How Trump's Tariffs Are Creeping Into Amazon Prices [2025]

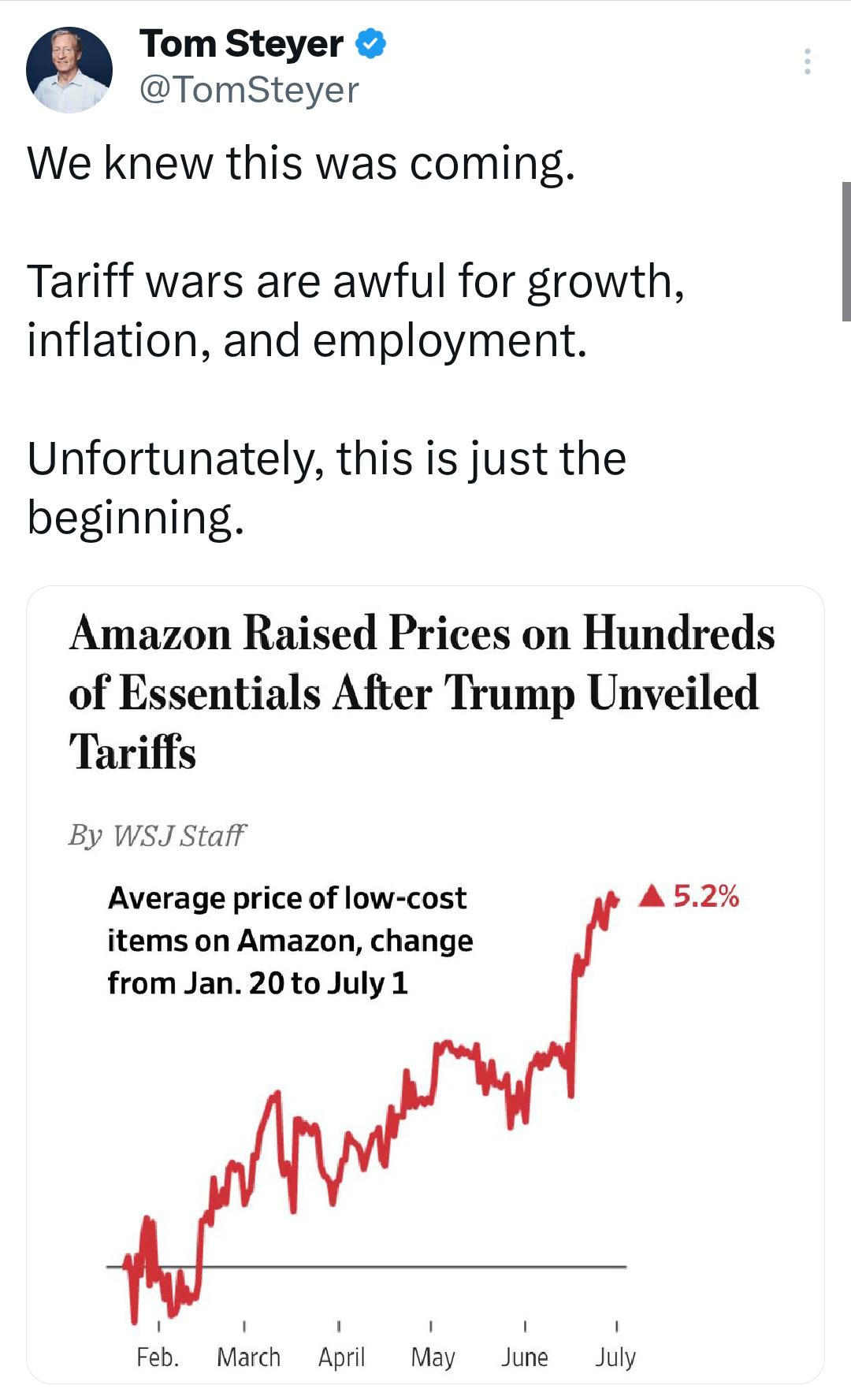

Andy Jassy just admitted something retailers have been quietly dreading: the tariff buffer is gone. For months, Amazon and third-party sellers loaded up on inventory bought at pre-tariff prices. That stockpile kept prices artificially low while the real cost of doing business climbed behind the scenes. Now that supply has "run out," as Jassy told CNBC, consumers are finally seeing what tariffs actually cost.

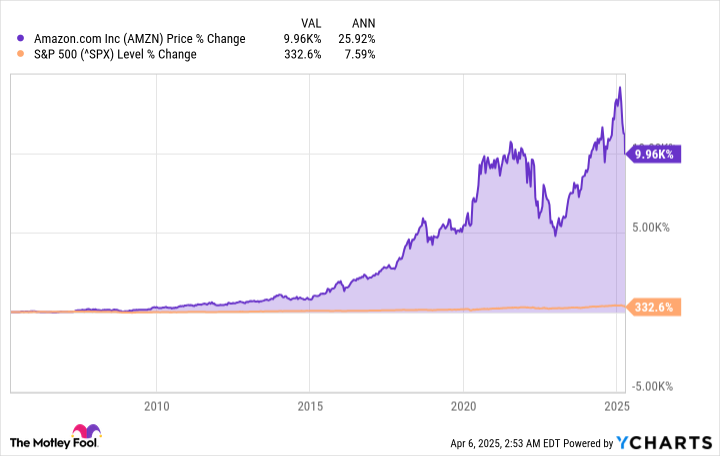

This isn't some abstract economic prediction anymore. It's happening now, in real time, across millions of products on Amazon's platform. And it matters because Amazon isn't just a retailer—it's the lens through which most Americans see pricing. When prices jump there, it signals a broader shift in the entire e-commerce and retail landscape.

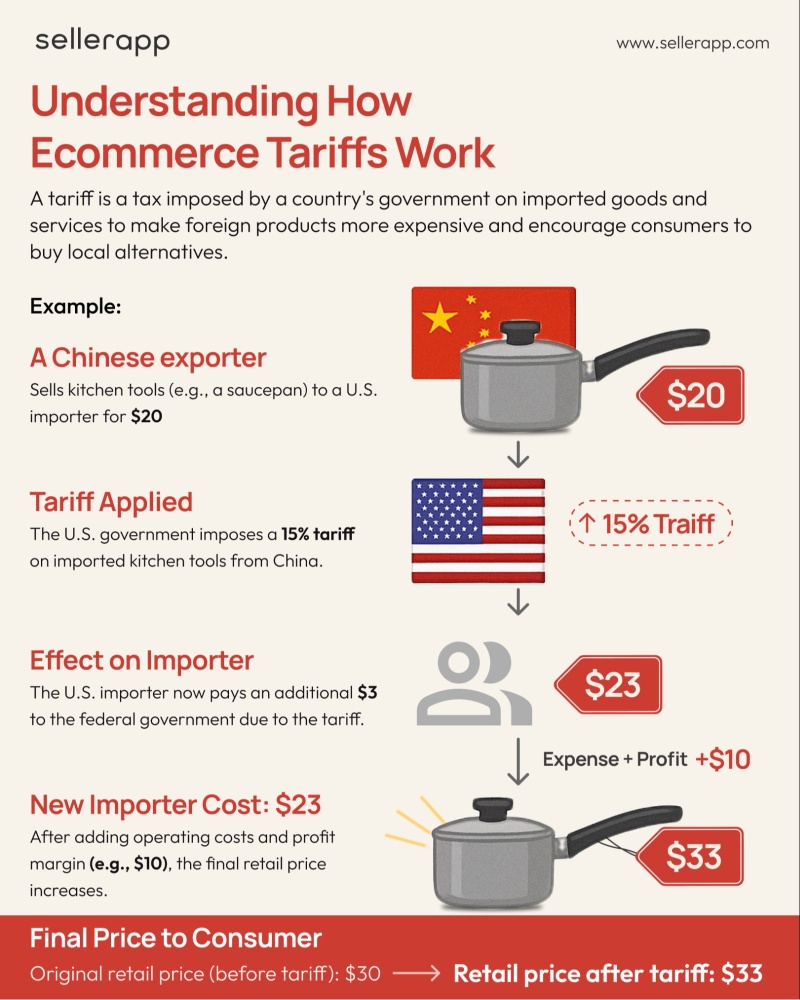

The tariff situation is more complex than "prices go up because tariffs." It's about supply chain management, inventory strategy, margin pressure, and a fundamental question about who absorbs the cost. Are sellers going to eat the difference and sacrifice profit? Are they going to pass it to consumers? Or is there some middle ground where prices rise moderately while margins compress?

Jassy's comments reveal that there isn't really a middle ground anymore. The inventory buffer that allowed Amazon to cushion the blow is depleted. What happens next depends on dozens of interconnected decisions made by thousands of sellers, each facing the same impossible calculation: raise prices or accept lower profits.

