When Your Eyelids Won't Cooperate: The Strange Case of Floppy Eyelid Syndrome

Imagine waking up one morning and realizing your eyelids won't stay in their normal position. They're drooping, rolling inward, flipping inside-out on their own. You can't fully close your eyes. The irritation is constant. You rush to an ophthalmologist expecting to hear about a structural problem, maybe something requiring surgery. Instead, they tell you the real culprit isn't your eyes at all—it's what's happening while you sleep.

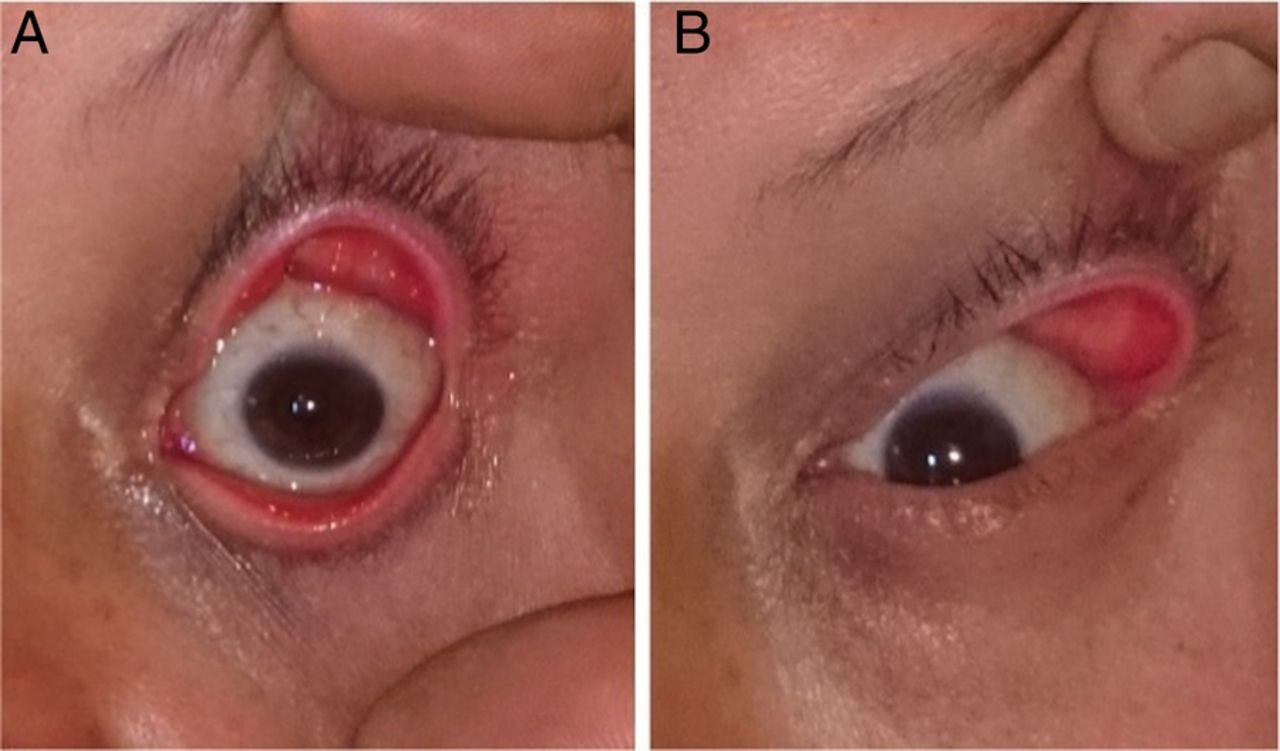

This isn't science fiction. It happened to a 39-year-old woman in Brooklyn who walked into an ophthalmology clinic with six weeks of eye irritation that had spiraled into something bizarre. Her complaint started simple enough: watery eyes, the sensation of something foreign stuck inside. But by the time she sought medical attention, her eyelids had begun doing something nobody should experience. They were flipping completely inside-out, a condition so unusual that most eye doctors might see it only a handful of times in their entire careers.

The case landed in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine because it offered something rare in modern medicine: a perfect teaching moment. Here was a patient whose dramatic physical symptom—eyelids literally turning inward—wasn't the actual problem that needed fixing. Instead, the solution came from an entirely different medical specialty, delivered not through surgical intervention but through something as simple as better sleep.

The condition is called floppy eyelid syndrome, or FES. The name sounds almost comedic, like something a cartoonist dreamed up. But for people experiencing it, there's nothing funny about chronic eye irritation, the inability to blink properly, and the frustration of having your eyes exposed and vulnerable throughout the day and night.

What makes this case particularly compelling is what it reveals about how interconnected our body's systems really are. Your eyelids aren't independent structures operating in isolation. They're connected to your overall respiratory health, your sleep quality, your weight, and your body's ability to maintain tissue integrity under stress. When something goes wrong upstream, your eyes are often the first to sound the alarm.

The real story here isn't about a weird eye condition. It's about sleep apnea, tissue degradation, oxidative stress, and why a good night's rest matters far more than most people realize. It's about how a condition that affects millions of people—obstructive sleep apnea—can manifest in ways that seem completely unrelated to breathing problems. And it's about how modern medicine, when done right, connects distant symptoms to root causes.

Let's unpack what happened in this case, why it happened, and what it teaches us about the hidden connections between sleep and seemingly unrelated physical symptoms.

