Introduction: The Design Problem Nobody's Talking About

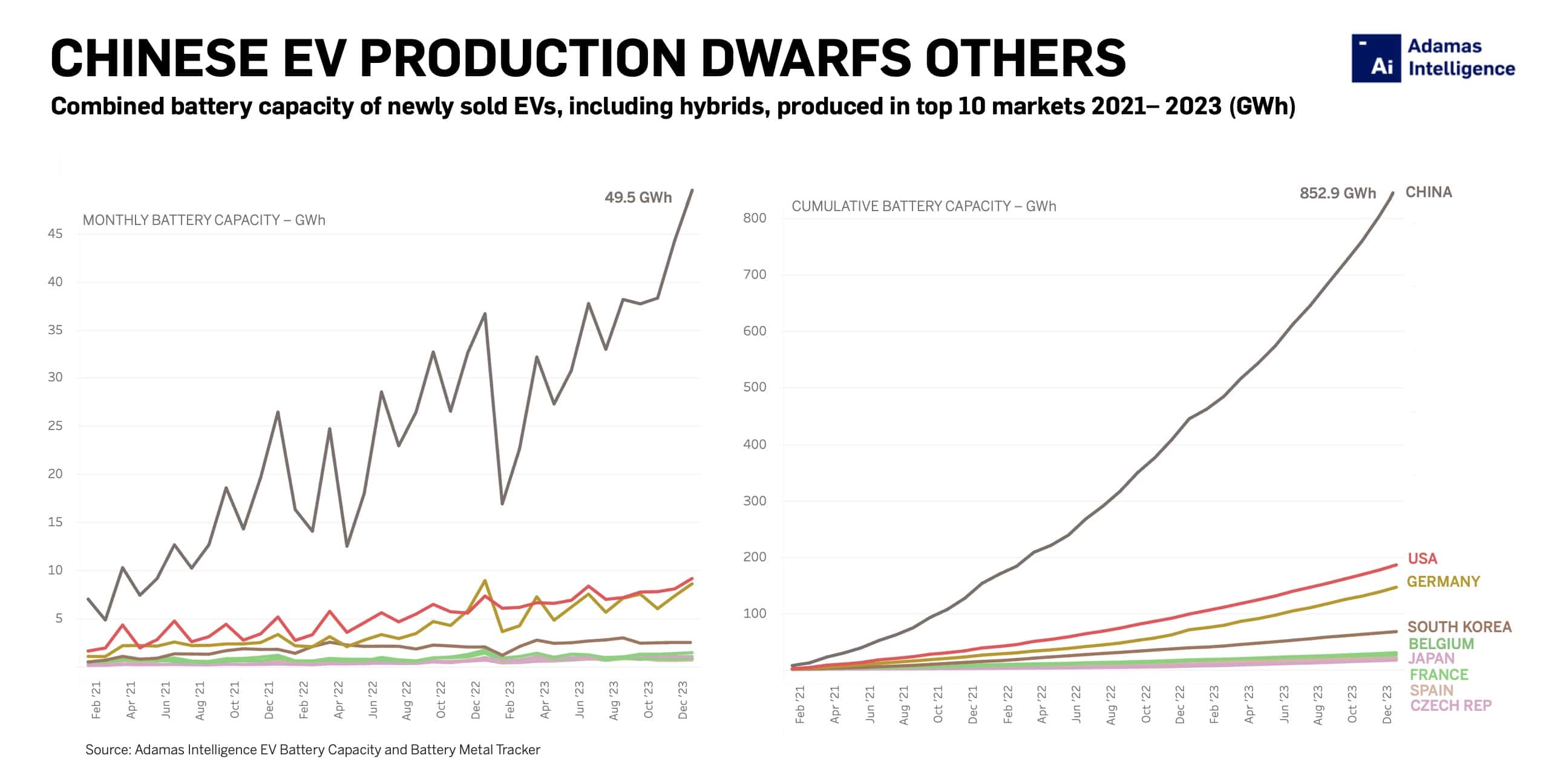

China's electric vehicle market is on fire. Last year, Chinese EV makers shipped more cars than the rest of the world combined. Chinese automakers like BYD, Li Auto, and NIO are crushing sales records, stealing market share from Tesla and legacy carmakers. The battery tech is world-class. The software integration puts Western cars to shame. The prices? Unbeatable.

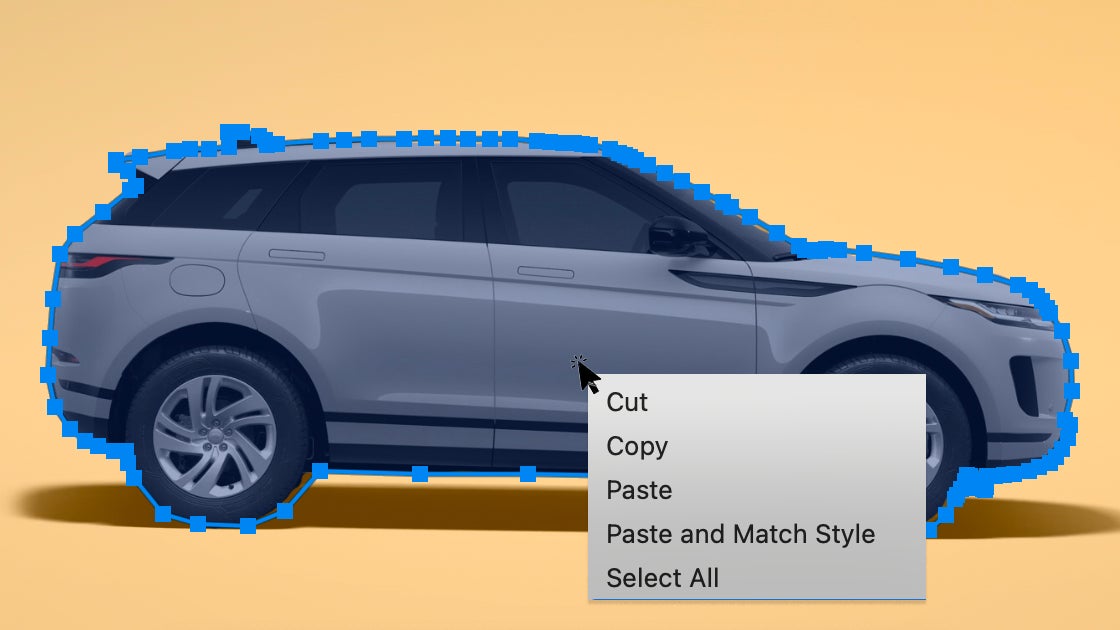

But walk through a Chinese parking lot and something feels off. You'll spot what looks like a Range Rover—except the badge says something else. Then another one. And another. These aren't licensed designs or official partnerships. They're blatant visual copies of one of the most recognizable SUV silhouettes on Earth.

This isn't just a design ethics problem. It's a symptom of something deeper: Chinese EV makers are winning on specs and price, but they're losing on the one thing that actually builds brand loyalty—original identity. They can make a better battery pack than Bosch. They can't seem to make a design that doesn't look like someone else's.

The irony is brutal. China's overtaken the West in EV manufacturing prowess. They've invested trillions into the technology. But instead of establishing themselves as design leaders, they're playing copycat. It's like finally beating the world in a sport you invented and then celebrating by copying someone else's victory dance.

This article digs into why this is happening, what it means for the global auto industry, and whether Chinese EV makers can actually break free from the design plagiarism trap before the market moves past them.

