Google's $135 Million Data Collection Settlement: What Android Users Need to Know

January 2025 marked another significant moment in Big Tech's ongoing legal reckoning with privacy violations. Google announced it would pay $135 million to settle a class action lawsuit accusing the company of harvesting cellular data from millions of Android devices without explicit user consent. The settlement represents one of the largest payouts in data collection litigation history, yet it barely made headlines beyond tech circles. For Android users who've been unknowingly tracked for years, this settlement answers a question they never knew to ask: where did Google get all this location and cellular data?

This isn't Google's first privacy rodeo. The company faces constant scrutiny over how it collects, stores, and monetizes user information. What makes this settlement particularly striking is the legal theory behind it. Plaintiffs claimed Google committed "conversion," a property law concept that dates back centuries but rarely applies to digital data. By arguing that location data and cellular information are property that Google wrongfully took, attorneys opened a novel path to holding tech giants accountable. The settlement came just days after Google agreed to pay $68 million in a separate case alleging Google Assistant was recording users after mishearing wake words. These back-to-back settlements signal something important: the cost of privacy violations is finally becoming real enough to change corporate behavior.

But here's what the headlines miss. Understanding this settlement means understanding how Android data collection actually works, why it happened for so long, and what it means for your privacy going forward. The story involves cellular carriers, background location tracking, encrypted data flows, and the fine print of terms of service that basically nobody reads. It also raises uncomfortable questions about whether $135 million is actually enough to make Google think twice about repeating these practices.

TL; DR

- Settlement amount: Google will pay $135 million to settle claims it illegally collected cellular data from Android devices since November 2017

- User compensation: Eligible Android users could receive up to $100 each from the settlement fund

- The allegation: Google harvested cellular data without explicit consent, even when apps were closed or location services disabled

- Legal theory: Plaintiffs argued Google committed "conversion" by taking user data as property, a novel approach in tech litigation

- Timing: Settlement came amid a broader period of Google privacy lawsuits, with a $68 million settlement announced the same week for Google Assistant recording claims

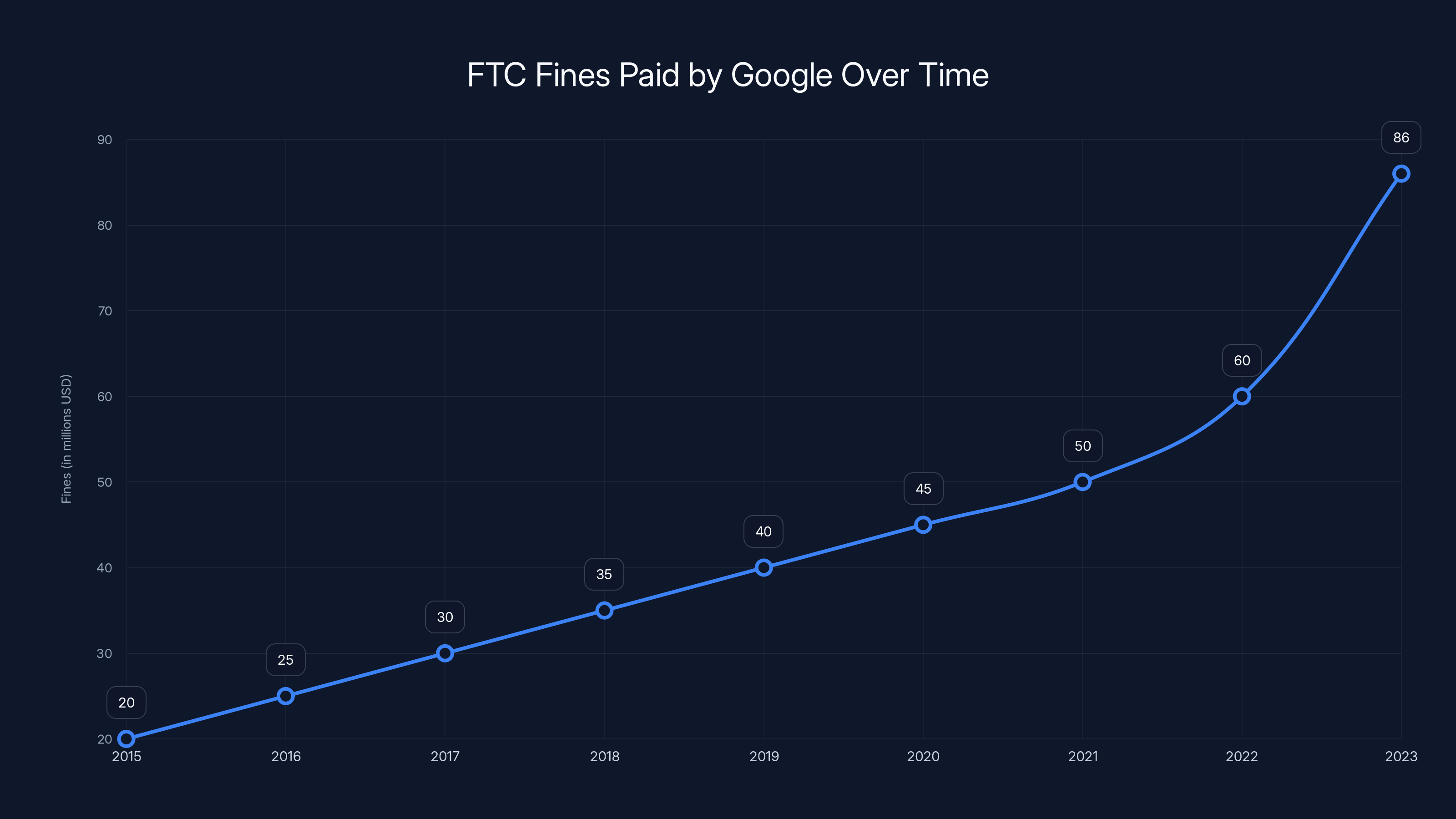

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in FTC fines paid by Google, peaking in 2023 with $86 million. Estimated data.

The Core Issue: How Google Collected Data It Shouldn't Have

Understanding what Google actually did requires peeling back layers of technical complexity and corporate obfuscation. The lawsuit centered on a specific claim: between November 12, 2017, and sometime recently (the exact end date remained flexible in settlement negotiations), Google collected cellular and location data from Android devices in ways users didn't authorize.

The mechanism worked like this. Android devices maintain constant connections to cellular networks operated by carriers like Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile. This connection carries metadata: which cell towers your phone connects to, signal strength, network type (4G, 5G, etc.), and other technical details. Normally, apps need explicit permission to access location data, and users can disable location services entirely. What Google allegedly did was bypass these standard privacy controls and pull cellular metadata directly, then use that information to pinpoint user locations with surprising accuracy.

