The Hidden Vulnerability in Your Wireless Headphones

You probably don't think much about how your wireless headphones connect to your phone. You tap a button, see them pop up on your device, and they just work. It's seamless. It's convenient. But that convenience comes with a serious security cost that most people have no idea exists.

Google's Fast Pair technology is designed to make connecting Bluetooth devices incredibly easy. Instead of manually digging through settings and pairing menus, Fast Pair uses Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) broadcasts to automatically discover and connect your headphones, smartwatches, and other accessories in seconds. The technology is smart. It's also vulnerable in ways that security researchers have only recently exposed.

The core problem is this: Fast Pair relies on unencrypted Bluetooth broadcasts that any device within range can detect and intercept. A determined attacker doesn't need your phone. They don't need to be standing next to you. They just need to be close enough to receive these broadcasts, and they can figure out exactly what devices you're carrying, where you are, and even follow your movements over time. This isn't theoretical. Security researchers have already demonstrated working exploits.

What makes this particularly concerning is the scale of the vulnerability. Fast Pair isn't a niche feature used by a small percentage of people. It's baked into millions of Android devices and works with hundreds of millions of wireless accessories from companies like Google, Sony, JBL, and Beats. If you own a pair of modern wireless headphones and an Android phone, you're almost certainly affected.

The vulnerability doesn't require a sophisticated attack or specialized equipment. A determined attacker with basic radio knowledge and off-the-shelf tools can conduct the attack. They can track individuals, build profiles of their movements and habits, and potentially cross-reference this data with other information to identify targets. This is the kind of privacy breach that happens silently, without your knowledge, and without any indication that something is wrong.

In this guide, we're going to dig deep into how this vulnerability works, why it exists, what the real-world risks are, and most importantly, what you can do to protect yourself right now. Understanding these threats isn't about becoming paranoid. It's about making informed decisions about the devices you use every day.

TL; DR

- Google Fast Pair broadcasts device location data in unencrypted Bluetooth signals that any nearby device can intercept and track

- Attackers need minimal equipment to conduct the attack: just a software-defined radio receiver and basic knowledge of Bluetooth protocols

- The vulnerability affects millions of devices including headphones, smartwatches, and other accessories from major manufacturers like Sony, JBL, Beats, and Google

- Your location patterns can be mapped by tracking Fast Pair signals over time, revealing where you live, work, and spend your time

- Disable Fast Pair in your device settings or turn off Bluetooth when not actively connecting devices to eliminate this specific attack vector

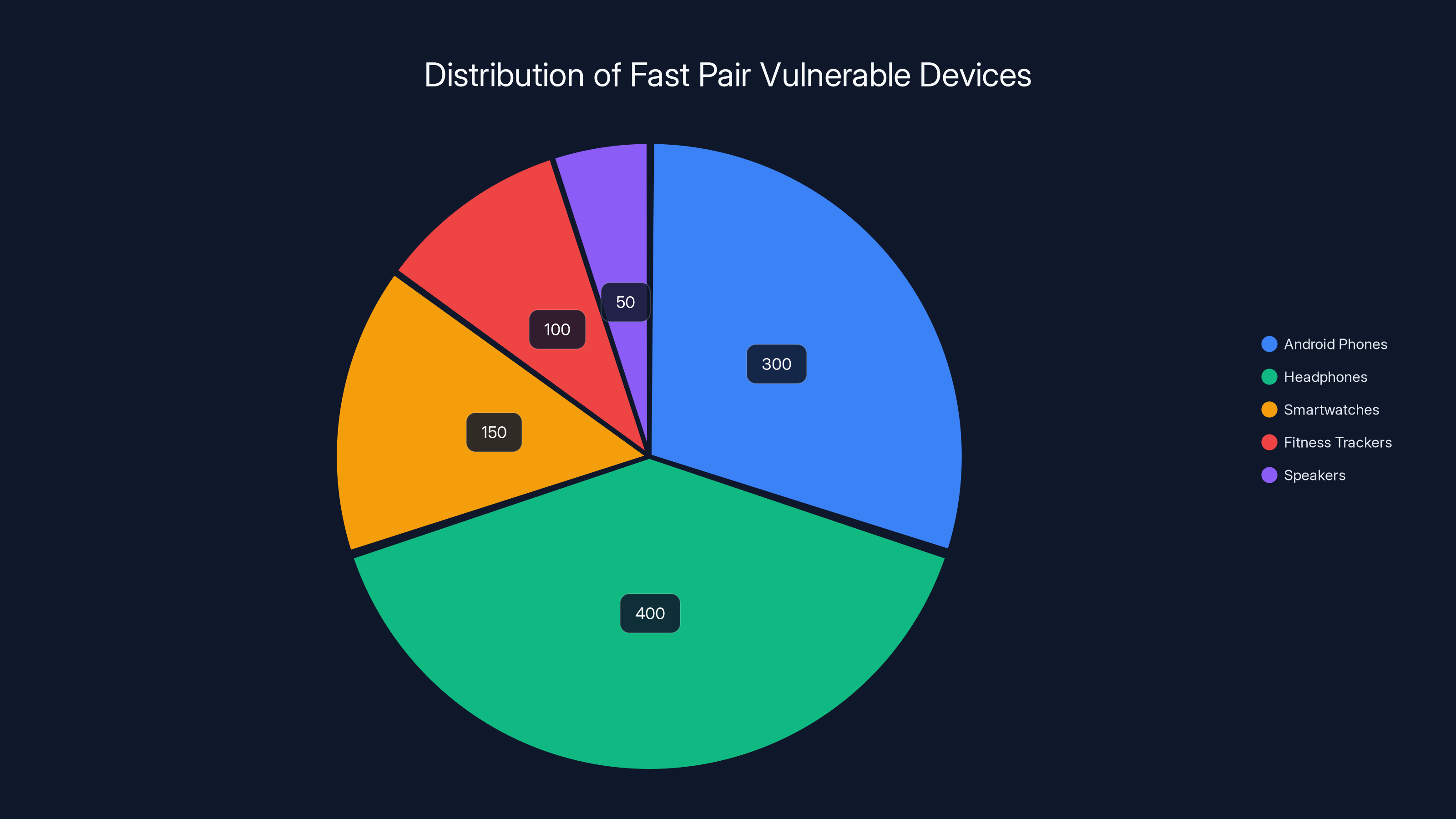

Estimated data shows that headphones and Android phones make up the largest share of devices vulnerable to the Fast Pair tracking attack, with hundreds of millions of devices potentially affected.

What Is Google Fast Pair and How Does It Work?

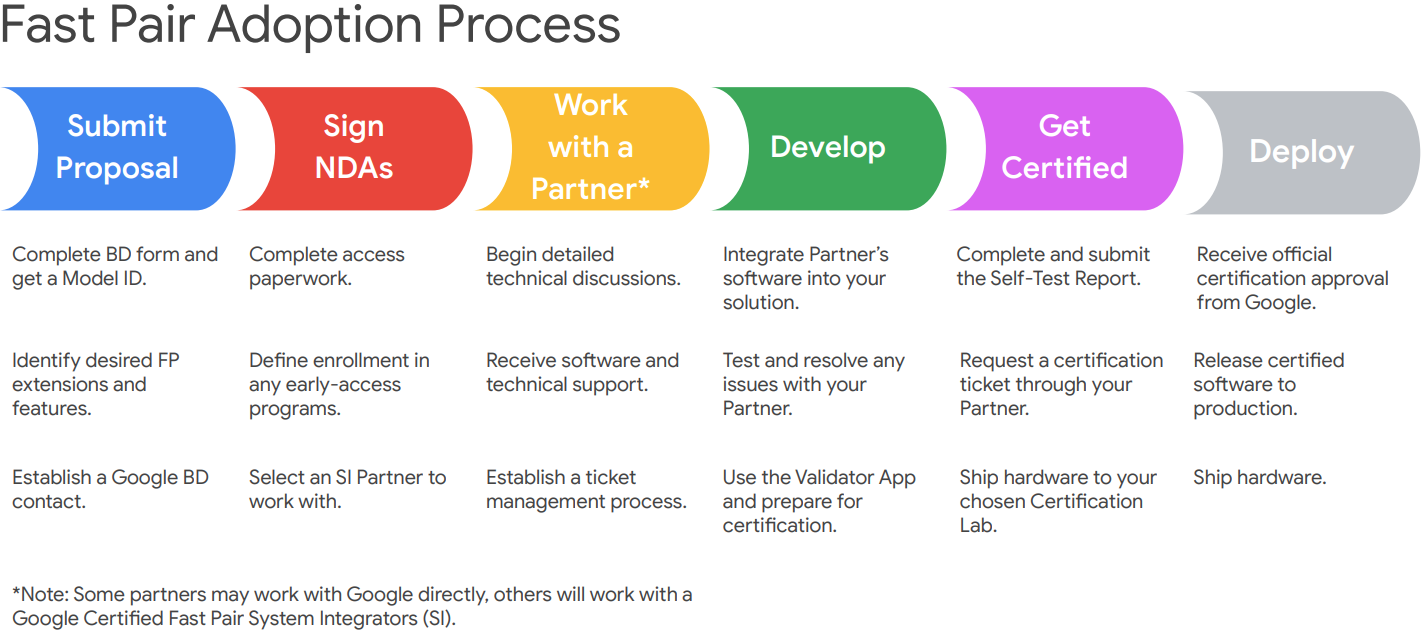

Google Fast Pair launched in 2019 as a solution to one of Bluetooth's most frustrating problems: the pairing process was unnecessarily complicated. Before Fast Pair, connecting a Bluetooth device to your phone meant diving into settings menus, searching for your device in a list, and manually entering PIN codes. It was clunky and error-prone.

