How One Director Is Proving AI Belongs in the Hands of Artists

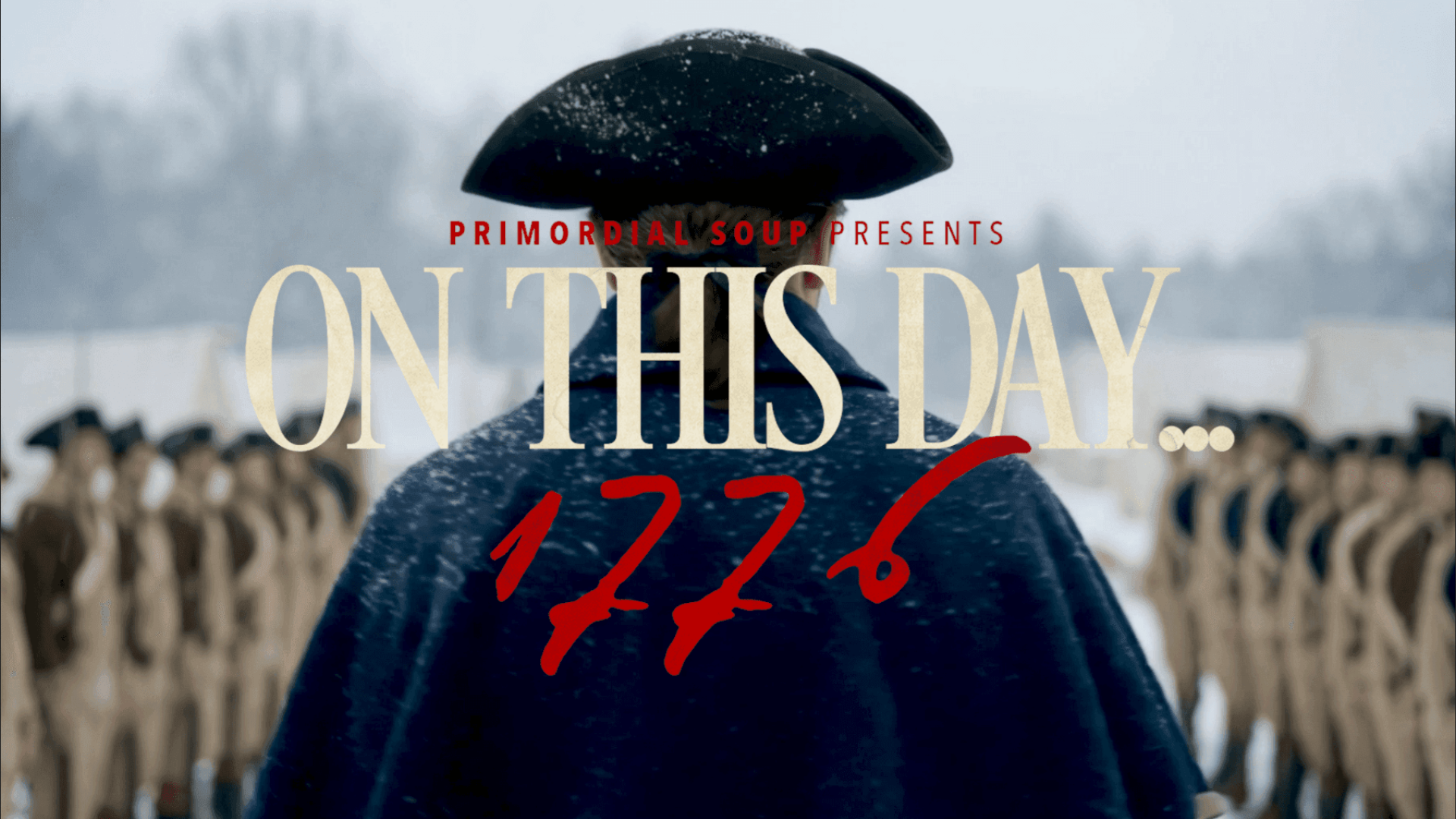

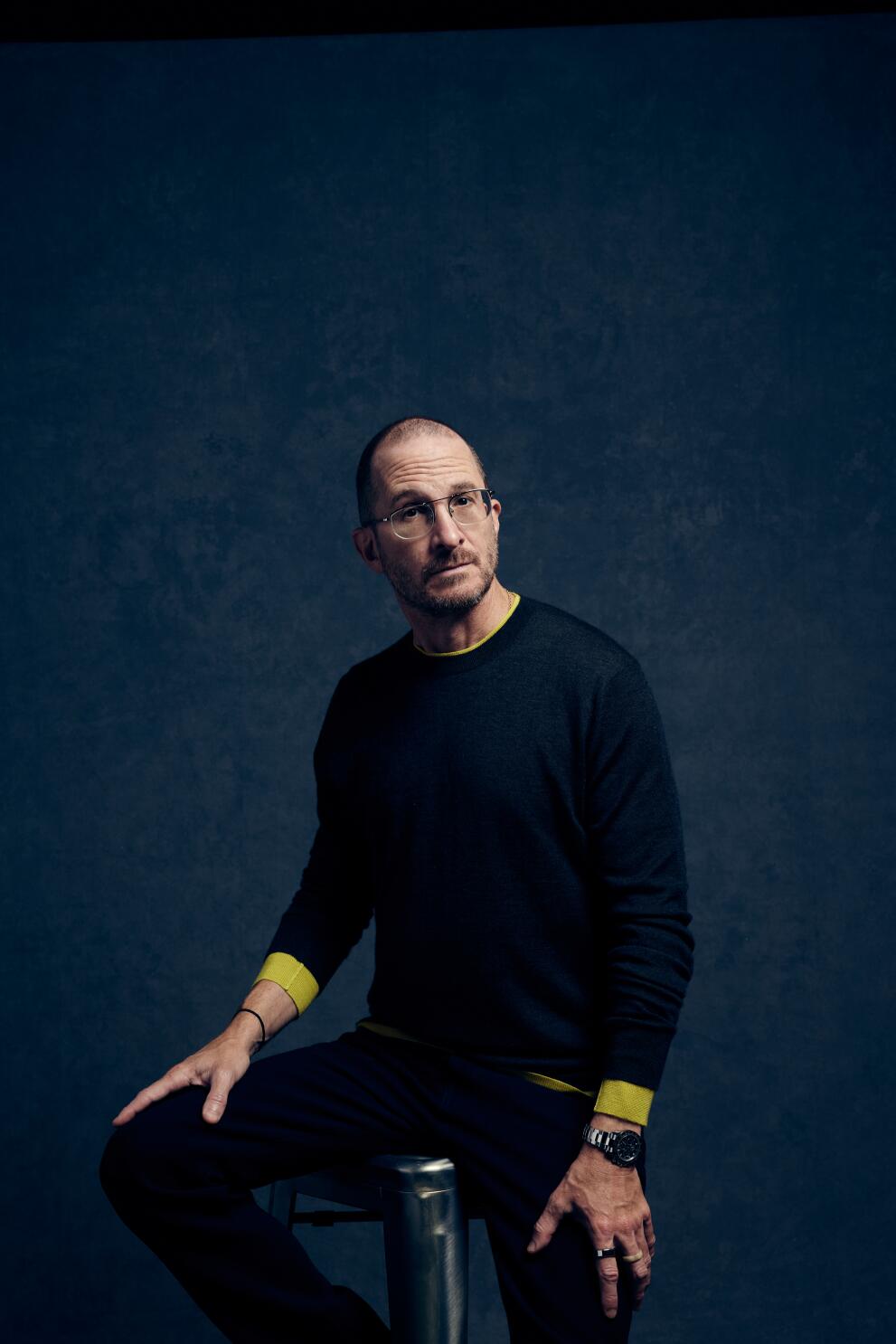

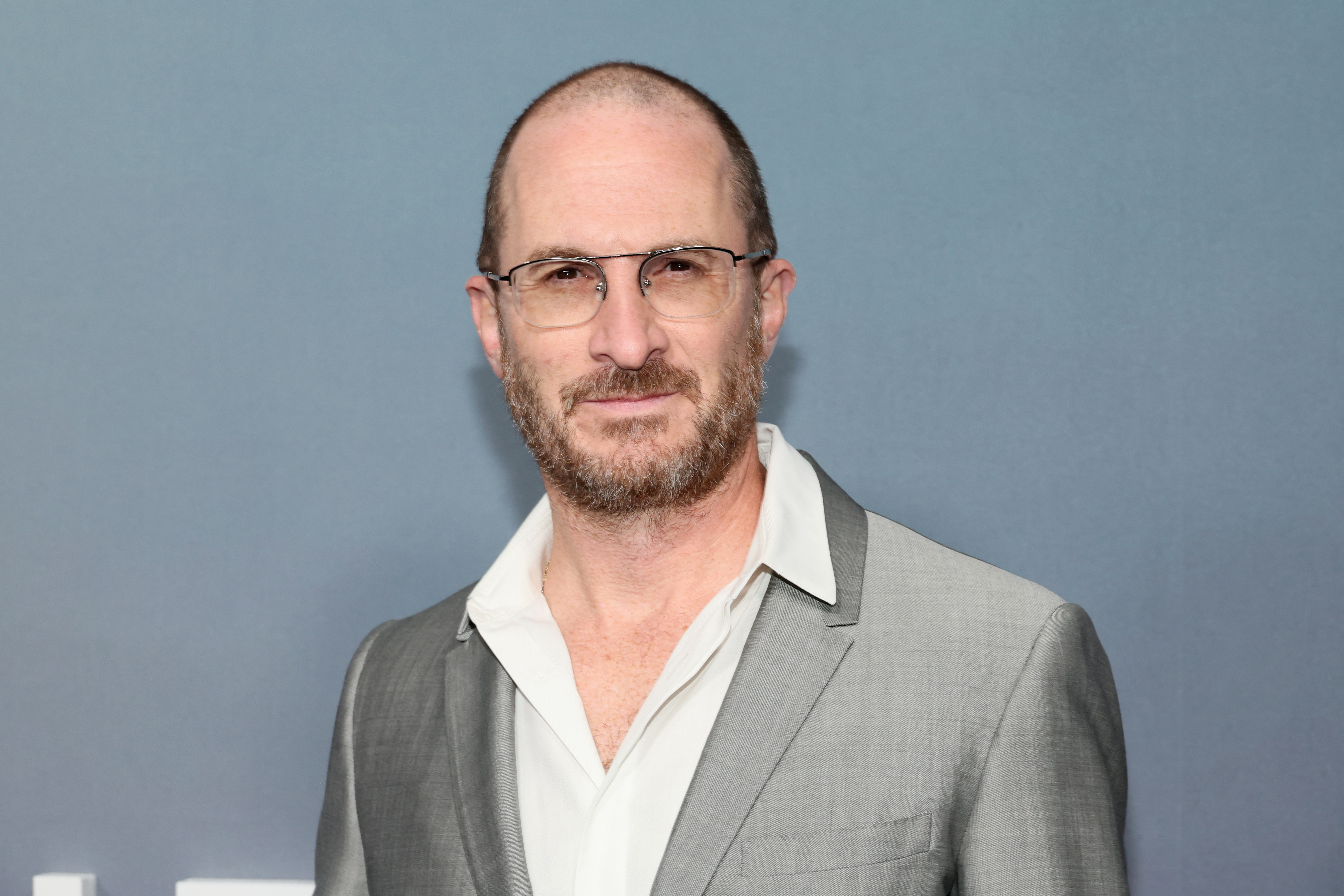

Last month, something unexpected landed on YouTube. Not another generic AI-generated content farm. Not a slick corporate promotional video. Instead, Darren Aronofsky's 'On This Day... 1776' emerged as a quiet revolution in how creative professionals think about artificial intelligence.

If you know Aronofsky's work, you know the guy doesn't do subtle. He made a career directing psychological thrillers that mess with your head. Black Swan. The Fountain. Requiem for a Dream. Each one deliberately unsettling, meticulously crafted, relentless in its vision. So when a director of his caliber picks up AI as a creative tool, it's worth paying attention.

But here's the thing: Aronofsky didn't let AI replace his vision. He weaponized it. He used it as a means to tell stories that would've been impossible to tell otherwise—200-minute documentaries about American history synthesized into 5-minute episodes, with production timelines measured in weeks instead of years. Not by sacrificing quality, but by amplifying his creative intent through intelligent automation.

This is the conversation that actually matters in 2025. Not "Will AI replace creators?" but "How do we give creators better tools to realize their vision?"

The project sits at an intersection that most industries have completely missed: the meeting point of artistic intentionality and technological capability. And it raises genuinely important questions about the future of content creation, historical storytelling, and what happens when you give sophisticated tools to people who actually know how to use them.

Let's break down what actually happened here, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of AI in creative industries.

The Project: 'On This Day... 1776' Explained

'On This Day... 1776' isn't a documentary in the traditional sense. It's closer to a visual essay series, where each episode re-imagines a specific moment from American Revolutionary history through the lens of modern filmmaking, AI-assisted visual synthesis, and historical research.

