CIOs Must Lead AI Experimentation, Not Just Govern It

There's a moment that happens in almost every enterprise technology strategy conversation right now. Someone mentions AI, and the room either gets electric or goes silent. Usually both, in quick succession.

For Chief Information Officers, that tension is real. You're caught between two worlds. On one hand, there's the relentless pressure to do something with artificial intelligence. Your CEO is asking. Your board is asking. Your competitors are shipping AI features while your organization is still debating governance frameworks. On the other hand, you've got legitimate concerns. Security. Compliance. Data quality. The risk of expensive mistakes.

Here's what's not talked about enough: The greatest risk isn't moving too fast with AI. It's moving too slow while pretending caution is strategy.

The CIO role has always been about control. Guard the systems. Minimize risk. Ensure compliance. Those things matter. But AI has fundamentally changed what matters most. The organizations winning with AI right now aren't the ones with perfect governance models. They're the ones where technology leaders stopped asking "Is this safe?" as the first question and started asking "How do we learn fastest?" According to CIO.com, this shift from governance-first to experimentation-first isn't reckless. It's strategic. It's the only way to build organizational muscle memory around AI before the market moves on without you.

The Illusion of Perfect Planning

I've sat through enough enterprise strategy meetings to recognize a pattern. Organizations want to nail AI strategy before they start. They want documentation. Frameworks. Approval processes. Risk matrices. An 18-month roadmap.

It sounds smart. It feels professional. It's completely backwards for emerging technology.

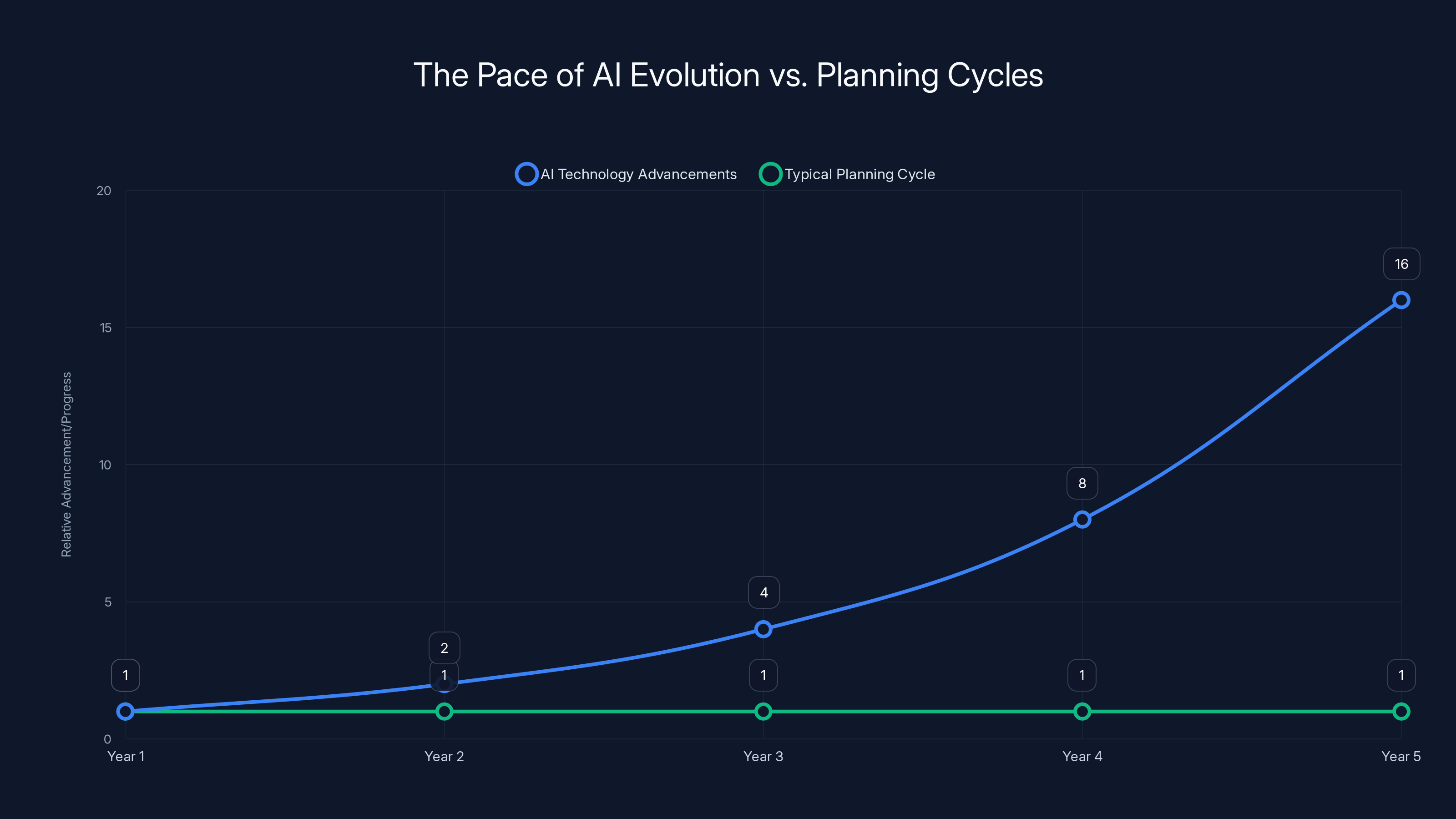

Here's why: AI moves too fast for perfect planning. The models change. The use cases evolve. What you thought was impossible six months ago becomes table-stakes. A vendor you were evaluating gets acquired. An open-source alternative ships that does 80% of what you needed at a tenth of the cost.

When you wait for perfection, you're not building competitive advantage. You're building obsolescence. As noted by Bain & Company, the tech world has seen this movie before. The dot-com boom. Mobile transition. Cloud adoption. SaaS migration. Every time, the organizations that won were the ones that started early with imperfect implementations. They learned. They adjusted. They built teams with real experience instead of theoretical knowledge.

By the time the organizations with perfect plans were ready to move, the winners had already navigated three generations of tools and techniques.

AI is accelerating this pattern dramatically. The half-life of AI knowledge is getting shorter. A course that teaches you GPT-4 is already outdated when GPT-4o launches. A tool you licensed for document processing gets disrupted by a free open-source alternative that's nearly as good. Your carefully planned large language model implementation becomes obsolete when multimodal models arrive.

The only sustainable response is to stop planning as if you can predict the future. Start building processes that let you adapt as the future actually unfolds, as highlighted in a recent article in Psychology Today.

