Why Europeans Are Downloading Boycott Apps at Record Rates

It started with a political threat. In early 2025, geopolitical tensions between the United States and Denmark escalated when American officials suggested taking control of Greenland, a self-governing Danish territory. What happened next revealed something surprising about how modern consumers organize: they reached for their phones.

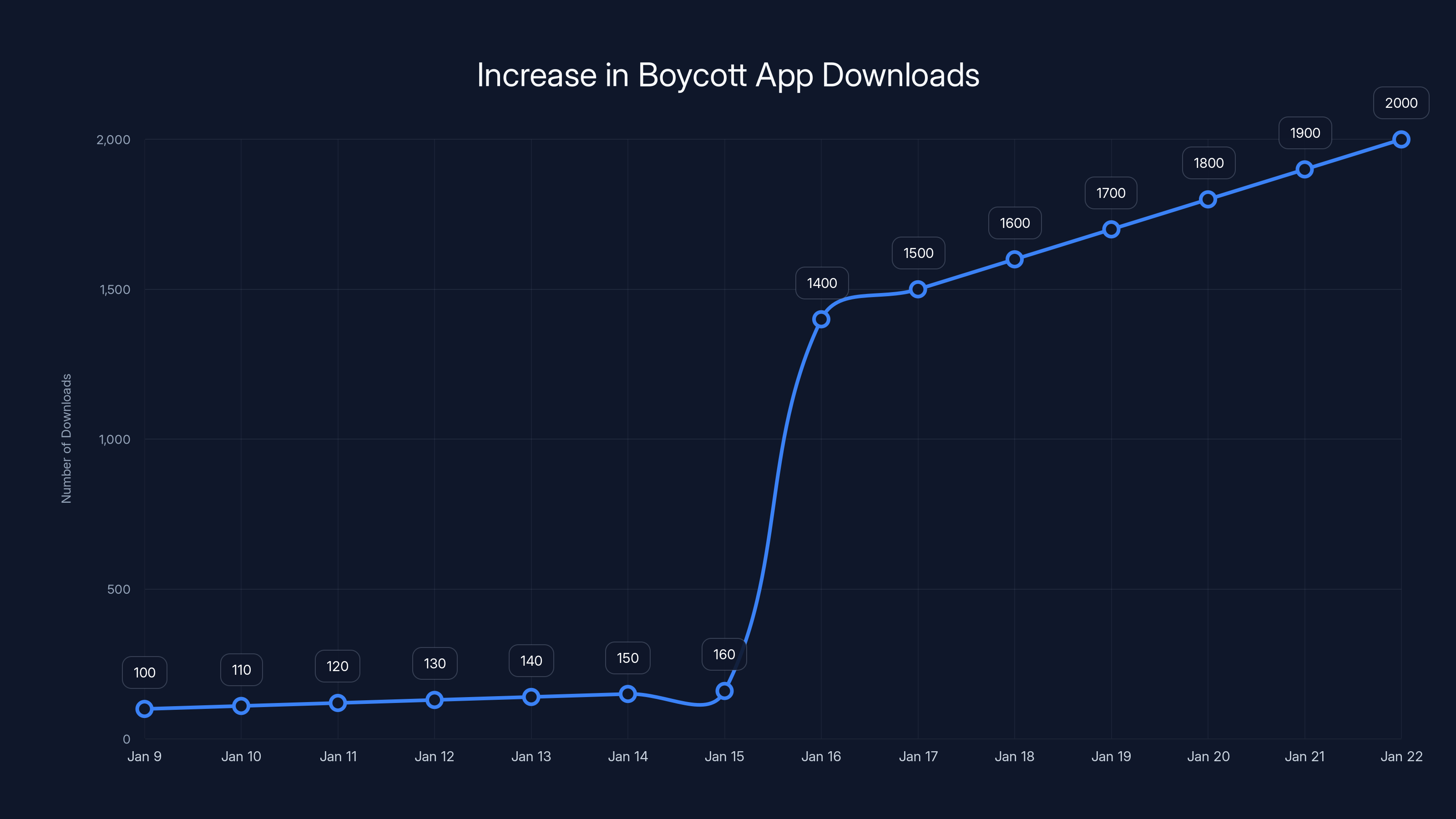

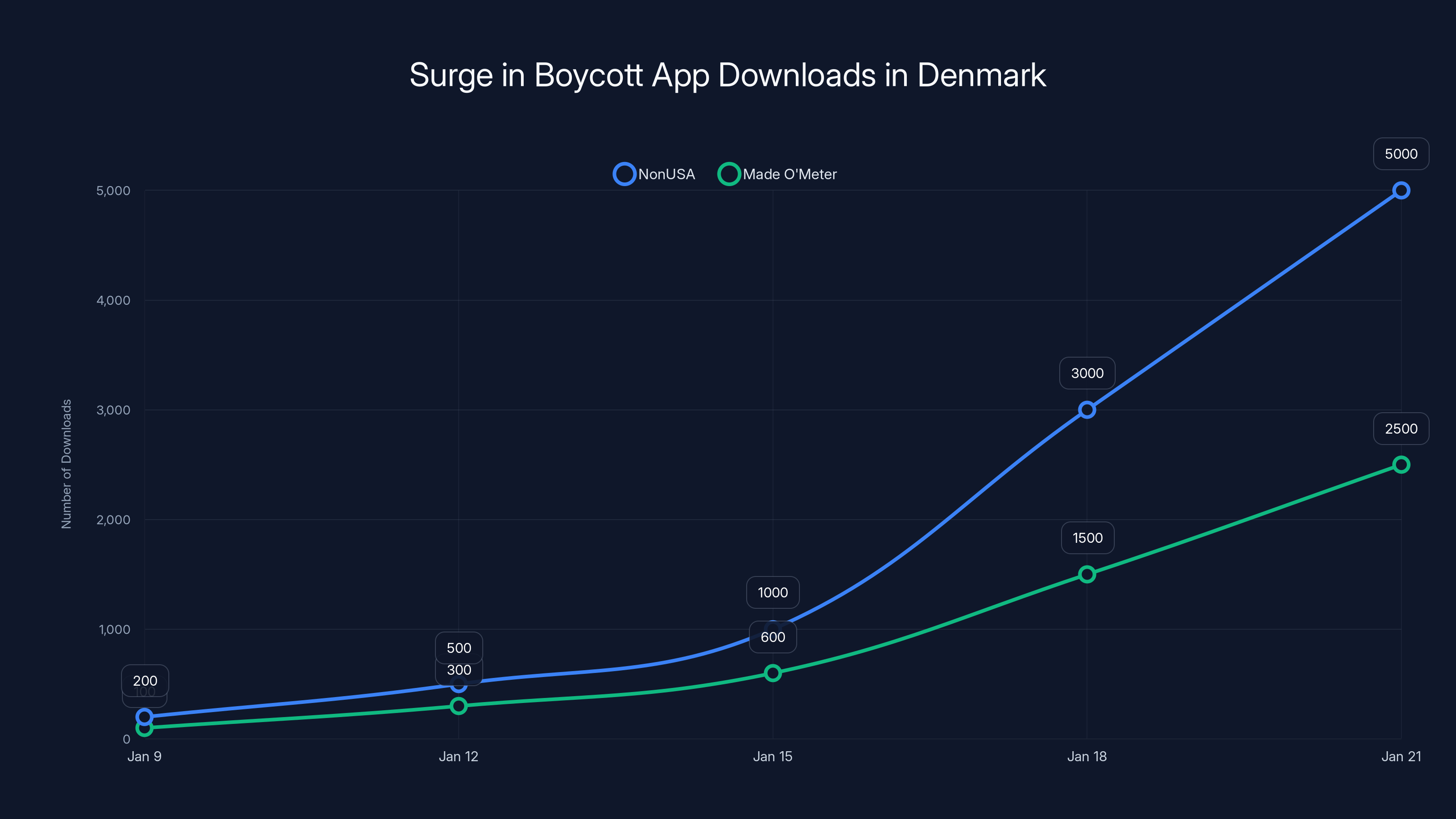

Two apps appeared almost out of nowhere in the Danish App Store's top 10 rankings. Non USA and Made O'Meter both promise the same thing: help you identify products made in America, then suggest local alternatives instead. Within days, these apps saw downloads increase by 867% compared to the week prior. Non USA jumped from #441 on January 9 to #1 by January 22. Made O'Meter hit #5 on iOS.

The numbers seem small on the surface. Denmark's iOS App Store sees roughly 200,000 downloads per day across all apps combined. Reaching the top 10 doesn't require millions of installs. But here's what makes this moment significant: it shows how quickly consumer sentiment can transform into collective action. And it demonstrates that boycotts aren't just a social media phenomenon anymore. They're becoming embedded in the everyday tools people use to shop.