The distinction matters. Your phone's cellular connection happens automatically, continuously, in the background. It's like listening to the vibration frequency of a room to figure out where someone is standing. Google didn't need to activate GPS or trigger location permissions. The data was already flowing from the phone to the network, and Google found a way to harvest it.

Several factors made this data collection particularly egregious. First, users couldn't easily disable it. The settlement documents suggest that even with location services turned off, Google's data collection continued. Second, the data served no apparent user-facing benefit. Google wasn't using it to improve navigation, respond to emergency calls, or enhance your Google Maps experience. Instead, according to the lawsuit, the company used it for marketing and product development. That means Google was selling or leveraging location insights without the people generating that data even knowing it was happening.

Third, the practice persisted for years. Seven years of continuous, unauthorized data harvesting from potentially millions of devices adds up quickly. If you were an Android user during that period, Google may have built a comprehensive behavioral profile of your movements, your habits, your routines, and your patterns without ever asking permission.

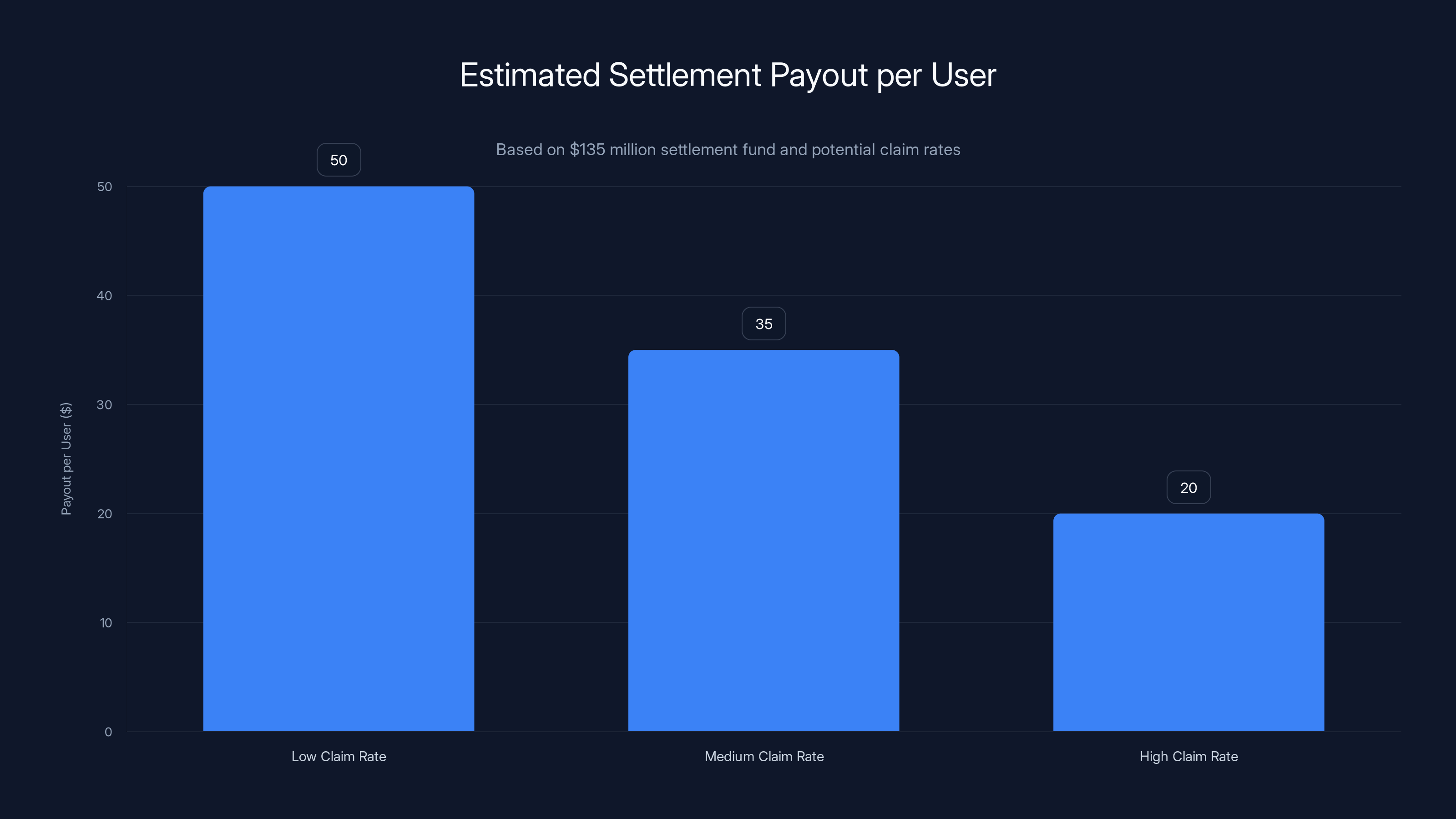

Estimated payouts range from

The Legal Framework: What Is "Conversion" and Why It Matters

Plaintiff attorneys didn't sue Google for violating privacy laws, though those laws certainly existed. Instead, they used a much older legal concept: conversion. This strategy deserves attention because it could reshape how courts handle tech privacy cases going forward.

Conversion is a property tort. Fundamentally, it means one person took another person's property and exerted control over it without permission. If someone steals your car, that's conversion. If someone takes your watch and sells it, that's conversion. The legal definition focuses on the intent to deprive someone of their property or to exercise property rights over it. Courts have historically treated conversion as applying to tangible goods. You can't convert someone's reputation or hurt feelings. You need actual property.

But what is data? That's where this case got interesting. Attorneys argued that location and cellular data represent property that belongs to the users who generate it. By collecting this data and using it for commercial purposes, Google exerted property rights over something it didn't own. The company didn't ask for permission, didn't offer compensation, and didn't acknowledge the user's ownership stake. From a pure property law perspective, that looks a lot like conversion.

This approach matters for several reasons. Privacy law varies significantly by jurisdiction. California has strong privacy protections through laws like CCPA, but other states have weaker frameworks. Conversion, however, is a common law principle recognized across all fifty states. By framing data collection as property conversion rather than privacy violation, attorneys created a legal theory that could travel across state lines and apply to any company in any jurisdiction.

Another advantage: conversion doesn't require proving that Google made false statements or violated a specific statute. The plaintiff just had to show that Google took property belonging to them and used it without permission. The company's intent becomes harder to defend. Google's argument that they didn't violate any explicit privacy law falls flat when confronted with basic property rights.