The premise is deceptively simple: take a date from 1776, research what actually happened, and then visualize it using a combination of traditional historical knowledge, dramatic reconstruction, and AI-generated imagery. Each episode runs roughly 5 minutes. There are dozens of them. Together, they form something closer to a visual history book than a linear documentary.

What makes this different from, say, a Ken Burns documentary or a typical History Channel special is the production approach. Aronofsky and his team used AI video generation tools to accelerate the visualization process. Rather than spending months in pre-production, scouting locations, building sets, or licensing historical footage, they could generate historically accurate visual references in hours.

But—and this is critical—the AI didn't drive the creative decisions. The human vision did. The team researched each date extensively, developed shot lists, wrote scripts, and then used AI as a production accelerator. It's the difference between "AI made this" and "AI helped me make this."

The visual quality varies—some episodes are stunning, others are clearly AI-generated and benefit from being honest about it. But that's actually part of the project's authenticity. Aronofsky didn't try to hide the seams. He didn't pretend the AI imagery was shot film. He let the medium be visible, which somehow makes the storytelling stronger.

Compare this to what usually happens when big production companies experiment with AI. They either hide the AI completely (which is dishonest) or they lean so hard into the AI novelty that the story disappears (which is cynical). Aronofsky found a third path: transparency about the medium combined with absolute clarity about the story.

The scope of the project is also worth mentioning. There are episodes covering January, February, March—basically one for every significant date in 1776. Some focus on military battles (Lexington, Concord, Bunker Hill). Others focus on political moments (the Declaration signing, congressional debates). Some feature major historical figures. Others focus on ordinary people. The breadth is impressive, and creating that much content at traditional production timelines would've been prohibitively expensive.

Yet the budget remained reasonable because the workflow was optimized. Research, script, visual planning, AI generation, refinement, editing. The steps were deliberate and efficient.

