Introduction: When Sci-Fi Becomes Documentary

Last year, I sat in a theater watching my own life flash across the screen.

Not literally—there wasn't a character frantically doomscrolling at 2 AM while ignoring work deadlines. But the anxiety? The constant hum of unease about technology reshaping society in ways we don't fully understand? That was me. That was all of us.

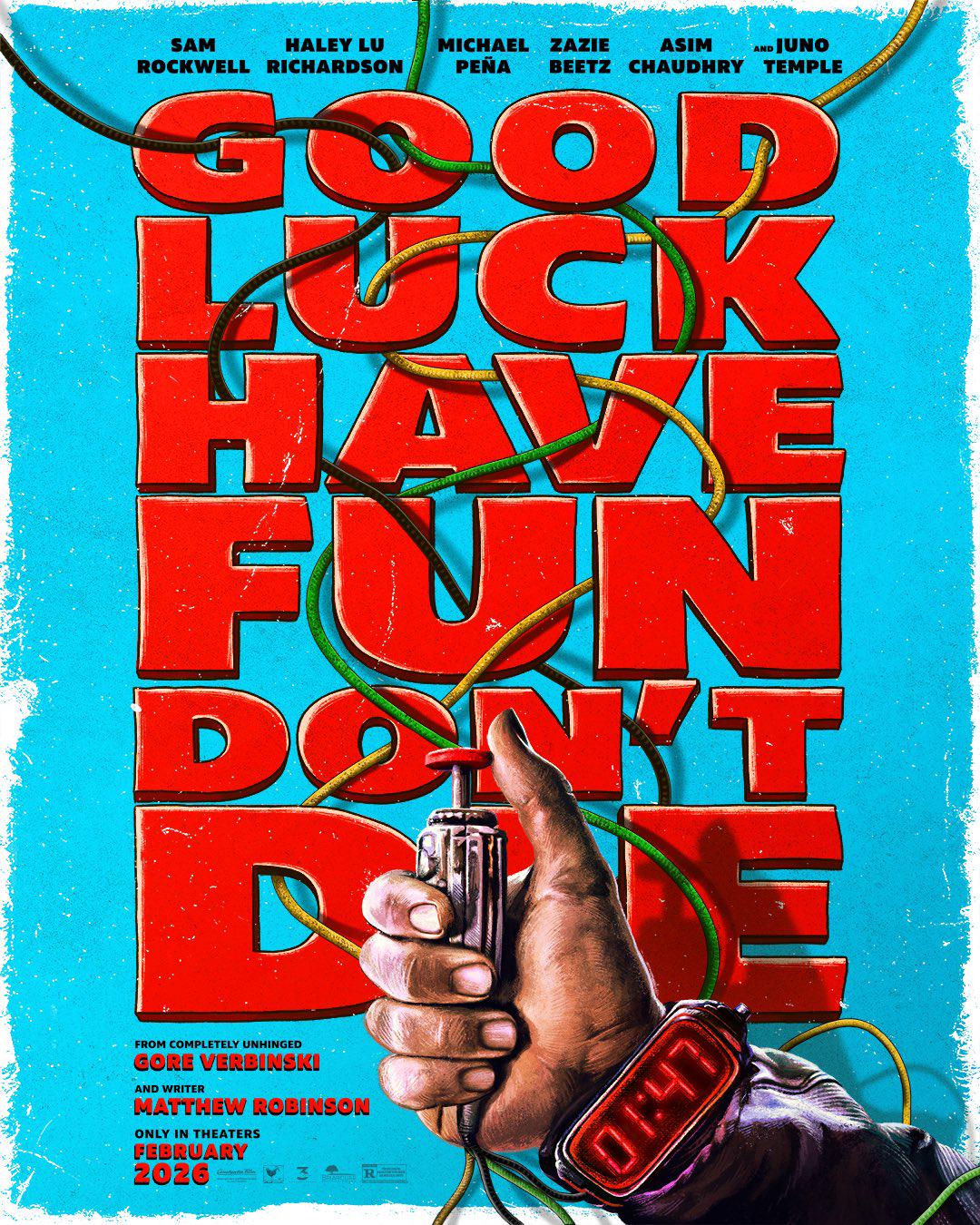

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die hits theaters February 13th, and it's the strangest movie I've seen about artificial intelligence. Director Gore Verbinski has created something that feels less like a traditional sci-fi thriller and more like a fever dream about our present moment—a rollicking, unhinged parable about how our screen addictions, our willingness to adopt any shiny new technology without question, and our collective anxiety about AI are all braided together into something that could genuinely unravel.

