Introduction: The Battle Over Meta's Market Power Continues

It's 2025, and the antitrust fight against one of the world's largest technology companies is far from over. In November 2024, federal judge James Boasberg made a decision that caught the tech industry off guard: the FTC hadn't proven that Meta held an illegal monopoly over personal social networking services. For many observers, this felt like a knockout punch to the government's case. But here's the thing—the FTC isn't taking this loss lying down. The agency announced it would appeal Boasberg's decision, setting up what could be a years-long legal battle that will reshape how we think about tech monopolies as reported by Market Minute.

This appeal matters for reasons that go way beyond Meta. The case touches on fundamental questions about how much power companies should have, whether acquiring potential competitors is predatory, and what "the market" even means in the digital age. When you strip away the legal jargon, it's really about whether one company can buy its way to dominance according to The New York Times.

Boasberg's ruling wasn't a complete vindication for Meta either. The judge acknowledged the company's "uphill battle" defense. What he actually said was that the government defined the market too narrowly. If you include TikTok and YouTube as competitors to Meta's services, the dominance argument falls apart. That's the crux of the appeal as noted by Bloomberg.

The FTC, under the Trump-Vance administration's Bureau of Competition, argues the evidence is there. The government presented a six-week trial packed with testimony, documents, and data showing how Meta strategically acquired Instagram and WhatsApp to eliminate competition. Daniel Guarnera, the FTC's Bureau of Competition Director, said plainly: Meta didn't compete fairly—it bought its way to dominance as highlighted by The Hill.

Understanding this appeal requires diving into what the judge said, why the FTC disagrees, what the evidence actually showed, and what could happen next. This case will likely define antitrust enforcement for a decade.

TL; DR

- The Ruling: Judge Boasberg found the FTC failed to prove Meta held an illegal monopoly over personal social networking in November 2024

- The Problem: The judge said the FTC defined "the market" too narrowly by excluding TikTok and YouTube as competitors

- The Appeal: The FTC is appealing to the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, arguing the evidence clearly shows Meta's monopoly and predatory acquisitions

- The Stakes: This case will determine whether tech giants can legally acquire emerging competitors and how antitrust law applies in digital markets

- Timeline: Appeals can take 2-3 years, meaning this battle will extend well into 2027 or beyond

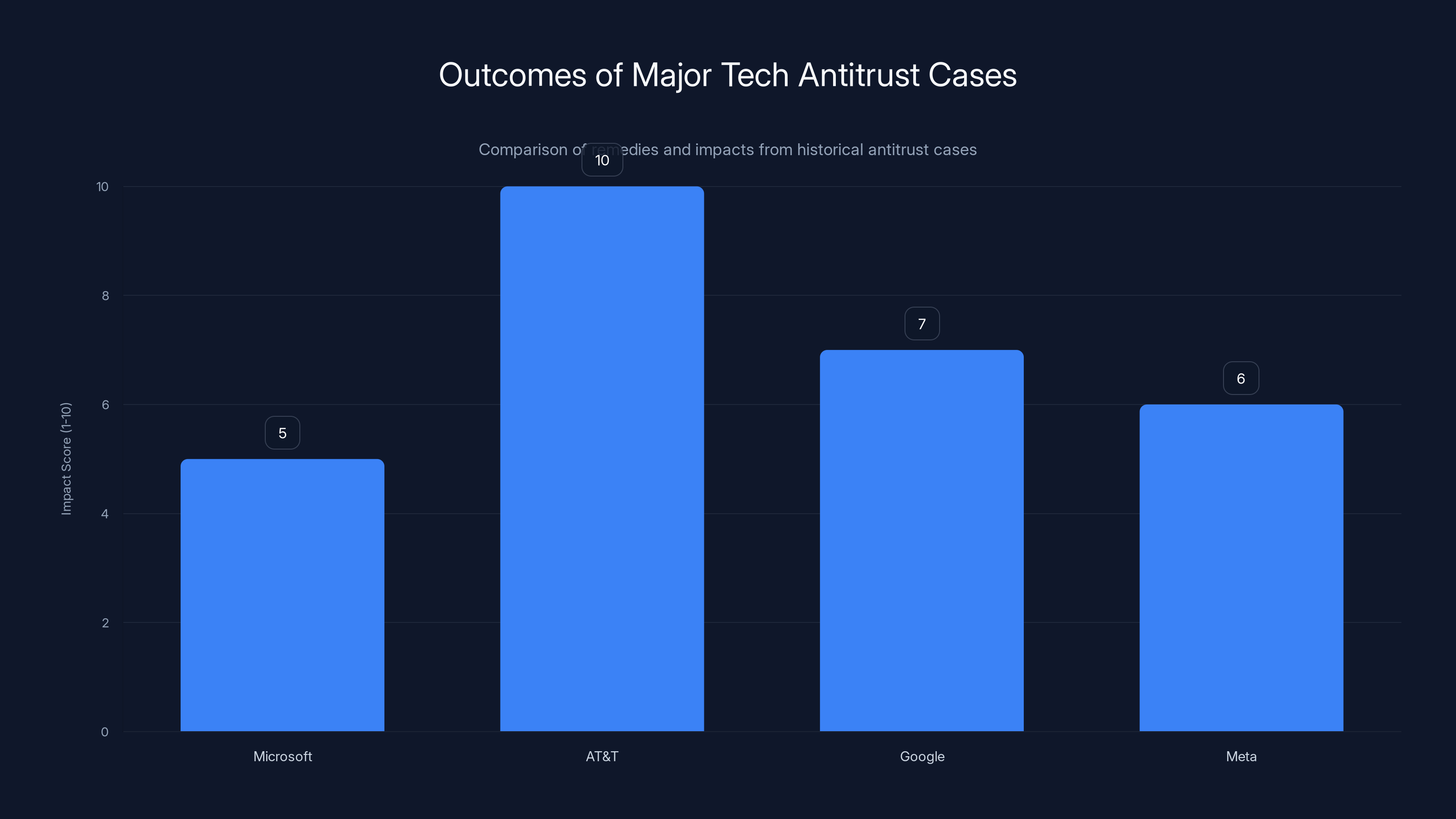

The AT&T case had the most significant impact with a breakup, while Microsoft's case resulted in modest remedies. Google's case is ongoing, and Meta's recent case had a moderate impact. (Estimated data)

What Judge Boasberg Actually Decided

Judge James Boasberg's November 2024 ruling wasn't a simple "Meta wins, government loses" decision. It was more nuanced—and that nuance matters for the appeal. Boasberg didn't say Meta is a benevolent company competing fairly. He didn't say the acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp weren't strategic. What he actually ruled was that the FTC failed to meet its burden of proof on the specific question: does Meta hold an illegal monopoly?

The judge identified the core problem with the government's case: market definition. In antitrust law, proving monopoly requires defining the relevant market first. If Meta dominates a narrow slice of the market but faces stiff competition in the broader category, there's no monopoly. The FTC argued the relevant market was "personal social networking services for connecting with friends and family." This definition excluded TikTok (which the government said is primarily entertainment and algorithm-driven discovery, not friend-based social networking) and YouTube (primarily video, not social) as discussed by AdExchanger.

Boasberg wasn't convinced. He noted that consumers increasingly use TikTok and YouTube to connect socially, even if those platforms weren't designed primarily for that purpose. Over the five-year period between when the FTC filed its case and when it went to trial, the market fundamentally changed. TikTok exploded in popularity. Instagram added Reels to compete directly with TikTok's algorithm-driven content. The market Meta operated in looked different in 2024 than it did in 2019.

The judge also noted something crucial: the FTC had an "uphill battle" because of how it framed the case. Antitrust cases are notoriously difficult to win because prosecutors must prove monopoly power within a specific, legally relevant market. If the market definition is too narrow, the case fails, even if the company behaved badly as noted by PYMNTS.