TL; DR

- Chinese dominance is real: BYD, NIO, and others lead in EV sales and battery innovation, but design originality lags behind

- Range Rover copying is widespread: Multiple Chinese manufacturers produce SUVs with nearly identical silhouettes to Land Rover's flagship vehicle

- It's not just ethics: Weak original design undermines brand differentiation in an increasingly crowded market

- Regulatory risk: IP lawsuits and trade friction could force design overhauls and market access restrictions

- The future depends on creativity: Chinese makers who establish distinct design languages will dominate the 2030s auto market

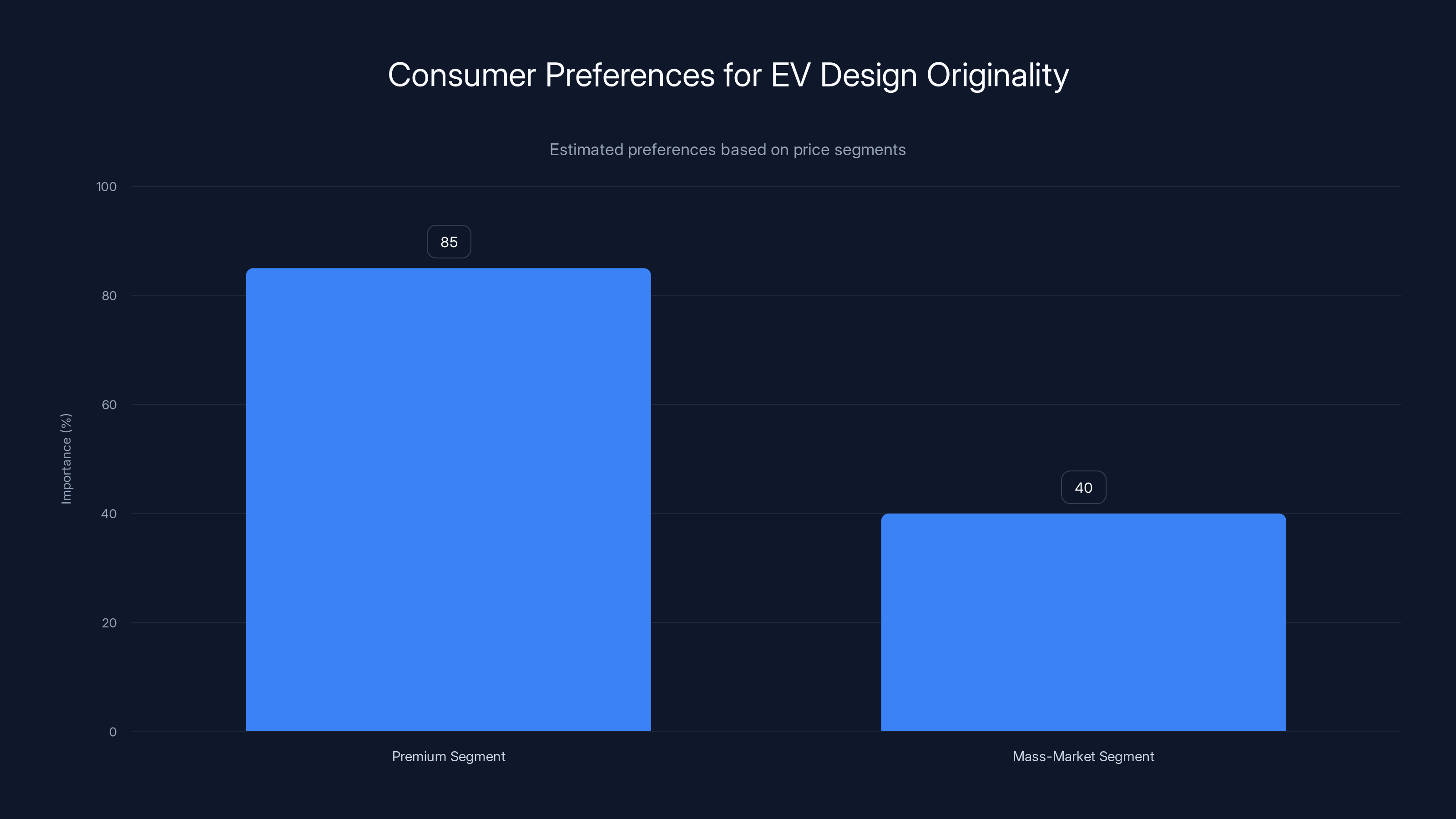

Estimated data suggests that design originality is significantly more important in the premium EV market segment compared to the mass-market segment.

The Scale of China's EV Dominance (And Why It's Hiding a Problem)

Here's the thing about Chinese EV stats: they're staggering, but they mask a critical vulnerability.

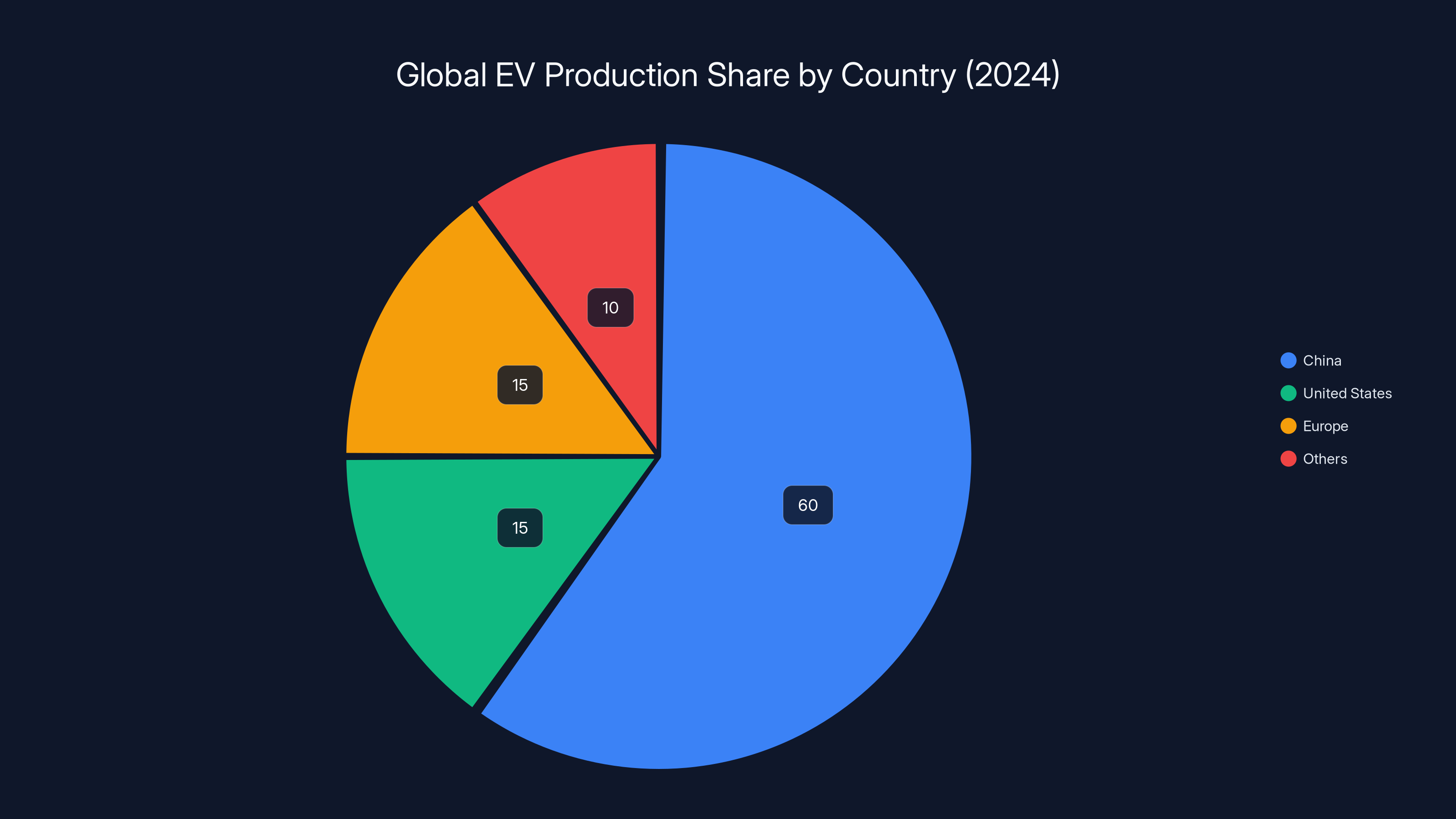

In 2024, China produced roughly 10 million electric vehicles—nearly 60% of global EV output. The International Energy Agency estimates that by 2030, China will account for over 50% of all EVs sold globally. That's not market share. That's industrial dominance.

BYD alone shipped more EVs than Tesla, Volkswagen, and BMW combined. Li Auto's SUVs command premium prices despite being relative newcomers. NIO, Xpeng, and others are expanding into Europe and Southeast Asia. The battery supply chain? Controlled by China. The rare earth mineral processing? Controlled by China. The manufacturing cost structure? Nobody in Detroit or Stuttgart can compete.

