Wing Commander: Privateer and Why Open-World Games Changed Everything

There's a moment you have as a gamer when everything clicks. Not because a game nails a single mechanic or tells a perfectly scripted story, but because it cracks open an entirely new way of thinking about what games can be. For millions of players, that moment arrived in 1993 when Wing Commander: Privateer hit shelves. It wasn't the flashiest game ever made, and it certainly wasn't the most polished. But it did something that very few games manage: it showed us that we didn't need to follow a predetermined path. We could live in a game world instead of being dragged through it.

I'm thirty years into gaming at this point, and I realize I've been unconsciously measuring every single game I've played against how Privateer made me feel. That's not hyperbole. My gaming preferences—the reason I've logged 500 hours in The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, why I keep returning to open-world titles, why I'm obsessed with games that let me craft my own narrative—traces back to a single afternoon in the mid-1990s when I realized that the story I was telling myself in my head mattered more than the story the developers had written.

Privateer taught me something fundamental: I don't want to play through a game. I want to live in a game. That distinction changed my entire relationship with interactive entertainment, and looking at my 2025 gaming year, it's reshaped my tastes in ways I'm only now fully appreciating.

TL; DR

- Privateer pioneered the space trading sandbox before Elite Dangerous, Star Citizen, or No Man's Sky existed, blending Wing Commander's flight mechanics with open-world freedom

- The core appeal isn't the story, it's the living narrative you create yourself by exploring systems, upgrading ships, and mastering an economy

- Modern successors do individual elements better (Elite Dangerous nails simulation, Star Citizen has impressive graphics, No Man's Sky offers accessibility), but none match Privateer's character and world-building

- Open-world and sandbox games remain the most popular with players who want agency and player-driven narratives rather than authored experiences

- Thirty years later, Privateer still defines gaming preferences for players who value exploration, progression, and self-directed gameplay over linear storytelling

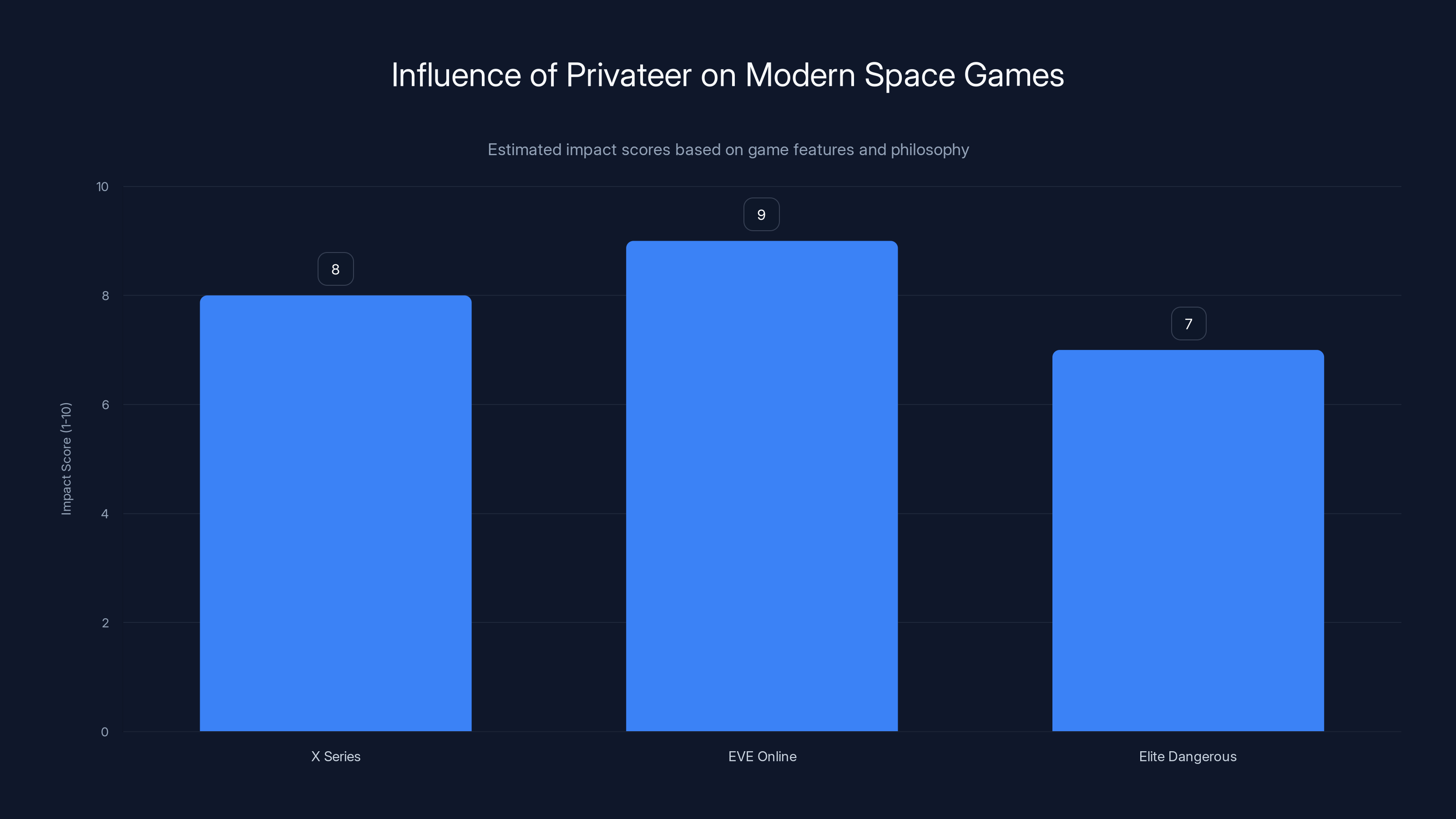

Privateer's influence is evident in the X Series' complexity, EVE Online's multiplayer universe, and Elite Dangerous' modern revival, with impact scores reflecting their philosophical alignment. Estimated data.

Understanding What Made Privateer Different in 1993

When Privateer arrived in 1993, the video game landscape looked fundamentally different from today. Most games were linear experiences. You moved from level to level, defeated bosses in sequence, watched cutscenes unfold the story, and reached the ending. That was game design. Open-world gaming as a concept barely existed. Games had levels and worlds, but the idea that you could do almost anything you wanted within that world? That was radical.

Privateer took the flight mechanics and universe that made Wing Commander famous—a story-driven military space sim—and asked a dangerous question: what if we let players ignore the story? What if the point wasn't saving humanity from alien invaders, but instead just... living your life as an independent pilot in that same galaxy?

The game gave you a ship, a small amount of starting capital, and a galaxy full of systems to explore. You could take smuggling jobs, hunt pirates for bounties, purchase upgrades for your vessel, explore uncharted systems, or just fly around looking at the beautifully rendered CG planet backgrounds. Nobody was forcing you to do anything. The story existed as an option, not a mandate.

That freedom was intoxicating. In 1993, it felt like discovering a cheat code for gaming itself.