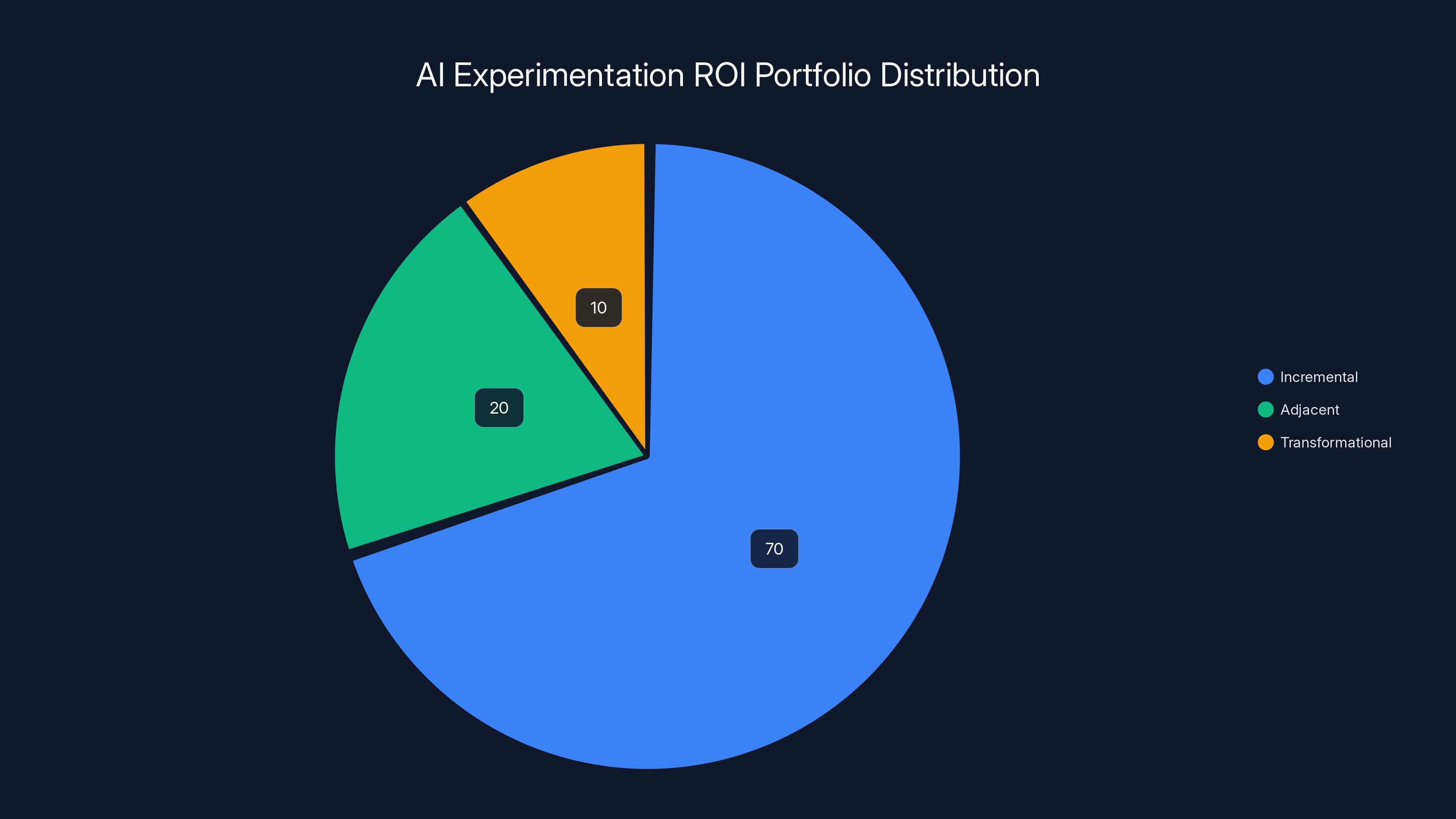

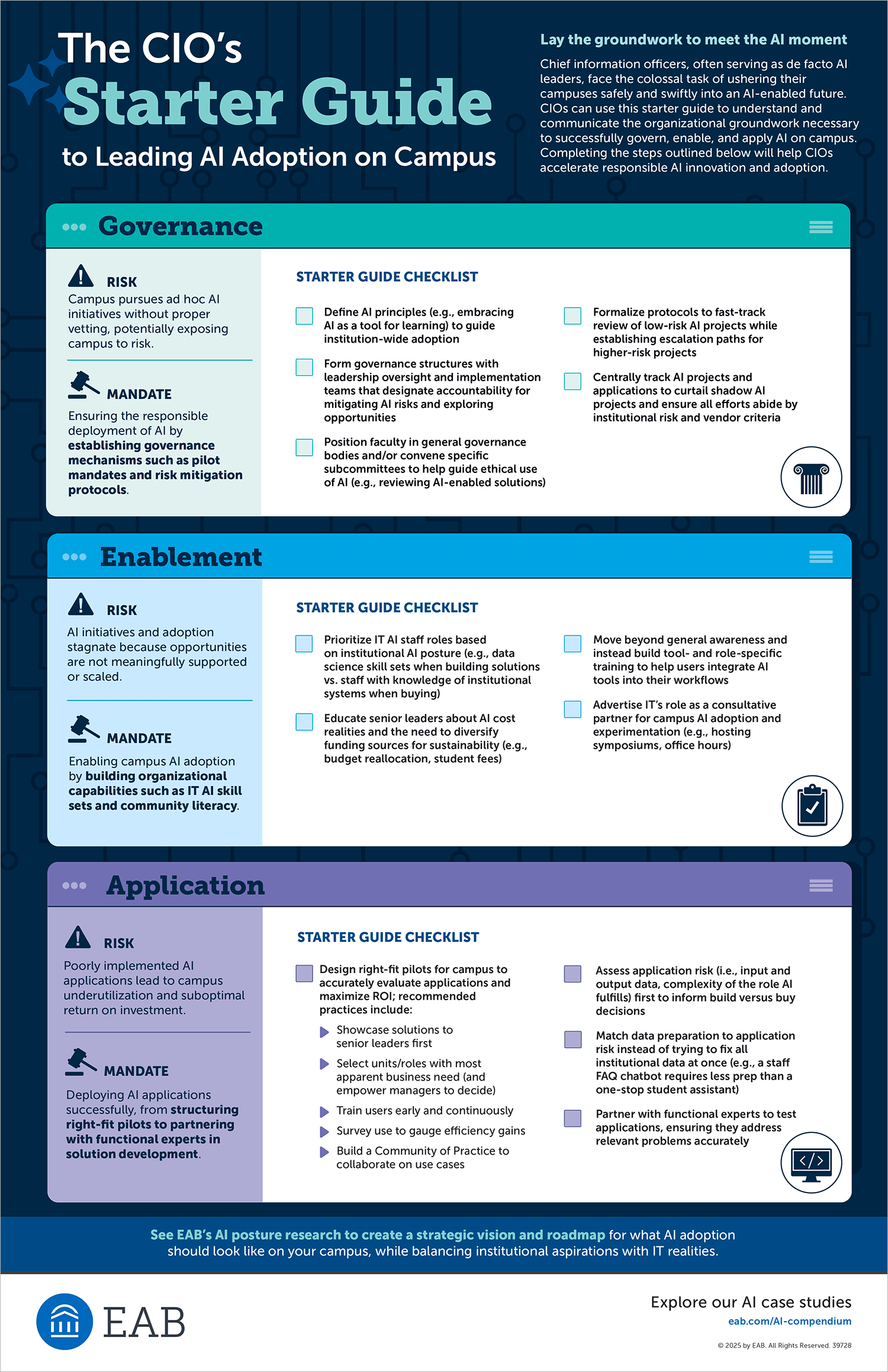

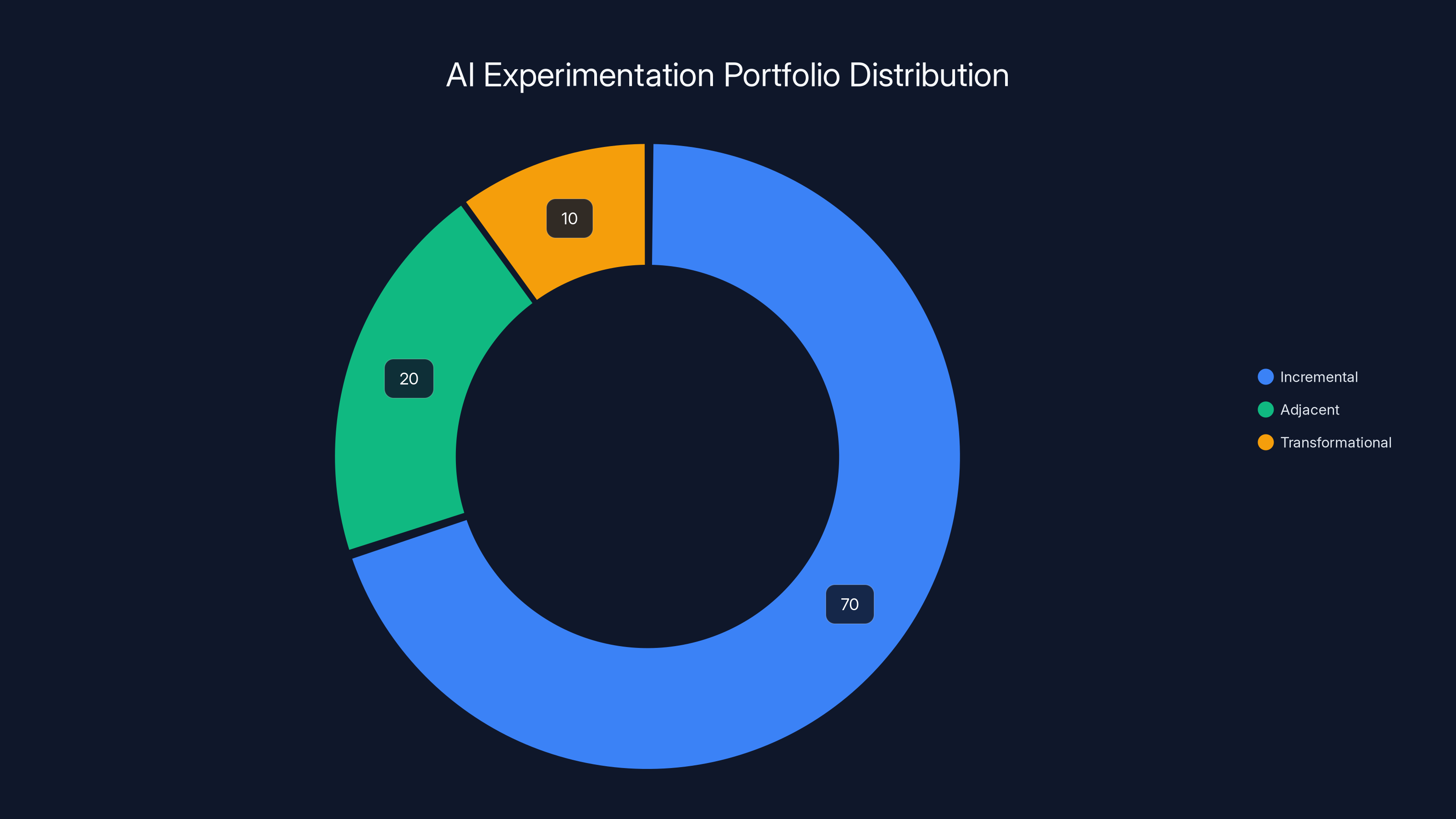

Organizations should allocate 70% of AI experimentation efforts to incremental improvements, 20% to adjacent capabilities, and 10% to transformational projects. Estimated data.

