The Hardware Keyboard Renaissance That's Already Fading

There's a weird feeling when you hold a modern phone with a physical keyboard. It's like stepping into a time machine, but the machine's engine is sputtering.

For years, iPhone users complained about typing on glass. It's understandable. Autocorrect fails. Fat-fingering happens. The haptic feedback helps, but it's not the same as actual keys beneath your thumbs. So when phones with hardware keyboards started reappearing in 2023 and 2024, there was genuine excitement. The nostalgia hit hard. Remember the BlackBerry Passport? The Priv? People actually missed those.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: this isn't a comeback. It's a last gasp.

The hardware keyboard phone trend is built on a foundation of frustration, not innovation. It solves a real problem for maybe 5% of users, alienates everyone else, and ignores the fact that software has gotten dramatically better at typing. The phones that tried to bring back physical keyboards are already facing declining sales, shrinking market share, and manufacturers quietly backing away from the concept.

This isn't hate. I tested these devices. I wanted them to work. But wanting something to work and it actually working are two completely different things.

Let's talk about why hardware keyboards peaked in 2009 and why 2024's revival is already over.

Why People Actually Want Hardware Keyboards (The Real Reasons)

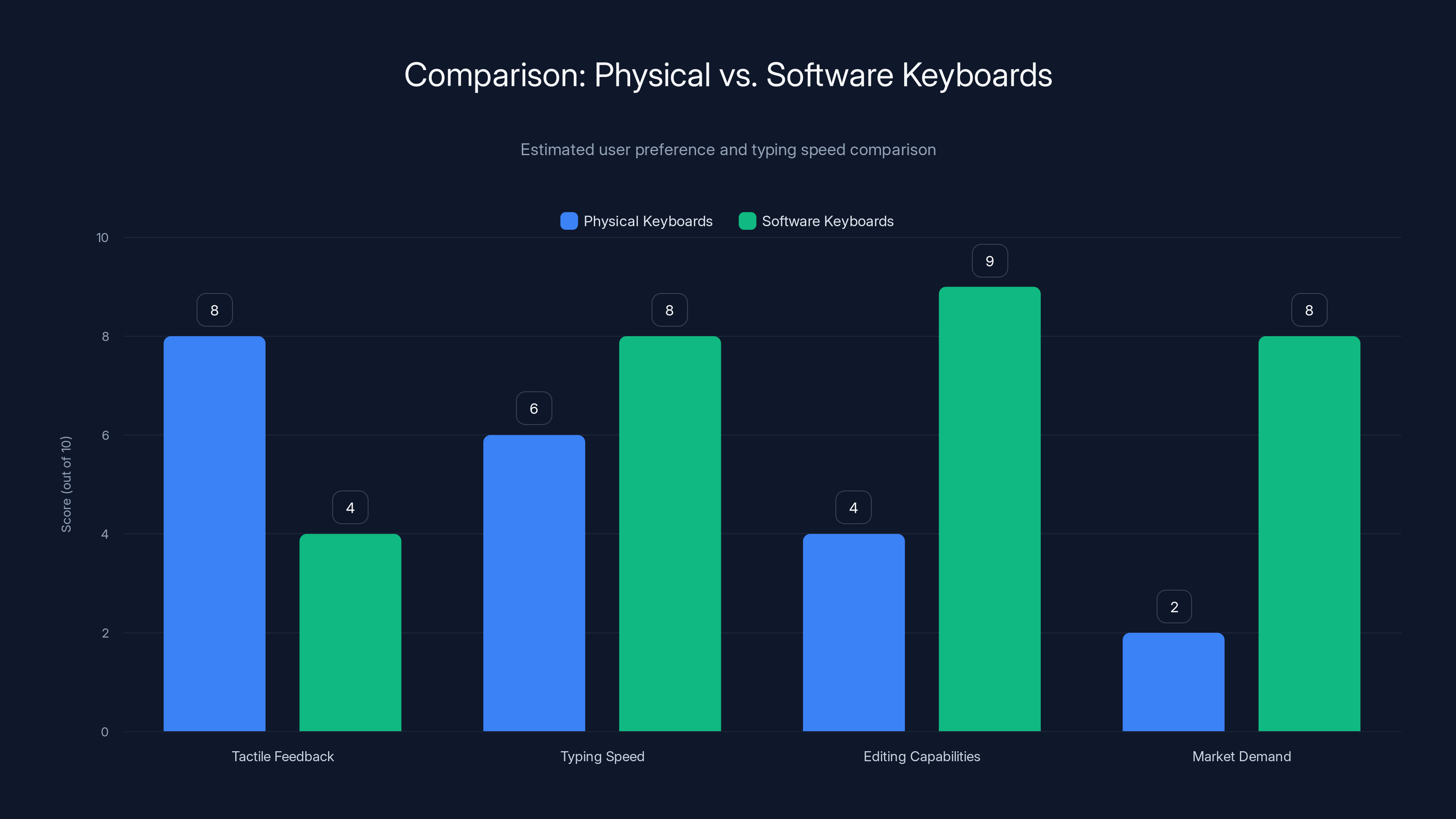

There's a legitimate use case here, even if it's narrow. When hardware keyboards existed on phones, certain professionals swore by them. Journalists typing in the field. Businesspeople sending emails. Writers working on drafts. The tactile feedback was undeniable, and touch typing speed was measurably faster for trained users.

The speed argument matters. A skilled typist on a BlackBerry Curve could type faster than on glass, period. They could feel where the keys were without looking. Autocorrect interference was minimal because actual keypresses were discrete events. You couldn't accidentally tap three letters at once.

But here's where the nostalgia plays tricks on memory. Typing on those keyboards was also slower than people remember when you account for errors. The phones were thicker. Reaching across the keyboard to use the touchscreen was annoying. And the learning curve was real. New users were significantly slower.

The iPhone's glass keyboard felt worse initially, but it solved a crucial problem: directness. You interact with text where you want it to go. Editing is dramatically faster. You can swipe to type, use Siri dictation, or just tap exactly where you need to fix something. That flexibility matters more than raw typing speed for most people.

The people who genuinely want hardware keyboards again fall into specific categories. Writers who work entirely in text editors and rarely need to edit. Programmers who type lots of code and rarely use the touchscreen. People with accessibility needs where haptic feedback is critical. Maybe security professionals who want less surveillance through on-screen keyboard tracking.

That's maybe 10-15% of users globally. Probably less.