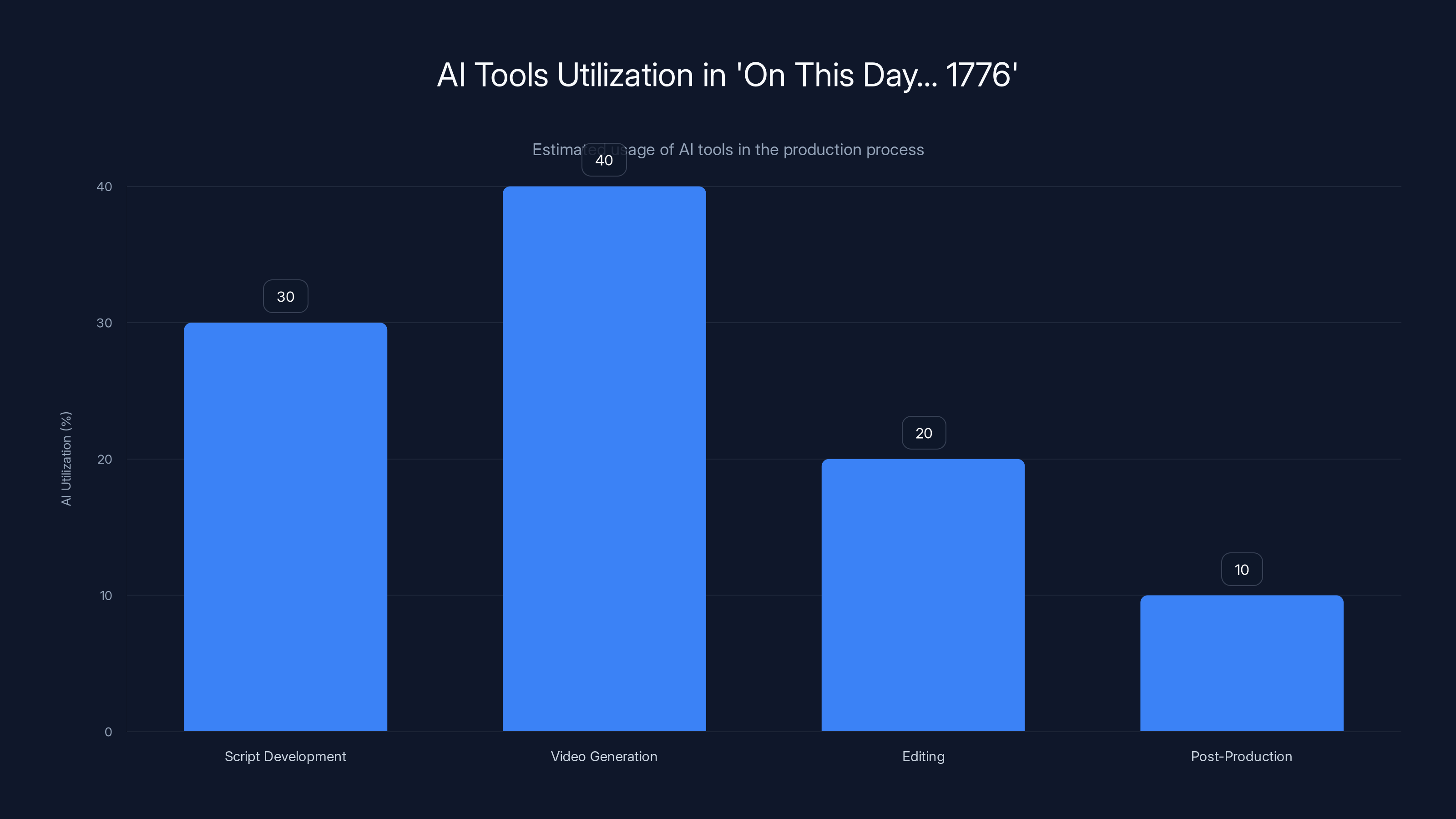

AI-assisted production can reduce costs dramatically, allowing for 25 episodes at the cost of one traditional episode. Estimated data.

Why This Matters: The Creative Control Question

Here's what most AI discourse gets wrong: it assumes the technology's capabilities determine what gets made. If AI can generate photo-realistic videos, then someone will flood the internet with photo-realistic AI videos. If AI can write scripts, then scripts will become AI-written.

But that's not actually how creative mediums work. Photography didn't replace painting just because it could capture reality more literally. It freed painters to do things beyond literal representation. Film didn't destroy theater. Digital audio didn't kill live music. Each new tool found its niche, and the tools that stuck around were the ones that expanded creative possibility rather than just accelerating production of existing things.

Aronofsky's project suggests that the same will be true for AI in visual storytelling. The technology isn't here to replace directors, cinematographers, or editors. It's here to expand what they can do within real constraints: time, budget, and scope.

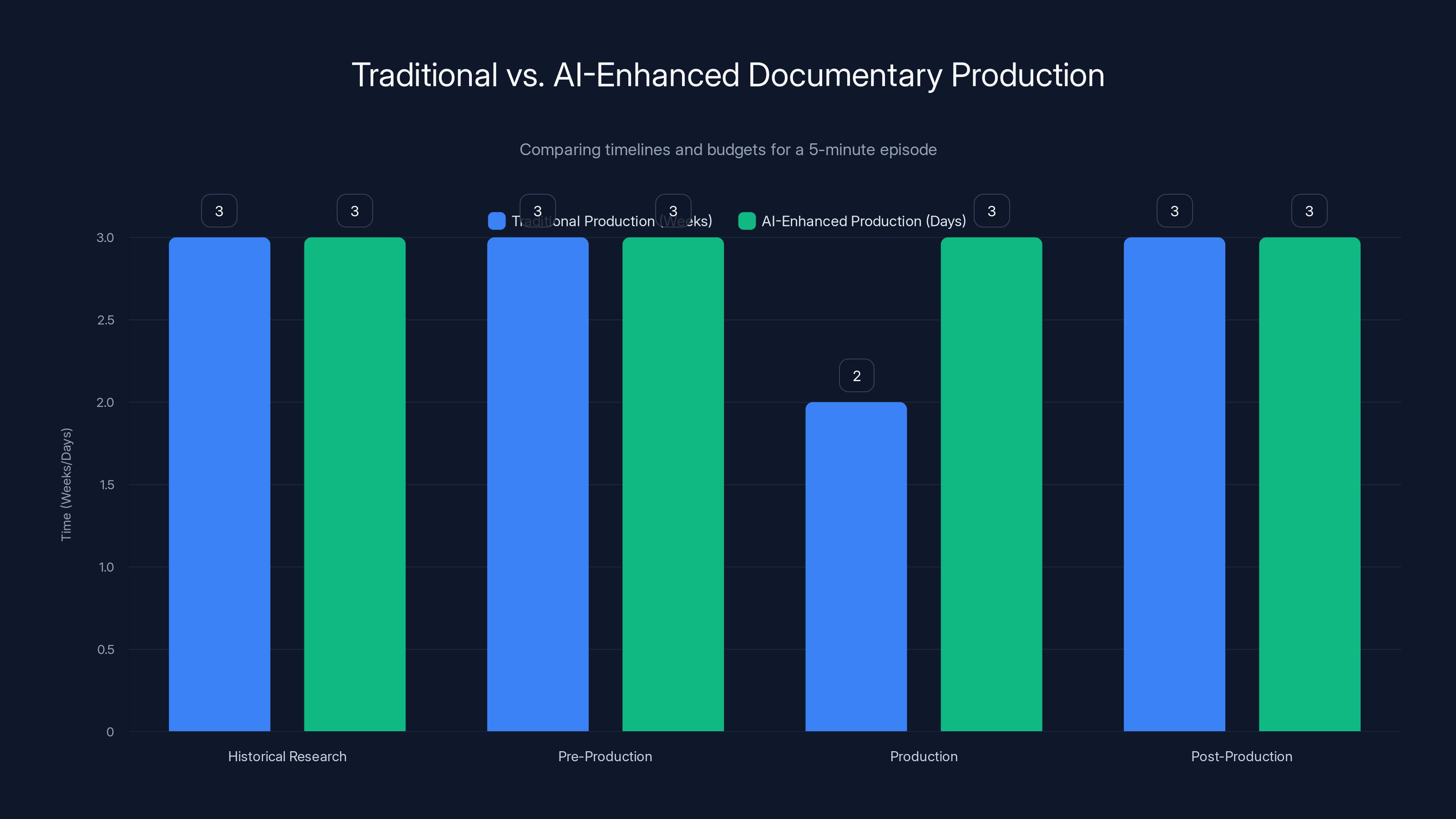

Consider the traditional documentary production pipeline. A director has a vision for a 5-minute episode about a specific historical moment. To execute that vision traditionally, they'd need:

- Historical research and consultation (weeks)

- Location scouting or set design (weeks)

- Casting or hiring actors (weeks)

- Filming with crews (days to weeks)

- Post-production, color grading, sound design (weeks)

- Revisions based on first cuts (weeks)

Total timeline: 3-4 months for a single 5-minute episode. Budget:

Now consider what Aronofsky's team likely did:

- Historical research and consultation (days)

- Script and visual planning (days)

- AI video generation with prompts and iterations (days)

- Integration with historical footage and archival material (days)

- Post-production and refinement (days)

Total timeline: 1-2 weeks. Budget: probably

That efficiency doesn't mean quality compromises. It means the creator can spend more time on the story, less time on logistics. It means revisions become possible—if the director doesn't like how an AI-generated scene turned out, they can regenerate it in hours instead of reshooting with actors and crews.

