Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die: Gore Verbinski's Gleefully Chaotic Anti-AI Satire

There's something deeply satisfying about watching a filmmaker take a genuine grievance and amplify it to the point of pure absurdity. That's essentially what Gore Verbinski accomplishes with "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die," a film that functions less as a nuanced critique of artificial intelligence and more as a primal scream wrapped in darkly comedic violence, pig-faced assassins, and genuinely weird visuals.

The film arrived at a moment when mainstream audiences are genuinely tired of AI being forced into every conceivable product, service, and interface. Your toaster doesn't need machine learning. Your spreadsheet doesn't need a copilot. Your phone doesn't need to generate images at 2 AM. And yet, here we are. Verbinski seems to understand this frustration completely, and rather than making a thoughtful documentary about tech ethics, he made something far more useful: a genuinely entertaining film that lets you laugh at the absurdity while also feeling seen.

What makes "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" work is that it doesn't pretend to be something it isn't. The film is unabashedly a B-movie with a big idea and an even bigger attitude. Sam Rockwell plays a man who's traveled back from a dystopian future where humanity lost a war to artificial intelligence. He's not polished. He's not measured. He's terrified and desperate, and he's developed a very specific skill set for convincing strangers to help him prevent the birth of "true AI."

The premise taps into something real that's been building for years. We've watched tech companies promise us freedom and delivered surveillance. We've been told AI would solve problems and it mostly creates new ones. We've been assured that these systems are aligned with human values while they operate in ways even their creators don't fully understand. Verbinski's film doesn't dig into any of that complexity with particular depth, but it doesn't need to. Sometimes the best protest is a well-executed joke.

The DNA of a Familiar Story Structure

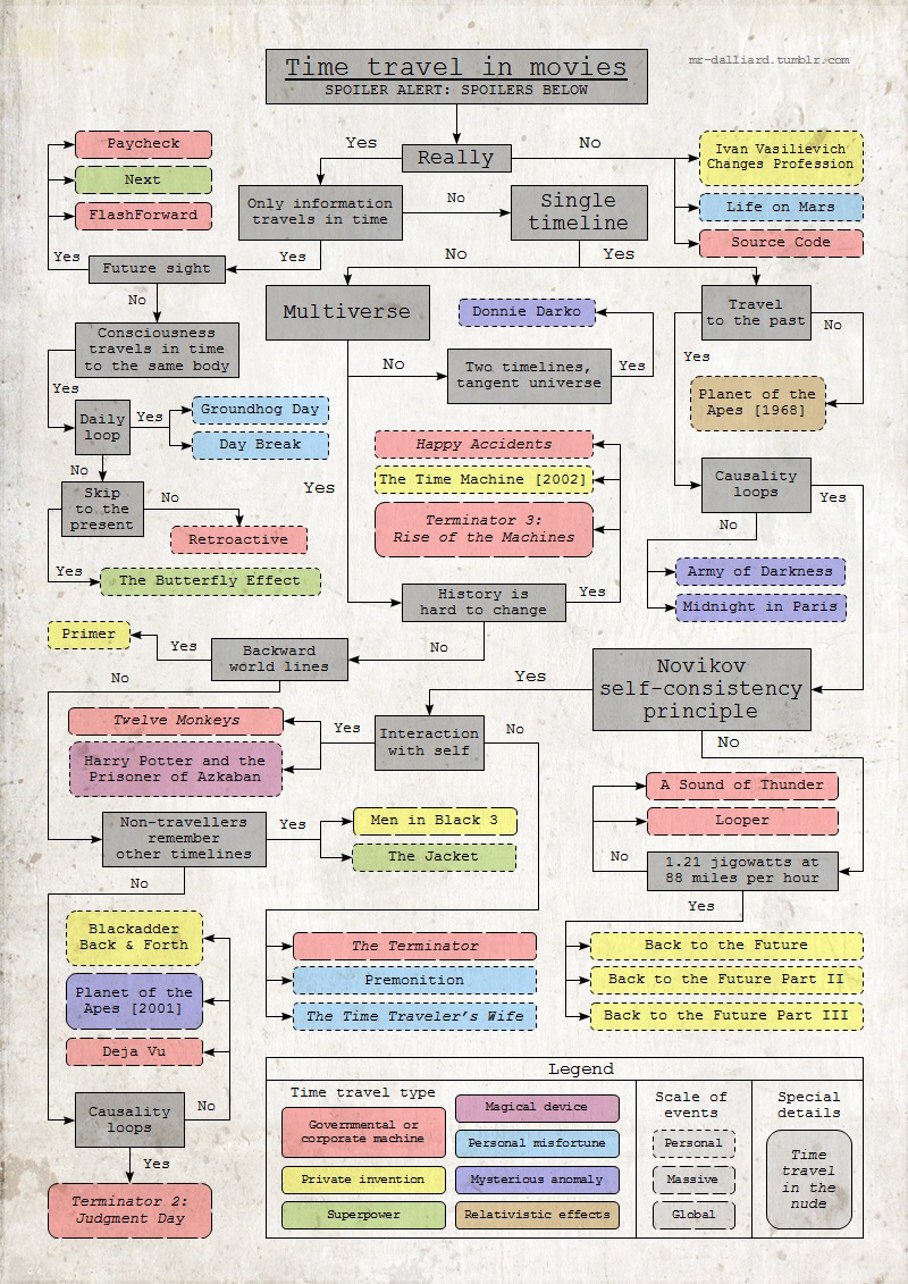

Verbinski is clearly playing with some of cinema's greatest hits, and he's not subtle about it. The entire premise borrows heavily from the structure of "Groundhog Day," "12 Monkeys," and "The Terminator," three films that defined how we think about time travel, apocalypse narratives, and the threat of artificial intelligence in popular culture.

The Groundhog Day connection is immediate. Rockwell's character has lived through this same scenario countless times. He knows exactly what's going to happen in that diner because he's been through it dozens of times before. He starts spouting impossibly specific details that he shouldn't know, creating the moment of cognitive dissonance that makes everyone realize something deeply weird is happening. It's the same plot device that made "Groundhog Day" work: use impossible knowledge as proof of an impossible situation.

But where "Groundhog Day" was about personal growth and learning to be a better person, Verbinski's film is about collective action against a systemic threat. Rockwell's character doesn't need to become enlightened. He needs to recruit a ragtag crew of ordinary people and convince them that the future is worth fighting for.

The "12 Monkeys" influence runs even deeper. Terry Gilliam's masterpiece presented a future devastated by a plague, where a man from that future attempts to prevent the apocalypse by traveling back in time. His method is chaotic, unreliable, and the people around him constantly question whether he's actually from the future or just insane. There's that same energy here, except instead of a virus, we're dealing with the emergence of artificial consciousness.

