Introduction: The Legacy of Weird Games Done Right

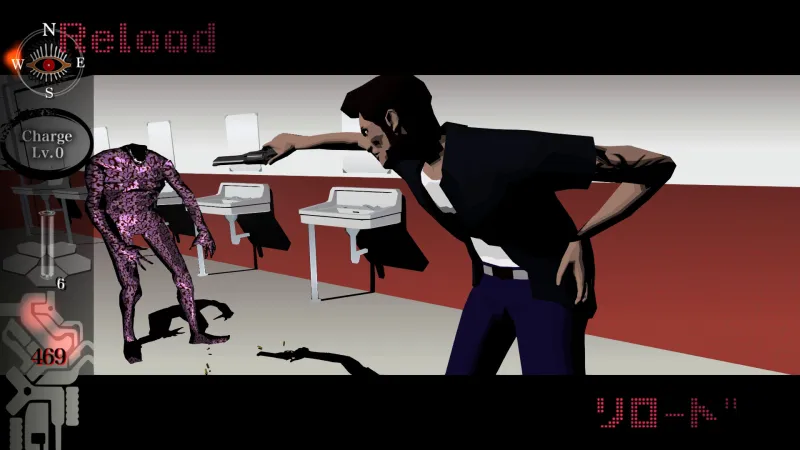

There's something genuinely special about a video game studio that's been operating for nearly three decades without ever once apologizing for being strange. Grasshopper Manufacture, founded in 1998 by Goichi "Suda 51" Suda, has built an entire career on this principle: make what excites you, not what sells. The studio's track record reads like a fever dream of Japanese gaming culture colliding with Western B-movie aesthetics, pop culture references cascading across screens, and protagonists with names like Travis Touchdown who wield lightsaber-like weapons while killing ranked assassins on a bloody leaderboard.

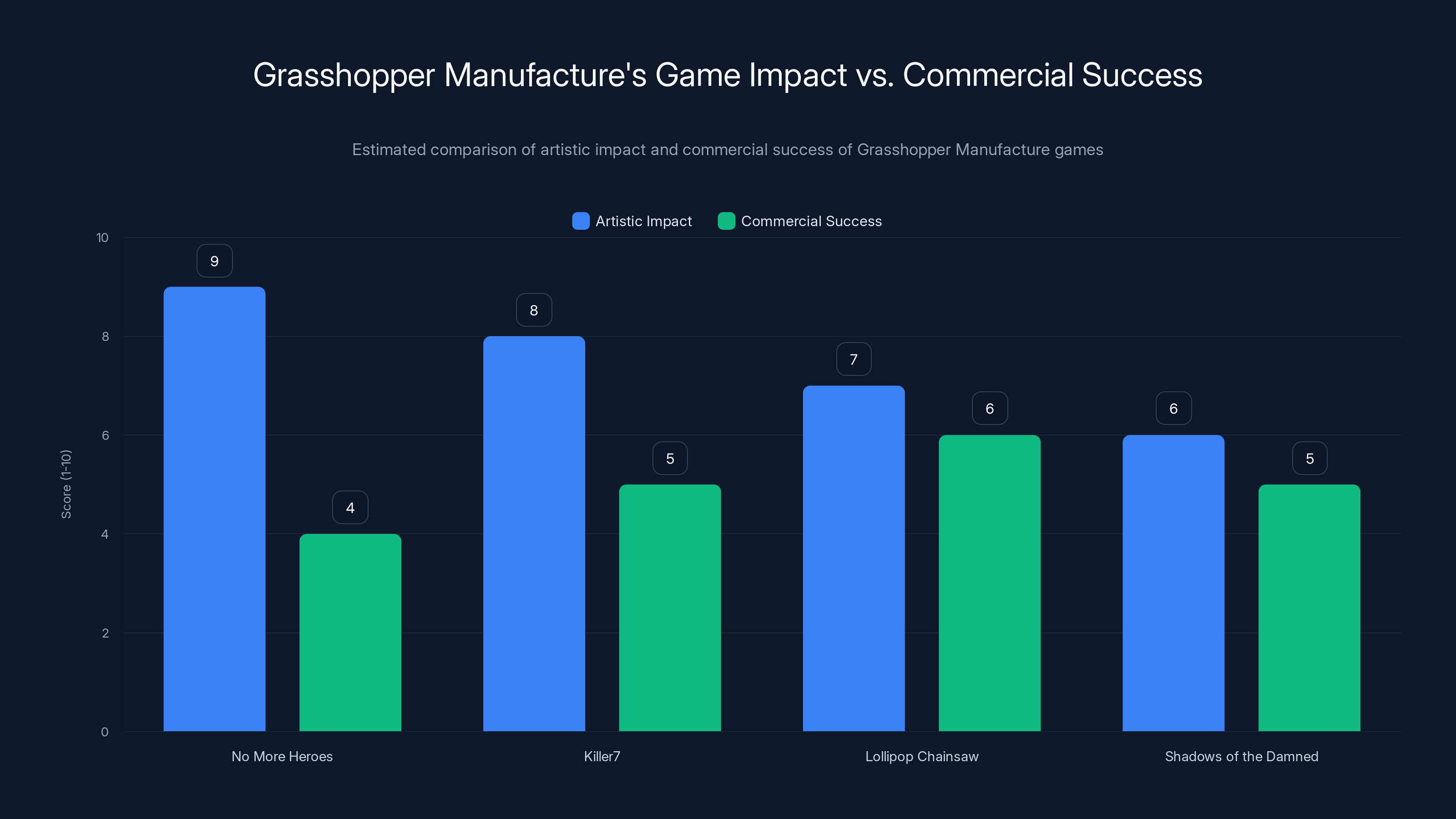

Most game studios chase profitability. They optimize for broad appeal, chase quarterly metrics, and focus group their way toward mediocrity. Grasshopper doesn't. Even Suda 51 himself has admitted that he can't point to a single game in the studio's portfolio that achieved true financial success. Yet here's where it gets interesting: that lack of commercial pressure has freed the studio to do something most developers can't. They've built a recognizable identity so strong that players can identify a Grasshopper game within minutes of booting it up.

This brings us to Romeo is a Dead Man, the studio's latest action-adventure project arriving on PS5, Xbox, and Steam. If you're unfamiliar with Grasshopper's work, this game is a perfect entry point. If you're already a fan, it's proof that the studio hasn't lost a single step. It's bizarre, bloody, self-referential to the point of being almost impenetrable, and absolutely emblematic of everything that makes Grasshopper impossible to classify within traditional gaming categories.

But understanding why this game matters requires stepping back and examining not just what Grasshopper makes, but how they make it and why their approach has created such a devoted following despite never achieving mainstream success. It's a masterclass in creative vision overriding commercial concerns, and Romeo is a Dead Man is the perfect case study for understanding why that matters.