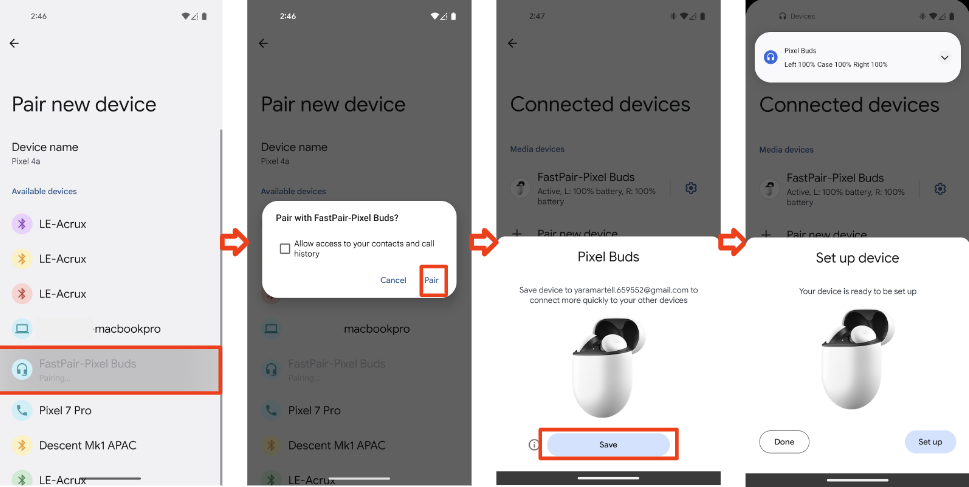

Fast Pair changed that by automating discovery and pairing. When you turn on compatible headphones near an Android phone, your phone automatically detects them through special Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements. A prompt appears on your screen asking if you want to connect. Tap yes, and you're done. The pairing happens instantly without any manual configuration.

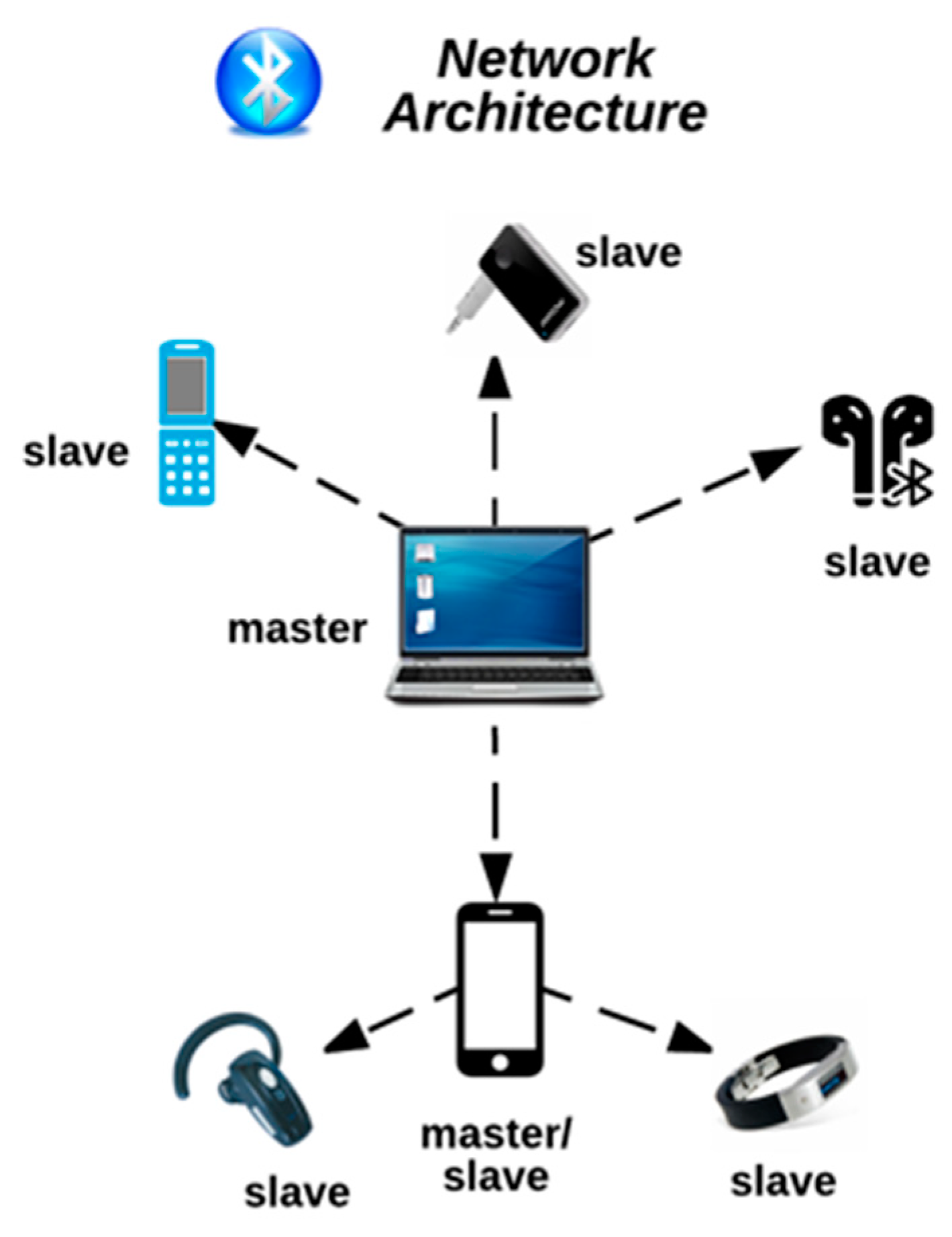

Under the hood, Fast Pair works by having compatible devices broadcast their presence using Bluetooth Low Energy. These broadcasts contain identifying information about the device, including its model number and hardware address. When your Android phone receives these broadcasts, it recognizes them as Fast Pair compatible devices and displays a connection prompt. This approach is user-friendly but exposes a critical security gap.

The vulnerability exists because these initial Bluetooth Low Energy broadcasts aren't encrypted. Any device with a Bluetooth receiver can pick up these signals and read the identifying information. This means a nearby attacker can learn exactly what type of headphones you're wearing, what smartwatch you have on your wrist, and roughly how far away you are based on signal strength. When combined with other data points, this information can be used to track your movements and location over time.

Google didn't design Fast Pair with malicious tracking in mind. The engineers who built it were focused on solving a real user experience problem. But like many convenience features, the ease of use came at the expense of security. The Bluetooth Low Energy broadcasts that make Fast Pair possible don't inherently protect against eavesdropping. The assumption was that this information wasn't sensitive enough to require encryption. That assumption turned out to be wrong.

Since Fast Pair's introduction, the technology has become incredibly widespread. Almost every major wireless headphone manufacturer has adopted it, including Sony, JBL, Beats, Bose, and Sennheiser. The protocol has also expanded beyond headphones to include smartwatches, fitness trackers, car keys, and other accessories. This means the vulnerability isn't limited to just one category of devices. Any Fast Pair compatible device you carry becomes a potential tracking beacon.

The technology is deeply integrated into the Android ecosystem. Most Android devices from manufacturers like Samsung, Google, and One Plus have Fast Pair support built in. This isn't something you explicitly chose to enable. It comes enabled by default on modern Android phones. For most users, this is a convenience feature they probably appreciate. For security researchers and privacy advocates, it's a privacy disaster waiting to happen.