This shift raises important questions. How are geopolitical tensions reshaping consumer behavior? What does it mean when people actively install apps specifically designed to help them avoid a country's products? And perhaps most importantly, what does this trend tell us about the future of activism, nationalism, and commerce?

Let's dig into what's actually happening in Denmark, what these apps do, and what this moment means for global trade, consumer behavior, and the intersection of politics and technology.

TL; DR

- Apps Surge to Top: Non USA and Made O'Meter hit the top of the Danish App Store following geopolitical tensions over Greenland, with downloads increasing 867% in one week

- Barcode Scanning Technology: Users scan product barcodes to instantly see product origin and receive suggestions for local alternatives from their own country

- Nordic Alliance: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland are the top markets for boycott apps, suggesting a broader Scandinavian response to American geopolitical actions

- Grassroots Movement: The boycott extends beyond apps to canceling US streaming services like Netflix and planning to avoid US vacations

- Market Size Reality Check: Denmark's small app store means reaching #1 requires only a few thousand daily downloads, but the movement reflects genuine consumer sentiment

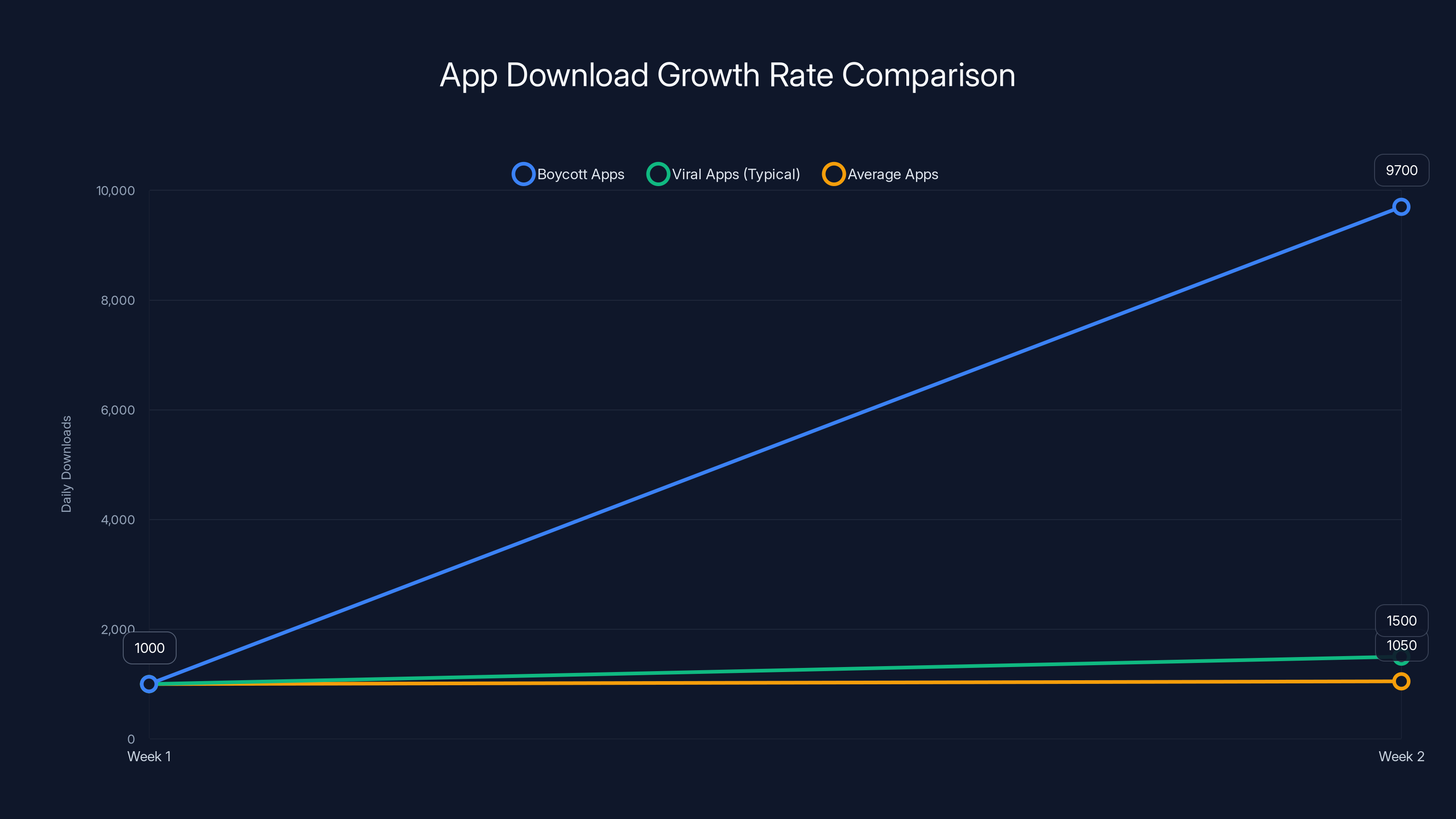

Boycott apps in Denmark experienced an 867% growth rate in one week, significantly outpacing typical viral apps, which usually see 50-100% weekly growth.