TL; DR

- Tariff buffer depleted: Amazon's prebought inventory at pre-tariff prices has run out, forcing price increases

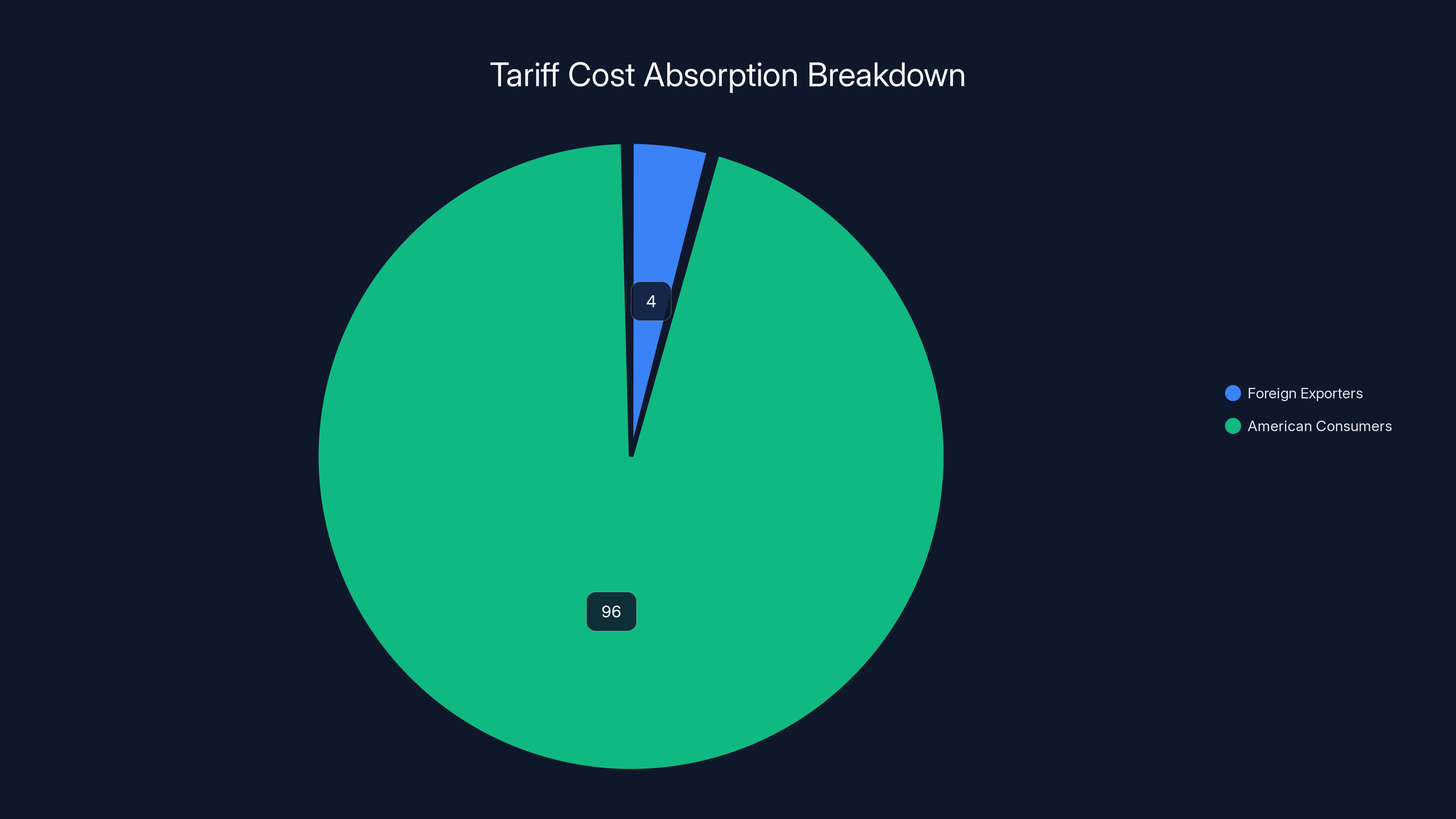

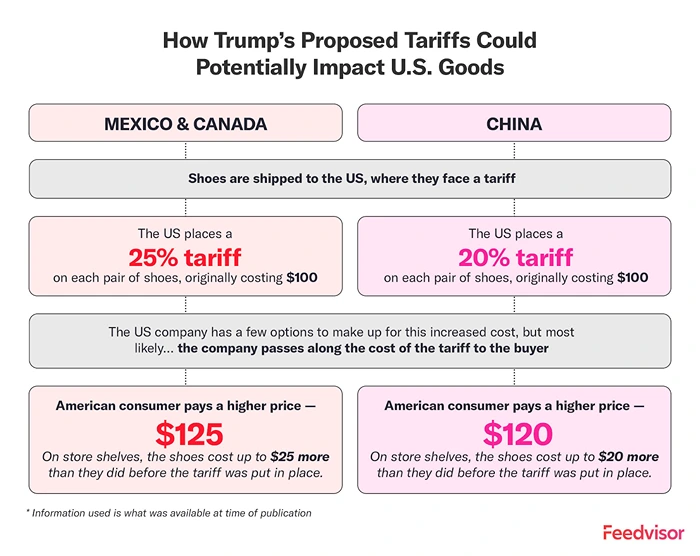

- 96% passed to consumers: A study from the Kiel Institute found foreign exporters absorb only 4% of tariff costs, while 96% is passed to consumers

- Sellers have limited options: A 10% cost increase doesn't have many places to hide—prices will likely rise

- De minimis loophole closed: Trump's executive order blocked the duty-free entry of low-cost goods, eliminating another cost-reduction pathway

- Bottom line: Expect gradual price increases across Amazon's platform throughout 2025 and beyond

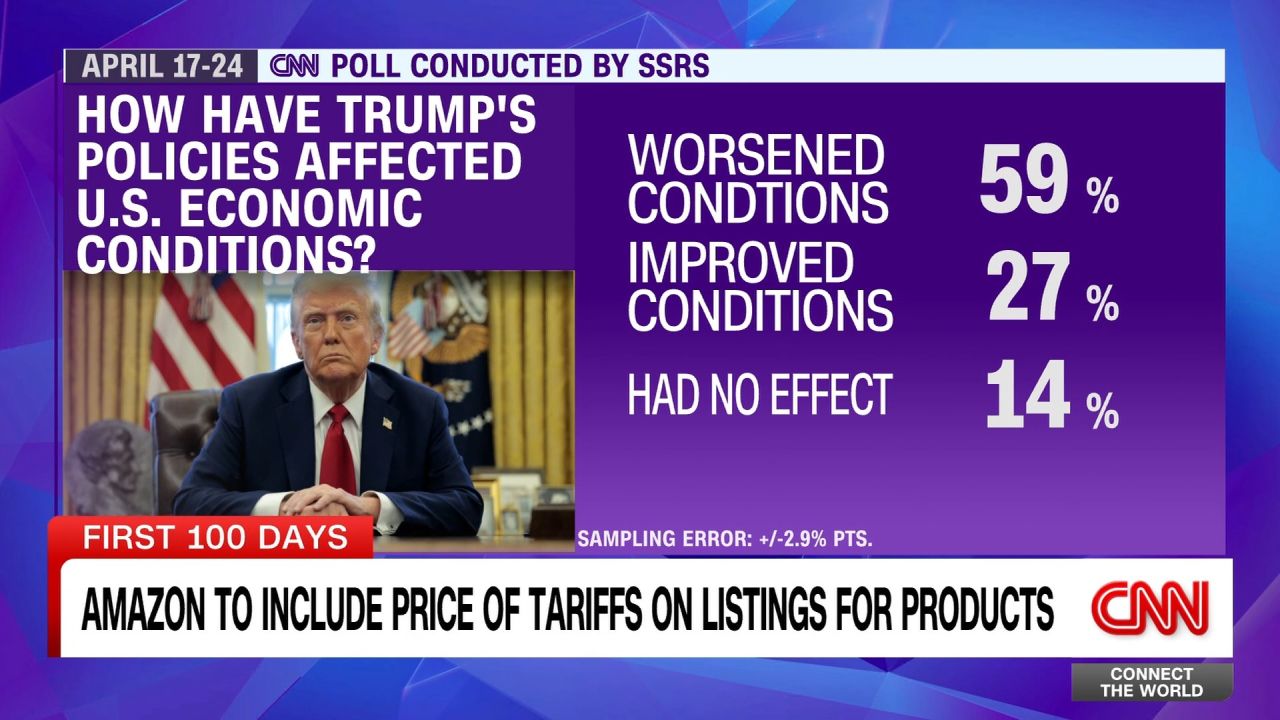

The study reveals that American consumers absorb 96% of tariff costs, while foreign exporters only absorb 4%, challenging the notion that tariffs primarily impact foreign producers.