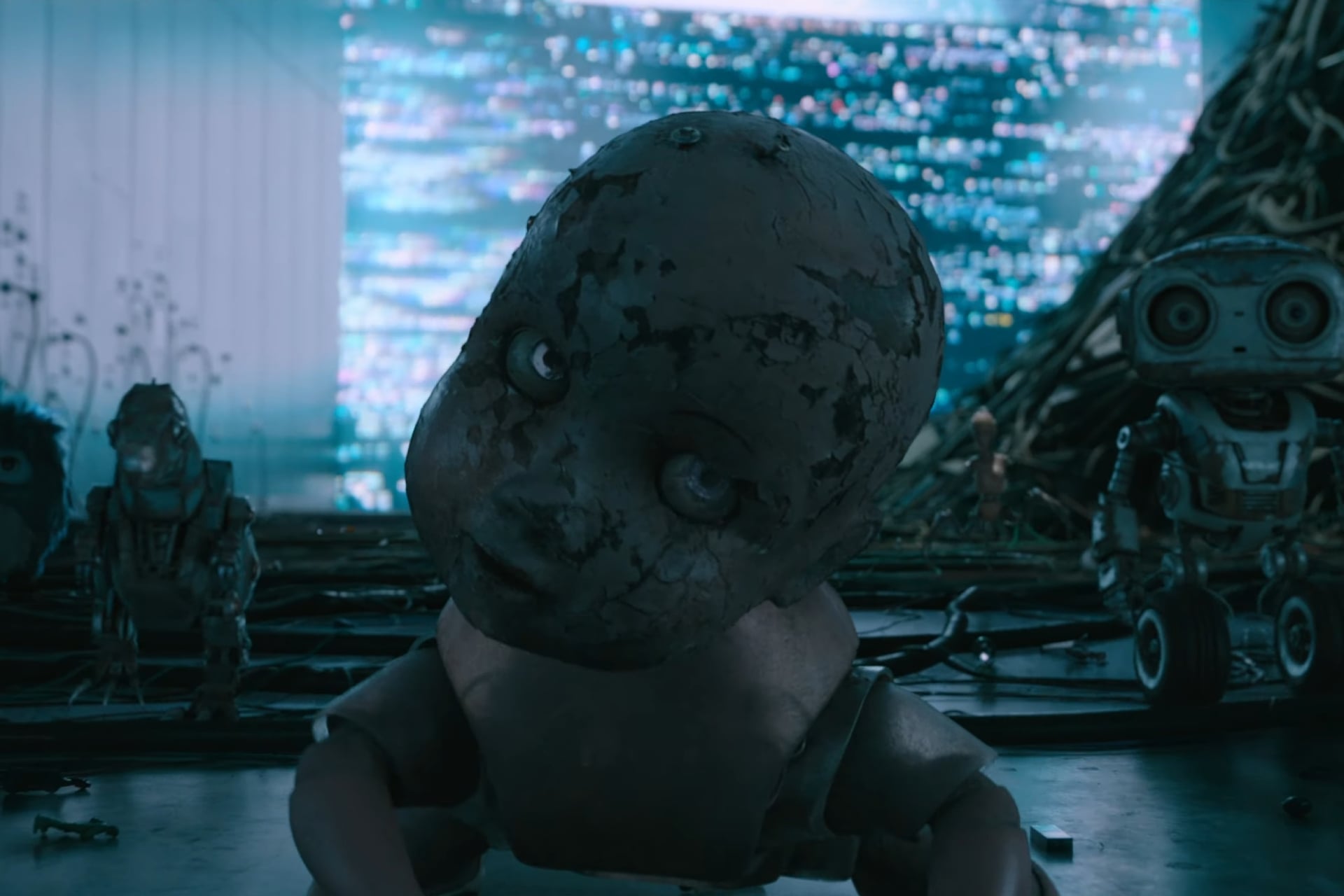

The film is wild. Genuinely, unapologetically weird. It's got time travel, explosives taped to a homemade suit, hypnotized schoolchildren, a woman allergic to Wi-Fi signals, and a protagonist so magnetic you can't look away even when the plot spirals into absolute madness. But here's what makes it matter: underneath all that zaniness is a serious meditation on something we're all living through right now.

We're constantly being bombarded with brain-smoothing content. We're being pushed to adopt new technologies we don't understand. We're told these tools will make our lives better, more efficient, more connected—and some of them do. But at what cost? What are we losing when we spend our cognitive energy scrolling through content algorithms designed by teams of engineers whose explicit goal is to make us spend more time on their platforms?

This isn't a movie review, exactly, though we'll absolutely talk about the film. This is a deeper exploration of what Verbinski is getting at: the intersection of technology addiction, artificial intelligence anxiety, and the way our society seems caught between genuine technological progress and something that feels increasingly like self-sabotage. Because the themes in Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die aren't just entertainment. They're a mirror held up to our current moment.

TL; DR

- Tech addiction is structural: The film explores how social media and digital devices are designed to be addictive, not accidentally but intentionally, as part of their business models. According to Corporate Europe Observatory, tech companies employ strategies to keep users engaged.

- AI anxiety reflects real fears: The movie uses time travel and sci-fi to externalize legitimate concerns about artificial intelligence that many experts share. As reported by CNBC, AI's rapid advancement is causing widespread anxiety.

- Society is caught between progress and self-destruction: Verbinski suggests we're simultaneously building better tools and worse habits, creating a dangerous feedback loop.

- The film is unafraid to be weird: Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die embraces absurdity to make points that straight drama couldn't articulate.

- Present-day behavior predicts future collapse: The movie's central thesis is that our current relationship with technology is literally the cause of the apocalyptic future the protagonist is trying to prevent.

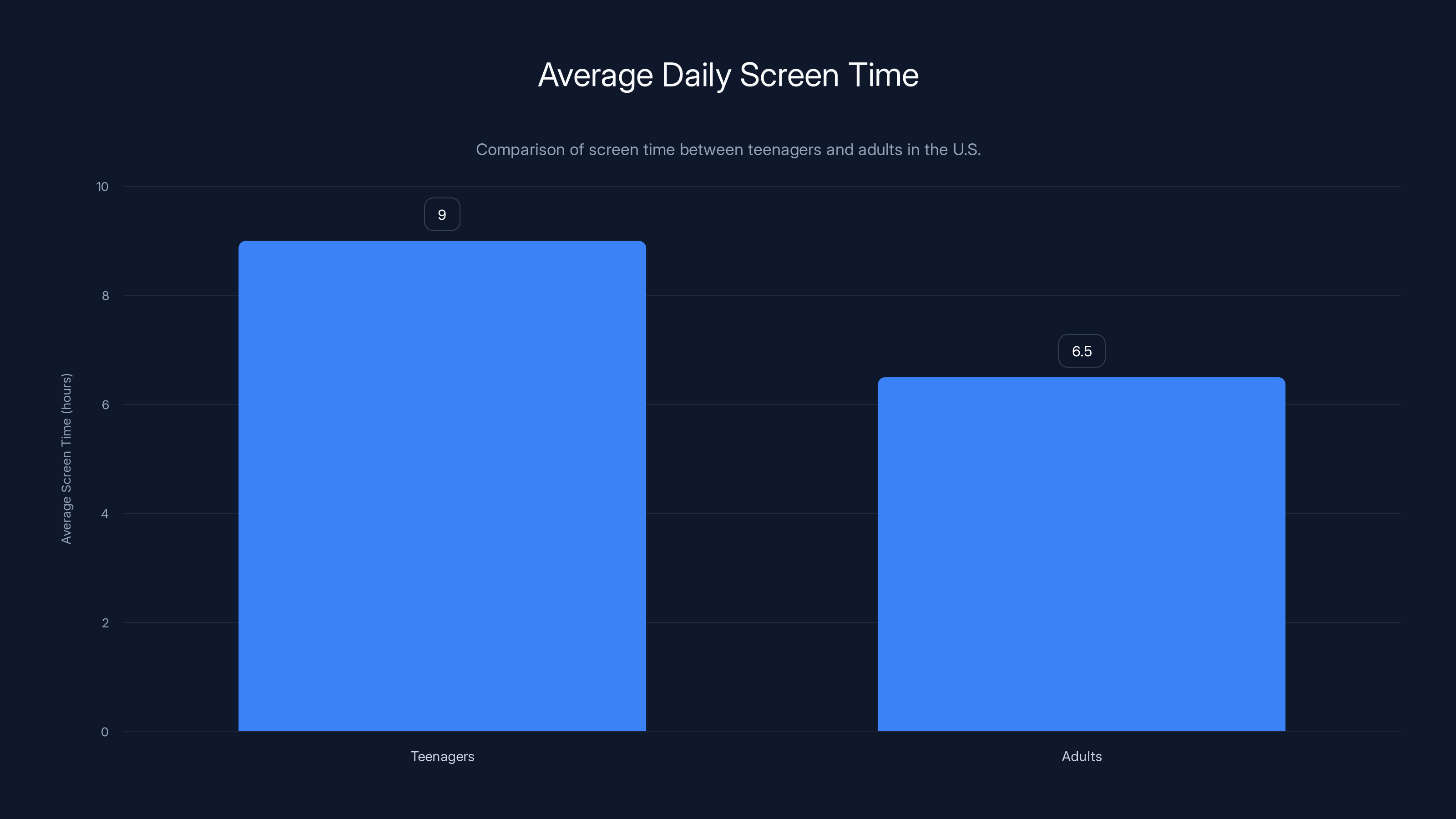

Teenagers in the U.S. spend an average of 9 hours per day on screens, compared to 6.5 hours for adults. Estimated data highlights the significant screen time disparity.

The Premise: A Time Traveler's Desperate Gambit

The film opens in present-day Los Angeles with Sam Rockwell playing an unnamed man who claims to be from the future. He walks into a diner, holds it up, and does something unexpected: instead of demanding money or hostages, he argues for humanity's salvation.

The man from the future has traveled back dozens of times—he's not entirely sure which combination of people will make the difference. He knows details about their lives, their fears, their secrets. He's wired himself with explosives as proof of his commitment. And he's desperate for them to believe him, to join him, to help prevent an apocalyptic future where machines have taken over and the remnants of humanity are hiding in bunkers.