But here's what doesn't show up in those statistics: brand perception.

When a consumer sees a premium EV, what comes to mind? Tesla's minimalist futurism. Porsche's performance heritage. BMW's engineering precision. Now ask the same consumer to think of a premium Chinese EV brand without mentioning the company name.

They can't.

And when they look at the cars themselves, many don't see innovation. They see imitation. The Changan UNI-T looks suspiciously like a Range Rover. The Geely Geometry borrows heavily from established silhouettes. The Li Auto Mega uses proportions that echo larger SUVs you've seen before.

This matters because the EV market is shifting. Specs are commoditizing. Every new Chinese EV has a 350-mile range. Battery density is approaching parity. Charging networks are equalizing. When everything's technically similar, design becomes the differentiator. It's the thing that makes you buy one car over another when performance specs are identical.

China's problem: they're winning on everything except the thing that builds lasting brand value.

The Range Rover Problem: Why This Specific Vehicle?

Let's be specific. The Range Rover isn't a random target.

Land Rover's flagship SUV is the design equivalent of the iPhone—instantly recognizable, globally aspirational, and built on decades of heritage. The distinctive boxy silhouette with those rising belt lines, the square wheelarches, the overall proportions. It's burned into the collective consciousness. When people think "premium SUV," many think Range Rover before they think anything else.

That's exactly why it's so dangerous to copy it.

The visual similarity across Chinese EVs is striking:

-

The Changan UNI-T mirrors the Range Rover's overall stance and proportions so closely that at a glance, the differences feel cosmetic. The boxy shape, the muscular shoulders, the way the roof sits. The primary difference? The grille and headlight design.

-

The Geely Geometry borrows that same premium SUV silhouette that established vehicles use. The roof line, the side profile, the wheelbase relationship.

-

Even Li Auto's flagship Mega uses proportions and stances that echo premium SUVs you've seen in showrooms for decades.

Now, there's a defense here. Land Rover doesn't own the concept of a boxy SUV. Practicality dictates certain proportions. You can't make a large, spacious family SUV without creating similar profiles. The math of aerodynamics, interior space, and structural integrity points naturally toward certain shapes.

That's fair. That's also completely missing the point.

Yes, all large SUVs share fundamental proportions. But within those constraints, there's enormous room for visual differentiation. Tesla's Model X doesn't look like a Range Rover despite having similar dimensions. Neither does the Rivian R1S. Neither does BMW's iX. Even the electric Hummer EV, which is absurdly large, looks distinct. They all found unique visual languages within functional constraints.

Chinese makers had the same constraints. They made different choices.

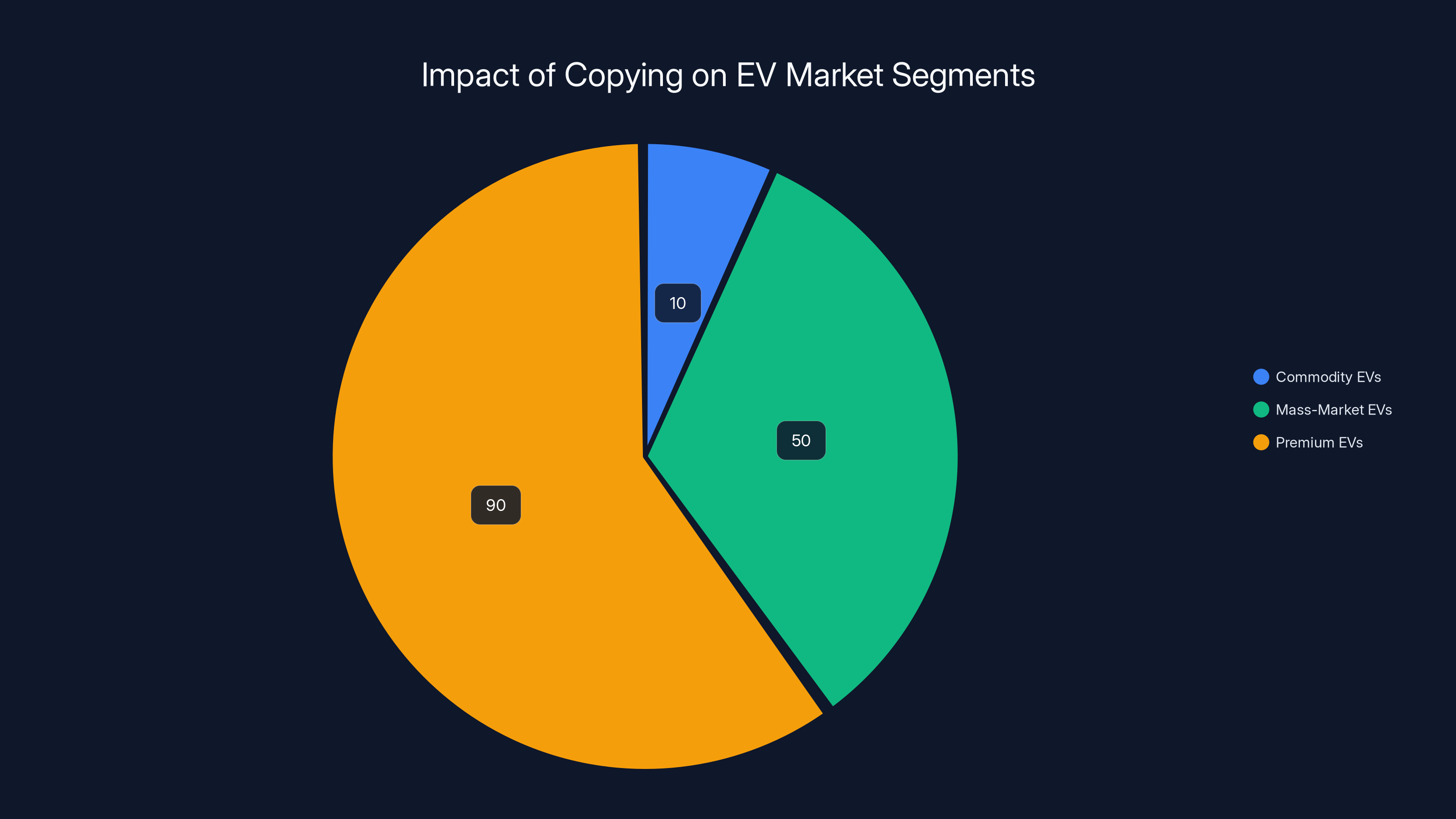

Estimated data shows that copying has minimal impact on Commodity EVs, moderate impact on Mass-Market EVs, and significant impact on Premium EVs. Design differentiation is crucial in higher segments.

The Deeper Issue: Chinese Design Culture vs. Western Design Heritage

Understanding why this is happening requires looking at how design works in China versus the West.

Western design culture—especially in the auto industry—is built on generations of heritage. Porsche's design has evolved over 70 years, but it's still recognizably Porsche from 1963. Mercedes has a visual language that's evolved but remains distinctly Mercedes. This heritage becomes a moat. Consumers trust it. They recognize it. They pay for it.

Chinese automotive design, by necessity, started from scratch. Geely didn't have 50 years of design tradition. BYD started as a battery company. NIO was founded in 2014. They didn't have time to build design heritage through iteration. Instead, they faced enormous pressure to deliver cars quickly, to hit price points, to capture market share.

When you're moving fast and the pressure is existential, you copy. It's faster. It's lower risk. Consumers recognize the silhouette, so it sells. The internal logic is sound: why invest in original design when proven designs already work?

This logic works until it doesn't.

The problem compounds over time:

Each company that copies the same successful design makes original design less valuable for future competitors. Why be the first Chinese maker with a truly original design language when you can be the fifth maker with a proven design that sells? The incentive structure actually punishes originality.

Meanwhile, Western and Japanese makers had the opposite pressure. They invested heavily in design because they needed brand differentiation to justify premium pricing. That investment created cultural institutions around design. Porsche employs hundreds of designers. Mercedes has entire teams focused on design evolution. These aren't departments—they're entire design cultures.

China had design departments. It didn't have design cultures.

