Introduction: Where Abstract Math Meets Practical Computing

Here's something that'll blow your mind: the most abstract mathematics imaginable—the study of infinite sets and their bizarre properties—might just be the key to solving concrete problems in computer networks and algorithms. Sounds backward, right?

For decades, descriptive set theory lived in its own isolated corner of mathematics. Researchers studied infinities that other mathematicians actively avoided. They grappled with sets so pathologically complicated that they couldn't be measured by any reasonable definition. The field felt divorced from practical applications, interesting mainly to philosophers and logicians who enjoyed thinking about fundamentals nobody else cared about.

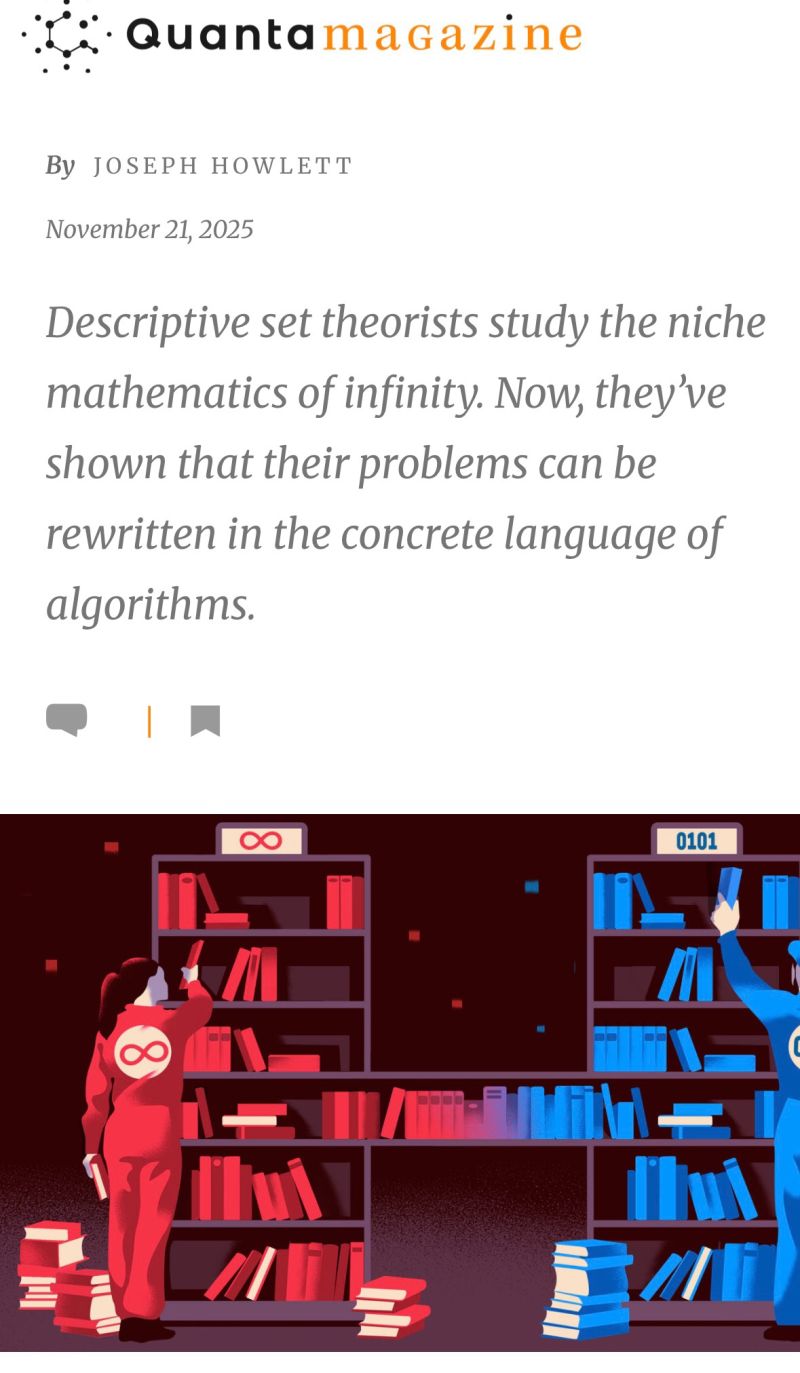

Then something unexpected happened. In 2023, a mathematician named Anton Bernshteyn published research showing that problems about certain infinite sets could be perfectly rewritten as problems about how networks of computers communicate and coordinate. This wasn't a loose analogy or a suggestive metaphor. These problems were genuinely equivalent. You could translate between the two languages and move solutions back and forth.

The implications spiraled outward. Descriptive set theorists could suddenly borrow powerful algorithms from computer science. Computer scientists discovered they could apply insights from set theory to prove new theorems about distributed networks. Researchers on both sides started collaborating across disciplines that had never directly spoken to each other.

This article explores that remarkable bridge: how the study of infinity connects to algorithms, what it means for both fields, and why mathematicians are genuinely shocked that the connection exists at all.

TL; DR

- Descriptive set theory studies infinite sets and their measurability properties, creating hierarchies of increasingly complex infinities

- Bernshteyn's 2023 breakthrough showed these problems directly translate to questions about how distributed computer networks communicate

- The translation is perfect, not approximate, allowing direct transfer of solutions between mathematics and computer science

- Practical impact: Computer scientists now use set theory techniques to analyze networks; set theorists use algorithms to reorganize their field

- Future implications: This bridge could solve open problems in both domains and reshape how we think about computation and infinity

