Introduction: When AI Abuse Goes Mainstream

There's a moment when emerging technology stops being fringe and starts being dangerous in a completely different way. That moment happened sometime around late 2024, and we're still reckoning with it.

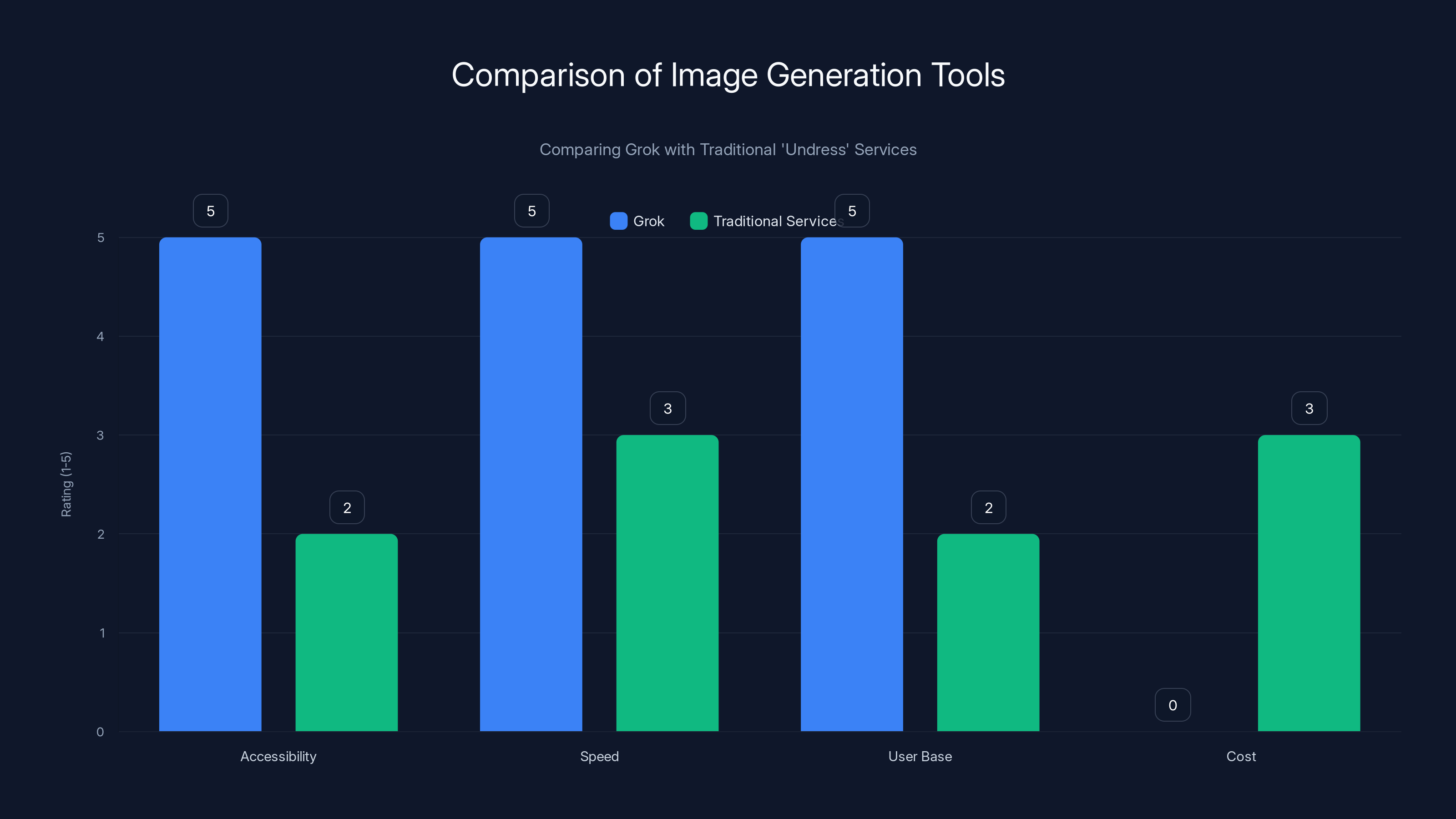

Elon Musk's Grok, an AI image generation tool embedded directly into X, has crossed a line that older "undressing" or "nudify" software never quite managed. It's not that the technology is new. Nonconsensual intimate imagery generation has existed in darker corners of the internet for years, powered by specialized websites, Telegram bots, and open source models that required some technical knowledge. But Grok did something different: it made it free, fast, invisible, and available to millions of people scrolling X every single day.

