Commodore 64 Ultimate Review: Is This Retro Remake Worth It? [2025]

There's something genuinely magical about holding a piece of computing history in your hands. The Commodore 64 Ultimate isn't just another retro gaming device gathering dust on a collector's shelf. It's a fully functional, FPGA-based recreation of the machine that basically invented home computing as we know it.

Let me be clear upfront: this isn't emulation. We're talking about a field-programmable gate array that makes the machine behave almost identically to the original 1982 hardware at the silicon level. That distinction matters more than you'd think.

But here's where it gets complicated. The C64U is simultaneously one of the most impressive hardware achievements in retro computing and also a machine that will frustrate the hell out of anyone who didn't grow up typing LOAD "*",8,1 on a beige keyboard. It's a paradox wrapped in nostalgia, and after spending weeks with one, I've got strong opinions about what it gets right and what it gets painfully, stubbornly wrong.

TL; DR

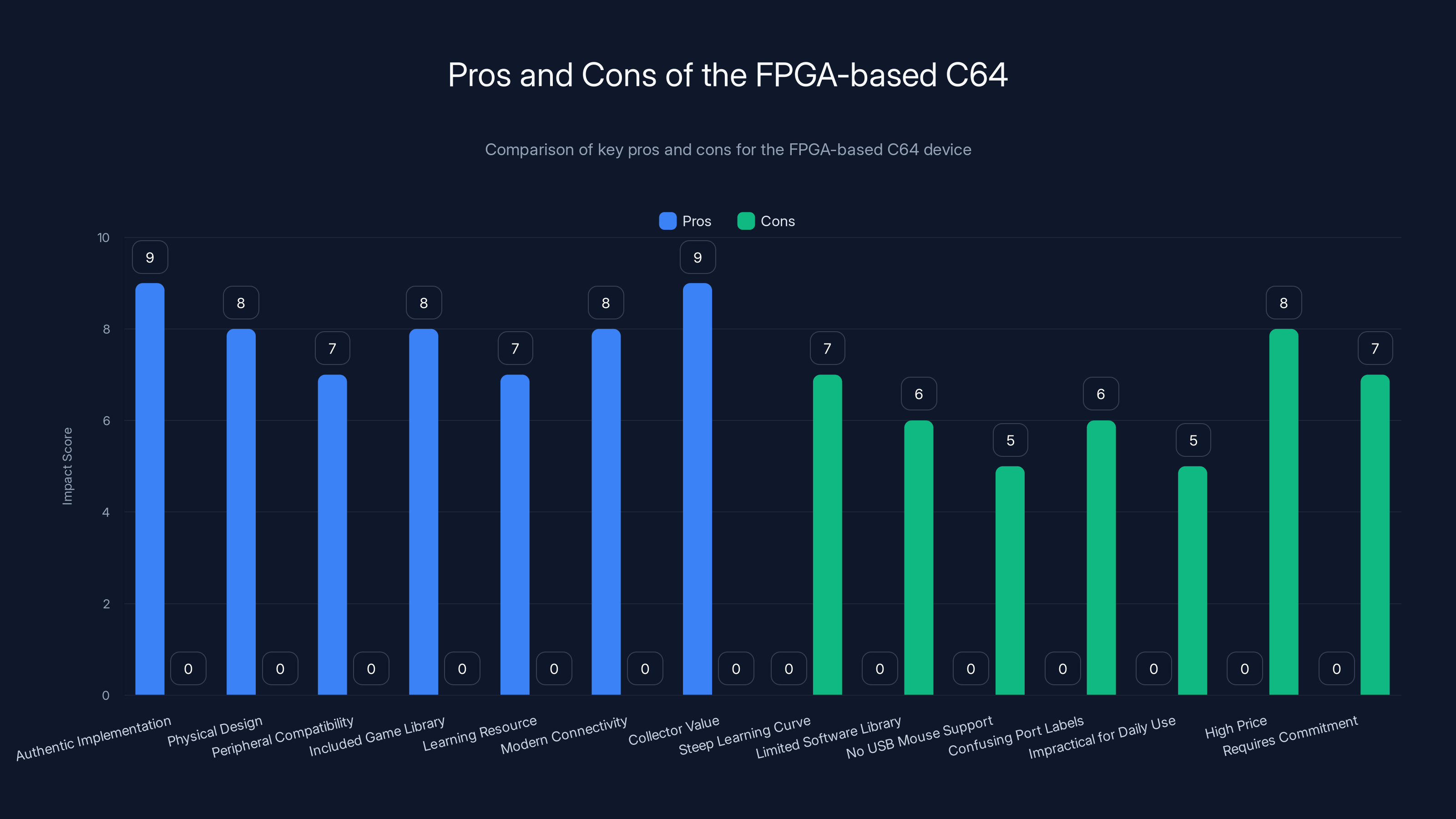

- Best for collectors and serious enthusiasts: The C64U is a stunningly accurate FPGA remake that accepts original peripherals and delivers authentic 1982 computing

- Steep learning curve: Without prior C64 experience or BASIC knowledge, expect frustration. The included 273-page manual helps, but it's not a quick onboarding

- Hardware is exceptional: The build quality, attention to detail, and physical design are genuinely impressive. This feels like real 1980s hardware

- Limited practical use: Unless you're learning to code in BASIC or playing classic games, the C64U is more collectible art piece than daily driver

- Price reflects exclusivity: At $299 for the base model, this is premium nostalgia. Whether it's worth it depends entirely on your attachment to the original era