The FTC's Market Definition Strategy and Why the Judge Rejected It

The FTC's legal team walked into court with a specific strategy: define the market as "personal social networking services." Within this market, Meta dominates. Facebook has roughly 2 billion monthly active users. Instagram, owned by Meta, has over 2 billion users. WhatsApp, also Meta-owned, has nearly 2 billion users. If you're looking at services where people connect with friends and family specifically, Meta's position looks unassailable as analyzed by Jones Day.

But here's where antitrust law gets complicated. The FTC had to prove not just that Meta dominates a market, but that the market they defined is the legally relevant one. This requires showing that:

- Consumers view the products in that market as substitutes for each other

- It would be difficult for competitors to enter

- A hypothetical monopolist could raise prices without losing too many customers to products outside the market

The FTC's case relied on expert testimony and economic analysis. Their witnesses argued that TikTok and YouTube are fundamentally different from Facebook and Instagram because they prioritize algorithmic discovery over friend-based networks. A teenager might scroll TikTok for entertainment but use Instagram to message their best friend. These are different use cases, the argument went.

Boasberg listened to this reasoning and wasn't convinced it held up in 2024. He noted that TikTok users do connect socially on the platform. Young people build communities, friend networks, and social graphs on TikTok just as they do on Instagram. The platform may have started as algorithm-first, but usage patterns have evolved. Excluding TikTok from the relevant market looked increasingly arbitrary as the trial evidence accumulated as discussed by ProMarket.

This is where the appeal gets interesting. The FTC will argue that Boasberg's approach was too consumer-centric and not legally rigorous enough. Antitrust law has established methodologies for market definition. The FTC will likely argue the judge applied a standard that's too easy to satisfy and that he gave too much weight to evolving consumer behavior rather than sticking to the original purpose and design of each platform.

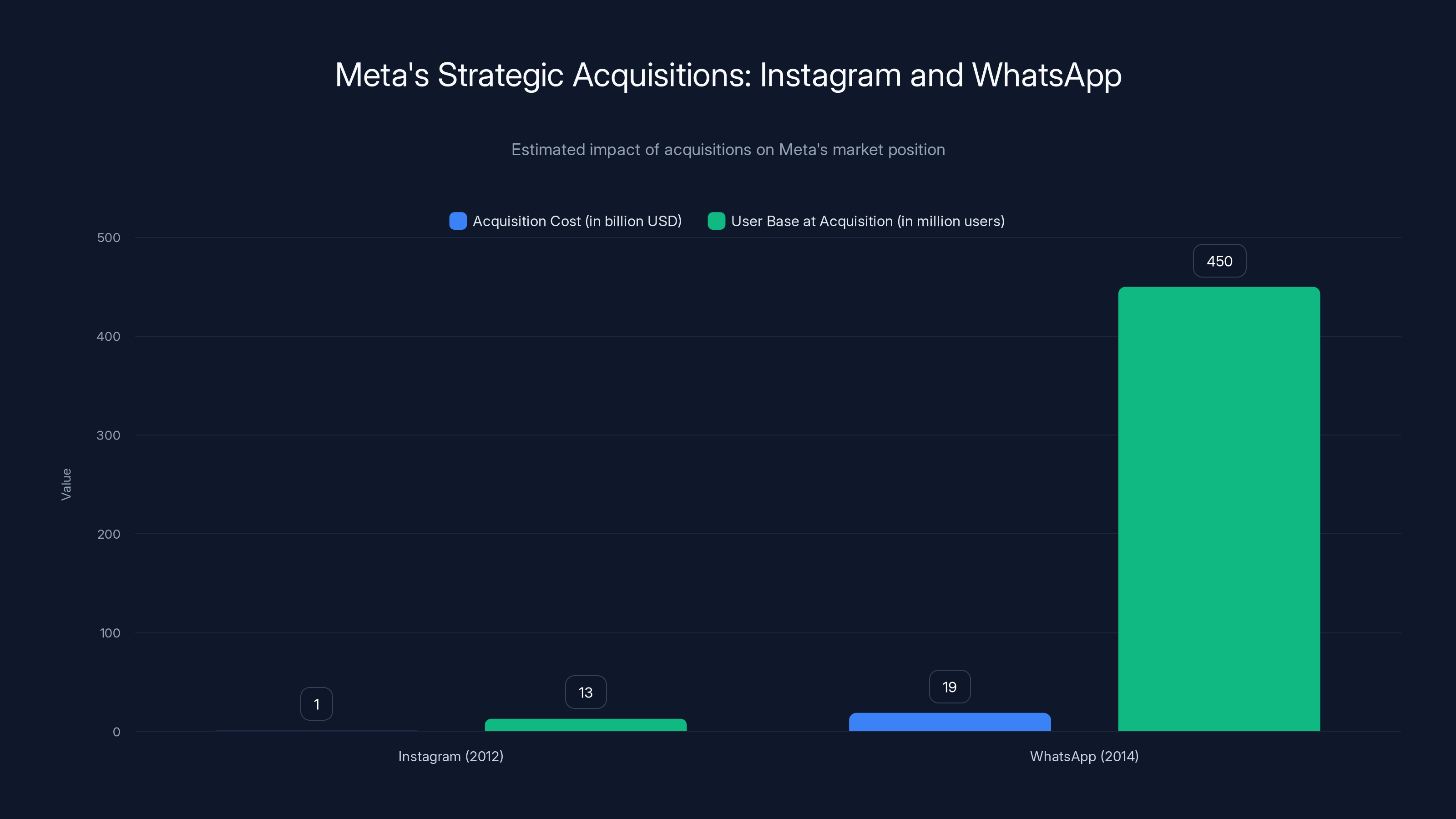

Meta's acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp were strategic moves to neutralize competition, with WhatsApp's acquisition being significantly more costly but with a larger user base. Estimated data on user base.

The Core Evidence: Instagram and WhatsApp Acquisitions

Even though Boasberg found the FTC didn't prove monopoly, the judge did acknowledge extensive evidence about Meta's acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. The government presented internal Meta documents, testimony from former executives, and analysis showing that these acquisitions were clearly strategic moves to neutralize competition as reported by Market Minute.

In 2012, Meta—then known as Facebook—purchased Instagram for $1 billion. At the time, Instagram was a small photo-sharing app with about 13 million users. But it was growing fast. By acquiring Instagram before it became a true competitor, Meta secured a dominant position in the social networking world. When Instagram eventually added messaging capabilities, then Stories, then Reels, it became increasingly similar to Facebook, just with a different user base (younger, more visual).

WhatsApp was acquired in 2014 for $19 billion. This was an enormous price at the time and signaled Meta's seriousness about controlling communication platforms. WhatsApp offered end-to-end encryption and a different value proposition—simple, reliable messaging without algorithms or ads. But it was eating into Facebook's messaging business.

The FTC's theory was straightforward: Meta saw threats and eliminated them before they could become real competitors. Rather than competing on features and quality, Meta deployed its financial power to buy nascent threats. The government showed internal Meta documents where executives discussed Instagram's competitive threat. Executives explicitly worried that if they didn't acquire Instagram, it would become a "direct threat" to Facebook as noted by PYMNTS.

Boasberg acknowledged all this evidence existed. He didn't say Meta's behavior was innocent or that these acquisitions served competition. But he said the evidence of monopoly acquisition only matters if Meta actually held a monopoly to leverage. And he found the government hadn't proven that.

This creates an interesting situation for the appeal. The FTC will argue that the facts about the acquisitions are undisputed and powerful. Meta acquired companies it perceived as threats. Meta integrated them into its ecosystem. Meta degraded the quality of its original platform by redirecting resources to protecting its dominance rather than improving user experience. These facts, the FTC will argue, support a finding of illegal monopoly leverage even if reasonable people disagree about market definition.

The TikTok Factor: How a New Competitor Changed Everything

One of the most striking elements of Boasberg's decision was how heavily he weighed TikTok's emergence. When the FTC filed its case in 2020, TikTok was already significant but not the cultural phenomenon it became by 2024. During the five years between filing and trial, TikTok's user base exploded. The app went from roughly 500 million users globally to over 1 billion as reported by The Verge.

