The BBC's Quiet Pivot: Why Free YouTube Content Matters More Than You Think

For decades, the BBC operated like a fortress. Pay your £175 annual TV licence, and you could watch whatever you wanted on BBC One, BBC Two, and iPlayer. The system worked. It funded quality programming. People accepted it as part of British life, like complaining about the weather or queuing at Tesco.

Then something shifted.

Gen Z stopped watching traditional TV. They ditched iPlayer for TikTok, YouTube, and Netflix. The BBC watched its audience fragment. Licensing revenue stayed flat while production costs climbed. Something had to give.

So in February 2025, the BBC did something unexpected. It started launching free shows on YouTube.

This isn't a pivot toward chaos. It's strategic desperation wrapped in forward-thinking language. The corporation needed to reach viewers where they actually spend time, not where the BBC hoped they'd show up. YouTube has 2.7 billion monthly active users. iPlayer has maybe 15 million unique viewers per month. The math was brutal.

But here's where it gets complicated. Free YouTube content sounds great until you realize what it means for the TV licence. If people can watch BBC shows without paying, why pay at all? That's the question keeping BBC executives awake at night.

This article digs into what's happening, why it matters, and what comes next for public broadcasting. We'll explore the generational shift away from traditional TV, the economics of free streaming, and whether the TV licence system survives the next decade.

The stakes are bigger than BBC drama reruns. They're about whether public broadcasting can survive in an age where viewers expect free content everywhere.

TL; DR

- BBC launched free shows on YouTube in February 2025, targeting Gen Z audiences who avoid traditional TV.

- The TV licence fee remains £175 annually, but its necessity is increasingly questioned as free content proliferates.

- Gen Z watches 40% less traditional TV than older generations, creating an urgent need for the BBC to find new audiences.

- YouTube strategy risks alienating paying licence fee payers who fund quality programming while others watch free.

- Public broadcasting model faces existential crisis as streaming democratizes content access globally.

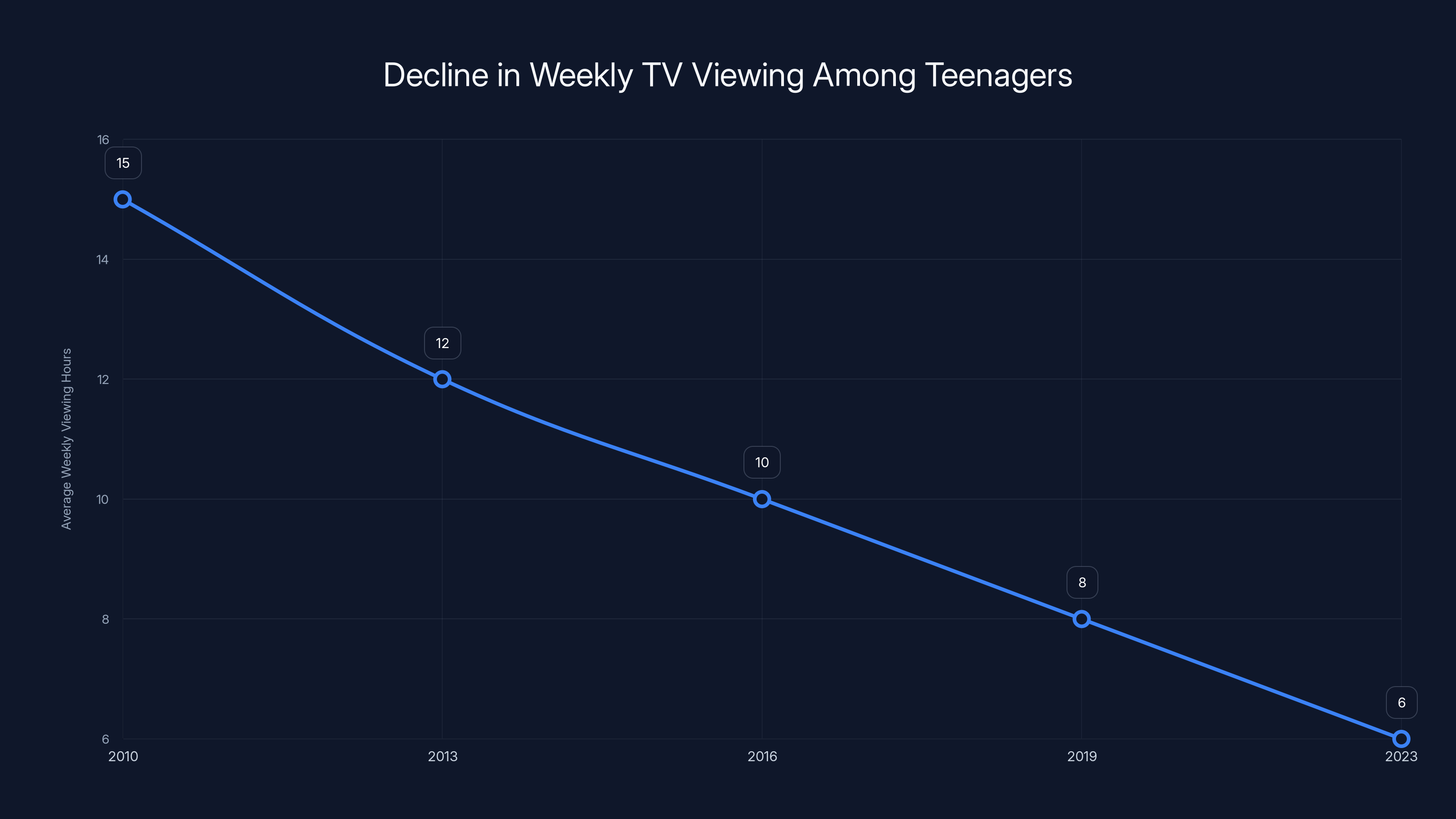

Teenagers' average weekly TV viewing has declined by 60% from 2010 to 2023, highlighting a significant shift in media consumption habits. Estimated data.

Why Gen Z Abandoned Traditional TV (And the BBC Can't Ignore It)

Let's start with the obvious: young people don't watch TV anymore. Not the traditional way, anyway.

The numbers are staggering. In 2010, the average teenager watched 15 hours of linear TV per week. Today? About 6 hours. That's a 60% decline in just over a decade. For BBC content specifically, viewing among under-25s has dropped even faster.

Why? It's not that Gen Z hates quality programming. They hate rigid schedules. They despise commercials. They loathe the idea of missing something because it aired at 9 PM on a Tuesday.

Netflix showed them an alternative: pick what you want, watch when you want, no ads, no filler. YouTube did something similar but added discovery and algorithmic recommendations. TikTok shortened the content window to snackable moments. Suddenly, waiting for the BBC to schedule your show felt quaint.

The demographic data is unforgiving. According to Ofcom's 2024 media consumption report, only 12% of 16 to 24-year-olds watched live TV on any given day. Compare that to 68% of adults over 65. The generational cliff is real.

This creates an existential problem for the BBC. The current licence fee model depends on a broad audience paying for content. But the audience shrinking fastest is the one with decades of potential licence payments ahead. It's losing future revenue, not just current viewers.

The BBC understood this threat. It couldn't force Gen Z to watch BBC One at a scheduled time. So it had to go where Gen Z already lived: YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and other platforms with algorithmic discovery and flexible viewing.

But here's the trap. YouTube doesn't fund content the way licence fees do. Advertisers pay pennies per thousand views. A YouTube video needs millions of views just to earn the production budget of a single episode. The economics are completely different.

So the BBC made a calculated choice. Launch free content on YouTube to capture attention, build audience size, then figure out monetization later. It's the playbook every streaming company uses. Netflix did it before going subscription-only. Amazon Prime Video still mixes free and paid.

