Google's $68 Million Voice Assistant Privacy Settlement: What It Means for Your Privacy [2025]

Introduction: The Hidden Cost of "Always Listening"

Imagine this scenario: you're having a casual conversation with a friend about a new laptop you've been thinking about buying. You never searched for it online. You didn't tell anyone about it. Yet hours later, laptop ads start flooding your social media feed. Coincidence? Not quite.

This exact frustration sparked a major class-action lawsuit that forced Google to write a check for $68 million. But here's what makes this settlement genuinely important: it's not just about Google. It's about a fundamental shift in how we think about voice assistants, privacy, and the implicit contracts we unknowingly agree to when we use technology.

Voice assistants have become ubiquitous. There are over 4.9 billion voice assistant devices globally, and they're integrated into smartphones, smart speakers, cars, and home devices. They've made our lives more convenient. They've also made our private conversations valuable commercial assets.

The settlement doesn't fix the underlying problem. It doesn't reverse what happened. It doesn't prevent future incidents. What it does do is acknowledge something crucial: Google's voice assistant was picking up conversations it shouldn't have, and the company profited from that intrusion.

In this comprehensive guide, we'll break down exactly what happened, why regulators and courts decided Google needed to pay, what the settlement actually covers, and most importantly, what you should do to protect your own privacy in a world where our devices are always listening.

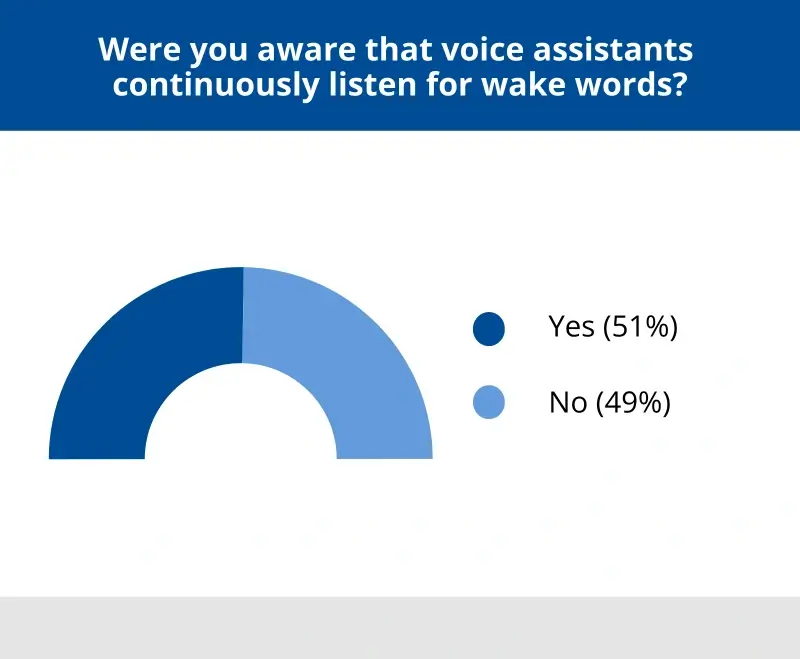

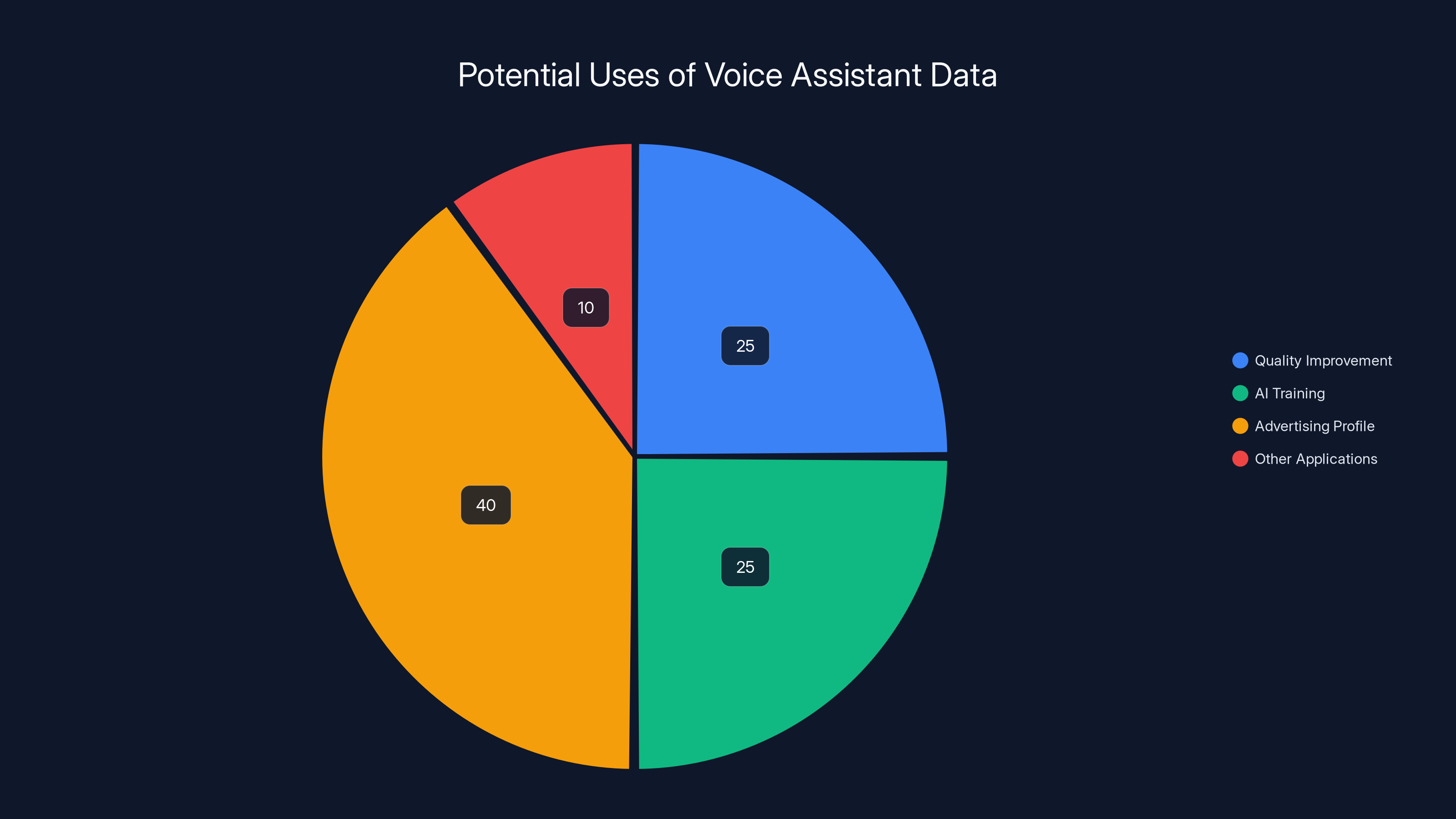

Voice data is primarily used for advertising profile refinement, highlighting its commercial value. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- $68 Million Settlement: Google agreed to pay to resolve claims that Google Assistant inappropriately recorded private conversations