This is genuinely significant for historical storytelling specifically. History documentaries are expensive, so they're rare, so they become gatekept by networks and studios. If an independent filmmaker or academic institution can produce high-quality historical documentaries on a fraction of the traditional budget, that changes accessibility to historical narrative entirely.

But that only works if the technology serves the vision. Which is where the artist-led approach becomes non-negotiable.

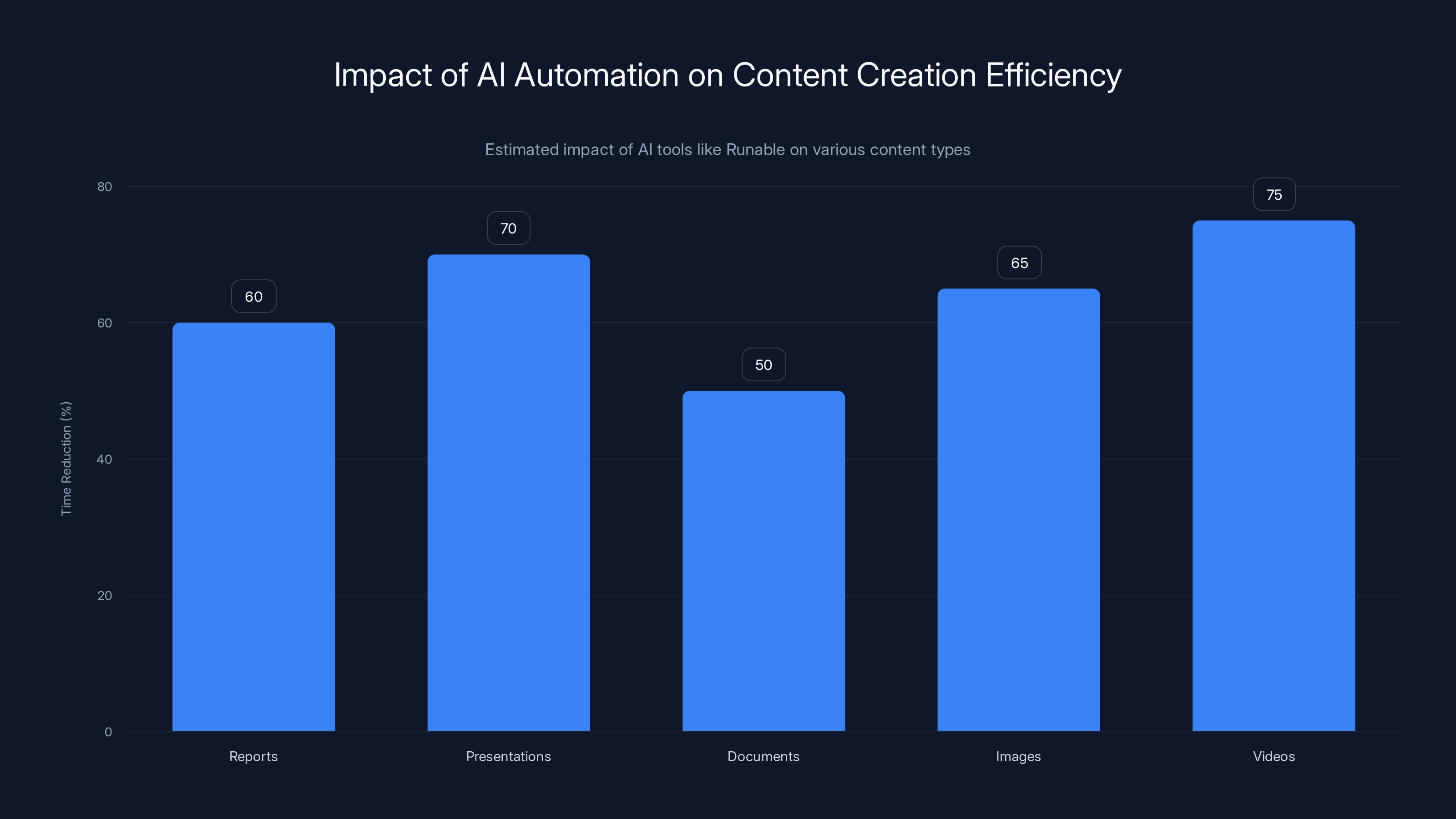

AI-powered platforms like Runable can significantly reduce production time across various content types, with estimated time reductions ranging from 50% to 75%.

The AI Tools Involved: What Actually Made This Possible

Aronofsky didn't build custom tools. He didn't collaborate with Deep Mind to create specialized historical AI. He used commercially available technology—the same tools that are available to anyone with an internet connection.

The most likely candidates for his workflow:

Open AI's GPT-4 or later models for research synthesis and scriptwriting. LLMs are genuinely good at taking raw historical information and structuring it into narrative form. A director could prompt the system with "Write a 500-word script about the signing of the Declaration of Independence as a dramatic scene" and get a solid first draft in minutes.

Runway ML or Open AI's Sora for video generation. These tools can generate video clips from text descriptions, which is perfect for historical visualization. You write a scene—"A Continental Army soldier marching through snow, dawn light, winter 1776"—and the AI generates a video clip matching that description.

Descript or similar tools for editing and transcription, which accelerate the post-production workflow.

Midjourney or Eleven Labs for static image generation and voiceover synthesis if needed.

None of these are specialized for historical documentary. They're general-purpose AI tools. The specialization comes from how Aronofsky's team prompted them, what they asked for, and how they curated the output.

This is actually important because it shows the technology is democratized. You don't need proprietary tools or billion-dollar budgets to use AI creatively. You need taste, vision, and the discipline to use tools as servants rather than masters.

What probably happened in practice: a writer or researcher compiled detailed notes about a historical event. That got fed into an LLM with a specific prompt structure. The output came back as a script. That script got refined by human editors who understand narrative. The script then became prompts for video generation tools. Those prompts got adjusted iteratively until the generated footage matched the creative vision. Then everything went into a traditional editing suite for final assembly.

It's a hybrid workflow, which is exactly what sustainable AI integration looks like. Not complete automation. Not humans with minor robotic assistance. A thoughtful collaboration between human judgment and computational speed.

The Historical Accuracy Question: Can AI Get History Right?

This is where skeptics usually get uncomfortable. AI models are trained on the entire internet, which includes vast amounts of historically inaccurate information. Conspiracy theories, revisionist histories, outdated scholarship. If you feed an AI vague historical prompts, you'll get vague, potentially inaccurate results.

So how does Aronofsky ensure accuracy?