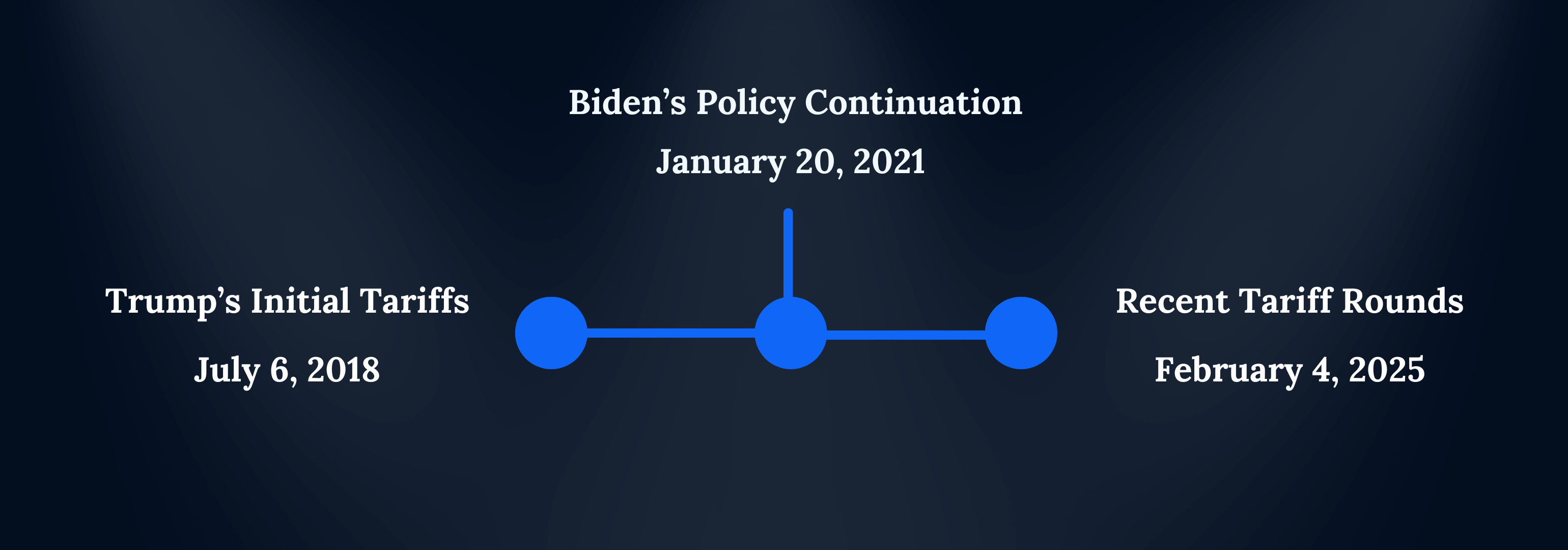

The Tariff Timeline: How We Got Here

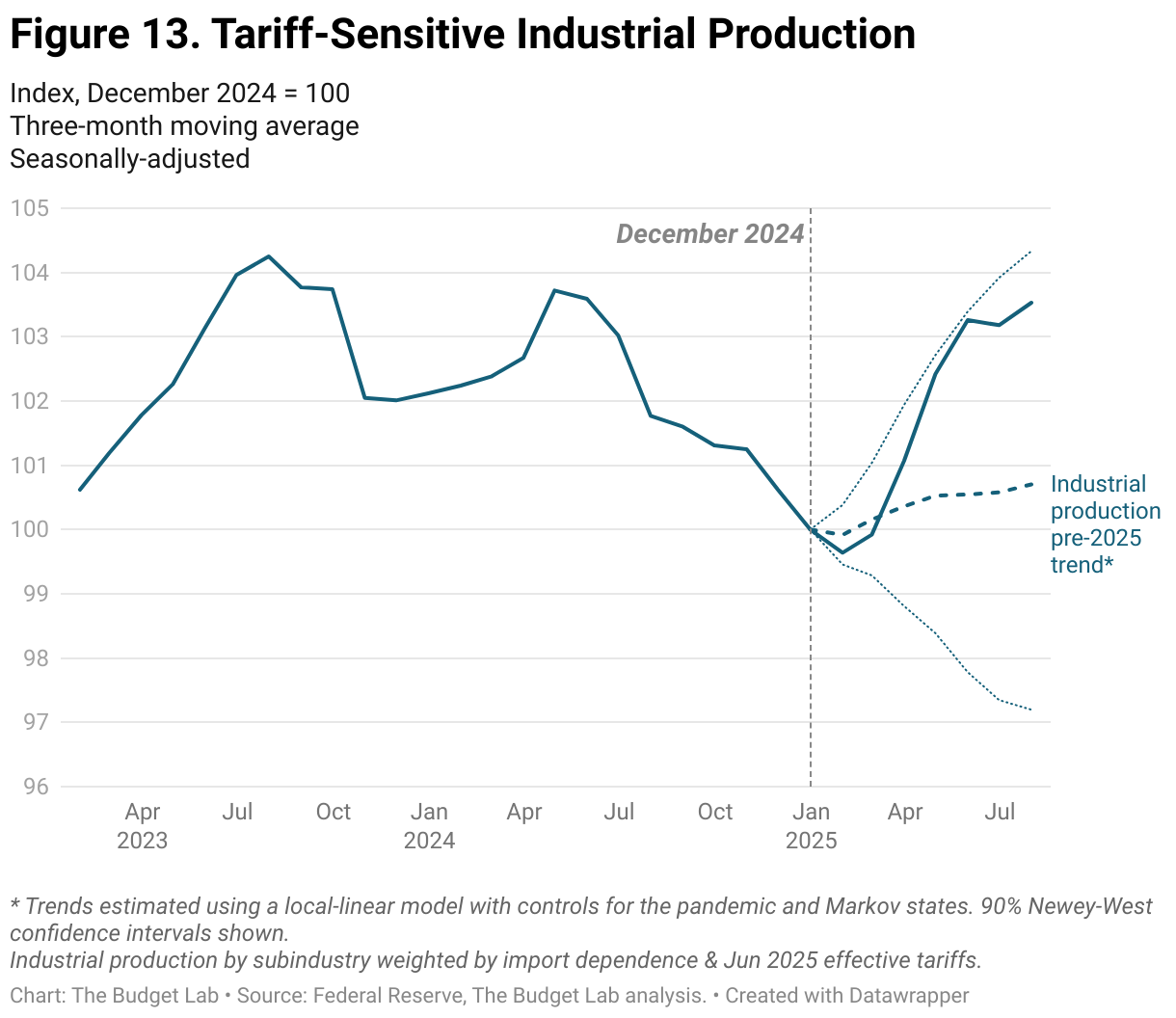

Understanding what's happening now requires rewinding the tape to early 2025. When President Trump's tariff policies began taking shape, retailers faced an immediate problem: future costs would be higher, but immediate prices would stay low because goods already in the supply chain had been purchased before the tariffs kicked in.

Amazon's response was pragmatic. The company, along with thousands of third-party sellers, made a calculated bet. Buy now, at pre-tariff prices, and stockpile inventory. This created a temporary price cushion. Consumers saw stable or even declining prices through early 2025 because retailers were liquidating cheaper inventory purchased months earlier.

This strategy worked beautifully for about six months. During that window, Amazon could advertise competitive prices while the company quietly absorbed the higher costs of tariffs on incoming goods. It was a classic supply chain arbitrage play: buy before prices rise, sell while holding the line on prices, and use inventory to bridge the gap.

But here's the reality about stockpiling: it's finite. You can only buy so much inventory before you run out of storage, capital, and market demand. And once that prebought supply exhausts, you're buying into an expensive tariff environment. There's no more buffer. No more bridge. Just the hard math of higher input costs meeting market prices.

Jassy's admission to CNBC signals that Amazon is at that inflection point. The prebought inventory is gone. What's coming in now carries tariff costs baked into the purchase price. And that's where pricing power—or lack thereof—becomes the real story.