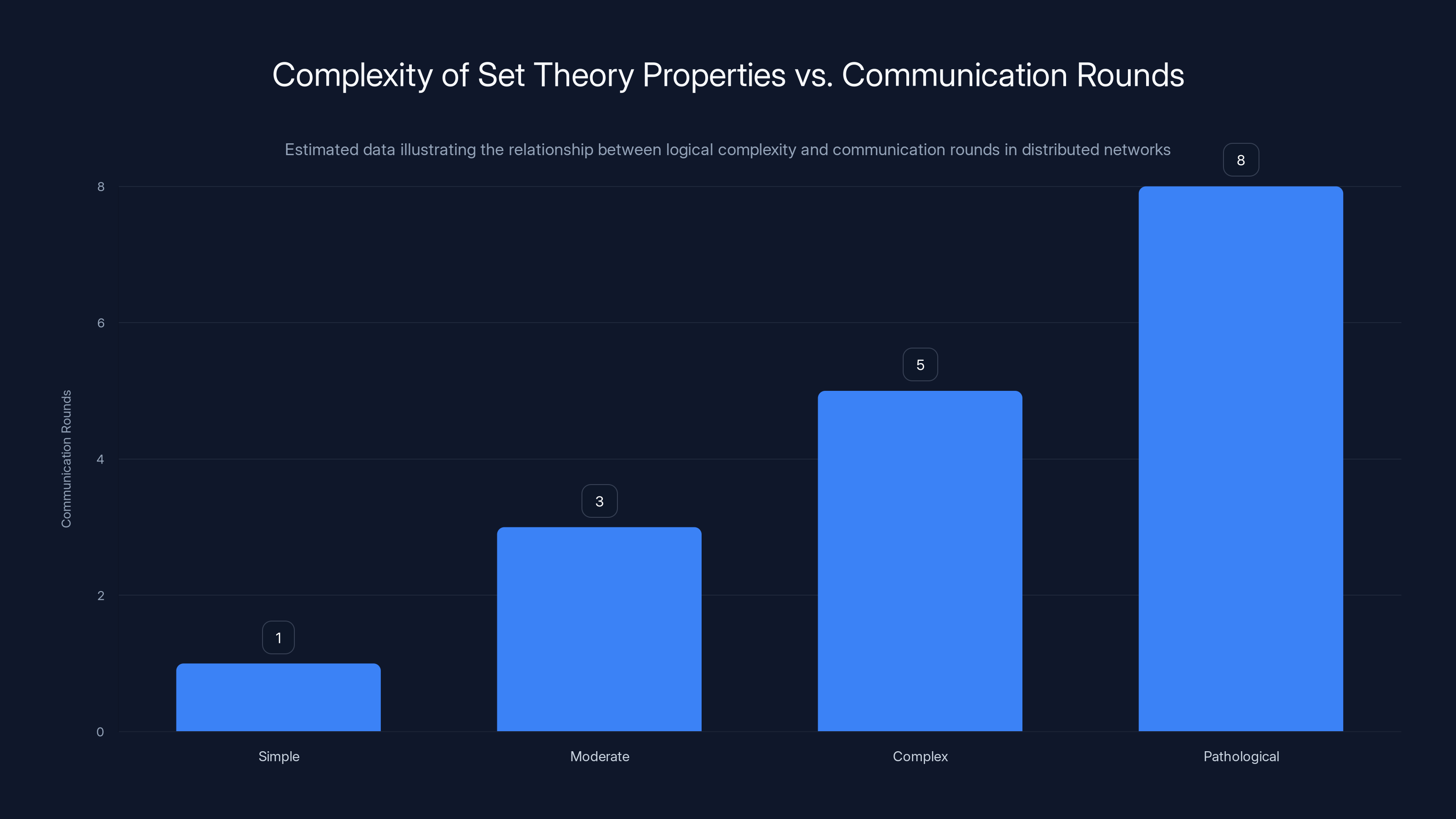

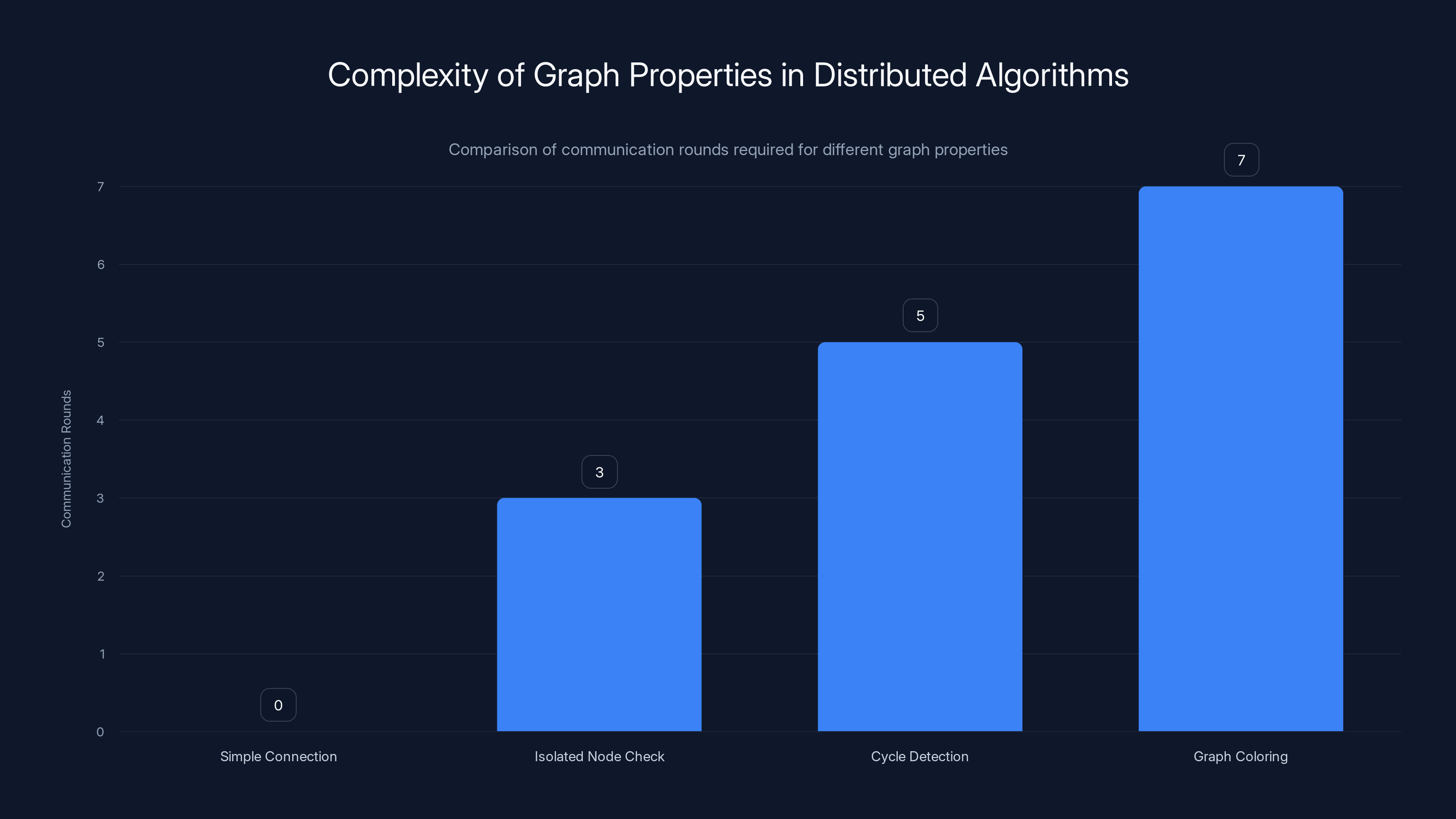

The complexity of defining a property in set theory directly correlates with the number of communication rounds needed in distributed networks. Estimated data shows this relationship.