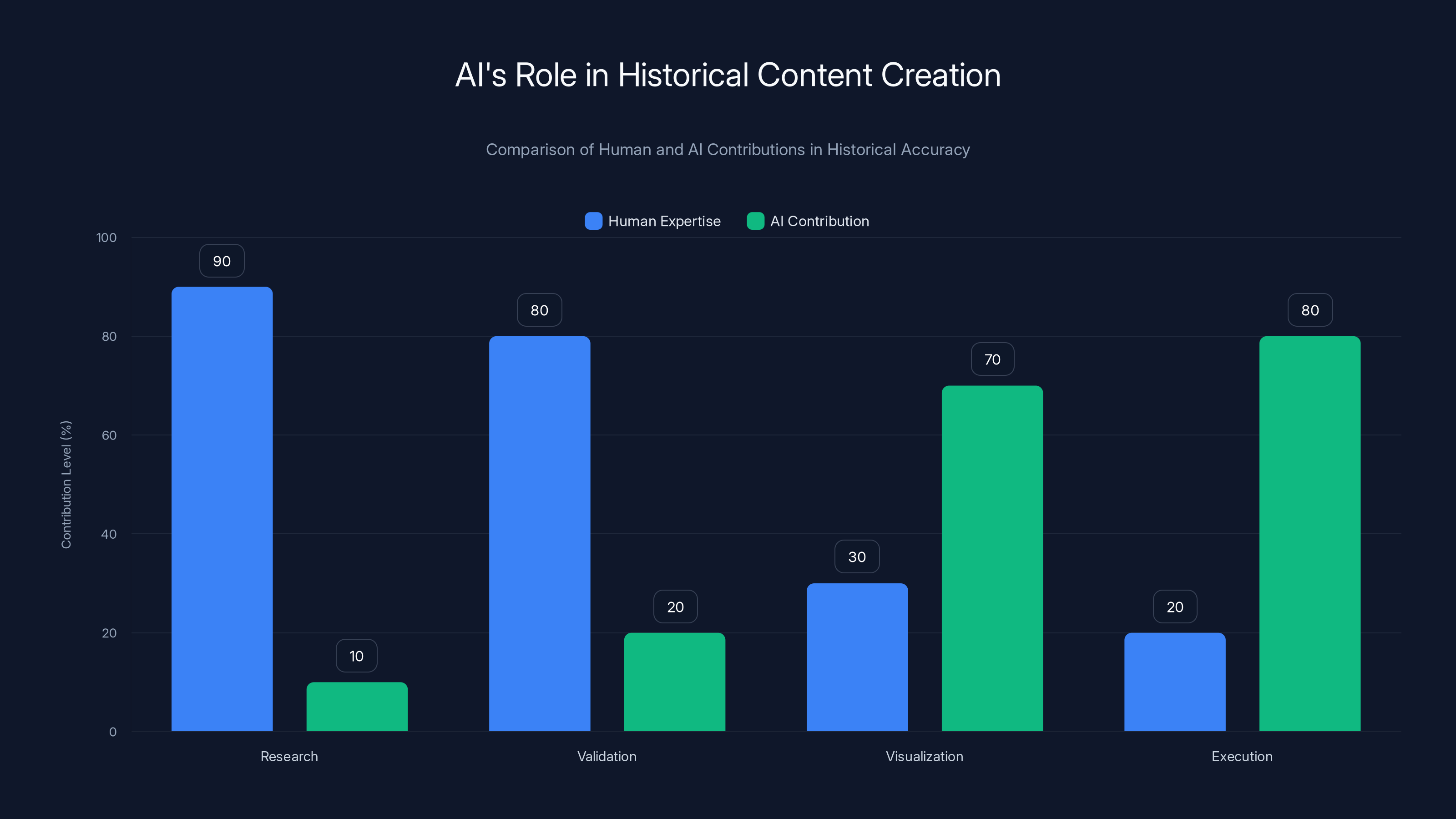

The answer is almost mundane: human expertise baked into the process. You have historians or researchers who validate the script before it goes to production. You have fact-checkers who verify specific claims. You have subject matter experts who review the visuals for historical plausibility.

AI isn't being trusted to "know" history. It's being used to accelerate visualization of history that humans have already validated. The AI is handling the rendering problem, not the research problem.

This is the right way to deploy AI in any domain where accuracy matters: use human expertise to establish ground truth, then use AI to scale execution of that truth.

Consider how this might work for a specific episode about the Battle of Bunker Hill. A historian researches what actually happened: the timeline, the tactics, the key figures, the terrain. They write a scene breakdown:

- Scene 1: British forces advancing up Breed's Hill, early morning light

- Scene 2: Colonial forces holding fire until "you see the whites of their eyes"

- Scene 3: British forces retreat with heavy casualties

- Scene 4: Colonial forces regroup, acknowledging the victory despite tactical retreat

Then those scene descriptions become prompts for the AI video generation tool. "British redcoats in 18th-century uniforms climbing a grassy hillside, smoke from cannons in the background, historical accuracy." The AI generates a video clip that matches that description. The human reviews it: Does it look historically plausible? Does it match the visual tone of the project? Is anything obviously anachronistic?

If yes to all three, the clip gets used. If no, the prompt gets revised and regenerated.

Is this perfect? No. AI sometimes hallucinates details—you might get a soldier with 12 fingers or a cannon that looks suspiciously modern. But those errors are catchable by a human with domain knowledge. And they're increasingly rare as the technology improves.

The deeper point: accuracy isn't a property of the AI. It's a property of the process. Rigorous AI can be inaccurate if the prompts are sloppy. Sloppy AI can be accurate if the process includes human validation. Aronofsky's team seems to understand this distinction.

AI-enhanced production significantly reduces the timeline from 3-4 months to 1-2 weeks, demonstrating its potential to streamline the creative process. Estimated data.

The Economics: Why Budget Matters for Art

Let's talk about money because it's not romantic but it's decisive.

Historical documentaries barely exist anymore. A quick search of traditional broadcasters shows the genre is in decline. Why? Because they're expensive to produce and the audiences are niche. You need significant institutional backing—a broadcast network, a streaming service, a well-endowed university—to justify the budget.

This means the stories that get told about history are determined by what institutions think will appeal to mass audiences. Which biases the historical narrative toward drama, celebrity, and spectacle. The stories that don't fit those boxes—the overlooked figures, the complex political moments, the ordinary people—don't get told.

AI doesn't fix this entirely, but it changes the equation. If you can produce a high-quality 5-minute historical episode for

This doesn't mean the work gets easier. It means the barrier to entry drops. Which is how mediums actually change: the barrier to entry drops, more people experiment, some of them are brilliant, the medium evolves.

Consider what this means at scale. Imagine a high school history teacher using AI tools to create supplementary content for their curriculum. Imagine a college professor making visual explanations of complex historical arguments. Imagine international creators telling the history of their own regions without waiting for Western institutions to fund it.

That's the economic argument for AI in creative fields: not that it makes things cheaper by cutting quality, but that it makes quality cheaper, expanding access.

Aronofsky's project proves this economics work. The production timeline is realistic. The quality is defensible. The scope is ambitious. All of this becomes possible because AI reduced the production friction.

