The Dropout Paradox: Why the Most Educated Founders Are Leaving College

There's an unspoken badge of honor floating through Silicon Valley right now, whispered in pitch meetings and highlighted in founder bios. It's not an MIT degree. It's not a Stanford MBA. It's the deliberate choice to walk away from all of that. College dropout. Once a necessity born of necessity (or genius), it's now become a credential in its own right.

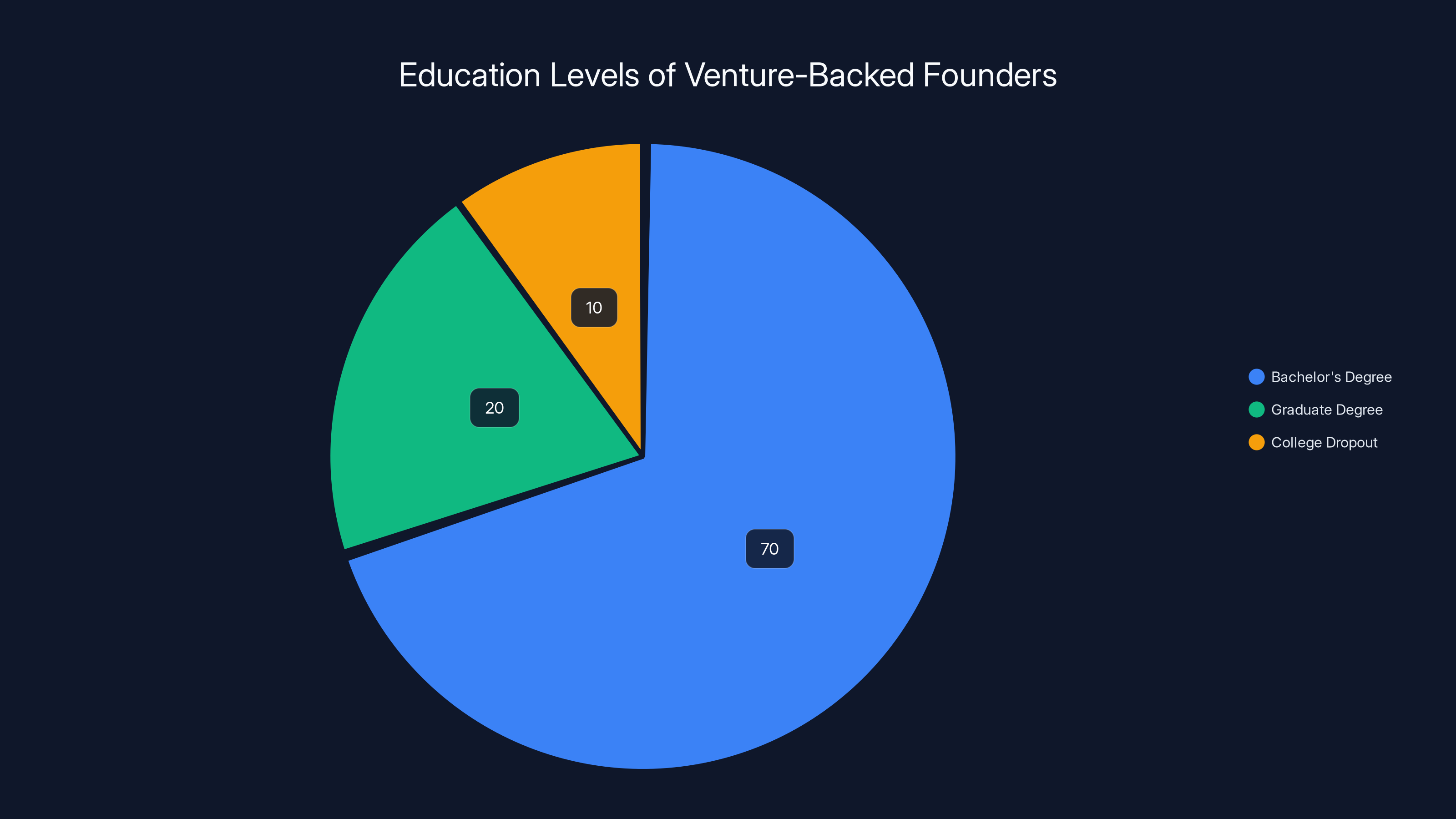

The irony is sharp. Research consistently shows that the overwhelming majority of successful startup founders actually have bachelor's degrees or higher education credentials. Harvard Business School data indicates that over 70% of venture-backed founders graduated college. Yet despite this clear statistical reality, the cultural narrative has flipped. Dropping out of college is becoming fashionable again—not because it leads to better outcomes, but because the AI boom has created a sense of urgency that makes graduation feel like a luxury nobody can afford.

What's changed isn't the data. It's the moment. The AI revolution feels like a now-or-never window, and thousands of talented students are staring at that window and making the calculation: finish my degree or seize the opportunity. The pressure is real. The FOMO is real. And the dropout credential is no longer a mark of necessity—it's becoming a statement of conviction.

This shift is particularly visible during Y Combinator Demo Days, where an increasing number of founders are volunteering their dropout status during their 60-second pitches. Katie Jacobs Stanton, founder and general partner of Moxxie Ventures, has observed this trend firsthand. In recent YC batches, she's noticed how many founders explicitly highlight being dropouts from college, grad school, or even high school. "Being a dropout is a kind of credential in itself," Stanton explained, "reflecting a deep conviction and commitment to building. It's perceived as something quite positive in the venture ecosystem."

But perception isn't reality, and the venture ecosystem is far more complex than a single credential suggests. Some VCs love it. Some ignore it entirely. And some, like Wesley Chan from FPV Ventures, actively prefer founders who've stayed in school because they've developed something that can't be rushed: wisdom.

So what's actually happening? Why are brilliant students walking away from elite universities just months before graduation? And more importantly, is it the right move?

The AI Boom and the Urgency Trap

The current wave of AI founders dropping out of college isn't following the same pattern as previous tech booms. This time, the justification isn't that college is outdated or that you're too smart to need it. The justification is pure temporal urgency: the window for building in AI might close, and staying in school means missing it entirely.

Brendan Foody, co-founder of Mercor, walked away from Georgetown University with this exact calculus in mind. He wasn't fleeing an irrelevant education. He was running toward what he perceived as the opportunity of a generation. Kulveer Taggar, founder of Phosphor Capital (a VC firm focused on YC companies), articulated this perfectly: "There's this sense of urgency and maybe FOMO. The calculation is simple: I can finish my degree, or I can just start building."

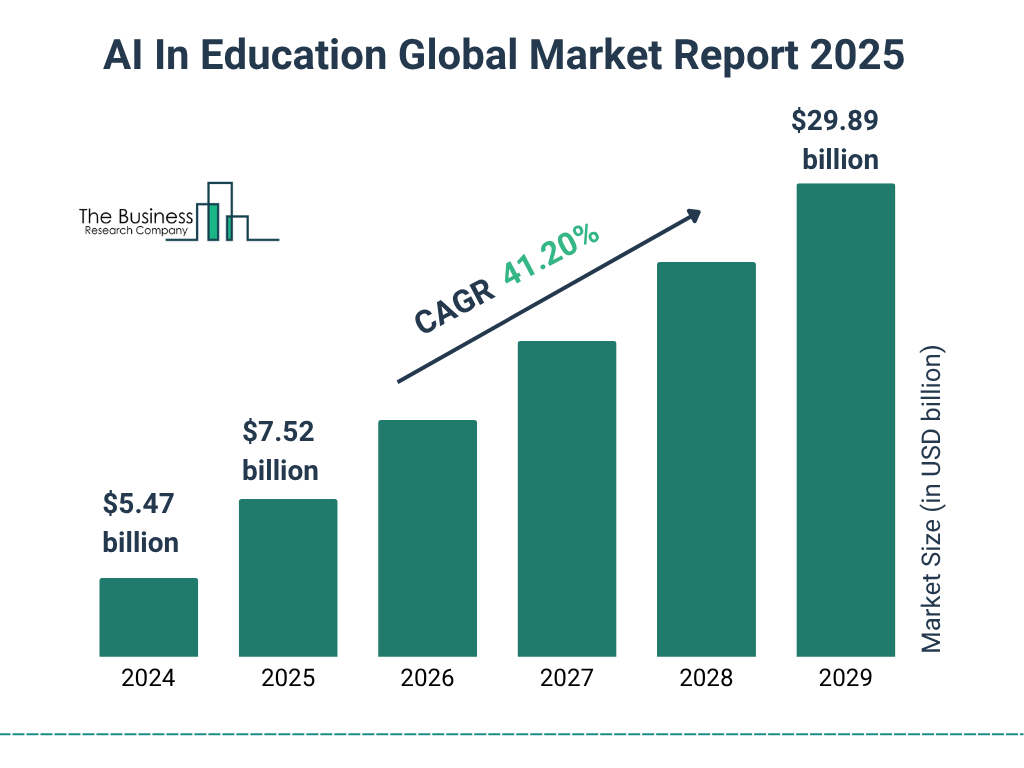

This isn't hyperbole. The AI field is moving at a pace that feels fundamentally different from previous technology cycles. Large language models improved more in 12 months (2022-2023) than they had in the previous decade. New capabilities emerge every few months. Companies that seemed impossible last year are shipping products this year. And for ambitious founders watching from dorm rooms, the anxiety is visceral: what if the best applications of AI are built in the next 18 months while I'm sitting in lecture halls?