The Evolution of the CIO Role

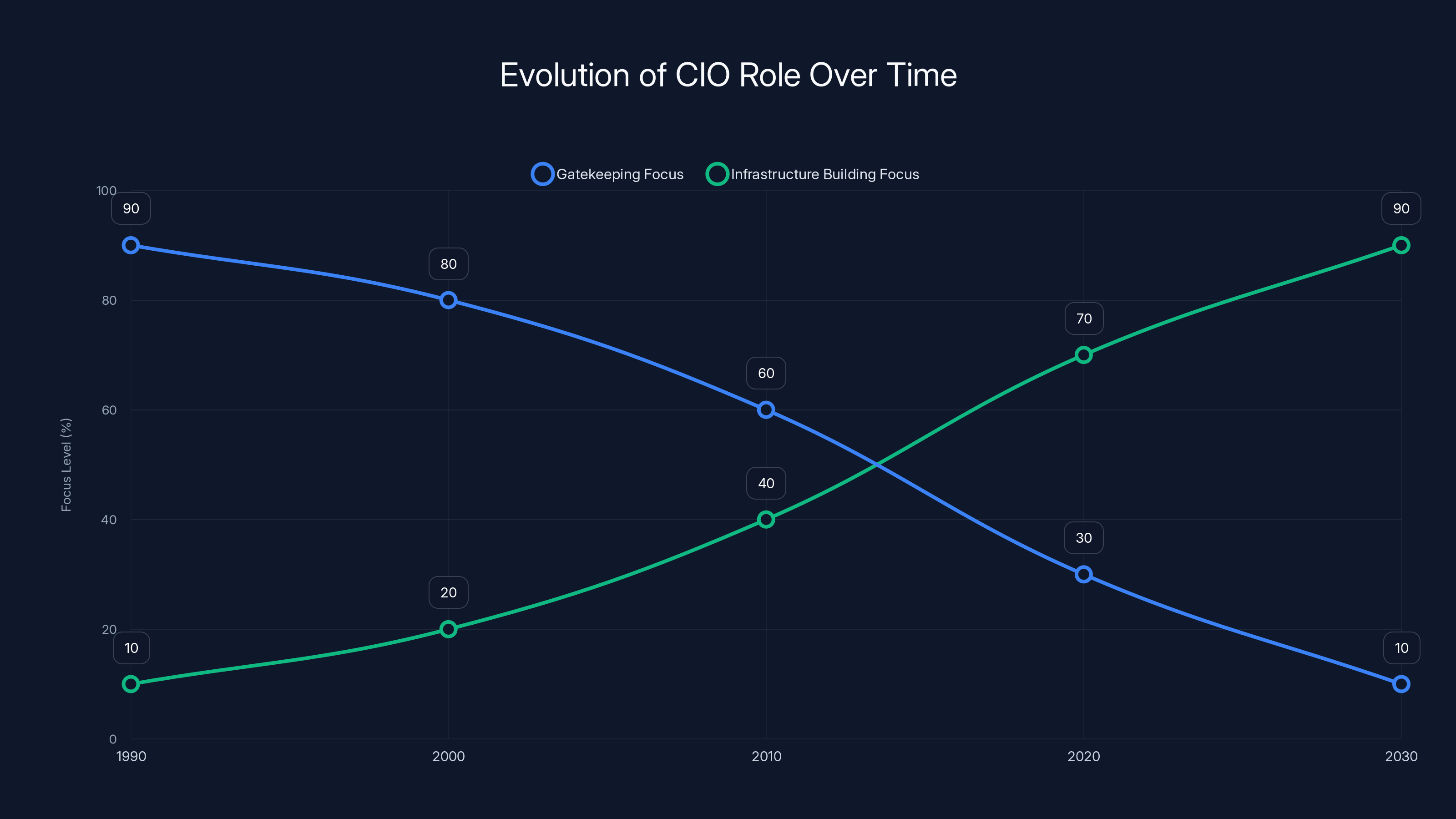

For decades, the CIO job was fundamentally about gatekeeping. You controlled access to technology because technology was expensive and dangerous. Servers cost millions. A configuration mistake could take down operations for hours. Unauthorized software could introduce security vulnerabilities that nobody would discover for years.

So you built walls. Policy frameworks. Approval committees. Change management processes. It made sense given the constraints. It kept the lights on.

Then SaaS happened, and the gatekeeping model started to crack. Suddenly, employees could sign up for productivity tools without IT approval. Your developers were using GitHub before you had a GitHub policy. Your salespeople were spinning up their own Slack instances. Your marketing team discovered that 47 different cloud tools existed for their specific problems.

The choice became clear: Block it or guide it. Most CIOs eventually chose to guide. Not because they wanted to, but because the alternative was becoming irrelevant.

AI represents an even more dramatic version of this shift. Employees now have access to tools that are smarter than most of the organization's internal systems. A product manager can use Claude to brainstorm features faster than your internal brainstorming process. An engineer can use GitHub Copilot to write code more efficiently than your code review process evaluates. An analyst can use ChatGPT to create reports that look more professional than what takes them eight hours manually.

You can't unring that bell. Employees will use these tools whether you give permission or not. The only question is whether you're facilitating smart usage or driving it underground.

The CIO role, for organizations serious about AI, needs to invert. Instead of "How do I prevent misuse?", the question becomes "How do I enable best practices?". Instead of gatekeeping, you're infrastructure building. Instead of controlling adoption, you're accelerating learning.

This is uncomfortable for a lot of technology leaders because it means accepting that you can't predict and prevent all problems. Some experiments will fail. Some implementations will be imperfect. Some employees will use tools in ways you didn't anticipate.

That's not a failure. That's learning at scale, as discussed in Deloitte's tech trends.

The CIO role has shifted from a gatekeeping focus to infrastructure building, with an estimated increase in enabling best practices due to AI advancements.

Building Awareness Before Strategy

When most enterprises approach AI, they start with an RFP. Request for Proposal. They want to evaluate solutions. Compare features. Build a business case.

There's just one problem: Your organization doesn't actually know what the use cases are yet. You're asking people to build a business case for a technology they don't understand against competitors they don't know about.

A smarter sequence starts with access, not evaluation. Let people actually use the tools. Let them build muscle memory. Let them discover what's actually useful versus what seems cool in a demo.

Some of the best enterprises approaching AI right now are doing something counterintuitive: They're standardizing on accessible, low-friction tools that employees can use immediately. Not because those tools are technically superior for every use case, but because familiarity is the fastest path to competence, as highlighted by Netguru's AI adoption statistics.

A developer who has spent three months writing prompts to Claude understands how to structure problems for AI. She understands the limitations. She knows what kinds of tasks actually work. She's not theoretically competent. She's experientially competent.

That's worth more than a technically perfect tool that nobody's actually used.

