Introduction: When Flat Isn't Really Flat

Stand in the middle of a wheat field on a clear day and the world looks impossibly flat. Your horizon stretches endlessly in every direction, and if you didn't know better, you'd swear you're living on an infinite plane. But we're not. We're standing on a sphere so massive that its curvature becomes invisible to our tiny human perspective.

This disconnect between local observation and global reality is the beating heart of a mathematical idea that changed everything. It's called a manifold, and it might be the most important concept you've never heard of.

For centuries, mathematicians thought space was straightforward. Euclidean space, named after the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, gave us clean rules. Parallel lines never met. The shortest distance between two points was a straight line. Triangles had angles that summed to exactly 180 degrees. It was orderly, predictable, and completely adequate for describing the world around us.

Then Bernhard Riemann arrived in the mid-19th century and broke everything in the best possible way.

In 1854, this shy German mathematician gave a lecture at the University of Göttingen that would reshape geometry, topology, physics, and modern mathematics itself. He proposed something radical: a space could look flat locally, like a piece of paper right in front of your nose, but could be fundamentally curved when you step back and see the whole picture. This idea was so abstract, so philosophically distant from practical mathematics, that most of his contemporaries dismissed it as nonsense.

"Many scientists and philosophers were saying, 'This is nonsense,'" recalls historians of mathematics. The mathematical establishment simply wasn't ready.

But Riemann was thinking about something deeper than physical reality. He was creating a language for talking about any space that could exist mathematically, regardless of how weird or unintuitive. He was building the foundation for modern topology, differential geometry, and eventually Einstein's theory of gravity itself.

Today, manifolds aren't just abstract mathematical curiosities. They're central to machine learning, data analysis, physics, cosmology, and even how we think about high-dimensional spaces we can't possibly visualize. They're as fundamental to modern mathematics as the alphabet is to language. You can't seriously discuss advanced mathematics, physics, or data science without understanding them.

So what exactly is a manifold? How does it work? And why should you care?

TL; DR

- Manifolds are spaces that look flat locally but can be curved globally, like Earth appearing flat when you're standing on it but being spherical overall

- Bernhard Riemann introduced the concept in 1854, revolutionizing geometry and laying the groundwork for Einstein's general relativity

- Manifolds enable mathematicians to study curved spaces rigorously by understanding how geometry changes from point to point

- They're fundamental to modern physics, topology, machine learning, and data analysis, making them essential for understanding advanced mathematics

- The power of manifolds comes from providing a unified framework for studying spaces of any dimension and curvature