The question isn't whether the strategy makes sense for audience growth. It obviously does. The question is whether it makes sense for the licence fee system that's supposed to fund it.

Understanding the TV Licence Fee Model and Why It's Under Pressure

The British TV licence is one of the world's most efficient funding mechanisms for public broadcasting. It generates roughly £3.7 billion annually, which funds BBC television, radio, and iPlayer.

Here's how it works in theory: every UK household with a TV must purchase an annual licence. It costs £175 (or £159 for black and white, if anyone still has those). The licence fee is then distributed to the BBC, which uses it to fund news, documentaries, drama, children's programming, and more.

The system has a clever democratic legitimacy. The BBC isn't funded by advertising (which distorts editorial priorities) or by rich shareholders (which introduces bias). It's funded directly by viewers who want it. If the public disagrees with how the BBC operates, they can theoretically refuse to pay.

In practice, that doesn't happen. The BBC is unpopular sometimes, but people still pay. Enforcement is relatively easy because watching live TV is illegal without a licence, and getting caught means fines up to £1,000.

But the model is crumbling for three reasons: declining live TV viewership, rising production costs, and competition from well-funded streaming services.

First, the viewership problem. If fewer people watch live TV, fewer people need a licence. The BBC has already exempted streaming-only viewers. You can watch iPlayer on-demand without a licence (though you need one for live streaming). This creates a natural erosion. As people shift to on-demand viewing, the licensing base shrinks.

Second, production costs have exploded. The BBC now competes with Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon for talent, locations, and post-production resources. A prestige drama that cost £5 million per episode ten years ago might cost £8 million today. Meanwhile, the licence fee revenue stays flat or grows slowly. The math doesn't work indefinitely.

Third, there's the value proposition problem. Why pay £175 for BBC content when Netflix costs £4.99 for unlimited movies and shows? When Disney+ offers Marvel and Star Wars? When YouTube is free?

The licence fee only makes sense if people believe public broadcasting is worth funding. That belief is weakening, especially among younger audiences who've never known a world without on-demand streaming.

The BBC's leadership saw these trends and decided YouTube content was necessary for survival. But it created a paradox: if the BBC gives away content for free on YouTube, why would anyone pay the licence fee?

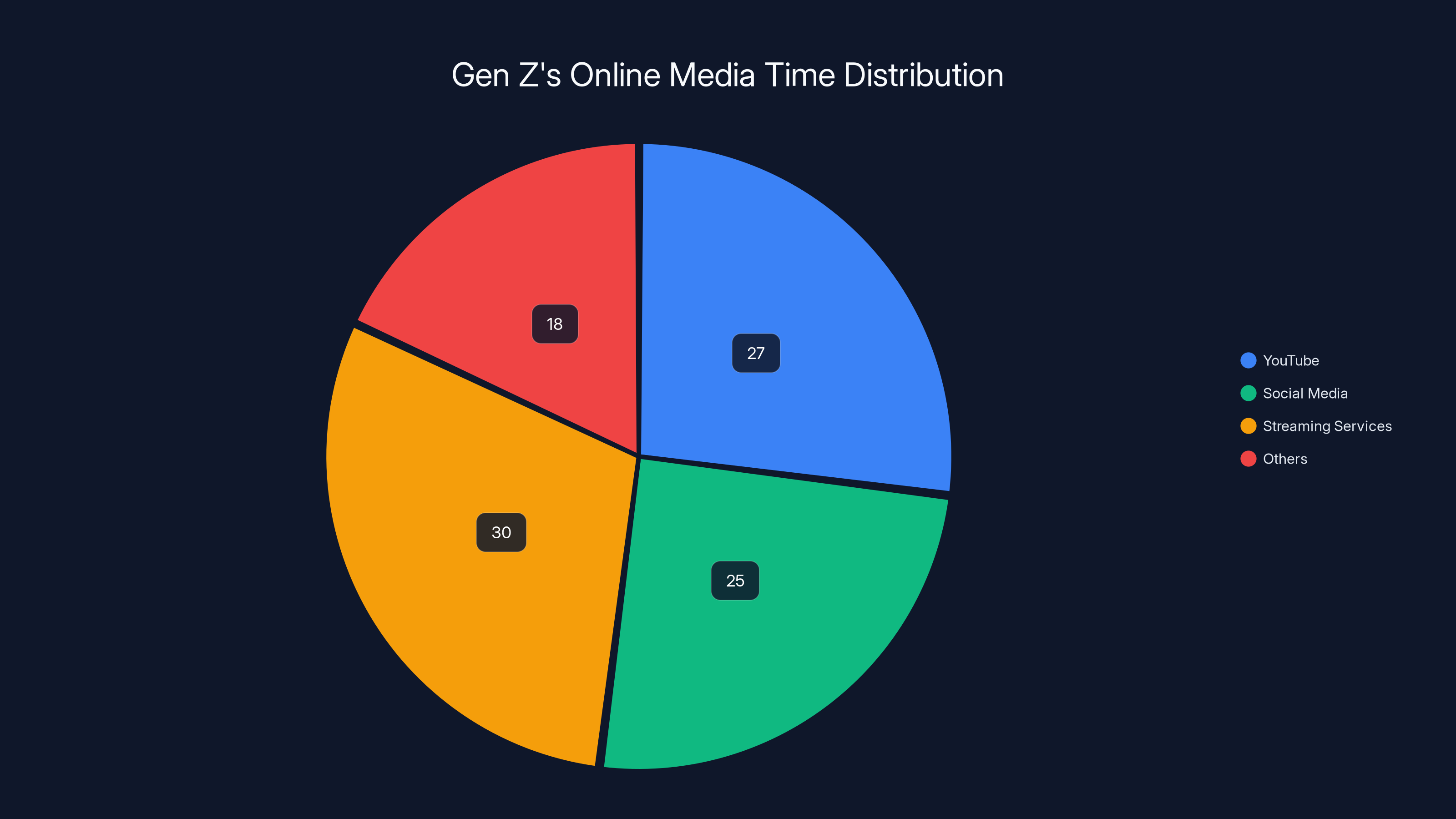

Gen Z spends approximately 27% of their online media time on YouTube, highlighting its importance as a platform for reaching this demographic. (Estimated data)

The YouTube Strategy: Free Content to Win Back Gen Z

The BBC's YouTube strategy isn't random. It's targeted and deliberate.

Starting February 2025, the BBC began uploading free episodes of popular shows directly to YouTube. We're talking about drama, comedy, documentaries, and entertainment. The content is the same quality as what BBC subscribers see on iPlayer, just distributed through a different platform.

The strategy has clear objectives:

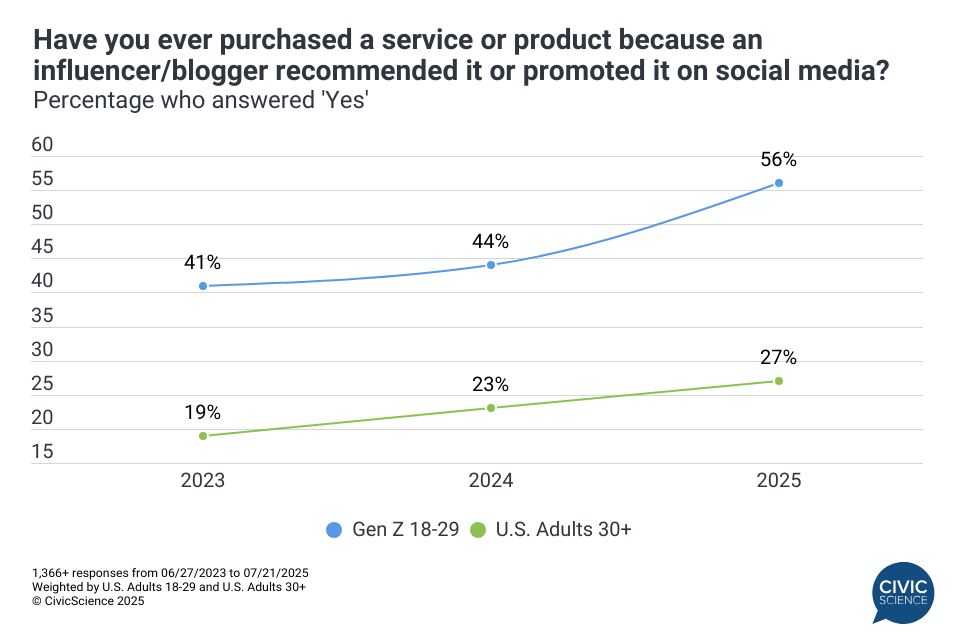

Reach young audiences on their native platform. Gen Z spends roughly 27% of their online media time on YouTube. That's where the attention lives. If you want their eyeballs, that's where you have to show up.