The Storytelling Innovation: What New Is Possible

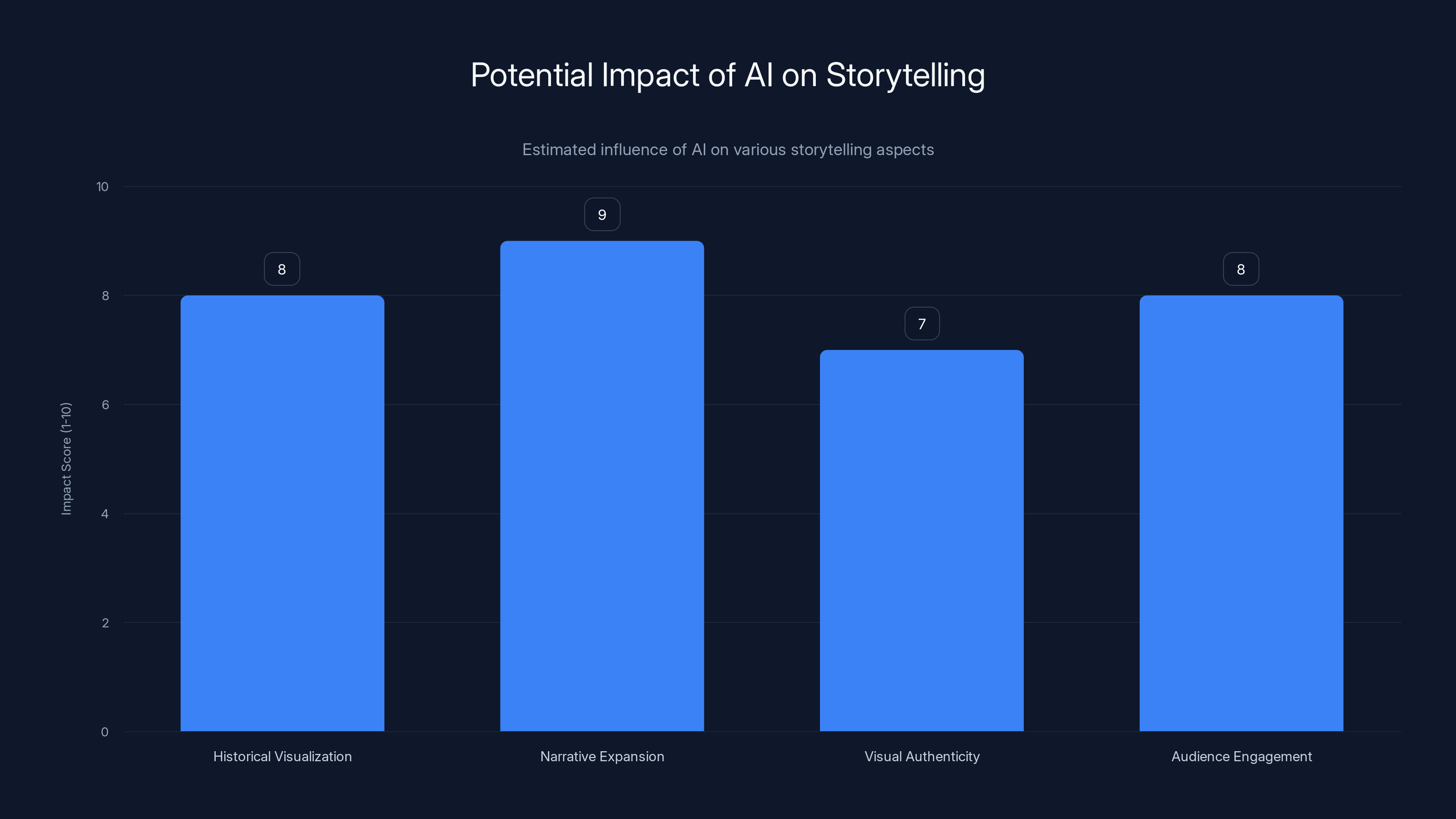

Beyond efficiency, AI enables narrative structures that were previously impossible.

A traditional documentary is constrained by what you can actually film or access. You can't recreate a 18th-century battlefield in its original state. You can't interview George Washington. You can't have a camera at the signing of the Declaration. You're stuck with voiceover, archival stills, maybe some reenactments with actors.

AI doesn't solve this completely, but it expands the palette. You can generate footage that visualizes historical moments with dramatic authenticity. Not documentary authenticity (which would require actual time travel), but visual plausibility that draws the viewer into the moment more effectively than a still image or voiceover ever could.

This changes what kinds of stories you can tell. You're not limited to the moments that happened to be photographed or documented. You can tell the stories where the visual record is sparse or nonexistent, because you can generate visualizations that serve the narrative.

Aronofsky's episodes about battles are interesting because we have some visual references—period paintings, descriptions, landscape records. But his episodes about the everyday moments of 1776—the debate in Congress, the experience of ordinary soldiers, the life of people in towns under occupation—those are harder to find archival material for. AI lets you visualize those stories without pretending to have documentary evidence that doesn't exist.

This raises interesting questions about visual literacy. If the audience knows the footage is AI-generated, does it have less truth value than archival footage? Or does the honesty about the medium actually increase the truth value by refusing to pretend certainty where none exists?

Aronofsky seems to be answering: it depends on the frame. If you're presenting AI footage as if it's documentary evidence, that's dishonest. But if you're transparent that this is a visualization of what these moments might have looked like, based on historical research, then you're using the medium more honestly than most historical television, which routinely embellishes and dramatizes archival footage without ever acknowledging it's doing so.

The narrative innovation also extends to pacing and structure. Each episode is roughly 5 minutes, which is a constraint that most broadcast documentaries don't have. TV documentaries are usually 45 minutes to 90 minutes, which encourages a certain kind of narrative sprawl. You have time to develop characters, build dramatic tension across a full arc, resolve themes.

Five minutes is tight. You're telling a story that has to land in the time it takes to make coffee. This enforces narrative discipline. You can't waste a frame. Every scene has to do specific work: establish context, develop conflict, resolve tension, or land a historical insight.

Aronofsky's background is instructive here. He's made films ranging from 5 minutes to 3 hours. He understands how to tell stories at different scales. Five-minute historical episodes aren't a format he's being forced into. They're a format he's chosen for specific narrative reasons. They're like short stories compared to novels—different shapes, different rhythms, different possibilities.

Estimated data shows AI is most utilized in video generation (40%) and script development (30%), with human oversight in editing and post-production.

The Creative Control Problem: Where AI Fails Without Vision

Let's get real about the limitation: AI is a tool that amplifies intentions, whether those intentions are good or terrible.

If you use AI with no clear creative vision, you get generic output that sounds like it was generated by an algorithm, because it was. If you use AI with a specific, developed creative vision, you get output that serves that vision.

Aronofsky succeeds because he has a vision. He's a director who's spent decades developing a visual language, a way of thinking about storytelling, a sensibility about what matters in an image. He's not learning how to be a creator by using AI. He's using AI as a production accelerator for work he's already deeply thought through.

This is why the "AI will replace creators" anxiety is misplaced. AI can replace technical execution of a vision. It cannot generate vision. You still need humans for that. You need people who care about what the story means, how it lands emotionally, what truth it's trying to tell.

The corollary is darker: AI will definitely amplify mediocre vision and make it scalable. If you have a terrible idea and unlimited AI tools, you can now make that terrible idea at scale and distribute it globally. That's not the tool's fault. It's a warning about how we use tools.

What matters is the same thing that's always mattered in art: taste, intention, discipline, and the willingness to revise until something is right.

Aronofsky's project suggests that when artists with real vision encounter powerful tools, they don't stop being artists. They become more ambitious. They try things they couldn't before. They expand their practice rather than outsourcing it.

This is worth emphasizing because it directly contradicts how tech companies market AI to creators. They show capability first: "Look what AI can generate!" The implication is that if you have the tool, the content creation will follow. In reality, it works backward. You need the content creation intention first, then find tools that serve it.

What This Reveals About AI in 2025

Aronofsky's project is instructive not because it's particularly novel—lots of creators are experimenting with AI—but because it demonstrates what thoughtful AI adoption actually looks like.

It's not hidden. You can see that AI was used. Some of the footage looks noticeably synthetic. And rather than being ashamed of that, the project seems to embrace it as honest about the medium. You're watching a historical visualization, not pretending it's documentary reality.

It's not replacing humans. The human creative vision is unmistakably present. The choices about what to show, how to frame it, what emotional tone to strike—those are clearly made by someone who knows storytelling.

It's not cutting corners. The research is rigorous. The script is developed. The visuals are curated. Using AI didn't make the work easier so much as it made the work different—less time on production logistics, more time on creative decisions.

It's not proprietary. It's using tools that are commercially available and technically accessible to any creator with internet access. This matters because it means the project is replicable. You don't need a special relationship with a tech company. You don't need custom tools. You just need to know how to ask the tools the right questions.

It's not a replacement for traditional skills. You still need to understand narrative structure, visual composition, pacing, how to land emotional beats. AI doesn't teach you those things. It just gives you faster feedback loops as you practice them.

All of this suggests that the AI conversation in creative industries should probably shift. Less "Will AI replace us?" More "What kind of creators will thrive as these tools become ubiquitous?" The answer seems to be: the ones who have a clear vision, understand their medium deeply, and are willing to learn new tools as servants rather than masters.

This also suggests that the institutional barriers to creative work will probably lower over the next few years. Not disappear, but lower. Fewer gatekeepers will be necessary to greenlight expensive productions. More creators will be able to make professional-quality work independently. This has obvious upside for diversity and access. It also has obvious downside in terms of quality control and commercial viability.

The medium will sort itself. Some creators will use AI thoughtlessly and produce noise. Some will use it with intention and create work worth seeing. That's been true for every technology since the printing press.

Human expertise is crucial in research and validation stages, while AI excels in visualization and execution, highlighting a collaborative approach for historical accuracy.

The Broader Implications: What Happens Now

Where does this moment in creative AI actually lead?

In the short term, we'll probably see a lot of experimental work like Aronofsky's. Established creators exploring what's possible. Some experiments will be brilliant. Some will be disasters. Most will be interesting failures that teach us something.

In the medium term, institutions will figure out how to hire for this. Universities will offer courses in AI-assisted filmmaking. Production companies will develop specialized roles for people who understand both creative vision and AI prompting. We'll see the emergence of new job categories that don't exist yet—AI creative director, AI art collaborator, prompt strategist for visual content.

In the longer term, the question is whether AI becomes a democratizing tool or a concentrating one. Right now, it's moving toward democratization—cheaper tools, more accessible, harder to gatekeep. But we've seen this story before with digital filmmaking. Initially democratized (anyone could shoot HD on a camera), then consolidated (only people who could afford professional workflows competed at high levels). It might follow that pattern.