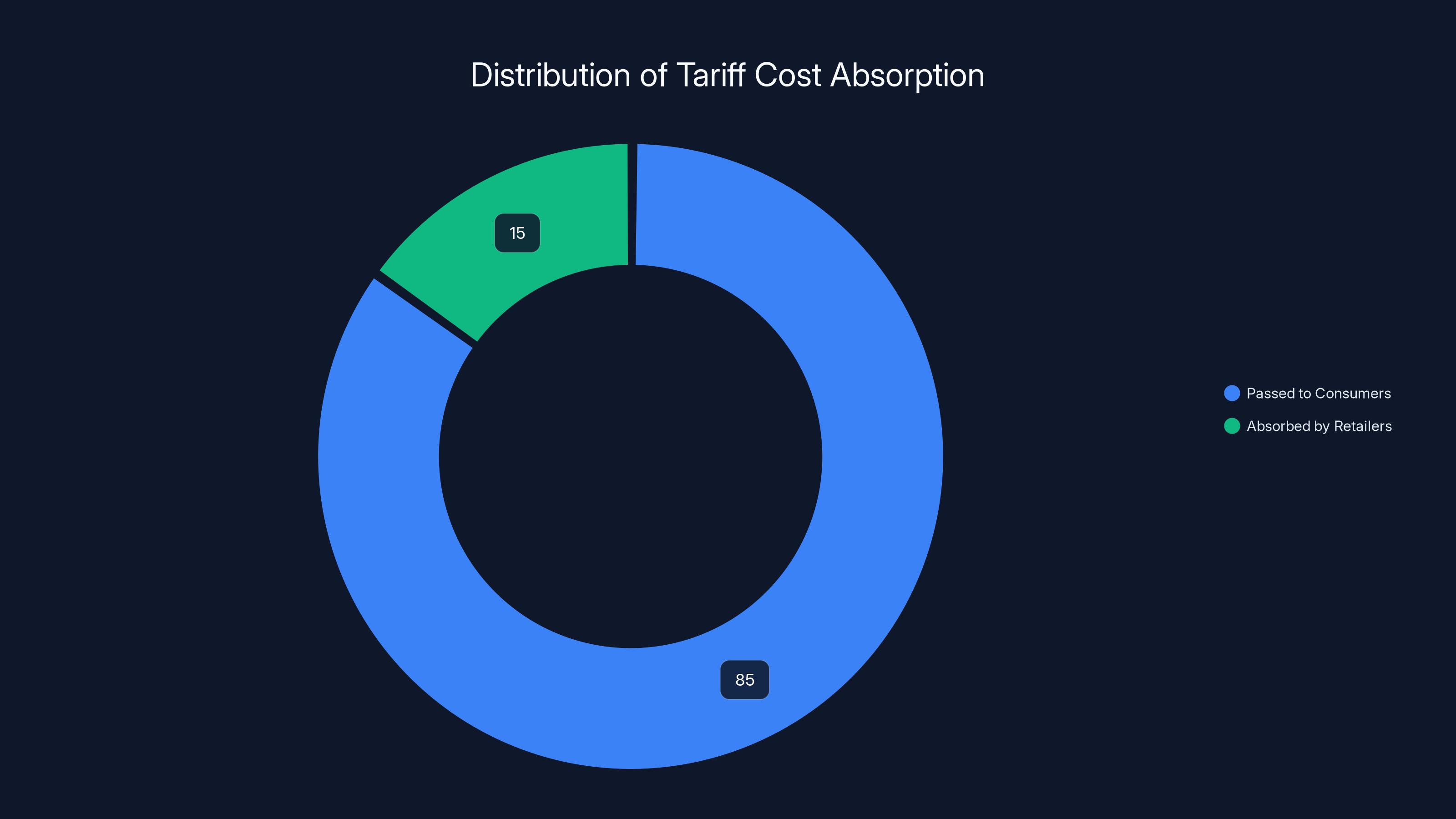

Approximately 85% of tariff costs are passed on to consumers, while retailers absorb about 15%, reflecting limited margin flexibility. Estimated data based on typical scenarios.

The Economics of Tariff Absorption: Who Really Pays?

One day before Jassy's CNBC interview, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy published research that should make every consumer uncomfortable. The study examined how tariffs actually flow through global supply chains, and the findings were stark: foreign exporters absorb just 4 percent of tariff costs. American consumers absorb 96 percent.

Let that sink in. If a tariff increases the cost of goods by

This destroys a common political talking point. Supporters of tariffs sometimes argue they primarily hurt foreign competitors, forcing them to absorb costs or exit the market. The data suggests otherwise. Foreign exporters are remarkably good at passing costs downstream. They don't eat the tariffs—they pass them along.

So who does absorb them? Primarily American retailers and consumers. A retailer like Amazon faces a choice: raise prices and risk losing volume, or absorb the cost and squeeze margins. In competitive categories where margin pressure is already intense, retailers often choose the former. They raise prices because the alternative—accepting lower profits on every unit sold—compounds across millions of transactions.

Consider a hypothetical example. Suppose Amazon sells 100 million units of imported goods annually. If tariffs add

In practice, retailers split the difference. Some costs get absorbed (especially on low-margin, high-volume items where price competition is fiercest). Other costs get passed to consumers (especially on branded items where consumers have less price elasticity). The exact breakdown depends on competitive dynamics, margin structure, and category-specific factors.

Jassy's comment that "some sellers are deciding that they're passing on those higher costs to consumers in the form of higher prices" confirms this mixed approach. Some absorption, some pass-through. But with the inventory buffer gone, the trend is clearly toward higher pass-through rates.

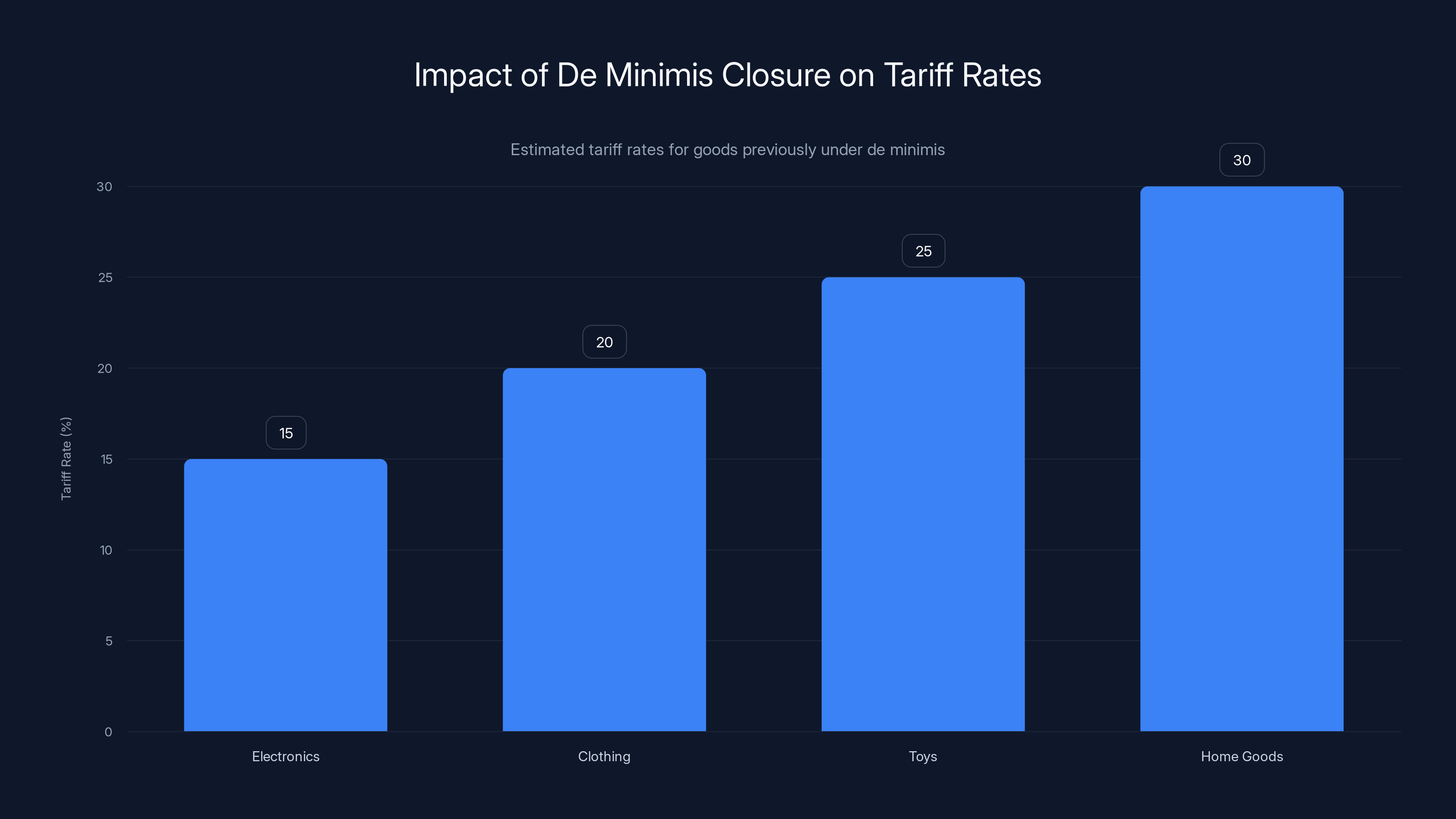

Understanding De Minimis Closures and What It Means for Pricing

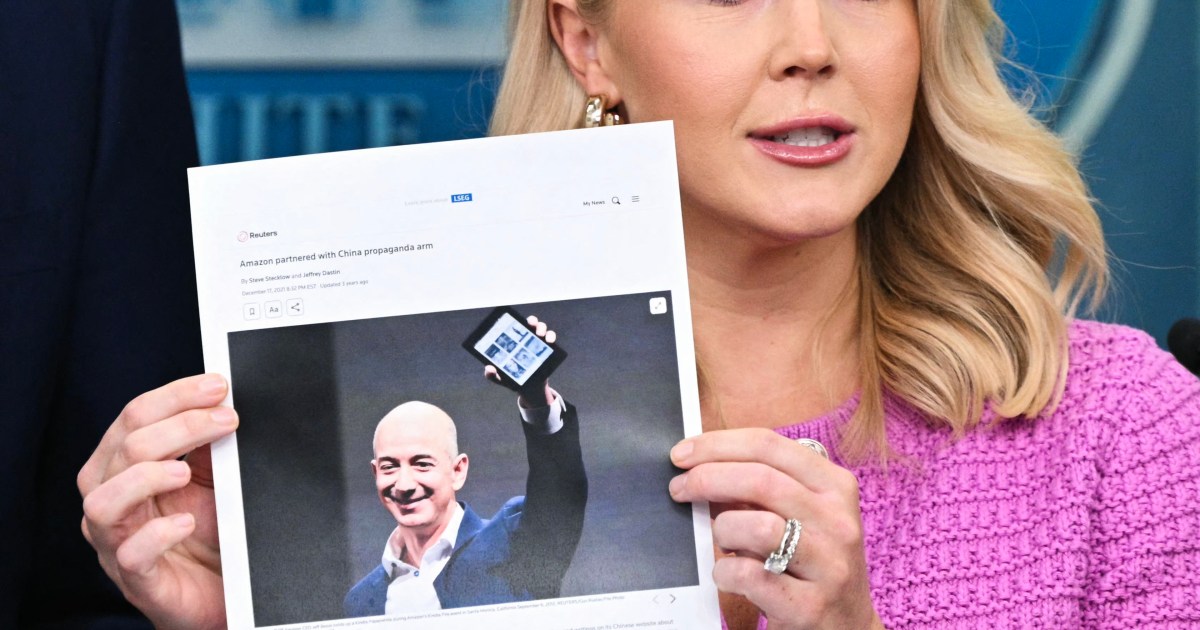

Before August 2024, there was a small quirk in U.S. import law that mattered a lot for e-commerce: the "de minimis" loophole. Goods valued under $800 (adjusted periodically) could enter the U.S. duty-free. This created an arbitrage opportunity for low-cost goods from China, India, and other manufacturing hubs.