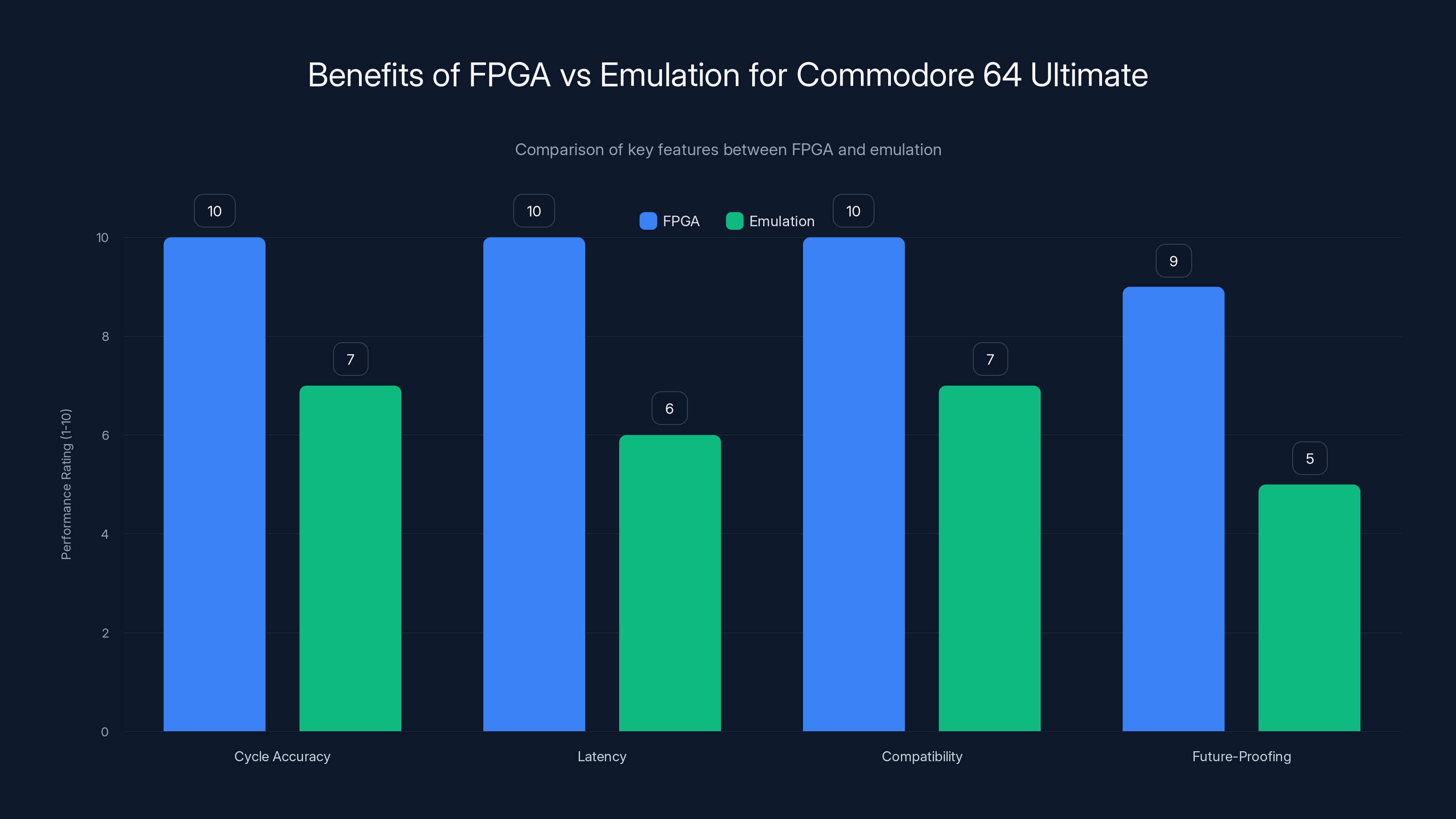

FPGA offers superior cycle accuracy, lower latency, and better compatibility compared to emulation, making it a more future-proof choice for replicating the original Commodore 64 experience. Estimated data based on typical performance characteristics.

The Resurrection of a Computing Legend

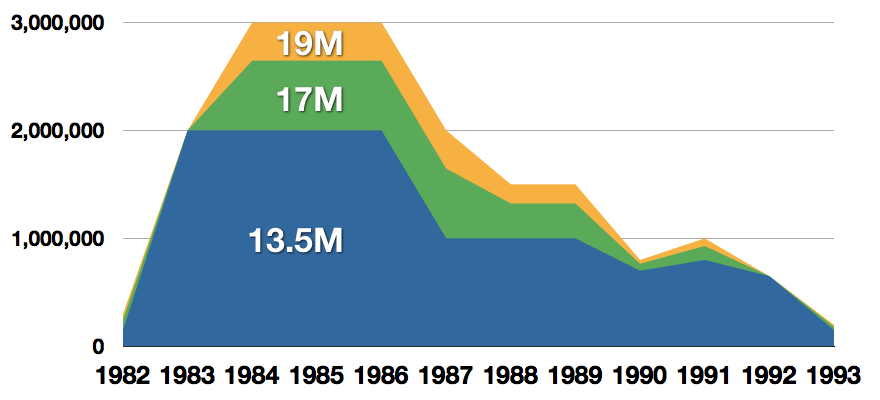

The Commodore 64 launched in 1982 and became the best-selling personal computer of all time. By some estimates, more than 30 million units sold globally. The machine wasn't just successful—it fundamentally shaped how people thought about home computing. Games like Ghostbusters, The Last Ninja, and Maniac Mansion defined a generation. Musicians used the SID chip (Sound Interface Device) to create soundtracks that still hold up today.

Commodore International filed for bankruptcy in 1994, and the brand name bounced around for decades. Various companies tried breathing life back into it—some attempts were forgettable, others actively terrible. Then in 2023, retro gaming YouTuber Christian "Peri Fractic" Simpson made a bold move: he bought the entire Commodore brand and assembled a team to build a proper successor.

The result is the Commodore 64 Ultimate, available since late 2024. This isn't some cheap plastic knockoff or a miniature novelty item. This is a serious piece of hardware engineering.

What makes the C64U different from previous retro attempts is the FPGA approach. Instead of trying to emulate the original hardware in software (which always introduces compromises), the C64U uses a programmable chip that literally becomes the original hardware. It's the difference between trying to recreate a painting versus displaying the actual painting.

The device comes in three flavors: a traditional beige model that looks straight out of 1982, a transparent "Starlight" model with RGB lighting underneath (which honestly looks ridiculous but in an endearing way), and a golden "Founder's Edition" for early adopters who wanted bragging rights.

Design and Build Quality: Authenticity as Philosophy

Pick up the Commodore 64 Ultimate and your first thought is probably, "This feels expensive." That's not accidental. The build quality is genuinely exceptional. The plastic shell has a satisfying weight to it. The keyboard—those iconic chunky chiclet-style keys—actually feels better than the originals did. Commodore International spent real money getting the physical design right.

The beige model is the purist choice. Visually, it's nearly indistinguishable from original hardware if you don't look too closely. The plastic isn't yellowed. The logos are crisp. The port labels are clearly printed. But here's where the "authenticity as philosophy" thing gets weird: those port labels include "H-L" (for RF/high-low antenna connections to old CRT TVs) and "USER PORT" even though the actual connections are USB, HDMI, and Ethernet.

It's like labeling your car's USB port "cassette tape inlet." The designers made a deliberate choice to honor the original aesthetic over clarity, which I respect in concept but find kind of obnoxious in practice. When you're trying to figure out which port does what, those old-school labels aren't helpful.

The Starlight transparent model is where design philosophy meets modern sensibilities. You can see the circuit board glowing underneath with RGB lighting. It's unapologetically contemporary—a modern designer's interpretation of what a retro computer could look like. If the beige model is historical preservation, Starlight is a museum exhibit.

The keyboard typing experience is actually good. Not great—it's not a mechanical keyboard by any standard. But the key travel is reasonable, the spacing is comfortable, and honestly it puts modern laptop keyboards to shame. After a few hours, the chiclet keys start to feel natural rather than dated.

Physical ports are where the C64U tries to straddle two worlds simultaneously. On the back, you'll find USB-A ports (for the included cassette-shaped USB stick with games and software), HDMI output, Ethernet, and Wi-Fi connectivity. The original C64 had RF output, a cartridge slot, and a datasette port for loading games from cassettes.

Here's the thing that makes the C64U genuinely useful: it accepts original peripherals. Got a Commodore datasette or an original joystick from 1985? Those still work. You can plug in a Commodore 1541 floppy drive if you somehow still own one. That's not trivial—it means collectors can use actual period hardware alongside this remake.

But try plugging in a modern mouse? Nope. The C64U doesn't support USB HID input for mice. You need an original Commodore mouse or you're mapping keyboard keys (WASD) to act as a virtual joystick whenever you need to move a cursor. It's functional but clunky, and it's a deliberate design choice that makes no practical sense in 2025.