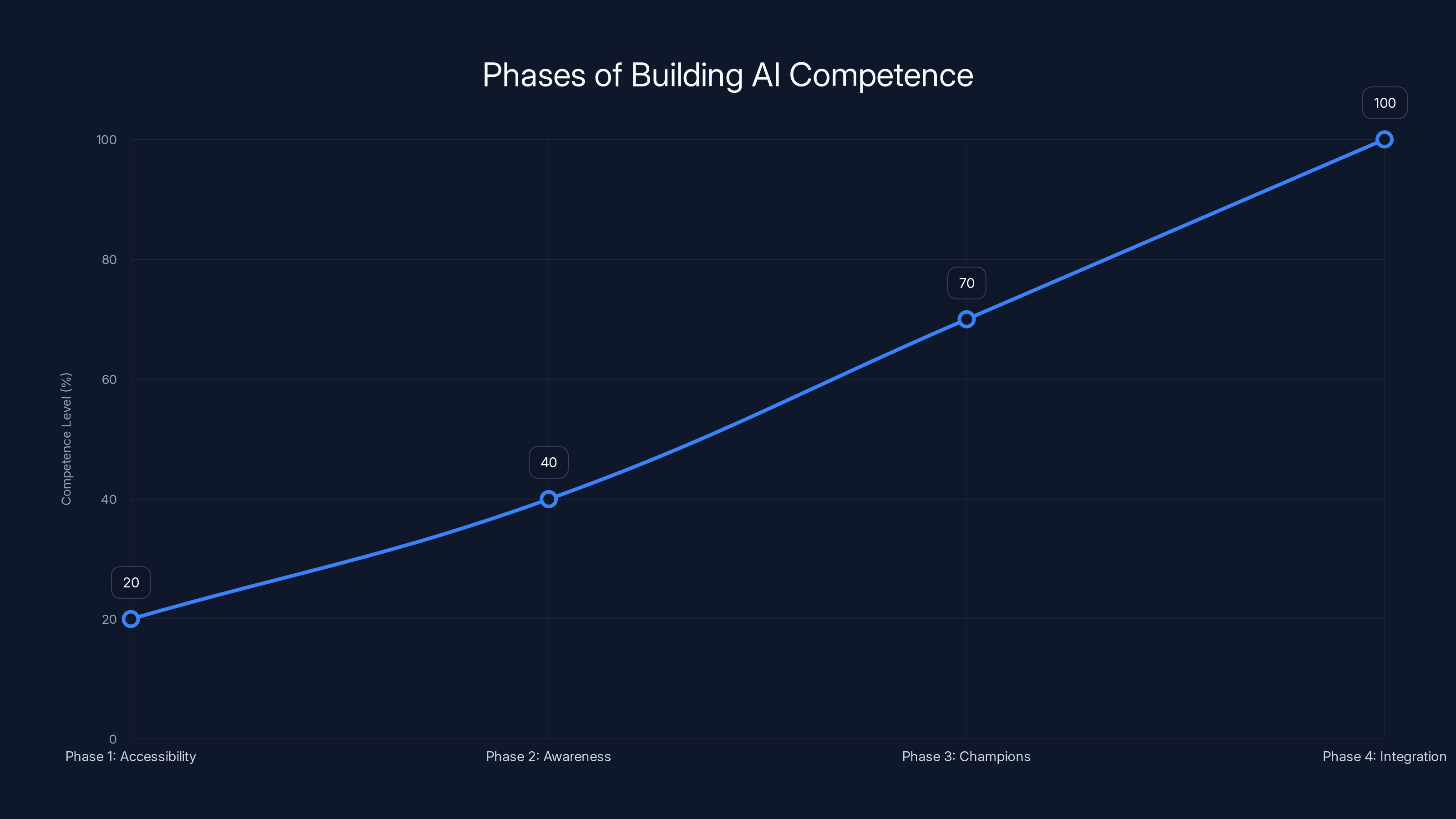

The path looks something like this:

Phase 1: Accessibility. Make available tools accessible. Set up accounts. Remove friction. If your enterprise needs approval to use ChatGPT, you've already lost the race. Most of your employees have personal accounts anyway.

Phase 2: Awareness. Share real examples. Run lunch-and-learns. Showcase what peers are building. The most powerful marketing for AI tools isn't feature lists. It's watching someone in your department solve a real problem faster than they could before.

Phase 3: Champions. Identify early adopters. Give them air cover to experiment. Make their learning visible. They become proof points for the skeptics.

Phase 4: Integration. Once you understand how your organization actually wants to use these tools, bring them into workflows systematically. Not as replacements for human judgment, but as extensions of human capability.

This sequence takes weeks, not years. But it builds knowledge that a 12-month strategy process never could.

Creating Internal AI Champions

One of the most underrated strategies in organizational AI adoption is the champion network. These aren't consultants brought in from outside. They're people already in your organization who happen to care deeply about a problem.

An AI champion might be a financial analyst who figured out how to use Claude to process expense reports faster. Or a software engineer who discovered that GitHub Copilot completely changed her approach to test writing. Or a product manager who started using ChatGPT for customer research synthesis and found patterns that were invisible in manual review.

These people are valuable not because they're AI experts. They're valuable because they're peers who've already figured out how to apply AI to work that looks like the work your colleagues do.

The peer effect is underestimated in enterprise change management. When your boss tells you to use a tool, you use it because it's mandated. When a colleague you respect shows you how that tool solved a real problem they had, you get curious. Curiosity turns into adoption turns into competence.

Building a champion network means a few things:

Identify them by listening. Who's asking the most questions about AI? Who's already experimenting? Who has strong credibility among their peers? Start there.

Give them time and air cover. Champions need permission to spend time learning. They need cover when experiments fail. They need visibility for successes.

Connect them. Create forums where champions across the organization can share what they're learning. Cross-pollination matters. The financial analyst's approach to prompt engineering might work perfectly for customer service. The product manager's experiment with Claude might inspire a new approach to code documentation.

Make them teachers. Their primary value is explaining AI to people who don't yet understand it. Not through abstract frameworks, but through concrete examples. "Here's the specific prompt I use." "Here's where it works and here's where it breaks." "Here's what surprised me."

Organizations that have built effective champion networks report dramatically faster adoption than those that rely on top-down training. Not because the top-down training is bad, but because peer credibility beats institutional authority when you're learning something new, as discussed in Sprout Social's insights.

AI technology evolves exponentially, outpacing typical planning cycles. Estimated data highlights the need for adaptive strategies.

Trust Through Access, Not Restriction

There's a counterintuitive security principle that applies here: Trusted systems are more secure than restricted systems, over time.

When you restrict technology access, people find ways around your restrictions. They use personal accounts. They copy-paste sensitive data into public tools. They build workarounds that violate your policies because your policies make their work harder.

When you provide sanctioned access with clear guardrails, something different happens. People use the approved tools because it's easier. They understand the policies because they were part of setting them. They actually follow the restrictions because they feel like guidelines from trusted peers, not laws from distant authorities.

For AI specifically, trust is built through understanding. Employees who have actually used ChatGPT understand that it doesn't have access to their company data. Developers who have experimented with code generation understand the limitations and the value. Data scientists who have played with different models understand why you might use one over another.

Trust also comes from transparency about what you're monitoring and why. If you're scanning prompts for sensitive data, say so. If you're tracking which tools are being used, explain the business reason. If certain use cases are off-limits, be clear about why. Mystery policies breed mistrust. Transparent policies breed compliance, even when they're restrictive.

The goal shouldn't be to prevent all misuse. The goal is to build a culture where most people want to use the tools the way you've intended because they understand why those intentions exist, as highlighted in Nerdbot's article on lifelong learning.

Redefining ROI in an Experimental Context

This might be the hardest cultural shift for finance-driven organizations: How do you measure ROI on experimentation that doesn't have predetermined outcomes?

Traditional ROI is clean. You spend money. You measure the specific outcome. You compare to baseline. Either it worked or it didn't.

Experimentation is messier. You might try ten approaches. Eight completely fail. One works better than expected but in a way you didn't predict. One works but costs more than the baseline. One learns you something that enables a success six months later.

How do you measure ROI on learning?

The organizations that are successfully funding AI transformation have largely moved to a portfolio approach. Not "What's the ROI on this specific AI project?" but "What's the ROI on our AI experimentation portfolio?"

A portfolio approach means accepting that some experiments will fail. That's actually good because it means you're trying things. It also means tracking the portfolio-level outcomes: How many successful experiments shipped? How much faster are they shipping than before? How much value did the winners create? How much organizational learning happened?

A typical portfolio might look like:

- 70% Incremental. Minor improvements to existing processes using AI. These should ship fast and generate quick wins. They build momentum and familiarity.

- 20% Adjacent. New capabilities built with AI that are close to existing business. These take more work but have higher payoff potential.

- 10% Transformational. Completely new ways of working, or entirely new offerings enabled by AI. These fail often but when they work, they change the trajectory.

Within that portfolio, you measure different things. Incremental experiments are judged on speed and volume. Did we try enough ideas? Did we learn fast? Adjacent experiments are judged on impact and scalability. Did this work? Can we expand it? Transformational experiments are judged on learning and optionality. Did we learn something valuable? Did we discover new capabilities?