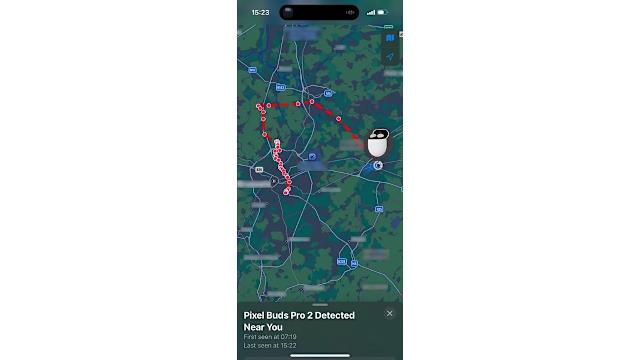

- How It Happened: The voice assistant misheard wake words, activated without permission, and used overheard conversations for targeted advertising

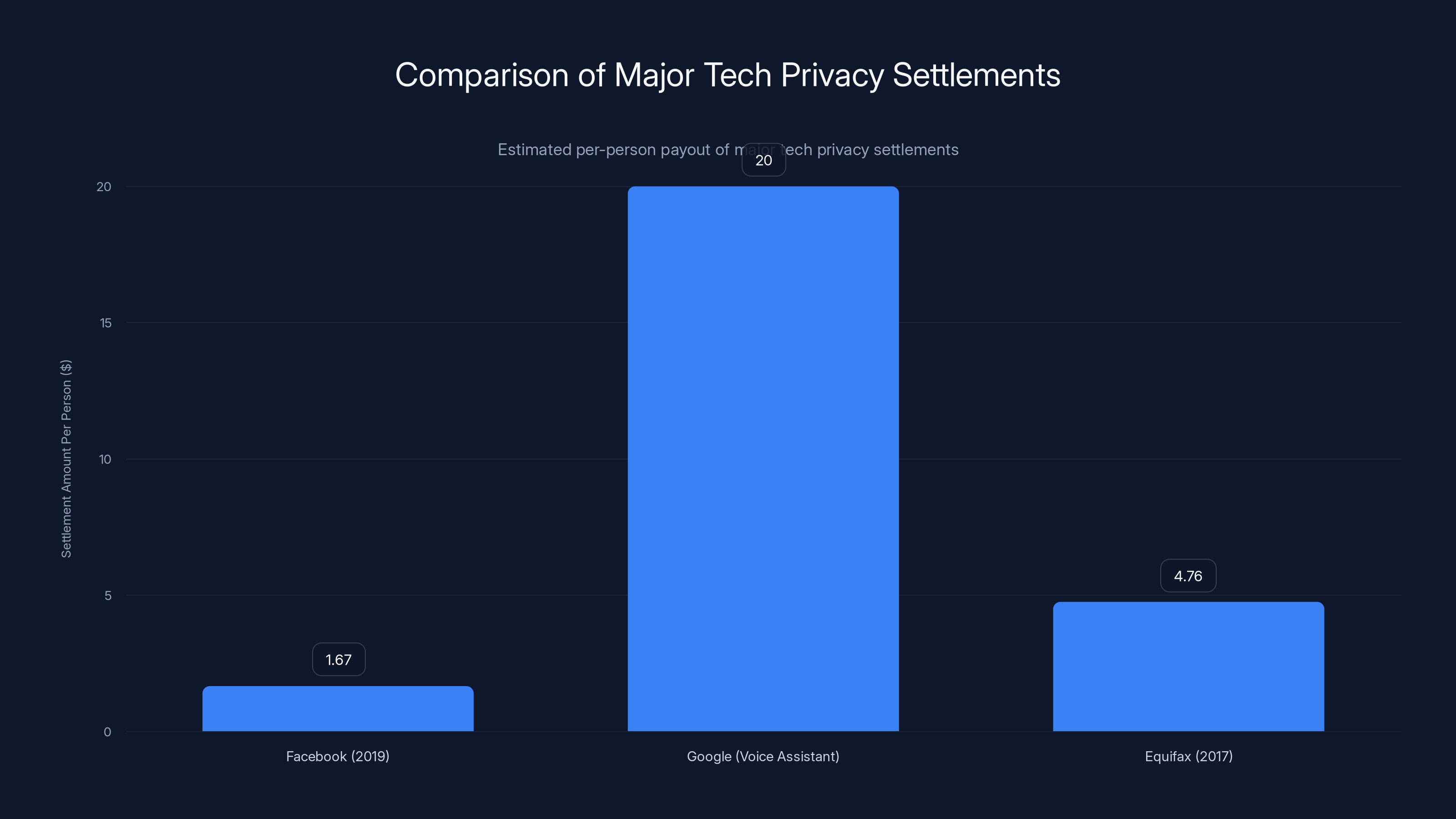

- Class Action Impact: Millions of smartphone users affected; individual payouts of approximately $20 per affected device

- Industry Pattern: Apple faced similar allegations with a $95 million settlement in January 2025, suggesting this is a widespread problem

- What Changed: Google is transitioning away from Google Assistant to focus on Gemini, but privacy issues may persist