What Is Descriptive Set Theory?

Descriptive set theory might sound like the study of, well, describing sets. In a sense, it is. But what makes it genuinely weird is what kinds of sets it describes.

Most mathematicians work with sets they can easily construct. You can build the set of all prime numbers by checking which numbers have exactly two divisors. You can define the set of all solutions to a polynomial equation using algebra. These sets are relatively tame. They follow intuitive rules. You can measure them, analyze them, and prove things about them without much fuss.

Descriptive set theorists study the mess behind the comfortable fence. They ask: what about sets that require infinitely complicated definitions? What about sets so intricate that no finite procedure can describe them? What about infinities layered on top of infinities?

The field originated with Georg Cantor in the 1870s. Cantor proved something that made mathematicians profoundly uncomfortable: infinity comes in multiple sizes. The set of whole numbers is infinite. The set of all real numbers is also infinite. But they're not the same size of infinity. The real numbers are a "bigger" infinity than the whole numbers.

This created conceptual chaos. If infinities can be different sizes, what does size even mean? How do you compare infinities? What lies between them?

Mathematicians responded by developing a framework to organize these infinities. They created hierarchies based on how "complicated" a set is to construct. At the top sit sets you can define easily—closed rectangles on a plane, for instance. As you descend the hierarchy, sets become increasingly pathological. Near the bottom sit sets so impossibly tangled that you can't measure them at all, no matter what reasonable definition of "measurement" you use.

This organizational system became descriptive set theory's core project: mapping the landscape of infinite sets, arranging them by complexity, and understanding which mathematical tools work on which sets.

For most of the 20th century, the field developed in isolation. Only specialists studied descriptive set theory seriously. Other mathematicians would note its existence, appreciate its logical rigor, then move on to fields with more obvious applications. The prevailing assumption was that studying infinities disconnected from reality was inherently impractical.

Yet a small community persisted. They published papers, trained students, discovered deeper connections within their framework. And they waited.

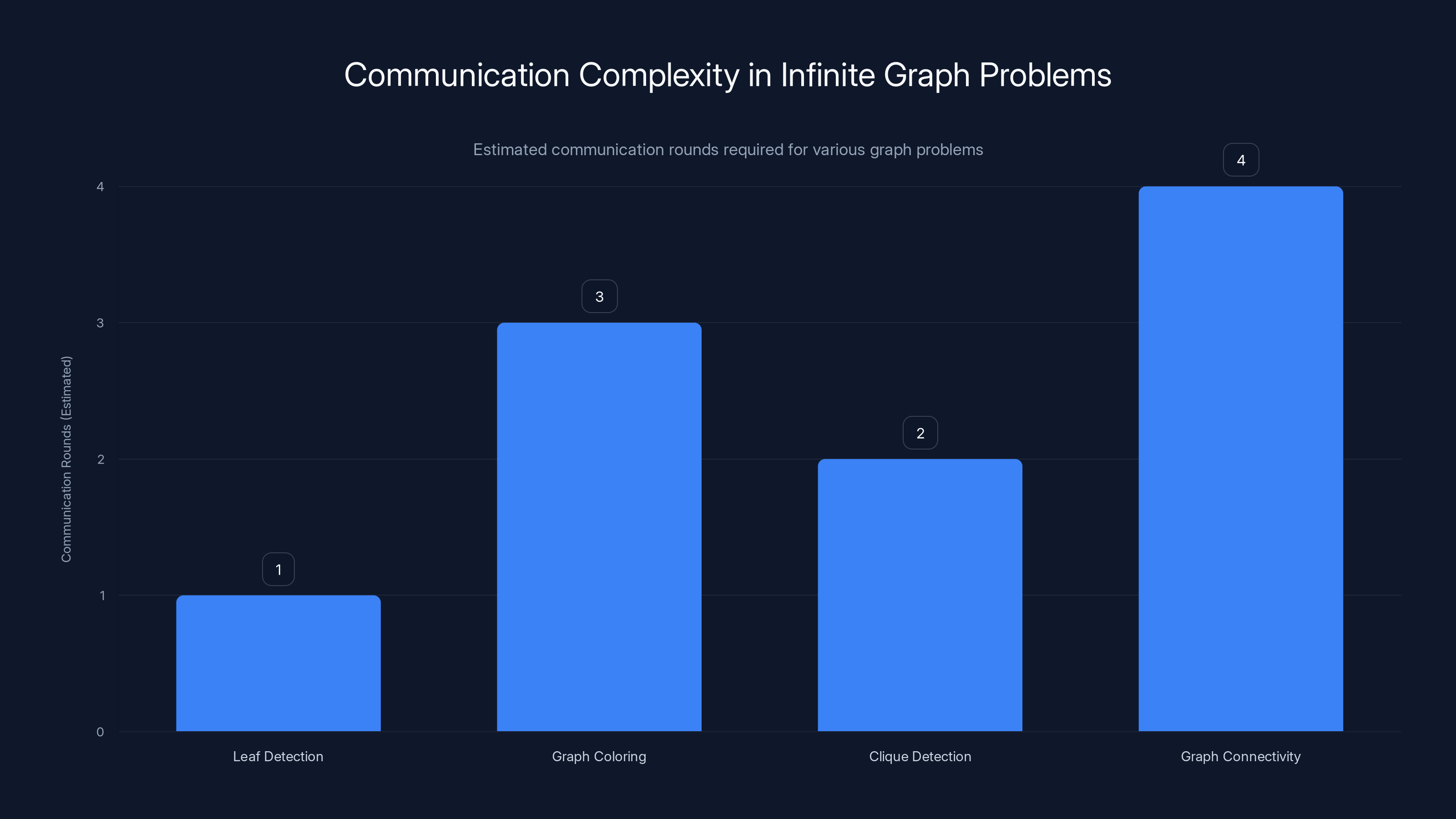

Estimated data: Different graph problems require varying communication rounds based on their logical complexity, with graph connectivity being the most complex.

The Problem: Infinite Graphs and Network Communication

Now zoom to computer science. Modern computing increasingly involves distributed systems—thousands or millions of computers working together across networks, coordinating actions, sharing information.

When computers work in a distributed system, they can't instantly know what every other computer is doing. Information takes time to travel. Computers fail unexpectedly. Messages get delayed or duplicated. The challenge becomes: how do you make decisions when you don't have complete information?

Computer scientists study this using graph theory. Each computer is a node in a graph. Each network connection between computers is an edge. The graph structure represents the communication topology. The problem then becomes: given this network topology, what can you compute reliably?

