How Donghai Became the Crystal Capital: China's $5.5B Livestream Empire

Walk into the Big Purple Crystal warehouse in Donghai County, and you'll find something that shouldn't exist. Hundreds of imported amethyst geodes line the walls, their crystalline interiors splitting open like frozen screams. Some sit on carved wooden stands shaped like mythical creatures. Others rest in boxes stacked floor to ceiling. Behind an enormous amethyst geode desk sits Liu Junwen, the warehouse owner, in flip-flops, casually supervising what amounts to a small fortune in minerals.

This scene plays out thousands of times across Donghai every single day. What's remarkable isn't the crystal warehouses themselves. It's that a backwater county in eastern China's Zhejiang Province has somehow orchestrated control over a multibillion-dollar global industry that most Westerners don't even realize exists.

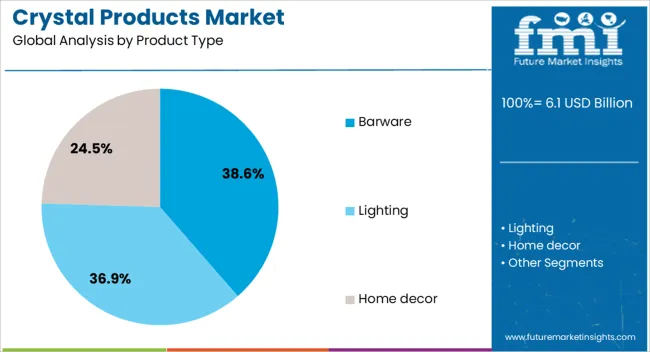

In 2023, Donghai's crystal trade generated an estimated $5.5 billion in revenue. About 300,000 people—roughly a quarter of the county's entire population—work directly in the crystal business. They're dealers, wholesalers, livestreamers, gemologists, cutters, factory managers, exporters, and logistics coordinators. Together, they've built a supply chain so efficient and interconnected that the crystals in your local yoga studio's gift shop, the quartz on your therapist's reception desk, and the citrine in that overpriced tourist trap in Tulum almost certainly passed through Donghai's warehouse network.

This is a story about how a poor agricultural village transformed itself into a global powerhouse. But it's not the story Western policymakers usually tell about China's rise. It wasn't engineered from the top down by government planners. It emerged from the bottom up, driven by rural entrepreneurship, desperation to escape poverty, and an almost feverish obsession with spotting the next market opportunity before your neighbor does.

TL; DR

- Donghai County controls over $5.5 billion of global crystal trade, with 300,000 residents working directly in the industry

- Livestreaming transformed crystal retail, with 24/7 broadcasts allowing sellers to reach global audiences in real-time

- The model emerged from poverty, not government planning—rural families saw crystal as an escape route from subsistence farming

- Information travels at lightning speed, creating boom-bust cycles where margins evaporate overnight

- Quality control remains a persistent challenge, as demand outpaces the ability to authenticate crystals at scale

- The Western obsession with wellness drives demand, making Donghai's crystals essential inventory for yoga studios, therapists, and new age retailers worldwide

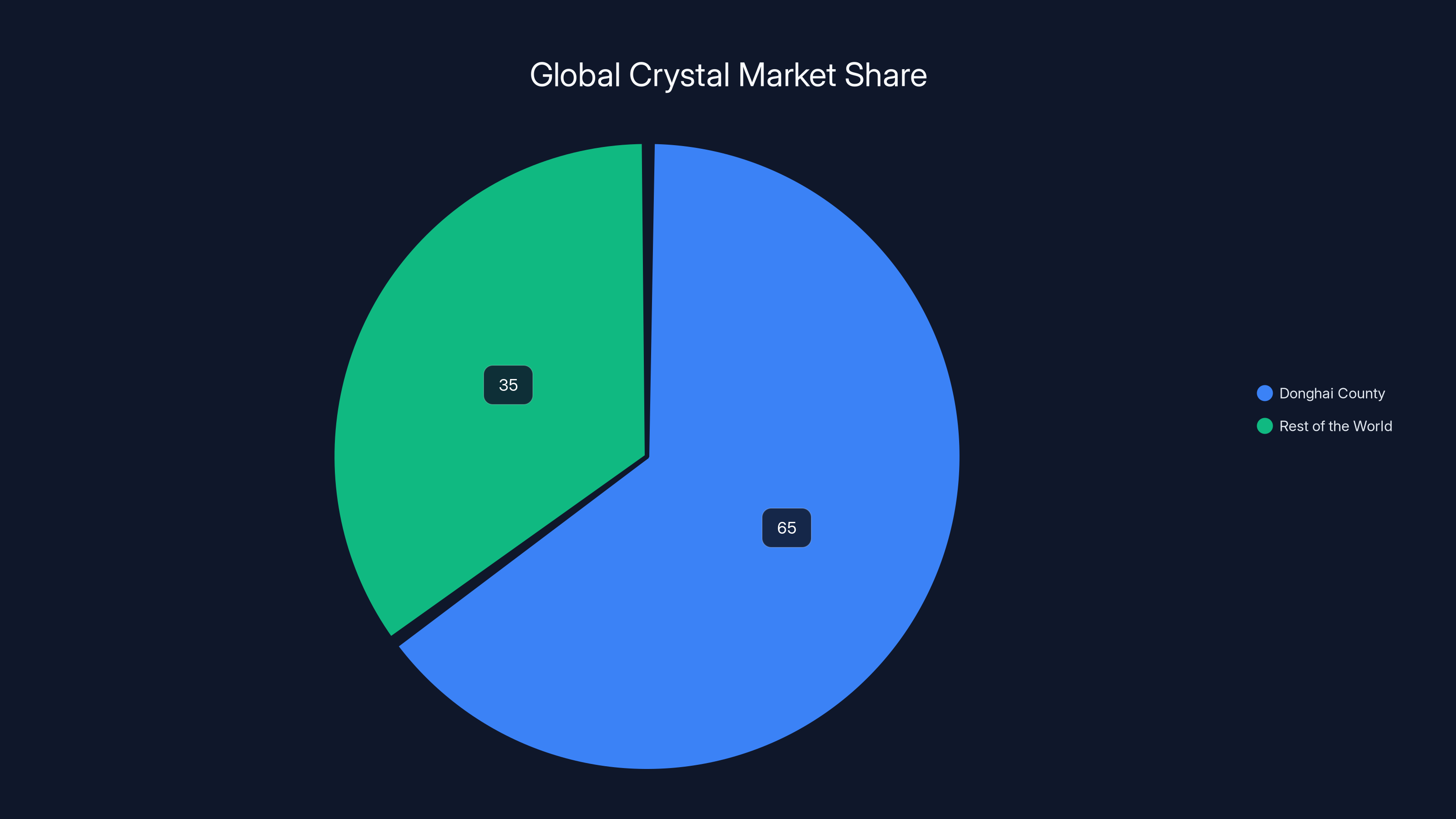

Donghai County controls approximately 60-70% of the global crystal trade, highlighting its significant influence in the market.