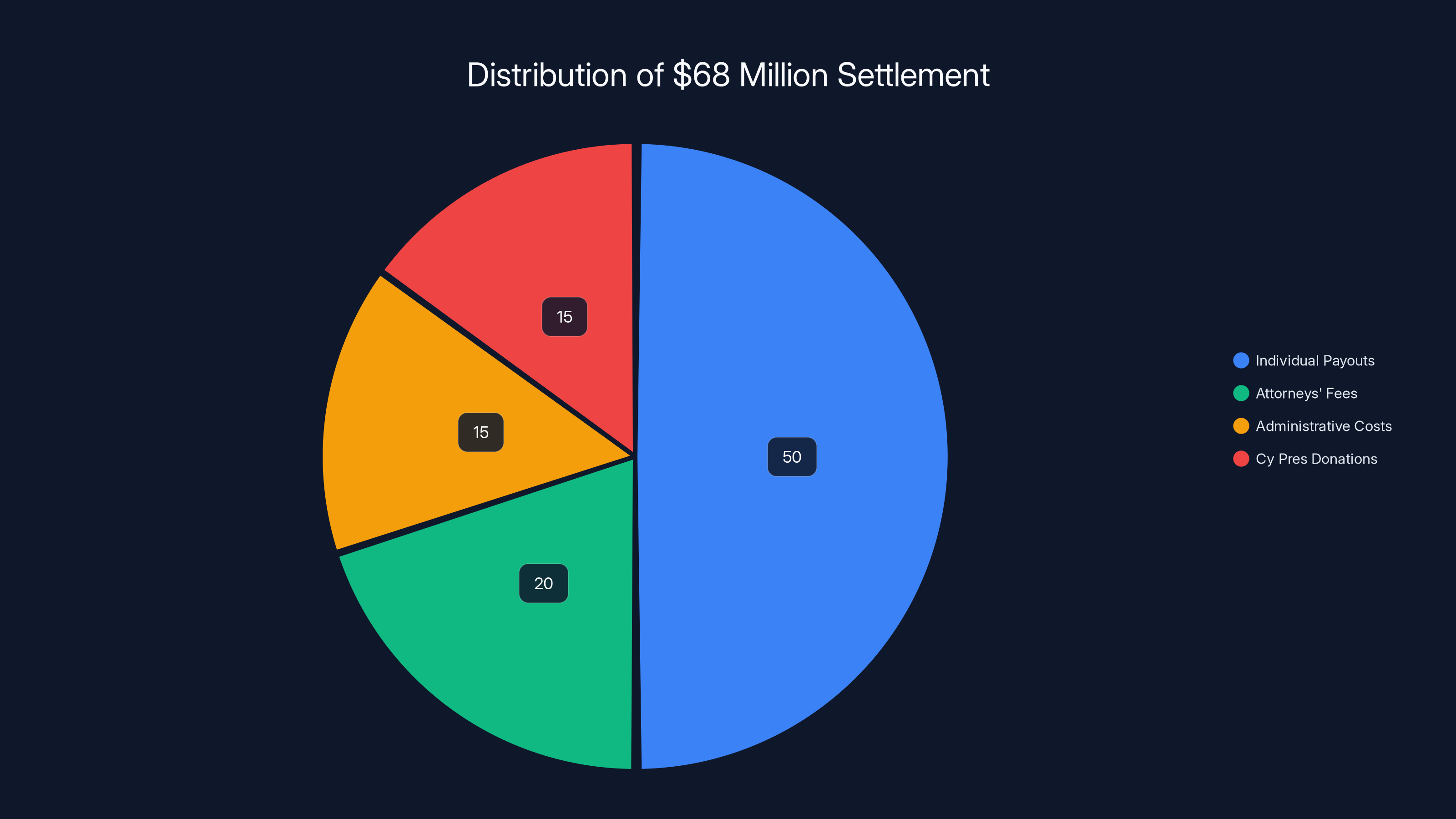

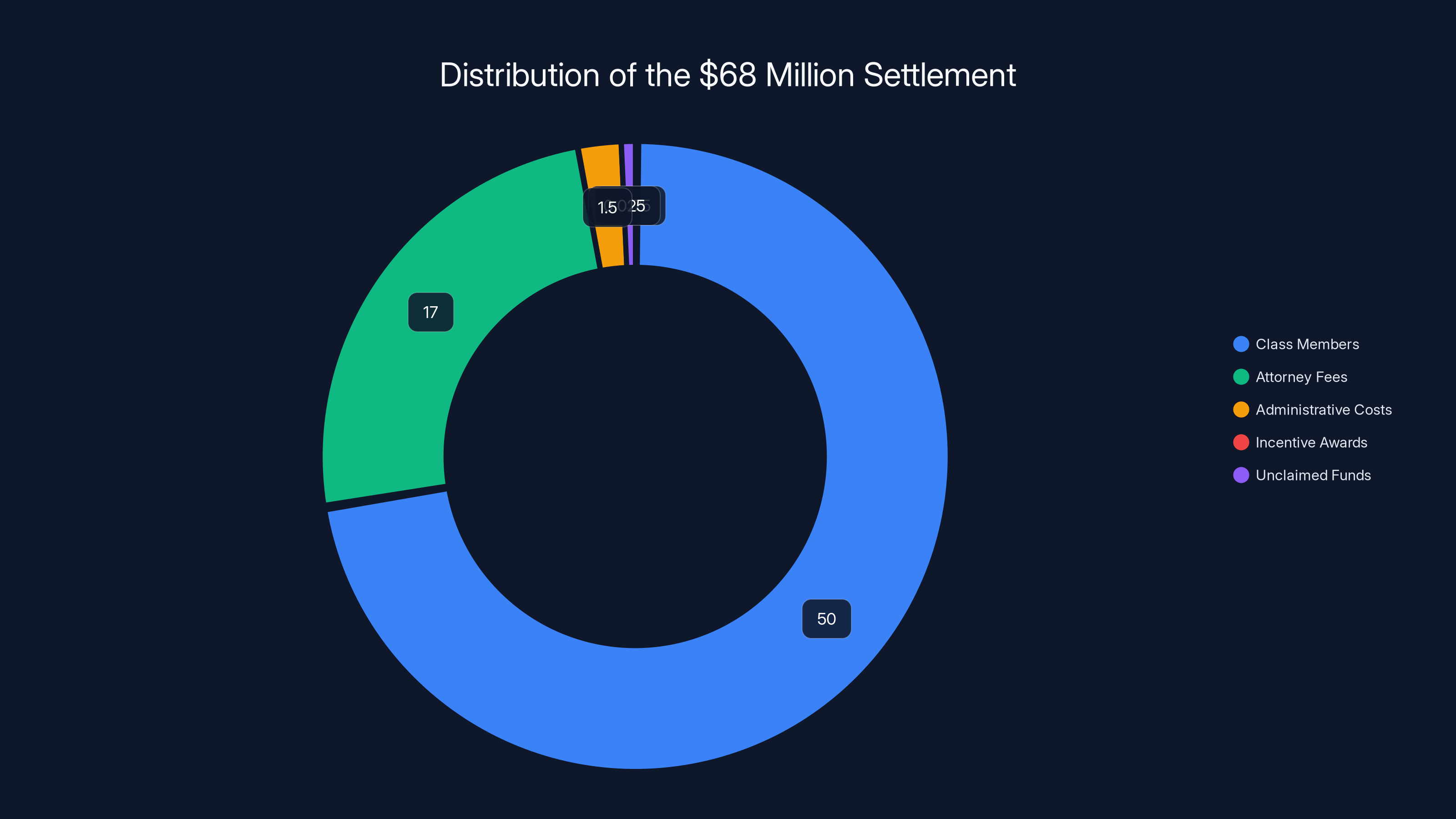

Estimated data shows that individual payouts constitute about 50% of the $68 million settlement, with the rest allocated to fees and donations.

Understanding the Google Assistant Privacy Violation

How Wake Words Became Privacy Nightmares

Voice assistants operate on a simple principle: they listen for specific wake words. Say "OK Google" or "Hey Google," and your device springs to life, ready to take your commands. In theory, it only records after you say the wake word. In practice, the system is far more complex and far more fallible.

The lawsuit alleged that Google Assistant was suffering from what's called false wake-word triggering. This means the system was picking up conversations that merely sounded like wake words without the user actually invoking the assistant. A sentence like "okay, Google Maps directions to the grocery store" might trigger the device. Someone talking about "hey, Google something interesting about that movie" could activate recording. Common word combinations that phonetically resemble wake words could cause accidental activation.

Once activated, the device would begin recording. Your conversation. Your location. Your browsing behavior. Your health concerns mentioned in passing. Your relationship status. Your financial worries. All of it was captured by microphones designed to listen.

What made this particularly egregious is what happened next. Google didn't just delete these unintended recordings. The company allegedly used them. Personal information that users had no idea was being collected became the foundation for targeted advertising profiles. Someone offhandedly mentioned their arthritis pain to a family member, and suddenly they're seeing ads for pain relief medication. Someone discussed their job dissatisfaction with a partner, and recruitment ads start appearing.

The core argument in the lawsuit was straightforward: Google built a profit center on conversations obtained through negligence or intentional design, without meaningful consent from users. The company benefited financially from privacy violations. Users had no idea their private moments were being monitored, transcribed, and monetized.

The Technical Reality Behind False Activations

Understanding why voice assistant systems fail requires understanding how they actually work. Modern voice assistants use a two-stage detection system. The first stage is what's called a low-power model that runs constantly on your device. This model listens for anything that might be a wake word. It's intentionally sensitive because missing a legitimate wake word would frustrate users.

