The Wave of Google Antitrust Lawsuits: Understanding the Publisher Backlash

In 2025, Google faces an unprecedented wave of antitrust litigation from major media companies seeking damages for alleged illegal monopolization of digital advertising infrastructure. Following a historic federal court ruling in early 2025 that found Google guilty of monopolizing publisher ad server markets and illegally tying its ad tech products together, publishers have moved aggressively to recover financial damages. The Atlantic, Penske Media (owner of Rolling Stone, Billboard, and The Hollywood Reporter), and Vox Media have all filed substantial lawsuits in federal courts seeking compensation for what they characterize as a decade of anticompetitive conduct that artificially suppressed their advertising revenues.

This litigation wave represents a critical inflection point in the digital advertising ecosystem. Unlike previous regulatory actions that focused on preventing future misconduct, these damages lawsuits address the concrete financial harm publishers claim to have suffered. The cases collectively represent billions of dollars in potential liability for Google and could fundamentally reshape how the company operates its advertising technology division. The emergence of these lawsuits also signals a broader shift in how antitrust enforcement is being weaponized—moving from government-led prosecution to private litigation where damaged parties seek recompense.

For publishers struggling with revenue pressures from years of declining advertising rates, these lawsuits offer a potential financial lifeline. However, the litigation also exposes fundamental vulnerabilities in the digital advertising supply chain. Understanding these lawsuits requires examining the technological infrastructure at the heart of modern digital publishing, the market dynamics that enabled Google's dominance, and the legal framework that now challenges that dominance. This comprehensive guide explores every dimension of Google's antitrust exposure, from the underlying monopoly practices to the implications for publishers, advertisers, and technology platforms.

The timing of these lawsuits is particularly significant given the broader regulatory environment. Across the United States, government agencies are aggressively pursuing antitrust actions against major technology companies. The Federal Trade Commission, Department of Justice, and state attorneys general have all intensified scrutiny of Google's business practices. Against this backdrop, publishers are leveraging the court's findings to build their own cases, essentially using the government's antitrust victory as a foundation for private damages claims.

The Core Monopoly: Google's Publisher Ad Server Dominance

What is a Publisher Ad Server?

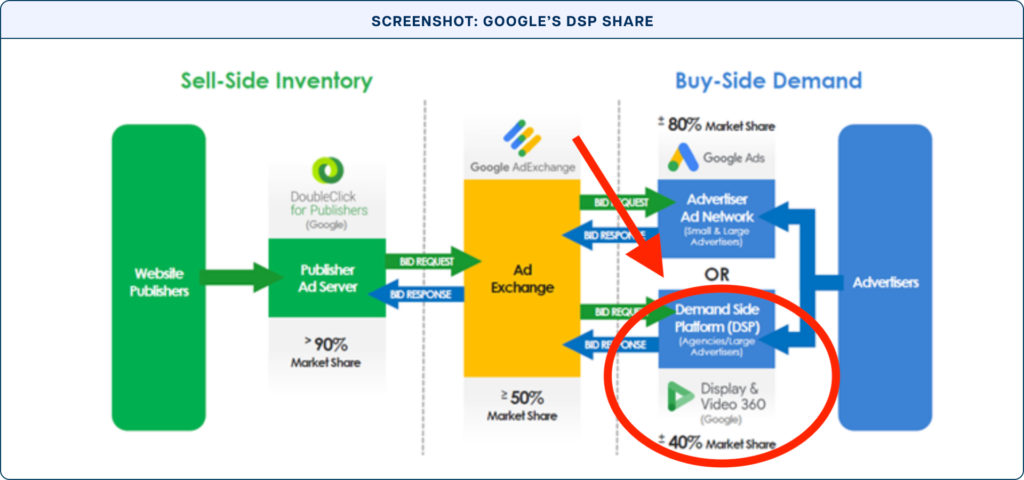

A publisher ad server is critical infrastructure in the digital advertising ecosystem, functioning as the core management system that publishers use to control and monetize their website inventory. The technology allows publishers to decide which advertisements appear on which pages, set pricing parameters, manage inventory allocation, and generate reporting data about ad performance. Google's publisher ad server product, called Google Ad Manager, handles the vast majority of publisher ad serving operations across the internet.

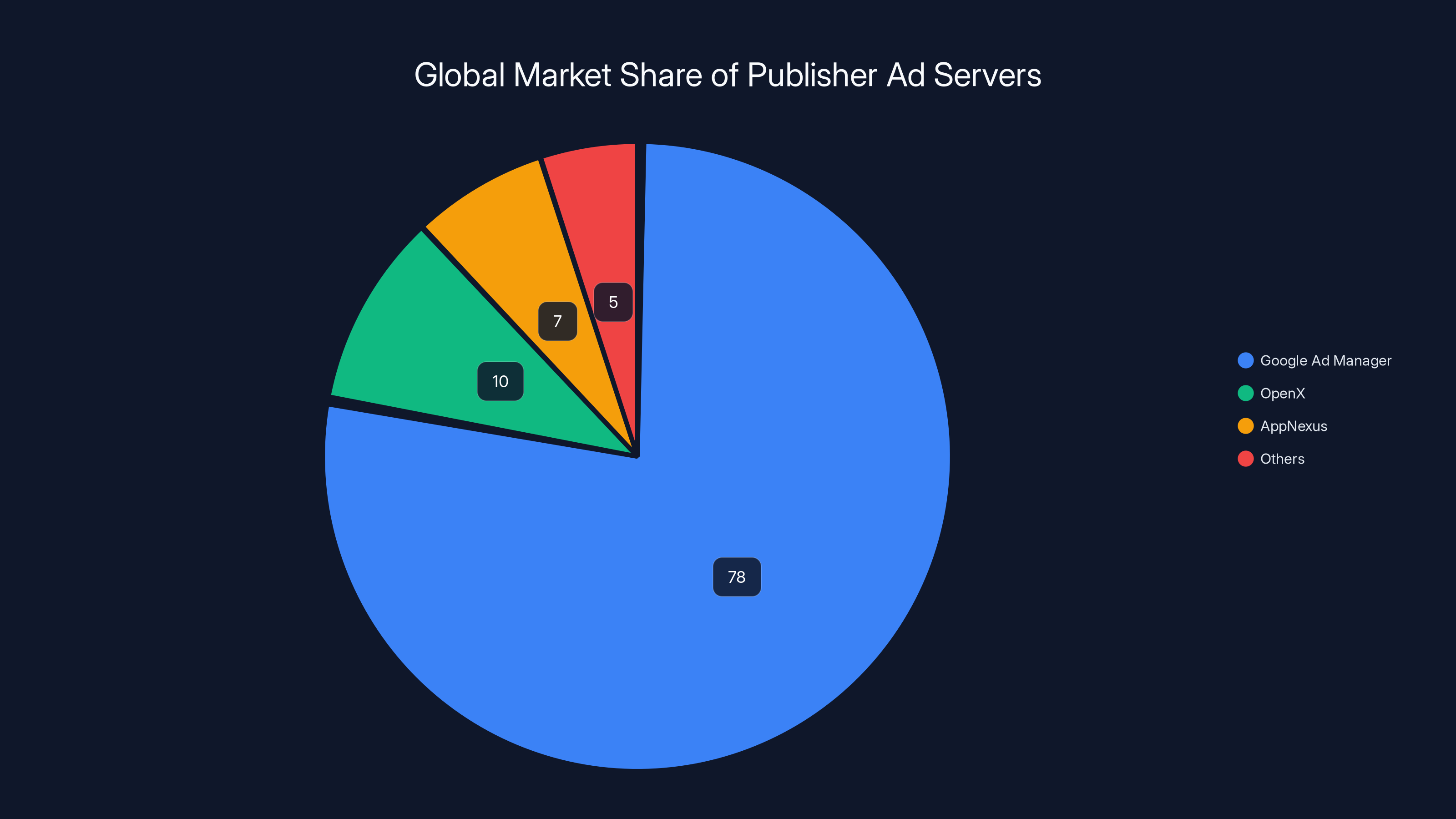

The publisher ad server sits at a crucial chokepoint in the digital advertising supply chain. Publishers must use some form of ad serving technology to manage their advertisement inventory and connect with demand sources (advertisers and ad networks willing to buy that inventory). Without an ad server, publishers cannot effectively monetize their content. Google's dominance in this market—controlling approximately 78% of publisher ad server usage globally—gives the company extraordinary leverage over publisher pricing and commercial negotiations.

Historically, independent competitors like Open X and App Nexus provided viable alternatives to Google's ad serving solutions. These platforms offered publishers genuine choices and the ability to negotiate commercial terms. However, over the past decade, Google leveraged its integrated position across multiple advertising platforms to gradually consolidate control over publisher ad serving. The company's ability to favor its own products within its ad server, combined with predatory pricing and exclusive dealing practices, systematically eliminated competitors and trapped publishers into using Google's ecosystem.

The publisher ad server represents what antitrust experts call a "gateway monopoly"—a dominant position in a foundational technology that enables control over downstream markets. By controlling the publisher ad server, Google gained the ability to determine which demand sources publishers could efficiently connect with, what pricing publishers could demand, and how much transparency publishers received about their own advertising transactions.

Market Concentration and Competitive Barriers

The publisher ad server market has experienced dramatic consolidation over the past fifteen years. In 2010, the market was fragmented among multiple competitors including Double Click (which Google acquired), Adtech, Flourish, Atlas, and numerous regional players. Today, Google controls roughly three-quarters of the global publisher ad server market, with App Nexus and Open X sharing most of the remaining market share. This concentration far exceeds the thresholds that traditionally trigger antitrust scrutiny.

Several structural barriers protect Google's dominant position and prevent new entrants from challenging the company. First, network effects create powerful advantages for the incumbent. Publishers prefer ad servers that reach the largest pool of advertisers and ad networks; advertisers prefer ad servers that reach the largest inventory of publisher sites. This circular dynamic reinforces Google's dominance—publishers migrate to Google because most advertisers are already there, and advertisers prioritize Google because most publishers use it. Breaking this cycle requires either massive scale or sustained investment losses to bootstrap competitive alternatives.