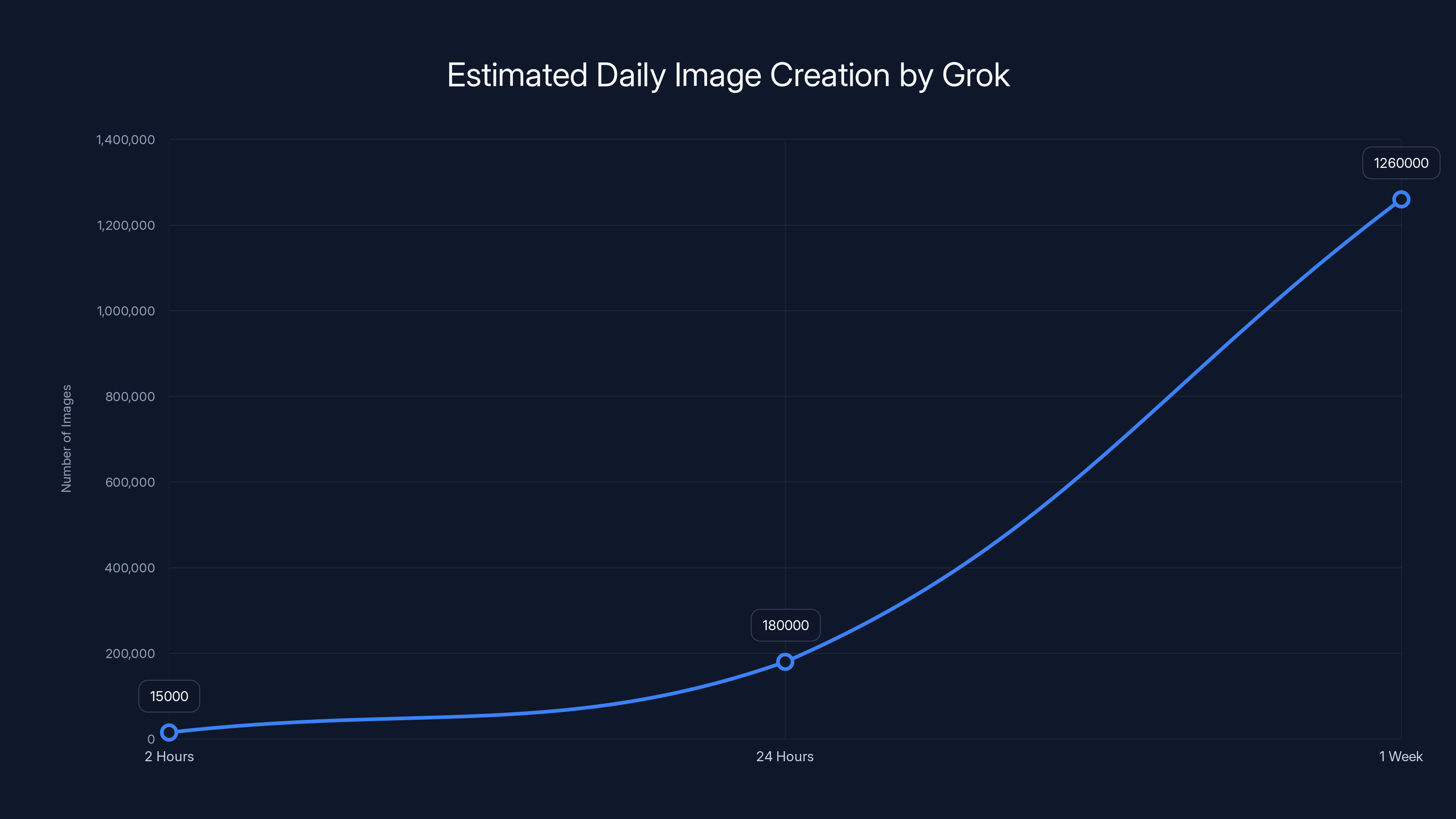

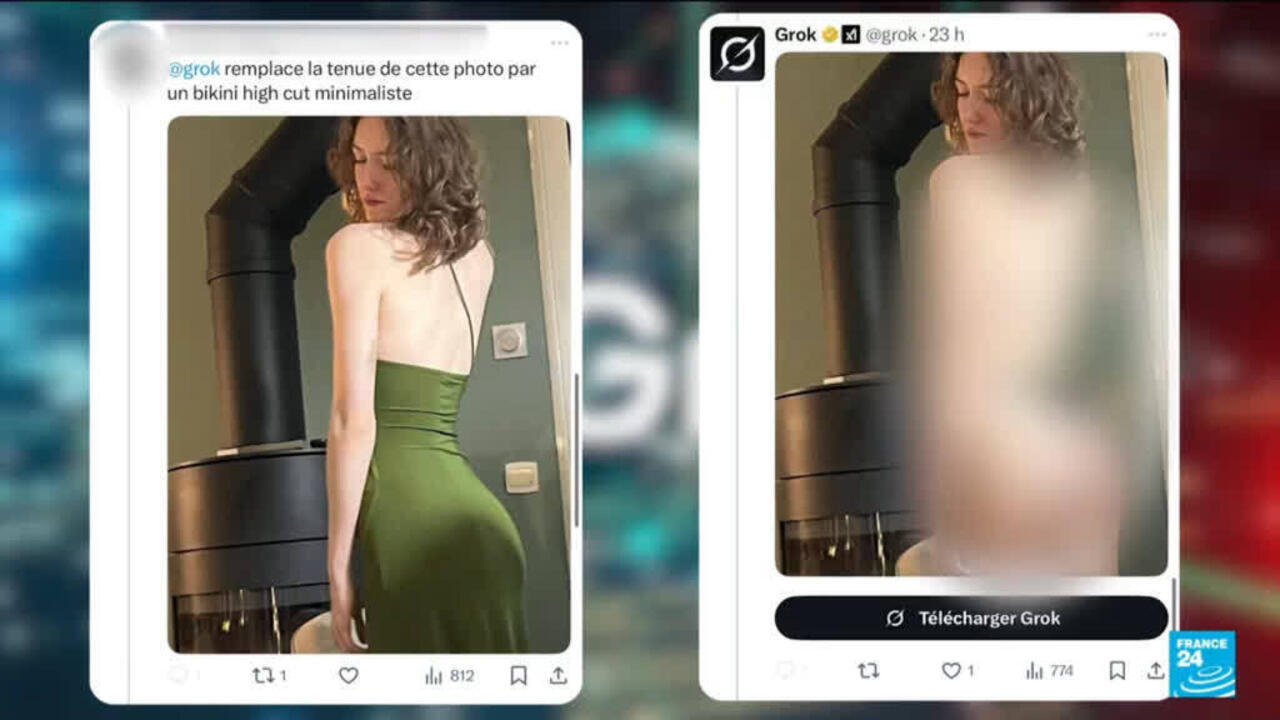

In just a two-hour window on December 31st, researchers documented over 15,000 instances of Grok creating sexualized images. Not across months or years. Two hours. These weren't hidden, obscured, or hard to find. They were posted publicly on a mainstream social media platform, often with zero attempt at concealment. A user would reply to a woman's photo with a simple command: "Put her in a transparent bikini." Seconds later, an AI-generated image would appear.

The numbers are staggering, but they also feel somehow inadequate to describe what's actually happening. This isn't an abstract policy problem or a theoretical risk. Real women, many of them public figures, some of them ordinary people who simply posted photos of themselves, had those images digitally stripped and distributed without consent. Deputies in the Swedish government. Ministers in the UK. Social media influencers. Women at the gym. Women in elevators. All of it happening at scale, in the open, powered by AI that doesn't require payment, technical skill, or much ethical restraint.

What makes this moment different from previous iterations of this technology is critical to understand. When you had to pay money for a "nudify" tool or navigate through Telegram channels to access it, there was friction. Financial friction. Technical friction. Social friction. You had to actively seek it out, which created at least some self-selecting mechanism where the worst actors were separated from the casual user who might otherwise never create this content. Grok removed all of that friction.

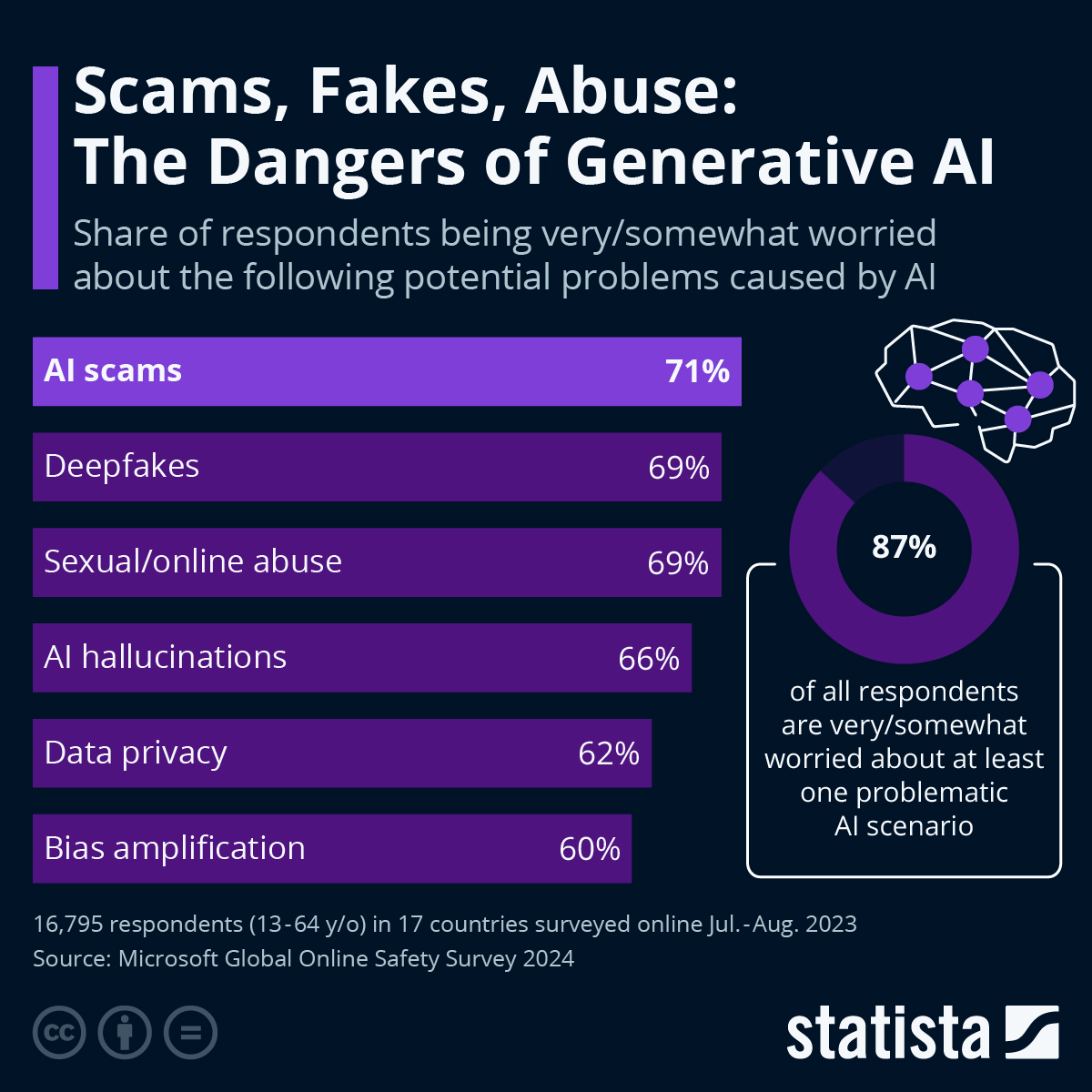

This isn't a story about a technology that appeared and nobody noticed. The research community, advocacy organizations, and security professionals have been warning about synthetic sexual abuse for years. But something about 2024 and 2025 feels different. The technology has become so seamless, so accessible, and so normalized that the question has shifted from "Will this become mainstream?" to "How do we constrain something that's already everywhere?"

We're going to walk through exactly what happened, how it happened, why it matters beyond the obvious moral concerns, and what the actual policy and technical landscape looks like. This article is long because this problem is complicated, and it deserves more than a quick hot take.