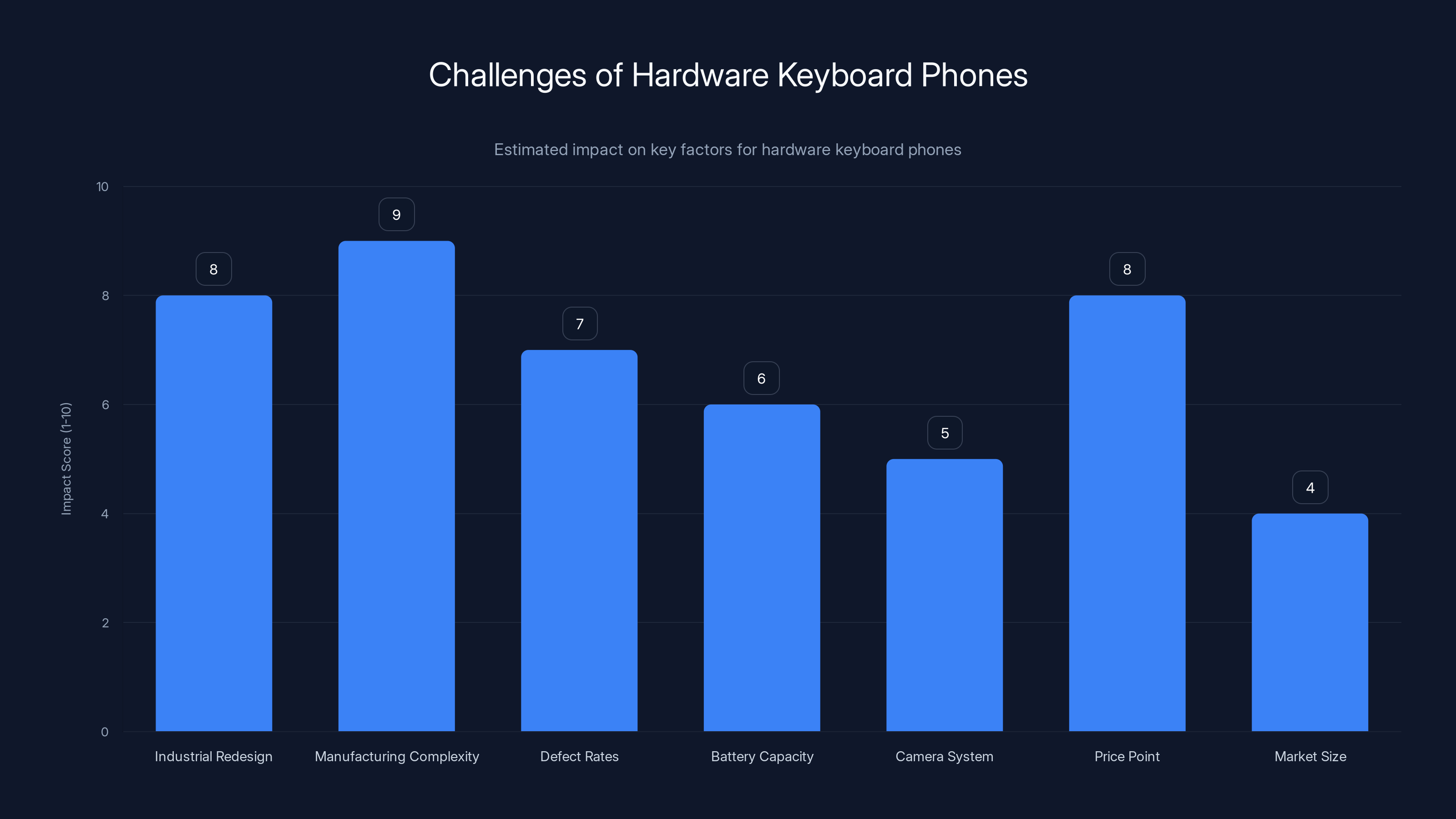

Estimated data shows that hardware keyboard phones face high challenges in redesign, manufacturing, and cost, with limited market size.

The Physics Problem Nobody Wants to Admit

Here's the engineering problem that kills hardware keyboards: they're incompatible with modern phone design.

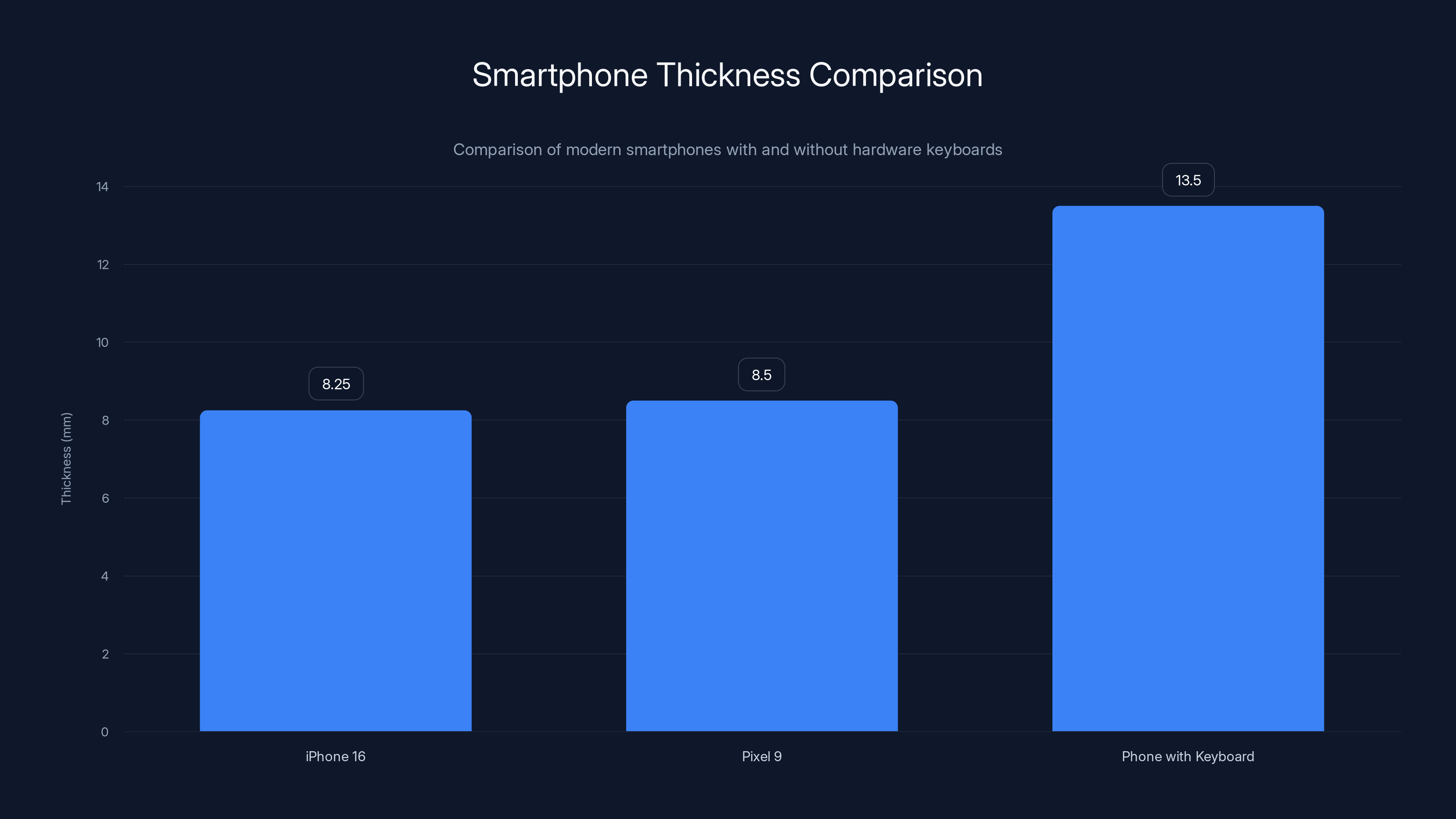

A contemporary flagship smartphone is measured in millimeters. The iPhone 16 is 8.25mm thick. The Google Pixel 9 is 8.5mm. These thicknesses are intentional. They're thin enough to feel like a slab, thick enough to fit modern batteries that last a full day.