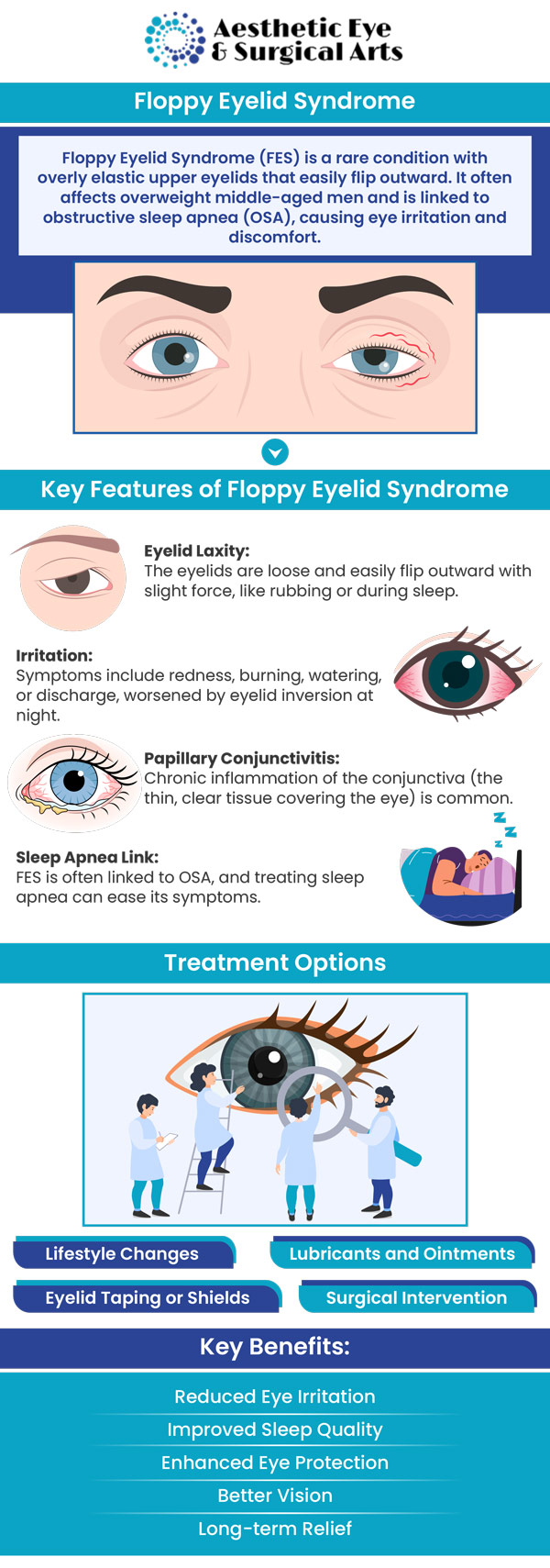

Understanding Floppy Eyelid Syndrome: Definition and Symptoms

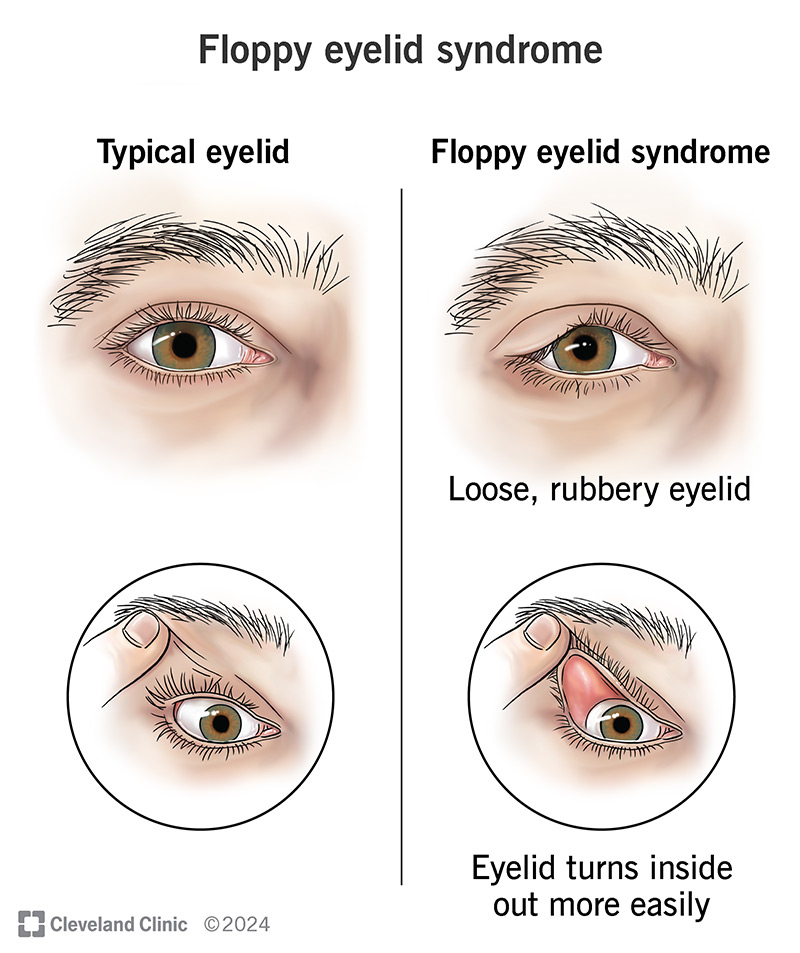

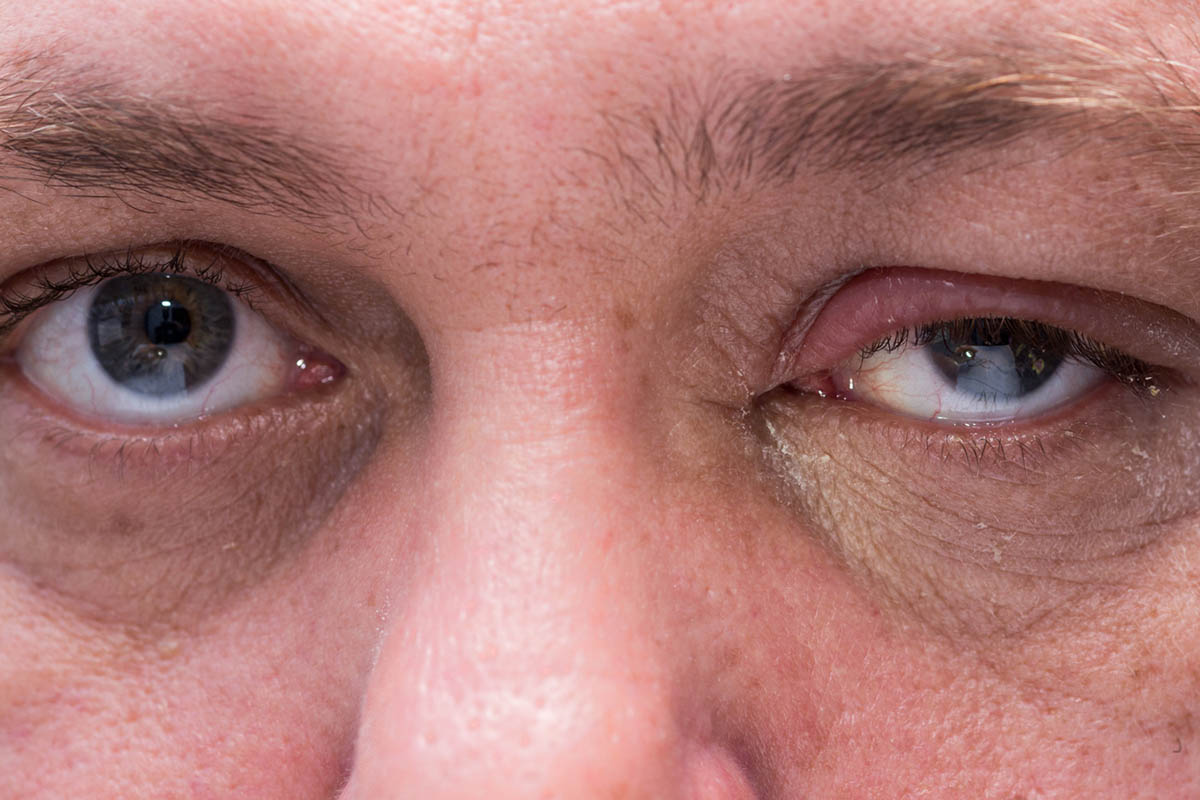

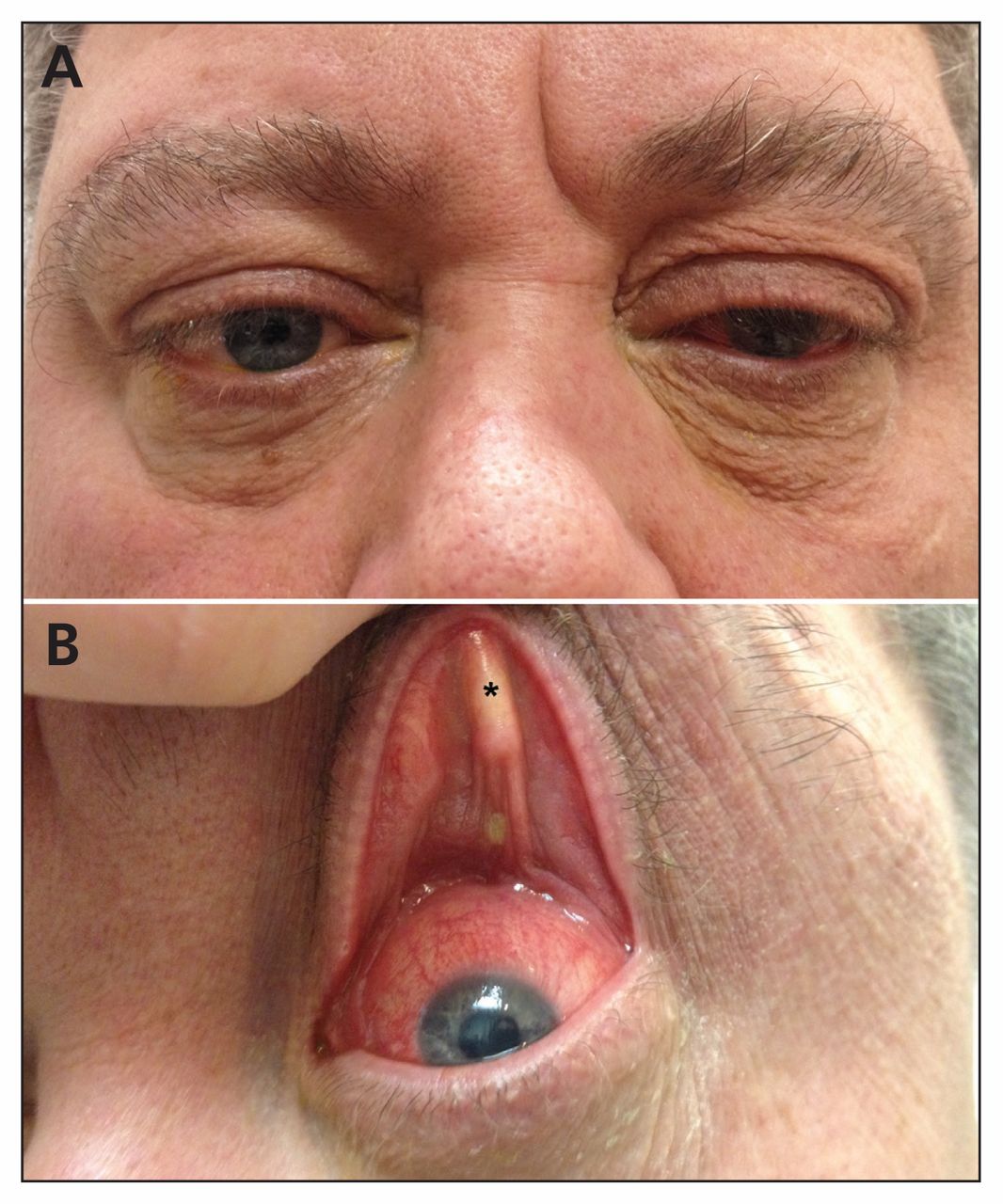

Floppy eyelid syndrome is a condition characterized by abnormally loose, hypermobile eyelids that lose their normal tension and structural integrity. The eyelids become lax, meaning they lack the natural firmness that keeps them in proper position. In severe cases like the Brooklyn patient's, the eyelids don't just sag—they physically flip upward and inward, potentially exposing the sensitive inner surface of the lid and the conjunctiva (the membrane covering the white of the eye).

The condition creates a cascade of eye problems. When your eyelid loses its normal tone, several things go wrong simultaneously. First, your eye can't close properly, which means the tear film—that thin layer of moisture protecting your eye—can't adequately coat the surface during sleep. This leads to exposure keratitis, where the cornea becomes irritated and damaged from being exposed to air and environmental irritants for hours.

Second, the lid loses its protective function during sleep. Your eyelids normally seal shut, creating a moisture chamber that protects your cornea during the hours you're unconscious. Without that seal, your cornea dries out. Patients report the sensation of having something perpetually stuck in their eye, constant grittiness, excessive tearing (paradoxically, as the eye overcompensates for dryness), and light sensitivity.

Third, the mechanical movement itself causes problems. When an eyelid flips inside-out repeatedly, the sensitive tissue on the inner surface gets rubbed against your cornea and the surrounding eye surface. Imagine rubbing sandpaper across the surface of your eye hundreds of times per day. That's the level of irritation we're talking about.

The symptoms patients report are remarkably consistent. There's the sensation of a foreign body in the eye that persists despite thorough examinations finding nothing actually stuck there. There's excessive tearing, especially upon waking. There's redness and bloodshot appearance. There's difficulty keeping eyes open during the day. Some patients report that their symptoms are worse immediately upon waking—a crucial detail that often points toward a sleep-related cause.

What's particularly important about FES is that most cases are preventable or manageable. The condition isn't usually a primary eyelid disease where something is fundamentally wrong with the eyelid tissue itself. Instead, FES is typically a secondary condition—a symptom of something else going wrong in the body. And that "something else" is frequently obstructive sleep apnea.

The diagnosis of FES can be confirmed through clinical examination. Doctors perform what's called the "snap test" or "eyelid traction test," where they gently pull the lower eyelid downward and then release it. In people with FES, the eyelid returns to its normal position slowly—or doesn't return to proper position at all. The eyelid simply doesn't have the elastic recoil it should have. On imaging or direct examination, the tarsal plate—the dense connective tissue that provides structural support to the eyelid—appears lax and degenerative.

