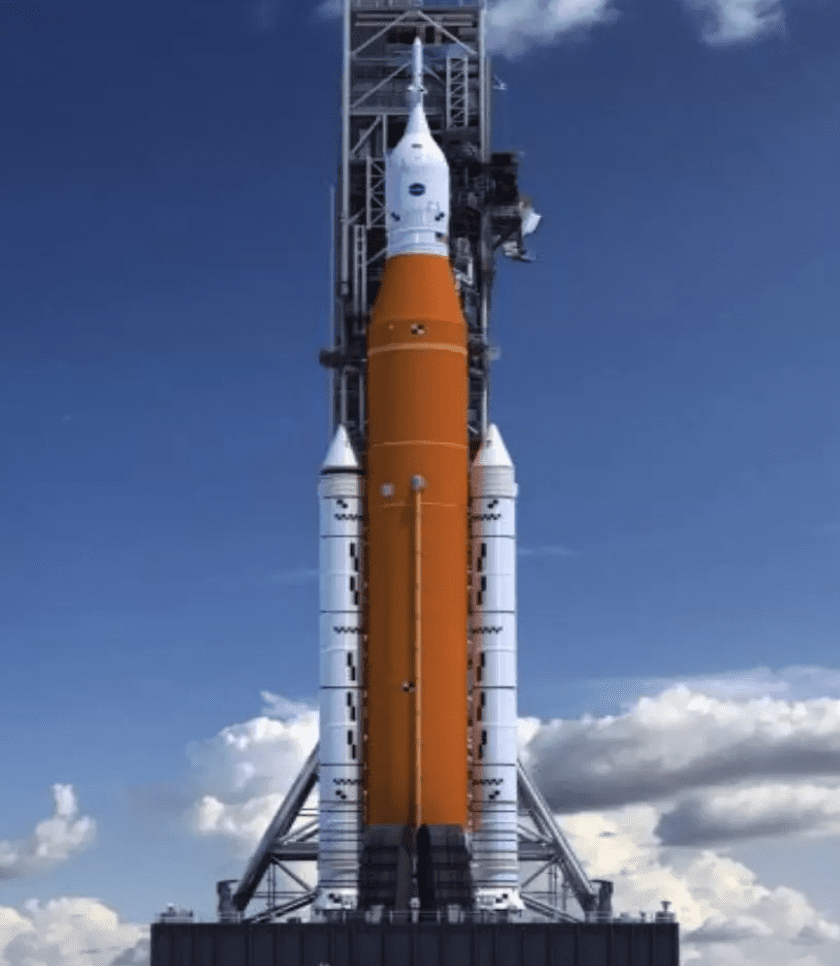

The Space Launch System represents one of the most powerful rockets ever constructed. When fully assembled and stacked at the launch pad, the vehicle rises approximately 322 feet tall and weighs approximately 5.7 million pounds. This makes it comparable in height to the Saturn V rockets that launched the Apollo missions, though the SLS incorporates dramatically more advanced technology and capability.

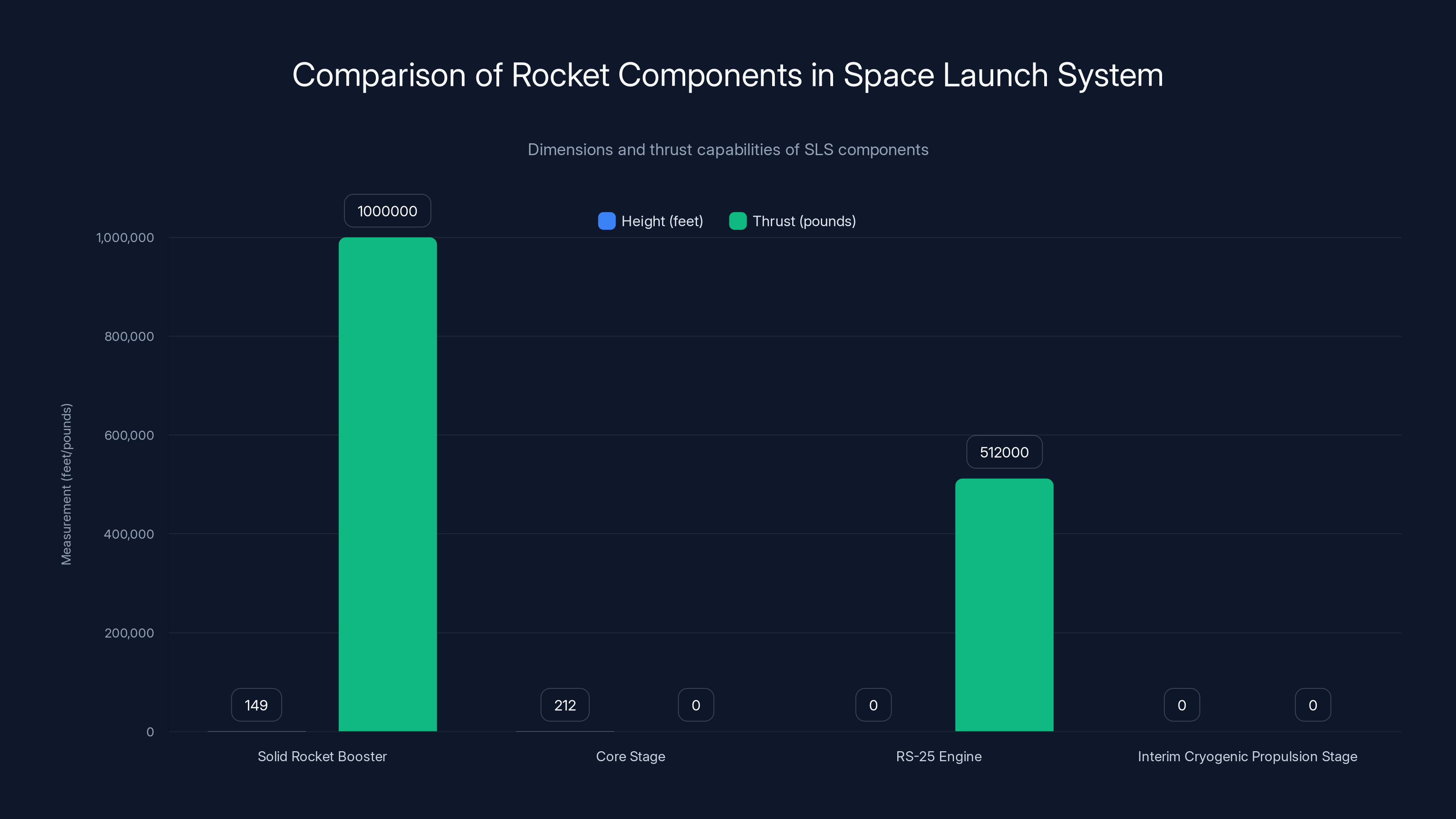

The rocket's architecture reflects decades of rocket engineering evolution. At its foundation sit two solid rocket boosters, each standing 149 feet tall and containing over 500,000 pounds of specially formulated solid propellant. These boosters provide the initial thrust needed to lift the massive vehicle off the launch pad. About two minutes into flight, these boosters separate from the core stage and parachute back to Earth for recovery and refurbishment, reducing launch costs.

The core stage, built by Boeing, serves as the rocket's backbone. This massive cylinder, 212 feet long and 27.6 feet in diameter, contains the structural framework, avionics systems, and fuel tanks for liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. Four RS-25 engines, descendants of the Space Shuttle Main Engines, power the core stage. These engines, operating at nearly 100% of their rated thrust, generate approximately 512,000 pounds of thrust each when firing together.

Above the core stage sits the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, another liquid-fueled engine section that provides the additional velocity needed to reach lunar trajectory. This stage uses a single RL10 engine powered by cryogenic propellants. The arrangement allows the SLS to achieve the specific energy requirements for translunar injection, the maneuver that sends spacecraft on a path toward the Moon.