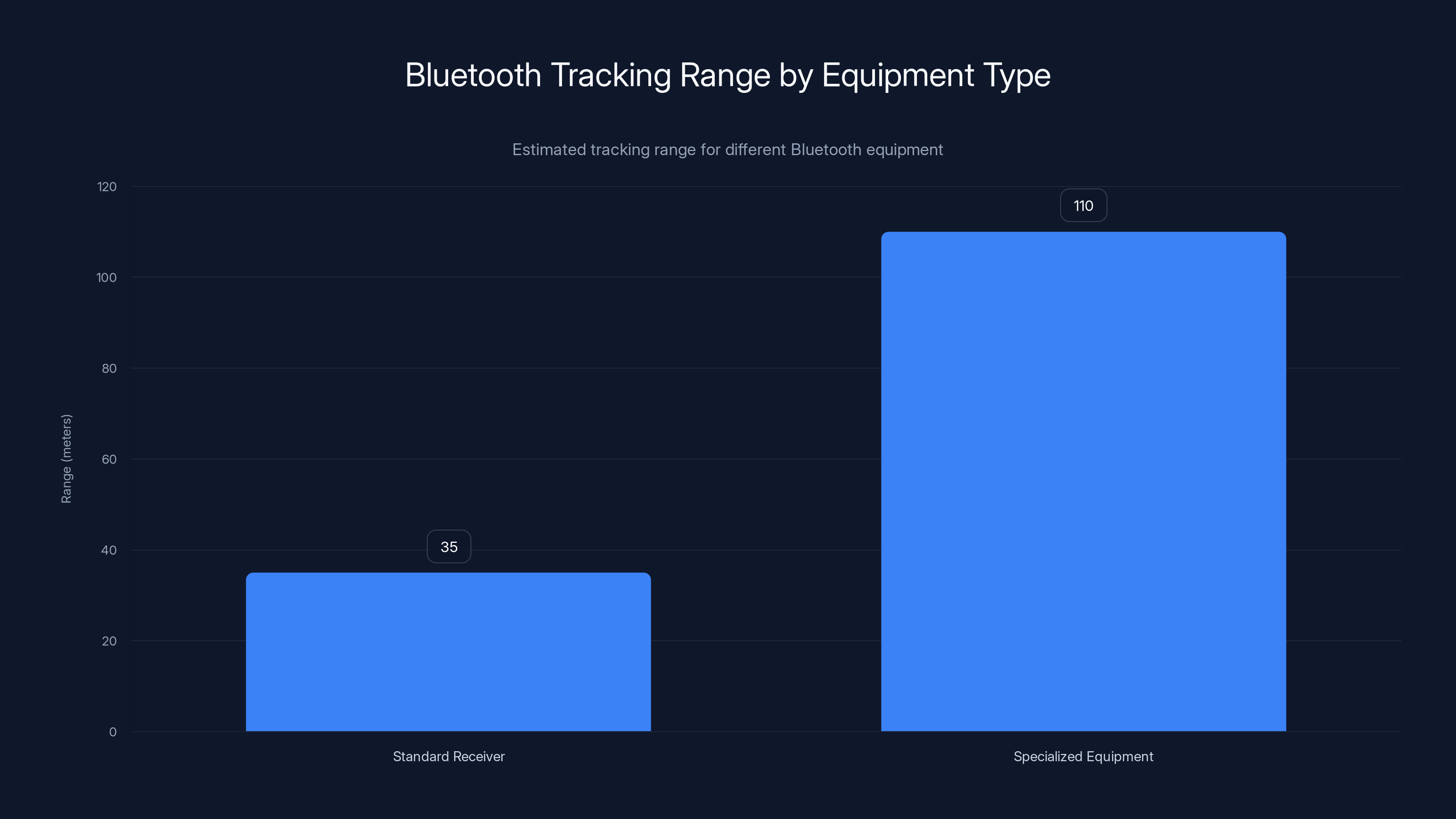

Standard Bluetooth receivers typically track up to 35 meters, while specialized equipment can extend the range to over 100 meters. Estimated data.

Understanding the Security Vulnerability

The fundamental security flaw in Fast Pair comes down to how Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements work and what information is exposed in those advertisements. When a compatible device wants to broadcast its presence for Fast Pair pairing, it sends out repeated BLE advertisement packets. These packets contain the device's hardware address (MAC address), the model number of the device, and sometimes additional metadata about battery status or device capabilities.

The critical weakness is that these advertisement packets are sent in the clear, with no encryption whatsoever. A Bluetooth receiver within range can pick up these packets and read their contents directly. There's no authentication mechanism, no signing, no way to verify that the packets are legitimate or that only authorized devices should see them. This is fundamentally different from how the actual pairing and connection process works, which does use encryption and authentication.

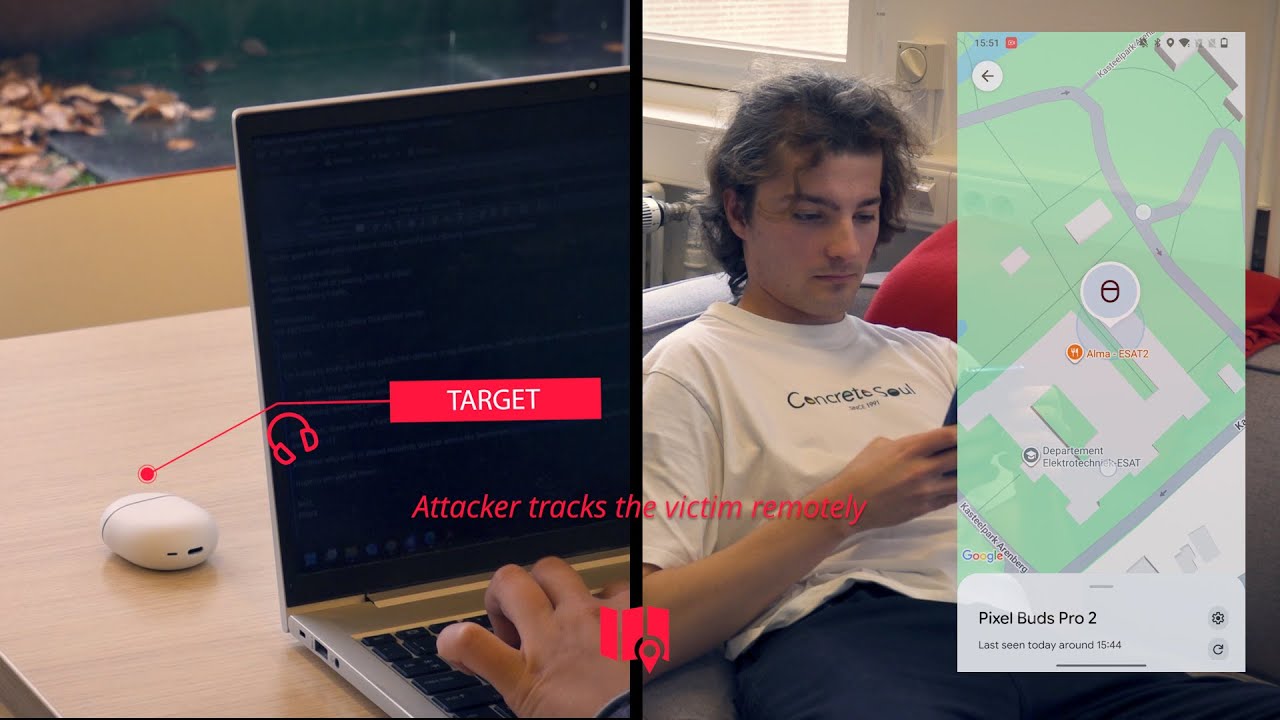

Security researchers demonstrated this vulnerability by building a simple tracking system using a software-defined radio device. These are inexpensive radio receivers that can be programmed to listen to specific frequencies. Using a modified version of the open-source Bluetooth Low Energy stack, researchers set up a receiver to scan for Fast Pair broadcasts from a distance. They were able to reliably detect and identify specific devices from several meters away and track their movements as the target walked around an area.

The attack works because each Bluetooth device has a unique hardware address (MAC address) that rarely changes during normal operation. Even though this address is meant for local network communication, it serves as a unique identifier that can be used to track a specific device over time. When you walk past a location where someone has set up a tracking receiver, they can log your hardware address and timestamp. By setting up multiple receivers across different locations, an attacker can map out your movement patterns.

The implications of this vulnerability are significant when you think through a few scenarios. Imagine an attacker sets up a tracking receiver in a building's lobby. Over several weeks, they track every person entering and exiting the building based on the Bluetooth devices they carry. They start to build a profile of which employees work in the building, roughly when they arrive and leave, and which employees frequently leave at unusual times. This information could be used for stalking, corporate espionage, or other malicious purposes.

Or consider a more targeted scenario: a stalker wants to track an ex-partner they've separated from. Instead of installing a tracking app on the target's phone (which would require physical access), they could simply carry a Bluetooth tracking receiver. Whenever the target comes within range with their headphones or smartwatch, the attacker's device logs their location. The target would have no idea they're being tracked because this attack leaves no traces and requires no installation of software on their phone.

What makes this vulnerability particularly insidious is that it works regardless of whether the person is actually connecting to the attacker's device. The tracking is completely passive. The target's phone doesn't need to receive the malicious broadcast. The attacker simply needs to receive the legitimate Fast Pair broadcasts that the target's devices are sending out.

How the Exploit Works in Practice

Let's walk through a concrete example of how this exploit actually works, step by step. This will help you understand the practical mechanics of the vulnerability and why it's more than just a theoretical concern.