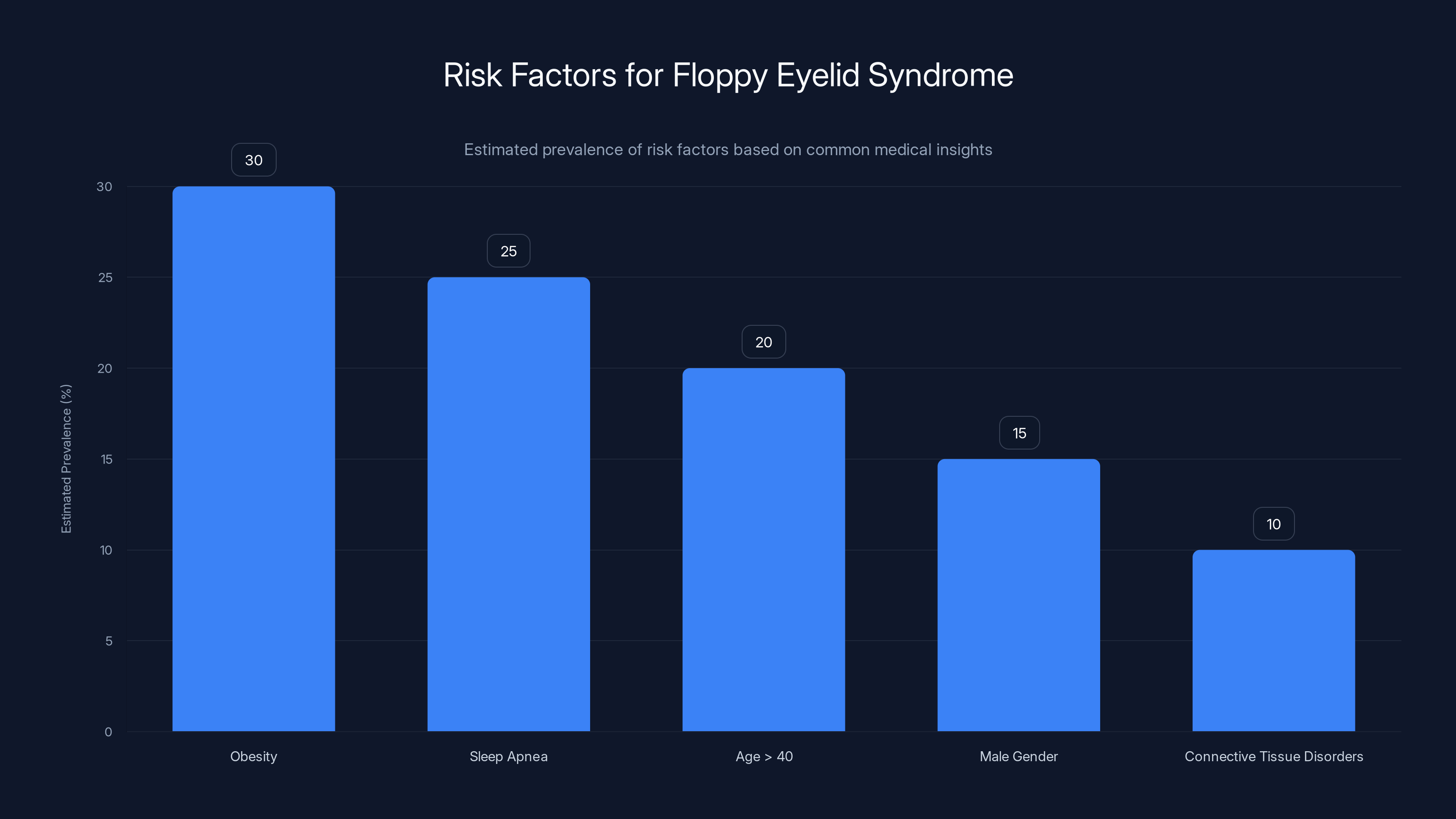

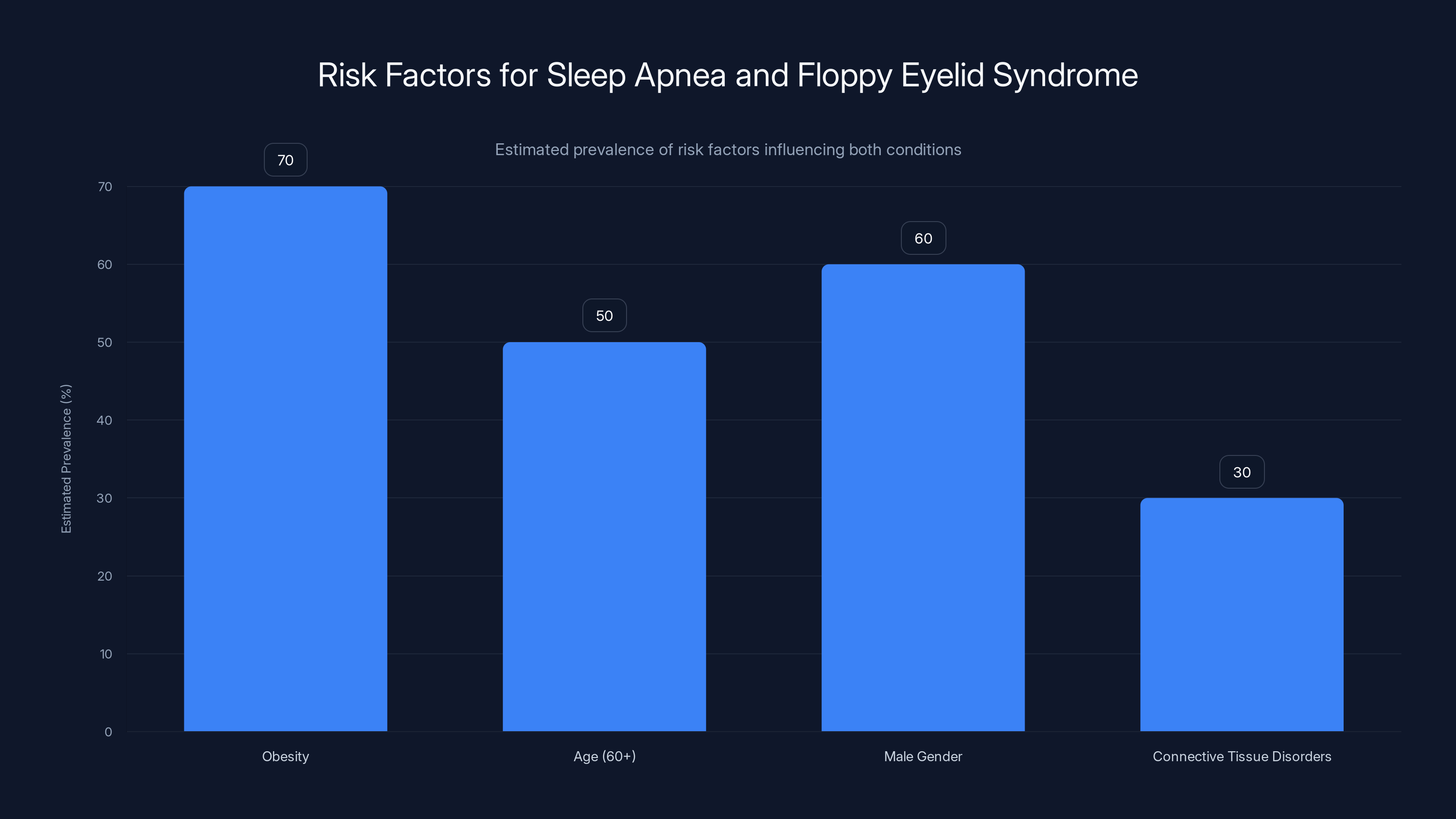

Obesity and sleep apnea are leading risk factors for floppy eyelid syndrome, with obesity estimated to affect 30% of those at risk. Estimated data.

The Connection Between Sleep Apnea and Drooping Eyelids

Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition where the muscles in the back of your throat relax too much during sleep, causing your airway to collapse partially or completely. This happens repeatedly throughout the night. Your brain detects the drop in blood oxygen levels and wakes you (often without you consciously realizing it) so you resume breathing. This pattern can occur dozens or even hundreds of times per night.

On the surface, sleep apnea seems to have nothing to do with your eyelids. Your eyelids don't control breathing. They're not involved in airway dynamics. There's no obvious anatomical connection between respiratory obstruction and eyelid tissue. Yet the Brooklyn patient had floppy eyelid syndrome, and when her sleep apnea was treated, her eyelid condition resolved rapidly.

The mechanism connecting these two conditions involves several interconnected pathways. When you have untreated sleep apnea, your body is experiencing repeated episodes of hypoxia—insufficient oxygen delivery to your tissues. Each time your airway collapses, blood oxygen levels drop. Your body's alarm systems activate. Your heart rate spikes. Your blood pressure surges. Stress hormones flood your bloodstream. Then, after a few seconds, you partially wake, your airway opens, oxygen levels normalize, and the cycle repeats.

This isn't just happening to your lungs and heart. Every tissue in your body is being subjected to these repetitive hypoxic-reoxygenation cycles. Your eyelid tissue is no exception. When tissue experiences low oxygen followed by reoxygenation, it generates excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS)—unstable molecules that damage cellular structures. This phenomenon is called oxidative stress.

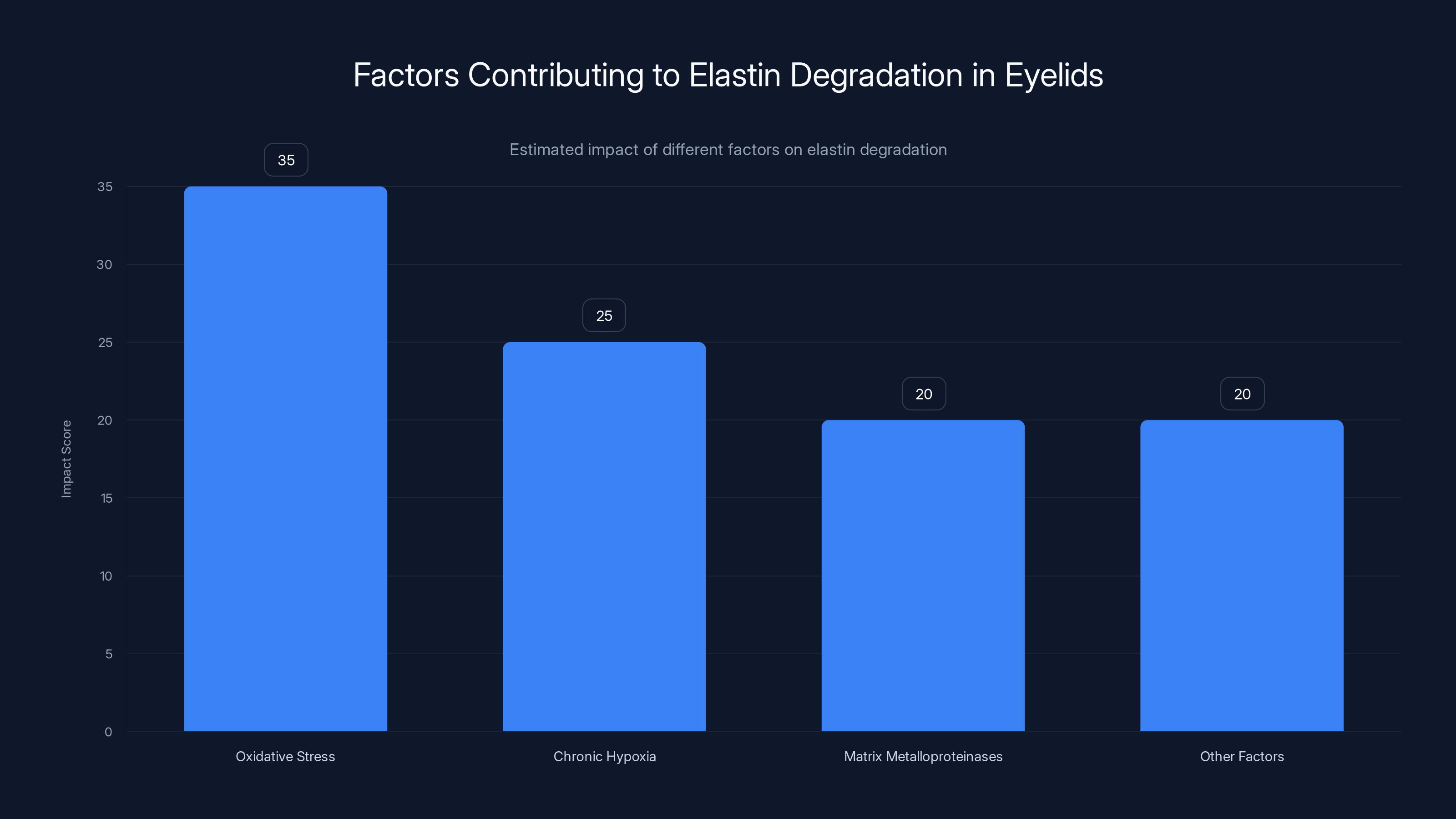

Oxidative stress triggers an inflammatory cascade and activates matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are enzymes that break down collagen and elastin—the proteins that give tissue its structural integrity and elasticity. Elastin is particularly crucial in eyelids. The tarsal plate of your eyelid contains elastin fibers that provide the normal tone and recoil that keeps your eyelids in proper position and allows them to close firmly.

