General Fusion's Unexpected Pivot: From Struggling Startup to Billion-Dollar Public Company

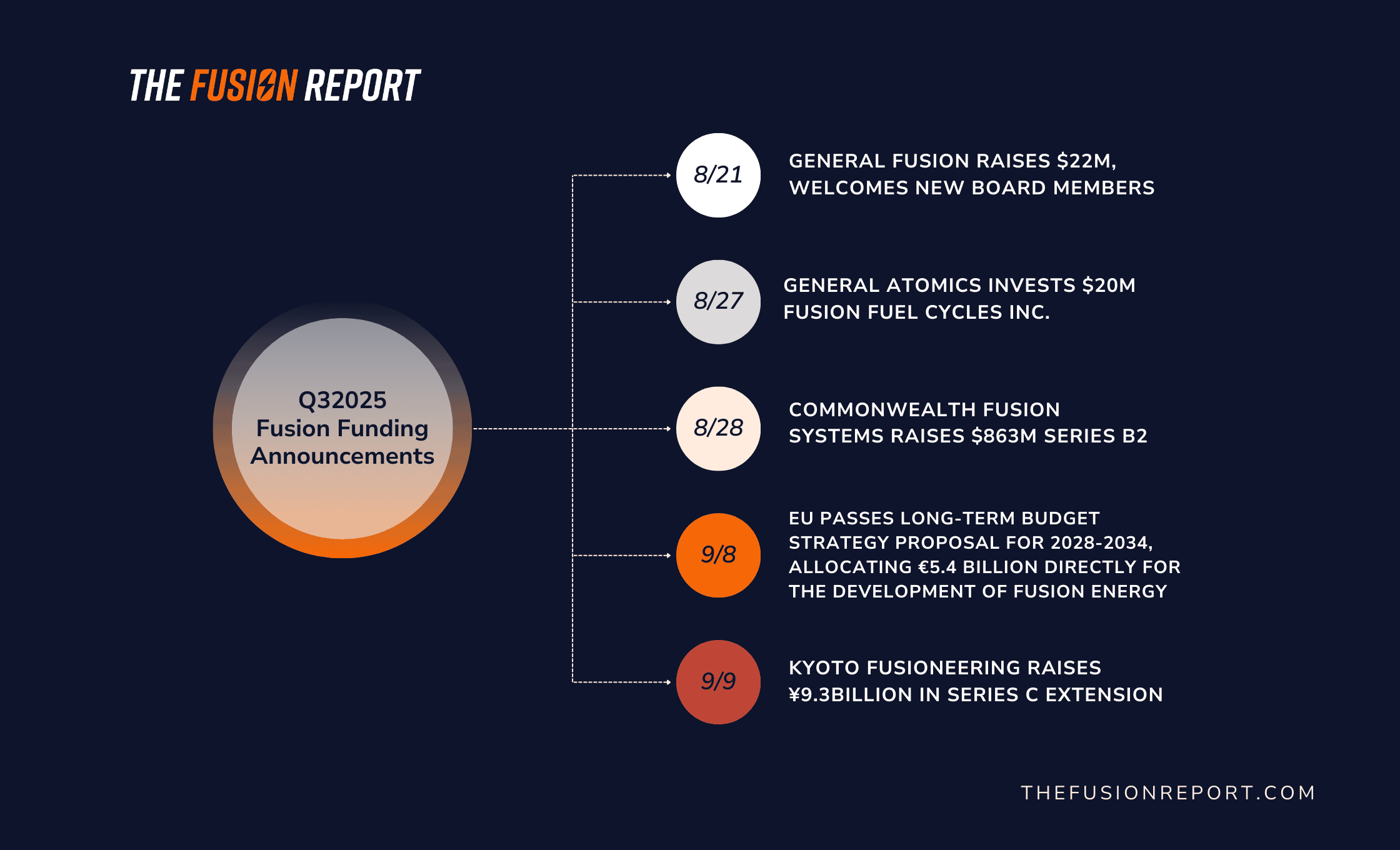

Sometimes survival in the energy sector looks a lot like evolution. General Fusion, a fusion power company that was quietly hemorrhaging cash and employees just twelve months ago, just announced it's going public. Not through a traditional IPO—those are for companies with proven revenue models and predictable growth paths. Instead, General Fusion is merging with Spring Valley III, a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), in a deal that values the combined entity at approximately $1 billion, as reported by GlobeNewswire.