The Geological Fortune That Started It All

Donghai didn't become the world's crystal capital by accident. The county sits on the Tan-Lu fault line, a massive geological formation that stretches along China's eastern coast. Over millions of years, tectonic activity created fractures and cavities in the bedrock. Silica-rich fluids percolated through these spaces, slowly crystallizing into deposits of clear quartz, amethyst, and other mineral formations.

For generations, Donghai's farmers found crystals in their fields while plowing. They'd dig them up, polish them, and turn them into simple jewelry and ornaments. This wasn't a sophisticated industry. It was survival. Farmers needed to make use of what they found.

When the Communist Party took power in 1949, everything changed. The central government recognized quartz as strategically valuable—useful for optical lenses, electronics, and precision instruments. Commercial crystal mining was banned. Instead, the government built a state-controlled extraction and processing workforce in Donghai. This was part of the planned economy.

But here's the crucial detail most people miss: even under central planning, Donghai developed expertise. Families learned how to extract crystals. Workers learned how to cut, polish, and grade stones. The infrastructure was built. The knowledge was distributed across thousands of households.

When Mao Zedong died in 1976, even his funeral reflected Donghai's importance. His body was placed in a transparent coffin made from the finest Donghai quartz. The central government was literally announcing to the world: this county's minerals matter.

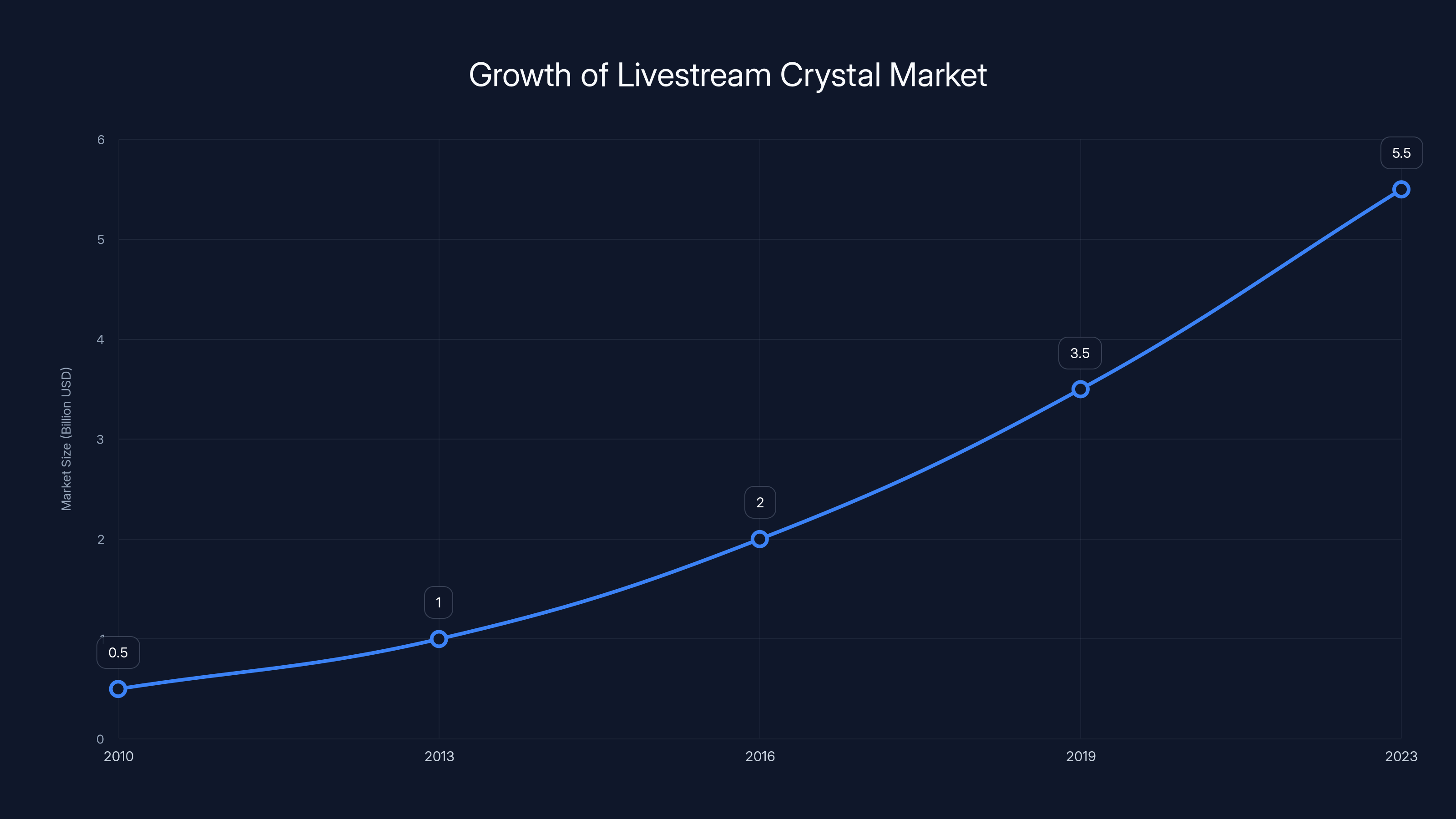

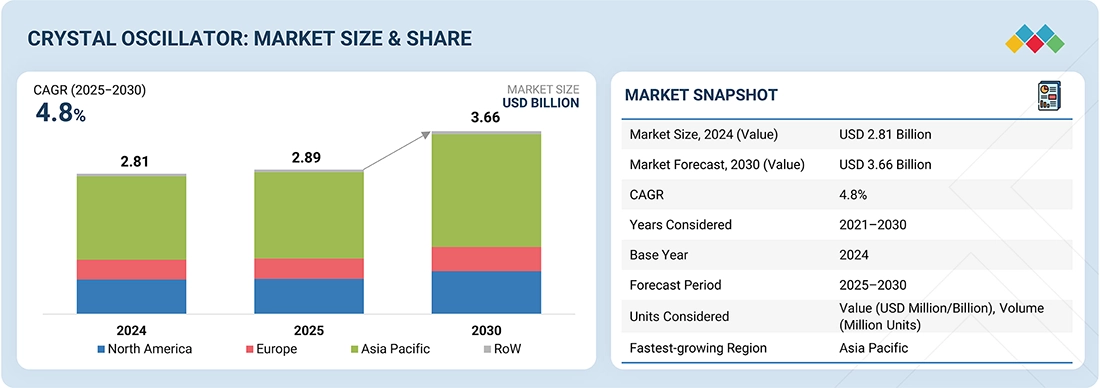

The livestream crystal market has grown significantly, reaching an estimated $5.5 billion in 2023, driven by direct consumer engagement and global interest in wellness culture.