The complete stack must be assembled with extreme precision. Each bolt, seal, connector, and system component goes through rigorous inspection and testing. Over 150,000 individual components comprise the flight vehicle, each manufactured to exacting specifications and verified through multiple testing phases. The integration process occurs in NASA's Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center, the same facility where Saturn V rockets were assembled during the Apollo program.

One critical challenge involves managing the cryogenic propellants. Liquid hydrogen boils at negative 423 degrees Fahrenheit, while liquid oxygen boils at negative 297 degrees Fahrenheit. Maintaining these temperatures while the rocket sits on the launch pad, transfers fuel through miles of piping, and waits for the final countdown window requires sophisticated thermal control systems and constant monitoring. Small temperature variations can mean the difference between a successful launch and an abort.

The rocket's avionics and flight control systems represent another layer of complexity. These computers must monitor thousands of parameters, make real-time decisions about engine throttling and vector control, and maintain accurate guidance to ensure the payload reaches the correct orbital insertion point. The systems include redundancies at multiple levels, so the loss of any single component doesn't compromise the mission.

Ground support equipment extends the complexity far beyond the rocket itself. Mobile launch platforms, crawler transporters, fuel handling systems, data processing centers, and communications networks all work in concert to prepare the vehicle for launch and monitor its performance during ascent. The crawler alone, which moves the complete rocket and launch platform from the assembly building to the pad, weighs 2,750 tons and travels at approximately one mile per hour when fully loaded.

The Space Launch System features towering components with significant thrust capabilities, notably the solid rocket boosters and RS-25 engines, essential for lunar missions.

The Orion Spacecraft: Protecting Astronauts in Deep Space

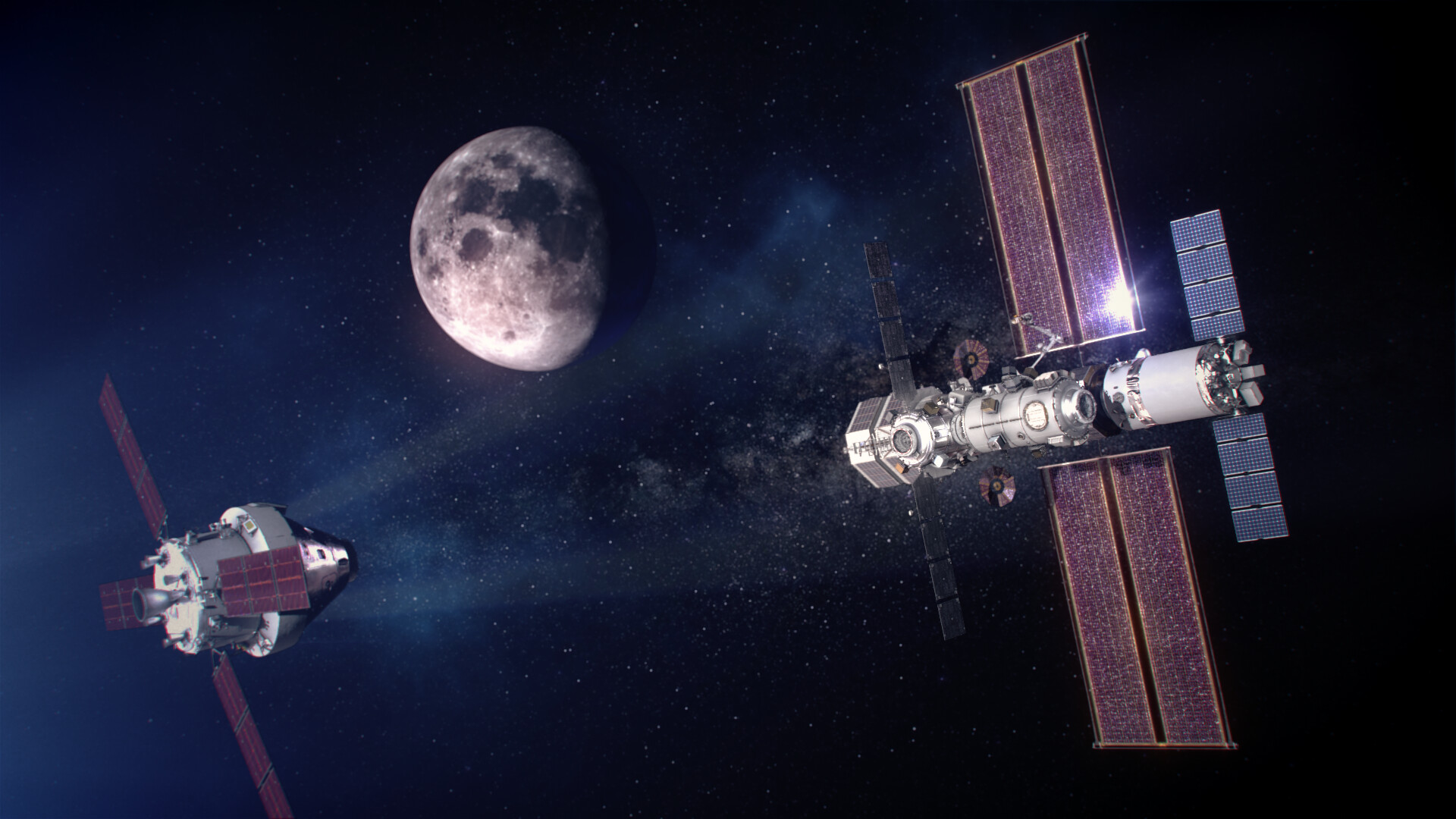

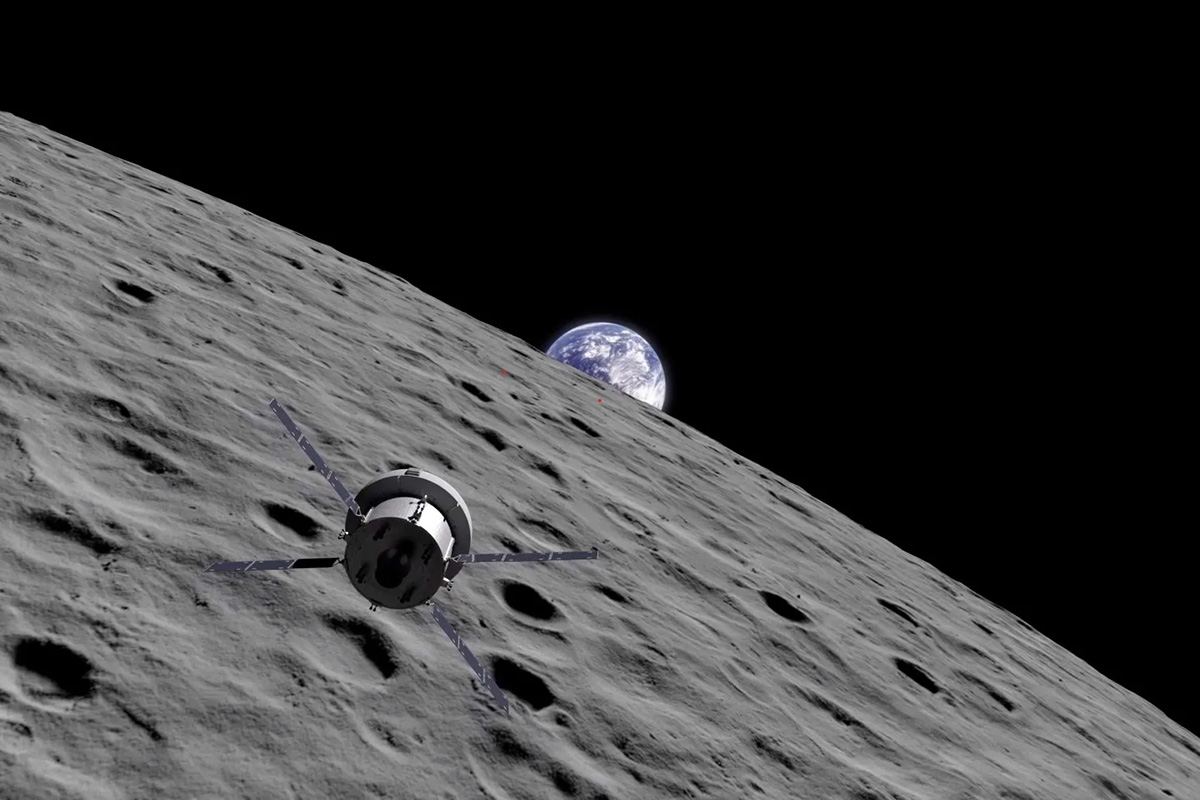

Perched atop the Space Launch System sits the Orion spacecraft, a cone-shaped capsule designed to protect and sustain a crew of four during their journey through cislunar space. Orion represents a completely new spacecraft design that incorporates lessons learned not only from the Apollo program but from decades of unmanned spaceflight operations, International Space Station experience, and modern engineering capabilities.