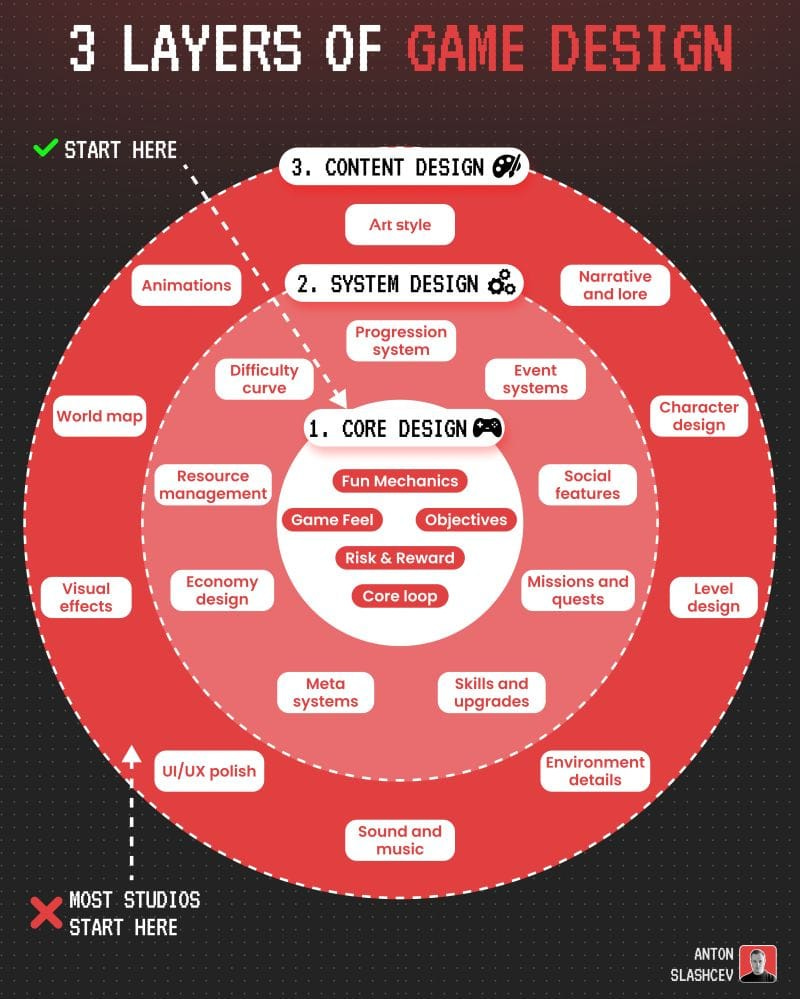

The Design Philosophy Behind Sandbox Freedom

What made Privateer's design revolutionary wasn't just that it offered freedom. It was that the freedom felt deliberate. The game made clear through its structure and presentation that the developers understood: some players want to be told a story, but other players want to participate in creating one.

The economy mattered. Ships had realistic upgrade paths. Cargo felt valuable. Your progression meant something because you earned every single advancement through your own choices and actions. You didn't unlock ships through a story progression—you earned enough credits to buy them by completing the work you chose to do.

This created a feedback loop where your success in the game felt earned rather than given. That psychological difference is crucial. When you spend ten hours saving money to afford a better targeting system, and you finally purchase it, the accomplishment feels real in a way it never would if the game simply handed it to you after a cutscene.

Why 1980s Games Like Elite Paved the Way

Privateer didn't invent this concept from nothing. Elite, released in 1984, created the template nearly a decade earlier. Elite was pure sandbox: you got a ship, some credits, and a procedurally generated galaxy. The game didn't tell you what to do. You set your own goals, pursued your own trades, and the universe just... existed around you.

But Elite had a problem: it was procedurally generated, which meant every system felt somewhat the same. The descriptions were text-based. The universe was technically infinite but also felt empty because everything was algorithmically created rather than hand-crafted by designers who understood narrative and place.

Privateer took Elite's core design and married it with Wing Commander's universe. This universe had lore, history, factions, and personality. The game had a specific setting rather than a random cosmos. Every system had distinct characteristics, different settlements with unique visual designs, and a palpable sense of place that Elite simply couldn't achieve with its procedurally generated approach.

That difference—hand-crafted world versus algorithmically generated one—proved to be the defining characteristic that made Privateer feel alive in ways Elite, despite being groundbreaking, simply couldn't match.

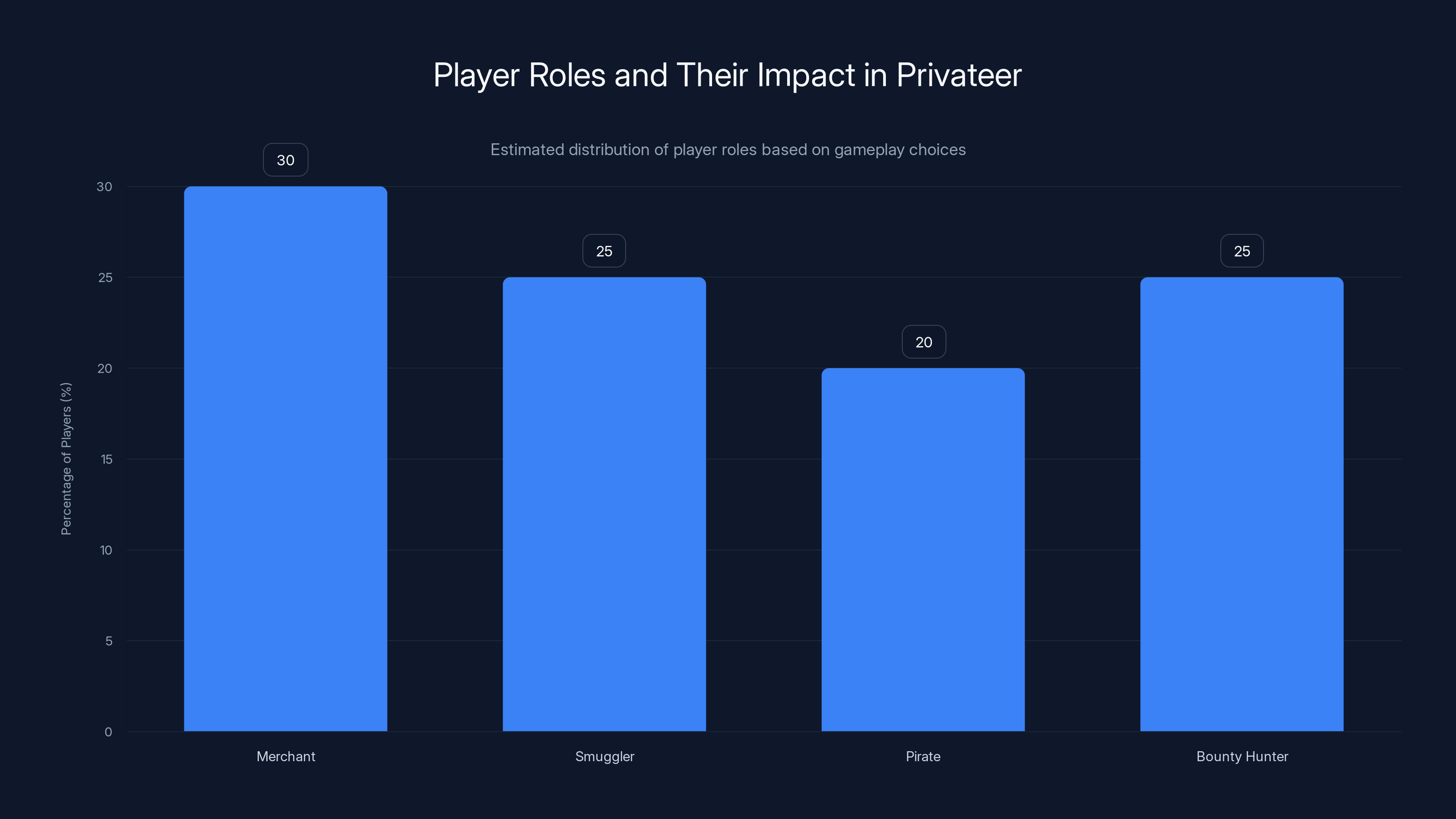

Estimated data shows diverse player roles in Privateer, with merchants and bounty hunters being the most popular choices.