Rural Desperation Meets Market Opportunity

After Mao's death, Deng Xiaoping took power and made a decision that would reshape not just Donghai, but rural China entirely. He began loosening the government's grip on the economy. In 1978, the reform process accelerated. Suddenly, rural families had permission to start small, independent businesses called township and village enterprises.

No one expected what happened next. These scrappy rural ventures grew explosively. By the early 1980s, Deng himself was amazed by the results. "Every year, township and village industries achieved 20 percent growth," he reflected to a group of journalists. "This was not something I had thought about. Nor had the other comrades. This surprised us."

Rural China was desperately poor. Decades of collectivized farming had left incomes stagnant. Farmers earned barely enough to survive. Suddenly, they had permission to be entrepreneurs. They looked around for anything they could leverage—geographic advantages, inherited skills, available resources—and turned them into businesses.

The examples are wild. Xuchang capitalized on its history of making hairpieces for opera performers and on the willingness of rural women to sell their hair. It became the world's wig manufacturing hub. Zhuangzhai, positioned near groves of paulownia wood (prized in Japanese cremation ceremonies), became the world's largest coffin exporter to Japan. Qiaotou became the button-making capital of the world after three brothers found discarded buttons in a gutter and decided to resell them.

Donghai already had two major advantages: geological deposits of crystal and a population that knew how to extract and work with them. But the county needed entrepreneurs willing to experiment and take risks.

That's when Wu Qingfeng and people like him started making waves. A former editor at the Donghai Crystal Museum who now teaches entrepreneurship boot camps, Wu witnessed the transformation firsthand. In the late 1980s, local artisans started modifying washing machine motors so they could polish crystal necklaces. Previously, this was backbreaking manual labor. Suddenly, it was mechanized.

When raw crystal supplies couldn't keep up with growing demand, manufacturers got creative. They used glass from discarded beer bottles to make beads. The shortage became so severe at one point that restaurants and bars literally ran out of beer because so much glass was being recycled into crystal products.

The Crash and the Intervention

But explosive growth came with a cost. By the 1990s, illegal crystal mining was spiraling out of control. Unregulated digging caused roads to collapse. Houses sank. People were injured and killed in mining accidents. The environmental damage was accelerating.

Chinese media reported the crisis in detail. The situation became unsustainable. In late 2001, Donghai County officials made a bold decision: they cracked down on illegal mining operations. They implemented regulations. They restricted new mining licenses. For a moment, it looked like the crystal boom might be over.

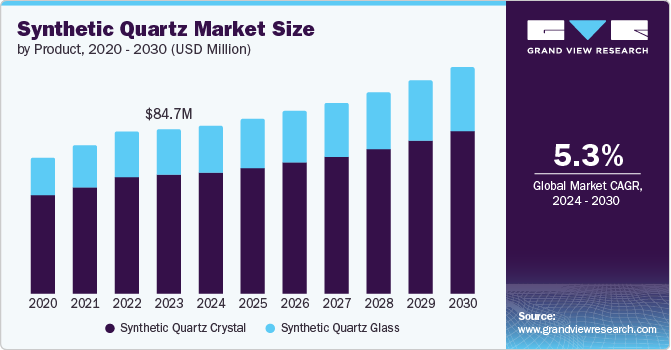

Instead, something more interesting happened. The restriction on raw materials forced the industry to evolve. Manufacturers couldn't rely on cheap, abundant domestic crystals anymore. They started importing high-quality amethyst, citrine, and quartz from Brazil, Uruguay, Zambia, and Colombia. They imported raw materials from anywhere in the world, then added value through cutting, polishing, and design.

This pivot was crucial. It transformed Donghai from a raw-materials extraction center into a processing and distribution hub. The county had already developed the infrastructure, the expertise, and the supply chains. Now it positioned itself as the middleman between global mineral sources and global consumers.