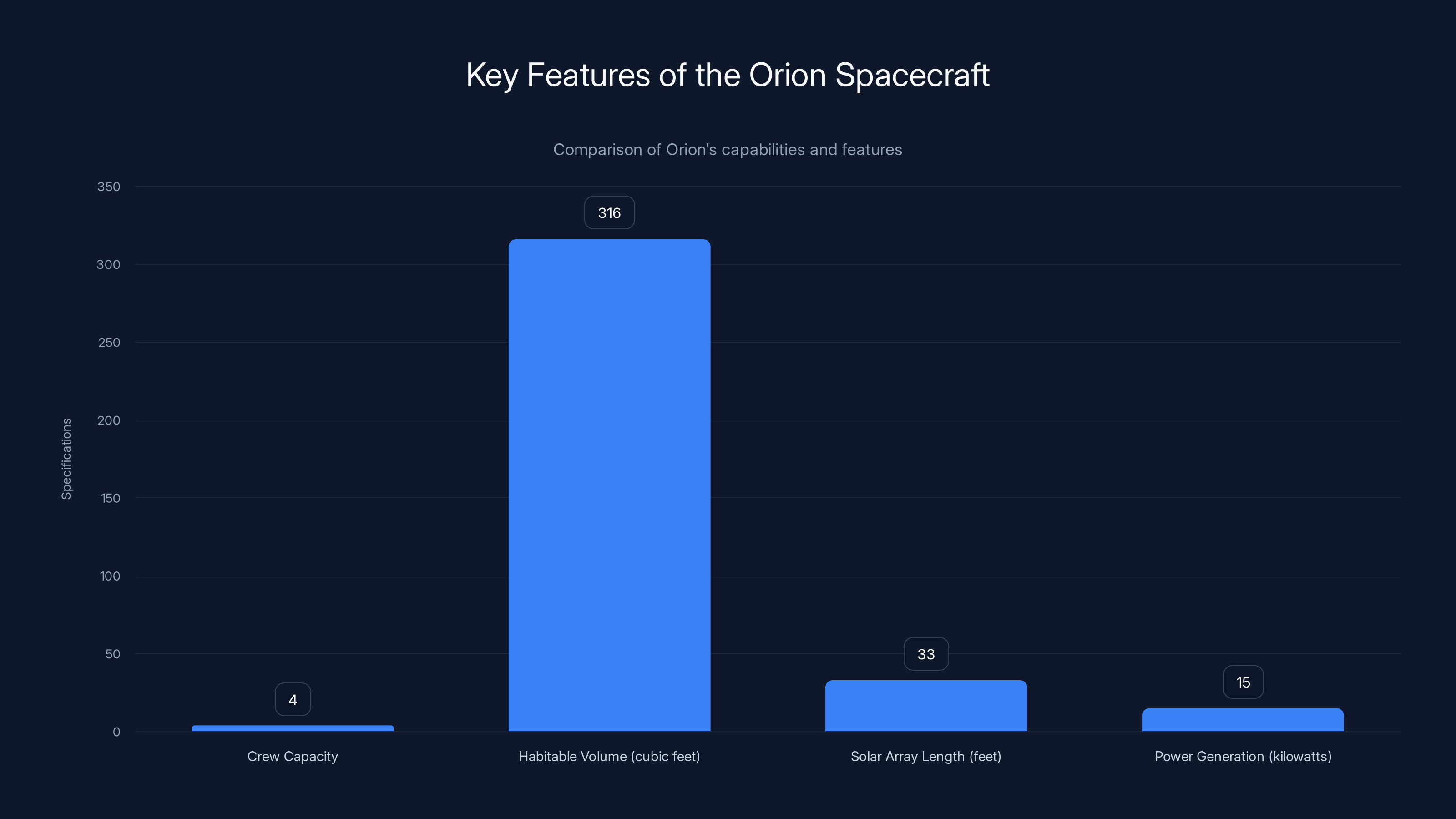

The spacecraft comprises three main modules. The crew module, the most recognizable part with its distinctive heat shield, measures 16.5 feet in diameter and provides habitable volume for the four astronauts. This cabin houses life support systems, water recyclers, atmospheric processors, and all equipment needed to sustain human life during the ten-day mission. Unlike the cramped conditions of Apollo capsules, Orion's crew module provides approximately 316 cubic feet of habitable volume, comparable to a small apartment.

The service module, an annular section surrounding the crew module, carries the propulsion systems, power generation equipment, and additional consumables. Four solar arrays extend from the service module's sides, each measuring approximately 33 feet long and capable of generating up to 15 kilowatts of electrical power. This photovoltaic array design allows Orion to operate far from the Sun far more efficiently than battery-dependent alternatives.

The heat shield protects the spacecraft during the most violent phase of any spaceflight: reentry into Earth's atmosphere. Traveling at approximately 25,000 miles per hour, friction with the atmosphere generates temperatures exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The Orion heat shield, composed of a specialized ablative material that burns away gradually while absorbing energy, must withstand these extreme conditions while maintaining structural integrity. Engineers designed and tested the material extensively, including ground tests with arc jets and high-temperature furnaces, before qualification for crewed flight.

The design incorporates numerous safety features. Multiple redundant systems control orientation, propulsion, and life support. The crew has both automated and manual capability for critical functions. Emergency systems include the capability to separate the crew module from the service module if needed and initiate a safe reentry sequence. Multiple parachutes provide primary and backup descent control during the final phase of return to Earth.

Navigation systems guide Orion with remarkable precision. The spacecraft uses a combination of inertial navigation, star trackers that reference distant stars, and communications with Earth-based antennas to determine its position and velocity vectors. Autonomous guidance algorithms calculate the optimal trajectory to lunar orbit, around the Moon, and back to Earth. These systems must function reliably in environments far beyond the reach of global positioning satellites or other ground-based navigation aids.

The life support systems inside the crew module handle multiple critical functions. Oxygen generation equipment extracts oxygen from water through electrolysis, providing breathable air for the crew. Carbon dioxide scrubbing systems use specialized sorbents to remove carbon dioxide exhaled by the astronauts, maintaining breathable cabin atmosphere. Water recycling systems process urine and wastewater through filtration and electrolysis, reducing the amount of water that must be launched from Earth. Thermal control systems manage waste heat generated by equipment and human metabolism, preventing the cabin from becoming dangerously warm or cold.

The interior layout reflects careful consideration of crew operations and ergonomics. Each astronaut has a dedicated station with controls, displays, and workspace. The layout allows all four crew members to see critical windows for navigation and scientific observation. Stowage compartments throughout the cabin hold equipment, consumables, experiments, and personal items. The design balances the needs for functionality, accessibility, and comfort during an extended mission in a confined environment.