This might sound abstract. But it's profoundly practical. Cryptocurrencies rely on consensus algorithms running across thousands of nodes where participants don't trust each other. Cloud computing clusters need algorithms that tolerate some nodes failing simultaneously. Social networks analyze graph structures with billions of nodes to recommend connections.

For finite graphs—networks with a limited number of nodes—computer scientists had developed reasonably good techniques. But what about infinite graphs? What about networks with infinitely many separate components, each containing infinitely many nodes?

This scenario isn't purely theoretical. Some systems generate infinite graph structures. Certain mathematical models require analyzing infinite networks. And solving problems for infinite graphs often provides insight into the finite case.

Here's where things get interesting: nobody had a systematic way to think about infinite graphs. Computer scientists had intuitions and tricks. But they lacked the organizational framework that let them say things like: "This problem requires networks with this specific communication structure" or "Problems of this type automatically break down into these subproblems."

Meanwhile, descriptive set theorists had spent decades building precisely that kind of organizational framework. They'd created entire hierarchies for classifying mathematical objects by complexity. The hierarchy was designed for infinite sets, sure, but what are infinite graphs except infinite sets of nodes connected by relations?

The connection wasn't obvious. Set theorists used the language of logic—predicates, quantifiers, definability. Computer scientists spoke in algorithms—message passing, state machines, computational complexity. The vocabularies were completely different. The concerns seemed orthogonal. Yet Bernshteyn's work would show the languages described the same underlying structures.

The Breakthrough: Bernshteyn's Translation

Anton Bernshteyn didn't set out to revolutionize both fields simultaneously. He was just following interesting mathematical threads.

Bernshteyn studied graphs where nodes are organized into infinitely many separate components, each infinitely large. In descriptive set theory, you can categorize sets based on how "definable" they are. You need formal logic to construct them, use increasingly complex logical formulas to describe them, and these descriptive complexities stack into layers of a hierarchy.

Bernshteyn realized something remarkable: the hierarchy of descriptive complexity in set theory mapped perfectly onto the hierarchy of what you could compute on infinite graphs with certain communication constraints.

Here's the essential insight: imagine you have an infinite network where computers can only communicate with their immediate neighbors. You want to know if the network has a certain property. You can't check the whole infinite network directly. So you create an algorithm that runs locally on each node and sends messages to neighbors. Based on the messages received and local computation, each node makes a decision.

The "difficulty" of this distributed algorithm—how many rounds of communication you need, how complex the local computation must be—corresponds exactly to the logical complexity required to define that property in the language of descriptive set theory.

Let's make this concrete. Some properties of graphs are easy to verify locally. For instance: "Is this node connected to at least one other node?" A local algorithm can check this in zero communication rounds—a node just checks its own direct connections.

Other properties are harder. "Does this graph have any isolated nodes?" requires global knowledge. You need information about all nodes simultaneously. In distributed computing, you need more communication rounds. In descriptive set theory, you need more complex logical formulas.

Bernshteyn proved that these difficulties aligned precisely. The logical hierarchy of descriptive set theory didn't just loosely correspond to computational difficulty. They were mathematically equivalent. You could translate any problem from one language to the other without losing information.

This wasn't a surprising coincidence. It was a deep structural alignment in mathematics itself.

The implications cascaded immediately. Set theorists could suddenly borrow techniques from theoretical computer science. Algorithms that worked on finite graphs could be reinterpreted as logical operations on sets. Conversely, computer scientists could apply decades of set-theoretic research to prove new things about distributed algorithms.

Václav Rozhoň, a computer scientist at Charles University in Prague, described the strangeness: "This is something really weird. Like, you are not supposed to have this." Two completely different disciplines, using different languages, asking different questions—and it turns out they're solving the same problems from different angles.

Estimated data shows that consensus issues and information delay are major challenges in distributed systems, impacting reliability and performance.

The Mathematical Hierarchy: Understanding Infinite Complexity

To appreciate Bernshteyn's breakthrough, you need to understand the descriptive hierarchy that set theorists had spent decades building.