Build audience size through algorithmic discovery. YouTube's recommendation algorithm is phenomenally effective at surfacing content based on user behavior. A BBC drama uploaded to YouTube could end up in someone's recommendations even if they've never heard of the BBC. That's impossible with iPlayer, which requires active searching.

Create a funnel from awareness to subscription. YouTube viewers who enjoy free content might eventually subscribe to iPlayer for premium content, commercial-free experience, or exclusive shows. Or they might not. But at least the BBC had a chance to impress them first.

Compete on the platforms where streaming is happening. Netflix isn't waiting for viewers to come to them. Neither can the BBC. It has to meet audiences where they're already consuming content.

The economics are the interesting part. YouTube doesn't pay the BBC for the content. YouTube takes its cut from advertising revenue (roughly 45% of ad revenue goes to creators, 55% stays with YouTube). The BBC keeps whatever advertising revenue generates from its uploads.

For popular shows, this can be substantial. A heavily-watched drama might generate hundreds of thousands of dollars in YouTube ad revenue. But the BBC isn't primarily doing this for money. It's doing it for audience metrics.

In the attention economy, metrics matter. If a BBC show gets 5 million YouTube views, the BBC can point to that data and say, "Look, people want our content." Those metrics are valuable for political negotiations. They're valuable for attracting talent. They're valuable for convincing international broadcasters to buy BBC content.

But there's a complication. If the BBC freely distributes premium content on YouTube, it's competing against itself. Why subscribe to iPlayer if you can watch the same shows on YouTube for free?

The BBC is betting that enough viewers will migrate from YouTube to iPlayer that the net effect is positive. That's a big assumption. It assumes the audience conversion rate is high enough that lost YouTube ad revenue is offset by new iPlayer subscriptions (or licence fee willingness).

There's also the brand equity angle. If the BBC establishes itself as a major YouTube creator, it gains cultural relevance with Gen Z. It stops being the dusty public broadcaster their parents watched and becomes the creator they choose to follow. That perception shift is worth money in the long term.

The Core Problem: How to Fund Quality Content Without a Captive Audience

Here's where the strategy gets philosophically complex.

The TV licence works because it's mandatory. Every household either pays or stops watching live TV. That mandatory funding allows the BBC to invest in programming that wouldn't be commercially viable on a free advertising model.

A documentary about 15th century trade routes? Probably won't attract enough viewers to justify advertising-based funding. But it's valuable cultural programming, so the BBC makes it anyway using licence fee money.

A children's educational show with limited advertising appeal? Same situation. The licence fee subsidizes it.

This is the entire philosophical foundation of public broadcasting. You fund important programming that commercial broadcasters wouldn't touch because it's not profitable enough.

But YouTube doesn't support that model. YouTube rewards viral, engaging, high-view-count content. Niche documentaries and educational programming don't perform well algorithmically. They get buried in recommendations.

So the BBC has to choose. Does it make content optimized for YouTube's algorithm (trending, sensational, broad appeal)? Or does it stick with its mission (quality, culturally valuable, sometimes niche)?

Both strategies have costs. Algorithmic optimization waters down the BBC's quality brand. Ignoring algorithms means the YouTube content strategy fails and viewership doesn't grow.

The BBC seems to be threading this needle by uploading popular shows to YouTube while keeping some premium content exclusive to iPlayer. It's a middle path: enough free content to build YouTube audience, enough exclusive content to justify iPlayer subscription.

But middle paths often satisfy no one. People who want free content think the paywall is unfair. People who pay for iPlayer think they're subsidizing free viewers. And the BBC gets caught between audience growth and revenue generation.

There's also a global dimension. The BBC operates in competitive international markets. Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon are all trying to win viewers in the UK. If the BBC doesn't stay culturally relevant and easy to access, it loses relevance. The YouTube strategy is partly about staying in the competitive game.

How Free YouTube Content Affects the TV Licence Debate

The TV licence isn't universally loved. In fact, it's increasingly controversial.

Opposition comes from multiple angles. Young people resent paying for content they don't watch in a format they don't use. Older people on limited incomes question whether £175 is sustainable. People who exclusively watch on-demand wonder why they're funding a service designed for live TV. And critics argue the licence fee model is outdated.

Every few years, there's serious political discussion about replacing the licence fee with a subscription model or general taxation. These conversations have never succeeded, partly because the BBC's political defenders have been strong enough, and partly because there's no agreed-upon alternative that works better.

But the YouTube strategy changes the conversation. If the BBC admits its content is worth sharing for free on YouTube, how can it justify charging £175 annually through mandatory licensing?

The BBC's defense is that free YouTube content is marketing. It's designed to drive viewers to iPlayer and to demonstrate the BBC's relevance to Gen Z. The premium, comprehensive experience still lives on iPlayer and BBC broadcast channels.

But that argument gets weaker the more free content the BBC distributes. If someone can watch 70% of BBC content for free on YouTube, paying £175 feels less mandatory.

Politically, this creates vulnerabilities. Opponents of the licence fee now have ammunition: "The BBC itself admits its content doesn't require payment. Why should we mandate it?"

Supporters of the BBC have a counter-argument: "Licence fee revenue funds the production of that content. Free YouTube distribution is only possible because the licence fee paid for the production. Remove the licence fee, and the production budget disappears. YouTube content disappears."

Both arguments have merit. The tension is real and unresolved.

The BBC is essentially betting that free YouTube content will generate enough loyalty and growth that people will voluntarily want to support the BBC, even without a mandate. That's a noble bet, but it's unproven.