Artemis II will be the longest and farthest crewed mission to the lunar vicinity, testing new technologies for future lunar landings. Estimated data for Artemis II.

The Four-Person Crew: Who's Going to the Moon

Mission success ultimately depends on the capabilities, training, and judgment of the four astronauts selected for Artemis II. These individuals represent decades of combined spaceflight experience and underwent some of the most demanding training programs in human spaceflight history.

The commander, selected to lead the mission and serve as the senior operational authority, brings extensive experience from previous spaceflight missions. The pilot, responsible for spacecraft maneuvering and supporting the commander, has similarly demonstrated exceptional capability. The two mission specialists, selected for their expertise in various technical and scientific disciplines, round out the crew with complementary skills and knowledge.

Training for a lunar mission exceeds the rigor of typical low Earth orbit missions. The crew spent hundreds of hours in simulators replicating normal operations, system failures, and emergency scenarios. They studied celestial mechanics to understand the three-dimensional geometry of translunar trajectories. They practiced emergency procedures in multiple environments: underwater for suited operations, in aircraft providing brief periods of microgravity, and in centrifuges producing high-g acceleration profiles matching reentry forces.

Their training included learning to navigate and operate spacecraft systems in ways that differ significantly from either previous crewed spacecraft or robotic unmanned systems. They studied Orion's unique design features, its emergency systems, and the procedures for dealing with various contingencies. They practiced using extravehicular activity suits designed to support operations outside the spacecraft. They underwent extensive systems training, learning everything from how to manage electrical power distribution to how to manually override automation if needed.

The crew selection process emphasized not only technical competence but also psychological suitability for a nine-day mission confined to a small spacecraft millions of miles from Earth. The individuals selected demonstrated the ability to work effectively as a team under stress, maintain focus during repetitive tasks, and solve problems creatively when unexpected situations arise. Each crew member brings not only their primary expertise but also backup capabilities in critical areas, so the loss of any individual wouldn't compromise the team's ability to safely execute the mission.

Understanding the Artemis II Timeline and Launch Windows

Spaceflight planning involves understanding the orbital mechanics that govern how objects move through space. For Artemis II, the launch date isn't arbitrary but must align with specific geometric relationships between Earth, the Moon, and the spacecraft's trajectory requirements.

NASA's launch planning included several potential launch dates, each offering a window of a few hours when conditions align for a successful trajectory to lunar orbit. These windows don't occur daily but rather on specific dates separated by weeks or months. The Moon's position in its 29.5-day orbital cycle, Earth's rotation, and the requirements for safe reentry corridors all influence the selection of launch dates.

The target launch window extended across several days in February, each day offering multiple hours when launch conditions were favorable. If weather prevented launch on a particular day, the next opportunity wouldn't arrive until the following day, and only during specific hours when the trajectory geometry remained appropriate. This constraint illustrates why launch teams must achieve remarkable precision in their preparations: miss a day's window, and the entire timeline shifts, potentially affecting downstream mission milestones.

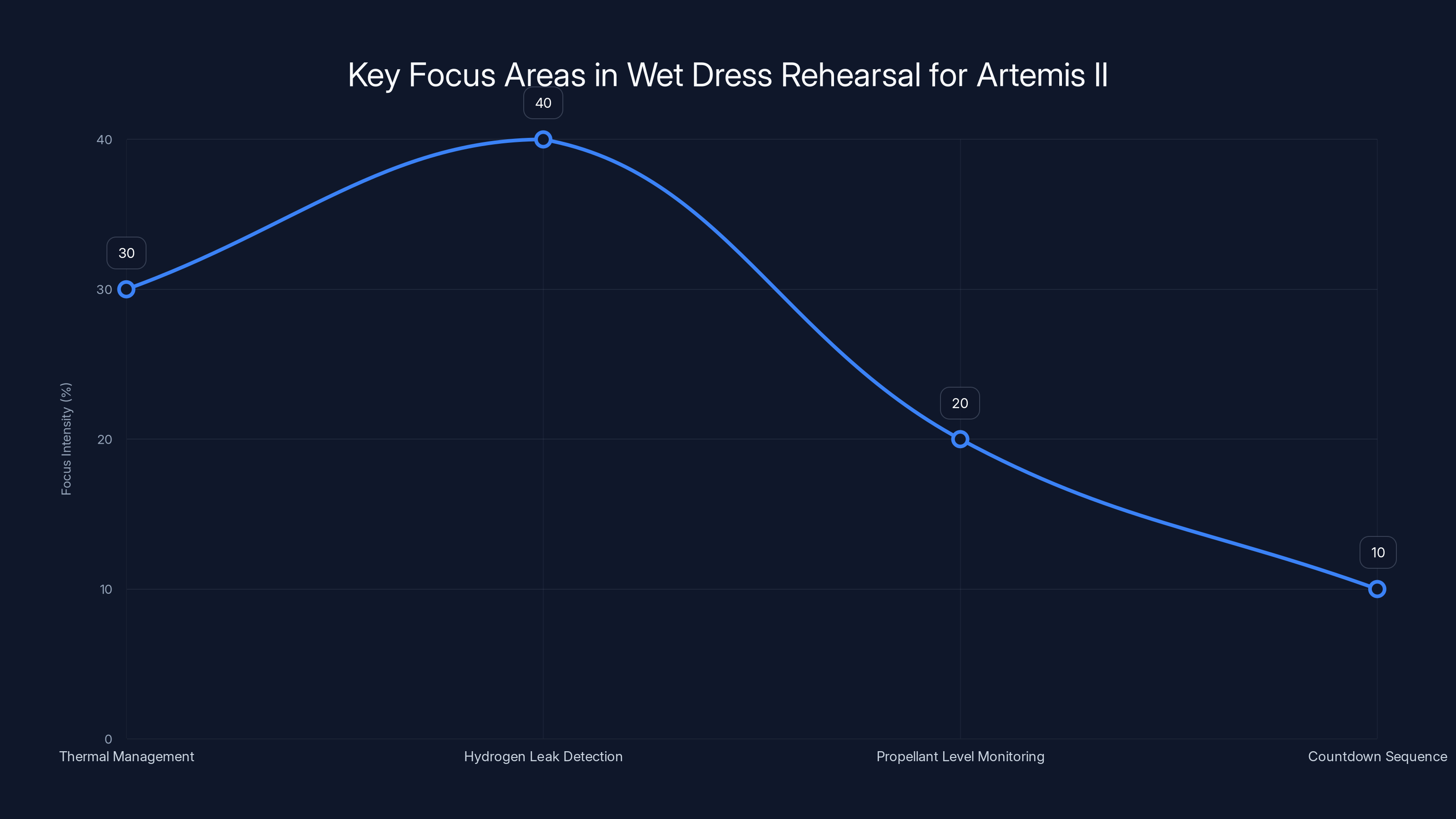

The mission architecture required that ground teams complete a critical rehearsal before committing to a launch attempt. This Wet Dress Rehearsal involved loading the complete propellant load into the rocket's tanks and bringing all systems to launch readiness, without actually performing the ignition and launch sequence. This exercise allowed teams to verify that all systems performed correctly under operational conditions before the actual launch attempt.

The rehearsal specifically focused on cryogenic loading, an area where previous missions encountered difficulties. Temperature monitoring, flow rate management, and sensor validation all received careful attention. Engineers watched for any anomalies in the data streams, ready to halt the process if any reading indicated a potential problem. This exercise served as the final dress rehearsal before the actual launch day, when NASA's teams would execute the same sequence with the committed intent to send the spacecraft on its way to the Moon.

Orion's design significantly enhances crew capacity and habitable space compared to Apollo, with advanced solar arrays generating up to 15 kilowatts of power.

The Engineering Challenge of Cryogenic Propellant Management

One of the most technically demanding aspects of preparing Artemis II involved managing the cryogenic propellants that fuel the SLS rocket. The technical challenges here merit detailed examination because they illustrate the kinds of engineering problems that have delayed the Artemis program and continue to require careful attention.