The genius of this legal strategy is that it bypasses the murky world of terms of service interpretation. Companies hide privacy violations in dense legal documents expecting most users never to read them. But conversion doesn't care what the terms of service say. If you take someone's property, it doesn't matter that they clicked "I agree" to a fifty-page user agreement somewhere. Ownership still matters more than contractual fine print.

Why Seven Years of Data Collection Went Unnoticed

One question dominates any discussion of this settlement: how did Google get away with this for seven years? The answer involves technical sophistication, regulatory blindness, and the sheer scale of modern tech platforms.

Android's architecture made this collection possible. Unlike iOS, which Apple tightly controls, Android operates as an open ecosystem where Google doesn't directly manage every device. Instead, Google provides the operating system to manufacturers like Samsung, Motorola, and others who customize it for their own devices. This fragmentation created an opportunity. Google could collect data at the operating system level, below the layer of scrutiny that typically applies to individual apps.

Second, cellular data collection happens invisibly. Location permissions trigger notifications and warning dialogs. If Google activated your GPS without permission, you might notice the battery drain or see location icons in the status bar. Cellular metadata collection? It happens in the background, completely silently. Your phone needs to maintain that connection anyway for calls, texts, and data. Google simply tapped into information that was already flowing.

Regulatory agencies didn't catch this quickly either. The FTC, which oversees tech company privacy practices, suffers from chronic underfunding and technical expertise gaps. Privacy violations often go undetected for years because nobody has the resources to audit what these companies actually do internally. By the time regulators or researchers discover a problem, millions of devices have already been harvesting data for months or years. The company pays a fine months or years later, adjusts its practices, and moves on. The economic math still favors violations until the settlements get large enough to hurt.

Google also had internal knowledge of what it was doing. The settlement documents and investigative reporting suggest that Google engineers knew about this data collection. This wasn't an accident or a bug. It was a deliberate feature, built into Android, designed to improve Google's location database and advertising capabilities. That matters legally because it removes the "we didn't know" defense. Google knew, didn't disclose it, and continued the practice across millions of devices.

User behavior also played a role in the long delay. Most people don't carefully audit what data their devices collect. Privacy settings remain confusing and scattered across dozens of menus. The average person switches phones every few years, and might not realize their old device was participating in data collection they never explicitly authorized. The combination of technical obscurity, user inattention, and regulatory weakness created a perfect environment for sustained abuse.

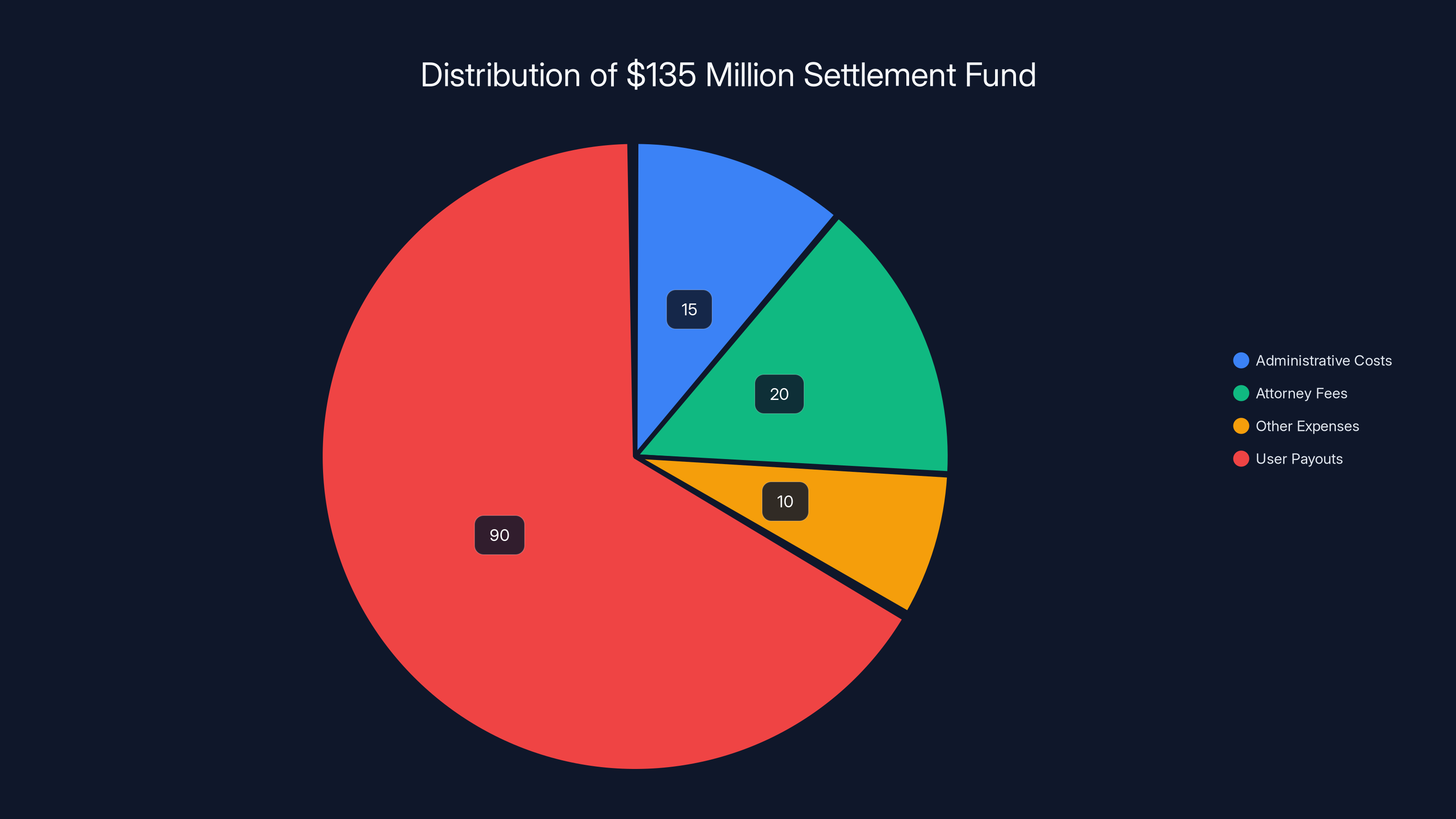

Estimated data: Administrative costs, attorney fees, and other expenses are deducted from the

Breaking Down the $135 Million Settlement

The settlement itself requires careful parsing. The headline number sounds significant, but the actual payout to individual users depends on several factors.