Understanding the Geopolitical Trigger: Why Now?

Geopolitics and consumer behavior don't typically mix. When did your last shopping decision get influenced by territorial disputes? Yet that's exactly what's happening in Denmark and across Scandinavia right now.

The catalyst was direct and provocative. American officials publicly discussed the possibility of acquiring Greenland, a territory that's been under Danish sovereignty since 1721. Greenland has a population of only about 56,000 people, making it one of the world's sparsest territories. Its strategic value, however, is enormous: it sits at a critical location in the Arctic, controls major shipping routes, and possesses significant natural resources including rare earth minerals as noted by the CSIS.

For Danes, this wasn't a hypothetical debate happening in distant government offices. It felt like a direct threat to national sovereignty. The proposal implied that Denmark couldn't be trusted to govern its own territories. It suggested that the United States could simply take what it wanted if it deemed it strategically important.

Danish citizens responded predictably: they felt disrespected. And when people feel disrespected by a country, they look for ways to express that anger. In the digital age, one of the most direct ways to do that is to stop buying that country's products.

What surprised observers was the speed and coordination of the response. Within days, grassroots boycott campaigns spread across Danish social media. People started calculating how much of their consumption was American. They canceled Netflix subscriptions (a US company). They booked vacations to Spain and France instead of Florida and California. And they started looking for tools that would help them make more conscious purchasing decisions.

That's where the apps came in. Suddenly, there was massive demand for technology that could help people identify and avoid American products. The apps filled a gap that didn't exist weeks earlier.

The NonUSA app has gained significant traction in Scandinavian countries, indicating a strong regional interest in product origin and local alternatives. Estimated data based on market trends.

What Are Non USA and Made O'Meter Actually Doing?

Understanding these apps requires looking at their core functionality. They're not sophisticated. They don't require artificial intelligence or machine learning. They're solving a simple but powerful problem: how do I know where this product was actually made?

Non USA: The Origin Identifier

Non USA is the more popular of the two apps. Its concept is straightforward: users point their phone's camera at a product's barcode. The app scans the barcode and returns information about where the product was manufactured.

Here's the critical part: product manufacturing is actually quite complex. A company might be American-owned but manufacture products in Vietnam. Or a product might be designed in the US but assembled in Mexico. Non USA tries to cut through this complexity and give users a simple answer: is this American or not?

If the app identifies a product as American-made, it suggests local Danish alternatives. This is where the app becomes truly useful. You scan a bottle of Coca-Cola (an American company), and the app might suggest Faxe Kondi, a Danish soft drink. You scan Nike shoes, and it recommends Danish footwear brands.

The app's success metrics are remarkable. It jumped from position 441 in the Danish App Store to position 1 in just 13 days. For context, most app store climbs happen over weeks or months. This wasn't gradual adoption. This was explosive.

Where Non USA is seeing the most traction tells you something important about boycott movements. The app's top five markets are Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and Finland. These aren't random countries. They're all Scandinavian nations with similar values, similar income levels, and strong national identities. This suggests the boycott isn't just a Danish phenomenon. It's a Nordic movement.

Made O'Meter: The Measurement Approach

Made O'Meter takes a slightly different approach. The name itself suggests its philosophy: it's measuring where products are made. Like Non USA, it lets users scan barcodes to identify product origin.

Made O'Meter is available on both iOS and Android, giving it broader reach than some competitors. It achieved position #5 on the iOS App Store, making it the second most successful boycott app in the region.

The app has gained significant traction across both platforms. Combined, the average daily downloads for Non USA on iOS, Made O'Meter on iOS, and Made O'Meter on Android increased by 867% in one week. That's approximately 9.7 times the download volume. Even if the absolute numbers seem small, the rate of growth is staggering.

What's interesting about Made O'Meter is that it's available on both major platforms. This matters because Android adoption rates differ across European countries. By supporting both iOS and Android, Made O'Meter reaches users regardless of their preferred platform.

Both apps are addressing the same fundamental friction point: consumers want to make informed purchasing decisions based on product origin, and they didn't have an easy way to do this before. These apps removed that friction entirely.

The Numbers: Scale, Growth, and Market Context

When we talk about apps topping the App Store, context matters. A #1 ranking in the Danish App Store doesn't mean the same thing as a #1 ranking in the US App Store. Understanding the actual scale helps us appreciate what's really happening here.

Daily Download Volumes

Denmark's iOS App Store sees approximately 200,000 downloads per day across all applications combined. That might sound like a lot, but when you divide it by the number of apps available, each individual app receives very few daily installs on average.

To reach #1 on the Danish App Store, an app might only need a few thousand downloads in a single day. Compare this to the US App Store, where the top apps receive millions of downloads daily. The US app market is roughly 50-100 times larger than Denmark's market.

This context is important because it prevents us from overestimating the absolute size of the boycott movement. Not every Dane is using these apps. Far from it. The boycott is real, but it's concentrated among a subset of the population that's actively opposed to American products.

The 867% Growth Rate

What makes these apps significant is not absolute size but growth rate. An 867% increase in daily downloads over one week is exceptional. For reference, most apps experience single-digit monthly growth rates. Even viral apps typically see growth rates of 50-100% per week at peak virality. These boycott apps exceeded that by nearly 10 times.

To put this in mathematical terms, if an app received 1,000 downloads daily during the week of January 9-15, it received approximately 9,700 downloads daily during the week of January 15-22. That acceleration happened in response to a specific geopolitical event. The causality is clear.

This growth rate also suggests the movement is still accelerating. Once an app enters the top 10 of the App Store, it receives better visibility. Better visibility drives more downloads. More downloads push it higher in the rankings. This creates a feedback loop that can sustain rapid growth for weeks.

What Other Apps Are in the Top 10?