Liquid hydrogen, the preferred fuel for high-performance rocket engines, exists as a liquid only at temperatures below negative 423 degrees Fahrenheit. Even at this temperature, hydrogen possesses significant vapor pressure, meaning it naturally tends to evaporate. Liquid oxygen, the oxidizer that allows the hydrogen to burn, boils at negative 297 degrees Fahrenheit. Both cryogens must be kept extremely cold throughout the loading process and while the rocket sits at the launch pad.

The challenge increases when considering that the rocket's fuel tanks, despite extensive insulation, are not perfectly thermally isolated from their environment. Ambient temperature, solar heating, and heat transfer through structural elements all cause the propellant temperature to gradually rise. Engineers must constantly recirculate the propellants through refrigeration equipment to maintain proper temperatures. This boil-off gradually reduces the propellant mass available for flight, requiring careful planning to ensure sufficient reserves remain when launch actually occurs.

Hydrogen presents additional challenges beyond simple thermal management. Hydrogen molecules, the smallest element, can diffuse through many materials and seep through microscopic gaps in seals and connections. Previous launch attempts encountered hydrogen leaks that allowed the cryogen to escape from the system, reducing the fuel available and creating potential safety hazards. NASA's teams spent considerable effort redesigning seals, connectors, and tank closure mechanisms to minimize leakage.

The loading procedure itself requires exceptional precision. Ground support equipment measures propellant flow rates, temperatures, pressures, and tank levels continuously. Operators carefully manage multiple simultaneous flows as fuel tanks fill, monitoring data and ready to halt the process if any parameter diverges from expected values. The procedure takes many hours, during which thousands of individual measurements must remain within specified limits.

Engineers learned from the Artemis I mission's loading experience. That mission required multiple attempts and several delays before the propellant loading succeeded. The modifications made to Artemis II's hardware and procedures incorporated lessons from that experience. New seals with improved hydrogen compatibility, enhanced temperature monitoring, and refined operational procedures reduced the likelihood of repeating previous problems.

Rollout to the Launch Pad: The Final Assembly Phase

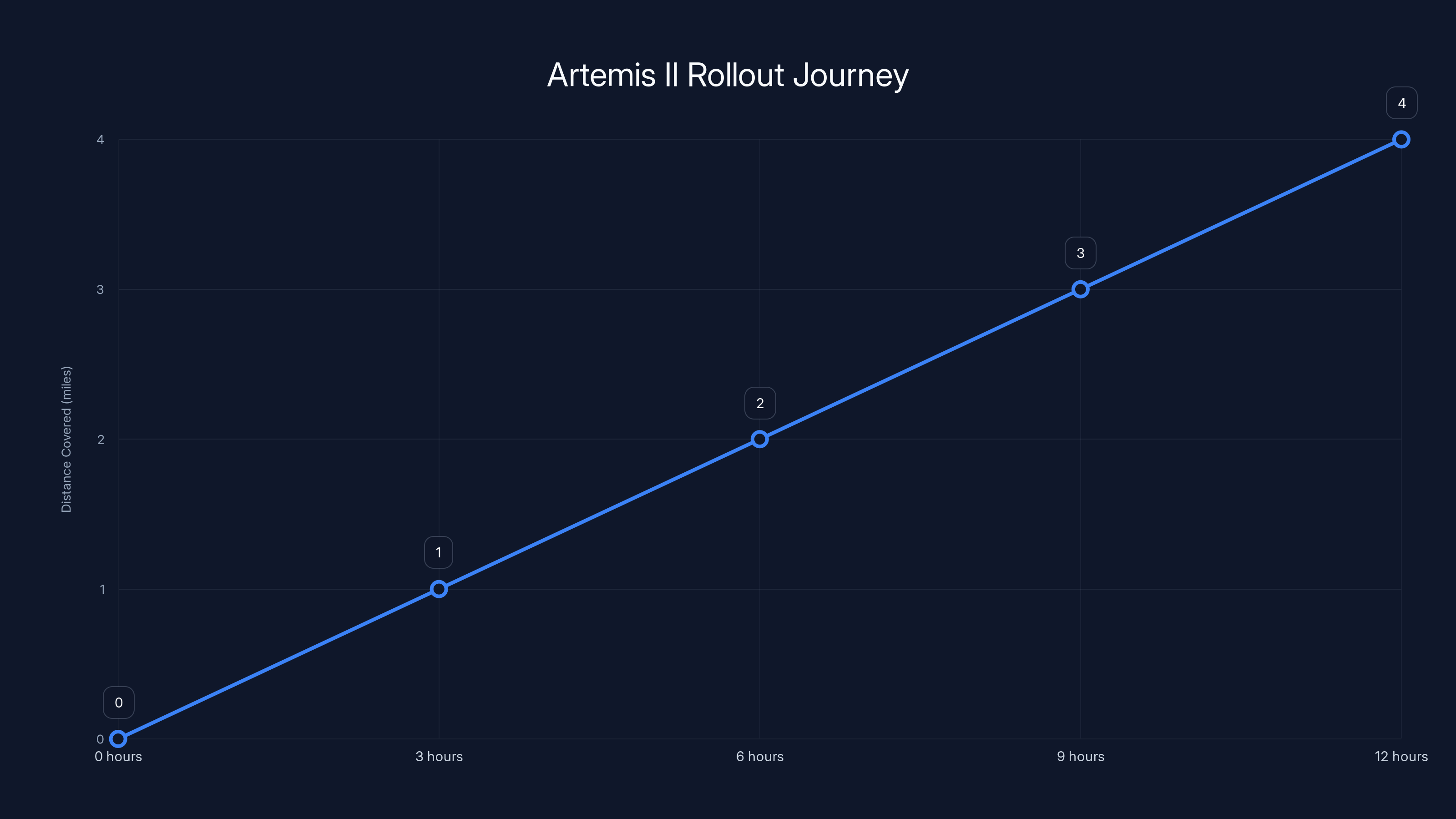

The movement of the Artemis II rocket from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Complex 39B represented a milestone in the mission timeline. This operation, called rollout, required moving an 11-million-pound stack of hardware along a specially constructed pathway at an average speed of just one mile per hour.

The crawler transporter performing this feat weighs 2,750 tons, making it one of the largest land vehicles ever built. It moves on dual crawlerways separated by a broad median, each pathway composed of crushed Alabama river rock. The crawler's massive jacking system must maintain the launch platform perfectly level throughout the journey, ensuring that the rocket remains stable and that thermal connections, umbilical cables, and other integrated systems stay properly aligned.

The journey covered approximately four miles over approximately twelve hours. This seemingly leisurely pace reflects the engineering demands of the operation. The crawler must navigate gentle curves without allowing the rocket to sway. Operators monitor clearances constantly, watching for any contact with the surrounding terrain or structures. The pathway itself, despite being incredibly well maintained, contains subtle irregularities that could cause unwanted movement of the payload if the crawler traveled faster.

Once the rocket reached the launch pad, a complex set of alignment and connection operations began. The launch platform must seat perfectly on pedestals at the pad, establishing mechanical and thermal stability. Umbilical connections that supply fuel, oxidizer, coolant, electrical power, and data signals must be physically mated. Each connection requires verification to ensure proper function. Ground support equipment must be positioned and connected to provide services during the final countdown.

The rollout itself attracted attention because it represented clear evidence that the program had progressed to its final stage. Personnel gathered along the crawlerway to observe the event. Media captured images of the massive rocket moving slowly beneath clear Florida skies. For NASA and its contractors, the rollout confirmed that months of assembly and testing had successfully prepared the vehicle for launch operations.

After a long hiatus since Apollo 17 in 1972, Artemis II marks a new era in human lunar exploration, representing the first crewed mission beyond low Earth orbit in over 50 years. Estimated data.