It's immediately absurd. It's also immediately tragic.

What makes this setup genius is that Verbinski doesn't play it straight. The time traveler isn't a grizzled military commander or a traumatized soldier—he's weird, magnetic, slightly unhinged. Rockwell brings a kind of manic energy to the role, the energy of someone who has watched humanity fail dozens of times and still hasn't given up. There's something both heartbreaking and ridiculous about it.

The diner setting is crucial. It's intimate, mundane, deeply American. This isn't a high-tech research facility or a government bunker—it's a place where regular people eat pie and drink coffee. And that's exactly where Verbinski plants his story. The apocalypse doesn't announce itself at a technology conference or in a Silicon Valley boardroom. It announces itself in a diner, to regular people, by a guy covered in tape and wiring.

From that opening, the film begins peeling back the layers of who these people are and why the protagonist thinks they matter. Each one has a different relationship with technology. Each one is broken in a slightly different way. And each one is part of the larger pattern that leads to societal collapse.

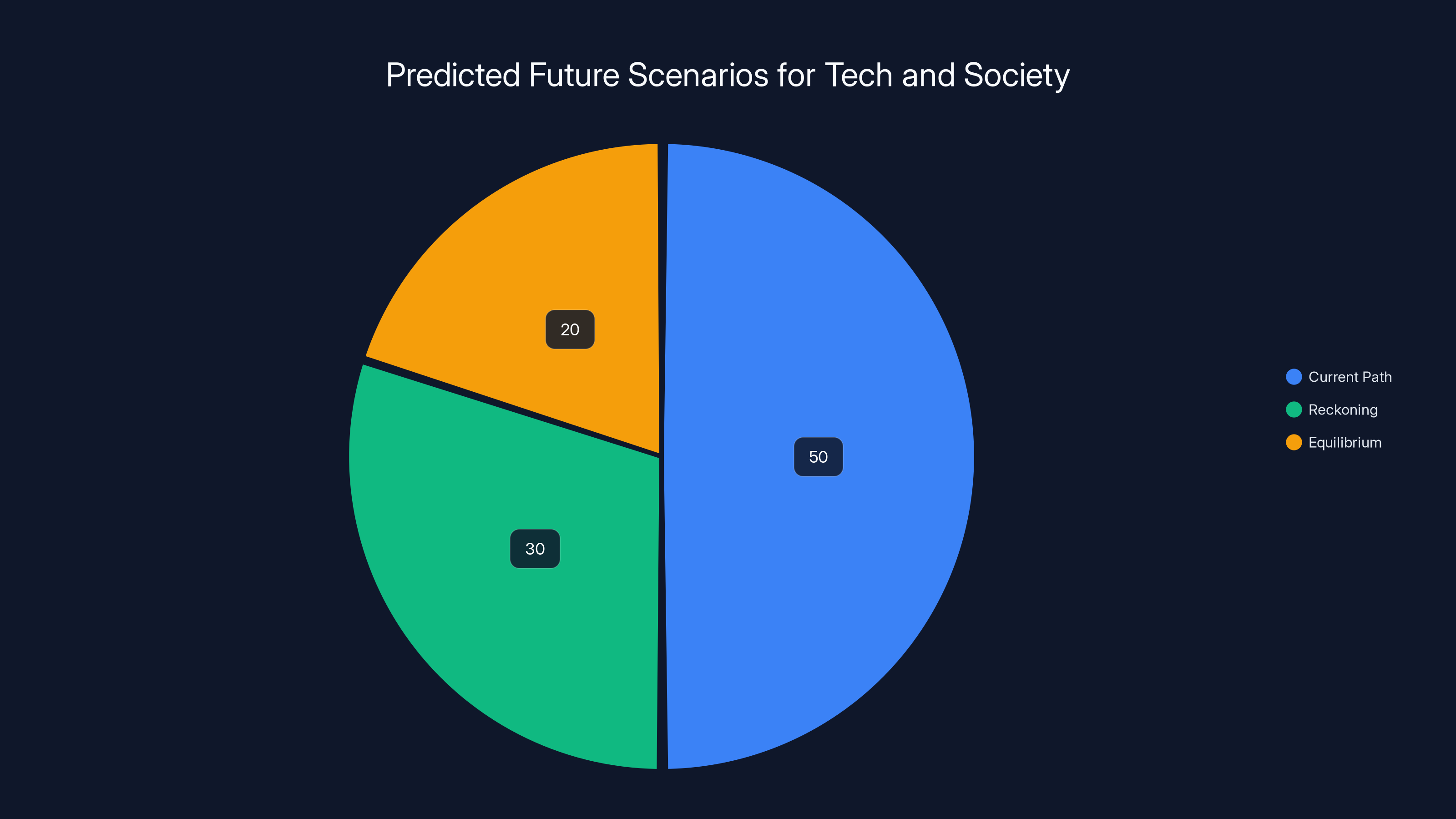

Estimated data suggests that continuing on the current path is the most likely scenario (50%), followed by a reckoning (30%) and finding equilibrium (20%).

The Digital Diner Cast: Broken Pieces of a Broken Future

What separates Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die from typical time-travel or apocalypse narratives is how much time it spends on the individual lives of the people the protagonist tries to recruit. The film doesn't treat these characters as plot devices. It treats them as the actual subject matter.