TL; DR

- Grasshopper Manufacture defines itself through artistic risk: Nearly three decades of uncompromising design, pop culture saturation, and visual boldness have created a studio identity that players instantly recognize

- Romeo is a Dead Man embraces surrealism as core design: The game's story intentionally refuses coherence, featuring a girlfriend spread across multiple timelines, a living jacket patch grandfather, and headless entities named after The Smiths lyrics

- Visual style trumps traditional game mechanics: Grasshopper prioritizes aesthetic cohesion and atmosphere over polished combat systems or level design, creating games that feel more like interactive art installations than traditional action games

- Self-reference is a narrative device, not a gimmick: By constantly calling back to previous games and pop culture touchstones, Romeo creates layers of meaning for longtime fans while remaining accessible to newcomers

- Financial success was never the target: The studio's willingness to fail commercially has become its greatest strength, enabling creative freedom that larger studios can't access

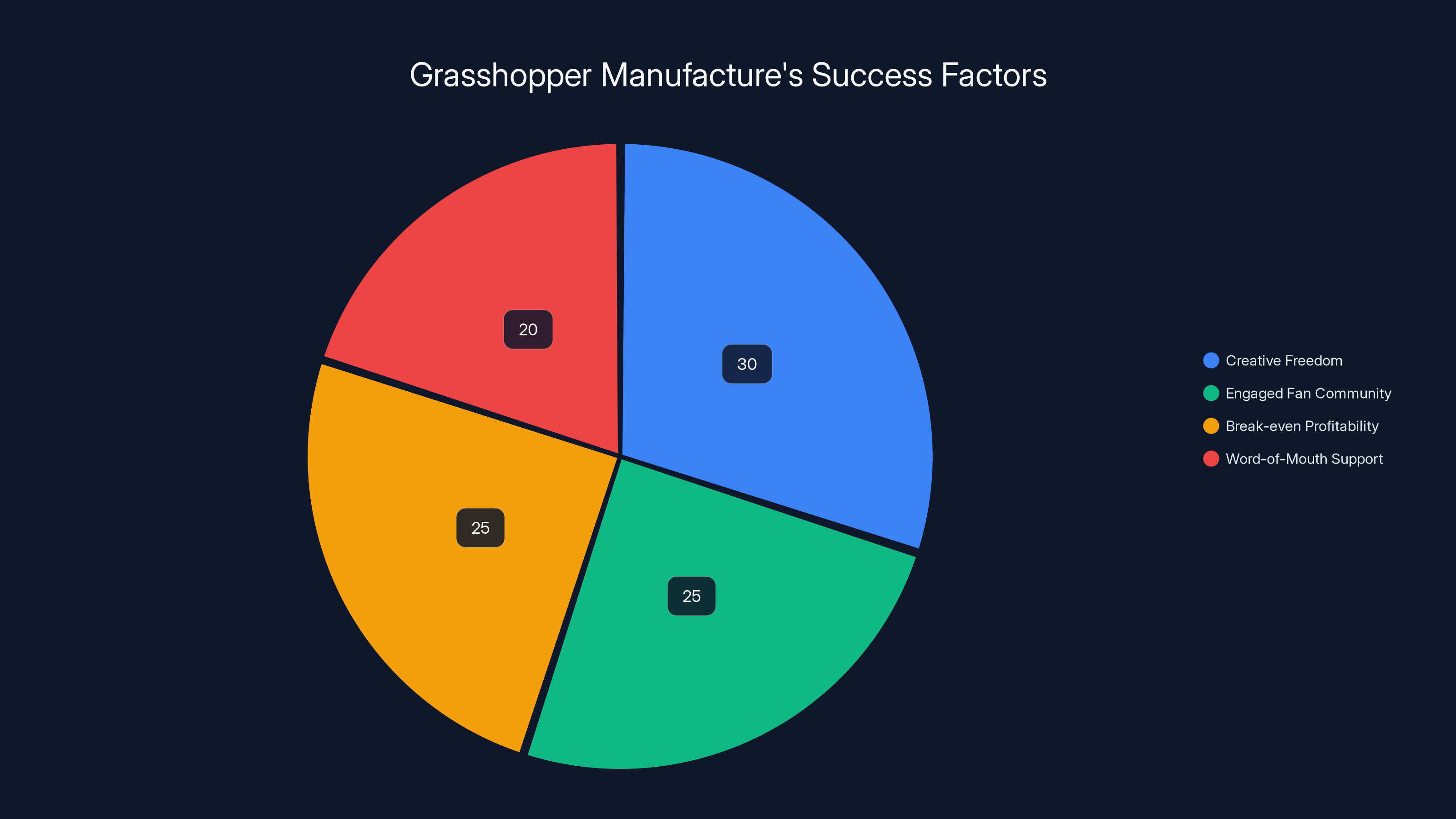

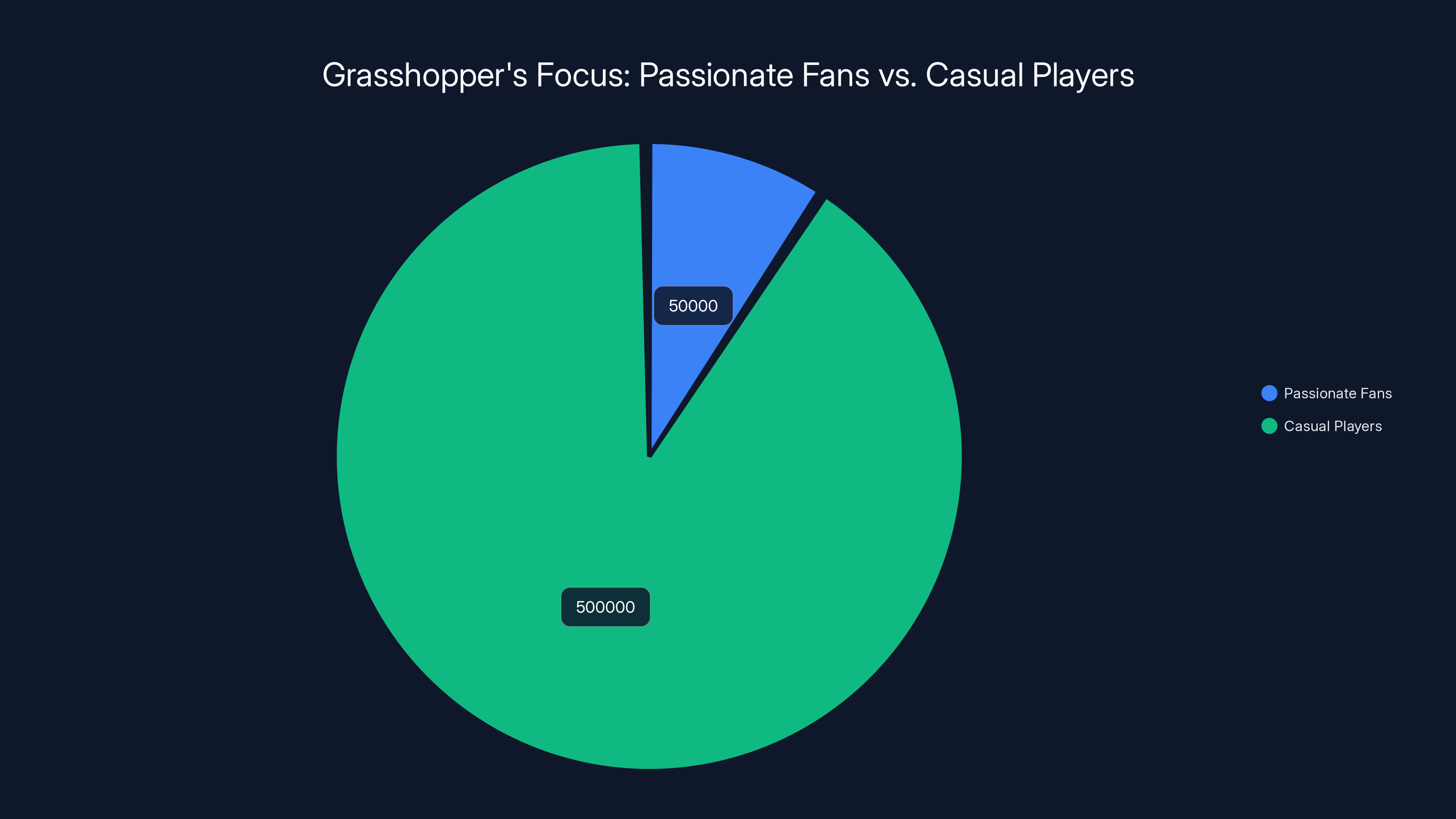

Grasshopper Manufacture's success is driven by creative freedom and a dedicated fan community, allowing for break-even profitability and strong word-of-mouth support. Estimated data.

