NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means

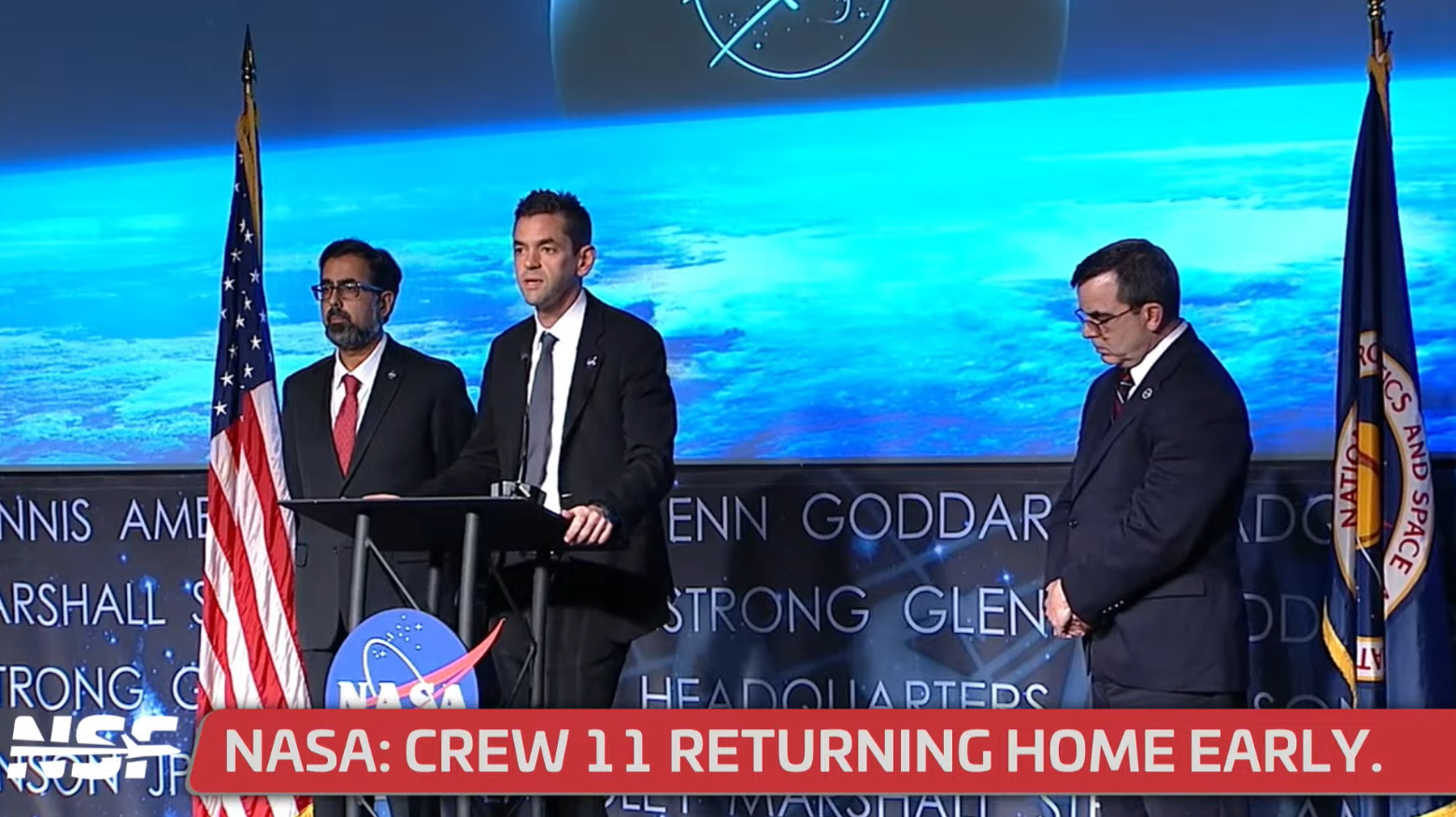

NASA just made a decision that hasn't happened before in the agency's human spaceflight history. On January 8, 2025, the space agency announced it would bring the Crew-11 astronauts home roughly a month earlier than planned, cutting their International Space Station mission short due to a medical concern with one of the crew members. This is significant. Not because it's dramatic or unexpected, but because it shows how seriously NASA treats health in the extreme environment of space.