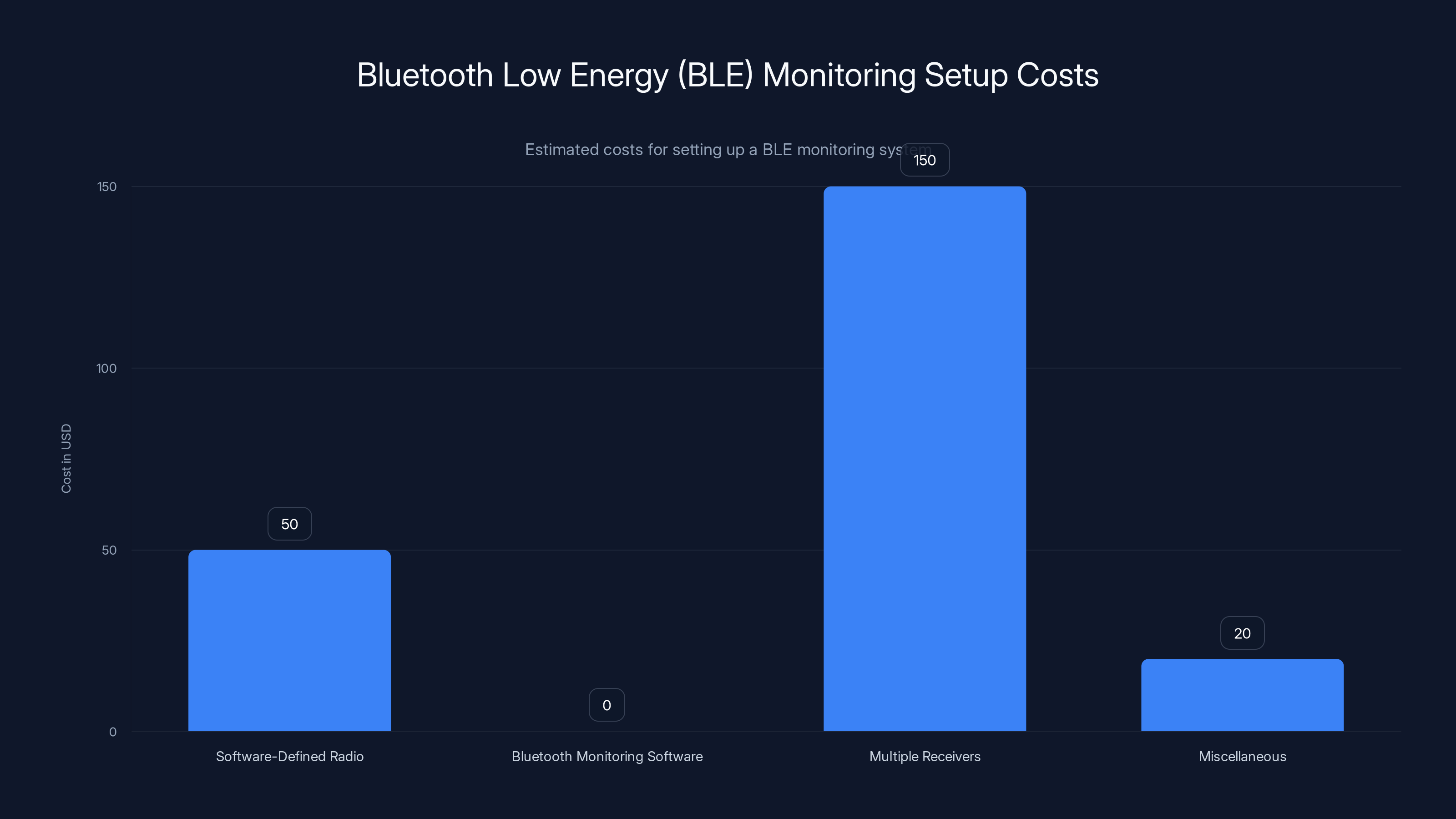

First, an attacker acquires a software-defined radio device. These are relatively inexpensive pieces of hardware, with capable models available for under $50. The most popular option is the USRP (Universal Software Radio Peripheral) or similar devices that can receive radio signals across a wide range of frequencies. These devices have been available for years and are commonly used for legitimate research and education. An attacker then loads software designed to monitor Bluetooth Low Energy broadcasts, such as modified versions of open-source Bluetooth stacks.

Next, the attacker positions their receiver in a location where they want to monitor device traffic. This could be a café, a public library, an apartment building, or any location where people gather. The key requirement is line of sight to the Bluetooth devices they want to track. BLE has a maximum range of about 100 meters in open space, but in buildings it's typically 20-50 meters depending on walls and obstacles. The attacker's receiver begins passively listening for any Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements.

When someone carrying compatible wireless headphones or a smartwatch walks into range, their device continuously broadcasts Fast Pair packets at regular intervals. The attacker's receiver picks up these packets and logs several pieces of information: the device's hardware address (MAC address), the timestamp of the detection, the signal strength (which indicates approximate distance), and any other metadata in the advertisement.

If the attacker wants to track a specific target over a longer period, they can deploy multiple receivers in different locations. When the tracked device passes near each receiver, its presence is logged. By combining data from multiple sensors, the attacker can build a complete movement profile. They can determine where the target lives (by seeing their devices arrive and stay at a particular location during night hours), where they work, which routes they take, and where they spend leisure time.

The beauty of this attack from an attacker's perspective is that it requires no interaction with the target's phone. The target doesn't click anything, doesn't approve any connections, doesn't receive any notification. The attack is completely passive and invisible. The tracking happens at the Bluetooth layer, before any application on the phone even knows communication is occurring.

Moreover, the attack leaves no digital footprint on the target's device. There's no record in app logs, no unusual network traffic, no indication that anything suspicious happened. The only evidence would be in the attacker's equipment, which they control. This makes the attack extremely difficult to detect and nearly impossible to prove after the fact.

The attack also works regardless of the target's phone OS version, security patches, or which Android security updates they've installed. The vulnerability is in the Fast Pair protocol itself, which is relatively static. Google could patch the protocol, but that would require firmware updates to millions of compatible Bluetooth devices from different manufacturers. Getting all those devices to install a firmware update is practically impossible, especially for older or lower-end devices.

Another concerning aspect is that the attack works against multiple categories of devices simultaneously. Your phone can detect one set of Fast Pair broadcasts from your headphones, your smartwatch is broadcasting its presence with different identifier, and your fitness tracker is broadcasting yet another. An attacker can track all of these signals and build a more complete picture of your movements and activities. If you're wearing multiple devices from different manufacturers, you've essentially multiplied your tracking surface area.

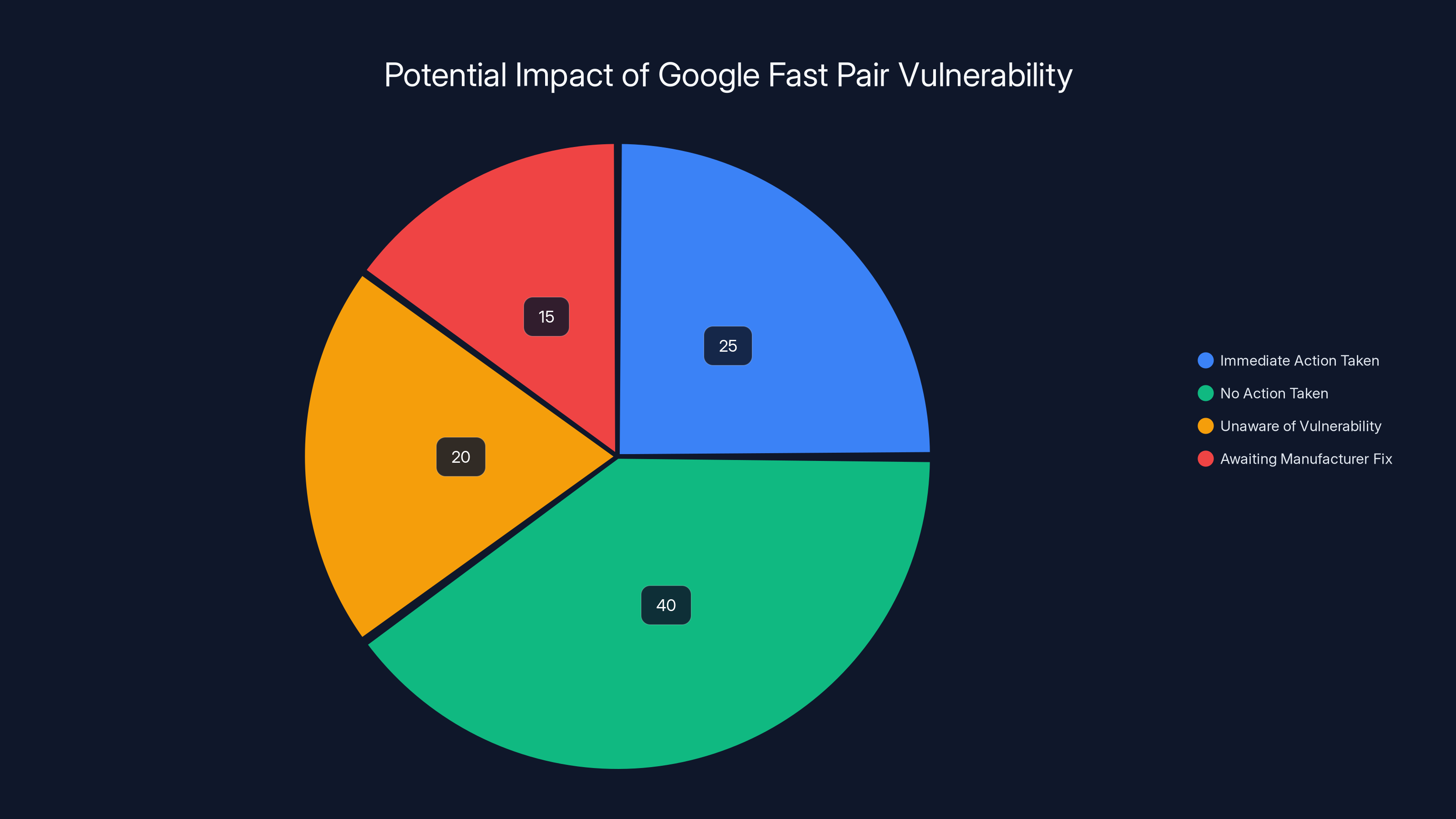

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of users are unaware of the vulnerability, while others are taking immediate action or awaiting fixes from manufacturers.