The Mechanics That Made Privateer Feel Real

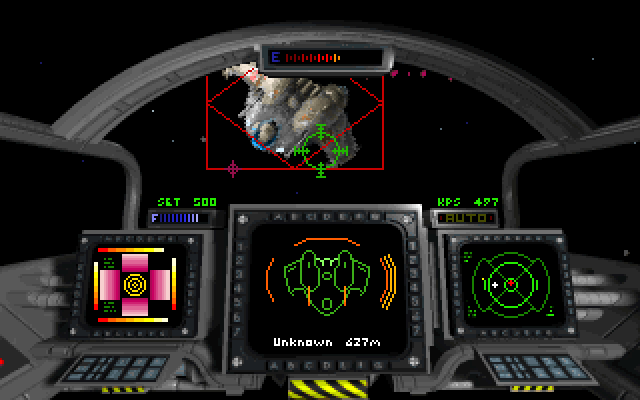

Privateer's systems were straightforward on the surface, but elegantly designed. You flew your ship between systems, landed on planets, docked at space stations, and interacted with the game world through a series of clean menus and interfaces. Nothing revolutionary from a mechanical standpoint. But the way these systems interconnected created genuine depth.

The Trading System and Player Agency

The trading economy was the backbone of Privateer's gameplay loop. You could buy goods cheap at one station and sell them for profit at another. But it wasn't a simple buy-low-sell-high simulation. The market had personality. Different factions controlled different regions. Traders had reputations. Certain goods might be valuable in one region and worthless in another.

This created meaningful decisions. Every cargo run wasn't just a transaction—it was a choice about your character's role in the universe. Were you a legitimate merchant? A smuggler willing to break laws for profit? A pirate who intercepted merchant ships? A bounty hunter?

The game didn't force you into a particular role. It just provided the tools and got out of your way. Your playstyle emerged from your choices, and those choices felt consequential because they directly affected your ability to earn credits and upgrade your ship.

Ship Progression and Personal Investment

You started in a pathetic little fighter with minimal shields and a weak weapon. Every upgrade felt like a genuine achievement. You could incrementally improve your ship, replacing weapons, upgrading engines, adding better armor. Each improvement made you slightly more capable in combat and slightly more confident taking dangerous contracts.

This created a progression curve that felt organic rather than artificial. You weren't gaining levels or unlocking predetermined items through story missions. You were earning credits through your own effort and spending them on improvements you selected yourself. The ship became an extension of your character—a physical manifestation of your choices and accomplishments.

That sense of personal investment in your vessel cannot be overstated. After thirty hours of flying the same ship, upgrading it piece by piece, it stopped being a game asset and became your ship. Losing it in combat would feel devastating because you'd invested so much time and resources into it.

The Exploration and Discovery Loop

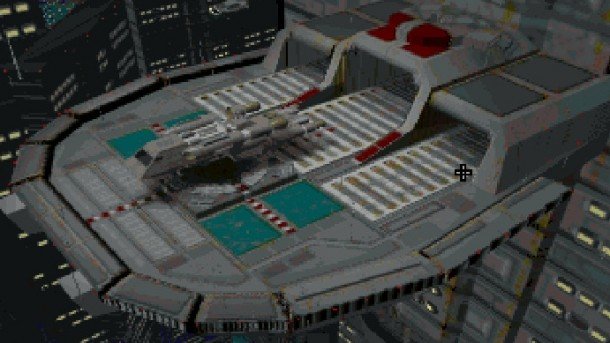

Privateer rewarded exploration in ways that most games ignored. When you jumped to a new system, you'd get a static CG rendered image of a planet, gorgeously painted and distinct from every other planet in the game. These weren't procedurally generated. Artists made them. Individual artists hand-crafted the visual aesthetic of each world.

That artistry mattered. You wanted to visit the next system just to see what it looked like. You wanted to land on planets and see the description, check the economy, see what opportunities existed. Exploration became its own reward separate from the mechanical benefits it provided.

This is subtle but important: the game recognized that humans are drawn to beauty, novelty, and discovery. Giving players gorgeous visuals and then making those visuals something they earned by exploring new space created a powerful incentive loop.

How Privateer Shaped Modern Space Gaming

Privateer didn't directly spawn a dozen successful sequels or franchises. It spawned something more important: it became a template that future developers kept returning to, consciously or unconsciously.

The X Series and European Space Sims

In Europe, developers took Privateer's template and expanded it. The X series of games, beginning with X: Beyond the Frontier in 1999, took sandbox space trading to new extremes. The X series added real-time economy simulation, NPC traders who actually bought and sold goods, dynamic factions with changing relationships, and living galaxies where the universe continued operating whether you were playing or not.

The X series became legendarily complex. You could engage with trade, combat, piracy, exploration, mining, manufacturing—the list went on. Each iteration added more depth, more systems, more opportunities for emergent gameplay. But they all owed their foundational philosophy to Privateer's insight: let players define their own role.

EVE Online and the Virtual World Approach

When CCP Games created EVE Online in 2003, they took Privateer's philosophy and adapted it for a multiplayer universe. Instead of playing against AI, you played against thousands of other players. The economy was entirely player-driven. Wars emerged from territorial disputes. Massive corporations formed with their own hierarchies and objectives.

EVE proved that Privateer's formula could sustain tens of thousands of concurrent players for decades. People didn't play EVE for the story—they played it to participate in a living universe alongside others. That's a direct evolution of Privateer's core appeal.

Elite Dangerous and the Modern Revival

When Frontier Developments launched Elite Dangerous in 2014, they essentially created a modernized version of the 1984 Elite with Privateer's philosophical approach. The game featured a procedurally generated galaxy based on real stellar data, but instead of feeling empty like the original Elite, it felt vast and explorable.

Elite Dangerous nailed the simulation aspects better than any predecessor. The flight mechanics were incredibly detailed. The economy responded realistically to player actions. The galaxy felt scientifically grounded. But what made it matter was that it inherited Privateer's understanding: give players a universe, set minimal rules, and let them find their own path through it.

Star Citizen's Ambitious Vision

Chris Roberts, the original creator of Wing Commander and Privateer, spent three decades contemplating what Privateer could have been with unlimited resources and modern technology. The result is Star Citizen, the space sim that's been in development longer than some game franchises have existed.

Star Citizen aims to realize the full potential of Privateer's vision: a first-person universe where you can walk around your ship, physically visit stations, engage in detailed professions, own property, and live a genuine life in space. Every system, every planet, every location is hand-crafted rather than procedurally generated. The ambition is staggering.

Whether Star Citizen will ever reach its full vision remains an open question, but its very existence speaks to how profoundly Privateer's philosophy impacted game design. Decades later, developers are still trying to build the perfect expression of what Privateer pioneered.

No Man's Sky and the Accessible Universe

No Man's Sky took a different approach. Rather than attempting scientific accuracy or economic simulation, it asked: what if we made Privateer's sense of discovery and exploration accessible to casual players? What if every player could immediately experience the joy of landing on a beautiful alien world?

No Man's Sky's procedurally generated universe is so vast that every player can feel like a genuine explorer. You'll never see the same planet someone else has seen unless you deliberately travel to their coordinates. That sense of personal discovery—seeing a world that's never been seen before—is pure Privateer DNA, just scaled to impossible proportions.

Starfield's Mixed Results

Bethesda's Starfield attempted to combine Privateer's sense of exploration with Elder Scrolls-style RPG depth. The game featured hundreds of planets to visit, ship customization, trading mechanics, and a universe that rewarded exploration. But it landed between two stools: it wasn't as mechanically deep as Elite Dangerous and it wasn't as personally narrative-driven as a traditional Elder Scrolls game.

Yet even Starfield's existence demonstrates the lasting influence. When Bethesda wanted to enter space gaming, they looked at what makes space games appealing, and much of what they found traced back to Privateer's foundational design decisions.