When these elastin fibers are repeatedly damaged by oxidative stress from sleep apnea, they degrade. The eyelid loses its structural support. It becomes lax and hypermobile. It can sag, roll, and in severe cases, flip inside-out. It's the same mechanism that contributes to other age-related tissue problems and why people with chronic sleep apnea often show signs of premature aging throughout their bodies.

There's another factor at play. People with obstructive sleep apnea often have excessive daytime sleepiness, fragmented sleep architecture, and poor sleep quality. During these compromised sleep periods, the normal physiological repair mechanisms that should be occurring aren't working optimally. Your body should be using sleep time to repair damaged tissues and maintain structural integrity. When sleep is constantly interrupted by breathing events, these restorative processes fail. Your tissues don't heal properly. Damage accumulates.

Additionally, people with sleep apnea frequently have the physical characteristics that make sleep apnea more likely: obesity, enlarged adenoids or tonsils, large tongue, or anatomical features that predispose to airway collapse. Many of these same characteristics are associated with floppy eyelid syndrome. Excess weight and obesity are risk factors for both conditions. It's not clear whether obesity directly causes FES or whether it causes sleep apnea, which then causes FES, or whether both conditions share common underlying factors. But epidemiologically, the clustering is unmistakable.

The connections are so consistent that when an ophthalmologist encounters a patient with floppy eyelid syndrome, asking about sleep is now considered standard clinical practice. Questions about snoring, witnessed apneas, daytime sleepiness, and sleep quality should be part of the evaluation. If red flags appear, a sleep study should be recommended. This is exactly what happened with the Brooklyn patient, and it changed her clinical course entirely.

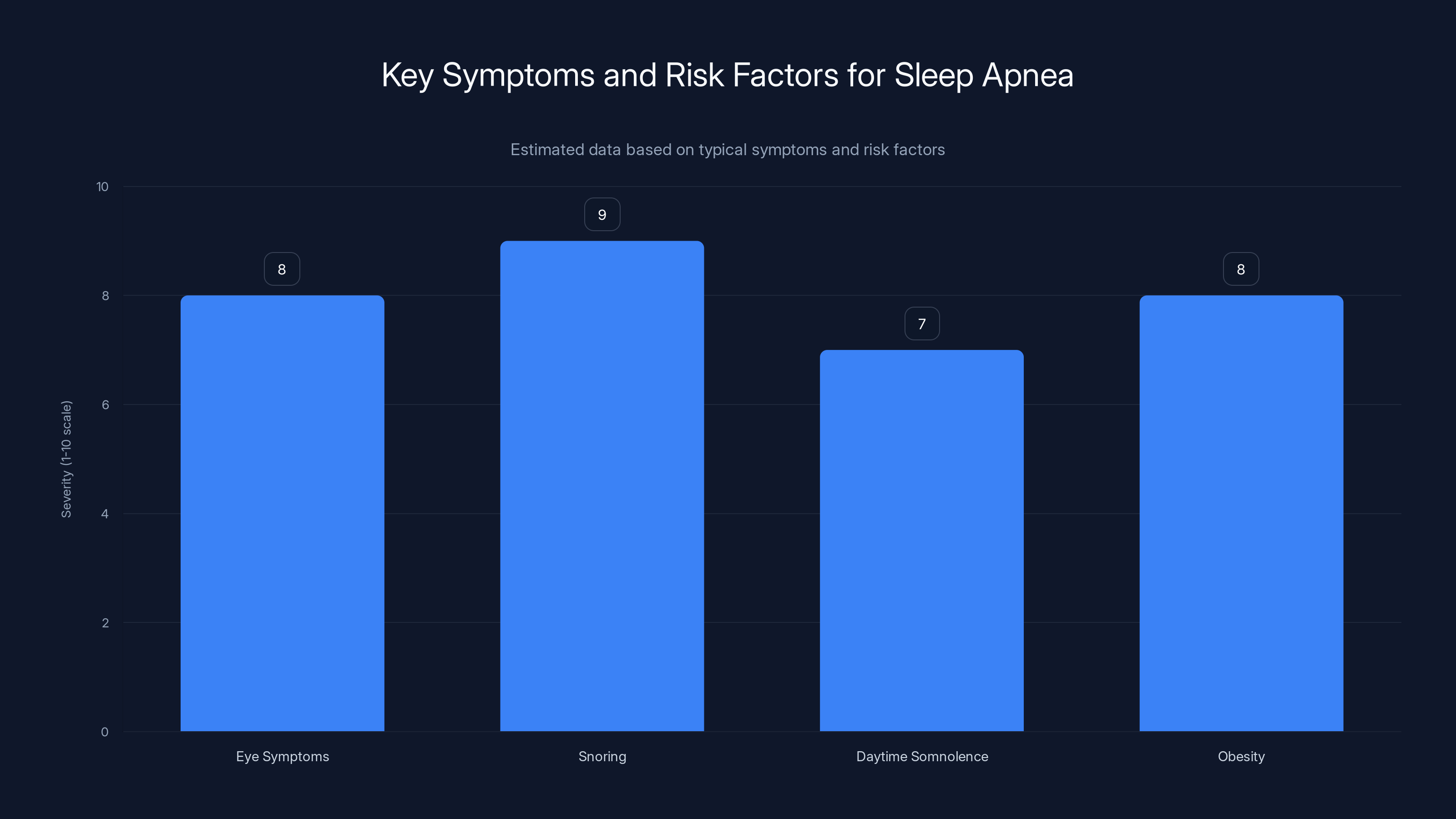

Estimated data showing the severity of symptoms and risk factors for sleep apnea in the case study. Snoring and obesity are significant contributors.

The Case Study: From Confused Eyes to Diagnosed Sleep Apnea

The patient was a 39-year-old woman who presented to the ophthalmology clinic with a six-week history of eye symptoms. Initially, she experienced a foreign body sensation and excessive tearing. Both eyes were affected, and neither symptom was improving despite time and basic self-care. When she finally sought professional evaluation, the situation had escalated.

During the clinical examination, the ophthalmologists observed several key findings. Her eyes were bloodshot—the conjunctiva was intensely inflamed and reddened. More strikingly, her eyelids were drooping severely, and critically, she was unable to fully close them. This inability to fully close the eyes, called lagophthalmos, is itself concerning because it prevents proper eye lubrication and protection during sleep.

When the doctors performed the snap test, attempting to gently pull her lower eyelid downward and then observing its return to normal position, the eyelid didn't recoil normally. Instead, it curled and remained lax. They attempted to manually elevate her upper eyelids, and instead of encountering normal resistance from healthy tissue, the lids felt remarkably limp. The tissue quality was clearly abnormal.

But here's what proved to be the critical part of the evaluation: the doctors asked about her sleep. The patient reported that she snored at night and experienced significant daytime somnolence. She was tired during the day despite spending adequate time in bed. Most tellingly, her eye symptoms were worst when she first woke up in the morning—exactly the pattern you'd expect if the underlying problem was something that happened during sleep.

The patient also had obesity, which the doctors noted in their assessment. Obesity is a major risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea because excess weight in the neck increases the likelihood of airway collapse during sleep. In the context of a patient with lax eyelids, snoring, daytime sleepiness, and obesity, the pattern became clear to the clinicians: this wasn't a primary eyelid problem requiring eye surgery. This was a symptom of sleep apnea.

The standard diagnostic test for sleep apnea is polysomnography, commonly called a sleep study. The patient underwent this test, which monitors multiple physiological parameters throughout the night: heart rate, blood oxygen levels, breathing patterns, brain waves, eye movements, muscle tone, and sleep stages. The results were unambiguous. She had obstructive sleep apnea with an apnea-hypopnea index of 27 events per hour. This classified as moderate-level sleep apnea—not the most severe, but certainly significant enough to cause physiological damage and warrant immediate treatment.

The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is the standard metric for sleep apnea severity. It counts the number of times per hour that your breathing either completely stops (apnea) or becomes significantly shallow (hypopnea, typically defined as a 50% reduction in airflow). An AHI of 27 means this patient's breathing was being significantly disrupted about 27 times every hour she slept. Over an eight-hour night, that's potentially 216 disruptions. Night after night, her tissues were experiencing hypoxia and oxidative stress.

Once the diagnosis was confirmed, treatment began immediately. The gold standard treatment for obstructive sleep apnea is continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP therapy. A CPAP machine delivers pressurized air through a mask worn over the nose (or nose and mouth) throughout the night. This continuous pressure splints the airway open, preventing collapse. With the airway maintained, breathing remains unobstructed, blood oxygen levels stay normal, and the hypoxic-reoxygenation cycles stop.

The patient also received conservative eye care: lubricating eye drops to address the dryness and irritation, protective eye patches to wear at night to ensure her eyes stayed closed and protected during sleep, and a referral for weight loss management. Weight loss would address both the sleep apnea and improve overall health.

The results were remarkable. Within just two weeks of CPAP therapy, her eyelids were no longer flipping inside-out. She could now properly close her eyes. The daytime somnolence that had plagued her resolved—she was no longer struggling to stay awake. Her eye symptoms improved dramatically. The conjunction went from intensely bloodshot to normal. The foreign body sensation disappeared.

What's striking about this case is the timeline. The eyelid problem didn't resolve over months or years of gradual healing. It resolved within weeks. This rapid improvement suggests that the problem wasn't permanent structural damage (at least not yet) but rather an active, ongoing process—tissue degradation happening in real-time due to the sleep apnea. Once the hypoxic stress stopped, the body's natural healing processes kicked in and the tissue began recovering.

The Biology Behind the Breakdown: Elastin Degradation in Eyelids

To understand why sleep apnea damages eyelid tissue specifically, we need to look at the anatomy and biology of the eyelid. The upper eyelid has several distinct structural layers, and they work together to create that smooth, coordinated blink that happens dozens of times per minute without you consciously thinking about it.

The key structural component is the tarsal plate, a dense band of connective tissue that sits within the eyelid like a supporting framework. This isn't soft, squishy tissue. It's firm, organized connective tissue made up of collagen fibers and elastin. The tarsal plate is what gives your eyelid its shape and firmness. It's why when you close your eyes, your eyelid maintains its form rather than just collapsing into a wrinkled mess.

Elastin is a protein that's absolutely crucial for tissues that need to be stretchy yet retain their original shape. Think of it like the difference between a rubber band and a piece of string. String doesn't snap back when you stretch it. A rubber band does. Elastin is the body's version of that rubber band material. Ligaments, arteries, and eyelids all depend on elastin to stretch during movement and then snap back to their normal configuration.