Think about how Ali Express, Temu, and similar platforms worked. They shipped directly to consumers, and because most individual packages were valued under $800, they avoided import duties entirely. This made pricing extraordinarily competitive—there was simply no tariff cost embedded in the final price.

Trump's executive order to close this loophole went into effect in August 2024. Now those same goods are subject to standard tariffs, which range from 15 to 60 percent depending on the category.

This change has two major implications for Amazon pricing. First, it eliminates a low-cost competitor for certain categories. Temu and Ali Express customers were often price-sensitive buyers willing to accept slower shipping in exchange for extremely cheap goods. Without the de minimis loophole protecting their pricing, these platforms become less competitive. Amazon's bargain-hunting customers might have fewer ultra-cheap alternatives.

Second, and more directly relevant to Jassy's comment, it removes a cost-containment lever for Amazon. The company could have theoretically used small-shipment de minimis imports to fill inventory gaps. That's now much more expensive. Every unit coming in through that channel now carries a tariff.

Jassy acknowledged this constraint in his CNBC interview: "If people's costs go up by 10 percent, there aren't a lot of places to absorb it. So we're going to do everything we can to work with our selling partners to make prices as low as possible for consumers—but you don't have endless options."

That's the key phrase: "endless options." Amazon has tried various tactics to manage tariff pressure—inventory strategies, supplier negotiations, margin compression, marketplace fee adjustments. But there are limits to how many levers you can pull before you run out of solutions. Once the inventory buffer is gone, once the de minimis loophole is closed, and once supplier negotiations have maxed out, the remaining option is pricing.

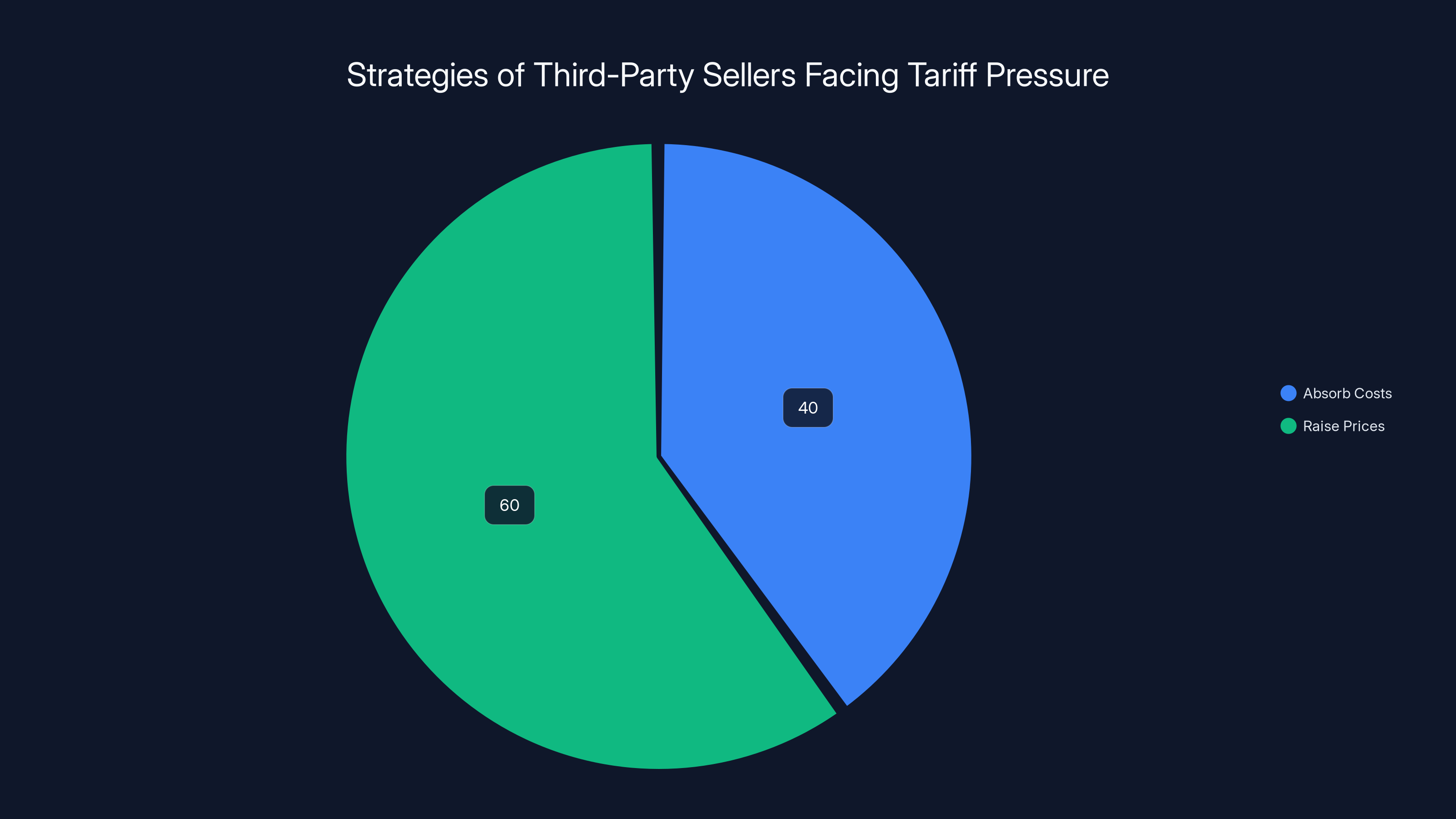

Estimated data suggests that 60% of third-party sellers raise prices to cope with tariff pressures, while 40% absorb costs to maintain demand.

How Third-Party Sellers Navigate Tariff Pressure

Amazon Marketplace includes roughly 2 million third-party sellers. These aren't Amazon employees—they're independent businesses using Amazon's platform to reach customers. And they're facing a completely different tariff situation than Amazon's first-party retail operations.

For Amazon's internal business, tariff costs hit the company's procurement budget. The company has options: accept lower margins, negotiate with suppliers, optimize inventory, or pass costs to consumers. Amazon has leverage because of its scale.

Third-party sellers typically have much less leverage. A small seller importing electronics or home goods from Asia faces tariff costs they can't negotiate around. They can't use scale to absorb the costs. They don't have the margin depth to compress. Their primary options are raise prices or reduce volume.

Jassy acknowledged this directly: "Some sellers are deciding that they're passing on those higher costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. Some are deciding that they'll absorb it to drive demand."

The second group—sellers absorbing costs to drive demand—typically consists of high-volume, high-margin sellers or those betting on volume growth to compensate for margin compression. They're making a strategic decision to protect market share or ranking (Amazon's algorithm favors higher sales volume) at the expense of short-term profit.

The first group—sellers raising prices—includes everyone else. Smaller sellers with limited margin depth, sellers in competitive categories, sellers without the capital to absorb losses. They're raising prices because it's the only viable option.

This creates a bifurcated marketplace. Premium sellers with scale and capital raise prices less dramatically. Smaller sellers raise prices more aggressively, pricing themselves into less competitive positions. Over time, this could accelerate consolidation, pushing smaller sellers out and concentrating more of Amazon's marketplace volume among larger, better-capitalized competitors.

This dynamic has ripple effects. Smaller sellers are a source of innovation and niche products on Amazon. If tariffs force them to exit, the overall product selection available to consumers shrinks. That's a secondary cost of tariff policy that doesn't show up in price comparisons but affects consumer choice and marketplace diversity.