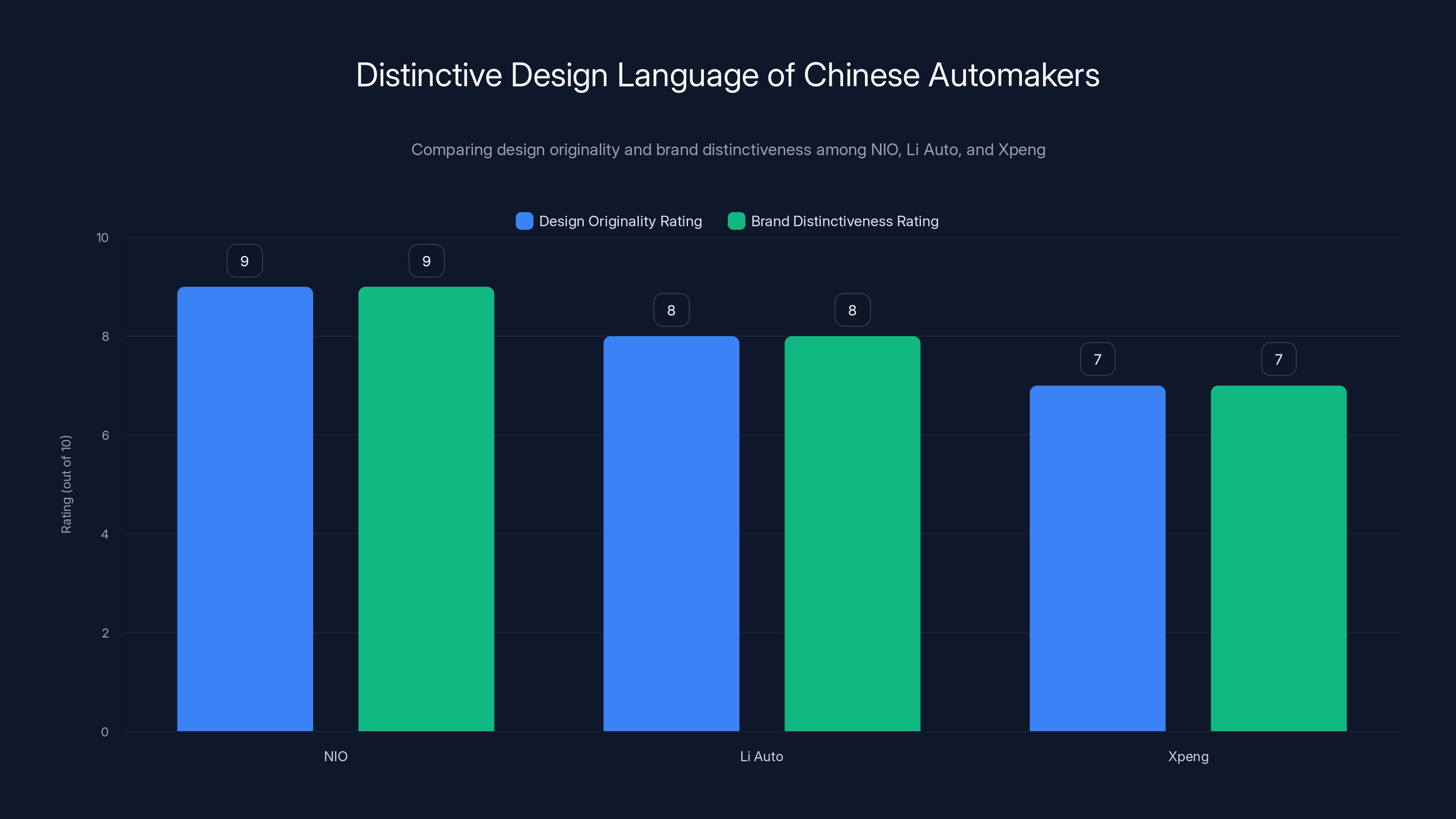

That's changing now, but it's changing slowly. NIO is starting to establish a visual identity. Xpeng is pushing toward more distinctive proportions. But they're fighting against years of market expectations and internal organizational inertia.

The Business Logic Behind Design Copying (And Why It's Rational)

Before condemning Chinese makers for copying, it's worth understanding the incentive structure that makes copying rational.

Let's talk economics. Design innovation costs money. Serious money. You need to hire world-class designers. You need multiple iterations, testing, consumer research. You need to build manufacturing processes optimized for your new design. You need to manage risk—original designs might not sell.

A proven design? It's already de-risked. Consumers recognize it. Manufacturers know how to build it. Supply chains are optimized. The regulatory path is clearer.

Consider the numbers:

Land Rover spent decades and hundreds of millions perfecting the Range Rover's proportions. They tested consumer preferences across markets. They optimized for manufacturability. They built a heritage narrative around the design.

A Chinese maker can take those same proportions, tweak them slightly for IP avoidance, and launch a new vehicle in 18 months at half the cost. The risk is lower. The time to market is faster. The margins can be higher because R&D costs were essentially zero.

From a pure business perspective, copying is rational. It's value theft, sure. But it's rational.

The problem emerges at scale. When you're one of five Chinese makers copying Range Rovers, the differentiation evaporates. Consumers can't tell your SUV from competitors' SUVs. They're all vaguely Range Rover-ish. Now you're competing on price and features instead of identity. And on those axes, you're competing against everyone equally.

This creates a race to the bottom:

If every maker uses similar design languages, the only way to differentiate is through specs (bigger battery, faster charging, lower price). This compresses margins across the industry. It shifts competition to areas where Chinese manufacturers still have advantages (cost structure, supply chain integration), but those advantages are temporary. As other regions build manufacturing capacity, those edges erode.

The makers who will dominate 2030 aren't the ones who copied best. They're the ones who built distinctive design languages that consumers choose because they want that specific brand, not because it's the cheapest or most powerful option.

China's chasing a game where the winner is already defined. They should be building a new game entirely.

IP Law, Trade Friction, and the Long-Term Risk

Here's where this moves beyond design ethics into actual business risk.

Land Rover (owned by Tata Motors) has massive financial incentive to protect the Range Rover design. They're not going to sue every Chinese maker who builds a boxy SUV—the litigation cost alone would be enormous, and proving design infringement is legally complex.

But as Chinese EV makers export more cars to Western markets, as their sales grow, as the IP violations become more obvious, the calculus changes. Land Rover might decide that defending IP is worth the cost. They have the legal resources. They have precedent. They have governments that support IP enforcement.

Consider what a successful lawsuit could mean:

A Chinese maker might face forced design overhauls, export restrictions, or market access bans in critical regions. They might face fines or licensing fees. They might get excluded from Western markets during the critical growth phase of the EV transition.

Even the threat of litigation creates risks. Regulatory uncertainty makes capital allocation harder. Insurance costs rise. Investor confidence wobbles. Supply chain partners get nervous about supporting flagged products.

The trade friction risk is even broader. Western governments are increasingly protective of IP. The U.S. has tariff mechanisms specifically designed to penalize IP violations. Europe's trade negotiations with China increasingly center on IP enforcement. If Chinese EV makers become the face of design plagiarism, it becomes a political issue, not just a legal one.

The irony is brutal: China has become incredibly protective of its own IP in other sectors. They've invested billions in building homegrown tech companies and protecting their innovations. But in automotive design, they're openly copying. As their bargaining power in global trade grows, this hypocrisy becomes harder to defend.

Makers who've built original designs have regulatory clarity. Makers who've copied are playing with house money that could evaporate.

China dominates global EV production with 60% share in 2024, highlighting its industrial dominance but also a potential vulnerability in brand perception. Estimated data.