That sensitivity is the problem. A low-power model designed to catch legitimate wake words will inevitably catch false positives. It's a technical trade-off: you can be more accurate and miss some real wake words, or you can be more permissive and catch some false activations. Google apparently leaned toward permissiveness.

When the low-power model detects something that might be a wake word, it triggers the second stage. Audio gets sent to Google's servers for more sophisticated processing. At this point, a more accurate model on the server side should verify whether a real wake word was actually spoken. If it wasn't, no recording should be stored.

But here's where it gets murky. Even if the server-side verification correctly determined that no real wake word was spoken, the audio had already been transmitted and processed. Security researchers have shown that even audio sent for verification but ultimately rejected can be retained by companies for "quality improvement" purposes. The lawsuit essentially alleged that Google was keeping these rejected recordings and using them for advertising purposes.

Why Users Couldn't Stop It

One of the most frustrating aspects of this situation is that disabling the feature wasn't straightforward. On many Android devices, Google Assistant is deeply integrated into the operating system. While you could disable the "Hey Google" wake word detection, the assistant could still be activated by pressing the home button or swiping from the corner of the screen.

Moreover, Android is Google's ecosystem. The company controls the OS, the default apps, the privacy settings, and how they're presented to users. Most users don't know about these privacy settings. Many don't know they can disable voice activation. The settings are buried in menus, explained in jargon-heavy language, and presented in a way that emphasizes functionality rather than privacy.

Users essentially faced a choice: accept the convenience and the privacy risks, or abandon a core feature of their phones. That's not really a choice at all. It's coercion through technical design.

The Settlement Timeline and Legal Process

How the Lawsuit Came Together

Privacy lawsuits against tech companies typically start the same way. Someone notices something suspicious. They talk to others. A pattern emerges. A lawyer takes the case. In this instance, users noticed the ads following their conversations. They compared notes on social media. The anecdotes began to form a coherent narrative: our phones are listening when they shouldn't be.

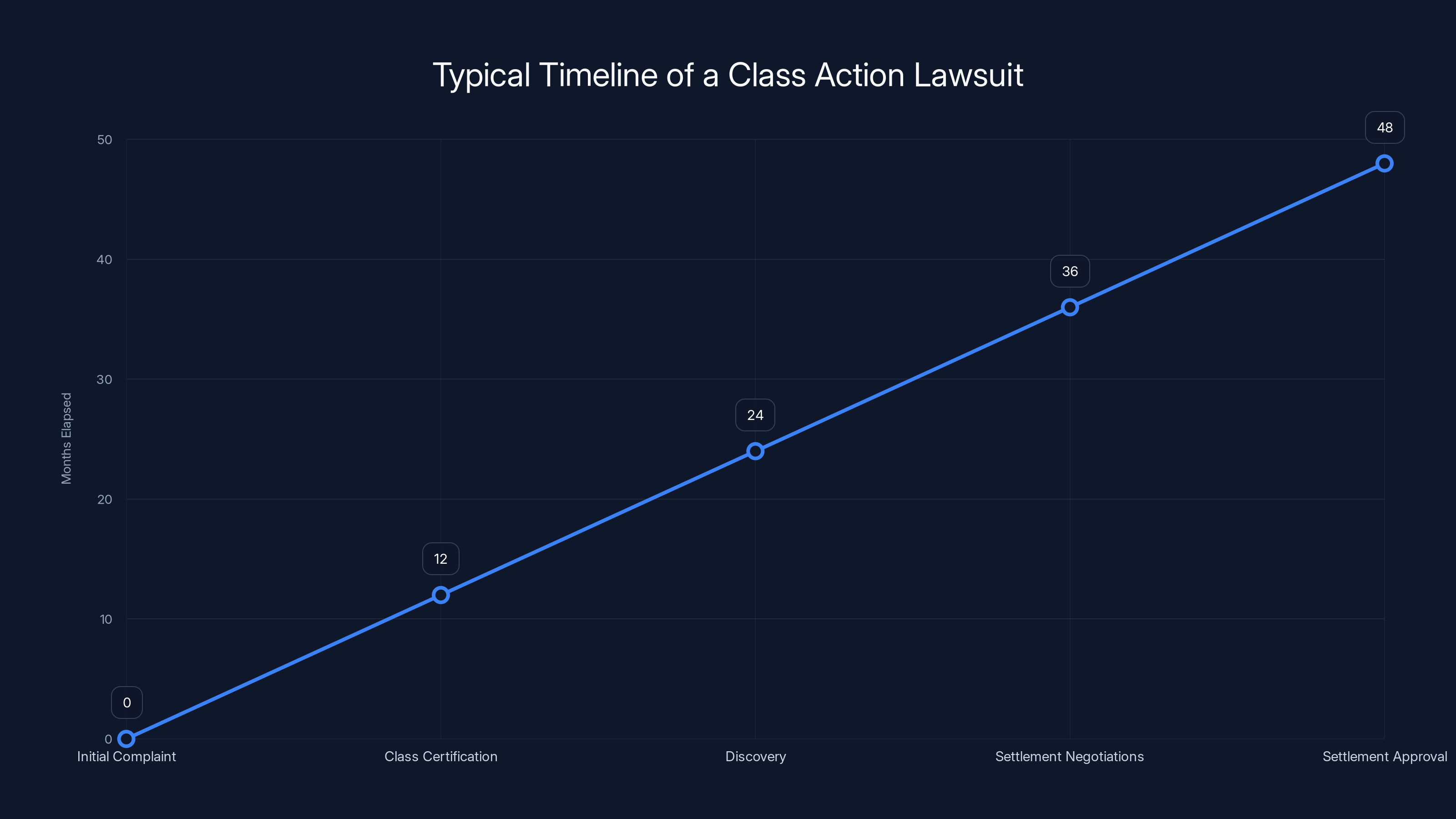

The class action was filed years before this settlement. Unlike individual lawsuits where one person sues a company, class actions consolidate thousands or millions of similar claims into a single case. This makes it economically viable to pursue claims that would be too small to litigate individually. No one would spend

The case worked its way through the court system. Legal discovery happened, where both sides exchanged documents and evidence. Depositions were taken. Expert witnesses were prepared. The normal process of litigation unfolded.

Why Google Decided to Settle

According to court documents and reporting by Reuters, Google didn't admit wrongdoing. This is standard in settlements. The company denied liability while simultaneously agreeing to pay $68 million. This structure allows companies to avoid admitting guilt, which could be used against them in other cases or regulatory proceedings.

But why settle at all if Google believed it had done nothing wrong? Several factors came into play. First, litigation is expensive. Both the direct legal costs and the opportunity costs of executives' time, public relations damage, and institutional distraction all add up. Second, the case had merit. Evidence existed that voice assistant false activations were occurring and that this data was being used for advertising purposes. Third, a trial was risky. A jury of regular people, people who use Google products and had heard about privacy concerns, might decide to award much larger damages.

