The Unexpected Genesis of Nintendo's Most Beloved Life Sim

Animal Crossing feels like the opposite of what a video game was ever supposed to be. There's no conflict. No score to chase. No final boss waiting at the end of a tower. You can't lose. You can't win. You just exist in a small village populated by anthropomorphic animals, catching bugs, fishing in rivers, and slowly paying off a house you didn't ask for to a capitalist tanuki named Tom Nook.

Yet somehow, this game—which arrived in Japan in 2001 as a sort of experimental footnote—became one of Nintendo's most enduring franchises. It's been ported to every Nintendo console since. Millions of people spent a global pandemic talking to virtual villagers instead of real humans. The franchise has generated billions in revenue across mainline games, spin-offs, merchandise, and collaborations.

But here's what most people don't know: Animal Crossing almost wasn't Animal Crossing at all.

The game's origin story is deeply human, rooted in one man's experience of displacement and loneliness. It's also tangled up in one of Nintendo's most spectacular hardware failures. And somehow, despite all the obstacles, wrong turns, and compromises along the way, the core emotional idea never got lost in translation.

This is the story of how a game about nothing became everything.

TL; DR

- Original Concept: Animal Crossing began as Katsuya Eguchi's response to loneliness after moving from Chiba to Kyoto to work at Nintendo in 1986, inspiring him to create a "communication game"

- Hardware Foundation: The game was developed specifically for the 64DD, Nintendo's disk-writing add-on for N64, which offered 64 MB of rewritable storage and a real-time 24-hour clock

- Failed Hardware, Successful Game: The 64DD sold only ~15,000 units before discontinuation, but Animal Forest (the original title) released as the last N64 game in 2001 and became a massive success

- Revolutionary Design: Animal Crossing introduced the concept of a game that operates on its own schedule, continuing even when you're not playing, fundamentally changing game design philosophy

- Emotional Core: The franchise success proves that emotional authenticity and genuine design philosophy can overcome technical limitations and hardware failures

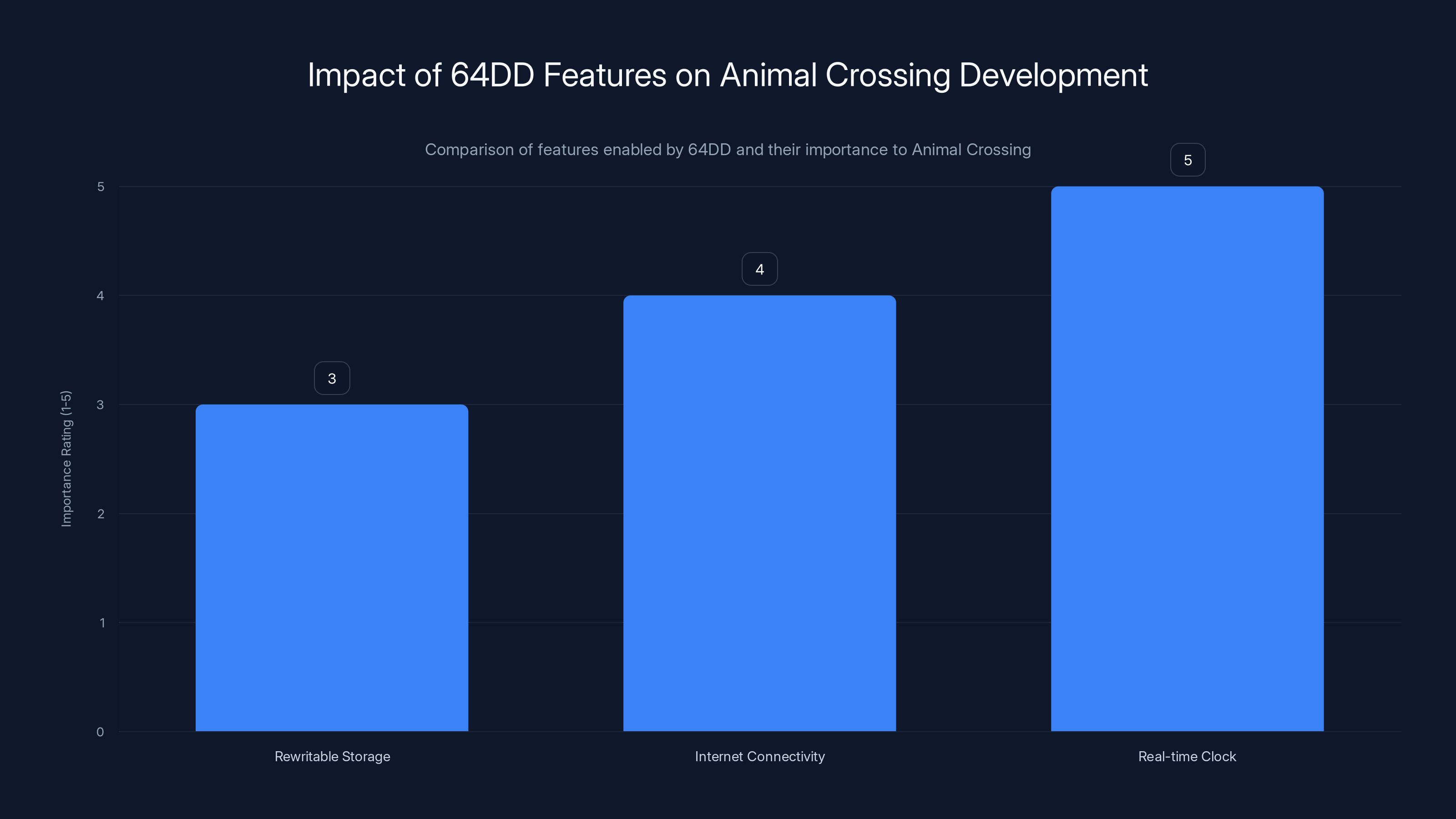

The real-time clock was the most crucial feature from the 64DD for Animal Crossing, enabling the game's persistent world concept. Estimated data.

Katsuya Eguchi's Homesickness: The Emotional Root

When Katsuya Eguchi made the decision to leave Chiba Prefecture and move to Kyoto in 1986 to join Nintendo, he was making a choice that many talented young professionals face: opportunity or proximity to loved ones. Nintendo was—and is—concentrated in Kyoto, far from where Eguchi's family and friends lived. The separation hit harder than he'd anticipated.

Years later, speaking to Edge magazine in 2008, Eguchi reflected on this period with surprising candor: "When I moved to Kyoto, I left my family and friends behind. In doing so, I realized that being close to them, being able to spend time with them, talk to them, play with them, was such a great, important thing. I wondered for a long time if there would be a way to re-create that feeling, and that was the impetus behind the original Animal Crossing."

This isn't unusual motivation for creative work. Many of the best games, films, and art emerge from personal struggle. What's unusual is how literally Eguchi took this challenge. He didn't want to make a game about overcoming loneliness. He wanted to make a game that could, in some way, function as a substitute for connection. A space where someone could check in regularly, like you might text a friend. Where something was always happening, like life in a real community.