For Boasberg, this wasn't just a statistical change—it was evidence that the market wasn't as locked down as the FTC claimed. If Meta truly held an illegal monopoly, the theory goes, it should be able to prevent new competitors from entering and gaining dominance. But TikTok entered anyway and achieved massive scale without acquiring Instagram or WhatsApp. This suggested to the judge that Meta's position, while dominant in absolute terms, wasn't protected by barriers to entry that would characterize a true monopoly.

The FTC will likely argue this reasoning misunderstands antitrust law. In response to the appeal, government lawyers will probably say: TikTok's success doesn't erase Meta's past monopolistic behavior. When Meta acquired Instagram, the market conditions were different. TikTok didn't exist as a meaningful player. You can't use the presence of a competitor that emerged after the illegal conduct occurred as evidence the conduct wasn't monopolistic.

This is a genuinely hard legal question. Antitrust law typically looks at markets as they existed when the conduct occurred, not how they look years later. But it's also true that market conditions change, and past monopoly power doesn't guarantee future dominance. The DC Circuit Court of Appeals will have to decide whether a "dead hand" monopoly—one that existed in the past but faces new competition now—can still be the basis for antitrust liability.

What's particularly interesting is that neither side has a perfect answer. The FTC's framework (ignore TikTok, focus on what the market looked like when Instagram was acquired) feels anachronistic when applied to fast-moving tech markets. But Meta's framework (look at current market conditions to evaluate whether past conduct was actually monopolistic) feels like it lets companies off the hook for bad behavior just because disruption eventually happened.

The Current Antitrust Landscape Under Trump-Vance

One thing that adds urgency to the FTC's appeal decision is the political moment. The FTC filing the Meta case and pursuing it aggressively happened under the Biden administration. When the ruling came down in November 2024, it felt like a setback for government enforcement. But the Trump administration, which took office in January 2025, has shown its own appetite for antitrust enforcement—just with different targets and priorities as noted by First Online.

Daniel Guarnera, the FTC Bureau of Competition Director quoted in the appeal announcement, is part of the Trump-Vance team. The statement emphasizing that "The Trump-Vance FTC will continue fighting" signals that antitrust enforcement against Meta remains a priority even across the political transition. This is somewhat surprising given that tech company executives have historically had more sympathetic relationships with Republican administrations.

But antitrust has become one of the few areas where there's genuine bipartisan concern about Big Tech. Democratic critics worry about monopoly power and platform power over speech. Republican critics worry about censorship and anti-conservative bias. Both parties see antitrust enforcement as a tool for addressing tech company dominance, even if their underlying concerns differ.

The Trump administration's framing in the appeal announcement emphasizes economic competition and U.S. businesses' ability to compete fairly. This is standard antitrust rhetoric—it's about making sure the economy works for everyone, not just tech billionaires. Whether this translates to vigorous appellate advocacy and success at the DC Circuit is an open question.