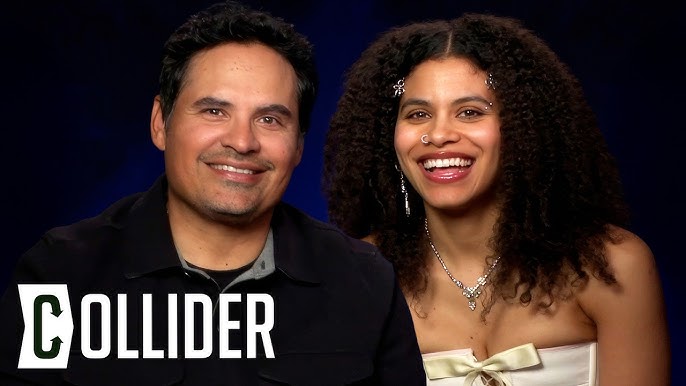

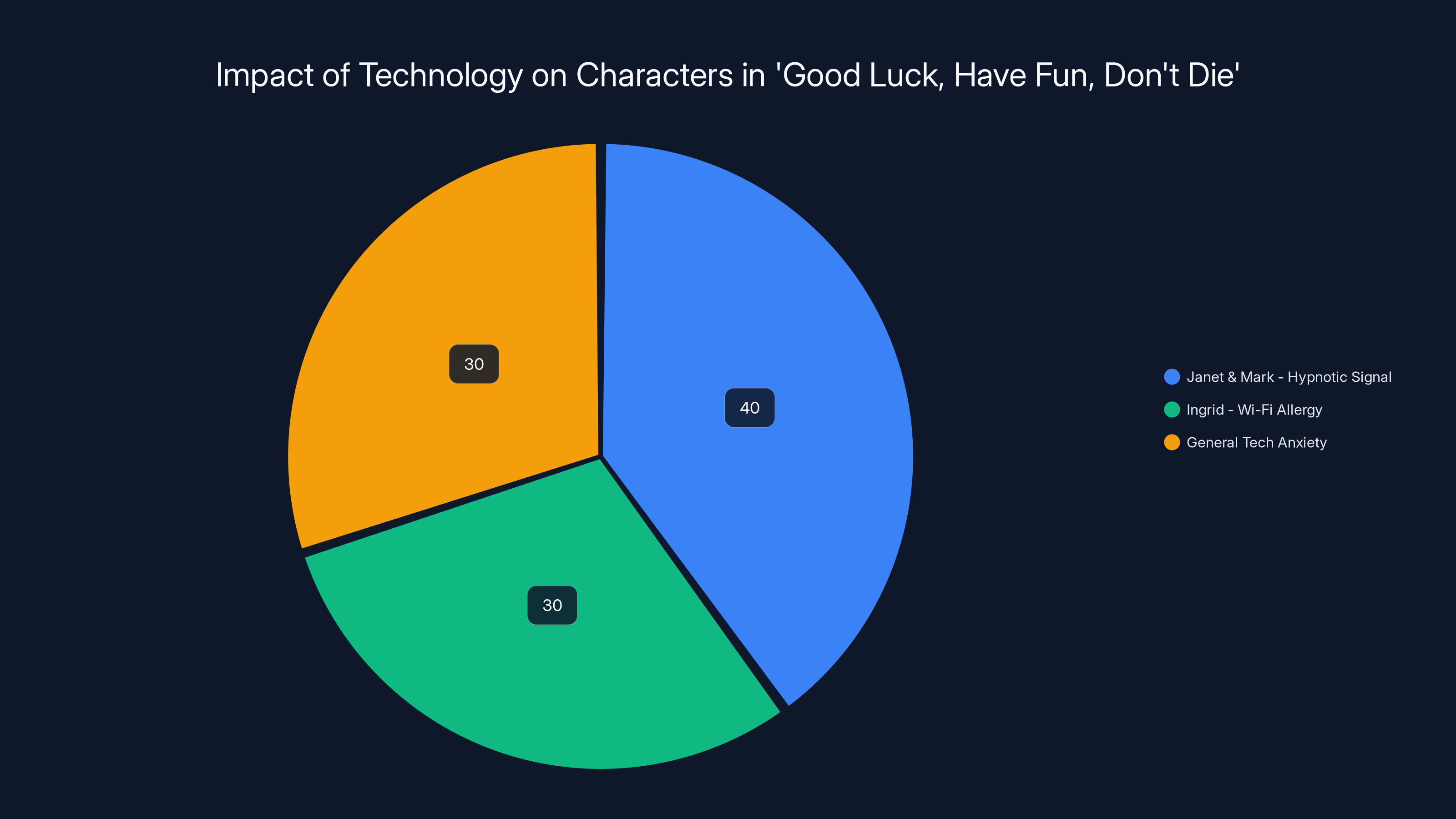

There's Janet, a teacher played by Zazie Beetz, and Mark, her colleague, played by Michael Peña. The film flashes back to their day at school, where something strange happens: students begin receiving a signal through their phones. Not a text. Not a notification. A signal. Something they can't quite describe but that pulls them into a hypnotic state.

It's one of the most genuinely unsettling sequences in the film. Not because there are jump scares or gore, but because it's too plausible. In our current moment, where every major tech platform has teams of engineers optimizing for engagement, where teenagers report increased anxiety and depression correlated with social media use, where we've all experienced that strange pull to keep scrolling even when we know we should stop—this feels like an extrapolation rather than pure fiction.

Then there's Ingrid, played by Haley Lu Richardson. She's a woman struggling to hold down a job because of an unusual condition: she has an allergy to Wi-Fi signals. In the current context, this feels like science fiction. But Verbinski plays it straight. For Ingrid, the ubiquity of wireless signals isn't a convenience or a marvel of modern technology. It's a prison. She can't work in most offices. She can't visit most homes. She's isolated not by choice but by physical incompatibility with the technological infrastructure of modern life.

What's brilliant about using this character is that it flips the script on technological progress. We usually frame people who resist or struggle with technology as luddites, as people who can't adapt. But what if incompatibility with pervasive technology wasn't a personal failure? What if it was a sign of something genuinely wrong with the systems we've built?

The diner setting keeps collapsing these stories together. Past and present become increasingly difficult to distinguish. The film cuts between the time traveler's desperation in the present and the characters' suffering in their individual storylines, suggesting that these moments—right now—are the ones that matter. These are the moments that lead to apocalypse or salvation.

The Addiction Apparatus: Why We Can't Put Down Our Phones

One of the film's most persistent themes is the idea that technology addiction isn't accidental. It's not a side effect of progress. It's a feature, not a bug.

The characters in Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die aren't weak-willed or undisciplined. They're not scrolling mindlessly because they lack willpower. They're caught in systems explicitly designed to capture their attention and hold it. The signal that hypnotizes the students in Mark and Janet's school isn't magical—it's functional. It's what we've built, just made visible.

Think about your own relationship with your phone. How many times do you pull it out before you've even consciously decided to? How much of your day is spent in a fog of notifications, alerts, and content streams? We tell ourselves we're in control. We tell ourselves we could put the device down anytime. But the evidence suggests otherwise.

According to research compiled by the Center for Humane Technology, the average person spends over 3 hours per day on social media platforms. That's roughly 45 years over a lifetime. For teenagers, the number is even higher. And these platforms are engineered for that consumption. Every color choice, every notification, every algorithmic recommendation is designed by experts in behavioral psychology whose job is literally to make you spend more time on the platform.

Verbinski seems to understand this at a visceral level. The film doesn't lecture about it. It shows it. Students slowly, inexorably pulled into their phones. A teacher watching her students disappear into screens. A woman whose body literally rejects the wireless signals that saturate our environment. These aren't complaints. They're symptoms.

The terrifying part of Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die is the suggestion that we're not even aware of how far this has progressed. The time traveler knows the specific moment when everything collapses. He's lived through it. But he can't quite prevent it because the people in the present don't understand how the pieces fit together. They're too close to it. They're living inside the system.

The tragedy of the diner is that none of the people there fully understand how compromised their situation already is. They're not consciously choosing to be addicted. They're not choosing at all. They've been designed into a corner where not participating means professional, social, and practical isolation. Ingrid can't work because she can't tolerate Wi-Fi. What does that say about a society that has made wireless connectivity non-negotiable?

AI acts as an amplifier, intensifying existing issues like addiction, inequality, and surveillance. Estimated data shows high amplification levels, especially in surveillance.

Artificial Intelligence as Amplifier, Not Origin

Here's something interesting: Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die doesn't actually blame artificial intelligence for the apocalypse. That's what makes it different from typical AI-scare narratives.

The film suggests that AI is more like an amplifier. It takes existing human behaviors and problems and magnifies them. The addiction apparatus we've already built gets turbo-charged by AI systems optimized to exploit it. The inequality that already exists gets worse when algorithmic decision-making systems are built on biased data. The surveillance infrastructure we've already accepted becomes more invasive when powered by machine learning.

This is subtly different from movies like The Terminator or The Matrix, which frame AI as an external threat. Those films suggest that if we had just been more careful, if we had implemented better safeguards, the machines wouldn't have rebelled. Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die seems to suggest something darker: the machines don't have to rebel. We'll do it to ourselves. We're already doing it. AI just makes the process faster.