Second, switching costs lock publishers into Google's ecosystem. Migrating an ad server involves technical implementation work, reintegrating multiple advertising partners, extensive testing, and temporary disruptions to revenue during the transition period. For a mid-sized publisher generating millions of dollars in daily ad revenue, the risk of downtime or integration problems during a migration can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. These switching costs create a moat around Google's market position that insulates the company from competitive pressure.

Third, data advantages accumulated through Google's dominant market position create self-reinforcing monopoly dynamics. Google's ad server processes billions of advertising impressions daily, generating detailed performance data that helps Google's other advertising products (like its demand-side buying platform) identify valuable advertising inventory and optimize bidding strategies. Competitors lack this data advantage, making their products less effective and creating perpetual disadvantages.

Fourth, exclusive dealing practices have systematically eliminated alternatives. When Google entered the publisher ad server market through its acquisition of Double Click, the company offered preferential pricing and exclusive features to publishers willing to commit exclusively to Google's stack. Publishers that adopted Google's integrated suite of products (ad server, ad network, SSP, and exchange) received discounts and functionality advantages unavailable to competitors' products. These practices effectively eliminated independent choices for publishers.

Google Ad Manager dominates the publisher ad server market with a 78% share, significantly outpacing competitors like OpenX and AppNexus. Estimated data based on industry analysis.

The Ad Exchange Market and Illegal Tying

How Ad Exchanges Function in Digital Advertising

An ad exchange is a real-time auction marketplace where advertisers bid on individual advertising impressions. When a user visits a publisher's webpage, the exchange processes an auction in milliseconds, with multiple advertisers submitting bids for that specific impression based on their campaigns, budgets, and targeting criteria. The exchange infrastructure matches bidders with inventory and ensures transactions execute at scale. Google's ad exchange product is called Google Ad Exchange (Ad X), and the company controls approximately 45% of the global ad exchange market, making it the largest single player in this critical infrastructure.

Ad exchanges differ from ad networks in important ways. An ad network bundles inventory from multiple publishers and sells it as a package, sometimes without sharing detailed data about individual impressions with publishers. An ad exchange, by contrast, operates a transparent auction where publishers can see bids and advertisers can see which publishers they're buying from. Advertisers generally prefer exchanges because they enable more efficient buying, and publishers generally prefer exchanges because they generate higher prices and more transparency.

Google's dominance in ad exchange created a secondary monopoly problem. Publishers needed to connect their dominant ad server (Google Ad Manager) with ad demand sources. Google's own ad exchange (Ad X) naturally became the primary connection point, but Google's access to the highest-quality inventory and its ability to preference its own exchange within its ad server created asymmetric advantages. Publishers that wanted to use Google Ad Manager but preferred to sell inventory through a competing exchange (like Open X or App Nexus) faced technical and commercial friction that made alternatives less attractive.

The Illegal Tying Practice Explained

The court ruling identified a fundamental violation: Google illegally tied its publisher ad server with its ad exchange, making it extremely difficult for publishers to use the ad server without defaulting to the exchange. Technically, publishers could theoretically use Google Ad Manager with competing ad exchanges, but the architecture made this arrangement inefficient and costly. Google's ad server was optimized to work seamlessly with Ad X, with competing exchanges receiving lower priority, reduced data flow, and slower integration.

This tying arrangement violated antitrust law under the doctrine established in foundational cases like Microsoft's bundling of Internet Explorer with Windows. The legal principle is straightforward: a company with monopoly power in one market (the publisher ad server) cannot tie that product to another product (the ad exchange) in ways that extend monopoly power into adjacent markets or exclude competitors. The court found that Google's tying practice:

- Denied competing ad exchanges the ability to offer comparable functionality

- Forced publishers to use Google's ad exchange even when they preferred alternatives

- Reduced competition and innovation in the ad exchange market

- Generated artificial market share for Google's exchange through leveraging, not competition

The economic effect of this tying was substantial. When publishers could not efficiently connect their ad server with preferred exchanges, they lost bargaining power to negotiate better rates. Competing exchanges could not achieve scale because publishers faced friction in integration. The ad exchange market, which should have been competitive and dynamic, became increasingly dominated by a single player.

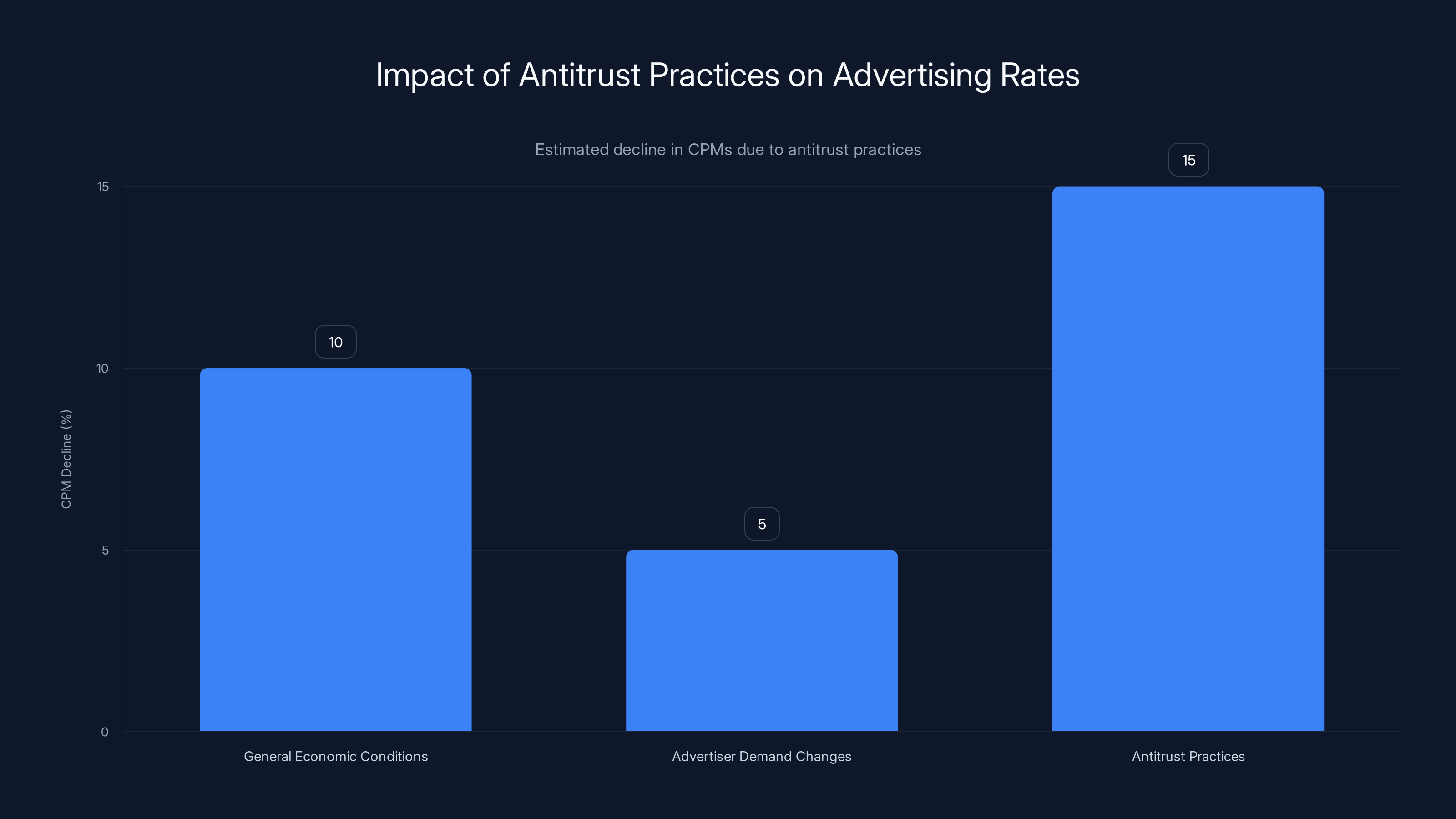

Estimated data suggests that antitrust practices have led to a 15% decline in CPMs, beyond declines due to economic conditions and advertiser demand changes.

The Atlantic's Antitrust Lawsuit: Damages and Legal Theory

The Atlantic's Complaint and Financial Claims

The Atlantic, owned by billionaire philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs, filed its antitrust lawsuit in the Southern District of New York, seeking damages for Google's alleged illegal monopolization. The complaint alleges that Google's conduct across publisher ad server and ad exchange markets caused direct financial harm to The Atlantic by artificially depressing the prices The Atlantic could charge for advertising inventory. Rather than operating in a competitive advertising market where multiple ad exchanges compete for inventory, The Atlantic was forced into a relationship with Google's exchange where competition was eliminated.

The Atlantic's legal theory rests on a straightforward damages claim: absent Google's anticompetitive conduct, The Atlantic would have been able to sell its advertising inventory at higher prices to competing ad exchanges. This is a factually grounded claim—economic research demonstrates that monopolists charge supracompetitive prices and suppress supplier revenues. In this case, Google's monopoly in ad serving and exchange enabled the company to suppress the rates it paid publishers for inventory.

The complaint provides specific examples of how Google's monopoly practices harmed The Atlantic. The allegations highlight that The Atlantic, despite producing premium journalistic content that attracts high-value audiences, was unable to negotiate favorable terms with Google or develop alternative distribution channels because Google's ad server was effectively required for conducting business. Publishers that attempted to migrate away from Google's ecosystem faced technical obstacles, lost data access, and reduced demand from advertisers concentrated on Google's platforms.

Quantifying Publisher Damages

Calculating damages from antitrust violations requires establishing several elements: the existence of a monopoly, anticompetitive conduct, causation, and quantifiable harm. The court's initial ruling established the monopoly and anticompetitive conduct. The remaining question is damages—how much money should Google pay for the harm it inflicted?

Publisher damages calculations typically employ economic methodologies that compare actual pricing under monopoly conditions with the counterfactual pricing that would have prevailed in a competitive market. Research indicates that publisher ad rates have declined significantly over the past decade, even as advertiser demand and audience engagement remained relatively stable. Economic analysis suggests that a substantial portion of this rate compression resulted from reduced competition in publisher monetization infrastructure.