Systems Integration and Pre-Launch Testing

Before a crewed rocket can launch, it must undergo extensive testing to verify that all systems function correctly and that failures in any single component won't prevent the crew from returning safely to Earth. For Artemis II, this testing extended over months of activity prior to the rollout.

During assembly in the Vehicle Assembly Building, technicians conducted continuous verification as each major component was installed. The solid rocket boosters underwent detailed inspection, including X-ray imaging of the internal propellant grain to verify proper compaction and absence of cracks. The core stage had undergone multiple test firings at the Stennis Space Center facility before being shipped to Kennedy, where additional tests verified its integration with other elements.

The Orion spacecraft itself had been tested extensively before arriving at Kennedy for mating to the SLS. Hot tests of its propulsion systems, cold tests of its life support equipment, and electrical integration tests all verified individual subsystem functionality. By the time Orion was installed atop the SLS, engineers possessed extensive baseline data on how the spacecraft systems performed.

Once fully integrated, the complete vehicle underwent combined systems tests. Electrical power flowed through the rocket's distribution systems, verifying that all circuits received proper voltage and power. Data networks were exercised, ensuring that sensors, computers, and communication equipment all exchanged information correctly. Propellant loading and thermal control systems were tested in comprehensive simulations that exercised the equipment that would be used during the actual countdown.

These tests sometimes identified minor discrepancies or areas requiring adjustment. Ground teams would modify software, tighten connections, or make minor repairs. Each modification underwent review to ensure it didn't create unintended consequences. The iterative process of test, identify issues, implement fixes, and re-test continued until all systems demonstrated the required reliability.

The Wet Dress Rehearsal: Final Verification Before Launch

The Wet Dress Rehearsal served as the final comprehensive test before launch. The exercise involved loading the complete flight propellant load into the rocket's fuel tanks and bringing the vehicle to the point where launch would normally occur, then halting the process short of actual ignition and liftoff.

This rehearsal exercised all the same procedures, ground support equipment, and monitoring systems that would be used during the actual launch. The launch team would practice the complete countdown sequence, running through all the procedures and responses that would occur on launch day. This allowed technicians to identify any issues or procedural changes needed before the actual launch attempt.

For Artemis II, the rehearsal specifically focused on demonstrating that the cryogenic loading procedures worked reliably. Given that Artemis I had experienced difficulties in this area, particular attention was paid to thermal management, hydrogen leak detection, and propellant level monitoring. The complete loading sequence, lasting many hours, would proceed under the close observation of NASA's launch director and mission management team.

The data collected during the rehearsal would be analyzed thoroughly. Engineers would review every measurement to ensure that actual performance matched predictions and requirements. Any anomalies, no matter how minor, would be investigated to determine whether they represented true issues requiring attention or merely expected variations in the data.

The rehearsal also served an important psychological purpose. The launch team, which included hundreds of individuals across multiple contractors and NASA centers, would practice executing their assigned roles. This hands-on experience increased confidence that the actual launch countdown, when it occurred, would proceed smoothly. Lessons learned during the rehearsal would be incorporated into the procedures and checklists used for the actual launch attempt.

The Artemis II rollout covered approximately four miles over twelve hours, maintaining a steady pace to ensure stability and alignment. Estimated data.

Mission Architecture: Trajectory Design and Lunar Operations

The path that Artemis II would take to reach lunar orbit and then return to Earth required careful design based on orbital mechanics principles established by Newton's laws of motion. The trajectory, while following fundamental physics, also needed to balance multiple competing requirements.

The initial trajectory takes the Orion spacecraft on a path that falls to the Moon rather than trying to fly to it like an airplane might. The SLS provides just enough velocity to push Orion beyond Earth's sphere of gravitational influence, allowing the Moon's gravity to eventually dominate. This trans-lunar injection burn occurs several hours after launch, when the spacecraft is already far from Earth. The Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage provides the specific impulse and thrust needed for this critical maneuver.

The spacecraft wouldn't enter lunar orbit as previous lunar missions did. Instead, Artemis II would pursue a lunar flyby trajectory that brings it within several thousand miles of the lunar surface and continues around the far side of the Moon before returning to Earth. This distant retrograde orbit, as it's called, allows the spacecraft to spend extended time in the lunar environment while maintaining sufficient distance that the Moon's gravity doesn't require complex orbital mechanics to escape.

During the portion of the mission when Artemis II operates in cislunar space, the crew would conduct scientific observations, test navigation systems, and perform experiments that gather data for future landing missions. The spacecraft's position would allow extensive photography of the lunar surface from angles not easily obtained by orbiting satellites. Scientists would observe lunar features, study surface geology, and gather data that informs site selection for future landing locations.

The return trajectory was designed to ensure safe reentry at the proper angle. Coming in too steeply risks destroying the spacecraft and subjecting the crew to excessive g-forces. Coming in too shallowly could cause the spacecraft to skip off Earth's atmosphere and continue into space. The trajectory design incorporates small correction burns that can adjust the reentry angle if needed, and the guidance system uses onboard sensors to continuously verify that the spacecraft remains on the proper path.

The reentry speed of approximately 25,000 miles per hour creates the extreme heating that makes the heat shield necessary. The spacecraft's orientation during reentry must be maintained so the heat shield faces the direction of motion, protecting the crew module behind it. Onboard computers and control systems manage this orientation automatically, though the crew has backup capability to manually control the spacecraft if the automatic systems fail.

Safety Systems and Emergency Procedures

Because human lives depend on the spacecraft functioning correctly, Artemis II's design incorporates redundancy and safety features at multiple levels. The engineering philosophy emphasizes preventing problems, detecting problems early if they occur, and providing the crew with options for responding if something unexpected happens.

Critical systems like guidance and control, life support, and propulsion utilize redundant computers and sensors. If one unit fails, backup systems automatically assume control. The crew is constantly apprised of system status through instruments and displays. Multiple independent alarm systems alert the crew to any abnormal conditions.

Emergency procedures cover scenarios from minor issues to catastrophic failures. The crew underwent extensive training on recognizing problems, diagnosing root causes, and executing appropriate responses. For the most serious emergencies, the spacecraft has the capability to separate the crew module from the service module and immediately initiate a high-g reentry, sacrificing the slower, more controlled descent that normally occurs but preserving the crew's survival.

The abort modes available early in the mission, when the rocket is near Earth, differ substantially from those available later in deep space. Early in flight, the escape system at the tip of the Orion spacecraft can fire and pull the crew module away from a failing rocket. Later, when the rocket has completed its mission and separated, the only abort capability is the spacecraft's own propulsion systems and life support resilience.

Procedures address equipment failures, atmospheric problems, contamination of supplies, structural damage from micrometeorite impacts, and numerous other potential scenarios. For each emergency, the crew has step-by-step procedures to follow, usually documented in quick-reference cards they can access. Training ensures that critical procedures are second nature so that crew can execute them under stress without needing to think through each step.

Estimated data shows that hydrogen leak detection received the highest focus during the rehearsal, reflecting lessons learned from Artemis I.

Ground Support and Mission Control Operations

The success of Artemis II depends not only on the spacecraft and its crew but also on the extensive support infrastructure on Earth. Mission control centers monitor the spacecraft continuously, receiving telemetry data and maintaining communication with the astronauts.

NASA operates multiple mission control centers, each with specialized expertise. The Launch Control Center at Kennedy Space Center manages the countdown and launch phase. The Johnson Space Center's Mission Control Center in Houston takes over once the spacecraft reaches orbit. Both facilities maintain continuous staffing with teams of specialists monitoring different subsystems and maintaining real-time communication with the crew.

The communication network extends globally. Ground stations at Kennedy, Houston, and various locations around the world receive and transmit signals from the spacecraft. During translunar coast, when the spacecraft is far from Earth, the Deep Space Network's large antenna facilities in California, Spain, and Australia provide communication capability. These facilities can reach across millions of miles with sufficient signal strength for reliable command and telemetry exchange.