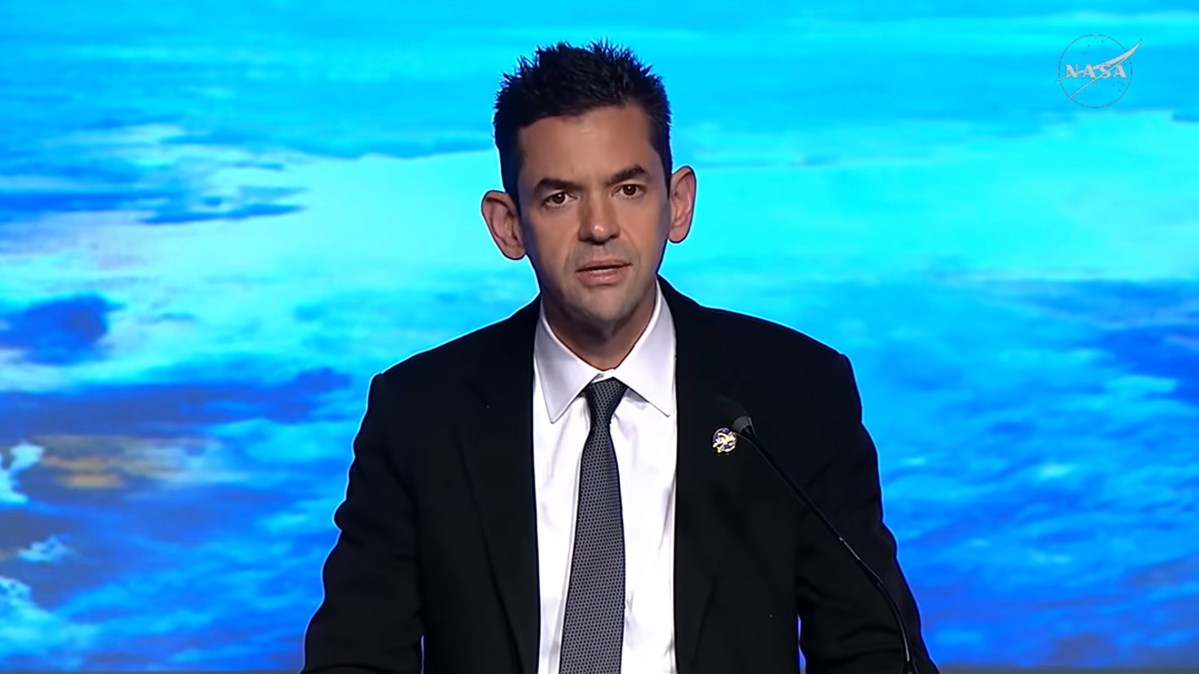

The decision came after NASA postponed a scheduled spacewalk, citing that same medical concern. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman said the agency would release more details within 48 hours. The affected astronaut, whose identity hasn't been disclosed, is reportedly stable. But stability doesn't mean everything is fine. It means NASA looked at the available medical resources aboard the ISS, recognized they weren't sufficient for proper diagnosis and treatment, and made the call to bring everyone home safely.

This isn't an emergency evacuation. It's not a crisis. It's careful, methodical risk management at 250 miles above Earth. And it tells us something important about how human spaceflight has matured: health concerns in space demand immediate, decisive action, not hope and monitoring.