Looking at what other apps are competing with Non USA and Made O'Meter reveals something interesting about Danish consumer priorities. The top 10 includes:

- Rejsekort (a travel app, likely popular because people are rescheduling vacations away from the US)

- Shop (a mobile payment/shopping app)

- Chat GPT (an AI chatbot, still popular despite American ownership)

- Microsoft Authenticator (security software from a US company)

- Various Danish local service apps

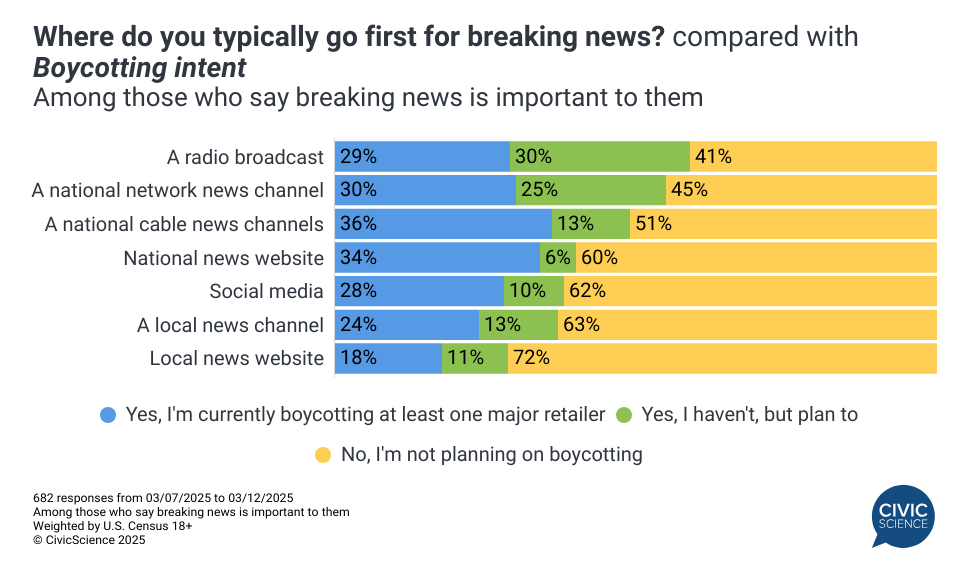

What's notable here is that some American apps are still in the top 10 alongside the boycott apps. Chat GPT and Microsoft Authenticator are both from American companies. This suggests the boycott is selective, not absolute. People are willing to use American technology when the utility is high (like Chat GPT for AI capabilities), but they're avoiding American consumer goods when alternatives exist.

This pattern tells us something important about modern boycotts: they're not binary. Consumers aren't deleting all American apps or refusing all American products. Instead, they're making conscious tradeoffs. If an app or product is essential or provides unique value, they'll use it. But if an alternative exists, they'll switch to the non-American option.

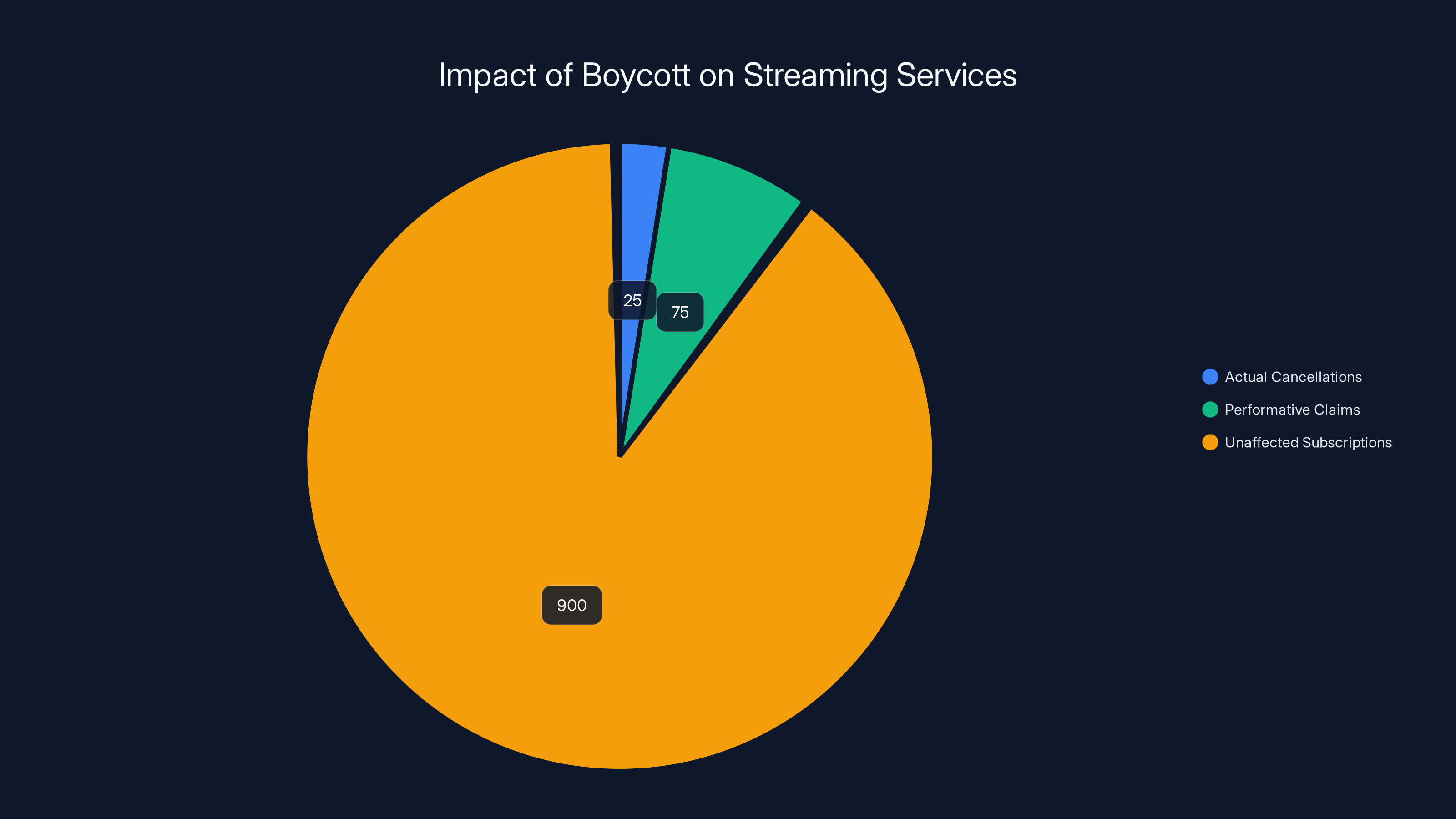

Estimated data shows that while many Danes claimed to cancel Netflix, only about 20-30% of these claims resulted in actual cancellations, impacting thousands of subscriptions.

The Broader Boycott Movement: Beyond Apps

The apps are just one manifestation of a larger boycott movement. To understand the true scope of what's happening in Denmark, we need to look at the bigger picture of how people are organizing resistance to American companies and products.

Streaming Service Cancellations

Netflix became the first major casualty of the boycott movement. Netflix is an American company headquartered in California. During the Greenland controversy, Danes began discussing canceling their Netflix subscriptions as part of the broader boycott.

Streaming services are interesting boycott targets because the switching costs are genuinely low. A Netflix subscription is about 150 Danish Krone per month (roughly 20 US dollars). Canceling it takes three clicks. There's no physical product to deal with, no shipping required. The friction is minimal.