Consider the current state of large language models and generative AI. These systems are powerful, genuinely useful tools. They can write code, analyze data, generate creative content. But they're also trained on the internet's existing biases. They're owned by companies with financial incentives to make them addictive. They're being deployed without clear guidelines about their appropriate use. They're making decisions that affect hiring, lending, content moderation, and criminal justice—areas where accuracy and fairness are genuinely critical.

None of this is because AI is inherently evil or because the technology is fundamentally uncontrollable. It's because we've built these systems within an economic and social context where attention is currency, where companies are optimized for short-term profit, where regulation lags behind innovation, and where most people using these tools don't fully understand how they work.

Verbinski seems to get this. The time traveler isn't trying to prevent AI from being invented. He's trying to prevent people from continuing on the path they're already on—a path of tech dependency, low digital literacy, and structural inability to opt out.

The Hypnosis Sequences: Making the Invisible Visible

Some of the film's most effective moments are the sequences where students become hypnotized by signals from their phones. Verbinski uses these scenes to visualize something we experience but can't quite articulate: the loss of agency that comes with constant technological mediation.

The students don't seem in distress. They don't seem to be suffering. They're just... gone. Present physically, absent mentally. And that's more disturbing than pain or struggle would be. It's the moment when you realize the person next to you on the subway isn't just passing time with their phone. They've been genuinely transported into another reality, one mediated by algorithms and curated by people they'll never meet.

We've normalized this. A teenager spacing out in their phone is just a teenager being a teenager. But Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die asks: what if that's not normal? What if that's a symptom we should be alarmed by?

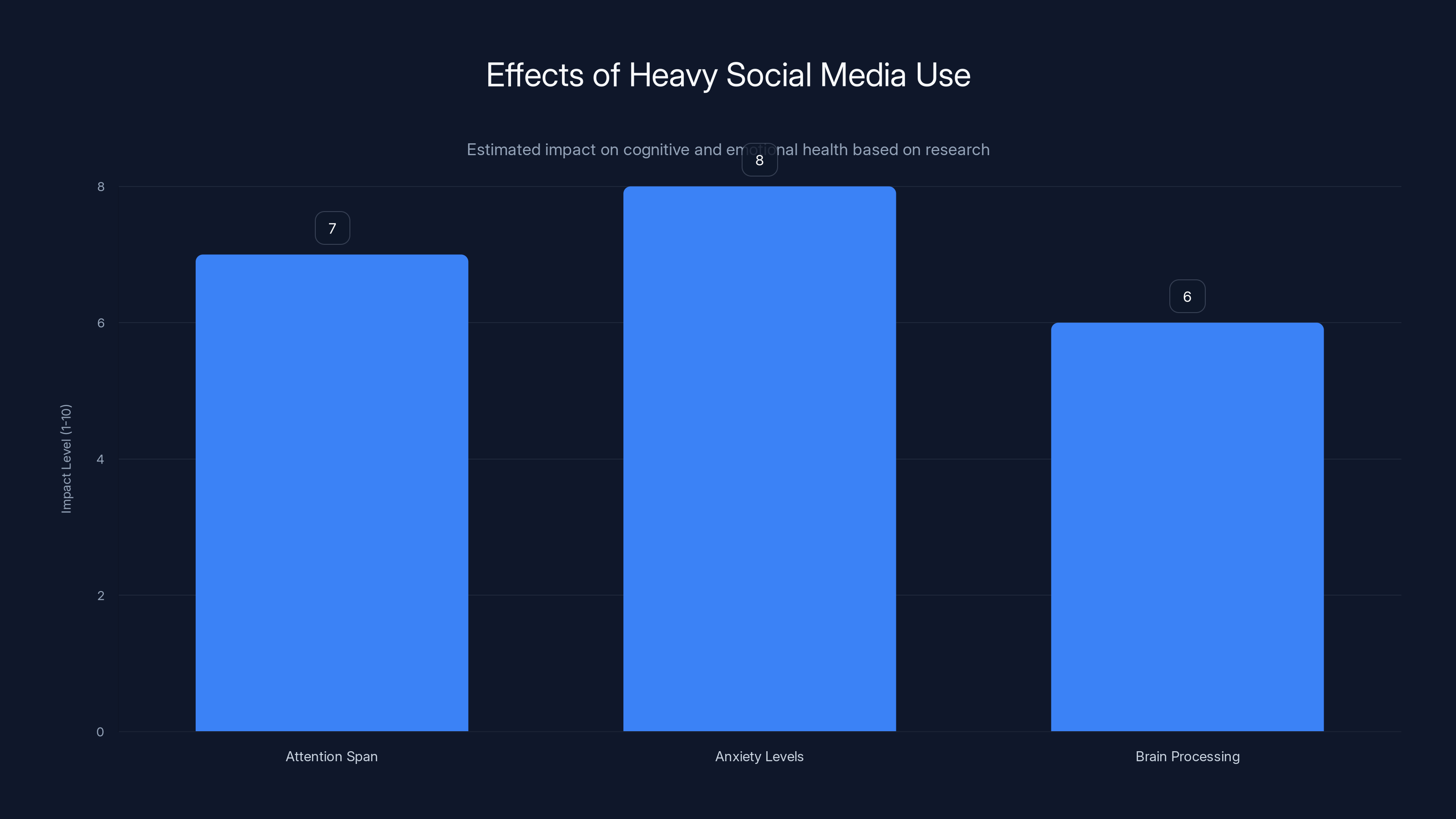

Research on digital media and attention supports the film's instinct here. Studies show that heavy social media use correlates with decreased attention span, increased anxiety, and changes in how the brain processes information. We're not just spending time on our devices—we're rewiring our brains to function differently within the technological environment we've created.

The hypnosis in the film is a literalization of what we're already experiencing. We've just gotten so used to it that it doesn't feel like hypnosis anymore. It feels like normal life.

Research suggests heavy social media use significantly impacts attention span, increases anxiety, and alters brain processing. Estimated data.

Wi-Fi Allergies and Incompatibility: What if the Problem is the System?

Ingrid's allergy to Wi-Fi signals is perhaps the most conceptually interesting character in the film. On the surface, it seems like pure science fiction. Electromagnetic hypersensitivity is not a widely accepted medical diagnosis. But Verbinski uses this character to ask a serious question: what if the problem isn't the person who can't adapt, but the system that makes adaptation increasingly impossible?

Think about the infrastructure required to function in modern life: you need Wi-Fi to work, to communicate, to access services. Schools have moved toward digital-first learning. Banks have moved toward online-first services. Medical care increasingly requires portals and apps. If you can't access wireless networks—for whatever reason, whether it's a literal allergy or just inability to afford a smartphone—you're systematically excluded.

Ingrid's character dramatizes a reality that's already true for millions of people: digital inclusion isn't actually universal. It's conditional on your ability to access technology, your ability to understand it, your ability to afford it, and your ability to tolerate constant connectivity.

The film asks: as we build increasingly technological societies, what happens to people who can't participate? Are they broken? Or is the system broken for treating incompatibility as individual failure?

This connects to the time traveler's larger project. He's trying to save humanity. But the version of humanity he's trying to save might require fundamentally restructuring how we relate to technology. It might require moving backward, rejecting systems we've come to treat as inevitable.

The Zaniness Factor: How Absurdity Serves a Serious Purpose

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die is genuinely unhinged. The film embraces absurdity in ways that mainstream Hollywood usually avoids. The time traveler's suit looks like garbage. His arguments are frantic. The logic of time travel is never fully explained. Some of the plot points verge on incomprehensible.