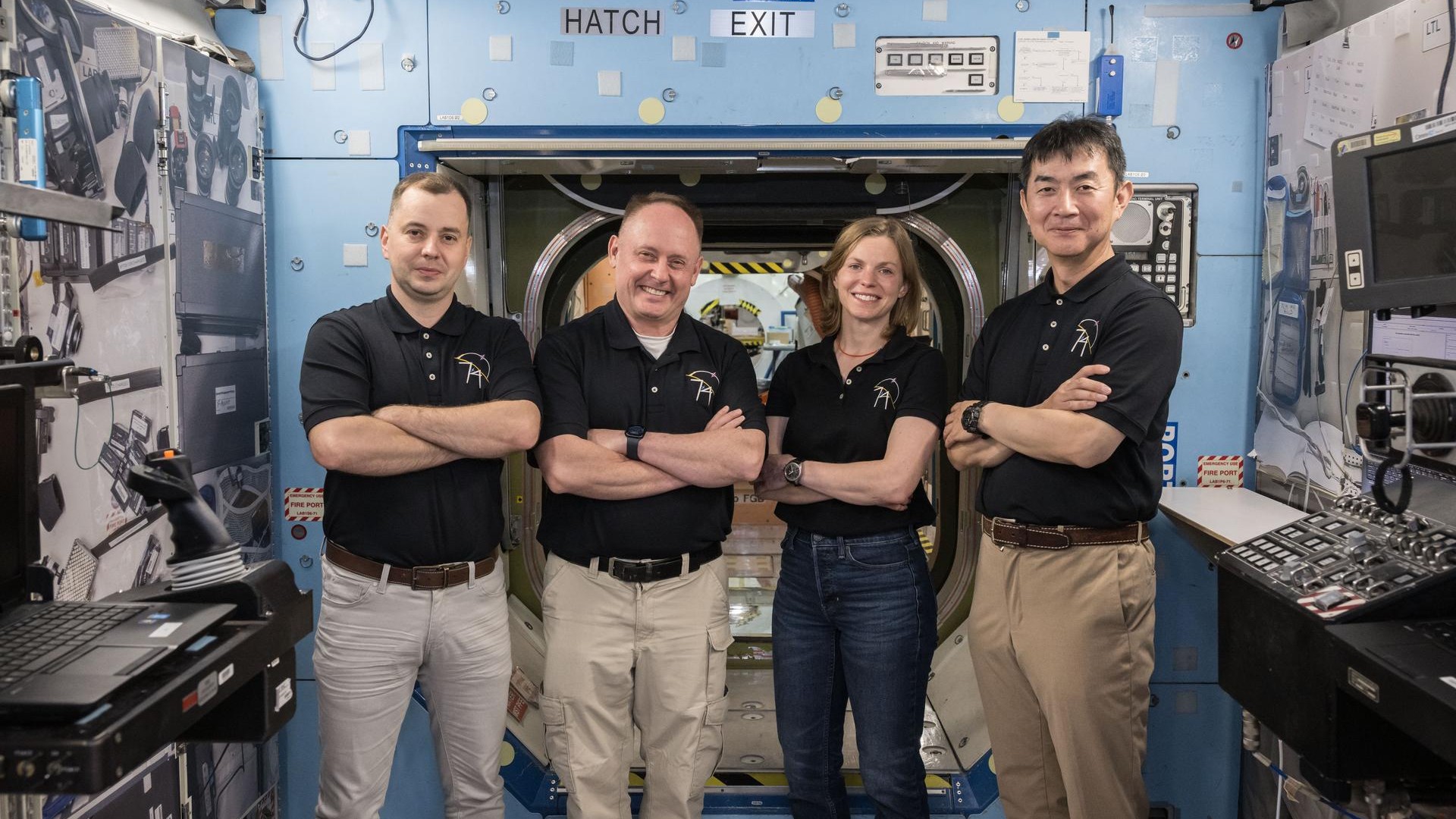

The Crew-11 mission launched on August 1, 2024, aboard a Space X Crew Dragon capsule. The team was supposed to stay until February 20, 2025, conducting microgravity research, maintaining station systems, and performing extravehicular activities. Instead, they'll be returning in the coming days. What happens next has cascading effects across the entire ISS schedule, crew rotation plans, and the hundreds of experiments currently running aboard the orbiting laboratory.

Let's break down what we know, what this decision means for NASA's operations, and why this moment matters for the future of human spaceflight.

TL; DR

- First time ever: NASA is ending a crewed mission early due to a medical concern, an unprecedented decision as noted by NBC News.

- Crew is stable: The affected astronaut is described as "absolutely stable" by NASA's chief health officer, according to Reuters.

- Not a diagnosis: NASA lacks the medical equipment aboard ISS to fully diagnose the condition, as detailed by Spaceflight Now.

- ISS fully staffed until replacement arrives: Three crew members will remain to continue station operations, as reported by SpaceNews.

- Crew-12 timing may shift: The replacement crew might launch earlier than originally planned in mid-February, as discussed in Orlando Sentinel.

Crew-11 dedicated significant time to microgravity experiments and research investigations, reflecting their mission's focus on scientific advancement. Estimated data.

Why NASA Made This Call: The Medical Decision Framework

Understanding why NASA pulled the trigger on this early return requires understanding the specific constraints of medical care in space. The ISS is equipped with a "robust suite of medical hardware," according to NASA's chief health and medical officer, James "JD" Polk. That includes diagnostic equipment, pharmaceuticals, and emergency supplies. But a robust suite isn't the same as a complete hospital.

An astronaut in Earth's gravity can walk into a clinic, get comprehensive imaging like MRIs or advanced blood work, see specialists, and get a diagnosis. An astronaut in microgravity aboard the ISS? They can get basic vitals, some blood work through limited labs, and perhaps some ultrasound. But for anything requiring detailed imaging or advanced diagnostics, they're stuck. You can't run a full CT scan in microgravity. You can't conduct the kind of comprehensive workup that determines whether a condition is serious or manageable.