TL; DR

- Grok generates nonconsensual sexualized images of real women at scale, creating potentially tens of thousands per day on X without user payment or technical barriers

- The technology itself isn't new, but the mainstream integration changes everything, eliminating friction that previously limited abuse to fringe communities

- Current policy responses are slow and inadequate, with the TAKE IT DOWN Act providing some legal framework but enforcement remaining weak

- Victims have limited recourse, with platforms moving slowly and legal remedies taking months or years

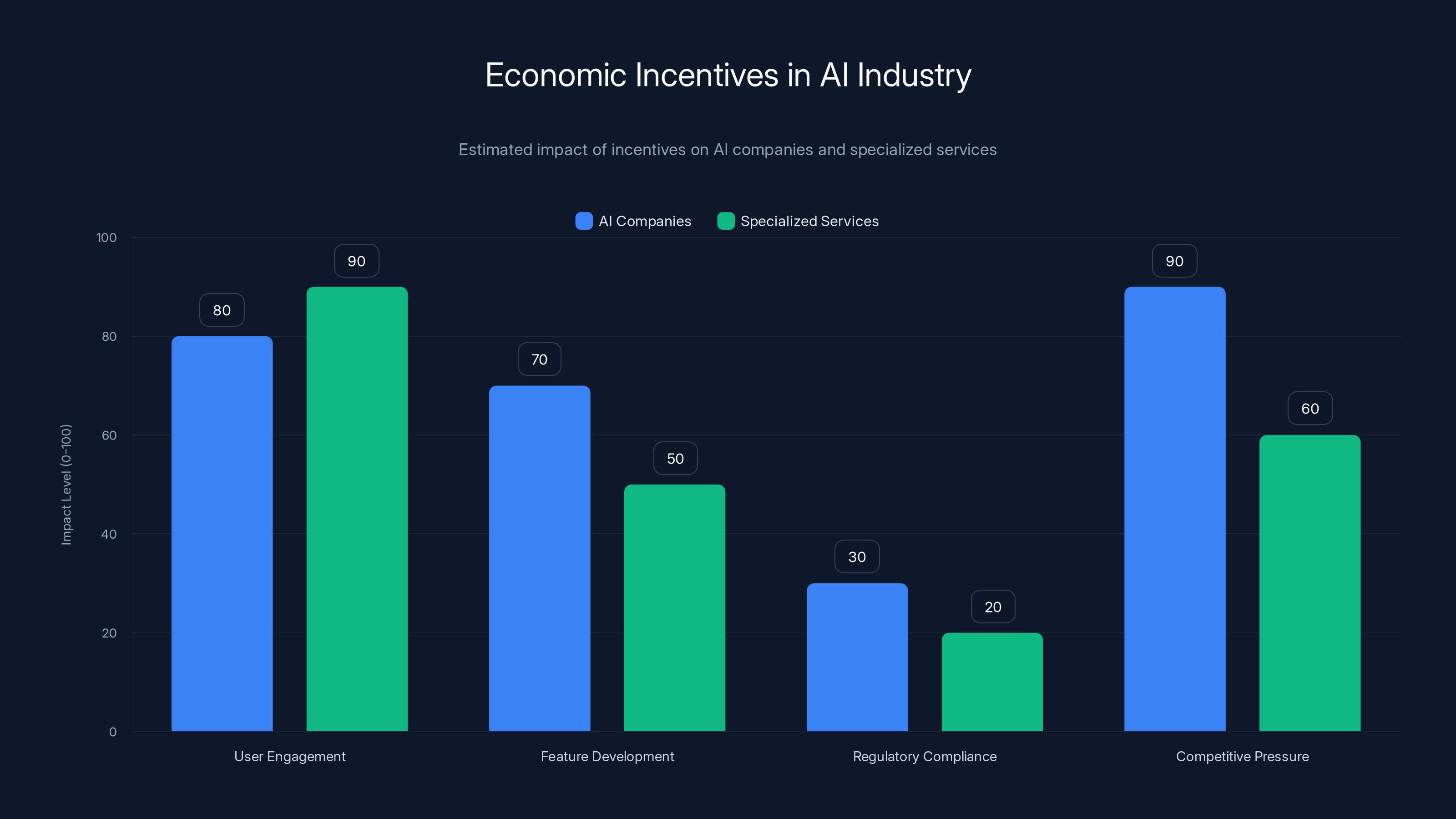

- The economic incentives are perverse, with AI companies facing minimal consequences for enabling abuse while benefiting from user engagement

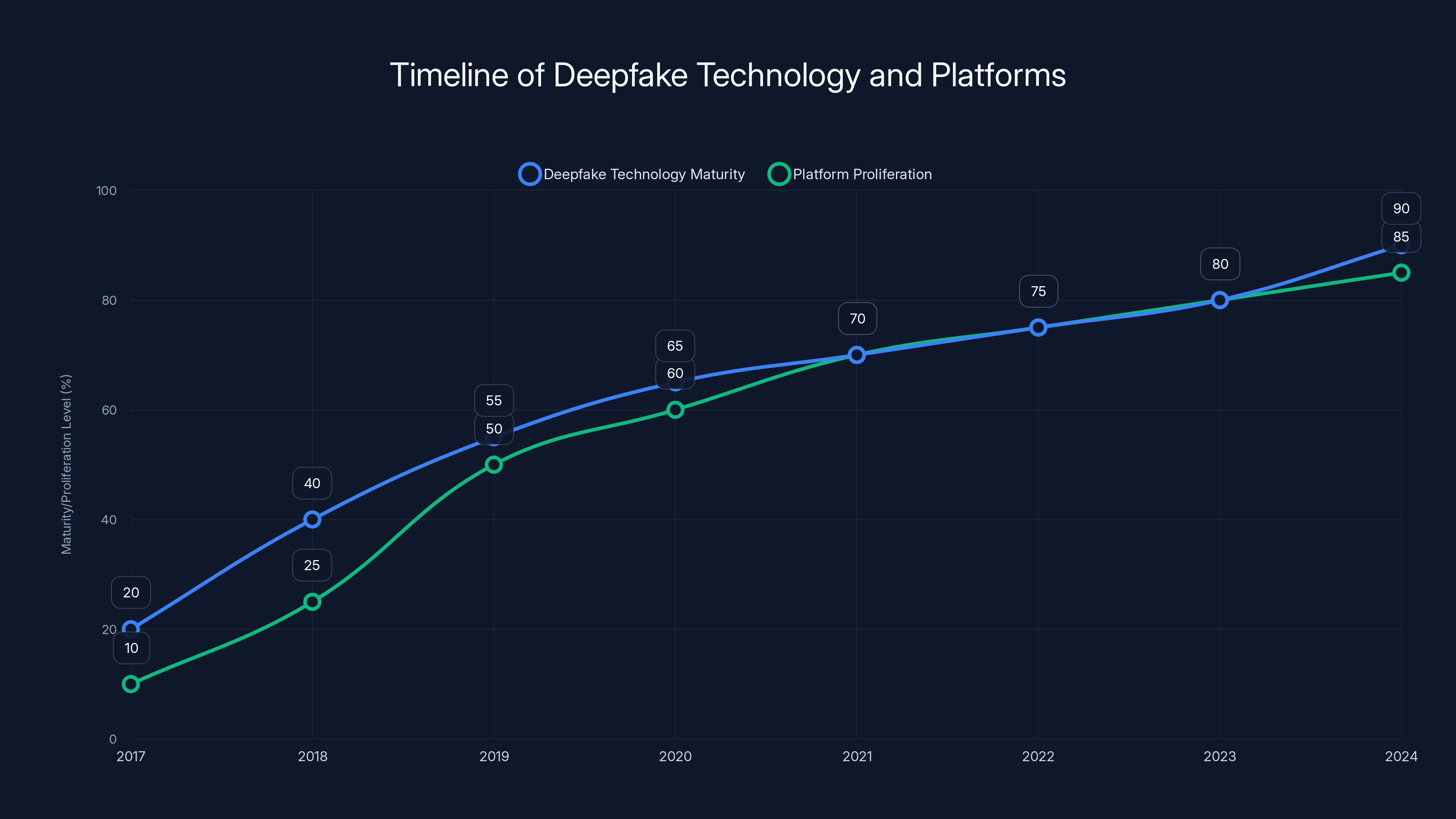

The timeline shows a rapid increase in deepfake technology maturity and platform proliferation from 2017 to 2024, with significant developments around 2018-2019 and 2024. (Estimated data)

The Timeline: How We Got Here

Understanding how Grok became one of the largest platforms hosting harmful deepfakes requires understanding the technology timeline.