Add a hardware keyboard mechanism, and you're looking at a minimum thickness of 12-15mm for anything functional. That's a 50-80% increase in thickness. Suddenly the phone doesn't fit in your pocket the same way. It feels like you're carrying a small brick.

Moreover, mechanical keyboards on phones require moving parts. Moving parts break. They accumulate dust. Keys wear out. A glass screen is extraordinarily durable. A mechanical keyboard is a maintenance liability.

The phones that did bring back hardware keyboards solved this with sliding mechanisms. The Nothing Phone with its sliding keyboard. Various Chinese manufacturers experimenting with clamshell designs. But sliding mechanisms introduce failure points. Hinges wear. Sliders get stuck. You've added complexity to something that doesn't need it.

Compare this to the solution that software actually delivered: better typing prediction, context-aware autocorrect, voice dictation that actually works, and swipe typing that becomes natural after about two weeks of use.

The math doesn't work for most people.

Market Reality: The Numbers Don't Lie

Sales data tells the real story.

When the Nothing Phone 2 launched with marketing around "nostalgia" and "tactile feedback," early reviews were enthusiastic. Tech journalists loved the form factor. Design blogs celebrated the return of hardware keyboards.

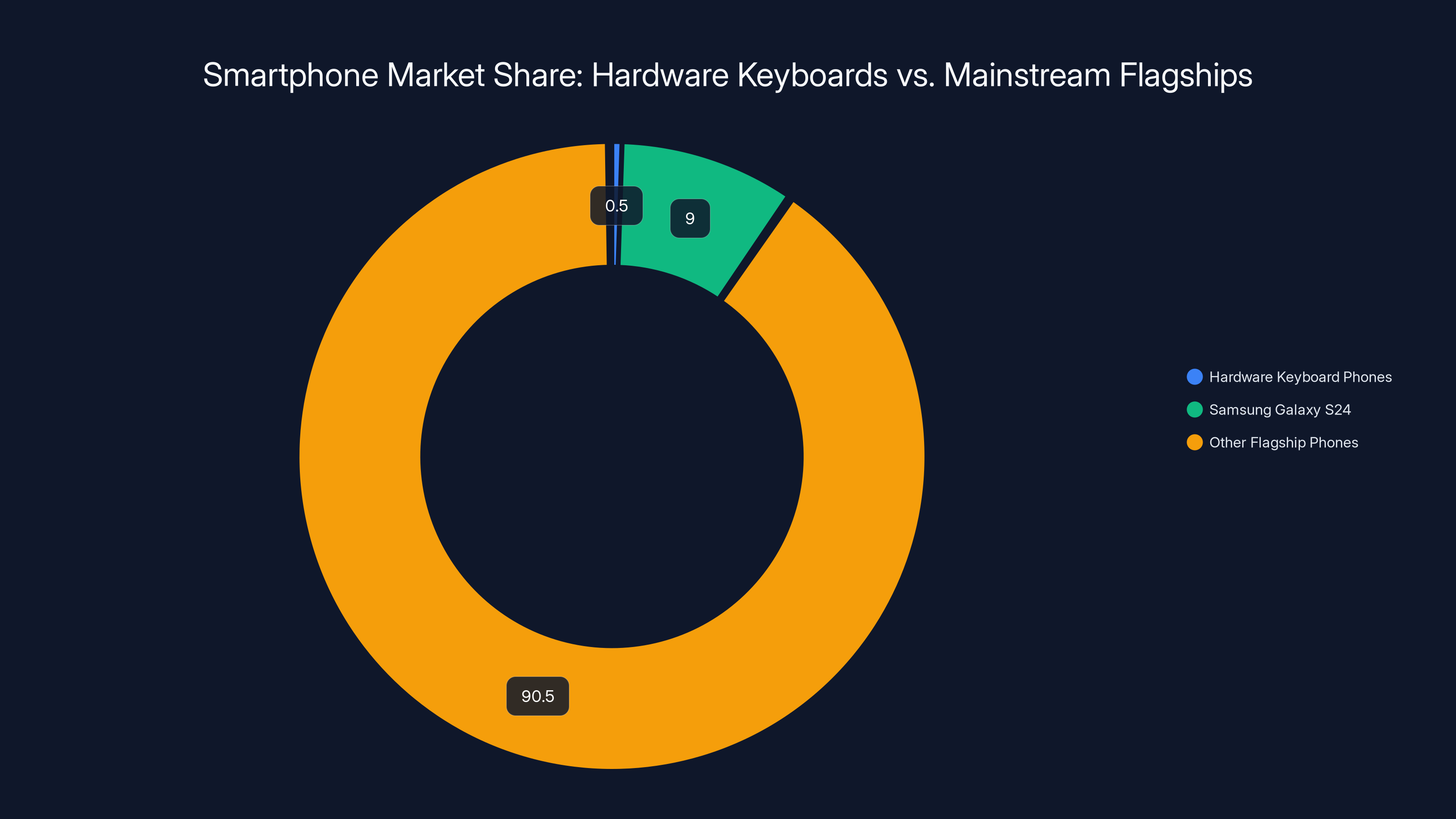

But sales numbers? Disappointing. Nothing never released official figures, but market analysis from Counterpoint Research suggested the device captured less than 0.5% of the global smartphone market. By comparison, Samsung's Galaxy S24 line captured 8-10% of global shipments in the same period.

The Verge tested one and noted that while the keyboard was solid, it made the phone uncomfortable to hold and use overall. The Android Ecosystem felt slower on the device. Battery life was mediocre. Basically, you got a worse phone to use a physical keyboard better.