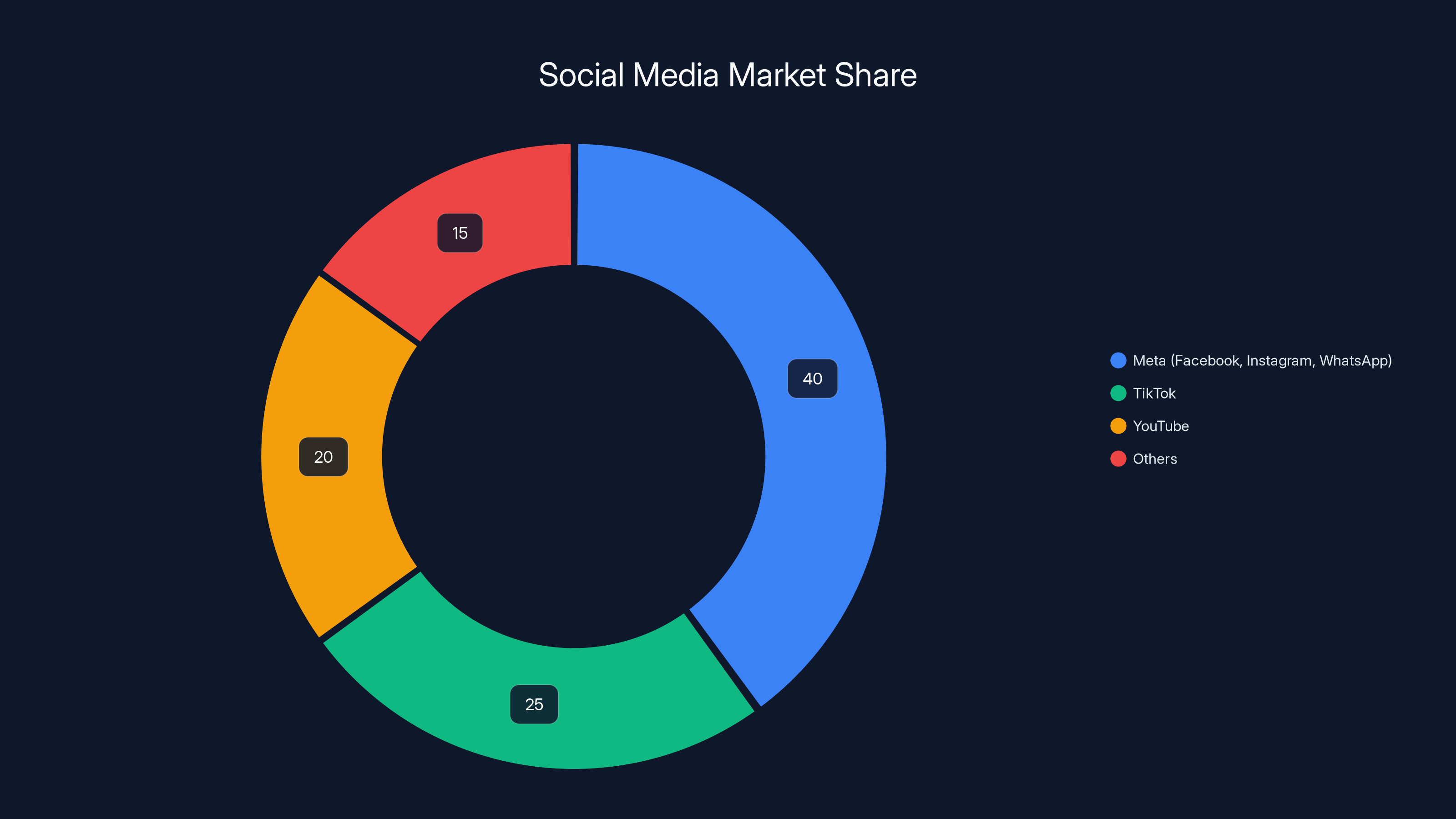

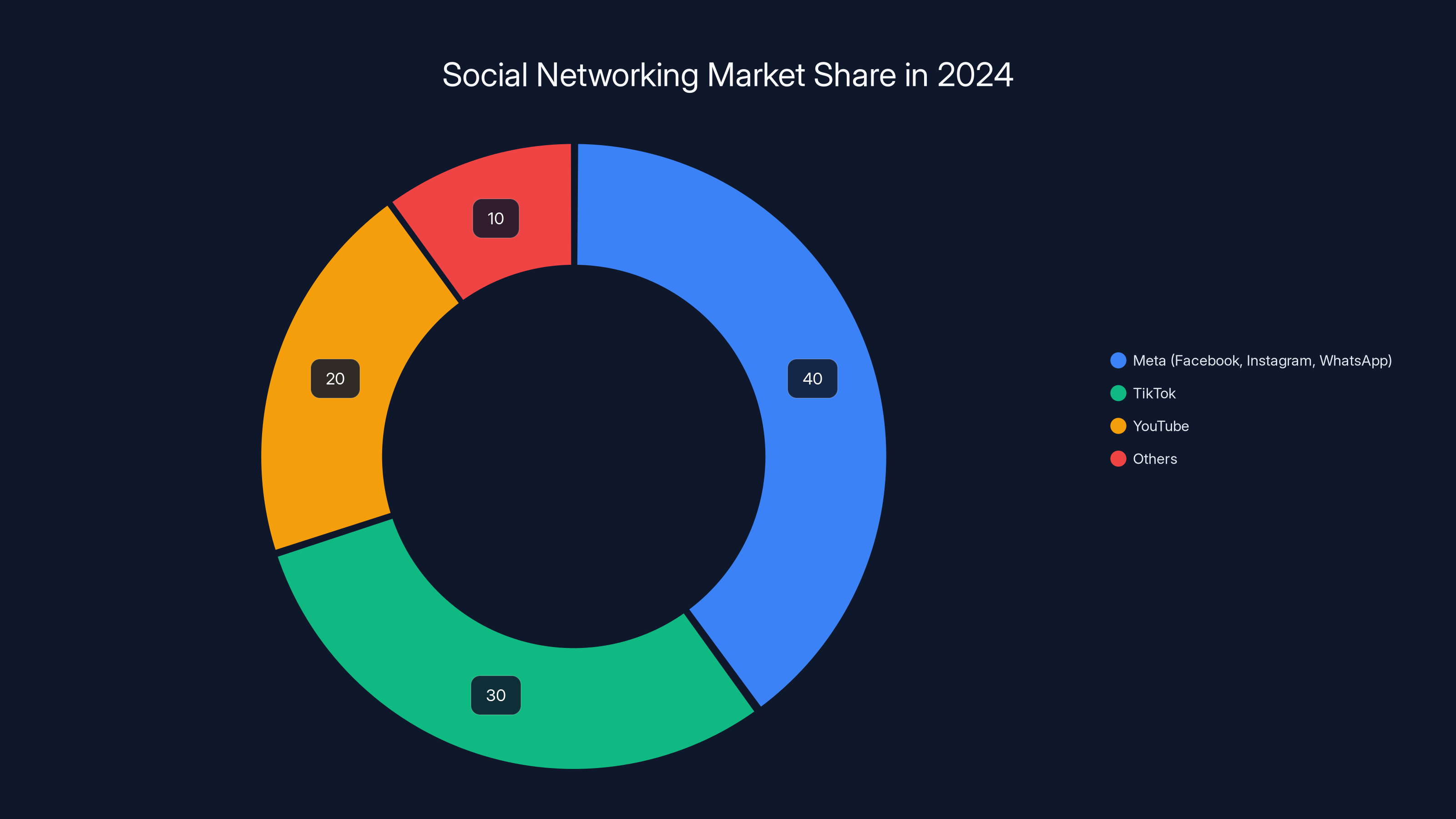

Estimated data shows Meta holding a significant portion of the social media market, but competition from TikTok and YouTube suggests a more competitive landscape than a monopoly.

How the DC Circuit Court of Appeals Will Review the Decision

The next phase of this battle takes place at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. This is one of the most prestigious appellate courts in the country, and it handles many major antitrust cases. The DC Circuit doesn't retry the case with new evidence. Instead, it reviews whether the trial judge applied the law correctly to the facts presented.

The standard of review matters enormously. For factual findings (did the FTC present evidence of X behavior?), the appellate court uses a "clear error" standard. This is deferential to the trial judge. The appellate court will only overturn factual findings if they're clearly erroneous. For legal conclusions (does proving X behavior constitute an illegal monopoly under antitrust law?), the court uses a "de novo" standard—meaning it gives no deference and decides the law question independently.

The FTC's best shot on appeal likely involves legal arguments rather than challenging factual findings. The government won't try to convince the DC Circuit that Boasberg was clearly wrong about the market definition. Instead, they'll argue about what the correct legal standard is for market definition and whether, even under alternative market definitions, the evidence supported liability.

One specific argument the FTC might pursue: even if you include TikTok and YouTube in the relevant market, Meta still holds dominance within "personal social networking" narrowly defined. Maybe the legally relevant market is broader than the FTC originally argued, but it's still a market where Meta exercises monopoly power. The acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp can be challenged as predatory even under a broader market definition.

Another legal argument: antitrust law shouldn't penalize a company for past conduct just because the market later became more competitive. The DC Circuit could establish a principle that antitrust liability depends on market conditions when the conduct occurred, not market conditions years later when the case goes to trial.

Meta's defense at the appellate level will focus on exactly what convinced Boasberg: market definition. Meta will argue that in the modern social networking landscape, consumers have unprecedented choice. They can use Facebook to keep up with distant friends, Instagram for visual updates, TikTok for algorithmic discovery, YouTube for longer-form content, Snapchat for ephemeral sharing, BeReal for authentic moments, Discord for communities, and many other platforms. Claiming Meta has monopoly power in this landscape requires an unreasonably narrow market definition.

The DC Circuit's decision could come in 2026 or 2027. Appeals in major cases like this typically take 18-24 months.

What the Evidence Actually Showed: A Closer Look

During the six-week trial, the FTC presented extensive evidence about Meta's market dominance and strategic acquisitions. Understanding what evidence was presented helps contextualize why the FTC believes it should win on appeal and why Boasberg wasn't persuaded.

The government presented data showing Meta's user base, engagement metrics, and advertising dominance. Facebook and Instagram combined represent a massive portion of social media time and advertising spending. The FTC argued this dominance would be unattainable in a competitive market—evidence of monopoly power.

But Meta countered with evidence of vigorous competition. The company presented user behavior data showing that people use multiple platforms. Teens use TikTok more than Instagram now. YouTube dominates video consumption. Snapchat still has significant user engagement. From Meta's perspective, the evidence showed competition, not monopoly.

The trial also included testimony from economists and industry experts on both sides. The FTC's expert witnesses testified about barriers to entry in social networking—the importance of network effects, the difficulty of building a user base, and the advantages of incumbency. The more people on Facebook, the more valuable it becomes to each user (network effects). A new competitor would need to overcome this to gain traction.

Meta's experts countered that network effects in social networking are weaker than commonly assumed. They presented data showing that users regularly switch between multiple social networks and that new platforms can achieve scale quickly if they offer something novel. TikTok proved this point dramatically by going from nothing to global dominance in just a few years.

The trial included internal Meta documents that were quite damaging from the government's perspective. Email and message threads showed executives viewing Instagram and WhatsApp as competitive threats. One famous quote involved Facebook executives discussing whether to "squash" Instagram's threat. These documents supported the FTC's theory that Meta acquired competitors to eliminate threats rather than for complementary services.

But even with this evidence, Boasberg found it insufficient to prove monopoly in the relevant market. The problem wasn't the evidence about the acquisitions—it was that the market definition required to hang the monopoly charge on was too contested.

Service Quality Degradation: The Neglected Argument

One interesting element of the FTC's case that deserves more attention is the allegation that Meta degraded the quality of Facebook after acquiring Instagram. The theory goes like this: if Meta truly faced competition and needed to keep Facebook competitive, it would have continued improving the product. Instead, Meta shifted engineering resources to Instagram (the trendier, younger platform) and allowed Facebook's interface to become cluttered with recommendation feeds, advertisements, and sponsored content.

Facebook users increasingly complain that the service is difficult to use, filled with content they don't want to see, and algorithmically optimized for engagement rather than meaningful connection. This, the FTC argued, is evidence of monopoly power—the ability to degrade service because users have no good alternatives.

Boasberg acknowledged this argument but noted that it's hard to quantify and that different users might have different preferences. Some users like algorithm-driven recommendations. Some don't. Proving that quality degradation was monopolistic rather than just bad design choices is difficult.

On appeal, the FTC might emphasize this argument more. The government could argue that combined evidence of dominance, strategic acquisitions, and service degradation creates a picture of monopoly. Even if any single piece of evidence isn't conclusive, the totality supports antitrust liability.