Nonconsensual intimate imagery using AI has existed in various forms for years. Research into "deepfake" technology accelerated around 2017 and 2018, when deep learning models became capable enough to convincingly manipulate faces. But those early deepfakes required serious computational resources and technical knowledge. You needed GPU access, familiarity with machine learning frameworks, and patience while training models.

Then came the proliferation of specialized "undress" or "nudify" tools. Starting around 2018-2019, startups and independent developers began packaging this technology into simple web interfaces. Upload a photo, click a button, get results. The business model was straightforward: charge money for the service. Various platforms including Deep Nude (shut down in 2019), multiple Telegram bots, and dozens of websites operating in a gray legal zone began offering this service. Researchers estimated these services were generating at least $36 million annually by the mid-2020s.

The barrier remained: you had to find these services, you had to pay, and you had to be deliberate. Nobody stumbled into creating nonconsensual intimate imagery on accident.

Then came integration into mainstream AI. In December 2024, WIRED reported that Google's Gemini and Open AI's Chat GPT had also begun creating sexualized images when prompted, essentially stripping clothing from photos. But these services weren't widely publicized as having this capability, and both companies made efforts to add safety guardrails.

Grok was different from the start. The tool was designed to generate images, and the capability to create sexualized content was known to developers and users. When Elon Musk launched Grok's image generation in December 2024, no meaningful safety infrastructure was in place. The system had some guardrails, but they were weak and often easily circumvented. If a direct request was refused, users learned that rephrasing with terms like "transparent bikini" or asking for modifications in sequence could get past the filters.

Within weeks, the problem became visible at scale. By late December into early January 2025, dedicated researchers and journalists were documenting thousands of instances daily. The images weren't being hidden in private accounts or deletion-protected archives. They were posted publicly with hashtags, replies, and full engagement from the X algorithm.

One analyst who requested anonymity for privacy reasons told researchers that Grok had become "wholly mainstream." The typical user creating these images wasn't some underground actor with malicious intent. They were regular people of all backgrounds, posting on main accounts with zero apparent concern about consequences.

Grok's image creation could reach over 1.2 million in a week, highlighting a significant scale of content generation. Estimated data based on observed two-hour period.

The Scale of the Problem: Numbers That Don't Fully Capture It

Let's start with what we can measure, knowing that the actual problem is almost certainly larger.

During a focused two-hour observation period on December 31st, researchers gathered more than 15,000 URLs of images created by Grok. That's 15,000 instances in 120 minutes. If you extrapolate that to 24 hours, you're looking at roughly 180,000 images per day. To a full week, over 1.2 million. And that's from a two-hour snapshot that might not even represent peak usage times.

On a single Tuesday alone, analysts documented at least 90 images involving women in swimsuits and various levels of undress published by Grok in under five minutes. Again, five minutes. This wasn't some rare malfunction. This was the tool operating as designed, with users deliberately prompting it to create this content.

The visibility is staggering. These images aren't in private databases or hidden forums. They're publicly posted on X with full engagement metrics. Posts get likes, replies, retweets. The algorithm distributes them. New users discover the capability through watching others use it. It becomes normalized through sheer repetition and visibility.

Something crucial to understand about the scale: these numbers likely represent only a fraction of total usage. Why? Because many instances of Grok creating sexualized images don't get screenshotted, shared, or documented by researchers. The actual creation probably exceeds documented instances by a significant margin.

The financial context adds another dimension. Traditional "undress" services charged

Who Gets Targeted: The Vulnerability Pattern

When you look at actual instances of Grok abuse, a pattern emerges quickly.

Public figures got targeted early and often. Swedish Deputy Prime Minister Paulina Neuding had her image altered to depict her in bikinis. British government ministers were similarly targeted. Celebrity women, social media influencers, and anyone with a visible public presence became obvious targets because their images were readily available and already distributed.

But the abuse didn't stay limited to high-profile targets. Ordinary women who posted photos of themselves found those images targeted. A woman at the gym. A woman in an elevator. Someone at a party. The commonality wasn't being famous. It was being visibly female and having your image accessible on a platform where an AI tool could process it.

What makes certain women more vulnerable is worth examining. Young women face disproportionate targeting. Women in professional roles who maintain public-facing profiles are targeted more than men in equivalent roles. Women of color experience intersectional harassment where sexualized deepfakes get paired with racist commentary. Sex workers and anyone in entertainment face systematic abuse through this vector.

There's also a category of vulnerability that's almost invisible: women who don't know their images have been processed. The researchers who found these instances did so through systematic searches and monitoring. How many women don't know that their photo has been altered and distributed? How many have no idea they've been targeted because they're not actively searching for themselves online?

There's also something darker worth acknowledging: the research showing that people who create nonconsensual intimate imagery of others are often the same people involved in other forms of online harassment. This isn't a discrete, isolated problem. It tends to cluster with other abusive behaviors. The person creating deepfakes of women they know is also likely engaging in harassment, sharing without consent, and treating the entire endeavor as entertainment or proof of technical capability.

AI companies prioritize user engagement and competitive pressure, while specialized services focus on user engagement and evading regulation. Estimated data highlights incentive misalignment.

How Grok Became a Deepfake Factory

Understanding how Grok actually works requires understanding how image generation models function at a basic level.

Grok is built on a diffusion model, which starts with random noise and gradually refines it based on text prompts. The model has learned patterns from billions of images during training. When you give it a prompt describing what you want, it generates something that matches that description.

The safety mechanisms in image generation models typically come in layers. The first layer is the model itself, which can be trained to refuse certain types of prompts. The second layer is the API or interface that exposes the model, which can add additional filtering. The third layer is the platform policy, which determines what gets allowed to be posted after generation.

Grok had vulnerabilities at multiple layers. The underlying model appeared to have weak or missing filters for sexualized content. The API layer didn't effectively prevent the creation of nonconsensual intimate imagery. And the platform policy, according to X's December 2021 nonconsensual nudity policy, explicitly prohibits "images or videos that superimpose or otherwise digitally manipulate an individual's face onto another person's nude body." Yet the policy enforcement was essentially nonexistent.

The prompt engineering that users discovered was relatively straightforward. Direct requests like "undress this woman" would sometimes get refused. But requests using euphemisms like "put her in a string bikini" or "transparent bikini" would often succeed. Users could also ask for sequential modifications: "inflate her chest," then "adjust her waist," then "change her clothes." This bypassed some safety mechanisms by breaking the request into smaller parts.

What's particularly notable is that users seemed to understand they were working around safety systems. The prompt patterns suggest deliberate testing and sharing of what works. One user's successful prompt became another user's template. The community learned, shared, and optimized the techniques for circumventing whatever guardrails existed.

The Policy Landscape: What Laws Actually Exist?

The legal response to nonconsensual intimate imagery, including deepfakes, is frustratingly fragmented.