In floppy eyelid syndrome, histological studies—microscopic examinations of the actual tissue—reveal something striking: the elastin fibers in the tarsal plate are significantly reduced or morphologically abnormal. The tissue looks degraded. The normal architecture of elastin fibers is disrupted. When you lose elastin, you lose the ability for tissue to return to its normal shape after stretching. This is exactly what happens in FES.

What causes this elastin loss? Research has identified several potential mechanisms. First, there's the oxidative stress mechanism we discussed. Chronic hypoxia from sleep apnea generates reactive oxygen species that damage elastin molecules. Matrix metalloproteinases are activated and break down existing elastin. The body's antioxidant defense systems are overwhelmed by the volume of oxidative stress being generated.

Second, there's the chronic inflammation component. Sleep apnea triggers systemic inflammation—elevated levels of inflammatory markers throughout the body. These inflammatory molecules can directly contribute to tissue remodeling and degradation. Your eyelid tissue is being bathed in pro-inflammatory signals night after night.

Third, there may be mechanical factors. During sleep apnea events, your body makes intense muscular efforts to overcome the airway obstruction and resume breathing. Some researchers have hypothesized that these intense respiratory efforts might create unusual mechanical stresses on eyelid tissue, contributing to degeneration over time. The evidence for this is less clear, but the timing and association are suggestive.

Fourth, sleep deprivation itself is harmful to tissue health. Sleep is when your body conducts essential maintenance and repair. Growth hormone is released predominantly during deep sleep. Protein synthesis increases. Cellular repair mechanisms activate. When your sleep is fragmented by constant breathing events, these restorative processes can't function optimally. Your tissues aren't being adequately maintained. Combined with the active damage being caused by hypoxia and inflammation, this creates a net loss situation where damage exceeds repair.

What's interesting is that not everyone with sleep apnea develops floppy eyelid syndrome, and not everyone with floppy eyelid syndrome has sleep apnea. This suggests that there are additional factors at play. Genetic predisposition appears to be involved. Some people may have naturally lower elastin production or reduced antioxidant capacity, making their eyelid tissue more vulnerable to degradation. Some may have inherited anatomical features that predispose to both eyelid laxity and airway collapse.

Underlying connective tissue disorders might play a role. Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which affects collagen and elastin production throughout the body, increase the risk of floppy eyelid syndrome. People with these systemic connective tissue problems often show manifestations across multiple tissues—their skin might be hyperextensible, their joints might be hypermobile, their eyelids might be lax. The sleep apnea might exacerbate these pre-existing vulnerabilities.

What's clear, though, is that sleep apnea is a major modifiable risk factor. When you treat the sleep apnea, the condition often improves dramatically, as we saw with the Brooklyn patient. This suggests that in many cases of FES, the sleep apnea is the primary driver, and the oxidative stress and inflammation it causes are actively destroying the eyelid tissue. Stop the sleep apnea, stop the destructive process, and allow tissue healing to proceed.

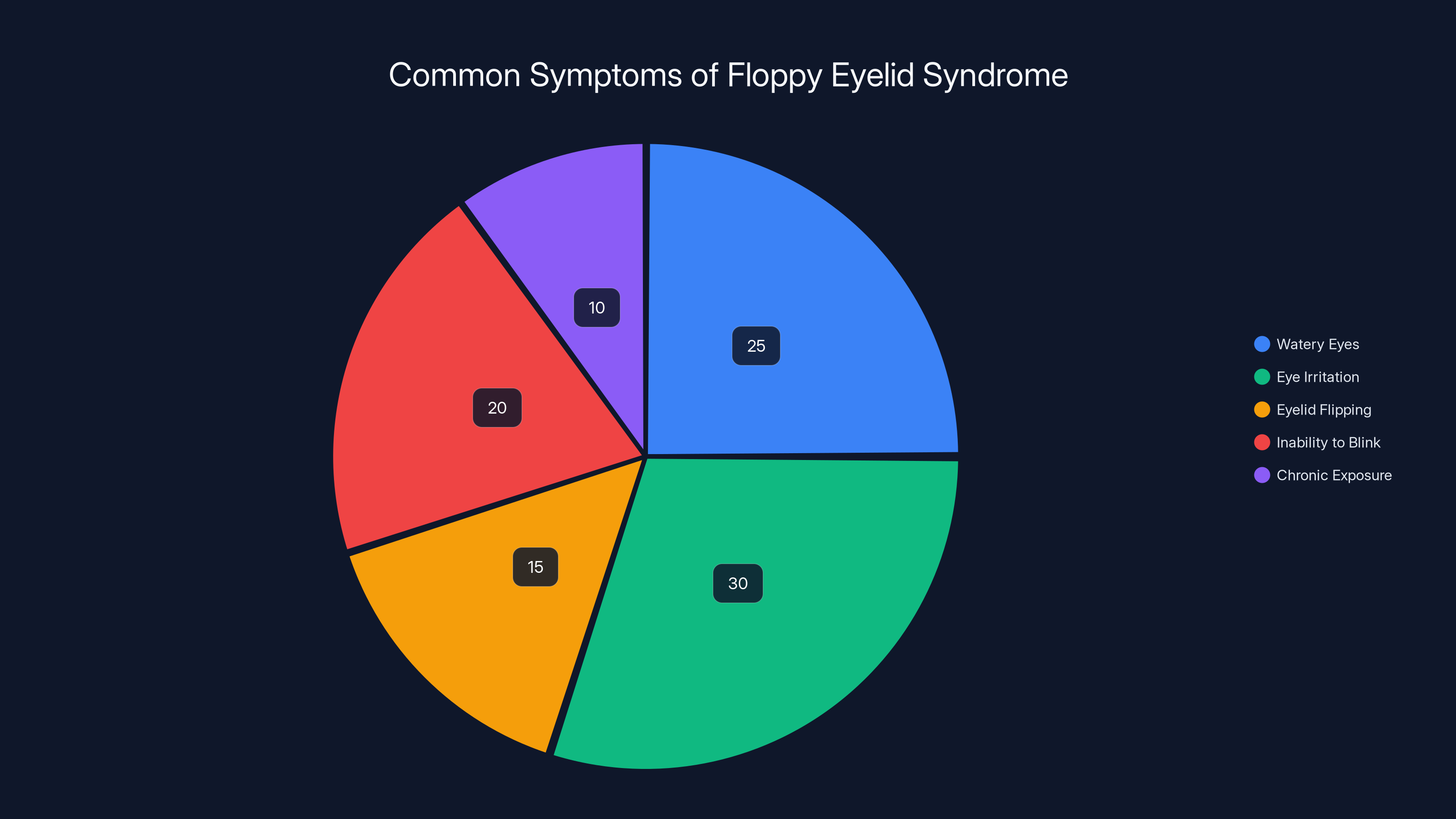

Estimated data shows that eye irritation and watery eyes are the most common symptoms of Floppy Eyelid Syndrome, highlighting the condition's impact on daily comfort.

Sleep Apnea's Widespread Impact: Beyond Just Breathing

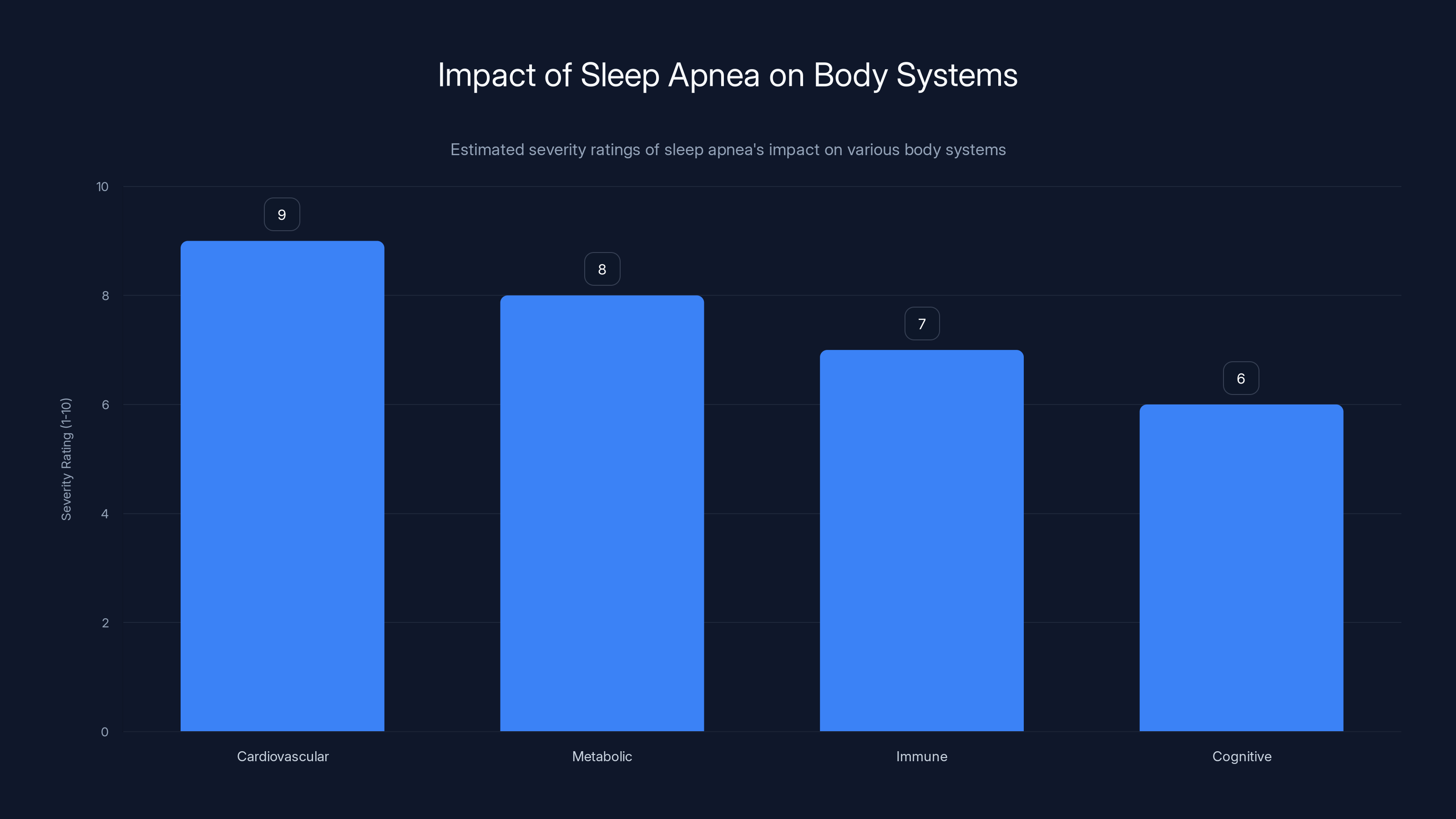

Floppy eyelid syndrome is actually just one of many manifestations of untreated sleep apnea. The condition affects virtually every system in your body, and the visible symptoms in one area often reflect damage happening throughout your body.