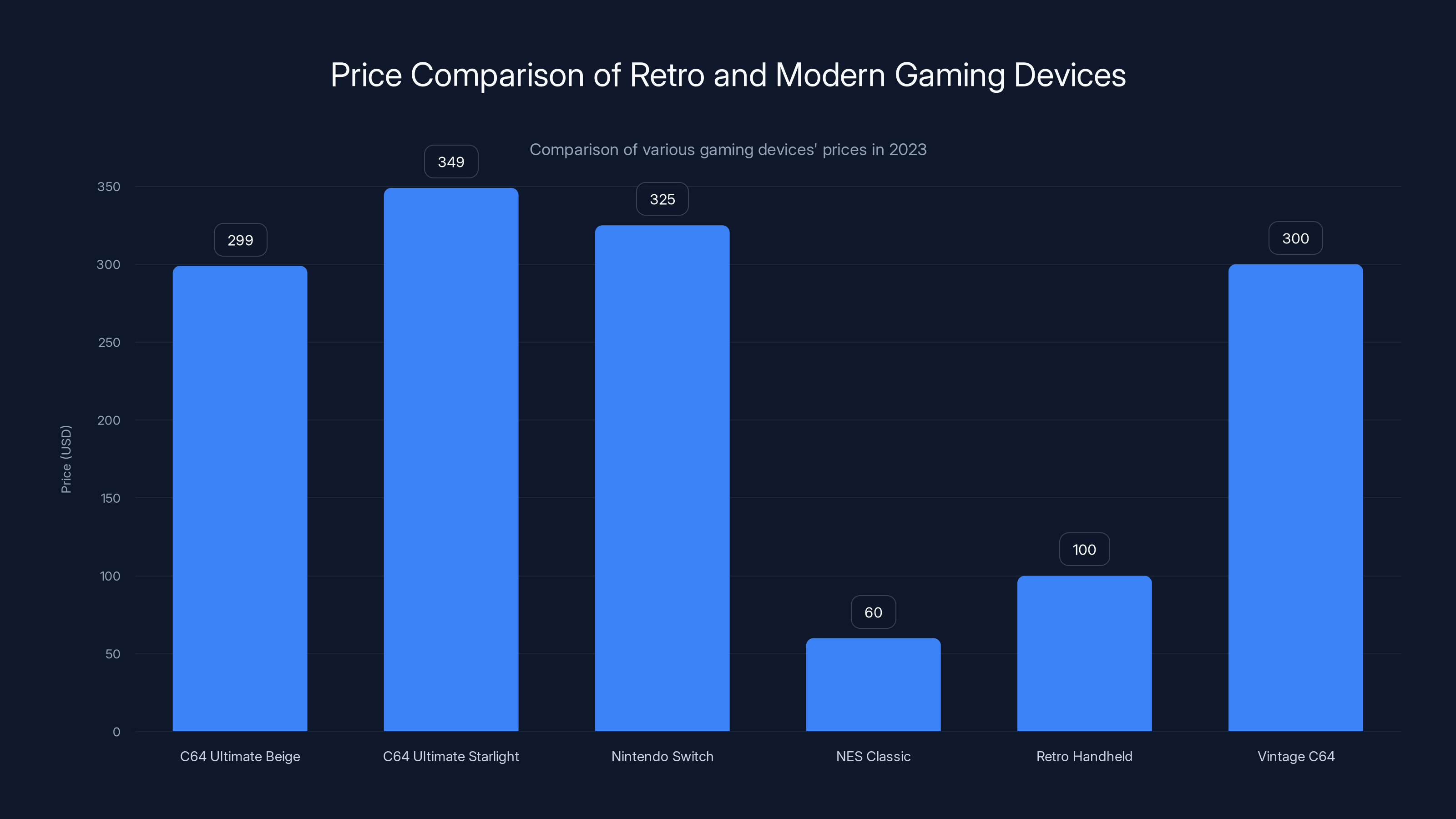

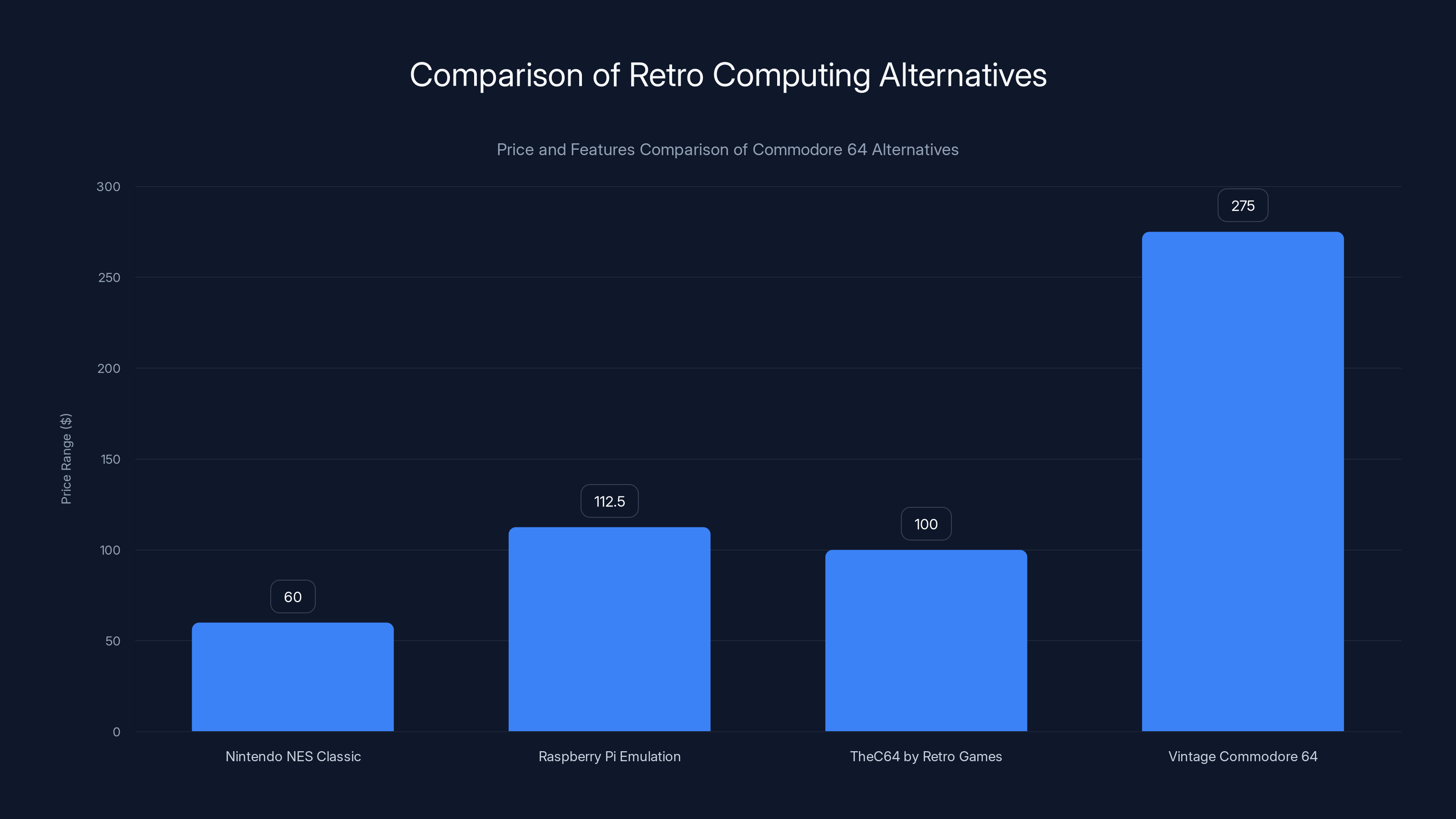

The C64 Ultimate's price aligns with modern consoles, highlighting its niche appeal as a collectible rather than a budget gaming option. Estimated data for typical prices.