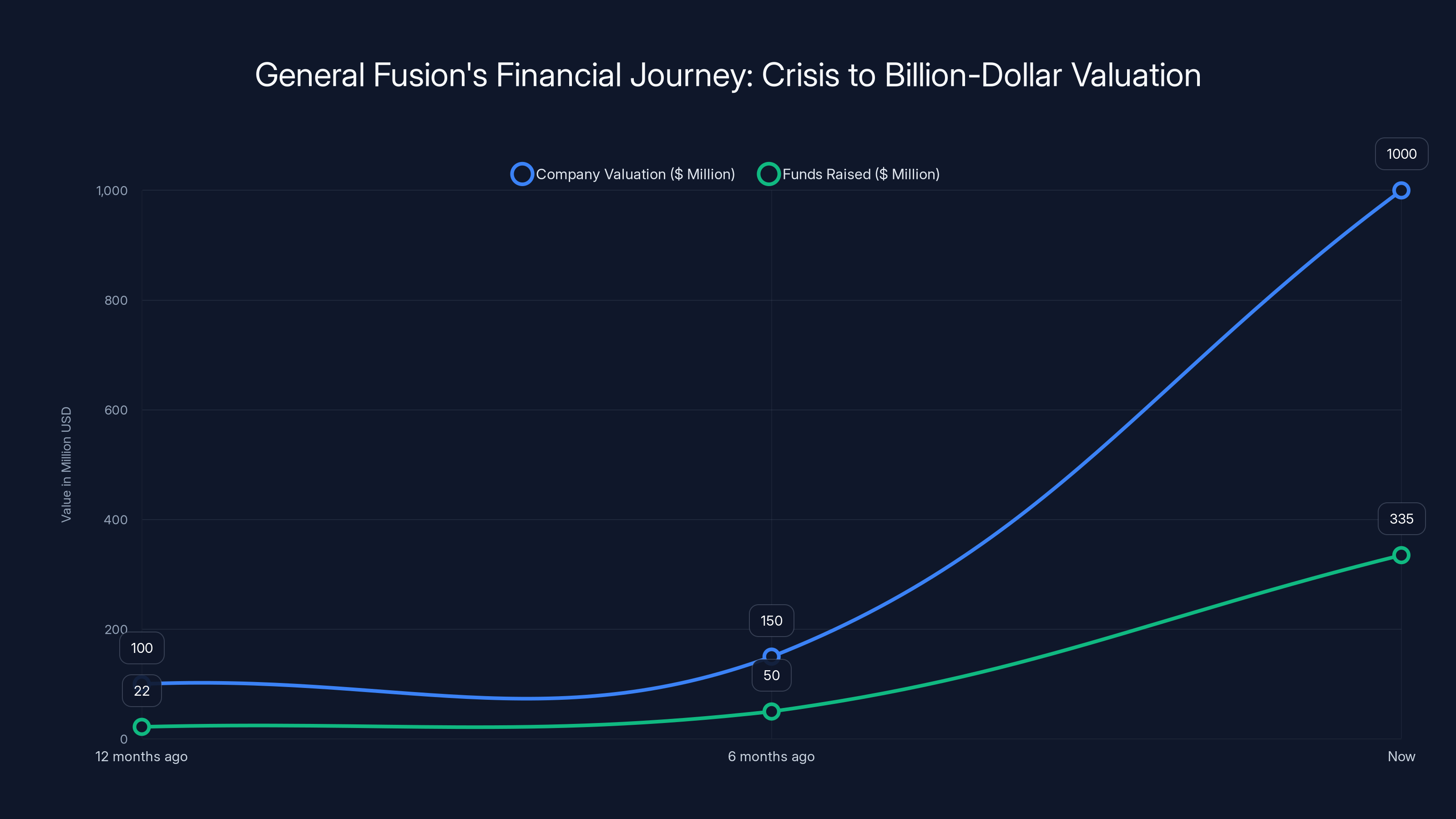

Let's set the stage here. Last year, General Fusion was in crisis mode. The company had laid off at least 25% of its workforce, according to BioSpace. Funding was nearly impossible to find. The CEO, in a moment of unusual transparency for the startup world, published a public letter basically asking investors not to abandon the company entirely. The company scraped together a $22 million lifeline investment—barely enough to keep the lights on for another year.

Now, fast forward twelve months. Instead of shutting down, General Fusion announced it would raise up to

But here's what makes this story genuinely interesting: it's not about General Fusion's technology suddenly becoming viable. It's about the fundamental economics of power, data centers, and why the entire energy landscape is shifting in ways that make fusion—even speculative, unproven fusion—suddenly look like a reasonable bet.

Understanding SPACs and Why Struggling Companies Choose Them

Let's pause on General Fusion for a moment and talk about what a SPAC actually is, because it's increasingly the path for deep-tech companies that can't—or won't—do a traditional IPO.

A SPAC is, in essence, a shell company created specifically to merge with a private company and take it public. The SPAC raises money from investors before it even knows what company it will acquire. These investors get shares and are essentially betting on the management team's ability to find and acquire a good company. Once a target is identified, the SPAC merges with that company, and the combined entity becomes a publicly traded company overnight.

The conventional wisdom used to be that SPACs were shortcuts for companies too risky for traditional IPOs. That reputation got worse after a wave of high-profile SPAC mergers from 2020–2021 that produced spectacular failures. We Work, whose failed IPO attempt preceded the SPAC era, later merged with Bow X Capital via SPAC (though results weren't exactly transformative). Nikola, the electric truck company, went public via SPAC in 2020 and later faced SEC investigations and founder fraud charges.

But if you're a deep-tech company burning cash faster than you can fundraise, and a traditional IPO means waiting years while your balance sheet deteriorates, a SPAC becomes compelling. The timeline is measured in months, not years. You get capital immediately. You go public without the roadshow exhaustion and endless earnings calls that traditional IPOs demand.

For General Fusion specifically, a SPAC made sense. The company is pre-revenue. It doesn't have the financial performance that IPO underwriters typically want to showcase. But it does have something: a specific technological vision, two decades of R&D investment, and increasingly favorable market conditions for energy companies.

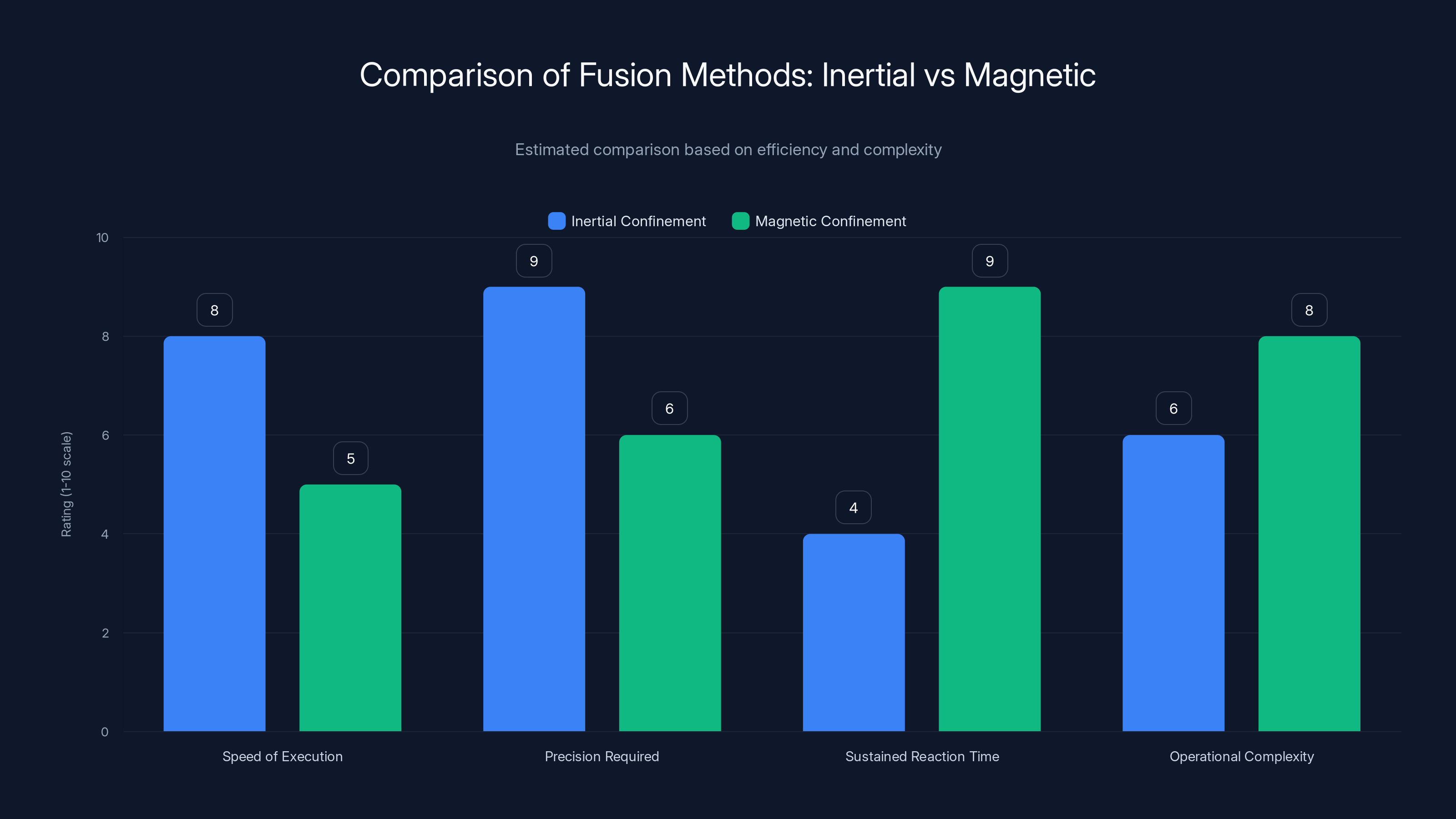

Inertial confinement fusion is faster and requires higher precision, while magnetic confinement offers longer reaction times but is more complex operationally. Estimated data.