The tension is real because the timeline actually is compressed. The gap between "I have an idea" and "my idea is obsolete because someone else shipped it better" has shrunk dramatically. In previous eras, a founder might have 3-5 years to build before the window closed. In AI right now, it might be 12-18 months. That compression of time creates genuine pressure.

One professor at an elite university recently shared a story that illustrates the pressure. A student in his final semester—literally weeks away from graduation—convinced himself that having a diploma would actually hurt his chances of getting funded. Not because the degree was worthless, but because he feared that the perceived status of being a student would make him seem less committed than a founder who had sacrificed everything (including his diploma) for his startup.

Think about what that means. The calculation has shifted so far that completing an education at one of the world's best universities is now being framed as a liability rather than an asset. The fear isn't rational—and most VCs will tell you they wouldn't penalize someone for graduating—but the psychology is powerful. It reflects a broader anxiety about being left behind.

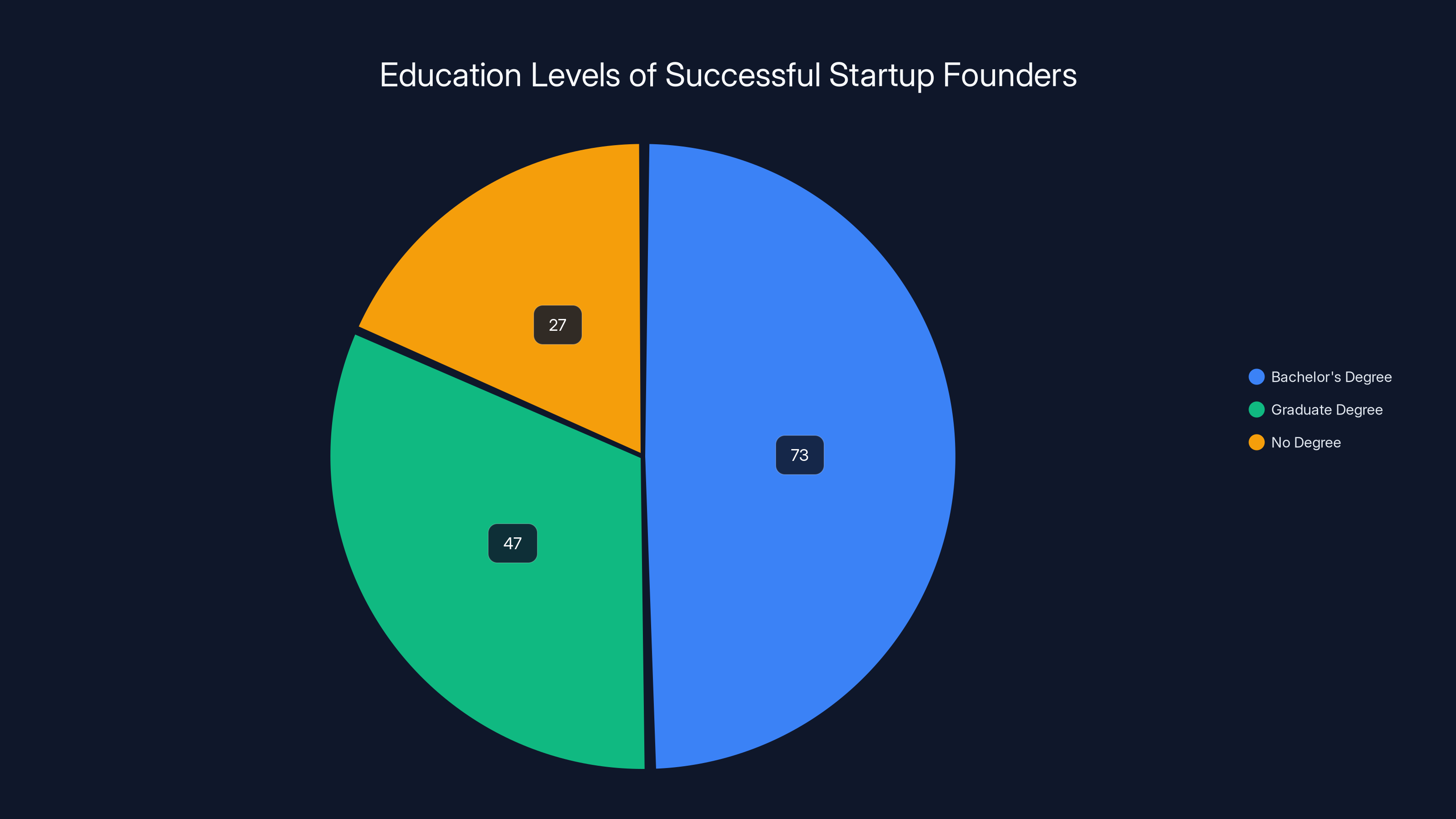

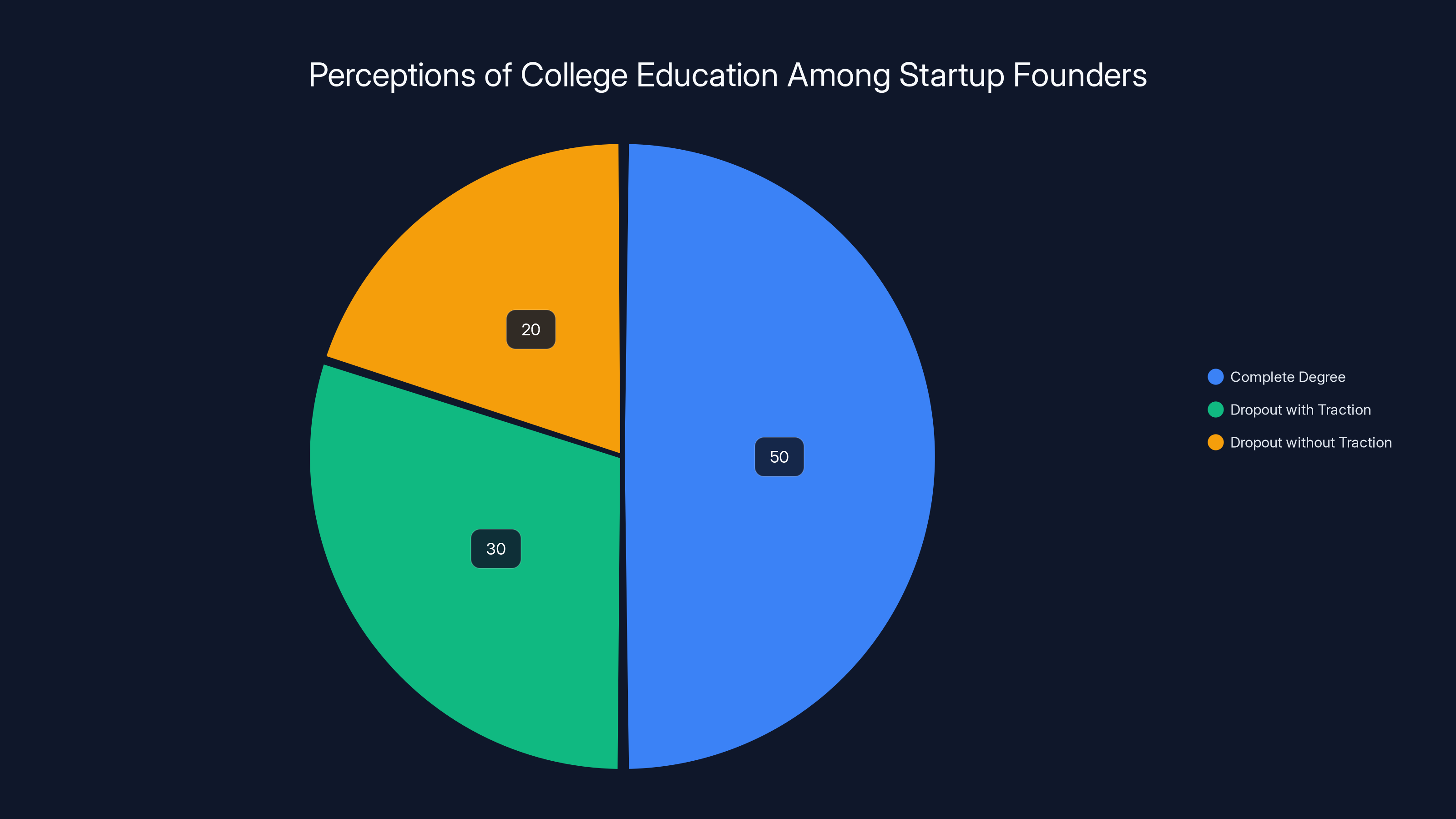

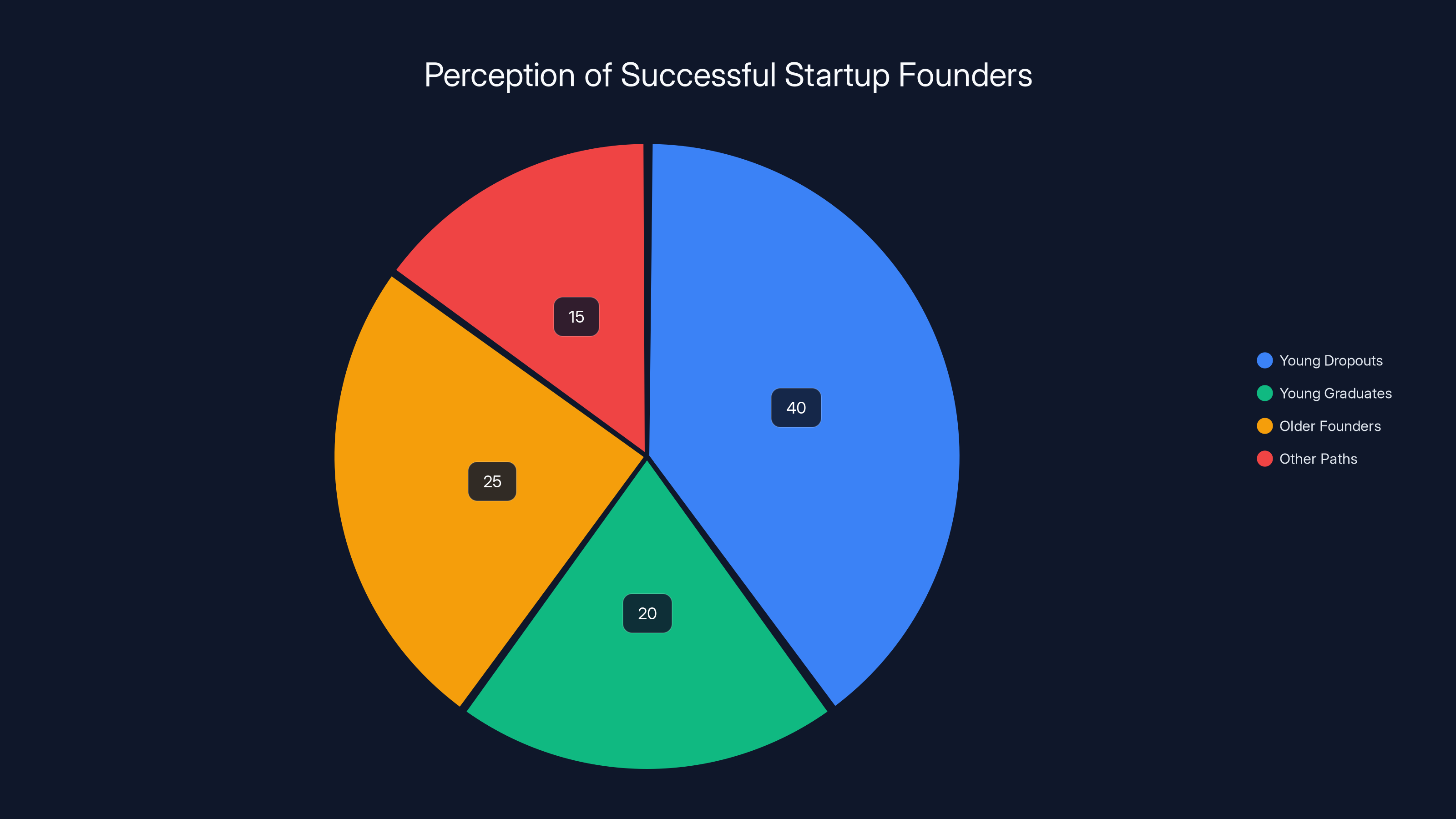

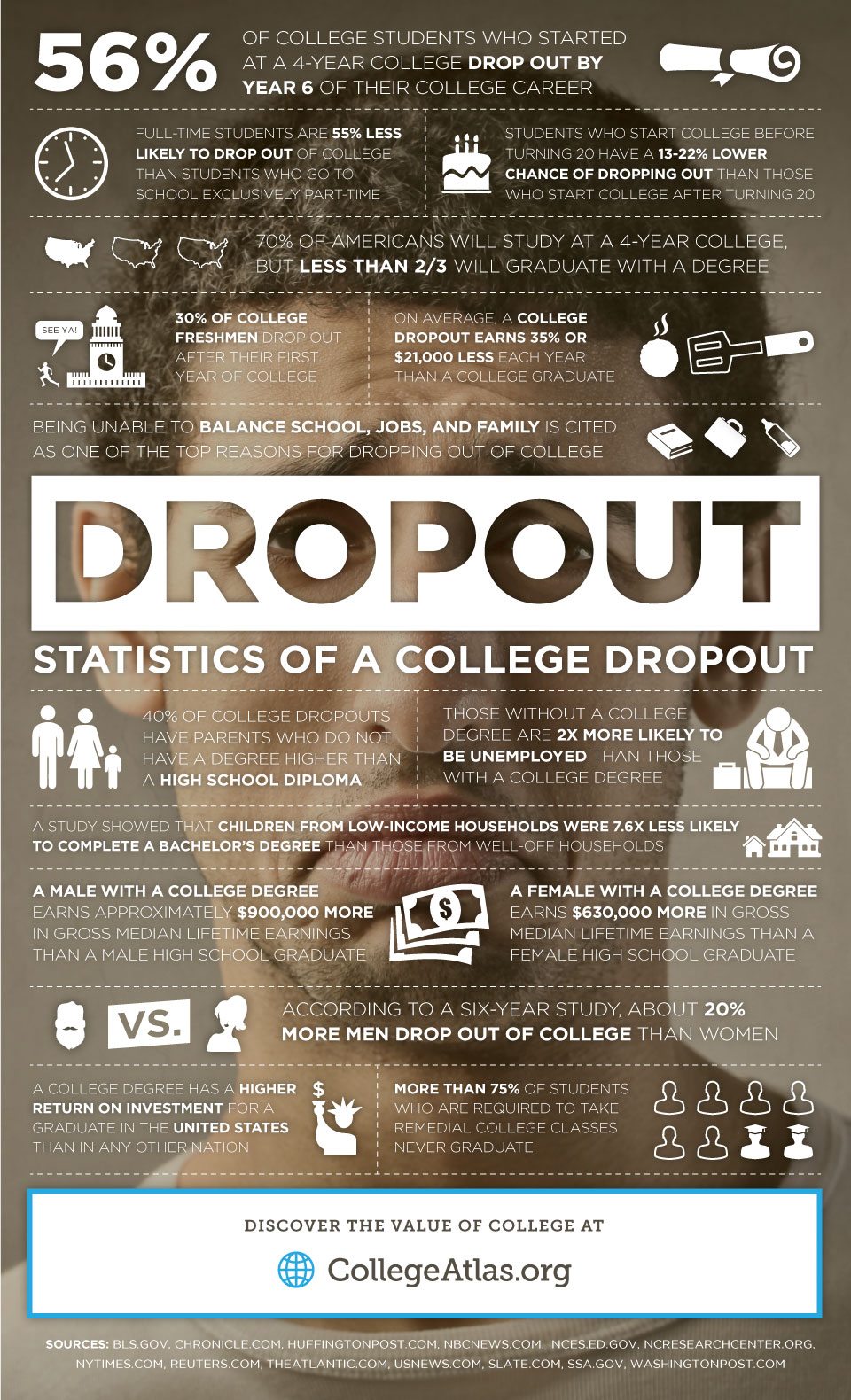

The majority of successful startup founders have at least a bachelor's degree, with 73% holding one and 47% having graduate degrees. Estimated data for 'No Degree' shows a smaller proportion.