For a publisher like The Atlantic, annual ad revenue reaches hundreds of millions of dollars. If anticompetitive conditions suppressed rates by just 10-15% annually over a ten-year period, the cumulative damages could exceed several hundred million dollars. Multiply this across hundreds of major publishers pursuing similar claims, and the total exposure becomes extremely significant. Industry analysts estimate that Google's ad tech monopoly may have cost publishers collectively over $8-12 billion in suppressed revenues since approximately 2010.

Vox Media's Case: Owned by Advertisers, Harmed as Publishers

Vox Media's Unique Position in the Lawsuit

Vox Media's lawsuit presents a particularly compelling narrative because Vox Media operates simultaneously as a major publisher and as a participant in the broader digital advertising ecosystem. The company publishes premium content across multiple brands (Vox, The Verge, Polygon, and numerous other properties) that collectively attract hundreds of millions of monthly users. These properties generate substantial advertising revenue, making Vox Media especially sensitive to any factors that suppress publisher rates.

Vox Media's head of communications issued a statement highlighting the company's core argument: "In filing this lawsuit, we are seeking monetary damages and an end to Google's deceptive and manipulative practices in order to protect our ability to continue investing in the trusted content that our audience relies upon." This framing connects the antitrust claim directly to journalism and content quality. Vox Media argues that suppressed publisher revenues force publishers to reduce investment in content creation, which ultimately harms audiences by reducing available quality journalism.

The connection between publisher revenues and content quality is economically validated. Publishers that generate higher advertising revenues have more resources to invest in reporting, editorial staff, and long-form investigative projects. Conversely, when publisher revenues contract due to anticompetitive compression, the immediate effect is typically cost-cutting that reduces editorial investment. The antitrust claim becomes not merely about business economics but about the sustainability of quality journalism in the digital era.

The Broader Implications for Media Companies

Vox Media's lawsuit also highlights a structural challenge facing digital media companies: dependence on a single platform for critical business functions. Publishers like Vox Media have built their entire digital advertising infrastructure around Google's products. Google provides the ad server, often provides significant inventory demand through its exchange, and provides attribution and measurement tools through Google Analytics and other products. This vertical integration creates vulnerability—if Google uses its monopoly power in one component to advantage itself in others, publishers have limited recourse.

For news organizations specifically, the antitrust implications extend beyond simple economics. Digital advertising has become the dominant revenue source for most publishers, replacing subscriber revenue and classified advertising revenue that dominated traditional media. If antitrust violations suppress digital advertising revenues, publishers cannot simply replace this income through alternative sources. The result is that anticompetitive conduct in ad tech directly threatens the financial model that sustains quality journalism.

Vox Media's legal team is positioned to present detailed internal evidence about the company's negotiations with Google, alternative arrangements the company explored, and the specific ways that Google's practices limited Vox Media's ability to optimize its ad monetization. This granular evidence can be powerful in damages litigation because it demonstrates real-world harm to specific sophisticated business actors, not merely theoretical economic effects.

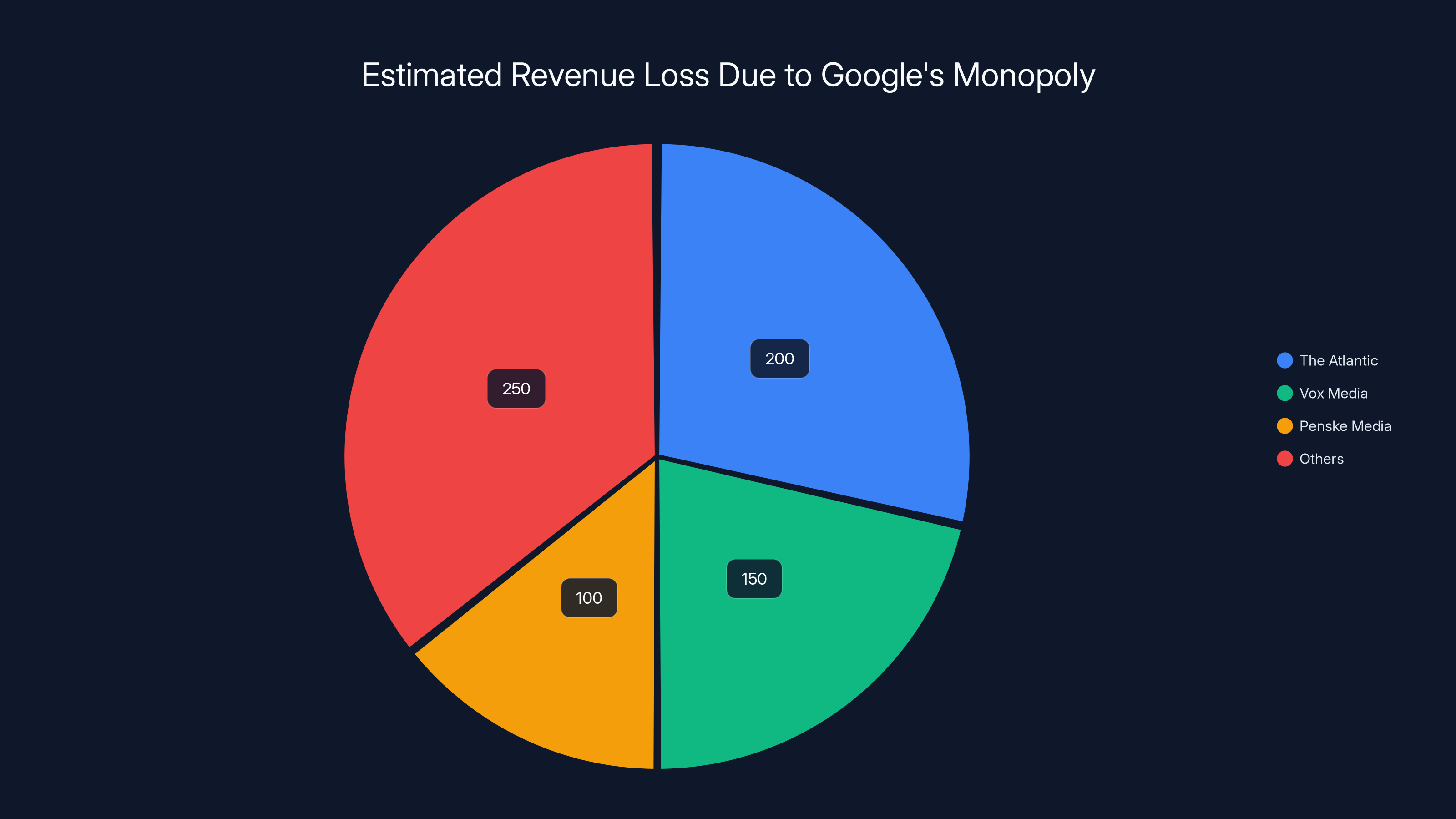

Estimated data shows significant revenue loss for publishers due to Google's monopoly, with total losses potentially reaching hundreds of millions of dollars.

Penske Media's Strategic Litigation Involvement

Penske Media's Publishing Portfolio and Antitrust Exposure

Penske Media, owned by Jarl Mohn, controls one of the largest portfolios of premium digital publishers in the United States, including Rolling Stone, Billboard, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, and numerous other high-traffic properties. These brands collectively reach hundreds of millions of monthly users and generate substantial advertising revenue. Penske Media's participation in the antitrust litigation reflects the company's significant exposure to anticompetitive ad tech practices—when publishers as large and sophisticated as Rolling Stone and Billboard cannot escape Google's monopoly conditions, the damages potential becomes substantial.

Interestingly, Penske Media also has investment stakes in Vox Media, creating a complex web of relationships within the publishing industry's response to Google's antitrust liability. This network of shared ownership and commercial relationships demonstrates how extensively Google's ad tech practices penetrate the digital publishing ecosystem. It is not merely a handful of outlier companies alleging harm—instead, major publishers across numerous market segments are pursuing parallel antitrust claims.

Penske's brands are particularly valuable targets for advertisers seeking premium audiences. Rolling Stone reaches music enthusiasts and younger demographics; Billboard reaches the music industry; The Hollywood Reporter reaches entertainment professionals and consumers. Despite commanding premium advertiser interest, these properties are subject to the same ad tech infrastructure constraints as every other publisher. The disconnect between audience value and publisher revenue reflects the distortion introduced by Google's monopoly—advertisers pay premium prices because of audience quality, but publishers receive suppressed rates because they cannot access competing monetization infrastructure.

The Coordinated Litigation Strategy

The timing and coordination of lawsuits from Vox Media, The Atlantic, and Penske Media suggests a coordinated legal strategy. While the companies filed suits in the same jurisdiction (Southern District of New York) within the same time period, this coordination likely reflects the advice of common legal counsel and shared understanding that the court's antitrust ruling created favorable conditions for damages litigation. Publishers are essentially following a roadmap established by the Justice Department's successful prosecution.

This coordinated approach increases pressure on Google in multiple ways. First, multiple suits create procedural complexity—Google must defend itself against parallel claims in multiple cases, increasing legal costs. Second, coordinated litigation generates momentum that encourages additional publishers to pursue claims, creating a cascade effect. Third, the visibility of multiple high-profile publishers suing simultaneously generates media attention that amplifies the reputational costs to Google.

Ad Tech Providers Entering the Fray: Pub Matic and Open X

How Ad Tech Companies Suffered Competitive Harm

Beyond publisher litigation, Google faces parallel lawsuits from ad technology providers like Pub Matic and Open X, companies that attempted to compete in exchange and SSP (supply-side platform) markets but faced barriers created by Google's monopoly. These companies argue that Google's dominance in publisher ad serving enabled the company to favor its own SSP (Ad Manager Supply-side component) and exchange over competing products, systematically excluding competitors from reaching publisher inventory.

Pub Matic is a significant ad tech platform that provides publishers with tools to optimize and sell their inventory across multiple ad exchanges. The company went public in 2021 and has achieved meaningful scale in SSP markets. However, Pub Matic argues in its antitrust litigation that Google's control over the publisher ad server created insurmountable barriers to competition. Because Google's ad server interfaces more efficiently with Google's own SSP than with Pub Matic's platform, publishers have structural reasons to consolidate around Google's integrated offering.