The Spring Valley Play: A SPAC with an Energy Focus

Not all SPACs are created equal. Spring Valley III, the acquiring company, isn't some random blank-check vehicle. It's managed by investors who specialize in energy companies—specifically, energy companies in transition.

Spring Valley previously took Nu Scale Power public in 2022. Nu Scale is a small modular reactor (SMR) company, which means they're building smaller, cheaper nuclear reactors than traditional massive reactors. The technology is theoretically compelling: modular reactors could be factory-built, transported to remote locations, and deployed with less risk and capital than traditional nuclear plants.

Here's the catch: Nu Scale's stock price has fallen more than 50% from its peak. Why? Because the company disclosed that its first reactor project was going to cost significantly more than expected, and the utility partner backing the project got cold feet. This is genuinely relevant context for evaluating Spring Valley's track record. They take energy companies public, but there's no guarantee the market will reward them.

Spring Valley is also currently completing a merger with Eagle Energy Metals, a uranium mining company that's supposedly developing small modular reactor technology too. So Spring Valley's portfolio is increasingly concentrated in next-generation nuclear and fusion—the bet being that these technologies will eventually matter enormously.

The fact that Spring Valley chose to back General Fusion suggests they believe the company's technology path is credible. But it also reveals something about SPAC incentives: they need exits and acquisitions to generate returns. General Fusion gave them the opportunity to enter the fusion space, which is increasingly seen as a massive market opportunity.

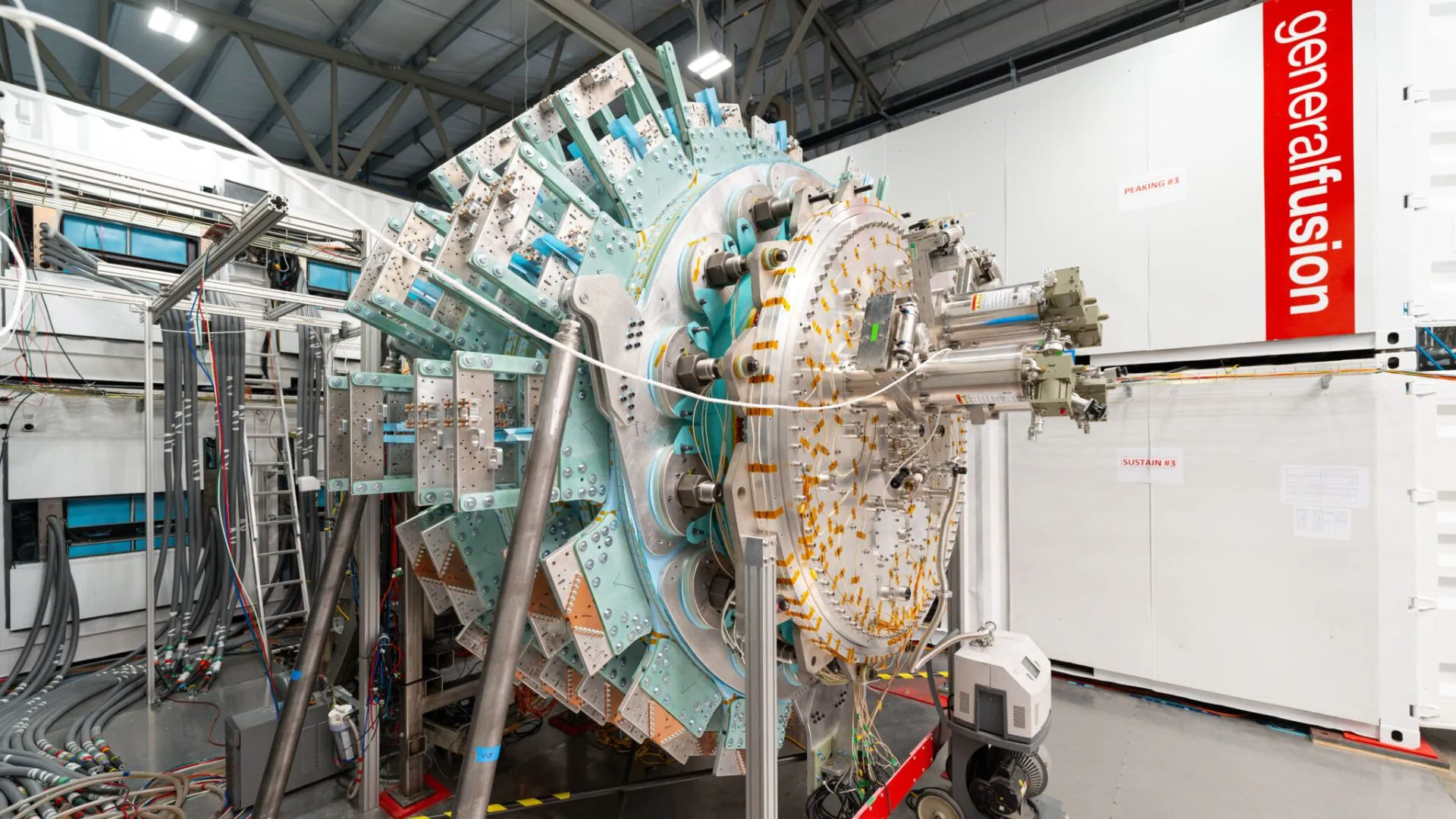

Lawson Machine 26: General Fusion's Technical Bet

Now let's talk about what General Fusion is actually trying to build, because the technology is where the actual risk lives.

General Fusion's core focus is a demonstration reactor called Lawson Machine 26 (LM26). The company uses an approach called inertial confinement fusion. The basic physics is straightforward: you take a fuel pellet made of deuterium and tritium (isotopes of hydrogen), compress it extremely quickly, and the pressure and heat causes the atoms to fuse, releasing enormous energy in the process.