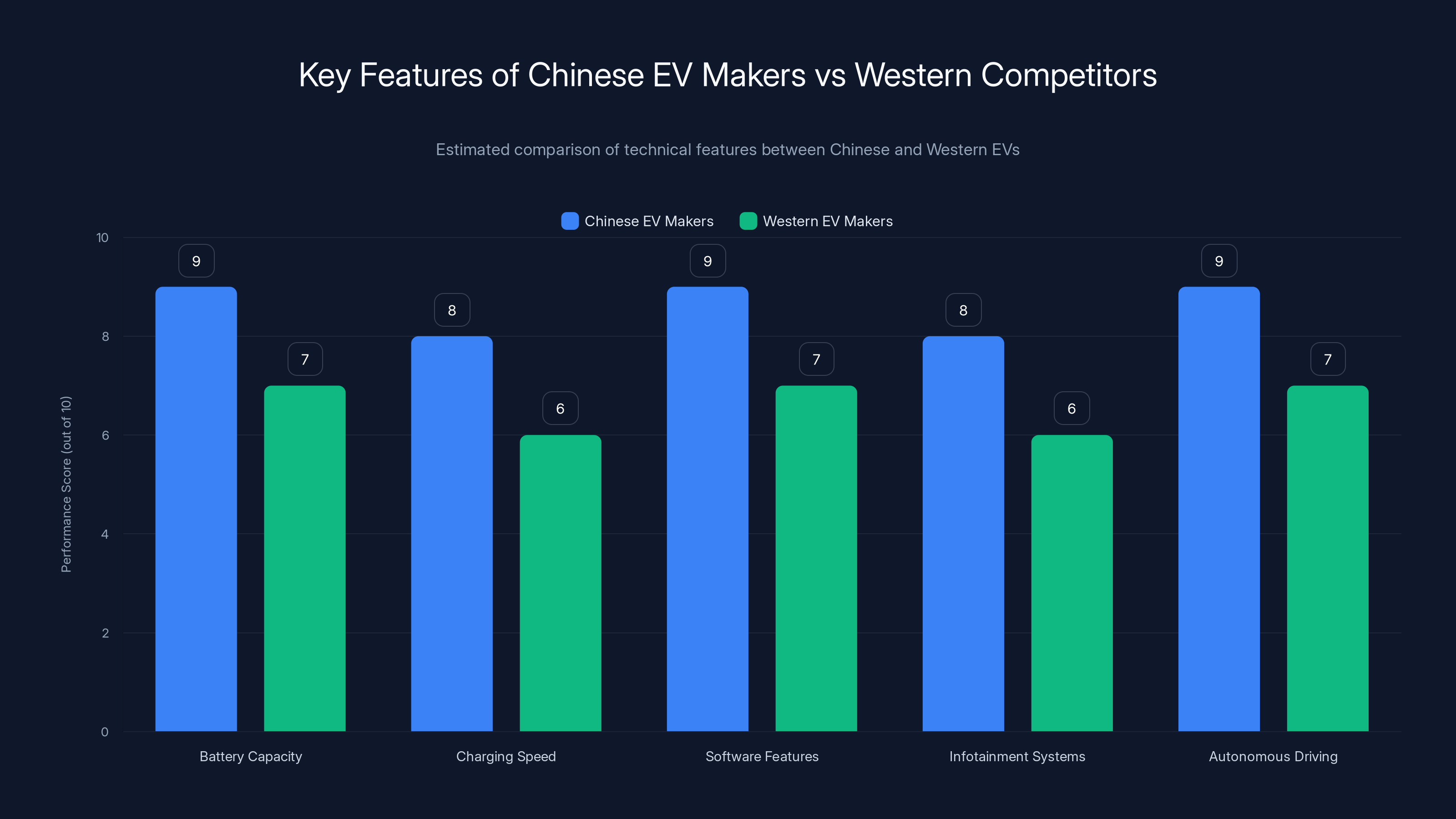

The Features-First Philosophy: Where This Started

To understand why copying became normalized, you need to look at how Chinese EV makers prioritized innovation.

They made a strategic choice: dominate on features and performance that consumers can measure. Battery capacity, charging speed, software features, infotainment systems, autonomous driving capabilities. These are quantifiable. These are easily comparable. These are the things tech-forward consumers care about.

Design is different. Design is subjective. Design is hard to quantify. Design takes time to build cultural relevance. Design requires investment in brand narrative. For makers trying to launch fast and build market share quickly, design felt like a luxury.

So they focused on what they could measure. They built the best batteries. They built the fastest charging networks. They integrated software that made Western cars look primitive. By every technical metric, Chinese EV makers became superior to Western competition.

But they left design as an afterthought. And now that their tech is competitive, design is the thing holding them back.

This is a classic emerging-market pattern. Japan did the same thing in the 1960s and 70s. Korean makers did it in the 90s and 2000s. You compete on specs until your specs are better. Then you realize specs alone don't build the emotional attachment that creates brand value. By then, you've reinforced narratives about your brand that take decades to overcome.

Sony eventually built a design reputation. Samsung did too. But it took them 20 years after they became technically superior to Western competitors.

China's trying to compress that timeline. But you can't compress cultural perception. You can only build it intentionally, consistently, over time.

The Designers Who Tried to Innovate (And What Happened)

It's not like Chinese makers haven't tried to build original design languages.

NIO hired Kris Wu, a designer from BMW, to lead their design direction. NIO's recent vehicles show distinctive proportions, bold styling choices, and a coherent visual language. The NIO ET6 looks like nothing else on the road. It's not copying Range Rovers or anyone else. It's distinctly NIO.

So why isn't every Chinese maker doing this?

Because original design is slower. The ET6 took years in development. It required multiple iterations, design studio debates, risk acceptance. And there's no guarantee consumers will prefer it. They might not. The market might reject it. Meanwhile, competitors shipping copied designs are getting market share and cash flow faster.

When you're in high-growth mode, when investors are pushing for quarterly improvements, when shareholders want to see revenue growth every quarter, taking a risk on original design feels irresponsible. It's easier to ship a car you know will sell, even if it looks like something else.

The institutional pressure is real:

Chinese automakers operate under different governance structures than Western makers. They often have government or state backing. Government partners care about units sold, jobs created, and revenue generated. Design reputation is a long-term asset that doesn't show up on quarterly balance sheets.

Western makers have investor governance that also pushes for short-term results, but they have brand heritage that protects them during innovation phases. They can say, "We're investing in design because we're Mercedes," and investors accept it. Chinese makers saying "We're investing in design because we want to be like Mercedes" doesn't carry the same weight.

NIO's doing it anyway. That's why NIO might actually become something special. They accepted the short-term risk for long-term brand value. That decision might be the thing that separates them from makers still copying a decade from now.

The Market Segmentation Problem: Why Copying Affects Everyone Differently

Here's a nuance that gets missed: copying isn't impacting all Chinese makers equally.

Let's split the market into segments:

Segment 1: Commodity EVs (

In this segment, copying doesn't matter much. Consumers buying a $15,000 EV care about range, charging speed, and price. They don't care whether the design language is original. The market leader in this segment won't be determined by design differentiation. It'll be determined by cost structure and features. Chinese makers dominate here, and copying poses minimal risk because design isn't the purchase driver.

Segment 2: Mass-Market EVs (

This is where copying starts to hurt. Consumers at this price point have choices. They might buy a Chinese EV or a Tesla or a VW or an equivalently priced EV from five other makers. Design becomes a tiebreaker. When multiple makers offer similar specs at similar prices, the one with distinctive design wins. Chinese makers copying established designs lose this differentiation advantage.

Segment 3: Premium EVs ($45,000+)

Copying is toxic here. Premium consumers are explicitly buying design heritage and brand identity. They're paying for the Range Rover name, the Tesla cachet, the Porsche heritage. When a Chinese maker copies that heritage, they're saying, "We don't have our own story." Premium buyers don't want that story. They want exclusivity and originality. Copying alienates exactly the customers you need to build profitable margins.

The consequence is that Chinese makers who rely on copying get trapped in the mass-market segment. They can compete on specs and price, but they can't move upmarket where the real margins are. They hit a ceiling.

Makers who invest in original design, like NIO, are explicitly targeting premium segments. They're accepting lower volumes for higher margins. They're building brand identity that supports premium pricing. Long-term, that's the more defensible business model.

But it requires patience. It requires accepting slower growth in the short term. It requires board members and government partners who believe in long-term value over quarterly results.

Many Chinese makers don't have that luxury.

NIO leads in both design originality and brand distinctiveness, followed closely by Li Auto and Xpeng. Estimated data based on narrative insights.

Consumer Perception and the "Not Real" Stigma

There's something psychological happening in consumer perception that copying accelerates.

When a consumer sees a Chinese EV that closely mirrors a Range Rover design, they don't think, "That's a smart borrowing of proven proportions." They think, "That's a knock-off." It creates an association with inauthenticity. It suggests the maker couldn't innovate, so they plagiarized.