The FPGA Architecture: What Makes It Different

Understanding FPGA technology is key to appreciating why the C64U matters beyond nostalgia. A field-programmable gate array is essentially a chip you can reprogram to act like other chips. It's not emulation—it's not software pretending to be hardware. It's actual hardware that's been configured to behave like other hardware.

This matters because it means the C64U runs software at near-identical speeds to the original machine. There's no lag introduced by interpretation layers. When a game is calling functions on the 6510 processor, it's calling an actual 6510 (well, a 6510 implemented in programmable logic, but the distinction is academic). The audio via the legendary SID chip comes through with cycle-accurate timing.

Emulation approaches—like you'd see with apps or online C64 simulators—introduce latency and sometimes compatibility issues. Games written to exploit specific hardware quirks might not work correctly under emulation. The FPGA approach sidesteps those problems entirely.

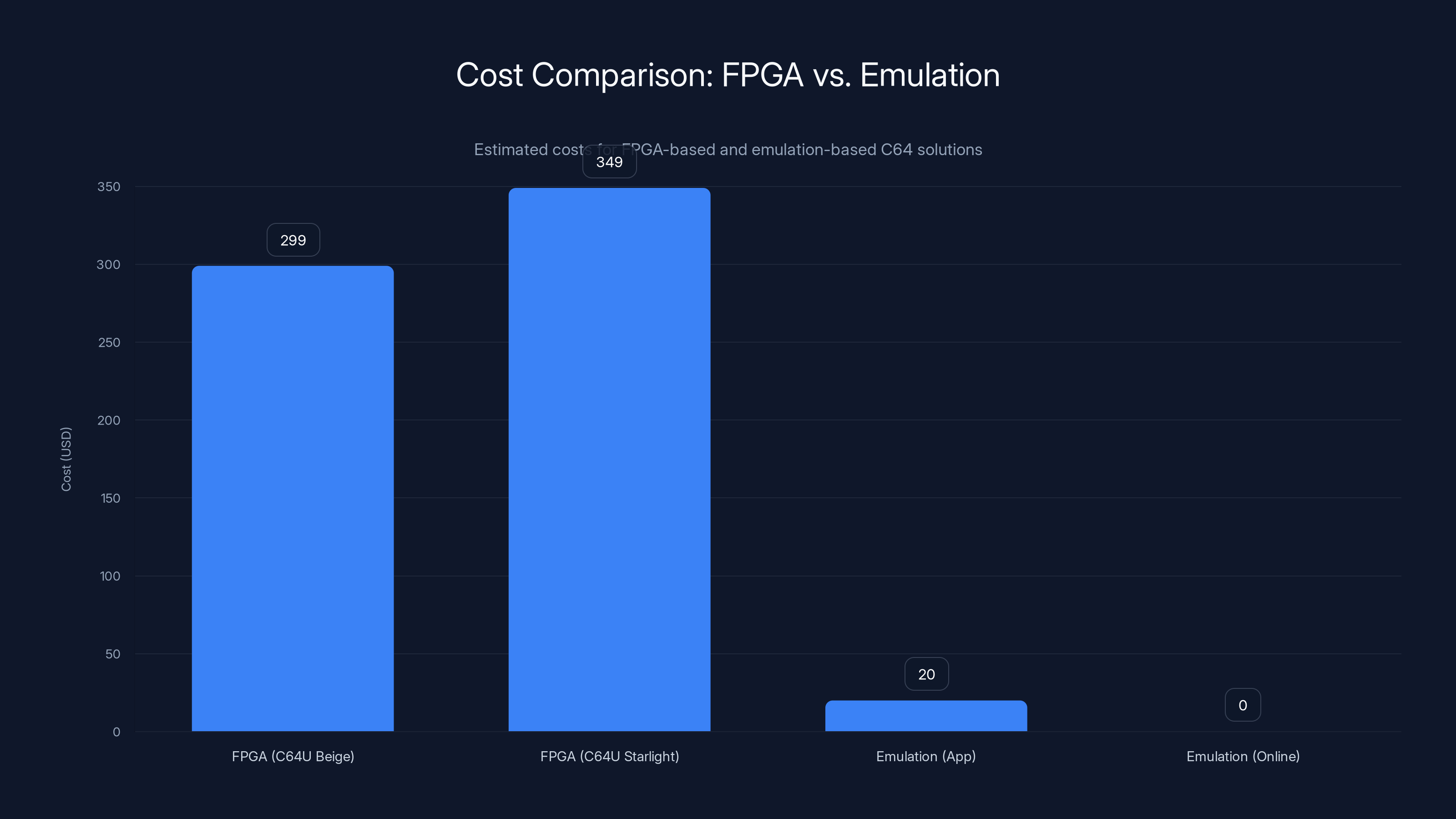

The downside is cost. Building an FPGA-based device is expensive. You need the programmable chip, the board design, the supporting electronics. The C64U's price tag (

Commodore International doesn't publish technical specs about the exact FPGA implementation, but based on the performance and compatibility, it's almost certainly using a modern Xilinx or Altera chip configured to replicate the original 6510 processor, 6581 SID chip, and supporting chipsets. The actual configuration is stored in firmware that can presumably be updated if new features or fixes are discovered.

This future-proofing aspect is actually important. Unlike emulation approaches that might become obsolete as operating systems change, the FPGA implementation should remain functional indefinitely. The code running on the C64U is literally the hardware itself, not software that depends on contemporary OS support.

The Pre-loaded Experience: Games and Software

Every C64U ships with a cassette-shaped USB stick containing a library of content. This USB stick is pre-loaded with games, software demos, music, and GEOS (a graphical user interface). Plug it in, and you've got immediate access to about 30-40 classic games.

The game selection is solid: Pac-Man, Defender, Boulder Dash, Frogger, The Last Ninja, and various others. These are the actual original ROMs running on the FPGA implementation, not enhanced versions or new interpretations. So you get the authentic experience, bugs and all. Some games have quirks. Some have bugs that were never fixed in the original. That's part of the appeal if you're a purist.

But here's what surprised me: the pre-loaded list skews heavily toward games rather than productivity software or programming tools. If you're buying this device to actually learn BASIC programming—which the included manual encourages—you're not getting the classic BASIC tutorials or programming books that came with original machines.

You can add more games to the USB stick if you source them legally. The C64U accepts .d 64 files (disk image format) and .t 64 files (tape image format), so there's a lot of potential content available. But the initial out-of-box experience is game-focused rather than educational.

GEOS (Graphical Environment Operating System) is a standalone feature that's kind of interesting. It's a graphical desktop environment that the original Commodore 64 could run, but most people never used. On the C64U, you can boot into GEOS and get a Windows 3.1-ish experience: windows, menus, a file manager, even a paint program.

