High On Life 2's Comedy Strategy: Why Squanch Won't Chase Everyone

Introduction: The Comedy Question Nobody Asked

When High On Life released in 2022, it arrived as a confident, brash bounty-hunting FPS that knew exactly what it wanted to be. The game wasn't trying to be Doom. It wasn't chasing Halo's sci-fi gravitas. Instead, Squanch Games built something deliberately goofy, deliberately comedic, and deliberately polarizing. Players either loved the irreverent humor or they didn't. There wasn't much middle ground.

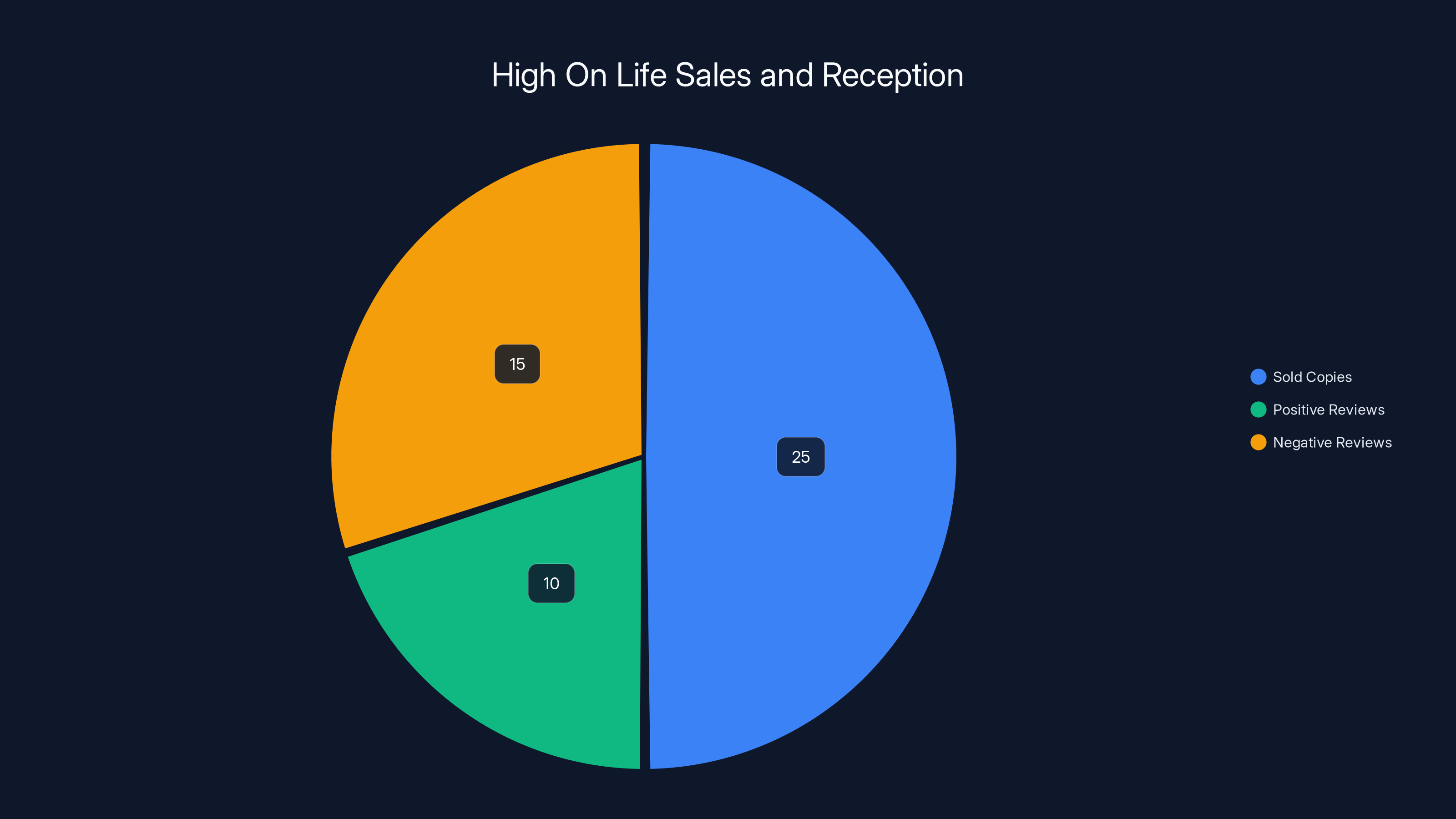

That humor came directly from the studio's co-founder Justin Roiland, best known for co-creating Rick and Morty. His particular brand of comedy, delivered through the main character's sentient gun Kenny, defined the entire experience. Some players found it refreshing. Others found it exhausting. The game sold 25 million copies despite middling critical reviews, proving that audience appeal and critical acclaim don't always align.

Then in 2023, Roiland left Squanch Games. The departure sent an unmistakable message to industry observers: this is the moment. This is when Squanch could soften its comedic edges, broaden its appeal, and potentially win over the skeptics who dismissed the original. This is when High On Life 2 could become something different.

Except that's not happening.

During an interview ahead of the sequel's release, CEO Mike Fridley made something abundantly clear. Squanch Games considered the possibility of toning down its humor to chase broader appeal. The studio ultimately decided against it. Not out of stubbornness, but out of clarity. Fridley explained that attempting to make everyone laugh would fundamentally weaken the product.

"The humor is our sense of humor," Fridley said. "I think it would be very detrimental to ourselves and our sanity, but also just detrimental to our business model, to try and chase making everybody laugh. Generally, those end up being kind of watered down, very generic, safe games."