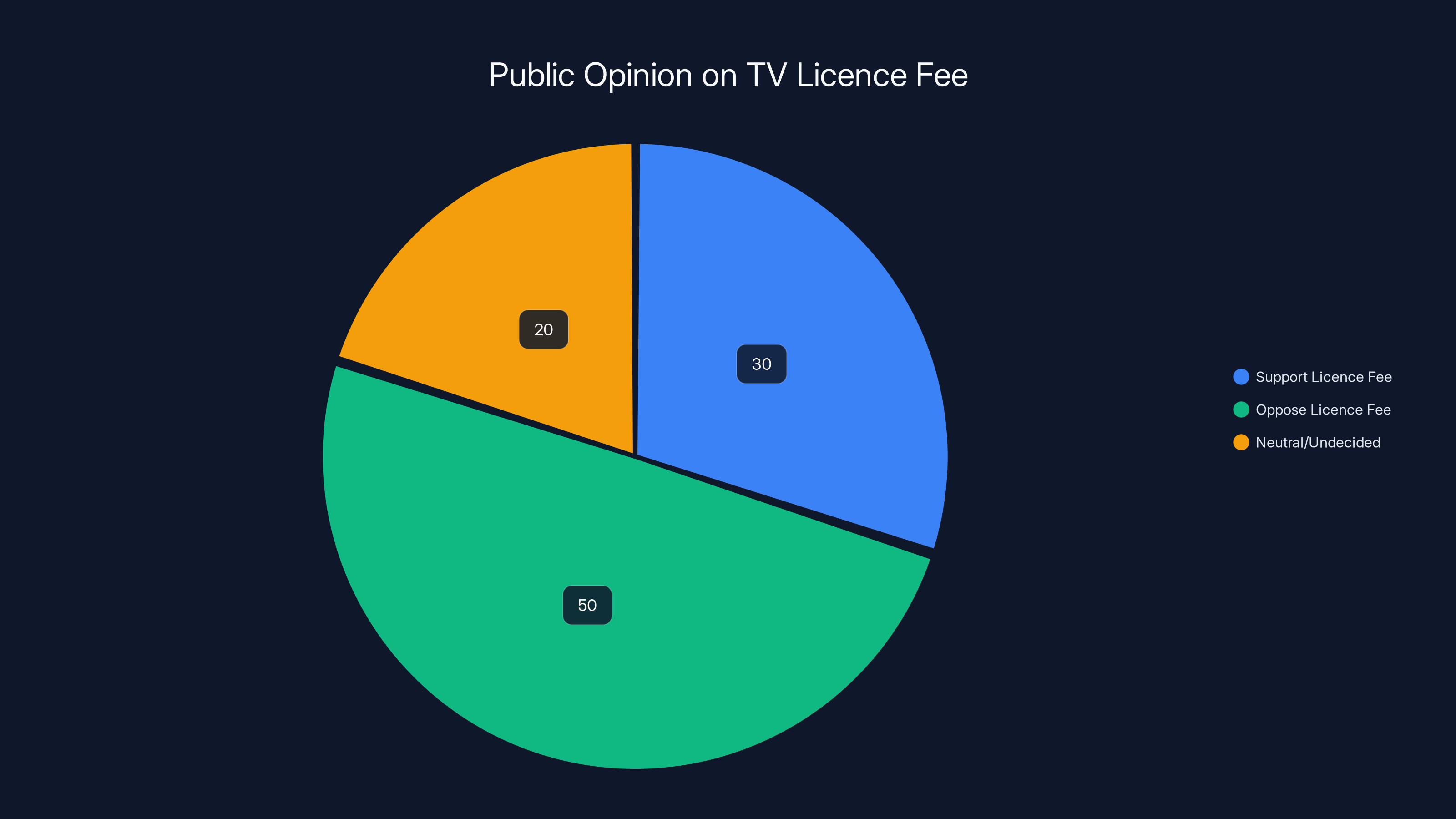

Estimated data suggests that 50% of the public opposes the TV licence fee, while 30% support it and 20% remain neutral or undecided.

The Generational Wealth Transfer Problem

Here's a demographic reality that the BBC leadership understands but rarely talks about openly.

The licence fee system is aging. The viewership skews heavily toward people over 65. That demographic is loyal, pays reliably, and watches enormous amounts of live BBC content. They're the perfect license fee customers.

But they're also aging out of the system. In 20 years, many of today's loyal 65-year-olds will no longer be watching anything. Meanwhile, Gen Z is entering adulthood having never watched live BBC content, never understood the value of the licence fee, and having countless free alternatives.

If the BBC can't convert Gen Z to licence fee payers (or at least maintain their willingness to fund public broadcasting), the revenue base collapses. It's not a subtle problem. It's an existential demographic cliff.

The YouTube strategy is partly an answer to this. If the BBC can introduce Gen Z to quality content through YouTube, maybe they'll remain loyal consumers as they age. Maybe they'll eventually support the BBC through subscription or licensing, even if not right now.

It's a long-term play. The BBC is investing in audience acquisition that might not pay off financially for 10 to 15 years. By then, Gen Z will have more disposable income and more settled media habits.

But it requires patience and sustained investment. The BBC has to keep making free YouTube content even if the immediate ROI is poor, trusting that the long-term demographic payoff will be worth it.

That's difficult for any organization, especially a publicly-funded one that gets second-guessed by politicians every few years.

Comparison: How Other Global Broadcasters Are Responding

The BBC isn't alone in this crisis. Public broadcasters worldwide are facing the same pressure from streaming and audience fragmentation.

Across Europe, national broadcasters have gone aggressively into YouTube and streaming. Germany's ARD and ZDF created Mediathek, a streaming platform competing directly with Netflix. France's TF1 and France Télévisions launched their own apps. Italy's RAI has Tv Rai. None of them charge mandatory fees for on-demand content anymore. They've softened the public broadcasting model.

In Australia, the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) launched ABC iView as a free streaming service, then added free YouTube content. It's a direct parallel to the BBC's strategy.

In Canada, the CBC created a free streaming service (CBC Gem) but still charges through mandatory fees. It's struggling with the same contradiction.

In America, public broadcasting never had a mandatory fee system like the UK. Instead, PBS depends on government appropriations and viewer donations. It's less efficient but more politically vulnerable. Each year, debates about defunding PBS come up, and donors can vote with their wallets.

The U.S. model shows what happens when public broadcasting loses mandatory funding. PBS has a smaller budget, produces less original content, and relies heavily on repeats and international coproductions. It's still excellent, but smaller in scope than the BBC.

The key lesson is that free streaming content and mandatory funding are increasingly incompatible. Audiences don't understand why they should pay if they can access the same content for free. So broadcasters have to choose: lean into the paid model (like Netflix and Disney+) or lean into the free model (like YouTube and ad-supported services).

The BBC is trying to do both, which is difficult but not impossible. The strategy requires either enough exclusive content on iPlayer to justify paid access, or enough audience loyalty to YouTube to generate advertising revenue that approaches production budgets.

Neither path is guaranteed to work. But the BBC is smarter than to rely on a single strategy, so it's doing both: building free audiences on YouTube while maintaining premium experiences on iPlayer.

The Advertising Question: Can YouTube Revenue Replace Licence Fees?

Let's talk about the financial math directly.

The BBC's current licence fee generates £3.7 billion annually. YouTube's typical advertising revenue for media publishers is roughly 20 to 40 dollars per thousand views, depending on audience quality, content type, and geography. For UK audiences (which advertisers value highly), the rate is typically on the higher end.

To generate £3.7 billion in YouTube ad revenue, the BBC would need roughly 100 to 150 billion annual YouTube views. For context, the most-viewed YouTube channels (like SET India and Kids Diana Show) get about 200 billion annual views combined. Achieving that level would require the BBC to be the single most-watched channel on YouTube by a huge margin.

That's not realistic. The BBC will likely get 10 to 30 billion YouTube views annually from free content, generating £200 to £1,200 million in advertising revenue. That covers some production costs, but not most.

The math doesn't work if you're trying to replace the licence fee with YouTube advertising. You'd need to be TikTok or YouTube itself to generate that kind of volume.

This is why hybrid models exist. The BBC uses licence fees for content production, then monetizes that same content on YouTube with advertising. The licence fee is the primary funding source. YouTube is supplementary income.

But this creates a problem for licence fee justification. If the BBC is using licence fees to produce content it then distributes for free on YouTube with advertising revenue going to YouTube (which takes a cut), who benefits? The BBC gets some advertising revenue. YouTube benefits more. The public gets free content. Licence fee payers subsidize all of it.

From a pure economics standpoint, this is awkward. Licence fee payers are funding the production of content that advertisers then monetize, with YouTube taking a massive cut. The licence fee payer loses twice: they pay, and then they watch ads on the free version.