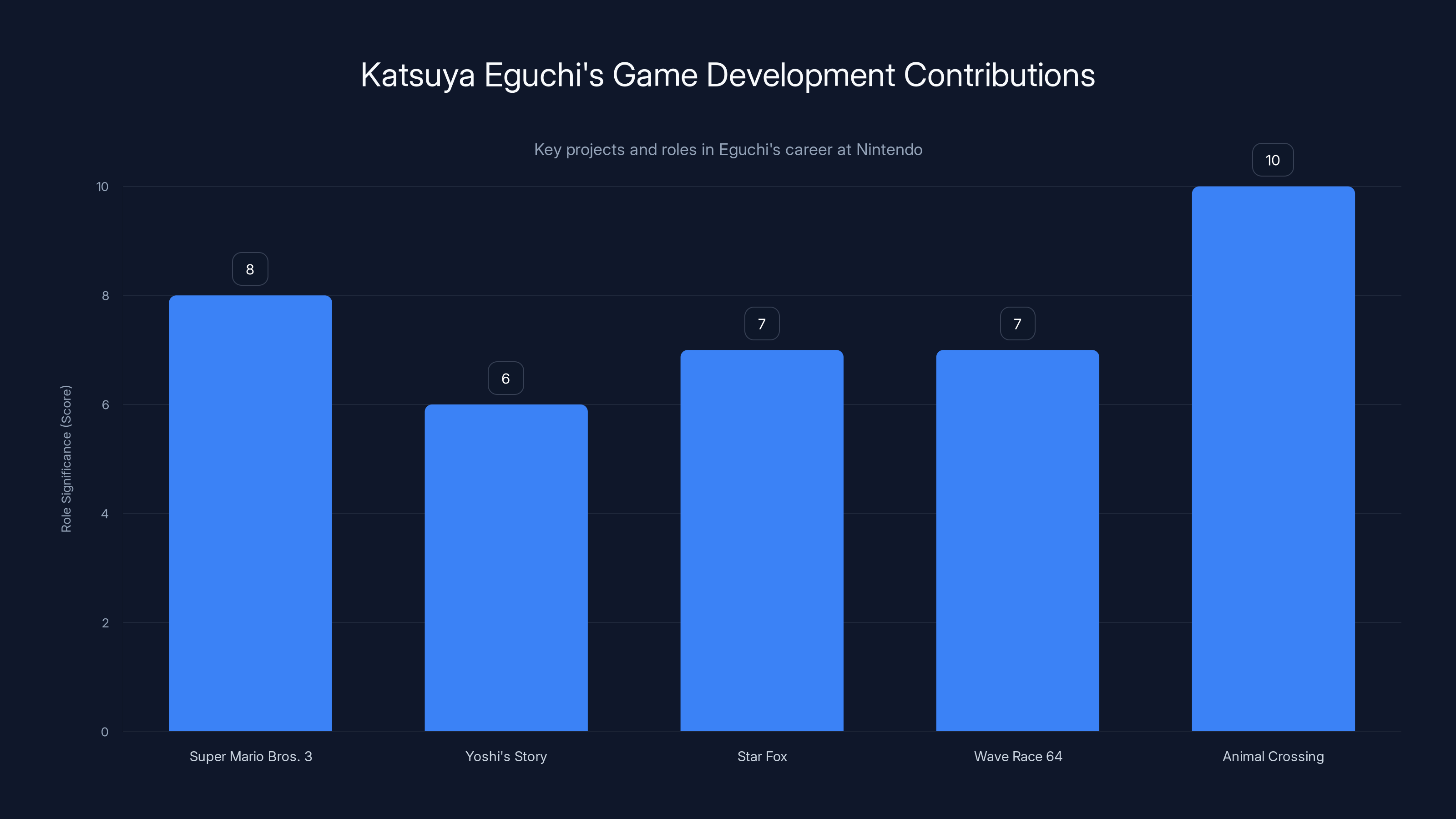

Before he could pursue this idea, though, Eguchi had a long career ahead of him doing other things. He worked as a level designer on Super Mario Bros. 3, one of the defining games of the 8-bit era. He contributed to Yoshi's Story, a colorful and experimental platformer. He directed Star Fox, which pioneered the use of the Super FX chip to create 3D graphics on a 2D console. He directed Wave Race 64, a jet ski racing game that showcased the Nintendo 64's water rendering capabilities.

These were all significant credits, meaningful contributions to Nintendo's portfolio. But they weren't the game Eguchi kept thinking about. The game about connection. The communication game.

In the late 1990s, the timing finally aligned. Nintendo was preparing a hardware accessory that, for the first time, made Eguchi's vision technically feasible.

The 64DD: Nintendo's Bold Bet on Rewritable Storage

Today, cloud storage and digital downloads are ubiquitous. Game updates ship automatically. Your console connects to the internet as a matter of course. It's easy to forget that in the 1990s, these weren't givens. Game cartridges were read-only. Once manufactured and shipped, a game couldn't change. If there was a bug, tough luck. You bought what was on the cartridge.