This decision represents something increasingly rare in modern game development: a studio confident enough to reject the pressure to be universally liked. In an industry that often chases the broadest possible audience, Squanch is doubling down on its identity. Understanding why reveals something important about game design, comedy, and the business of entertainment.

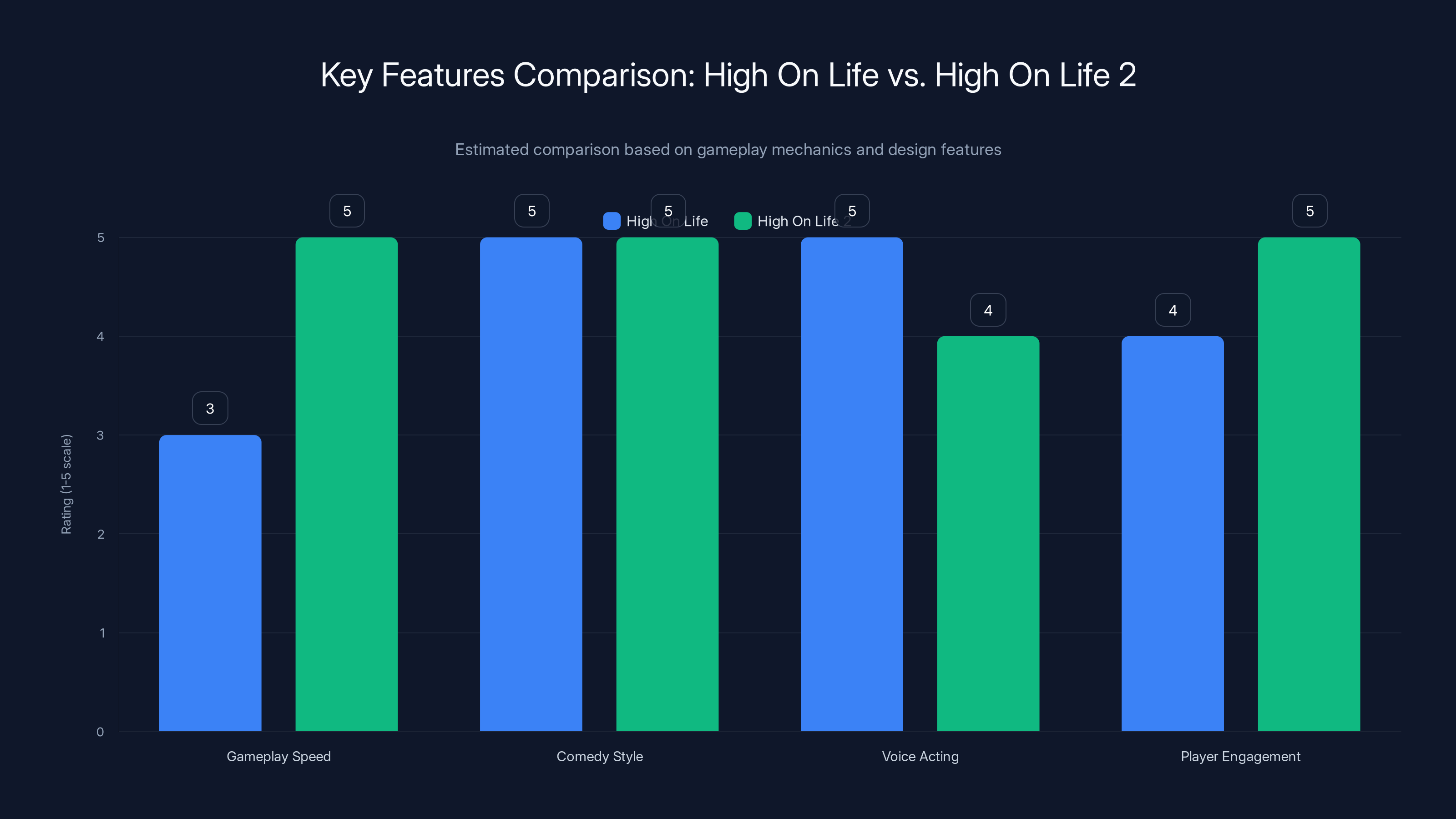

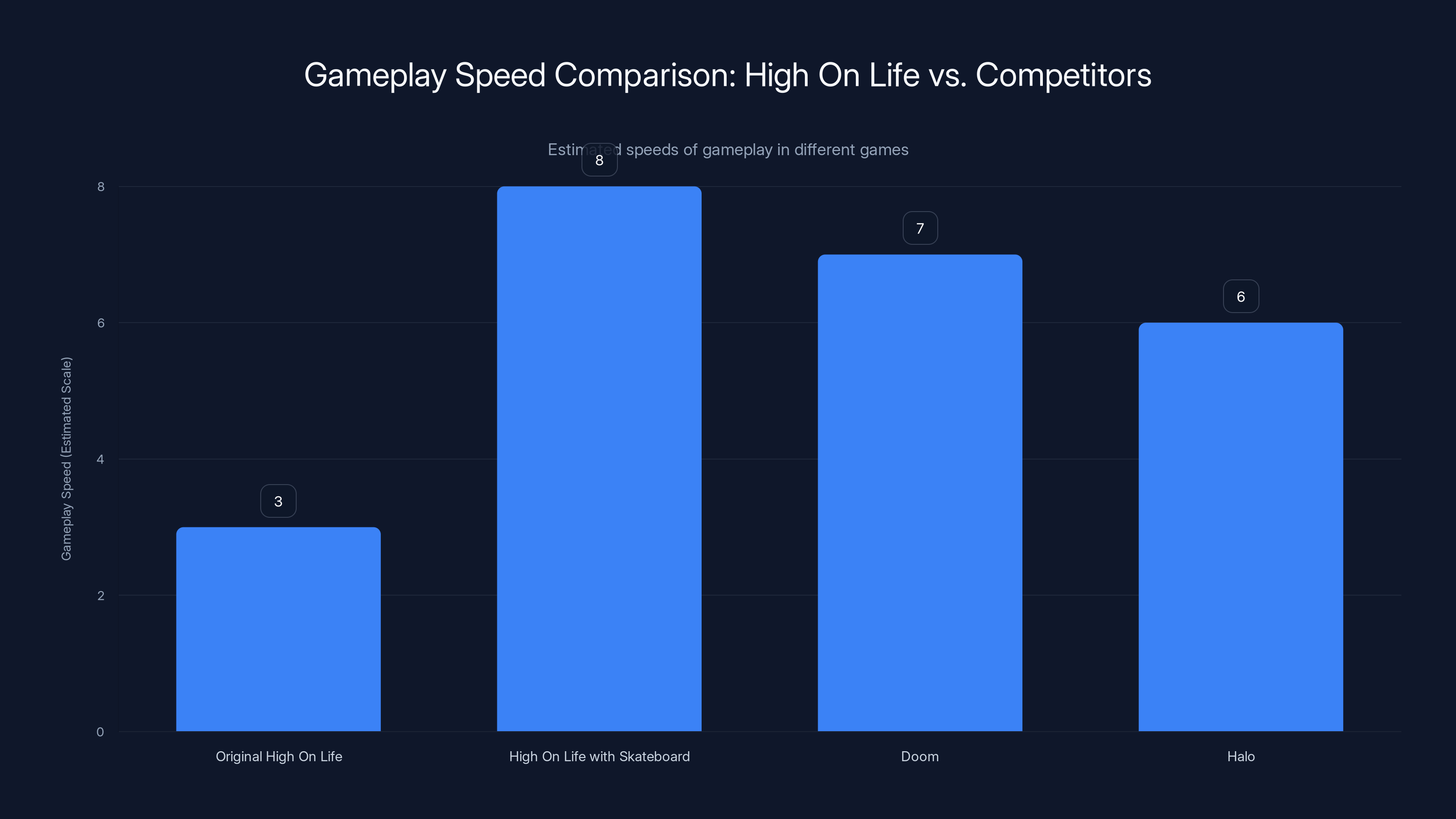

High On Life 2 enhances gameplay speed with a new skateboarding mechanic and maintains its comedic style, despite changes in voice acting. Estimated data.

Why Comedy Is Gaming's Biggest Risk

Comedy might be the most divisive element in any creative medium. Film directors know this. Television producers know this. Comedians certainly know this. But game developers sometimes underestimate how dangerous it is to make comedy central to a game's identity.

The problem is simple: humor doesn't scale. A joke that lands perfectly for one person falls completely flat for another. What makes one player laugh out loud makes another player cringe and look for the nearest exit. This isn't a failure of execution. It's fundamental to how humor works.

When you build a game around intense action, atmospheric storytelling, or challenging gameplay, you're working with elements that have broader appeal. Most people appreciate fast-paced combat. Most people understand tension and drama. Most people recognize what good level design feels like.

Comedy, though? Comedy is personal. It's influenced by sense of humor, cultural background, personality type, and a thousand other variables. You can't engineer comedy to be universally appealing without stripping away the elements that make it distinctive in the first place.

This is why comedy-forward games are so rare. Developers understand the risk. They know that making someone laugh is harder than making them feel scared, excited, or challenged. And when you tie your entire game to something that risky, you're guaranteeing that a significant portion of players will bounce off your product immediately.

High On Life 2 is betting that this reality is actually fine. Better than fine, actually.

The 25 Million Player Reality Check

Fridley's most revealing comment might have been this one: "The first game did 25 million players. I think it'd be a mistake to chase the folks that we probably will never convince that we're funny."

That's not defensiveness. That's mathematics.

High On Life's comedy didn't appeal to everyone. Critics dinged it for juvenile humor and one-note jokes. Some players found Kenny's voice lines (delivered in Roiland's distinctive Morty impression) grating rather than charming. The game could have been broader in its appeal.

But 25 million people bought it anyway. 25 million people played a game they knew was weird and silly and comedically specific. They weren't tricked into purchasing something they didn't want. They actively chose it.