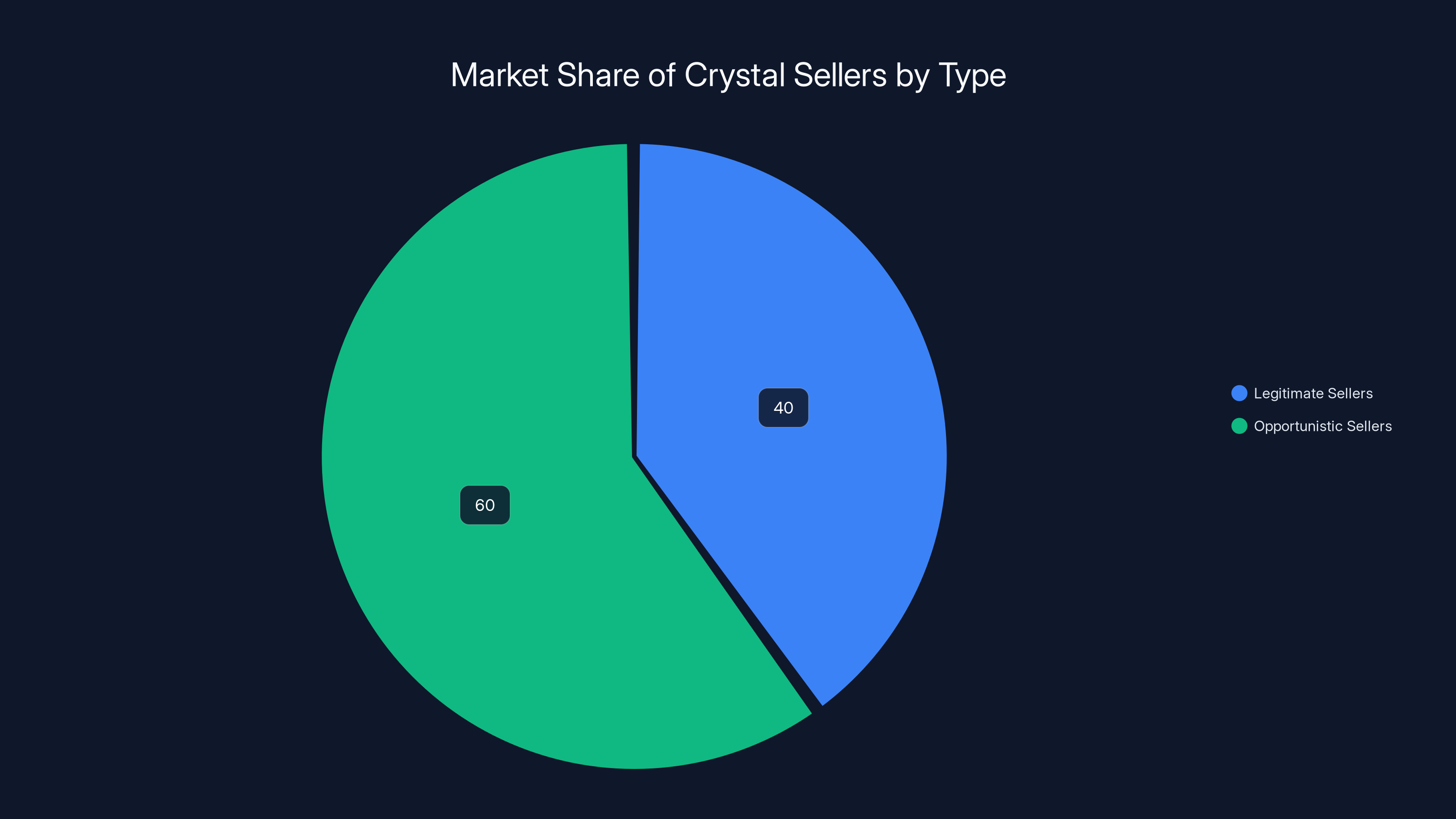

Estimated data suggests that opportunistic sellers make up a larger portion of the market compared to legitimate sellers, highlighting the quality control issues in Donghai's crystal market.

The Livestream Revolution That Changed Everything

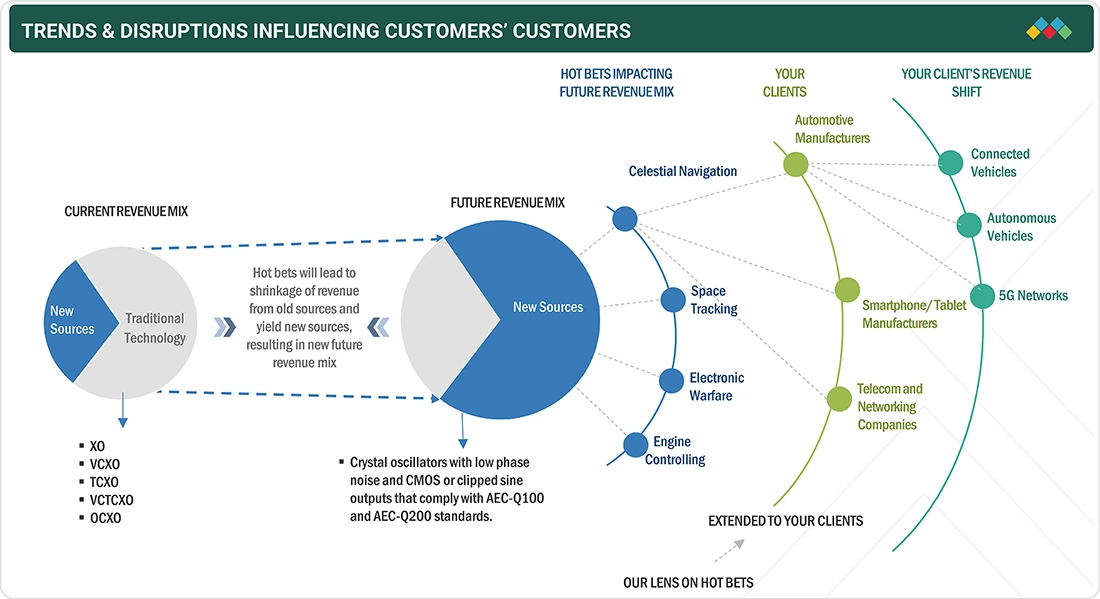

For decades, Donghai's crystal business operated through traditional wholesale channels. Dealers bought from manufacturers, wholesalers assembled orders, exporters shipped to retailers worldwide. It was efficient but slow.

Then came livestreaming. Platforms like Douyin (the Chinese version of Tik Tok) and later international livestream channels created a direct line between producers and consumers. Suddenly, a crystal dealer in Donghai could broadcast live from their warehouse 24 hours a day, show products in real-time, answer questions from viewers across the world, and process orders instantly.

The timing aligned perfectly with Western interest in crystal culture. Starting in the mid-2010s, wellness culture exploded in the U.S. and Europe. Crystals became central to this movement. People believed they had healing properties. Whether that was scientifically accurate didn't matter. The demand was real.

Livestream sellers in Donghai recognized the opportunity immediately. They could see American and European viewers tuning in. They could watch the chat flood with purchase requests. They could price dynamically based on viewer interest. If a batch of amethyst geodes was generating thousands of viewers, they'd raise prices. If interest dropped, they'd lower them.

The livestream model created multiple advantages. First, it eliminated middlemen. A manufacturer could stream directly to end consumers, capturing more margin. Second, it provided real-time market feedback. Sellers instantly knew what was selling and what wasn't. Third, it created a sense of urgency and social proof. Watching dozens of other viewers buy something makes it feel valuable.

But livestreaming also exposed Donghai's vulnerabilities. When a trend took off, information spread at lightning speed across the seller community. Everyone rushed to buy the same products and broadcast the same offerings. Suddenly, the market was flooded. Prices crashed. Sellers who bought inventory at the peak got stuck holding depreciating inventory.

This created a boom-bust cycle. A specific crystal type—say, purple amethyst clusters under 5 pounds—would start trending. Ten sellers would stream it. Hundred sellers would rush to stock it. Thousands of sellers would add it to their inventory. Within weeks, the market would be saturated. Prices would collapse. Many sellers would lose money.

This happened repeatedly. Bolivian amethyst. Brazilian citrine. Zambian emeralds. Each time, the cycle repeated. Opportunity emerged, everyone rushed in, the market crashed, and survivors waited for the next wave.

The Information Economy and Speed

One of the strangest aspects of Donghai's crystal market is how fast information travels. There's no formal communication system. Yet trends seem to spread organically across thousands of independent dealers within days.

Part of this is WeChat. Nearly every crystal dealer in Donghai is part of dozens of WeChat groups. Someone posts a photo of an unusual citrine specimen that's selling well. Within hours, hundreds of dealers have seen it. Within days, dozens of them have sourced similar specimens.

Part of it is livestream. Sellers watch competing streams constantly, tracking what's popular and what's not. They see a competitor's chat exploding over a new amethyst shipment. They immediately source similar material.

Part of it is pure proximity. Donghai is a county. Gossip travels through taxi drivers, warehouse workers, and restaurant servers. "Did you hear about Liu's new Brazilian citrine batch?" Suddenly, everyone's looking for Brazilian citrine.

The result is an information network that processes market signals faster than most stock exchanges. A new crystal type that's trending in Los Angeles gets reflected in Donghai prices within 48 hours. A drop in demand from Europe shows up in inventory levels within a week.

This speed creates opportunities for the fastest operators and disasters for the slow. Entrepreneurs who recognize trends early and move fast can build significant wealth. Those who follow conventional wisdom or wait too long lose fortunes.