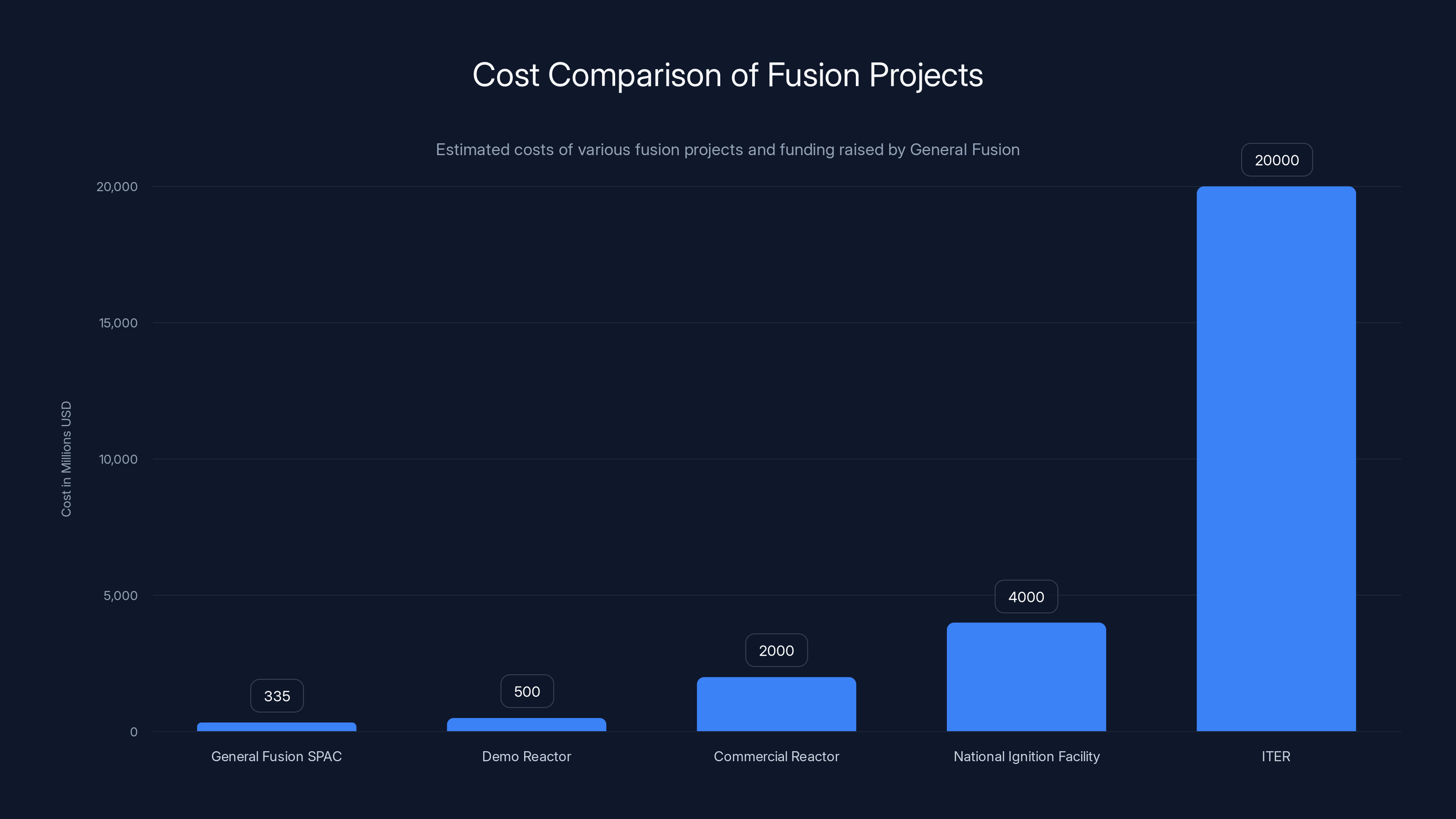

The challenge is achieving that compression efficiently. The National Ignition Facility (NIF), a government-funded facility in California, demonstrated fusion ignition using lasers in 2022. Specifically, they fired 192 laser beams at a fuel pellet, achieving inertial confinement fusion and producing more energy than the lasers directly delivered to the pellet. This was a major scientific milestone, but the system costs billions of dollars and uses massive laser systems.

General Fusion's approach? Avoid the lasers entirely. Instead of using extremely expensive and complex laser systems, or superconducting magnets (the approach used in magnetic confinement fusion designs like tokamaks), General Fusion uses steam-driven pistons. Here's how it works: steam pushes mechanical pistons that drive a wall of liquid lithium metal inward. This liquid metal wall compresses the fuel pellet, achieving inertial confinement without the need for expensive lasers or magnets.

The compressed fuel releases energy, which heats the liquid lithium. The hot lithium circulates through a heat exchanger, which generates steam to spin a generator and produce electricity.

On paper, this is elegant. No superconducting magnets (which need to be kept at near-absolute-zero temperatures and are expensive as hell). No laser systems that cost billions. Instead, mechanical systems that are theoretically cheaper to build and deploy.

The bet is that by avoiding these expensive subsystems, General Fusion can build a fusion power plant for substantially less money than competitors, making fusion economically viable.