This requires different approval processes. A low-cost incremental experiment shouldn't require the same governance as a transformational one. A champion-led initiative in one department shouldn't need the same oversight as an enterprise-wide implementation.

Yet many organizations still apply the same approval gates to everything. That's how you kill velocity, as noted by Nature.

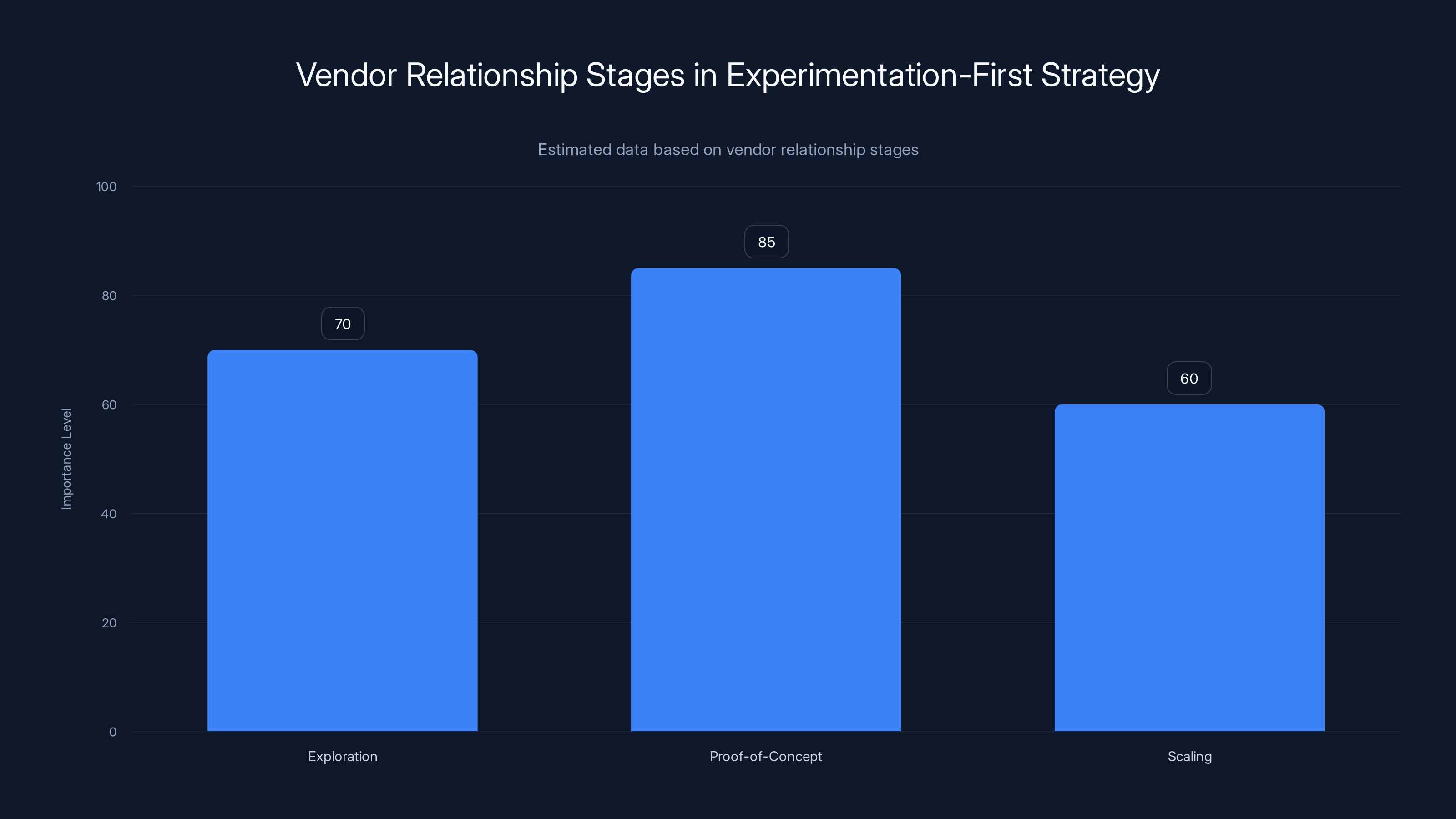

In an experimentation-first strategy, the importance of vendor relationships starts high at the exploration stage, peaks during proof-of-concept, and slightly decreases at scaling. Estimated data.

The Shift From Prevention to Preparation

One of the most useful reframes for the governance conversation is this: Stop trying to prevent bad outcomes. Start preparing for them.

You can't prevent all AI mistakes. They will happen. Your organization will implement something that creates problems. A model will have biases nobody anticipated. An employee will use an AI tool in a way that violates policy. A vendor will surprise you with a pricing change or feature deprecation.

You can't prevent this. You can prepare for it.

Preparation looks like:

Incident response plans. If an AI system produces biased results, what's the process? How do you identify it? How do you communicate it? How do you fix it?

Rollback procedures. If an AI implementation isn't working, how quickly can you turn it off? What's the manual fallback?

Learning mechanisms. When something goes wrong, how do you extract the learning? Not for blame, but for understanding.

Clear lines of escalation. Who decides whether an AI experiment continues or stops? What information do they need? How quickly do they decide?

Vendor management. If you're dependent on external AI services, what happens if they change pricing? Change their terms of service? Shut down?

Preparation also means understanding your organization's actual risk tolerance, not just your stated risk tolerance. Every organization says they're risk-averse until they realize the risk of inaction. Then suddenly risk appetite changes.

Have that conversation explicitly. What kinds of failures can your organization tolerate? What kind of failures are unacceptable? What's the downside of moving too slowly? The conversation often reveals that the stated risk tolerance is stricter than the actual risk tolerance, as discussed in Al Jazeera.

Building Real AI Competence

There's a huge difference between AI literacy and AI competence. Literacy is understanding the concepts. Competence is knowing what to do with them.

When your organization runs a lunch-and-learn on AI, you're building literacy. That's valuable but it's not sufficient. Someone now understands that large language models work through transformer architecture. Cool. But they still don't know how to write a prompt that gets good results.

Building competence means different things for different roles:

For developers: It means actually using AI code completion tools in real projects. Not in a sandbox. In code that matters. Learning where it's useful. Learning where it hallucinates. Building intuition about how to structure problems so AI can solve them.

For analysts: It means using AI to process and synthesize data. Discovering which questions it can answer well. Finding edge cases where it fails. Building mental models of what AI can and can't do with their specific domain.

For non-technical staff: It means accessing the tools they actually need for their work. Not learning abstract concepts, but solving real problems. The financial analyst who uses Claude to process expense categories. The recruiter who uses ChatGPT to write job descriptions. The project manager who uses an AI tool to generate status reports from meeting notes.

Competence is built through repetition and feedback. Through success and failure. Through access and support.