Meta's response would be that interface choices and feature prioritization are business decisions protected by antitrust law. Companies are allowed to make products worse if they want to. There's no duty to maximize service quality. As long as users can leave, the law doesn't intervene in product design.

Meta holds a significant portion of the social networking market, but TikTok and YouTube also have substantial shares, challenging the monopoly narrative. Estimated data based on market trends.

Previous Tech Antitrust Cases and How They Inform This Appeal

The Meta case doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's part of a longer history of antitrust cases against technology companies. Understanding how previous cases were decided provides context for what might happen in the DC Circuit.

The Microsoft case in the 1990s and early 2000s is the most famous comparison. Microsoft was accused of illegally maintaining monopoly in operating systems by bundling Internet Explorer with Windows. The case hinged on market definition—was Windows the relevant market or was the market broader? The government argued narrow market definition. Microsoft argued consumers could easily switch to alternative operating systems.

The court found that Microsoft did maintain monopoly power in operating systems and did engage in predatory conduct. But the ultimate remedy was modest because appeals and political pressure whittled down the case. Microsoft was never broken up. Antitrust observers often point to Microsoft as evidence that even when the government wins, the remedy might not be what was sought.

The AT&T breakup in 1982 was the most significant antitrust remedy in history. The government proved that AT&T held monopoly power in telecommunications and that the monopoly was structural. The company was broken into regional operating companies and divested. But this case took a decade to litigate and involved negotiations and political pressure.

More recently, the antitrust case against Google (filed during the Trump administration and continued under Biden) focuses on search and advertising markets. Google is accused of unlawfully maintaining monopoly power through exclusionary contracts and predatory practices. This case is currently in discovery and trial hasn't begun. The outcome will likely inform how courts view Meta's appeal.

The FTC's second case against Meta—filed in 2020 and resolved in 2021—actually sought to divest Instagram and WhatsApp from Facebook. The FTC argued these acquisitions were unlawful and should be undone. But Boasberg, the same judge, rejected this claim in May 2021, finding the acquisitions lawful at the time they occurred (even though they might have been problematic in hindsight). This prior ruling complicates the current appeal because the same judge has already decided related questions about Meta's acquisitions.

The Economic Theory Behind Antitrust Claims Against Meta

To understand why the FTC believes it should win on appeal, it's important to understand the economic theory underlying the case. Modern antitrust relies on several key economic concepts.

Network effects are one key concept. In social networking, more users make the platform more valuable. If everyone you know is on Facebook, Facebook is valuable to you. If they leave for a new platform, that new platform becomes valuable. Network effects can create powerful lock-in effects that limit competition.

However, tech economists debate how strong network effects actually are in social networking. People regularly use multiple social networks. Network effects haven't prevented new platforms from emerging. Snapchat grew despite Facebook's dominance. TikTok exploded despite Meta's dominance. This suggests network effects, while real, aren't insurmountable barriers.

Barriers to entry are another concept. How hard is it to start a new social network that can compete with Facebook? The FTC argued it's very hard because of network effects, data advantages, and switching costs. The defense argued it's gotten easier over time and that TikTok's success proves it.

Predatory acquisition is the specific behavior the FTC is attacking. The theory is that Meta acquired Instagram and WhatsApp not to gain complementary assets or consolidate platforms, but specifically to neutralize competitive threats. This type of acquisition can be illegal if the acquiring company has monopoly power and uses it to strengthen its monopoly.

But this is where market definition becomes critical. If Meta doesn't have a relevant monopoly to defend, then the acquisitions can't be predatory acquisitions in an antitrust sense. They'd just be normal acquisitions by a large company.

The FTC's economic expert witnesses presumably argued that the narrowly-defined "personal social networking" market is the legally relevant one because that's where direct, head-to-head competition occurs. You compete for personal social networking either with Facebook or Instagram (both Meta). You don't compete with TikTok in the same way because TikTok's primary value proposition is algorithmic discovery, not personal networks.

Meta's economic expert witnesses presumably countered that consumers don't limit their competition analysis to narrow subcategories. They consider their total time and attention budget. You can spend an hour on TikTok or Instagram. It's a tradeoff. Therefore, TikTok is a competitor in the broader social media market that includes all platforms competing for user time and attention.

On appeal, these economic arguments will be litigated again. The DC Circuit will have to decide which economic theory better reflects reality and which market definition is legally appropriate. This isn't a question with an objectively right answer—it depends on economic judgment and legal policy.

Remedies and What Victory Would Mean for Meta

If the FTC wins on appeal, what happens next? This is important because it affects the stakes of the case and whether settling might make sense for either party.

The FTC originally sought divestiture of Instagram and WhatsApp from Meta in a separate 2020 case. That remedy failed at trial when Boasberg ruled the acquisitions were lawful. But if the current appeal succeeds and establishes that Meta maintained monopoly through these acquisitions, the FTC could seek divestiture again in a follow-up proceeding.

Divestiture is the nuclear option in antitrust remedies. It means Meta would be forced to sell Instagram and WhatsApp to other companies. This would be enormously disruptive and valuable for potential buyers. Instagram, which Meta acquired for

Shorter of divestiture, the FTC could seek structural or behavioral remedies. Structural remedies involve breaking up the company or preventing certain acquisitions. Behavioral remedies involve rules about how the company operates. For example, the court could order Meta to maintain separate systems for Instagram and Facebook to prevent anti-competitive integration. Or the court could prevent Meta from acquiring new companies without government approval for a period of years.

For Meta, losing on appeal and facing potential divestiture or ongoing restrictions would be catastrophic. The company's value partly depends on owning multiple social platforms. Losing Instagram or WhatsApp would fundamentally change Meta's business model.

This is why settlement could appeal to both sides. Meta might be willing to accept significant behavioral restrictions or even partial divestitures to avoid full divestiture of Instagram. The FTC might be willing to accept restrictions that prevent future acquisitions and require competition-promoting changes to achieve meaningful relief.

But as of now, both sides seem committed to litigating. Meta is confident enough in Boasberg's reasoning to defend on appeal. The FTC is confident enough in its evidence to appeal rather than negotiate.

Meta's platforms (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) collectively dominate with 6 billion users, but TikTok and YouTube also hold significant shares. Estimated data.

Timeline and Procedural Next Steps

The appeal will follow a structured process that typically takes 18-24 months. Here's what comes next:

First, the FTC will file a brief at the DC Circuit Court of Appeals within a few months of the notice of appeal. This brief will present the FTC's legal arguments for why Boasberg was wrong. The brief will reference the record from trial and explain how the law should apply to the facts proven.

Meta will file a responsive brief defending Boasberg's decision. Meta will argue either that Boasberg was correct as a matter of law or that his discretionary judgment deserves deference.

Both sides may file reply briefs to address specific points raised by the other side.

After the briefing is complete, the DC Circuit will schedule oral arguments. This is where the lawyers for both sides present their arguments to a panel of judges and answer questions. Oral arguments in major cases typically last 30-60 minutes total (divided among the parties).

After oral arguments, the judges take the case under advisement. The panel deliberates and eventually issues a decision. For major cases, there might be a majority opinion, concurring opinions, and dissenting opinions. The decision gets published and becomes binding precedent.

If the FTC loses at the DC Circuit, it could seek review at the U.S. Supreme Court by filing a petition for certiorari. But the Supreme Court takes only about 50-75 cases per year out of thousands of petitions. It's unlikely (though not impossible) that the Court would hear a tech antitrust case unless there's a circuit split or the issue is of exceptional importance.

If the FTC wins at the DC Circuit, Meta could petition for certiorari, or the case could go back to trial for remedies to be determined.

The entire process—including potential Supreme Court review—could easily extend to 2027 or beyond. This is why the tech industry is watching this case so closely. The outcome could take years to become final, but when it does, it will affect how tech companies operate.