That perception sticks even after the car is purchased. Owner satisfaction surveys show that consumers feel less attachment to vehicles they perceive as copies. They're less likely to recommend them. They're less likely to trade up to the maker's next vehicle. They're less likely to become brand advocates.

Brand advocates matter. They're the reason Tesla owners are religion-level enthusiasts. They're the reason Mercedes owners accept $2,000 service costs without flinching. They're the reason Apple has a cult-like following despite not having the cheapest or most technically powerful products.

Copying makes it impossible to build that devotion. It signals that you don't believe in yourself enough to define yourself.

This perception problem is compounding:

As Western media increasingly covers Chinese design copying, the narrative gets baked in. "Chinese makers copy designs" becomes the story. Each new example reinforces it. That's a PR problem that no amount of technical innovation can solve. You can't tech your way out of the perception that you're not original.

Meanwhile, makers investing in original design get the opposite narrative. "Chinese maker boldly challenges design conventions." "New brand brings fresh perspective to EV design." "This startup is redefining how EVs look." These stories sell cars. They build brand value. They create consumer preference.

It's not just about the car. It's about what the car says about the company.

Geopolitical Implications: Design as a Trade Leverage Point

Design copying is becoming a geopolitical issue, even if it doesn't feel that way yet.

China is increasingly capable of competing with Western automakers across every axis: price, performance, software, manufacturing efficiency. Western governments are watching this anxiously. The EV transition was supposed to give Western makers a reset—a chance to compete on equal footing in a new category.

Instead, China's winning.

One of the few vulnerabilities Western governments can point to is intellectual property violation. They can say, "China's success is built on stealing Western designs." That's a narrative Western governments are starting to embrace.

If that narrative gains traction, it becomes a trade issue. It becomes a regulatory issue. It becomes a geopolitical leverage point. Suddenly, it's not just Land Rover versus Chinese makers. It's Western governments restricting Chinese EV imports based on IP violations.

WTO disputes over design IP are already brewing. If China is perceived as a serial design copier, it weakens China's position in broader trade negotiations.

Conversely, if Chinese makers establish a reputation for original design, it removes this vulnerability. It becomes harder to argue that Chinese success is based on theft when Chinese makers are innovating visually.

This might sound abstract, but it has real business consequences. A 25% tariff on Chinese EV imports based on IP violation concerns would devastate Chinese makers. A ban on certain Chinese EV brands in Western markets would cut off growth avenues. A regulatory requirement that imported vehicles have "certified original design" would exclude many Chinese competitors.

These aren't hypothetical. They're actively being discussed in Western policy circles. And they're accelerated by design copying being high-profile.

From a pure strategic standpoint, Chinese makers should view original design as essential risk management. It's not just brand building. It's geopolitical self-defense.

What Original Design Actually Looks Like: The Counter-Examples

To be fair to Chinese makers, some are actually building distinctive design languages. And they're proving that it's possible.

NIO is the clearest example. The ET6, the ET7, the newer models—they have a coherent visual language. The proportions are distinctive. The detailing is refined. You can identify an NIO from a distance. It doesn't look like a Range Rover. It doesn't look like anything Western. It looks like NIO.

That design language didn't happen by accident. It required hiring top talent from Western design studios, investing in long design cycles, empowering designers to take risks. NIO's CEO and board had to accept that design innovation wouldn't show up in 2024 quarterly results. They accepted slower growth in the short term for brand building in the long term.

The bet is paying off. NIO's premium positioning is increasingly defensible. Their margins are higher. Their consumers are more loyal. Their brand story is distinctive.

Li Auto is doing something different but equally original. Their vehicles have a utilitarian honesty that's distinctly theirs. The proportions favor function over fashion. The styling is bold and distinctive. You might not like it (design is subjective), but you know it's a Li Auto from across the parking lot.

That visual distinctiveness is building brand equity. Consumers who buy Li Auto are choosing that specific brand, not the cheapest option that happens to offer similar specs.

Xpeng is younger, but their design direction is starting to cohere. Their vehicles have more daring proportions and styling cues than most Chinese competitors. They're taking design risks that established makers avoid.

These makers prove that original design is achievable for Chinese manufacturers. It requires investment. It requires patience. It requires leadership that believes in long-term brand building. But it's absolutely possible.

The makers still copying have a choice. They can continue optimizing the copied formula, competing on specs and price until the market gets commoditized and margins collapse. Or they can invest in original design now, accept short-term risk, and position themselves as design leaders for the next decade.

The decision will define which Chinese makers are still relevant in 2035.

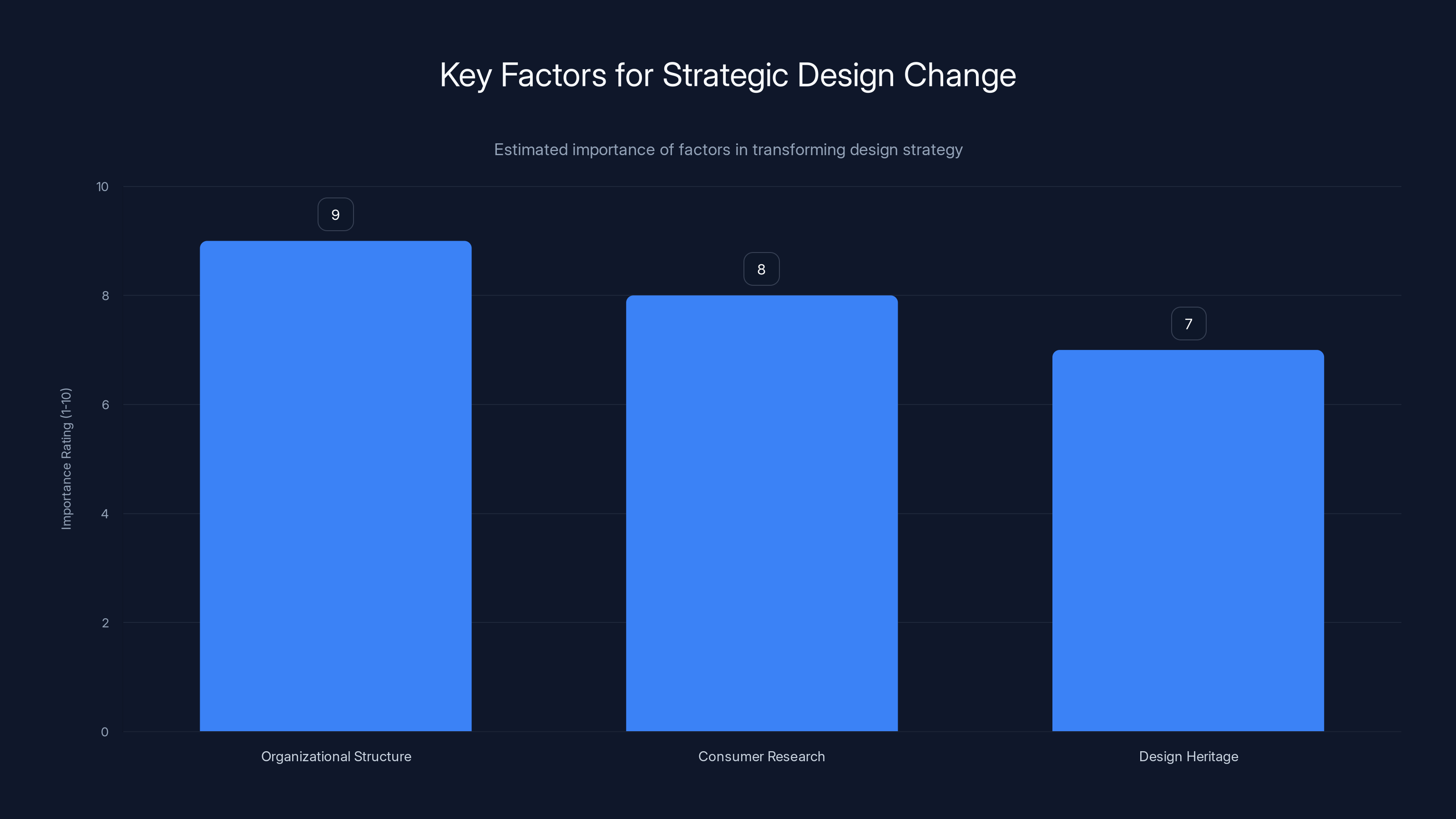

Organizational structure change is the most critical factor in transforming design strategy, followed by consumer research and design heritage. Estimated data.