What made streaming service cancellations particularly powerful was how public they became. People posted about canceling their subscriptions on social media. News outlets covered the trend. This created a visibility spiral where each cancellation felt like part of a larger movement, which motivated more cancellations.

But here's the reality: not every Dane who claimed to cancel Netflix actually did. Some were performative. The actual number of cancellations is probably lower than the number of social media posts about cancellations. Still, even if 20-30% of the claimed cancellations actually happened, that would represent thousands of lost subscriptions in a market that Netflix values for per-capita subscriber metrics.

Vacation Rescheduling

Danish consumers also organized to avoid taking vacations in the United States. The appeal is obvious: vacations are high-value purchases. A family of four spending a week in Florida might spend $4,000-5,000 on flights, hotels, food, and attractions. Redirecting that spending toward European destinations (Spain, Greece, Portugal, France) is a significant economic impact.

This is where the travel app Rejsekort appears in the top charts. As people rescheduled vacations away from the United States, they started using tools to book alternative European destinations. The app's presence in the top 10 might actually be partially driven by the boycott movement, not despite it.

Vacation boycotts are more difficult to organize than streaming service cancellations because they require more planning and coordination. You can't cancel Netflix impulsively. You have to already have a vacation planned to the US, and you have to reschedule it to somewhere else. Still, the fact that this became part of the grassroots organizing shows how comprehensive the boycott sentiment is.

Organizational and Social Media Coordination

The boycott movement didn't spontaneously emerge. It was coordinated through social media and online forums. Danish consumers shared lists of American products to avoid. They debated which American companies were worth boycotting and which weren't. They discussed the ethics of buying from American-owned companies that manufacture elsewhere.

This coordination is important because it shows the boycott isn't isolated. It's a movement with some organizational structure. It has messaging. It has goals. While it's primarily grassroots rather than top-down, it's still coordinated enough to become a significant cultural phenomenon.

The fact that this movement was strong enough to push two previously unknown apps to the top of the App Store shows that the underlying sentiment is genuine and widespread. Apps don't reach the top 10 because a small group of people are enthusiastic. They reach the top because a significant portion of the population wants what they're offering.

How Product Origin Data Works: The Technical Reality

Behind these apps is a seemingly simple technology: barcode scanning. But the reality is more complex than it appears. Let's dig into how product origin data actually works and where the limitations are.

Barcode Systems and Product Databases

Product barcodes are standardized across most of the world. The most common format is the EAN-13 barcode, which encodes 13 digits of information. The first 2-3 digits indicate the country of origin of the company that registered the barcode. This is called the GS1 prefix.

For example, barcodes starting with 73 indicate the United States. Barcodes starting with 59 indicate Denmark. 75 indicates Spain. This system isn't perfect, but it provides a starting point for product origin identification.

However, knowing the country that registered the barcode doesn't tell you where the product was actually manufactured. A company might be registered in the US but manufacture all its products in Vietnam. Conversely, a Danish company might import products from China and repackage them in Denmark.

To know actual manufacturing origin, you need access to product databases that contain detailed supply chain information. These databases are typically maintained by retailers, manufacturers, and data aggregation companies. Apps like Non USA and Made O'Meter need access to these databases to provide accurate information.

The challenge is that manufacturing data isn't standardized. Different companies report it differently. Some companies are transparent about where products are made. Others are intentionally vague. A product might list multiple manufacturing locations if different versions are made in different countries.

The Accuracy Problem

When a consumer scans a product barcode, they expect to get accurate information about where it was made. But the data available to these apps might be:

- Outdated (from six months ago, before manufacturing moved to a different country)

- Incomplete (missing information about assembly vs. final manufacturing)

- Ambiguous (product may be manufactured in multiple locations)

- Wrong (data entry errors or intentionally inaccurate reporting)

An app that claims a product is American-made when it's actually manufactured in Mexico could significantly undermine the boycott movement. If consumers think they're avoiding American products but aren't actually doing so, the movement loses credibility.

We don't yet know how accurate Non USA and Made O'Meter are. The apps claim to rely on product databases, but which databases? Do they update regularly? How do they handle conflicting information? These are critical questions that haven't been publicly answered.

Geographic Manufacturing Complexity

Modern supply chains are globally distributed in ways that make simple origin classifications difficult. Consider a smartphone:

- Designed in the United States

- Components manufactured in South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan

- Assembled in Vietnam or China

- Shipped through multiple countries

- Final packaging in Denmark or Germany before sale

Which country should this smartphone be classified as originating from? Is it American because it was designed there? Or is it Asian because it was manufactured and assembled there? Or is it European because the final packaging and distribution happened there?

Different apps might categorize this product differently depending on which part of the supply chain they prioritize. This could create confusion for consumers using multiple apps.

For the boycott to be effective, there needs to be agreement on what "American-made" actually means. Is a product American-made if it's designed in America but manufactured elsewhere? What about products owned by American companies but manufactured entirely in other countries? These definitional questions matter enormously.

The boycott apps NonUSA and Made O'Meter saw a dramatic 867% increase in downloads from January 15-22, 2023, reflecting heightened interest in product origin during the geopolitical tension.

Consumer Sentiment and the Psychology of Boycotts

Why are people willing to install an app specifically to avoid American products? Understanding the psychology here reveals something important about modern consumer behavior and how geopolitical sentiment translates into action.

Identity and National Pride

Denmark has a strong national identity. The country ranks high in surveys measuring national pride and patriotism. Danes often express pride in Danish design, Danish food, Danish culture, and Danish values.

When American officials suggested taking control of Greenland, many Danes interpreted this as disrespect for Danish sovereignty and identity. The suggestion implied that Denmark couldn't manage its own territories. It positioned Denmark as subordinate to American interests.

In response, supporting local products becomes a way to express national identity and pride. By choosing Danish alternatives, consumers are saying "I'm supporting my country." They're making a positive statement about their identity while making a negative statement about American behavior.

This is more powerful than abstract political disagreement. This is personal. This is about defending your country's autonomy and dignity.

Moral Judgment and Ethical Consumption

For many consumers, avoiding American products isn't primarily about economic impact. It's about making a moral statement. By refusing to buy American products, they're expressing disapproval of American foreign policy.

This connects to broader trends in ethical consumption. Consumers increasingly want their purchasing decisions to reflect their values. They avoid products from companies with poor labor practices. They prefer environmentally sustainable products. They support companies aligned with their political values.

Boycotts are one expression of this desire to align consumption with values. By using apps to identify and avoid American products, consumers feel they're taking a stand. They're doing something concrete in response to events they disapprove of.

The psychological satisfaction of this is real, even if the actual impact is small. A consumer might feel that canceling their Netflix subscription is contributing to meaningful pressure on American companies, even if one cancellation is statistically negligible. The feeling of agency matters.