Mission control personnel include flight directors who serve as the senior authority for mission decisions, flight surgeons who monitor crew health, systems specialists for each major spacecraft subsystem, and navigators who track the spacecraft's trajectory and plan maneuvers. These teams work in shifts around the clock during mission operations, ensuring that someone is always monitoring the spacecraft and ready to respond if any situation requires action.

The data from the spacecraft feeds into multiple workstations and display systems. Flight controllers see their subsystem parameters in real time, allowing immediate recognition of any anomalies. If something deviates from normal, specialists investigate the cause and determine appropriate responses. The process emphasizes thoroughness over speed; mission control will halt planned activities if anything seems amiss and take time to understand what's happening before proceeding.

The Significance of Human Spaceflight Records

Artemis II will establish multiple records that underscore humanity's expanding capability to conduct operations beyond near-Earth orbit. These records reflect not just engineering achievement but also scientific and exploratory significance.

The distance from Earth that the crew will achieve exceeds the previous record set during the Apollo 13 mission in 1970. That mission, intended to land on the Moon but cut short by a spacecraft failure, took the crew farther from Earth than any human had previously traveled. Artemis II will surpass that distance by more than 4,000 additional miles, reaching a point where the crew can see both Earth and Moon as distant objects.

The reentry speed record reflects the specific trajectory taken. A spacecraft returning from the Moon enters Earth's atmosphere faster than one returning from low Earth orbit, because it's moving faster in its orbital trajectory when it begins the return journey. This speed creates greater heating and requires more robust thermal protection. Successfully managing this extreme reentry condition demonstrates that the Orion heat shield design and entry procedures work reliably, paving the way for future lunar missions that face the same reentry challenge.

The inclusion of the first woman to travel beyond low Earth orbit and the first non-US astronaut to reach lunar distance represents expanding international participation in deep space exploration. These selections reflect NASA's emphasis on building international partnerships and ensuring that the future of lunar exploration involves nations and individuals from diverse backgrounds.

Lessons from Artemis I and Pathways to Future Missions

The unpiloted Artemis I mission, which launched in 2022, provided extensive data that directly influenced Artemis II's preparation. That mission flew the SLS and Orion spacecraft to the Moon and back, allowing engineers to validate that the systems worked as designed under actual spaceflight conditions.

Artemis I's successful completion didn't eliminate all concerns, but it provided confidence in fundamental design principles and operational approaches. The cryogenic loading difficulties experienced during Artemis I's countdown campaign had been resolved through engineering changes and procedure modifications. The thermal management systems worked acceptably. The navigation systems achieved the required accuracy. The parachute recovery systems functioned flawlessly.

Lessons from Artemis I informed numerous improvements and refinements made to Artemis II. Engineers identified areas where margins could be tighter, allowing slight reductions in mass or volume. They identified operational procedures that could be streamlined without compromising safety. They gained experience with how the hardware performed in actual spaceflight, rather than in ground tests.

The success of Artemis II would establish the foundation for Artemis III, the next mission in NASA's program. That mission would include a landing on the lunar surface, allowing astronauts to conduct extensive exploration, collect samples, and test equipment for establishing a sustained presence on the Moon. The Artemis II crew's experience testing navigation systems and confirming spacecraft reliability would directly support the more challenging Artemis III mission.

Beyond Artemis III, NASA envisions a long-term lunar exploration program. Sustained human presence would require establishing base camps with power systems, habitat modules, and life support infrastructure. Missions would focus on scientific objectives like studying lunar geology, searching for water ice deposits, and investigating the Moon's internal structure. Eventually, lunar resources might be extracted to support further space exploration.

Budget, Schedule, and Program Challenges

The Artemis program's path to readiness involved navigating substantial budget and schedule pressures. Early cost estimates proved optimistic, requiring significant budget increases as the program matured. Technical challenges, like the cryogenic propellant issues, caused schedule delays that extended the program timeline by years.

The program faced competition for resources from other NASA initiatives and Congressional priorities. Advocates argued that exploration of the Moon was essential for developing technologies and operational experience needed for eventual human Mars missions. Critics questioned whether the investment was justified given competing priorities and the expense involved.

These challenges are not unique to Artemis but reflect broader patterns in large-scale government spaceflight programs. The complexity of developing new spacecraft and launch systems, the inherent risks in pushing technology to new limits, and the difficulty of accurately predicting how long development will take all contribute to schedule delays and budget increases.

Despite these challenges, the program persisted. NASA's leadership remained committed to returning humans to the Moon and making it a stepping stone for eventual Mars exploration. Contractors and NASA centers worked through the technical problems. The teams preparing the spacecraft and rocket for launch maintained focus on the goal of flying the mission safely and reliably.

International Cooperation and Commercial Partnerships

The Artemis program exemplifies international cooperation in space exploration. While NASA leads the program, numerous international partners contribute specific elements or capabilities.

The European Space Agency provides the service module that supplies power, propulsion, and thermal control for the Orion spacecraft. This contribution reflects ESA's commitment to Artemis and its interest in participating in lunar exploration. Canadian agencies contributed the robotic arm and other systems that will support operations during lunar missions.

Japan, India, and other space-faring nations have expressed interest in contributing to lunar exploration. Some nations are developing their own lunar landers and rovers. The international cooperation approach allows multiple nations to participate according to their capabilities and interests while consolidating resources on a shared goal.

Commercial space companies also play roles in the Artemis architecture. Space X's Starship, still in development, will eventually provide the lunar lander for the Artemis III landing mission. Other commercial companies provide hardware, ground support services, and mission operations support. This partnership model leverages both government resources and commercial innovation.

Technology Demonstration and Navigation Validation

Beyond the primary objective of returning humans to lunar distance, Artemis II serves as a testbed for technologies and operational procedures that will support future deep space missions.

The Orion spacecraft's autonomous navigation systems will be extensively tested during the mission. These systems must determine the spacecraft's position using onboard sensors and information from Earth-based tracking stations. The accuracy of navigation directly affects the crew's safety, particularly during reentry when the trajectory must be precise for the heat shield to protect the spacecraft correctly.

Communication systems will be tested in the environment of deep space, far from Earth. The reliability of maintaining signal quality across millions of miles directly impacts mission success. Any communications failures could leave the crew unable to receive commands or relay critical information to mission control.

The Orion spacecraft's life support and thermal control systems will operate under conditions that differ from the International Space Station's environment. The mission duration of about ten days tests whether the systems can sustain a crew reliably for that extended period in the harsh environment of deep space. Data from Artemis II's life support systems will inform the design of Artemis III's life support configuration, which must sustain a crew for longer periods while also supporting lunar surface operations.

The spacecraft's power systems, relying on solar panels rather than radioisotope thermal generators used by some unmanned deep space probes, must operate at distances where solar intensity decreases significantly compared to Earth orbit. Testing the solar arrays' performance at lunar distance validates their design for missions beyond the Moon.

The Human Element: Why Crewed Missions Matter

Why undertake the substantial cost and risk of sending humans to the Moon when robotic probes could accomplish similar science objectives? The answer lies in the unique capabilities that human presence provides and the broader significance of human exploration.

Robotic rovers can explore a few miles, taking weeks or months to do so. A human geologist can traverse that same terrain in hours, making complex decisions about where to look next based on observations and intuition developed through years of training. Humans can recover from unexpected situations, adapt to new circumstances, and pursue new objectives not anticipated in the original mission plan.

Human missions inspire in ways that robotic missions cannot. The knowledge that humans are traveling millions of miles from Earth, conducting operations in an environment hostile to human life, captures the public imagination. This inspiration translates to support for space exploration and STEM education.

The experience of humans in deep space also drives development of technologies and procedures that have applications beyond space exploration. Life support systems developed for spacecraft have spin-offs for medical applications. Materials developed to withstand extreme temperatures find use in other industries. The challenge of operating equipment reliably in the harsh space environment pushes engineering forward.