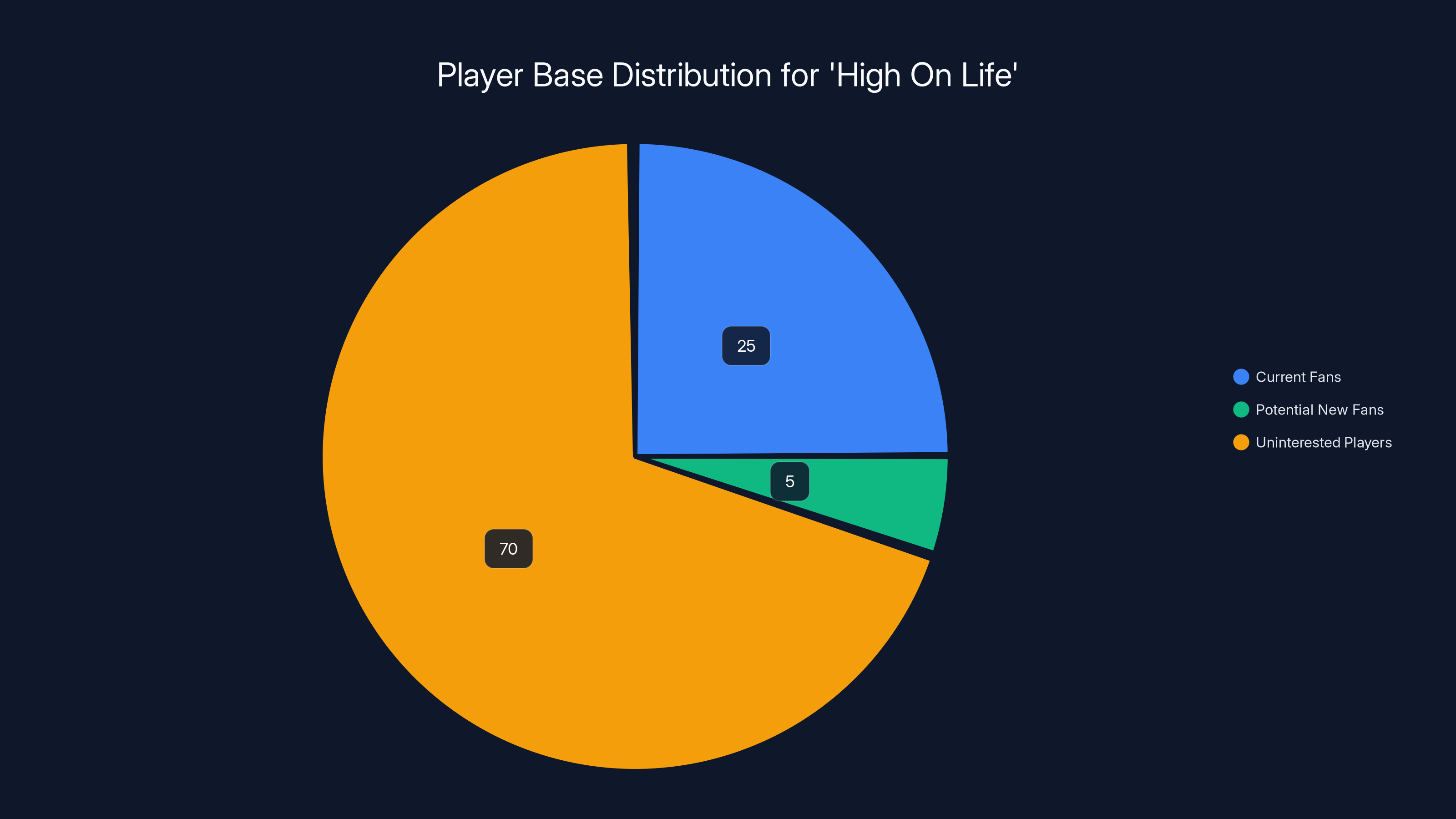

Squanch Games could spend resources chasing the people who actively dislike its comedy style. The studio could soften the jokes, broaden the references, make everything safer and more generic. Maybe that approach captures an additional 5 million players. It might also lose some of the 25 million who came specifically for the weird humor.

As Fridley explained, the math doesn't make sense. Trying to appeal to everyone typically means losing the people who appreciate your specificity. You're trading devoted fans for uncertain prospects.