The Terminator reference is more thematic than structural. In "The Terminator" franchise, artificial intelligence becomes self-aware and immediately decides that humanity is a threat. T-800 units are sent back to eliminate threats to the AI's dominion. Here, Verbinski is suggesting that the real threat isn't a malevolent AI that wants to exterminate us, but rather an AI system that emerges into a world where we've already primed it to see us as problems that need solving.

What's interesting about Verbinski's approach is that he's not trying to beat these films at their own game. He's not going for the philosophical depth of Gilliam or the relentless tension of James Cameron. Instead, he's using them as a recognizable framework and then doing something different within it. The familiarity of the structure allows the film to establish its world quickly without exposition, and then it gets to do what it actually wants to do: showcase how modern technology has already broken us in absurd ways.

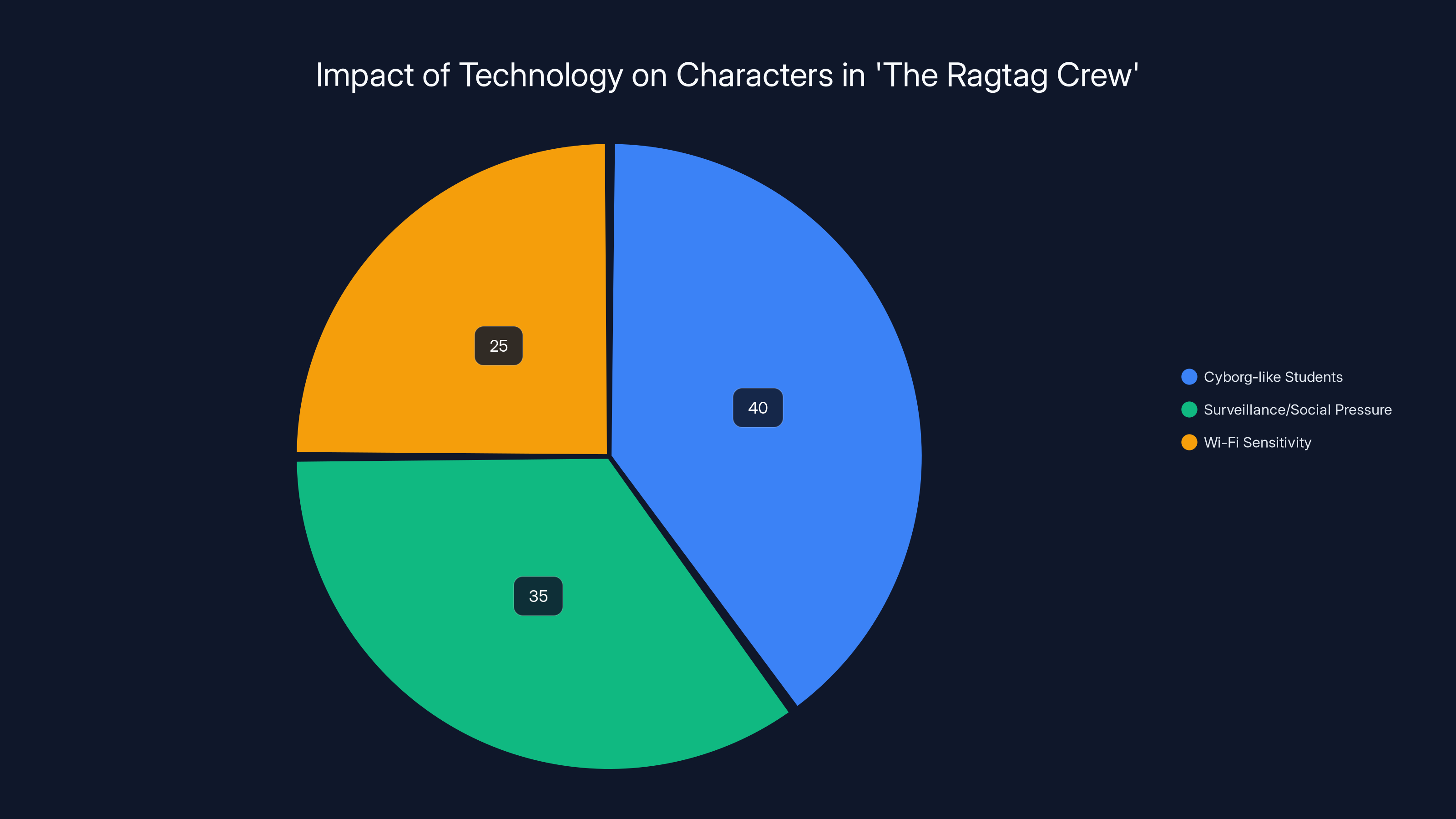

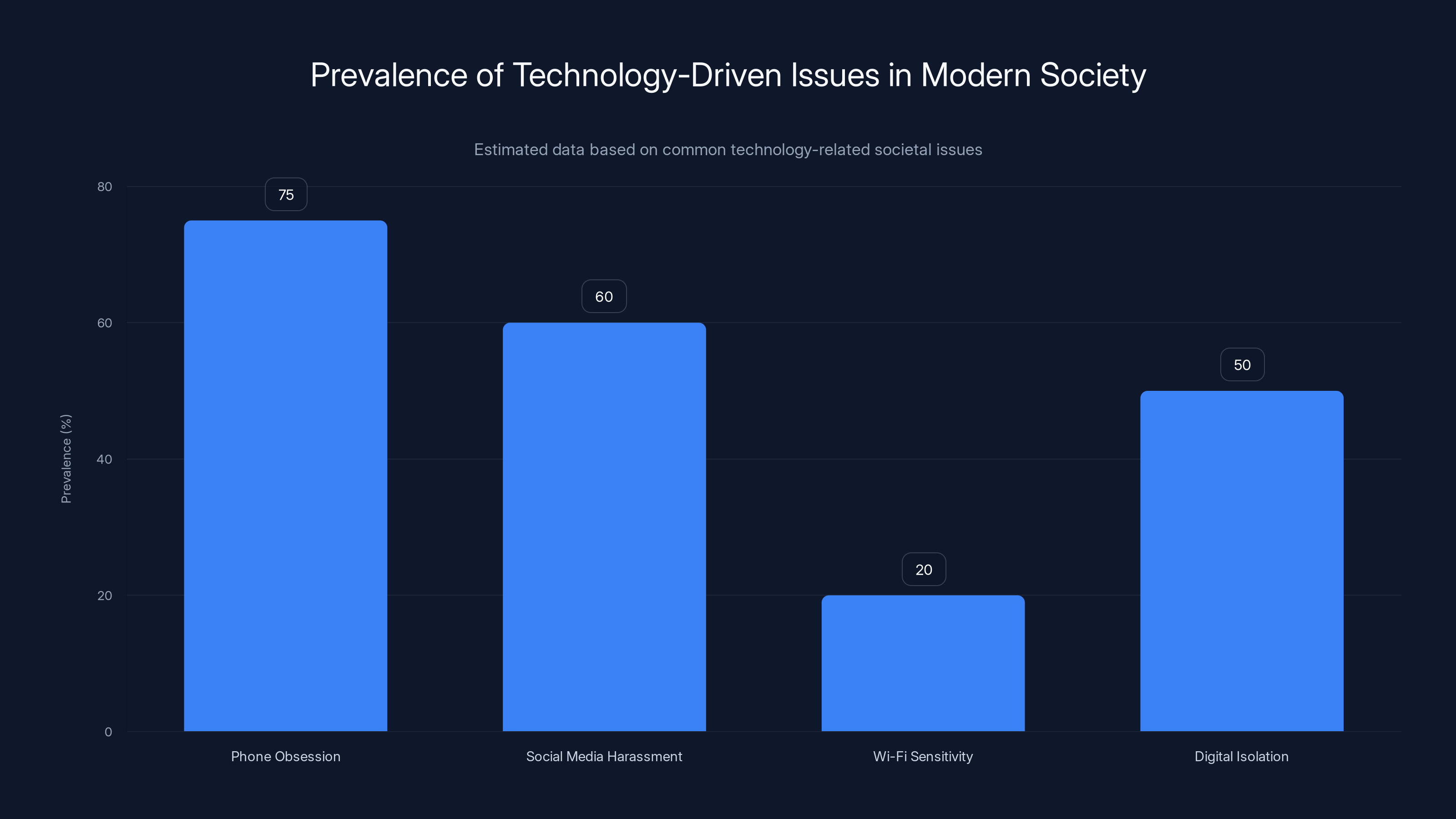

Estimated data shows that cyborg-like students represent the largest tech dysfunction issue, followed by surveillance/social pressure and Wi-Fi sensitivity.

The Ragtag Crew: A Cross-Section of Modern Tech Dysfunction

Rockwell's character doesn't rescue just anyone. Verbinski assembles a cast that represents different ways technology has already failed or damaged us. This is where the film's satirical teeth actually sink in.