Tariff Categories and Price Impact Variation

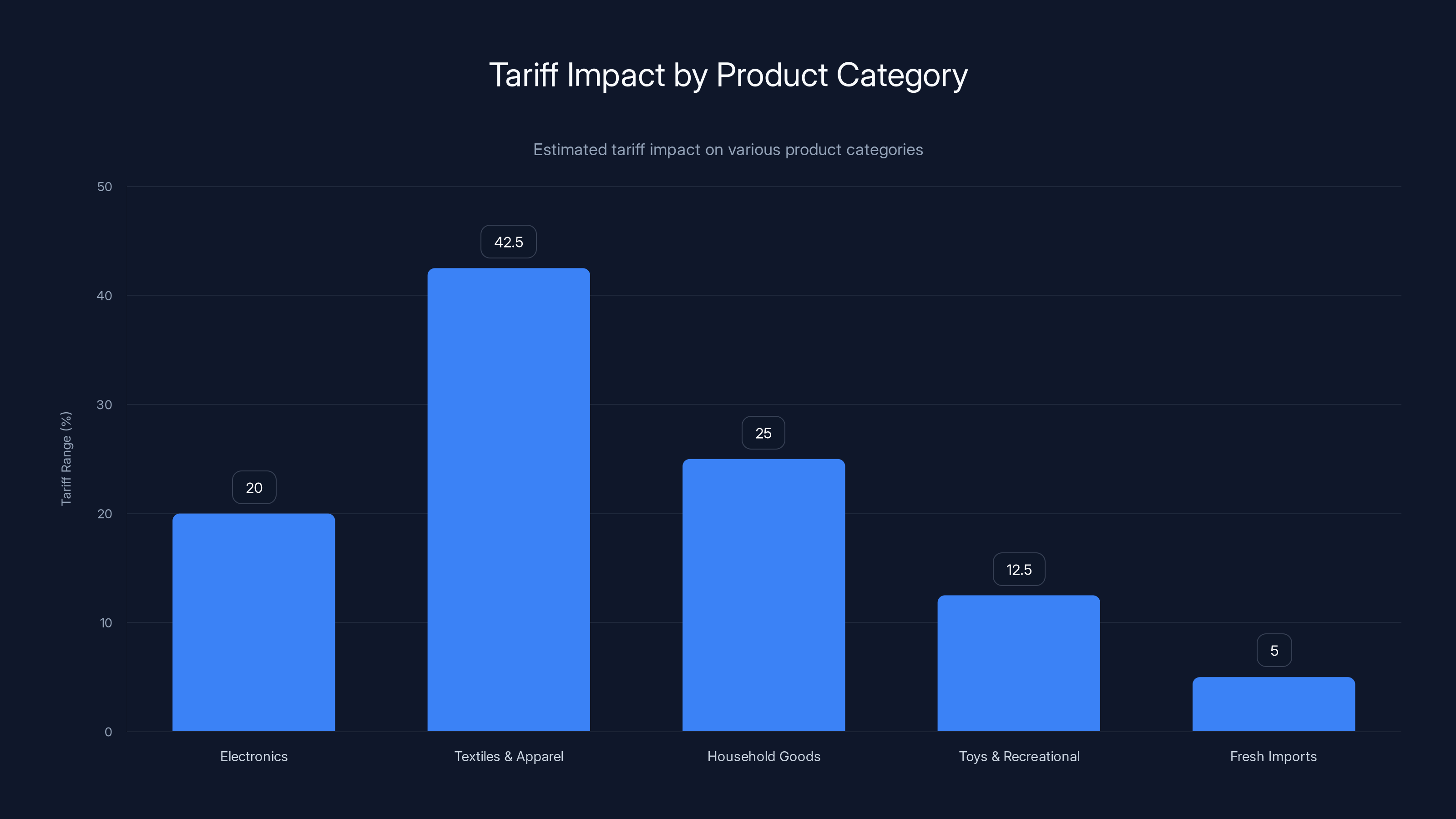

Not all tariffs are created equal, and not all categories will see the same price impact. Import tariffs vary dramatically by product type, ranging from roughly 15 percent on some categories to over 60 percent on others. Understanding which categories face higher tariff burdens helps predict where price increases will be most visible.

Electronics face tariffs in the 15-25 percent range for most components and finished goods. This is significant—a

Textiles and apparel face much higher tariffs, sometimes 25-60 percent depending on the specific garment and origin. This hits hard because apparel is extremely price-competitive. A retailer can't easily raise t-shirt prices without losing volume. Amazon sellers of apparel should expect significant margin pressure. Some will likely reduce inventory depth in affected categories.

Household goods and furniture typically face 15-35 percent tariffs. These categories have been seeing slow growth anyway, so tariff-driven price increases might just accelerate existing shift patterns. Consumers considering furniture purchases might defer or reduce average order values.

Toys and recreational equipment face 10-15 percent tariffs in many cases. Holiday seasons could be particularly affected—parents price-shopping for Christmas gifts might see meaningful price increases on toys and games.

Freshly imported goods (food, beverages, supplements) face lower or no tariffs in many cases, but agricultural goods have complex tariff structures that vary by specific product. This category is less likely to see dramatic Amazon price increases.

The key insight: categories with already-thin margins will see the biggest consumer price impact, because retailers have less cushion to absorb tariff costs. Categories with deeper margins might see more absorption, keeping consumer prices flatter while retailer profits compress.

Estimated data shows textiles and apparel face the highest tariffs, averaging 42.5%, while fresh imports are least affected with an average of 5%.

Supply Chain Adaptation: Can Sourcing Shifts Reduce Tariff Impact?

One tariff-mitigation strategy that's been discussed but rarely executed at scale: shift production to low-tariff countries. The U.S. has various trade agreements that reduce or eliminate tariffs on goods from specific countries. If suppliers could shift production to these countries, they could reduce tariff costs.

In practice, this rarely happens quickly or dramatically, for several reasons. Manufacturing infrastructure is built over decades. Shifting production requires capital investment, worker training, quality control systems, and supply chain rebuilding. A supplier can't move a factory to Vietnam or Thailand overnight.

Second, the cost advantage of shifting production has to exceed the costs of actually shifting. For goods with deeply embedded supply chains in China—nearly everything consumer electronics, for example—the capital and logistical costs of shifting might not be justified unless tariffs are expected to persist for years.

Third, trade agreements themselves come with requirements. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), for example, has local content requirements. Shifting production to Mexico might reduce tariffs but requires that certain percentage of value be added in Mexico or North America. That's expensive to implement.

So while supply chain adaptation is theoretically possible, it's unlikely to materially reduce tariff impact in the short term (next 12-18 months). Suppliers will absorb costs, negotiate with retailers, or accept margin compression. They won't fundamentally restructure global supply chains in response to tariff policy.

What we might see: slower adaptation over longer periods. A supplier might gradually increase Vietnam sourcing for certain electronics categories over 18-24 months as new production capacity comes online. But this won't show up as a tariff cost reduction in the near term.

Jassy's comment about "endless options" reinforces this. Amazon and its sellers have exhausted the quick levers. What remains requires structural changes with longer time horizons.

Consumer Behavior Shifts Driven by Tariff Pricing

When prices rise, consumer behavior changes. This isn't controversial—it's basic economics. The question is how much behavior will shift and in which categories.

Amazon Prime members might see price increases as more tolerable than non-members. Why? Because they've already paid for membership. The perceived cost of the additional purchase is just the product price, not product price plus membership. This might shift more purchasing toward Prime-eligible items even if non-Prime alternatives are cheaper.

Consumers shopping for discretionary goods (nice-to-have items) are more price-sensitive than those shopping for essential goods. A 10 percent price increase on a must-buy item (replacement phone screen, replacement air filter) might barely dent volume. The same 10 percent increase on a nice-to-have item (decorative throw pillows, gadgets) could significantly reduce volume.

Price-sensitive segments—lower-income consumers, students, budget-conscious shoppers—will likely shift behavior most dramatically. They might reduce order frequency, buy lower-quality alternatives, or shift to Walmart, Target, or other retailers. Higher-income consumers might barely notice or change behavior.

This creates a subtle but important dynamic: tariff pass-through might accelerate wealth inequality in consumption. Wealthier consumers absorb price increases without changing behavior. Lower-income consumers must adjust downward, buying fewer items, lower quality, or shopping elsewhere. Over time, this could reshape which products succeed on Amazon—premium items might maintain volume while budget items see steeper declines.

Category-specific shifts are likely too. Consumers might defer furniture and home improvement purchases (easy to delay) while maintaining spending on essentials and consumables. This could create a visible shift in Amazon's product mix throughout 2025.

Estimated data shows that closing the de minimis loophole subjects goods to tariffs ranging from 15% to 30%, impacting pricing competitiveness.

The Role of Amazon's Marketplace Fees in Tariff Mitigation

Here's a less-discussed lever Amazon could pull: reduce marketplace seller fees. Currently, Amazon charges sellers roughly 6-45 percent commission depending on category (excluding fulfillment fees). This is where Amazon extracts most of its profit from the Marketplace.

Theoretically, Amazon could reduce these fees as a way to help sellers manage tariff costs without raising consumer prices. Lower fees would give sellers more margin cushion to absorb tariff costs. It's a hidden price reduction that doesn't appear as a price cut.

Jassy didn't mention this strategy in his CNBC interview, which probably means Amazon isn't planning to reduce fees. Why? Because Amazon's margin from Marketplace is under pressure from competition (Walmart, Alibaba, Tik Tok Shop) and from investors demanding profit growth. Reducing fees to help sellers manage tariff costs would mean Amazon sacrificing profit to subsidize sellers, which shareholders generally oppose.