Google agreed to pay a total of

The settlement also includes injunctive relief, meaning Google must change its practices going forward. The company agreed to implement new privacy controls, provide clearer disclosures about data collection, and allow users to opt out of cellular data harvesting. On paper, this seems like actual improvement. In practice, it depends heavily on enforcement. If the court doesn't actively monitor Google's compliance, and if Google faces minimal penalties for violations, the incentive to cheat returns quickly.

Compare this to the

For context, consider what

How the Settlement Affects Different User Groups

The impact of this settlement varies significantly depending on your specific situation and how you used your Android device.

Heavy Android users from 2017-2025 likely saw the most extensive tracking. If you owned multiple Android devices during the settlement period, Google potentially built a detailed profile of your movements across years. Your home location, your workplace, the places you visit regularly, the stores you shop at, the restaurants you frequent—all of it ended up in Google's database. For someone constantly moving between devices, this creates a comprehensive behavioral map.

People who specifically disabled location services were supposedly protected by those settings, yet Google collected data anyway. This group has perhaps the strongest claim because they explicitly took action to prevent tracking. Google ignored those privacy decisions and harvested data regardless.

Users in states with strong privacy laws may have additional claims beyond this settlement. California, for instance, has passed strong privacy legislation. Android users in California might pursue additional state-level claims that provide stronger protections or larger payouts than a federal settlement.

Enterprise and corporate users present an interesting case. Many businesses issue Android devices to employees. If an employee's work device was subject to this data collection, does the corporation have standing to claim damages? The settlement doesn't clearly address this, which could create secondary litigation.

Children and minors deserve special consideration. If Google collected location data about minors without parental consent, additional liability might apply. Privacy laws often provide stronger protections for children. The settlement barely mentions minors, which represents a significant gap.

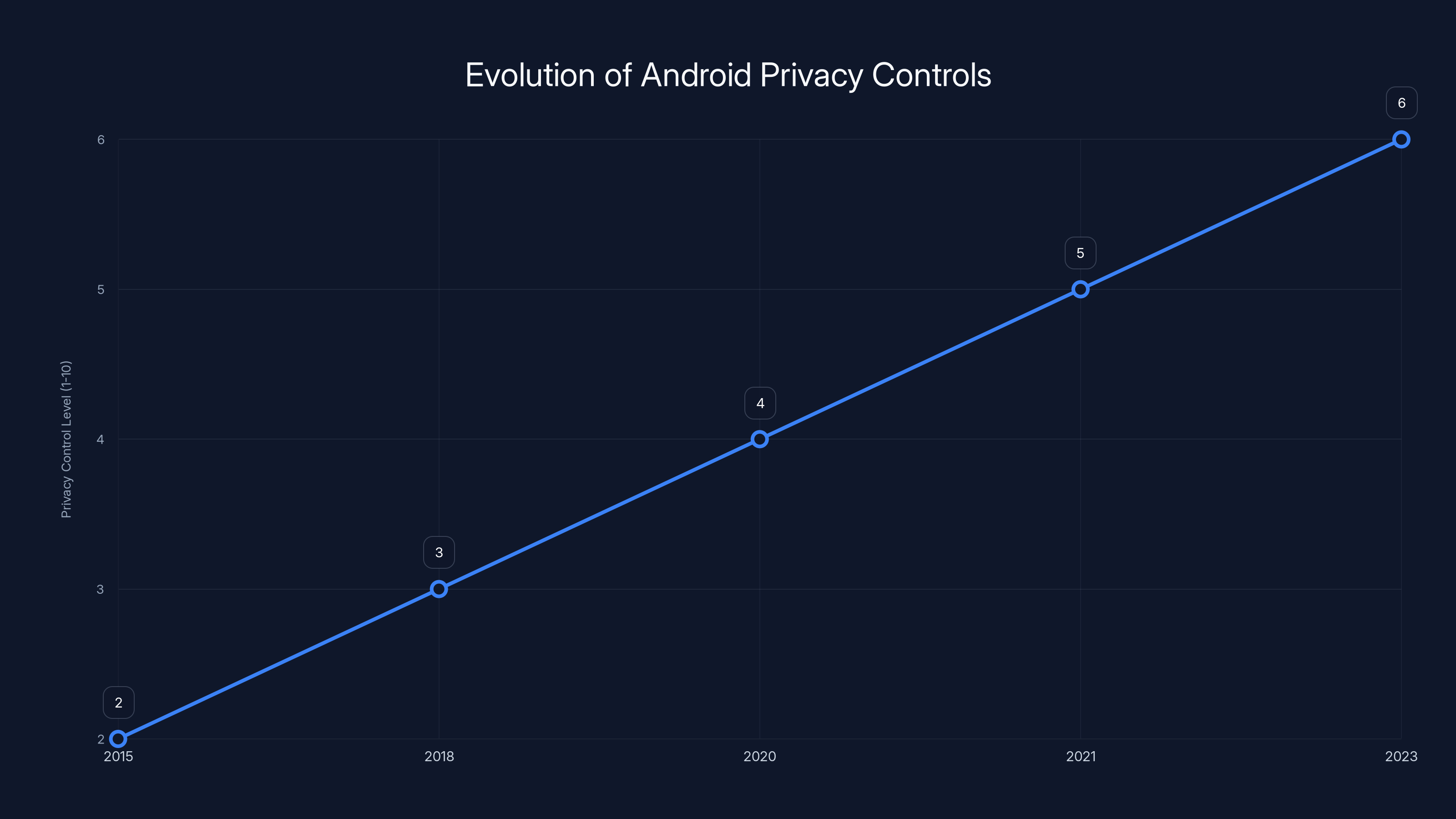

Estimated data shows a gradual improvement in Android's privacy controls, especially after public and regulatory pressures. Each new version brought more granular permissions.

The Broader Privacy Landscape: Why This Settlement Matters More Than You'd Think

This settlement doesn't exist in isolation. It represents part of a larger pattern of Big Tech companies facing consequences for privacy abuses. Understanding that pattern helps explain why this matters beyond the immediate $100 check some users might receive.

Over the past five years, major tech companies have paid settlements totaling in the billions of dollars for privacy violations. Facebook paid $5 billion to the FTC and agreed to restructure its privacy practices. Amazon faced investigations for AWS customer data leaks. Microsoft dealt with email server vulnerabilities that exposed customer information. Apple promised privacy but simultaneously cooperated with law enforcement in ways users didn't expect. These settlements create a ratcheting effect where expectations for privacy protection gradually increase.

The Google settlement introduces the conversion framework to mainstream tech litigation. If this theory holds up on appeal and becomes established precedent, it opens pathways for future suits against all tech companies that monetize user data. That's genuinely significant because it means the legal system is developing new tools to constrain corporate behavior that privacy statutes alone haven't effectively limited.