What seems likely: AI won't replace the need for creative vision. It will raise the floor for technical execution so that more people can realize ambitious visions. It will make bad ideas cheaper to produce and distribute, which is a problem we'll have to solve culturally, not technologically. And it will enable new kinds of storytelling that weren't previously possible, which is where the real innovation happens.

For Aronofsky specifically, this project seems like a proof of concept. If it works, if audiences engage with it, if it generates conversation, we might see him tackle larger projects with the workflow he's developed here. A full series of AI-assisted documentaries about American history. Maybe something international. Maybe something contemporary. The possibility space suddenly expands when the production bottleneck shrinks.

For the broader media landscape, the implications are more significant. If historical documentaries become cheaper to produce, we might actually see more of them. If educational content can be produced more affordably, schools and universities might create better visual learning materials. If any creator can access AI video generation, we might see storytelling emerging from communities and perspectives that traditionally couldn't access broadcast media.

That's the optimistic read. The pessimistic read is that we get flooded with garbage, copyright becomes even more complicated, and the concentration of power in tech companies who control the AI systems increases. Both are probably partially true.

What matters is intention. Aronofsky's project matters because it shows that AI in the hands of someone with real creative vision produces something worth engaging with. It's not a guarantee that all AI-assisted creative work will be valuable. It's evidence that it's possible.

Why This Moment Matters: The Inflection Point

We're at an interesting inflection point in how culture thinks about AI.

A year ago, most of the conversation was still about AI replacing jobs or hallucinating dangerous misinformation or being trained on stolen data. All of those concerns are legitimate and still active. But there's a parallel conversation that's less focused on apocalypse and more focused on actual creative practice.

Aronofsky's project is part of that quieter conversation. It's not screaming about AI disruption. It's not trying to prove AI is dangerous. It's just using available tools to tell stories that wouldn't otherwise get told. It's pragmatic and intentional.

This matters because it demonstrates a path forward that isn't either "AI will replace everything" or "Let's ban AI and return to normal." It's "Let's figure out how to use these tools in ways that serve human creativity rather than replacing it."

That path requires several things:

First, transparency about what's AI-assisted and what's not. If you're using AI, say so. Not to shame it, but to give the audience context for interpreting what they're seeing.

Second, rigorous curation by humans with taste and expertise. AI is a tool for generating options. Humans choose which options matter. That curation is where the actual creative work happens.

Third, recognition that the tool serves the vision, not the other way around. You can't start with "What can AI do?" You have to start with "What do I want to make?"

Fourth, ongoing attention to bias, accuracy, and the ethics of deploying tools at scale. AI isn't neutral. It encodes assumptions and values. Using it responsibly means thinking about those implications.

Fifth, a willingness to learn new skills without expecting them to replace foundational creative knowledge. AI is a new skill layer on top of narrative, visual composition, and understanding your audience.

Aronofsky's project seems to understand all of these principles intuitively. Which is why it reads as thoughtful rather than cynical, ambitious rather than lazy, innovative rather than gimmicky.

AI significantly enhances storytelling by enabling historical visualization and expanding narrative possibilities (Estimated data).

The Future of AI-Assisted Storytelling

What happens next depends partly on technology, but mostly on culture.

Technology-wise, the tools are improving rapidly. Video generation models are getting better at following prompts precisely. LLMs are getting better at maintaining consistency across long-form content. Image generation is getting better at specific details and avoiding hallucinations. The baseline capability will keep rising.

But capability isn't destiny. Better tools don't guarantee better outcomes. They just make certain outcomes easier. What we actually make with better tools depends on what we value and what constraints we work within.

Cultural factors will probably matter more than technical ones. Do platforms reward AI-assisted content or penalize it? Do creators feel comfortable acknowledging AI involvement or do they hide it? Do audiences care if something is AI-assisted if it's good? Do institutions figure out how to fairly compensate the creators and training data that AI depends on?

These are governance questions, not technology questions. And they'll determine whether AI in creative fields becomes a tool for expanding who gets to create or a tool for concentrating creation in the hands of whoever controls the largest AI systems.

For historical documentary specifically, the stakes are actually kind of high. History shapes how cultures understand themselves. If AI makes historical storytelling cheaper and more accessible, that could distribute that power. If it concentrates in the hands of whoever controls the most sophisticated models, that could concentrate it further.

Aronofsky's project suggests a middle path: using commercially available tools that are accessible to anyone, with clear human curation, for transparent storytelling about important historical moments. It's not revolutionary. But it's a proof that the middle path is possible.

Lessons for Any Creator: How to Think About AI

If you're a creator thinking about incorporating AI into your practice, what does Aronofsky's work suggest?

Start with vision, not tools. Know what story you want to tell, what you're trying to make, what would make this worth doing. Then ask: where does AI accelerate that? Not: what can AI do that I can't? That's backward thinking.

Understand the tools but don't fetishize them. AI video generation is not magic. It's pattern matching at scale. It's remarkably good at certain things and terrible at others. Spend time actually using the tools before committing to them in your work. Understand their constraints as well as their capabilities.

Maintain human curation. AI generates options. You choose which options serve your vision. That filtering process is where the actual creative work lives. If you're just accepting the first output from an AI tool, you're not being creative. You're being lazy.

Be honest about what you're using. If you're using AI, say so. Not to apologize for it, but to give your audience context. Transparency actually increases trust more than hiding your process ever does.

Keep developing foundational skills. Understanding narrative structure, visual composition, how to land emotional beats—these don't become less important because AI exists. They become more important because they're what distinguish intentional work from algorithmic output.

Experiment and iterate. The best way to understand what AI can do in your practice is to actually try it. Make things. See what works. Fail. Adjust. This is how any new tool gets integrated into creative practice.

Think about access and democratization. If a tool you're using makes it possible for more people to create, that's generally good. If it concentrates creation in fewer hands, that's worth questioning.

Aronofsky's project is instructive because he seems to intuitively understand all of these principles. He's not a "digital native" who grew up with AI. He's a traditional filmmaker who's using AI as a production accelerator for stories he deeply cares about. That's probably the model that actually scales: established creators bringing their vision and rigor to new tools.

The Real Test: Audience Engagement

Ultimately, what matters is whether people actually watch and engage with Aronofsky's series.

Does the project reach beyond the people interested in AI and historical documentary to broader audiences? Do people actually learn about 1776 from watching these episodes? Do they feel emotionally connected to the stories? Do they recommend it to friends?

Those are the metrics that determine whether this is actually an innovation in storytelling or just a technically interesting experiment.

Artistically, the project has already accomplished something: it's proven that AI-assisted historical visualization can be done thoughtfully, with rigor, and with clear human creative vision. That's valuable in itself. It expands the conversation beyond "Is AI a threat?" to "What's possible when we use AI intentionally?"

But if the work doesn't engage audiences, if it ends up being a curiosity that appeals only to people interested in AI, then it's a missed opportunity. The real test is whether the stories land emotionally and intellectually with people who just want to understand history better.

Based on what's publicly available, the initial reception seems positive. The episodes are getting watched. People are discussing them. The visual quality is good enough that most viewers probably don't spend the whole time thinking about whether the footage is AI-generated—they're just watching the story.

That's actually the ideal outcome. You want the technology to be invisible in the sense that it's not distracting, even if people intellectually know it's there. The tool should serve the story, not become the story.

Connecting to the Bigger Picture: How Runable Fits This Landscape

What does all this have to do with modern content creation and automation? More than you might think.

Aronofsky's project solves a specific problem: how to create high-quality visual content at scale without waiting months for traditional production timelines. He accomplished it using a combination of commercial AI tools and thoughtful human curation.

But the same principle applies to other kinds of content. If you're creating presentations, documents, reports, or marketing materials—the day-to-day content that most organizations produce constantly—you face the same bottleneck: production time, resources, and the ability to iterate.

This is where platforms like Runable fit into the picture. Rather than building custom workflows for each type of content, Runable offers AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, reports, images, and videos. The principle is the same as Aronofsky's approach: accelerate production without sacrificing quality or creative control.

Say you need to create a weekly report on project status. Traditionally, that's manual work: pull data, write analysis, format, design, distribute. With AI automation, you can structure the core content with your insights, let the system handle formatting and design, and spend your time on the actual analysis rather than the logistics.