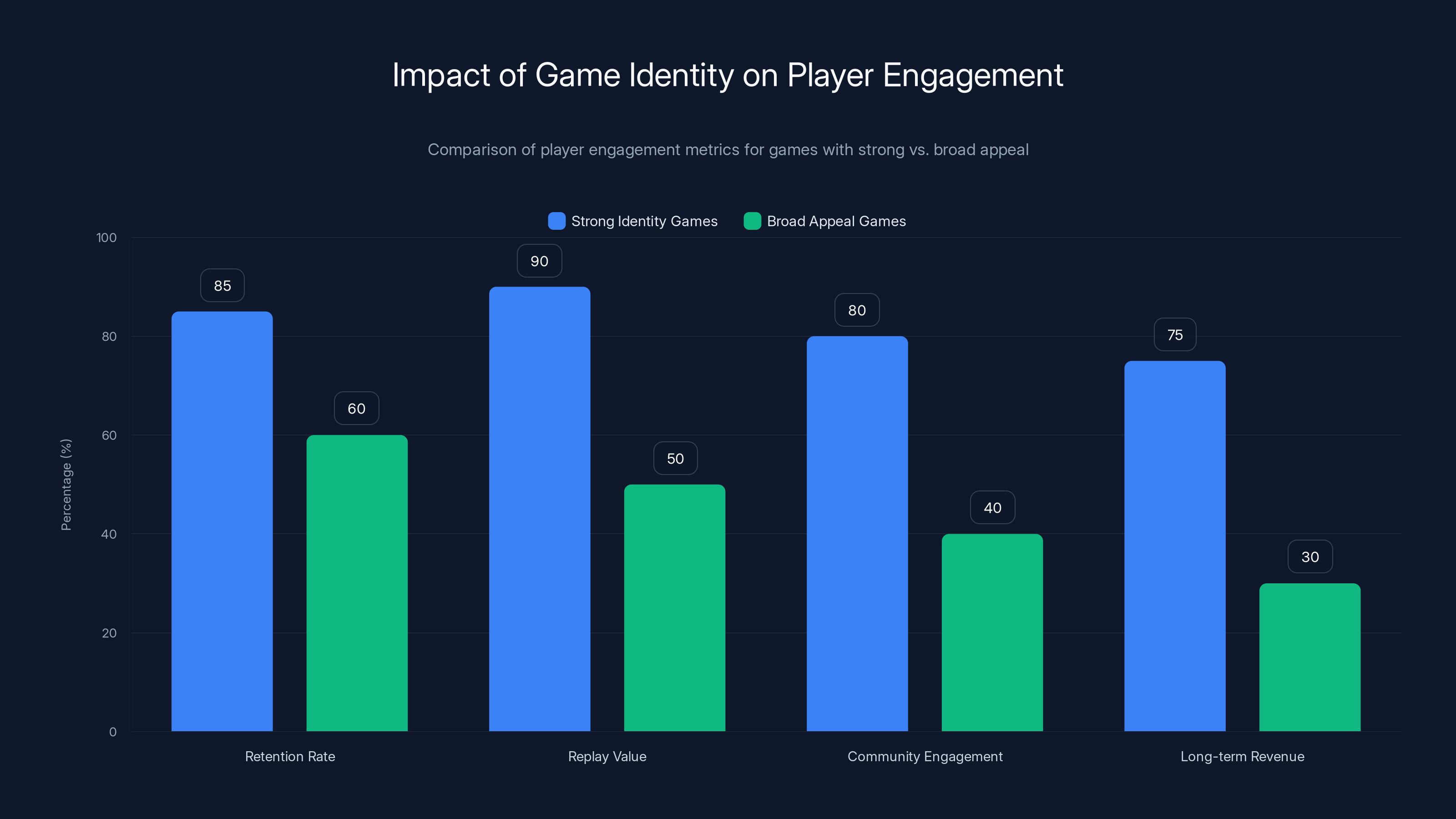

This is a lesson that applies far beyond games. When a creator tries to be everything to everyone, they usually end up being nothing to anyone. The most successful entertainment products aren't the ones with the broadest appeal. They're the ones with the strongest conviction.

Games with a strong identity show significantly higher retention, replay value, community engagement, and long-term revenue compared to those with broad appeal. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Justin Roiland's Departure: A Crossroads Moment

The elephant in the room is impossible to ignore. When Roiland left Squanch Games in 2023, it coincided with serious allegations that emerged publicly. For High On Life 2, his absence created a practical problem: how do you replace Kenny's voice while maintaining the character's essence?

Fridley addressed this directly, confirming that removing Roiland's performance was "a conscious choice." But he noted that Kenny "hasn't officially been killed off either." This suggests room for the character's eventual return, though the immediate plan is to move forward without him.

This decision reflects Squanch's broader philosophy about the sequel. The studio recognized that the Gatlians—the sentient guns that are the actual comedic voices of the series—are the heart of the experience. Kenny is important, but he's not the entire show.

"We're trying to be comedy character focused," Fridley explained. "Not having Sweezy or not having Gus, for example, in the second game would feel like it wasn't a High On Life game."

This is crucial. The studio didn't see Roiland's departure as an opportunity to fundamentally rebrand. Instead, it treated it as a structural problem to solve while preserving the core identity. The guns talk. The guns are funny. That fundamental mechanic survives the transition.

It's worth noting that making this decision requires confidence in something beyond just one performer. Squanch had to believe that the character work, writing, and comedic sensibility could survive and thrive without the person who originally shaped it. That's either arrogance or clarity, depending on whether it actually works.

The Skateboard: How Gameplay Can Address Pacing Concerns

While comedy is the most obvious element of High On Life's identity, there's another problem the original game struggled with that nobody talks about: it wasn't fast enough.

The original High On Life had solid gunplay, but the movement felt sluggish compared to contemporaries like Doom and Halo. Players who wanted to barrel through levels at high speed found themselves constantly stopped by the plodding pace. It wasn't broken, but it felt at odds with the game's comedic tone. Fast-paced comedy needs fast-paced gameplay.

Squanch's solution: replace sprint with skateboarding.

This might sound like a minor change. In execution, it's surprisingly sophisticated. The team didn't add skateboarding as an afterthought. They designed every level to be skateable. They balanced weapon fire while moving at speed. They made sure the skill ceiling stayed appropriate.

"We started to fall in love with it," Fridley explained of the skateboarding mechanic. "It was like, 'we want to make every level skateable'. And then it became like, 'Okay, let's just replace the sprint with the skateboard and see how that feels'."

Fridley went on to describe the tuning process: extensive internal and external playtesting to find the exact speed where "firing multiple weapons while traveling on a skateboard rail, grinding at that speed could all be done and processed in a way that felt like skillful, but also not like Dark Souls, skillful, where it's like too hard."

The resulting speed apparently makes the original feel like "running molasses" by comparison. This is significant because it suggests Squanch understands that comedy needs momentum. Stalling for laughs works. But laughs delivered at breakneck speed hit differently than laughs delivered while trudging through a level.

Gameplay and comedy are partners here, not separate concerns.

The Oddworld Connection: Influences Beyond the Obvious

High On Life's spiritual predecessor isn't another modern shooter. It's Oddworld: Stranger's Wrath, a 2005 cult classic that similarly blended quirky character design, irreverent humor, and interesting weaponry into an FPS experience.

When asked about this connection, Fridley confirmed it directly: Oddworld was "definitely an inspiration" for High On Life's design.

This matters because Oddworld: Stranger's Wrath was never a commercial powerhouse. It was always a niche product. But it found its audience precisely because it committed to its weird vision. The game didn't try to be Halo. It didn't apologize for its specific aesthetic and comedic sensibility. It was unapologetically itself.

High On Life is following the same playbook. Not trying to be something it's not. Not chasing mainstream credibility. Just making the weirdest, funniest, fastest bounty-hunting FPS possible and accepting that some people will love it and some won't.

The Oddworld influence also explains something about High On Life's overall design philosophy. Like Oddworld, it's a game that understands environment storytelling, character design through visual language, and how to make comedy serve the gameplay rather than interrupt it. These are lessons that a lot of modern games forget.

The introduction of skateboarding in High On Life significantly increased gameplay speed, aligning it more closely with fast-paced games like Doom and Halo. Estimated data.