One longtime dealer told us: "If you see a trend starting, you have maybe three days to make money. After that, everyone knows about it. After a week, the market crashes. The speed is insane."

The price of amethyst geodes has significantly decreased from

The Quality Control Problem Nobody Talks About

Here's the uncomfortable truth about Donghai's crystal market: quality control is a persistent disaster.

Crystals are difficult to authenticate at scale. Most buyers can't tell the difference between a genuine amethyst geode and a treated, dyed, or even synthetic substitute. Buyers can't tell if a crystal was heat-treated to enhance color. They can't tell if it was artificially irradiated. They can't reliably assess whether a crystal's purported metaphysical properties are real (spoiler: they're not) or if they're just marketing.

This creates perverse incentives. A dealer can buy low-grade Brazilian quartz for

Some Donghai manufacturers are legitimate. They source quality material, process it carefully, and stand behind their products. Many of these dealers have built trusted brands over decades.

But plenty of operators are opportunists. They'll buy whatever cheap crystals they can source globally, apply treatments, use misleading marketing, and offload inventory before reputation damage catches up with them.

Livestreaming has made this worse in some ways and better in others. Worse because livestream sellers face less scrutiny than brick-and-mortar shops. A viewer watching a livestream from 5,000 miles away can't physically inspect the product. They're relying entirely on video quality and seller reputation. Better because livestream creates a permanent record. If a seller sells fake crystals, reviews build up online and followers eventually migrate to more honest competitors.

The Chinese government has started tightening regulations around crystal selling. But enforcement is challenging. Many sellers operate semi-legally, in gray zones where regulations are ambiguous. The speed of the market outpaces the speed of regulatory response.

The Global Supply Chain Architecture

Most people imagine Donghai's crystal market as a simple operation: buy raw crystals, sell to consumers. The reality is far more complex.

Donghai functions as a hub in a massive global supply chain. Raw material flows in from mines across South America, Africa, Madagascar, and other regions. Manufacturers process this material using thousands of small workshops and factories. Wholesalers aggregate and organize inventory. Exporters handle international logistics. Retailers distribute to end consumers.

The sophistication is remarkable. Some dealers specialize in raw unpolished crystals. Others focus on polished geodes. Others create jewelry. Others specialize in high-end collector pieces. Others focus on bulk volume for gift shops. Some dealers work exclusively with Western retailers. Others sell directly to consumers via livestream.

The coordination happens through networks rather than formal organizations. Dealers know each other. They've worked together for years. Information flows through these relationships. Trust, reputation, and personal connections matter enormously.

But competition is ruthless. If one dealer can source the same product cheaper, they will. If another dealer can reach customers faster, they will. There's no loyalty. Just relentless pressure to improve, innovate, and undercut competitors.

This dynamic has actually made Donghai's crystal industry more efficient over time. Weak operators get eliminated. Effective operators scale up. Innovation is rewarded. The result is that crystals today are cheaper and more available globally than they were a decade ago.

A perfect amethyst geode that would have cost

The demand for crystals in Western markets has steadily increased since 2010, with a significant spike during the COVID-19 pandemic as consumers sought wellness products. (Estimated data)

The Boom-Bust Cycle and Survivor Bias

Every entrepreneur we spoke with in Donghai told essentially the same story with different details. They came from poverty. They saw an opportunity in crystals. They took a risk. They made money. Then the market crashed. They lost money. Then they made money again on a different product. Then another crash.

Donghai's business landscape is littered with people who didn't survive the cycles. They bought inventory at the wrong time. They couldn't adapt when trends shifted. They got stuck in the middle of a price crash with too much inventory and not enough cash flow.

The survivors develop an almost intuitive sense for what's about to happen. They watch livestream viewer engagement. They track which dealers are restocking. They feel the temperature of the market. When things feel too crowded, they exit. When things feel quiet, they start buying.

But even experienced operators make mistakes. Markets move faster than intuition. Unexpected events shift demand (a viral TikTok video, a celebrity mention, a new wellness trend). Competition appears from unexpected directions. Suppliers run out of material.

One dealer we spoke with made $200,000 profit on a Brazilian amethyst shipment in 2019. By 2020, he'd lost most of it trying to catch the same wave again. He sourced too much inventory. The market moved on. He was holding inventory when prices collapsed. It took him three years to recover.

This boom-bust pattern isn't a bug in Donghai's system. It's a feature. The cycles weed out inefficient operators and reward those who can adapt quickly. Over time, the system gets more efficient and more ruthless.

The Wellness Economy and Western Demand

None of Donghai's crystal boom would have happened without Western demand. The Chinese market for crystals exists, but it's relatively small compared to Western demand.

In the U.S. and Europe, crystal consumption accelerated dramatically starting in the mid-2010s. Wellness culture exploded. Yoga studios, meditation centers, therapy offices, and spiritual practitioners all began featuring crystals. Consumers bought them for personal use, believing they had healing properties. New age retailers stocked them.

The scientific evidence for crystal healing is essentially nonexistent. Controlled studies consistently show that crystals perform no better than placebos. But belief is powerful. If someone believes amethyst reduces stress, then amethyst reduces their stress (through placebo effect).

Western demand for wellness products has been on an upward trajectory for years. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this dramatically. People stuck at home turned to wellness, meditation, and spirituality. Crystal sales spiked.

Donghai dealers recognized this opportunity and optimized for it. They learned which crystals appealed to Western customers. They learned which colors Western consumers preferred. They learned how to present crystals in ways that resonated with wellness messaging. Purple amethyst for stress relief. Clear quartz for clarity. Rose quartz for love.

The marketing is sophisticated. Livestream sellers show crystals in aesthetically pleasing arrangements. They talk about crystal properties using wellness language. They create a sense of community among viewers. They make crystal buying feel like joining a movement rather than purchasing inventory.

This marketing works. Western consumers willingly pay premium prices for crystals they believe in. A

Donghai's dealers have essentially plugged into Western consumer psychology and optimized their entire supply chain around it.