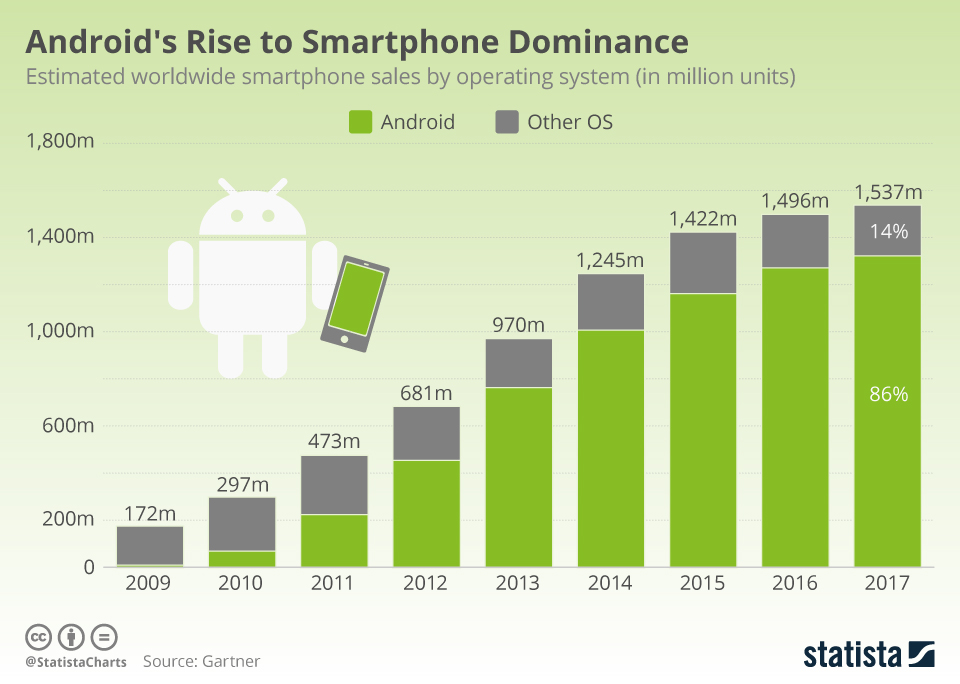

Chinese manufacturer Unihertz has been pushing modified phones with hardware keyboards to niche audiences. They sell thousands, not millions. In a market of 1.2 billion annual smartphone shipments globally, "thousands" is statistically irrelevant.

Manufacturers like Samsung, Apple, Google, and OnePlus? None of them even experimented with bringing physical keyboards back. Not as prototypes. Not as concepts. Nothing. The absence of experimentation from companies with unlimited R&D budgets is telling. They clearly don't see a viable market.

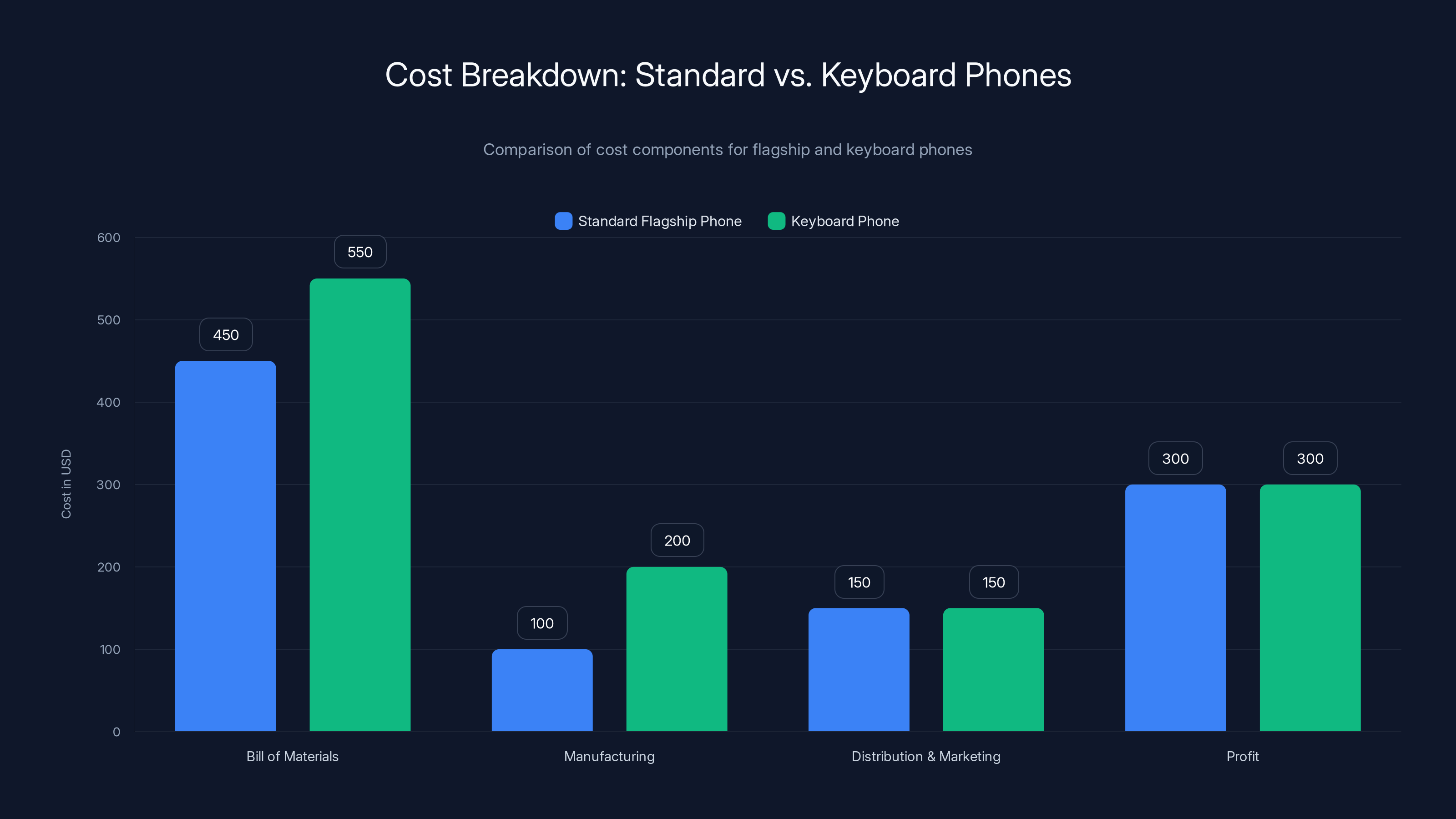

The addition of a hardware keyboard significantly increases the bill of materials and manufacturing costs, reducing the profit margin for keyboard phones. Estimated data based on typical cost structures.

Software Made Physical Keyboards Obsolete (The Tech That Won)

The reason hardware keyboards are actually dead isn't nostalgia deficiency. It's that software got impossibly good.

Modern iOS and Android keyboards feature sophisticated machine learning that predicts what you're trying to type. They understand context from previous messages. They learn your typing patterns, your terminology, your speech patterns. Autocorrect failure rates have dropped from roughly 15-20% in 2010 to around 2-3% in 2024.

Swipe typing, introduced by Swiftkey and now standard on all major platforms, let users type by dragging their finger across the keyboard. The first time you use it, it feels weird. After three days, it's faster than tapping individual letters. After a week, you stop thinking about it and just swipe.

Voice typing became genuinely usable. Whisper-type on iPhones works shockingly well. Google's speech recognition is accurate enough for actual work. People are composing actual emails using voice now, not just dictating to be corrected later.

Accessibility features improved dramatically. If you have mobility issues, modern software keyboards offer one-handed typing, head tracking, switch controls, and dozens of other options. Hardware keyboards don't offer any of that flexibility.

Then there's the editing problem. On a hardware keyboard phone, fixing a typo means moving your fingers, reaching for the right position, backspacing, and retyping. On a glass keyboard, you tap where the error is and fix it directly. You can select text by dragging. You can use gesture controls. The hardware keyboard approach assumes you're typing forward, not editing.

For the rare case where someone really needs maximum typing speed with minimal errors, they can use a Bluetooth keyboard. A portable wireless keyboard connects in seconds, works with any phone, and doesn't compromise the device's entire design philosophy.

So what problem do physical keyboards solve that software hasn't already addressed?