Open X, another substantial ad tech company, similarly argues that Google's ad server monopoly created competitive disadvantages. Open X attempted to develop a competitive ad exchange and SSP, but the company faced the disadvantage that it could not achieve equivalent technical integration with the dominant ad server. Publishers using Google Ad Manager could use Open X's exchange, but the integration would be less seamless than using Google's own exchange, creating functional disadvantages for Open X even when the company offered technically superior or more competitive products.

The competitive harm to companies like Pub Matic and Open X is distinct from publisher harm, but complementary. When Google can prevent emerging competitors from achieving scale, Google eliminates competitive pressure that might otherwise drive innovation and price competition. The absence of viable competitors means Google faces no downward pressure on the fees it charges or upward pressure on the percentage of advertiser spending that reaches publishers. This lack of competition benefits Google but harms the entire ecosystem.

Testimony from Ad Tech Companies in the Original Trial

During the Justice Department's trial against Google, representatives from Pub Matic, Open X, and other ad tech companies provided crucial testimony about competitive barriers. These witnesses explained how Google's integrated market position allowed the company to discriminate against competitors in ways that smaller or non-integrated companies could not match. Specifically, ad tech executives testified about:

- Instances where Google suppressed data sharing with competitors' products

- Technical integration advantages that Google's own products received within its ad server

- Instances where Google engaged in exclusive dealing, requiring publishers that used Google Ad Manager to also commit to using Google's SSP or exchange

- Competitive disadvantages that emerged once Google tightened its product integration

This testimony from industry participants was particularly persuasive to the court because it came from direct competitors with firsthand knowledge of competitive dynamics. When executives who compete against Google daily explain how the company's practices exclude competition, the testimony carries credibility that generic economic testimony sometimes lacks.

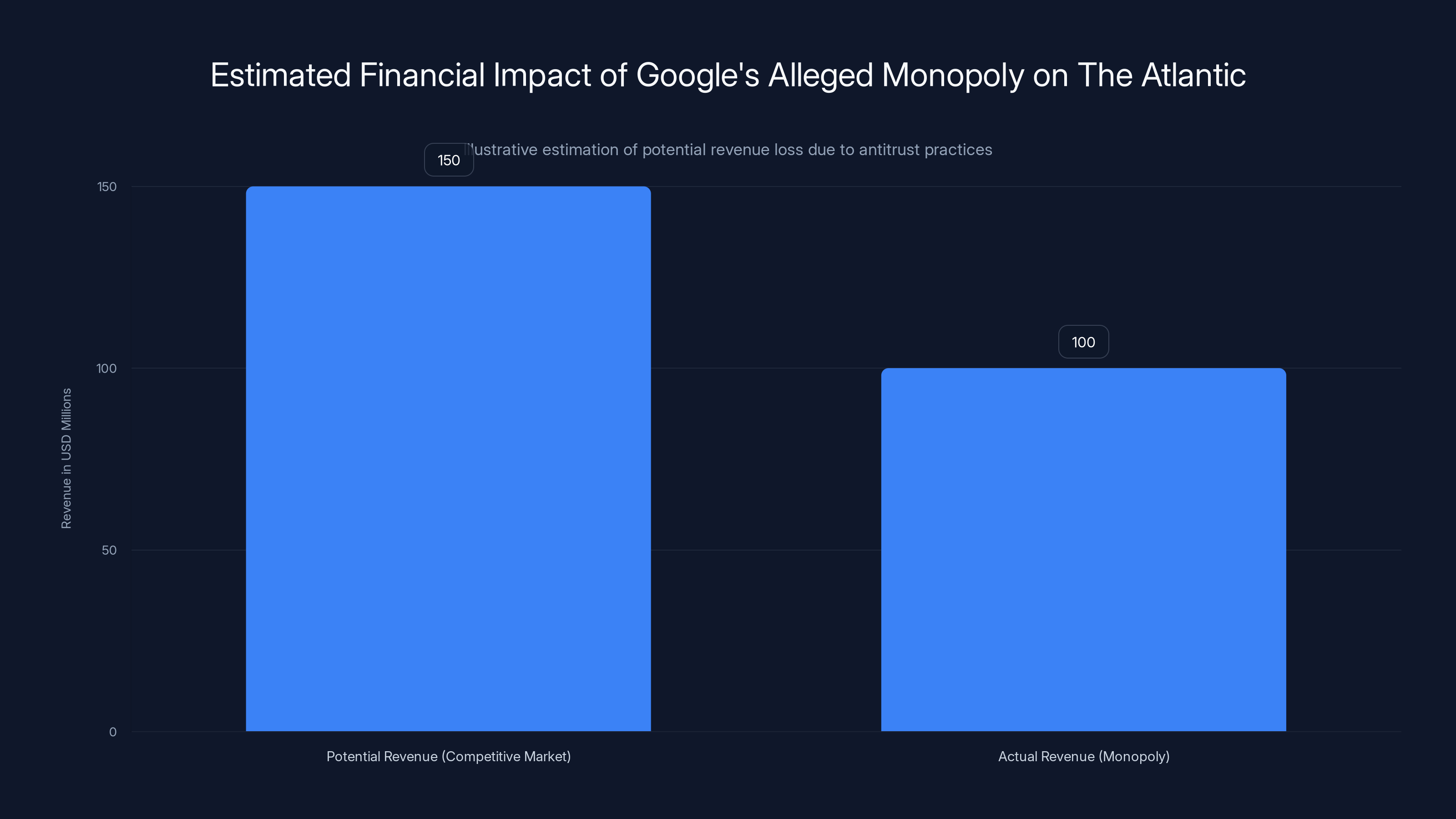

Estimated data suggests The Atlantic could have earned 50% more in a competitive market compared to the monopolized conditions imposed by Google's ad practices.

The Federal Court's Antitrust Ruling: What the Judge Found

Judge Leonie Brinkema's Historic 2025 Decision

In early 2025, Eastern District of Virginia Judge Leonie Brinkema issued a comprehensive antitrust ruling that fundamentally altered the legal landscape surrounding Google's ad tech business. Judge Brinkema found that the Justice Department successfully proved that Google had illegally monopolized two distinct markets: the market for publisher ad servers and the market for ad exchanges that facilitate ad transactions. These findings represent among the most significant antitrust determinations against a major technology company in recent decades.

Judge Brinkema's ruling was carefully reasoned and economically grounded. The judge reviewed extensive testimony from industry participants, economic experts, and Google executives, synthesizing this evidence into detailed findings of fact. The court determined that Google's market share in publisher ad serving substantially exceeded levels that create a presumption of monopoly power under antitrust law. The court also examined Google's conduct and found that the company had engaged in exclusionary practices designed to maintain its dominant position by limiting competitors' access to scale.

Critically, Judge Brinkema found that Google's conduct extended beyond legal competition on the merits. The company had not achieved dominance solely through superior products or lower prices. Instead, Google employed various anticompetitive practices including tying arrangements, exclusive dealing, predatory pricing (pricing below competitive rates to eliminate competitors), and leveraging dominant position in one market to exclude competitors in adjacent markets.

The Tying Claim and Market Leverage Analysis

Among the most significant findings was the court's determination that Google had illegally tied its dominant publisher ad server with its ad exchange. Specifically, the court found that:

- Google possessed monopoly power in the publisher ad server market

- Google tied its ad exchange to the ad server in ways that made the two products difficult to unbundle

- The tying arrangement foreclosed competition in the ad exchange market by preventing competing exchanges from achieving equivalent scale

- Consumers (publishers) were harmed because they lost the option to choose their preferred ad exchange while using Google's ad server

This tying analysis followed the legal framework established in landmark cases like United States v. Microsoft, where the court found that Microsoft had illegally tied Internet Explorer to Windows in ways that prevented competing browsers from achieving market share. The principle is that a company cannot leverage dominant power in one market to extend that dominance into adjacent markets through tying arrangements.

The court's findings on illegal tying were particularly important for damages litigation because they establish direct causation between Google's conduct and publisher harm. Publishers could not achieve better pricing or service by switching to competing exchanges because Google's infrastructure made such switches technically difficult and commercially disadvantageous.