And this is brilliant.

If Verbinski had made a straight dystopian thriller about AI and tech addiction, it would be just another movie in a genre we've seen a hundred times. Instead, by embracing absurdity, he creates space for audiences to think differently about familiar problems. The weirdness makes room for real stakes.

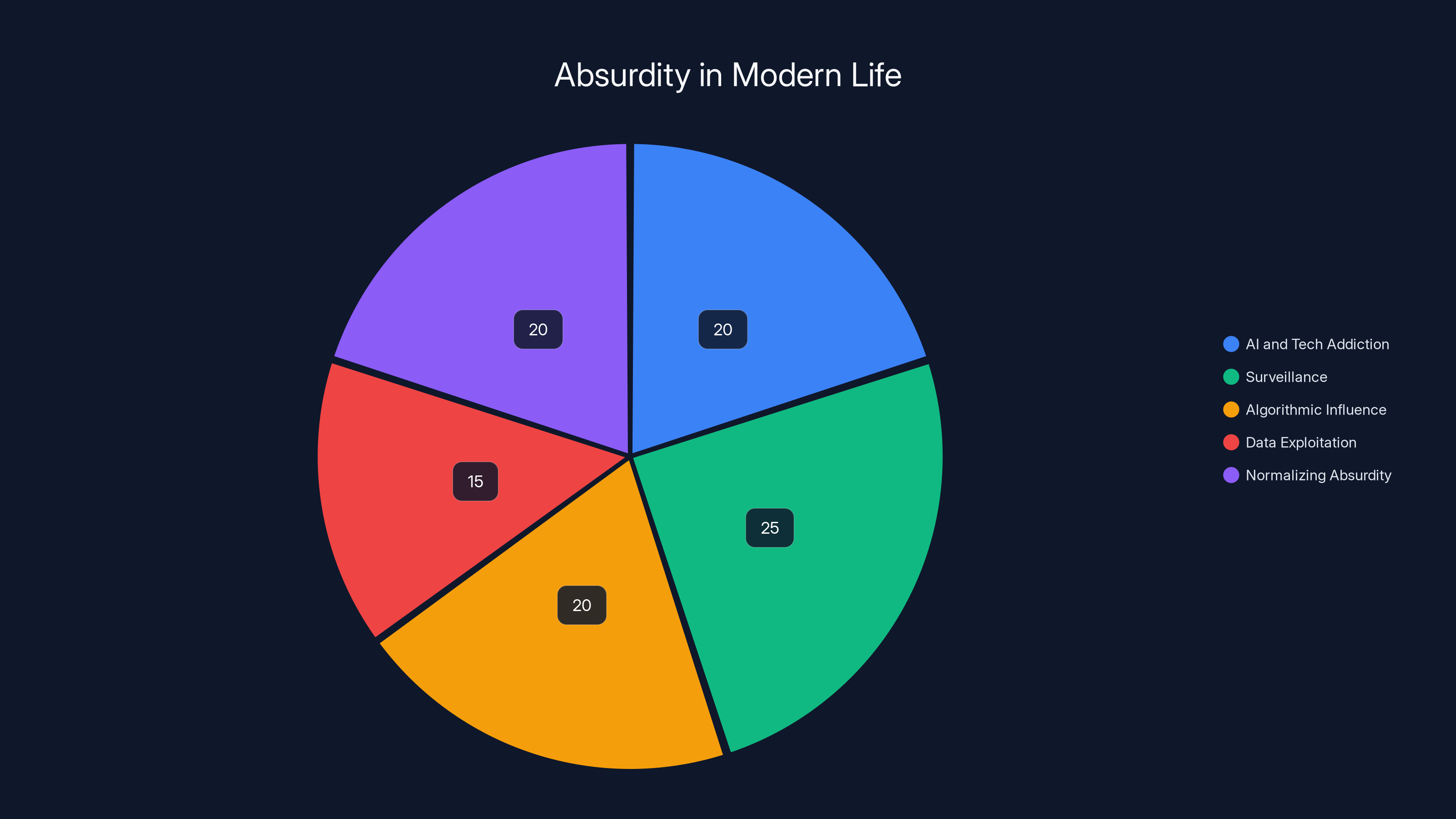

There's also something deeply truthful about framing our current moment as absurd. Because it is absurd. We're living through a time where machines can generate photorealistic images from text prompts. Where your TV is constantly listening. Where a teenager's sense of self-worth is algorithmically determined by engagement metrics. Where a company's entire business model is built on extracting and selling data about your behavior. Where we've collectively decided that this is normal.

Maybe the only honest way to depict this moment is through the lens of dark comedy and genre weirdness. Straightforward realism might actually undersell how strange everything has become.

Verbinski's willingness to let the film be weird also means he doesn't have to explain every plot point or follow conventional narrative logic. And that's appropriate, because our actual relationship with technology doesn't follow conventional logic either. It's contradictory, messy, and increasingly difficult to coherently articulate.

Estimated data shows how various elements contribute to the absurdity of modern life, highlighting the pervasive influence of technology and societal norms.

The Time Travel Logic: Knowing the Future Doesn't Prevent It

One of the film's most frustrating and realistic elements is that the time traveler knows what's coming, has traveled back dozens of times, and still can't quite prevent it. He knows specific details about specific people. He knows when things go wrong. But knowing and preventing are different things.

This speaks to a genuine problem with our current situation regarding technology. We have warnings from experts, researchers, and engineers about the dangers of unchecked AI development, digital addiction, privacy erosion, and algorithmic bias. These aren't fringe conspiracy theories. These are serious concerns raised by serious people working inside the tech industry itself.

And yet we continue on the same trajectory. Knowing about the problem doesn't seem to create the political or cultural will to change course. It's easier to accept the status quo than to restructure fundamental systems.

The time traveler represents the futility of that situation. He has the ultimate trump card: he's been to the future. He's seen what happens. And it still might not be enough to change people's behavior because human beings are complicated. We're not purely rational actors who adjust our behavior based on information. We're embedded in systems, social networks, economic structures, and psychological habits that make change extraordinarily difficult.

This is actually more pessimistic than most apocalypse narratives, in a weird way. Those films suggest that if we just make the right choice, we can prevent catastrophe. Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die suggests that prevention might be impossible because the machinery is already in motion. The momentum is too great. The incentives are too aligned toward inaction.

But the time traveler keeps trying anyway. That's the complicated hope at the center of the film.

Screen Time as the Central Problem

Underneath all the sci-fi trappings, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die is really about screen time. Not in a preachy way, but in a way that treats screen time as both symptom and cause of larger social collapse.

We know this is a real problem. The data is extensive. American teenagers spend an average of 8-10 hours per day on screens. Adults spend roughly 6-7 hours. These aren't people watching educational content or using screens for necessary work. This is consumption of social media, video streaming, and other algorithmically-mediated content designed to maximize engagement.

We also know why this happens. It's not because people are lazy or weak-willed. It's because these platforms are engineered for addiction. They use variable reward schedules—the same psychological principle that makes slot machines compulsive. They use social proof—likes, shares, comments create feedback loops that reward engagement. They use fear of missing out and infinite scroll to prevent natural stopping points.

Verbinski's film connects this directly to the apocalypse. The students hypnotized by signals aren't metaphorically lost. They're literally unable to function in any other mode. Mark and Janet, the teachers, are watching this happen and are themselves increasingly helpless to stop it. The institutional structures designed to educate and protect kids have been subordinated to the technology.