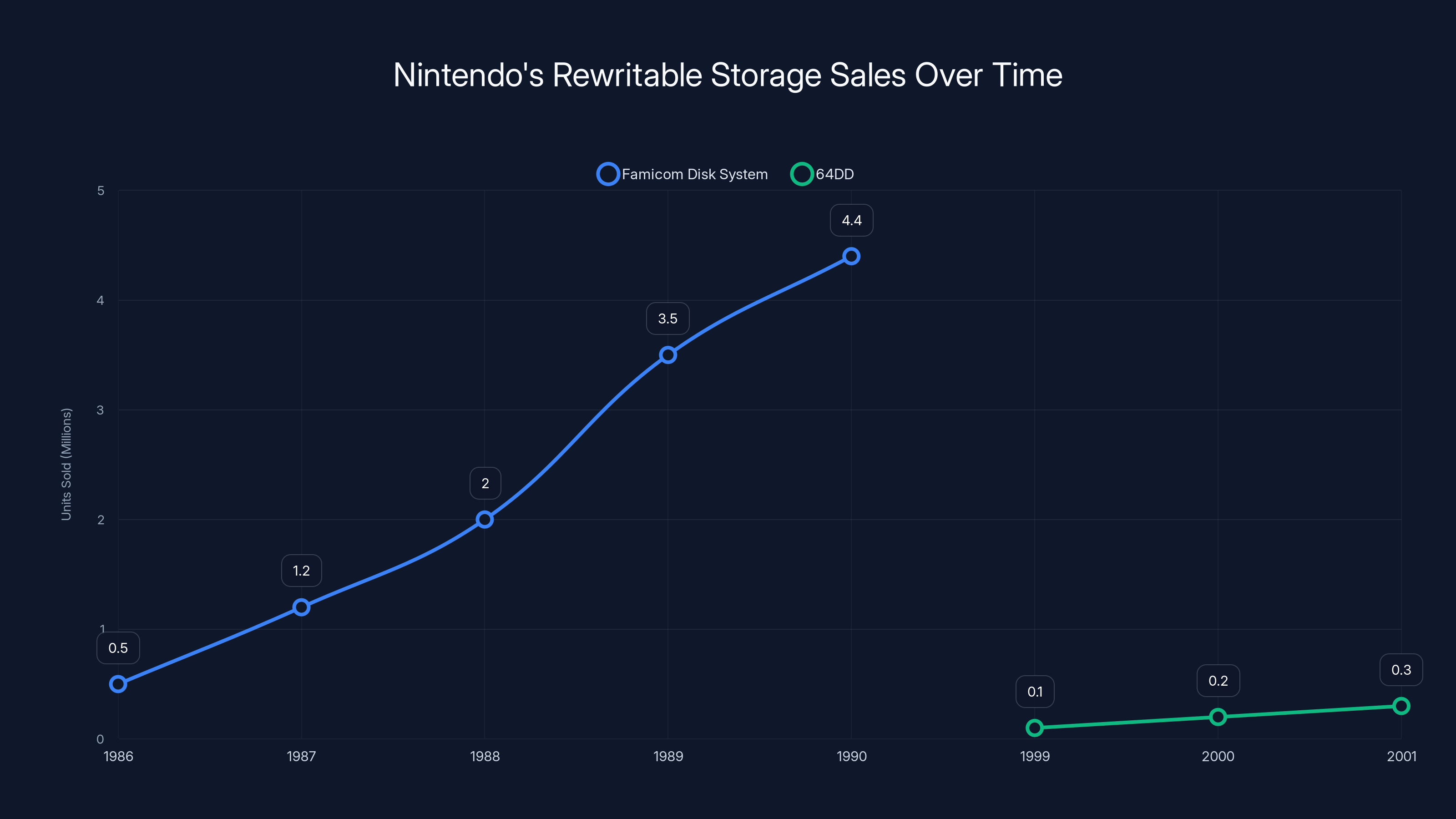

Nintendo had actually pioneered rewritable storage for home consoles with the Famicom Disk System. Released in December 1983 in Japan, the Disk System used 3.5-inch floppy disks instead of cartridges. Players could bring their disks into game shops, where they'd use specialized kiosks to rewrite the disks with new games or data. It was a smart system for the era. The disks were cheaper to manufacture than cartridges. Players had flexibility in what games they owned. Nintendo could update games or release new content incrementally.

The Famicom Disk System was a commercial success, selling approximately 4.4 million units in Japan between 1986 and 1990. It remains fondly remembered in Japanese retro gaming culture. Nintendo still sells themed merchandise featuring Diskun, the charming mascot of the system—bright-yellow card holders featuring Mr. Disk are available in Nintendo's official stores even today.

By the mid-1990s, with the Nintendo 64 in development, Nintendo was thinking about how to bring rewritable storage to 3D gaming. The result was the 64DD—the Disk Drive add-on for N64. It connected to the bottom of the console, accepting 64 MB rewritable disks. The storage capacity sounds modest today, but in 1996 when it was announced, it represented genuine innovation.

More importantly for Eguchi's vision, the 64DD came with something unprecedented: internet connectivity and a real-time clock. The system could connect to the internet to download content and share player data. And it had a twenty-four hour clock that kept ticking even when the console was off. This meant a game running on the 64DD could operate on its own schedule, independent of when a player actually used the console.

This is the crucial detail. This is what made Eguchi's communication game possible.

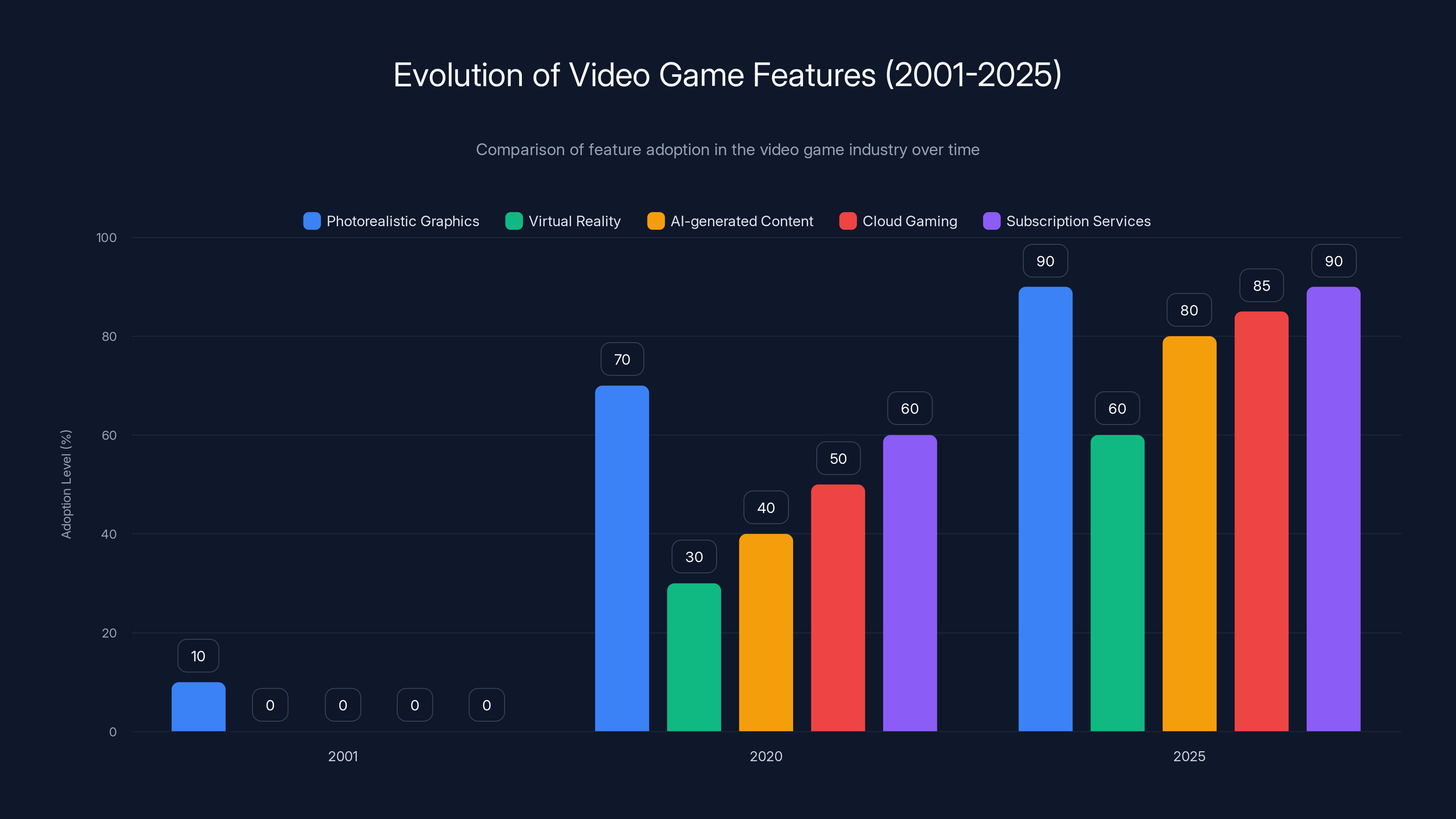

Estimated data shows significant growth in advanced gaming features from 2001 to 2025, highlighting the industry's technological evolution.

The Real-Time Clock: The Secret Ingredient

Understand what the real-time clock meant for game design: it fundamentally broke the model of games as discrete experiences with clear start and stop points. A game with a real-time clock could model something like a real world. Time would pass regardless of player input. NPCs could have schedules. The world could change between sessions. A player could open the game on Monday and find that things had happened over the weekend without their intervention.