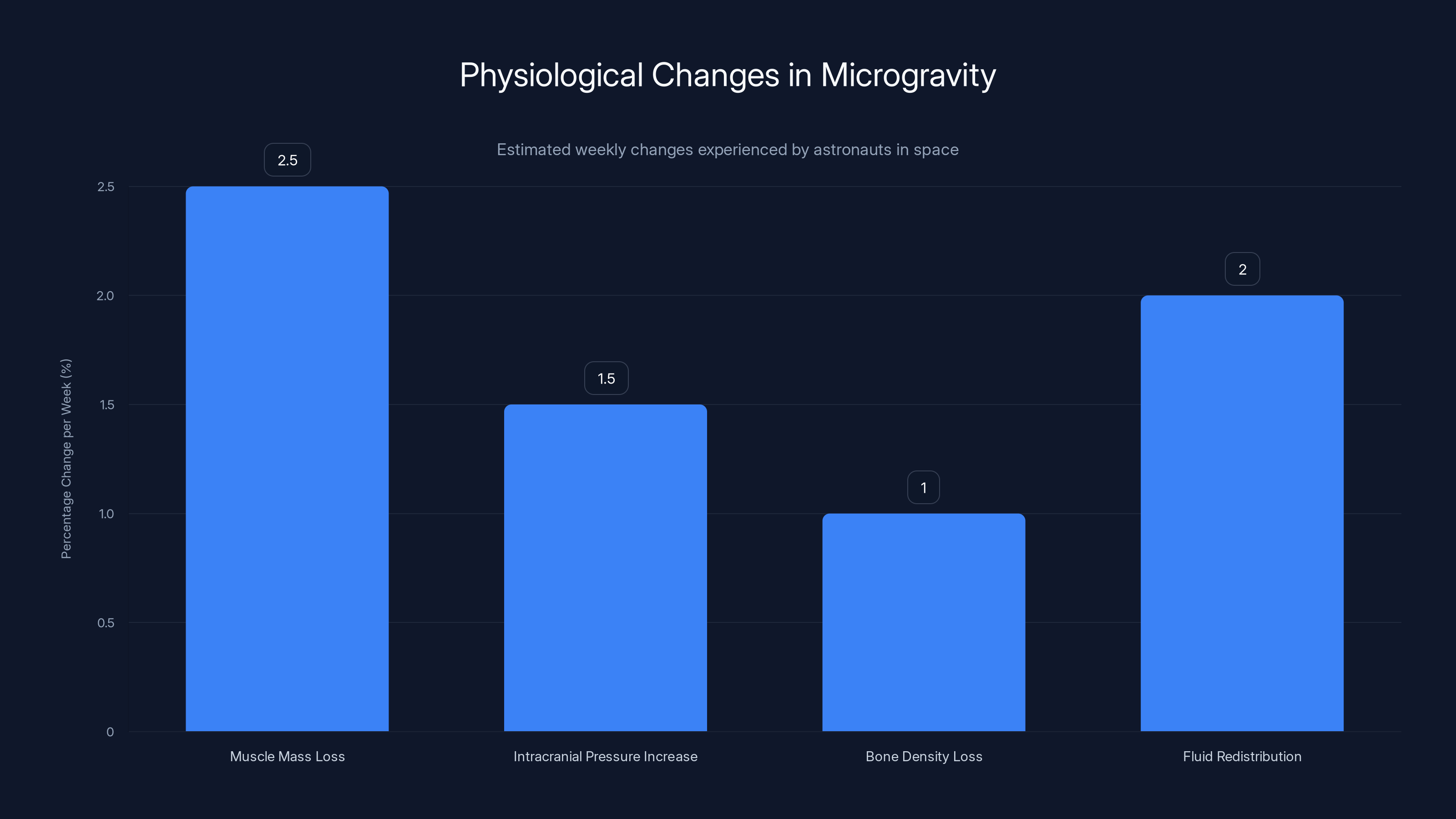

That's the crux of NASA's decision. An undiagnosed medical condition doesn't necessarily mean it's severe. But without a diagnosis, NASA doesn't know if the microgravity environment itself could make the condition worse. Microgravity affects the human body in profound ways. It shifts fluid distribution, reduces bone density, alters immune function, and changes how blood circulates. A condition that's manageable on Earth might deteriorate in space. Conversely, some conditions improve in microgravity. But you need a diagnosis to know which category applies.

NASA's approach reflects decades of lessons learned about acceptable risk in human spaceflight. The space agency isn't risk-averse—going to space is inherently risky. But it's risk-aware. The agency calculates what risks are acceptable, which ones require mitigation, and which ones are unacceptable. When NASA can't calculate that equation because it lacks diagnostic information, it errs on the side of caution. Bringing the crew home means the affected astronaut gets access to Earth's medical infrastructure, gets a proper diagnosis, and NASA learns whether the condition would have been manageable in space.

Polk emphasized that this isn't an emergency. "Absolutely stable" was his exact characterization. That's crucial context. This wasn't a heart attack, a serious injury, or acute illness requiring immediate evacuation. It was a medical anomaly that appeared, NASA recognized they couldn't properly assess it in orbit, and NASA made the deliberate choice to bring everyone home so they could.

Estimated data shows potential timeline adjustments for Crew-12's launch, highlighting NASA's need to balance operational constraints with the ISS staffing requirements.

The Timeline: When It Started and How It Unfolded

The medical concern didn't emerge on January 8. NASA detected it on January 7, the day before the spacewalk cancellation. The immediate response was postponing the scheduled extravehicular activity. But that was a holding action. Within 24 hours, NASA escalated its response to ending the entire mission early.

Crew-11 launched on August 1, 2024, giving them roughly five months in space before this medical issue surfaced. That's worth noting. These astronauts completed the first four-plus months of their six-month mission without incident. They'd performed multiple spacewalks, conducted thousands of hours of research, and maintained the ISS. Then, in early January, something changed.

NASA didn't immediately disclose the medical concern's nature. The agency cited privacy for the affected crew member. That's standard practice across human spaceflight programs. You don't publicly identify crew members with health issues without their consent. What matters operationally is that NASA detected something and responded to it appropriately.

The decision-making process likely involved multiple levels of review. NASA's flight surgeons analyzed the initial medical findings. The ISS flight director and operations team evaluated what onboard resources were available. The International Space Station Program Manager assessed the implications. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman made the final call. That process, while compressed, reflects the established protocols for medical decisions in space operations.

The announcement came with a commitment for more details within 48 hours. That transparency signals confidence in the decision. NASA wasn't hedging. The agency had evaluated the situation, made a call, and was prepared to explain it publicly.

What "Absolutely Stable" Actually Means in Space Medicine

James Polk's statement that the affected astronaut is "absolutely stable" requires unpacking. In medical terminology, "stable" means vital signs are normal, consciousness is clear, and the immediate condition isn't deteriorating. "Absolutely stable" reinforces that assessment. The astronaut isn't in acute distress.

But here's the nuance that gets lost in headlines: stable doesn't mean asymptomatic. Stable doesn't mean minor. It means the current state isn't immediately life-threatening. A person can be stable while experiencing a significant medical condition. Someone with a newly diagnosed heart arrhythmia can be stable. Someone with an emerging autoimmune response can be stable. Someone with a condition that might worsen in microgravity can be stable right now.

That distinction matters because it explains why NASA's response wasn't frantic. There's no indication of 2 AM emergency meetings or rushed preparations. Instead, NASA took deliberate time to assess the situation, consult with medical experts, and make an informed decision over a 24-hour period. That methodical approach is only possible when the patient is stable.

Space medicine operates under different constraints than Earth medicine. On Earth, a stable patient with an undiagnosed condition might remain hospitalized for monitoring and further testing. In space, that option doesn't exist practically. You can monitor someone in orbit, but your monitoring tools are limited. You can do some testing, but not comprehensive workups. At a certain point, continued monitoring in a limited environment yields diminishing returns. The better option becomes getting the patient to a place where comprehensive diagnosis and treatment are possible.

NASA made that calculation and chose Earth-side diagnosis and care.

Astronauts in microgravity experience significant physiological changes, including a 2-3% muscle mass loss per week and increased intracranial pressure. Estimated data highlights the importance of pre-mission medical evaluations.

Crew-11's Mission: What They Accomplished Before the Early Return

Before diving into the operational implications, it's worth acknowledging what Crew-11 achieved. These five months weren't wasted time leading up to an early departure. The crew conducted meaningful work.