Second, the settlement might influence how Android device manufacturers approach privacy. Samsung, Google's largest Android partner, could face pressure to implement stricter controls preventing carrier-level data collection. This could actually improve privacy for millions of Android users going forward, independent of the settlement money.

Third, the settlement creates documentary evidence that Google deliberately collected data it knew it shouldn't. These documents become available for future lawsuits. Attorneys can cite this settlement as proof of intent and knowledge, making subsequent cases easier to win. The precedent matters more than this specific payout.

What Google Claims About Its Data Collection Practices

Google maintains that it did nothing wrong. The company denied liability in both the

The company currently states that it collects location data only with explicit user consent. Android settings allow users to enable or disable location services with clear toggles. Google's official documentation explains that location data is necessary for features like Google Maps navigation, local search results, and location-based reminders. On the surface, this sounds reasonable and transparent.

But here's the disconnect. The settlement specifically alleges that Google collected cellular data even when location services were disabled. That means Google used a separate data stream that didn't respect the standard Android privacy controls. The company was operating a hidden tracking system parallel to the official location system. Most users never realized this parallel system existed.

When asked about this, Google could reasonably claim that these practices happened years ago and have since been rectified. The company did make significant privacy improvements to Android over the years, partly in response to public pressure and regulatory attention. Android 12 and later versions introduced more granular permission controls. Android 14 began limiting background location access even more aggressively. On the surface, Google appears to be moving in the right direction.

The reality is more complicated. Each privacy improvement came only after public pressure, regulatory threat, or litigation. Google didn't voluntarily implement these controls out of principle. The company implemented them because the cost of regulation exceeded the benefit of continued tracking. This settlement changes the cost calculation again, potentially prompting more genuine privacy improvements. But trusting Google's voluntary commitments requires accepting a track record of systematic abuse followed by reluctant reform.

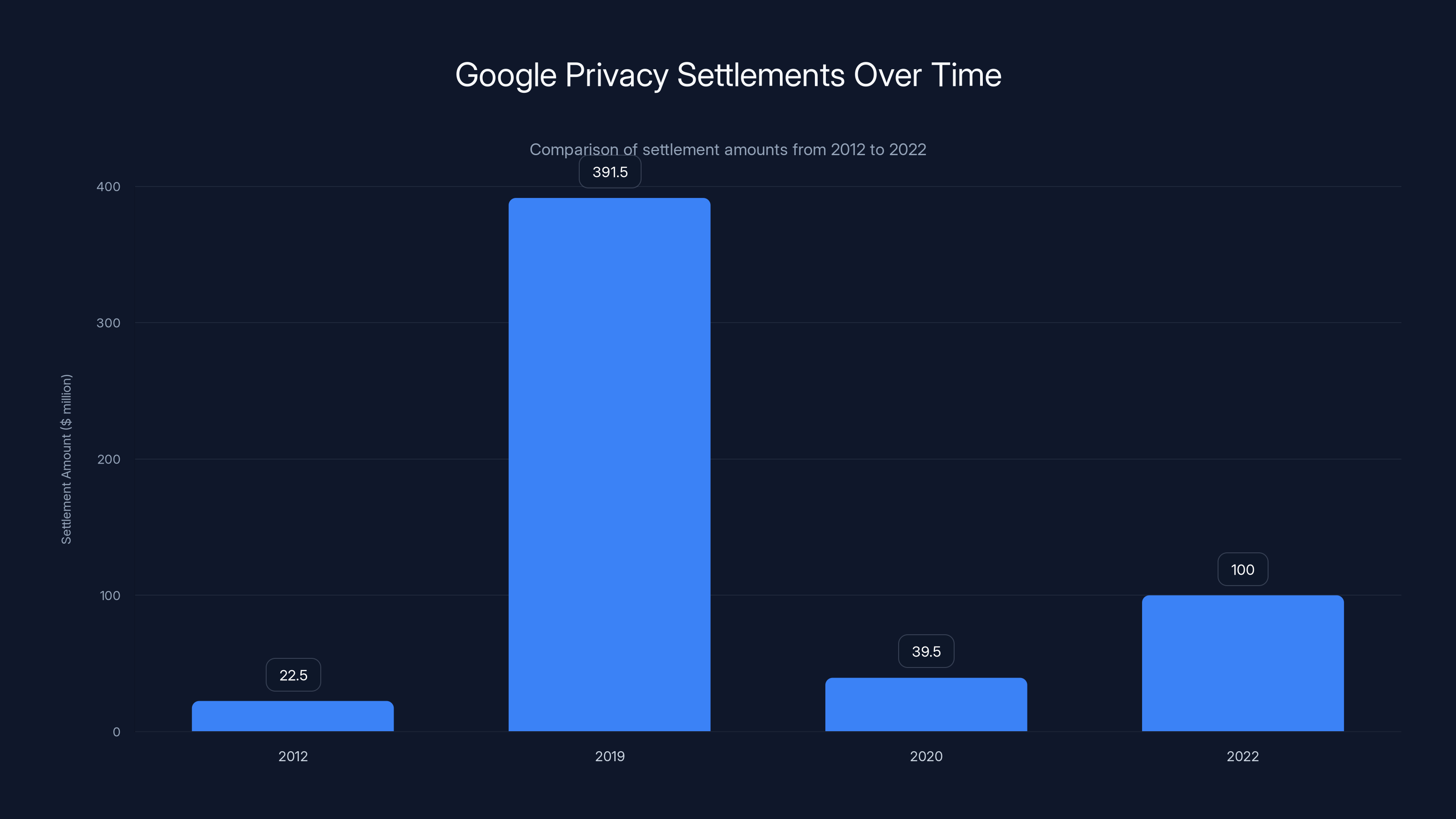

Google's settlement amounts have varied over the years, with a significant increase in 2019. Despite these settlements, privacy issues persist. Estimated data for 2022.

The Class Action Mechanism and Why It Matters

Understanding how this settlement actually gets distributed requires knowing how class action lawsuits work. The mechanism is theoretically elegant but practically problematic.

When a court certifies a class action, it says that millions of individuals with similar grievances can be represented by a handful of plaintiffs and a law firm. This solves a massive practical problem. No court could handle ten million individual lawsuits, so class actions aggregate them. In theory, this lets regular people hold big companies accountable without needing their own expensive lawyers.