The One Favorable Ruling for Google

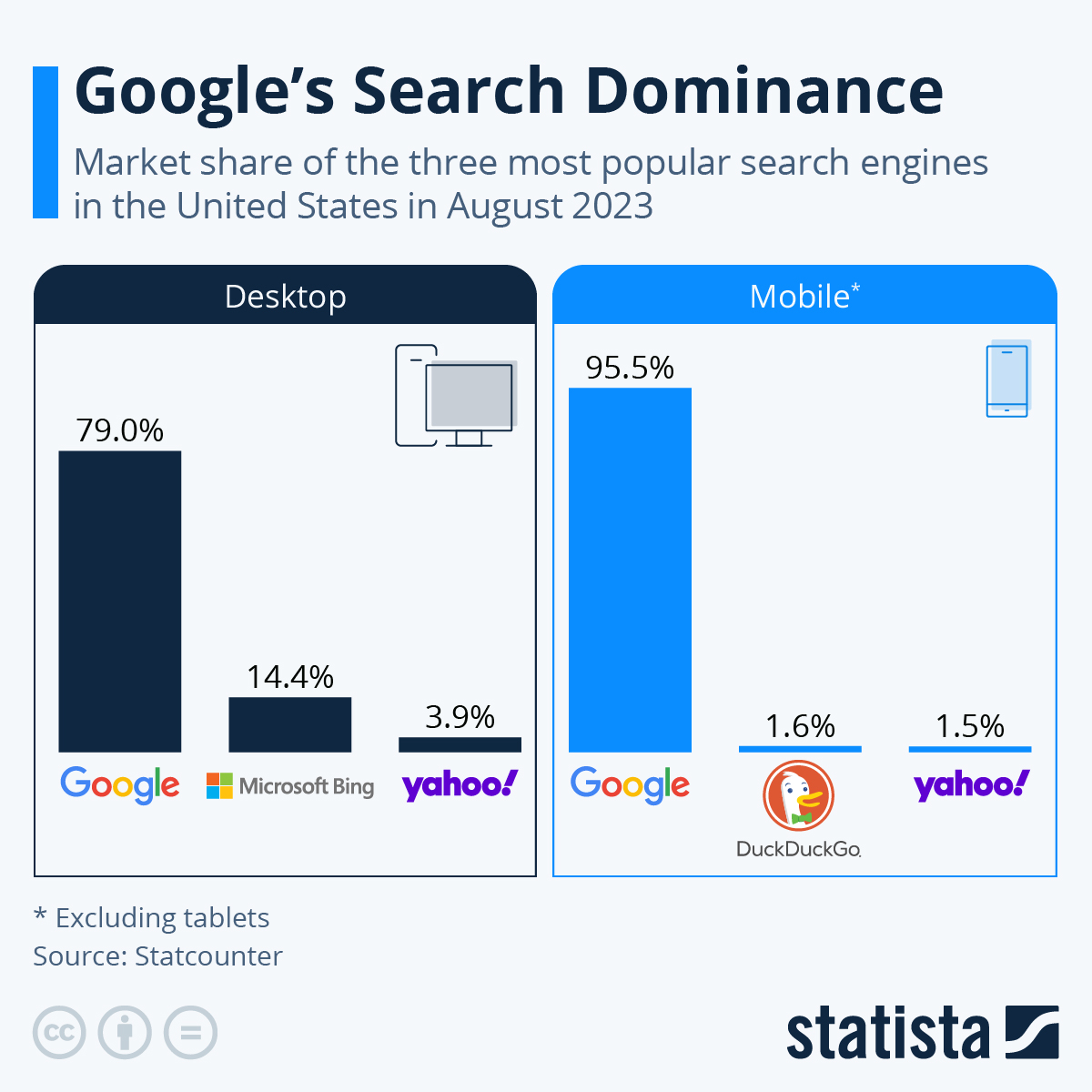

While Judge Brinkema's ruling was substantially unfavorable to Google, the court did find in Google's favor on one count. The DOJ alleged that Google had monopolized the market for advertiser-side buying tools (demand-side platforms or DSPs). Judge Brinkema found that the DOJ had not proven monopolization in this market with sufficient clarity. The court noted that while Google had a strong presence in DSP markets, competing platforms including The Trade Desk, Amazon DSP, and others offered viable alternatives that advertisers actively used.

This single favorable finding is significant because it demonstrates that the court was not reflexively anti-Google but instead carefully evaluated the facts and legal standards for each market. The ruling that Google had not monopolized DSP markets reflects the existence of more vigorous competition on the advertiser-demand side compared to the publisher-supply side of advertising markets. This asymmetry—where publisher-side markets are highly concentrated and advertiser-side markets are more competitive—reflects the structural imbalance in ad tech that enabled Google's dominance.

Damages Calculations and Financial Exposure

Economic Models for Quantifying Harm

Establishing damages from antitrust violations requires economic analysis comparing the actual world (under monopoly conditions) with a counterfactual world (what would have occurred under competition). For publisher antitrust claims against Google, damages typically flow from the fact that publishers received lower prices for their advertising inventory than would have prevailed in a competitive market.

Economic expert analysis typically employs one of several methodologies:

Yardstick analysis compares pricing in competitive markets with pricing in the monopolized market. For publisher ad serving and exchange, economists examine markets outside Google's control (sometimes using international markets where Google has less dominance, or examining historical periods before Google's monopoly solidified) and calculate the premium or discount compared to the monopolized market.

Econometric regression analysis controls for relevant variables affecting ad pricing (audience size, content quality, seasonal factors, etc.) and isolates the effect of market structure (monopoly versus competition) on price levels. This approach requires detailed transactional data about advertising rates over time and across different publishers and ad exchanges.

Event study analysis examines pricing changes at key moments—when publishers attempted to exit Google's ecosystem, when competing ad exchanges were launched, or when competitive conditions changed—to identify the price impact of reduced competition.

Economic research suggests that publisher advertising rates have declined significantly over the past decade, with rates per thousand impressions (CPMs) experiencing compression of 15-30% beyond what would be expected from general economic conditions and changes in advertiser demand. If a substantial portion of this compression resulted from Google's anticompetitive practices suppressing competition, the cumulative damages become substantial.

Estimating Google's Ad Tech Revenue at Risk

Google's advertising business generated approximately

For context, Google's total net income in 2024 was approximately $88 billion, meaning ad tech-related damages could represent a meaningful but not existential liability. However, the reputational damage and potential forced divestiture of ad tech business could carry much greater consequences. If courts order Google to divest its ad tech business or prohibit certain integrated practices, the financial impact could extend far beyond monetary damages into lost future profits.

The Multiplier Effect: Individual Damages Across Hundreds of Publishers

What makes the antitrust exposure particularly significant is the potential for hundreds of publishers to pursue parallel damages claims. While The Atlantic, Vox Media, and Penske Media represent high-profile cases, mid-sized and smaller publishers also suffered harm from Google's monopoly practices. If even 500 publishers pursued damages with average claims of

Moreover, some state antitrust laws provide for treble damages (three times actual damages), meaning that if a court determines Google inflicted

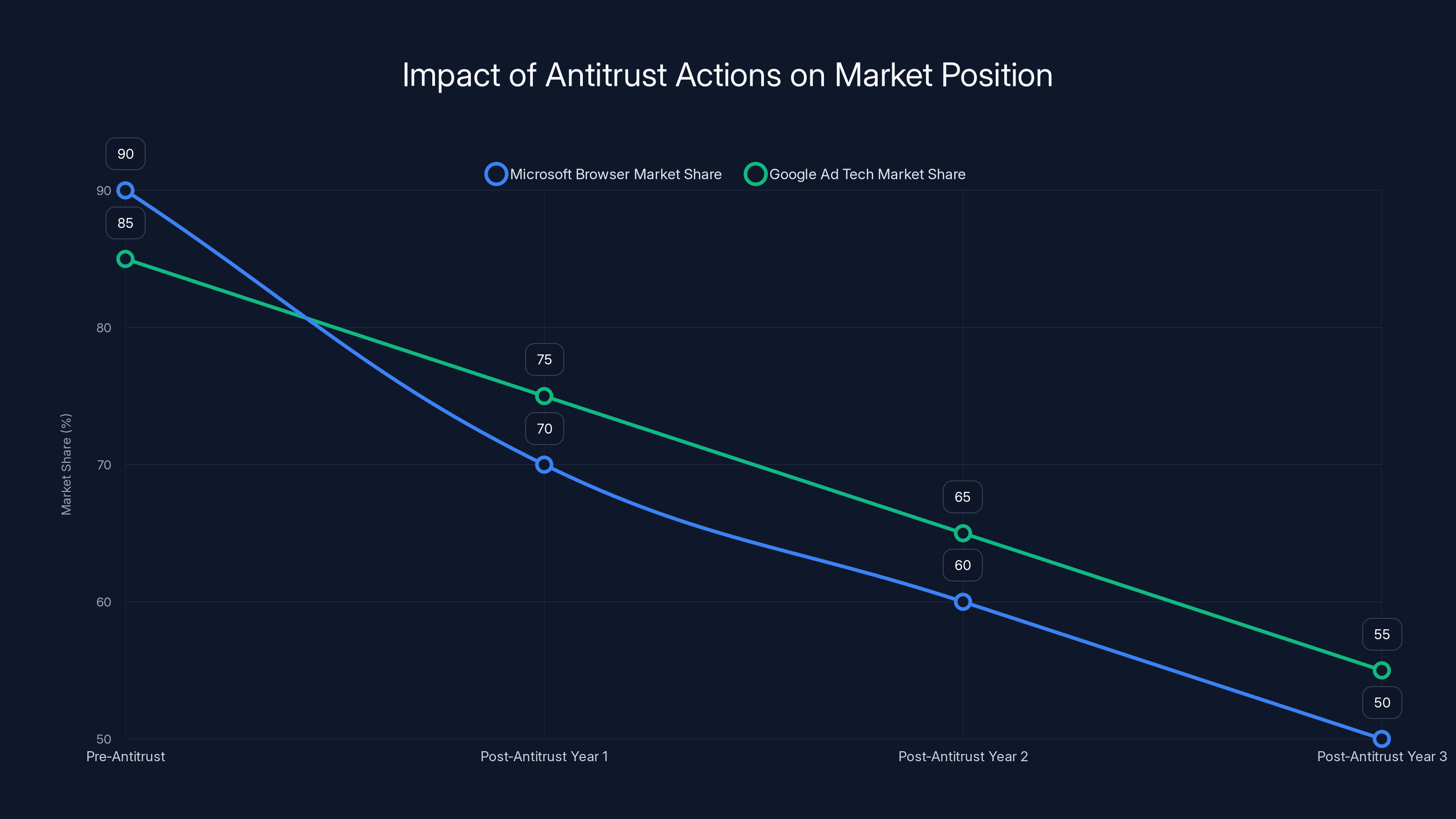

Estimated data shows that both Microsoft and Google experienced significant market share reductions post-antitrust actions, highlighting the long-term impact of regulatory interventions.

Remedies and Potential Structural Changes to Google's Business

The Ongoing Remedy Phase of DOJ Litigation

Judge Brinkema is currently considering remedies in the second phase of the DOJ's antitrust case. This phase focuses on what structural or behavioral changes Google should be required to implement to restore competition to the markets the company monopolized. The range of potential remedies extends from moderate behavioral restrictions to comprehensive business restructuring.

Behavioral remedies would restrict how Google operates its ad tech business without fundamentally restructuring the company. Examples might include:

- Prohibiting tying arrangements that require publishers using Google Ad Manager to use Google's exchange

- Mandating data sharing where Google must provide competing exchanges with equivalent access to performance data available within Google's system

- Restricting preferential treatment where Google cannot advantage its own products within its ad server

- Establishing interoperability standards requiring Google to ensure seamless integration with competing ad exchanges

- Price regulation capping the fees Google can charge for ad serving or exchange services

Behavioral remedies have the advantage of preserving the efficiency of Google's integrated system while limiting anticompetitive abuse. However, behavioral remedies require ongoing regulatory monitoring to ensure compliance and can be difficult to enforce effectively.