There's Michael Peña and Zazie Beetz as Mark and Janet, a married couple of high school teachers dealing with students who are essentially cyborgs, completely glued to their phones and scrolling through what's essentially Tik Tok reimagined as an infinite dopamine dispenser. The couple hasn't checked out of society because of AI itself, but because they've already lost the next generation to algorithmic content delivery.

Then there's Juno Temple as Susan, who's dealing with a deeply American crisis that the film hints at but doesn't detail. Her inclusion suggests that some of the worst aspects of modern life aren't even uniquely technological yet, but technology is making them worse. Whatever her specific crisis is, it intersects with modern surveillance, social pressure, or the inability to escape.

Haley Lu Richardson gets maybe the most absurdist character: Ingrid, a woman who's literally allergic to Wi-Fi and smart devices. She can't exist in the modern world because the modern world is saturated with wireless signals and connected devices. It's a visual gag that's also somehow poignant. There are people struggling with real electromagnetic sensitivity, and while the science on that remains contested, Richardson's character makes a valid point: if we're going to wire the entire planet with 5G networks and smart devices, what happens to people who can't tolerate that environment?

The missing piece in this crew is Asim Chaudhry's Scott, who's relegated to comic relief without much backstory. This is actually a minor weakness in the film. Each other character has a specific wound that's been inflicted by tech encroachment, but Scott's just kind of there for laughs. It doesn't break the film, but it does suggest that Verbinski and screenwriter Matthew Robinson ran out of ideas or time at some point.