What It Means to Stick to Your Guns (Pun Intended)

Fridley's comments represent a genuine shift in how some game studios think about their products. The conventional wisdom in corporate game development is to chase the broadest possible appeal. Market research, focus groups, and consumer data suggest that wider appeal equals more sales.

But Squanch Games is operating on a different principle: strong identity equals devoted players, and devoted players are worth more than casual players who barely engage with your product. A player who loves your game enough to defend it against critics is more valuable than a player who buys it on sale and forgets about it within two weeks.

This philosophy has real business implications. Games with strong identity tend to have better retention, higher replay value, and stronger community engagement. They're also more likely to become cult classics that generate long-term revenue through continued sales and word-of-mouth.

Conversely, games that try to appeal to everyone often end up pleasing nobody. They become the games that everyone forgot about two months after release. They're the ones that appear in "worst games of the year" lists not because they're broken, but because they have no identity at all.

Squanch Games looked at this landscape and chose a different path. The studio decided that High On Life 2 should be unmistakably High On Life. Not slightly broader. Not toned down for mass appeal. Just more of what made the first game distinctive, but faster, smoother, and technically more accomplished.

The Voice Cast Challenge: Replacing Without Losing Identity

Having committed to keeping the Gatlians and their comedic sensibility, Squanch faced a practical challenge: finding replacement voice actors who could maintain the comedic quality while bringing fresh interpretations to these characters.

This is genuinely difficult. Voice acting for comedy is a specialized skill. The timing has to be perfect. The delivery has to hit emotional beats while landing jokes. And in the case of a sentient gun character, the performance has to feel both like a person and like an object with personality.

Fridley didn't go into detail about the replacement cast, but his confidence in the comedy character focus suggests that Squanch found performers who could handle this challenge. The studio wasn't just looking for actors. It was looking for comedians who could maintain the show while the main host exited.

This speaks to something important about comedy in games. When done well, it's never about one performer. It's about writing, timing, character, and the interplay between characters. A good comedy game should theoretically survive personnel changes because the comedy is structural, not dependent on any one voice.

Whether High On Life 2 actually achieves this remains to be seen. But the fact that Squanch Games is trying suggests the studio understands this fundamental principle.

Why Direct Sequel Over Anthology?

One choice that might seem obvious but actually required significant deliberation was making High On Life 2 a direct sequel rather than an anthology series. This decision came with specific implications for narrative, character continuity, and overall design.

Fridley explained the reasoning: "Not having Sweezy or not having Gus, for example, in the second game would feel like it wasn't a High On Life game." The Gatlians aren't side characters. They're the primary vehicle through which the game's story is told and its comedy delivered.

An anthology approach would have meant introducing entirely new gun characters. Fresh voices. Fresh jokes. In some ways, that would have been the easy path. New guns mean no need to replace Roiland. New characters mean starting fresh with a clean slate.

But that approach would have also fundamentally changed what High On Life is. The game's identity is wrapped up in these specific characters. Sweezy, Gus, and the others carry the comedy and the personality. Replacing them with new guns would essentially be making a different game that just happens to share the "sentient gun" mechanic.

Squanch Games decided that wasn't acceptable. The studio wanted to make High On Life 2, not "Game Similar to High On Life But Different." That required bringing back the established character roster and integrating them into a new adventure.

This is a bet on character, story continuity, and identity over the easier path of starting fresh. It's another example of Squanch choosing the harder, more coherent option over the easier, more commercially flexible approach.

Estimated data shows that while 25 million players enjoy the game's unique humor, attempting to broaden its appeal might attract 5 million more but risks alienating the existing fanbase.

The Skill Ceiling Question: Fast Isn't Always Better

There's a risk in making a game significantly faster than its predecessor. Faster gameplay can feel better, but it can also narrow the audience. Players who enjoyed the original's slightly slower pace might find the sequel alienating. Speed rewards precision, reflexes, and practice. Some players prefer games that don't punish slower reactions.

Squanch addressed this concern through careful tuning. Fridley emphasized that the skateboarding speed was calibrated to feel "skillful, but also not like Dark Souls, skillful." In other words, the game is fast, but not so fast that it becomes inaccessible to players without fighting game reflexes.

This is a harder design challenge than just making a game faster. It requires understanding where the line is between "responsive and exciting" and "overwhelming and frustrating." It requires extensive playtesting with different player skill levels. It requires being willing to say no to speed that's fun for experts but terrible for everyone else.

Fridley's comment that the original now feels like "running molasses" suggests Squanch found a sweet spot. But it's worth noting that faster games are inherently more divisive than slower games. This change will probably gain new fans while losing some old ones. That's the trade-off of iterating on core mechanics.

The Comedy-Forward Game Category: Rarer Than It Should Be

Step back from High On Life specifically for a moment. The broader truth is that comedy-forward games are surprisingly rare. Most games that include humor use it as a seasoning. A joke here. A witty line there. But comedy as the primary experience? That's uncommon.

There are obvious reasons. Comedy is risky. It's personal. It requires talented writers. And crucially, it doesn't test well in focus groups. When you ask someone, "Do you prefer games with jokes or games without jokes?" the answer is usually "I prefer games with good jokes," which doesn't help you determine whether your jokes are good.

Squanch Games is operating in a category with almost no competition because almost nobody else is willing to take the risk. The studio is one of the only major publishers fully committed to making games where comedy isn't supplementary. It's the core experience.

This creates an interesting dynamic. High On Life doesn't have competition from other comedy-focused games. It has competition from every other game. Players interested in comedy games have essentially one option: High On Life.

For Squanch Games, this is both an opportunity and a burden. The opportunity is capturing everyone interested in comedy games. The burden is that the studio can't expand into adjacent categories. If High On Life 2 fails, there's no adjacent market to fall back on. The comedy-game audience either shows up or doesn't.