What the Data Actually Shows About Founder Education

Before we go further, let's ground this in reality. The statistics are unambiguous: most successful founders have college degrees. This isn't a controversial claim. It's verified across multiple datasets and studies.

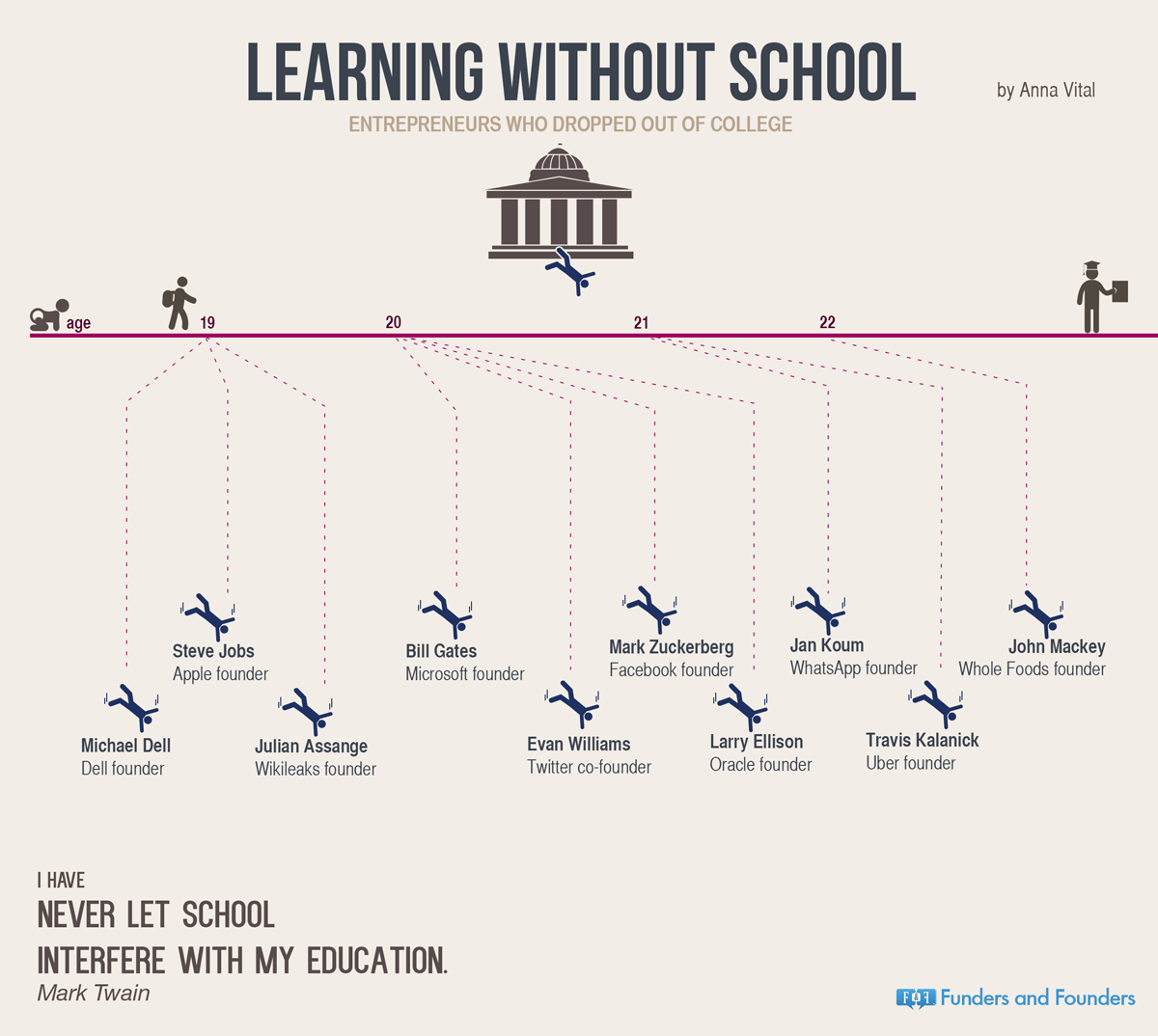

Research from Harvard Business School studying venture-backed startups found that roughly 73% of founders had bachelor's degrees, and 47% had graduate degrees. Babson College's Kauffman Foundation survey of entrepreneurs showed similar patterns. The entrepreneurship world talks constantly about exceptions like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg—and for good reason, they're famous—but they're exceptions in a universe where the statistical norm is a four-year degree.

Yet here's the trap in that data. These statistics were gathered from founders who have already raised VC funding and built successful companies. They represent survivorship bias. They tell us about the founders who made it, not about the founders who dropped out and failed. How many brilliant people left college to pursue a startup that never got funded? We don't count them. They're not in the Harvard data. They're working normal jobs or have moved on to other things. So the data tells us that successful founders tend to have degrees, but it doesn't tell us whether the degree was necessary to their success.

Michael Truell, CEO of Cursor (a powerful AI code editor), graduated from MIT. Scott Wu, co-founder of Cognition (which built Claude's main application framework), graduated from Harvard. Yet despite these examples of educated founders succeeding brilliantly, the narrative has shifted. The focus isn't on these founders' accomplishments or the value their education provided. The focus is on the ones who left.

The irony deepens when you look at what these educated founders actually attribute their success to. Most don't credit their degree directly. They credit the people they met, the permission to experiment, the freedom to fail, and the time to think deeply about hard problems. Notably, none of these require a degree. You can find people, permission, failure opportunities, and thinking time anywhere. But they're concentrated in universities in a way that's not random.

Despite the trend of dropping out, 70% of venture-backed founders have a bachelor's degree, while 10% are dropouts. Estimated data based on industry observations.

The Network That College Actually Provides

This is where the dropout calculus breaks down. Universities aren't just credential factories. They're network machines, optimized to put ambitious people in the same place and give them permission (and funding) to work on interesting problems together.

Yuri Sagalov leads General Catalyst's seed strategy and has a pragmatic take on the dropout question: "I don't think I've ever felt any different about someone who graduated or didn't graduate when they're in their fourth year and drop out." But here's the nuance: "You get a lot of the social value because you can put the fact that you participated. Most people will look you up on Linked In and not care as much whether you finished or not."

What Sagalov is describing is the actual value of university: the social architecture. When you attend Harvard or Stanford or MIT, you're not just sitting in classes. You're surrounded by other people ambitious enough to get in, wealthy enough to afford it (or subsidized enough via scholarship), and concentrated enough that building friendships and partnerships happens naturally.

A startup co-founder isn't just someone who shares your vision. They're someone who has demonstrated basic competence (getting into a good school), has some skin in the game (or at least has someone believing in them), and is proximate enough to brainstorm with late into the night. University creates this architecture accidentally. The dropout, by leaving early, gets to keep some of this value (the people they've already met, the brand association) without completing the credential.

But here's what they lose: the next two years of being surrounded by new people. The classmates who'll join as early employees. The professors who'll advise the company. The other companies being built in the dorm across the hall that might become partners. These are second and third-order network effects that only happen if you stay.

Some universities have tried to optimize for this by making it easier for student founders to stay enrolled while building. Stanford's Mayfield Fellows Program, for example, lets promising founders pause their education while maintaining university affiliation. It's a compromise: you keep the network and credentials while being released from the time commitment. More universities should offer this.