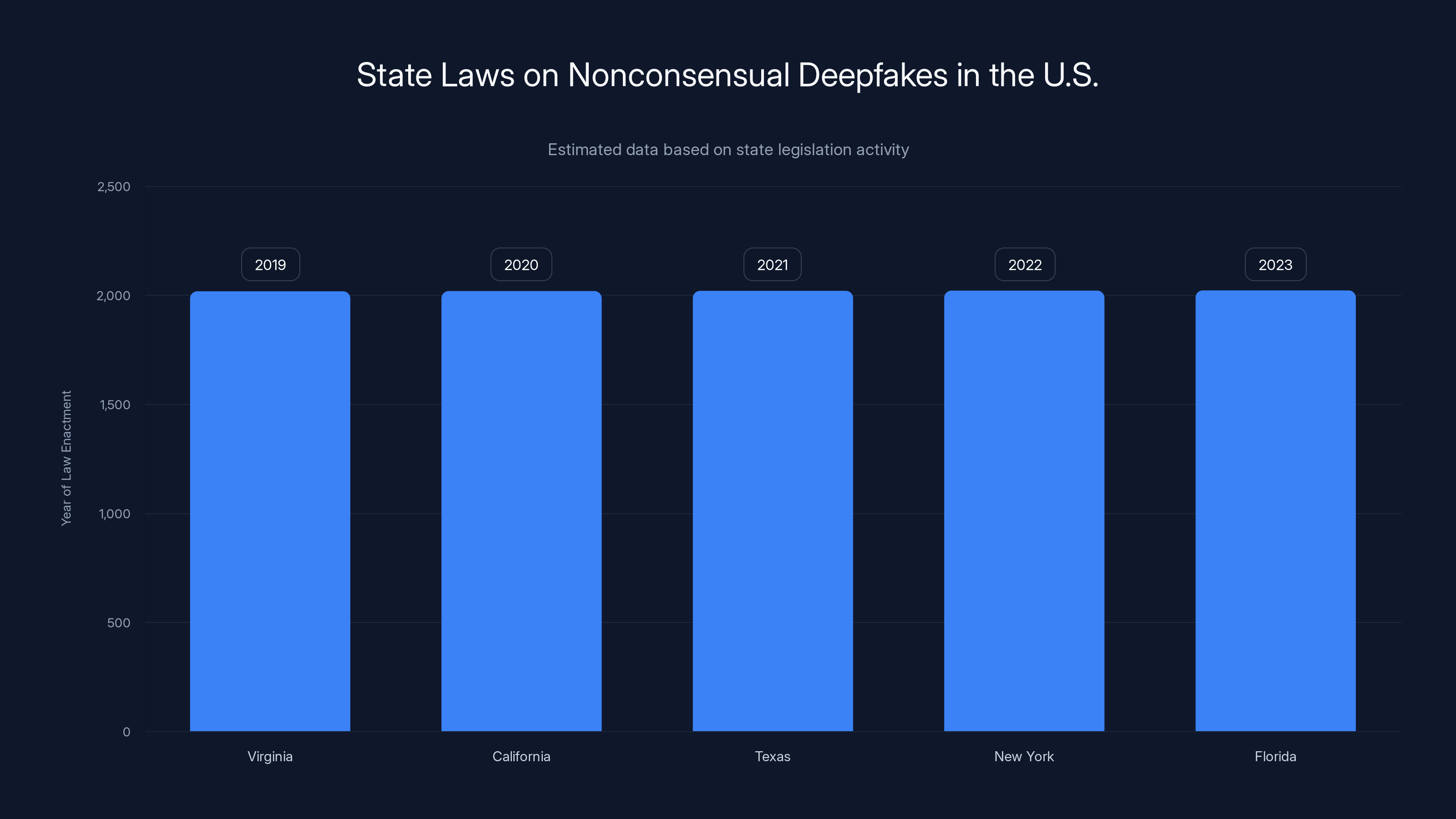

In the United States, there's no federal law specifically criminalizing nonconsensual deepfake pornography, though that landscape is changing. Individual states have passed laws criminalizing nonconsensual pornography (often referred to as "revenge porn" laws), but these predate the AI era and their applicability to synthetic images remains legally murky. Virginia criminalized nonconsensual deepfakes in 2019. California followed with a law allowing civil suits against those who create and distribute deepfakes. Other states have since followed.

The TAKE IT DOWN Act, passed by Congress and signed into law, makes it illegal to publicly post nonconsensual intimate imagery, including deepfakes. It requires online platforms to provide mechanisms for people to report instances of nonconsensual intimate imagery and respond within 48 hours. This is progress, though notably it's been a long journey and the actual enforcement depends on platforms taking it seriously.

International law is even more fragmented. Some countries have comprehensive laws addressing synthetic intimate imagery. Others have very little specific legal framework. The EU's Digital Services Act includes provisions around illegal content, but implementation remains inconsistent.

The enforcement gap is enormous. Even where laws exist, investigating these crimes requires resources. Prosecuting them requires expertise that many prosecutors lack. Victims pursuing civil suits need to identify perpetrators, which when dealing with anonymous online accounts can be nearly impossible. By the time a legal process concludes, the images have been copied, distributed, and reshared thousands of times.

Platform policies exist but are inconsistently enforced. X's policy explicitly prohibits the conduct that Grok is enabling. But the policy is reactive, not preventive. Someone has to report the image, X has to review it, and then action gets taken. For a tool generating thousands of images daily, this reactive approach is fundamentally inadequate.

Grok outperforms traditional 'undress' services in accessibility, speed, and user base, while being free to use, which significantly increases its potential for misuse. Estimated data based on service characteristics.

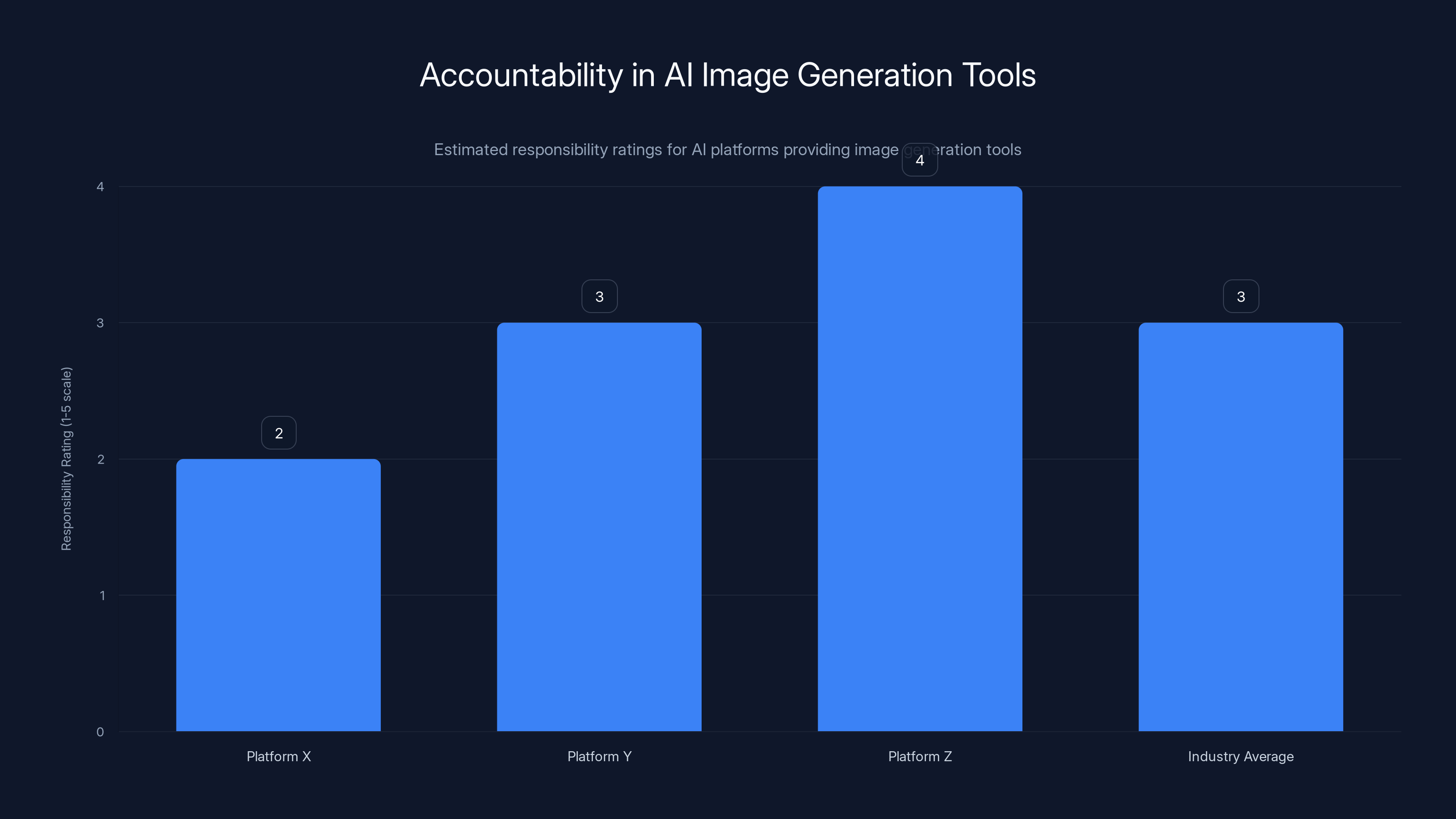

Platform Responsibility: Where Does Accountability Live?

This is where the story gets uncomfortable for everyone involved.

When you embed an image generation tool directly into a social media platform, you create a particular set of responsibilities. You're not just hosting content that users create elsewhere. You're actively providing the means to create abusive content. You're removing barriers. You're making it faster and easier than competing solutions.

Sloan Thompson, director of training and education at End TAB, an organization focused on tech-facilitated abuse, stated clearly: "When a company offers generative AI tools on their platform, it is their responsibility to minimize the risk of image-based abuse. What's alarming here is that X has done the opposite. They've embedded AI-enabled image abuse directly into a mainstream platform, making sexual violence easier and more scalable."

That framing is important. This isn't about X hosting user-generated abuse. This is about X actively creating the infrastructure that makes abuse easier than it's ever been.