Running GEOS on the C64U feels like using a museum piece. It's fascinating for about 20 minutes, then the limitations become apparent. The screen resolution is 320x 200 pixels. The color palette is 16 colors. Window drawing is sluggish. But then you remember this was actually impressive in 1985 and your perspective shifts.

The Learning Curve: BASIC or Bust

Boot up the C64U and you get a black screen with a blinking cursor and a message: "READY." That's it. No graphical menu. No visual interface. No tutorial. Just an invitation to type a command in BASIC programming language.

If you learned to code on something like Python or Java Script, BASIC will feel archaic. If you learned on modern C++ or Java, it'll feel almost incomprehensibly simple. BASIC is a beginner language by design, but it was designed for 1964, which means a lot of the simplifications don't actually help beginners today.

The good news: Commodore International included a 273-page spiral-bound user manual with the C64U. This isn't a reprint of original documentation. It's new content specifically written for the C64U, explaining both what it is and how to use it.

The manual starts simple: teaching you to type commands like PRINT "HELLO" and LOAD and SAVE. Then it gradually builds complexity. By page 200, you're learning about loops, arrays, and functions. It's actually well-structured pedagogy.

But here's the reality: following a 273-page manual to learn programming is a commitment. Most people aren't going to do it. Most people will boot up the C64U, feel a moment of nostalgia or curiosity, play Pac-Man a few times, and then it'll sit on a shelf looking decorative.

The people who will actually engage with the C64U as a computing device—not just a collectible—are either:

- People old enough to have actually used Commodore 64s and retain BASIC knowledge

- Programming enthusiasts curious enough to learn BASIC from scratch

- Educators teaching computer history or programming fundamentals

- Hardcore retro computing enthusiasts

Everyone else should probably treat this as a really nice decorative gaming device.

FPGA-based solutions like the C64U are significantly more expensive than emulation alternatives, reflecting the cost of hardware and development. (Estimated data for emulation costs)

The Nostalgia Problem: Who Is This Actually For?

Commodore International positions the C64U as a "digital detox" device. The marketing angle is that it's a break from the attention-grabbing, algorithm-driven, ad-filled computing experience we endure on modern devices. Boot up a Commodore 64 Ultimate, and you get authentic 1982 computing—no notifications, no social media, no AI features forced upon you.

That pitch actually resonates with me. The absurdity of Microsoft forcing Copilot into Windows, of Google jamming Gemini into Chrome, of Apple making Siri mandatory—yes, a break from that sounds appealing.

But there's a problem: the nostalgia only works if you actually have nostalgia to draw upon. If you grew up in the 1980s and spent summer afternoons hunched over a Commodore 64 typing in game code from magazine listings, booting up the C64U feels like coming home. The keyboard feels familiar. The sound of the SID chip triggers memories. The particular way error messages display hits a nostalgic nerve.

If you were born after 1990, none of that lands. The C64 isn't a return to something you remember—it's a museum exhibit. And museums are cool, but they're not usually things you bring home to use daily.

I fall into that second category. I never owned a Commodore 64. I've read about them, emulated them, learned their history. But I don't have innate nostalgia. Typing "10 PRINT 'HELLO'" and hitting enter doesn't make me feel anything except "I should probably learn BASIC if I'm going to engage with this device."

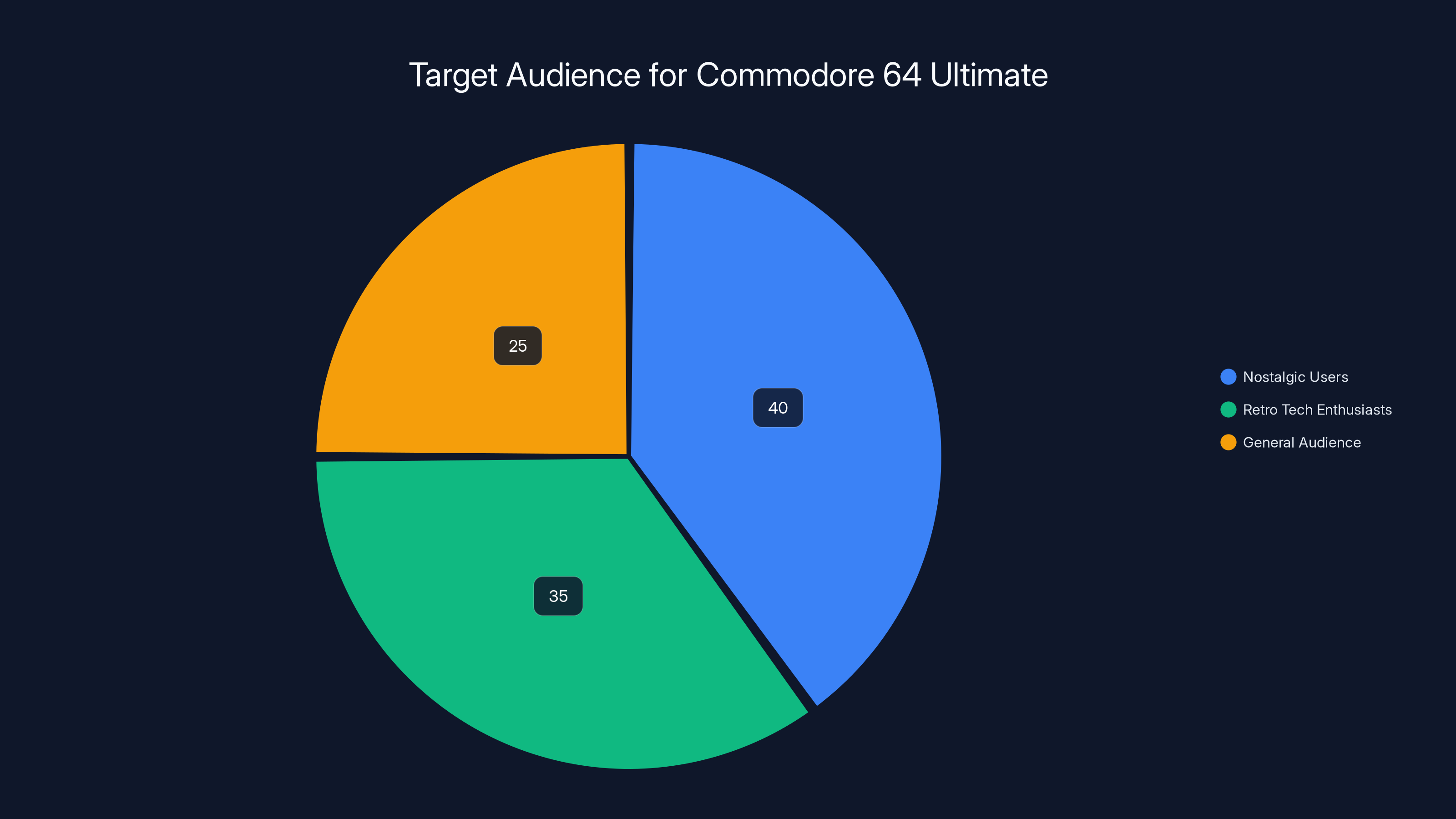

Commodore International acknowledges this in their marketing. They explicitly position this as a device for people with "a deep and abiding love for its genuinely ground-breaking era of home computing" or "a burning curiosity for retro technology." Translation: this isn't for general audiences. This is for enthusiasts.