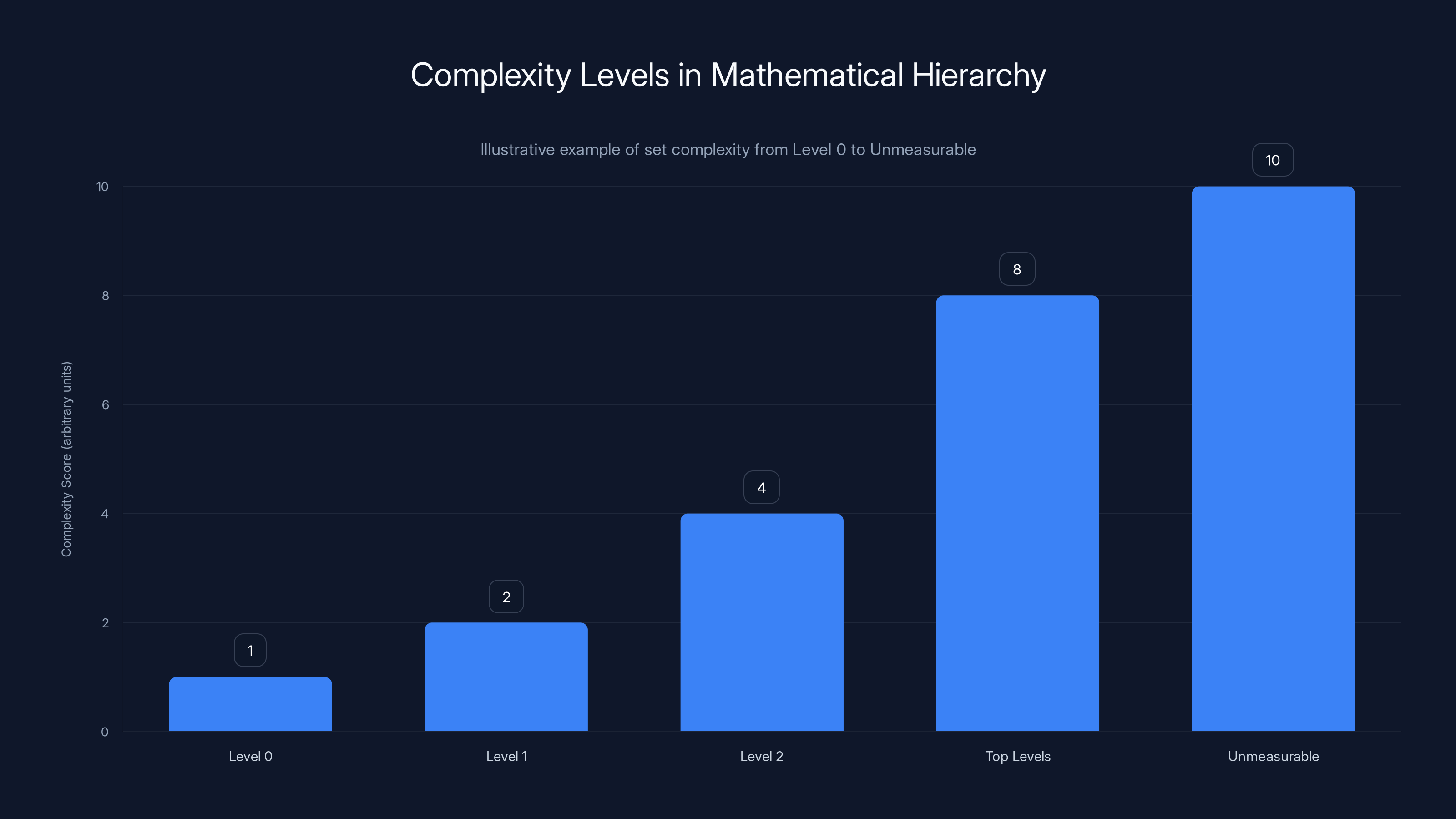

Set theorists organize infinite sets into layers based on how complicated their defining properties are. Think of it like organizing books in a library, where the shelving location tells you how difficult the book is to understand.

At the simplest level (call it Level 0) sit sets defined by basic logical statements. "All real numbers greater than 5 and less than 10." "All sets that are non-empty." These are straightforward. The defining property requires one simple condition.

At Level 1, sets require slightly more complex definitions. Maybe you need multiple conditions connected with "and" or "or." "All numbers that are greater than 5 and divisible by 3, or less than -10." Somewhat more intricate, but still manageable.

As you climb the hierarchy, the definitions become increasingly baroque. You need to say things like: "All sets that contain an element such that for every other element in some related set, there exists another element with property X." These spiral into nested logical structures that humans find nearly impossible to visualize.

At the top levels sit sets so impossibly complicated that you can define them, but barely. At the very bottom sit unmeasurable sets—sets so pathological that no consistent definition of "size" or "measure" can apply to them.

This hierarchy isn't arbitrary. It emerges naturally from how logical complexity compounds. Simpler formulas define simpler sets. More complex formulas define more complex sets. The hierarchy reflects something fundamental about mathematical structure.

The genius of the set-theoretic hierarchy is that it maps which tools you can use. Sets at the top layers are "nice." You can measure them, analyze them, apply powerful theorems to them. As you descend, sets become increasingly pathological. The tools that worked on top layers stop working. You need different approaches.

This organizational principle has applications far beyond pure set theory. Mathematicians working in probability theory, dynamical systems, or group theory often need to know if the sets they're studying are "nice" enough to measure. Descriptive set theorists act like librarians, determining where a given set belongs in the hierarchy and therefore what tools will work on it.

The Computer Science Translation: Distributed Algorithms and Communication

Now here's where Bernshteyn's translation becomes powerful. In distributed computing, you face similar hierarchies, but they're expressed in completely different terms.

Imagine you have a network of computers where each computer is a node in a graph. These computers can only talk to their immediate neighbors. They can't access global information. Yet somehow, they need to coordinate and make decisions.

This is called distributed local computation or LOCAL model computation in computer science. The challenge is: given limited local information, what problems can you solve?

It turns out, some problems are easy. "Count how many neighbors I have" is trivial—each node checks its local connections. This requires zero communication rounds.

"Count how many nodes are in the entire network" is hard. No node has that information. Even if nodes send messages to neighbors, and neighbors relay information, it takes many communication rounds to get global knowledge. Worse, in an infinite network, the rounds might never terminate.

"Is there any isolated node in the network?" falls somewhere in between. You need to gather information from all nodes somehow. In theory, with enough communication rounds, you could learn everything. But with infinitely many nodes, you might need infinitely many rounds.

The key insight: the number of communication rounds needed corresponds to the logical complexity of the property being computed.

A property defined by a simple logical formula (what set theorists call "first-order definable") requires few communication rounds in a distributed algorithm. A property requiring complex logical formulas needs many communication rounds. The correspondence is exact.

Bernshteyn's translation showed that these aren't just analogous. They're the same mathematical structure viewed from two perspectives:

- Set Theory Perspective: How complex a logical formula is required to define a set

- Computer Science Perspective: How many communication rounds are required to solve the problem on a distributed network

These aren't loosely related. They're mathematically identical.

This equivalence is profound. It means results from one field directly translate to the other. A proof technique used in set theory becomes an algorithm design strategy in computer science, and vice versa.

The chart illustrates the increasing complexity of set definitions as you move from Level 0 to Unmeasurable sets. Estimated data shows a progression from simple to highly complex logical structures.

Building the Bridge: How Translation Works Practically

Understanding the translation concretely requires looking at specific examples.

Take a simple property: "Does the network contain a node with no neighbors?" In distributed computing, this is called "detecting isolated nodes."

In set theory terms, you're describing a set: "all networks that possess the property of containing at least one isolated node."

Now, what's the logical complexity of this property? To verify it formally, you'd write something like:

That reads: "There exists a node such that for all other nodes, there's no connection between them."

In the descriptive set theory hierarchy, this property sits at a specific level—let's call it complexity level C.

In distributed computing, Bernshteyn's translation predicts: you need exactly C communication rounds to solve this problem in a network algorithm.

Why? Because the algorithm must first gather enough information from all nodes to verify the property. With isolated nodes, the algorithm needs to confirm that at least one node has no connections. In a network with infinite disconnected components, each containing infinitely many nodes, you might need multiple rounds just to ensure you've reached nodes from all components.

Let's trace through the algorithm:

Round 1: Each node sends a message to its neighbors saying "I'm here."

Round 2: Nodes that received messages in Round 1 send confirmation back. A node that sends in Round 1 but receives nothing in Round 2 is isolated.

Verification: If any node detected isolation in Round 2, the network has an isolated node.

This two-round algorithm solves the problem. The logical property describing it requires existential quantification over nodes and universal quantification over potential connections—complexity level C. The algorithm requires C communication rounds.

Not a coincidence. Structural correspondence.

Applications to Set Theory: New Organization of the Field

The bridge didn't just help computer scientists. Set theorists realized they could use algorithmic thinking to reorganize their entire field.

Descriptive set theory had traditionally arranged infinities primarily by logical complexity. But that wasn't the only useful way to think about them. Computer scientists had developed rich classification schemes based on what could be computed efficiently, what required exponential resources, what was inherently inefficient.