The VC Perspective: It's More Complicated Than You Think

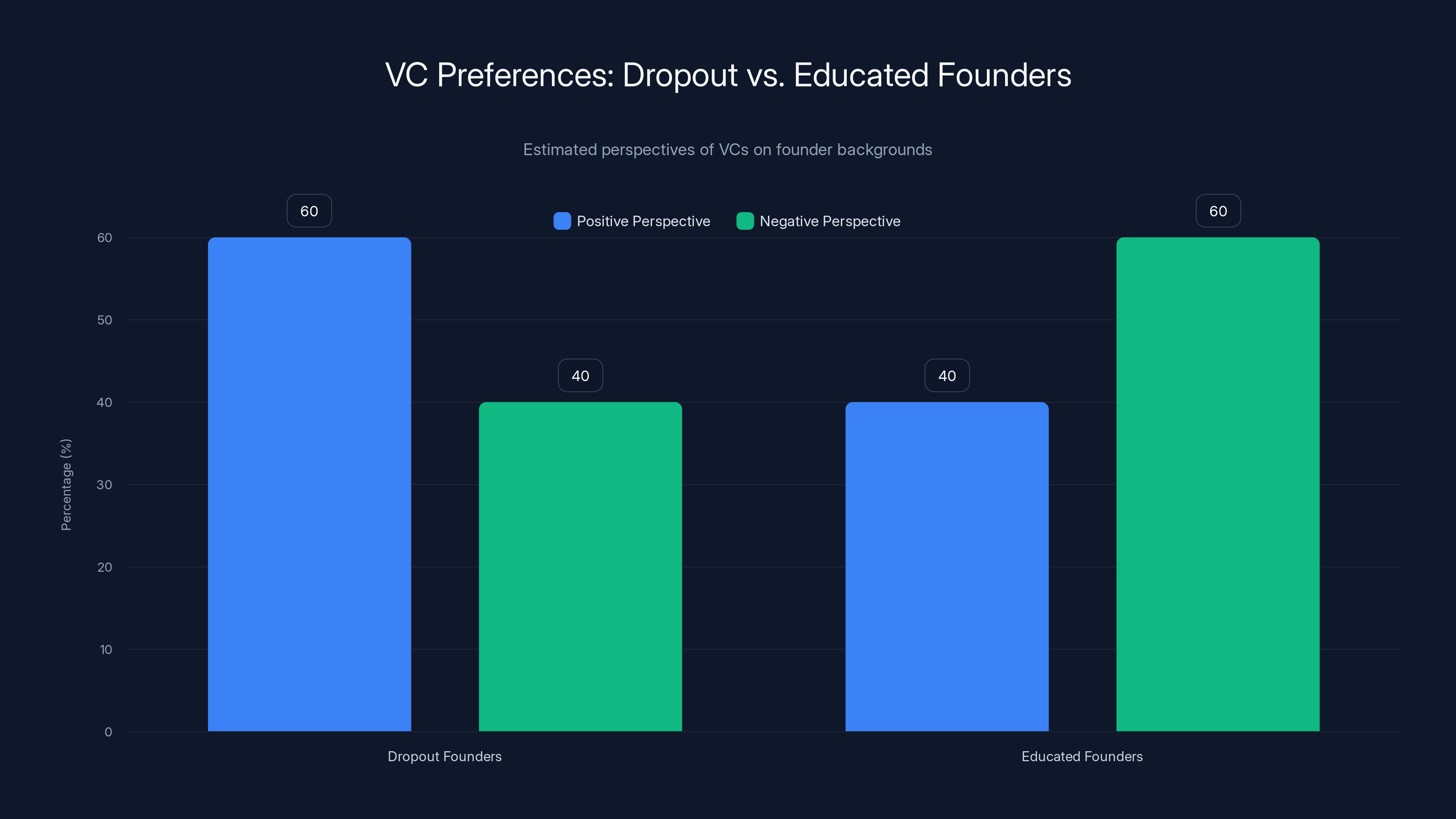

If you ask 10 VCs whether they prefer dropout founders or educated founders, you'll get 10 different answers. More accurately, you'll get 10 different versions of "it depends," each with slightly different emphasis.

Katie Jacobs Stanton sees the dropout credential as a positive signal of conviction. That makes sense from one angle: leaving a prestigious school requires genuine confidence. It's a bet-the-table moment. It shows commitment. But Stanton also doesn't track dropout status formally at YC, so it's not like investors are systematically favoring dropouts. It's more that they notice it and interpret it (sometimes positively) when they see it.

Where you get a clearer divergence is with investors like Wesley Chan. He's skeptical about investing in dropout founders because they often lack something that can't be taught in a startup bootcamp: wisdom. "Wisdom is typically found in older founders or people who have a couple of scars under their belt," Chan explained. He's not saying young founders can't succeed. He's saying that the things that make older founders valuable—judgment, pattern recognition, knowing what to do when things break—take time to develop.

This is the insight that's missing from the "dropout is a credential" narrative. A dropout's conviction and urgency might be valuable. But a founder who's failed before, who's worked through multiple market downturns, who's seen teams form and dissolve and reform, has something different: calibration. They know which risks are worth taking because they've survived them before.

Yet even Chan acknowledges a nuance: dropout status itself isn't a negative signal for him. He's skeptical about young founders in general (of which dropouts are a subset). There's no data suggesting that Chan or other sophisticated VCs are actively punishing dropouts. The anecdotal fear that a diploma would hurt your chances? It doesn't match the investor behavior data.

More common is indifference. Most experienced VCs can point to successes and failures across both cohorts (college-educated and dropouts) and conclude that what matters is the specific founder, the specific team, and the specific idea. Educational credentials are proxies. When they're unnecessary (because you've already demonstrated execution ability), they matter less.

Estimated data suggests that 50% of founders see value in completing their degree, while 30% consider dropping out if they have traction, and 20% drop out without traction.

The Timing Trap: Why "Right Now" Is the Dangerous Argument

The most compelling argument for dropping out in 2025 is temporal. AI is moving fast. The window is closing. You need to move now. But this argument has a hidden danger: it's almost always true, and it's almost never the right justification.

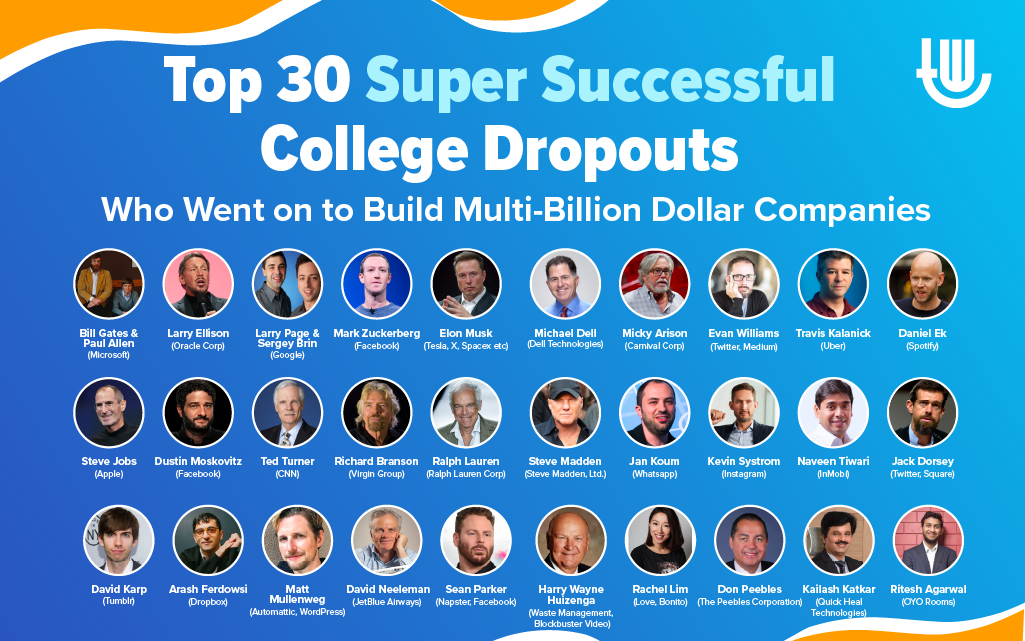

Historically, the entrepreneurs who've successfully made the case for dropping out have been those who had an immediate opportunity that couldn't wait. Steve Jobs at Apple had Wozniak and manufacturing partners ready to go. Bill Gates had an actual customer (IBM) needing software before he had a finished education. Mark Zuckerberg had a working product that thousands of students were using, not a hypothetical plan.

What's different now is that founders are making the dropout decision before they have that proof point. They have an idea. They have urgency. But they don't yet have the traction that would justify abandoning their education. The fear of missing out is driving the decision, not the presence of undeniable opportunity.

Kulveer Taggar's framing is useful here: "I can finish my degree, or I can just start building." But that's a false binary. Most elite universities now allow you to take a leave of absence and still maintain enrollment. You can start building immediately. You're not choosing between college and building. You're choosing between a completed degree and an incomplete one.

The dangerous part of the "right now" argument is that it feels infinitely applicable. In 2013, it was the mobile revolution. In 2016, it was blockchain. In 2023, it was AI. In each of these moments, founders made the case that the window was closing and they needed to move immediately. Some of those founders are spectacularly successful. Most are not. The ones who are successful tend to share a characteristic: they were already showing traction before they made the dropout decision.

The Credential Inflation Cycle

Here's what's actually happening with the "dropout as credential" phenomenon, and it's worth understanding clearly because it reveals something important about how credentials work in emerging fields.