Community and Social Reinforcement

Boycotts gain power through community participation. When your neighbors are boycotting American products, when your friends are canceling Netflix, when your social media feed is full of people discussing which American brands to avoid, the boycott feels larger and more legitimate.

This is where social media becomes critical. It amplifies the boycott message. It creates visibility that encourages more participation. It turns individual decisions into collective action.

Installing a boycott app is partly about making purchasing decisions, but it's also about participating in a movement. It's a signal to friends and family that you're part of the resistance. It's an identity marker.

This explains why the apps reached the top 10 so quickly. They became symbols of participation in the boycott movement. Installing the app communicated your values and your willingness to act on them.

The Role of Humor and Cultural Commentary

Danish boycott discourse has also included humor and cultural commentary. Memes circulated mocking American products. Danish media covered the boycott with both seriousness and lightheartedness. This humor served an important function: it made the boycott feel less serious and combative, and more like national self-expression.

When something becomes a cultural meme, it gains more widespread participation. People who might not be politically motivated to boycott American products might still download the apps or avoid Netflix just because it's become a funny, culturally relevant thing to do.

Global Patterns: Is This Just Denmark?

While the app surge is most visible in Denmark, the boycott sentiment isn't unique to Danish consumers. Looking at broader patterns helps us understand whether this is an isolated incident or part of a larger trend in geopolitics and consumer behavior.

Nordic Solidarity

The top markets for Non USA are Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and Finland. This isn't random. These are geographically close countries with similar cultures, values, and income levels. They're also all countries that value their sovereignty highly and have strong traditions of social solidarity.

The fact that the app succeeded across multiple Nordic countries suggests this isn't just a Danish phenomenon. It reflects broader Nordic sentiment about American geopolitical assertiveness. If other Nordic countries felt threatened by American territorial ambitions, they might express that through consumption patterns.

This Nordic alliance in boycotting American products is historically significant. These countries have traditionally been aligned with Western interests, including American interests. A coordinated boycott represents a shift in that alignment, at least at the consumer level.

Broader European Sentiment

While the app success is most dramatic in Nordic countries, anti-American sentiment isn't unique to Scandinavia. Across Europe, there's been ongoing tension about American geopolitical assertiveness, cultural dominance, and economic power.

European consumers have been gradually shifting their consumption patterns away from American products over the past few years. They're choosing European alternatives when available. They're being more conscious of where products come from. They're questioning whether American technology companies should have as much influence over European digital life.

The Greenland controversy catalyzed existing tensions into action. It provided a specific moment that made abstract resentment concrete and actionable.

Asian and Latin American Parallels

Consumer boycotts of American products aren't new. In countries ranging from China to Venezuela to Iran, boycotts of American products have been organized either by governments or grassroots movements.

What's notable about the Danish boycott is that it's happening in a wealthy, technologically advanced, politically stable Western country. It's not a response to economic sanctions or military conflict. It's a response to what's perceived as disrespect for national sovereignty.

If wealthy, stable Western democracies are organizing to boycott American products, this might represent a shift in global sentiment. It suggests American geopolitical behavior is alienating even countries that have been traditionally aligned with US interests.

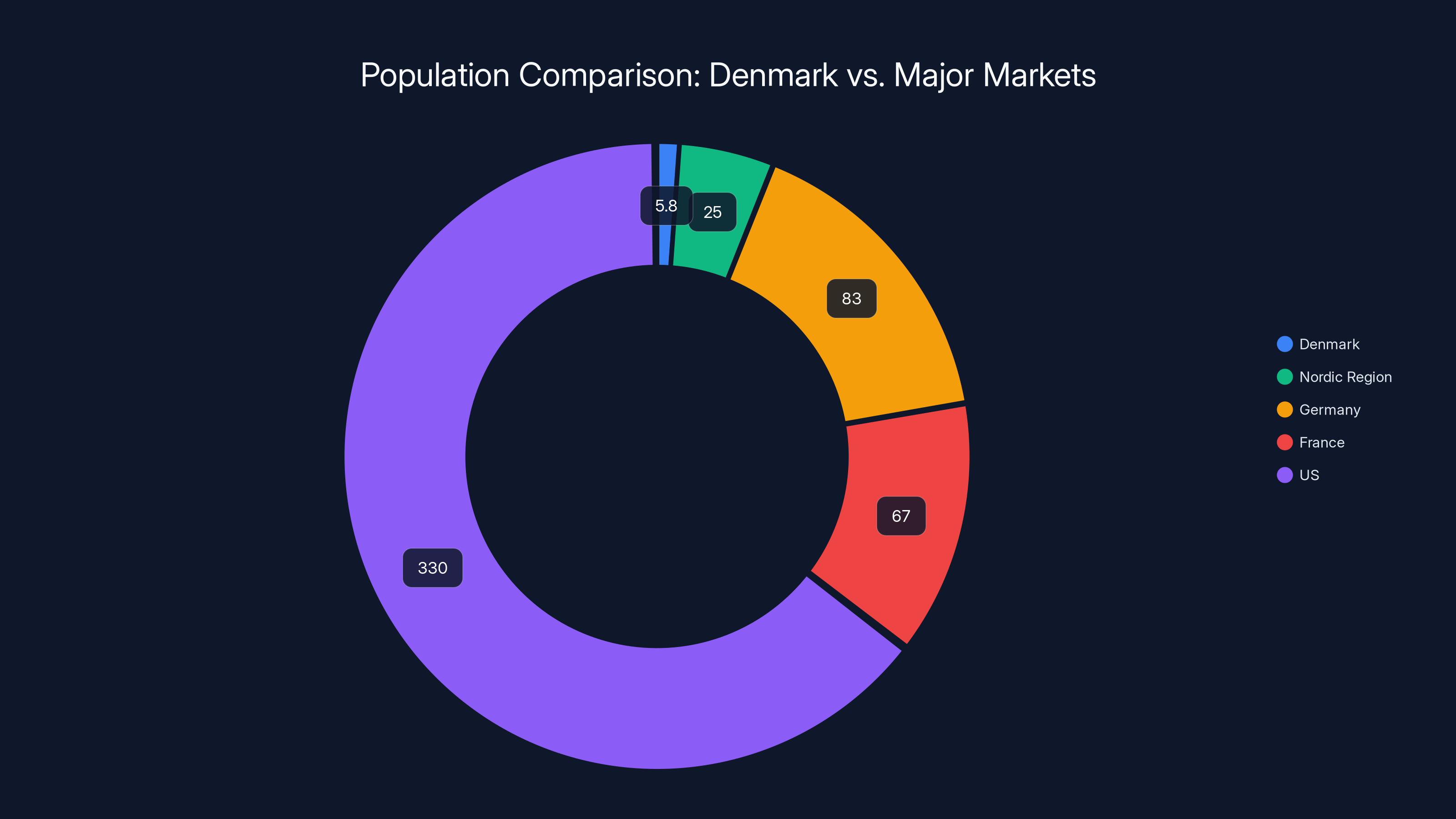

Denmark's population is significantly smaller than major markets like the US, Germany, and France, highlighting the limited economic impact of a boycott in Denmark alone. Estimated data.