The cardiovascular system bears a particularly heavy burden. Sleep apnea causes repeated blood pressure spikes as your body's stress response activates during each breathing event. Night after night, your blood pressure surges from 120/80 to potentially 160/100 or higher, dozens of times per hour. Over months and years, this chronic intermittent hypertension damages blood vessels. Arterial walls thicken. Plaque deposits form. Endothelial function deteriorates. The result is a dramatically elevated risk of heart attack and stroke.

The metabolic system suffers as well. Sleep apnea impairs insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation. People with untreated sleep apnea have higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes, independent of their weight. The sleep fragmentation disrupts hormones that regulate appetite and satiety, making it harder to maintain a healthy weight. The systemic inflammation contributes to metabolic dysfunction.

The immune system is compromised. During sleep, your immune system undergoes essential maintenance and consolidation. Immune cells proliferate. Antibodies are produced. Infection-fighting capacity is optimized. When your sleep is fragmented by breathing events, these immunological processes are interrupted. People with sleep apnea have higher rates of infections and potentially even higher cancer risk, though the cancer association remains an area of active research.

Cognitive function declines. The repeated arousals and oxygen drops affect brain function. Attention, memory, and processing speed are all impaired. Some research suggests that chronic sleep apnea might increase dementia risk over decades, though this remains an area of investigation.

Muscle quality deteriorates. The chronic hypoxia and systemic inflammation associated with sleep apnea accelerate muscle loss and reduce muscle strength. The sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) that normally develops over decades can be significantly accelerated in people with untreated sleep apnea.

And throughout all of this, your tissues are experiencing repeated cycles of hypoxia and oxidative stress. Skin shows signs of premature aging. Bones experience accelerated loss. Connective tissues degrade. The eyelids, being relatively fragile tissue with high elastin content, are particularly vulnerable, which is why FES often appears in the clinical picture.

The point is that when you treat sleep apnea and dramatically improve oxygenation and reduce the hypoxic-reoxygenation cycles, you're not just fixing one symptom. You're starting to reverse damage across multiple systems. The fact that the Brooklyn patient's eyelids improved rapidly with CPAP therapy is actually a window into the broader healing that her whole body was undergoing.

Risk Factors That Predispose to Both Sleep Apnea and Floppy Eyelids

Certain characteristics make someone more likely to develop both sleep apnea and floppy eyelid syndrome. Understanding these risk factors is important because they're often modifiable, and addressing them can prevent or improve both conditions.

Obesity is the most significant modifiable risk factor. Excess weight in the neck increases the likelihood that your airway will narrow during sleep. The soft tissues in the throat are heavier, pulling downward during sleep when muscles relax. The extra weight also increases abdominal pressure, which can affect breathing mechanics and reduce oxygen levels. People with obesity are dramatically more likely to have sleep apnea. They're also more likely to have floppy eyelid syndrome, possibly through the sleep apnea pathway, or possibly because obesity itself is associated with systemic inflammation and connective tissue changes.

Age is a risk factor that increases the likelihood of both conditions. As we age, tissue loses elastin naturally. The tarsal plates of our eyelids naturally lose some structural support over decades. Simultaneously, age-related changes in the airway—loss of muscle tone, changes in fat distribution, narrowing from age-related structural changes—increase sleep apnea risk. The combination of age-related tissue changes plus the damage from sleep apnea creates a particularly vulnerable situation for older adults with sleep apnea.

Male gender is a major risk factor. Men develop sleep apnea at higher rates than women, at least until women reach menopause. This might reflect differences in body composition, fat distribution, or airway anatomy. Men also appear to have higher rates of floppy eyelid syndrome. Why men are more susceptible is not entirely clear, but hormonal factors may play a role.

Underlying connective tissue disorders significantly increase risk. Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, or other collagen-related disorders affect elastin and collagen production throughout the body. People with these conditions often have tissue laxity in multiple locations—hyperextensible skin, hypermobile joints, and lax eyelids. The additional stress of sleep apnea on already-compromised connective tissue creates a situation where FES develops more readily.

Large neck circumference is a specific anatomical risk factor. Irrespective of overall body weight, having a thick neck increases sleep apnea risk because of the anatomical constraints on the airway space. A neck circumference greater than 16 to 17 inches for women and 17 to 18 inches for men is associated with significantly elevated sleep apnea risk.

Facial anatomy plays a role. Having a naturally narrower airway, a recessed chin, a large tongue, or enlarged adenoids/tonsils all increase sleep apnea risk. Some people are anatomically predisposed to airway collapse simply based on the structure they were born with. These same anatomical features might also predispose to eyelid laxity or make the tissue more vulnerable to damage.

Alcohol and sedative use exacerbate sleep apnea significantly. These substances relax the muscles of the airway, making collapse more likely. They also suppress rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which disturbs normal sleep architecture. Someone with mild sleep apnea might become symptomatic when regularly drinking alcohol. The same might be true for eyelid symptoms—the person might manage well until they start a medication that relaxes muscles, at which point eyelid symptoms emerge.

Sleep position matters. Sleeping on your back significantly worsens obstructive sleep apnea because gravity works against you—your tongue and soft tissues collapse backward into your airway. Side sleeping is generally better for sleep apnea. This is one reason why even without other treatments, sleeping on your side can sometimes provide symptom relief.

Nasal obstruction from any cause—deviated septum, nasal polyps, chronic sinusitis, seasonal allergies—increases sleep apnea severity because it forces you to mouth-breathe, which predisposes the throat tissues to collapse during sleep.

Estimated data shows that sleep apnea has the most severe impact on the cardiovascular system, followed by metabolic, immune, and cognitive systems.

Treatment Approaches: From Conservative Management to CPAP

The treatment hierarchy for floppy eyelid syndrome depends on severity and whether an underlying sleep apnea is present. For the Brooklyn patient, the primary treatment was CPAP therapy for her sleep apnea, which addressed the root cause and allowed her eyelids to heal.

Conservative measures form the foundation of treatment. If sleep apnea is identified, CPAP (or alternative positive airway pressure devices like Bi PAP or APAP) should be started immediately. This removes the hypoxic stress that's driving the tissue degradation. CPAP therapy is highly effective—studies show that 90% or more of patients using CPAP appropriately see significant improvements in sleep apnea-related symptoms and physiological markers.

For the eye-specific symptoms while waiting for improvement or if CPAP isn't immediately available, lubricating eye drops help manage the dryness and irritation. These aren't just comfort measures; they're protective. Adequate tear coverage prevents further damage to the exposed cornea. Using drops four to six times daily is common. At night, protective eye patches can be worn to ensure the eyes stay closed and protected during sleep.

Weight loss is important for both conditions. If obesity is contributing to the sleep apnea, even a 10% weight loss can significantly improve apnea severity. Sleep apnea often shows a dose-response relationship with weight—lose weight, improve apnea. Similarly, weight loss is generally beneficial for overall tissue health and reduces systemic inflammation, potentially helping eyelid tissue heal.

Nasal obstruction should be addressed. If someone has a deviated septum or nasal polyps contributing to mouth breathing, surgical correction might help sleep apnea severity and could improve CPAP tolerance (patients often find CPAP more tolerable when their nasal passages are open).

Sleep position modification—sleeping on your side rather than your back—can help some people with mild sleep apnea. While not a complete solution for moderate-to-severe apnea, positional therapy can provide some benefit and is worth implementing alongside other treatments.

Alcohol cessation is crucial. If someone with sleep apnea is drinking regularly, eliminating alcohol can dramatically improve apnea severity and sleep quality. Even just avoiding alcohol in the evening can help, since alcohol consumed near bedtime has a particularly strong relaxant effect on airway muscles.

Despite these measures, some people don't improve adequately or develop complications that require more aggressive intervention. In these cases, surgical treatment of the eyelid itself might be necessary. Surgical approaches involve tightening the tarsal plate or the ligaments that support the eyelid, essentially removing excess lax tissue and creating a more normal eyelid structure. This is typically done as an outpatient procedure and can be quite effective. However, surgery on the eyelid carries risks like infection, asymmetry, or over-correction, which is why conservative management is always tried first.

Recognizing When Your Eyelids Might Be Telling You Something

Floppy eyelid syndrome is rare enough that many people experiencing it will see multiple doctors before getting the correct diagnosis. Some will be told they have allergies causing the drooping. Others will be offered eye surgery when the real problem is in their sleep. Knowing what to watch for can help you seek appropriate care faster.

The most important warning sign is asymmetric or worsening eyelid drooping, especially if it appears relatively suddenly. Everyone's eyelids sag a bit with age, but if you notice your eyelids becoming noticeably looser over weeks to months, that's worth investigating. If the drooping is worse on one side than the other, that's particularly concerning and should be evaluated to rule out neurological causes (though FES is typically bilateral, affecting both eyes equally).

Eyelid symptoms that are worst in the morning suggest a sleep-related component. If you wake up with gritty eyes, excessive tearing, or your eyelids feel particularly loose first thing in the morning but improve somewhat during the day, this is a clue that the problem is something happening during sleep.

If you have eyelid symptoms AND you snore or have daytime sleepiness, the combination is almost diagnostic of sleep apnea with secondary FES. Don't brush off these symptoms as separate, unrelated problems. Connect them. Ask your doctor whether they think sleep apnea might be involved.

If standard eye treatments aren't working—if lubricating drops help temporarily but the problem keeps returning, if your eye doctor has checked for infections and allergies and found nothing, if the symptoms seem out of proportion to what they can see on examination—again, sleep should be suspected as a potential underlying cause.

If you're a man, overweight, over 40, and have any combination of eyelid symptoms, snoring, and daytime tiredness, you're in a demographic at particularly high risk for both sleep apnea and FES. The same applies if you have a family history of sleep apnea or connective tissue disorders.

One unusual but highly specific sign is what's called the "reverse ptosis" or the "reverse blepharoptosis" phenomenon. Your upper eyelid appears to be lower when you first wake up, almost like you have ptosis (drooping), but then it seems to improve somewhat as the day goes on. This happens because the loose eyelid is being held down by its own laxity at first, but as your eyes warm up and tissues warm and move, gravity shifts slightly and the eyelid drifts upward. If this pattern sounds familiar, a sleep evaluation is warranted.

Oxidative stress is estimated to have the highest impact on elastin degradation in eyelids, followed by chronic hypoxia and matrix metalloproteinases. Estimated data.

The Bigger Picture: How Rare Symptoms Reveal Common Diseases

The Brooklyn patient's case is compelling not just because it's unusual but because it demonstrates a fundamental principle of medicine: rare presentations of common diseases are worth investigating. Obstructive sleep apnea affects roughly 1 billion people worldwide and is dramatically underdiagnosed. Most people with sleep apnea don't know they have it. They experience symptoms—daytime sleepiness, poor concentration, high blood pressure, erectile dysfunction, morning headaches—but don't connect these symptoms to a sleep disorder.

Floppy eyelid syndrome is rare, but obstructive sleep apnea is extremely common. When a patient presents with the rare symptom (drooping eyelids), it should raise suspicion of the common underlying condition (sleep apnea). This is how medicine works: you use the unusual presentation as a diagnostic clue that points toward something more prevalent.