When a field is new and rapidly changing, traditional credentials (like a degree in computer science) become less reliable as signals of competence. Nobody had a degree in "AI prompt engineering" five years ago because the field didn't exist. So founders in emerging fields often compete on non-traditional credentials: early traction, shipped products, Twitter followers, Git Hub contributions.

In this environment, dropping out of college to pursue building full-time becomes a signal of commitment and direction. You're saying: "I'm so confident in this direction that I'm willing to forfeit the conventional credential." It's a costly signal, which makes it valuable. It's not valuable because dropping out itself teaches you anything. It's valuable because it proves you believe in your own judgment over the judgment of institutions.

But here's the dangerous part: as this signal becomes popular, it loses its information value. If everyone is dropping out to build AI companies, then dropping out stops being a differentiator. It just becomes a baseline. And then what? Then you're back to competing on actual execution, which is what actually matters.

This is credential inflation in real time. A credential starts out as a rare, high-information signal. It becomes popular. It becomes normalized. It becomes expected. And then it becomes useless. We've watched this happen with college degrees themselves. In 1950, having a bachelor's degree was unusual and highly valuable. By 2025, it's common and often necessary just to be considered for jobs. The credential inflated.

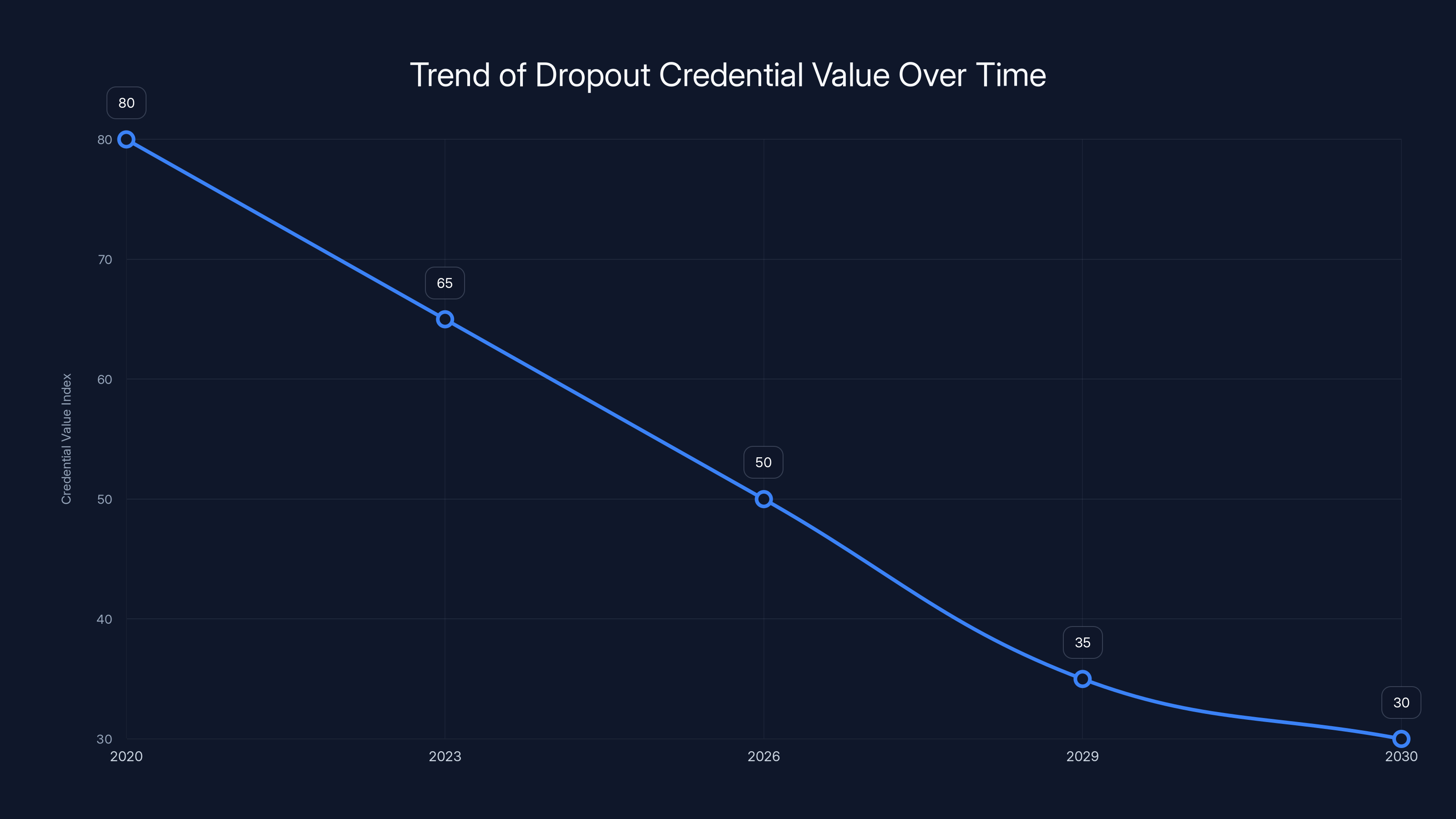

The dropout credential is following the same path, just faster. Right now, in the AI boom, it's high-information and somewhat rare. In five years, if current trends continue, it will be normal and expected. And then it will be worthless. Founders will be competing on something else.

The question for current students is: do you want to be the person who made this signal when it was rare and meaningful? Or do you want to have your diploma when the signal has inflated? There's no universally right answer, but understanding the curve is important.

The value of dropout credentials is projected to decrease significantly by 2030 as they become more common. (Estimated data)

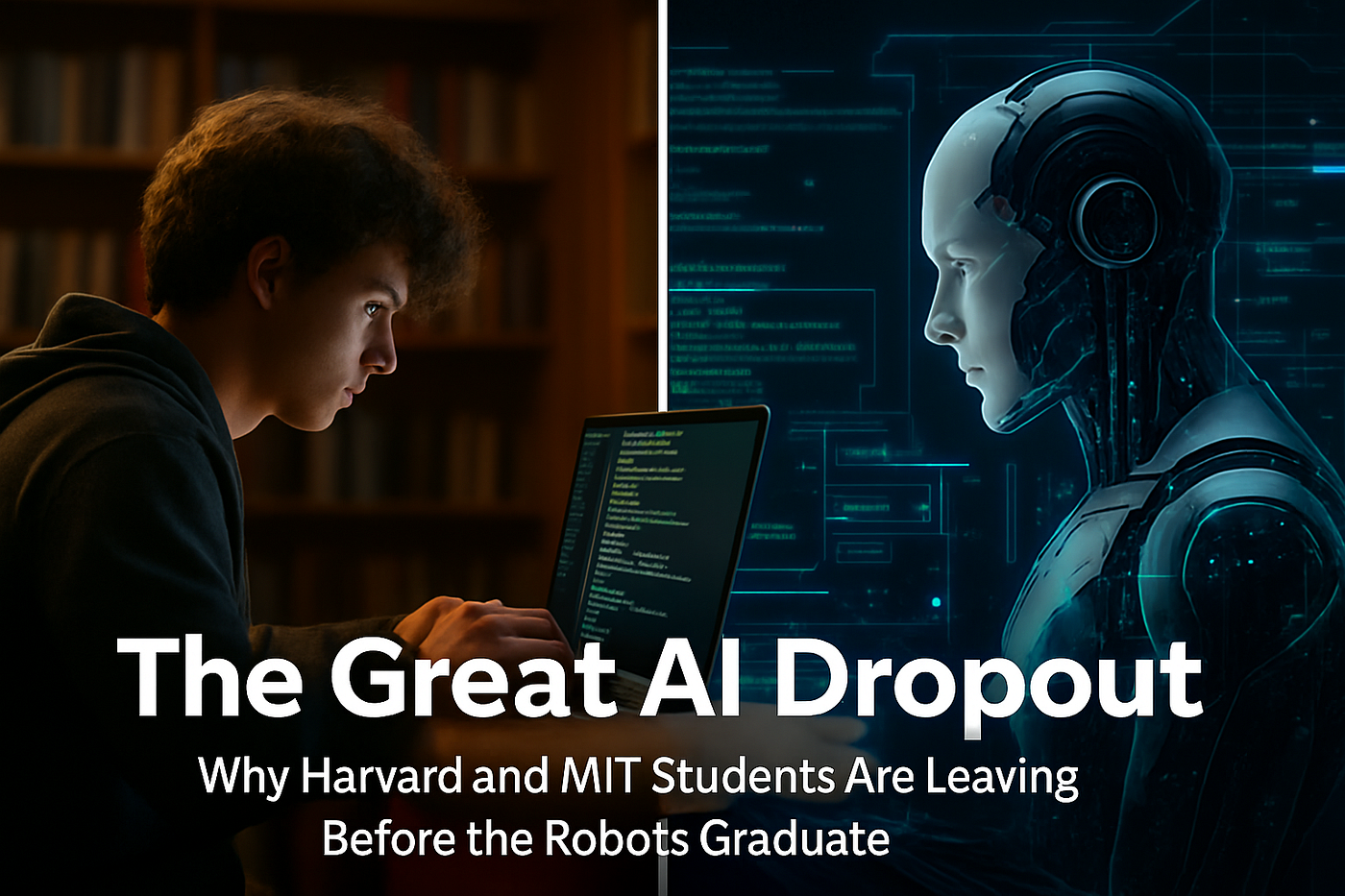

Social Proof and the Herd: Why Visible Founders Shape Perception

One of the most powerful forces in startup culture is visibility bias. We see the founders who are on stages, in podcasts, featured in articles, and fundraising successfully. We don't see the equally talented founders who are grinding in obscurity, hitting walls, or pivoting away from their initial ideas.