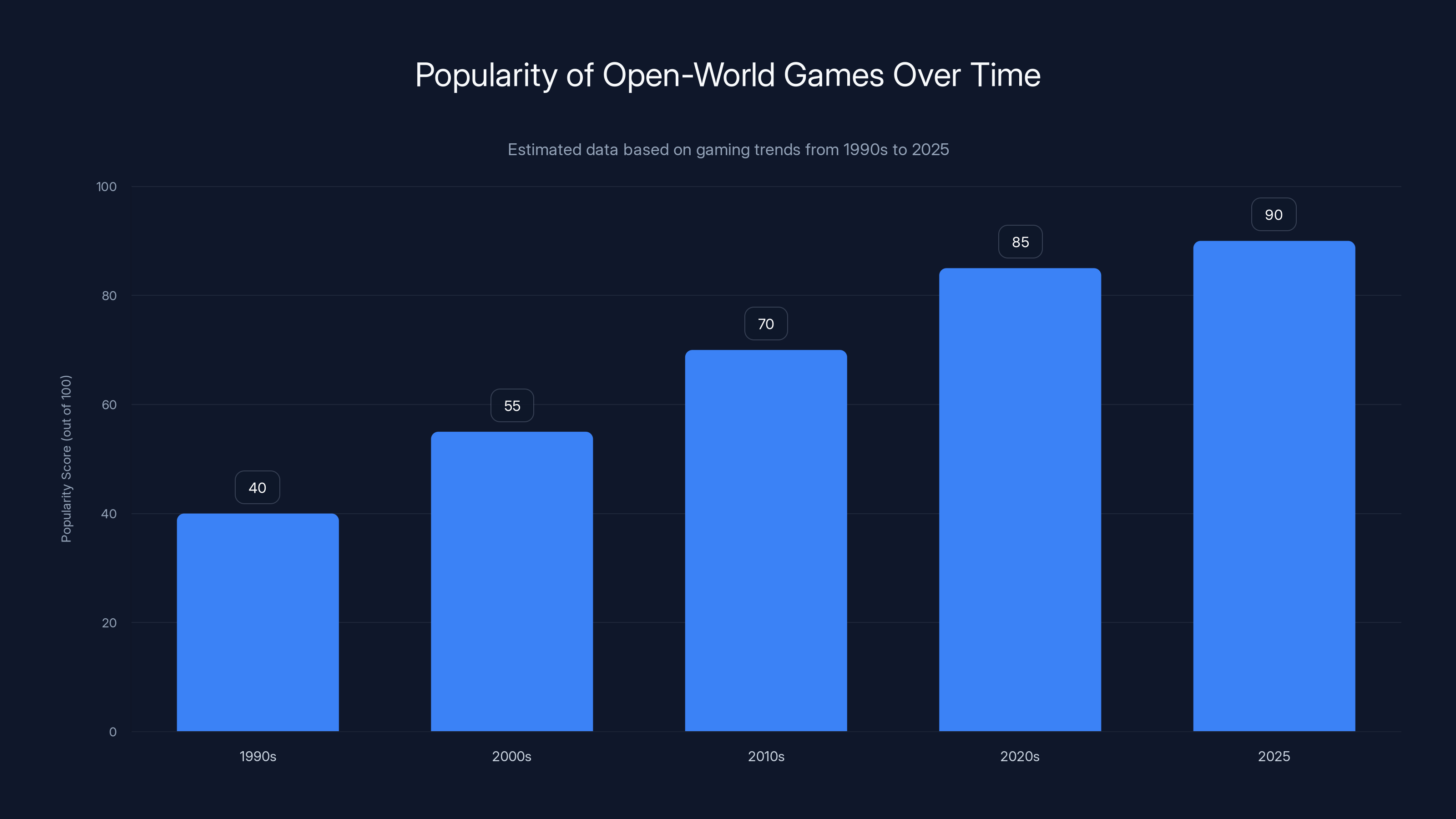

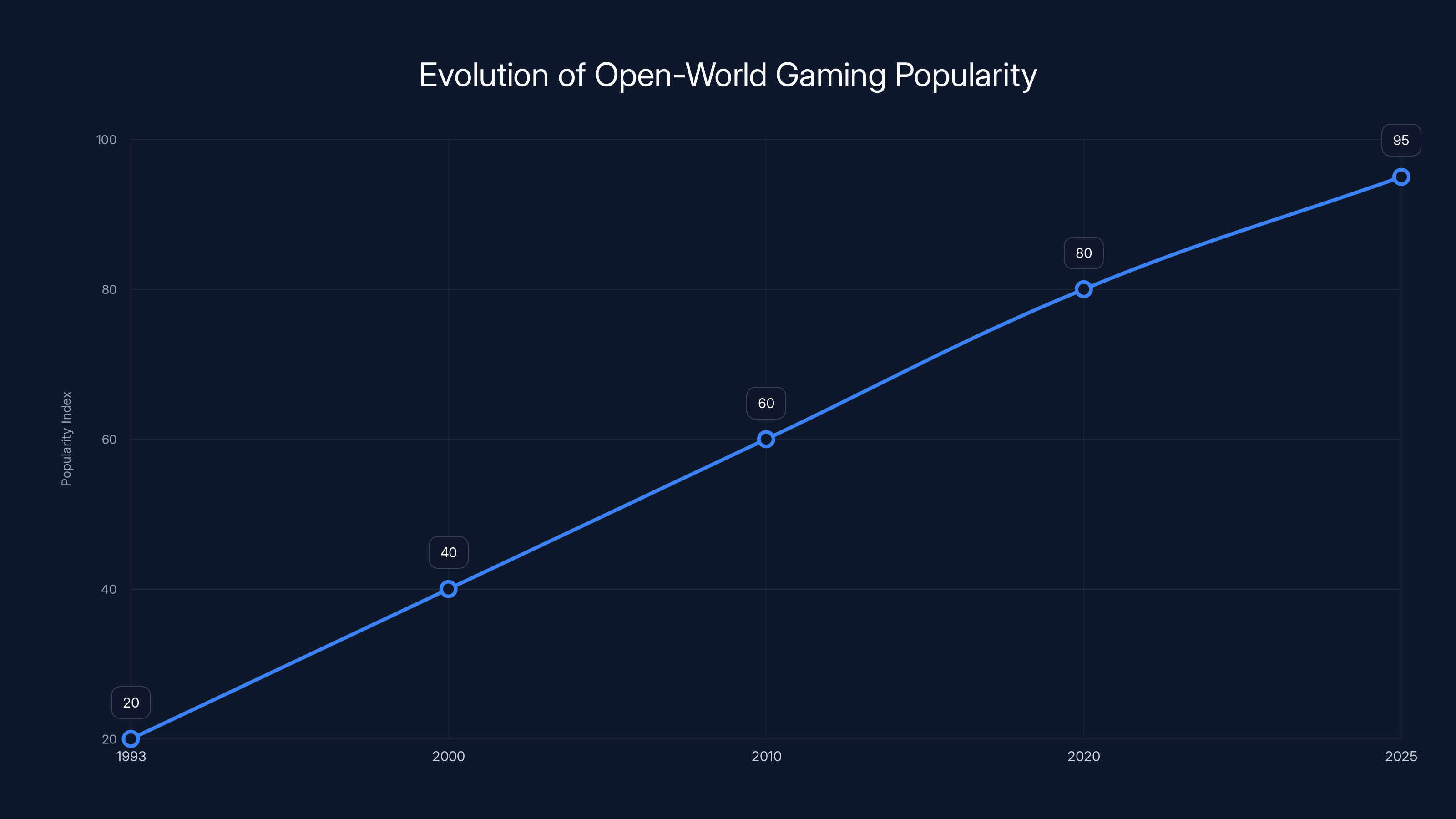

Estimated data shows a consistent rise in the popularity of open-world games from the 1990s to 2025, reflecting a growing player preference for agency and self-directed play.

Why Privateer's Setting Still Captivates Thirty Years Later

Here's what's peculiar: Privateer's graphics look ancient by today's standards. The CG renders are low-resolution. The ship models are blocky. The interface is clearly from the 1990s. By every technical measure, it should feel dated and obsolete.

It doesn't.