The Path Forward: What Change Actually Looks Like

Breaking the copying cycle requires intentional strategic change. It's not enough to say, "We're going to design original cars." You need to build systems that make original design possible.

First: organizational structure change.

Design needs to become a core strategic function, not an afterthought squeezed between engineering and marketing. That means hiring world-class design talent. Not just good designers—the best. That means paying them premium salaries. That means giving them authority over product decisions, not just styling tweaks.

Luxury Western makers do this. Porsche's head of design reports directly to the CEO. Design decisions can overrule engineering preferences. That level of organizational commitment signals that design actually matters.

Most Chinese makers haven't made that commitment. Design is a department. It's not a strategic function.

Second: consumer research investment.

Design needs to be informed by actual consumer preferences, not designer intuition or copied precedent. That means conducting design research across markets. What do consumers in Europe prefer versus China versus Southeast Asia? What visual cues trigger premium perception? What design details create emotional attachment?

This research is expensive and slow. It doesn't create quarterly results. But it's the foundation of distinctive design.

Third: design heritage building.

Once you've established a visual direction, you need to evolve it consistently across vehicles. That's how brands like Porsche built recognition—not by making every car identical, but by maintaining visual coherence while evolving the language. The new 911 looks similar to 911s from 20 years ago, but it's clearly evolved.

Chinese makers need to commit to multi-year design language strategies. They need to say, "This is what we're building toward," and then actually build toward it consistently. That requires leadership stability and strategic patience.

Fourth: investment in design culture.

Design culture is built through case studies, design review processes, design-focused communication, hiring practices, and celebrating design excellence. It means talking publicly about design decisions. It means publishing design manifestos. It means hiring designers who care about solving design problems, not just following brief specifications.

Fifth: long-term financial commitment.

All of this costs money. Design studios. Design talent. Design research. Design iteration. A $100M annual design investment might generate zero incremental revenue in year one. It generates tremendous value in year three and four, but only if you commit to the long-term investment.

Chinese makers with government backing can make this commitment. State-owned enterprises can prioritize long-term brand building over quarterly returns. They have an advantage here that private companies lack.

But most haven't seized it.

The Competitive Advantage in the 2030s: Why Design Matters More Than Specs

This matters for a simple reason: EV specs are converging.

In 2025, differentiation still comes from battery technology, charging speed, and autonomous driving capabilities. Those are hard to copy. They require continuous R&D investment. By 2030, those advantages will erode. Every maker will have 350+ mile range. Every maker will have 10-minute charging. Every maker will have Level 3+ autonomous capabilities.

When specs are equivalent, what drives purchase decisions? Design. Brand identity. Emotional connection. The car that makes you feel something.

That's not a prediction. It's observable in existing markets. Among similarly specced premium EVs, the one with distinctive design wins. Consumers choose Tesla Cybertruck despite (or because of) its unconventional design because it makes a statement. Porsche Taycan buyers choose it for design heritage, not because it outperforms competitors.

Brand identity will be the moat in the 2030s EV market. And you can't build that moat by copying Range Rovers. You build it by establishing your own design language and evolving it consistently over years.

Chinese makers that invest in original design now will dominate the 2030s. Makers that continue copying will be trapped in the commodity segment, competing on price with zero pricing power.

That's not moral judgment. That's market prediction.

Western Automakers: The Counterattack

While Chinese makers are copying, Western automakers are finally waking up to the EV opportunity.

BMW's iX lineup is genuinely distinctive. Audi's e-tron vehicles have cohesive visual language. Porsche's Taycan proved that design heritage transfers to EVs. Mercedes is establishing a distinctive EV design direction.

These makers have something Chinese makers don't: decades of design heritage to build upon. They're not starting from scratch. They're evolving established visual languages into the EV era.

That's an enormous advantage. Consumers see a new BMW EV and think, "That's BMW's electric future." When consumers see a Chinese EV, they might think, "Is that a Range Rover copy?"

The conversation is fundamentally different.

Western makers are also investing in premium positioning for EVs. Tesla proved that EVs could command premium pricing. Western luxury makers are doubling down on that insight. Their EV strategy isn't to compete on price. It's to establish EVs as the premium choice.

Chinese makers who continue chasing volume through copying will find that Western makers have already claimed premium segments through design leadership. Chinese makers will be left fighting for lower-margin volume.

Chinese EV makers have focused on excelling in measurable technical features, often surpassing Western competitors. Estimated data.

The Regulatory Awakening: IP Protection Gets Serious

One more pressure is building that copying makers haven't fully grasped: regulatory crackdowns on design IP.

Western governments are increasingly serious about protecting intellectual property as a matter of national interest. Design IP is starting to show up in trade negotiations. U.S. trade representatives are explicitly calling out design plagiarism in bilateral discussions with China.

The EU has similar conversations happening. Japan and South Korea are advocating for stricter design IP enforcement.

What does this mean practically? It could mean:

- Tariffs on Chinese vehicles with disputed design IP

- Market access restrictions for flagged brands

- Mandatory design modification for export

- Licensing fees or royalties on derived designs

- Regional restrictions on sales

None of these are theoretical. They're actively being debated in government circles. If even one major market implements strict design IP enforcement, Chinese makers with questionable design origins will face barriers.

Makers who invested in original design have zero exposure to this risk. They're actually benefiting from it—original design becomes a regulatory advantage, a signal of legitimacy.

From a business continuity standpoint, regulatory risk should be pushing Chinese makers toward original design. It's not. Most are hoping the copying issue stays below the political threshold.

That bet might not pay off.

The Innovation Speed Advantage: Why Fast Doesn't Beat Original

Chinese makers like to argue that copying enables faster innovation cycles. Why spend three years designing a unique interior when proven designs exist?

That's true in the short term. But it creates a trap.

Innovation has two components: speed and direction. Chinese makers have mastered speed. They can iterate rapidly, add features, improve specs faster than Western makers.

But they're iterating on directions set by someone else. They're optimizing existing solutions instead of exploring new ones.

Over decades, that disadvantage compounds. Direction matters more than speed. A slowly improving unique vehicle beats a rapidly improving copy every single time.

Tesla didn't win by iterating faster than legacy makers. Tesla won by going in a different direction. A direction nobody else was exploring. That direction advantage mattered more than execution speed.

Chinese makers having superior execution speed is valuable. But only if they're executing on a strategy that's directionally different. If they're just copying faster, they're losing the directional advantage that matters long-term.

The Path Chinese Makers Actually Need to Take

Here's what needs to happen for Chinese EV makers to escape the copying trap:

Investment in design: Treat design as a core strategic function. Hire the best designers globally. Pay them competitively. Give them authority. Commit to long-term design language development. This needs to come from board level, not from marketing departments.

Cultural change: Shift from "fastest to market" to "most distinctive to market." That doesn't mean slowing down product cycles. It means investing parallel design work that explores distinctive directions.

Consumer research: Understand what visual cues and design languages resonate with different markets. Build design direction informed by actual consumer preferences, not by copying competitors.

Patience: Accept that original design creates short-term risk. Expect lower initial sales on new design languages. Believe that premium positioning and brand equity pay off over 5-10 years, not quarters.

Bold bets: Stop making conservative design choices. Take risks. Propose proportions that feel unconventional. Let designers explore directions that don't look like everything else.

Heritage building: Evolve design language consistently. Create visual coherence across the lineup. Make the design language distinctive enough that consumers recognize your vehicles from a distance.

Premium positioning: Use original design to enable premium pricing. Don't compete on specs against other Chinese makers. Compete on distinctiveness and brand identity.

NIO is doing most of this. Li Auto is doing some. Others are barely starting. That variance will define the winners and losers of the 2030s.

The Global Market Implications: What This Means Beyond China

The Range Rover copying problem isn't isolated to China. It has implications for global automotive competition.