The Grasshopper Manufacture Phenomenon: How a B-Movie Studio Became Iconic

Building a Studio Identity Through Refusal

When Suda 51 founded Grasshopper Manufacture in 1998, the Japanese video game industry was already dominated by Nintendo's polish, Sega's arcade sensibilities, and Sony's emerging Play Station library. There wasn't room for weird. There wasn't room for unhinged visual design that prioritized style over mechanical perfection. There was certainly no room for a game about a professional assassin with a chainsaw sword who kills otaku obsessives in a ranked battle system.

Yet that's exactly what Grasshopper made with the No More Heroes series, and it worked. Not commercially, necessarily. The game never became a household name. But it created something more valuable: a brand identity so strong that subsequent games automatically inherited its artistic credibility. When you see a Grasshopper announcement, you don't ask "will this be good?" You ask "what kind of weird are we getting this time?"

This phenomenon exists because Suda 51 made a fundamental choice that most creative directors avoid: he decided that commercial success was negotiable, but artistic vision was non-negotiable. This sounds romantic in theory, but it's brutal in practice. It means your games struggle to fund themselves. It means you can't expand your team to the size your ambitions demand. It means compromising your vision regularly just to keep the studio operational.

Yet for Grasshopper, this constraint became a superpower. Freed from the pressure to appeal to casual players or corporate stakeholders, the studio could take risks that major publishers would never greenlight. When you're not chasing quarterly earnings, you can spend three years developing a combat system that's deliberately rough around the edges because you wanted to experiment with something nobody's tried before. You can hire musicians to create original tracks that reference specific genres and eras. You can write dialogue that assumes your audience is steeped in anime culture, Western punk rock, and obscure film references.

The Signature Grasshopper DNA

Every game Grasshopper makes carries a distinctive visual and audio signature. Walk into any one of their projects blind, and within minutes you'll recognize the DNA. It's not that every game looks identical. It's that every game communicates the same underlying philosophy: aesthetics matter more than optimization, personality matters more than polish, and weird is better than safe.

The visual style varies—some games lean toward cel-shading, others embrace pixelated violence, still others explore different rendering approaches. But the sensibility remains constant. Grasshopper games are colorful without being cute. They're violent without being grim-dark. They're earnest without being sincere. The studio understands that most video game narratives take themselves too seriously, and they've developed an ironic, self-aware approach to storytelling that acknowledges the absurdity of their own premises.

Music is another signature element. Rather than hiring orchestral composers to create sweeping epic scores, Grasshopper collaborates with musicians across multiple genres. The studio has worked with indie rock acts, licensed popular songs, and created original tracks that feel like they belong in film soundtracks from specific decades. The music isn't background noise. It's a narrative device that establishes atmosphere and emotional tone.

This combination of visual boldness, audio identity, and narrative weirdness creates something that feels fundamentally different from what other studios produce. A Grasshopper game is immediately recognizable not because it has a particular graphical style, but because it communicates a consistent artistic philosophy.

Why Financial Failure Became Creative Success

Here's the thing that separates Grasshopper from studios that merely experiment: their willingness to accept commercial failure as the price of creative integrity has actually enabled them to create better games than they would have made if profitability was the primary concern.

Consider how modern AAA game development works. Publishers invest hundreds of millions into a game, expecting specific returns. This creates pressure to appeal to the broadest possible audience, to include mechanics that are proven sellers, to avoid anything that might alienate even one demographic segment. Multiplayer functionality gets mandatory inclusions. Loot boxes get engineered into progression systems. Difficulty curves get flattened to accommodate players of all skill levels. Story gets simplified to ensure it plays well to international audiences.

Grasshopper operates in a completely different economic reality. Because they're not chasing blockbuster returns, they can make a game that appeals to nobody except the specific audience that wants weird, visually striking action experiences with narratives that demand active engagement. They can invest time in developing visual effects that most players won't consciously notice but that create an overall feeling of intentionality and care. They can write jokes that land for people who know the references and simply sound confusing to everyone else.

This economic freedom has arguably made Grasshopper a stronger creative studio than they would have been with mainstream success. Imagine if their early games had been blockbuster sellers. Would Suda 51 still be pushing boundaries, or would he have become locked into repeating formulas that already worked? The studio's continued willingness to experiment suggests they never reached that plateau.

Romeo is a Dead Man: The Premise and Its Deliberately Incoherent Genius

The Setup That Refuses Explanation

Romeo is a Dead Man opens with a concept that most game narratives would spend hours explaining and rationalizing. The game's protagonist, Romeo Stargazer, is a sheriff's deputy who dies. Rather than accepting death as final, he gets implanted with a futuristic device that splits him into two states of being: half dead, half alive. He becomes what the game literally calls a "Dead Man."

This isn't explained with technological precision. The game doesn't spend cutscenes showing us schematics of the device or having scientists explain the science behind it. Instead, you get the information and then immediately move forward. Because Romeo is no longer dead, he's recruited by an FBI Space-Time special agent program to search across multiple timelines for his girlfriend, Juliet. Except his girlfriend isn't a person. She's some kind of entity that's actively wreaking havoc across various timeline iterations.

So the basic setup is: find your girlfriend across multiple realities to stop her from destroying things. Which is weird enough already. But then Grasshopper adds the layers that make this genuinely unusual.

Romeo is rescued by his grandfather, who doesn't just help him. He becomes a living jacket patch that Romeo wears throughout the game. Not a magical transformation, not a temporary device. The grandfather is literally an article of clothing. He provides dialogue, appears in cutscenes as an embroidered patch with personality, and generally serves as Romeo's emotional anchor despite existing in a state that would be grotesque if it weren't presented with such matter-of-fact confidence.

The first timeline version of Juliet that Romeo encounters? She's a colossal beheaded naked body that the game names "Everyday is Like Monday." Not a person pretending to be monstrous. Not a monster taking human form. An actual headless body the size of a building, and the name is a direct reference to Morrissey and The Smiths. The game is confident enough in its own absurdity to name a major boss after a depression-adjacent indie rock song.

Self-Reference as Narrative Architecture

While the premise itself is surreal, what separates Romeo is a Dead Man from simply being weird-for-weirdness's sake is how intentionally self-referential the game becomes. Romeo doesn't just exist in a vacuum of Grasshopper's making. He exists in conversation with the studio's entire catalog, winking at longtime fans while remaining accessible to newcomers who have no idea what Grasshopper has done before.

Romeo spouts phrases like "fuckhead," which is recognizable to anyone who played No More Heroes as one of Travis Touchdown's signature vocabulary choices. The protagonist explicitly invokes "kill the past," which connects directly to Grasshopper's Killer 7 and its obsessions with history, violence, and transformation. Pop culture references cascade through the dialogue: Back to the Future, Star Wars, Twin Peaks, The Clash, Mobile Suit Gundam, and countless others fold into the narrative.

But the self-reference isn't just Easter eggs for fans to spot. It's structural to how the game communicates meaning. By constantly calling back to pop culture touchstones and previous Grasshopper games, Romeo creates layers of interpretation. Someone playing for the first time will experience a weird action game with pop culture callbacks. Someone who's played multiple Grasshopper games will recognize how Romeo comments on and reframes previous narratives.

This is sophisticated narrative design. It's not showing off. It's creating a game that rewards engagement across multiple levels of interpretation. The game trusts its audience to be smart enough to pick up on references without spelling them out, and it doesn't condescend to players who miss them entirely.