Crew-11 includes experienced astronauts who've performed multiple spacewalks to maintain and upgrade ISS systems. They've operated the station's robotic arm, conducted microgravity experiments, and maintained the life support, power, and thermal management systems. They've participated in research investigations spanning materials science, biology, physics, and Earth observation. They've helped prepare the ISS for future missions and capabilities.

Microgravity research isn't theoretical. The experiments happening aboard ISS inform everything from medicine to manufacturing. Protein crystal growth in microgravity, for instance, helps researchers understand disease mechanisms. Combustion studies in microgravity improve engine efficiency on Earth. Manufacturing experiments test production processes that could eventually be conducted in space.

Crew-11's early return means some of those experiments will be cut short or passed to the remaining crew. It also means Crew-11 doesn't get the full six months they trained for. But the work they did accomplish was productive, and the decision to end the mission early reflects a medical judgment, not a failure in their performance.

The ISS Staffing Puzzle: Who Stays, Who Goes

Here's where the operational complexity emerges. When Crew-11 departs, three people will remain aboard the ISS: two cosmonauts and one astronaut. That's right. The ISS doesn't empty out when a crew returns. It operates continuously with overlapping crew rotations.

The remaining three crew members will become responsible for maintaining the ISS systems and continuing research operations. That's actually not unusual. The ISS routinely operates with three-person skeleton crews during transition periods between crew rotations. But it's the minimum workable staffing level. With three people, you have coverage for emergencies, redundancy for critical systems, and enough hands to manage basic maintenance. But there's no margin for additional issues or ambitious new projects.

Those three crew members will focus on essential tasks. They'll maintain life support, power systems, thermal management, and communications. They'll keep experiments running that require human attention. They'll prepare the ISS for the next crew arrival. But they won't be launching new major research initiatives or conducting significant spacewalks. Three people can't do everything.

This staffing constraint is exactly why NASA's early return decision creates a cascading effect through the schedule. The longer the ISS stays with only three people, the more constrained operations become. The station can't function long-term with just three crew members. NASA built this incredible orbiting laboratory with the assumption that six to seven people would be aboard. With fewer people, capabilities shrink.

Earth hospitals have superior diagnostic capabilities compared to the ISS, particularly in advanced imaging and comprehensive lab tests, highlighting why NASA opted to bring Crew-11 back for better medical evaluation.

Crew-12's Launch Timeline: The Critical Next Step

This is where the early Crew-11 return becomes consequential for future scheduling. Crew-12 was originally scheduled to launch mid-February 2025, roughly when Crew-11 was supposed to return anyway. The plan was smooth, overlapping transitions with old crew handing off to new crew over several days of overlap.

Now, Crew-12 might launch earlier than planned. NASA is "considering" earlier launch dates according to statements from the agency. That's diplomatic language for "we're seriously evaluating moving this up." If Crew-11 returns in, say, mid-January, and Crew-12 doesn't arrive until mid-February, that's a full month with only three people aboard. That's longer than NASA prefers.

Accelerating Crew-12 requires coordinating with Space X, ensuring the vehicle is ready, ensuring the crew members' final training is complete, and coordinating with the Russian space program since the ISS is a joint facility. These aren't trivial logistics. But NASA has successfully accelerated crew launches before when operational requirements demanded it.

The question isn't whether NASA can move Crew-12 up. The question is by how much, and whether that disrupts other planned activities. Every day Crew-12 launches earlier than planned, Space X has one day less to verify systems, conduct final checks, and prepare. But delaying Crew-12 means prolonged understaffing aboard ISS. NASA has to balance these factors.

Medical Concerns in Space: Historical Context and Precedent

While this is the first time NASA has ended a mission early specifically due to a diagnosed medical concern, health issues in space aren't novel. Astronauts get sick in orbit. They experience motion sickness, upper respiratory infections, and minor injuries. The difference is that these minor issues are managed in place. The affected astronaut rests, takes medications if necessary, and waits for the condition to resolve or stabilize.

What triggers an early return isn't minor illness. It's a condition serious enough that NASA's medical team determines the ISS environment itself might be contraindicated. That could mean a cardiovascular issue where the fluid shifts of microgravity would be dangerous. It could mean an infection where the immune function challenges of spaceflight would be problematic. It could mean any condition where the documented medical effects of microgravity would worsen the situation.

Historically, serious medical issues in space were managed through careful monitoring and planning for earlier return rather than dramatic emergency evacuation. Skylab had medical events. The Mir space station dealt with medical concerns. The ISS has had health issues among crew members. But NASA and the Russian space program have built systems to handle these situations—not by ignoring them, but by maintaining the capability to bring people home safely when necessary.

The fact that this is the first official "early return due to medical concern" announcement doesn't mean medical issues never prompted early returns before. It might mean that previous situations were handled more quietly, or that the triggering conditions were different. NASA's decision to publicly announce this situation reflects confidence in the decision and commitment to transparency.

Estimated data: AI diagnostic systems are projected to have the highest impact on future space missions, enhancing medical readiness and self-sufficiency.

What Happens to the Affected Astronaut: Recovery and Investigation

Once Crew-11 lands, the affected astronaut undergoes comprehensive medical evaluation. That's when NASA gets the diagnosis it couldn't obtain in orbit. The astronaut sees specialists, undergoes imaging, receives whatever treatment is necessary, and begins recovery.