Structural remedies would require Google to separate its business into independent units. The most dramatic option would be forced divestiture of Google's ad tech business entirely. Under a divestiture remedy, Google would sell its Ad Manager and Ad X products to separate companies, ensuring that Google's search dominance could not leverage into ad tech dominance. Alternative structural remedies might involve separating the publisher ad server from the exchange, or separating Google's advertiser-demand business from its publisher-supply infrastructure.

Structural remedies carry the advantage of being relatively permanent—once Google divests ad tech, the company cannot simply ignore the restrictions and rebuild an integrated monopoly. However, structural remedies are disruptive, eliminate potential synergies from integration, and raise complex questions about valuation and transition.

Potential Outcomes and Precedent

While the remedy phase remains ongoing, historical precedent suggests that the court will likely impose some combination of behavioral and structural restrictions. The DOJ has indicated support for structural remedies, arguing that Google's conduct is so pervasive that behavioral restrictions alone cannot effectively restore competition. However, Google will argue for minimal remedies, emphasizing the efficiency of its integrated platform and the risk that separating business units would harm consumers through reduced innovation and higher prices.

The remedy decision could be reached by late 2025 or 2026, potentially before damages litigation is fully resolved. This sequencing creates interesting legal dynamics—if the court orders structural remedies in the DOJ case, those remedies might substantially alter Google's business before damages are finally calculated, potentially reducing the harm and thus damages owed.

The Regulatory and Competitive Context

Global Antitrust Scrutiny of Tech Platforms

Google's antitrust exposure in the United States exists within a broader global context of intensified regulatory scrutiny of large technology companies. The European Union has aggressively pursued antitrust cases against Google, including cases focused specifically on search advertising and Android. Several EU cases have resulted in multibillion-dollar fines and behavioral remedies. The UK's Competition and Markets Authority has similarly initiated investigations into Google's practices.

This global pressure creates leverage for both plaintiffs and defendants. On one hand, publishers and ad tech companies can cite European regulatory findings to support arguments that Google engaged in anticompetitive conduct. On the other hand, Google can argue that imposing stringent US remedies while European regulators take different approaches creates inefficiency and competitive disadvantage for US technology platforms.

The cumulative effect of global antitrust actions is likely to force Google to make material changes to its business practices. Even if the US litigation results in behavioral rather than structural remedies, the combined weight of enforcement actions globally suggests that Google's integrated ad tech model—which leverages dominance in one market to extend dominance across related markets—is becoming untenable from a regulatory perspective.

The Relationship Between Government Prosecution and Private Damages Litigation

The current wave of private damages litigation follows directly from the government's successful antitrust prosecution. Under a legal principle known as collateral estoppel or res judicata, facts established in the government case can often be used in private litigation to establish damages claims. Specifically, the government's findings that Google monopolized publisher ad serving and illegally tied products creates a strong foundation for private plaintiffs arguing that they suffered harm from the same conduct.

This relationship between government prosecution and private damages creates powerful incentives for private parties to pursue claims once government enforcement succeeds. The government bears the burden and expense of prosecution; once the government wins, private parties can leverage those victories to pursue damages with lower risk and lower cost than if they had to independently prove monopolization. This dynamic explains why antitrust litigation often follows this two-stage pattern: government prosecution establishes liability, private litigation recovers damages.

However, this dynamic also creates risks of excessive private litigation. Even if the government's case identifies real harm, private damages litigation can magnify exposure through duplicative claims and inflated damage calculations. From Google's perspective, managing both government-mandated remedies and multiple rounds of private damages litigation creates substantial financial and operational uncertainty.

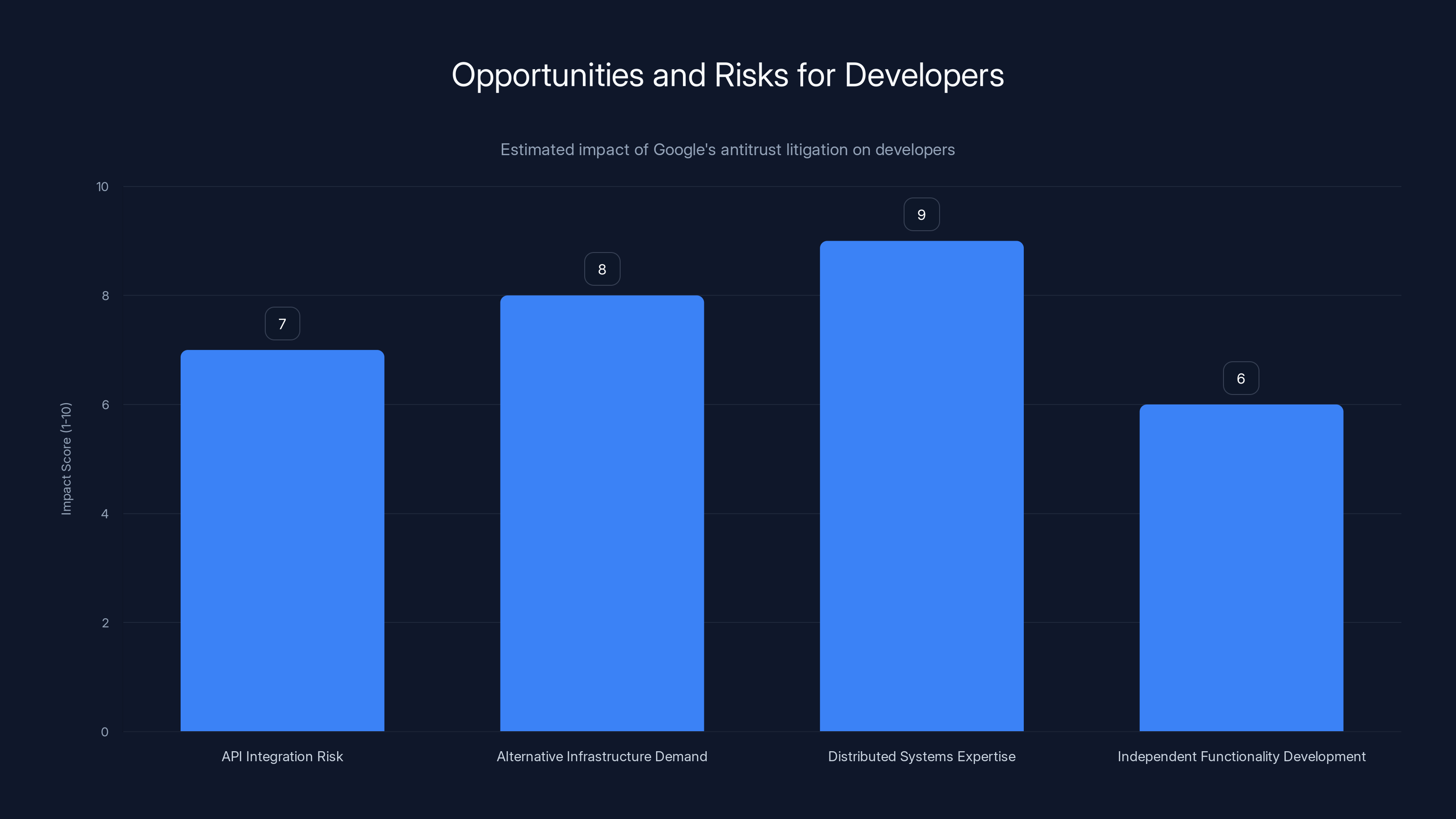

Developers face high risks with API integration changes but also see significant opportunities in alternative infrastructure and distributed systems expertise. Estimated data.

Google's Defense and Counterarguments

Google's Market Power Claims and Pro-Competitive Justifications

Google disputes that it possesses illegal monopoly power and argues that the ad tech markets remain robustly competitive. The company notes that multiple alternatives to Google Ad Manager exist, including App Nexus, Open X, Prebid, and others. Google also emphasizes that the ad tech landscape has experienced substantial innovation and that publishers have options for monetizing inventory beyond Google's ecosystem.

Google further argues that even if the company maintains large market share, this reflects consumer preference for superior products and services, not anticompetitive conduct. Google's ad serving platform offers substantial functionality, integration with Google's search and display advertising products, and competitive pricing. Publishers use Google's products because they provide genuine value, not because Google has illegally foreclosed competition.

On the specific claim of illegal tying, Google argues that technical integration between its ad server and exchange reflects legitimate efficiency. Publishers benefit from having their ad server and exchange work seamlessly together, from having unified reporting and data flow, and from being able to leverage Google's algorithmic tools to optimize ad placement and pricing. Rather than a form of coercive tying that forces publishers into anticompetitive arrangements, Google contends that its integration reflects pro-competitive product development.

Google's spokesperson Jackie Berté issued a statement defending the company's practices: "Advertisers and publishers have many choices and when they choose Google's ad tech tools it's because they are effective, affordable and easy to use." This statement encapsulates Google's core defense: the company's market position reflects competition on the merits, not anticompetitive abuse.

Legal and Factual Weaknesses in Google's Position

Despite Google's defenses, the company faces substantial legal and factual vulnerabilities. First, the court has already found that Google's market share in publisher ad serving substantially exceeds the level that creates presumptions of monopoly power. Google would need to rebut this presumption through evidence of pro-competitive justifications that outweigh the anticompetitive effects. The burden of proof shifts significantly once monopoly power is established.

Second, historical evidence of Google's conduct before major competitors were eliminated suggests intentional strategy to monopolize rather than incidental outcome of superior competition. Internal emails and business documents from Google competitors discussed in the trial showed instances where Google explicitly targeted competitors for elimination or exclusion. Such evidence of intent to monopolize is damaging to Google's "competition on the merits" narrative.

Third, the claim that competing products (like App Nexus, Open X, Prebid) remain viable alternatives is weakened by the fact that these competitors' market share has declined substantially over the past decade. If these alternatives were truly competitive, their market share would stabilize or grow, not diminish. The declining fortunes of competitors combined with evidence of Google's exclusionary practices points to anticompetitive causation rather than market preference for superior products.