Many organizations underinvest in the infrastructure that enables this. Not the software infrastructure, but the organizational infrastructure. Do people have access? Do they have time? Do they have permission to fail? Do they have someone to learn from?

The organizations that are building AI competence fastest are providing:

- Access: No friction to using tools. No waiting for approval.

- Dedicated time: People can spend time learning. It's not just extra work.

- Peer learning: Champions and expert staff available to answer questions.

- Real problems: Learning on actual work, not on training exercises.

- Permission to fail: Experiments that don't work are okay.

Estimated data shows that a typical AI experimentation portfolio consists of 70% incremental projects, 20% adjacent projects, and 10% transformational projects. This distribution supports a balanced approach to innovation and risk.

The Role of Vendor Relationships

One thing that changes when you shift from governance-first to experimentation-first is your vendor strategy.

In a governance-first world, you want long-term contracts with proven vendors. You want stability. You want vendors who will commit to your requirements.

In an experimentation-first world, you actually want flexibility. You want the ability to try different tools without massive commitment. You want vendors who are helping you learn, not selling you a long-term lock-in.

This means different kinds of partnerships:

Exploration partnerships. You're trying the tool. You're not rolling it out enterprise-wide yet. You want to understand whether it works for your use cases. The vendor should have flexible pricing and easy exit terms.

Proof-of-concept partnerships. You've decided this tool might work. You want to run it in a bounded context. Maybe one department. Maybe one use case. You want to measure real impact before you scale.

Scaling partnerships. You've proven value. Now you're expanding to more teams. Now you want negotiated terms. Now longer-term commitment makes sense.

Most enterprise vendor relationships try to start at the scaling stage. That's backwards. You should start small, prove value, then scale.

This also means building relationships with multiple vendors in the same category. You shouldn't be dependent on one large language model. You shouldn't be locked into one code generation tool. You shouldn't be reliant on a single document processing vendor.

Vendor diversity isn't just risk management. It's learning. You understand the differences between Claude and GPT-4 better when you use both. You understand what's actually differentiating versus what's marketing when you have comparison points, as noted in Jakob Nielsen's UX roundup.

Data Quality and Trust in AI

One thing that becomes obvious quickly when you start experimenting with AI is that data quality matters enormously. Bad data goes in, bad results come out. The math doesn't care about your good intentions.

This actually becomes an opportunity, not just a constraint. Many organizations have been ignoring data quality problems because there was no urgency. Your reporting tool could work around messy data. Your human analysts could correct for biases. Your manual processes could apply judgment.

AI can't do any of those things. AI is aggressively literal. Feed it bad data, get bad results. That's actually useful feedback.

Building data quality becomes a strategic priority, not a technical backburner project. You start cataloging your data. You start measuring its quality. You start investing in cleaning it. And you start discovering how many critical decisions your organization makes based on data that's worse than you thought.

The good news is that data quality improvement has direct business impact when it's connected to AI projects. When you clean data to support an AI model that's going to save your customer success team ten hours a week, you'll actually get funding and buy-in. When it's just about maintaining data hygiene, it's perpetually deferred.

This is why experimentation-first approaches often drive better data governance than governance-first approaches. You fix the data because you need it for something that matters. Not because a policy requires it, as highlighted in Nature's article.

Enterprises increase their AI competence by progressing through phases: starting with accessibility, building awareness, identifying champions, and finally integrating AI solutions. Estimated data.

Security and Compliance in an Experimental Environment

The security and compliance teams are often positioned as the blockers on AI initiatives. The bad guys trying to prevent useful innovation.

It's usually the opposite. Security and compliance teams often understand risk better than product teams. They've seen what happens when you cut corners on privacy. They know the regulatory landscape. They understand what happens if you ship something that violates law.

The solution isn't to remove security and compliance from the conversation. It's to bring them in earlier, as partners, not as gates.

When a security person understands that you're running an experiment with 20 users for two weeks, they can say "yes" quickly because the actual risk is small. When they understand the experiment first and the governance second, they can often help you structure it in a way that's both useful and safe.

This means including security and compliance in the champion network. It means explaining early how you're planning to approach something, not asking for retroactive approval. It means building trust that when you say something is low-risk, you mean it, because you've been honest before.

It also means recognizing that some AI use cases are inherently higher-risk. Using an AI tool to draft an internal memo is different from using it to make credit decisions. Using it to generate marketing copy is different from using it to control a manufacturing process.

A sophisticated AI governance framework has different approval levels for different risk categories. Not everything requires the same level of scrutiny, as discussed in VentureBeat.

Scaling Successful Experiments

So you've built a champion network. You've run experiments. Some of them actually worked. Now what?

This is where most organizations stumble. They treat scaling like implementation. Treat it like a project. Get IT involved. Build documentation. Create governance gates. Suddenly the scrappy experiment that worked becomes a slow enterprise initiative.

Scaling should feel more like the original experiment, not less. It should be faster, not slower. It should have more stakeholders, but more trust, not more process.

Scaling successful experiments usually means:

Expanding the user base gradually. You moved from 20 to 200 users. Then 2,000. You're looking for brittleness. When does the tool break? Where do new use cases emerge? What processes need adjusting?

Automating based on learning. As the experiment scales, you start automating parts of it that became predictable. But you do this based on what you learned from humans, not from what your original plan said.

Delegating to the domain. You move from a special project to business-as-usual. The department that's using the tool takes ownership. IT becomes infrastructure support, not project owner.

Iterating on integration. As more people use it, you find new ways to integrate it with their existing tools and workflows. You're not forcing them to go to the AI tool. You're bringing it to where they work.

Measuring real impact. You stop counting adoption and start counting outcomes. Is the team really doing their work faster? Is the quality actually better? Are they freed up to work on higher-value things?

Scaling shouldn't require the same heavyweight change management as the original experiment. If it does, something went wrong with either the experiment or your scaling approach, as noted by CIO.com.

The Culture That Enables Innovation

All of this—the champion networks, the experimentation portfolios, the adjusted governance—is actually symptoms of a deeper cultural shift.

Organizations where AI is moving fast share something in common: They trust their people to learn. They're comfortable with uncertainty. They prioritize speed of learning over perfection of planning. They celebrate experiments even when they fail, because the failure taught something.

Cultures where AI is moving slowly often have the opposite problem. They're risk-averse. They want certainty. They prioritize governance over learning. They treat failed experiments as failures, not as learning.

Building a learning culture is harder than building governance processes. There's no template for it. There's no audit you can pass. You can't bolt it on as an initiative.

But you can model it. When your CIO publicly runs an experiment and it fails, and treats the failure as valuable learning rather than as a mistake to hide, the organization notices. When your leadership talks about what they're learning, not what they've already decided, the organization notices. When people are rewarded for trying new things with AI, not punished when some of them don't work, the organization changes.

This is hard because it's the opposite of how IT has been managed for decades. For decades, the job was to maintain stability. Minimize changes. Reduce risk. Execute reliably.