We won't know details publicly unless the astronaut chooses to share them or NASA releases a statement. That's appropriate. Privacy matters, especially in medical situations. But privately, NASA will conduct a thorough investigation. The space agency will review what happened, when it started, what symptoms or signs indicated a problem, and what the actual diagnosis is. NASA will assess whether the condition would have worsened in microgravity, whether bringing the crew home early was the right call, and whether any changes are needed to onboard medical protocols or training.

That investigation will inform how NASA approaches future medical concerns in space. It's part of the agency's continuous improvement cycle. Every mission, every decision, every event—expected or unexpected—teaches NASA something about operations in space.

For the affected astronaut, the priority is health and recovery. Astronauts are professionals who understand that mission schedules are secondary to wellbeing. Cutting a mission short isn't a failure. It's a decision made in consultation with the person affected, reflecting what's best for their health.

The Broader Picture: NASA's Medical Infrastructure in Space

James Polk's statement about ISS having a "robust suite of medical hardware" is technically accurate but highlights the limitations. The ISS medical system includes diagnostic equipment that would be impressive in, say, a remote clinic in a developing country. But it's not a general hospital.

Aboard the ISS, medical capabilities include:

- Diagnostic equipment: Basic blood analysis, ultrasound imaging, and vital sign monitoring

- Medications: Pain management, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and treatments for common spaceflight-related issues

- Surgical supplies: Materials for emergency care and wound treatment

- Telemedicine systems: Real-time communication with flight surgeons and specialists on Earth

- Physical recovery: Treadmills and resistance equipment to maintain bone and muscle mass

What ISS doesn't have includes advanced imaging like CT or MRI, comprehensive laboratory testing, specialist consultations (except by video), or surgical capabilities for complex procedures. Those limitations are inherent to the environment. You can't run a CT scanner in microgravity. The physics don't work.

NASA has spent decades optimizing what's possible with those constraints. The telemedicine capability is world-class. Flight surgeons can consult with specialists in real-time, review medical images sent from orbit, and guide astronauts through diagnostic procedures. But there's a ceiling to what's possible. When that ceiling is reached, the better option is getting the astronaut to Earth-side medical care.

Future ISS replacements or lunar and Mars habitats will need more advanced medical capabilities. As missions get longer and take humans farther from Earth, the medical infrastructure has to scale accordingly. The Crew-11 decision will likely inform those future designs.

Estimated data shows that 30% of ISS experiments can be paused and resumed, 25% are delayed, 20% are transferred to remaining crew, and 25% are critical and rescheduled. Estimated data.

Training and Preparation: Did Crew-11 Know How to Handle This?

Astronaut training includes emergency procedures and medical response. Crew members train for medical emergencies, learn basic first aid, and understand how to manage health issues in space. But training for an undiagnosed medical condition is different. You can prepare for what you expect. You can train for specific scenarios. But unexpected health changes require judgment and decision-making by the affected person, their crewmates, and medical professionals on Earth.

Crew-11 included experienced astronauts. These aren't rookie flyers encountering their first anomaly. Their training equipped them with the knowledge and procedures to report medical concerns through proper channels. The medical issue that emerged on January 7 was reported, documented, and escalated through NASA's established protocols. That worked exactly as intended.

Future crews might receive additional training focused on medical self-assessment and diagnostic support tools. There's always room for improvement. But the existing system handled this situation appropriately. The crew reported a concern. Medical professionals evaluated it. A decision was made. The process worked.

International Implications: The ISS Partnership and Crew Decisions

The ISS is a collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency, Japan's space agency, and the Russian space agency. Crew rotations involve coordination between these partners. When NASA decides to end a mission early, that decision affects the entire program.

Russian cosmonauts aboard the ISS depend on the orbiting laboratory's systems, which are maintained by international crew members. The ISS experiments involve contributions from multiple nations. Launch decisions depend on coordination between partners. NASA didn't make the Crew-11 call unilaterally, even though the affected astronaut is American and the majority of the crew works for NASA. The decision was made in consultation with international partners.

That partnership is something often overlooked in discussions of space exploration. The ISS exists because countries that were once rivals agreed to cooperate on science and exploration. That cooperation persists even during periods of geopolitical tension. When health and safety are at issue, international partnerships align. The commitment to crew safety transcends politics.

Accelerating Crew-12's launch requires coordination with Russia and ESA, since the ISS schedule is jointly planned. Those conversations are happening quietly, but they're happening. International space programs trust each other's judgment on crew health and medical decisions. If NASA says an astronaut needs to come home, the partners accept that judgment.

Psychological Factors: The Crew's Perspective on an Unexpected Early Return

Imagine training for six months, launching to space, spending five months in orbit conducting important work, and then being told you're coming home a month early due to a medical concern with a crewmate. That's a psychological adjustment.

For the affected astronaut, there's likely a mix of concern about their health, relief at returning to Earth's medical capabilities, and perhaps disappointment at not completing the full mission. For their crewmates, there's support for their colleague, acceptance of the situation, and their own adjustments to the changed timeline.

Astronauts are professionals trained to adapt. Mission parameters change. Astronauts handle it. But that doesn't mean there's no psychological component. Humans aren't robots. They have feelings about disrupted plans and unexpected changes. NASA's medical and psychological support teams work with returning crews to help them process these experiences.

There's also the broader psychological impact on the astronaut corps. When NASA prioritizes crew health over mission objectives, it sends a clear message about organizational values. That message matters. It tells current and future astronauts that their wellbeing is genuinely important, not just rhetoric. That builds trust in the organization and confidence that NASA will make good decisions when health and safety are at stake.