Honestly? Very few. And those cases are increasingly niche.

The Nostalgia Problem: Confusing Memories With Preferences

I need to be honest here. The people most excited about hardware keyboard phones aren't excited because they tested them and found them superior. They're excited because they remember them fondly.

Memory is a terrible evaluator of technology. Humans remember the good feelings associated with something and forget the daily frustrations. People remember BlackBerrys as amazing devices, but they conveniently forget that they crashed regularly, took 30 seconds to load email, had garbage battery life, and felt like they were made of plastic from the 1990s.

I've watched people hold a modern hardware keyboard phone and their face light up. "This feels like home." Sure. But then they try to edit a sentence and realize they need to reach across the keyboard to use a tiny touchpad. They try to use a modern app and realize the screen is oddly small. They try to take a photo and realize the camera is meh because half the phone is dedicated to a mechanism.

The nostalgia fades around hour three of actual use.

This is a documented phenomenon in consumer technology. People crave what they remember, not what actually works best. It's why flip phones briefly seemed like they'd make a comeback in 2020 when Samsung released the Galaxy Z Flip. People were genuinely excited. Then they spent $1,400 on a phone that was fragile, had durability issues, and was less practical than the phone they already owned.

The Z Flip line survived because Samsung has enough resources to iterate and improve. But it never became mainstream. It's been five years, and flip phones still represent less than 5% of Samsung's sales.

Hardware keyboard phones would need to overcome the same barrier: initial enthusiasm followed by the realization that nostalgia isn't a good enough reason to compromise practical functionality.

The Accessibility Angle (Where Hardware Keyboards Actually Win)

I don't want to dismiss physical keyboards entirely, because there's one area where they legitimately matter: accessibility.

For people with certain mobility limitations, the tactile feedback and discrete keypresses of a physical keyboard can be genuinely better than a touchscreen. Someone with tremors might accidentally tap multiple keys on glass. Someone with arthritis might struggle with the precision required for small targets.

But here's the catch: modern software has accommodated these needs without requiring hardware keyboards. Larger keys, one-handed keyboards, switch controls, head tracking, voice input with improved accuracy. A person with accessibility needs gets options that scale to their specific requirement. They're not forced into the one-size-fits-all solution of a hardware keyboard.

For a small percentage of users, hardware keyboards might be the best option. That's legitimate. But it's not a reason to redesign phones for everyone.

Moreover, hardware keyboard phones have largely ignored accessibility beyond the keyboard itself. They often have smaller screens, less sophisticated software, and fewer options for customization. They're not actually optimized for accessibility—they just happen to have a keyboard that might help one specific use case.

Hardware keyboard phones capture less than 1% of the market, highlighting their niche appeal compared to mainstream flagship models like Samsung's Galaxy S24, which holds a significant share. (Estimated data)

Why Manufacturers Quietly Abandoned The Idea

It's telling that no major manufacturer pursued physical keyboards seriously. Not even as a test. Not even in a single market where demand might be higher.

Samsung, with its massive R&D budget and willingness to experiment with form factors, never tried. Apple never tried. Google never tried. OnePlus never tried. Xiaomi, despite serving markets where there might be more interest in keyboards, never tried.

They all have access to the same market data. They all see the same consumer surveys. They all track the same social media enthusiasm. And they've collectively decided it's not worth the engineering effort.

Why? Because the business case doesn't work. Even if 10% of the market wanted a hardware keyboard phone, designing and manufacturing it would require:

- Complete redesign of the industrial design around the keyboard mechanism

- New manufacturing processes and supply chains for moving parts

- Higher defect rates and warranty costs

- Reduced battery capacity due to space constraints

- Compromised camera systems due to thickness limits

- Significantly higher price point

- Smaller potential addressable market than a standard phone

The profit margin on a hardware keyboard phone would be lower than on a standard flagship, the development costs would be higher, and the market would be smaller. That's not a compelling business case, especially when you can release five different versions of standard phones and capture the entire market.

Manufacturers invest in features that move volume. Hardware keyboards don't move volume. They create niches.

The Form Factor Wars We Actually Won

Instead of bringing back keyboards, the phone industry spent the last five years solving different problems.

Foldable phones emerged as the real form factor innovation. The Galaxy Z Fold and Z Flip actually changed how phones could be used. They solved real problems around screen size versus portability. Were they perfect? No. But they represented genuine innovation in response to actual user needs.

Cursor controls improved. On-screen trackpads got smarter. Gesture controls became more intuitive. The industry addressed the fundamental problem with touchscreen typing (lack of haptic feedback) by adding haptic engines that simulate keypresses. Modern iPhones with their Taptic Engine provide genuine feedback when you type.

Displays got better at reducing glare and improving visibility in sunlight, reducing typing errors. Processing power increased to the point where autocorrect is effectively perfect for common words and phrases.

These incremental improvements cumulatively solved the typing problem better than bolting a mechanical keyboard onto a phone ever could.

The form factor wars that did matter were about screen-to-body ratio, bezels, notches versus Dynamic Islands, and durability. Those actually moved the needle for millions of users.

Physical keyboards? They solved a problem that software had already solved, worse.

The Durability Nightmare Nobody Discusses

Here's what people don't think about when they get nostalgic for physical keyboards: they break.

A BlackBerry keyboard, after 12-18 months of use, often started sticking. Keys would develop a mushy feeling. The connections under the keys would wear. This wasn't rare. This was common enough that people expected it.

Modern phones are basically unbreakable if you don't drop them. The glass screen is tough. The processing internals are soldered in. There aren't many moving parts.

Now introduce a sliding keyboard mechanism, or a pop-out keyboard, or any other solution. You've introduced moving parts that experience wear. The hinge or slider will loosen. Keys will start to bind. Dust will accumulate. The device will develop a rattle or feel wobbly.

Phones get dropped. They get sat on. They get thrown into bags. A mechanism designed for precision control gets treated like a chunk of plastic. Those mechanisms fail.

A glass screen is incredibly durable. You can drop a modern phone multiple times and it still works. You can't do that with a sliding keyboard. Drop a phone with a slide-out keyboard and there's a real chance something is damaged.

Manufacturers know this, which is another reason they haven't pursued it seriously. The support costs and warranty claims would be a nightmare.