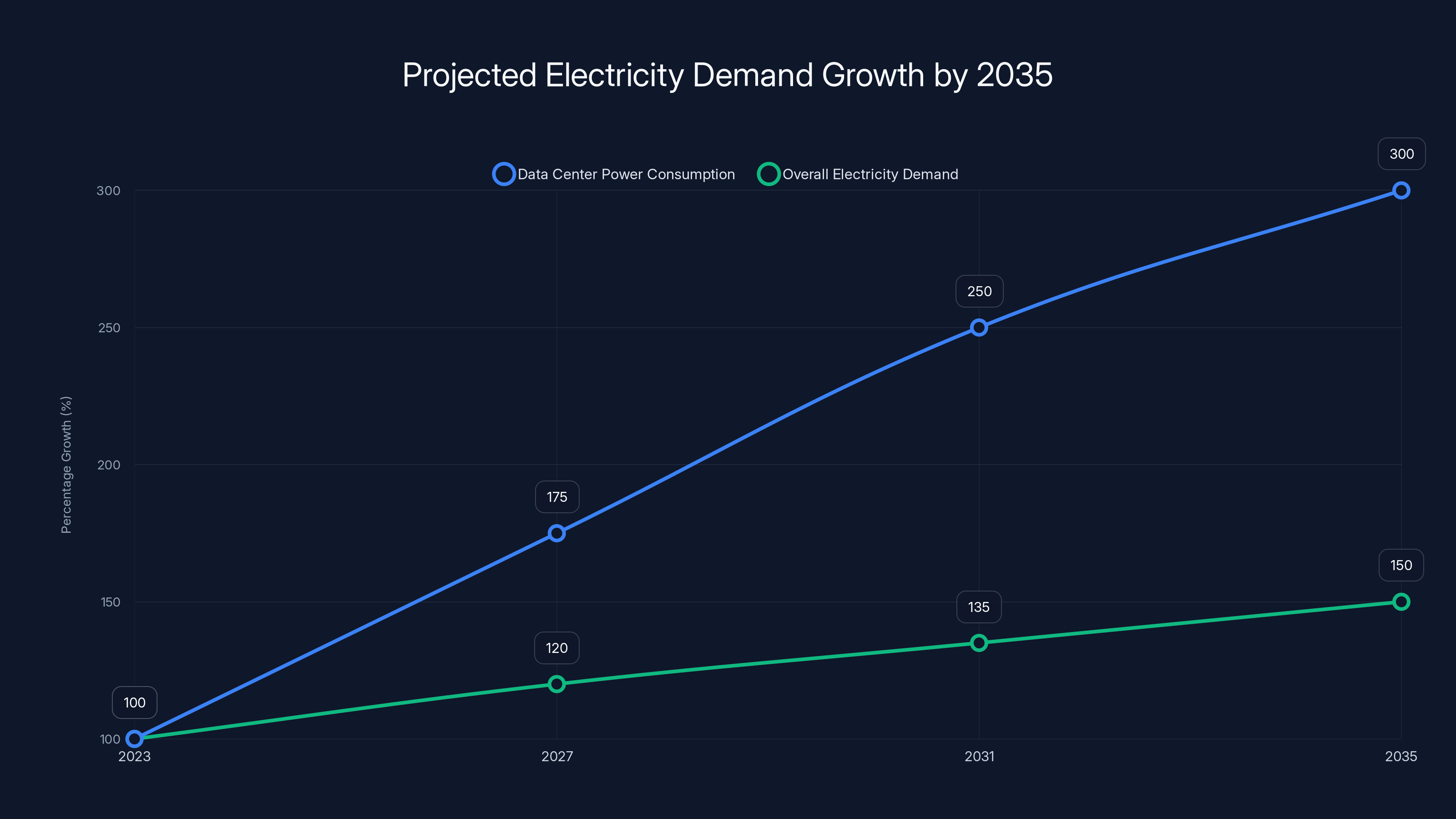

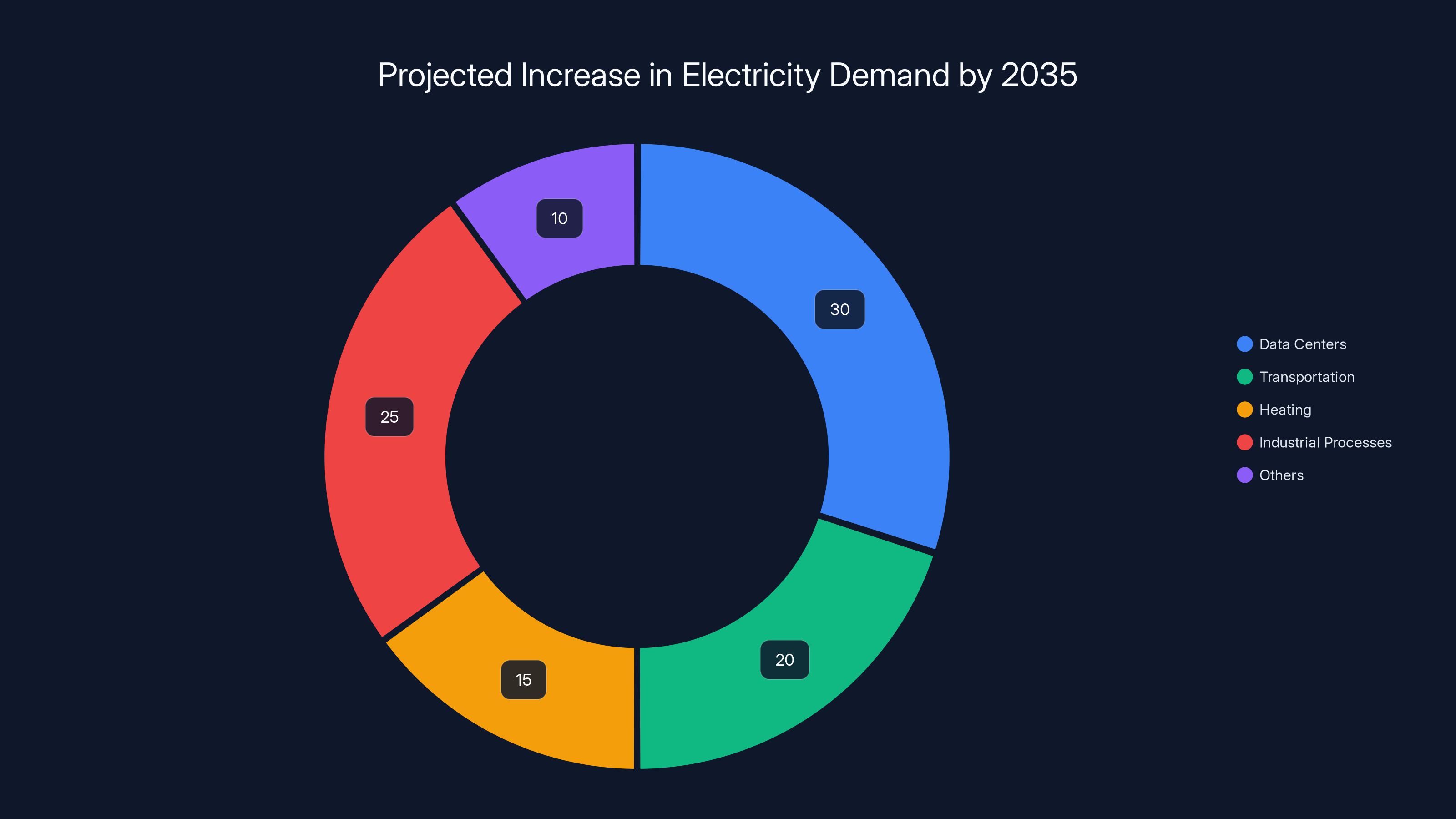

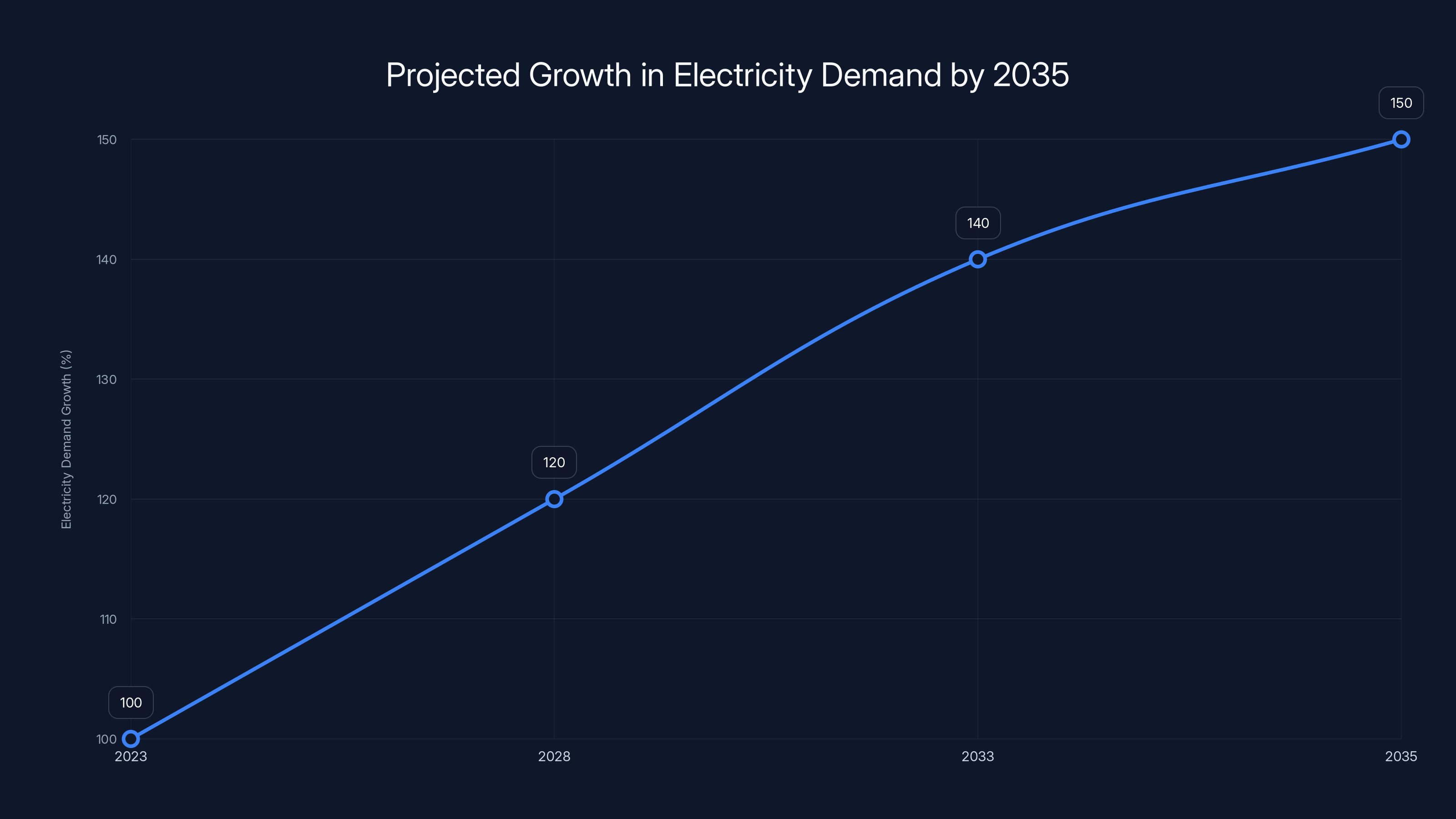

Data center power consumption is projected to grow by 300% by 2035, while overall electricity demand is expected to increase by 50%, highlighting the need for new power sources. Estimated data.

The Scientific Breakeven Problem: Why One Milestone Doesn't Equal Commercial Viability

General Fusion stated that in 2026, LM26 would achieve scientific breakeven. This is a specific technical milestone that's worth understanding, because it's both significant and potentially misleading.

Scientific breakeven means a fusion reaction generates more energy than was directly applied to compress the fuel pellet. At NIF, they achieved this in 2022. It was a major news story and a legitimate scientific breakthrough.

But—and this is crucial—scientific breakeven is not the same as commercial breakeven.

Commercial breakeven means a fusion reactor generates enough electricity to export power to the grid after accounting for all the energy needed to run the reactor itself. This includes the energy to compress the pellets, the cooling systems, the generator, the control systems, and all the operational overhead.

The gap between scientific and commercial breakeven is enormous. NIF achieved scientific breakeven in 2022, but the National Ignition Facility consumes roughly 400 megawatts of power to run. The laser facility uses vast amounts of electricity just to operate. Meanwhile, the actual fusion reaction produces far less energy than the facility consumes.

General Fusion hasn't commented on whether they've adjusted their timeline or expectations for commercial breakeven. Getting to scientific breakeven in 2026 would be impressive. Getting to commercial breakeven within a decade would be genuinely revolutionary.

This is where investor optimism and physical reality sometimes diverge. When a fusion company announces it will hit scientific breakeven, it sounds transformative. And scientifically, it is. But it doesn't necessarily mean the company is close to producing profitable power.

Why Data Centers Changed Everything: The Demand Equation

Here's what makes General Fusion's timing genuinely interesting: the energy demand landscape shifted dramatically, and nobody was really paying attention.

Data centers consume an enormous and rapidly growing amount of electricity. Large language model training and inference require serious compute, which requires serious power. Bloomberg NEF estimates that data centers will consume nearly 300% more power by 2035 compared to current levels. That's not a marginal increase. That's a fundamental shift in global electricity demand.

General Fusion's merger announcement explicitly calls this out. The company points to rising data center energy demand as a key driver for its investment thesis. And honestly, they're not wrong.

Data center operators are increasingly desperate for reliable, baseload power sources. Solar and wind are intermittent—they don't run 24/7. Battery storage is expensive and has limited duration. Nuclear is the traditional answer, but new nuclear plants take 10+ years to build and face enormous political and regulatory friction.

Fusion, if it works, offers something genuinely different: high-density, baseload, carbon-free power that doesn't face the same regulatory and political hurdles as nuclear fission. From a data center operator's perspective, if fusion becomes commercially viable, they'd absolutely be interested in it.

This demand dynamic is why fusion startups suddenly have a more credible investment narrative. It's not just that the technology is progressing. It's that the economic incentives suddenly exist to deploy it.

The Broader Electrification Trend: Beyond Data Centers

But the story is even bigger than data centers, which is something General Fusion also mentioned in its merger announcement.