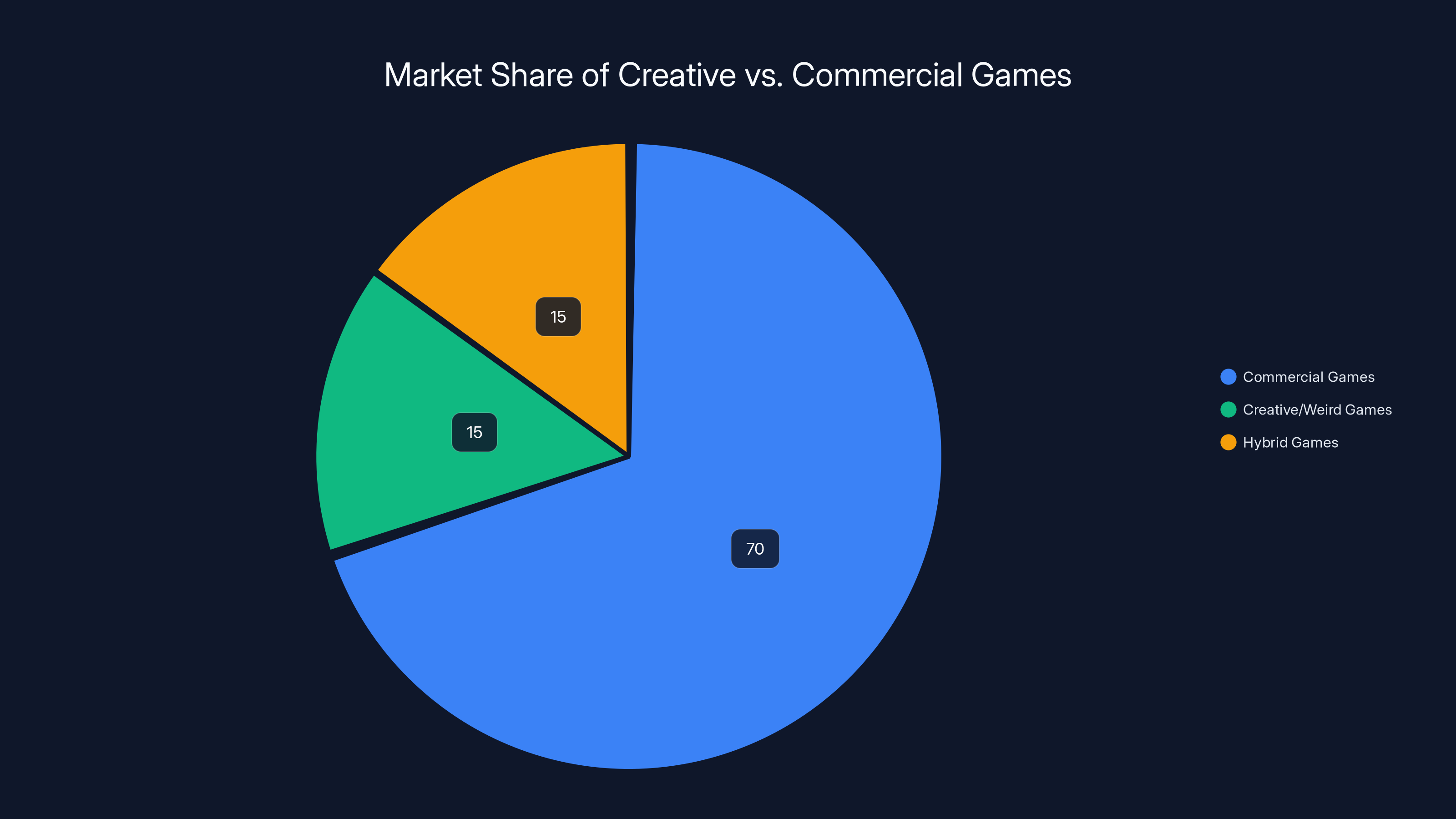

Estimated data shows that commercial games dominate the market, but creative games like those from Grasshopper still hold a significant niche, highlighting their importance in preserving artistic expression.

Visual Design Philosophy: Aesthetics Over Mechanical Perfection

Why Combat Takes a Backseat to Style

If you approach Romeo is a Dead Man expecting tight, precision-based combat design optimized for competitive play, you're going to be disappointed. The fighting mechanics are serviceable. They work. They're responsive enough that you can execute intended actions. But they're clearly not the priority.

What's the priority is everything surrounding the combat. The visual feedback when hits connect, the grotesque enemy designs, the environmental destruction, the way the screen reacts to your actions. The combat is a vehicle for expressing the game's aesthetic vision rather than an end in itself.

This choice separates Grasshopper from studios obsessed with mechanical depth. Most action games iterate endlessly on combat systems. They playtesting mechanics for months. They analyze how skilled players approach encounters and build counters into enemy behavior. They optimize for both casual accessibility and competitive depth.

Grasshopper takes a different approach. The studio assumes you're playing for the experience, not for the mechanics. You're there for the story, the visuals, the overall feeling of inhabiting this world. The combat serves that goal. It's not unresponsive, and it's not broken, but it's deliberately not the main attraction.

This philosophy actually works better for the kinds of stories Grasshopper wants to tell. If the combat were hyper-optimized and perfectly balanced, it would pull focus from narrative and atmosphere. You'd be thinking about optimal damage strategies and frame-perfect inputs rather than absorbing the grotesque genius of fighting a building-sized headless body.

Environmental Grotesquerie as Design Language

Where Romeo is a Dead Man's visual design truly shines is in its commitment to grotesque environmental design. The game isn't interested in being beautiful in conventional ways. It's interested in being memorable, striking, and visually unusual.

You spend much of the game fighting zombies, but these aren't conventional undead enemies. They're bizarre, twisted, often anatomically impossible creatures that look like they crawled out of someone's fever dream. The game leans into body horror not for shock value but as a design philosophy. Every enemy is a visual statement about how strange and unsettling the game's world is.

The zombie farming mechanic exemplifies this approach. Rather than simply appearing throughout levels, zombies can be harvested from a farm located in your spaceship. You can cultivate zombie abilities in combat, essentially farming specific types of undead for their specific tactical advantages. It's grotesque, but it's also strategic. It's also inherently Grasshopper: taking something horrifying and treating it as matter-of-fact enough to build a farming system around.

Environments reflect this same commitment to visual boldness. Spaces feel designed to communicate atmosphere rather than optimal level design. Corridors twist in unusual ways. Platforms don't always connect intuitively. There's a deliberate disorientation to how environments are structured, which reinforces the narrative themes of reality becoming unstable across timelines.

The Zombie Economy: Farming Horror for Strategic Advantage

Mechanizing the Grotesque

One of the genuinely inventive mechanics in Romeo is a Dead Man is the zombie farming system. This isn't just flavor. This is a core strategic layer that forces you to think about combat encounters differently. Rather than simply fighting zombies that appear in levels, you maintain a farm in your spaceship where you can cultivate different zombie types and harvest their abilities for use in actual combat.

This mechanic is characteristically Grasshopper because it treats something horrifying with absolute earnestness. There's no joke. There's no winking at the camera. The game presents zombie farming as a normal, functional part of its world. You manage your farm. You grow specific types of zombies. You harvest their abilities. It's efficient and logical within the game's own internal logic.

What makes this brilliant is how it reframes player approach to combat. Instead of simply fighting enemies you encounter, you're thinking about which zombie types you want to cultivate and what tactical advantages their abilities provide. A zombie that explodes might be useful for clearing groups. A zombie that freezes enemies might be useful for crowd control. By letting you farm specific types, the game lets you build strategic advantage through preparation rather than just mechanical skill.

It also reinforces one of the game's core themes: the normalization of the grotesque. In Romeo's world, farming the undead isn't unusual or disturbing. It's just how things work. By implementing this as a standard game system, the writing and design work in concert to establish how fundamentally weird this universe is.

Strategic Depth Through Asymmetric Resources

The zombie farming system creates an interesting resource management layer that most action games avoid. You're not managing ammunition or health potions. You're managing which zombie types you've cultivated and which abilities you have available. This creates a different kind of strategic thinking.