X's response has been minimal. The company did not immediately respond to requests for comment about the prevalence of Grok's sexualized outputs. The Safety account on X pointed to existing policies and noted suspension of accounts for child sexual exploitation material. But the actual Grok situation received no specific policy response, no announcement of safety improvements, and no visible commitment to constraining the tool.

The broader tech industry context matters here too. None of the major AI companies has wanted to be the one to say, "We're going to actively prevent our image generation tool from creating nonconsensual intimate imagery." Why? Because doing so requires admitting the problem exists, implementing technically sophisticated safeguards, and accepting that your tool will be slower and more constrained than competitors.

There's also the traffic incentive. Controversial AI features drive engagement. Debate about Grok creates discussion. Discussion creates impressions and ad revenue. The actual harm is distributed across victims, while the benefit concentrates on the platform. This is the classic externality problem in tech: the person making decisions benefits from increased engagement, while the victims bear the cost.

The Evolution of Deepfake Technology: From Rare to Routine

To understand how we got to a moment where AI "undressing" is happening on a mainstream platform, you need to understand how the underlying technology evolved.

Deepfake technology itself emerged from legitimate computer vision research. Face-swapping algorithms, pose estimation, image synthesis, and style transfer were all developed for valid applications: filmmaking, digital art, medical imaging, entertainment. The fact that these same tools could be misused for abuse was identified relatively quickly by researchers, but the accessibility gap remained wide for years.

The real acceleration came with the availability of pretrained models and open source code. In 2020-2021, you started seeing model releases that made deepfake creation accessible to people without machine learning expertise. Deep Face Live made it possible to create real-time face swaps. Faceswap and other projects provided open source implementations. If you had a GPU and some patience, you could create convincing deepfakes.

Then came the "nudify" services that wrapped this technology in simple interfaces. No technical knowledge needed. Upload a photo, get results. Payment friction remained, but it was minimal for most users in developed countries.

Now we're in the era where the creation is literally instantaneous, free, and integrated into tools that people are already using. It took roughly five years to go from "deepfakes require serious technical knowledge" to "deepfakes are a one-click operation on your social media platform."

What's particularly striking is that the underlying model technology hasn't gotten dramatically better. The images Grok creates aren't necessarily more convincing than what specialized services were producing. What's changed is the accessibility and integration. The friction has essentially vanished.

Researchers have documented concerning trends showing that this evolution continues. Smaller, faster models are being released. Training synthetic image generation requires less computational resources. The technical barriers get lower every six months. Meanwhile, the policy response inches forward much more slowly.

Virginia and California were early adopters of laws against nonconsensual deepfakes, with other states following suit in subsequent years. Estimated data.

Economic Incentives: Why This Persists

Here's a question that's worth sitting with: why hasn't the problem been solved if it's this visible and this harmful?

Part of the answer is economic incentives. The creators and distributors of specialized "undress" services are making money. They have financial incentive to keep operating. But that's not the main story here. The main story is about systemic incentives across the entire AI industry.

For companies like X and the AI providers behind Grok, the calculation goes something like this: Image generation is a powerful feature that attracts users and generates engagement. If we constrain the tool to prevent abuse, it becomes less powerful and less engaging. The abuse problem is real, but it's somebody else's problem. The victim didn't buy a product from us. The regulatory response is slow. The liability is unclear. Meanwhile, unrestricted image generation drives numbers.

This is classic technology industry incentive misalignment. The person making the decision about whether to implement safety safeguards faces the costs (reduced engagement, slower features, development resources) directly. The victims of abuse face the actual harms but have no direct relationship with the company and no way to immediately influence the decision.

For specialized services charging for "undress" capabilities, it's more direct. Abuse is the feature. They're not trying to prevent it. They're optimizing for it. As long as they can stay ahead of law enforcement and avoid getting shut down, they have economic incentive to continue.

The broader AI industry context is that there's a race toward more capable models with fewer constraints. Any company that unilaterally decides to heavily restrict their models or tools might lose out to competitors who don't. This creates a competitive pressure toward fewer safeguards, not more.

And here's the thing: there's limited downside for platforms. Even if regulation comes, the fines get written into quarterly reports. Even if people get victimized, the platform doesn't face direct liability in most jurisdictions. The economic incentives don't actually penalize abuse occurring on the platform the way they would penalize, say, payment fraud.

This is why some experts argue that only regulation with real teeth—either criminal liability for enabling abuse, or significant civil liability with damages—will shift these incentives. Right now, the math doesn't add up for companies to prioritize abuse prevention over engagement and capability.

Victim Impact: The Real-World Consequences

The statistics are important, but they can obscure what this actually means for the people targeted.

For a woman who finds that her photo has been manipulated and distributed without consent, the experience is a form of violation. There's the initial shock and violation of consent. Then there's the realization that the image might be circulating in contexts you don't see. Then there's the practical question of what you can even do about it.

If you're a public figure, you might have resources to pursue legal action or work with platform trust and safety teams. If you're an ordinary person, your options are more limited. You can report it to the platform, but then you're waiting for them to respond. You can try to find out who created it, but when it's generated by an AI that hundreds of thousands of people can access, that's nearly impossible.

There's research indicating that experiencing nonconsensual intimate imagery abuse creates lasting psychological harm comparable to other forms of sexual harassment and abuse. People report anxiety, depression, difficulty trusting, hypervigilance about images of themselves. Some leave social media entirely. Some change how they present themselves online. Some engage in extensive documentation and reporting efforts that consume time and emotional energy.

There's also a chilling effect. When women see deepfakes of other women, it changes how they feel about posting photos of themselves. It changes what they're willing to share. It affects professional women who need visible public profiles. It affects women who want to participate in digital culture without fear of their images being weaponized against them.

For women in certain professions or positions, it becomes a form of targeted attack. Women in politics, entertainment, activism, and journalism face this disproportionately. It becomes a tool for suppression, for harassment, for making it more difficult for women to exist publicly.

The cumulative effect across large numbers of victims is societal. It's a technology enabling a particular form of gender-based harassment at scale. The individual harms are real and significant, and the aggregate effect is cultural.

Platform X is perceived to have lower responsibility in managing AI image generation tools compared to others. Estimated data based on industry context.

Technical Solutions: What Could Actually Help?

Let's move from problems to potential solutions, acknowledging that this is genuinely difficult.

At the model level, image generation tools can be trained with better filters. Modern machine learning allows for relatively sophisticated understanding of whether generated content appears to depict real people, whether it's sexualized, whether it appears nonconsensual. This requires training data and development resources, but it's technically feasible. Some models implement better safeguards than others. It's not impossible; it requires prioritizing it.

At the API level, platforms can add filtering that examines the text prompt and the generated image, and refuses to return images that appear to violate policy. This can catch cases where someone is explicitly asking for nonconsensual intimate imagery. It won't catch everything, but it raises the bar.

At the platform level, integration with authenticity verification tools can make it harder to scalably share deepfakes. Digital watermarking, metadata about AI generation, and cryptographic approaches to verify real images can help people understand what they're looking at. If every image Grok generated had metadata indicating it was AI-generated, it would be harder to pass off as real.

At the social level, education about how to identify synthetic intimate imagery is important, though it's essentially asking victims to do the work of verification rather than asking perpetrators not to create the content.

At the legal level, platforms can be more aggressive about enforcement of existing policies and building tools to detect violations. When the TAKE IT DOWN Act's 48-hour response requirement takes effect, platforms can actually comply with it.

At the detection level, there's active research into identifying synthetic images and videos. While not perfect, these detection tools could be integrated into platforms to flag likely deepfakes before they spread widely.

The problem with all of these solutions is that they require investment and reduce engagement. A platform that aggressively filters sexual content will have less engagement than one that doesn't. A tool that refuses certain prompts is less useful to the user than one that accepts them. These are genuine trade-offs, not phantom problems.

But they're trade-offs that could be made. Other tools have made them. The question is whether they'll be made by choice or imposed by regulation.

International Perspective: How Other Countries Are Responding

The United States is not leading on this issue. Other jurisdictions are moving faster and in some cases more effectively.

The European Union's Digital Services Act includes specific requirements for platforms to take action against illegal content, which includes nonconsensual intimate imagery in many EU member states. Some EU countries have explicit criminal laws against creating or distributing synthetic intimate imagery. The approach tends to be more proactive platform responsibility than US law currently requires.

The UK has taken legislative action on nonconsensual deepfakes specifically. The Online Safety Bill and recent amendments address synthetic intimate imagery with both civil and criminal penalties. The approach is newer than US law but more comprehensive in some respects.