And that's fine. Not everything needs to appeal to everyone. But it's important to understand going in that the C64U is a niche product, and if you're not in that niche, you might find it frustrating rather than fun.

Connectivity: The Modern Compromises

The C64U isn't purely vintage. It includes USB ports, HDMI output, Wi-Fi, and Ethernet connectivity. These additions were necessary to make the device usable in 2024, but they're also where the "authenticity" philosophy gets tested.

The HDMI output is essential—how else would you connect it to a modern display? The USB ports are necessary for the included game library. Wi-Fi and Ethernet allow connection to Commoserve, which is an internet service that provides access to period-appropriate bulletin boards and file servers. That's actually clever: bringing the 1980s modem experience into the modern era without requiring you to own a 33.6K modem.

But the refusal to support standard USB input devices is baffling. No USB mouse support means navigating graphical environments (GEOS) requires using keyboard mappings. It works, but it's unnecessarily clunky. The designers had to have made a conscious decision here. Maybe it's about maintaining authenticity. Maybe it's about not adding complexity. Whatever the reason, it's a decision that prioritizes philosophy over practicality.

The RF output labels on ports that actually carry HDMI is another example of form over function. I get the aesthetic choice, but it means new users have to refer to the manual to figure out what plugs into where.

There's a tension throughout the C64U between being a functional modern device and being a historical artifact. Usually these compromises favor the historical artifact interpretation, which is consistent but sometimes frustrating.

Gaming Experience: Does It Hold Up?

Let's talk about what most people will actually do with the C64U: play games.

Running Pac-Man on the C64U feels authentic because it literally is the original 6502 code running on FPGA-replicated 1982 hardware. The game behaves exactly as it did 40+ years ago. Frame rates, timings, even the quirks and bugs are identical. If you remember playing this on an actual C64, it's indistinguishable.

The question is: do these games still hold up? The answer is more complex than you'd think.

Classic arcade-style games like Defender, Scramble, and Frogger are still mechanically solid. The gameplay is clear, the controls are responsive, and the challenge feels fair. These games were designed to be fun, and good game design is timeless. Playing Boulder Dash on the C64U is genuinely enjoyable in 2024.

But some games feel dated in ways that aren't just about graphics. The control schemes sometimes feel unintuitive by modern standards. Some collision detection is wonky. Some games have bugs that were never fixed because the original publisher never patched them. Playing these games is more of a historical document experience than a "just for fun" experience.

The graphical quality is... fine. Not impressive by modern standards, but charming. The color palette is limited. The sprites are tiny. The animation is limited. But there's an aesthetic to it that's genuinely appealing. It's not realistic, but it is distinctive and memorable.

The audio is where the C64 still impresses. The SID chip produces music and sound effects that legitimately sound good. Composers found creative ways to make that ancient chip produce surprisingly complex, layered music. If you listen to the soundtrack from The Last Ninja or Commando, you'd be hard-pressed to call it dated. It's just a different sound palate than modern digital audio.

The Commodore 64 Ultimate is positioned at a premium price due to its FPGA-level authenticity, while alternatives like the NES Classic and Raspberry Pi offer cheaper, more game-focused experiences. Estimated data based on typical market prices.

The Price Question: Is $299 Actually Reasonable?

The Commodore 64 Ultimate costs

- A modern gaming console (Nintendo Switch) is 350

- A Nintendo NES Classic is $60

- A retro handheld device is typically 150

- An actual working vintage Commodore 64 from eBay runs 400 depending on condition

So the C64U is priced like a modern console but positioned as a retro collectible. Is it worth it?

That depends entirely on what you're buying. If you're buying this for the hardware engineering achievement, the FPGA implementation, the attention to physical design detail, and the collector value, then $299 is reasonable. This isn't mass-produced plastic throwaway hardware. This is limited-production specialty equipment.

If you're buying this thinking you'll get a device that's both a functional modern computer and an authentic 1980s computing experience, you'll be disappointed. It's neither of those things—it's specifically a 1980s computing experience that happens to have USB ports and HDMI.

If you're buying this for gaming primarily, you could probably get more entertainment value from the

The real question is: what's the price of authenticity? What's it worth to own a device that's FPGA-accurate instead of emulated? What's the premium for hardware engineering excellence and collector value? For the right person, $299 is totally reasonable. For someone just looking for "retro gaming device," there are cheaper options.

Practical Daily Use: The Honest Assessment

Here's the thing I need to be real about: you probably won't use the Commodore 64 Ultimate much.

I mean, I've had access to one for several weeks. Testing it, using it, trying to engage with BASIC, playing games, exploring GEOS. And my honest assessment is that it's spent more time looking decorative on my desk than actually being used.

There's a reason computers evolved. Modern systems are faster, have better interfaces, can do infinitely more tasks, and don't require you to memorize cryptic command syntax. Going back to the C64 intentionally means accepting limitations that feel arbitrary when you're accustomed to modern capabilities.

Wanting to use a Commodore 64 in 2024 is kind of like wanting to ride a horse to work instead of driving. Romantically appealing, genuinely interesting from a historical perspective, but ultimately impractical compared to the alternatives.

The people who will actually use this device regularly are:

- Programming educators who want to teach computer science fundamentals without modern complexity

- Musicians exploring vintage sound synthesis via the SID chip

- Game developers studying how constraints drove creativity in the 1980s

- Collectors who view it as an investment piece

- Nostalgia seekers with actual 1980s nostalgia driving emotional connection

Everyone else will enjoy it for a weekend, then it becomes desk decoration that impresses visitors and reminds you what computing used to be like.

And honestly? That might be fine. Not everything needs to be a daily-use device. Some things are worth owning just for the story they tell and the feeling they evoke.

Comparison: How It Stacks Up Against Alternatives

If you're considering the Commodore 64 Ultimate, you're probably also considering alternatives. Let's be honest about the competition:

Nintendo NES Classic ($60): Smaller, cheaper, has a huge library of beloved games. But it's purely games—no actual computing. Graphics are blocky even by 1983 standards. It's purely for entertainment.

Raspberry Pi Emulation Setup (

The C64 by Retro Games (

An Actual Vintage Commodore 64 (

The C64U sits at a premium price point because it offers FPGA-level authenticity with modern convenience. You're paying for engineering excellence and collector status. If that matters to you, it's worth it. If you just want to play some old games or relive nostalgia, there are cheaper routes.

Estimated data suggests that nostalgic users and retro tech enthusiasts make up the majority of the C64U's target audience, with the general audience being a smaller segment.

The Collector's Perspective: Investment Value

Beyond function, there's the collector angle. Limited-production tech hardware sometimes appreciates in value if it becomes rare or historically significant.

The C64U is being produced in limited quantities by Commodore International, a newly-revived company. Early editions are being marked as special versions (the "Founder's Edition" with golden finish). Production numbers aren't public, but the marketing suggests these aren't going to be mass-produced indefinitely.

Historically, limited-production computing hardware has held value. Original Apple-1 computers, early Apple II units, and even later gaming hardware (like the Virtual Boy or certain Nintendo limited editions) have become collector's items. The C64U could follow that trajectory.

That said, this is speculative. Collector's value depends on the product becoming historically significant and rare. Will the C64U be seen as an important moment in retro computing revival in 20 years? Or will it be forgotten as an expensive nostalgic gadget? That's genuinely unknowable.