This was genuinely novel. In 1996, most games operated on "game time." When you pressed start, time in the game began. When you quit, time stopped. The game existed in a kind of stasis, waiting for you. A real-time clock inverted this. The game existed continuously, with or without you. You were checking in on a world, rather than inhabiting it on demand.

For Eguchi's communication game, this was perfect. He wasn't trying to make a competitive experience or a narrative journey. He was trying to create something more like a persistent neighborhood—a place you'd visit regularly, where you'd see familiar faces, where small things would happen that you'd miss if you didn't check in.

Nintendo made a big promotional push when the 64DD was announced. The company showed off a demo of a Zelda game being developed for the system, a game that would eventually become Ocarina of Time. The tech press got excited. This was the future of Nintendo gaming: rewritable content, internet connectivity, persistent worlds.

Except it wasn't. And that's where the real story gets interesting.

The 64DD's Spectacular Failure

The 64DD was released in Japan in December 1999. It was discontinued in February 2001. In its brief existence, it sold approximately 15,000 units. By any measure, it was a failure.

There were several reasons. The system was expensive, adding significant cost to the already-pricey N64. The selection of software was limited. The internet connectivity, while innovative, arrived before broadband was common in Japan. The rewritable disks had a reputation for reliability issues. And perhaps most importantly, the cartridge-based N64 itself was already on the decline in Nintendo's priorities. The company was already looking ahead to the Game Cube, a fully optical-disc-based console that would make the 64DD's rewritable disks seem redundant.

Software publishers pulled back from the system. Several games were cancelled. Almost all of the software that had been in development for the 64DD was transmuted into something else: they were adapted and released on the N64 or the Game Cube instead.

This is what happened to Eguchi's communication game. It was reworked for the N64's cartridge format and released in December 2001, just after the 64DD had been officially discontinued. It was released under the Japanese title Doubutsu no Mori, which translates to "Animal Forest." It shipped as the absolute last game ever released for the N64 console.

If you were writing a Hollywood screenplay, you couldn't ask for better dramatic irony. The hardware that inspired a game's existence was dying even as the game was being released on hardware it wasn't designed for.

Porting a Dream Across Hardware: Animal Forest on N64

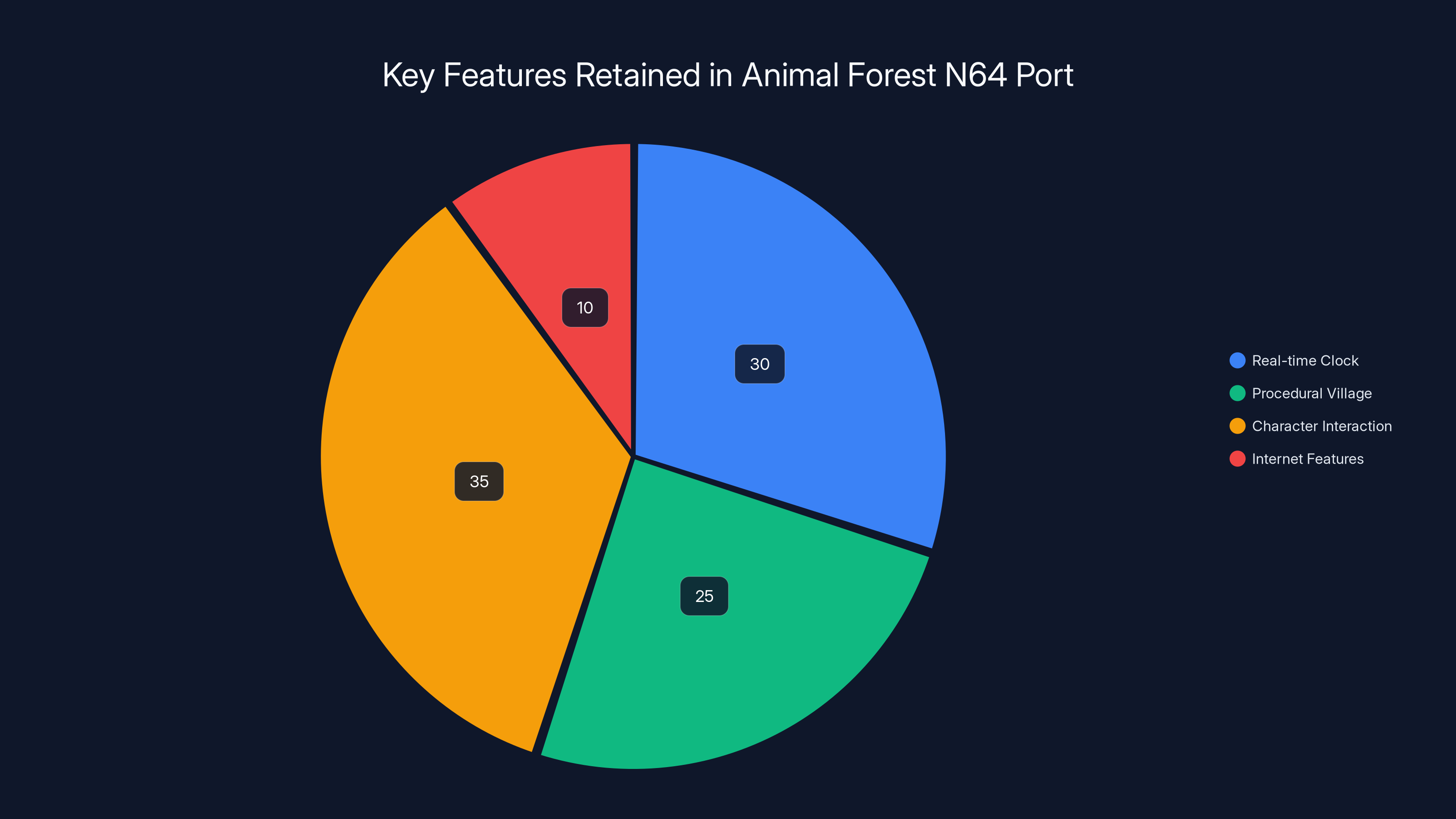

When Eguchi and his team were forced to adapt Animal Forest for the N64 cartridge, they couldn't keep everything they'd designed for the 64DD. The cartridge format meant significantly less storage. The internet connectivity had to be stripped out, at least in the initial version. The real-time clock had to be preserved, though—that was non-negotiable, because the entire game was built around it.

What's remarkable is that Animal Forest worked anyway. The game arrived in 2001 for the N64 with most of its core vision intact. You created a character and arrived in a procedurally generated village as the only human in a population of animal residents. You were immediately roped into purchasing a house from Tom Nook, a somewhat sinister raccoon character with ties to Japanese folklore. You paid off this debt incrementally, room by room. In the meantime, you caught fish in rivers. You caught insects in trees and grassland. You shook trees for fruit and fossils. You talked to your animal neighbors. You sent and received letters. You decorated your house and your town.

There was no objective. No win condition. No failure state. You just existed in this space, and the game changed based on real-world time. If you played in the morning, you'd see morning-specific NPCs and activities. If you played at night, the town was different. If you didn't play for a week, your house would fill with cockroaches. If you didn't play for months, your animal neighbors would get annoyed that you'd abandoned them.