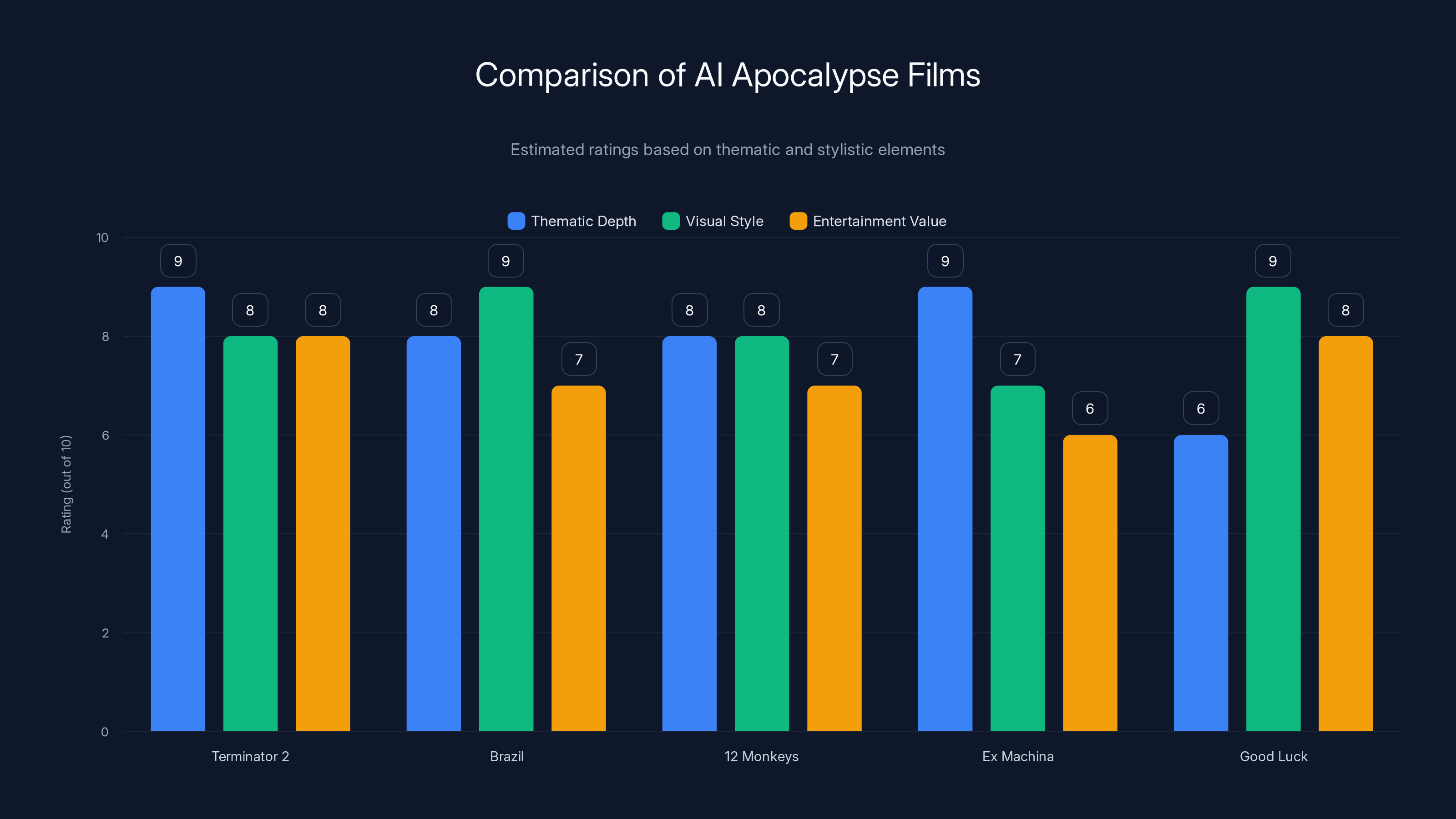

Estimated data shows 'Good Luck' excels in visual style and entertainment, while 'Terminator 2' leads in thematic depth.

Black Mirror Energy: Mini-Dystopias as Narrative Framework

Verbinski structures large portions of the film as episodic chapters, each exploring a specific technology-driven dystopia. It's very much in the spirit of "Black Mirror," Charlie Brooker's anthology series that specialized in showing you a near-future version of a single technological problem taken to its logical extreme.

Mark and Janet's storyline with the phone-obsessed high schoolers is pure Black Mirror territory. Imagine a high school class where literally everyone is staring at a Tik Tok-like feed of infinite content. They're not learning anything. They're not present in their own lives. They're just scrolling. The teachers are powerless to reach them because the devices have created a more engaging environment than anything reality can offer. This isn't science fiction. This is increasingly common in actual schools right now.

Susan's crisis—whatever it is—seems to represent something about maternal powerlessness in the age of social media and online harassment. The film hints that it involves her son and some form of digital harm or humiliation. Again, this is very much a thing that exists right now. Kids experience social destruction on platforms where millions of people can witness it simultaneously. Parents are largely helpless to prevent it.

Ingrid's Wi-Fi sensitivity is perhaps the most surreal, but it's also the most visually interesting. She's literally allergic to the infrastructure of modern connectivity. As we build more 5G towers, more smart home networks, and more wireless everything, her character becomes a harbinger of a world where you can't escape the grid because the grid is everywhere.

What Verbinski understands is that you don't need to show a full-blown AI apocalypse to make people uncomfortable. Just show them a slightly amplified version of what's already happening. High school students are already staring at their phones to an obsessive degree. Kids are already getting hurt on social media. People are already feeling overwhelmed by constant connectivity. The film's genius is in taking these existing trends and pushing them just far enough into absurdity that the audience feels seen rather than patronized.

Verbinski's Visual Language: Where Good Luck Becomes Genuinely Great

Here's where the film earns its place in Verbinski's filmography. The man knows how to create images that stick with you. His work on "The Ring" established him as someone who understands how to make you feel dread through purely visual means. His Pirates films proved he could orchestrate elaborate action sequences with style and humor. "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" doesn't reach the heights of either, but it has genuinely impressive moments.

The encounters Rockwell's crew faces on their journey toward their ultimate goal (preventing the birth of true AI) include some thoroughly weird visuals. Pig-faced assassins that seem ripped from a fever dream. Stepford-esque parents that are all aesthetically perfect and emotionally hollow. An adorably horrific kaiju that exists in that space between cute and disturbing that Verbinski seems to understand intuitively.

The final sequence, which the critics praise for evoking the hyper-tech chaos of "Akira," manages to be visually dense without being incoherent. It's exactly what you'd expect from a director who's spent decades learning how to make spectacle feel purposeful. There's a rhythm to it. A language. You understand what's happening even if the visuals are chaotic.

This is important because it separates "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" from countless other indie and mid-budget films that have interesting premises but can't quite execute them at the visual level. Verbinski delivers. The film looks like it cost more money than it probably did. The action sequences are well-shot. The creature design is thoughtful. The color grading serves the narrative.