Impact on Digital Advertising Ecosystem and Publishers

The Broader Implications for Publisher Business Models

The antitrust litigation against Google has profound implications for how publishers monetize content and structure their businesses. If Google is forced to divest ad tech operations or is prohibited from tying products together, the competitive dynamics of publisher monetization could shift dramatically. Publishers would gain leverage to negotiate better rates with multiple ad exchanges, competing exchanges would gain ability to achieve scale, and innovation in ad tech would likely accelerate as competitive pressure increases.

For publishers like The Atlantic, Vox Media, and the properties in Penske Media's portfolio, the antitrust litigation offers the possibility of recovering financial damages while simultaneously improving future business conditions. If remedies restore competition to publisher ad tech markets, these publishers would benefit both from direct damages recovery and from improved rates and competition in their ongoing ad tech relationships.

However, uncertainty about the litigation outcome and potential remedies creates risks for publishers in the short term. If publishers are building strategies around assumptions about Google's future market position or the competitive landscape, unfavorable antitrust outcomes could disrupt those plans. For this reason, savvy publishers are diversifying their advertising infrastructure, developing direct-sales relationships with major advertisers, and exploring alternative revenue models (subscriptions, memberships, sponsorships) that reduce dependence on programmatic advertising and Google's ad tech infrastructure.

The Role of Publishers in Resolving the Antitrust Crisis

Publishers occupy a complex position in Google's antitrust liability. They are simultaneously victims of anticompetitive conduct (as they claim in damages litigation) and beneficiaries of Google's technology (ad servers, analytics, search traffic). Publishers need Google's services, which creates an inherent tension. Even if publishers win damages claims against Google, they likely cannot eliminate their dependence on Google's ad server in the short or medium term.

This dynamic creates incentives for negotiated settlement. If Google and publishers can reach a settlement, the company could avoid uncertainty about damages exposure, and publishers could obtain immediate financial recovery plus contractual improvements to their relationship with Google. Several of the current lawsuits may ultimately settle rather than proceed to trial, particularly if damages calculations prove difficult to establish with precision or if remedies orders from Judge Brinkema appear likely to address publishers' core concerns.

From a regulatory perspective, publisher participation in damages litigation also strengthens the case for aggressive remedies. When major publishers testify that they depend on Google's monopoly infrastructure and have no viable alternatives, this testimony supports arguments for structural remedies rather than mere behavioral restrictions. Publishers essentially amplify the antitrust message that Google's market position is so dominant and exclusive that only structural change can restore competition.

Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Ad Tech

How AI is Reshaping Ad Tech Competition

Interestingly, while the antitrust litigation focuses on existing ad tech infrastructure, artificial intelligence is introducing new competitive dynamics that could reshape the entire advertising ecosystem. AI tools for targeting, optimization, creative generation, and performance prediction are enabling more efficient advertising and potentially reducing reliance on proprietary data accumulated through market dominance. This technological shift could gradually reduce the competitive advantages that flow from Google's current monopoly.

AI-powered tools that analyze advertiser intent and publisher audience composition could enable smaller, more specialized ad tech platforms to compete effectively without requiring the massive scale that currently disadvantages entrants. If AI can allow a startup ad tech company to match Google's optimization capabilities without accumulating years of data through billions of transactions, the competitive playing field could level substantially.

Conversely, Google's existing advantages in data and AI could enable the company to entrench dominance even if traditional ad tech markets become more competitive. Google's ability to train large language models on advertising data, to apply machine learning to optimization problems, and to integrate AI across its ecosystem could create new barriers that offset the reduced importance of traditional data accumulation advantages.

Regulatory Implications of Rapid Technological Change

The rapid pace of AI development in advertising creates complexity for both the antitrust litigation and potential remedies. If the remedies phase results in specific operational restrictions (like prohibiting certain uses of data or requiring interoperability), those restrictions could become obsolete if technology changes. Conversely, if remedies are structured as forced separation or divestiture, the separated entities might lack sufficient scale or resources to compete effectively in an AI-driven advertising landscape.

This dynamic creates pressure for swift resolution of the remedies phase before technology changes too rapidly. Judge Brinkema and the parties involved likely recognize that delays in the remedy determination could result in remedies that are either obsolete or inappropriate given evolved technology and market conditions. The court indicated expectations of remedy determinations within a reasonable timeframe, potentially 2025-2026.

Settlement Possibilities and Negotiation Scenarios

When and How Settlements Might Occur

While the current litigation appears positioned for trial and judgment, settlement remains possible at multiple junctures. Settlements typically occur when both parties identify significant risks and uncertainties that make trial unattractive relative to negotiated outcomes. For Google and the publisher plaintiffs, several factors could incentivize settlement:

From Google's perspective, settlement could provide certainty about financial exposure, reduce the risk of catastrophic remedies (like forced divestiture), avoid ongoing reputational damage from litigation, and allow the company to move forward with strategic planning. Google might be willing to agree to financial payments to publishers plus contractual improvements to the ad server and exchange relationships in exchange for dismissal of damages claims and reduced support for aggressive remedies in the DOJ case.

From the publishers' perspective, settlement could provide immediate financial recovery without risking that damages calculations fail or are overturned on appeal. Publishers might accept a settlement that includes both payment and contractual improvements to future ad tech relationships, recognizing that even a substantial settlement is preferable to litigation risk.

A plausible settlement scenario might involve Google agreeing to pay

The Role of the DOJ Remedy Decision

The Department of Justice's remedy decision in the antitrust case could significantly influence settlement negotiations. If Judge Brinkema indicates (through comments during the remedy phase) that she is likely to order structural remedies, Google's incentive to settle damages litigation increases substantially. A company facing forced divestiture of major business units might be highly motivated to resolve parallel damages litigation to reduce total legal and financial exposure.

Conversely, if the remedy phase indicates that behavioral restrictions (rather than structural separation) are likely, Google might be more willing to accept relatively modest settlements or might resist settlement more aggressively if the company believes behavioral remedies can be managed effectively.

The sequencing of the remedy decision relative to damages trial will therefore matter significantly. If the remedy decision occurs before damages trial concludes, that decision will influence settlement valuations and negotiations. Publishers and Google will recalibrate their positions based on the remedies that appear likely to be imposed.

Precedent and Lessons from Prior Tech Antitrust Cases

The Microsoft Precedent and How It Shapes Google Litigation

The most relevant historical precedent for Google's antitrust litigation is the landmark United States v. Microsoft case from the 1990s-2000s. That case involved allegations that Microsoft had leveraged its dominance in operating systems to monopolize the browser market by tying Internet Explorer to Windows. The case followed a similar arc: government prosecution found monopolization and illegal tying, private damages litigation followed, and remedies required substantial business restructuring.

The Microsoft case ultimately resulted in a settlement that included behavioral restrictions (Microsoft was prohibited from tying Internet Explorer to Windows) but stopped short of forcing the company to divest operating systems. However, the case changed Microsoft's market position substantially—the company's browser never achieved dominance despite being bundled with Windows, and new browsers like Firefox and later Chrome competed effectively.

Google's litigation follows this familiar pattern but with some differences. The ad tech market is more complex than browser markets, with multiple layers (publisher ad servers, exchanges, SSPs, DSPs) creating different competitive dynamics. Additionally, advertising markets are less visible to consumers than browser markets, meaning consumer sentiment and regulatory pressure may differ.

The Microsoft precedent suggests that even if Google avoids forced divestiture, the company may face restrictions that substantially alter its market position and profitability in ad tech. The case also demonstrates that once antitrust liability is established, private litigation and damages can continue for years, creating sustained financial and operational uncertainty.

Lessons from International Antitrust Actions Against Google

European antitrust cases against Google, including cases focused on search advertising and Android, provide additional precedent. The European Commission fined Google €2.42 billion (

Moreover, European regulatory actions often occur in parallel with private damages litigation in European courts. This international pattern suggests that Google faces a protracted global reckoning with antitrust enforcement, with multiple regulators and private parties pursuing related claims across different jurisdictions. The cumulative exposure across the United States, Europe, UK, and other jurisdictions could be substantially larger than any single case.

The international precedent also shows that regulatory agencies are increasingly willing to impose structural remedies when behavioral restrictions prove insufficient. If the US remedy phase follows the precedent of European cases, Google should expect more aggressive remedies than the company might prefer.

Implications for Developers and Marketing Professionals

For Developers: Infrastructure Changes and New Opportunities

Developers and technical professionals building advertising infrastructure face both risks and opportunities from Google's antitrust exposure. On the risk side, if Google is forced to divest or substantially restructure its ad tech business, integrations that developers have built with Google's APIs and products could change. Developers who have specialized extensively in Google's ad tech infrastructure might find their skills becoming less relevant if Google's market position shifts.

However, the antitrust litigation also creates opportunities for developers building alternative ad tech infrastructure. If regulatory remedies restore competition in publisher ad serving and ad exchanges, demand for alternative infrastructure increases substantially. Developers with expertise in distributed systems, data processing, and optimization algorithms needed for competitive ad tech platforms could find expanding opportunities.

For teams building marketing automation, analytics, or campaign management tools, the antitrust litigation creates uncertainty about Google's APIs and integrations but also opportunities to build independent functionality that doesn't depend on Google's infrastructure. Teams seeking cost-effective automation solutions might consider platforms like Runable that offer AI-powered workflow automation without dependence on proprietary Google ad tech APIs.

For Marketing and Advertising Teams

Marketing professionals managing digital advertising campaigns face near-term stability but medium-term uncertainty. Google's dominance in ad tech remains secure through at least 2025-2026, so advertisers can continue investing in Google Ads and related platforms without immediate disruption. However, the antitrust litigation creates long-term uncertainty about pricing, features, and Google's role in the advertising ecosystem.