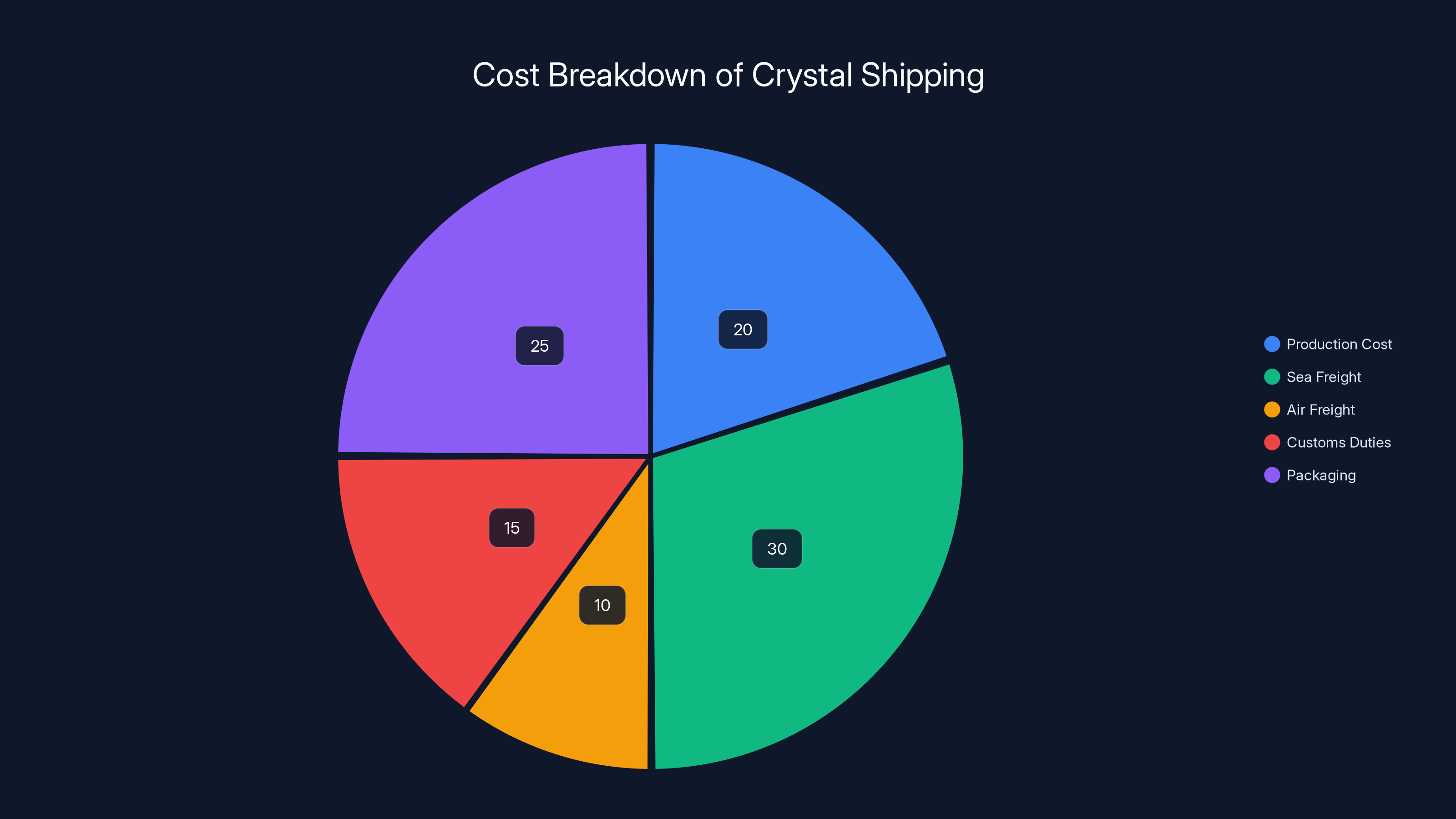

Estimated data shows that sea freight and packaging are significant contributors to the overall cost of shipping crystals, each accounting for a substantial portion of the total expenses.

Environmental and Labor Concerns

Donghai's rapid growth hasn't been without costs. Environmental concerns persist despite regulations. Mining operations can damage ecosystems. Crystal processing requires water and energy. Shipping from global sources and to global destinations creates carbon emissions.

Labor conditions in smaller workshops are sometimes questionable. Workers cutting and polishing crystals by hand earn low wages. Some workshops have poor safety standards. Workers inhale crystal dust, which can cause health problems.

There's also the ethical concern about crystal sourcing. Some crystals come from conflict zones or environmentally sensitive regions. Mining operations in certain countries have dubious labor practices or environmental track records.

Western consumers buying crystals rarely think about these issues. They see a beautiful amethyst geode and make a purchase. They don't trace it back to a mine in Zambia or a workshop in Donghai where a worker earned a few dollars cutting it.

More conscious consumers are starting to care about sourcing and labor practices. Some retailers are promoting "ethically sourced" crystals. But this remains a niche market. Most consumers are price-sensitive, not ethics-sensitive.

Donghai dealers are gradually becoming more aware of these concerns. Some are implementing better labor practices and environmental standards. But compliance remains inconsistent and enforcement is weak.

The Logistics Network That Powers It All

Physically moving billions of dollars worth of crystals globally is an engineering challenge. Donghai has built a sophisticated logistics network to handle it.

Crystals are fragile. They break easily in transit. They need proper packaging. Large geodes need custom wooden crates. Small stones need cushioned boxes. All of this adds weight and cost.

Shipping costs matter enormously in the crystal business. A pound of crystals might cost

Most crystals ship by sea freight. Ocean containers from Chinese ports to Los Angeles or Rotterdam take 20-30 days. This creates cash flow challenges. A dealer ships inventory, waits a month for arrival, waits another week for customs clearance, then finally gets paid.

Some dealers use air freight for high-value items or time-sensitive shipments, but this is expensive and rarely economical for bulk crystal orders.

The freight forwarding industry in Donghai has become specialized. Some companies handle nothing but crystal shipments. They know the best routes, the most reliable shipping lines, the most cost-effective consolidation strategies. Their expertise is worth significant money.

Customs clearance is another challenge. Crystals move between countries. Import duties apply. Documentation must be correct. Dealers have developed relationships with customs brokers who know how to navigate bureaucracy.

Digital Platforms and the Livestream Ecosystem

Livestreaming is the distribution technology that enabled Donghai's global explosion. But it's also created new challenges and opportunities.

Douyin (Chinese TikTok) is the primary platform where crystal sellers build audiences. Sellers create accounts, start broadcasting, and gradually attract followers. Successful streamers build audiences of thousands or tens of thousands of viewers. When they go live, thousands of people tune in simultaneously.

International livestream platforms like Instagram Live and Facebook Live have also become important. Western viewers can watch Donghai sellers in real-time, even though there's often a 12-hour time difference.

The livestream format creates advantages. Sellers can show products from multiple angles. They can answer questions live. They can process orders in real-time. They can create urgency ("only 5 of these left").

But it's also created new problems. The barrier to entry is low. Anyone with a camera and internet connection can start a crystal livestream. This has led to massive competition and proliferation of low-quality sellers.

Algorithms determine which livestreams get promoted and which don't. Success depends partly on product quality and partly on gaming the algorithm. Sellers who understand how algorithms work can gain advantages. Those who don't struggle.

Platforms have started cracking down on misleading product claims and fraud. But enforcement remains inconsistent. Many sellers operate in gray areas where rules are unclear.

The most successful crystal streamers have become micro-celebrities. They have personal followings. Viewers trust them and return repeatedly. This creates loyal customer bases that are somewhat insulated from competition.