In practice, class actions benefit lawyers enormously. In this Google settlement, the plaintiff attorneys receive a substantial fee from the settlement fund. Standard arrangements give attorneys 25-33% of settlement amounts. In a

This creates weird incentives. Attorneys want to settle cases quickly even when larger settlements might be possible. They want settlements structured to maximize legal fees. Individual class members have minimal voice in these negotiations. The court approves the settlement, but courts rarely reject attorney-proposed terms because the alternative is endless litigation that benefits nobody except the lawyers involved.

For the current Google settlement, several complications could suppress claim rates. First, eligible users need to affirmatively claim their compensation. The settlement requires identification of which Android devices they owned during the relevant period. People who've upgraded phones or forgotten the details of devices from 2017 might struggle to prove eligibility. Second, most people don't pay attention to settlement notices. Research shows that 80-90% of class action members never claim their entitled compensation.

Google might welcome low claim rates. If only half the potential class members file claims, the per-person payout doubles. But Google's lawyers probably anticipated this and potentially underfunded the settlement anticipating that many people wouldn't claim. This is one reason why actual per-person payouts often disappoint people who eventually remember to file claims.

The Role of Android Device Carriers in Data Collection

One aspect of this story that rarely gets discussed is the role played by cellular carriers. Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, and regional carriers like US Cellular operate the cellular networks that generate the metadata Google collected.

Did carriers consent to Google's data collection? Did they benefit from it? The settlement documents don't fully clarify carrier involvement. This raises uncomfortable questions about whether carriers should bear some responsibility for enabling Google's collection or should receive blame for not preventing it.

Historically, carriers have been surprisingly opaque about data practices. These companies collect tremendous amounts of information about customer behavior. They know where you are when you make calls, which websites you visit, what time you're active. For years, carriers have monetized this information by selling aggregated location data to third parties and advertisers. Did Google pay carriers for access to this data, or did the company secretly tap into data flows?

Some reports suggest that Google worked directly with carrier networks to collect metadata. If true, this means carriers actively participated in collecting and providing data to Google. In that scenario, carriers share liability. The settlement doesn't explicitly address carrier involvement, which seems like a significant oversight. Users might have claims against carriers as well, completely separate from the Google settlement.

This carrier dimension also affects remedies. Going forward, preventing similar violations requires carrier cooperation and oversight. If carriers continue to provide metadata access to companies like Google without explicit user consent, new data collection schemes will emerge. The settlement pressure needs to extend to carriers as well, not just Google.

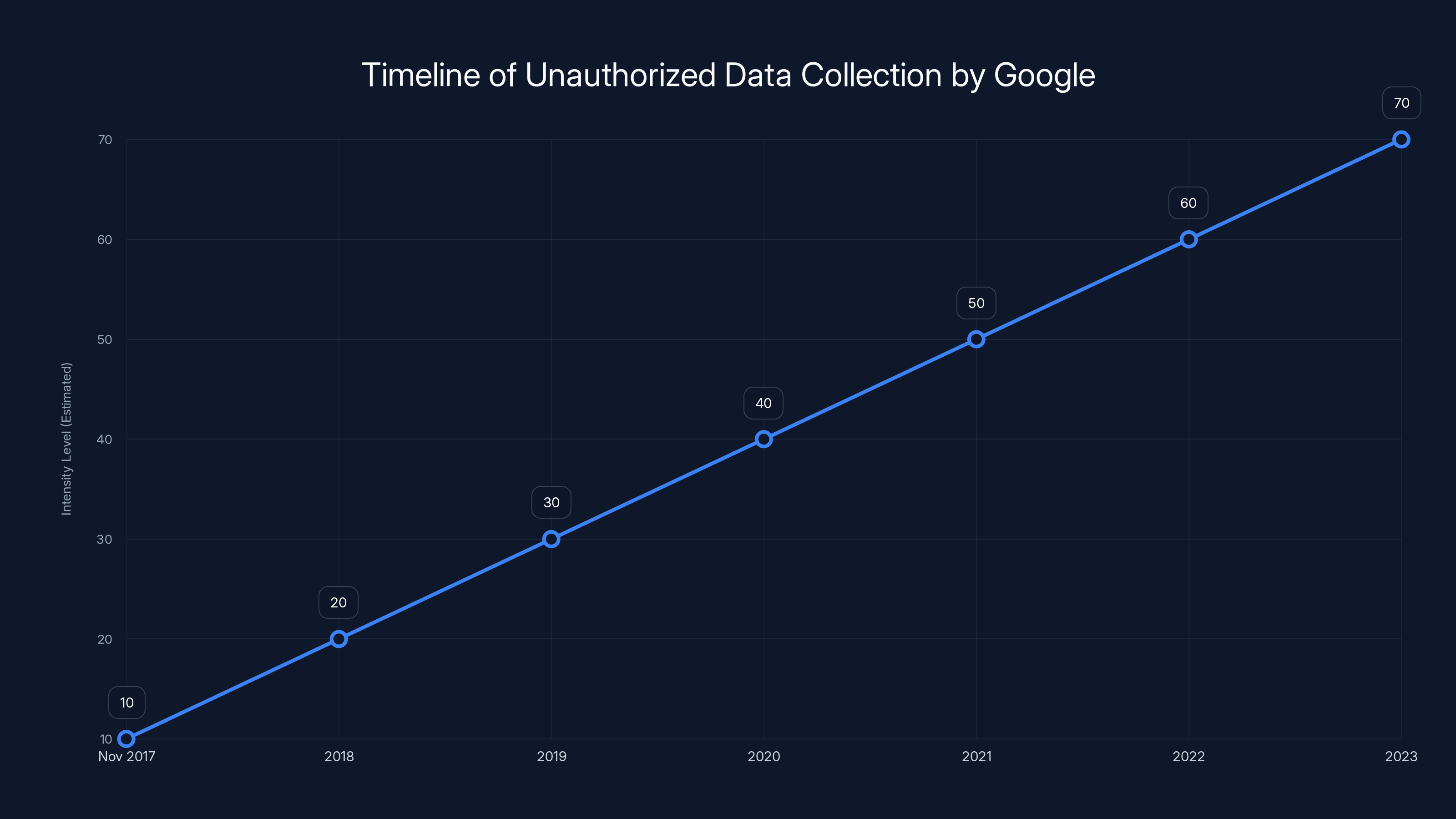

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in unauthorized data collection intensity by Google from 2017 to 2023. The exact end date of the practice remains unspecified.

Injunctive Relief: Will Google Actually Change Its Practices?

The settlement includes more than financial penalties. Google agreed to implement specific privacy improvements going forward. This "injunctive relief" theoretically ensures that the company can't simply pay fines and continue the same behavior.