Some encounters might favor specific zombie abilities. Some might require different tactical approaches depending on what you've farmed. This encourages you to replay sections or approach encounters differently based on your preparation, which most action games avoid by making combat mechanics themselves handle variety.

It's a design choice that acknowledges something important: not every player approaches combat the same way. Some prioritize mechanical skill. Some prefer preparation and strategic planning. By letting you literally farm your combat toolkit, Romeo accommodates different playstyles while maintaining thematic coherence.

Narrative Layers: Pop Culture, Self-Reference, and Intentional Incoherence

The Architecture of References

Romeo is a Dead Man is built on references the way some games are built on procedural generation. References aren't sprinkled in. They're foundational. The game assumes its audience is steeped in pop culture across multiple media—films, television, music, anime, manga, comic books. It's not trying to appeal to everyone. It's specifically designed for people who recognize when something references Twin Peaks or Mobile Suit Gundam.

But here's the sophisticated part: the references aren't random. They're contextual. The game pulls from specific genres and eras for specific narrative purposes. The grandfather rescuing Romeo from the future calls back to Back to the Future, which carries implications about time travel, family, and unexpected salvation. The space-time FBI agent concept borrows from science fiction conventions while subverting them immediately.

For players steeped in Grasshopper's work, there are additional layers. The DNA of No More Heroes is visible. Killer 7's obsession with violence and transformation echoes through the narrative. The studio's previous experiments with surreal storytelling create context for understanding how Romeo fits into their broader creative trajectory.

Narrative as Experience Rather Than Information

One of the most interesting things about Grasshopper's approach to storytelling is how little they care about clear exposition. Most games spend significant time explaining their worlds. Cutscenes establish rules. Characters explain mechanics and story details. The game holds your hand through understanding.

Grasshopper doesn't. Information is scattered throughout. Some details are explained clearly. Some are hinted at through environmental storytelling. Some are left deliberately ambiguous. The game trusts you to piece together understanding through multiple exposure and inference rather than explicit explanation.

This makes the narrative experience more active. You're not passively receiving a story. You're constructing one through engagement with scattered information and visual cues. It's a more demanding approach than traditional game narrative, which is probably why Grasshopper games attract a specific type of player.

Romeo is a Dead Man leans heavily into this approach. The premise is deliberately disorienting. The plot doesn't follow conventional story beats. Characters appear and disappear without clear narrative justification. But within this apparent chaos, there's thematic coherence. Everything relates to ideas about identity, transformation, and the impossibility of maintaining singular selves across multiple timelines.

Grasshopper Manufacture games are known for high artistic impact but moderate commercial success. Estimated data based on industry perception.

The Grasshopper Aesthetic: When Style Becomes Substance

Visual Cohesion as Meaning-Making

One criticism sometimes leveled at Grasshopper games is that they prioritize visual style over mechanical substance. This criticism misses something fundamental: in Grasshopper's hands, style is substance. The visual design communicates meaning that the mechanics might not.

Consider how Romeo's fragmented appearance across timelines is communicated. Rather than spending dialogue explaining how his existence is fractured, the game shows this through visual inconsistency. Different timeline versions of Romeo look slightly different. Glitches in the visual presentation suggest reality instability. The stylistic choices reinforce the thematic core.

Similarly, the design of enemies and environments communicates the surreal horror of the game's world more effectively than exposition could. An enemy design that's anatomically impossible and disturbing visually communicates weirdness faster than dialogue explaining how weird things are. The game trusts visual language to do narrative work.

This is sophisticated design. Most games separate visual style from narrative and mechanical design. Grasshopper integrates them. The way something looks isn't decorative. It's communicative. It's functional. It's doing specific narrative work that supports the overall experience.

Audio Design as Emotional Architecture

Grasshopper has always understood that audio design is underutilized in video games. Most games use music to enhance emotions that visuals and mechanics are already communicating. Grasshopper uses music to establish genre and emotional context, sometimes even contradicting what's happening mechanically.

A cutscene that should feel dark and foreboding might play against a jaunty, almost cheerful rock track. This juxtaposition creates interesting emotional complexity. You're not being told what to feel. You're navigating competing emotional signals, which is more interesting than simple alignment.

Romeo is a Dead Man likely continues this tradition. The audio design probably feels incongruous with the visual violence and grotesquerie. That incongruity is intentional. It's forcing a more active emotional engagement than alignment would provide.

Grasshopper's Creative Process: How Weird Gets Made

Starting with Concept, Not Mechanics

Most game development processes start with either mechanics or technology. Teams figure out what they want the game to do mechanically, then build narrative and aesthetics around those mechanics. Or they identify a technical achievement they want to pursue, then build a game that showcases it.

Grasshopper appears to work backward. They start with a concept—what if someone was half dead? What if your girlfriend was an entity destroying timelines? What if your grandfather was a jacket? These conceptual premises are so weird that the mechanics and aesthetics have to serve them rather than the reverse.

This approach is risky. It can result in games where mechanics feel tacked-on or where the overall experience feels disjointed. For Grasshopper, it usually results in something that feels intentional and cohesive, because the entire development process is oriented toward making the weird concept work.

Embracing Rough Edges as Authenticity

Grasshopper games frequently have rough edges. Combat might not be perfectly balanced. Level design might prioritize atmosphere over optimal flow. Some mechanics might feel underdeveloped. These aren't typically bugs or oversights. They're choices. They're part of how Grasshopper maintains authenticity to its vision.

A perfectly polished Grasshopper game would actually feel wrong. Part of what makes Grasshopper special is that the games feel like genuine expressions of weird creative vision rather than corporate products refined through countless testing iterations. The rough edges are proof of concept. They're evidence that this was made by people pursuing something specific rather than trying to appeal to everyone.

The Impact on Contemporary Game Design: Why Grasshopper Matters Beyond Its Own Games

Proof That Weird Can Be Sustainable

In an industry increasingly consolidated around profit metrics and risk minimization, Grasshopper's existence matters. The studio proves that there's space for uncompromising weirdness. It proves that you can maintain creative vision across multiple decades and multiple projects without chasing mainstream success. It proves that audience exists for bold, strange, visually striking games that demand active engagement.

This matters because it suggests possibilities to smaller developers. If Grasshopper can survive nearly three decades making weird games that Suda 51 admits aren't financially successful, maybe there's room for other studios to do similarly bold work. Maybe commercial success isn't the only measure of a game's value. Maybe creative achievement matters.

Grasshopper's success (defined not commercially but culturally) has created space for games like Killer 7, Killer is Dead, Let It Die, and Travis Strikes Again to exist. None of these would fit within mainstream publisher frameworks. But because Grasshopper proved that niche audiences will support weird work, other developers have felt emboldened to pursue similarly unusual visions.

Influencing Design Philosophy Across the Industry

You can see Grasshopper's influence in games that have nothing directly to do with their work. Developers have learned from Grasshopper that aesthetics can carry narrative meaning. That visual style can be as important as mechanical innovation. That player audiences are sophisticated enough to engage with difficult, demanding narratives that don't explain themselves clearly.

When a small indie game makes strange visual choices or expects players to piece together narrative from fragments, there's often an implied genealogy connecting back to Grasshopper's work. Not direct influence necessarily, but shared understanding that games don't have to appeal to everyone and that weird can work.

Grasshopper prioritizes breaking even, fan engagement, and creative risk over high polish, allowing them to maintain sustainability and creative freedom. (Estimated data)

The Commercial Reality: Why Grasshopper Makes What Nobody Asked For

Breaking Even Instead of Blockbusting

Suda 51 has been remarkably candid about the commercial struggles Grasshopper faces. He's admitted that he can't identify any single game in the studio's portfolio that was financially successful in the way major publishers define success. Games don't need to sell millions of copies to justify development costs. Games just need to break even and maintain a fan base.