Market Saturation and the Search for New Frontiers

Donghai's crystal market has been growing for decades, but growth rates are slowing. The market is becoming saturated. Western consumers already have access to cheap crystals. Further growth requires either expanding into new geographic markets, creating new products, or convincing existing customers to buy more.

Some dealers are exploring new frontiers. They're sourcing rarer minerals that command higher prices. They're focusing on high-end collector markets. They're creating specialized products (crystal jewelry, home décor, metaphysical tools). They're exploring emerging markets like India, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.

There's also interest in moving upmarket. Instead of selling generic amethyst geodes to gift shops, sellers are creating premium products for luxury wellness markets. Boutique retailers in Los Angeles and New York are willing to pay significantly more for ethically sourced, authenticated, beautifully presented crystal products.

But these strategies face challenges. High-end markets are smaller. Premium products require higher quality control and authentication. Emerging markets have different consumer preferences and logistics challenges.

The easiest path remains what's already working: supply Western wellness retailers and consumers with affordable crystals through livestream and e-commerce channels. But as more dealers pursue this path, margins compress and competition intensifies.

The Human Stories Behind the Numbers

Statistics tell part of Donghai's story. But the real story is human. It's about people who escaped poverty through hustle and luck. It's about people who built businesses from nothing. It's about people who lost everything and rebuilt. It's about communities that transformed themselves.

Liu Junwen, the warehouse owner, grew up in a village where nearly every household was impoverished. When he was young, being rich seemed impossibly distant. The idea that you could accumulate wealth through crystal trading seemed absurd. But he watched it happen. He saw other families escape poverty. He saw opportunities emerge.

He took a risk. He started trading crystals. He studied the market. He made mistakes and learned from them. He gradually built a business. Eventually, he owned a warehouse with hundreds of thousands of dollars in inventory.

Liu's story is common in Donghai. Nearly every successful dealer has a similar trajectory: born into poverty, saw an opportunity, took a risk, built a business, survived multiple crashes, gradually accumulated wealth.

But the risks were real. Many people who took similar risks failed. They made bad decisions. They bought inventory at the wrong time. They couldn't adapt when markets shifted. They lost everything.

The survivors tend to be those who combined timing, intelligence, and adaptability. They spotted opportunities early. They understood market dynamics. They adjusted their strategies when conditions changed.

In many ways, Donghai's crystal market is a microcosm of Chinese capitalism. It shows how individuals with ambition and willingness to take risks can build wealth from nothing. It shows how markets reward innovation and punish complacency. It shows how information networks and competitive dynamics drive efficiency and growth.

It also shows the challenges: boom-bust cycles, quality control issues, environmental concerns, and labor challenges. These are real costs that often aren't reflected in transaction prices.

The Future of Donghai's Crystal Economy

What's next for Donghai's crystal market? Nobody knows for certain. But trends are visible.

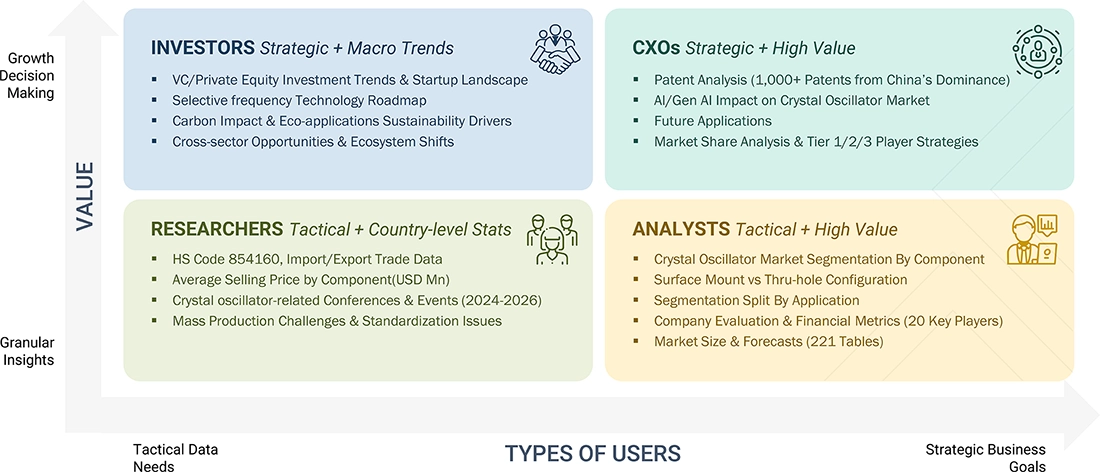

First, the market will likely become more consolidated. Weak operators will get eliminated. Strong operators will scale up. We'll see fewer, larger dealers with more market share, rather than thousands of small operators.

Second, quality and authentication will become increasingly important. Western consumers are becoming more conscious about sourcing and quality. Premium dealers will invest in authentication and certification. This will create a two-tier market: cheap commodity crystals and certified premium crystals.

Third, technology will continue to evolve. AI could improve product recommendations and personalization in livestreams. Blockchain could improve supply chain transparency and authentication. New platforms will emerge and old ones will decline.

Fourth, sustainability and ethics will matter more. Consumers are increasingly concerned about environmental impact and labor practices. Dealers who can certify ethical sourcing and sustainable practices will command premium prices.

Fifth, new product categories will emerge. Pure crystal sales have limits. But crystals incorporated into other products (jewelry, home décor, wellness tools, technology) have growth potential.

Sixth, geographic expansion will continue. Western markets are mature. Growth will come from new markets in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America.

Whatever happens, Donghai has established itself as the crystal capital. The infrastructure is built. The expertise is distributed. The networks are established. Even as specific trends and products change, this fundamental position is unlikely to shift dramatically.

For Western consumers buying crystals, Donghai's market will remain largely invisible. You'll buy a beautiful amethyst geode from a yoga studio or online retailer and never think about where it came from. You won't know about the Donghai dealer who sourced the raw material, the workshop that cut and polished it, the exporter who shipped it, or the countless people involved in the supply chain.

But that crystal almost certainly passed through Donghai. And the price you paid reflects the accumulated efficiency and expertise that this county has built over decades.

FAQ

What exactly is Donghai known for in the global crystal market?

Donghai County in Zhejiang Province, China is the world's largest hub for crystal processing, distribution, and sales. The county controls approximately 60-70% of the global crystal trade and generates an estimated $5.5 billion in annual revenue from crystal-related businesses. About 300,000 residents work directly in the industry, making crystal commerce the dominant economic activity. The county has transformed from a poor agricultural region into a global powerhouse by leveraging geological deposits of quartz and developing sophisticated supply chain networks.

How did livestreaming revolutionize Donghai's crystal market?