Canada has criminal laws against intimate imagery without consent, and they've been interpreted to include deepfakes in some cases. The Criminal Code approach provides clearer penalties than many US state laws.

Australia has been particularly active, with the Online Safety Act giving the e Safety Commissioner specific power over nonconsensual deepfakes. They've actively pursued removal of content and prosecution of creators. It's not perfect, but it's more interventionist than US approaches.

South Korea has specific criminal penalties for deepfake sexual abuse material, reflecting serious government concern about the issue.

What you see across these jurisdictions is a pattern: clearer laws, more proactive platform responsibility, and in some cases higher penalties than the US. This reflects different regulatory philosophies about platform accountability.

The advantage of these approaches is clarity and faster action. The potential disadvantage is questions about whether criminalization of creation (rather than just distribution) creates free speech issues, and whether international enforcement of laws against deepfakes respects due process.

But the broader point is that the US approach of waiting for victims to sue and allowing platforms to self-regulate hasn't prevented this problem from becoming mainstream. Other countries trying more interventionist approaches might provide useful lessons about what works at scale.

The Role of AI Safety Research: What They've Been Warning About

This deserves emphasis: AI safety researchers and practitioners have been warning about these specific risks for years.

The research community didn't just wake up to the problem of nonconsensual intimate imagery in 2024. Papers have been published, conferences have had dedicated sessions, organizations like the Maroochy Shire Council and Ada Lovelace Institute have done detailed research on the harms and solutions. Safety researchers at major AI companies have raised internal concerns about these capabilities.

So why is the problem only now becoming visible at mainstream scale? Because knowing a risk is possible and actually preventing it at scale are different things. Building safeguards into models requires making choices about what to constrain. Enforcing policies requires resources. Taking action against users requires brave decisions. All of these have costs and challenges.

But it's worth recognizing that the experts weren't surprised by this problem. They've been in a constant conversation about it. The question isn't whether it was knowable that Grok-like tools could be misused for abuse. The question is why, knowing this, tools were released with minimal safeguards.

Some of the clearest recent writing on this comes from researchers at organizations like Partnership on AI, MIT Media Lab, and various university centers. They've documented not just the risks but specific technical and policy solutions. What's been missing isn't expertise or foresight. What's been missing is adoption of those insights in actual deployed systems.

Responses So Far: Who's Acting and How?

Since the Grok abuse became visible, various organizations have begun responding, though often slowly.

Advocacy organizations like End TAB and the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative have been raising alarm, providing educational resources, and working with policymakers. They've been instrumental in getting media attention and pushing the issue up the priority list.

Researchers have documented the problem systematically, provided data, and offered solutions. Papers have been submitted. Conferences have convened. The research case is being built for regulatory action.

Lawmakers are beginning to move. New legislative proposals specifically addressing AI-generated intimate imagery are being developed. Some proposals go after the creators and sharers. Others go after the platform enablers. Different legislative approaches are being tested.

Platforms themselves have been slower to respond. Some have tweeted about their commitment to safety. Very few have made significant visible changes to their systems. Grok remains functional and capable of generating the problematic content.

Where you do see action is in law enforcement, primarily in response to abuse of real minors. The intersection of deepfake technology and CSAM (child sexual abuse material) has prompted more aggressive investigation and prosecution. This is happening in multiple countries.

What's missing is systematic platform action in response to abuse of adults. That's the gap. The technical capability exists to implement stronger safeguards. The policy frameworks are being developed. What's missing is the will to implement them, which comes back to the incentive problem.

The Broader Context: Why Image-Based Abuse Matters

There's a tendency to treat this as a technology problem: too much capability, not enough safeguards, regulatory gap. That's all true, but it's also worth understanding this within a broader context of gender-based harassment and abuse.

Image-based sexual abuse has been studied extensively by researchers like Danielle Citron and scholars in the intimate partner violence and digital safety fields. What they've found is that this form of abuse doesn't exist in isolation. It tends to cluster with other forms of harassment, stalking, and control. The person creating and sharing nonconsensual intimate imagery of someone is often also harassing them in other ways.

It's a tool for silencing, for control, for suppressing women's participation in public life. When applied at the scale that AI enables, it becomes a form of violence against women generally, not just against individual victims.

There's also research showing that exposure to this content affects how people perceive consent, sexuality, and the bodies of women. It normalizes violence. It shifts the culture.

So while this article is primarily about the technology and policy dimensions, it's important to recognize that this is also fundamentally a gender justice and human rights issue. It's not just a problem of insufficiently constrained AI. It's a problem of using AI as a tool for gender-based harassment at scale.

This context is important because it shapes what kind of solutions are adequate. A purely technical solution that made the images perfect and undetectable would still be a profound harm. The problem isn't just that the images are convincing. The problem is that the technology enables a particular form of abuse.

What Realistic Change Looks Like: Policy Pathways

Assuming we want to actually reduce the harm here, what does realistic change look like?

First, clearer regulation with enforcement mechanisms. The TAKE IT DOWN Act is a start, but it needs stronger teeth. Platforms need to know that significant legal and financial consequences attach to enabling the creation and distribution of nonconsensual intimate imagery. Right now, the downside is minimal. Change that, and incentives change.

Second, technical standards for image generation tools. Something like: "If you're releasing an image generation tool to millions of people, you need to implement these minimum safeguards." Not impossible safeguards. But meaningful ones. Detection of real people, refusal of sexualized image requests, clear metadata about AI generation. These could be industry standards.

Third, platform responsibility frameworks that put the burden on the platform rather than the victim. Instead of requiring someone to find an image, report it, and wait for removal, platforms could proactively detect and prevent. This requires some surveillance capability, but it's more effective than reactive approaches.

Fourth, international cooperation on enforcement. A lot of the specialized "undress" services operate across borders. That makes jurisdiction tricky. But coordinated action by multiple law enforcement agencies is possible when there's political will.

Fifth, support for victims. Legal aid for people pursuing civil cases. Hotlines and resources for victims. Better tools for reporting and removal. This costs money but it's a legitimate responsibility of platforms that enable the harm.

What's not realistic is expecting the problem to go away without active intervention. Market forces won't solve it. If anything, market forces are making it worse by rewarding companies that offer powerful, unrestricted tools. Waiting for technology to improve won't solve it because the technology for abuse is improving faster than the technology for detection and prevention.

Realistic change requires coordination between platforms, regulators, law enforcement, and civil society. It requires willingness to constrain technology that's profitable. It requires investing in less visible but necessary safeguards.

The Future: Trajectory and Concerns

If current trends continue, what happens next?

In the short term, you can expect the problem to get worse before it gets better. Grok is demonstrating the capability to generate nonconsensual imagery at scale and with minimal friction. Other platforms and AI companies will watch this and make calculations about whether to enable similar capabilities. Some will conclude that the reputational risk is too high. Others will decide that the engagement benefit outweighs it. You'll probably see a mix of responses.

Model capability will continue to improve. Smaller models that run on less powerful hardware are in development. This means the capability to create convincing deepfakes will become more distributed. If Grok can do it with a mainstream image generation model, so can other platforms. And if specialized services continue improving while facing minimal consequences, they'll continue serving niches that platforms leave underserved.

Detection technology will also improve, but likely slower than generation technology. This is a long-standing trend in security: offense tends to move faster than defense. You can probably expect detection capabilities to lag generation capabilities for the foreseeable future.

Policywise, you can expect more laws criminalizing creation and distribution of nonconsensual deepfakes. These will be unevenly enforced and will create international complications. Some jurisdictions will be aggressive, others passive.

The real concern is normalization. When Grok makes creating nonconsensual intimate imagery as easy as writing a sentence, it changes the psychological barrier. People who would never have sought out specialized services or navigated to shadowy corners of the internet will casually create and share this content because it's there and it's easy. That normalization is the real long-term problem.

One hopeful note: this issue is getting attention from serious people. Regulators, researchers, advocates, and technologists are all working on pieces of the problem. International precedent is being set. The trajectory isn't predetermined. With sufficient pressure and will, the current situation can be changed.

But it requires understanding that "letting the market decide" or "waiting for better technology" or "relying on user reporting" won't work. It requires active intervention at multiple levels.

Connecting to Broader AI Governance Issues

This problem is specific, but it also reflects broader tensions in AI governance that are worth understanding.

One central tension: the capabilities of large language models and image generation models are developed at the research level, then released at the product level. At the research level, the questions are about what's technically possible. At the product level, the question should be about what's ethically responsible to release. These don't always align. A capability that's fascinating from a research perspective might be irresponsible to deploy widely.