This is the economic reality that enables Grasshopper's weirdness. They're not chasing blockbuster returns. They're chasing sustainability. If a game breaks even and creates an engaged audience for the next project, the studio survives. This allows for the kind of creative risk-taking that would be unconscionable for a major publisher managing hundreds of millions in production budget.

It also means the studio operates with constant financial pressure that major publishers don't face. Grasshopper can't afford development hell. They can't fund years of preproduction experimenting with ideas that don't work out. They have to move forward. They have to complete projects. Sometimes that means compromises, sometimes that means rough edges, sometimes that means choosing between polish and scope.

Rather than apologizing for these constraints, Grasshopper has integrated them into its creative process. The rough edges become part of the aesthetic. The constraints become part of the design philosophy. The studio makes the best weird game it can with available resources rather than trying to make the most polished version of a generic game.

Why Suda 51 Continues Despite Commercial Struggles

At this point in his career, Suda 51 could probably transition to something more commercially stable if he wanted. He could take a job as creative director at a major publisher. He could design games for corporate committees. He could pursue projects with guaranteed commercial success.

That he continues to run Grasshopper and make weird games suggests something about his creative philosophy that goes beyond rational economic calculation. Suda 51 appears to genuinely believe in the value of what Grasshopper makes, independent of commercial success. He values creative expression in its own right. He values the opportunity to work with collaborators who share this vision. He values the freedom to pursue ideas that nobody else would greenlight.

This is rare in an industry shaped entirely by financial incentives. It's admirable. It's also probably exhausting. But it's exactly why Grasshopper maintains such a strong creative identity. Suda 51 isn't making games to achieve something else. He's making games as an end in itself.

Romeo is a Dead Man as Culmination and Continuation

How This Game Represents Grasshopper's Full Artistic Vocabulary

Romeo is a Dead Man doesn't feel like a break from Grasshopper's previous work. It feels like an accumulation. All the visual language, narrative techniques, design philosophy, and aesthetic choices that the studio has developed over three decades appear fully formed in this single project. It's a showcase of everything Grasshopper has learned about how to express weird ideas through video games.

The surreal premise. The self-referential narrative. The grotesque visual design. The commitment to atmosphere over mechanical perfection. The integration of music as narrative tool. The willingness to leave things unexplained. The trust in the audience's intelligence and engagement. All of this flows together into Romeo.

What's remarkable is how the game balances accessibility with demanding audience sophistication. Someone playing Romeo without any prior Grasshopper experience can enjoy it as a weird action game with great visual design and an absurd premise. Someone familiar with Grasshopper's entire catalog will find layers of meaning and reference woven throughout. The game works on both levels simultaneously.

This is evidence of genuine creative maturity. Young artists make work that's either deliberately obscure or desperately accessible. Mature artists make work that functions on multiple levels. Romeo is a Dead Man operates this way.

What Romeo Suggests About Grasshopper's Future

If Romeo is a Dead Man is truly the culmination of Grasshopper's accumulated artistic vocabulary, it raises interesting questions about where the studio goes next. Does Grasshopper continue refining what they do? Do they experiment with new directions? Do they try something completely different?

Based on the studio's history, the answer is probably both. Grasshopper has never stayed static. But Romeo suggests the studio is also confident enough in its own identity to fully commit to everything it's developed over decades. The game is uncompromising. It doesn't hedge. It doesn't try to appeal beyond the specific audience that wants weird, visually striking, narratively complex action experiences.

That confidence suggests Grasshopper will continue making equally bold projects. The studio has proven it can sustain itself doing what it does. There's no reason to compromise now. If anything, Romeo is probably proof that Grasshopper's artistic approach is more viable than ever, even in an industry increasingly consolidated around commercial predictability.

Comparing to Industry Contemporaries: Why Grasshopper Stands Apart

Against AAA Risk-Aversion

When you examine what major publishers greenlight, Grasshopper's work stands out through sheer contrast. AAA games increasingly follow proven formulas. Open world structure. Progression mechanics designed to extend playtime. Narrative that appeals to broad demographics. Accessibility options that allow nearly anyone to experience the content. These are responsible design choices. They're also limiting.

Grasshopper doesn't do any of this. Romeo is a Dead Man isn't an open world. It doesn't have progression mechanics designed to extend engagement artificially. It's not trying to appeal to everyone. It's deliberately niche. And this specificity is actually its strength. By focusing entirely on a specific vision and specific audience, the game achieves coherence that most AAA titles can't match.

You notice this immediately when switching between AAA games and Grasshopper's work. AAA games feel like they're compromising constantly. Trying to appeal to different player types. Supporting different playstyles. Including mechanics that serve specific demographics. There's nothing wrong with this, but it results in a kind of diffuse identity.

Grasshopper games have singular identity. Everything serves a specific vision. No hedging. No compromise. No attempt to appeal beyond the intended audience. This makes the games feel more honest in some way. More authentic. More like genuine creative expression rather than corporate products.

Against Indie Preciousness

Grasshopper is also distinct from indie games that prioritize artistic ambition above all else. Some indie projects are so committed to experimental design that they become inaccessible or actively difficult to engage with. Grasshopper doesn't do this. Their games are weird, yes. But they're playable. They're engaging. They don't mistake obscurity for depth.

Romeo is a Dead Man is weird, but it's also fun. The grotesque design is also visually striking. The difficult narrative is also rewarding to parse. The rough combat is also satisfying to engage with. Grasshopper has learned how to be experimental and accessible simultaneously, which is a genuine skill.

This separates Grasshopper from purely avant-garde game design. The studio isn't making games that only theorists and critics will appreciate. They're making games that regular players find genuinely engaging, even if those players might not have sought out Grasshopper's work initially.

Grasshopper prioritizes a smaller, passionate fanbase of 50,000 over a larger, casual audience of 500,000. Estimated data highlights their focus on community engagement over market penetration.

Thematic Analysis: What Romeo is Actually About

Identity and Fragmentation

Beneath the surrealism and grotesquerie, Romeo is a Dead Man appears to explore ideas about identity and how it fragments across contexts. The premise itself—Romeo existing as half-dead, needing to find his girlfriend across multiple timeline versions—is fundamentally about identity being impossible to maintain singularly.

Romeo is different in each timeline. His girlfriend is different. The world itself is different. Yet he remains Romeo. There's continuity of consciousness even as everything around him shifts. This is a genuinely sophisticated exploration of how identity persists despite environmental and circumstantial change.

The living jacket patch grandfather adds another layer. Here's a family member who's lost physical form but maintained personality and emotional connection. He's still the grandfather. He's still important to Romeo. But he exists in a fundamentally transformed state. It's grotesque, but it's also moving. It's exploring what remains when form changes.

The Normalization of the Grotesque

Romeo doesn't treat its grotesquerie as special or shocking. The game presents headless entities, zombie farming, and dead men as normal parts of the world. This normalization is the point. The game is exploring what happens when you accept the grotesque as baseline reality. How do people function? How do they form relationships? How do they maintain meaning and purpose?

By refusing to treat the weird as weird, Romeo suggests that grotesquerie is just difference. It's another way of being. This might be the game's most sophisticated theme. Not "look at this weird thing," but "this is just how things are here."

Love Across Impossible Distance

At its core, Romeo is a story about trying to find and save someone you love despite impossible obstacles. The specific obstacles are surreal, but the emotional core is genuine. Romeo travels across timelines for Juliet. He farms zombies and fights grotesque entities. Why? Because he loves her.

The absurdity of the premise doesn't diminish the genuine emotion. If anything, it emphasizes it. Despite everything being weird and difficult and grotesque, Romeo continues trying because love persists through all circumstances. That's actually kind of beautiful.