Electric vehicles, electric heating systems, and broader industrial electrification are expected to increase overall electricity demand by up to 50% by 2035. This isn't speculative. It's based on existing policies, announced commitments, and current adoption trends.

Consider transportation: in many countries, internal combustion vehicles are being phased out. Norway, for example, has already reached the point where more than 80% of new vehicle sales are electric. Europe is mandating a transition to electric vehicles. China is doing the same. As those vehicles proliferate, charging infrastructure demands enormous amounts of electricity.

Consider heating: in cold climates, residential and commercial heating traditionally relied on natural gas. Electrifying that heating (using electric heat pumps and similar technology) is more efficient but requires more electricity from the grid.

Consider industrial processes: manufacturing, steel production, chemical processes—these are all traditionally powered by fossil fuels or derived electricity. Decarbonizing these processes means electrifying them, which means tremendous electricity demand growth.

Add it all together: data centers (300% growth), transportation electrification, heating electrification, industrial decarbonization, and you get a scenario where electricity demand could increase 50% or more in the next decade.

The existing grid infrastructure isn't set up for this. Traditional fossil fuel plants are being retired faster than replacements are being built. Renewable capacity is growing, but wind and solar have capacity factor limitations. Nuclear could help, but new plants take a decade to permit and build.

In this context, fusion becomes less of a speculative science experiment and more of a pragmatic solution to a genuine infrastructure problem. If General Fusion (or any fusion company) can deploy a reactor that produces reliable baseload power at reasonable cost, there will be substantial demand for it.

General Fusion's valuation skyrocketed from an estimated

Learning from TAE Technologies: The Fusion Company IPO Precedent

General Fusion isn't the first fusion company to go public. In December 2024, TAE Technologies announced a merger with Trump Media & Technology Group in a deal valuing the combined company at over $6 billion.

That's a wild valuation for a pre-revenue fusion company, and it deserves some skepticism. Trump Media itself has been a financial disaster—the SPAC that took it public merged with Trump's social media venture when Trump Media had minimal revenue and was burning cash at an alarming rate. TAE Technologies merging with Trump Media feels more like finding a partner for a joint press conference than a genuine strategic combination.

But the point is: fusion companies are now going public. The market is willing to engage with them. The capital is flowing, however chaotically.

General Fusion's SPAC deal is more straightforward than TAE's situation. Spring Valley isn't burdened with Trump Media's baggage. The valuation is lower. The capital structure is cleaner.

That said, General Fusion will face market scrutiny. If the company doesn't hit its scientific breakeven milestone in 2026, or if progress on LM26 slows down, the stock will suffer. SPAC mergers are faster than traditional IPOs, but they create public shareholders who will eventually demand results.

The Nu Scale Cautionary Tale: Why SPAC Success Isn't Guaranteed

Remembering Spring Valley's previous deal with Nu Scale is important here. Nu Scale seemed like a solid bet: small modular reactors sound good in theory. The Department of Energy and the private sector were backing the technology. Nu Scale partnered with utility company Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS) to build a demonstration project.