This principle extends to other symptoms too. Unexplained hypertension that's difficult to control? Screen for sleep apnea. Atrial fibrillation appearing in someone without obvious cardiac disease? Check for sleep apnea. Erectile dysfunction in middle-aged men? Sleep apnea should be on the differential diagnosis list. Accelerated cognitive decline in older adults? Sleep apnea might be contributing.

The treatment implications are significant. Many medical conditions being treated with medications might improve dramatically if the underlying sleep apnea were identified and treated. Someone on three antihypertensive medications might control their blood pressure better with CPAP than with additional medication. Someone on medication for atrial fibrillation might have better rhythm control if sleep apnea were treated. The cascading benefits of treating the root cause are often profound.

This is why the Brooklyn patient's case was published in a prestigious journal and is worth remembering. It serves as a reminder that good medicine sometimes requires thinking beyond the obvious, connecting seemingly distant symptoms, and investigating the uncommon presentation of common diseases. When you see something unusual, ask whether it might be a window into a more prevalent problem affecting your patient's entire body.

Future Research: Understanding Why Some Tissues Degrade While Others Don't

While the basic mechanism connecting sleep apnea to FES is understood—hypoxia, oxidative stress, elastin degradation, inflammation—many questions remain. Why are some tissues more vulnerable than others? Why do some people with severe sleep apnea never develop obvious eyelid problems, while others with milder apnea do?

Researchers are investigating whether specific genetic variations predispose to elastin vulnerability. Some people might have genetic polymorphisms that affect elastin production rates or elastin quality. Others might have variations in antioxidant enzyme genes that make their cells more susceptible to oxidative damage. Identifying these genetic factors could eventually allow for personalized risk assessment and targeted interventions.

The role of sleep architecture is also being studied. Different types of sleep apnea events—obstructive versus central apneas, events that occur predominantly during REM sleep versus NREM sleep—might have different tissue effects. Understanding whether certain sleep apnea patterns create more tissue damage than others could influence treatment strategies.

The connective tissue biology itself is an active area of investigation. What exactly happens to elastin fibers under chronic hypoxic stress? Are they being actively broken down by increased MMP activity, or are they failing to be produced at normal rates? Are there differences between adults and children in how their tissue responds to hypoxia? Could there be interventions that boost elastin production or reduce elastin breakdown, beyond simply treating the sleep apnea?

The role of systemic inflammation and specific inflammatory markers is also being clarified. Different inflammatory pathways might predominate in different individuals, which could explain why some people with similar sleep apnea severity have vastly different clinical manifestations. Could specific anti-inflammatory interventions help some patients more than others?

There's also interest in understanding the timeline of recovery. The Brooklyn patient improved dramatically within weeks. But how quickly can eyelid elastin truly regenerate once the hypoxic stress is removed? Are there ways to enhance tissue healing beyond simply treating the apnea? Could antioxidant supplementation or other interventions speed recovery?

Obesity is the most prevalent risk factor for both sleep apnea and floppy eyelid syndrome, followed by male gender and age. Estimated data.

Practical Steps If You Suspect Sleep Apnea or Eyelid Issues

If you recognize yourself in this discussion—if you snore, feel tired despite enough sleep, have drooping eyelids, or have been struggling with unexplained eyelid problems—here's what you should do.

First, document your symptoms. Write down when they're worst, whether you snore (ask family members if you're not sure), whether you wake up gasping or choking, whether you have morning headaches or dry mouth, whether you have difficulty concentrating during the day, and whether your mood seems affected. This detailed symptom picture is valuable when talking with healthcare providers.

Second, discuss your symptoms with your primary care physician. Describe the eyelid symptoms, the daytime sleepiness, the snoring—the whole picture. Ask specifically whether you should be screened for sleep apnea. If your doctor isn't convinced, you can request a referral to a sleep specialist directly. You don't always need your primary care doctor's referral to see a specialist.

Third, if a sleep study is recommended, do it. Home sleep apnea tests are now quite good and much more convenient than laboratory sleep studies. Most can be done in your own bed. They monitor your breathing, blood oxygen levels, and heart rate throughout the night, which is sufficient for diagnosing sleep apnea in most cases.

Fourth, if sleep apnea is diagnosed, commit to treatment. CPAP can be challenging at first for some people—the mask needs to fit right, the pressure needs to be adjusted, and it takes a week or two to get used to wearing it. But most people find it manageable, and the benefits are substantial. Tiredness resolves, clarity returns, blood pressure improves. Stick with it through the adjustment period.

Fifth, use the eyelid symptoms as an opportunity to address your whole-person health. Sleep apnea isn't just an eyelid problem. It's a sign that your tissues are being damaged throughout your body. Use that as motivation to take the diagnosis seriously, optimize other aspects of your health, work toward weight loss if needed, and commit to long-term treatment and monitoring.

Sleep as Medicine: The Underrated Treatment We All Overlook

The deepest insight from the Brooklyn patient's case is simpler than all the biochemistry and tissue biology. Sleep fixed her eyelids. Not surgery. Not eye drops. Not medication. Sleep.

We live in a culture that treats sleep as optional, as something to be minimized in pursuit of productivity. We wear our sleeplessness like a badge of honor. "I only need five hours," someone will boast. "I'll sleep when I'm dead." There's almost a shame associated with valuing sleep, as if needing rest means you're weak or lazy.

But the evidence is overwhelming: sleep isn't a luxury. It's a fundamental biological necessity. Your eyelids can't stay healthy without it. Your heart can't stay healthy without it. Your brain can't stay healthy without it. Your immune system can't stay healthy without it. Your entire body's capacity to repair itself, to synthesize new proteins, to clear toxins, to consolidate memory, to regulate metabolism—all of these depend on adequate, good-quality sleep.

When we deprive ourselves of sleep, or when underlying conditions like sleep apnea fragment our sleep, we're not just feeling tired. We're triggering a cascade of physiological dysfunction. Tissues degrade. Blood vessels suffer. Metabolism dysregulates. Cognitive function declines. And sometimes, somewhere on your body, a symptom appears—drooping eyelids, stubborn hypertension, unexpected heart rhythm problems, accelerated aging—and we treat that symptom while ignoring the fact that the root problem is sleep.

The Brooklyn patient didn't need her eyelids fixed surgically. She needed sleep apnea treatment, which allowed her to finally sleep properly. That's a profound lesson for all of us. So much of modern medicine focuses on adding treatments—medications, procedures, interventions. Sometimes the most powerful treatment is removing the obstacle preventing a natural process from happening. Remove the airway obstruction, allow normal sleep, and the body heals itself.

This doesn't mean sleep is a cure-all or that proper sleep will solve every health problem. Some conditions do require active medical intervention. But the starting point should always be: are you sleeping well? If not, why not? And what would it take to improve your sleep?

The Overlooked Diagnosis: Why Sleep Apnea Remains Underdiagnosed

Despite affecting roughly 1 billion adults worldwide, obstructive sleep apnea remains diagnosed in only about 20% of people who have it. Why is such a common condition so consistently missed?

Part of the problem is that sleep apnea doesn't have obvious symptoms that immediately shout "see a doctor." You're not coughing up blood. You're not having chest pain. You're just tired—but many people are tired, and they attribute it to work stress, their schedule, aging, or simply their personality type. Some people are naturally less alert than others, they think. They don't realize that what feels normal to them is actually a symptom.

Another barrier is that many physicians don't have training in recognizing sleep apnea. A patient might visit their doctor multiple times mentioning daytime sleepiness or fatigue, and the doctor might attribute it to depression, hypothyroidism, or simple deconditioning—conditions they can diagnose with standard tests. Sleep apnea doesn't show up on routine blood work. It requires thinking about the possibility and ordering a specific test.

There's also a cultural divide between different medical specialties. An ophthalmologist treating floppy eyelids might not ask about sleep. A cardiologist treating hypertension might not screen for sleep apnea. A neurologist treating cognitive decline might not consider sleep apnea as a contributing factor. Each specialty focuses on their organ system, and the connecting thread—sleep—gets missed.

Access to sleep testing is another practical barrier. In some regions, sleep specialists aren't readily available. Formal laboratory sleep studies are expensive and inconvenient (though home sleep tests are improving access). Insurance coverage varies. The result is that many people who would benefit from diagnosis and treatment never get tested.

There's also a component of medical bias. Sleep apnea is more common in men, in older adults, and in people with obesity. Patients in these demographics sometimes feel that their symptoms are being dismissed or attributed to "just getting older" or "just needing to lose weight." While weight loss can help, it shouldn't be used as an excuse to not diagnose and treat sleep apnea. Someone can be overweight and still benefit from sleep apnea treatment. The two aren't mutually exclusive.

Finally, there's the challenge of perception. Sleep apnea doesn't sound serious to many people. "I stop breathing for a few seconds at a time?" They might minimize the symptom. But those brief moments add up. Over a lifetime, they cause profound cumulative damage. The person who dismisses their sleep apnea as "not a big deal" doesn't realize they're slowly damaging their heart, brain, eyelids, and virtually every other organ.

Overcoming these barriers requires better education—both for physicians and patients. When rare symptoms like floppy eyelids appear, they should trigger investigation for common underlying causes like sleep apnea. When anyone reports daytime sleepiness or fatigue, sleep apnea should be high on the differential diagnosis list. And patients should be empowered to advocate for sleep testing if they suspect a problem.

Lifestyle Optimization: Building Sleep That Actually Heals

Once you've ruled out sleep apnea and know you can sleep safely, what does it take to actually sleep well? To have the kind of deep, restorative sleep that allows your tissues to heal, your brain to consolidate memories, and your body to maintain optimal function?

Consistency is fundamental. Your body's sleep-wake cycle (circadian rhythm) is entrained to specific timing. If you sleep at 10 PM on weekdays and midnight on weekends, your sleep quality suffers because your internal clock is confused. Going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, even on weekends, significantly improves sleep quality over time. Your body knows what to expect and optimizes its sleep processes accordingly.

Your sleep environment matters more than most people realize. Your bedroom should be cool (around 65-68 degrees Fahrenheit is optimal for most people), dark (or with minimal light that doesn't stimulate your brain's visual system), and quiet. If you can't control these factors where you live, tools like blackout curtains, earplugs, or white noise machines can help significantly. The investment is worthwhile—a poor sleep environment undermines everything else you do to improve sleep.

Lighting exposure, particularly in the hours before sleep, dramatically affects your sleep quality. Blue light from screens suppresses melatonin production, the hormone that signals your body it's time to sleep. Ideally, exposure to bright light should happen in the morning (which entrains your circadian rhythm toward waking earlier) and diminished in the evening. This means limiting screen time in the two hours before bed, or using blue light filters if you must use screens. Bright light exposure in the afternoon, combined with darkness in the evening, creates the ideal lighting pattern for good sleep.

What you consume matters significantly. Caffeine can affect sleep quality for up to 12 hours after consumption, even in modest amounts. A 3 PM coffee might still be disrupting your 11 PM sleep. Alcohol seems to help sleep initially (it's sedating) but severely disrupts sleep architecture, suppressing REM sleep and preventing the restorative stages of sleep. Regular alcohol use, especially near bedtime, is one of the most common self-inflicted causes of poor sleep.