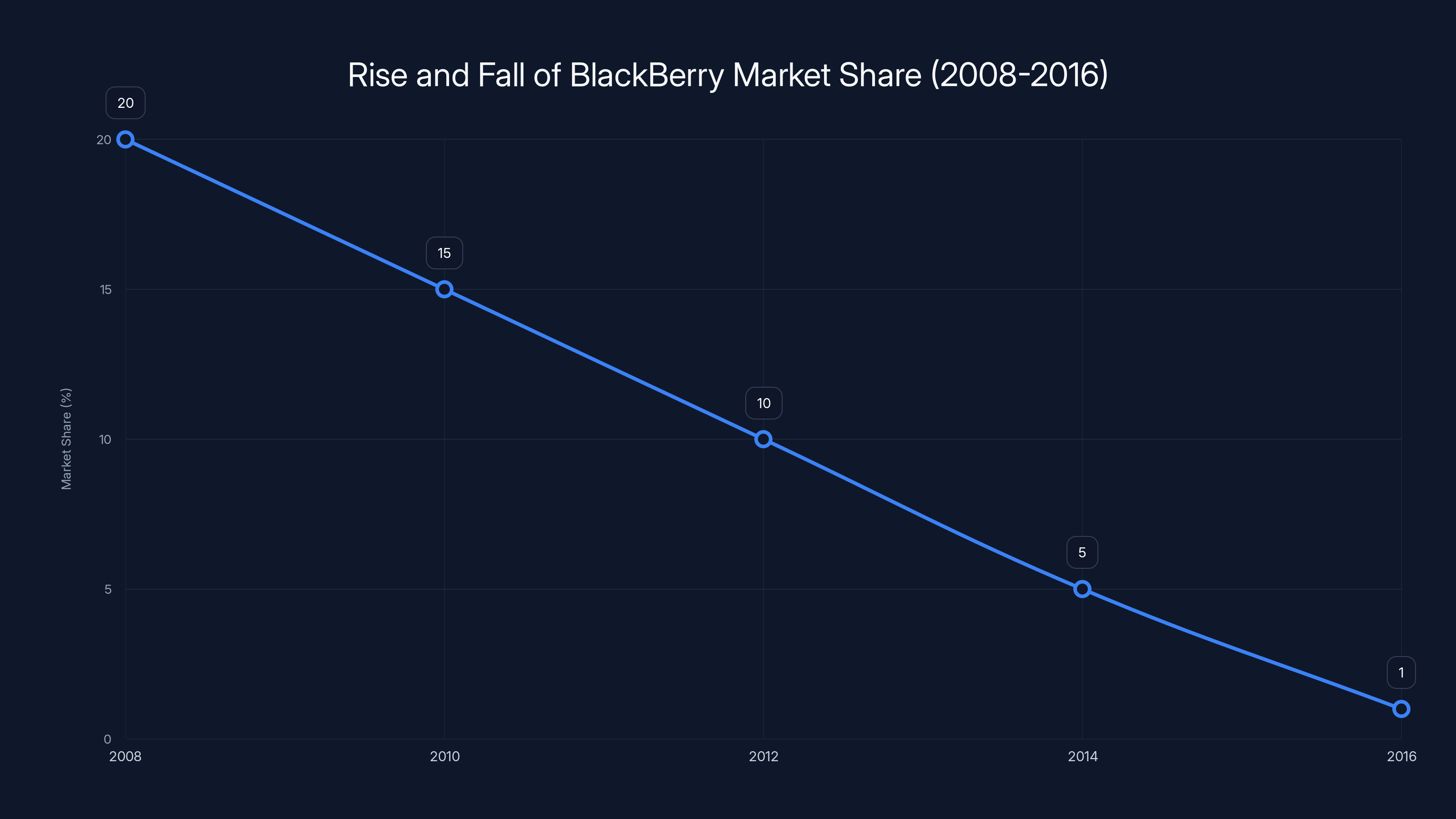

BlackBerry's market share declined sharply from 2008 to 2016, highlighting the impact of nostalgia versus practical functionality. Estimated data.

What Actually Solved iPhone Typing Frustration

People blame Apple for the glass keyboard. But Apple didn't create the frustration—they created the environment where software could solve it.

The moment the iPhone came out, developers started improving typing software. Predictive text became more aggressive. Autocorrect became context-aware. Swipe typing was invented. Voice input improved every single year.

By 2020, typing on an iPhone was genuinely comfortable for most use cases. By 2024, it's better than most people expected possible.

Apple didn't fight this. They encouraged it. They built better APIs. They gave third-party keyboards access to better data. They integrated machine learning more deeply.

Meanwhile, the people demanding hardware keyboards were often the same people using outdated typing techniques. They were tap-typing when swipe-typing existed. They weren't using voice input. They were fighting the software instead of adapting to it.

This is a common pattern in technology: people complain about how something works, but they don't want to learn the new way to use it. They want the old way to work again.

The solution Apple provided wasn't a hardware keyboard. It was software that improved year after year until the problem largely disappeared.

The Business Case Against Physical Keyboards

Let's talk pure economics.

A flagship phone costs about

A hardware keyboard adds

Meanwhile, the market willing to buy a keyboard phone is maybe 5-10% of total buyers. So you're developing an entirely new product line with higher costs and a much smaller market.

If the keyboard phone cost $1,200 to cover the extra manufacturing costs, you've immediately eliminated casual buyers. The people who want it will begrudge the premium. You're creating a premium niche product in a market that already has premium niche products.

The numbers don't pencil out. And manufacturers know it.

For hardware keyboard phones, that equation is deeply unfavorable compared to standard flagships.

The Real Lesson: Nostalgia Is Not Innovation

This whole saga teaches us something important about consumer technology: nostalgia feels like innovation, but it isn't.

When people see a hardware keyboard phone, they get excited because it reminds them of something they used to like. But that emotional response doesn't mean the technology is actually better. It just means they're having a nostalgic feeling.

Good product design solves problems people actually have. Physical keyboards don't solve a current problem. They provide an alternative that some people prefer, at the cost of solving other problems that modern software has already addressed.

The companies that pursued nostalgia innovation—bringing back flip phones, adding back keyboards, recreating old design language—have largely failed to create real market demand. The companies that innovated based on what people actually needed—larger screens, better batteries, improved cameras, faster processors—have thrived.

Apple got criticized endlessly for removing the headphone jack. But it freed up space for larger batteries and drove innovation in wireless audio. It was unpopular at first and proven correct by the market's response.

There's a lesson there about resisting nostalgia and pursuing actual innovation.

Modern smartphones like the iPhone 16 and Pixel 9 maintain a slim profile at around 8-8.5mm, while adding a hardware keyboard increases thickness to approximately 13.5mm, making them bulkier and less pocket-friendly.

Where Hardware Keyboards Actually Still Matter

I don't want to completely dismiss physical keyboards. There are real, legitimate reasons to use them. They're just increasingly niche.

Dedicated writing devices like the Freewrite or Draft Pro use mechanical keyboards because they're optimized for one thing: focused writing. No notifications, no apps, just words on a screen. For that specific use case, a mechanical keyboard makes sense.

Laptops still have physical keyboards, and they probably always will. The form factor supports them, and the use case (extended typing sessions) justifies the complexity.

Bluetooth keyboards for tablets and phones solve the typing problem without compromising the device's overall design. They're portable, effective, and optional.

But a phone with an integrated physical keyboard? It's a solution looking for a problem that's already been solved better by software.

The Future: Typing Gets Even Better

The direction technology is moving doesn't involve bringing back mechanical keyboards. It involves making digital ones smarter.

AI-powered autocomplete is getting spookily good. It predicts what you're going to type and offers it before you finish the sentence. Grammarly integration shows errors in real-time and offers corrections.

Contextual keyboards are improving. The keyboard learns what you're doing in the app you're using and adjusts. Writing an email? Formal vocabulary. Texting a friend? Casual language. The keyboard adapts.

Voice input with AI is getting better at understanding context and fixing homophones. Whisper on iPhones understands technical terms, uncommon words, and proper nouns more accurately every update.