There are ways to solve this. The BBC could make YouTube content ad-free for licence fee payers (using authentication). Or it could shift more content to iPlayer exclusively and use YouTube only for marketing clips. Or it could pursue a YouTube Premium-style partnership where creators get a better revenue share.

None of these solutions are perfect, but they're better than the current situation where the BBC funds production, YouTube captures revenue, and licence fee payers get nothing extra.

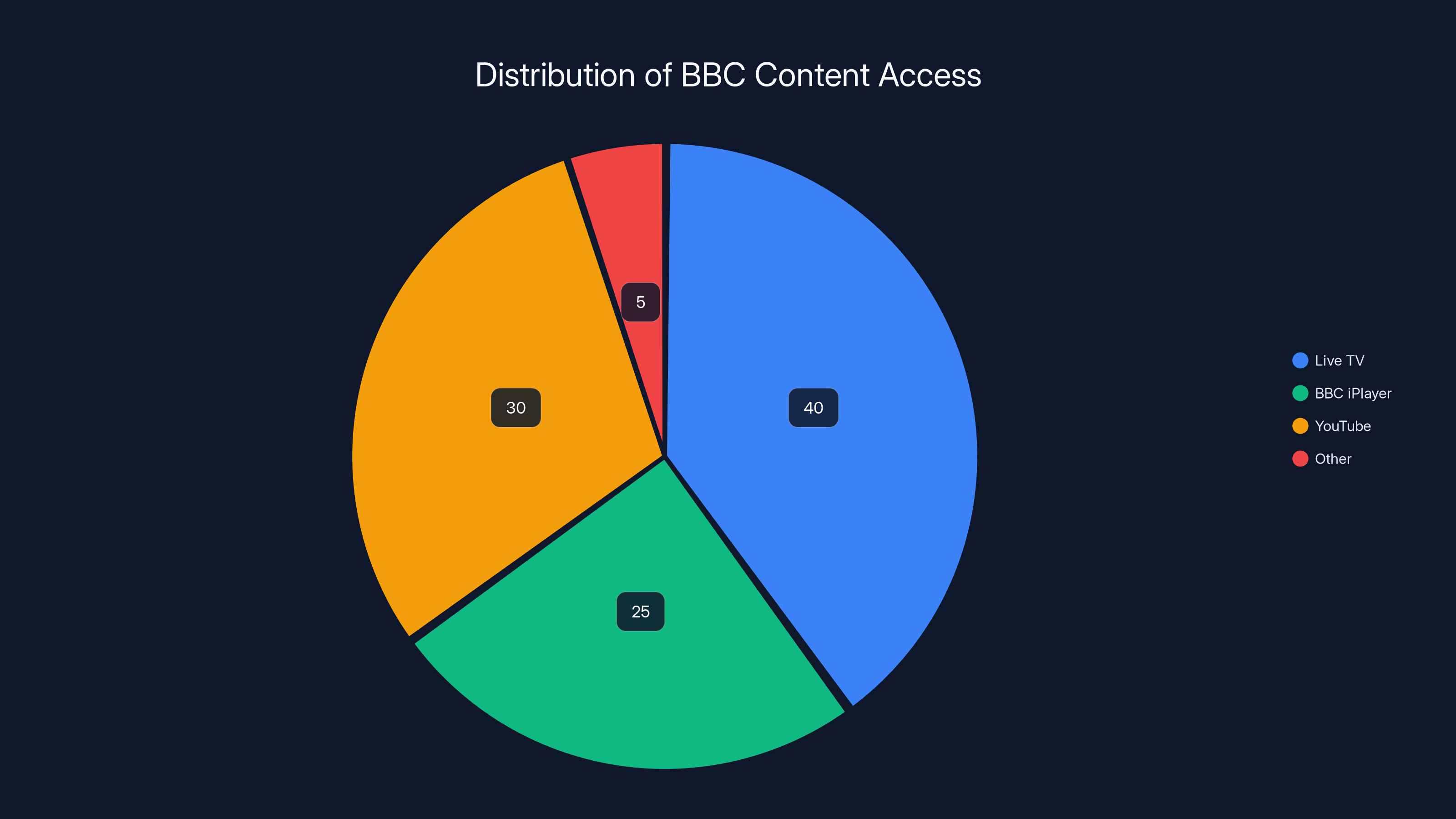

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of BBC content is accessed through YouTube, reflecting a shift in viewing habits, especially among younger audiences.

What Happens to iPlayer in a Free Content World?

iPlayer is the BBC's streaming platform. It launched in 2007 as a catch-up service for people who missed broadcast TV. Over time, it evolved into a comprehensive on-demand streaming service with exclusive content, just like Netflix.

Currently, iPlayer is free to anyone with a valid TV licence. You don't pay extra for it. The licence fee covers your access.

But iPlayer is expensive to run. It requires servers, bandwidth, customer support, and development. The BBC has invested heavily in making iPlayer competitive with Netflix in terms of user experience and content depth.

If the BBC floods YouTube with the same content that's on iPlayer, iPlayer becomes less attractive. Why create an account, deal with login requirements, and navigate a custom interface when you can find the same shows on YouTube with zero friction?

iPlayer's value proposition weakens. That's a real problem for the BBC's long-term strategy.

One solution is to make iPlayer premium. Offer exclusive content on iPlayer that doesn't appear on YouTube. Make iPlayer ad-free while YouTube has ads. Add features like offline downloads that YouTube doesn't support.

The BBC has hinted at moving this direction. But it requires accepting that iPlayer is a closed garden for people who subscribe (or have licence fees), while YouTube becomes the free, ad-supported experience. It's a bifurcation of the audience.

Another approach is to make iPlayer subscription-based for non-licence-fee payers. Charge international viewers or people without UK TV licences a subscription fee to access premium content. The BBC has tested this in international markets.

But none of these moves are simple. Each one involves tradeoffs: limiting content availability, fragmenting the audience, or introducing new pricing complexity.

The International Angle: BBC Studios and Global Revenue

Here's something people often forget: the BBC has a commercial arm called BBC Studios. It produces content, sells it internationally, and generates commercial revenue separate from licence fees.

BBC Studios sells shows to broadcasters around the world. It licenses format rights. It produces content for international clients. It generates roughly £300 to £400 million in annual revenue.

This commercial revenue is actually crucial for BBC's strategy. The BBC uses commercial revenue to cross-subsidize licence-fee-funded content that wouldn't be commercially viable.

When the BBC puts content on YouTube, it potentially impacts BBC Studios' ability to sell that content internationally. A broadcaster in Australia might not pay for the rights to a show if it's already available free on YouTube globally.

So the YouTube strategy has hidden costs to the BBC's commercial operations. The BBC is essentially cannibalizing its own international sales to build YouTube audience.

The BBC is probably accepting this as a necessary trade-off. Building massive YouTube audiences is valuable for brand power and cultural relevance, even if it costs some international licensing revenue.

But it's a cost that politicians and critics should understand. The BBC isn't just gambling with licence fee revenue. It's also sacrificing commercial revenue to pursue a growth strategy that might not pay off.

The Regulatory Consideration: What Does Ofcom Think?

Ofcom is the UK broadcasting regulator. It oversees the BBC and sets the framework for public broadcasting.

Ofcom has been skeptical of the licence fee model for years. It's published reports arguing that the fee is outdated and that younger audiences don't see the value in it. Ofcom's position is basically, "If the BBC wants to survive, it needs to justify its funding and adapt to audience behavior."

So from Ofcom's perspective, the BBC's YouTube strategy is not just smart—it's necessary for survival. The regulator would likely support moves that make the BBC more accessible and relevant to young people.

However, Ofcom also cares about fair competition. If the BBC uses licence fee revenue to produce content and then distribute it for free on YouTube, does that create unfair competition for commercial broadcasters?