Industry Implications: What This Appeal Means for Big Tech

The Meta appeal isn't just about Meta. The outcome will signal how aggressive antitrust enforcement will be against tech giants and how courts will treat market definition disputes.

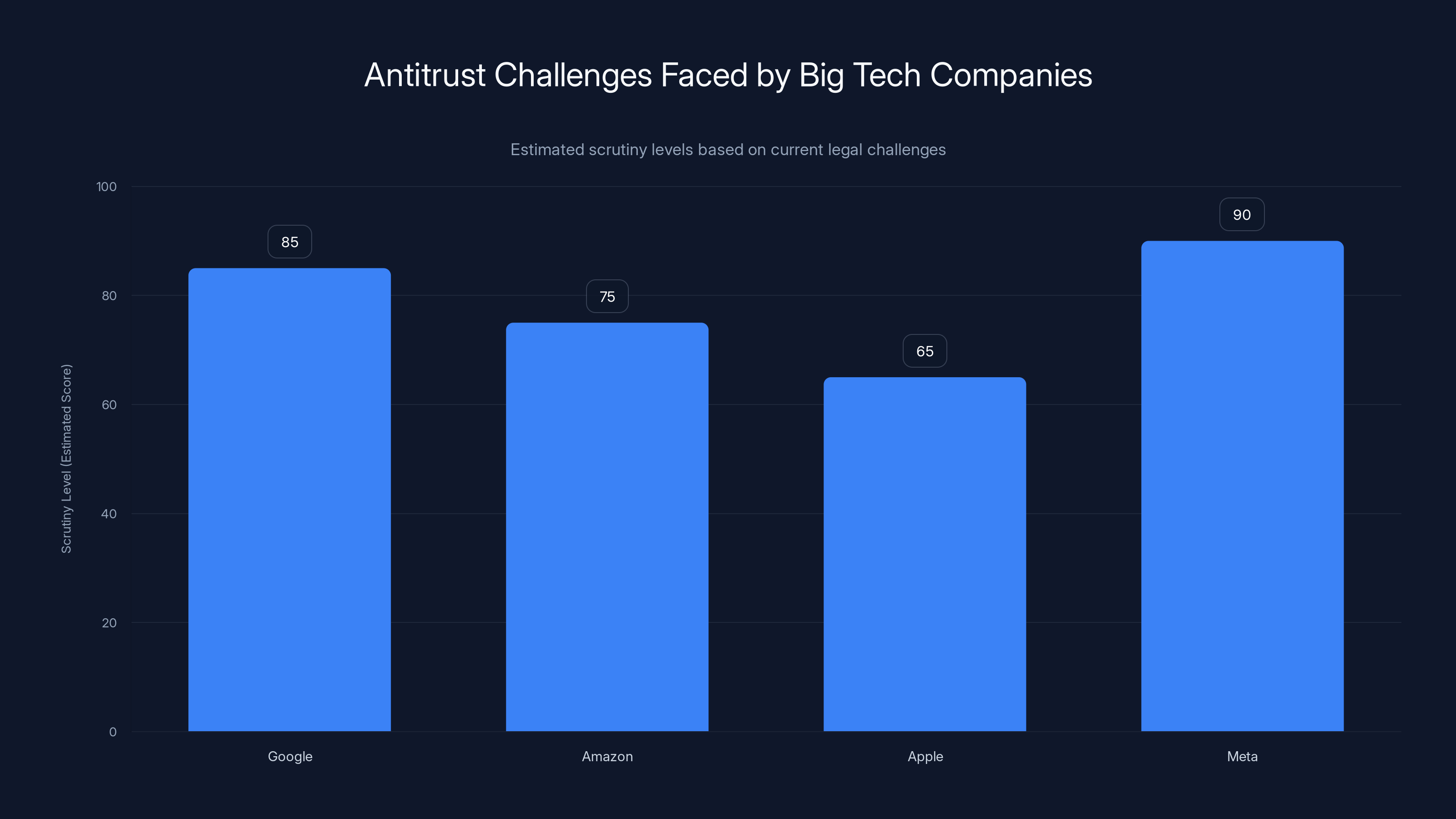

If the FTC wins, other tech companies will face increased scrutiny of their acquisitions. Google is already facing antitrust litigation. Amazon faces multiple antitrust challenges. Apple is under investigation. A win in the Meta appeal would embolden regulators and provide legal precedent for attacking other tech company dominance.

If Meta wins on appeal (or if the FTC's appeal is rejected), it signals that antitrust law is a difficult tool for challenging tech monopolies. Companies can acquire competitors without fear of liability as long as they can credibly argue the market is broader than prosecutors claim. This would be bad news for the FTC's broader agenda of tech regulation.

Beyond the merits, the appeal reflects a broader debate about antitrust in the digital age. Antitrust law was written for industrial companies and manufacturing. Applying it to tech platforms is genuinely hard because tech markets are different. They're global, they change rapidly, and they often have free consumer products funded by advertising or data monetization. Traditional antitrust assumes homogenous products and prices. Digital markets don't fit neatly into these categories.