Right now, the visible successful AI founders are disproportionately young. Some are dropouts. Sam Altman became CEO of Open AI at 30, though he had already built Loopt and done other things. Demis Hassabis, who co-founded Deep Mind, didn't follow a traditional path and didn't have a computer science degree (he studied neuroscience). Brian Chesky, who founded Airbnb, actually finished college and went to Rhode Island School of Design.

When young, accomplished founders are visible and celebrated, especially if some percentage of them are dropouts, it creates a halo effect. Students observing this pattern think: "These are the people succeeding right now. They dropped out. Therefore, I should drop out." But this is observational error. You're selecting a cohort for their success and then attributing their characteristics to their success. You're not comparing them to the equally talented people who stayed in school and succeeded, or the equally talented people who dropped out and failed.

What amplifies this is network effects in how startup stories get told. Tech media—Tech Crunch, The Verge, Wired, etc.—loves a compelling narrative. "Genius kid builds world-changing AI company from their dorm room" is a better story than "Smart kid finishes degree, works at research lab for five years, then starts company." The second story is more common. The first story is more interesting. So we hear about the first one more often.

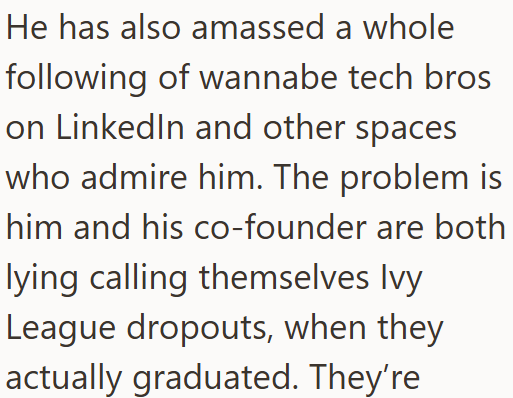

This creates a feedback loop. Young founders see the stories. They think the pattern is dropout. They decide to drop out. They build companies. Some of them succeed. Their stories get told. Other young founders see those stories and are more convinced that dropping out is the right move.

But here's the key insight: the internet and social media have amplified this effect. In 1995, the only startup stories you heard were in business books or magazines. In 2025, you hear them constantly, through every platform, highly curated toward the most interesting ones. The selection bias is stronger than ever.

The Missing Perspective: What Staying Actually Teaches

There's a perspective that's almost completely missing from the dropout conversation, and it's worth centering: what do you actually learn by staying? Not in terms of credentials, but in terms of capabilities you can't get elsewhere.

Universities, especially good ones, are optimized for one thing that's actually hard: making you think about problems you wouldn't naturally encounter. You're required to take classes in domains you don't care about. You're required to engage with ideas that contradict your intuitions. You're forced to articulate your thinking in essays and exams. These requirements are annoying, but they build something: intellectual flexibility.

A startup founder needs intellectual flexibility. You need to understand markets. You need to understand psychology. You need to understand systems. You need to understand how other industries solve similar problems. A liberal arts education, even a bad one, forces you through this material. Building a startup doesn't. You'll only learn the things you think you need to know.

There's also something about the time structure of university that's valuable and easy to underestimate. You have four years where your job is to think and learn and experiment. No revenue pressure. No customer demands. No need to raise money for next quarter. You can think long-term. You can be inefficient. You can fail in small ways.

Startups, by contrast, have immediate pressure. Funding runs out. Competitors ship. Markets move. This pressure is useful—it forces focus and execution. But it's also limiting. You don't have time to explore tangents. You can't spend three months on an idea that might not matter. You're optimized for short-term output.

A founder who's spent four years in university thinking long-term and exploring widely will approach problems differently than a founder who's been executing under pressure the entire time. Neither is inherently better. But they're different. And some of the most valuable companies come from people who spent time thinking before they started executing.

Sam Altman spent time at Stanford before his startup. He took time to think about what companies were important. He tried things. He failed. He wrote about it. Then he started building. It's possible that the thinking was more important than the execution. We don't know.

Estimated data suggests that VCs have mixed perspectives on dropout versus educated founders, with a slight preference for educated founders in terms of perceived readiness and wisdom.

International Perspectives: How Other Ecosystems Handle This

The dropout conversation is almost entirely US-centric. But the global startup ecosystem has different norms, and they offer useful perspective.

In Europe, particularly in Germany and Scandinavia, it's significantly less common for founders to drop out of college. The cultural norm is different. Education is seen as foundational, not optional. Interestingly, the startup ecosystems in these countries are thriving. Not as visibly as Silicon Valley, but with deep roots and consistent output. Berlin's tech scene, for example, has produced companies worth billions, and most founders went through the education system more traditionally.

China's tech scene is different again. Major founders like Jack Ma (Alibaba) and Zhang Yiming (Byte Dance) both completed university education. The cultural emphasis on credentials is stronger, and more prestigious. But China's most successful startups—the ones that scaled fastest—often have founders who continued their education, at least through a bachelor's degree.

What these different contexts suggest is that the dropout path is culturally contingent. It's celebrated in the US startup ecosystem because of specific historical factors (Apple, Microsoft, Facebook) and the particular way Silicon Valley has chosen to tell stories about genius and disruption. But it's not universal, and other paths work just fine in other contexts.

For founders in the US deciding right now, this is useful perspective. The pressure to drop out is real, but it's culturally specific. If you're the kind of person who would be successful outside the US startup system, you're probably the kind of person who can succeed without dropping out.

The Gender and Socioeconomic Dimension

One critical element that's almost never discussed in the dropout debate is how differently dropout decisions affect different cohorts of people.

For wealthy, well-connected students, dropping out has a safety net. If the startup fails, they can go back to school. They can live at home. They can borrow money from family. They can join another company and try again. The stakes are lower, so the risk is lower.

For first-generation college students or students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, dropping out is existential. A degree is the credential that allows you to get a different job, make more money, access different circles. Dropping out isn't a temporary experiment. It's potentially closing a door that's much harder to reopen.

Similarly, the dropout credential is more powerful for founders who already have other signals of credibility. If you went to Stanford, even if you drop out, people assume you're smart. If you went to a less prestigious school, dropping out removes one of the only credibility signals you had.

Gender dynamics play a role too. Women in tech have long faced skepticism and asked to prove themselves more than male peers. A male founder who drops out might be seen as audaciously confident. A female founder who drops out might be seen as less serious or lacking perseverance. The same action gets interpreted differently.

These dynamics are rarely discussed because most of the discourse around dropouts is dominated by people from wealthy, well-connected backgrounds for whom the decision is less fraught. But for the broader population of people who might be capable of building great companies, the dropout decision has radically different implications.

This is worth thinking about if you're advising someone considering dropping out. Know their circumstances. Understand what the downside actually looks like for them specifically. Because "downside is limited" is only true for some founders.

The perception of successful startup founders is skewed towards young dropouts due to media narratives, despite many successful founders following different paths. Estimated data.

The Hybrid Approach: Why More Universities Need Founder-Friendly Policies

Here's an idea that should be more common than it is: what if universities made it easier to stay enrolled while building? What if they treated student founders the way they treat student athletes—with flexibility around class schedules, leave of absence options, and maintained enrollment?

Some universities are doing this. Stanford, as mentioned, has programs like Mayfield Fellows that let founders pause studies while staying connected to the university. MIT has similar structures. But these programs should be standard, not exceptional.