It was oddly intimate. The game was designed to be played in short sessions, regularly, like checking in with actual people in your life. It was designed to make you feel like you had responsibilities in this space, even though those responsibilities had no real consequences.

The game's visual style was deliberately charming and low-stakes. The animals were designed to be cute but also slightly unsettling. Your character was a featureless void with eyes. The architecture was simple. The color palette was warm but not aggressive. Everything about the design language communicated: this is a space for you to relax, not a space to be challenged.

The Famicom Disk System was a commercial success in the late 1980s, selling approximately 4.4 million units. In contrast, the 64DD, released in 1999, sold modestly with an estimated 0.3 million units by 2001. Estimated data.

The Eerie Comfort of a Town That Doesn't Need You

There's something genuinely unsettling about Animal Forest when you first encounter it. You arrive in a town as a stranger. The animal residents acknowledge your presence but have no particular attachment to you. They have their own lives, their own schedules, their own houses. You're not the hero of this story. You're not saving anyone or earning a victory. You're just another newcomer who needs housing.

Tom Nook, the raccoon landlord, immediately pressures you into a mortgage. Pay him back, room by room. It's a gentle but persistent pressure, and it's part of what makes the game work. You have a reason to fish and hunt insects—you're earning money to pay off your debt. But the debt is never-ending. Once you finish the original house, Nook offers expansions. Once you expand, he offers a second floor. Then a basement. Then you can move to bigger houses entirely.

It's capitalism, but expressed in the gentlest possible way. And it's a brilliant game design choice because it gives you agency without forcing you down any particular path. You could pay off your initial house quickly and stop. You could play for hundreds of hours, slowly expanding your estate. The game doesn't care. The pressure is there, but it's never punishing.

The animal residents are the heart of the experience, though. Each one has a personality type—lazy, peppy, cranky, snooty, etc. They have favorite colors and furniture styles. They tell you jokes. They send you letters. If you talk to them every day, they warm up to you. If you ignore them for weeks, they mention your absence. If you ignore them for months, they move away.

This was genuinely novel game design. You could build relationships in this game, but they required maintenance, just like real relationships. You could neglect those relationships, and they would degrade. The game was modeling actual social dynamics without being heavy-handed about it.

A Game About Existence, Not Achievement

What made Animal Forest revolutionary wasn't any single feature. It wasn't the best-looking game on the N64. The audio was pleasant but not spectacular. The gameplay mechanics—fishing, catching insects, catching fish—were simple, almost boring.

What made it revolutionary was the philosophy underlying the entire design. Eguchi had created a game that wasn't about achievement. It wasn't about progression toward an end state. It wasn't about mastery or skill or victory. It was about existence.

You exist in this town. Every day you visit, the town has changed slightly. Every season brings new fish, new insects, new events. You're not trying to catch every species (though you can if you want). You're not trying to decorate your house in any particular way (though the game offers suggestions). You're just living in this space, and through the act of living in it regularly, you build something that feels like ownership and connection.

This was a profound departure from the typical Nintendo game. Nintendo built its reputation on games about accomplishment. Mario was about jumping to the flag. Zelda was about collecting items and defeating a final boss. Metroid was about mastery and exploration and uncovering secrets. Donkey Kong Country was about precision platforming.

Animal Forest said: what if the game is just about being somewhere? What if the victory condition is showing up?

For Eguchi, who had been thinking about connection and loneliness for over a decade, this was the answer to the question that had haunted him since 1986. You couldn't recreate real friendship in a game, but you could create a space where checking in regularly felt rewarding. Where the world changed between visits. Where absence was noticed. Where small gestures of care—talking to neighbors, sending letters, catching fish to sell and earn money—felt meaningful even though they didn't "mean" anything by conventional game logic.

The Transition to Game Cube and Global Expansion

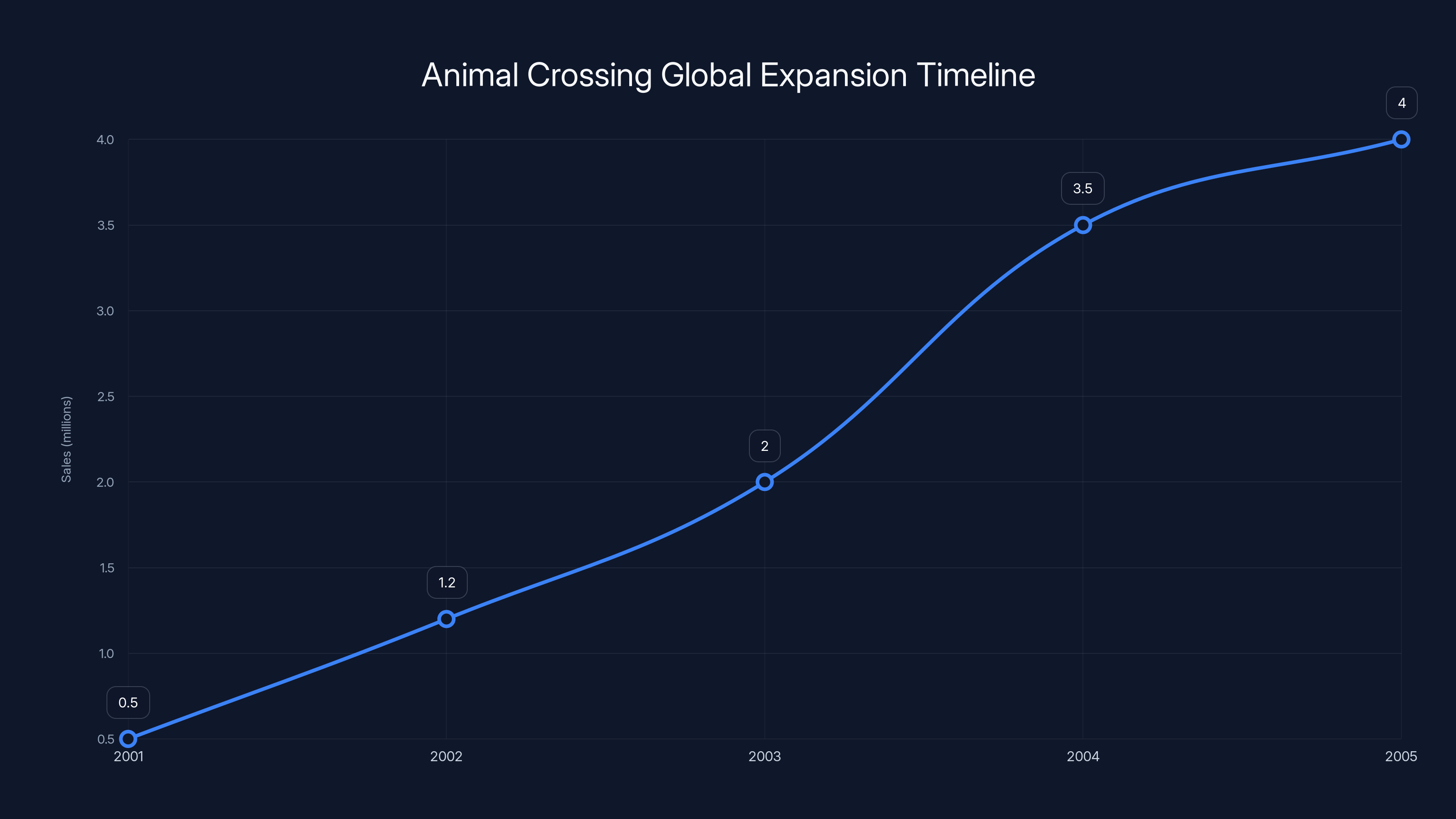

Animal Forest on the N64 was a success in Japan, but it was a quiet success. Sales figures weren't published widely, but the game clearly resonated with Japanese players. It arrived at the very end of the N64's lifecycle, so it was never as ubiquitous as some of the console's earlier hits. Most Western players never encountered it.