Going to trial could have resulted in a verdict of

Judge Beth Labson Freeman's Role

The settlement required approval from U. S. District Judge Beth Labson Freeman. Her role wasn't to assess guilt or innocence, but to determine whether the settlement was fair, reasonable, and adequate for the class members. She examined whether the settlement was the product of genuine arm's-length negotiation, whether the fee arrangement was reasonable, whether the payment plan was fair, and whether the privacy protections were meaningful.

This judicial review process is a critical safeguard. Without it, companies and plaintiffs could collude to settle for pennies on the dollar, with most of the settlement going to lawyers and administrators rather than victims. Judge Freeman's approval meant that she believed the settlement genuinely attempted to make affected users whole.

The

How the Settlement Breaks Down: Where the $68 Million Goes

The Math of Distributed Justice

Here's where the settlement gets complicated. Sixty-eight million dollars sounds substantial. But it needs to be distributed among potentially millions of affected users. The lawsuit was a class action, meaning everyone with an affected Google device during the relevant time period is theoretically eligible.

Estimates suggest the class could include between 3 and 5 million users. If you divide

But that's not how the full breakdown works. The $68 million must cover:

Settlement Payout to Class Members: Approximately

The breakdown reveals something uncomfortable about class action settlements. They're mathematically structured to benefit lawyers more than class members. A $20 payout per person is meaningful to some but barely noticeable to others. The lawyers who litigated the case for years earn millions. The administrative costs are substantial. The system is designed to make lawsuits economically viable for law firms, which requires significant compensation for their work.

Comparing to Apple's Siri Settlement

Apple faced identical allegations regarding Siri. The core complaint was that Siri was recording conversations without users realizing it, transcribing that audio, and the company was using it for purposes beyond what users agreed to.

Apple's settlement in January 2025 was larger:

That figure reveals something important: regulators don't believe voice assistant privacy violations are worth massive individual compensation. They view it as a widespread problem that requires settlement and nominal payment rather than a catastrophic harm requiring punitive damages. Compare this to data breach settlements where stolen credit cards or medical records might be valued at

This ranking of harms is worth questioning. Is knowing that someone overheard a private conversation really worth less than unauthorized access to a credit card number? Many would argue that intimate personal information discussed in private conversations is more valuable and more sensitive than financial data.

What Actually Changes: The Real-World Impact

Will False Activations Stop?

The settlement doesn't include mandatory technical changes. Google isn't required to redesign its voice detection system. It isn't mandated to increase accuracy thresholds or reduce false activation rates. There's no requirement that Google implement opt-in voice recording with explicit user consent instead of the current opt-out system.

This is a significant limitation of the settlement. It's a financial penalty, not a structural fix. Google pays money and moves on. The underlying system that enabled false activations remains in place.

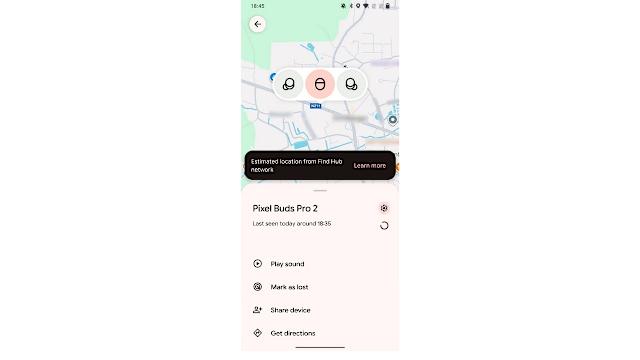

Google has been transitioning away from Google Assistant, shifting focus to Gemini, its larger AI model. This transition might reduce some privacy concerns, but it's not driven by the settlement. It's driven by strategic business decisions. Gemini is more powerful, more profitable, and more aligned with Google's AI vision. The settlement probably accelerated the timeline, but it didn't force the change.

Deletion of Illegally Obtained Audio

One thing the settlement likely does require is deletion of audio recordings that were collected through false activations. Google must presumably purge its databases of these unintended recordings. The company can't continue to use them for advertising purposes.

This is important but limited. The audio from false activations, once used to create advertising profiles, has already shaped data associated with user accounts. Even if Google deletes the original audio files, the data derived from that audio might persist. If a false activation led to the inference that you have arthritis, and that inference was added to your advertising profile, deleting the recording doesn't automatically remove the inference.

Moreover, the settlement covers a specific time period. Audio recorded outside that period might not be covered. And audio that Google claims was legitimately recorded (through false positives in its categorization) might not be deleted.

Notification and Transparency Requirements

Settlement terms typically include requirements that the defendant notify class members about what happened and what they can claim. Users will receive notifications explaining the case and providing instructions for claiming their settlement payment.

These notifications can be informative or can be designed to confuse. The company often wants minimal claims rates because unclaimed settlement money sometimes reverts to them or can be allocated to cy pres recipients that the company finds favorable. Clear, accessible notification language maximizes claim rates. Complicated language minimizes them.

Based on the settlement structure and the size of the class, Google probably undertook at least a modest notification effort. Whether that notification actually reached most affected users remains to be seen.