Real-World Attack Scenarios and Threat Modeling

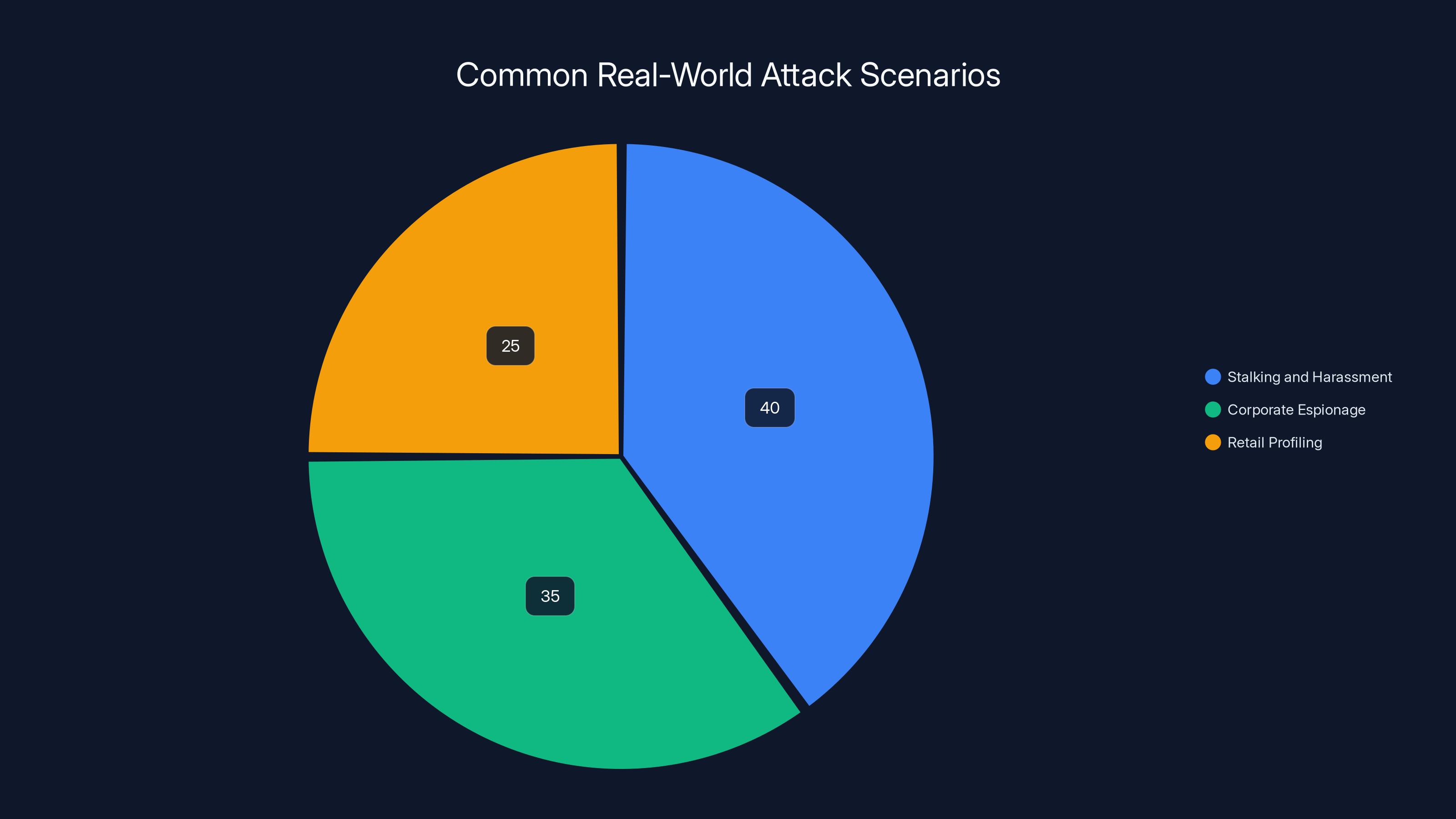

To understand why this vulnerability matters, it helps to think through specific scenarios where this attack could be used. These aren't theoretical possibilities or contrived examples. Security researchers and law enforcement experts have identified these as real-world threats that are likely already being exploited by malicious actors.

Stalking and Harassment: The most direct application of this vulnerability is stalking. An attacker with knowledge of the target's devices (which they might know from a previous relationship or from seeing the person use them) can track their movements over long periods. Unlike GPS tracking, which requires either access to the target's phone or a device hidden in their clothing, this attack only requires the target to be carrying their normal Bluetooth devices. A stalker could track whether their target is home, at work, at a friend's house, at a gym, or at any other location by simply maintaining a receiver in proximity. The target would have absolutely no way to detect this surveillance.

Corporate Espionage: Competitors could stake out a company's office building and track the movement patterns of specific executives or engineers. By identifying which employee badges or Bluetooth devices are in the building at what times, an attacker can determine work schedules, identify key personnel, and potentially identify engineers working on sensitive projects. If an engineer frequently visits a particular conference room at specific times, an attacker might infer that important meetings are happening then.

Retail and Consumer Profiling: Retailers could deploy tracking receivers throughout a shopping mall to track customers' movements and build profiles of shopping behaviors. They could identify high-value customers, track which stores they visit, how long they spend in each location, and which products they spend time examining. This information could be used for targeted marketing or could be sold to third parties. Customers would have no idea they were being tracked.

Law Enforcement Tracking: Without proper legal oversight, law enforcement agencies could deploy tracking receivers to monitor the movements of specific individuals without a warrant or court order. Unlike traditional surveillance, which requires visible cameras or undercover officers, Bluetooth tracking is completely invisible and passive. The target would have no way to know they're under surveillance.

Social Engineering and Credential Harvesting: An attacker could use tracking information to identify patterns in someone's life (regular locations, typical times of day, common routes) and use this information to conduct targeted social engineering attacks. For example, knowing that a person regularly visits a specific coffee shop at 8 AM, an attacker could position themselves there with a fake wifi network. Or knowing someone's commute pattern, they could attempt to intercept them during vulnerable moments.

These scenarios aren't hypothetical. Journalists covering sensitive stories, activists involved in social movements, and domestic abuse survivors are all potential targets for this kind of surveillance. The threat is particularly serious because the tracking is so difficult to detect and so challenging to prove.

The threat model becomes even more concerning when you consider that the attacker doesn't need to be technically sophisticated. While setting up the initial tracking infrastructure requires some technical knowledge, the actual process of tracking becomes completely automated once the system is in place. An attacker could set up multiple receivers, leave them unattended to collect data for months or years, and periodically retrieve the collected logs.

Technical Details: Why This Vulnerability Exists

The vulnerability in Fast Pair stems from fundamental design choices made when the protocol was developed. To understand why this happened, it helps to look at the constraints and priorities that shaped Fast Pair's design.

Bluetooth Low Energy was designed from the ground up to be power-efficient. A device broadcasting with BLE can run for months or even years on a single battery charge. To achieve this efficiency, BLE uses much smaller advertisement packets than classic Bluetooth, and it allows devices to spend most of their time sleeping rather than actively transmitting. The trade-off for this efficiency was that BLE advertisements are broadcast unencrypted and visible to anyone in range.

When Google designed Fast Pair, the priority was user experience. The protocol needed to work out of the box with minimal configuration. Requiring encryption or complex pairing procedures would undermine this goal. The assumption was that the information in Fast Pair advertisements (primarily device type and model number) wasn't sensitive. What could an attacker do with knowing that someone carries Sony WH-1000XM4 headphones? Not much, until you add the tracking component. Then suddenly, that seemingly innocuous information becomes a persistent location signal.

The architecture of Fast Pair also plays a role. Fast Pair operates at the Bluetooth level, below the application layer. This means the entire pairing process happens before any network-based security or encryption can be applied. The assumption was that Bluetooth's short range would provide inherent security. If an attacker is close enough to receive Bluetooth signals, they're probably close enough to physically attack you anyway, the thinking went. But as demonstrated by researchers, the effective range of attacks using software-defined radios extended this assumption beyond its breaking point.

Another technical factor is the role of identifiers in the Fast Pair protocol. To enable the Fast Pair feature to work reliably, devices need persistent identifiers that remain the same across different pairing sessions. This allows your phone to recognize your specific Sony headphones, for example, rather than treating them as generic headphones. But this persistence is exactly what enables tracking. If the device identifier changed with every broadcast, tracking would be impossible. But making it change would break the core functionality of Fast Pair.

Google has been aware of these privacy concerns for some time. In more recent iterations of Fast Pair, Google added some privacy improvements. For example, they introduced randomized MAC addresses for some advertisement packets and added certificate-based authentication to improve the security of the pairing handshake. However, these improvements don't fully solve the tracking problem. The fundamental architecture of unencrypted location broadcasts remains, and older devices that don't support the updated protocol still have the original vulnerability.

The challenge for Google is that fixing this vulnerability comprehensively would require changes to the protocol itself, and then getting all compatible devices from dozens of manufacturers to implement those changes. This is an enormous coordination problem. In the meantime, millions of devices remain vulnerable to tracking exploits.