Then, in 2002, Nintendo released Animal Crossing on the Game Cube, the company's newest console. This version included the internet connectivity that the original 64DD game had promised. More importantly, it included an expanded feature called the "island," which allowed players to visit other people's towns through trading disks or, eventually, through online connectivity.

The Game Cube version also got a Western release, arriving in North America in September 2002 and in Europe in 2004. This is where the franchise truly exploded. Western audiences, who had never encountered the N64 original, met Animal Crossing for the first time on Game Cube. And many of them became obsessed.

Part of this was timing. The Game Cube was struggling to establish itself in the market against the Play Station 2. Nintendo needed strong software to drive console sales. Animal Crossing found an audience that Nintendo hadn't traditionally targeted: adult players, casual players, and particularly women, who often felt alienated by the competitive and achievement-focused world of video games.

The game's lack of consequences appealed to these players. You couldn't make "wrong" choices in Animal Crossing. You couldn't die. You couldn't lose. Your friends' progress didn't outpace yours in some competitive ladder. Everyone was just existing in their own town, at their own pace, building something that reflected their own aesthetic preferences.

It was, in retrospect, ahead of its time. The game anticipated what would become a major trend in gaming: cozy games, games about relaxation rather than challenge, games where the emotional experience was the point rather than the mechanical challenge.

Animal Crossing's global expansion began with its GameCube release in 2002, leading to a significant increase in sales, especially after its European release in 2004. (Estimated data)

The 24-Hour Cycle That Changed Everything

Let's pause for a moment on the real-time clock, because it deserves more analysis. This feature is so fundamental to Animal Crossing's identity that it's easy to take for granted. But in 2001, it was genuinely innovative game design.

The real-time clock meant that each player's experience was slightly different depending on when they played. You couldn't see all the content in a single day. You couldn't experience all four seasons in a single week. You had to play at different times of day to encounter different NPCs and different events. If you wanted to catch all the fish and insects in the game, you'd need to play through all four seasons, at different times of day, across multiple playthroughs.

This design choice essentially eliminated the possibility of "completing" Animal Crossing. You could fill your museum with every possible specimen. You could pay off your house completely. You could collect every piece of furniture. But you'd need to play regularly across many months to do it. And by the time you finished the museum, new seasonal events would be coming around again.

In a way, this was the inverse of what video game design had been trending toward. The industry was increasingly focused on creating games with defined endpoints. Games you could "beat." Games that provided a sense of completion and closure. The idea was that players wanted to feel like they'd accomplished something.

Eguchi's insight was different: what if players wanted to feel like they had a place they belonged? What if the appeal wasn't crossing the finish line, but having a reason to come back?

Why Tom Nook Works: The Gentle Antagonist

Tom Nook is one of video game's most interesting characters, and his appeal lies in how he occupies a strange moral space. He's a capitalist, but he's not a villain. He's predatory, but he's not threatening. He's always cheerful, always helpful, always ready to make another deal with you.

In the original Animal Forest, Tom Nook runs a general store and also handles your real estate. You arrive in town, and he's the first NPC you meet (after a tutorial from a pelican named Pelican Pete). He offers you a house, then walks you through a home loan process. You choose your mortgage amount, and based on that, you owe him a debt.

But here's the brilliant part: Tom Nook never threatens you. He never enforces the debt. You could, theoretically, never pay him a single bell (the game's currency). You could go fishing and catching insects and selling those instead. Your house would never expand. Tom Nook would never evict you. He'd just be there, cheerfully reminding you that you owe him money whenever you visited his shop.

The pressure is entirely psychological. You want to pay off your debt because the game is structured so that earning money is how you interact with the world. You catch fish to sell. You catch insects to sell. You dig up fossils to sell. The game gives you these activities, and they naturally result in money accumulation, which naturally results in paying off your debt.

Tom Nook is the mechanism through which this works. He's not greedy in any menacing way. He's just a businessman who runs a shop and offers mortgages. He's doing what he does, and you're doing what you do, and the interaction between those two things creates a compelling feedback loop.

This is, in retrospect, the most adult thing about Animal Crossing. The game models economic relationships in a way that's honest but not cynical. Work and commerce are part of life. The game doesn't pretend otherwise. But it also doesn't make you feel bad about it. You're not oppressed by Tom Nook. You're just engaging with the economic system that makes the village function.

The Accidental Life Sim: What Eguchi Created Without Meaning To

Animal Crossing predates the modern "life sim" genre by years. Stardew Valley didn't exist yet. The Sims franchise was more focused on detailed simulation than on the cozy, relaxing experience that Animal Crossing offered. No Vita, Journey, or any of the other cozy games that would eventually become a recognizable genre.

Eguchi wasn't trying to create a new genre. He was trying to create a communication tool. A game that mimicked the experience of checking in with distant friends. A game where the world operated on its own schedule, so there was always something new when you logged in.

But what he actually created was something larger: a game that was about the experience of existing in a place. A game where your presence mattered, but not because of what you achieved. A game where the point was to notice how the world changes when you're not looking at it.

This accidental creation became more important as the franchise developed. Later iterations of Animal Crossing would add more explicit social features—the ability to visit other players' towns, the ability to trade items online, the ability to collaborate on town projects. But the core remained what Eguchi had envisioned: a space you check in on regularly, where small changes accumulate over time, where your choices about decoration and community are reflected in the physical space you inhabit.

Eguchi's role in Animal Crossing is rated highest due to its personal significance and innovation in fostering virtual community connections. Estimated data.

The Nintendo 64 as Unlikely Launch Platform

There's something poignant about Animal Forest being released as the last game for the Nintendo 64. The N64 was, by 1999-2000, already in decline. The Nintendo 64 had shipped in 1996 to great fanfare. It was the first home console to ship with a built-in 3D graphics processor. It had Pilotwings 64 and Super Mario 64 at launch, two games that essentially defined what 3D gaming could be.

But the N64 had limitations that became increasingly apparent. The cartridge format meant expensive production costs and limited storage. Developers like Square Enix and Enix moved to the Play Station, where CD-ROM storage was cheaper and more abundant. The N64's library was smaller and more Nintendo-focused than the Play Station's.

By 1999, the writing was on the wall. Nintendo was clearly preparing the Game Cube. Investment in N64 software was winding down. Publishers were shifting their focus. The notion that Animal Forest would be the N64's swan song—released after the company had already moved on—captures something important about the franchise's origin.