There's something about the visual aesthetic of 1990s computer graphics that creates nostalgia but also timelessness. It occupies an uncanny valley—it's not photorealistic, so it doesn't compete with modern games on graphical fidelity. But it's also not cartoony, so it maintains a certain gravitas and seriousness.

Moreover, the art direction of Privateer was genuinely excellent. The planet renderings captured the sense of a lived-in space opera universe. The menu interfaces looked futuristic without being incomprehensible. The ships had personality and visual identity.

The Intangible Quality of World-Building

What's remarkable about Privateer is that it created a universe with character. This isn't a procedurally generated cosmos of infinite, identical systems. This is a specific universe with specific factions, specific histories, and specific visual language.

When you landed at a station in Privateer, you weren't just docking at a generic space port. You were arriving at a specific place with a specific culture and specific opportunities. The game trusted that players would care about this distinction, and it was right.

Modern games have better technology, better graphics, better tools. But many of them fail to capture what Privateer understood: that a smaller, hand-crafted universe with personality is more compelling than an infinite, procedurally generated one without it.

Elite Dangerous has a scientifically accurate galaxy with billions of stars. But how many of those stars feel like actual places you'd want to visit? No Man's Sky has infinite worlds, but they blur together because they're all variations on the same procedural algorithm.

Privateer had maybe fifty systems, but you could remember them. You knew which ones were profitable for trade. You knew which ones had dangerous pirates. You knew which ones had beautiful planet artwork. The universe fit in your brain because it was intentionally designed rather than algorithmically generated.

Why Character Matters More Than Scale

This is the lesson game developers keep learning and forgetting: bigger doesn't automatically feel better. A smaller universe with carefully crafted detail and personality will feel more alive than an infinite one that's procedurally generic.

When modern space games try to capture Privateer's magic, many of them make the same mistake: they assume scale is what made Privateer special. They create massive galaxies and expect players to be awed. But what made Privateer special wasn't the size of the universe—it was the personality of it.

The game respected the player's time. It didn't waste you on infinite meaningless systems. Instead, every system offered something worth discovering. Every location had visual character. The universe felt like someone's vision rather than a random collection of generated content.

The Philosophy of Self-Directed Narrative

Privateer taught me something that reshaped how I think about games: the most engaging narratives in games aren't told to you, they're created by you.

Privateer had an official story. There were characters with motivations. There were factions with conflict. There were missions that advanced a plot. But all of that was optional. The game never forced you to care about the authored narrative because it understood that many players would be more engaged by the narrative they created themselves.

This is the distinction between a story game and a sandbox game. Story games guide you through a carefully controlled narrative, managing pacing and emotional beats. Sandbox games set you in a space and let you decide what matters.

Privateer understood that different players find different things compelling. Some players would engage with the official story. Others would focus entirely on trading. Others would pursue combat. Others would just explore. The game gave all of them valid ways to play.

The Emergent Narrative Approach

When you play Privateer, you unconsciously create a character. Maybe you're a ruthless merchant who'll trade in anything for profit. Maybe you're a principled trader who refuses illegal goods. Maybe you're a hotshot pilot who pursues dangerous combat contracts. Maybe you're an explorer who charts unknown systems.

None of this is explicitly encoded in the game. The game doesn't have a character creation screen where you define your role. Instead, the game structure allows different playstyles, and through your choices and play approach, you define your character.

This is emergent narrative: the story that emerges from the interaction between player agency and game structure. It's not written. It's created through play.

Modern games often try to capture this through massive branching dialogue trees and choice-driven narratives, but these create an illusion of agency rather than actual agency. You're still choosing between options the developers wrote. In Privateer, you're not choosing between predetermined options—you're choosing your actual playstyle, and the game responds accordingly.

Why This Matters for Player Investment

Here's the psychological insight Privateer intuited: players are far more invested in narratives they create than narratives created for them. When you spend thirty hours of gameplay building your character and your story, you care about it infinitely more than any story that was handed to you.

This is why Privateer players still talk about the game decades later. Not because of the authored story—many of us couldn't tell you what the official plot was if we tried. But because of the personal story we lived through the game.

I remember my ship. I remember the systems I liked. I remember the moment I finally saved enough for a major upgrade. These aren't external story beats I was told about. They're personal memories of moments I experienced while playing.

That's the secret sauce Privateer identified: make the player the protagonist of their own story, and they'll care more deeply than any cutscene could ever achieve.

The popularity of open-world gaming has steadily increased since 1993, with a notable rise in the 2000s and expected peak by 2025. (Estimated data)

What Privateer Did Better Than Its Successors

It's worth being honest about this: Privateer's successors do almost everything better from a mechanical and technical standpoint. Elite Dangerous has deeper economy simulation. Star Citizen has more impressive graphics. No Man's Sky offers better accessibility. The X series has staggering mechanical depth.

But none of them matches what Privateer achieved in the specific area it excelled at: creating a universe that felt like a place you wanted to live in, with atmosphere and character that compensated for technical limitations.

The Balance Between Simulation and Accessibility

Privateer struck a rare balance. It had enough simulation to feel real and consequential—the economy mattered, your upgrades mattered, your choices mattered. But it didn't drown in complexity the way modern space sims sometimes do.

Elite Dangerous can be overwhelming. There are hundreds of factions, millions of star systems, economic systems so complex that there are entire Discord communities dedicated to analyzing trade routes. It's incredibly deep, but that depth creates a barrier.

No Man's Sky solved the accessibility problem by making the game more action-oriented and less simulation-focused. But in doing so, it lost some of the sense that you're participating in an economy that operates independent of you.

Privateer found the middle ground. You could understand the economy without being an economist. You could become successful without mastering complex systems. The game rewarded both casual exploration and dedicated optimization.

The Visual Language of a Lived-In Universe

Privateer's art direction created a universe that felt lived-in. Every system had visual identity. The planet renderings were distinct and memorable. The stations had architectural variety. When you traveled the galaxy, you felt like you were discovering distinct places rather than variations on the same procedural template.

Modern games have better technology and higher resolution, but many of them fail to capture this sense of intentional place-building. When every station looks similar and every planet is a variation on the same algorithm, the universe feels generic regardless of how many systems exist.

This points to an underrated aspect of game design: sometimes constraint breeds creativity. Privateer had limited resources and limited polygons. This forced the artists to be intentional about visual design. Every pixel had to count. The result was a universe that's immediately distinctive.

The Pacing of Discovery

Privateer paced its discoveries beautifully. You didn't have access to the entire galaxy from the start. You had to earn enough credits and reputation to access dangerous systems. This created a natural progression of discovery.

When you finally jumped to a new region of space, it felt like a genuine accomplishment. You'd advanced enough to go there. Modern games often give you access to everything immediately, which paradoxically makes discovery feel less rewarding. If you can go anywhere, nowhere feels special.

Privateer understood that humans crave progression and unlocking new areas. By gating your access to regions through reputation and credits, the game created a sense of progression that went beyond mere mechanical advancement.

The Games That Captured Privateer's Spirit

While no game has perfectly recreated Privateer's magic, several have come close by understanding the core principle: give players agency, set them in a distinctive world, and let them define their own journey.

Freelancer: The Spiritual Successor

Chris Roberts, Privateer's creator, worked on Freelancer for Microsoft, and it inherited much of Privateer's philosophy. Freelancer focused on accessibility and story integration more than simulation, but it maintained the core idea: you're an independent pilot moving through a universe, taking contracts, upgrading ships, and writing your own story.

Freelancer is probably the most direct spiritual successor to Privateer. It refined many of Privateer's mechanics, added better graphics and more polished interfaces, and created a narrative that was actually compelling without being mandatory.

The tragedy is that Freelancer didn't get the follow-up sequels that Privateer lacked. A Freelancer 2 that took the foundation and expanded it could have been a masterpiece. Instead, Roberts moved on to Star Citizen, leaving Freelancer as a singular gem in the space gaming landscape.