Sophisticated advertisers are beginning to build more diversified advertising infrastructure, reducing dependence on Google's platforms while hedging against potential future changes. This approach involves:

- Testing alternative DSP (demand-side) platforms like Amazon Advertising, The Trade Desk, or regional alternatives

- Developing first-party data strategies and customer data platforms to reduce reliance on Google's audience targeting

- Building direct relationships with publishers rather than relying entirely on programmatic exchanges

- Exploring emerging channels and platforms (including AI-powered optimization tools) as potential new advertising channels

Advertisers that maintain healthy diversification are best positioned to adapt if antitrust remedies change Google's market position or pricing.

Looking Forward: 2025-2026 Timeline and Key Milestones

Critical Dates and Upcoming Decisions

The antitrust litigation and damages cases follow a rough timeline:

Late 2025: Judge Brinkema expected to issue remedy recommendations in the DOJ case, potentially including detailed requirements for how Google must restructure its ad tech business or change operational practices. This decision will have significant implications for damages litigation.

2025-2026: Damages trials in individual publisher and ad tech cases expected to proceed if settlements don't occur. These trials will involve detailed economic testimony about damages calculations, publisher testimony about competitive harm, and technical expert testimony about market mechanics.

2026: Potential appeals of Brinkema's remedy decision, with final appeals court ruling on appropriate remedies. This ruling becomes final unless Google seeks further appeals to the Supreme Court (unlikely to be granted).

2026-2027: Final damages judgments in individual cases, followed by potential appeals. Some cases may settle during this period if damages are becoming clarified through trial decisions in early cases.

2027 and beyond: Implementation of remedies. If structural changes are required, Google would begin divesting ad tech assets or separating business units. This transition period could extend for years and would create substantial business disruption.

The Importance of the Remedy Decision

The most critical upcoming decision is Judge Brinkema's remedy ruling in the DOJ case. This decision will determine whether Google faces manageable behavioral restrictions or transformative structural changes. The remedy decision will influence:

- Google's settlement strategy in damages cases

- Publishers' willingness to accept settlements or pursue full litigation

- Ad tech competitors' strategies for building alternative infrastructure

- Advertiser decisions about diversifying ad tech platforms

- Regulatory actions by other jurisdictions (US states, international regulators)

Given the significance of the remedy decision, all parties are likely to present extensive arguments about appropriate remedies. The court will hear technical testimony about how to implement specific remedies, economic testimony about efficiency implications, and policy arguments about the public interest. The remedy phase, while less visible than the liability phase, may ultimately prove more important in determining how Google's business evolves.

FAQ

What is the core antitrust violation that Google committed?

Google illegally monopolized the publisher ad server market (used by publishers to manage advertising inventory on their websites) and the ad exchange market (used to conduct real-time auctions for advertising inventory). The company tied these two products together, making it extremely difficult for publishers to use Google's dominant ad server with competing ad exchanges. This tying arrangement leveraged Google's monopoly power in ad serving into dominance in exchanges and prevented competition in both markets.

How did Google's monopoly harm publishers and advertisers?

Google's monopoly enabled the company to suppress the prices it paid publishers for advertising inventory. Without viable alternatives, publishers had limited negotiating power and could not access competing ad exchanges that might have offered better rates. Publishers like The Atlantic, Vox Media, and Penske Media estimate they lost hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue due to artificially depressed rates. Advertisers faced reduced competition on the publisher-supply side, while publisher-side platforms faced barriers to competing with Google's integrated offering.

What damages are publishers seeking from Google?

Publishers are seeking financial compensation for the suppressed revenue they claim resulted from Google's monopoly practices. Specific damage amounts vary by case but generally involve calculations of the difference between actual rates publishers received and the competitive rates that would have prevailed absent Google's anticompetitive conduct. Damages could range from hundreds of millions to billions of dollars across all publisher cases combined. Some cases also seek treble damages (three times actual damages) under antitrust statutes that provide enhanced penalties.

What remedies might Judge Brinkema order in the DOJ case?

Potential remedies range from behavioral restrictions to structural separation. Behavioral remedies might include prohibiting Google from tying products together, requiring data sharing with competitors, or preventing Google from preferencing its own exchange within its ad server. Structural remedies could require Google to divest its ad tech business entirely or separate different ad tech products into independent companies. The remedy decision, expected in late 2025, will determine how substantially Google's business must change to restore competition.

How do these lawsuits compare to other antitrust cases against technology companies?

Google's antitrust exposure is comparable to the historic Microsoft case from the 1990s-2000s, which also involved allegations that a dominant technology company had illegally leveraged market power through tying arrangements. Like Microsoft, Google faces both government prosecution and private damages litigation. However, Google's cases are more complex because ad tech involves multiple interconnected markets rather than the simpler browser-versus-OS dynamic in the Microsoft case. International comparisons to European Commission cases against Google show that regulators are willing to impose multi-billion-dollar fines and substantial business restrictions on Google.

When will damages be decided and how much might Google owe?

Damages trials are expected to proceed through 2025-2026 if settlements don't occur. Final judgments could come in 2026-2027, with appeals extending the timeline further. Total damages exposure across all publisher and ad tech cases could range from $2-5 billion or potentially higher depending on how broadly courts define the class of injured parties and how damages are calculated. The remedy decision in the DOJ case will influence settlement valuations and damage calculations in private cases.

Could Google settle these lawsuits and on what terms?

Settlement is possible at multiple points in the litigation. A plausible settlement scenario might involve Google agreeing to pay

What is the relationship between the government DOJ case and the private damages lawsuits?

The private damages lawsuits leverage findings from the government's successful antitrust prosecution. The court's determination that Google monopolized publisher ad serving and illegally tied products provides a strong foundation for private plaintiffs to argue damages from the same conduct. Essentially, the government bore the burden of proving liability; private parties now use those findings to pursue damages recovery. The remedy decision in the DOJ case will influence damage settlements by clarifying what business changes Google will be forced to make.

How could AI and technology changes affect this litigation?

Artificial intelligence is introducing new competitive dynamics in ad tech that could reshape markets independently of antitrust remedies. AI-powered targeting and optimization tools might enable smaller competitors to compete without the massive data advantages that currently flow from Google's monopoly. However, Google's existing AI capabilities and data advantages could enable the company to entrench dominance even in an AI-driven landscape. Regulatory changes may need to account for rapid technological evolution when determining appropriate remedies.

What should publishers and advertisers do in response to this litigation?

Publishers should explore diversifying their ad tech infrastructure to reduce dependence on Google, develop direct advertiser relationships, and pursue alternative revenue models beyond programmatic advertising. Advertisers should test alternative demand-side platforms, build first-party data strategies, and avoid becoming overly dependent on Google's advertising tools. Teams seeking cost-effective automation and workflow tools might explore alternatives like AI-powered platforms that offer flexible integration without vendor lock-in. All parties should monitor remedy developments and be prepared to adjust strategies based on antitrust outcomes.

Are other tech companies facing similar antitrust challenges?

Yes, the antitrust environment for large technology companies has intensified substantially. Amazon faces scrutiny over its marketplace practices, Apple faces challenges regarding its App Store policies, and Meta faces investigations regarding its acquisition strategy and competitive practices. Google specifically faces antitrust actions across the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and numerous other jurisdictions. The cumulative effect is a global reckoning with how dominant technology platforms leverage market position across interconnected services.

Conclusion

Google's mounting antitrust exposure represents one of the most significant legal challenges facing major technology companies in the 2020s. The Justice Department's successful prosecution establishing that Google monopolized publisher ad serving and illegally tied products together has opened the floodgates to private damages litigation from major publishers including The Atlantic, Vox Media, and Penske Media. These lawsuits collectively represent billions of dollars in potential liability and could fundamentally restructure how Google operates its advertising technology business.

The implications extend far beyond Google's balance sheet. Publishers struggling with revenue pressures are pursuing damages claims that could generate resources for journalism investment. Ad tech competitors that faced barriers to scaling their businesses are seeking damages for competitive harm. The broader advertising ecosystem is confronting fundamental questions about market structure, competition, and the appropriate role of dominant platforms in facilitating transactions.

Central to the litigation's trajectory is Judge Leonie Brinkema's upcoming remedy decision in the DOJ case. This decision—expected in late 2025—will determine whether Google faces manageable behavioral restrictions or transformative structural changes including potential divestiture of its ad tech business. The remedy decision will influence settlement valuations in damages cases, competitive strategies by ad tech companies, and advertiser decisions about platform diversification.

The path forward involves several critical junctures. Damages trials will present detailed economic evidence about the pricing effects of Google's monopoly practices. Settlement negotiations may resolve some cases, reducing litigation burden on all parties. Appeals will test the legal reasoning underlying the initial monopolization findings. Implementation of remedies will require substantial Google business restructuring regardless of whether changes are behavioral or structural.

For stakeholders across the advertising ecosystem—publishers, advertisers, ad tech companies, and developers—the antitrust litigation creates both uncertainty and opportunity. The uncertainty stems from unclear remedies and evolving competitive dynamics. The opportunity flows from the potential restoration of competition in advertising infrastructure markets that have become overly concentrated. Teams seeking to navigate this environment should monitor litigation developments, diversify technology dependencies, and explore alternative platforms and services that offer flexibility without vendor lock-in.

The antitrust challenges to Google's ad tech business ultimately reflect broader questions about appropriate market structure in digital advertising and the extent to which dominant platforms can leverage dominance across interconnected services. The outcomes of these cases will shape not only Google's future but also competitive dynamics and innovation incentives across digital advertising for years to come.

Key Takeaways

- Federal court found Google illegally monopolized publisher ad server and ad exchange markets

- The Atlantic, Vox Media, and Penske Media are pursuing damages claims seeking billions in compensation

- Google's illegal tying of ad server to exchange eliminated competing platforms and suppressed publisher revenues

- Potential remedies range from behavioral restrictions to forced structural separation of Google's ad tech business

- Ad tech providers like PubMatic and OpenX also face barriers from Google's monopoly practices

- Publishers lost hundreds of millions in annual revenue due to artificially depressed advertising rates

- Judge Brinkema's remedy decision in late 2025 will determine scope of business changes Google must implement

- Settlement negotiations may resolve individual damages cases and reduce overall litigation burden

- Global antitrust enforcement against Google creates cumulative pressure for business restructuring

- Publishers should diversify ad tech dependencies to reduce vulnerability to monopoly practices