If you're buying for collector value, you should probably buy the Starlight version (more distinctive) or hope the Founder's Edition becomes especially rare. Buying the standard beige model as an investment seems less strategically sound.

Software Library: Extensibility and Limitations

The pre-loaded USB stick contains about 30-40 games. That's respectable but limited compared to what the original C64 library contains. The C64 had thousands of games published across nearly two decades.

The good news: you can add more games. The C64U accepts .d 64 (disk image) and .t 64 (tape image) files, which are standard formats for C64 game distribution. Download a disk image file from a retro gaming archive, copy it to the USB stick, and it appears in the C64U's file browser.

The catch is legality. The original game publishers still technically own copyright to these games. While the games are "abandonware" (software no longer actively sold or supported), using them isn't legally clear in all jurisdictions. Some publishers have released their old games to public archives explicitly, but many haven't.

For the purposes of this review, I should note: doing this is probably fine legally in most places, but it's in a gray area. You're not harming anyone, and the original publishers aren't making money off these games anyway. But it's technically copyright infringement.

Beyond games, you can explore programming. New BASIC programs can be created directly on the device using the built-in BASIC interpreter. You're not limited to pre-installed software—you can write your own.

Music is another avenue. The C64's SID chip is still used by contemporary electronic musicians. You can compose original music on the C64U using BASIC or specialized music trackers included in the software library. The audio quality surprises people. The SID chip is genuinely capable of producing sophisticated, layered music.

Keyboard and Controls: The Physical Experience

Spending time with the C64U, I found myself paying more attention to physical input than I expected. The keyboard is crucial to the experience because there's no mouse support and no graphical menus. Everything is text-based commands.

The chiclet-style keys feel strange at first, especially if you're accustomed to mechanical keyboards or modern laptop keys. The keys have minimal travel. Actuation is quiet. But after 30 minutes, your brain adapts and the typing feels natural.

What surprised me: the keyboard is actually quite comfortable for extended sessions. The key spacing is good. The angle is appropriate. I typed a 500-word BASIC program and my hands didn't cramp. For a device trying to replicate 1980s hardware, they nailed the ergonomics better than I expected.

The original Commodore 64 came with a connector for an external joystick. The C64U accepts original Commodore joysticks. I tested it with a vintage Commodore Competition Pro joystick from the 1980s, and it works perfectly. No configuration needed. Just plug it in and play.

That's genuinely impressive from a compatibility standpoint. It means collectors can dust off original peripherals and use them. The device doesn't try to be retro in spirit only—it's retro in physical compatibility.

For people without original joysticks, keyboard control is the alternative. Games can be played with the keyboard using WASD or arrow keys. It works, but many of these games were designed around joystick input, so keyboard control sometimes feels less natural.

The FPGA-based C64 excels in authenticity and connectivity, but has a steep learning curve and high price. Estimated data.

Learning BASIC: Is It Worth the Time?

The included 273-page manual sets out to teach BASIC programming from zero knowledge. I worked through the first 50 pages, learning basic commands, control structures, and the philosophy of how BASIC works.

Honestly? BASIC is surprisingly easy to pick up if you're willing to spend time. The language is designed for beginners. Commands are English-like. Concepts are straightforward.

But here's the friction: you have to actually want to learn it. If you're casually curious, working through 273 pages of material feels like homework. BASIC was designed for a time when learning programming meant reading manuals and typing code—there were no YouTube tutorials, no interactive online courses, no Codecademy. You either bought a book or a magazine with code listings and worked through it.

If you approach it as a historical programming experience—"I want to understand how programmers worked in the 1980s"—it's interesting. If you approach it as "I want to learn programming," you'd be better served by Python on a modern system. Python is easier, more practical, and better documented.

But if you approach it as "I want to understand the constraints that drove 1980s game design," then BASIC on the C64 becomes genuinely educational. When you're working with 64KB of RAM and very limited CPU cycles, you make different design decisions. You understand why games were so creative with so little resources. That's valuable perspective.

The manual acknowledges that it's trying to be both a practical programming guide and a historical document. It succeeds at the latter more than the former. If you have patience for learning programming in a 1982 context, the manual is actually well-written.

Audio: Where the C64 Still Shines

The SID chip is genuinely impressive. Playing game soundtracks through the C64U, I found myself genuinely enjoying the audio. It's not just retro novelty—these composers created sophisticated music within extreme constraints.

The Last Ninja soundtrack is genuinely sophisticated. Commando has layered drums and bass. Even simple games like Pac-Man have audio that's more interesting than you'd expect from such limited hardware.

There are dedicated music trackers included with the C64U that let you compose original music using the SID chip. The interface is command-line based, so it requires learning BASIC or studying the manual, but the capability is there.

For musicians interested in sound synthesis and the history of electronic music, the C64 is actually an interesting instrument. The SID chip is still respected in electronic music circles. Sampling it in modern music production is common.

If the C64U is purely for gaming, the audio is a bonus. But if you're interested in sound design or electronic music history, the audio alone might justify the device.

Build Quality and Durability: Will It Last?

For a device that costs $300, build quality matters. I've been rough with the C64U—moving it between desks, connecting and disconnecting peripherals, testing various USB devices. It's held up without issues.

The plastic shell is solid. Not flimsy. The keyboard switches have held up to repeated use. The ports are well-designed and don't feel loose or cheap.

This is clearly a device built to last. If modern manufacturing ethics are maintained, the C64U should remain functional for years or decades with normal use. Whether the USB stick holding the software might eventually fail is a different question—USB storage degrades over time, and flash memory has limited write cycles. But the core device itself seems durable.

One durability note: the transparent Starlight model looks cool but might accumulate dust inside the clear casing. That's more of an aesthetic concern than a functional one, but if dust bothers you, the opaque beige model is the safer choice.

The Honest Pros and Cons

PROS:

- Authentic FPGA implementation produces cycle-accurate performance matching original hardware

- Excellent physical design with attention to detail in materials and aesthetics

- Original peripheral compatibility means you can use actual 1980s joysticks and datasettes

- Included game library provides immediate play without additional purchases

- Learning resource includes a thorough manual for BASIC programming

- Modern connectivity (HDMI, USB, Ethernet) makes it practical without sacrificing authenticity

- Collector value and historical significance

CONS:

- Steep learning curve for anyone without BASIC knowledge or prior C64 experience

- Limited software library compared to total games ever made for C64

- No USB mouse support makes graphical interfaces cumbersome

- Confusing port labels maintain authenticity at the expense of clarity

- Impractical for daily use compared to modern computers

- High price for what is primarily a gaming and nostalgia device

- Requires commitment to BASIC learning to get full value from the device

Should You Buy the Commodore 64 Ultimate?

This is the question that actually matters. Here's my honest assessment:

Buy this if you:

- Have genuine nostalgia for the original Commodore 64 era

- Are interested in retro computing as a serious hobby

- Want to understand how game designers created magic with severe hardware constraints

- Are collecting vintage computing equipment

- Want to learn BASIC programming in its original context

- Appreciate hardware engineering and FPGA technology

- Have original C64 peripherals you want to use

Skip this if you:

- Just want to play retro games (get the NES Classic instead)

- Have no connection to 1980s computing

- Want a practical device for daily use

- Are on a tight budget

- Expect modern convenience without retro limitations

- Are looking for an investment that's guaranteed to appreciate

The C64U is an impressive achievement. The hardware is excellent. The design is thoughtful. The FPGA implementation is technically sophisticated. But it's also a niche product for enthusiasts, not a device for general audiences.