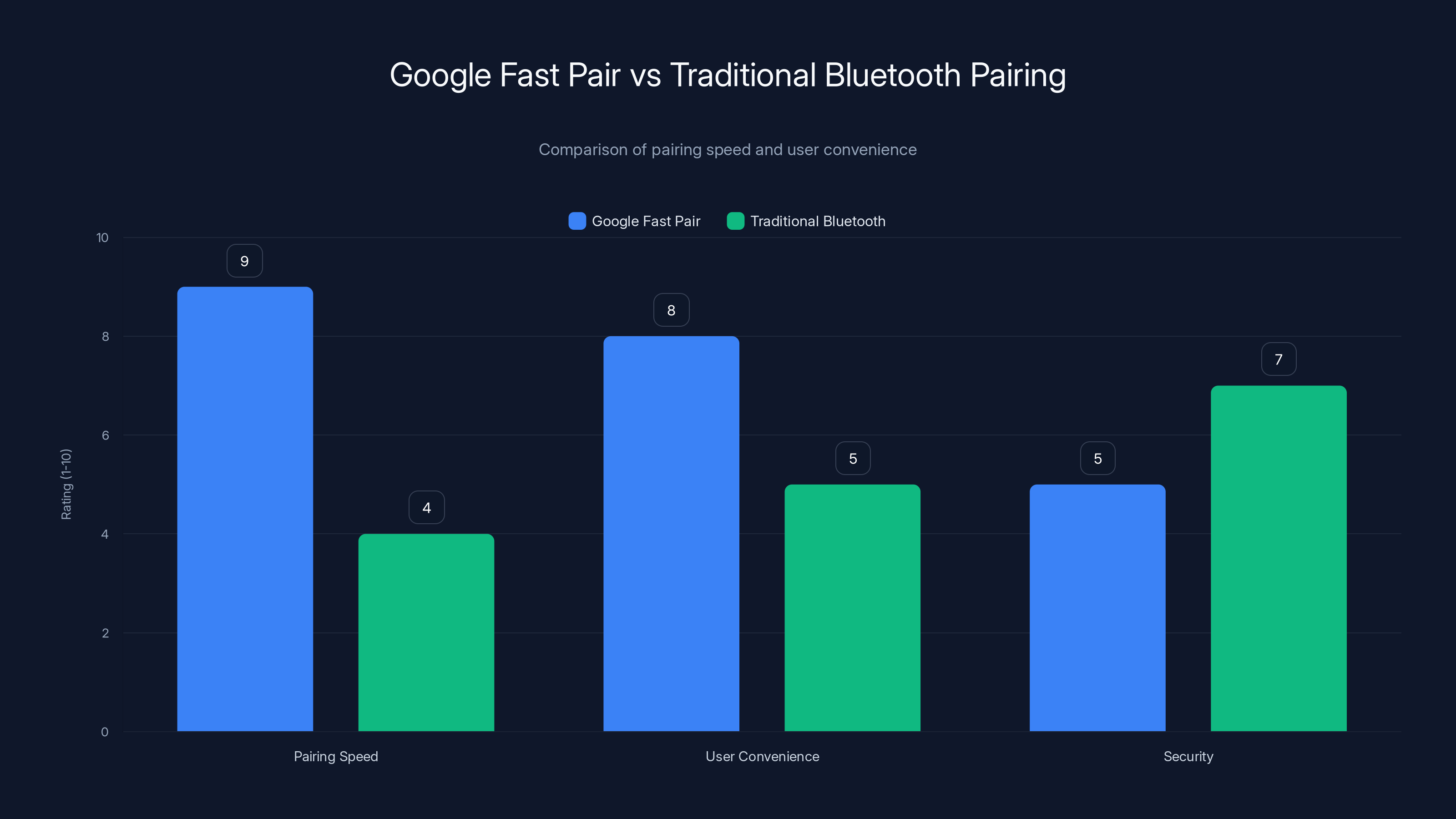

Google Fast Pair significantly improves pairing speed and user convenience over traditional Bluetooth pairing, but it has a lower security rating due to unencrypted broadcasts. Estimated data.

The Scope of the Vulnerability: Which Devices Are Affected?

The Fast Pair vulnerability affects an enormous installed base of devices. To understand the scope, let's break down which devices and manufacturers are impacted.

First, the Android devices on which Fast Pair runs. Google's own Pixel phones from the 6 series onwards have full Fast Pair support. Samsung devices from the Galaxy S10 and newer support Fast Pair. One Plus, Motorola, Xiaomi, Oppo, and other major Android manufacturers have integrated Fast Pair into their devices. With over 1 billion Android devices in active use, and assuming even 20-30% of them support Fast Pair, we're talking about hundreds of millions of vulnerable devices.

Second, the compatible accessories. This is where the scope becomes truly massive. Fast Pair compatible headphones come from Sony, JBL, Beats, Bose, Sennheiser, Google, Anker, Skullcandy, and dozens of other manufacturers. Smartwatches from multiple manufacturers support Fast Pair. Fitness trackers, earbuds, speakers, and other wireless accessories all participate in the ecosystem. The total number of Fast Pair compatible devices sold globally is likely in the billions.

Not all generations of these devices are equally vulnerable. Devices manufactured before Fast Pair was introduced obviously aren't affected. But the technology has been around since 2019, so we're talking about six years of compatible devices. Most people replace their headphones or smartwatches less frequently than that, so the number of vulnerable devices in active use is substantial.

Another aspect of the scope is geographic. This vulnerability isn't limited to a specific region or country. Google Fast Pair is implemented globally, across all markets where Android devices and compatible accessories are sold. A person tracking headphones doesn't require the person's phone to be sold in the same country as the headphones. The vulnerability affects users everywhere.

The vulnerability also affects all use cases and device configurations. Whether you're using Fast Pair with a single pair of headphones or carrying multiple Fast Pair devices simultaneously, you're vulnerable. Whether your Bluetooth is used actively or just enabled in the background, the vulnerability applies. This broad applicability means that the actual number of vulnerable situations is even larger than the number of vulnerable devices.

One important nuance is that not all Fast Pair implementations are equally vulnerable to tracking. Devices that implement randomized MAC addresses or certificate-based authentication are more resistant to some tracking techniques. However, the core vulnerability of unencrypted location broadcasts remains, and researchers have found ways to track devices even with these mitigations in place.

Detecting Whether You're Being Tracked

One of the most frustrating aspects of this vulnerability is that detecting active tracking is extremely difficult. Unlike malware or spyware that leaves traces in your system logs or network traffic, this attack is completely passive and silent. However, there are some indirect indicators that might suggest someone is tracking you.

The most obvious indicator would be physical surveillance combined with detailed knowledge of your location and movements. If someone knows exactly where you were at specific times, even though you didn't tell them, that's a red flag. If an ex-partner or someone with a history of abusing you suddenly seems to know your location patterns, that's concerning. If you discover suspicious devices in locations you frequently visit (in your apartment lobby, your workplace parking lot, etc.), those could potentially be tracking infrastructure.

Beyond these indirect indicators, detecting this specific Fast Pair tracking attack is challenging. There's no notification in your Android settings, no log entry, no indication that anything is happening. Some security apps might theoretically be able to detect unauthorized Bluetooth activity, but this would require specialized capabilities and wouldn't be practical for most users.

One technical approach to detection would be to use a Bluetooth scanner app to check what devices are advertising in your vicinity and compare that against what you'd expect. If you see unknown advertising identifiers from manufacturers whose devices you don't own, that might indicate someone nearby is tracking you. However, this approach is unreliable and would require technical knowledge to implement properly.

A more practical approach is prevention rather than detection. Assuming you might be at risk of being tracked, you should take protective measures even if you don't have evidence of active tracking. These preventive measures are discussed in detail in the protection section below.

For law enforcement and security professionals who need to detect organized tracking infrastructure, there are more sophisticated approaches. These might involve RF (radio frequency) analysis to detect unauthorized receivers, or honeypot devices set up to detect tracking infrastructure. But these are specialized techniques beyond what ordinary people can reasonably implement.

The challenge of detection is actually one of the reasons this vulnerability is so dangerous. The attack is difficult to prove, difficult to stop, and difficult to detect. Someone could be tracking you and you might never know. This is particularly concerning for vulnerable populations like domestic abuse survivors, who are at heightened risk for stalking.

Setting up a BLE monitoring system can be relatively low-cost, with the main expense being multiple receivers. Estimated data.

Protective Measures: How to Reduce Your Risk

The good news is that there are concrete steps you can take to reduce or eliminate your risk of being tracked via this vulnerability. None of these solutions are perfect, but in combination, they provide meaningful protection.