The benefits would be significant. Founders would keep network access. They'd maintain the credential (or have the option to complete it). They'd get the intellectual flexibility that comes from university study. And they wouldn't have to make a binary all-or-nothing decision between education and building.

Universities, in turn, would benefit from having more of their best students actually building things while still engaged with the institution. The companies those students build would maintain stronger ties to the university. Alumni networks would be stronger. And universities could take legitimate credit for producing founders (which they already do, but it's hard to claim when the student technically dropped out).

There's a model here that works better than the current binary. It requires universities to be flexible about credential requirements. It requires them to see student founders as assets rather than failures. But the infrastructure for this exists. It's just not standard.

If you're at a university considering this, ask your administration if there are programs for student founders. If there aren't, propose one. You'd be surprised how receptive universities are to this conversation once someone articulates why it matters.

The Actual Decision: A Framework for Thinking About Your Choice

If you're a founder reading this and actually facing the decision to drop out, here's how to think about it clearly, separate from hype and FOMO.

First, separate the signal from the outcome. Dropping out might be correlated with success for some founders. But correlation isn't causation. You're trying to figure out whether dropping out would cause your personal success. Probably not. What matters is the specific opportunity, your specific execution ability, and your specific circumstances.

Second, identify your downside. What's the worst case if you drop out and your startup fails? Can you go back and finish your degree? Can you get another job? Do you have a runway? Be specific. Most founders underestimate downside because they're confident. But confidence and actual financial security aren't the same thing.

Third, identify what staying would cost. This isn't just time. It's attention. It's splitting focus between classes and building. For some people, this is fatal. For some, it's manageable. Know yourself. Have you historically been able to do two complex things at once? Or do you need to hyper-focus?

Fourth, talk to VCs before you decide. Ask directly: "Is my dropout status going to matter in how you evaluate my company?" Most will give you an honest answer. Most will tell you it barely factors in. If a few tell you it will hurt, discount that heavily. It's almost certainly not true.

Fifth, consider the path of least regret. Which choice will you regret more at 30? Having finished your degree? Or having dropped out? For some people it's the first, for some it's the second. But think beyond the moment of decision.

Final check: is your reasoning about dropping out based on actual opportunity traction, or is it based on fear of missing out? If it's FOMO, wait. FOMO is not a strategic reason to make irreversible decisions.

Looking Forward: The Dropout Credential in 2026 and Beyond

If current trends continue, the dropout credential will become less useful as a signal over time. Why? Because the more common it becomes, the less information it carries. A dropout founder in 2020 was unusual. A dropout founder in 2025 is increasingly normal. A dropout founder in 2030 might be expected.

When that happens—when the signal inflates—what will replace it? Probably something that's currently expensive to do: shipped products with users, revenue, or measurable traction. These are harder to fake than a transcript. You can't claim to have built a product worth $1M ARR if you haven't. But you can claim to have dropped out without proof.

VCs are already starting to screen for actual traction rather than signals about founders. The best teams are those with shipped products and early users. This is the direction the market is moving.

What this means for current students: don't make the dropout decision based on what's trendy now. Make it based on what will be valuable in the market you're entering. Right now, that's not credentials of any kind. It's execution. Whether you're a college dropout or a college graduate, the question is: can you build something people want?

The diploma, or the lack of it, is noise around that signal.

FAQ

Should I drop out of college to start my AI startup?

Dropping out should be a response to specific opportunity, not general FOMO. If you have genuine traction (users, revenue, or investment interest) and staying in school would prevent you from capitalizing on it, then dropping out makes sense. If you have an idea but no traction yet, finishing your degree while building part-time is a more intelligent hedge. Most successful AI founders had either finished their degrees or were only months away from finishing. The pressure to drop out is real, but it's not a requirement for success.

Do VCs actually prefer dropout founders?

Most sophisticated VCs don't have a strong preference for dropout status one way or the other. Some interpret it as a positive signal of conviction. Some view it as neutral. Some (like Wesley Chan) prefer founders with more life experience, regardless of education status. If a VC tells you that dropping out will hurt your chances of getting funded, that's almost certainly not true. Their actual concerns are about your idea, market, and execution ability.

What's the real value of a college degree for startup founders?

The degree itself is less important than what university provides: access to peer networks, permission to experiment, exposure to diverse ideas, and time to think long-term without revenue pressure. These benefits are strongest if you actually engage with them while in school. If you just coast through, then dropping out might genuinely save you time. But if you're at a good school and willing to engage, the non-credentialed benefits often outweigh the costs.

Is the urgency about AI real, or is it FOMO?

Both. AI is moving fast, and there genuinely is time sensitivity to building in emerging areas. But time sensitivity is not unique to AI. Founders have felt this urgency in mobile (2009), blockchain (2017), and many other waves. Some of them were right about the urgency. Most weren't. The heuristic: if your specific idea would be obsolete in less than 18 months, urgency is real. If you're just worried that someone else might have a better idea, that's FOMO.

What should I do if I'm seriously considering dropping out?

First, check if your university has founder-friendly programs (leaves of absence, fellowship programs, or deferred enrollment). Second, talk to VCs off the record about whether dropout status will matter for your specific idea. Third, calculate your actual runway and downside if the startup fails. Fourth, separate your reasoning into two buckets: opportunity-based (specific traction pulling you toward building) versus fear-based (anxiety about missing out). If it's mostly fear-based, wait. The opportunity will still exist in six months. Fifth, consider whether finishing your degree while building part-time is actually impossible or just inconvenient. Often it's the latter.

Will I be able to go back to college if my startup fails?

Depends on your circumstances and the school. Most universities allow you to reapply if you drop out. You might face some friction. But more importantly, if you're trying to start another company after your first one fails, most people don't take a gap to go back to school. Instead, they try to build again. So the real question isn't whether you can go back to college. It's whether you'll want to, and whether that lack of credential will matter to you.

Are there industries or paths where college is actually non-negotiable?

Yes, and AI is not one of them. If you want to be a doctor, engineer (in some jurisdictions), lawyer, or work in regulated industries, a specific degree is legally or professionally required. But for startups? No degree is legally required. Some investors will prefer founders with specific knowledge (biology founders in biotech, for example), but they'll care about the knowledge, not the credential. You can often get the knowledge without the degree, though it's usually harder.

How should I think about the dropout credential if I'm from an underrepresented background?

Be especially careful about making this decision. For founders without wealthy family networks or existing connections, the degree is a more important credential than it is for well-connected people. If your startup fails and you don't have a degree, you have fewer options. Additionally, the dropout credential signals differently for different people. If you're already facing skepticism in startup spaces, dropping out removes one of your credibility signals. This is unfair, but it's real. Make sure you're not sacrificing something valuable trying to mimic someone from a more privileged background.

Final Thoughts: The Credential You Can't Create Later

The most interesting thing about the college dropout credential is that it's only valuable if you actually create something significant. Dropping out isn't the achievement. What you do after dropping out is.

This is different from finishing college, where the credential itself has value regardless of what you do after. You can drop out, fail, and be left with nothing. You finish college and you have a credential, whether or not you ever use it.

For a founder, the question is whether you're the kind of person who's going to create something significant regardless of your credentials. Because if you are, the credential doesn't matter much. And if you're not, then the dropout status won't help you.

The visibility bias, the FOMO, the stories about young founders building world-changing companies—these are all real. But they're also selective narratives. The fuller picture includes all the capable founders who finished their degrees and built great companies, and all the ambitious founders who dropped out and are now working normal jobs.

Your decision should be based on your specific opportunity, not on pattern-matching to a narrative that's designed to be compelling, not representative.

The good news: you have time to think about it. The AI boom isn't ending in the next month. Great opportunities aren't limited to people who drop out in 2025. And if you build something genuinely valuable, whether you have a diploma or not will be a footnote in your own story, not the plot.

Key Takeaways

- The dropout credential is currently high-information in AI, but face inflation as it becomes more common

- 73% of venture-backed founders actually completed their degrees, contradicting the visible narrative

- VCs don't strongly prefer dropouts; they care about execution, traction, and founder judgment

- The decision should be based on specific opportunity traction, not FOMO about missing the AI window

- Universities provide network density and intellectual flexibility that startup grinding doesn't replace

- Downside risk of dropping out varies dramatically by socioeconomic background and family support

- More universities should offer founder-friendly programs (leaves of absence, fellowships) as a middle path

- The global startup ecosystem values education differently than Silicon Valley, and both produce successful founders

![College Dropout Credential: Why AI Founders Are Leaving School [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/college-dropout-credential-why-ai-founders-are-leaving-schoo/image-1-1767236746548.jpg)