If Chinese makers get trapped in commodity segments by failing to build distinctive design, Western makers win. They'll maintain premium segments, brand heritage, and pricing power. Chinese makers will have scale but low margins. That's a suboptimal outcome for global competition. The market becomes less competitive.

If Chinese makers break through by establishing distinctive design leadership, Western makers face real competition. They have to earn premium positioning through design and innovation, not through heritage alone. Competition intensifies. Innovation accelerates. Consumers benefit.

From a global market perspective, the world is better off if Chinese makers figure out design. It makes Western makers work harder. It makes the entire industry more innovative.

But that requires Chinese makers making the right strategic bets now.

What's at Stake: The Long View

Design copying seems like a minor issue. It's not. It reflects a fundamental question: can Chinese automakers compete on brand identity, or will they always be the cheaper alternative?

Brand identity compounds over decades. The decisions Chinese makers make in 2025 will determine whether they're category leaders or commodity suppliers in 2040.

NIO's betting on distinctive design. They're accepting lower volumes and higher investment. They're betting that consumers will pay for originality.

Li Auto is carving out a distinctive niche with bold proportions and honest design.

Xpeng is starting to establish a design direction.

Hundreds of other Chinese makers are continuing to copy. They're chasing quarterly growth. They're hitting sales targets. They're not thinking about 2040.

One of these paths creates a sustainable competitive advantage. One creates a commodity business. By 2030, it'll be clear which Chinese makers chose which path.

The copies will be gone. The makers who innovated will be thriving.

Conclusion: Breaking the Cycle Requires Belief in Yourself

China's dominance in EV manufacturing is real. It's not hyperbole. Chinese makers have superior batteries, superior software integration, superior manufacturing efficiency, and superior cost structures. They're genuinely better at building electric cars from a technical standpoint.

But they're trapped by a design problem they created for themselves.

The irony is brutal: they finally have the resources and capability to compete globally, and they're undermining themselves by copying design. They're like a boxer who's finally become faster and stronger than his opponents, and he's responding by mimicking his competitor's fighting style instead of using his own advantages.

Breaking the cycle requires belief in your own originality. It requires the confidence to say, "We're good enough to design our own distinctive vehicle. We don't need to copy Range Rovers." It requires the organizational courage to invest in design when Wall Street would rather see quarterly growth.

NIO's made that bet. In five years, we'll know if it was right. If it was, other Chinese makers will scramble to do the same. If it wasn't, Chinese makers will double down on copying.

The market will decide. But the decision should be clear: original design builds lasting brand value. Copying builds temporary market share.

China's choosing between those futures right now. The decision doesn't feel urgent because copying works short-term. But by 2030, the cost of that decision will be obvious.

Here's to hoping Chinese makers figure it out. Because a world where they do is a world with genuinely distinctive automotive options. A world where they don't is a world where Western makers own the premium segments forever.

Neither outcome is ideal. But one has way more growth potential than the other.

FAQ

Why do Chinese EV makers copy designs like the Range Rover?

Chinese manufacturers copy established designs because it's faster and lower-risk than developing original designs. Proven proportions sell immediately, and consumers recognize them. Developing truly original design languages requires years of investment, consumer research, and cultural institutional support—something Western makers built over decades. In high-growth, high-pressure markets, copying is the rational economic choice short-term, even though it undermines long-term brand value.

Is design copying legally problematic for Chinese EV makers?

Design copyright and trademark law varies by jurisdiction, but yes, blatant design copying can expose manufacturers to IP litigation. Land Rover could potentially sue for design infringement, and increased geopolitical trade friction around IP enforcement means Chinese makers face growing regulatory risk. Beyond litigation, being perceived as design copycats creates regulatory barriers, tariff exposure, and market access restrictions in Western countries that prioritize IP protection.

Do consumers actually care whether an EV design is original?

Consumers care deeply, especially in premium segments. At the

Which Chinese EV makers have distinctive design languages?

NIO is the clearest example, with intentional investments in original proportions and a cohesive visual identity across their lineup. Li Auto has distinctive utilitarian styling and bold proportions. Xpeng is developing a more daring design direction. These makers invested significantly in design culture and talent, positioning themselves in premium segments where original design commands pricing power. Most other Chinese makers are still competing primarily on specs and price.

How does design copying affect Chinese makers' international expansion?

Design copying significantly hampers international expansion. Western markets increasingly perceive Chinese design copying as inauthentic and face regulatory protections around IP. Premium consumers in Europe and North America won't accept vehicles they see as copied designs—brand authenticity matters more to Western consumers. Chinese makers with distinctive designs (like NIO) expand internationally more successfully than those relying on copied proportions. The perception problem creates barriers to market entry that technical superiority can't overcome.

What's the long-term competitive impact of design copying?

Long-term, design copying traps Chinese makers in commodity segments. When all competitors offer similar copied designs with similar specs at similar prices, competition becomes purely price-based, compressing margins industry-wide. Makers who invest in original design build brand moats that enable premium positioning and higher margins. By 2030, when technical specs fully converge across all EV makers, design and brand identity will be the primary differentiator. Chinese makers who haven't built distinctive design by then will be commoditized.

Can Chinese makers develop original design quickly enough to compete in 2030?

It's possible but challenging. Design language development typically takes 3-5 years minimum, and building consumer perception around design takes longer. Makers like NIO proved it's achievable with sufficient investment and organizational commitment. However, most Chinese makers haven't made the necessary strategic commitments. Makers starting now could establish distinctive design by 2028-2030, but they'd be entering premium segments after Western makers already established leadership. First-mover advantage in original design matters significantly.

Why haven't Chinese governments required original design standards?

Government-backed Chinese makers prioritize near-term economic metrics like units sold and revenue generated. Design reputation is a long-term asset that doesn't improve quarterly earnings reports. Additionally, copying leverages Western design IP to enable faster launches with lower investment—something economically rational from a short-term capital efficiency standpoint. Change requires government policy that values long-term brand building over quarterly growth, which hasn't been institutionalized at the policy level in China's automotive industry.

What would happen if Western makers prioritized design IP enforcement?

If Land Rover sued Chinese makers for design infringement, or if Western governments imposed IP-based tariffs on flagged vehicles, copying makers would face forced design overhauls, market access restrictions, or export bans. This would make copying strategically catastrophic, accelerating the shift toward original design investment. Paradoxically, regulatory enforcement might actually force the design innovation that markets haven't yet incentivized.

Will copying eventually stop as markets mature?

Yes, but it's happening slowly. As Chinese EV makers accumulate capital and international ambitions, the costs of being perceived as copycats grow. Investors and premium consumers increasingly expect original design from established players. By the late 2020s, copying will become a significant competitive liability rather than a neutral issue. Makers still relying on it then will face market transition challenges. Early movers investing in original design now are positioning themselves advantageously for that transition.

Final Thoughts on Where Chinese EVs Go From Here

China's transformed the auto industry faster than anyone predicted. From zero to industry dominance in less than 15 years. That's extraordinary. It's real. It's reshaping global competition.

But extraordinary achievement on technical metrics doesn't guarantee market dominance. Dominance requires brand identity. Requires consumer preference built on more than specs. Requires differentiation that persists even as competitors copy your specs.

Design is how you build that differentiation.

The Range Rover copying problem is a symptom, not the disease. The disease is the belief that technical excellence is enough. It's not. Never has been. Never will be.

NIO gets this. Li Auto is getting there. Hundreds of other makers are still waiting.

The ones that figure it out in 2025-2026 will dominate 2035-2040. The ones that wait will be fighting for survival. That's not prediction. That's just how industrial competition works.

China bet everything on execution. They won. Now they need to bet on creativity. The world's waiting to see if they can.

Key Takeaways

- Chinese EV makers produce 59% of global EVs but lack design differentiation, relying heavily on copying established silhouettes

- Design copying is economically rational short-term but creates long-term strategic traps in premium market segments

- Brand identity and original design become the primary differentiator when technical specs converge—expected by 2030

- Companies like NIO prove Chinese makers can build distinctive design languages, but require organizational commitment and design investment

- IP enforcement and geopolitical friction around design plagiarism create regulatory risks that incentivize original design innovation

![China's EV Design Problem: Why Copying Range Rover Is a Dead End [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/china-s-ev-design-problem-why-copying-range-rover-is-a-dead-/image-1-1771072734657.jpg)