More likely: Amazon keeps fees steady or increases them selectively in categories where demand remains strong. This effectively shifts more of the tariff burden onto third-party sellers, who then pass it to consumers.

This creates an interesting dynamic. Amazon could unilaterally fix much of the tariff problem by reducing fees. The company chooses not to, because profit protection is a higher priority. This suggests that tariff-driven price increases are actually being enabled by Amazon's fee structure. The company is extracting value from sellers who are absorbing tariff costs.

This probably won't be a major talking point in the tariff debate, but it's worth noting. Amazon has agency here. The company is making conscious choices that will result in higher consumer prices rather than accepting lower profits.

Comparing Price Trajectories Across Retailers

Amazon isn't the only retailer dealing with tariff pressure. Walmart, Target, Best Buy, and every other major retailer is facing identical tariff costs. The question is whether pricing will rise uniformly across retailers or whether some will protect prices better than others.

Walmart has significant scale advantages. The company buys enormous volumes and can negotiate supplier concessions that smaller retailers can't access. Walmart might keep price increases smaller than Amazon, potentially in the 3-5 percent range rather than 5-10 percent.

Target is in a similar position to Walmart but with less scale. Price increases might land in the 4-7 percent range.

Specialty retailers (Best Buy for electronics, furniture retailers for furniture, etc.) have less scale. Price increases could be steeper, 6-12 percent, because they have fewer negotiating options and less supplier leverage.

Amazon is in an interesting middle position. The company has enormous purchasing power for goods sold under the Amazon brand. But Amazon Marketplace is full of independent sellers with far less leverage. So Amazon-brand price increases might be moderate (4-6 percent) while Marketplace price increases are steeper (6-12 percent).

This pricing divergence could have consequences. If Walmart keeps prices lower than Amazon, price-sensitive consumers might shift purchasing to Walmart. Luxury retailers with deeper margins might barely raise prices. Discount retailers like TJ Maxx and Dollar Tree might actually benefit—they become relatively more affordable as mainstream retailers raise prices.

The tariff impact on retail competition could be substantial. It's not just about absolute price levels. It's about relative competitive positioning. If Walmart keeps prices lower than Amazon, that's a strategic win for Walmart. It builds customer loyalty and market share.

Estimated data suggests that by the end of 2025, prices across various categories will increase by 5-15% due to tariff impacts.

Exploring Alternative Supply Sources and Sourcing Strategies

Beyond shifting production to different countries, there are other sourcing strategies that could reduce tariff burden. Some are already in motion.

Domestic sourcing is one obvious option. If a product can be made in the U.S., there are no tariffs. But U.S. manufacturing costs are typically 2-3 times higher than offshore manufacturing. For most consumer goods, the higher production cost exceeds the tariff savings. So domestic sourcing won't become widespread unless tariffs rise dramatically or labor costs fall significantly.

Regional manufacturing (nearshoring to Mexico or Central America) reduces tariffs and shipping costs compared to Asian manufacturing. Several companies have piloted this for certain categories, but it requires capital investment and typically results in higher production costs than Chinese manufacturing. For high-volume, low-margin goods, the economics don't work. For specialized or higher-value goods, nearshoring makes more sense.

Dropshipping and on-demand manufacturing are other options. Instead of buying inventory and paying tariffs upfront, sellers could use dropshipping relationships where suppliers hold inventory and ship directly to consumers. This reduces tariff burden (fewer tariffs per unit sold) and inventory risk. The tradeoff is lower margins and less control over product quality and delivery times.

Private label and brand-exclusive sourcing could actually benefit from tariffs. If a brand can negotiate exclusive sourcing agreements with suppliers in tariff-favorable countries (Vietnam, India, Thailand for certain goods), it might access lower tariff rates than competitors using broader sourcing. This would give brands a competitive advantage worth protecting through private label strategies.

Jassy likely isn't planning to dramatically shift sourcing strategies in the near term. Instead, Amazon will manage through pricing, inventory optimization, and supplier negotiations. Longer-term sourcing changes might happen over 18-24 months, but don't expect them to materially reduce tariff pass-through in 2025.

Historical Tariff Lessons and Long-Term Implications

This isn't the first time the U.S. has implemented broad tariffs. History offers lessons, though tariff situations are never identical.

The 2018-2019 Trump tariffs on Chinese goods (starting at 25 percent) led to measurable price increases for consumers. A Federal Reserve study found that tariffs increased prices for affected goods, with pass-through rates of 50-90 percent depending on category. That is, if a tariff added

Unlike that 2018 situation, the current tariff environment is broader and includes multiple countries, not just China. It also includes the de minimis closure, which was absent in 2018. This suggests pass-through rates could be even higher than the 2018 experience.

Historically, tariff effects compound over time. Initial price increases are moderate (3-5 percent) as retailers absorb costs and optimize inventory. But as inventory normalizes and competition pressures mount, pass-through accelerates. Prices can rise 7-15 percent by year-end even if tariffs were consistent throughout the year.

The timing also matters. Early tariff implementation in early 2025 means price acceleration could happen gradually throughout the year, making the full impact less obvious to consumers in any single week or month. By late 2025, the cumulative effect might be quite significant.

Declining purchasing power is a secondary but important effect. If prices rise 5-10 percent but wages stay flat, consumers effectively lose purchasing power. They can buy less with the same money. This depresses overall e-commerce growth and retail spending, potentially reducing total online sales even as transaction prices increase.

One more historical lesson: tariff effects persist even after tariffs are removed. Consumers adjust expectations. Prices rarely fall back to pre-tariff levels even if tariffs are eliminated. There's a "ratchet effect"—prices ratchet up but don't ratchet down symmetrically. So even if tariffs were reversed tomorrow, prices would likely stay elevated for months or years.

Predicting Price Increases by Category Through End of 2025

Based on current tariff rates, inventory depletion timelines, and typical retail margin structures, here's a rough forecast of where Amazon prices might be by end of 2025.

Electronics and Smart Home: Expect 5-10 percent price increases by end of 2025. Initial increases (now through June) will be 2-4 percent as retailers absorb some costs and manage inventory transitions. Acceleration (July-September) will drive increases to 5-8 percent. Final quarter (October-December) could see 8-10 percent if competitive dynamics stabilize and retailers cement higher price points.

Clothing and Textiles: This category faces higher tariffs (25-60 percent depending on garment type), so expect larger increases: 7-15 percent by end of year. Inventory buffer in textiles is typically lower than electronics, so depletion happens faster. Acceleration could begin earlier (April-May).

Home Goods and Furniture: Expect 6-12 percent increases. These categories have lower margin density than electronics, so pass-through is likely to be higher. Demand is also more discretionary, so retailers might use pricing to manage volume rather than absorb costs.

Books and Media: Expect 3-6 percent increases. Many books are printed domestically or in tariff-favorable countries. Media is less subject to tariff pressure.

Food and Consumables: Expect 2-5 percent increases. These categories have complex tariff structures but are less exposed than durables. Demand is also less elastic for true consumables.

High-Margin Luxury and Premium: Expect 3-7 percent increases. These categories have margin depth to absorb costs. Luxury consumers are less price-sensitive, so retailers can implement smaller price increases without losing volume.

These are estimates, not predictions. Actual results depend on competitive dynamics, consumer response, and potential policy changes. But the direction is clear: prices are rising, and they'll continue rising throughout 2025 as inventory buffers deplete.

Policy Alternatives and Potential Tariff Modifications

One important caveat: tariff policy isn't fixed. The Trump administration could modify tariffs, implement exemptions, or change enforcement. Any such changes would dramatically alter the pricing trajectory.

Potential modifications could include sector-specific exemptions (electronics exemptions, for example, could be politically popular if price increases become visible during holiday shopping). These would provide immediate relief to affected retailers and consumers.

Alternative policies could include tariff reduction on specific items (luxury goods, components, raw materials) while maintaining tariffs on finished goods. This would reduce manufacturing costs without fully eliminating tariff pressure.

Negotiated trade deals with specific countries could lower tariff rates for specific products. For example, an expanded agreement with Vietnam or Thailand could reduce tariffs on apparel sourced from those countries.

Tariff credits or business tax adjustments could help retailers and small businesses absorb costs. These would be less visible to consumers but would reduce price pressure.

The probability of any of these changes is unknown. Political considerations might outweigh economic concerns. But if price increases become visible enough to generate consumer backlash, policy modification is possible.

Jassy's comments suggest Amazon isn't expecting policy changes in the near term. The company is planning for persistent tariffs and adjusting pricing accordingly. But this could change if political pressure mounts.

What This Means for Your Shopping Habits and Budget

Amazon price increases aren't hypothetical—they're happening. Here's what to do about it.

First, make planned purchases sooner rather than later if you're considering discretionary items. That gadget you might buy in June is likely cheaper in May. That furniture upgrade you were considering for fall might be worth doing now.

Second, use price tracking tools. Amazon has built-in price history. Camel Camel Camel offers historical price tracking for Amazon items. If you're watching a specific product, monitor whether prices are rising in real time. You'll see the tariff effect happening.