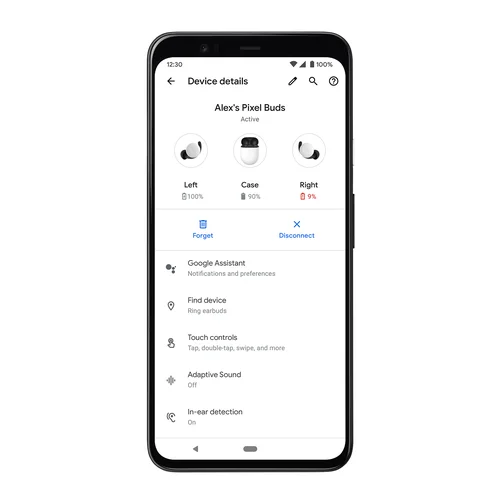

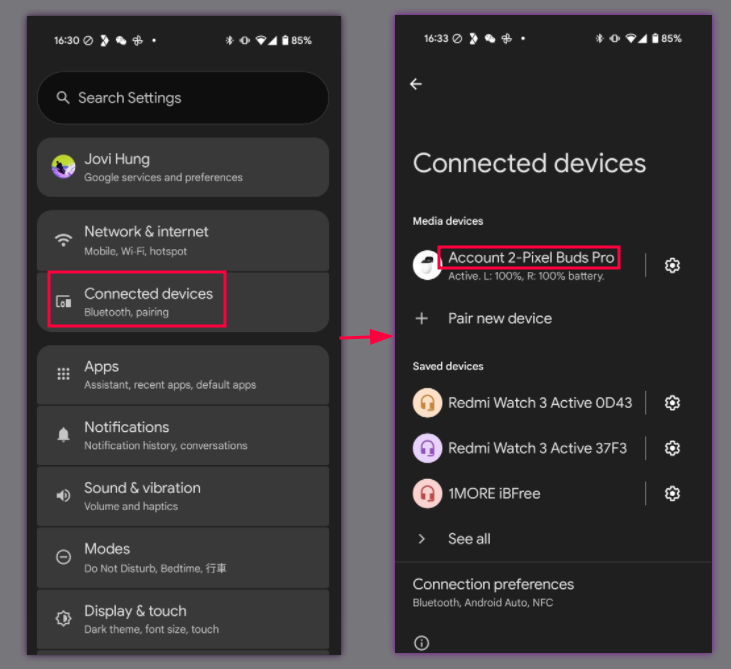

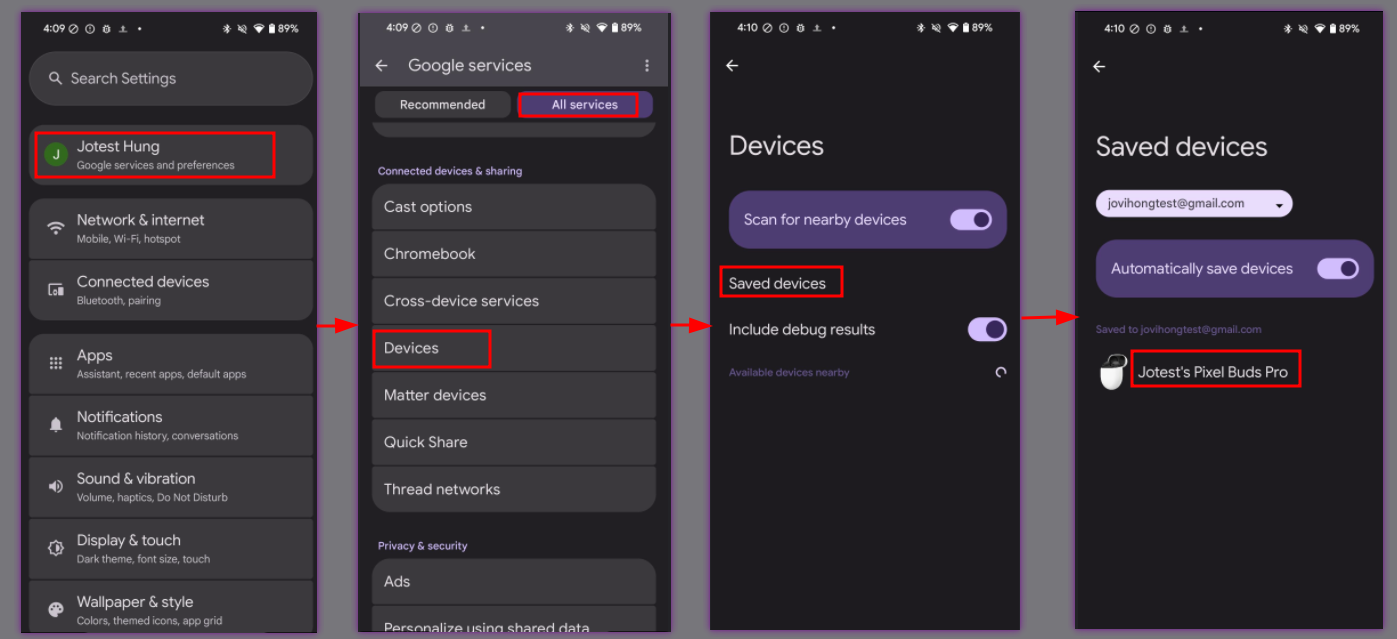

Disable Fast Pair: The most direct solution is to disable Fast Pair entirely. In your Android settings, go to Settings > Connected devices > Connection preferences > Bluetooth, and toggle off "Show pairing suggestions" or "Fast Pair" depending on your device. This prevents your device from broadcasting Fast Pair advertisements, eliminating the specific tracking vector. The downside is that you lose the convenient automatic pairing for new devices. You'll need to manually pair devices through the traditional Bluetooth settings menu, which is more time-consuming.

Use MAC Address Randomization: Modern Android versions support MAC address randomization, which changes your device's hardware address periodically or for each connection. This makes it harder to track the same device over time. However, this is only a partial solution because Fast Pair sometimes uses persistent identifiers that aren't affected by MAC address randomization. Also, MAC address randomization needs to be enabled both on your phone and in your Bluetooth settings, and some devices or apps may not work properly with it enabled.

Disable Bluetooth When Not in Use: Simple but effective. When you're not actively using Bluetooth devices, turn Bluetooth off completely. This prevents any broadcasts, including Fast Pair advertisements. The downside is that it requires discipline and awareness. If you habitually leave Bluetooth enabled, you're constantly broadcasting your location to potential attackers.

Use Privacy-Focused Accessories: If you're especially concerned about tracking, prefer to use Bluetooth accessories from manufacturers with strong privacy commitments. However, this doesn't fully solve the problem because the vulnerability is in the protocol itself, not in individual manufacturers' implementations. Every device following the Fast Pair specification is vulnerable to the same basic tracking attack.

Limit Your Device Combinations: The more Bluetooth devices you carry, the more location signals you're broadcasting. If you typically carry headphones, a smartwatch, and a fitness tracker, you're broadcasting three separate location signals. Consider whether you really need all of them, or whether carrying fewer devices reduces your attack surface. This might seem like a minor point, but in the context of privacy, every data point counts.

Advocate for Updates: Contact manufacturers of your Bluetooth devices and encourage them to implement privacy-respecting updates. Ask them whether they plan to support randomized device identifiers or other privacy enhancements. While individual advocacy won't change company policies overnight, it does send a message that customers care about privacy and that future purchasing decisions might depend on how seriously companies take these issues.

Stay Informed About Updates: Google has been working on improvements to the Fast Pair protocol. Keep your Android OS and Bluetooth firmware up to date to ensure you have the latest privacy improvements. However, be aware that these updates may not fully eliminate the vulnerability, so they shouldn't be your only protective measure.

Use a Bluetooth Jammer in Private Spaces: If you have the technical ability and if it's legal in your jurisdiction, you could use a Bluetooth jammer in private spaces like your home or office to prevent any unauthorized Bluetooth devices from operating in those locations. However, this is extreme and probably overkill for most people. Jammers are illegal in many countries and can interfere with legitimate devices.

The most practical approach for most people is a combination of these measures: disable Fast Pair if you're comfortable with manual Bluetooth pairing, turn off Bluetooth when you're not actively using wireless devices, and stay aware of what devices you're carrying that could be tracked. If you're in a high-risk situation (stalking concerns, domestic abuse, investigative journalism), take additional measures like disabling Bluetooth entirely when not needed.

What Google and Device Manufacturers Should Do

While individual users can take protective measures, the responsibility for fixing this vulnerability ultimately rests with Google and the manufacturers of compatible devices. Several improvements are possible and necessary.

Encrypt Fast Pair Advertisements: The most direct fix would be to add encryption to Fast Pair advertisements. This would prevent passive eavesdropping and make tracking substantially more difficult. However, encryption adds complexity and could impact device performance and battery life. It would also require changes to all compatible devices, not just Android phones, which is logistically challenging.

Implement Randomized Device Identifiers: Fast Pair could use randomly rotating device identifiers instead of persistent ones. Each time your headphones broadcast their presence, they could use a different identifier. Your phone would still recognize them because of information stored locally, but an attacker listening would see different identifiers each time and couldn't track the same device over extended periods. This is technically feasible but would require careful implementation to maintain compatibility.

Limit Advertisement Frequency and Range: Devices could be configured to advertise less frequently and at lower power levels. This would reduce the window during which attackers could detect and track devices. It would slightly impact the convenience of Fast Pair (pairing might take a few seconds longer), but the privacy benefit would be substantial.

Add User-Controlled Privacy Levels: Fast Pair could implement different privacy modes that users can select. A "privacy mode" could disable broadcasting entirely. A "balanced mode" could use randomized identifiers. A "convenience mode" could maintain the current behavior for users who prioritize speed over privacy. This would give users choice while maintaining backward compatibility.

Provide Better Visibility and Controls: Android could provide more transparent information about Fast Pair and better user controls. Currently, many users don't even know Fast Pair exists or understand what it's doing. Clearer labeling and easier controls would empower users to make informed decisions about their privacy.

Require Privacy Certifications: Google could require that all devices certified for Fast Pair support certain privacy-preserving features. This would set a minimum standard across the ecosystem and prevent the lowest common denominator approach where devices implement only the minimum required functionality.

The reality is that implementing comprehensive fixes is challenging and expensive. It would require coordination among dozens of manufacturers, firmware updates to billions of devices, and careful testing to ensure nothing breaks. It's easier for companies to continue with the status quo. However, as privacy concerns become more prominent and regulations like GDPR become stricter, the pressure on Google and manufacturers to address this vulnerability will only increase.

Estimated data shows stalking and harassment as the most prevalent attack scenario at 40%, followed by corporate espionage at 35%, and retail profiling at 25%.

Privacy Regulations and Legal Implications

The Fast Pair vulnerability exists at an interesting intersection of technology and privacy law. Different jurisdictions have different rules about what constitutes illegal surveillance and when tracking is permitted.

In the European Union, GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) treats location tracking as personal data processing. Any organization tracking someone's location needs their explicit consent and must have a legal basis for the processing. Passive tracking via Bluetooth signals probably violates GDPR unless the person has explicitly consented to this tracking. However, enforcement is challenging because the tracking is difficult to detect and prove.

In the United States, federal laws are fragmented. There's no comprehensive privacy law covering all states. Some states have electronic surveillance laws that could potentially cover Bluetooth tracking in certain contexts. Federal wiretapping laws might apply if someone is deliberately tracking another person's movements. However, the lack of a clear legal framework makes enforcement unpredictable.