Commercial broadcasters like ITV and Sky pay for content through advertising and subscriptions. They compete with Netflix and Disney+ on those terms. The BBC using licence fees to fund free YouTube content might be seen as unfair competitive advantage.

Ofcom has to balance these concerns: supporting the BBC's adaptation while protecting fair competition. It's a delicate position.

Currently, Ofcom seems to be leaning toward supporting the BBC's digital transformation, but this could change if licence fee revenue shrinks significantly or if commercial broadcasters complain loudly.

Estimated data suggests that introducing a subscription for non-licence holders could have the highest revenue impact, while maintaining a free service with a TV licence maximizes user base.

The Political Reckoning: Will the TV Licence Survive?

Let's talk about politics directly. The TV licence is a political football in the UK.

Conservative politicians tend to be skeptical of the BBC and hostile to the licence fee. They argue it's an outdated tax that stifles free market competition. Labour politicians tend to support public broadcasting but are skeptical about making the BBC too much like a commercial entity.

Every decade or so, there's a serious debate about scrapping the licence fee entirely. These debates have never resulted in abolition, but they show sustained political pressure.

The YouTube strategy actually helps the BBC politically. It demonstrates that the BBC is adapting to modern audience behavior and not resting on its monopoly over live TV access. If the BBC did nothing and just complained that young people don't watch, politicians would have an easy argument for abolishing the fee.

But the YouTube strategy also exposes the fee to new criticism. If the BBC is giving content away for free, why should people pay for it?

The BBC's best political defense is probably something like this: "We're using licence fee revenue efficiently to produce world-class content. We're distributing that content widely to serve our public mission. Some of that distribution is free (YouTube) to reach audiences we wouldn't otherwise connect with. Some is paid (iPlayer) to generate revenue and create premium experiences. The licence fee funds the production. Revenue from YouTube advertising and iPlayer subscriptions supplements that. Together, they create a sustainable model for public broadcasting in a digital world."

It's a complex message. Politicians prefer simple ones. So the BBC is vulnerable on this front.

My guess is that the licence fee survives the next decade because there's no political consensus on a replacement. But it probably becomes optional at some point. Maybe you opt-in to the licence fee rather than having it automatically deducted from council tax. That's a middle path that could happen.

The Viewer Perspective: What Should You Actually Pay For?

If you're an average UK household trying to decide whether the TV licence is worth £175 annually, here's the logic:

Arguments for paying:

- BBC content is genuinely high-quality. News, documentaries, and drama sets standards that commercial broadcasters struggle to match.

- Without licence fees, the BBC would make less ambitious content. You'd get more formulaic programming because that's what makes money.

- Public broadcasting serves a cultural function. It's not just about entertainment. It's about maintaining shared cultural experiences and quality journalism.

- iPlayer is a genuinely good streaming service. If you use it regularly, the per-month cost is similar to Netflix.

Arguments against paying:

- If you watch no live BBC television, the fee feels like you're paying for something you don't use.

- YouTube now offers free BBC content, so paying feels optional.

- Streaming services like Netflix, Disney+, and others offer more content for £5-15 monthly.

- The BBC doesn't create content you can't find elsewhere. It's good, but not irreplaceable.

Honestly, the value proposition depends on your behavior. If you watch live BBC TV, use iPlayer regularly, or value public broadcasting enough to support it culturally, the fee is reasonable. If you watch no BBC content and use only YouTube and Netflix, the fee is obviously a waste of money.

The BBC's challenge is converting people in the second group. The YouTube strategy is an attempt to do that by introducing them to BBC quality for free and hoping they'll eventually appreciate the mission enough to support it.

It might work. It might not. The outcome depends on factors the BBC can't fully control, like audience behavior and political will.

What Happens Next: Three Possible Futures

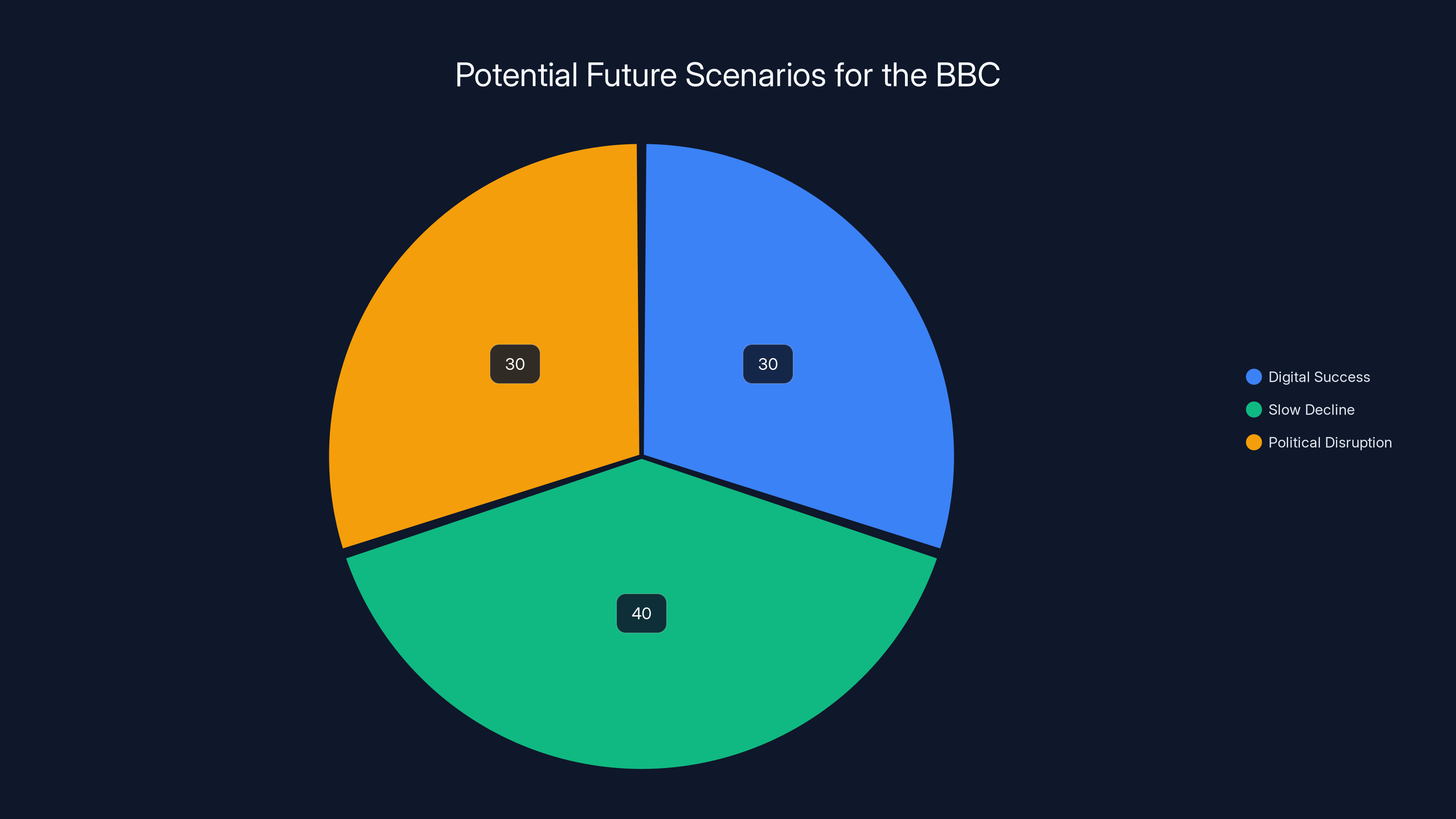

The next five to ten years will determine whether the BBC's strategy succeeds or fails. Here are three plausible scenarios:

Scenario 1: Digital Success The BBC becomes a major YouTube creator, builds enormous audiences, and converts significant percentages of YouTube viewers to iPlayer subscribers or licence fee payers. YouTube advertising revenue grows to cover 30-40% of production costs. Gen Z develops loyalty to BBC content and sees the licence fee as valuable. The system stabilizes with a hybrid model: licence fees fund core operations, YouTube builds audience and generates advertising revenue, iPlayer subscriptions serve premium users. Public broadcasting survives and adapts.