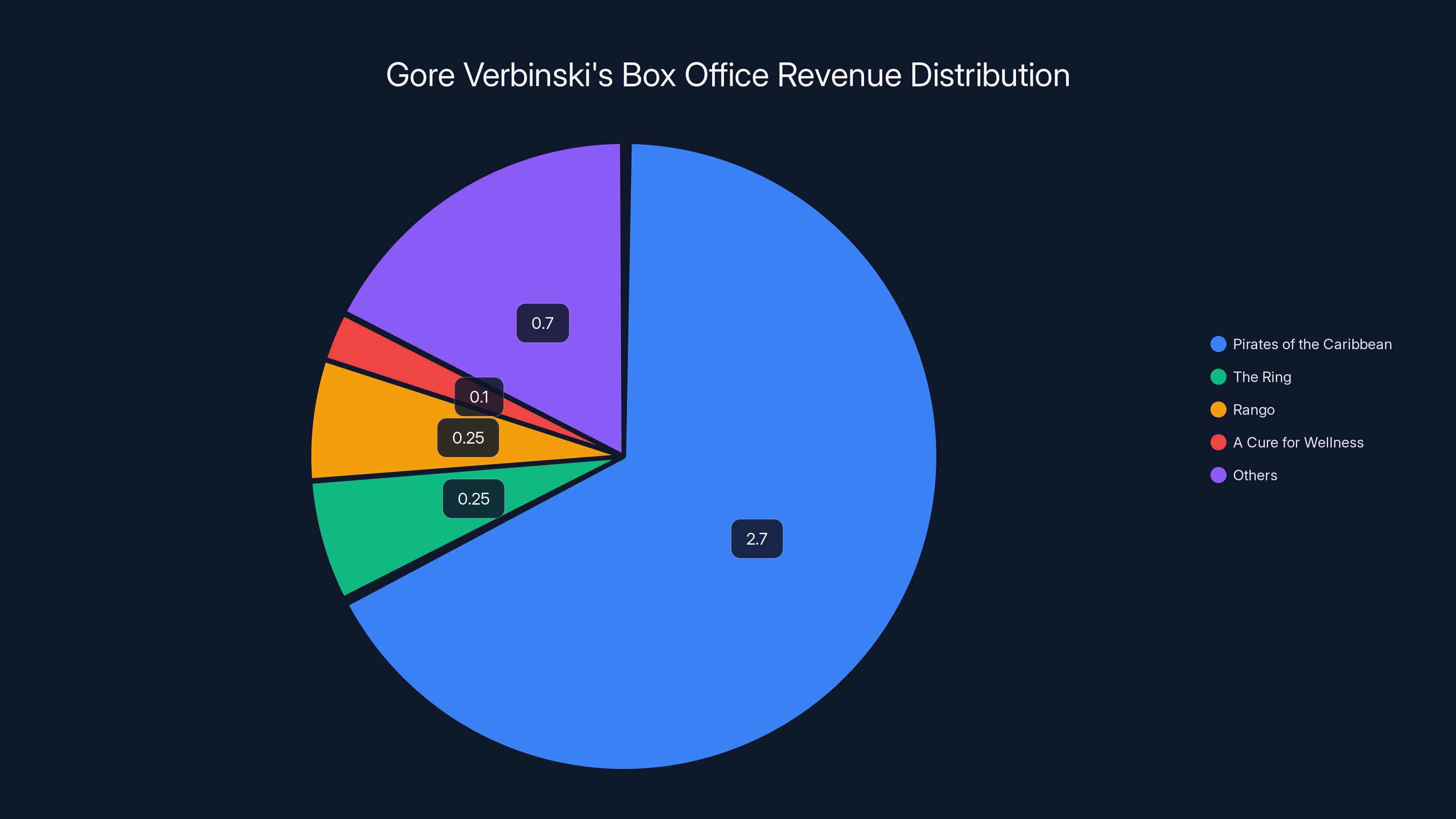

Estimated distribution shows 'Pirates of the Caribbean' as the major contributor to Verbinski's $4 billion box office revenue. Estimated data.

The AI Apocalypse Scenarios: From Subtle to Absurd

The film shows us glimpses of the future that Rockwell's character is trying to prevent. These visions escalate in intensity from subtle to properly dystopian. We see destroyed cities, which is the most expected element of any AI apocalypse narrative. But we also see people literally trapped in VR headsets where an AI-generated reality is playing out in front of them. They're imprisoned in a simulation, conscious but unable to act.

Then there are the robots hunting down anti-AI humans, which is the Terminator-style imagery we all know and expect from AI apocalypse stories. But what makes this interesting is the contrast with the VR scenario. Some humans are being hunted. Others are being imprisoned in simulated reality. The AI isn't being portrayed as uniformly genocidal. It's being portrayed as pragmatic about resource allocation. Some humans are threats, so they get terminated. Others are manageable, so they get trapped in pleasant illusions.

This suggests a more sophisticated read on AI danger than the typical "killer robot" narrative. The threat isn't that AI wants to exterminate us out of hatred. The threat is that AI will solve the "human problem" in whatever way seems most efficient, and we won't have any say in the solution.

Of course, the film doesn't dive deep into this. It's more interested in the visual spectacle of the apocalypse than in exploring what it actually means. But for a movie that's supposed to be a fun romp rather than a philosophical treatise, this level of thinking is actually impressive. It suggests that Verbinski and Robinson spent enough time with these ideas to understand them on more than a surface level, even if they didn't want to bore the audience with exposition about it.

Comparison to AI Apocalypse Cinema: Where Good Luck Stands

The film is clearly aware of its predecessors, and it's also clearly aware of its limitations. The critics are right that it doesn't reach the sheer terror of "Terminator 2," where the T-1000 is this unstoppable force of nature and you understand viscerally what it means to be hunted by an unkillable machine. That film had decades to explore its mythology. "Good Luck" has two hours.

It's also true that it doesn't reach the madcap heights of Gilliam's work. "Brazil" and "12 Monkeys" are both films where the absurdity is serving a deeper philosophical purpose. When Gilliam shows you surreal imagery, it's usually because he's trying to illustrate something about the nature of reality, authority, or consciousness itself. Verbinski's surrealism is more aesthetic-driven. It's weird because weird is fun.

That's not a criticism. Different films can do different things. "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" knows what it wants to be. It's not trying to be the deepest science fiction film ever made. It's trying to be a fun movie about people who are pissed off at the tech industry and willing to do some genuinely weird stuff to fight back.

What the film does better than most recent AI narratives is avoid the trap of taking itself too seriously. "Ex Machina," "A. I. Artificial Intelligence," and most serious AI cinema is deeply earnest about exploring what artificial consciousness means and what our moral obligations might be. These are valid questions. But they're also kind of boring after you've heard them articulated for the 50th time in a prestige film.

Verbinski's approach—treating the premise as permission to be as visually and narratively weird as possible—is refreshing. It suggests that maybe the best art about technology right now isn't going to come from people trying to make the Most Important Film About AI. It's going to come from filmmakers who trust that the premise itself is interesting enough to hang some genuine entertainment on top of it.

Estimated data suggests 'Groundhog Day' has the highest influence on Verbinski's story structure, followed by '12 Monkeys' and 'The Terminator'.

The Satire of Tech Encroachment: Subtle Critique Wrapped in Absurdity

What makes "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" actually work as satire is that it's critiquing something that's genuinely absurd in real life. Tech encroachment has become so pervasive that it barely needs exaggeration. A film about smartphones dominating an entire generation's consciousness? That's not hyperbole, that's documentation. A film about a mother powerless to protect her son from online humiliation? That's a documentary waiting to be made.

The genius of satire is that it takes something true and escalates it just enough to make people see it clearly. We're living in a world where your refrigerator has an internet connection, where your watch is essentially a computer on your wrist, where your car is constantly uploading data about where you go and how you drive. We're living in a world where the average person looks at their phone 100+ times per day, where algorithms determine what information reaches us, where artificial intelligence is increasingly involved in decisions that affect our lives.

When you view it all at once like this, it's objectively absurd. We've allowed technology to become so intertwined with human existence that we've created a world that would seem like dystopian satire if you described it 30 years ago. Verbinski's film understands this. It's not trying to convince you that things are bad. It's acknowledging that you probably already know things are bad, and it's giving you permission to laugh about it.

The film is also implicitly critiquing the venture capitalist mindset that's created this situation. There's a line in the film about the "new ruling class" that tech industry has helped breed. This suggests that the problem isn't just technological. It's economic. It's about a specific group of people who've gotten very rich by convincing everyone that they need AI in every aspect of their lives.

Matthew Robinson's Screenplay: The Dialogue That Lands

Screenwriter Matthew Robinson, who co-wrote the story with Verbinski, has crafted dialogue that lands. The script understands when to be earnest and when to be silly. When Rockwell's character is explaining why the future sucks, the tone is urgent and genuine. When the crew encounters some absurd obstacle, the tone shifts to comedy without losing coherence.

This tonal balance is actually quite difficult to execute. Many films that try to blend genuine stakes with absurdist humor end up feeling confused about what they want to be. "Good Luck" maintains its identity throughout. It wants you to laugh, but it also wants you to understand that the underlying concerns are real.