Exercise is one of the most powerful sleep enhancers, but timing matters. Regular aerobic exercise (at least 150 minutes per week) significantly improves sleep quality and depth. However, intense exercise close to bedtime can be stimulating and counterproductive. Ideally, exercise should be completed at least 3-4 hours before sleep. The exception is gentle evening stretching or yin yoga, which can be relaxing without being stimulating.

Managing stress and anxiety is crucial. A mind racing with worries, whether about legitimate stressors or anxious rumination, prevents sleep. Techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), meditation, journaling, or simply processing worries earlier in the day can significantly improve sleep quality. Some people find it helpful to write down their worries before bed, as if transferring them from their mind to paper allows them to stop thinking about them.

Your sleep surface—your mattress and pillow—should provide proper support. A mattress that's too soft allows your spine to sag unnaturally. One that's too firm doesn't provide adequate pressure relief. Ideally, your spine should be in a neutral alignment throughout the night. Finding the right mattress is personal, but remember that a mattress that works for you is worth the investment, since you spend a third of your life on it.

Real-World Implementation: From Diagnosis to Living Well

Understanding all of this information is one thing. Actually implementing changes and living with a sleep disorder diagnosis is another. Here's how to make it practical.

If sleep apnea is diagnosed, getting started with CPAP (or an alternative therapy like Bi PAP) is critical. The first few nights might feel awkward or uncomfortable as you adjust to wearing a mask. You might find that certain mask styles work better than others. Some people do better with nasal pillows, others prefer a full-face mask. The pressure settings might need adjustment. Finding the right setup is a process, but it's worth the effort. Most modern machines are quiet, and after a week or two of use, most people stop noticing the device.

Once your sleep apnea is controlled, give yourself time to experience the benefits. The daytime sleepiness often improves first—within days to weeks. Other improvements like blood pressure reduction, mood improvement, and cognitive clarity might take weeks to months. But they do come. Track your progress in a journal. Note when you started treatment and document improvements in sleep quality, daytime energy, mood, or other symptoms. Having concrete evidence of improvement motivates continued treatment adherence.

Address other modifiable risk factors simultaneously. If weight is a factor, work on weight loss gradually through sustainable diet and exercise changes, not crash dieting. Even a 5-10% weight loss can significantly improve sleep apnea severity. You don't have to reach your ideal weight to see benefits.

Optimize your sleep environment and habits as we discussed above. These aren't fringe activities; they're fundamental to how sleep works. Every small improvement compounds.

Schedule regular follow-up appointments with your sleep specialist. Your CPAP pressure might need adjustment over time, especially if your weight changes. Your overall health status should be monitored. Untreated sleep apnea causes damage that can take years to fully reverse, so ongoing management is important.

Connect with others going through the same experience. There are online communities of people with sleep apnea who can offer practical advice about mask fit, pressure settings, and life with the condition. Knowing that others have overcome the same adjustment challenges can be motivating.

Most importantly, reframe your thinking about sleep. Sleep isn't lost time. It's not a luxury. It's health maintenance. It's when your body repairs itself from the damage of being awake. It's where long-term memory consolidation happens. It's where your immune system recovers. It's where your metabolism stays optimized. Protecting your sleep quality is protecting your entire future health. The Brooklyn patient's eyelids improve because she finally got the sleep her body desperately needed. The same principle applies to all of us.

When Simple Answers Mask Complex Causes

One final thought worth considering: the Brooklyn patient's case illustrates an important principle in medicine and in life. Sometimes what appears to be a straightforward problem has a surprising underlying cause. Her drooping eyelids weren't a eyelid problem requiring surgery. Her eye irritation wasn't primarily an eye problem requiring intense eye care. The real issue was sleep.

This teaches us to be curious. When something seems off, to ask deeper questions. Why is this symptom happening? What might be upstream of the obvious problem? What am I missing? In her case, the doctor who asked about her sleep—who connected the dots between her eyelid symptoms, her snoring, her daytime sleepiness, and her obesity—made all the difference.

It's tempting to treat symptoms directly. Droopy eyelids? Eyelid surgery. High blood pressure? Blood pressure medication. Fatigue? Stimulant medication. Sometimes that's appropriate. But sometimes the more powerful intervention is identifying and treating the root cause. And sometimes that root cause is something as fundamental as allowing your body to sleep properly.

The beautiful part about the Brooklyn patient's story is that it's a story of healing through addressing the underlying problem. Not a story of adding more medications, not a story of surgical intervention, but a story of removing an obstacle that was preventing natural healing. Her body did the hard work of recovery once it was given the chance.

FAQ

What is floppy eyelid syndrome?

Floppy eyelid syndrome is a condition where the eyelids lose structural firmness and become abnormally loose and hypermobile. In severe cases, the eyelids may droop significantly, roll inward, or even flip inside-out. The condition results from degradation of the tarsal plate, the dense connective tissue that normally maintains eyelid shape and tone.

How does floppy eyelid syndrome relate to sleep apnea?

Obstructive sleep apnea causes repeated cycles of low blood oxygen (hypoxia) followed by reoxygenation throughout the night. This creates oxidative stress in tissues, activating enzymes that break down elastin fibers in the eyelid. Over time, this elastin degradation causes eyelid laxity. Studies show that treating the sleep apnea with CPAP therapy often leads to significant improvement or resolution of FES symptoms.

What are the main symptoms of floppy eyelid syndrome?

Common symptoms include excessive tearing and watery eyes, a sensation of something foreign stuck in the eye, persistent eye redness and bloodshot appearance, difficulty fully closing the eyes, and increased irritation upon waking. These symptoms worsen when the condition prevents proper eye lubrication and protection during sleep.

Can floppy eyelid syndrome be cured?

Many cases of FES improve significantly or resolve completely once the underlying cause is treated. If sleep apnea is the culprit, CPAP therapy often brings dramatic improvement within weeks. However, if the condition has progressed to permanent tissue damage or if FES develops from other causes, surgical intervention might be necessary. Early diagnosis and treatment offer the best prognosis.

Who is most at risk for developing floppy eyelid syndrome?

Risk factors include obesity, sleep apnea, age (more common over 40), male gender, underlying connective tissue disorders, and anatomical features that predispose to airway collapse. The condition is significantly more common in people with obstructive sleep apnea, though not everyone with sleep apnea develops FES.

What is the treatment for floppy eyelid syndrome caused by sleep apnea?

The primary treatment is CPAP therapy or alternative positive airway pressure devices that maintain open airways during sleep. Supportive eye care includes lubricating drops, protective eye patches at night, and possibly eye drops to manage dryness. Weight loss management and sleep position modification (side sleeping) can help. Surgery may be considered if conservative measures don't provide adequate relief.

How many people have obstructive sleep apnea?

Roughly 1 billion adults worldwide are estimated to have obstructive sleep apnea, yet approximately 80% of moderate-to-severe cases go undiagnosed. Men are more frequently diagnosed than women, and prevalence increases with age and obesity.

What happens in your body during sleep apnea?

During obstructive sleep apnea, your airway collapses or becomes severely narrowed during sleep. Breathing stops (apnea) or becomes very shallow (hypopnea). Your brain detects the drop in blood oxygen and signals you to wake and resume breathing. This cycle repeats throughout the night, sometimes hundreds of times. Each cycle causes oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular strain.

How quickly do symptoms improve with CPAP treatment?

Many symptoms improve rapidly. Daytime sleepiness often decreases noticeably within days to weeks. Physical symptoms like drooping eyelids may improve within weeks to months. Cardiovascular changes and blood pressure improvement typically take longer, sometimes weeks to months. However, damage from untreated sleep apnea can take years to fully reverse.

Should everyone with eyelid drooping be tested for sleep apnea?

Not all eyelid drooping is caused by sleep apnea. However, if someone has eyelid drooping combined with snoring, daytime sleepiness, or morning symptoms that are worst upon waking, sleep apnea screening is appropriate. A good rule: if eyelid symptoms are accompanied by sleep-related symptoms, sleep apnea should be investigated.

Conclusion: The Simple Power of Proper Sleep

The story of the Brooklyn woman with inside-out eyelids that healed with CPAP therapy carries a profound message for modern medicine and for how we live our lives. It's a reminder that sometimes the most powerful treatments aren't the most complicated ones. Sometimes they're the most fundamental.

Sleep isn't a luxury. It's not time wasted. It's not something to squeeze in after you've checked off everything else on your to-do list. Sleep is when your body repairs itself, when your tissues heal, when your brain consolidates memories, when your immune system recovers. Your eyelids literally couldn't recover from the damage of sleep apnea until they were given the sleep they needed.

If you recognize yourself in this story—if you snore, feel tired despite seemingly adequate sleep time, have unexplained physical symptoms, or have struggled with conditions that won't resolve despite standard treatments—consider whether sleep might be the missing piece. Ask your doctor about sleep apnea. Request testing if you suspect a problem. Commit to treatment if you're diagnosed. Give your body the sleep it desperately needs.

The ripple effects will likely surprise you. Not only might your eyelids improve, but your energy will return, your clarity will sharpen, your mood will lift, and your long-term health prospects will brighten significantly. Your tissues will stop being damaged. Your heart will stop experiencing repeated stress. Your brain will finally get the restoration it's been craving.

The best part? Unlike many health interventions, sleep is something your body desperately wants to do. You don't have to force yourself to sleep well. You just have to remove the obstacles preventing it. Treat the sleep apnea. Optimize your sleep environment. Establish consistent sleep timing. Manage stress. And then let your body do what it evolved to do for millions of years: heal itself through sleep.

Your eyes, your heart, your brain, and your future self will thank you.

Key Takeaways

- Floppy eyelid syndrome often signals underlying obstructive sleep apnea, not a primary eyelid disease

- Sleep apnea causes repeated hypoxia that generates oxidative stress, breaking down elastin fibers in eyelids and tissues throughout the body

- CPAP therapy treating sleep apnea can dramatically improve eyelid drooping within weeks as tissue healing begins

- Roughly 1 billion adults have sleep apnea, with 80% remaining undiagnosed because symptoms seem unrelated to breathing

- Sleep isn't luxury—it's when your body repairs damage and maintains tissue integrity; untreated sleep disorders accelerate tissue aging

Related Articles

- How Poor Sleep Accelerates Brain Aging: Science & Prevention [2025]

- Melatonin Dosage Guide: Safe Sleep Aid Amounts [2025]

- Best Melatonin Sprays for Sleep: Complete Guide [2025]

- Best Sleep Masks for Quality Rest [2025]

- Best Organic Mattresses 2026: Complete Guide & Natural Sleep Solutions

- Best Mattresses for Back Pain: Complete Guide & Top Picks [2025]

![Floppy Eyelid Syndrome and Sleep Apnea: When Eyes Need Sleep [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/floppy-eyelid-syndrome-and-sleep-apnea-when-eyes-need-sleep-/image-1-1770318524773.jpg)