Then reality hit. The first Nu Scale project, scheduled to be built in Idaho, started experiencing cost overruns. The project cost grew from an estimated

Nu Scale's stock tanked. The company's valuation narrative collapsed not because the technology didn't work, but because the economics didn't work. A small modular reactor, it turned out, might be technologically feasible but commercially uncompetitive versus other power generation options.

This is the existential risk for General Fusion. The company could achieve scientific breakeven with LM26. The reactor could theoretically work. But if the cost of building a commercial fusion power plant turns out to be more than $10 billion, the project becomes uneconomical compared to renewables plus battery storage, or next-generation nuclear fission designs, or other alternatives.

General Fusion's thesis is that avoiding expensive lasers and superconducting magnets will keep costs down. But this is still a prediction. The actual cost of deploying a commercial fusion reactor remains unknown.

The Capital Efficiency Question: Why $335 Million Might Not Be Enough

General Fusion is raising up to $335 million through the SPAC merger (though not all of this is committed; some is contingent on specific conditions). This is real money, and it's substantial compared to what most deep-tech startups get.

But consider the scale: building a demonstration reactor costs hundreds of millions. Building a commercial reactor that actually produces electricity for a grid and generates profit? That could cost billions. The National Ignition Facility cost nearly

General Fusion's capital raise of $335 million is enough to complete LM26 and maybe start preliminary design work on a commercial prototype. But it's probably not enough to build a full commercial reactor and deploy it.

This means General Fusion will need additional capital. Lots of it. And the market for deep-tech capital isn't infinite. If the company hits scientific breakeven in 2026, they might be able to raise Series E funding or attract strategic investors. But that's a big "if." And even if they succeed scientifically, the commercial path becomes dependent on finding investors willing to bankroll billion-dollar capital projects on the bet that fusion will be economically viable.

This is actually where SPAC funding has an advantage over traditional venture capital. Once public, General Fusion can potentially access debt markets, strategic partnerships with utilities or data centers, and even government support. Those capital sources are harder to access as a private company.

Electricity demand is projected to increase by 50% by 2035, driven by data centers, transportation, heating, and industrial processes. Estimated data.

Market Timing: Is 2026 the Right Year for Fusion?

General Fusion is announcing this deal in early 2026, just as the company is supposedly hitting scientific breakeven. This isn't random timing.

The company's narrative is straightforward: we proved the technology works, now the market is ready. Data centers need power. Electricity demand is growing. Fusion could be part of the solution.

But timing in capital markets is notoriously unpredictable. If the global economy enters a recession before General Fusion completes its SPAC merger and goes public, the valuation could crater. If energy prices collapse, the urgency around new power sources might diminish. If traditional nuclear fission (or renewables plus storage) demonstrate dramatic cost reductions, fusion becomes less attractive.

Conversely, if energy prices spike, or if data center demand accelerates beyond current forecasts, or if another geopolitical event constrains energy supplies, General Fusion could benefit enormously from being a public company with access to capital and strategic investors at exactly the right moment.

Fusion is a high-risk, high-reward bet. The market timing on going public during a theoretical breakeven milestone could be perfect, or it could be terrible. We won't know for a few years.

The Political and Regulatory Landscape: Tailwinds and Uncertainty

Here's where things get interesting (and a bit uncertain). General Fusion's SPAC merger was announced in a specific political and regulatory context.

The Trump administration's stated skepticism toward an electrified future—specifically, the administration's rollback of EV subsidies and climate policies—creates uncertainty about the long-term demand for carbon-free power. If the U. S. government stops pushing electrification through policy and subsidies, the demand picture for fusion (and renewables) becomes murkier.

But here's the counterpoint: other countries are charging ahead aggressively. The European Union is accelerating electrification. China is deploying renewable capacity and electric vehicles at scales that dwarf the United States. India is building massive renewable infrastructure. Even if the U. S. government is skeptical, global electricity demand is still going to grow dramatically.

Moreover, the data center demand story is almost independent of policy. Tech companies need power regardless of government climate policy. If anything, data center operators in the U. S. might be MORE interested in avoiding regulatory uncertainty by deploying power sources that don't depend on government subsidies or climate commitments.

Regulatory approval for a new fusion reactor? That's another uncertainty entirely. Nuclear regulators (the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in the U. S.) would need to approve any commercial deployment. The regulatory framework for fusion doesn't really exist yet at commercial scale. This could be fast-tracked if the technology is proven, or it could be extraordinarily slow if regulators are cautious.

General Fusion is being relatively quiet about regulatory timelines, which suggests they're either confident or uncertain—hard to tell which.

Comparing General Fusion to Other Fusion Approaches

General Fusion isn't the only fusion company pursuing inertial confinement approaches. TAE Technologies, which is going public via Trump Media merger, is pursuing a different approach called field-reversed configurations. Commonwealth Fusion Systems (a spinoff from MIT) is pursuing magnetic confinement fusion with high-temperature superconductors. Helion Energy is pursuing inertial confinement with electric-driven fusion.

Each approach has theoretical advantages and disadvantages. General Fusion's hydraulic approach (using pistons and liquid lithium) is supposed to be cheaper than laser-based systems. But Commonwealth Fusion Systems' high-temperature superconducting magnets are getting cheaper too. And laser technology is advancing—General Fusion is betting that mechanical systems will scale more cheaply, but that's not certain.

The fusion landscape is diverse. Multiple companies are pursuing different technical approaches, which is healthy competition. But it also means General Fusion is competing for attention, talent, and capital against well-funded competitors. Commonwealth Fusion Systems, for example, has raised over $500 million from major investors including Google and Breakthrough Energy Ventures.

General Fusion's

Electricity demand is projected to grow by 50% by 2035, driven by EV adoption and industrial electrification. Estimated data.

The Path Forward: Milestones and Market Tests

General Fusion's immediate path is clear: complete the SPAC merger (which should happen in 2026), hit scientific breakeven with LM26 (also supposedly 2026), and then begin preliminary design work on a commercial prototype.

The challenging part is what comes after that. The company will need to demonstrate that a commercial fusion reactor is economically viable. This means building a prototype, deploying it, and showing that it can generate electricity profitably.

This is where the company's capital efficiency and technical execution become critical. If the company can build a demonstration reactor that proves the concept works, and if the cost trajectory suggests commercial viability, then General Fusion might attract strategic investors (utilities, energy companies, data center operators) willing to bankroll commercial deployment.

If the company hits scientific breakeven but can't demonstrate a path to commercial viability, the stock could crater. SPAC shareholders will eventually demand results.

What's fascinating about General Fusion's situation is that the company is now incentivized to execute rapidly. As a public company, there's pressure to hit milestones and deliver results. That can be motivating or it can be destabilizing. Some deep-tech companies thrive with that pressure; others become risk-averse and slow down.

Electrification Megatrends: The Real Driver

Ultimately, General Fusion's survival and eventual success depends on broader megatrends that are largely outside the company's control.

If electricity demand really does grow 50% by 2035 due to EV adoption, industrial electrification, and heating electrification, then the grid will need new power sources. Renewables will provide much of this, but baseload power will still be needed. Fusion, if it becomes commercially viable, could fill that gap.