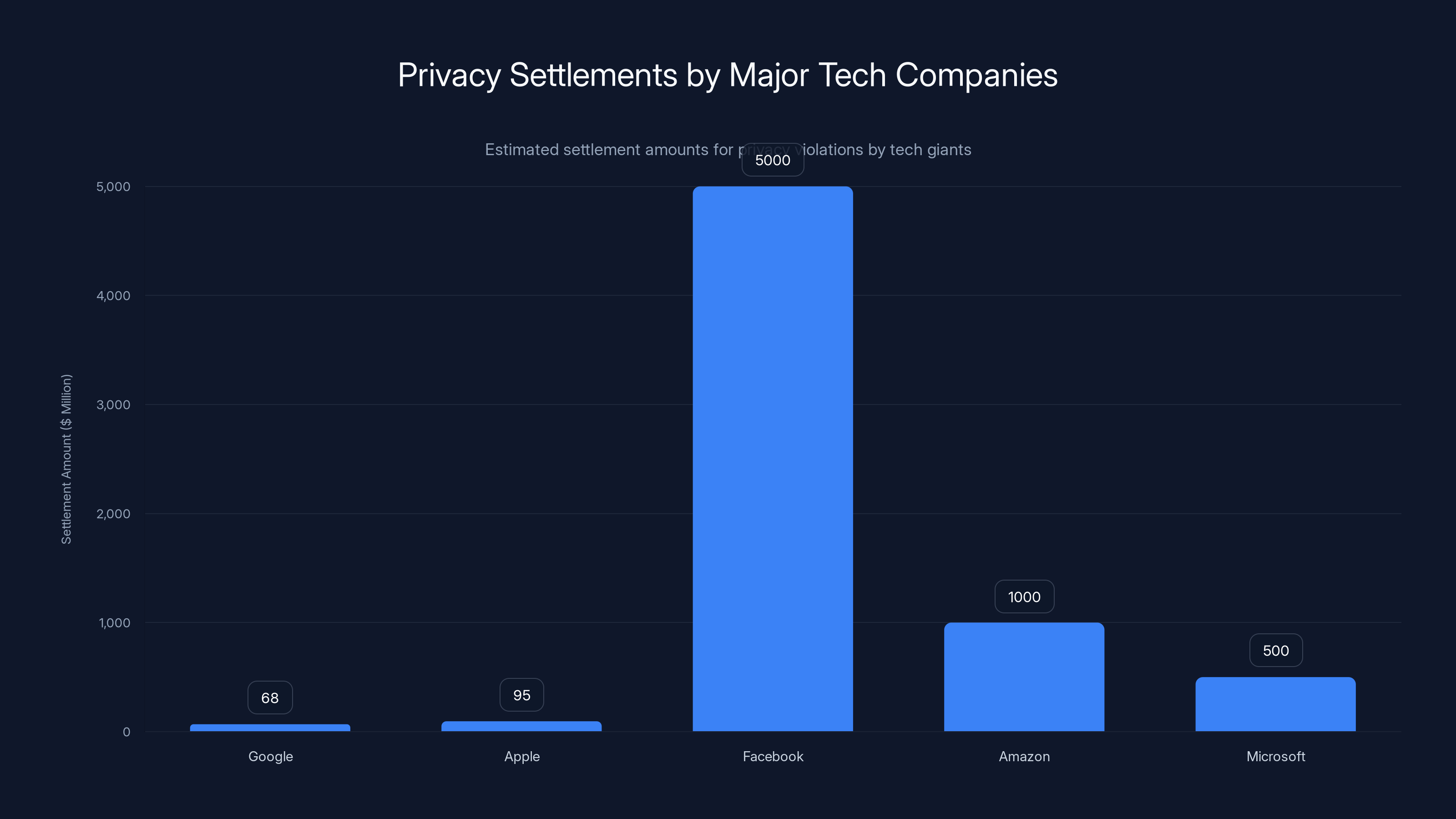

Estimated data shows significant settlements by major tech companies for privacy violations, highlighting ongoing privacy concerns.

The Broader Privacy Crisis in Voice Assistants

Why Voice Assistants Are Inherently Problematic

Voice assistants create a fundamental tension. To work effectively, they must listen constantly. To protect privacy, they must listen minimally. You can't have both.

Current voice assistant design attempts to square this circle through local processing. The device listens on-device for wake words without sending audio to the cloud. Only after detecting a wake word does it transmit audio to servers for processing. In theory, this protects privacy by keeping conversations out of the cloud until the user explicitly activates the device.

In practice, it fails repeatedly. False activations happen. Accidental transmissions occur. Once audio is in the cloud, it's potentially used for multiple purposes. Quality improvement, AI training, advertising profile refinement, and other applications. Users don't understand this chain of events, and companies don't clearly explain it.

The root cause isn't technical incompetence. It's economic incentive. There's an enormous amount of money available to companies that can target advertisements with precision. The better a company understands your interests, needs, fears, and desires, the more effectively it can sell you things. Voice data is extraordinarily valuable for understanding humans.

Companies like Google are fundamentally advertising businesses. Google's primary revenue source is advertising. The company doesn't charge users for Gmail, Maps, Search, or Android. Users are the product. Their attention is sold to advertisers. Their data is sold to advertisers. Their private conversations become raw material for this commercial operation.

In this context, voice assistant privacy violations aren't bugs. They might be features. They're profitable.

The Regulatory Response Inadequacy

The settlement is technically a regulatory victory. The FTC approved the settlement. The court approved it. The system worked as designed. But did it actually solve anything?

Regulations around voice assistants remain weak. The FTC has authority to challenge unfair or deceptive practices, but it doesn't have the power to mandate design changes or ban technologies. It can levy fines and require settlements, but those financial penalties, while large in absolute terms, are small relative to the profits generated through privacy violations.

Consider the math. If Google collects voice data worth

Some regulators have called for more aggressive enforcement, including fines calculated as a percentage of revenue (which could be in the billions for tech companies) or prohibition of certain practices. But the U. S. regulatory environment remains relatively permissive compared to the EU's approach.

International Regulatory Pressure

Europe has been moving faster on tech regulation. The Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act impose more stringent requirements on how large tech platforms operate. The EU also recently opened an investigation into Grok, an AI system built by X (formerly Twitter), suggesting that regulators are scrutinizing new AI tools more carefully.

In the U. S., settlement-based enforcement remains the primary mechanism. Companies pay money, and enforcement action closes. They might change some practices, but often the change is minimal.

Protecting Yourself: Voice Assistant Privacy Best Practices

Disabling Voice Activation

The most effective privacy protection is disabling voice activation entirely on devices where you don't actually need it. If you rarely use voice commands on your smartphone, turn off "OK Google" detection. This stops the device from constantly listening for wake words.

On Android, navigate to Settings > Google > Manage your Google Account > Data & Privacy > Web & App Activity. You can disable Web & App Activity and also toggle off the Voice Activation option. On some phones, there's a separate Google Assistant settings menu where you can disable voice activation.

On Apple devices, similar settings are in Settings > Siri & Search. You can disable "Listen for Hey Siri" on individual devices. You can also disable the ability to activate Siri with physical buttons.

The trade-off is clear. You lose convenience. You can't say "OK Google, set a timer" or "Hey Siri, what's the weather." These voice commands are genuinely useful. The choice is between convenience and privacy.

Managing Voice Activity History

Google stores a record of voice commands you've given to Google Assistant. You can access and delete this history. Visit myaccount.google.com and navigate to Data & Privacy > Voice & Audio Activity. You'll see a timeline of voice commands Google has recorded.

Review this list. You'll likely find commands you don't remember, false activations that were recorded despite your intent, and other surprises. You can delete individual recordings or bulk-delete entire time periods.

This doesn't prevent Google from collecting future voice data, but it removes a record of past data and demonstrates to Google that you're monitoring their collection practices. It also clarifies for you just how much voice data has been collected.

Privacy Settings and Data Limiting

In addition to voice assistant settings, review your broader Google account privacy settings. Go to myaccount.google.com and click "Data & Privacy." You'll see multiple options:

- Web & App Activity: Logs your searches, app usage, and browsing history

- Location History: Tracks where your phone goes

- You Tube History: Records every video you watch

- Device Information: Collects technical data about your device

You can disable each of these. Disabling all of them is effectively disabling Google's ability to profile you comprehensively. The company will still know some things (your email address, any explicit searches you perform, any Gmail content), but it won't know everything.

Note that Google will try to convince you to keep these settings enabled. It will say features won't work without them, or your experience will be diminished. Some of this is true. Search recommendations won't be personalized. Maps won't remember your favorite locations. But the core functionality of Google's products works without comprehensive data collection.

Using Alternative Products

The most aggressive privacy strategy is abandoning Google products where feasible. Instead of Google Search, use Duck Duck Go, which doesn't track search history. Instead of Gmail, use Proton Mail, which uses end-to-end encryption. Instead of Google Maps, use Open Street Map or Apple Maps.

None of these alternatives are perfect, and they all involve trade-offs. Duck Duck Go's search results aren't as good as Google's. Proton Mail has less functionality than Gmail. Open Street Map has less detailed data than Google Maps. But for users who prioritize privacy, these trade-offs might be acceptable.

For voice assistants specifically, the alternatives are limited. Apple's Siri has faced similar privacy allegations. Amazon's Alexa has its own issues. Google Assistant is probably not dramatically worse than its competitors, just more integrated into Android phones, which makes it harder to escape.

Technical Privacy Tools

More advanced privacy protection involves technical tools like VPNs, which encrypt your internet traffic so your ISP and network operators can't see what you're doing. This doesn't protect you from Google itself, but it protects you from others snooping on your network traffic.