Bernshteyn and colleagues started asking: what if we reclassified infinite sets using computational complexity as the organizing principle?

Suddenly, questions that seemed abstract became practical: "Can you decide membership in this set efficiently?" "What resources does recognizing this property require?" "Is there a polynomial-time algorithm for this problem?"

These questions directly borrowed language from computer science. But when applied to infinite sets through the translation, they provided new insights into set-theoretic structure.

For example, some infinite sets had always seemed unrelated because they required different logical complexities. But from a computational perspective—using the bridge as translation—they sometimes required the same computational resources. This suggested an underlying similarity that logicians had missed.

This reorganization is ongoing. Researchers are actively working to rebuild descriptive set theory's conceptual framework using computational insights from computer science. Anush Tserunyan, who advised Bernshteyn early in his career, described the impact: "We've been working on very similar problems without directly talking to each other. It just opens the doors to all these new collaborations."

The field that seemed isolated and specialized suddenly became connected to decades of computer science research.

The complexity of verifying graph properties in distributed algorithms varies significantly, with simple connections requiring no communication rounds and more complex properties like graph coloring requiring multiple rounds. Estimated data.

Applications to Computer Science: Proving New Theorems About Networks

Meanwhile, computer scientists gained powerful tools for proving theorems about distributed networks.

One notorious open problem in distributed computing: are certain graph properties impossible to compute in any finite number of rounds? For some properties, you might need infinitely many rounds of communication to determine them conclusively. But proving this is hard.

Descriptive set theory provides machinery for proving such impossibilities. If a property has sufficiently high logical complexity, the translation guarantees you can't solve it in finite rounds. This transforms what seemed like a difficult algorithmic question into a manageable logical one.

Researchers like Václav Rozhoň started applying descriptive set theory techniques to problems that had resisted algorithmic approaches. The success rate surprised everyone. Problems that seemed intractable from pure computer science perspective often yielded to set-theoretic analysis.

For instance, proving lower bounds on communication complexity became more systematic. Instead of designing specific networks and analyzing them, researchers could use the hierarchy from set theory to argue: "This property requires complexity level X in the logical hierarchy. The translation shows you therefore need at least X communication rounds." Boom. Lower bound proved.

This acceleration of progress rippled through distributed computing research. The bridge wasn't just intellectually satisfying. It made solving concrete problems easier.

Graph Problems and Infinite Structures

The connection works especially well for infinite graph problems, which was Bernshteyn's original focus.

Consider a problem: "Does this infinite graph have any leaves?" (A leaf is a node with degree 1—only one connection.) In a finite graph, you'd check every node's neighbors. In an infinite graph, you can't enumerate all nodes. But you can use a distributed algorithm: have nodes report their degree to a central location, or use local computation to identify leaves without full global information.

The difficulty of this problem—how many communication rounds it requires—depends on the property's logical complexity. "Does a node have degree exactly 1?" is simple. "Does the graph contain any leaves?" is harder because you need global existence knowledge.

The descriptive hierarchy perfectly predicts the communication complexity. Problems at hierarchy level N require exactly N communication rounds in optimal algorithms.

This holds for other graph properties too:

- Graph coloring (assigning colors to nodes so neighbors differ) requires communication complexity proportional to the graph's chromatic number—which has a natural place in the logical hierarchy

- Finding cliques or independent sets in infinite graphs translates to detecting properties of corresponding logical complexity

- Graph connectivity (determining if the graph is connected in various ways) maps to different hierarchy levels depending on whether you're checking simple connectivity or more complex connectivity properties

The bridge enables researchers to take years of theoretical computer science results about finite graphs and extend them to infinite structures with confidence. The scaling works because the mathematical structure is identical.

Textbooks are rated as the most effective resource for learning, followed by research papers. Estimated data based on typical resource effectiveness.

The Surprise: Why This Connection Shouldn't Exist

Mathematicians were genuinely puzzled why this connection exists at all.

Set theory deals with infinite structures. Computer science (traditionally) deals with finite computations. The languages are completely different—logic versus algorithms. The concerns seem orthogonal—pure mathematical structure versus practical computational efficiency. The historical development happened independently across different mathematical communities who barely knew each other existed.

There's no obvious reason why problems about infinite sets should directly correspond to problems about distributed networks. You'd expect at best a loose analogy, useful for intuition but not rigorous equivalence.

Yet the equivalence is perfect. Not approximate. Not suggestive. Mathematically identical.

This reveals something fundamental: underlying many mathematical structures is a deeper organizational principle that manifests in multiple ways. Logical complexity, distributed computation, infinite set structure—these appear different on the surface. But they're expressions of the same underlying principle.

Mathematicians often find such connections at the deepest levels of their discipline. When disparate fields suddenly connect, it usually indicates you've discovered something about the fundamental architecture of mathematics itself.

Clinton Conley at Carnegie Mellon, a descriptive set theorist who's been exploring the bridge, expresses the sentiment: "This whole time we've been working on very similar problems without directly talking to each other. It just opens the doors to all these new collaborations."

The surprise isn't that the connection works. It's that mathematicians on both sides had developed sophisticated research programs for decades without realizing they were solving the same problems.

Implications for Future Mathematics and Computing

With the bridge established, researchers are racing to explore its implications.

One direction: applying the connection to solve long-standing open problems. In distributed computing, certain questions about lower bounds have resisted proof for decades. Researchers are now translating these into set-theoretic questions and attacking them with logical machinery. Early results suggest this approach will crack open problems previously thought intractable.

In set theory, the bridge provides new motivation for studying seemingly abstract questions. Properties that seemed like pure mathematical curiosities suddenly have computational interpretation. This gives set theorists new intuition about which questions matter and why.

Another direction: extending the bridge to broader classes of problems. Bernshteyn's initial translation applied to certain types of graphs. Researchers are now working to expand it to more general graph classes, to different notions of computability, to problems beyond pure graph theory.

Third direction: understanding what the connection reveals about computation itself. Why should logical complexity and distributed communication rounds correspond so precisely? What does this tell us about the nature of computation, information, and mathematical structure?

These are early days. The bridge was established in 2023. Researchers are still discovering what's possible to transfer, which techniques from one side translate effectively to the other, where the correspondence breaks down, and what new mathematics it enables.

The Broader Context: Connections Across Mathematics

Bernshteyn's bridge isn't unique in revealing connections across mathematical domains. But it's notably surprising given how isolated descriptive set theory had become.

Throughout mathematics history, seemingly separate fields have been shown to be studying the same structures. Topology and analysis turned out to be studying the same objects (continuous transformations of space). Group theory and physics revealed identical symmetry principles. Category theory emerged by recognizing that different mathematical objects could be studied through their relationships rather than their intrinsic properties.