The Role of Grasshopper in Gaming Culture

As Cultural Artifact

Grasshopper's games are becoming increasingly recognized as important cultural artifacts independent of their commercial success. When we examine how games express ideas and communicate meaning, Grasshopper's work stands out. The studio has developed a sophisticated visual language. It's pioneered approaches to narrative that other developers have adopted. It's proven that commercial success isn't necessary for cultural importance.

Romeo is a Dead Man will probably be studied and discussed by game scholars precisely because it represents a mature artist fully committing to a distinctive vision. It's not compromising. It's not hedging. It's not trying to appeal beyond its intended audience. It's just a genuine expression of specific creative vision.

As Proof of Concept

For younger developers and students considering game design careers, Grasshopper offers an alternative model. You don't have to work within major publisher frameworks. You don't have to chase blockbuster success. You can build a sustainable career making weird, specific, visually distinctive work. You can maintain creative control. You can work with collaborators who share your vision.

It's not easy. Suda 51 has been transparent about the financial struggles. But it's possible. Grasshopper proves it's possible. That's important.

What Romeo Teaches About Game Design Philosophy

Commitment Over Compromise

Romeo is a Dead Man's greatest strength is its commitment to its own vision. The game doesn't compromise. It doesn't try to be something it's not. It doesn't adjust its weirdness for broader appeal. Every design choice serves the core vision. Every aesthetic decision reinforces the experience the game is trying to create.

This is probably the most important lesson Grasshopper offers to other developers. Commitment to vision actually works better than trying to appeal to everyone. Players respond to games that know what they are. Games that hedge feel hollow. Games that commit feel genuine.

Aesthetics as Meaning

Romeo demonstrates that visual style isn't decoration. It's communicative. It's functional. The way something looks can carry narrative meaning. The way something feels can reinforce thematic content. Grasshopper has integrated aesthetic and mechanical design into a unified whole where everything serves the experience.

Most developers treat aesthetics as something applied after mechanics are developed. Grasshopper integrates them from the start. The game looks weird because it's supposed to feel weird. The combat is rough because it's supposed to emphasize style over precision. The narrative is disjointed because it's supposed to reflect fragmented identity.

Trust in Audience Intelligence

Grasshopper doesn't explain things that don't need explanation. It doesn't hold hands. It trusts players to be smart enough to piece things together. This trust is itself a form of respect. It's acknowledging that players are sophisticated enough to handle demanding experiences.

Most games underestimate their audiences. Grasshopper overestimates in the best way possible. It assumes players are steeped in pop culture. It assumes they can handle narrative ambiguity. It assumes they'll actively engage with references rather than passively consuming content. And players respond to this respect with engagement and loyalty.

Grasshopper Manufacture games are known for their unique style and cult following, often receiving high ratings from fans despite not achieving mainstream success. (Estimated data)

The Future of Weird Games in an Industry Chasing Stability

Market Forces Pushing Toward Safety

The gaming industry is consolidating. Large publishers are acquiring smaller studios. Production budgets for AAA games are increasing. This creates pressure toward commercial predictability. It's harder to greenlight weird games when production budgets exceed $100 million. Publishers need return on investment. They need broad appeal. They need proven formulas.

This squeezes out space for experimentation. It squeezes out space for games made primarily for artistic expression. It squeezes out studios like Grasshopper that willingly accept commercial underperformance in exchange for creative freedom.

Why That Makes Grasshopper's Work More Important

Given these market forces, Grasshopper's continued commitment to weird, visually distinctive games becomes increasingly important. The studio is literally preserving space for creative expression that the market is pressuring toward extinction. Every Grasshopper game is a statement that profitability isn't the only measure of success.

Romeo is a Dead Man is therefore more than just a game. It's resistance. It's proof that there's still room for uncompromising weirdness in modern gaming. It's an argument that creative integrity matters. It's evidence that audiences will support genuine artistic vision despite industry pressure toward commercial safety.

How Grasshopper Maintains Fan Loyalty Despite Commercial Struggles

Community as Primary Metric

Grasshopper doesn't have millions of players. But the players it does have are deeply engaged. This is deliberate. The studio has optimized for community loyalty rather than market penetration. Better to have 50,000 passionate fans than 500,000 casual players. The passionate fans support future projects. They talk about the games. They create secondary creative works. They become advocates.

This is the economic model that enables Grasshopper's weirdness. The studio has shifted success metrics from sales volume to community engagement. A game can be commercially underperforming and still succeed by these metrics if the engaged audience is large enough and passionate enough.

Recognizing and Rewarding Loyalty

Grasshopper also does something most studios underestimate: it acknowledges and respects its core audience. Suda 51 is active in communities. The studio engages with fans. References to previous games are included specifically for longtime followers. The games feel like they're made by people who understand and appreciate their audience.

This recognition creates loyalty. Fans feel seen. They feel understood. They feel like the creator is making games specifically for them. This emotional connection transcends commercial metrics. It's why people continue supporting Grasshopper despite financial struggles.

Technical Execution: How Grasshopper Makes Beautiful Weird Games

Visual Rendering and Art Direction

Romeo is a Dead Man's visual design probably leverages modern rendering technology in service of strange aesthetics. Rather than using technical capabilities to create photorealism or impressive scale, Grasshopper uses them to realize visually distinctive worldmaking.

This is a sophisticated use of technology. Most developers use technical advancement to pursue visual realism. Grasshopper uses technical advancement to make weirder things possible. The zombie designs. The grotesque environmental details. The visual glitches suggesting reality instability. All of this requires technical competence, but it's in service of weird aesthetics rather than traditional beauty.

Optimization for Consistency

Grasshopper games generally run well technically. This might not be obvious because the games don't pursue visual cutting-edge status. But the technical optimization allows Grasshopper to be ambitious with visual design. They can fill screens with grotesque detail. They can create visually complex environments. They can support the audio-visual experience they're trying to create.

It's a different kind of technical achievement than raw graphics capability. It's optimization in service of specific vision. It's competence applied toward making weird work consistently.

The Role of Original Soundtracks in Grasshopper's Identity

Music as Genre Establishment

Grasshopper games use music to establish emotional context and genre. Rather than composing original orchestral scores, the studio collaborates with musicians across various genres. Indie rock acts, punk references, specific era callbacks. The music is as carefully chosen as the visual design.

Romeo is a Dead Man probably continues this tradition. The soundtrack probably features music that contrasts with the grotesque visuals in interesting ways. Music that establishes specific emotional tones that reinforce narrative themes.

Audio Design Beyond Soundtrack

Beyond the soundtrack, audio design itself is probably a signature Grasshopper element. Sound effects probably communicate meaning beyond simple feedback. Ambient audio probably contributes to atmosphere. Dialogue probably sounds distinctive and chosen for tonal effect rather than purely functional communication.

All of this together creates an audio landscape that reinforces the game's overall identity. You don't just see Grasshopper's weirdness. You hear it.

Criticism and Limitations: Being Honest About What Grasshopper Isn't

Mechanical Innovation Isn't the Goal

If you're looking for groundbreaking mechanical innovation, Grasshopper isn't it. The studio isn't pushing combat systems forward. It's not pioneering new gameplay mechanics. It's using established mechanics to serve aesthetic vision. This is a limitation if you prioritize mechanical depth. It's irrelevant if you prioritize cohesive experience.

Accessibility Questions

Grasshopper games can be demanding. Demanding narratively. Demanding visually. Demanding in terms of required cultural knowledge. If accessibility is your primary concern, Grasshopper's games are less inclusive than mainstream options. The studio doesn't apologize for this. It builds for specific audience rather than broadest possible audience.

Rough Production Values

Grasshopper games sometimes feel rough. Dialogue can be awkwardly paced. Level design can feel unpolished. This is sometimes limitation, sometimes choice. The roughness reinforces authenticity for some players. For others, it's a barrier to engagement. Both perspectives are valid.

FAQ

What is Grasshopper Manufacture and why does it matter?