Animal Forest wasn't a planned tentpole release. It was a game that existed because one designer had a personal vision, and Nintendo was willing to give him space to pursue it, even as the hardware it was originally designed for was being phased out. The fact that it worked anyway, that it resonated with players even as a compromised port of a game designed for a failed peripheral, speaks to the fundamental strength of the design.

The DNA of Connection: How Loneliness Became Art

There's a line from the filmmaker Werner Herzog that feels relevant here: "You must have a vision. The vision is the most important thing." Eguchi had a vision born from genuine personal loneliness. He wanted to create something that would let you maintain a connection with a community even when physically separated from it. That vision remained intact even as the technology around it changed.

The 64DD failed. The cartridge port succeeded. Eventually, the Game Cube iteration introduced online connectivity that made the original vision more feasible. But the emotional core—a game about showing up regularly for a place, about maintaining a connection through small, consistent actions—remained the same across all these iterations.

This is rarer than you'd expect in game design. Visions frequently get compromised, diluted, or entirely abandoned when faced with technical constraints or hardware changes. What's remarkable about Animal Crossing is that the essential idea survived and even thrived under constraint.

Part of this was surely due to Eguchi's persistence. He clearly believed in this idea enough to rework it for new hardware, to adapt rather than abandon. Part of it was Nintendo's culture of giving talented designers space to pursue their visions, even when those visions didn't fit neatly into corporate strategy.

But part of it was also just the universality of the emotional need Eguchi was addressing. Loneliness and the desire for connection are fundamental human experiences. A game that addressed those needs authentically would resonate, regardless of the technical implementation.

The Franchise That Nobody Expected

If you'd suggested in 2001 that Animal Forest would become one of Nintendo's most valuable franchises, most people would have laughed. It was an odd game, a technical compromise, released at the tail end of a console's lifecycle. It had no combat. No clear objectives. No narrative momentum. It was designed to be played in short sessions, regularly, across many months.

In the context of game design in 2001, it was genuinely weird.

But it was also authentic. Eguchi had spent fifteen years thinking about connection and loneliness. He'd translated those personal struggles into a game design that genuinely attempted to model what it felt like to maintain a community from a distance. The game had flaws—the early iterations had limited content, the villagers could be repetitive, the fishing and bug-catching mechanics were simple to the point of being almost meditative rather than engaging.

Yet players came for those things. They came for the simplicity. They came for the meditative quality. They came for the sense that they had a place that needed them, even if that place was virtual.

In 2020, when a global pandemic forced millions of people to isolate, Animal Crossing: New Horizons became a cultural phenomenon. People who hadn't thought about the franchise in years returned to it. People who'd never played a game in their lives started playing. The game, which had always been about connection across distance, suddenly became a lifeline for people who could no longer connect in person.

Some of this was luck. The game released in March 2020, right as lockdowns were beginning. Some of it was brilliant timing—Nintendo had been working on a major new entry in the franchise, and it happened to arrive when people needed it most.

But much of it was also the original design philosophy coming through. Eguchi had created a game about showing up regularly for a place and for a community. In 2020, that wasn't a nice-to-have. It was, for many people, the only way to maintain a sense of community.

Estimated data shows that the real-time clock and character interaction were prioritized in the N64 port, while internet features were largely omitted.

The Real Innovation: Persistence Without Pressure

When we talk about "live service" games today, we usually mean games that continuously update with new content, that encourage daily login streaks, that use FOMO (fear of missing out) to keep players engaged. Games like Fortnite, Destiny, or The Elder Scrolls Online. Games that create a sense of obligation.

Animal Crossing invented a different model of persistence. A game that continues without you, but doesn't punish you for absence. A world that changes with seasons and time of day, but doesn't lock you out of content if you miss a particular window.

You can miss the cherry blossom festival if you don't play in spring. But you can catch cherry blossoms again next spring. You can miss your villager's birthday. But there will be other birthdays, other chances to celebrate. The game never punishes you for taking a break. It just welcomes you back to a world that has continued without you.

This is genuinely humane game design. It recognizes that people have lives outside of video games. It doesn't try to trap them through obligation. It instead creates a world that's appealing enough to return to voluntarily.

In 2025, when "mental health" and "digital wellness" are increasingly important topics in gaming, this design philosophy feels prescient. Eguchi wasn't thinking about these terms in 1986. But he was thinking about creating a space where people could feel connected without feeling obligated. Where they could relax instead of achieve. Where the game asked something of them—show up regularly—but didn't demand anything of them—you can never fail.

Echo of the Original Idea: How Loneliness Became Community

The irony of Animal Crossing's history is that a game born from one man's loneliness became a vehicle for community connection. Eguchi created it as a way to maintain relationships across distance. But what it actually created was a way for strangers to share a common experience, to visit each other's towns, to send gifts and letters to people they'd never met in person.

The franchise evolved into something bigger than Eguchi's original vision, but that vision was never diluted. Every iteration of Animal Crossing maintains the core idea: a space you check in on regularly, where your presence matters, where small choices accumulate into something meaningful.

In the N64 original, this was limited by technology. You couldn't really share your town. You couldn't easily visit others' towns. The game was, in many ways, a solitary experience. You were alone in your village (save for the animal residents), and your village was yours alone.

But as the technology improved—as internet connectivity became ubiquitous, as cloud storage made sharing easier—the game could express Eguchi's vision more fully. Animal Crossing: New Horizons let you visit your friends' islands in real-time. You could see their decorations, tour their designs, collaborate on island projects.

Yet the game maintained the core: no pressure, no competition, no hierarchy. You could play alone, or you could play together, but either way, you were just existing in a space that you'd built.

The Lesson for Game Design: Vision Persists

If there's a lesson in Animal Crossing's origin story, it's this: strong vision persists through technical constraint. Eguchi had an idea rooted in genuine emotional need. He wanted to create a game about connection. For over a decade, the technology wasn't there to support it fully.

But instead of abandoning the vision, he adapted it. When the 64DD failed, he reworked the game for the N64. When the Game Cube arrived with better capabilities, he expanded the game. When online connectivity became possible, he used it to fulfill the original vision more completely.

The game that arrived in 2001 as Animal Forest was a compromise. It couldn't do everything Eguchi had imagined for the 64DD. But it was true to the core idea. It was a game about showing up, regularly, for a place. It was a game that continued even when you weren't playing. It was a game that made you feel like you belonged to a community, even if that community was entirely virtual.

That's not nothing. That's actually everything.

Looking Back from 2025: What Has Changed, What Hasn't

In the quarter-century since Animal Forest's release, the video game industry has transformed completely. We have photorealistic graphics, virtual reality, AI-generated content, cloud gaming, and game libraries numbering in the millions via subscription services.

Yet Animal Crossing remains fundamentally unchanged in its core design. The 2020 New Horizons release looks dramatically better than the 2001 original. It has more content. More customization options. Online multiplayer. But the basic loop—catch fish, catch insects, decorate your space, check in with your villagers—remains essentially the same.

This stability, this refusal to chase trends, is part of what makes Animal Crossing special. While other franchises constantly add new features, new mechanics, new competitive elements, Animal Crossing has stayed true to Eguchi's original vision.

It doesn't have a battle pass, though it could. It doesn't have seasonal events locked behind paywalls, though it could. It doesn't have a competitive ladder or achievement hunting, though it could. Instead, it remains a game about existence, about regularity, about building a place that reflects your aesthetic and values.