The terms require Google to provide clearer disclosure about cellular data collection. When users set up Android devices or adjust privacy settings, Google must explain that cellular metadata gets collected for location purposes. Users must receive affirmative choices about whether to allow this. Previously, the company buried such disclosures in dense terms of service documents that nobody reads.

Google also agreed to create new technical controls allowing users to opt out of cellular data collection. These controls should work similarly to location service toggles. Users should be able to disable cellular data harvesting without affecting other device functionality.

The real question is enforcement. The settlement establishes oversight mechanisms and requires Google to report compliance to the court. But courts rarely aggressively police technology company behavior. Regulatory agencies lack the technical expertise to verify that Google's new systems actually work as claimed. If Google implements these changes superficially, then reverts to problematic practices years later, the court might not notice.

This enforcement weakness explains why subsequent settlements become necessary. Google faced privacy lawsuits throughout the 2010s as well. The company made commitments in earlier settlements, then was caught violating user privacy again. The cycle repeats because the cost of violations remains lower than the cost of genuine privacy protection.

For injunctive relief to actually work, it requires meaningful penalties for violations. If Google conceals new privacy abuses, the court should impose substantial fines rather than accepting explanations and promises to do better. So far, courts have been reluctant to escalate penalties for repeat violations.

Comparison to Previous Google Settlements and Industry Standards

This settlement exists within a context of repeated Google privacy violations. Comparing it to previous settlements illustrates whether Google is facing genuinely increased accountability or simply paying the cost of doing business.

In 2012, Google agreed to a

In 2020, Google agreed to a $39.5 million settlement with state attorneys general regarding deceptive privacy practices. Again, location tracking formed the core of the complaint. In 2022, Google faced investigations for continuing to collect location data from users who thought they'd disabled it—the exact same practice from five years earlier.

This pattern reveals something important: individual settlements don't change Google's behavior. The company responds by changing specific practices, then finding new ways to collect the same data. The new cellular data collection alleged in this settlement represents Google's attempt to work around tighter controls on traditional location tracking.

Industry comparison is illuminating. Facebook faced a $5 billion FTC settlement in 2019 for Cambridge Analytica data misuse. Yet Facebook continues building detailed behavioral profiles on billions of users. The company simply became more transparent about it. Amazon faced investigations for AWS data exposure but continues storing customer data with comparable security controls. Microsoft dealt with email server vulnerabilities but hasn't restructured its security approach fundamentally.

The pattern across Big Tech is consistent: settlements impose costs, companies adjust practices marginally, new violations emerge within years. True behavior change would require settlements large enough to threaten profitability or regulatory structures so robust that companies can't hide violations. Neither currently exists.

Why Android Users Should Care (and iOS Users Too)

Android users directly affected by this settlement obviously care about compensation. But the implications extend far beyond the immediate class action.

First, iPhone users shouldn't feel smug. Apple has faced comparable privacy lawsuits and settlements. The company was caught continuing to scan user photos for CSAM (child sexual abuse material) after promising not to. Apple claims privacy as core brand identity, yet systematically violates user expectations. iOS users probably face less flagrant data collection than Android users, but the difference is one of degree, not kind.

Second, this settlement affects all smartphone users because it establishes legal precedent and practical examples of corporate accountability. Each successful data collection lawsuit makes subsequent suits easier and more costly. Companies eventually get the message that privacy violations have real financial consequences. This settlement pushes that needle slightly in the right direction.

Third, the conversion framework could reshape how all tech companies approach data. If courts consistently recognize user data as property that companies can't simply take, it changes the fundamental economics of tech. Companies would need explicit compensation arrangements with users or face litigation. That's a genuinely different business model than today's surveillance capitalism.

Finally, settlements drive innovation in privacy technology. Companies facing constant litigation have incentives to develop better privacy protections, more granular controls, and clearer disclosures. The settlement market, flawed as it is, creates some pressure toward better practices.

What Happens Next: Implementation and Potential Appeals

The settlement remains preliminary. It requires final court approval before money actually changes hands or new Google practices go into effect. This approval process can take months or longer.

First, the court must hold a fairness hearing where the judge evaluates whether the settlement treats the class fairly and adequately. Attorneys from both sides present their positions. Optionally, class members can object to the settlement. If many people object, it might require renegotiation. This fairness hearing typically occurs within 3-6 months of the preliminary settlement announcement.

Google could appeal the settlement if the company believes the terms are unfavorable. More likely, plaintiff attorneys could appeal if they believe they settled for less than they could have obtained through trial. These appeals extend the process by months or years.

Once the court approves the settlement, a claims administrator takes over. This is a third-party company (often Rust Consulting or a similar firm) that manages the settlement distribution process. The administrator creates procedures for determining eligibility, processing claims, and mailing checks. This administrative phase typically takes 6-12 months or longer, depending on claim volume.

Google will implement its privacy commitments gradually. The company likely has 6-12 months to roll out new disclosure requirements and user controls. Monitoring compliance will fall to the court or a court-appointed monitor, though this oversight often proves minimal in practice.

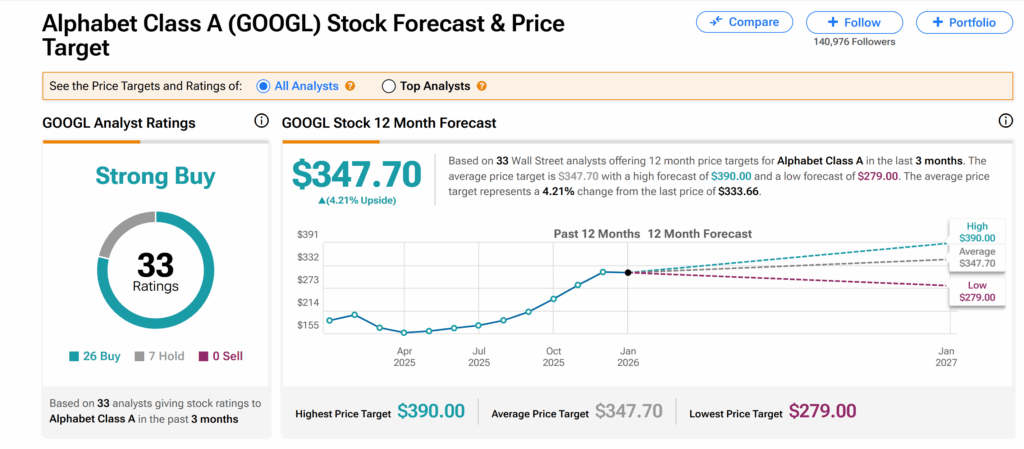

Ultimately, this settlement probably won't be Google's last. The company continues experimenting with new data collection methods, and regulators continue investigating. Within 3-5 years, expect additional privacy settlements as new violations surface. The legal reckoning with Big Tech is ongoing, not concluded.