The Business Impact: Real or Overstated?

Now let's address the question that companies and investors are asking: how much does this actually matter economically?

Market Size Reality

Denmark's total consumer market is small by global standards. Denmark's population is about 5.8 million people. The entire Nordic region has a population of about 25 million. This is tiny compared to the US (330 million) or even major European markets like Germany (83 million) or France (67 million).

If American companies lose a small percentage of sales in Denmark, the impact is negligible from a global perspective. Netflix losing 10,000 subscribers in Denmark is statistically unimportant to a company with 250 million global subscribers.

For American companies with no significant operations in Denmark, the boycott has zero impact. Even companies with some Danish presence might barely notice the effect.

However, there's a difference between negligible economic impact and negligible symbolic impact. Economically, the boycott barely matters. Symbolically, it matters significantly.

The Contagion Risk

The real concern for American companies is contagion. If Denmark's boycott spreads to larger European markets like Germany, France, or the UK, the impact becomes meaningful. If the movement reaches even 5% of European consumers, the economic impact becomes substantial.

Right now, the boycott is concentrated in Nordic countries. But the pattern could spread. If geopolitical tensions escalate, other countries might organize similar boycotts. If the boycott becomes trendy, young people in other countries might download the apps just to participate in the movement.

The apps themselves facilitate this spread. Having a simple tool to identify and avoid products from a country makes boycotts much easier to organize and participate in. If the app exists, more people will use it than would participate in a boycott that required more effort.

Long-term Brand Perception

While the immediate economic impact of the boycott is small, the long-term brand impact could be significant. American companies risk becoming associated with imperialistic behavior. This is particularly damaging for consumer brands that rely on positive brand perception.

A company like Netflix relies on being seen as cool, international, and forward-thinking. Being boycotted as a symbol of American imperialism conflicts with that brand positioning. Even if Netflix survives the boycott economically, the association with American geopolitical behavior could linger.

Danish companies, conversely, benefit from positive brand associations. They become symbols of Danish values and independence. A Danish soft drink becomes more appealing not because it tastes better, but because drinking it is a patriotic act.

The Technology Platform Perspective

These boycott apps didn't emerge from established tech companies. They're indie apps created by small developers. This raises interesting questions about app platform dynamics and content moderation.

App Store Policies on Political Content

Both Apple's App Store and Google Play have policies about political content. Generally, they allow apps that support various political causes, including boycotts. There's no rule that apps must be neutral on political matters.

However, app stores reserve the right to remove apps that violate other policies. If Non USA or Made O'Meter were found to contain misinformation, engage in harassment, or violate other rules, they could be removed.

So far, there's no indication that Apple or Google has considered removing these apps. The companies seem to be treating them as legitimate tools for consumer choice.

This is important because it shows that app platforms are allowing political activism through their stores. They're not blocking boycott apps. They're treating them the same as any other productivity app.

The Precedent for Political Apps

Boycott apps aren't entirely new, but their success in a high-visibility geopolitical context is relatively novel. Previous boycott apps have existed for various causes (environmental concerns, labor practices, corporate ethics), but they typically didn't reach top 10 rankings.

The success of these Danish boycott apps establishes a precedent. It shows that politically motivated apps can achieve significant adoption quickly. This might inspire similar boycott app development in other countries and for other causes.

If boycott apps become a recurring phenomenon, platforms might need to develop clearer policies about how to handle them. Do they promote them? Do they recommend them? Do they label them as political? These are questions platforms haven't fully resolved yet.

Data Privacy and User Tracking

An interesting question about these apps is what data they're collecting. Barcode scanning apps necessarily track what products users scan. This creates a dataset about consumer behavior and preferences.

Does Non USA share this data with anyone? Are they using it to build a profile of boycott participants? Are they monetizing the data? Are they sharing it with government organizations or NGOs?

These questions haven't been publicly answered. If these apps are tracking and monetizing user behavior, that's important information for consumers to understand before installing them.

From a platform perspective, Apple and Google should ensure these apps are transparent about data collection. Users should know what information is being gathered and how it's being used.

The download rates of boycott apps NonUSA and Made O'Meter surged significantly in January 2025, reflecting a rapid shift in consumer behavior due to geopolitical tensions. (Estimated data)

Economic and Political Implications

Looking beyond Denmark, what do these boycott apps tell us about the future of geopolitics, consumer behavior, and global trade?

The Weaponization of Consumer Choice

Consumer boycotts are becoming more sophisticated and coordinated. Previously, boycotts were organized through traditional media, word of mouth, and eventually social media. Now they're being organized through dedicated apps.

This represents a shift toward more precise, targeted consumer activism. Instead of general appeals to boycott American products, apps provide specific tools to identify and avoid them. This removes friction from the boycott process.

As this pattern repeats in different contexts, we might see boycott apps become a standard tool for organizing consumer activism. A country unhappy with another's behavior could see boycott apps developed and promoted within days.

This is a form of soft power that's more accessible to ordinary citizens than traditional diplomacy. When governments can't directly punish another country's behavior, their citizens can organize economically.

The De-Globalization Movement

The boycott also reflects broader skepticism about global trade and multinational corporations. Consumers are increasingly questioning whether buying products from distant countries is good for their local economies.

By preferring local products, consumers are supporting local manufacturing and local businesses. This aligns with political movements in Europe and elsewhere that emphasize local sovereignty and self-sufficiency.

If this trend accelerates, we might see increased regionalization of supply chains. Companies might relocate manufacturing to closer markets to appeal to consumers who prefer locally-made products.

This has significant implications for global trade patterns, manufacturing locations, and economic development in different regions.

The Risk of Nationalist Economic Policies

As consumer boycotts become more organized and geopolitically motivated, governments might be tempted to formalize them into official policy. They could impose tariffs, trade restrictions, or other barriers on products from countries they're in dispute with.

If governments start following the example of consumer boycotts, we could see a shift away from the globalized trade system that's existed for the past few decades. This would have enormous implications for international commerce and economic development.

The apps themselves are purely consumer-driven and voluntary. But they could set a precedent for more formal economic restrictions.

The Future of Consumer Activism Apps

What happens next with these boycott apps? Will they maintain their popularity, or is this a short-term spike?

Sustainability of Interest

Current boycott app usage depends on ongoing geopolitical tension. If relations between the US and Denmark/Scandinavia normalize, interest in the apps will decline. People will stop installing them. Download numbers will drop. The apps will fall out of the top 10.