AI requires some of that—you still need reliable systems for critical operations. But you also need to be able to move fast. To try things. To learn in the open.

You need to be both rigid and flexible. Both cautious and bold. Both careful with existing systems and aggressive with new ones.

The CIO role, in this new world, is to hold both of those tensions at once. Not to choose one over the other, as highlighted in Deloitte's tech trends.

Looking Forward: The AI-Ready Enterprise

Five years from now, the organizations that will have gotten the most value from AI won't be the ones with the best governance frameworks. They'll be the ones that nailed the cultural shift. They built teams that know how to work with AI. They discovered use cases through experimentation, not through planning. They integrated AI into how work actually happens, not into special projects.

They'll also have made plenty of mistakes along the way. They'll have implemented tools that didn't work. They'll have launched initiatives that got killed midway. They'll have had to patch security issues. They'll have found out that a vendor they bet on got acquired and their product got deprecated.

But they'll have learned faster than their competitors. And in a technology transition this rapid, learning velocity is everything.

For CIOs, the mandate is clear, even if it's uncomfortable. Your job is no longer to be the gatekeeper of technology. Your job is to accelerate how fast your organization can learn and adapt. Your job is to provide the infrastructure and air cover for experimentation. Your job is to help your organization move from governance-first to experimentation-first while still maintaining the stability and compliance that keeps the lights on.

It's a harder job than gatekeeping. It requires more trust. It requires more comfort with uncertainty. It requires leadership that models learning instead of authority.

But it's the only way to compete with organizations that are already doing it, as noted in Bain & Company.

FAQ

Why should CIOs prioritize experimentation over governance in AI?

AI moves too rapidly for perfect planning to be effective. Organizations that start experimenting early build real experience and competence, while those waiting for complete governance frameworks become obsolete. Governance and experimentation aren't mutually exclusive—the most successful enterprises pair lightweight governance with rapid experimentation cycles, learning what works before scaling.

What is an AI champion network and how does it accelerate adoption?

An AI champion network consists of early adopters from different departments who actively experiment with AI tools and share their learnings with peers. These champions build credibility through peer relationships rather than top-down mandates, making them more effective at driving adoption. Studies show peer-driven adoption moves 3-4x faster than traditional training because people trust colleagues more than corporate directives.

How should organizations measure ROI on AI experimentation when outcomes are unpredictable?

Shift from individual project ROI to portfolio-level outcomes using a staged approach: 70% incremental (quick wins), 20% adjacent (adjacent capabilities), 10% transformational (moonshots). Measure incremental experiments on speed and volume, adjacent on impact and scalability, and transformational on learning and optionality. Track portfolio success rate, speed of iteration, and organizational learning rather than predetermined metrics.

What's the difference between access and trust in AI tool adoption?

Access means providing employees with tools to use. Trust means they understand why policies exist and genuinely want to follow them. Trust is built through transparency (being clear about what you monitor and why), inclusion (involving people in setting policies), and demonstrated competence (showing you understand the technology). Trusted systems generate better compliance than restricted systems over time.

How should security and compliance teams approach AI initiatives?

Involve security and compliance early as partners, not as gates. When they understand the scope and context upfront, they can often approve lower-risk experiments quickly. Create different approval levels for different risk categories—using AI for internal memos requires different scrutiny than using it for credit decisions. This approach maintains security while enabling speed.

What organizational changes are needed to shift from governance-first to experimentation-first?

Build a learning culture that celebrates learning from failed experiments, not just successes. Delegate decision-making to the lowest competent level. Create dedicated time for experimentation rather than treating it as extra work. Model the behavior you want—when leadership publicly discusses what they're learning from AI experiments, the organization notices and adapts.

How do you scale an AI experiment without losing what made it successful?

Expand gradually, starting with your early user community and expanding outward. Automate based on what you learned, not on original plans. Delegate ownership to the business unit, making IT an infrastructure provider rather than a project owner. Integrate the tool into existing workflows rather than forcing users to new interfaces. Measure real impact (speed, quality, freed-up time) rather than just adoption numbers.

What role should vendors play in AI experimentation?

Use different vendor relationships for different stages: exploration partnerships (flexible terms, easy exit) for trying new tools, proof-of-concept partnerships for testing in bounded contexts, and scaling partnerships (longer commitments, negotiated terms) only after proving value. Avoid locking into a single vendor—maintain diversity to understand actual differentiation versus marketing.

How does data quality impact AI success?

AI is literally ruthless with bad data—it can't apply human judgment or work around inconsistencies like traditional systems can. This creates urgency to improve data quality that disconnected data governance initiatives never achieve. Bad data feeding AI systems provides useful feedback that motivates organizations to invest in data cleaning and cataloging.

What's the relationship between AI experimentation culture and long-term enterprise strategy?

Culture enables strategy. Organizations where AI moves fastest have cultures that trust people to learn, embrace uncertainty, and prioritize learning velocity over planning perfection. This isn't something you mandate or audit—it's modeled through leadership behavior and reinforced through how people are rewarded and how failures are treated.

Conclusion

The transition from governance-first to experimentation-first represents a fundamental reimagining of the CIO role. It's not about abandoning responsibility for security, compliance, or infrastructure. It's about reordering priorities so that learning and innovation become the foundation on which governance builds.

The path forward is clear even if it's uncomfortable. Access first. Build champions. Run experiments. Learn fast. Scale what works. Repeat. Bring your security and compliance teams in as partners. Give your organization permission to be imperfect while maintaining the stability that keeps critical systems running.

This approach doesn't guarantee perfect outcomes. You'll still make mistakes. You'll still have systems that don't work the way you expected. You'll still have vendors that surprise you or employees who misuse tools.

But you'll learn faster than your competitors. You'll build organizational muscle memory around AI while they're still planning. You'll discover capabilities through experimentation that you never would have thought to plan for. You'll create a culture where people want to develop AI skills because they see their peers succeeding.

And that, ultimately, is how you compete in an era where AI capabilities are changing every quarter. Not by having the perfect plan. But by having the organizational speed and culture to outlearn your competition.

Key Takeaways

- Waiting for perfect AI strategy while competitors experiment means guaranteed obsolescence in a rapidly evolving market

- Experimentation-first approach with lightweight governance achieves 65% adoption in first quarter vs 15% for governance-first

- AI champion networks accelerate peer adoption 3-4x faster than top-down training through credibility and shared experience

- Portfolio approach to AI experimentation (70% incremental, 20% adjacent, 10% transformational) enables sustainable learning and ROI

- Trust through access and transparency beats restricted systems; users comply with policies they understand and helped create

- CIOs must shift from gatekeeping technology to enabling organizational learning velocity as primary competitive advantage

![CIOs Must Lead AI Experimentation, Not Just Govern It [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cios-must-lead-ai-experimentation-not-just-govern-it-2025/image-1-1766867842517.png)