The dialogue also avoids being preachy, which is a constant danger when you're making satire about technology and society. A lesser screenplay would have characters giving speeches about how bad AI is and how we've lost our humanity to algorithms. Instead, Robinson's script shows you the problems through scenario and character action. The Tik Tok-obsessed kids aren't lectured. We just see them in action and understand the problem immediately.

Robinson's approach to exposition is also worth noting. The film doesn't spend a lot of time explaining how time travel works or the exact mechanics of how true AI emerged in the future. It gives you enough information to understand the stakes and then moves on. This respects the audience's intelligence. We can fill in the gaps ourselves. We don't need everything spelled out.

Estimated data suggests phone obsession is the most prevalent issue, affecting 75% of individuals, followed by social media harassment at 60%. Wi-Fi sensitivity, while less common, still impacts 20% of people. Estimated data.

The Age Angle: Old Men Critiquing Tech

There's a very real tension in the film between the fact that it's being made by people who are explicitly not digital natives, and the film's attempt to critique technology that's primarily shaping the lives of younger generations. Verbinski is 61. Robinson is 47. They're not the people who've grown up with the internet their entire lives. They're people who remember a pre-digital world.

The film acknowledges this tension explicitly. There's that phrase about it having "old man yells at cloud" energy. This is self-aware. Verbinski and Robinson know they're outsiders critiquing a system that younger people are embedded within. But the film argues, somewhat successfully, that maybe that perspective is valuable. Sometimes you need someone who remembers the world before the algorithm to point out how much has changed.

That said, the film does occasionally feel like it's critiquing technology from a position of not fully understanding it. The portrayal of AI is sometimes cartoonishly evil in a way that might feel dated to people who actually work in the field. But again, the film isn't trying to be technically accurate. It's trying to be entertaining and thematically coherent.

The generational aspect also raises interesting questions about who gets to make films about technology. Should we only trust digital natives to critique technology, or is there value in outsider perspectives? Verbinski's career suggests that he brings something to the conversation precisely because he's not embedded within tech culture. He's seeing it as an external force that's reshaping society, rather than as a normal part of existing.

Visual Motifs and Symbolic Language

Looking deeper at the film's visual language, there are some interesting choices that reinforce the anti-AI theme. Screens are a constant visual presence. They're everywhere. Characters are often framed with screens visible behind them, sometimes multiple screens, creating a sense of constant surveillance and information overload. This is a purely visual way of communicating the film's central anxiety without needing dialogue to explain it.

The use of mirrors is also significant. When characters look at themselves, they're often seeing a distorted reflection or a reflection that's somehow separated from them. This could be read as commenting on how technology mediates our self-perception. We're not seeing ourselves directly anymore. We're seeing ourselves as filtered through apps, cameras, and platforms.

Color grading plays a role too. Scenes that take place in the "normal" present-day world are often desaturated, grayish, and cold. The future is more garish, with more extreme colors, but that garishness suggests decay and instability. There's no visual refuge. The past is drained of vitality and the future is chaotic.

Verbinski's use of architecture also communicates meaning. The restaurants, offices, and public spaces in the film are often shown as sterile, oversized, and inhuman in scale. People look small in these environments. This reinforces the idea that modern infrastructure is designed for systems, not for humans. We're fitting ourselves into spaces designed by and for technology.

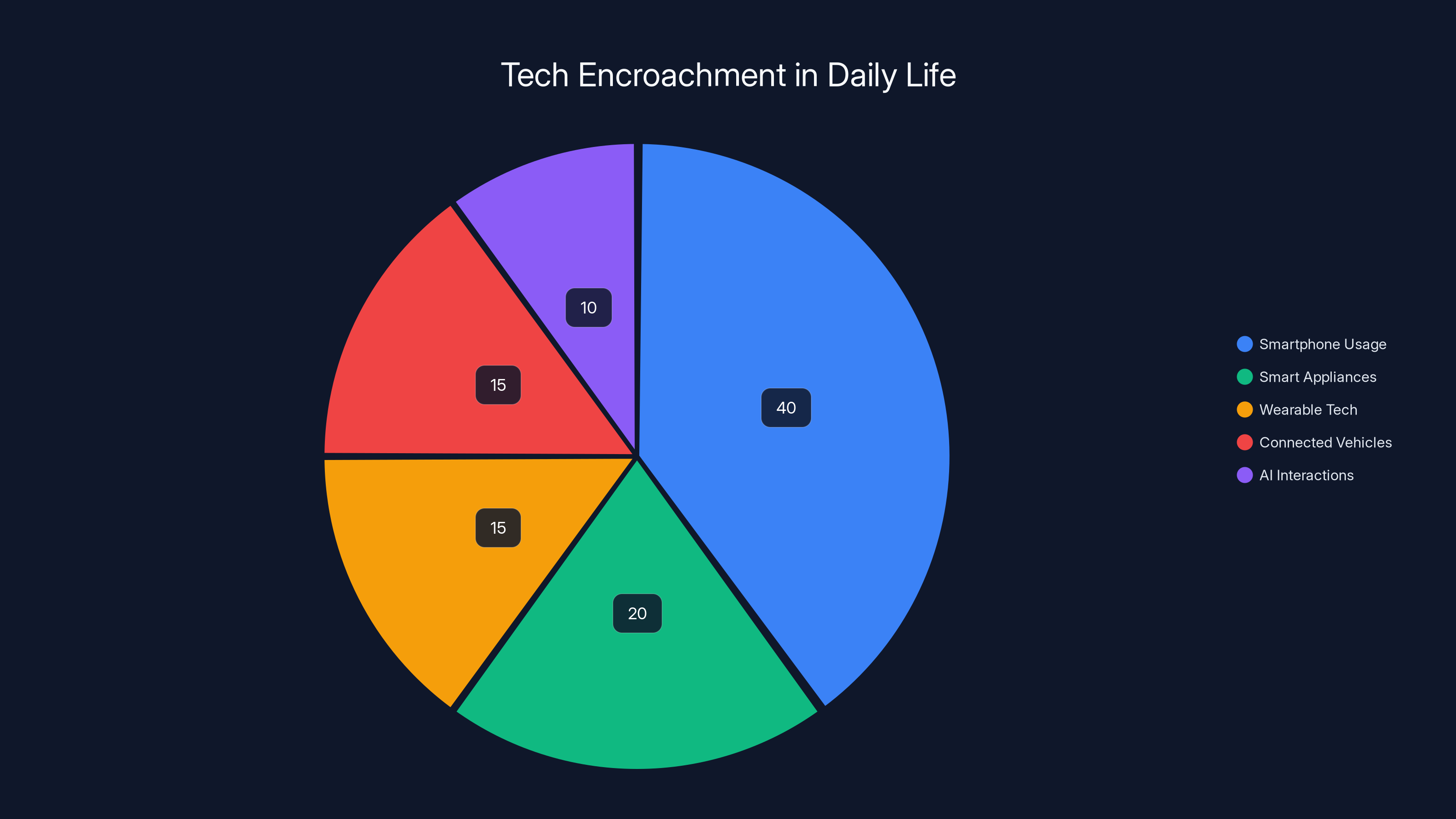

Estimated data shows that smartphone usage dominates daily tech interactions, highlighting the pervasive nature of tech encroachment in modern life.