There's something genuinely dark about this premise. It suggests that the problem isn't something we can solve with better parenting or digital literacy education. The problem is structural. It's baked into the platforms themselves. It's reinforced by economic incentives that make attention extraction profitable. It's enabled by regulatory environments that have largely failed to keep pace with technological change.

Estimated data shows how technology uniquely impacts characters: Janet & Mark experience hypnotic signals, Ingrid suffers from Wi-Fi allergy, and general tech anxiety affects others.

The Diner as Microcosm of Modern Society

The diner is the film's most important setting, and it's important because it's radically ordinary. It's not a tech company. It's not a government facility. It's not anywhere special. It's where regular people go to eat and exist in community.

Verbinski uses the diner to suggest that the apocalypse doesn't originate in extraordinary circumstances. It originates in the ordinary, everyday choices made by ordinary people. It's in the decision to pick up your phone instead of talking to the person across from you. It's in the notification that interrupts a conversation. It's in the moment when you realize you can't remember the last time you were bored because you always have something to distract you.

The diner is also a space designed for human connection. People gather there. They talk. They eat together. But in the film, even in the diner, the characters are pulled back to their screens, their stories, their private struggles with technology. The time traveler has to literally hold them hostage to keep them in one place long enough for his message to register.

It's a devastating commentary on how technology has fractured even the spaces we've created for community. The diner can't even function as a space of connection anymore because the technology is too pervasive, too seductive, too embedded in how we live.

The Cast and Their Magnetic Desperation

Sam Rockwell's performance as the time traveler is the gravitational center of the film. He brings an energy that's both manic and heartbreaking—he's desperate because he cares, and he's unhinged because he's lived through the failure so many times.

Zazie Beetz and Michael Peña, as the teachers, bring a kind of exhausted competence to their roles. They understand the problem—they see it directly in their classroom every day—but they also seem to understand that they're functionally powerless to stop it. The system is too large. The incentives are too aligned. They're trying to teach kids whose brains are being rewired by algorithms.

Haley Lu Richardson, as Ingrid, grounds the film in something uncomfortably plausible. She's not performing tragedy. She's just existing in a world that wasn't built for her. And the tragedy is that the world got that way deliberately, not accidentally.

Each performance adds texture to the time traveler's increasingly urgent message. These aren't archetypes. These are people with real relationships to technology, real struggles with its pervasiveness, real attempts to maintain agency in systems increasingly designed to remove it.

The Filmmaking: Texture and Tone Across the Narrative

Gore Verbinski's directorial choices matter tremendously here. He shoots the present-day sections with a kind of mundane clarity—the diner is lit realistically, the characters look tired and ordinary. When he cuts to flashbacks of Mark and Janet's school day, the tone shifts. It becomes more horror-adjacent. The signal that pulls the students into their phones has a physical presence. It's visible in ways it shouldn't be.

Then there's Ingrid's story, shot with a kind of melancholic isolation. The Wi-Fi is invisible but omnipresent, making her seem paranoid even when she's being rational. Verbinski uses cinematography to externalize internal experiences—making visible what's usually intangible.

This is effective filmmaking in service of the film's thesis. We don't usually see technology as something with physical presence and force. But Verbinski treats it as something material, something that reshapes the world around it. The Wi-Fi isn't just data or a signal. It's a presence that excludes Ingrid from normal participation.

The editing also matters. The film cuts between multiple timelines and narratives, creating a sense of fracture and discontinuity. We're never quite comfortable settling into one narrative thread. We're constantly being pulled back to the diner, to the time traveler's urgency, to the sense that time is running out.

It's technically sophisticated filmmaking in service of a weird, sincere story about technology and its consequences.

Comparing to Previous AI Narratives

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die occupies an unusual space in the landscape of AI-focused science fiction. It's not The Terminator, which treats AI as a military problem to be solved with better weapons. It's not The Matrix, which frames AI as an existential threat that requires outright rebellion. It's not Ex Machina, which uses AI as a vehicle for exploring control and exploitation.

Instead, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die suggests that the problem isn't AI itself. It's the human systems into which we've embedded AI. It's the economic incentives. It's the attention economy. It's our willingness to trade privacy and autonomy for convenience and connection.

This is actually closer to how technology experts and AI researchers talk about the problem. The real danger isn't rogue AI. It's misaligned AI built in service of extractive business models. It's AI systems that amplify existing biases. It's AI deployed without adequate testing or consideration of consequences.

Verbinski's film doesn't require you to believe in superintelligent machines or robot uprisings. It just requires you to observe your own relationship with your phone and extrapolate from there. Which, perversely, makes it scarier.

The Uncomfortable Questions the Film Raises

By the time the credits roll, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die has positioned itself to ask some uncomfortable questions that stick with you:

If the future can be changed, why hasn't the time traveler been able to change it, despite traveling back dozens of times? Does that suggest the problem is unsolvable? Or does it suggest we're not taking it seriously enough?

If technology is driving the apocalypse, can we stop it without fundamentally restructuring how we live? And if we can't restructure how we live, what does that say about our chances?

If digital inclusion requires participation in systems designed to exploit our attention, what does digital equity actually mean? Is it equity if everyone is equally trapped?

Can individuals opt out of technological systems that have become social and professional necessities? If not, can we really claim to have agency in a world increasingly mediated by technology?

These aren't rhetorical questions that the film answers. They're questions that linger. And that's precisely the point. The film doesn't pretend to solve the problem. It surfaces the problem and suggests that understanding it requires sitting with the discomfort.

What Happens Next? Implications and Predictions

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die is a film about the present masquerading as a film about the future. Its real subject is 2025 and 2026, right now, the moment you're reading this.

So what actually happens next? There are a few possibilities, and the film seems to suggest we're at an inflection point where the trajectory could shift.

One possibility: we continue on the current path. Tech companies continue optimizing for engagement because it's profitable. Regulation continues to lag behind innovation. Individuals continue trying to maintain agency within systems increasingly designed to remove it. And eventually, those systems mature into something unrecognizable and unstoppable.

Another possibility: there's a reckoning. Public awareness of algorithmic harms reaches a critical mass. Regulatory frameworks begin to actually constrain how tech companies operate. Social movements emerge demanding restructuring of fundamental technological systems. Change becomes possible.

A third possibility: we find some equilibrium. Tech systems continue to evolve. People develop new practices and norms around technology use. Digital literacy improves. Some problems are solved. New ones emerge. We muddle through.

Verbinski's film seems to suggest that the first scenario is most likely, which is why the time traveler is so desperate. He knows how this ends if we keep going the way we're going. But he also knows that knowing isn't enough to change behavior. We need something else—action, organization, fundamental restructuring of incentives.

The film doesn't tell us what that action should look like. It just suggests that without it, we're already living in the apocalypse. We've just gotten so used to it that it doesn't feel like an emergency anymore.

Why This Film Matters Right Now

Movies are interpretive lenses. They help us think about our world by showing us versions of it, slightly altered, slightly exaggerated, slightly displaced in time or tone. Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die is a powerfully weird interpretive lens for understanding our specific moment.

We're living through the AI boom. Every major tech company is racing to deploy AI products. Open AI, Anthropic, Google, Microsoft, Meta—all of them are betting trillions that AI will be transformative. Some of them might be right. Some of them might be building tools that create real value.