The Elder Scrolls Series: Privateer on Land

The Elder Scrolls games, particularly Morrowind and Oblivion, capture something fundamentally similar to Privateer: they're worlds designed for living rather than playing through.

Morrowind especially captures Privateer's spirit. It's a hand-crafted world with distinct regions, each with personality and atmosphere. The quest markers don't point you directly to objectives—you have to actually navigate. The narrative is optional. You can ignore the main story and just live in Morrowind, exploring, trading, joining guilds, and creating your own character.

The parallel is direct: just as Privateer let you ignore the Wing Commander storyline and just live as an independent pilot, Morrowind let you ignore the Elder Scrolls narrative and just live as someone in Morrowind. Both games understood that many players find more fulfillment in self-directed exploration and progression than in following authored stories.

Stardew Valley: Sandbox Progression Without Combat

Stardew Valley applies Privateer's philosophy to farming simulation. You're given a farm and a list of possible activities. You can farm, fish, fight monsters, socialize, decorate, cook—the list is extensive. But the game doesn't mandate any specific path. You choose what to do each day based on what appeals to you.

Like Privateer, Stardew Valley creates deep engagement not through scripted narrative, but through the personal story that emerges from your choices and playstyle. Different players have completely different Stardew Valley experiences based on what they decide to focus on.

Kingdom Come: Deliverance's Simulation Depth

Kingdom Come: Deliverance captured something Privateer intuited: players want to feel immersed in a world, and immersion comes from systems that operate realistically, not from flashy presentation.

Kingdom Come removes the player of typical video game superpowers. You're not a chosen one. You're a blacksmith's son. You need to eat. You need to sleep. If you haven't trained your swordsmanship, you can't fight well. The systems simulate reality, not fantasy gaming conventions.

This creates immersion because the world operates on rules the player understands. Privateer created a similar feeling by making its economy and ship progression work realistically rather than following video game logic.

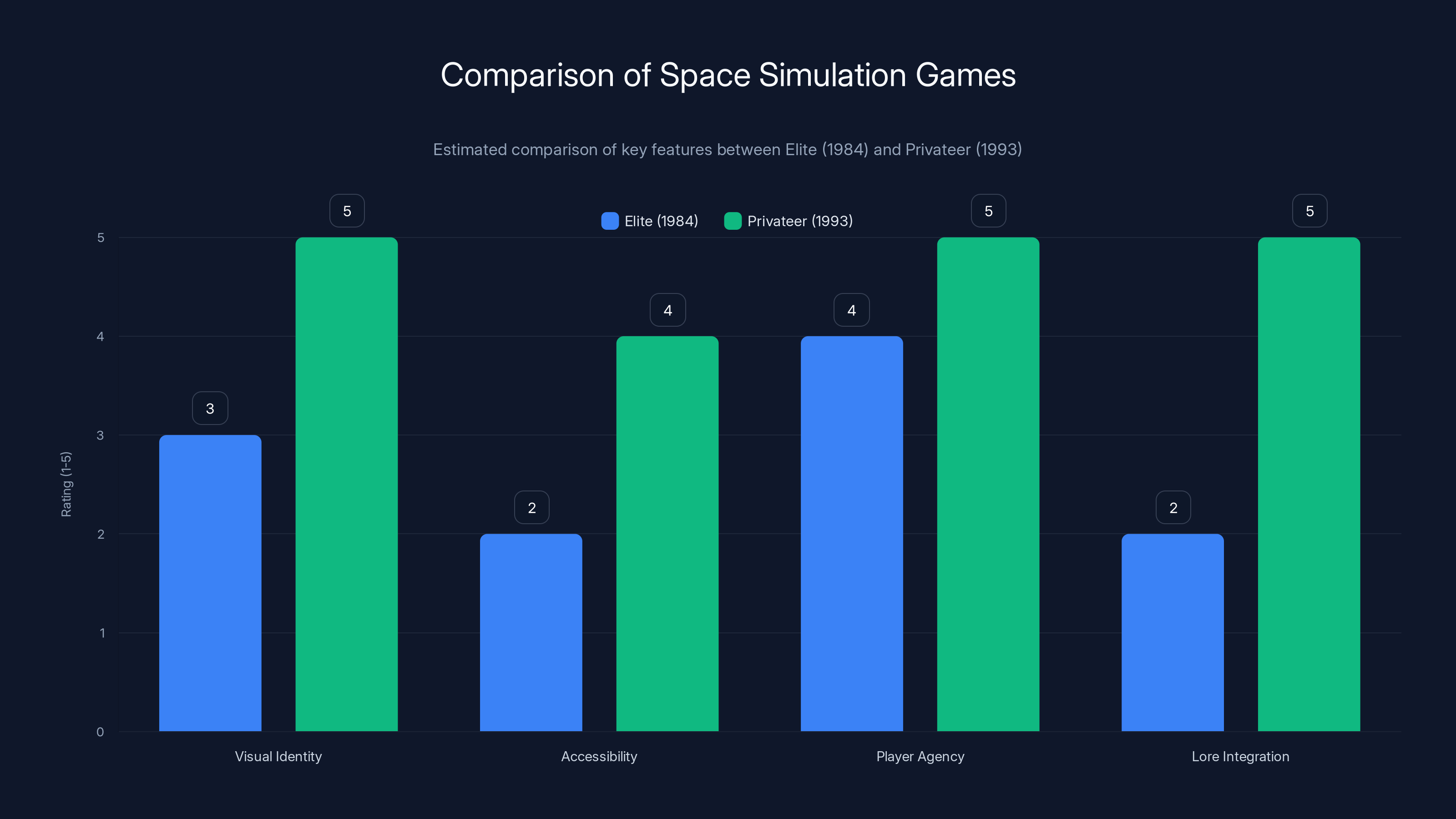

Privateer (1993) improved upon Elite (1984) with better visual identity, accessibility, player agency, and lore integration. Estimated data.

Understanding the Modern Gaming Landscape Through Privateer

Looking at my 2025 gaming year, every single game I spent significant time with shares Privateer's fundamental philosophy: they're worlds designed for living in, not stories designed for playing through.

Assassin's Creed: Shadows is a sprawling open world full of exploration opportunities. The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion Remastered is a hand-crafted fantasy world to inhabit. Lord of the Rings: Return to Moria is a mining and exploration game in Middle-earth. Morrowind is that hand-crafted world I mentioned. Tainted Grail is a narrative-focused game but structured to let you explore at your own pace.

Even the games I didn't list extensively—Civilization VII, Unreal Tournament—follow the pattern: they're frameworks for self-directed play rather than guided storytelling experiences.

This isn't a recent development. This pattern in my gaming preferences has been consistent for three decades. I gravitated toward Privateer in the 1990s, toward Elder Scrolls games in the 2000s, toward open-world titles in the 2010s, and the pattern continues into 2025.

Privateer didn't just become my favorite game. It became the blueprint against which I unconsciously measure every game I play.

What This Reveals About Player Preferences

The success of open-world and sandbox games in the modern era suggests that my preference isn't unique. Millions of players gravitate toward games that offer agency and self-directed narratives.

The most consistently successful gaming franchises in the past fifteen years have been open-world games: Grand Theft Auto, Skyrim, Dark Souls, Elden Ring, Baldur's Gate 3. When you examine what these games share, it's not cutting-edge graphics or innovative mechanics. It's the principle that players can define their own experience within the game's systems.

Privateer identified something fundamental about human psychology: when given agency and a compelling world to inhabit, people will create their own narratives and find them more engaging than narratives created for them.

The Future of Gaming: Worlds vs. Stories

The tension between world-driven and story-driven games isn't resolving. Instead, the most successful modern games are finding ways to blend both.