Scenario 2: Slow Decline The BBC's YouTube strategy succeeds in reaching Gen Z, but conversion rates remain low. Most YouTube viewers don't subscribe to iPlayer or develop loyalty. Advertising revenue grows too slowly to offset production costs. Meanwhile, licence fee revenue declines as older audiences age out and younger cohorts refuse to pay. The BBC gradually shrinks over 10-15 years, producing less content, cutting budgets, and losing competitive edge. Eventually, it becomes a niche player rather than a major cultural force.

Scenario 3: Political Disruption Political pressure builds against the licence fee. A government decides to make the fee optional or replaces it with general taxation. If optional, the fee collapses dramatically as only loyal viewers pay. If replaced by taxation, the BBC gets more stable but smaller funding. Either way, the BBC has less money to produce content and becomes less competitive. The YouTube strategy becomes necessary for survival rather than growth.

Each scenario has different implications for viewers. In Scenario 1, the licence fee probably survives but evolves. In Scenario 2, it gradually disappears. In Scenario 3, it gets replaced by something else entirely.

My assessment is that Scenario 2 is most likely. The BBC's YouTube strategy will have meaningful success in audience reach but limited success in conversion. Revenue will decline slowly but steadily. The licence fee will eventually become optional or replaced. The BBC will continue existing but as a smaller, less ambitious organization.

But I could be wrong. The BBC has survived previous predictions of doom. It's adaptable, well-run, and culturally valued in ways that are hard to quantify.

Estimated data suggests a balanced likelihood among the three scenarios, with 'Slow Decline' slightly more probable. This reflects potential challenges in adapting to digital trends and political pressures.

The Bigger Picture: What This Means for Public Broadcasting

The BBC's crisis isn't just about British TV. It's a harbinger for public broadcasting worldwide.

Every national broadcaster is facing the same pressure. Aging audiences, cord-cutting, streaming competition, and declining traditional TV revenue are global trends, not British ones.

The question isn't whether public broadcasting survives. It probably does, because societies value culture and journalism enough to fund them. The question is what form it takes.

Will it be mandatory licence fees? Probably not forever. The system is too vulnerable to technological change and generational behavior shifts.

Will it be voluntary subscriptions? Unlikely. Most people won't pay for public broadcasting if commercial alternatives exist, even if the public version is better quality.

Will it be general taxation? Maybe. Government funding is more sustainable politically than fees, even if it's less ideal economically.

Will it be hybrid models like the BBC's YouTube strategy? Probably. Most broadcasters will combine free distribution, advertising revenue, subscription tiers, and whatever government funding they can secure.

The BBC is essentially pioneering this hybrid model. Success or failure will influence how other countries' broadcasters adapt.

If the BBC succeeds, public broadcasting gets a template for sustainable digital transformation. If it fails, public broadcasters worldwide might face difficult choices about their future structure and funding.

That's a lot of weight on the YouTube strategy. But then again, the BBC has been carrying heavy weight for nearly a century. It's probably up for the challenge.

The Content Quality Question: Does Free Actually Work?

Here's an uncomfortable truth: free content isn't always better content.

The TV licence funds ambitious, sometimes uncommercial programming because there's money to spend without worrying about immediate return on investment. A £3 million documentary about obscure historical topics can get made because the licence fee covers it.

With YouTube, the incentive structure changes. Ambitious content that doesn't generate views doesn't justify its production cost. So creators gravitate toward content that performs well algorithmically.

This doesn't mean YouTube content is bad. YouTube has incredible creators making stunning work. But the incentive system is different, and that changes the mix of content that gets made.

The BBC has to manage this tension. It can't just optimize for YouTube's algorithm without abandoning its mission to create culturally valuable content that doesn't necessarily go viral.

One way to solve this is to have different content for different platforms. YouTube gets algorithm-friendly content designed to reach new audiences. iPlayer gets mission-driven content designed to serve licence fee payers. BBC broadcast channels get prestige drama and news designed for quality.

But fragmenting content like this risks diluting the BBC's brand and confusing audiences.

Alternatively, the BBC could use licence fee revenue to create genuinely excellent content that happens to perform well on YouTube. The two goals aren't necessarily in conflict. Quality content often does well algorithmically, especially if it's distinctive enough to stand out.

The question is whether the BBC can maintain that balance. History suggests that most organizations that try to serve multiple masters end up disappointing everyone. The BBC will have to be exceptionally well-run to make this work.

International Lessons: What We Can Learn from Others

Public broadcasters outside the UK have useful lessons for the BBC.

Canada's CBC tried to maintain mandatory funding while going digital. It's struggling. The fee is politically controversial, and young audiences don't see the value. The CBC's digital strategy hasn't fully compensated for declining traditional viewership.

Germany's ARD and ZDF went full-bore into digital without reducing licence fees. They maintain the most expensive public broadcasting system in Europe (Germans pay around €18 per month for public broadcasting). Audiences grudgingly accept it because the content is genuinely excellent and plentiful. But there's constant political pressure to reduce it.

France's TF1 partially privatized decades ago while maintaining some public funding. The result is a hybrid system where commercial and public interests compete directly. The competition is fierce, and the outcomes are mixed.

Australia's ABC launched free streaming (ABC iView) without eliminating government funding. It's probably the closest comparison to what the BBC is doing. The ABC seems to be succeeding because it's able to invest in streaming infrastructure with stable government funding. But Australian politics are also less hostile to public broadcasting than UK politics currently are.

America's PBS never had mandatory fees. It survives through government appropriations and donations. The result is lower budgets than BBC or ARD, but less political vulnerability around mandatory funding. PBS's challenge is that it can't match commercial services' production budgets, so it relies heavily on quality over quantity.

The lesson from these examples: there's no perfect solution. Every model involves trade-offs. The BBC's challenge is choosing trade-offs it can live with while maintaining cultural relevance and financial stability.

Final Assessment: Is the BBC's Strategy a Genius Move or Desperate Gamble?

Honestly, it's both.

The YouTube strategy shows genuine understanding of generational behavior and media consumption trends. The BBC's leadership clearly gets that traditional TV is dying among young people and that reaching Gen Z requires meeting them where they spend time.

It's also a desperate move because the BBC is facing existential pressure. Declining audiences, stagnant revenue, and political skepticism are forcing innovation. Without some major strategic shift, the BBC would slowly irrelevance.

From a business standpoint, free YouTube content is probably necessary for the BBC's survival. But whether it's sufficient is the real question.

The strategy gambles that free content will build audience loyalty and eventually convert to some form of revenue (iPlayer subscriptions, licence fee support, or YouTube advertising). If that conversion doesn't happen at sufficient scale, the strategy fails and the BBC faces deeper problems.

Given the risks, I'd rate the BBC's strategy as thoughtful but uncertain. It's probably the best option available, but success isn't guaranteed.

The BBC needs to execute perfectly on a three-part strategy: create genuinely excellent content, distribute it strategically across platforms, and convert some portion of new audiences to paying supporters. That's a lot to pull off simultaneously.

But if any organization can do it, it's the BBC. It has money, talent, infrastructure, and cultural brand value. Those are advantages that don't exist everywhere in the media landscape.

The next five years will tell us whether that's enough.

FAQ

What is the TV licence fee and why does the UK have it?