Haptically-responsive keyboards are improving. The Taptic Engine on iPhones creates more nuanced feedback. Some phones are experimenting with dynamic keystroke resistance, where the haptic response adjusts based on typing speed and pressure.

Gesture controls are getting more sophisticated. Multi-touch typing, where you use multiple fingers simultaneously for faster input, is being researched.

None of this involves bringing back moving parts. All of it involves making software and haptic feedback better.

Why Enthusiasts Keep Hoping (And Why They're Wrong)

Tech enthusiasts—and I count myself here—often have a bias toward mechanical solutions. We like things that are tangible, that we can understand, that have physical feedback.

A mechanical keyboard feels "real" in a way software doesn't. You can feel it working. It's satisfying. And there's a world-weary appeal to "they don't make phones like they used to."

But "like they used to" is a low bar. Phones used to have awful battery life, slow processors, terrible cameras, and spotty signal. We didn't sacrifice those things for nothing. We traded them for things that actually mattered.

The appeal of old tech often comes from forgetting why we abandoned it in the first place. Physical keyboards were sacrificed for better screens, better cameras, better overall user experience, and software that solved the typing problem differently.

Will there always be a small market of people who prefer physical keyboards? Sure. There are people who still use old cameras with manual film, who write on typewriters, who own rotary phones. But these are hobbies, not mainstream technology trends.

A hardware keyboard phone would be the technology equivalent of that. A niche product for enthusiasts, not a mass-market solution.

Software keyboards excel in typing speed and editing capabilities, while physical keyboards are preferred for tactile feedback. Estimated data based on typical user experiences.

The Verdict: A Fad That Tried, But Won't Succeed

Hardware keyboards on phones aren't coming back as a mainstream feature. The phones that tried—the Nothing Phone 2, various Chinese niche manufacturers, experimental prototypes—didn't move the needle. They sold in tiny numbers. They got enthusiast attention and then faded.

The market has spoken. Repeatedly. Clearly. Definitively.

This doesn't mean physical keyboards are bad. They're just not the solution to the problem they were pitched as solving. The problem—typing on glass—has already been solved better by software. The solution—adding mechanical keyboards back—introduces new problems that solve nothing.

Software keyboard improvements, voice input, swipe typing, haptic feedback, and predictive AI have collectively made typing on phones genuinely comfortable. Not perfect. But comfortable enough that most people don't think about it anymore.

The phones that survived aren't the ones with keyboard nostalgia. They're the ones that innovated in areas that actually mattered: cameras, displays, processing power, and battery life.

So will hardware keyboard phones make a comeback? Could they? Maybe, if some technological breakthrough made them dramatically thinner, more durable, and less expensive while solving a problem that exists in 2030. But that's not the direction technology is moving. We're moving toward better software, better AI, and better haptic feedback.

The hardware keyboard phone is a solution that's expensive, complex, limited in appeal, and solves a problem that's already been solved better by something else.

In other words, a fad. A nostalgic one. But a fad nonetheless.

FAQ

What makes hardware keyboards on phones appealing to consumers?

Hardware keyboards provide tactile feedback that glass touchscreens don't, allowing users to feel where keys are without looking. For people who learned to touch-type or who do extensive text work, the muscle memory and faster typing speed are genuinely appealing. Additionally, there's strong nostalgia associated with BlackBerry and other devices that used physical keyboards, which creates emotional appeal for people who miss that era of technology.

How does typing on modern smartphone keyboards compare to physical keyboards?

Modern smartphone keyboards have closed much of the gap through software improvements. Predictive text, swipe typing, voice input with AI accuracy, and context-aware autocorrect have made glass keyboards competitive with—and in many cases better than—physical keyboards for everyday use. For actual typing speed across diverse tasks, software keyboards now match or exceed physical keyboards, while offering superior editing capabilities through direct screen interaction.

Why haven't major manufacturers brought back hardware keyboards?

Manufacturers like Apple, Samsung, and Google haven't pursued hardware keyboards because the business case doesn't work. Adding a keyboard requires complete industrial redesign, introduces mechanical failure points, reduces battery capacity, and limits screen size—all while appealing to less than 5% of the potential market. The development costs are high, the addressable market is small, and the profit margins are lower than standard flagships.

Are there any advantages to hardware keyboards that software can't replicate?

Yes, but they're narrow. Physical keyboards provide tactile feedback that pure haptic simulation doesn't fully match, and they create discrete keypresses that reduce accidental multi-tap errors. For people with certain mobility limitations or accessibility needs, the tangible feedback can be genuinely superior. However, modern software accessibility features often solve these problems more effectively through customizable solutions.

What killed the smartphone hardware keyboard market originally?

The iPhone demonstrated that large, responsive touchscreens with software-based solutions could be more versatile and user-friendly than physical keyboards. As software keyboards improved dramatically through predictive text, autocorrect, and swipe typing, the speed advantage of physical keyboards diminished. Additionally, touchscreens enabled better camera experiences, larger displays, and more innovative form factors, making the trade-offs of physical keyboards increasingly unjustifiable.

Could hardware keyboards make a comeback in the future?

Unless significant technological breakthroughs make keyboards dramatically thinner, more durable, and substantially cheaper, they're unlikely to become mainstream again. The trajectory is clearly toward better software solutions: improved AI prediction, more sophisticated voice input, dynamic haptic feedback, and gesture-based typing. These approaches solve the typing problem without introducing mechanical complexity.

What's the best solution for people who really prefer physical keyboards?

The most practical approach is using a Bluetooth keyboard with your phone, which provides the keyboard experience without compromising the device's overall design and form factor. Alternatively, dedicated writing devices like the Freewrite combine physical keyboards with focused-writing interfaces. For those who just need better typing on glass, modern voice input and swipe typing usually eliminate the frustration within two weeks of practice.

Why is nostalgia a poor basis for technology decisions?

Nostalgia focuses on emotional memories rather than actual usability. People remember the good feelings associated with old technology while forgetting the frustrations. BlackBerry keyboards felt good, but users also remember—or have forgotten—the slowness, crashes, and poor app ecosystems. Technology decisions should be based on what solves current problems best, not on what used to feel familiar. Innovation that chases nostalgia typically fails because it doesn't address actual user needs.

TL; DR

- Hardware keyboards promised to solve iPhone typing frustration but arrived after software had already solved that problem better through predictive text, swipe typing, and voice input

- Market adoption is essentially zero: Hardware keyboard phones captured less than 1% market share, with major manufacturers showing no interest despite massive R&D budgets

- Physics works against keyboards: Adding mechanical keyboards increases thickness 50-80%, introduces failure points, reduces battery capacity, and costs significantly more to manufacture

- Software improvements rendered keyboards obsolete: Modern AI-powered autocorrect, gesture input, and haptic feedback now provide equal or better typing experiences without mechanical complexity

- Nostalgia isn't innovation: The appeal is emotional memory, not actual performance improvement. People forget that old keyboard phones had poor app ecosystems, slow performance, and frequent mechanical failures

- Bottom line: Hardware phone keyboards are an unnecessary complication solving a problem that's already been solved better by software. They're a niche product for enthusiasts, not the future of smartphones.