It's a high-risk, high-reward strategy.

Mike Fridley's Background: The Development Veteran Perspective

Understanding Squanch's decision-making requires understanding Mike Fridley's background. The CEO has been in game development for roughly two decades. He's worked on Elder Scrolls: Oblivion. He's worked on sports games like Rory McIlroy PGA Tour and NBA Live. He's seen what works and what doesn't across multiple genres.

This experience informs his perspective. Fridley isn't a first-time studio head gambling on a hunch. He's a veteran who has shipped games at scale, worked with publishers, and navigated the business side of game development. When he says that chasing universal appeal is detrimental, he's speaking from experience with products that tried to do exactly that.

Sports games are instructive here. NBA Live was designed to appeal to everyone: casual basketball fans, hardcore gamers, esports players, and statisticians. The game tried to be all things to all people. And it got caught in development hell, continually redesigned based on feedback, ultimately released a product that didn't excel in any particular direction.

Fridley learned from that experience. High On Life 2 is the opposite approach: clear identity, clear target audience, ruthless focus on what makes the product distinctive rather than what might appeal to additional demographics.

High On Life sold 25 million copies despite mixed reviews, highlighting a disconnect between audience appeal and critical acclaim. Estimated data for reviews.

The Critical Reception Paradox

Here's the interesting contradiction at the heart of this situation: High On Life sold 25 million copies despite middling critical reception. This gap between commercial success and critical appreciation reveals something important about modern game discourse.

Critics tend to value certain qualities: technical polish, narrative depth, mechanical innovation, artistic vision. Comedy, when it exists in games, tends to be evaluated against whether it appeals to the critic's specific sense of humor. If it doesn't land, critics often view the entire game as lesser.

Players, meanwhile, vote with their dollars. 25 million players decided that High On Life was worth their money despite the critical skepticism. These players presumably understood that they were buying a comedy game. They made an informed choice.

Squanch Games is essentially saying: critics will probably not love High On Life 2. The game's comedy might not land for people who didn't enjoy the original. And that's okay. The studio doesn't need critical acclaim to succeed. The studio needs to satisfy the players who are already convinced.

This is a refreshing perspective in an industry obsessed with critical scores. It suggests a studio that knows exactly who it's making games for and is willing to be at peace with not appealing to everyone else.

Maintaining Momentum While Respecting Legacy

High On Life 2 faces the classic sequel challenge: how much to change and how much to preserve. Change too much and you abandon what made the original successful. Change too little and you risk feeling stale.

Squanch's approach is measured. The skateboarding overhauls movement. The gameplay speed increases significantly. The voice cast partially changes due to circumstances. But the core identity remains: you're a bounty hunter with sentient guns, hunting aliens in a weird universe, and the entire experience is filtered through sharp comedy.

This middle path requires confidence that the core identity is strong enough to carry a sequel even with significant mechanical changes. Fridley's perspective suggests that confidence is there.

When he plays the original now, it feels slow. That's not nostalgia talking. That's a developer who has improved the game and knows it. The sequel apparently feels like the original High On Life always should have felt.

If that confidence is justified, High On Life 2 will be the stronger game. If it's misplaced, the changes will have alienated existing fans without gaining enough new players to compensate. There's no way to know until the game is in player hands.

The Industry Conversation This Creates

Squanch Games' commitment to its comedic identity in the face of pressure to broaden appeal sends a message throughout the industry. It says: you don't have to chase universal approval. You can make something specific and deliberately risky and still find commercial success.

This is conversation the industry needs. Too many games are designed by committee, focus-grouped into blandness, and released with the personality sanded off. The middle-of-the-road game that appeals to nobody particularly but offends nobody either has become a design formula.

High On Life 2 is choosing a different path. And if it's successful, other studios might take note. There's space in the market for games with strong identity. There's an audience for products that take risks. Comedy-forward games might remain rare, but at least they won't be viewed as a commercial impossibility.

The Broader Question: Can Sequels Improve on Originals?

High On Life 2 is fundamentally a test of a simple proposition: can a game improve on its predecessor by doubling down on what made it distinctive rather than trying to address every criticism?

The conventional wisdom says no. Sequels should be broader, safer, more accessible. They should learn from where the original stumbled and correct those mistakes. They should try to appeal to the people who bounced off the first game.

Squanch Games is arguing that this conventional wisdom is wrong. The studio is betting that improving on the original means making it faster, tighter, and more confidently itself. It means accepting that some players will still find the humor grating. But the players who love this franchise will love the sequel even more.

This is a genuinely interesting thesis to test. If High On Life 2 is successful, it validates an approach to sequels that emphasizes refinement over expansion. If it fails, it becomes another cautionary tale about studios that don't listen to feedback.

The most likely scenario is somewhere in between: High On Life 2 will be a more technically accomplished game that appeals even more strongly to the core audience while still failing to convert critics and comedy-skeptical players. Which is probably exactly what Squanch Games wants.

What Success Looks Like for a Niche Franchise

For High On Life 2, success doesn't mean becoming the most played game on Xbox Game Pass. It doesn't mean universal critical acclaim. Success means the core audience shows up, the game is better than the original, and the franchise continues.

Squanch Games is playing a long game. First game: 25 million players, mixed critical reception. Second game: hopefully more players, more devoted fans, stronger community. Third game onward: established franchise with clear identity and dedicated audience.

This is the Cult Classic pathway. Games like Borderlands, Spec Ops: The Line, and XCOM all followed similar trajectories. Not immediately universally loved. But genuinely appreciated by the people who connected with them. Building strong communities and long-term value.