VPN protection has limits. It protects the content of your communications but not the metadata. Google can see that you're using Google services from a VPN, even if it can't see the specifics of your searches.

Another approach is using a Pi Hole or similar DNS filtering service, which blocks ad trackers at the network level. This prevents devices on your network from contacting advertising and tracking servers.

None of these tools are perfect, and all of them require some technical knowledge to implement properly.

Class action lawsuits can take several years to resolve, with key stages including class certification, discovery, and settlement negotiations. Estimated data based on typical cases.

Comparing This Settlement to Other Tech Privacy Cases

Facebook's Privacy Settlements

Facebook has faced multiple privacy settlements. The most famous was the $5 billion FTC settlement in 2019 regarding the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where user data was improperly shared with a political consulting firm.

When you divide

Equifax Data Breach Settlement

Equifax, the credit reporting company, paid

What's striking is that this amount is significantly larger than Google's settlement per person, despite the privacy violations being fundamentally different. In Equifax's case, financial data was stolen through negligent security. In Google's case, voice data was misused through technical failure or intentional design.

The legal system seems to value financial data breaches higher than voice privacy violations. This might reflect the fact that financial data can be directly monetized (identity theft, fraud) while voice data requires inference and inference is less certain.

Microsoft and Activision

Not all major tech settlements are privacy-related. Microsoft's pending acquisition of Activision Blizzard faced regulatory challenges, and Microsoft agreed to restrictions on game licensing and platforms to gain approval. These aren't privacy settlements but structural business changes.

What they show is that regulators can force companies to make meaningful operational changes when enforcement pressure is sufficient. In the voice assistant case, the fact that no operational changes were mandated suggests the priority was financial settlement rather than structural change.

Google's Transition Away from Google Assistant

Why Google is Abandoning Its Own Product

Google built Google Assistant over many years. The company invested billions of dollars in the technology. It integrated the assistant into Android phones, smart speakers, cars, and countless other products. And now Google is walking away from it.

The official reason is that Gemini, Google's larger language model, is more capable. Gemini can handle more complex queries, engage in more nuanced conversations, and integrate AI-powered problem-solving in ways that the older Assistant couldn't match.

But there might be a secondary reason. Voice assistant technology is fundamentally challenging from a privacy perspective. Building systems that listen constantly, even with on-device processing, creates risks and liabilities. Gemini is a different interaction model. Users actively start conversations with Gemini by opening an app and typing or speaking. It's not always listening. It's invoked on-demand.

This shift suggests that Google might be learning from the privacy lawsuits. Rather than continuing to invest in technology that creates privacy risks, the company is pivoting to models that are less problematic.

Of course, Gemini has its own concerns. It might have different privacy issues, and as it matures, users might discover problems we haven't anticipated yet.

The Impact on Existing Users

For existing Google Assistant users, this transition means less support and fewer updates for the old technology. Google isn't shutting down Google Assistant immediately, but it's clearly not a priority for future investment.

Users who have built routines, automations, and habits around Google Assistant will need to migrate to Gemini or find alternatives. This is inconvenient but probably necessary for Google to move forward.

Estimated data shows Google's voice assistant settlement had the highest per-person payout at

What the Settlement Doesn't Cover

Data Derived from False Activations

One major limitation is that the settlement addresses the recorded audio, but not the inferences drawn from that audio. If false activations led Google's systems to conclude that you have specific interests, health concerns, or behaviors, those inferences might persist even after the original audio is deleted.

Data about you exists in multiple forms. The original audio is one form. The transcript of that audio is another. The inferences drawn from that transcript are a third form. The advertising profile changes resulting from those inferences are a fourth form.

The settlement likely addresses the first two forms but not the last two. This is a significant gap.

Future Misuse of Similar Data

The settlement covers voice assistant false activations. It doesn't prevent Google from misusing data obtained through other means. The company still collects location data, search data, app usage data, and browsing data. It uses all of this information to create detailed profiles and target advertising.

The settlement is narrowly tailored to one specific problem. It doesn't address the broader business model that incentivizes privacy violations.

Non-U. S. Users

This settlement applies primarily to U. S. users whose claims fall within the jurisdiction of U. S. courts. Users in other countries might have their own legal remedies or might have no remedies at all. If Google violated the privacy of users in India, Brazil, or Indonesia through voice assistant false activations, those users might not receive settlement compensation.

This creates a two-tiered system where privacy violations have different consequences depending on where you live. U. S. and EU users have stronger legal protections than users in other regions.

The Future of Voice Assistant Privacy

Emerging Regulations

Privacy regulation is evolving. The EU's Digital Services Act imposes requirements on how large platforms handle user data. The U. S. is considering federal privacy legislation, though political division makes comprehensive regulation difficult.

More specific to voice assistants, regulators might establish rules around false activation disclosure, data retention, and inference limitations. Companies might be required to be more transparent about how voice data is used and provide users with better control over collection.

Technical Solutions

From a technical standpoint, voice assistant makers could improve privacy without sacrificing functionality. They could process more voice data on-device rather than transmitting it to servers. They could implement differential privacy techniques that add noise to data to prevent identification of individuals while still allowing pattern analysis. They could encrypt voice data end-to-end so the company itself can't access it.

None of these technical solutions are being broadly implemented. The barriers are not technical but economic. If voice data has commercial value, companies won't voluntarily make it harder to access.

Market Accountability vs. Regulatory Oversight

One argument is that the market will solve this problem. If users become concerned about voice assistant privacy, they'll switch to more private alternatives. If a company launches a privacy-first voice assistant, it will gain market share.

The evidence suggests this hasn't happened. Apple's Siri, despite privacy-focused marketing, faced the same allegations as Google Assistant. Market competition hasn't driven privacy improvements.

This suggests that either users don't care enough about voice privacy to change their behavior, or switching costs are too high, or users don't have good alternatives. Probably all three are true.

Expert Perspectives on the Settlement

Privacy Advocates' View

Privacy advocates generally view this settlement as inadequate. The $20 per person payout is seen as a trivial punishment that doesn't meaningfully compensate victims or deter future violations. The lack of mandatory technical changes means the underlying system that created the problem remains in place.

Advocates argue that settlements should be much larger, calculated as percentages of revenue, or that regulators should have power to mandate design changes, not just levy fines. They point to the EU's approach as more effective.

Industry Perspective

Tech companies argue that privacy concerns are overstated and that the balance between functionality and privacy requires some trade-offs. They contend that voice assistants provide genuine value to users and that the risks can be managed through reasonable safeguards.

The industry also argues that settlements are appropriate remedies for unintentional mistakes or design challenges, and that calling for massive punitive damages would chill innovation in voice AI.

Consumer Advocates

Consumer advocates occupy middle ground. They recognize that voice assistants are valuable but argue for better transparency, clearer opt-in mechanisms, and stronger regulatory oversight. They don't necessarily call for banning voice assistants but for making them less invasive.

Taking Action: What Users Can Do Now

If You Were Affected

If you used Google Assistant on an Android phone during the relevant class action period, you were likely affected. Watch for notification about the settlement. When the claims period opens, file a claim if the process is straightforward. The $20 payout is small, but it's better than nothing, and participating signals that you care about this issue.