FAQ

What data exactly did Google collect illegally?

Google collected cellular metadata—information about which cell towers Android phones connected to, signal strength, network type, and other technical details—without explicit user consent. The company used this data to pinpoint user locations even when location services were disabled. This data flowed silently in the background and served Google's marketing and product development purposes rather than benefiting individual users.

How do I know if I qualify for the settlement?

You qualify if you owned an Android device connected to a cellular network between November 12, 2017, and the date Google ceased the data collection practice. Once the settlement receives final court approval, a claims administrator will establish formal eligibility procedures. You'll need to provide information about the device, the carrier, and the time period of ownership. The settlement notice, when it arrives, will include specific instructions for filing your claim.

How much money will I actually receive from the settlement?

The settlement allocates

Why does Google use the conversion legal theory rather than privacy laws?

Conversion is a property law concept that applies nationwide consistently, whereas privacy laws vary by state. By framing data as property that users own, attorneys created a legal theory that works in every jurisdiction and doesn't depend on interpreting specific privacy statutes. Conversion also doesn't require proving that Google violated explicit legal prohibitions—just that the company took property without permission. This made the case stronger and more difficult for Google to defend.

Will this settlement actually prevent Google from collecting data this way in the future?

Partially. The settlement requires new privacy disclosures and user controls, which should prevent completely hidden data collection. However, the company can still collect data from users who affirmatively allow it. Enforcement of these injunctions depends on court monitoring, which tends to be minimal. History suggests that settlements rarely prevent tech companies from finding new ways to collect similar data, just through different technical means. Real behavior change would require much larger settlements or stronger regulatory oversight.

What about cellular carriers—are they responsible too?

The settlement focuses entirely on Google, but carriers presumably cooperated with data collection or at least enabled it by providing access to cellular metadata. The settlement doesn't clarify carrier involvement, which represents a significant gap. Android users might have separate claims against carriers, though no major carrier settlements have been announced yet. If you're interested in holding carriers accountable, follow up with your state's attorney general office.

How do I file my claim when the settlement is approved?

Once the settlement receives final court approval, a claims administrator will send notice to all affected users if they can be identified through device registration records. The notice will include instructions for filing your claim, either online through a website, by mail, or potentially by phone. Be prepared to provide details about your Android device, the carrier, and the time period you owned it. Keep documentation like carrier bills, phone purchase receipts, or email confirmations that might help prove eligibility.

Will my Android phone have new privacy features as a result of this settlement?

Yes. Google must implement new controls allowing users to disable cellular data collection and must provide clearer disclosure about this practice. Look for new toggles in Android's location and privacy settings that specifically address cellular metadata. These features should appear within 6-12 months of the settlement's final approval. However, Google can still collect this data from users who explicitly allow it, so these controls are opt-out rather than opt-in by default.

Is Apple facing similar liability for iOS location tracking?

Apple has faced privacy investigations and settlements, though not specifically for this cellular metadata collection method. The conversion legal theory could theoretically apply to Apple if the company were found collecting location data without consent. However, Apple's tight control over the iOS ecosystem and more restrictive permission architecture make this particular violation less likely. Still, Apple faces other privacy scrutiny from regulators and could face future settlements.

What should I do about my privacy on Android right now?

Immediately review your location settings in Android's privacy menu. Go to Settings > Location and examine which apps have location permission. Disable location permissions for apps that don't need them. Turn on location history pause to stop Google from storing your location timeline. In Settings > Apps & notifications > Permissions, review which apps have access to phone status and identity information. Finally, consider using a privacy-focused custom ROM or degoogled Android variant if privacy is a high priority. For most users, granular permission management and regular audits provide meaningful protection.

Looking Forward: What This Settlement Means for Data Privacy

This Google settlement isn't the end of the data collection story. It's a milestone in an ongoing legal evolution that's slowly making privacy violations more expensive.

The most significant long-term impact might be establishing the conversion framework as a viable approach for tech privacy litigation. If appellate courts uphold this theory, it opens entirely new pathways for holding companies accountable. Every major tech company collects user data without explicit consent. Every company benefits from that data. If courts recognize that data represents property, tech companies' business models fundamentally change. That's genuinely transformative.

Regulatory responses will likely follow. The FTC could propose new rules specifically requiring data ownership transparency or compensation. State attorneys general could pursue similar conversion claims against other tech companies. The enforcement mechanisms are likely imperfect, but the direction is toward greater accountability.

For individual users, the immediate lesson is clear: read settlement notices, file claims when eligible, and audit your privacy settings regularly. Tech companies respond to consequences, not principle. Settlements create consequences. As settlements grow larger and more frequent, companies gradually adjust behavior.

The broader lesson is that privacy in the digital age requires constant vigilance. No company will voluntarily respect your data unless legal pressure compels them. The combination of legal challenges, regulatory attention, and user awareness slowly shifts the balance of power. This settlement represents incremental progress in that direction—not revolutionary, but measurable.

Google will continue processing location data. The company will continue running the world's most sophisticated advertising system. But now the company must be more transparent about those practices and provide users genuine control. That's not perfect privacy protection, but it's better than invisible tracking without recourse. For millions of Android users who unknowingly participated in seven years of unauthorized surveillance, this settlement offers both compensation and a small measure of justice.

Key Takeaways

- Google will pay 100 each

- The lawsuit introduced the legal theory of 'conversion' to tech privacy litigation, arguing user data is property that Google wrongfully took without permission

- Google collected cellular metadata invisibly in the background without explicit user consent, even when location services were disabled, then used it for marketing and product development

- This represents one of the largest payouts in data collection litigation history and comes amid a broader pattern of Google privacy settlements totaling hundreds of millions of dollars

- The settlement requires Google to implement new privacy controls and clearer disclosures, though enforcement depends on court monitoring that historically proves minimal for tech companies

Related Articles

- Smartphones Share Your Data Overnight: Stop It Now [2025]

- Apple's 2nd Gen AirTag: Range, Features & Why the Keyring Hole Still Matters [2025]

- Google's $68M Voice Assistant Privacy Settlement [2025]

- Best Bluetooth Trackers for iPhone & Android [2025]

- Apple AirTag 2025: Enhanced Range, Louder Speaker, Better Tracking [2025]

- TikTok's New Data Collection: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]

![Google's $135M Data Collection Settlement Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-s-135m-data-collection-settlement-explained-2025/image-1-1769695638488.jpg)