Baldur's Gate 3 offers a massive world with tremendous player agency, but also a narrative with clear stakes and character arcs. Elden Ring offers a minimalist story with environmental storytelling, but also complete freedom in how you engage with it. Modern open-world games try to satisfy both impulses: give players a world to inhabit and a story to experience.

But the primary appeal remains the world. Players tolerate the story because they care about the world. That's the Privateer legacy: the world matters more than the plot.

The Technical Limitations That Shaped a Masterpiece

Here's a paradox: Privateer became influential specifically because of its technical limitations, not despite them.

The game had to be small enough to fit on floppy disks. It had to run on 1990s computers with modest memory and storage. These constraints forced designers to be intentional about every element. You couldn't afford to create a thousand pointless star systems. You had to make fifty systems that each meant something.

This constraint bred creativity. The CG planet renderings were technically simple, but artistically distinctive. The interface was clean because complexity would bloat the file size. The economy was simple enough for players to understand but deep enough to be engaging.

Modern developers have unlimited technical resources. We have terabytes of storage, gigabytes of RAM, and processing power that makes 1990s computers look like calculators. This allows unprecedented scale and detail, but it can also lead to bloat.

The best modern games are those that understand that constraint breeds design clarity. Indie developers often create games more compelling than AAA titles because they're forced to prioritize what matters. Privateer operated under similar constraints, and it taught a lesson that still applies: intentional design beats unlimited resources.

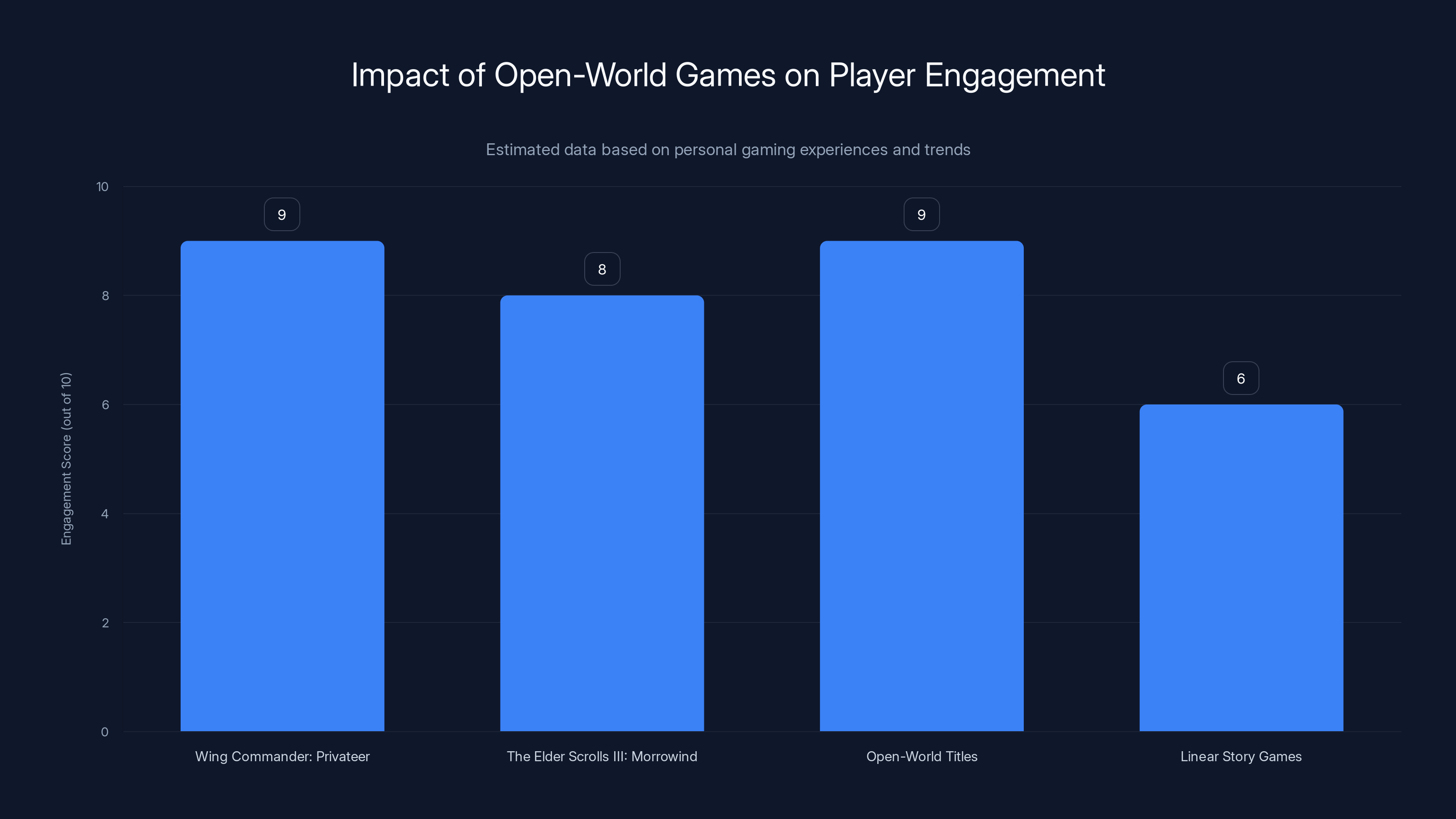

Open-world games like 'Wing Commander: Privateer' and 'The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind' have high engagement scores, reflecting their impact on player preferences. Estimated data.

Revisiting Privateer: Does It Hold Up?

I didn't play Privateer seriously from the 1990s until recently. When I revisited it, I discovered something interesting: the game holds up far better than I expected.

Yes, it looks ancient. The graphics are primitive by modern standards. But the core experience remains engaging. Flying between systems and exploring new worlds is still fun. The economy still requires thought and strategy. The sense of personal progression through ship upgrades remains rewarding.

What surprised me was how much the game's age actually enhances the aesthetic experience. The CG planet renderings have a specific visual charm that modern photo-realistic graphics don't capture. There's an elegance to the interface design that modern UI, for all its functionality, sometimes lacks.

But the game is also clearly a product of its time. The story missions are dated and occasionally confusing. The learning curve is steeper than modern games manage. There's friction and frustration that contemporary design has smoothed away.

The Nostalgia Question

This raises an interesting question: am I enjoying Privateer because it's genuinely good, or because I'm nostalgic for it and for the era it represents?

I don't have a clean answer. Nostalgia definitely plays a role. The visual style triggers genuine pleasure because of associations with my childhood and earlier gaming years. But the mechanical experience of playing the game is engaging independent of nostalgia.

Take away the nostalgia and I still think Privateer is a well-designed game. It wouldn't compete with modern space sims on technical or mechanical grounds. But it would still be recognized as a game with a clear vision and intentional design that created something meaningful.

The interesting question is how future players—those without nostalgia for the 1990s or the original games—will experience Privateer. Will it feel like a historical artifact or a timeless experience?

My guess is that different players will experience it differently. Some will see Privateer as the foundation from which later games evolved. Others will struggle with the interface and gameplay after playing modern titles. But those willing to engage with it on its own terms might discover what made it important: the realization that games could be spaces for living in rather than stories being told to you.

What Modern Games Can Still Learn from Privateer

Three decades have passed since Privateer's release, and developers have created games with incomparably more technical sophistication. Yet many modern games don't understand lessons Privateer mastered.

Intentional World Design Over Procedural Scale

Many modern games default to procedural generation for scale, assuming that infinite variety equals engaging content. Privateer demonstrates that a smaller, intentionally designed world with personality can be more engaging than an infinite procedurally generated one.

This doesn't mean procedural generation is bad. No Man's Sky proves that procedural worlds can create genuine discovery and engagement. But they work best when the procedural generation operates within intentionally designed systems and visual language.

The lesson: bigger doesn't equal better. Intentionality beats scale.