From a long-term strategic perspective, humans returning to the Moon establishes a foundation for sustained presence. Establishing international agreements about lunar exploration, developing procedures for working in the lunar environment, and training astronauts in operations specific to the Moon all prepare humanity for a future where lunar presence becomes routine. This knowledge and experience directly supports eventual human exploration of Mars and other ambitious objectives.

Future Missions and the Artemis Architecture

Artemis II represents a stepping stone toward more ambitious objectives. NASA's architecture envisions a series of missions that progressively expand human capability in cislunar space and lunar operations.

Artemis III will accomplish a landing on the lunar surface, something not achieved since 1972. This mission will involve not just the Orion spacecraft but also a specialized lunar lander that will carry two of the four crew members to the surface. The other two crew members will remain in Orion orbit while the landing crew explores the lunar surface.

The landing sites selected for Artemis III focus on regions offering scientific interest and practical advantages. The South Pole region attracts interest because modeling suggests it contains deposits of water ice that could support future lunar bases. Scientists want to explore the chemical composition and geological history of regions not visited during the Apollo program.

Artemis III's landing equipment represents a new development challenge. The Starship lunar variant being developed by Space X must land softly in the lunar environment, provide life support for the landing crew during their surface stay, and ascend back to lunar orbit to rendezvous with Orion. The complexity of this rendezvous in lunar orbit, where communication delays with Earth reach several seconds, requires autonomous capability.

Subsequent Artemis missions would build toward sustained presence. A lunar base could provide a foothold for extended exploration. Equipment and supplies could be prepositioned using cargo missions. Eventually, crews could spend weeks or months on the lunar surface, conducting science, testing resource extraction techniques, and developing operational procedures.

This long-term vision requires technological developments beyond Artemis II and III. In-situ resource utilization, extracting water or other useful materials from the Moon, would reduce the need to transport everything from Earth. Advanced life support systems might regenerate air, water, and potentially food supplies. Habitats engineered for lunar conditions would protect crews while allowing productive work on the surface.

Conclusion: The Moment Before History

As Artemis II sits at the launch pad, waiting for the next launch window, the achievement of reaching this moment cannot be overstated. Decades of development, billions of dollars of investment, countless hours of engineering work, and the dedication of thousands of individuals have brought this moment into being.

The mission ahead holds multiple layers of significance. For the crew, it represents the culmination of years of training and preparation, along with the profound experience of traveling to a place where humans have rarely gone. For NASA, it demonstrates the capability to conduct complex human spaceflight missions beyond low Earth orbit, a capability needed for the broader vision of space exploration.

For the international community, Artemis II demonstrates that sustained human spaceflight beyond low Earth orbit remains achievable. The partnership between nations, the involvement of commercial companies, and the commitment of substantial resources reflect a consensus that space exploration matters.

When Artemis II launches, it will carry not just four astronauts but the hopes and dreams of everyone who believes in space exploration. It represents a commitment to pursuing knowledge, expanding human capability, and establishing the foundation for humanity's future in space. The journey to the Moon will take ten days. The significance of that journey will extend far beyond.

FAQ

What makes Artemis II different from previous lunar missions?

Artemis II is the first crewed mission to return humans to the lunar vicinity since 1972, representing a fifty-year gap in deep space human exploration. Unlike Apollo missions that landed on the surface, Artemis II will conduct a lunar flyby that takes the crew farther from Earth than any humans have previously traveled, then return to Earth at higher velocities than previous missions. The spacecraft incorporates modern technology and represents a new design that will be used for all future NASA lunar missions.

How long will the Artemis II mission take?

The complete mission lasts approximately ten days from launch until the crew returns to Earth. After launch and translunar injection, the spacecraft takes about three days to travel to the Moon, spends several days in the lunar vicinity, and then requires about three days for the return journey to Earth. The entire sequence tests whether Orion's life support systems can sustain a crew for this extended period in deep space.

What will the crew do during the mission?

The astronauts will conduct scientific observations of the lunar surface, test and validate navigation systems that will be used for future missions, perform experiments that gather data about the deep space environment, photograph lunar features from their unique vantage point, and practice procedures that future crews will use during landing missions. They will also monitor spacecraft systems, conduct routine maintenance, and document their experiences for analysis by ground teams.

Why haven't humans returned to the Moon before?

The Apollo program achieved six successful lunar landings between 1969 and 1972, but subsequent budget constraints and shifts in national priorities toward other programs like the Space Shuttle and International Space Station resulted in lunar exploration being postponed. Developing new capability for returning to the Moon required substantial investment and technological advancement. The Artemis program, initiated in the 2000s, represented a renewal of commitment to lunar exploration.

What is the significance of the Artemis II crew composition?

The four-person crew includes astronauts from different backgrounds and experience levels, representing NASA's commitment to diversity in space exploration. The crew's experience and training prepare them to handle all anticipated operations and respond to unexpected situations. The inclusion of international astronauts reflects NASA's emphasis on international cooperation in space exploration.

How does Orion compare to spacecraft used in previous lunar missions?

Orion is substantially larger and more capable than the Apollo Command Module that flew to the Moon. It provides more habitable volume for the crew, better life support systems with water recycling capability, enhanced thermal protection for higher reentry speeds, and more sophisticated autonomous systems. Orion is designed for longer missions and higher demands than Apollo vehicles, reflecting advances in materials, manufacturing, and systems engineering.

What happens if something fails during Artemis II?

The spacecraft has multiple redundant systems and emergency procedures for responding to various failure scenarios. For emergencies occurring early in flight before the rocket separates, the escape system at the tip of Orion can pull the crew module away from a failing rocket. For emergencies during deep space operations, the crew can execute emergency procedures using onboard propulsion and other systems. The design emphasizes preventing failures and detecting problems early so crew can address them before they become critical.

How will Artemis II prepare for Artemis III and lunar landing?

Artemis II will test and validate the navigation systems, life support equipment, thermal management, and operational procedures that Artemis III will depend upon. Data collected during Artemis II will inform design modifications and procedural refinements for the landing mission. The crew's experience will contribute to operational knowledge that improves safety and efficiency for subsequent missions. Essentially, Artemis II serves as a full-dress rehearsal for the more complex operations planned for Artemis III.

What is the estimated cost of the Artemis II mission?

While the complete Artemis program's cost reaches tens of billions of dollars, the marginal cost of the Artemis II mission itself (beyond the development costs already incurred) includes launch operations, mission control, crew support, and other operational expenses. The total program investment reflects the complexity of developing new deep space capabilities and the commitment required to establish human presence beyond low Earth orbit.

Could Artemis II impact other space exploration priorities?

The Artemis program represents a significant portion of NASA's budget, which could theoretically be allocated to other priorities. However, NASA's leadership has positioned Artemis as foundational for long-term space exploration goals. The technologies and operational experience gained through Artemis support eventual human missions to Mars and other deep space objectives. The program also distributes work across multiple contractors and facilities, generating economic activity and employment.

Key Takeaways

- Artemis II will be the first crewed mission to the Moon in 51 years, taking four astronauts farther from Earth than any humans have previously traveled

- The Space Launch System generates 8.8 million pounds of thrust at launch, comparable to Saturn V rockets but with modern advanced technology throughout

- Orion's 316 cubic feet of habitable volume, sophisticated life support systems with water recycling, and redundant safety systems enable reliable deep space operations

- The Wet Dress Rehearsal, loading 750,000 gallons of cryogenic propellants, represents the final critical test before launch attempts beginning in February

- Mission success requires flawless coordination among thousands of technicians, sophisticated ground support equipment, and autonomous spacecraft systems designed for operations millions of miles from Earth

![Artemis II: The Next Giant Leap to the Moon [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/artemis-ii-the-next-giant-leap-to-the-moon-2025/image-1-1768862382468.jpg)