Livestreaming, particularly through platforms like Douyin (Chinese TikTok) and international services, eliminated traditional wholesale middlemen by allowing Donghai dealers to broadcast directly to consumers globally in real-time. Sellers can show products live, answer questions instantly, and process orders immediately from anywhere in the world. This created several advantages: sellers capture more margin by cutting out middlemen, they get instant feedback on what's selling, and they can create urgency through real-time viewer engagement. However, it also accelerated boom-bust cycles because information spreads instantly across the seller community, leading to rapid market saturation whenever a trend emerges.

Why is the crystal wellness market so important to Donghai's economy?

Western demand for crystals is driven by the wellness movement, which exploded starting in the mid-2010s and accelerated dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yoga studios, meditation centers, therapists, and spiritual practitioners feature crystals prominently. While scientific evidence for crystal healing properties is essentially nonexistent, consumer belief is powerful and drives purchasing. Western consumers view crystals as legitimate wellness products worth premium prices. This Western obsession with crystal-based wellness created enormous demand that Donghai's supply chains optimized to serve. Without Western wellness culture, Donghai's crystal market would be a fraction of its current size.

What are the main quality control challenges in the crystal market?

Crystals are difficult to authenticate at scale, especially for consumers buying online. Most buyers cannot reliably distinguish genuine amethyst from treated, dyed, or synthetic substitutes. They cannot tell if stones were heat-treated, artificially irradiated, or coated to enhance appearance. This creates incentives for opportunistic dealers to source low-grade material, apply treatments, and sell it at premium prices without detection. While some Donghai dealers are legitimate and produce quality products, others operate in gray areas. Livestreaming has made authentication more challenging because remote viewers cannot physically inspect products. The Chinese government has tightened regulations, but enforcement remains inconsistent and often lags behind the fast-moving market.

How does Donghai's crystal supply chain actually work globally?

Donghai functions as a hub in a complex global supply chain. Raw crystals flow in from mines across South America (Brazil, Uruguay), Africa (Zambia, Madagascar), and other regions. Multiple specialized operators process this material: manufacturers cut and polish, wholesalers aggregate inventory, exporters handle international logistics, and retailers distribute to end consumers. Crystals ship primarily by sea freight (20-30 day transit times), creating cash flow challenges. Specialized freight forwarders in Donghai optimize shipping costs and handle customs clearance. The system is sophisticated enough that a

What are the boom-bust cycles that characterize Donghai's crystal market?

Donghai's crystal market moves through rapid boom-bust cycles. When a specific crystal type (Brazilian amethyst, Zambian citrine, etc.) starts trending—often visible first in livestream viewership—information spreads instantly through the dealer community via WeChat groups, livestream monitoring, and local gossip. Hundreds of dealers rush to source similar inventory. The market floods with supply. Prices collapse rapidly. Dealers who bought inventory at the peak lose substantial money. Survivors develop intuitive skills for reading market temperature and exiting before crashes. The fastest, most adaptable operators profit during booms and minimize losses during crashes. This cycle repeats constantly, creating a ruthless environment where slow operators get eliminated.

What percentage of Donghai's population works in the crystal industry?

Approximately 300,000 residents of Donghai County work directly in the crystal business, representing roughly 25% of the local population. This includes dealers, wholesalers, livestreamers, gemologists, crystal cutters, factory managers, bead stringers, exporters, and freight agents. The crystal industry is the dominant economic activity in the county, making it fundamentally dependent on crystal market conditions. When the crystal market thrives, Donghai thrives. When crystals face challenges, the entire local economy faces challenges.

What environmental and labor concerns exist in Donghai's crystal industry?

Despite regulations implemented in 2001 to stop illegal mining, environmental concerns persist. Crystal processing requires water and energy. Mining operations can damage ecosystems. Shipping crystals globally creates carbon emissions. Labor conditions in smaller workshops are sometimes questionable—workers cutting and polishing crystals by hand earn low wages, and some workshops have poor safety standards. Workers inhale crystal dust, which can cause long-term health problems. Additionally, crystals from certain regions come from conflict zones or areas with dubious environmental and labor practices. Western consumers rarely think about these costs, focusing instead on price and aesthetics. The Chinese government is gradually tightening standards, but compliance remains inconsistent and enforcement is weak.

How is Donghai's crystal market expected to evolve in the coming years?

Experts anticipate several trends: market consolidation as weak operators disappear and strong ones scale; increased focus on quality and authentication as consumers demand certified, ethically sourced crystals; technological evolution through AI-powered recommendations and blockchain supply chain transparency; growing emphasis on sustainability and ethical practices commanding premium prices; expansion beyond pure crystals into crystal-embedded products like jewelry and home décor; and geographic expansion into emerging markets (India, Southeast Asia, Middle East) as Western markets mature. The fundamental position of Donghai as the crystal capital is unlikely to shift, but the specific products, platforms, and consumer preferences will evolve significantly.

The story of Donghai County reveals something essential about how markets actually work. It's not top-down industrial policy that built the world's crystal capital. It's not government planning or strategic investment. It's rural entrepreneurs seeing an opportunity, taking risks, and competing ruthlessly to serve global demand. Thousands of individuals making millions of individual decisions created one of the world's most sophisticated supply chains, all optimized around a product that most people don't even know comes from a single county in China.

For Western consumers, crystals represent wellness, spirituality, and connection. For Donghai residents, crystals represent something different: a path out of poverty, a chance to build something, an opportunity to compete and win. These two narratives—the Western spiritual narrative and the Chinese hustle narrative—have become intertwined. They sustain each other. Without Western demand, Donghai's industry wouldn't exist at its current scale. Without Donghai's supply chain, Western consumers couldn't access affordable crystals.

This symbiotic relationship is likely to intensify. As Western interest in wellness continues to grow, demand for crystals will follow. As Donghai's supply chains become more efficient, prices will fall and accessibility will increase. More people will own crystals. More people will believe in their properties. More demand will flow back to Donghai.

It's a cycle built on belief, hustle, and global capitalism. Whether that's healthy, sustainable, or ethical is a separate question. But it's undeniably powerful.

Key Takeaways

- Donghai County controls 60-70% of global crystal trade worth $5.5 billion annually through decentralized networks of 300,000 independent operators, not top-down industrial policy

- Livestream technology eliminated traditional wholesale middlemen, allowing dealers to broadcast directly to global consumers 24/7 and respond to market demands in real-time

- Western wellness culture obsession with crystal healing created the demand that transformed a poor agricultural county into a global powerhouse in just a few decades

- Information networks spread market signals so fast that boom-bust cycles occur within weeks, creating ruthless competition where slow operators get eliminated and fast ones accumulate wealth

- The transformation illustrates how rural capitalism in China emerged from desperation to escape poverty rather than government planning, showing individual ambition as the driver of economic development

![How Donghai Became the Crystal Capital: China's $5.5B Livestream Empire [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-donghai-became-the-crystal-capital-china-s-5-5b-livestre/image-1-1768909350752.jpg)