Future Missions and Deep Space Exploration: What This Decision Signals

NASA is planning lunar missions under the Artemis program and eventual Mars exploration. Those missions will be longer, farther from Earth, and with even more limited medical resources than the ISS. The Crew-11 decision provides important data about how NASA prioritizes health in space.

For lunar missions, astronauts will be on the surface for extended periods. For Mars missions, they'll be months away from Earth with zero possibility of emergency evacuation. The medical decisions NASA makes now—including the decision to bring Crew-11 home early—inform how the agency will approach health monitoring and medical readiness for future deep space exploration.

One outcome of this event might be accelerated development of advanced medical diagnostic tools suitable for spaceflight. NASA might invest in compact MRI technology, more sophisticated blood analysis capabilities, or AI-assisted diagnostic systems that can guide astronauts through medical evaluation with minimal equipment. These tools would serve the ISS immediately and support deep space missions in the future.

The decision also reinforces that astronaut health is non-negotiable. Future missions will be planned with that principle firmly established. Crews will be trained assuming that medical issues might prompt early return decisions. Mission planners will build in the contingency that a critical crew member might need to come home unexpectedly.

ISS Research Impact: What Gets Interrupted or Delayed

The ISS hosts hundreds of experiments at any given time. Some are short-term investigations that might be completed during Crew-11's tenure. Others are long-term studies spanning months or years. When the crew changes unexpectedly, research continuity becomes a question.

Some experiments can be paused and resumed. Others require specific conditions that might not be met again for weeks or months. Some experiments need human hands—growing protein crystals, tending biological samples, or operating equipment. With an abbreviated Crew-11 mission, some of that work gets transferred to the remaining crew or delayed until Crew-12 arrives.

NASA coordinates research priorities based on crew availability. The most critical investigations—those that can't wait—get scheduled first. Less time-sensitive research gets adjusted. It's not ideal for scientists waiting for their results, but it's manageable. Thousands of experiments have been conducted on the ISS over the years. The program has developed processes for accommodating schedule changes.

Research teams working with affected experiments will be notified of the change and adjusted timelines. They'll figure out how to proceed with partial data, modified procedures, or rescheduled work. This happens periodically in long-running research programs. It's frustrating, but it's part of the cost of doing research in the most extreme environment humans regularly access.

Public Communication: How NASA Handled the Announcement

NASA's communication strategy for the Crew-11 announcement was deliberate. The agency released information promptly, acknowledged that more details would come within 48 hours, and provided context through statements from leadership. That transparency builds public trust and prevents misinformation from filling the information vacuum.

NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman's statement and Chief Health Officer James Polk's explanation gave the public confidence that this was a thoughtful decision, not a crisis. The space agency didn't undersell the situation or claim everything was perfect. It also didn't overdramatize the event. The messaging was proportionate and professional.

The decision not to disclose the affected astronaut's identity or the specific medical condition maintains privacy while providing enough information for public understanding. That balance is important. Astronauts are public figures, but they deserve medical privacy. The public deserves transparency about how NASA operates, but not at the cost of invading individuals' medical situations.

This communication approach will likely become a template for future medical events in space. NASA has now made a public statement about a medical decision in spaceflight. Future similar situations will reference this precedent, and the public will be prepared for NASA to handle them with similar transparency and professionalism.

Lessons Learned: What This Event Teaches the Space Industry

Every unexpected event in human spaceflight produces lessons. The Crew-11 early return will teach NASA, other space agencies, and commercial spaceflight operators several things.

First, the decision demonstrates that health concerns in space require immediate escalation and decision-making, not procrastination. NASA didn't wait to see if the condition would resolve. Once a medical issue was detected that couldn't be properly diagnosed in orbit, the agency moved decisively.

Second, the event shows that early returns due to medical reasons are operationally feasible. Space X's Crew Dragon can return a crew to Earth in a few days. The infrastructure exists. The procedures are tested. It's not an emergency measure that risks lives. It's a routine operation that happens to be deployed for an unusual reason.

Third, the decision validates the telemedicine and medical decision-support systems NASA has built. Those systems worked. Medical professionals on Earth reviewed information from orbit, made sound judgments, and recommended a course of action that NASA executed.

Fourth, the event reminds us that astronauts are human. They get sick. They develop unexpected health issues. The organization that sends humans into space has a responsibility to bring them home safely if health requires it. Crew-11's early return isn't a failure of astronaut selection, training, or preparation. It's evidence that the system prioritizes human wellbeing.

Looking Ahead: The Next Six Months for ISS Operations

The immediate future of ISS operations involves several moving pieces. Crew-11 will return home in the coming days. Three crew members will remain, maintaining the station until Crew-12 arrives. Crew-12 will launch earlier than originally planned, likely in late January or early February. For a few days, there will be overlapping crews—old and new—aboard the ISS. Then Crew-11's departure will be complete.

After that, normal ISS operations resume with a full six-person crew. The affected Crew-11 astronaut will complete medical evaluation, recover, and presumably resume their career at NASA. Their crewmates will complete their mission as mission specialists assigned to stay longer, or they'll return with the rest of Crew-11. The ISS will continue its role as humanity's laboratory in space.

Beyond the immediate schedule, the ripple effects of this decision will influence how NASA plans future missions, how the agency trains crews, and how it plans medical infrastructure for deep space exploration. One crew's unexpected early return becomes a data point informing all future spaceflight operations.

The Bigger Story: Trust in Human Spaceflight

At its core, the Crew-11 early return is about trust. Astronauts trust NASA to make good decisions about their health. The public trusts NASA to operate human spaceflight safely and responsibly. International partners trust NASA's judgment about the ISS. When an unexpected health issue arises, that trust is tested.