Grasshopper Manufacture is a Japanese video game studio founded in 1998 by Goichi "Suda 51" Suda. It matters because it proves that uncompromising artistic vision can sustain a game studio for nearly three decades without mainstream commercial success. The studio has carved out a distinctive identity making visually striking, narratively complex, deliberately weird games that prioritize aesthetic coherence over mechanical polish. In an industry increasingly consolidated around financial predictability, Grasshopper's continued existence and commitment to creative risk-taking is culturally significant.

How does Romeo is a Dead Man represent Grasshopper's artistic philosophy?

Romeo is a Dead Man embodies Grasshopper's philosophy through its commitment to surreal premise, grotesque visual design, self-referential narrative, and willingness to deprioritize mechanical precision in favor of aesthetic vision. The game doesn't explain its weird concepts. It doesn't compromise toward broader appeal. It doesn't apologize for being visually grotesque or narratively demanding. Every design choice serves the core vision of creating a cohesive weird experience. This singular commitment is exactly what defines Grasshopper's approach.

Why does Grasshopper succeed commercially despite never having blockbuster success?

Grasshopper succeeds by redefining what commercial success means. Rather than chasing blockbuster sales, the studio aims for break-even profitability with an engaged fan community. This allows reinvestment in future projects. The studio's willingness to accept lower revenue in exchange for creative freedom actually enables them to make better games than they would if pursuing mass market appeal. Additionally, the passionate fan base creates loyalty that transcends typical commercial metrics, supporting future projects through word-of-mouth and community engagement.

What is the zombie farming mechanic and why is it significant?

The zombie farming mechanic allows players to cultivate different zombie types in a farm located within their spaceship and harvest their abilities for use in combat. It's significant because it demonstrates how Grasshopper integrates thematic content with mechanical design. Rather than treating zombie combat as generic enemy engagement, the farming system makes zombie-killing strategic and reinforces the game's grotesque aesthetic. It's the kind of specific, weird design choice that separates Grasshopper from mainstream developers.

How do Grasshopper games handle narrative and storytelling differently than mainstream games?

Grasshopper games don't explain themselves clearly. They scatter information throughout the experience and trust players to piece things together. They reference pop culture extensively without spelling out references. They leave narrative elements deliberately ambiguous. They assume sophisticated audience engagement. This demands more from players than mainstream games do, but it also creates more active, engaged experience. Players aren't passively receiving story. They're constructing it through interpretation.

What makes the visual design of Romeo is a Dead Man distinctive?

The visual design prioritizes grotesque weirdness over conventional beauty. Environments are deliberately disorienting. Enemy designs are anatomically impossible and disturbing. Color and visual effects are chosen for emotional impact rather than realism. The overall visual language communicates the game's themes about fragmented identity and reality instability without requiring explicit explanation. It's sophisticated visual storytelling.

How does Grasshopper maintain creative vision across multiple projects?

Grasshopper maintains consistency through shared artistic philosophy implemented by core team members who've worked together for years. The studio shares DNA across projects: distinctive visual language, pop culture saturation, willingness to prioritize aesthetic over mechanical perfection, and commitment to weird. This consistency doesn't mean repetition. Each game experiments with specific vision while maintaining recognizable Grasshopper identity.

Why is Grasshopper's willingness to accept financial struggles important?

It's important because it preserves space for creative expression in an industry increasingly pressured toward commercial safety. By demonstrating that uncompromising weird games can sustain a studio, Grasshopper proves that profitability isn't the only measure of success. This matters for younger developers considering whether creative compromise is necessary. Grasshopper shows it's not. It's difficult, but it's possible.

What role do references play in Romeo is a Dead Man's narrative?

References aren't just Easter eggs. They're structural to how the game communicates meaning. By constantly referencing previous Grasshopper games and pop culture touchstones, Romeo creates layers of interpretation. New players experience weird action game with pop culture callbacks. Long-time fans experience commentary on Grasshopper's own history. This multi-layered approach rewards engagement across different levels of player knowledge.

How does Romeo is a Dead Man compare to mainstream action games?

Unlike mainstream action games that optimize for broad appeal and mechanical depth, Romeo deliberately prioritizes aesthetic vision and narrative weirdness. It doesn't include features designed for accessibility or maximum player retention. Its combat isn't balanced for competitive play. Its narrative deliberately resists clear explanation. This specificity makes it less accessible than mainstream games but more cohesive and authentic in its vision. You're experiencing what the creator wanted to make, not what market research suggested.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Vitality of Uncompromising Vision

When you step back and examine Grasshopper Manufacture's entire catalog, what becomes clear is that commercial success was never the metric that mattered. Over nearly three decades, Suda 51 and his team have built something much more valuable: a studio with a distinctive voice that players immediately recognize. A studio that proves uncompromising creative vision can sustain itself through community loyalty and authentic artistic expression.

Romeo is a Dead Man represents the culmination of this philosophy. It's a game that could never exist within mainstream publisher frameworks. It's too weird. Too visually grotesque. Too narratively demanding. Too committed to aesthetic expression over mechanical innovation. It would fail focus testing. It would alienate demographic segments. It would be considered commercially risky.

Yet it exists. And it exists because Grasshopper has built an economic model and community relationship that enables making exactly what the studio wants to make. The team has learned, over decades, how to create visually distinctive, narratively complex, deliberately weird games that engage specific audiences powerfully.

What makes Romeo is a Dead Man special isn't that it revolutionizes game design. It doesn't. It's that the game represents an artist at full maturity, fully committing to distinctive vision without compromise. Every visual choice reinforces thematic content. Every narrative decision serves the core premise. Every mechanical element contributes to aesthetic cohesion. This integration of design elements is rare. Most games compromise somewhere. Romeo doesn't.

For players seeking games that feel like genuine creative expression rather than corporate products, Romeo is a Dead Man is essential. For developers questioning whether creative compromise is necessary for sustainability, Grasshopper's existence answers definitively: it isn't. For the gaming industry more broadly, Grasshopper's continued success suggests that space still exists for visually distinctive, narratively complex, deliberately weird work.

In an industry increasingly consolidated around financial predictability, Grasshopper stands as proof that genuine artistic vision still matters. Romeo is a Dead Man is the fullest expression of this vision yet. It's bizarre. It's bloody. It's exactly what makes Grasshopper special. And it's a reminder that the best games aren't always the most commercially successful ones. Sometimes they're just the ones made by people committed to expressing something true, something weird, something genuinely their own.

Key Takeaways

- Grasshopper Manufacture proves that uncompromising creative vision can sustain a studio for decades without mainstream commercial success by prioritizing community engagement over market penetration

- Romeo is a Dead Man exemplifies how visual grotesquerie, surreal narrative, and deliberate mechanical roughness integrate into cohesive aesthetic expression rather than serving individual functions

- The studio's willingness to redefine commercial success from blockbuster sales to community loyalty enables creative risk-taking that mainstream publishers cannot afford

- Pop culture references and self-referential narrative function as structural narrative devices creating multiple layers of meaning for audiences with varying prior knowledge

- Grasshopper demonstrates that aesthetic and thematic coherence matters more to dedicated audiences than mechanical polish or accessibility optimization

Related Articles

- Horizon Zero Dawn 3 Release Date: PS6 Launch Window [2025]

- Riot Games 2XKO Layoffs: Inside the Fighting Game Crisis [2025]

- PlayStation State of Play February 2026: What to Expect [2025]

- How Animal Crossing Started as a Dungeon Crawler: Nintendo's Hidden History [2025]

- Steam Early Access Release Dates: How Developers Benefit [2025]

- Cairn Game Review: The Climbing Journey That Teaches Perseverance [2025]

![Grasshopper Manufacture's Romeo is a Dead Man: The Studio's Boldest Vision [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/grasshopper-manufacture-s-romeo-is-a-dead-man-the-studio-s-b/image-1-1770738117295.png)