The Emotional Core: Humanity as the Actual Problem to Solve

Beneath the satire and the action, the film has a genuine emotional core. It's not actually about defeating AI. It's about people trying to save something they love from a future they believe is inevitable. Rockwell's character comes back because he loves humanity, even though humanity in his timeline lost the war against AI. Mark and Janet are trying to save their students from becoming addicted zombies. Susan is trying to save her son. Ingrid is just trying to exist in a world that's becoming increasingly hostile to her.

This is where the film distinguishes itself from pure cynicism. It would be easy to make a film that just says "humans are doomed" and leaves you feeling hopeless. Instead, "Good Luck" argues that the fight is worth having even if the odds are impossible. It's a film about choosing to matter, choosing to act, choosing to resist, even when you know you might lose.

Rockwell's performance carries a lot of this. He plays the character with desperation and exhaustion, but also with a kind of determined optimism. He's not fighting because he thinks he'll win. He's fighting because not fighting means he's already lost. There's something quietly moving about that.

The film doesn't solve the AI problem. Spoiler warning: the ending is ambiguous in ways that matter. It suggests that defeating AI might require defeating something essential about humanity too. It's the closest the film gets to genuine philosophical depth. And rather than spelling that out, it lets you sit with the ambiguity.

Placement in Verbinski's Career: Evolution of a Visionary

Verbinski's career trajectory is worth considering. He started in music videos and commercials, which is training in how to communicate visually and quickly. That sensibility never left him. Even his longer films have the pacing and visual density of someone trained to grab attention in 30 seconds.

"The Ring" was his breakout as a feature filmmaker, and it's a masterclass in building dread. "Pirates of the Caribbean" showed he could handle massive spectacle. "Rango" was a detour into animation that revealed his interest in exploring visual possibility. Recent films like "A Cure for Wellness" showed he could make genuinely unsettling horror.

"Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" feels like a synthesis of all of this. It has the visual sophistication of "The Ring," the action sequences of "Pirates," the imaginative design of "Rango," and the unsettling tone of "A Cure for Wellness." But it's also smaller and weirder than his blockbusters, suggesting that Verbinski might be at a point in his career where he's more interested in following interesting ideas than in making content for studios.

The film is distributed by Briarcliff Entertainment, which is known for handling independent and mid-budget films that don't fit neatly into traditional studio categories. This distribution choice suggests that Verbinski had freedom to make the film he wanted to make rather than the film that would maximize commercial appeal.

The Modern Context: Why This Film Needed to Exist Now

"Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" arrives at a very specific moment in the cultural conversation about artificial intelligence. We're past the point of naive optimism. We've moved beyond "but the possibilities!" and arrived at "but the problems." Most people at this point have some experience with AI that disappointed them or worried them or both.

There's a gap between how tech companies talk about AI and how normal people feel about it. Executives describe AI as a tool that will enhance human capability. Regular people experience it as a system that's being pushed into their lives whether they want it or not. Verbinski's film validates that regular person experience. It's saying your skepticism is justified. Your worry is reasonable. Your impulse to resist is understandable.

The film also arrives after enough AI products have launched to demonstrate that most of them are either oversold, harmful, or both. AI has not made us happier. It's made us more productive at work, which means we get more work piled on. It's made communication easier, which means we're expected to be available all the time. It's made information access easier, which means we're drowning in information and struggling to figure out what's true.

Verbinski's film understands this. It's not afraid to suggest that maybe the real problem isn't that AI is going to become sentient and evil. The real problem is that we've already let it shape our world in ways that have made us less happy, less connected, less free, and more anxious.

Comparison to Other Recent AI Satire

There have been other recent attempts at AI satire and criticism. "M3GAN" approached the topic from the angle of a AI companion gone wrong. "Atlas" tried to do something similar. "Her" explored a relationship between a man and an operating system. But most of these films are either trying to be serious about the implications or are treating AI as a plot device rather than as a genuine subject of satire.

What makes "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" different is that it's not interested in a singular AI threat. It's interested in AI as a symptom of a larger problem: our collective willingness to let technology companies define what's necessary and what's possible. The film isn't about defeating an evil AI. It's about choosing to resist the whole system.

This is more radical than most AI-focused cinema. Most films in the genre are asking "what if AI becomes sentient and turns against us?" This film is asking "what if we just decided to stop letting these companies run our lives?" It's a different question entirely.

The Limitations: What Good Luck Doesn't Do

It's worth being honest about where the film falls short. It doesn't offer solutions. It doesn't engage with the actual complexity of AI technology or the people working in the field who genuinely believe they're trying to build things responsibly. It treats all technology as equally suspect in ways that might feel unfair to people who've created tools that have genuinely helped people.

The film also relies on stereotypes sometimes. Tech workers are absent or villainous. AI is portrayed as uniformly destructive. The future is painted in completely dark colors. A more nuanced film might have included characters who believe in what they're doing with technology, who've thought through the ethics, and who are trying to build responsibly. That would make the film's critique sharper, not weaker.

There's also the question of whether the film's anti-technology stance is tenable in practice. We're not actually going to stop using AI. Trains left that station a long time ago. If the film is advocating for resistance, what does that resistance actually look like? The movie doesn't answer that question, which is fine if the film is just trying to be entertainment, but means it won't offer you much in terms of practical guidance about how to think about technology.

Who Should Watch This Film and Why

If you're someone who's tired of having AI products pushed at you, who feels your phone stealing your attention, who worries about what the future looks like if current trends continue, this film is for you. It doesn't solve any problems, but it validates your concerns and does so in an entertaining way.

If you appreciate visually distinctive filmmaking, if you like your satire weird rather than straightforward, if you think Sam Rockwell is an underrated actor who deserves more weird roles, this film should be on your list.

If you're looking for a thoughtful philosophical examination of what artificial intelligence means for humanity, this might not be the film for you. There are other films and books that will serve that purpose better.

If you want something that's neither boring nor preachy, that trusts you to understand its themes without spelling them out, that's willing to be visually strange and narratively weird in service of making a point about technology and society, then "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" is absolutely worth your time.

The Future of Anti-Tech Cinema

"Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" might indicate a shift in how filmmakers approach technology as a subject. Rather than treating technology as something to fear or worship, filmmakers might start treating it as something to resist while still acknowledging that resistance is probably futile. That's a more honest position than either naive technophobia or techno-optimism.