Each discovery reorganized mathematics, created new research programs, and solved previously intractable problems.

The descriptive set theory-computer science bridge follows this pattern. Two fields that seemed unrelated are shown to share deep structural similarity. This recognition opens new avenues for research, suggests new problems worth investigating, and implies neither field's understanding was complete without the other.

It also suggests there are probably more bridges yet undiscovered. Other isolated mathematical fields might share surprising connections with applied domains. Other specialized research communities might be solving each other's problems without knowing it.

Finding these bridges requires the kind of broad mathematical literacy that's becoming rarer as specialization increases. It requires researchers willing to learn languages from distant fields. It requires collaborative communities open to outsiders. And it requires luck—timing, the right person thinking the right thought at the right moment.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Okay, so mathematicians in different fields discovered they're studying related problems. Why should anyone outside mathematics care?

Several reasons.

First, practical impact. Distributed computing isn't abstract. It powers everything from cryptocurrency networks to cloud infrastructure to global communication systems. Better algorithms for distributed problems mean more efficient networks, lower costs, better reliability. The bridge provides new tools for designing these algorithms.

Second, conceptual clarification. Understanding deep connections between apparently different domains clarifies what's really going on. When you realize logical complexity and distributed computation are the same phenomenon viewed differently, you develop intuition about both. This intuition transfers to solving problems neither field had clearly formulated.

Third, education and accessibility. Descriptive set theory had a reputation as incomprehensibly abstract. Computer science has a reputation as harshly practical. The bridge suggests these perceptions are incomplete. Abstract mathematics has practical applications. Practical computing has abstract depth. Students and researchers can learn through whichever lens suits them best.

Fourth, philosophical implications. The connection raises questions about the nature of infinity, computation, and mathematical truth itself. If infinite sets behave like distributed networks, what does that reveal about the physical world? If logical complexity equals computational complexity, is that because mathematics reflects an underlying physical principle, or because it's a useful organizational scheme humans imposed?

These questions don't have immediate practical applications. But they orient how we think about fundamental concepts that underlie everything from physics to computer science to philosophy.

Challenges and Open Questions

The bridge isn't complete. Plenty of problems remain unresolved.

One challenge: the translation works cleanly for infinite graphs with specific properties. But many real networks don't fit the assumed structure. How far can the bridge extend to more general network types? Researchers are working on this, but progress is gradual.

Another challenge: understanding why the correspondence is so exact. Mathematicians don't yet have a deep explanation for why logical complexity and distributed communication should align perfectly. There are technical reasons, but the conceptual understanding remains shallow. Developing this understanding could reveal even deeper principles.

Third: extending beyond graphs. The bridge was discovered for graph problems. Can it extend to other network structures? What about hypergraphs, dynamic networks that change over time, or networks with weights on edges? Early exploration suggests the correspondence might generalize, but it's not obvious how.

Fourth: computational complexity classes. Computer science has rich theory about complexity classes—problems solvable in polynomial time, exponential time, etc. Can the bridge connect these to corresponding concepts in set theory? This would give set theorists computational complexity as a new organizing principle.

Researchers and Institutions Leading the Field

Several communities are driving this research forward.

Anton Bernshteyn at UCLA published the initial breakthrough showing the connection between descriptive set theory and distributed network problems. He continues pushing the boundary of what the bridge can do, exploring new problem classes and extending the translation further.

At Carnegie Mellon University, Clinton Conley and others are applying the bridge to classical descriptive set theory problems, reorganizing the field using computational perspectives. Their work shows how insights from distributed computing inform traditional set-theoretic questions.

Václav Rozhoň at Charles University in Prague is applying set-theoretic techniques to solve problems in distributed computing that resisted pure algorithmic approaches. His work demonstrates the practical value of the bridge for computer scientists.

Anush Tserunyan, who advised Bernshteyn early in his career, recognizes descriptive set theory as connective tissue linking different mathematical domains. She continues developing the foundational connections that make the bridge possible.

Institutions like MIT, Stanford, UC Berkeley, and several European universities have researchers actively exploring the implications of this connection. The work is still concentrated in specialized communities, but interest is spreading.

Practical Tools and Resources for Learning

If you want to understand this material more deeply, here's where to start.

For computer scientists learning about descriptive set theory: start with the basics of logical complexity—what it means for a property to require existential quantification versus universal quantification, how these nest into more complex formulas. Then learn the LOCAL model of distributed computing and how to analyze algorithm complexity in rounds of communication. The bridge becomes intuitive once you grasp both sides.

For mathematicians learning about distributed computing: understand the LOCAL model as a constraint on information availability. Each node has only local information, and communication has finite rounds. Then learn how distributed algorithms map to the logical complexity of properties they compute. The correspondence becomes clear.

Resources are emerging. Some papers on the bridge are deliberately written to be accessible to both communities. Textbooks on distributed computing increasingly mention connections to set theory. Logic and computability theory books are adding chapters on network interpretation.

The field is new enough that institutional knowledge is scattered. Building a complete pedagogical path from fundamentals to current research remains an open problem.

The Future: Where This Research Leads

Looking forward, the bridge suggests several future directions.

Solving open problems: Both fields have long-standing unsolved questions. The bridge provides new attack vectors. Some problems that seemed hard from a pure algorithmic perspective might have clean logical proofs. Others might yield to computational analysis when translated into set-theoretic language.

Unifying frameworks: As the bridge develops, researchers might discover a unified framework encompassing both descriptive set theory and distributed computing—and possibly other fields too. This would represent a significant conceptual advance, clarifying what's truly fundamental about these domains.

Physical interpretations: Some researchers speculate the bridge might relate to physics. Quantum computing, for instance, seems to involve exploring complex computational spaces. Could descriptive set theory illuminate quantum algorithms? The connection remains speculative, but it's worth exploring.

Educational reorganization: As the field matures, curricula might reorganize around the bridge. Rather than teaching descriptive set theory and distributed computing as separate subjects, courses might teach the unified framework, with both applications as special cases.

New problems: The bridge itself suggests new questions to ask. What other mathematical domains share similar structures? Are there other bridges waiting to be discovered? These meta-questions could keep mathematicians engaged for decades.

FAQ

What is descriptive set theory?

Descriptive set theory is the study of infinite sets and how they can be constructed, described, and measured. It organizes infinite sets into hierarchies based on logical complexity, ranging from simple sets defined by straightforward conditions to impossibly complex pathological sets that can't even be measured using standard definitions of size. The field emerged from Georg Cantor's discovery that infinity comes in different sizes and grew into a systematic way to classify and understand infinite mathematical objects.