That pathway requires patience. It requires resisting the pressure to broaden appeal. It requires believing that 25 million devoted players is better than 30 million casual players. Squanch Games is betting that the sequel proves they were right.

Looking Forward: The Comedy Game Renaissance

If High On Life 2 is commercially and critically successful, it could open the door for other comedy-forward games. Publishers might become more willing to greenlight games where humor is central. Developers might feel more confident making bold comedic choices.

The alternative is that the game reinforces the perception that comedy games are too niche to justify investment. In which case, High On Life remains as the exception that proves the rule: there's an audience for comedy games, but it's small enough that few studios will try.

Fridley's confidence suggests he believes the first scenario is possible. The studio has made its bets. The sequel is coming. The comedy is not being softened. The game is being made for the people who wanted what the first game delivered, not for the people who want something different.

That's either brilliance or stubbornness. The market will decide which.

FAQ

What makes High On Life 2 different from the original?

High On Life 2 features significantly faster gameplay through its skateboarding mechanic, which replaces traditional sprinting. The sequel maintains the comedy-forward design and sentient gun characters (Gatlians) from the original while featuring updated voice actors due to Justin Roiland's departure from the studio. The game has been tuned for improved movement speed and responsiveness while maintaining a balanced skill ceiling that doesn't exclude less experienced players.

Why didn't Squanch Games tone down the humor for the sequel?

Squanch Games CEO Mike Fridley explained that attempting to chase broader appeal by watering down the comedy would actually weaken the game and damage the studio's business model. The original game achieved 25 million players despite middling critical reviews, proving there's a dedicated audience that specifically wants the studio's comedic style. Rather than chase the critics who disliked the humor, Squanch Games chose to double down on the identity that attracted those 25 million players.

How did the team handle Justin Roiland's departure?

When Roiland left Squanch Games in 2023, his voice character Kenny was removed as a conscious choice. However, Fridley noted that Kenny hasn't been officially killed off, leaving room for potential future inclusion. The focus shifted to maintaining the Gatlians (the sentient guns), which are the primary comedic voice of the game, with replacement voice actors ensuring the characters' essential nature remains intact.

What's the skateboarding mechanic's purpose in gameplay?

The skateboarding mechanic replaced traditional sprinting to increase movement speed and game pacing. Squanch Games designed every level to be skateable and tuned the speed extensively through internal and external playtesting. The goal was to make high-speed gameplay feel skillful without becoming Dark Souls-level difficult, allowing players to fire weapons while moving at speed in a way that feels responsive and exciting.

What is the significance of Oddworld: Stranger's Wrath as an inspiration?

Fridley confirmed that Oddworld: Stranger's Wrath (2005) was definitely an inspiration for High On Life's design. Like Oddworld, High On Life is a niche product that commits fully to its weird vision rather than chasing mainstream appeal. Oddworld demonstrated that games could succeed by being unapologetically specific and character-driven, a lesson that directly influenced Squanch Games' approach to both High On Life games.

Why did Squanch choose a direct sequel over an anthology series?

Squanch Games decided that removing established Gatlian characters like Sweezy and Gus to create an anthology would fundamentally change what makes High On Life distinctive. Since the sentient guns are the primary vehicle for storytelling and comedy, maintaining character continuity was essential to preserving the game's identity. A direct sequel allowed the studio to keep these beloved characters while delivering a new bounty-hunting adventure.

How does Fast gameplay speed compare to competitors like Doom and Halo?

The original High On Life had slower movement compared to contemporary shooters. Fridley noted that when he plays the first game after working on the sequel, it feels like running through molasses. The sequels increased speed significantly through the skateboarding mechanic, bringing the gameplay closer to the pace of modern action shooters while maintaining High On Life's unique comedic identity and character-focused design.

What does Squanch Games consider success for High On Life 2?

Squanch Games isn't chasing universal critical acclaim or broadest possible audience appeal. Success means delivering an improved sequel that excites the core audience of players who loved the original, maintaining the franchise's specific comedic identity, and building a long-term cult classic status similar to franchises like Borderlands or XCOM. The studio is betting that a dedicated, devoted player base is more valuable than casual players.

Key Takeaways

- Squanch Games deliberately chose NOT to tone down High On Life 2's humor despite pressure following Justin Roiland's 2023 departure, betting that 25 million devoted players are more valuable than attempting to chase critics

- The skateboarding mechanic in the sequel addresses the original's pacing issues by replacing sprint with a constantly-available high-speed movement option that's integrated into every level design

- Maintaining established Gatlian (sentient gun) characters was essential to preserving High On Life's comedic identity, so the studio chose a direct sequel over an anthology approach despite voice actor changes

- CEO Mike Fridley's 20 years of game development experience informs his philosophy that trying to appeal to everyone results in generic, watered-down games that fail to satisfy any audience

- High On Life 2 represents a risky but deliberate bet on niche, identity-driven game design over broad market appeal, potentially pioneering a pathway for more comedy-focused games if commercially successful

Related Articles

- Double Fine's Kiln: The Pottery Party Brawler Changing Indie Games [2025]

- Animal Crossing New Horizons Switch 2: Nostalgia, Isolation, and Loss [2025]

- Xbox Game Pass Premium and PC Merger: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Best Nintendo Switch Online Hidden Gems You're Missing [2025]

- Cairn Game Review: The Climbing Journey That Teaches Perseverance [2025]

- Sea of Remnants: The Free-to-Play Pirate RPG Redefining Open-World Design [2025]

![High On Life 2's Comedy Strategy: Why Squanch Won't Chase Everyone [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/high-on-life-2-s-comedy-strategy-why-squanch-won-t-chase-eve/image-1-1770896380615.jpg)