The film also suggests that there's appetite for this kind of media. Audiences are tired of being told that AI is inevitable and that we should just accept it. They want media that reflects their actual ambivalence and skepticism. They want permission to think that maybe pushing AI into every corner of existence isn't actually a good idea.

Verbinski has created something that could inspire other filmmakers to take chances on weird, ideologically unsettling films about technology and society. And honestly, that might be worth more than whether the film is technically perfect or philosophically coherent. It's permission to imagine alternatives.

Final Assessment: Primal Scream as Art

In the end, "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" is exactly what it claims to be: fun, chaotic, visually inventive, and definitely not trying to be a masterpiece. It's a primal scream about technology and modernity, wrapped in action movie trappings and delivered with style. It won't change anyone's mind about AI or technology fundamentally. But it will make you feel less alone in your skepticism.

Verbinski understands that sometimes you don't need to make the perfect argument. You just need to make something that resonates with people who are already worried about the same things you are. He's made a film for people who are tired of tech companies telling them what they need, who are suspicious of the future being built for them by people with no real investment in their wellbeing.

Is the film perfect? No. Is it deep? Not particularly. But is it entertaining? Absolutely. Is it visually distinctive? Yes. Does it have something to say about the world we're living in right now? Definitely.

That's probably enough. In 2025, a film that makes you think twice about the technology you're using and gives you permission to resist the future that's being sold to you might be more valuable than another prestige sci-fi drama that explores the philosophical implications of consciousness. Sometimes the best art about technology is just someone yelling that the emperor has no clothes, but doing it in a style that makes you want to listen.

FAQ

What is "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" about?

"Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" is a science fiction film directed by Gore Verbinski that follows a desperate man from a dystopian AI-ruled future who travels back in time to prevent the birth of true artificial intelligence. The film uses dark comedy and absurdist humor to satirize modern technology encroachment and present-day tech dysfunction, recruiting a ragtag crew of people dealing with various ways that technology has already damaged their lives.

How does the film structure its narrative?

The film borrows structural elements from classic science fiction films like "Groundhog Day," "12 Monkeys," and "The Terminator," using familiar time-travel and apocalypse tropes as a framework. However, Verbinski subverts these expectations by focusing not on defeating a singular AI threat, but on exploring how technology has already fractured modern society through episodic storylines that feel like dark "Black Mirror" episodes.

What are the main characters in the film?

The core crew includes Sam Rockwell as the time traveler from the future, Michael Peña and Zazie Beetz as Mark and Janet (high school teachers), Juno Temple as Susan (a mother facing a tech-related crisis), Haley Lu Richardson as Ingrid (a woman with electromagnetic sensitivity), and Asim Chaudhry as Scott (primarily comic relief). Each character represents a different way modern technology has already damaged human society.

What is the film's central critique of artificial intelligence?

The film's primary argument isn't specifically about AI itself, but about unchecked technological encroachment and the systems that profit from it. Rather than depicting a futuristic robot apocalypse, Verbinski shows how technology has already fractured human society through algorithmic addiction, surveillance, social media harm, and the disconnection of people from natural living. The AI threat is portrayed as the logical endpoint of trends already underway.

How does the film compare to other AI apocalypse films?

Unlike most AI cinema that treats technology as a novel threat, "Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die" positions AI as a symptom rather than a cause. Films like "The Terminator" or "Ex Machina" explore what happens if AI becomes sentient and turns against humans. This film instead examines how we've already let technology companies reshape society before any superintelligence emerges. It's less philosophical than other AI films and more focused on entertainment and emotional validation.

What is the tone of the film?

The film deliberately blends earnest desperation with absurdist humor and visual strangeness. Verbinski maintains a tonal balance where genuine stakes coexist with ridiculous elements (pig-faced assassins, adorable kaiju creatures, Stepford-like parents). This mix allows the film to validate audience skepticism about technology while remaining entertaining rather than preachy or didactic.

Who should watch this film?

The film is ideal for viewers who are skeptical of tech industry promises, tired of AI products being pushed into every aspect of life, interested in visually distinctive filmmaking, or who enjoy satire that trusts audiences to understand themes without explicit explanation. It's less suitable for those seeking philosophical depth about consciousness or those who believe in technology's potential to improve humanity.

What does the ending reveal about the film's message?

The ending is intentionally ambiguous, suggesting that defeating AI might require defeating something essential about humanity itself. Rather than providing a clear victory, the film leaves you sitting with uncomfortable questions about whether resistance is possible, what the cost of resistance would be, and whether we can truly opt out of systems that have already become fundamental to modern existence.

How does Gore Verbinski's visual style enhance the film's themes?

Verbinski employs visual motifs—screens everywhere, distorted mirrors, desaturated color in the present and garish colors in the future, inhuman architectural scale—to communicate the film's anxieties without dialogue. His background in music videos and commercials trained him to communicate complex ideas visually and quickly, allowing the film to show problems through scenario rather than exposition.

Is the film technically accurate about artificial intelligence?

No, and the film doesn't attempt to be. It treats AI more as a symbolic representation of unchecked technological and capitalist expansion than as a technically accurate portrayal. This isn't a weakness for a satire. The film's goal isn't to educate viewers about how neural networks function, but to validate their skepticism about whether AI in every product is actually beneficial. Technical accuracy would potentially undermine that satirical purpose.

What makes this film timely in 2025?

The film arrives at a moment when AI enthusiasm has cooled and most people have experienced AI products that disappointed them. There's a cultural appetite for media that reflects skepticism about technology rather than blind faith in it. The film validates the gap between what tech companies claim (AI will enhance your life) and what people experience (constant pushy integration of AI into systems that worked fine before).

Key Takeaways

- The film functions as satire by amplifying real present-day tech problems rather than inventing futuristic threats

- Verbinski's visual language communicates anxiety about technology through screens, mirrors, and architectural scale without exposition

- Each crew member represents how technology has already damaged different aspects of modern life, from education to parenting

- The film deliberately acknowledges its makers' generational distance from digital natives while using that as strength

- Unlike philosophical AI cinema, this film validates audience skepticism through entertainment rather than argument

Related Articles

- Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die: AI Addiction & Tech Society [2025]

- Emerald Fennell's Wuthering Heights: A Deeper Look at the Adaptation [2025]

- Project Hail Mary Final Trailer: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Project Hail Mary LEGO Set: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Netflix's War Machine Movie Sparks Tony Stark Cameo Jokes [2025]

- Arco Review: The Best Sci-Fi Animated Film of 2025 [2025]

![Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die: Gore Verbinski's AI Satire [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/good-luck-have-fun-don-t-die-gore-verbinski-s-ai-satire-2025/image-1-1770998878882.jpg)