But if electricity demand grows more slowly, or if renewables plus battery storage prove sufficient, then fusion becomes less urgently needed. And if other power sources become cheaper (next-generation nuclear fission, advanced geothermal, or something unexpected), fusion might become uncompetitive.

General Fusion is betting that electrification trends are real and accelerating. The data supports this: EV adoption is accelerating, renewable deployment is accelerating, and industrial decarbonization is beginning. But these trends face potential headwinds from policy changes, economic slowdowns, or technological breakthroughs in competing energy sources.

The company's $1 billion valuation implicitly prices in success on these trends. If the trends materialize, General Fusion could be hugely valuable. If they don't, the company's prospects dim significantly.

The Investment Thesis: What Investors Actually Believe

Investors backing General Fusion's SPAC merger aren't betting primarily on the company's ability to hit scientific breakeven in 2026. That's important, but it's not the core thesis.

Investors are betting on three things:

First, that the global electricity demand picture is genuinely shifting due to electrification and data center growth. This is supported by solid evidence and is becoming conventional wisdom in energy circles.

Second, that fusion power is a credible solution to this demand growth. This is more speculative, but it's increasingly accepted even by skeptics that fusion could work.

Third, that General Fusion specifically has a technological approach that could lead to commercially viable fusion power. This is where the bet gets specific to the company, and it's the most speculative part.

If all three of these prove correct, General Fusion could be enormously valuable. If any one of them proves wrong, the company's prospects diminish.

The SPAC valuation at

General Fusion's $335 million SPAC funding is substantial but falls short compared to the billions required for full-scale fusion projects like ITER, highlighting the need for additional capital. Estimated data.

Lessons from the Funding Crisis Year

It's worth circling back to what happened last year, when General Fusion nearly collapsed.

The company laid off 25% of staff and nearly ran out of money. This suggests that the business model—raising capital from venture investors, traditional energy companies, and government grants—was breaking down. Investors were getting tired of betting on long-term technical milestones without seeing revenue or clear commercialization paths.

The $22 million lifeline investment kept the company alive, but it wasn't a solution. The SPAC merger is the solution. It's a different capital model: instead of convincing specialized venture investors or energy companies to fund a risky fusion bet, the company goes public and lets public markets (hopefully) provide patient capital.

This is where the SPAC model has genuine advantages for deep-tech companies. Traditional venture capital has gotten less patient with long-term bets. But public markets have endless capital and can hold longer-term views (for better or worse).

General Fusion is betting that going public will relieve the immediate capital pressure and allow the company to focus on technology milestones. That's a reasonable bet, assuming the stock doesn't crater immediately after the SPAC merger closes.

Risks and Uncertainties: What Could Go Wrong

Let's be blunt about what could derail General Fusion:

Technical risk: LM26 might not achieve scientific breakeven in 2026. The demonstration reactor could reveal fundamental problems with the hydraulic inertial confinement approach. The company could be years away from scientific breakeven, and years after that from commercial viability.

Competitive risk: Another fusion company could achieve scientific breakeven first, drawing attention and capital away from General Fusion. Commonwealth Fusion Systems or other competitors could demonstrate superior technology or capital efficiency.

Market risk: Electricity demand might not grow as fast as forecasted. Renewables plus battery storage might prove sufficient without needing fusion. Economic recession could dampen both electrification and data center growth.

Capital risk: Even with $335 million, the company might need substantially more capital to reach commercial viability. If the stock price tanks after the SPAC merger, future capital raises become much more difficult.

Regulatory risk: Deploying a commercial fusion reactor might face unexpected regulatory hurdles. The NRC or other regulators might be more cautious than the company expects.

Execution risk: Management changes, team departures, or project delays could derail milestones. Deep-tech companies often struggle with execution at scale.

Any one of these risks could significantly impact General Fusion's trajectory. Investors should recognize this, even though the investment narrative is compelling.

Looking Ahead: What Success Actually Looks Like

Here's what success looks like for General Fusion, realistically:

2026: Hit scientific breakeven with LM26. This is the company's stated goal, and it would be a major achievement. Stock prices would probably rally if this happens.

2027-2029: Begin design and preliminary deployment of a prototype commercial reactor. Partner with a utility, data center operator, or government agency willing to host the prototype.

2030-2035: Build and deploy the prototype. Collect operational data. Prove that the reactor can run continuously, maintain performance, and handle maintenance cycles.

2035+: If the prototype works and shows a path to profitability, begin building commercial reactors. Scale manufacturing. Deploy to multiple locations.

This is a 10+ year timeline to actual commercial deployment. That's the realistic horizon for transformative technology. Investors buying General Fusion stock should recognize they're making a 10-year bet, not a 2-year bet.

If the company executes flawlessly on this timeline, the stock could be worth multiples of its current valuation. If the company hits snags—which deep-tech companies almost always do—progress slows dramatically.

The Broader Context: Why Fusion Suddenly Matters

Ten years ago, fusion was widely viewed as perpetually 30 years away. Physicists had been saying "fusion is always 30 years in the future" for so long it became a joke.

What changed? Several things:

First, laser technology improved. NIF achieved fusion ignition in 2022, proving that the basic physics was sound.

Second, superconducting magnet technology improved. High-temperature superconductors became more practical, enabling better magnetic confinement designs.

Third, computational modeling improved. Engineers can simulate fusion reactions more accurately, reducing trial-and-error in reactor design.

Fourth—and this is crucial—the economics of power changed. With electrification megatrends creating genuine electricity demand growth, fusion stopped being a nice-to-have and became a must-have solution. The market incentives shifted from "wouldn't fusion be cool" to "we actually need fusion to meet our energy goals."

General Fusion is going public at exactly the moment when fusion has stopped being a physics experiment and has become an economic necessity. That timing is the company's greatest advantage.

Conclusion: The Survival Strategy That Became an Opportunity

General Fusion's SPAC merger isn't a success story yet. It's a pivotal moment. The company went from near-death to billion-dollar valuation in twelve months, but that happened because of broader market conditions, not because the company's technology suddenly became viable.

The real test comes now. General Fusion must hit scientific breakeven in 2026. It must demonstrate a credible path to commercial viability. It must execute on a long-term technology roadmap while managing public market expectations.

That's hard. Really hard. Most deep-tech companies fail to execute on promises made during public offerings. But General Fusion has several advantages: alignment with electricity demand megatrends, a plausible technical approach, reasonable capital resources, and experienced management (the CEO weathered the crisis and lived to pursue this strategy).

The stock will be volatile. The technology path will face setbacks. The timeline will likely extend beyond current expectations. But if fusion is genuinely going to be part of the energy landscape—and the evidence suggests it might be—then General Fusion's decision to go public now, while the market is receptive and electricity demand is surging, was exactly the right call.

Investors should buy General Fusion stock with eyes wide open about the risks. But they should also recognize that betting on fusion power in 2026 is not the speculative moonshot it would have been ten years ago. The physics is proven. The market demand is real. The capital is available.

What General Fusion needs to prove is the execution. And for a company that was nearly bankrupt a year ago, reaching this point is already an impressive achievement.

![General Fusion's $1B SPAC Merger: Fusion Power's Survival Strategy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/general-fusion-s-1b-spac-merger-fusion-power-s-survival-stra/image-1-1769103487143.jpg)