NASA passed the test. The agency recognized a situation it couldn't fully assess, made a decision that prioritized astronaut health, communicated that decision transparently, and executed it professionally. That's how you maintain trust in human spaceflight.

Space exploration is inherently risky. Humans operate in an environment that will kill them in seconds if protection fails. That reality requires exceptional standards for decision-making, training, and safety culture. NASA's response to Crew-11's medical concern demonstrates those standards in practice.

This event won't make headlines a year from now. But it matters. It matters to the astronauts who will fly future missions knowing that their health is genuinely prioritized. It matters to the scientists whose research depends on ISS operations. It matters to the international partners who depend on NASA's judgment. And it matters to the public that funds this endeavor and trusts it with human lives.

FAQ

What prompted NASA's decision to end Crew-11's mission early?

NASA detected a medical concern with one of the five Crew-11 astronauts on January 7, 2025. The ISS is equipped with diagnostic tools, but they weren't sufficient to fully diagnose the condition. Without a proper diagnosis, NASA couldn't determine whether the microgravity environment would worsen the astronaut's health. Out of caution, the agency decided to bring the entire crew home so the affected astronaut could receive comprehensive medical evaluation on Earth.

Is the affected astronaut in danger?

No. NASA's Chief Health Officer James Polk described the affected astronaut as "absolutely stable." This means vital signs are normal, consciousness is clear, and the condition isn't acutely life-threatening. The decision to return early reflects a precaution, not an emergency. The crew will return in the coming days through normal procedures, not emergency evacuation.

Why can't NASA diagnose the condition aboard the ISS?

The ISS has a robust medical system for a space station, including basic diagnostic equipment like ultrasound, blood analysis, and vital sign monitoring. However, it lacks advanced imaging like CT scans or MRI machines, cannot perform comprehensive laboratory testing, and doesn't have specialist consultation beyond telemedicine. For conditions requiring detailed diagnosis, the ISS resources are insufficient. Patients on Earth experiencing similar diagnostic uncertainty would often be hospitalized. NASA made the judgment that bringing the crew home to Earth-side medical care was the right decision.

How does this affect ISS operations?

When Crew-11 returns, three crew members will remain aboard the ISS: two Russian cosmonauts and one American astronaut. Three people can maintain the station's critical systems and conduct essential research, but it's the minimum staffing level. NASA is considering accelerating Crew-12's launch from mid-February to earlier in January or February, reducing the period of understaffing. This cascades through NASA's schedule but is manageable with coordination between the space agency and Space X.

Has NASA ended a mission early due to medical reasons before?

This is the first time NASA has officially ended a crewed mission early specifically citing a medical concern. However, health issues in space aren't unprecedented. Astronauts have experienced illness and medical events during missions in the past, which were usually managed in place or resulted in earlier-than-planned return decisions that weren't publicly framed as "medical reasons." This announcement reflects NASA's transparency about the decision and the gravity with which the agency treats health in space.

What will happen to the affected astronaut?

Once returning to Earth, the astronaut will undergo comprehensive medical evaluation. They'll see specialists, receive any necessary imaging and testing, and get a definitive diagnosis. NASA will then assess whether the condition would have worsened in microgravity and whether bringing them home early was the right call. Unless the astronaut chooses to share details publicly, the specifics of their medical situation will remain private. Recovery and return to normal duties will be based on the diagnosis and medical recommendations.

Could this set a precedent for future early returns?

Yes. This decision establishes that NASA will end missions early if medical concerns cannot be properly assessed and managed in space. Future crews will understand that health is non-negotiable and that NASA prioritizes astronaut wellbeing over mission schedules. The decision also informs NASA's approach to future missions and may accelerate development of more advanced medical diagnostic tools for spaceflight.

How does this affect the international partnership aboard the ISS?

The ISS is a joint facility involving NASA, European Space Agency, Japanese space agency, and Russian space agency. NASA coordinated the early return decision with international partners. Accelerating Crew-12 requires agreement from Russia and other partners, since ISS scheduling is jointly planned. The incident reinforces that crew health transcends politics and that international partners trust each other's judgment about medical decisions in space.

Key Takeaways

- This is the first time NASA has officially ended a crewed ISS mission early due to a medical concern, signaling the agency's commitment to astronaut health over mission schedules

- The affected Crew-11 astronaut is described as 'absolutely stable,' meaning the early return is a precaution, not an emergency evacuation

- The ISS lacks comprehensive diagnostic capabilities like advanced imaging and specialized laboratory testing, requiring return to Earth for proper medical diagnosis

- With Crew-11's departure, only three crew members remain aboard the ISS until Crew-12 arrives, creating staffing constraints that NASA is addressing by potentially accelerating Crew-12's launch

- The decision demonstrates how NASA's established protocols for crew health prioritization function in practice and will influence medical infrastructure planning for future deep space missions

Related Articles

- Navigating Unknown Terrain: NASA's Decision to Return Astronauts Home Amid Medical Concerns [2025]

- NASA Spacewalk Delay: Medical Concerns, ISS Operations & Crew Safety [2025]

- NASA Spacewalk Postponement: What Happened and Why [2025]

- Lazuli Space Observatory: The Private Space Telescope Revolution [2025]

- International Space Station Russian Segment: Leak Mystery Solved [2025]

![NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-s-crew-11-early-return-what-the-medical-concern-means-2/image-1-1767969607476.jpg)