In 2025, this feels radical. In an industry dominated by engagement metrics and monetization strategies, a game that asks you to relax and shows up regularly without demanding anything from you is genuinely countercultural.

The Unexpected Legacy of Failure

The 64DD is remembered, when it's remembered at all, as a failure. A failed experiment. A technology that couldn't compete. A footnote in Nintendo history.

But the 64DD also, indirectly, gave the world Animal Crossing. The disk-writing technology was what inspired Eguchi to think about a game with a real-time clock and persistent world. The ambition of the project—to create something new on new hardware—is what motivated the design.

Sometimes the things that look like failures on the surface created the conditions for success. Nintendo took a risk on new technology. The technology failed, but the software that grew out of it succeeded beyond anyone's expectations.

This is, in many ways, what defines the best creative work: it's born from genuine human need, developed with appropriate constraints, and launched with enough belief that it survives setbacks. Animal Crossing is the result of one man's loneliness, one failed piece of hardware, and one company's willingness to let talented designers pursue their visions even when they don't fit neatly into corporate strategy.

FAQ

What inspired Katsuya Eguchi to create Animal Crossing?

Eguchi was inspired by his personal experience of loneliness after moving from Chiba to Kyoto in 1986 to work at Nintendo. He was separated from his family and friends and wondered if there was a way to recreate that feeling of connection through a game. This concept of a "communication game" became the foundation for what would eventually become Animal Crossing.

What was the 64DD and why was it important to Animal Crossing's development?

The 64DD was Nintendo's disk-writing add-on for the Nintendo 64 console, featuring 64 MB of rewritable storage, internet connectivity, and a real-time 24-hour clock. This real-time clock was crucial for Eguchi's vision because it allowed a game to operate continuously, with changes happening whether or not the player was actively playing. Though the 64DD failed commercially, selling only about 15,000 units, it was the hardware that made Animal Crossing technically feasible.

Why did Animal Crossing have to be redesigned for the N64 cartridge format?

When the 64DD was discontinued in February 2001, the games in development for it had to be adapted to other hardware. Animal Forest was reworked to function on the N64 cartridge, which meant losing some features like robust internet connectivity that the disk format had promised. Despite these limitations, the core design philosophy—a game operating on a real-time clock with a persistent world—remained intact.

How does the real-time clock system work in Animal Crossing?

The real-time clock allows the game to continue operating even when the console is off. This means different times of day feature different NPCs and activities, different seasons bring different flora and fauna, and the village changes between player sessions. Players must return regularly across different times and seasons to experience all the game's content, making it impossible to "complete" the game in a single session.

What makes Tom Nook's character work so well in Animal Crossing?

Tom Nook is a capitalist character who offers you a home mortgage, but he never threatens or punishes the player. The debt is psychological pressure rather than mechanical punishment, creating a gentle incentive to earn money through activities like fishing and catching insects. This design allows players to engage with economic systems in a non-threatening way while maintaining voluntary participation.

How did Animal Crossing evolve from the N64 original to become a global phenomenon?

Animal Crossing was reworked and released on the Game Cube in 2002, which included internet connectivity and was released globally in North America and Europe. This expanded audience and demonstrated appeal to casual and adult players. By the time Animal Crossing: New Horizons released for the Nintendo Switch in March 2020, the franchise had become one of Nintendo's most valuable properties, especially resonating during global lockdowns.

Why is Animal Crossing considered innovative game design?

Animal Crossing was innovative for prioritizing emotional experience over mechanical challenge, creating a game with no fail states, no competition, and no required objectives. It pioneered the concept of a persistent world that continues without player input, influenced what would become the "cozy game" genre, and demonstrated that games could be about existence and relaxation rather than achievement.

Conclusion: The Persistence of Vision

Animal Crossing's journey from one man's loneliness to a global phenomenon is not a story about triumph over adversity, exactly. It's a story about what happens when you hold onto a vision even as the world around you changes.

Katsuya Eguchi had an idea in 1986. He spent fifteen years thinking about it before the technology existed to make it real. When that technology—the 64DD—failed spectacularly, he didn't abandon the vision. He adapted it. When it succeeded beyond anyone's expectations, he didn't dilute it with sequels and spin-offs that chased trends. He kept refining it, kept returning to the core emotional idea.

Today, Animal Crossing is one of Nintendo's most valuable franchises. It's generated billions in revenue. It's influenced game design across the industry. It's created a community of players who maintain islands, share designs, and visit each other's spaces in ways that Eguchi probably never imagined.

But the core remains unchanged. You arrive as a stranger in a town. You build a life. You check in regularly. The world continues even when you're not looking. Your neighbors notice when you're absent. The seasons change. The time of day changes. Small things accumulate into something that feels, somehow, meaningful.

This is what Eguchi was trying to create when he moved away from his family in 1986. A space where you could feel connected to a community, even across distance. A game where showing up mattered, not because you'd accomplished something, but because you'd chosen to return.

That idea—simple, genuine, rooted in real human need—has proven to be more durable than any hardware, more valuable than any cutting-edge technology, more important than any corporate strategy.

In 2025, when everything in games is fighting for your attention, when everything is trying to maximize engagement and time-on-platform, Animal Crossing remains quietly revolutionary. It's a game about rest. About showing up. About building something that reflects who you are, not who you're trying to be.

It started as a dungeon crawler that never was. It became a life sim that fundamentally changed what games could be. And it did all of that by staying true to one man's understanding of loneliness, connection, and the small, ordinary magic of showing up for a place you care about.

That's the real lesson of Animal Crossing's origin story. Vision persists. Authenticity resonates. And sometimes the most revolutionary thing you can do is ask: what if a game was just about existing in a place?

Everything else followed from there.

Key Takeaways

- Animal Crossing was born from Katsuya Eguchi's personal loneliness after moving to Kyoto in 1986, inspiring him to create a 'communication game' about connection across distance

- The 64DD's real-time clock was essential technology that allowed the game to operate continuously, with events happening whether or not the player was actively playing

- Despite the 64DD's catastrophic commercial failure (only 15,000 units sold), Animal Forest was successfully adapted to the N64 cartridge and released as the console's final game in 2001

- Animal Crossing pioneered a revolutionary design philosophy focused on existence and relaxation rather than achievement, becoming the spiritual ancestor of the modern 'cozy game' movement

- The franchise's success demonstrates that authentic emotional vision and genuine design philosophy can persist through hardware failures and technical constraints

Related Articles

- Sea of Remnants: Building an Ambitious Open-World Pirate RPG [2025]

- Best Nintendo Switch Online Hidden Gems You're Missing [2025]

- Nintendo Switch: The Console That Changed Gaming Forever [2025]

- Steam Early Access Release Dates: How Developers Benefit [2025]

- GOG Galaxy is Getting Native Linux Support. Here's What it Means [2025]

- Analogue 3D N64 Prototype Colors: Complete Guide to Atomic Purple & More [2025]

![How Animal Crossing Started as a Dungeon Crawler: Nintendo's Hidden History [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-animal-crossing-started-as-a-dungeon-crawler-nintendo-s-/image-1-1770646338226.jpg)