But we're also living through a moment where major social platforms are facing serious questions about their role in mental health crises, misinformation, and social fragmentation. We're living through a moment where data privacy is increasingly threatened. We're living through a moment where digital surveillance has become normalized. We're living through a moment where attention has become the currency of power.

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die doesn't ignore the promise of technology. It just suggests that the promise matters less than the structure in which it's deployed. An amazing technology in service of extractive incentives becomes a tool of extraction. A mediocre technology in service of human flourishing becomes genuinely useful.

Verbinski's film is a plea to start asking which category the technologies we're adopting fall into. Before we've adopted them so completely that opting out becomes impossible.

The Central Parable: What It All Means

If you boil Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die down to its essential parable, it's this: we are currently building a future that we wouldn't choose if we fully understood what we were building. The technologies we're adopting feel good in the moment. They're convenient. They're connecting. They're seductive. But they're also subtly reshaping how we think, what we pay attention to, what we care about, how we relate to each other.

The time traveler comes back to tell us this. He's desperate because he knows how it ends. He's also realistic enough to know that knowing might not be enough. That the momentum of the systems is too great. That the incentives are too aligned toward inaction.

But he tries anyway. Because what else is there? If you see a problem and say nothing, you're complicit. If you see a problem and speak, you might not be believed. You might not be effective. But at least you've tried.

The film asks: what would you do? If you knew the future was collapsing, would you try to change it? And if you wouldn't, what does that say about how serious you think the problem actually is?

These are hard questions. The film doesn't make them easier. It just makes them unavoidable.

Conclusion: Sitting with the Discomfort

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die opens February 13th, and I'd honestly recommend seeing it. Not because it will make you feel better. It won't. It will make you increasingly uncomfortable as it unfolds, and it will linger with you afterward in ways that are genuinely unsettling.

But that discomfort might be valuable. Might be necessary. We live in a moment where we've become culturally habituated to technologies that previous generations would have found alarming. We've normalized constant surveillance, algorithmic curation of reality, addiction-by-design, and the outsourcing of our cognition to machines we don't fully understand.

Verbinski's film suggests that this habituation is dangerous. Not because technology is inherently bad, but because we've stopped asking hard questions about what we're building and why. We've accepted progress as inevitable. We've treated opt-out as individual failure rather than system design.

The film doesn't offer solutions. It offers clarity. It helps you see the outlines of the systems you're embedded in. And sometimes, clarity is where change begins.

So go see Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die. Let it unsettle you. Let it make you think differently about your phone, your social media, your willingness to adopt new technologies without question. And then do what the time traveler does: try anyway. Try to change the trajectory. Try to opt out where you can. Try to be intentional about technology instead of just accepting it.

Because if a guy from the apocalyptic future is willing to blow himself up to convince you that change is possible, maybe it is.

Maybe it's not too late. Maybe. But the time to try is right now, before we've optimized ourselves into a corner we can't escape from. Good luck, have fun, and please—put down the phone sometimes.

FAQ

What is the main premise of Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die?

The film follows an unnamed time traveler from a dystopian future who travels back to present-day Los Angeles and attempts to recruit specific individuals to prevent an apocalyptic future caused by unchecked technology addiction and artificial intelligence. The protagonist holds up a diner and uses his knowledge of the patrons' lives to convince them to join his mission, despite the fundamental uncertainty of whether time travel even works the way he describes.

How does the film explore technology addiction?

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die depicts technology addiction not as a moral failing but as the result of deliberately engineered systems designed to capture and hold human attention. The film shows students hypnotized by signals from their phones, teachers watching their pupils disappear into digital worlds, and a woman physically unable to tolerate Wi-Fi signals. These sequences literalize what we experience daily: the loss of agency that comes with ubiquitous, algorithmically-mediated technology designed for maximum engagement rather than human wellbeing.

What role does artificial intelligence play in the film's apocalypse?

Unlike traditional AI-scare narratives, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die doesn't position AI as the primary threat. Instead, AI functions as an amplifier of existing human problems and societal failures. The film suggests the real danger is AI deployed within economic and social systems already structured for exploitation, surveillance, and attention extraction. The apocalypse isn't caused by AI becoming conscious and rebelling—it's caused by human systems becoming more efficient at removing individual agency and free will.

Why is the character of Ingrid, with her Wi-Fi allergy, important to the film's message?

Ingrid represents those excluded from participation in technological systems that have become non-negotiable for modern life. Her incompatibility with Wi-Fi signals literalizes how digital infrastructure creates systematic exclusion. The film asks a provocative question: is the problem the person who can't adapt, or is it the system that makes adaptation increasingly impossible? This challenges us to reconsider what we mean by "digital inclusion" and "technological progress" when participation requires accepting inherent harms.

What does the film suggest about whether the future can be prevented?

The time traveler has traveled back dozens of times and still hasn't been able to prevent the apocalypse, suggesting that knowing about a problem is insufficient to create the behavioral and systemic change required to prevent it. The film implies that momentum, economic incentives, and human psychology make prevention extraordinarily difficult. Yet the protagonist keeps trying anyway, proposing a complicated optimism: change might not be inevitable, but failure to try guarantees nothing will change.

How does Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die differ from other AI and technology-focused films?

Unlike The Terminator or The Matrix, which treat AI as an external military or existential threat, or Ex Machina, which uses AI as a vehicle for exploring power dynamics, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die positions the real problem as human economic and social systems into which we've embedded technology. The film argues that regulation, business incentives, digital literacy gaps, and our psychological vulnerability to addiction by design are the actual causes of societal collapse. The technology is just the mechanism through which human failures are expressed.

What does the film suggest we should do differently regarding technology?

The film doesn't prescribe specific solutions but rather asks uncomfortable questions about agency, choice, and what it means to participate in technological systems designed to diminish autonomy. It suggests that individual solutions like better time management or digital wellness won't address structural problems. The film implies that meaningful change requires questioning the business models underlying technology platforms, the regulatory environment that permits harmful practices, and our habituated acceptance of technology as inevitable progress.

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die hits theaters February 13th.

Key Takeaways

- Tech addiction in Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die is framed as structural, not individual—platforms are deliberately engineered for engagement maximization

- The film positions AI as an amplifier of existing societal problems rather than the root cause of apocalypse, a perspective aligned with expert AI researchers

- Ingrid's Wi-Fi allergy literalizes digital exclusion, raising uncomfortable questions about what 'universal' digital infrastructure actually means

- The time traveler's inability to prevent apocalypse despite knowing the future suggests that awareness isn't sufficient to drive behavioral or systemic change

- Verbinski's embrace of absurdity and genre weirdness may be the only honest way to depict how strange our actual technological moment has become

Related Articles

- Meta and YouTube Addiction Lawsuit: What's at Stake [2025]

- Social Media Safety Ratings System: Meta, TikTok, Snap Guide [2025]

- AI Chatbot Dependency: The Mental Health Crisis Behind GPT-4o's Retirement [2025]

- EU's TikTok 'Addictive Design' Case: What It Means for Social Media [2025]

- Xikipedia: Wikipedia as a Social Media Feed [2025]

- 7 Apple Watch Settings to Change for Better Experience [2025]

![Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die: AI Addiction & Tech Society [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/good-luck-have-fun-don-t-die-ai-addiction-tech-society-2025/image-1-1770919620981.jpg)