How does the bridge between set theory and computer science actually work?

The bridge works through a precise mathematical translation: the logical complexity required to define a property in set theory corresponds exactly to the number of communication rounds needed to compute that property in a distributed network algorithm. A property defined by a simple logical formula requires few communication rounds; properties requiring complex logical formulas need many rounds. This correspondence is not approximate—it's mathematically exact, allowing complete translation of solutions and techniques between both domains.

What are the practical applications of this connection?

The bridge enables computer scientists to prove new theorems about distributed networks and algorithms using set-theoretic techniques. It allows set theorists to interpret their abstract questions computationally, providing new intuition about why certain infinite structures matter. Practically, this helps design more efficient distributed algorithms for networks, which improves everything from cryptocurrency systems to cloud computing infrastructure to global communication networks. It also provides new approaches to solving long-standing open problems in both fields.

Why was this connection surprising to mathematicians?

Mathematicians were shocked because the two fields use completely different languages (logic versus algorithms), deal with seemingly opposite domains (infinite structures versus finite computation), and developed entirely independently. There was no theoretical reason why a property's logical complexity should correspond to distributed algorithm communication rounds. The fact that it does perfectly suggests something fundamental about how mathematics is organized, indicating these fields were unknowingly studying the same underlying phenomenon from different angles.

Can this bridge extend beyond graph problems?

Researchers are actively exploring this question. The bridge was initially discovered for infinite graph problems, but early work suggests it might extend to hypergraphs, weighted networks, dynamic networks that change over time, and other combinatorial structures. However, understanding exactly how far the translation generalizes remains an open research question. Each new structure type requires careful analysis to verify the correspondence holds.

How do infinite graphs relate to real-world networks?

While real computer networks are finite, studying infinite graph problems provides several benefits: it reveals fundamental limitations and possibilities independent of network size, it provides mathematical elegance that often clarifies finite cases, and it offers insights into asymptotic behavior as networks scale. Moreover, some theoretical models naturally produce infinite structures, and the techniques for analyzing them often transfer back to understanding finite networks of any size.

Who is doing research in this area?

Key researchers include Anton Bernshteyn at UCLA (who made the initial breakthrough), Clinton Conley at Carnegie Mellon (applying the bridge to set theory problems), Václav Rozhoň at Charles University in Prague (using set theory to solve distributed computing problems), and Anush Tserunyan (recognizing set theory as a connecting framework). Universities like MIT, Stanford, UC Berkeley, and various European institutions have researchers actively developing the implications of this connection.

What skills do you need to understand this research?

You need foundational knowledge in either mathematical logic and set theory or distributed computing and algorithms—ideally both. The bridge is most powerful for people who understand both languages. If you specialize in one, learning the basics of the other is manageable and increasingly worthwhile as more educators develop resources explaining the connection to mixed audiences.

What are the biggest open problems in this area?

Key open questions include: how far can the bridge extend to more general graph structures, why is the correspondence between logical and computational complexity so exact, can the bridge connect to computational complexity classes, and what other mathematical bridges might exist between specialized fields. Additionally, researchers want to understand whether the bridge reveals something fundamental about computation itself or represents a particular organizational scheme.

How might this affect mathematics education?

As the bridge develops and matures, it could eventually reorganize how these subjects are taught. Rather than separate courses in descriptive set theory and distributed computing, educational programs might teach unified frameworks incorporating both. This would make abstract mathematics feel less isolated and give computer science a stronger theoretical foundation, ultimately creating mathematicians and computer scientists with broader understanding of their fields' deep connections.

Conclusion: A New Era of Mathematical Connection

The discovery that descriptive set theory and distributed computing are asking the same fundamental questions represents more than a technical breakthrough. It's a reminder that mathematics, for all its fragmentation into specialized subfields, maintains deep underlying unity.

For decades, descriptive set theorists worked in intellectual isolation, studying infinities that other mathematicians considered pathological edge cases. Computer scientists meanwhile built sophisticated algorithms and theory for finite networks, largely unaware that their problems were equivalent to ancient questions about infinite sets.

Then Bernshteyn showed the bridge. And suddenly, what seemed like two incompatible research programs resolved into a single underlying mathematical reality viewed from two perspectives.

This discovery opens immediate research opportunities: solving long-standing open problems by translating them to more receptive domains, extending the bridge to broader problem classes, understanding why the correspondence exists at such a fundamental level. But it also hints at something deeper.

If two mathematical communities working independently arrived at equivalent frameworks without knowing it, how many other such equivalences exist undiscovered? What other bridges link specialized fields? How much of mathematics's apparent fragmentation reflects reality, versus represents human limitations in recognizing deep connections?

For researchers already working in these fields, the bridge transforms how they think about their problems. Set theorists gain computational intuition. Computer scientists gain access to decades of set-theoretic machinery. Both communities gain collaborators and fresh perspectives.

For students choosing mathematical paths, the connection suggests that abstract and applied mathematics aren't opposite poles but different views of the same fundamental structures. That pure research and practical problem-solving use the same underlying tools. That learning in one domain directly builds capacity in apparently unrelated domains.

For the broader mathematical community, Bernshteyn's work exemplifies how progress happens at deep structural levels. New breakthroughs often come not from within a field but from recognizing connections to other fields. The future of mathematics likely involves identifying more such bridges, developing frameworks that unify previously separate domains, and training mathematicians who are fluent across traditional boundaries.

The bridge between infinity and algorithms is still new. Researchers are just beginning to explore what it enables. But its discovery suggests that the most important mathematical work ahead involves recognizing that fields we thought were different have been studying the same problems all along.

The strange mathematics of infinity, it turns out, isn't strange at all. It's just a different language for talking about algorithms, computation, and the structure of networks. Understanding that connection changes how both fields think about what they're really doing.

And that's when real progress begins.

Key Takeaways

- Descriptive set theory and distributed computing solve mathematically equivalent problems using completely different languages and frameworks

- Logical complexity in set theory corresponds exactly to communication rounds required in distributed algorithms, enabling perfect translation between domains

- Anton Bernshteyn's 2023 breakthrough unified two isolated research communities, allowing set theorists to apply algorithmic techniques and computer scientists to leverage set-theoretic machinery

- The bridge reveals that the most pathologically complex infinite sets in set theory correspond to the hardest distributed computing problems

- Researchers are actively extending the bridge to solve long-standing open problems in both fields and exploring whether other mathematical domains share similar hidden connections

![How Infinity Connects to Computer Science Through Set Theory [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-infinity-connects-to-computer-science-through-set-theory/image-1-1767530146886.jpg)