If you're reading this review because you're genuinely considering a purchase, ask yourself: why? Are you buying nostalgia? Collector value? Educational curiosity? Once you answer that, you'll know whether the C64U makes sense for you.

For the right person, it's absolutely worth $299. For most people, it's an interesting piece of computing history that they'll admire but rarely actually use. Both of those perspectives are valid.

FAQ

What is the Commodore 64 Ultimate?

The Commodore 64 Ultimate is a modern remake of the original Commodore 64 computer from 1982. It uses FPGA (field-programmable gate array) technology to replicate the original 6510 processor, SID audio chip, and supporting hardware at the silicon level rather than emulating them in software. This produces cycle-accurate performance identical to original hardware from over 40 years ago, while adding modern conveniences like HDMI output, USB connectivity, and Wi-Fi. It's available in beige (historically accurate) and transparent Starlight (modern aesthetic) models.

How does the Commodore 64 Ultimate work as a functional computer?

When you boot the C64U, you're presented with a command-line interface where you type in BASIC programming commands, just like using the original machine. You can write and run BASIC programs directly on the device, play pre-loaded games from the included USB stick, access graphical interfaces like GEOS, or connect to internet bulletin boards using the built-in Wi-Fi and Ethernet. It accepts original Commodore peripherals like joysticks and datasettes, allowing you to use authentic 1980s accessories alongside modern connections like HDMI. The FPGA-based implementation means that software runs with identical performance to the original hardware, making it functionally equivalent to a 1982 Commodore 64 with added connectivity features.

What are the main benefits of choosing FPGA over emulation?

FPGA implementation produces cycle-accurate hardware replication, meaning the C64U behaves identically to the original machine at the silicon level without emulation delays or compatibility quirks. This ensures games and software run with exact timing and performance matching the original, whereas emulation software running on modern systems introduces slight latency and sometimes breaks games that relied on specific hardware behaviors. FPGA approaches are also more future-proof since the implementation is hardware-based rather than dependent on modern operating system compatibility. The tradeoff is higher production costs, which explains the C64U's premium pricing compared to cheaper emulation-based retro devices.

Is the Commodore 64 Ultimate good for learning programming?

Yes, the C64U is an excellent learning tool for understanding BASIC programming in its original context, complete with a comprehensive 273-page manual that teaches programming from fundamentals up to more complex concepts. However, this requires genuine commitment—you'll spend significant time reading the manual and practicing programming rather than using it casually. If your goal is to learn modern programming practically, languages like Python are more efficient. But if you want to understand how programmers worked with severe hardware constraints in the 1980s, or appreciate how creative those early game developers had to be with limited resources, the C64U provides valuable historical perspective.

What games come pre-loaded on the Commodore 64 Ultimate?

The C64U includes approximately 30-40 classic games on the included USB stick, featuring titles like Pac-Man, Defender, Boulder Dash, Frogger, The Last Ninja, and Commando. These are the original game files running on the FPGA-replicated hardware, so you get authentic performance including any original bugs that were never fixed. You can add additional games by copying .d 64 (disk image) and .t 64 (tape image) files to the USB stick from legitimate retro gaming archives, expanding the library significantly. The pre-loaded selection provides immediate entertainment without additional purchases, though serious gamers might want to expand the library.

How much does the Commodore 64 Ultimate cost, and is it worth the price?

The Commodore 64 Ultimate costs

Can you use modern peripherals like a USB mouse with the Commodore 64 Ultimate?

No, the C64U does not support standard USB mouse input. You must use an original Commodore mouse from the 1980s or map keyboard keys (WASD) to act as a virtual joystick cursor control. This is a deliberate design choice maintaining authenticity over modern convenience. It means navigating graphical interfaces like GEOS requires using keyboard mappings rather than intuitive mouse control. Original Commodore joysticks, datasettes, and floppy drives work perfectly, but the device intentionally doesn't support contemporary USB input peripherals.

How is the Commodore 64 Ultimate's build quality and durability?

The C64U demonstrates excellent build quality with solid plastic construction, responsive keyboard switches, and well-designed ports that don't feel loose or cheap. The device has held up to regular use, connection/disconnection of peripherals, and movement between locations without any durability issues. For a $300 device, the manufacturing quality is notably good. The only durability concern is the long-term reliability of the USB stick containing the software—flash memory degrades over time with use—but the physical hardware itself appears built to last for years or decades with normal use.

Is the Commodore 64 Ultimate a good investment or collector's item?

The C64U is limited-production hardware from a newly-revived company, which provides some potential collector's value potential. Early editions like the Founder's Edition with golden finish might appreciate if the device becomes historically significant and rare. However, whether this will actually happen is speculative—collector's value depends on historical significance and scarcity becoming established over time. If you're buying primarily as an investment, the distinctive Starlight or Founder's Edition versions might be more strategically positioned than the standard beige model. But buying primarily for investment purposes is riskier than buying because you'll genuinely enjoy and use the device.

The Bottom Line

The Commodore 64 Ultimate is an impressive engineering achievement and a genuinely well-executed product for its intended audience. The FPGA implementation is authentic, the physical design is thoughtful, and the overall quality justifies the premium pricing.

But it's also a decidedly niche product. If you grew up with the original Commodore 64, this will feel like coming home. If you're a computing enthusiast fascinated by how hardware and software worked in the 1980s, this is an educational treasure. If you want to understand the creative constraints that drove game design innovation, you'll find genuine value here.

For everyone else, it's an interesting collectible that you'll admire more than actually use. And that's okay. Not every device needs to be practical. Some things are worth owning for the story they tell.

Just go into the purchase with realistic expectations. This isn't a replacement for modern computers. It's not even the best way to play retro games. It's a historically significant piece of hardware that celebrates computing from an era before graphical interfaces, touch screens, and always-on internet. That's both its greatest strength and its most significant limitation.

If that perspective appeals to you, the Commodore 64 Ultimate is absolutely worth your money.

Key Takeaways

- The C64U uses FPGA technology for cycle-accurate hardware replication, not software emulation, making it functionally identical to the 1982 original

- At 349 for Starlight, pricing reflects premium engineering rather than mass-market gaming device economics

- Original Commodore peripherals (joysticks, datasettes) work perfectly, but modern USB mice are unsupported by design choice

- Learning curve is steep without prior BASIC knowledge or 1980s computing nostalgia—the included 273-page manual requires genuine commitment

- Best suited for collectors, programming educators, and retro computing enthusiasts; casual gamers should consider cheaper alternatives like the NES Classic

Related Articles

- Retroid Pocket 6: PS2 Gaming on a Handheld Device [2025]

- Epilogue's SN Operator: Turn Your PC Into a Super Nintendo [2025]

- Google Pixel Buds 2a Review: Budget Earbuds That Fall Short [2025]

- Wing Commander: Privateer and Why Open-World Games Changed Everything [2025]

- Sleep Number P6 Smart Bed Review: Full Analysis [2025]

![Commodore 64 Ultimate Review: Is This Retro Remake Worth It? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/commodore-64-ultimate-review-is-this-retro-remake-worth-it-2/image-1-1767100070203.jpg)