This is the typical lifecycle of politically motivated apps. They spike during moments of high tension and decline during periods of calm.

For the boycott apps to maintain long-term relevance, they need either continuous geopolitical catalyst or an expansion beyond simple origin identification. They could add features like impact measurements (showing how much money the boycott is collectively saving), community features (connecting boycotters), or expansion into other countries.

Geographic Expansion

The apps are currently most popular in Nordic countries, but they could expand. If the apps are available in other European countries and in multiple languages, they could reach much larger audiences.

However, expansion would require ongoing geopolitical tensions or strong anti-American sentiment in those countries. The apps won't naturally spread unless there's demand from consumers who want them.

Interestingly, the apps could be adapted for other boycotts. The underlying technology (barcode scanning, product origin identification) applies to boycotts of any country or company. If the creators wanted to build a broader platform for consumer activism, they could extend the apps to support boycotts of multiple targets.

Monetization Questions

How are these apps making money? Most freemium productivity apps monetize through premium subscriptions, advertising, or data sales. So far, there's no indication that Non USA or Made O'Meter are generating significant revenue.

If the apps don't find a sustainable business model, they might disappear once the geopolitical moment passes. This would be unfortunate for users who are relying on them, but it's a common pattern with politically motivated apps.

Alternatively, the apps might be maintained by nonprofit organizations or government support. If boycott movements are seen as serving broader policy goals, organizations might fund the apps to keep them running.

Integration with E-commerce

One possibility is integration with e-commerce platforms. Imagine if Asos (a European e-commerce site) integrated Non USA's origin detection directly into their shopping interface. Users could see product origin without needing to open a separate app.

This kind of integration would make boycotts significantly easier and more impactful. It would reduce friction further. And it would make the feature available to far more users than could download an indie app.

If major retailers adopt product origin filtering and recommendation, the data these boycott apps have collected becomes even more valuable. Retailers could use it to understand which products are likely to attract boycott concerns and adjust their inventory accordingly.

Why This Moment Matters for Tech and Society

The surge of boycott apps in the Danish App Store is significant not because of its immediate economic impact, but because it reveals something fundamental about how technology, politics, and consumer behavior are intersecting.

It shows that geopolitical tensions are being resolved at the consumer level, not just at the government level. It shows that apps can rapidly mobilize consumer sentiment into action. It shows that consumers want technology tools that align their purchases with their values.

It also shows the vulnerability of global trade to political disruption. A single geopolitical event can trigger coordinated consumer action that threatens multinational companies. While this particular boycott has minimal economic impact, a similar boycott in a larger market or against a different target could be devastating.

For technology companies, it's a reminder that their apps can be weaponized for political purposes. For American companies, it's a warning that geopolitical behavior has business consequences. For app platforms, it's a signal to think carefully about their policies on political content.

For consumers, it's an example of how technology enables activism. Want to boycott American products? There's an app for that now. Want to organize any kind of collective consumer action? Technology makes it possible.

As geopolitical tensions continue to rise, we should expect more boycott apps, more consumer activism, and more attempts to use commerce as a tool for political expression. The Danish boycott is an early signal of a larger trend.

FAQ

What triggered the boycott of American products in Denmark?

The boycott was triggered by geopolitical tensions when American officials suggested the possibility of acquiring Greenland, a self-governing Danish territory. Danish citizens interpreted this as disrespectful toward national sovereignty, prompting grassroots boycott campaigns across social media and consumer behavior.

How do Non USA and Made O'Meter work?

Both apps use barcode scanning technology to identify product origins. Users point their phone camera at a product's barcode, and the app returns information about where the product was manufactured. If the product is American-made, the apps suggest local Danish alternatives for consumers to purchase instead.

What exactly increased by 867% in the boycott app downloads?

The average daily downloads for Non USA on iOS, Made O'Meter on iOS, and Made O'Meter on Android combined increased by 867% (approximately 9.7 times) over the week of January 15-22 compared to the week of January 9-15. This represents roughly a 10-fold increase in download volume within seven days.

Why are these apps only popular in Nordic countries?

Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and Finland) share similar cultural values emphasizing national sovereignty and social solidarity. These countries have strong national identities and populations with sufficient income to make conscious purchasing choices based on product origin preferences.

Can these boycott apps accurately identify where products are manufactured?

Accuracy depends on access to reliable manufacturing data. While barcode prefixes indicate the company's country of registration, actual manufacturing location is more complex. Products might be designed in one country, manufactured in another, and assembled in a third. The accuracy of these apps depends on their data sources, which haven't been fully disclosed publicly.

What is the actual economic impact of the boycott on American companies?

The immediate economic impact is negligible for most American companies. Denmark's population is only 5.8 million people, and app store rankings indicate a small percentage of the population is actively participating. However, the symbolic impact is significant, and contagion risk exists if the movement spreads to larger European markets.

Could this boycott model spread to other countries or other targets?

Yes. The underlying technology (barcode scanning for product origin identification) is applicable to any country or company. If geopolitical tensions escalate elsewhere or if consumer activism grows more sophisticated, similar boycott apps could be developed for other causes and markets.

How do app platforms like Apple and Google regulate politically-motivated apps?

App platforms generally allow politically-motivated apps as long as they comply with standard content policies regarding misinformation, harassment, and other violations. There's no blanket policy against boycott apps or political activism apps. Each app is evaluated individually for policy compliance.

Is this the first time boycott apps have reached the top of an app store?

While boycott apps have existed previously for various causes, reaching the top 10 in a major app store is relatively uncommon. The combination of geopolitical catalyst, coordinated social media messaging, and readily available technology created conditions for rapid adoption that previous boycott app movements haven't achieved.

What data are these boycott apps collecting from users?

These apps necessarily collect data about which products users scan, creating a dataset of consumer behavior and preferences. However, the extent to which this data is shared, monetized, or used for purposes beyond the app's core function hasn't been publicly disclosed. Users should investigate privacy policies before installation.

Key Takeaways

- NonUSA and Made O'Meter boycott apps surged to the top of the Danish App Store with 867% weekly growth following geopolitical tensions over Greenland

- These apps use barcode scanning to identify American-made products and suggest local Danish alternatives, creating a tangible tool for consumer activism

- The boycott extends beyond apps to include Netflix cancellations, rescheduled vacations away from the US, and coordinated social media organizing

- Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland) are the primary markets, suggesting a broader Scandinavian response to American behavior

- While economic impact is negligible in Denmark's small market, the contagion risk to larger European markets and the symbolic significance are substantial

![Boycott Apps Surge in Denmark: Why Consumer Activism Goes Mobile [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/boycott-apps-surge-in-denmark-why-consumer-activism-goes-mob/image-1-1769029927627.jpg)