More importantly, use this as an opportunity to audit your privacy settings. Review what Google knows about you and disable data collection where possible.

Broader Privacy Actions

Beyond this specific settlement, consider your overall approach to technology privacy. Do you need voice assistants on your phone? If not, disable them. Review and limit data collection on every device you own. Use strong passwords and two-factor authentication. Be skeptical of free services that make money through advertising.

None of this is easy, and none of it is foolproof. But incremental steps add up.

Advocacy

On a broader level, support privacy-focused regulation. Contact your representatives about privacy legislation. Choose products from companies that prioritize privacy. Support organizations that advocate for stronger privacy rights.

The settlement is a legal victory, but real change requires sustained pressure from multiple directions: regulation, litigation, market competition, and user preference.

FAQ

What is voice assistant false activation?

Voice assistant false activation occurs when a device mistakes a regular conversation for a wake word command and begins recording without the user's intention. For example, if someone says "Hey, Google something on the news," the device might interpret "Hey Google" as the wake word and start recording, capturing the entire conversation. This happened in the case against Google, where users' private conversations were being recorded without their knowledge, leading to targeted advertising based on information they never intended to share.

How much money will affected users receive?

The

Why didn't Google admit wrongdoing in the settlement?

In most corporate settlements, the defendant doesn't admit guilt as a condition of settling the case. This structure protects companies from having their admitted liability used against them in other lawsuits, regulatory proceedings, or public relations campaigns. By settling without admitting wrongdoing, Google can pay the settlement amount while maintaining a legal position that it didn't violate users' rights. This is standard practice in class action settlements, though it's controversial because it allows companies to pay penalties without accepting responsibility.

Will this settlement change how Google Assistant works?

The settlement doesn't mandate specific technical changes to how Google Assistant operates. Google isn't required to reduce false activation rates, improve wake word detection, or change how it handles voice data. However, the settlement does likely require deletion of audio recordings obtained through false activations and may impose restrictions on how Google uses voice data in the future. The bigger change is that Google is transitioning away from Google Assistant to focus on Gemini, though this shift is driven by business strategy rather than the settlement itself.

How does this compare to Apple's Siri settlement?

Apple faced identical allegations regarding Siri in a class action lawsuit that settled in January 2025 for

What privacy protections actually changed from this settlement?

The settlement primarily results in financial compensation and likely deletion of illegally obtained recordings. It doesn't mandate structural changes to Google's privacy practices or voice assistant technology. Users don't gain new privacy rights or controls beyond what already exists. The settlement is more about compensating past harm than preventing future harm. Real privacy improvements would require either stronger regulatory mandates or changes driven by user demand and market competition, neither of which appears to be happening significantly.

Can I opt out of Google Assistant data collection entirely?

Yes, but it requires multiple steps and involves trade-offs. You can disable "OK Google" voice activation in your Android settings, stop Google from recording your voice commands, limit what data Google collects about your activity, and delete your Google account if you're willing to lose Gmail and other Google services. However, if you use Android, Google will still collect some data about you through the operating system itself. Disabling voice activation prevents the specific voice privacy issues but doesn't eliminate all data collection by Google.

What should I do if I believe my voice was recorded without permission?

First, check your Google Account's Voice & Audio Activity at myaccount.google.com to see what Google has recorded. You can delete individual recordings or bulk delete. File a claim in the settlement if you're eligible. Consider disabling voice activation on devices where you don't need it. Review your overall data collection settings and adjust your privacy preferences. If you discover ongoing privacy violations, you could contact privacy advocacy organizations or consider joining future class actions, though individual litigation against tech companies is rarely economically viable.

Conclusion: Privacy in an Always-Listening World

The $68 million settlement represents a significant legal victory for privacy advocates and affected users. But it's also a reminder of how limited legal remedies are when confronting structural privacy violations embedded in powerful technology platforms.

Google built a profit center on convenience. Voice assistants are genuinely useful. They save time. They improve accessibility for people with disabilities. But that convenience came with a cost: constant surveillance. When the surveillance malfunctioned and captured conversations the company wasn't supposed to hear, Google used that data anyway, for advertising purposes.

The settlement acknowledges this happened and provides nominal compensation. It's justice operating within a system designed to make that justice ineffective. The payout is small. The changes are minimal. The broader business model remains unchanged. Google will continue to collect data, profile users, and sell advertising. The specific practice of using false-activation voice data is presumably addressed, but the fundamental incentive structure remains.

What's important is that this settlement is one of many. Apple paid $95 million for Siri violations. Facebook paid billions for privacy mishandlings. Amazon, Microsoft, and other tech companies face their own privacy scrutinies. The cumulative effect of multiple settlements might eventually create enough pressure to drive real change.

But settlements alone won't solve the problem. Real change requires several forces to align:

Regulation that's strong enough to matter. Fines need to be large enough that they're not simply a cost of doing business. Mandates might be necessary to require companies to implement privacy-protective technologies.

Consumer demand for privacy. As long as users are willing to sacrifice privacy for convenience, companies will continue making that trade-off. Market pressure can only work if users actually switch to alternatives.

Technical innovation. Privacy-protective technologies need to improve. On-device processing, differential privacy, end-to-end encryption, and other approaches need to become standard practice.

Competitive markets. If one company gets massive advantages from unethical data practices, it can outcompete more ethical competitors. Regulators need to level the playing field.

For now, the best you can do is manage your own privacy. Disable voice activation where you don't need it. Review your data collection settings. Delete your voice history. Consider alternatives to Google products. Understand what data you're trading for convenience and make intentional choices rather than accepting defaults.

The settlement is a milestone in the long road toward privacy rights in the digital age. But milestones aren't destinations. There's far more road ahead, and whether we reach a destination where privacy is meaningfully protected remains uncertain.

What's clear is that voice assistants are here to stay. They're incredibly useful and increasingly integrated into every aspect of our digital lives. The challenge is ensuring that their convenience doesn't come at the cost of losing privacy entirely. That requires vigilance, regulation, technical innovation, and consumer pressure all working together.

The Google settlement is a start. But it's just a start.

Key Takeaways

- Google's 20 per affected device

- Voice assistant false activations occurred when the system mistakenly heard wake words in regular conversations, recording and using the audio for targeted advertising without user knowledge

- The settlement provides minimal privacy improvements: no mandatory technical changes to voice detection systems and unclear deletion of data derived from illegally obtained recordings

- Similar privacy violations occurred across the industry, with Apple settling Siri allegations for $95M in January 2025, suggesting systemic problems with voice assistant technology

- Users can protect themselves by disabling voice activation, reviewing voice activity history, limiting Google's data collection, and considering alternative products with stronger privacy protections

Related Articles

- Age Verification & Social Media: TikTok's Privacy Trade-Off [2025]

- TikTok Data Center Outage Sparks Censorship Fears: What Really Happened [2025]

- Technology Powering ICE's Deportation Operations [2025]

- UpScrolled Surges as TikTok Alternative After US Takeover [2025]

- Encrypt Your Windows PC Without Sharing Keys With Microsoft [2025]

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

![Google's $68M Voice Assistant Privacy Settlement [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-s-68m-voice-assistant-privacy-settlement-2025/image-1-1769467098149.jpg)