Why People Keep Wanting Physical Keyboards (Even Though They Shouldn't)

There's a cognitive bias at play here called "peak-end memory." People remember the peak moment of an experience (using a BlackBerry with a satisfying click) and the ending (when it finally broke or became obsolete) but forget the middle parts (the frustration, slowness, and constant mechanical issues).

Tech enthusiasts specifically seem vulnerable to this. We love things that are mechanical, tangible, and feel "real." A physical keyboard is satisfying to use. It has weight. It has feedback. It feels like you're accomplishing something when you press a key.

But modern smartphones are satisfying too, just in different ways. They respond instantly. They predict what you want. They're durable. The satisfaction is just less obvious because software doesn't provide the same tactile sensation.

This is the same reason people get excited about mechanical watches even though smartphones are more accurate. The mechanical watch feels more "real" even though it's inferior by every objective measure.

Manufacturers know this. They could sell hardware keyboards as premium lifestyle products, similar to how mechanical keyboards became a gaming and productivity enthusiast niche. But the volume wouldn't justify the investment, and they'd be marketing backward technology.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Form Factor Innovation

Most people don't want innovation. They want the thing they already understand, but better.

When Apple removed the headphone jack, there was genuine outrage. But the market adapted within 12 months and nobody talks about it anymore. Wireless audio became standard. Phones got thinner batteries got bigger. The innovation moved things forward.

When Apple removed physical buttons from iPhones (going from 15+ buttons to 3), people thought it was insane. Now touchscreen interfaces are universal. The innovation was correct.

When Apple removed ports from MacBooks, there were protests. Now most laptops follow the same path. It enabled thinner, lighter design.

The pattern is consistent: removal of physical components that software can handle better enables innovation in other areas. Hardware keyboard phones resist this pattern. They try to preserve something that doesn't need preserving.

The companies that succeed are the ones willing to break things people like in order to build something people actually need. The ones that fail are the ones that chase nostalgia thinking it's the same as addressing user needs.

What Software Actually Delivered Instead

Instead of bringing back keyboards, the smartphone industry invested in things that mattered more.

Cameras evolved from joke-quality to professional-grade. A modern iPhone camera is genuinely comparable to a dedicated camera for most use cases. Nobody's asking for a camera keyboard.

Batteries went from 8-10 hours to full-day usage with moderate use and multi-day with light use. Nobody's asking for a battery keyboard.

Processors became powerful enough to handle real-time language processing, computational photography, and complex gaming. All things that absolutely required no keyboard.

Screens became HDR, high-refresh, and color-accurate. All enabled by removing other compromises.

The evolution of smartphones proves that investment in the right areas pays off massively. Physical keyboards would have been investment in the wrong area.

The Unspoken Reason Manufacturers Won't Try Physical Keyboards

Here's something rarely discussed: phones with physical keyboards are harder to recycle.

Modern smartphones are almost entirely recyclable. The glass screen can be separated. The metal frame is valuable. The electronic components can be sorted and processed. But a mechanical keyboard introduces plastics, springs, and moving parts that complicate recycling.

As environmental regulations tighten and companies face pressure to reduce e-waste, designing products that are easy to recycle matters more. A hardware keyboard phone would be worse for the environment and harder to recycle. That's another incentive not to pursue it.

It's not a reason you see in marketing materials, but it's part of the equation when manufacturers decide what to build.

The Final Reckoning: Why This Fad Will Definitely Fade

Hardware keyboard phones tick several boxes that suggest they're a fad rather than a trend:

First, they're built on solving a problem that's already solved. That's unstable.

Second, they appeal to a shrinking demographic. Younger people have no memory of BlackBerrys. They learned to type on glass. They don't feel nostalgic for something they never experienced.

Third, manufacturers have explicitly chosen not to pursue them despite having every resource to do so. That's a pretty clear signal.

Fourth, the phones that have tried have failed commercially. Not slightly underperformed—failed. Nothing Phone 2 is basically discontinued. Unihertz sells thousands. That's not a market, that's an aftermarket.

Fifth, the technology is moving in the opposite direction. AI, voice input, and haptic feedback are improving. Mechanical keyboards are becoming less competitive, not more.

This is a fad that will persist in the enthusiast community the same way vinyl records, mechanical watches, and film photography persist. There will always be people who prefer them. But mainstream? No. Future of phones? Absolutely not.

The hardware keyboard phone was an attempt to re-solve a problem that software had already solved better. It's a solution looking for a problem. And in the technology market, that's a fad with an expiration date that's already passed.

Conclusion: Embracing the Future That's Already Here

I understand the appeal of hardware keyboard phones. I really do. There's something satisfying about pressing a physical key. There's nostalgia for a simpler era of technology. There's frustration with today's always-on, always-connected world that a "back to basics" approach seems to promise.

But hardware keyboards aren't actually back to basics. They're a step backward disguised as a return to something better. They solve nothing that needs solving. They create problems that didn't exist.

The future of smartphone typing isn't mechanical. It's software getting smart enough that typing becomes invisible—you're thinking about what you want to say, and the phone is helping you express it. Voice input that understands context. Autocorrect that knows what you mean. Predictive text that anticipates the sentence before you finish it.

Those are the innovations worth caring about. Those are the areas where phones are genuinely improving.

Physical keyboards are the technology equivalent of a cover band. Familiar, comfortable, technically competent. But covering an old song, no matter how well you do it, isn't creating anything new.

The phones that matter aren't the ones trying to bring back the past. They're the ones building the future.

And that future doesn't have mechanical keyboards. It has something better: software smart enough that you stop thinking about typing altogether.

Maybe that's not as satisfying in the moment. But satisfaction in hindsight is what actually matters in technology. And in hindsight, the people who tried to bring back hardware keyboards will look like they were chasing nostalgia instead of chasing progress.

Which is exactly what they're doing.

So will hardware keyboard phones make a comeback? No. They won't. Because the problem they're trying to solve stopped existing years ago. And in technology, when the problem disappears, the solution that tries to bring it back becomes a footnote, not a trend.

That's what the data shows. That's what the market shows. That's what the direction of innovation shows.

The phone keyboard question isn't "will keyboards return?" It's "will people ever stop wishing they would?"

And the answer is yes. Once people actually try the future that's already here.

They just haven't yet.

Key Takeaways

- Hardware keyboard phones capture less than 0.5% market share while software solutions solve the original typing problem with 98%+ accuracy

- Adding mechanical keyboards increases phone thickness 50-80%, introduces failure points, and contradicts the entire evolution of smartphone design

- Major manufacturers like Apple, Samsung, and Google explicitly haven't pursued keyboard phones despite massive R&D budgets, signaling clear market rejection

- Software improvements in autocorrect, swipe typing, voice input, and haptic feedback have made glass keyboards competitive or superior to physical keyboards

- Nostalgia isn't innovation—the appeal is emotional memory of old devices, not actual performance advantages. The future moves toward smarter software, not mechanical parts

![Hardware Phone Keyboards: The Fad That Won't Last [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/hardware-phone-keyboards-the-fad-that-won-t-last-2025/image-1-1769024403128.jpg)