Player Agency as Primary Design Goal

Privateer made player agency the primary goal rather than a secondary feature. Everything in the game supported the player's ability to define their own experience. Modern games often treat agency as a feature to add rather than a foundational principle.

When player agency is foundational, everything else follows. The story becomes optional because the player's own story is the real narrative. The economy matters because the player needs it to progress. The world feels alive because you're living in it rather than playing through it.

Feedback Loops That Create Investment

Privateer created feedback loops where players invested time resulted in meaningful progression. You spent hours earning credits. You spent those credits on upgrades. Those upgrades made you more capable, which made future objectives easier, which made you want to take on harder objectives.

This creates a treadmill, but a treadmill that feels rewarding rather than exploitative. Modern games often create feedback loops designed to maximize engagement metrics rather than maximize player satisfaction. Privateer's loops were designed to create meaningful progression in service of the player's goals.

The Underrated Power of Place

Privateer understood that humans care deeply about place. Each system in Privateer felt like a location you were visiting rather than a menu option you were selecting. The art direction, the descriptions, the available opportunities—they all combined to create a sense of place.

Modern games often fail to create place. They create environments, but these environments feel generic and interchangeable. The most successful modern games—Baldur's Gate 3, Elden Ring, Morrowind—are those that understand that place matters. The world should feel like somewhere specific, not just a generic fantasy landscape.

The Enduring Appeal of Self-Directed Gaming

I've spent three decades unconsciously seeking games that recreate what Privateer made me feel. That's not nostalgia. That's not a quirk. That's a genuine preference for games that treat me as the protagonist rather than an audience member.

Wing Commander: Privateer arrived at a specific moment in gaming history, when open-world design was still nascent and most games were guided linear experiences. It proposed a radical alternative: what if we let players decide what matters?

Thirty years later, that question still drives the most engaging games. The most successful games of 2025 are those that understand what Privateer understood: players will create richer narratives than designers can script. Players will find more meaningful progression than designers can mandate. Players will care more deeply about worlds they inhabit than stories they're told.

Privateer didn't invent this principle—games have always been spaces for playing. But Privateer articulated it clearly, demonstrated it convincingly, and influenced everything that came after.

I'm not sure I'll ever find a game that perfectly captures what Privateer made me feel in 1993. Technology has advanced too far. Aesthetic preferences have shifted. I'm older now and play differently. But every game that approaches that feeling, every game that offers a world rather than a story, every game that respects player agency and self-directed narrative, is carrying on Privateer's legacy.

That legacy isn't about a single game from 1993. It's about a philosophy: that the best games aren't ones that tell you who to be and what to do, but ones that give you the tools and the world and let you decide for yourself.

That's what Privateer taught me. That's what I've been looking for ever since.

FAQ

What is Wing Commander: Privateer exactly?

Wing Commander: Privateer is a 1993 space simulation game developed by Origin Systems that combines the flight mechanics and universe of the Wing Commander series with open-world sandbox gameplay inspired by Elite. Instead of following a military storyline like mainline Wing Commander games, Privateer puts you in control of an independent pilot who can choose to trade, explore, hunt bounties, or pursue missions on their own terms.

How did Privateer differ from the original Elite game released in 1984?

While Elite pioneered the space trading sandbox formula with a procedurally generated galaxy, Privateer improved upon it by adding hand-crafted systems with personality, clear visual identity for each location, and integration into an existing fictional universe with lore and history. This meant every system felt like a destination worth visiting rather than another variation on an algorithm. Additionally, Privateer paired the sandbox with polished flight mechanics from the Wing Commander series, creating a more accessible experience than Elite's steeper learning curve.

Why is Privateer considered influential if later games improved on its mechanics?

Privateer's influence stems not from individual mechanical innovations but from its demonstration that games could offer worlds for living in rather than stories for playing through. The game proved that player agency and self-directed narratives could be more engaging than scripted storytelling. Nearly every major space game since Privateer—from Freelancer to Elite Dangerous to Star Citizen—borrowed this fundamental philosophy. Many games improved individual systems, but few matched Privateer's holistic design and sense of place.

What makes a sandbox game more engaging than a story-driven game?

Sandbox games like Privateer create what designers call emergent narratives: stories that emerge from the interaction between player agency and game systems rather than being scripted. When you spend dozens of hours earning credits to upgrade your ship, that investment creates genuine emotional attachment. You're not following someone else's story; you're creating your own. This creates deeper engagement because players care more about narratives they create than narratives created for them.

How do modern games like No Man's Sky and Star Citizen compare to Privateer?

Modern successors have improved upon Privateer's individual elements. Star Citizen has more impressive graphics and detail. Elite Dangerous has deeper economy simulation. No Man's Sky offers better accessibility and visual variety. However, none of them fully recapture Privateer's specific combination of accessibility, intentional world design, engaging feedback loops, and distinctive sense of place. Each succeeds in some areas while sacrificing others that made Privateer special.

Is Wing Commander: Privateer still playable today?

Yes, Privateer was re-released with Windows compatibility through GOG in 2011. The graphics look dated, but the core gameplay loop remains engaging. The learning curve is steeper than modern games manage, and some mechanical friction that contemporary design has smoothed away remains. However, for players interested in gaming history or the roots of modern space sims, Privateer remains accessible and playable. Whether it will appeal to players without nostalgia for 1990s PC gaming is a question each player has to answer for themselves.

What do the most popular games of 2025 have in common that connects to Privateer?

The most consistently popular games of 2025—including The Elder Scrolls IV Oblivion Remastered, Baldur's Gate 3, and Elden Ring—all prioritize player agency and self-directed gameplay over authored storytelling. They create worlds designed for inhabiting rather than stories designed for playing through. This principle traces directly to Privateer's philosophy that players find more meaningful narratives when they create them than when they follow them. The enduring success of open-world and sandbox games demonstrates that what Privateer intuited decades ago remains a core source of gaming engagement.

The Philosophy of Games as Living Spaces

Privateer arrived at a moment when the gaming industry was still learning what games could be. In 1993, the dominant paradigm was guided narratives: linear progression through levels, scripted story beats, designer-controlled pacing. Privateer proposed something radical: what if we gave players a world and got out of their way?

This philosophy—treating games as spaces to inhabit rather than stories to consume—has become increasingly relevant. As game budgets have grown and development teams have expanded, the temptation to create more controlled, authored experiences has only increased. Yet the most successful games consistently demonstrate that players will find more meaning in self-directed experiences.

The question Privateer posed—what if we trust players to find their own meaning?—remains fundamentally important. And the answer it demonstrated—they absolutely will—remains profoundly true.

Key Takeaways

- Wing Commander: Privateer pioneered the space sandbox formula by giving players agency instead of forcing authored narratives, a design philosophy that shaped three decades of gaming

- Hand-crafted worlds with personality consistently outperform procedurally generated ones because intentional design creates place and meaning that algorithms cannot

- Emergent narratives created by players through their choices are more engaging than scripted storytelling because players care deeply about narratives they create themselves

- Modern space sims like Elite Dangerous and Star Citizen improved individual mechanics but struggle to recapture Privateer's specific combination of accessibility, world-building, and distinctive character

- Open-world and sandbox games remain the most popular gaming genres because they follow Privateer's fundamental insight: players want to inhabit worlds, not play through stories

Related Articles

- Xbox Game Pass & Gift Cards: Best Deals [2025]

- Why iPhone 17 Succeeded But Apple Must Upgrade the Base Model [2025]

- Watch Christmas Movies Anywhere with a VPN [2025]

- Best Currys Boxing Day Tech Deals 2025: Save Up to 40% [January]

- Luna Ring Gen 2 Review: Smart Ring Features and Performance [2025]

- Ricoh GR IV Review: The Pocket Camera That Changed Street Photography [2025]

![Wing Commander: Privateer and Why Open-World Games Changed Everything [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/wing-commander-privateer-and-why-open-world-games-changed-ev/image-1-1766758218345.png)