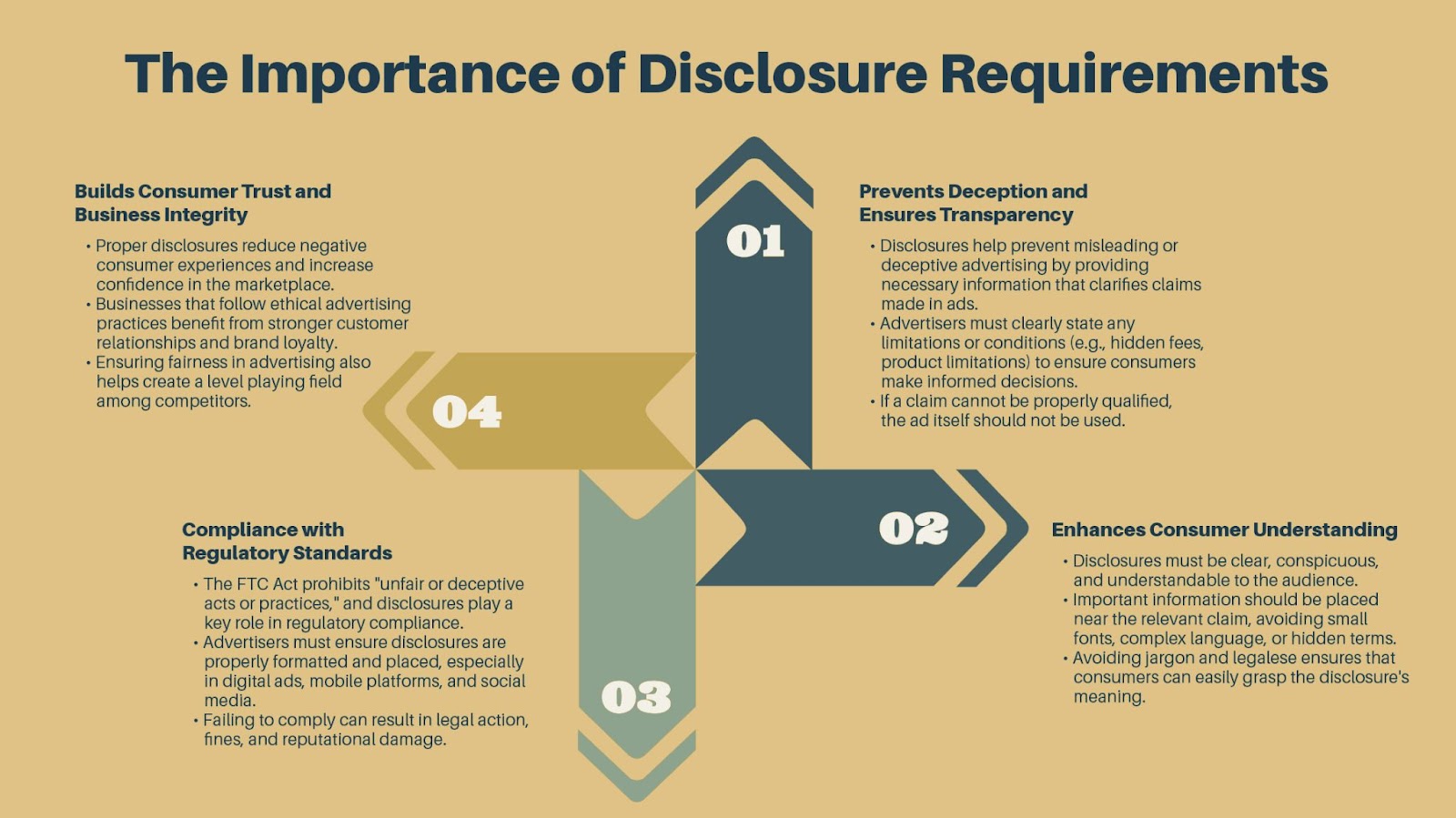

The FTC is essentially arguing that antitrust law needs to evolve to address platform power. Market definition should focus on functional competition, not narrow product categories. Antitrust should be concerned with the power to degrade service quality and exclude competitors, not just the power to raise prices.

Meta is arguing that antitrust law should stick to traditional approaches. If a market is broadly competitive (which social media is), a company can't be a monopolist just because it's dominant in a narrow subcategory. Antitrust should be about prices and consumer harm, not about corporate structure or the number of platforms a company owns.

These are genuinely important debates about how the law should work. They're not technical nitpicks—they're about the fundamental purpose of antitrust law in a digital economy.

Why Market Definition Is So Contentious

Market definition seems like a technical legal issue, but it's actually the central battleground in antitrust disputes. Understanding why it's so contentious helps explain why reasonable people disagree about whether Meta has monopoly power.

Market definition involves several steps. First, you identify the relevant product. For Meta, the FTC said personal social networking. But what counts as personal social networking? If Facebook is, then why not Instagram? Why not TikTok? Why not YouTube? Each answer leads to a different relevant market.

Second, you identify the geographic market. For Meta, the relevant market is probably global or at least North American. But maybe it should be defined by country or region? Each definition affects whether Meta looks dominant.

Third, you define the time period. Should you look at when the acquisitions occurred or when the case is being decided? If you look at 2012 when Instagram was acquired, Meta's dominance looked different than in 2024 with TikTok's presence.

Finally, you decide whether to use a narrow or broad definition. Narrow definitions focus on direct competition. Broad definitions focus on overall competition for consumer time and attention. The FTC chose narrow. Meta would choose broad.

There's no objectively correct way to define a market. It's a judgment call. Reasonable people disagree. This is why smart economists can look at the same facts and reach opposite conclusions.

On appeal, the DC Circuit will have to decide whether Boasberg's market definition was reasonable or whether it was too broad. This is a genuinely hard question without a right answer.

Estimated data shows that Meta and Google face the highest antitrust scrutiny, with Meta's appeal potentially setting a precedent for future cases.

The Evidence That Could Shift This Appeal

While the trial record is closed, new information could influence how the DC Circuit views the case. If data or facts emerge showing Meta's market dominance was greater than trial evidence suggested, or if TikTok's competitive threat was overstated, that could affect the appeal.

The TikTok situation is particularly fluid. In early 2025, there was discussion of TikTok potentially facing restrictions or bans in the United States due to national security concerns. If TikTok is restricted or banned, it would undercut Meta's argument that TikTok represents a viable competitor. If TikTok is restricted, the FTC could file a supplemental brief arguing that current market conditions prove the FTC was right that Meta faces no real competition from TikTok and therefore does hold a relevant monopoly.

Alternatively, if TikTok continues growing and thriving, that would support Meta's appeal arguments that the relevant market is competitive.

New Meta internal documents could also emerge. If whistleblowers provide additional evidence of executives viewing competitors as threats, or if documents show Meta had a specific strategy to degrade Facebook while promoting Instagram, that could help the FTC's appeal.

Economic research on network effects and market definition could influence the appeal. If new studies show that network effects are stronger in social networking than previously thought, that would help the FTC's case. If studies show network effects are weaker, that would help Meta.

Changes in consumer behavior could matter. If users increasingly switch between multiple platforms and reduce time on Facebook specifically, that would undercut the FTC's theory that Meta faces no competition. If the opposite happens, it would support the FTC.

None of these factors alone would be determinative, but collectively they could influence how the DC Circuit views the case.

Settlement Possibilities and Negotiation Dynamics

Although both sides have filed for appeal rather than settling, negotiation could still happen before oral arguments or even during the appellate process. High-stakes cases sometimes settle in unexpected ways as the parties adjust their expectations based on briefs and legal developments.

For Meta, settling might make sense if the FTC offers a deal that avoids divestiture or long-term restrictions on acquisitions. The company could agree to conduct oversight, structural separation of platforms, or restrictions on future acquisitions in exchange for avoiding the risk of losing the entire appeal.

For the FTC, settling might make sense if Meta offers to change its practices in ways that promote competition. For example, Meta could agree to allow users to port their social networks to other platforms, could open up its APIs to competitors, or could maintain separate systems for Instagram and Facebook to prevent anti-competitive integration.

Settlement talks, if they happen, would likely be confidential. They might occur behind the scenes as the appeal processes. Both sides have incentives to resolve this: Meta avoids the risk of divestiture, and the FTC avoids the risk of losing on appeal and establishing precedent that makes future enforcement harder.

But as of now, both sides seem committed to fighting. This suggests they're confident in their legal positions and willing to bet on appellate review.

International Antitrust Dimensions

Meta faces antitrust challenges not just in the United States but also internationally. The European Union, United Kingdom, and other jurisdictions have their own antitrust laws and enforcement actions against Meta.

The EU's Digital Markets Act (DMA) specifically targets large digital platforms like Meta and imposes obligations to ensure interoperability, data portability, and fair competition. This is a different legal framework than U.S. antitrust, but it addresses similar concerns about platform power.

The EU has also fined Meta billions for data protection violations, which sometimes overlap with antitrust concerns. The overall picture is that antitrust and regulatory pressure against Meta is global, not just U.S.-specific.

For the DC Circuit, international developments might not directly affect the appeal, but they could influence political and market context. If Meta faces significant restrictions in Europe, that could make a U.S. antitrust loss or settlement more likely.

Conversely, if the U.S. wins against Meta, that could embolden other countries to pursue their own enforcement actions. An FTC victory could create momentum for global antitrust enforcement against tech platforms.

The Broader Antitrust Philosophy: Conservative vs. Progressive

The Meta appeal involves competing philosophies about what antitrust law should do. Understanding these philosophies helps explain why equally intelligent people disagree about whether Meta's conduct was illegal.

The conservative antitrust philosophy emphasizes that antitrust law should focus on prices and consumer welfare. If consumers aren't harmed (for example, if Facebook and Instagram are free and consumers prefer them to alternatives), then there's no antitrust violation even if the company is dominant. This view comes from the Chicago School of economics and has dominated antitrust thinking since the 1980s.

The progressive antitrust philosophy emphasizes that antitrust law should also consider broader questions about power, fairness, and competition process. Even if consumers aren't directly harmed by prices, harm can occur through degraded service quality, limited choice, or exclusion of competitors. This view has become more prominent in recent years, particularly among younger antitrust scholars and enforcers.

Boasberg's decision reflects elements of conservative antitrust thinking. He focused on consumer welfare and whether consumers actually lack alternatives. The FTC's theory reflects progressive antitrust thinking. The agency is concerned about Meta's power even if prices are low because competition has been artificially reduced.

The DC Circuit will have to decide which philosophy should prevail or whether antitrust law should accommodate both. This is ultimately a choice about values, not just legal interpretation. It's about what kind of economy we want—one where companies can be large and dominant if they don't harm prices, or one where regulators can break up or restrict dominance to preserve competition process.