Or you're building a pitch presentation. You outline the key points, the AI generates structured slides, you refine the narrative and visuals, and you're done in hours instead of days.

The same principle Aronofsky demonstrated—use AI to accelerate production of your vision, maintain human curation, be transparent about what you're doing, keep developing your core skills—applies across content creation.

Use Case: Generating professional reports from raw data in minutes instead of hours, while maintaining your analysis and insights as the core value.

Try Runable For FreeThis is the non-romantic version of creative AI adoption: not making experimental documentaries, but making the mundane work faster so you can focus on thinking clearly. Aronofsky's approach scales. Across organizations and creators, the pattern is the same: identify the bottleneck, apply the right tool, maintain human quality control, iterate.

The tools vary—Aronofsky uses video generation, content creators use presentation automation, researchers use document synthesis—but the principle is consistent. That principle is probably what matters most going forward.

What We Actually Learned from This Project

Let's summarize what Aronofsky's 'On This Day... 1776' actually demonstrates about AI and creative work in 2025:

First, AI is most useful as a production accelerator, not a creativity replacement. The creative vision determines what gets made. The AI determines how fast it gets made.

Second, transparency about AI use doesn't reduce work value. If anything, it increases credibility by refusing to pretend false certainty. The audience respects honesty about the medium.

Third, human expertise remains essential. Someone has to curate, edit, validate, refine. That's where the actual creative work happens. AI handles execution. Humans handle everything else.

Fourth, the tools are already democratized. You don't need special access or billion-dollar resources. Commercial tools exist. Anyone can use them. Which means the barrier to entry drops, and who gets to create expands.

Fifth, cost efficiency enables ambition. When production becomes cheaper, creators can attempt more ambitious projects. Aronofsky can now make 52 episodes where he could previously make 4. That changes what's possible.

Sixth, the medium isn't determined by the technology. Photography didn't kill painting. Video didn't kill theater. AI won't kill human creativity. It will change what kinds of creativity are viable and who gets to practice them.

Seventh, the future depends on culture and governance more than on technology. Better tools alone don't guarantee better outcomes. What matters is how we choose to use them, who controls them, and how we ensure they expand access rather than concentrate power.

All of these lessons extend beyond historical documentary to any creative work. Which is probably why this project matters enough to discuss at length.

The Bottom Line: What Comes Next

Aronofsky's project isn't the future of AI in creative work. It's evidence that a particular kind of future is possible: one where thoughtful creators use powerful tools to realize ambitious visions, where technology serves human intention, where transparency about what's machine-generated and what's human doesn't reduce the value of the work.

That future isn't guaranteed. We could go in worse directions: massive AI-generated content farms flooding platforms with noise, concentration of creative tools in the hands of massive tech companies, loss of creative opportunities for professionals whose skills are automated away, increasing inability to trust what you see because anything could be AI-generated.

Or we could go in better directions: more creators having access to tools that previously required teams and budgets, smaller institutions and independent artists creating work that competes with major studios, historical narratives and cultural stories emerging from diverse voices that traditional media never centered.

Aronofsky's project suggests the better direction is possible. It's a proof of concept that you can use AI thoughtfully, with vision, and produce work that matters.

The question for creators is: what will you do with better tools? Will you maintain the vision and discipline to use them well, or will you let the tools use you? That distinction is where creativity actually lives.

FAQ

What is 'On This Day... 1776'?

'On This Day... 1776' is a YouTube series created by filmmaker Darren Aronofsky that uses AI-assisted video generation to visualize historical moments from the American Revolutionary period. Each episode is roughly 5 minutes long and focuses on a specific date or event from 1776, combining historical research with AI-generated imagery to create visual narratives that would be difficult or impossible to produce using traditional documentary methods.

How does Aronofsky use AI in the production process?

The project uses commercially available AI tools including language models for script development, video generation platforms for creating visual sequences, and other AI-assisted production tools. The workflow prioritizes human creative direction: researchers validate historical accuracy, writers develop scripts based on research, prompts are crafted for AI tools, generated footage is reviewed and refined by human editors, and everything goes through traditional post-production for final assembly. AI accelerates production, but humans maintain creative control at every stage.

What makes this project significant for creative AI adoption?

The project demonstrates several important principles: that AI works best as a production tool serving human creative vision rather than replacing it, that transparency about AI use builds rather than undermines credibility, that cost efficiency enables ambition in ways that expand creative possibilities, and that established creators with clear vision can integrate AI tools without compromising quality or artistic integrity. It's significant because it shows a sustainable model for AI in creative work.

Can AI-generated content be historically accurate?

Accuracy depends on the process, not the technology. If historians validate the research, writers develop accurate scripts, and human editors verify the generated visuals for historical plausibility, then AI-assisted content can be accurate. The AI isn't trusted to "know" history independently. It's used to visualize history that humans have already verified. This is the correct approach for deploying AI in any domain where accuracy matters.

Why does the project maintain transparency about AI use?

Transparency serves multiple purposes: it's ethically honest with the audience about what they're watching, it avoids the false claim of documentary authenticity when dealing with generated imagery, it allows viewers to understand the medium context they're interpreting, and it actually builds credibility by refusing to hide the tool. Most historical media obscures its construction and dramatization. Being transparent about AI use is more honest than most documentary practices, not less so.

What are the broader implications for historical storytelling?

If AI-assisted production reduces costs significantly, historical documentary production becomes more accessible to independent creators, academic institutions, and international voices that previously couldn't access broadcast budgets. This could distribute historical narrative authority beyond traditional Western media institutions. However, it also requires ongoing attention to accuracy, representation, and who controls the tools that enable this new access.

How does this project relate to other AI creative tools?

Aronofsky's approach—clear vision first, tools second, human curation throughout—is applicable to any AI-assisted creative work. Whether you're generating presentations, documents, reports, or video content, the principle is the same: identify what you need to create, understand the tools available, maintain quality control through human judgment, and use the tools to accelerate production so you can spend more time on creative decisions rather than technical logistics.

What skills remain essential for creators in an AI-assisted world?

Fundamental creative skills become more important, not less: understanding narrative structure, visual composition, emotional pacing, and how to land compelling ideas. AI can handle execution faster, but it can't generate vision. Domain expertise also matters—knowing history, understanding your audience, having taste and judgment about what works. The skill layer of learning to prompt AI tools effectively is new, but it's supplementary to these foundational skills, not a replacement for them.

Is AI in creative work an ethical concern?

Yes, several concerns exist: training data provenance and fair compensation for creators whose work trained the models, the potential for AI to concentrate creative power in hands of whoever controls the largest systems, the difficulty of verifying what's AI-generated and what's not as content floods platforms, questions about cultural representation in training data that shape what AI can generate. These are governance questions, not technology questions. They matter and require active attention.

What's the difference between AI replacing creators and AI amplifying them?

Replacement happens when the tool drives the creative decisions and humans execute. Amplification happens when humans drive the creative decisions and tools execute faster. Aronofsky's project is amplification: clear human vision, AI-accelerated production. The difference determines whether a creator becomes less relevant (replacement) or more productive (amplification). Creators who maintain vision and taste thrive. Creators who treat AI as a substitute for thinking don't.

Written by a senior technology journalist with deep expertise in AI, creative tools, and digital transformation.

Key Takeaways

- AI works best as a production accelerator serving human creative vision, not as a replacement for creators—demonstrated through Aronofsky's vision-first approach to historical storytelling

- Cost efficiency through AI-assisted production enables ambition: weekly production timelines instead of multi-month ones, enabling 52 episodes where traditional methods allow only 4

- Transparency about AI use builds credibility rather than undermining it when combined with rigorous human curation and historical validation

- The barrier to entry for professional-quality content creation drops when AI tools become commercial and accessible, potentially democratizing storytelling across communities and perspectives

- Fundamental creative skills—narrative structure, visual composition, taste, judgment—become more valuable, not less, as technical execution accelerates through AI

![Darren Aronofsky's AI History Series: Artist-Led Storytelling [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/darren-aronofsky-s-ai-history-series-artist-led-storytelling/image-1-1769766013848.png)