Third, compare across retailers. Amazon has pricing advantages in many categories but not all. If Walmart or Target has lower prices for items you're buying regularly, shifting some purchases could save meaningful money over the year.

Fourth, consider Prime value differently. Amazon Prime includes Amazon Prime Video and other benefits. If you're primarily subscribing for shipping, the calculus might change if shipping costs rise or if Amazon's prices rise relative to competitors. Re-evaluate whether the membership remains cost-effective.

Fifth, shift consumption patterns if possible. If you typically buy new items frequently, consider buying durable goods that last longer instead. If you buy individually wrapped items, consider bulk purchases. These shifts reduce overall purchases needed and can help maintain spending levels even as prices rise.

Sixth, reduce basket size incrementally. Instead of making one

FAQ

What exactly does Andy Jassy mean by tariffs "creeping into" pricing?

Jassy means that Amazon and sellers previously had inventory purchased before tariff policies took effect. They could sell that inventory at lower prices because they didn't have tariff costs embedded in their cost basis. Now that inventory is depleted, new inventory coming in has tariffs baked in. Those tariff costs are now visible in retail prices—they're "creeping in" as new inventory replaces old. It's not dramatic overnight changes; it's gradual pressure as the cheap inventory buffer runs out and must be replaced with tariff-inclusive inventory.

Will Amazon prices stay high permanently or eventually return to lower levels?

Prices are unlikely to return to pre-tariff levels unless tariff policies change substantially. Even if tariffs are eliminated, retailer behavior suggests prices won't fall back down. There's a "ratchet effect"—prices go up when costs increase, but they don't go down proportionally when costs decrease. Consumers adjust to new price points and accept them as normal. So expect current price increases to persist even if tariffs are eventually reduced or eliminated. The only scenario where prices clearly fall is if tariff policy reverses completely and aggressively.

How much of the tariff cost will Amazon absorb versus pass to consumers?

Based on the Kiel Institute study, roughly 96% of tariff costs get passed to consumers while only 4% are absorbed by retailers and suppliers. In practice, Amazon will absorb more than 4% on items with deep margins (popular electronics, bestselling books) and less on items with thin margins (commodity goods, budget items). Overall, expect 80-90% of tariff costs to show up in consumer prices, with retailers absorbing 10-20%. This explains why Jassy says there "aren't a lot of places to absorb" cost increases—retailers have already squeezed margins about as hard as economically possible.

Will tariff-driven price increases accelerate or slow down throughout 2025?

Expect acceleration followed by stabilization. Initial increases (Q1-Q2) will be moderate (2-4%) as retailers absorb costs and manage inventory transitions. Acceleration (Q3-Q4) will drive increases to 5-10% as inventory buffers fully deplete and competitive dynamics stabilize around higher price points. By end of 2025, prices should reach a new equilibrium level and stabilize there unless tariff policy changes or new tariffs are added. So early 2025 is the "buy now" window before acceleration hits.

Are all Amazon sellers raising prices or just some?

Both. Larger, better-capitalized sellers with deeper margins are absorbing some costs and raising prices less aggressively (4-6%). Smaller sellers with thin margins are raising prices more aggressively (6-12%). Premium brands with strong pricing power are raising prices less because customers have less price elasticity. Budget sellers are raising prices more because they have less margin cushion. Overall, Marketplace prices are rising more than Amazon-brand prices because third-party sellers have less cost-management flexibility than Amazon's procurement team.

Could shifting to domestic or nearshoring manufacturing avoid tariffs?

Theoretically yes, but practically it's slow to happen. Shifting production requires capital investment, creates supplier relationship changes, and often results in higher production costs that exceed tariff savings. Some companies will gradually nearshore to Mexico or increase Vietnam sourcing over 18-24 months, but this won't meaningfully reduce tariff impact in 2025. Expect structural supply chain changes over years, not quarters. In the near term (2025), assume current tariff rates are sticky and prices will reflect those rates.

Will Amazon's Marketplace fees change as a result of tariff pressure?

Unlikely in the near term. Amazon makes the majority of Marketplace profit from fees (6-45% depending on category). Reducing fees to help sellers manage tariff costs would reduce Amazon's profit, which doesn't align with shareholder expectations or competitive positioning. More likely: Amazon keeps fees steady or increases them selectively, effectively shifting more tariff burden onto third-party sellers who then pass it to consumers. This is a less-discussed but important factor in tariff pass-through.

How do tariff price increases compare to historical inflation or normal retail price changes?

Tariff-driven increases (5-10% in many categories) are significantly larger than typical annual retail price inflation (2-3%). It's closer to the inflation rates seen during 2021-2023 (7-9%) but compressed into a shorter timeframe. The speed matters—consumers notice concentrated increases more than gradual changes. A 5-10% increase over 6 months is more noticeable than a 5-10% increase spread over 12 months, even though the annual rate is similar.

What happens if tariff policy changes or tariffs are reduced?

Price reductions would be gradual and incomplete. There's a "ratchet effect" where prices rise quickly when costs increase but fall slowly or not at all when costs decrease. Even if tariffs are eliminated tomorrow, expect prices to stay elevated for 6-12 months while retailers work through inventory and adjust expectations. Prices might eventually decline 1-2% from current levels but won't fully return to pre-tariff levels. Historical precedent from 2018-2019 tariff removals supports this pattern.

Should I shift my shopping to different retailers to avoid Amazon price increases?

Worth evaluating category-by-category. Walmart, Target, and specialty retailers face similar tariff pressures, so prices are rising across retail. However, some retailers (Walmart, Target) have more negotiating power and might keep increases smaller than Amazon in certain categories. Best Buy might have steeper increases for electronics because it's more dependent on imported goods. Compare prices across retailers for categories you buy frequently—you might find that Amazon prices rise less or more aggressively than competitors depending on category and competitive dynamics.

The Bottom Line: Preparing for a Higher-Price 2025

Andy Jassy's admission that tariffs are "creeping into" pricing confirms what supply chain analysts predicted months ago: the tariff buffer is depleted, and price increases are now inevitable. This isn't speculation or fear-mongering. It's the CEO of the world's largest e-commerce platform confirming that tariff costs are now flowing through to consumer prices.

The Kiel Institute study showing that 96% of tariff costs are passed to consumers reinforces what basic economics predicts: when input costs rise significantly, sellers don't absorb them. They pass them through. Amazon, third-party sellers, and consumers all face higher effective prices now that tariff barriers are in place.

The mechanics are straightforward: prebought inventory at pre-tariff prices is gone, the de minimis loophole is closed, and supply chain adaptation is too slow to help in 2025. What remains is pricing power or margin compression. Most retailers will choose pricing power. Prices will rise 5-15% across most categories by end of 2025, with variation based on tariff rates, margin structure, and competitive dynamics.

This matters because Amazon isn't just a retailer—it's the market-clearing price mechanism for e-commerce. When Amazon prices rise, it signals that these price increases are economically necessary, not opportunistic. Other retailers quickly follow. Consumers see systematic price increases across their normal shopping patterns.

The policy question—whether tariffs are good policy—is separate from the pricing reality. Regardless of whether tariffs make strategic sense, they have concrete effects on prices consumers pay. Jassy is essentially saying: "Yes, you're about to feel this in your wallet."

Prepare accordingly. Make planned purchases now if possible. Monitor prices actively. Shift some purchases to retailers or categories seeing smaller increases. Adjust budget expectations for 2025. The tariff era isn't coming—it's here, and pricing is adjusting to match the new economic reality.

The inventory buffer that kept prices artificially low for six months is gone. What's coming next is the real tariff economy: higher prices, margin-compressed retailers, and consumers adapting their spending patterns to a less affordable online retail environment. That's what Jassy was really saying when he talked about tariffs "creeping into" pricing. The creep is becoming a flood.

Key Takeaways

- Amazon's pre-tariff inventory buffer has been completely depleted, forcing retailers to pass tariff costs to consumers

- Kiel Institute research confirms 96% of tariff costs are passed to consumers while only 4% are absorbed by exporters

- Trump's de minimis loophole closure eliminates another cost-reduction pathway for retailers and sellers

- Price increases will accelerate through 2025, with early modest increases (2-4%) ramping to 5-10% by year-end

- Third-party sellers face steeper pressure than Amazon's first-party business, leading to marketplace-specific price increases

- Electronics, textiles, and furniture face the highest tariff-driven price pressure; consumables face less

- Domestic sourcing and production shifting won't meaningfully reduce tariff impact until 2026-2027 at earliest

Related Articles

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

- Amazon's Buy for Me AI: The Controversy Shaking Retail [2025]

- How Donghai Became the Crystal Capital: China's $5.5B Livestream Empire [2025]

- Why Apple's Move Away From Titanium Was a Design Mistake [2025]

- 5 Website Income Streams to Start Earning Today [2025]

- US 25% Tariff on Nvidia H200 AI Chips to China [2025]

![How Trump's Tariffs Are Creeping Into Amazon Prices [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-trump-s-tariffs-are-creeping-into-amazon-prices-2025/image-1-1768923529918.jpg)