Conclusion: The Stakes and Timeline Ahead

The FTC's decision to appeal Judge Boasberg's Meta antitrust ruling signals that the fight over Big Tech dominance is far from over. While the trial judgment felt like a setback for government enforcement, the appeal will give the FTC another shot to convince appellate judges that Meta's market power and strategic acquisitions constitute illegal monopoly behavior.

The core issue on appeal is market definition. Did the FTC properly define the relevant market as personal social networking for friends and family, or did Boasberg correctly reject this definition as too narrow in a world where TikTok and YouTube compete for the same user attention? This seemingly technical question will determine the case's outcome.

The evidence about Meta's acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp is undisputed and damaging to Meta. The only question is whether dominance in a relevant market provides the legal foundation to call these acquisitions predatory. If the DC Circuit agrees with the FTC's market definition, Meta loses. If the court agrees with Boasberg that the market is broader and more competitive, Meta wins.

The timeline suggests we won't have a final answer until 2026 or 2027 at the earliest. The appeal could extend even longer if the Supreme Court grants review. During this time, Meta faces regulatory uncertainty but isn't in immediate danger of losing Instagram or WhatsApp.

For the broader tech industry, this appeal will be enormously influential. A win for the FTC would embolden regulators and provide legal tools for challenging other tech company dominance. A win for Meta would suggest that antitrust law, as currently interpreted, provides limited tools for challenging platform monopolies.

Ultimately, what happens in the DC Circuit will affect how tech companies operate, whether they can acquire competitors, and what obligations they have to competitors and users. It will shape antitrust enforcement for years to come and potentially determine whether Big Tech consolidation continues unchecked or faces serious legal constraints.

The FTC's appeal is a bet that appellate judges will see Meta's dominance and strategic acquisitions as conduct that antitrust law should prohibit, even if Boasberg wasn't convinced. Whether that bet pays off will take years to determine.

FAQ

What is the FTC's antitrust case against Meta about?

The FTC filed a lawsuit arguing that Meta illegally maintained monopoly power in personal social networking by acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp before they could become significant competitors. The government's theory is that rather than competing on service quality, Meta used its financial dominance to eliminate emerging threats through acquisition.

Why did Judge Boasberg rule against the FTC?

Judge Boasberg found that the FTC failed to prove Meta held a relevant market monopoly. He concluded the FTC's definition of the market as "personal social networking for connecting with friends and family" was too narrow because TikTok and YouTube also function as platforms where people connect socially, even though they weren't originally designed primarily for that purpose. Without proving monopoly in a legally relevant market, the acquisitions couldn't be found illegal.

What is market definition and why does it matter in antitrust cases?

Market definition is the process of identifying which products or services compete with each other. It matters because antitrust law requires proving a company has monopoly power within a defined market. If the market is defined narrowly (personal social networking only), Meta looks dominant. If defined broadly (all social media platforms), competition appears robust. The same company can look like a monopolist or a normal competitor depending on how the market is defined.

What evidence did the FTC present at trial?

The FTC presented internal Meta documents showing executives viewed Instagram and WhatsApp as competitive threats, data about Meta's dominance in user base and engagement, expert testimony about network effects and barriers to entry, and analysis of how Meta integrated Instagram and WhatsApp into its ecosystem. The government also presented evidence that Meta degraded Facebook's service quality after acquiring Instagram, allocating resources to the newer platform.

How long will the appeal take?

Antitrust appeals at the DC Circuit typically take 18-24 months from filing the initial brief to oral arguments and decisions. The FTC filed its notice of appeal in late 2024, so a decision is likely in 2026 or 2027. If either party appeals to the Supreme Court, the process would extend another 1-2 years.

What could happen if the FTC wins on appeal?

If the FTC wins, the case would return to trial for determining remedies. The FTC's original request was divestiture of Instagram and WhatsApp, which would force Meta to sell these platforms to other companies. Alternatively, the court could impose behavioral remedies like preventing Meta from acquiring new companies, requiring data portability, or mandating separation between Instagram and Facebook systems. The scope of potential remedies depends on what the appellate court rules.

Could the FTC and Meta settle the appeal?

Settlement is possible at any point in the appellate process, though both sides have committed to litigation rather than negotiation so far. Meta might prefer settling to avoid the risk of losing the appeal and facing divestiture. The FTC might prefer settling to get guaranteed changes to Meta's business practices rather than risk the appeal being rejected. Any settlement would likely be confidential and announced only if and when reached.

How does this case affect other tech companies?

The outcome will set important precedent for how antitrust law applies to digital platforms. If the FTC wins, Google, Amazon, Apple, and other tech giants will face increased scrutiny of their acquisitions and market dominance. If Meta wins, it suggests antitrust law provides limited tools for challenging platform monopolies, which would reduce risk for other tech companies pursuing aggressive acquisition strategies.

Is this the same as the FTC's 2020 divestiture case against Meta?

No, it's related but different. In 2020, the FTC filed a case seeking to force Meta to divest Instagram and WhatsApp, arguing the acquisitions were unlawful. Judge Boasberg rejected this in 2021, finding the acquisitions were lawful at the time they occurred. The current case, filed in 2023, argues that Meta used acquisitions to maintain an existing monopoly. It's the same judge and involves the same acquisitions, but it's technically a different legal theory and case.

What role does TikTok play in this appeal?

TikTok is central to the appeal because it represents the key disagreement between the FTC and Judge Boasberg. The FTC defined the relevant market narrowly to exclude TikTok, arguing that TikTok's primary value is algorithmic discovery. Boasberg found that TikTok's massive growth and user base proves the social networking market is competitive, making Meta's position less dominant than the FTC claimed. On appeal, the FTC will argue that TikTok's emergence after Meta's acquisitions doesn't erase past monopolistic conduct, while Meta will argue TikTok's success proves the market was always more competitive than the FTC claimed.

Could antitrust law change because of this case?

While this specific case won't directly change antitrust law, the outcome could influence how courts interpret existing antitrust statutes. The DC Circuit's decision on market definition will become precedent for future cases. If the court affirms a narrow market definition approach, it gives the FTC a tool for challenging tech acquisitions. If the court affirms a broad definition, it makes future antitrust cases against tech companies harder. Congress could also respond to the appeal's outcome by passing new antitrust legislation, though that would require legislative action independent of this case.

Related Concepts and Further Exploration

The Meta appeal involves several related antitrust and technology concepts worth understanding. Network effects, barriers to entry, and platform power are frequently discussed in tech antitrust cases. Digital markets regulation, data portability, and interoperability are potential remedies being discussed globally. Competition law in Europe through the Digital Markets Act provides a different regulatory approach that might influence U.S. thinking.

Consumer behavior in social media, algorithm design, and the impact of recommendation systems on competition and content availability are also relevant background contexts. Understanding how users actually switch between platforms and what drives their choices informs the economic analysis in antitrust cases.

The broader antitrust movement, including enforcement against Google, Amazon, and Apple, provides context for where the Meta case fits in the larger effort to address tech company dominance through law and regulation.

Key Takeaways

- The FTC appealed Judge Boasberg's November 2024 ruling finding the agency failed to prove Meta held a relevant market monopoly

- Market definition is the core dispute: FTC argues narrow personal social networking market where Meta dominates; Boasberg says broader social media market includes TikTok and YouTube competition

- Evidence of predatory acquisitions is strong, but only matters if monopoly power is proven in a legally relevant market

- TikTok's emergence and growth is central to the appeal. The FTC will argue timing doesn't eliminate past monopolistic conduct; Meta will argue current competition proves market was always competitive

- DC Circuit appeals take 18-24 months, meaning a decision is likely in 2026-2027, with potential Supreme Court review extending the timeline further

![FTC Appeals Meta Antitrust Ruling: What It Means for Big Tech [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ftc-appeals-meta-antitrust-ruling-what-it-means-for-big-tech/image-1-1768948610828.jpg)