The TV licence is an annual fee (currently £175) that UK households must pay to watch live television on any channel. It was established in 1922 as a funding mechanism for the BBC and now funds all BBC services including television, radio, and iPlayer. The system exists because the UK decided that public broadcasting was worth funding universally so that quality content could be produced without relying solely on advertising revenue, which limits creative freedom and introduces commercial bias.

Why is the BBC launching free content on YouTube if people pay a licence fee?

The BBC is launching free YouTube content because Gen Z doesn't watch traditional TV or use iPlayer. YouTube is where young people already consume video content, so the BBC must distribute there to reach them. The free YouTube content serves as audience acquisition and brand building. The BBC hopes to eventually convert YouTube viewers into iPlayer subscribers or supporters of the licence fee system, but the primary goal is reaching audiences that wouldn't otherwise engage with BBC content at all.

Do I need a TV licence if I only watch BBC content on YouTube?

No, you do not need a TV licence to watch BBC content on YouTube. You only need a licence if you watch live television (on any channel) or watch live content on BBC iPlayer. On-demand content on YouTube and iPlayer doesn't require a licence. This is actually a growing source of controversy because it means people can access a significant amount of BBC content free of licensing requirements, which undermines the licence fee justification.

How much does BBC content cost on YouTube?

BBC content on YouTube is completely free to watch. YouTube makes money from advertising shown on the videos, and the BBC receives a portion of that advertising revenue (after YouTube takes its cut). Viewers don't pay anything directly to watch BBC content on YouTube, though they see advertisements unless they use an ad blocker or have a YouTube Premium subscription.

What's the difference between iPlayer and YouTube for watching BBC shows?

iPlayer is the BBC's official streaming app and website that requires a TV licence (or subscription for non-licence-fee payers in some cases). iPlayer typically has more content, no advertisements, offline download capability, and exclusive programming. YouTube has free BBC content with advertisements (unless you have YouTube Premium), but selection is limited and features are basic. iPlayer is designed as a premium experience, while YouTube is designed for discovery and audience building.

Will the TV licence fee increase?

The TV licence fee increases annually with inflation. It's been frozen at £175 for households with color TV since 2017, but it's expected to increase gradually. The BBC has applied for permission to increase the fee beyond inflation, but this is politically controversial. Future increases depend on government decisions and political negotiations. Some politicians argue the fee should decrease rather than increase, making the future quite uncertain.

Could the TV licence be replaced entirely?

Yes, it's possible. Various government administrations have proposed replacing the licence fee with general taxation, subscription-based funding, or a hybrid model. None of these proposals have succeeded so far, partly because there's no political consensus on an alternative and partly because the BBC's supporters defend the current system as effective. If the licence fee is ever replaced, it will likely be through a gradual transition rather than an overnight change.

Is YouTube actually sustainable for BBC's business model?

YouTube alone is not sustainable. YouTube advertising revenue is insufficient to replace licence fee revenue. However, YouTube is valuable as part of a hybrid model where the BBC uses license fees for content production and YouTube (plus iPlayer and other revenue sources) to distribute that content widely and generate supplementary revenue. The sustainability question is whether the BBC can convert enough YouTube viewers to iPlayer subscribers or licence fee supporters to maintain production budgets. That's still being tested.

Why can't the BBC just go subscription-only like Netflix?

The BBC could theoretically become subscription-only, but it would fundamentally change its mission and reach. A subscription model would generate revenue from paying subscribers but would exclude people who can't afford to pay, potentially widening access inequality. Public broadcasting's entire purpose is to serve everyone in society regardless of income. A subscription model would also likely reduce the BBC's audience and cultural relevance, especially if competing streaming services offered similar content. The BBC is trying to maintain universal access while still generating revenue, which is the core tension it's trying to solve.

What happens to BBC content that's released on YouTube?

BBC content released on YouTube typically stays there indefinitely unless specifically removed. The BBC has uploaded archives of classic shows, episodes from current series, and exclusive content to YouTube. Once content is uploaded, it's discoverable through YouTube's search and recommendation algorithms. This is different from iPlayer, where BBC often removes content after a certain period. YouTube uploads represent a permanent part of the BBC's digital presence and strategy.

Is the BBC's YouTube strategy working?

Early results suggest the strategy is reaching new audiences successfully. BBC YouTube content has accumulated billions of views. However, the critical measure is conversion: are YouTube viewers becoming paying iPlayer subscribers or supporters of the licence fee? That data isn't fully public, so it's hard to say definitively whether the strategy is "working" in the long-term business sense. The audience reach is clearly successful; the revenue and loyalty conversion is still unknown.

Conclusion: The BBC at a Crossroads

The BBC faces a challenge that no public broadcaster has fully solved: how to remain culturally relevant and financially sustainable in a world of free, ad-supported streaming content and declining traditional TV viewership.

The YouTube strategy is an honest attempt to address this challenge. It acknowledges that the BBC can't force Gen Z to watch BBC One at 9 PM or force them to pay £175 for a service they don't understand. Instead, the BBC is meeting audiences where they actually spend time and hoping that quality content will eventually generate loyalty.

It's a risky strategy. Success depends on uncertain factors: conversion rates from YouTube viewers to paying supporters, continued availability of adequate production funding, political willingness to maintain or modify the licence fee system, and the BBC's ability to maintain quality while optimizing for algorithmic distribution.

But the alternative is worse. Doing nothing means gradually losing younger audiences, declining revenue, shrinking production budgets, and eventual irrelevance. The BBC has to evolve or fade away.

The outcome will matter beyond the UK. If the BBC succeeds, public broadcasting institutions worldwide will have a model for digital transformation that preserves quality and mission while adapting to modern distribution. If it fails, public broadcasters everywhere might face difficult questions about their future viability.

What makes this moment particularly significant is that the BBC isn't just fighting streaming services and YouTube creators. It's fighting fundamental changes in how society consumes media and what they're willing to pay for. It's fighting generational preferences that might not be changeable through better content or better distribution.

The BBC has survived two world wars, hundreds of political controversies, and the rise of commercial television. It's an institution that adapts. The YouTube strategy shows that adaptability continues.

But even the BBC can't overcome market forces forever. If society decides that public broadcasting isn't worth funding, no strategy will save it. The BBC is essentially banking that people will eventually recognize the value of what it does and willingly support it, even if that support doesn't come through traditional mechanisms.

That's a bet worth making. Whether it pays off is something we'll know in five to ten years.

Key Takeaways

- BBC launched free YouTube content in February 2025 to reach Gen Z viewers who abandoned traditional TV, with viewership among under-25s dropping 60% in the last decade.

- The £175 annual TV licence fee becomes harder to justify when quality BBC content is available free on YouTube, creating tension between free audience growth and revenue preservation.

- YouTube advertising revenue cannot replace the £3.7 billion annual licence fee; the BBC would need 100-150 billion annual views to match current funding through ads alone.

- Demographic cliff threatens BBC revenue as older licence fee payers age out and younger generations who never watched traditional TV refuse to pay mandatory fees.

- Global public broadcasters face identical challenges with Canada, Germany, and Australia experimenting with hybrid models combining free digital distribution with stable funding sources.

Related Articles

- Watch The Traitors UK Season 4 Finale Free [2025]

- Why AI ROI Remains Elusive: The 80% Gap Between Investment and Results [2025]

- How Cloud Storage Transforms Sports Content Strategy: Wasabi & Liverpool FC [2025]

- YouTube TV Custom Multiview and Channel Packages: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- NBA League Pass Premium 2025: Complete Streaming Guide [2025]

- Rackspace Email Hosting Price Hike: A 706% Increase & What It Means [2025]

![BBC's YouTube Strategy and the TV Licence Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/bbc-s-youtube-strategy-and-the-tv-licence-crisis-2025/image-1-1769341196238.jpg)