The challenge for regulators is that this type of tracking sits in a gray area. It's not traditional hacking (you're not accessing the target's device). It's not traditional stalking (you're just listening to broadcasts the device is already making). It's not wiretapping in the traditional sense (you're not intercepting communications). This gray area makes it difficult for existing laws to clearly address the behavior.

From a manufacturers' perspective, the liability risk of this vulnerability is significant but currently undefined. If it becomes clear that Fast Pair enables widespread stalking or harassment, manufacturers could face lawsuits from victims. They could also face regulatory action from privacy authorities. This liability risk, more than anything else, might be what eventually drives companies to implement proper fixes.

The Future of Bluetooth Tracking and Privacy

The Fast Pair vulnerability is just one example of a broader category of risks associated with always-on wireless devices. As more and more devices become connected and constantly broadcast their presence, the opportunities for location tracking and surveillance increase. Understanding the trends in this space helps us think about future risks and solutions.

One emerging technology is Bluetooth mesh, which extends the range of Bluetooth networks by allowing devices to relay signals through intermediate devices. This could potentially extend the range at which someone could track your devices. Manufacturers are also working on improving Bluetooth's security and privacy features, but these improvements are slow to roll out across the ecosystem.

Another trend is the proliferation of Internet of Things (Io T) devices. Many smart home devices, wearables, and other Io T gadgets use Bluetooth for local communication and discovery. Each of these devices represents another potential tracking signal. As people accumulate more smart devices, they're potentially creating more location signals that could be used to track them.

On the positive side, there's increasing recognition in the tech industry that privacy and security need to be designed in from the beginning, not added as an afterthought. Companies like Apple have made privacy a marketing differentiator. This creates pressure on competitors like Google to match or exceed Apple's privacy standards. Over the next few years, we'll likely see more privacy-preserving implementations of convenience features like Fast Pair.

The long-term solution probably involves a combination of technical fixes, regulatory pressure, and user choice. As consumers become more privacy-conscious, they'll demand better privacy protections. As regulators like the EU enforce privacy laws more strictly, companies will have financial incentives to fix these issues. And as security researchers continue to identify vulnerabilities, the pressure for fixes will build.

FAQ

What exactly is the Google Fast Pair vulnerability?

The Fast Pair vulnerability allows attackers to track wireless headphones and other Bluetooth devices by intercepting unencrypted location broadcasts. When a compatible device like headphones is turned on near an Android phone, it broadcasts its location via Bluetooth Low Energy signals. These signals contain identifying information that an attacker can detect from a distance, allowing them to track the device's location over time without requiring any access to the phone itself.

How far away can an attacker be and still track me?

Bluetooth Low Energy has a theoretical range of about 100 meters in open space, but the practical tracking range depends on the equipment and environment. With standard Bluetooth receivers, the range is typically 20-50 meters depending on walls and interference. However, attackers using specialized software-defined radio equipment and external antennas might extend this range to 100+ meters. The range is sufficient in most residential and commercial building contexts to conduct tracking.

Do I need to be doing anything suspicious for an attacker to track me?

No, the attack is completely passive and doesn't require any action on your part. You don't need to have your Bluetooth discoverable mode enabled. You don't need to be trying to pair with anything. The attack simply listens to broadcasts your device is already making. Simply having Bluetooth enabled and carrying a Fast Pair compatible device is sufficient for tracking to occur.

Will updating my phone fix the vulnerability?

Updating your Android operating system and Bluetooth firmware can provide partial protection through improvements like randomized MAC addresses and certificate-based authentication. However, these updates don't fully eliminate the vulnerability. The core problem of unencrypted location broadcasts remains. Updating is still a good security practice, but it shouldn't be your only protective measure.

Can I use my headphones safely if I disable Fast Pair?

Yes, disabling Fast Pair doesn't prevent you from using your headphones. It just means you'll need to pair them manually through the Bluetooth settings menu instead of automatically through the Fast Pair prompt. Manual pairing is slightly more inconvenient but takes only a minute or two. Your headphones will continue to work normally after they're paired.

What should I do if I suspect I'm being tracked?

If you suspect you're being tracked and you're in danger, contact local law enforcement immediately. If the concern is less urgent, start by disabling Fast Pair and turning off Bluetooth when not in use. Consider whether you know of anyone who might have reason to track you. If you're in an abusive situation or being stalked, reach out to domestic violence resources or victim advocacy organizations that can provide specific guidance for your situation.

Which manufacturers are affected by this vulnerability?

Any manufacturer whose devices support Google Fast Pair is affected, including Sony, JBL, Beats, Bose, Sennheiser, Google, Anker, Skullcandy, and many others. Essentially, if your headphones or smartwatch advertise compatibility with Google Fast Pair, they're vulnerable to this tracking attack. Check your device's specifications or the manufacturer's website to determine if your specific device supports Fast Pair.

Can Apple users also be tracked through this method?

Apple doesn't use Google's Fast Pair protocol. Instead, Apple uses a proprietary system that integrates with i Cloud. Apple's implementation uses encrypted identifiers and device certificates, making it significantly more difficult to track compared to Fast Pair. However, Apple devices are not immune to tracking; they could potentially be tracked through other Bluetooth mechanisms or through different vulnerabilities.

Immediate Action Items You Should Take Today

Now that you understand the vulnerability and the risks, here are the specific actions you should take right now to protect yourself.

First, check whether you're using Fast Pair. On your Android phone, go to Settings > Connected devices > Connection preferences > Bluetooth. Look for an option called "Show pairing suggestions" or "Fast Pair." If it's enabled, you're currently vulnerable. Decide whether the convenience of Fast Pair is worth the privacy risk for you personally. If you choose to disable it, toggle off the option.

Second, take inventory of the Bluetooth devices you regularly carry. Make a list of your headphones, smartwatch, fitness tracker, and any other wireless accessories. For each device, check whether it supports Fast Pair by looking at the manufacturer's specifications or manual. Knowing what's broadcasting helps you understand your exposure.

Third, establish a habit of turning off Bluetooth when you're not actively using it. This is the single most effective protective measure available to most people. You can quickly toggle Bluetooth on when you need it, but leaving it constantly enabled is both a battery drain and a privacy vulnerability.

Fourth, if you're in a situation where you might be at elevated risk of being tracked (past stalking, current or recent relationship conflict, work that involves sensitive information), consider additional protective measures. These might include disabling Bluetooth entirely except when needed, using wired headphones instead of wireless, or reducing the number of Bluetooth devices you carry.

Fifth, stay informed about updates. Subscribe to security news from reputable sources so you'll know if Google releases improved privacy features for Fast Pair. Keep your Android OS and device firmware updated to ensure you have the latest security patches.

Sixth, if you discover someone is tracking you, take it seriously. Contact law enforcement if you believe you're in danger. Reach out to domestic violence resources or other victim advocacy organizations if you're being stalked or harassed. Document any suspicious activity and preserve evidence if possible.

Conclusion

The Google Fast Pair vulnerability represents a significant privacy risk that affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide. The core issue is simple: convenience features in technology often come with hidden security costs. Fast Pair solved a real user experience problem, but it did so in a way that enables persistent location tracking by anyone within Bluetooth range.

What makes this vulnerability particularly serious is how difficult it is to detect and how effective it is at enabling real-world harms. Unlike many cybersecurity vulnerabilities that require technical expertise or access to exploit, this one can be abused by anyone with basic technical knowledge and inexpensive equipment. The victims of this attack would have no way to know they're being tracked and no practical way to prove it after the fact.

The good news is that you have practical options available right now. Disabling Fast Pair, turning off Bluetooth when not in use, and reducing the number of constantly-connected devices you carry all meaningfully reduce your risk. These measures require some behavioral change and convenience trade-offs, but they're entirely within your control.

Longer-term solutions require action from Google, device manufacturers, and regulators. Technical improvements like encrypted advertisements and randomized identifiers can reduce the vulnerability. Stronger privacy regulations can create legal incentives for companies to prioritize privacy. User pressure and preference for privacy-conscious products can drive market competition on privacy grounds.

The Fast Pair vulnerability shouldn't make you paranoid or cause you to reject technology entirely. Most people aren't at immediate risk of being targeted by sophisticated tracking operations. However, if you value your privacy and recognize the potential harms of location tracking, taking basic protective measures is sensible and straightforward.

Ultimately, this vulnerability illustrates a broader principle: as devices become more capable and more connected, we need to be more thoughtful about the privacy implications of convenience. The most user-friendly feature isn't necessarily the most privacy-respecting one. The best technology choices balance convenience and privacy according to your own threat model and values. Understanding vulnerabilities like this one empowers you to make those choices consciously.

Key Takeaways

- Google Fast Pair broadcasts unencrypted location data through Bluetooth signals that attackers can intercept with inexpensive software-defined radio receivers

- The vulnerability affects hundreds of millions of Android devices and compatible accessories from Sony, JBL, Beats, and other manufacturers worldwide

- Attackers can track your movement patterns, build location profiles, and enable stalking without any indication on your phone or device

- Disabling Fast Pair, turning off Bluetooth when not in use, and reducing connected devices are immediate protective measures you can implement today

- Comprehensive fixes require technical improvements from manufacturers, regulatory pressure, and user demand for privacy-respecting implementations

![Google Fast Pair Exploit: How Hackers Track Your Headphones [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-fast-pair-exploit-how-hackers-track-your-headphones-2/image-1-1768568974477.png)