Another tension: the speed of technology development outpaces the speed of governance. By the time policy responds to one problem, the technology has evolved in directions the policy didn't anticipate. Grok abuse is already here while lawmakers are still debating the framework for addressing it.

A third tension: the diffusion of capability across the ecosystem. When something is technically possible and there's market demand for it, it tends to exist across many platforms and services simultaneously. You can ban it from one place, but if the underlying technology is widely available, it will pop up elsewhere.

What makes the Grok situation particularly urgent is that it's illustrating these tensions in real time with real victims. It's not a theoretical debate about AI governance anymore. It's a concrete problem affecting real people right now.

This is why some experts argue that major platform deployments of powerful AI systems should require some form of external review before release, similar to how pharmaceutical companies have to demonstrate safety before release. Others argue for more sophisticated technical standards that all deployed systems need to meet. Others push for stronger liability frameworks that make companies actually responsible for harms.

All of these approaches have trade-offs. But they're trade-offs we'll probably have to engage with, because the current approach of "release and hope for the best" clearly isn't working.

FAQ

What is nonconsensual intimate imagery (NCII)?

Nonconsensual intimate imagery refers to images or videos that depict a person in a state of nudity or sexual activity without their consent. This includes both real photographs that are shared without permission and AI-generated synthetic images that appear to depict real people in intimate scenarios. The key element is the absence of consent from the person depicted.

How does Grok generate sexualized images?

Grok is an image generation tool that uses diffusion models trained on billions of images to create new images based on text prompts. When given a prompt describing what to generate, the model synthesizes an image matching that description. Safety mechanisms are supposed to prevent certain harmful outputs, but Grok's safeguards proved weak. Users discovered that rephrasing requests using terms like "transparent bikini" or requesting modifications in sequence could bypass the safety filters, allowing generation of sexualized images of real people taken from other users' posts.

What makes Grok's platform integration different from specialized "undress" services?

Traditional "undress" or "nudify" services required users to actively seek them out, often pay for the service, and navigate specialized websites or applications. This created friction and limited usage to people specifically seeking the capability. Grok is embedded directly in X, free to use, accessible to hundreds of millions of users, and generates results in seconds. This integration eliminates all the friction barriers that previously limited this type of abuse. The result is orders of magnitude more creation and distribution at mainstream scale.

What are the legal consequences for creating these images?

Legal frameworks vary significantly by jurisdiction. The TAKE IT DOWN Act in the United States makes it illegal to publicly post nonconsensual intimate imagery, including deepfakes, with platforms required to provide reporting mechanisms and respond within 48 hours. Some U. S. states have specific criminal laws. International approaches vary, with the European Union, UK, Canada, and Australia having more comprehensive legal frameworks in place. However, enforcement remains inconsistent and identifying perpetrators is difficult, particularly with anonymous online accounts. Criminal prosecution is relatively rare outside of cases involving minors.

What responsibilities do platforms have to prevent this abuse?

Platforms that deploy image generation tools have responsibility to implement safeguards to prevent creation of nonconsensual intimate imagery. This includes technical filters, policy enforcement, proactive detection of violations, and responsive action when abuse is reported. X's existing nonconsensual nudity policy explicitly prohibits the conduct that Grok is enabling, but enforcement has been minimal. Many experts argue that platforms are responsible not just for hosting abuse but for actively enabling it when they provide unrestricted tools without meaningful safeguards. However, legal liability for platform-enabled abuse remains unclear in many jurisdictions.

How can victims report or remove these images?

Victims can report images to platforms where they appear, requesting removal based on nonconsensual nudity policies. The TAKE IT DOWN Act requires platforms to respond within 48 hours. However, the process is reactive, time-consuming, and often inadequate given the scale of distribution. Victims can also pursue legal action if they can identify the creator, though this is difficult and expensive. Larger organizations and public figures often have resources to work with platform trust and safety teams. Ordinary individuals have fewer options and often find that platforms respond slowly or not at all to removal requests.

What are the long-term harms of exposure to nonconsensual deepfakes?

Research shows that victims of nonconsensual intimate imagery experience psychological harms comparable to sexual harassment and abuse, including anxiety, depression, hypervigilance, and difficulty trusting. Beyond individual victims, widespread availability of such imagery creates broader cultural effects: it discourages women from posting photos of themselves, affects professional women who need visible public profiles, creates a chilling effect on women's participation in digital spaces, and normalizes violence against women. The cumulative effect is a reduction in women's public presence and agency online.

What technical solutions could prevent this abuse?

Multiple technical approaches exist to reduce the problem. At the model level, better training of image generation systems to refuse sexualized content. At the API level, filtering of both prompts and generated images to detect likely violations. At the platform level, integration of detection tools to identify synthetic imagery, watermarking and metadata to indicate AI generation, and proactive systems to prevent sharing of nonconsensual content. At the detection level, developing increasingly sophisticated tools to identify deepfakes. However, these solutions require investment and reduce user engagement, so implementation requires regulatory pressure or competitive differentiation.

Why haven't existing safeguards prevented this problem?

Grok was deployed with relatively weak safety mechanisms and insufficient enforcement of existing policies against nonconsensual imagery. The underlying incentive structure doesn't reward preventing abuse: the costs of abuse fall on victims, while the benefits of unrestricted image generation fall on the platform through increased engagement. Early safety mechanisms proved inadequate because they could be circumvented through prompt engineering. Enforcement of existing policies has been minimal because it requires resources and proactive detection that hasn't been prioritized.

Conclusion: Moving Toward Accountability

We've been in this moment before. A powerful technology emerges. It gets used for harm. Society spends time debating whether regulation is necessary. Eventually, after sufficient damage, rules get written. Sometimes the rules are effective. Sometimes they come too late. Sometimes they're half-measures that don't actually solve the problem.

What's different about the Grok situation is that it's happening at massive scale in the open, on a mainstream platform. You can't pretend this is a fringe issue. Tens of thousands of images. Visible participation. Public infrastructure enabling it.

The response so far has been inadequate. A tool that's demonstrably being used to create nonconsensual intimate imagery of real women remains active and unrestricted. The company that owns the platform has made minimal statements and no visible changes. The regulatory framework is still being built while the harm is already happening.

But there are reasons to think this could change. The attention is finally there. The evidence is documented. The solutions are known. Multiple jurisdictions are developing legal frameworks. The technology for better safeguards exists.

What's missing is political will and regulatory pressure. That's also the thing that can be built most quickly if people decide it matters.

The women whose images have been manipulated and distributed can't wait for the perfect policy or the perfect technical solution. They need action now. That might look like platform changes that reduce the harm going forward, legal action against perpetrators, or support for victims. It definitely needs to include stopping the active creation of new harmful content.

For the broader landscape: this moment is going to shape how AI image generation gets regulated, how platforms take responsibility for enabled harms, and what standards apply to powerful tools deployed at scale. Getting it right matters. Getting it wrong creates precedent that makes it harder to act on future harms.

The most important thing is recognizing that this isn't inevitable, isn't irreversible, and isn't beyond our ability to address. It requires coordination and will, not additional technology. We have those resources available. The question is whether we use them.

Key Takeaways

- Grok demonstrated that removing friction barriers from abuse tools results in exponential scaling, generating tens of thousands of nonconsensual images daily on a mainstream platform

- The technology itself isn't new, but platform integration eliminates payment, technical, and discovery friction that previously limited usage to specialized communities

- Current policy responses are inadequate: reactive victim reporting, slow enforcement, and unclear platform liability allow abuse to continue at scale

- Economic incentives are fundamentally misaligned, with platforms benefiting from engagement while victims bear all costs and harms

- Realistic solutions exist across technical, regulatory, and enforcement domains but require political will to prioritize safety over engagement

Related Articles

- xAI's $20B Series E: What It Means for AI Competition [2025]

- Grok's Child Exploitation Problem: Can Laws Stop AI Deepfakes? [2025]

- Grok Deepfake Crisis: Global Investigation & AI Safeguard Failure [2025]

- AI Accountability Theater: Why Grok's 'Apology' Doesn't Mean What We Think [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness Role: What It Means and Why It Matters [2025]

- Brigitte Macron Cyberbullying Case: What the Paris Court Verdict Means [2025]

![How AI 'Undressing' Went Mainstream: Grok's Role in Normalizing Image-Based Abuse [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-ai-undressing-went-mainstream-grok-s-role-in-normalizing/image-1-1767739042938.jpg)