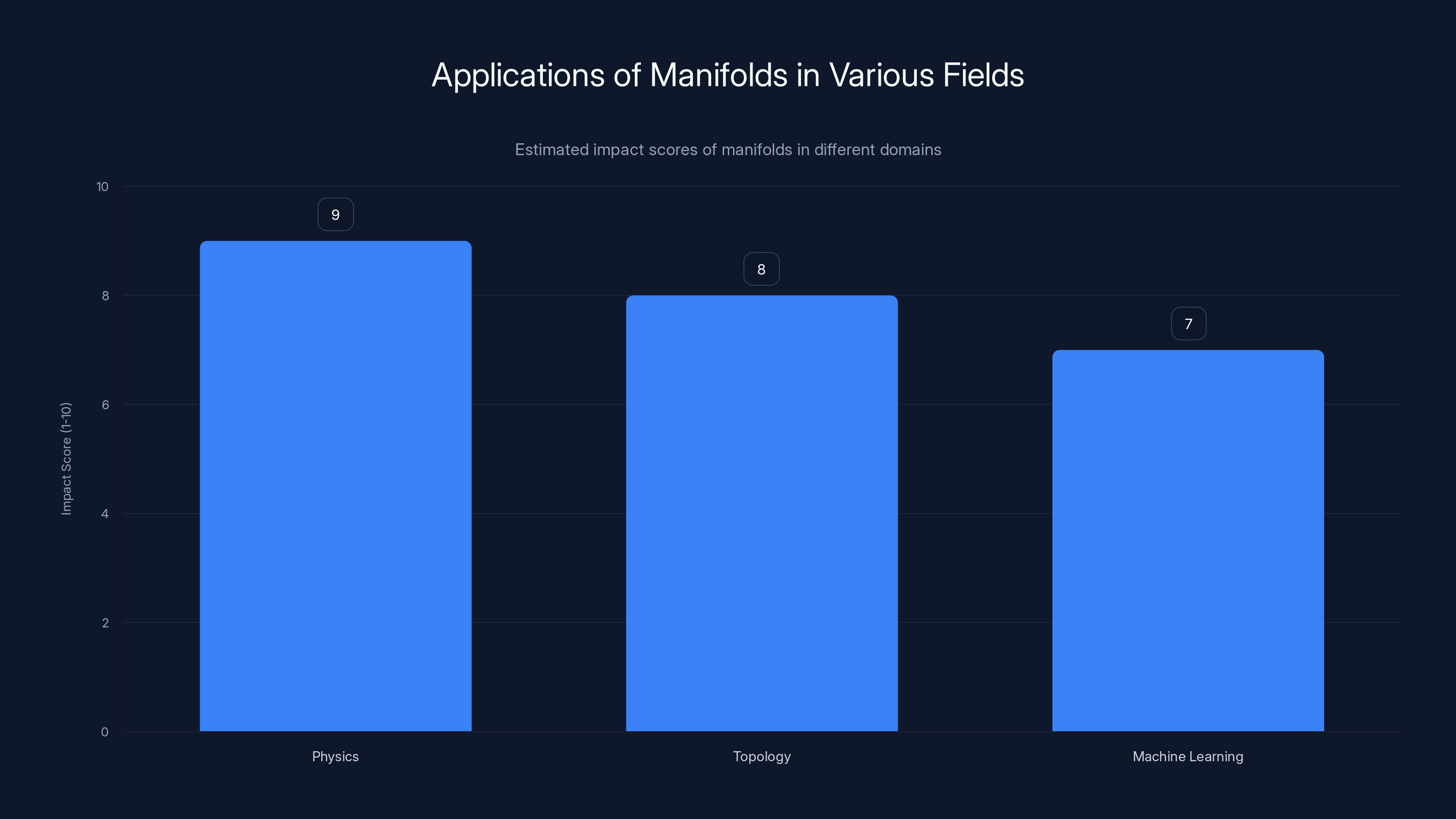

Manifolds have a significant impact across various fields, with the highest influence in physics due to their role in general relativity. Estimated data.

The Problem That Started It All: Why Euclidean Space Wasn't Enough

For over two thousand years, geometry meant Euclidean geometry. It was the geometry of Euclid's Elements, published around 300 BCE, and it remained virtually unchallenged until the early 1800s. There was a good reason for this dominance: Euclidean geometry worked. It described the world we could see and measure. It was simple, elegant, and mathematically consistent.

But hidden inside Euclid's system was an uncomfortable assumption that nobody really questioned until much later. The fifth postulate—also called the parallel postulate—stated that through any point not on a line, exactly one parallel line could be drawn. This seemed obvious, almost trivial. Of course parallel lines stay parallel. What else could happen?

Yet something was bothering mathematicians. You couldn't prove the parallel postulate from the other axioms. It had to be assumed as true. This is the mathematical equivalent of a persistent itch you can't quite scratch. For centuries, mathematicians tried to prove it from first principles and failed, again and again.

By the early 1800s, a few bold mathematicians started asking a dangerous question: What if the parallel postulate was false? What if you could have more than one parallel line, or none at all? What would happen to geometry then?

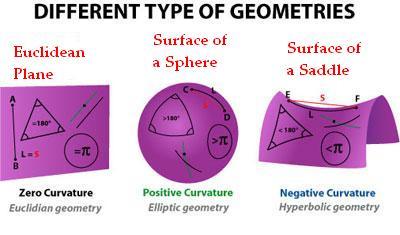

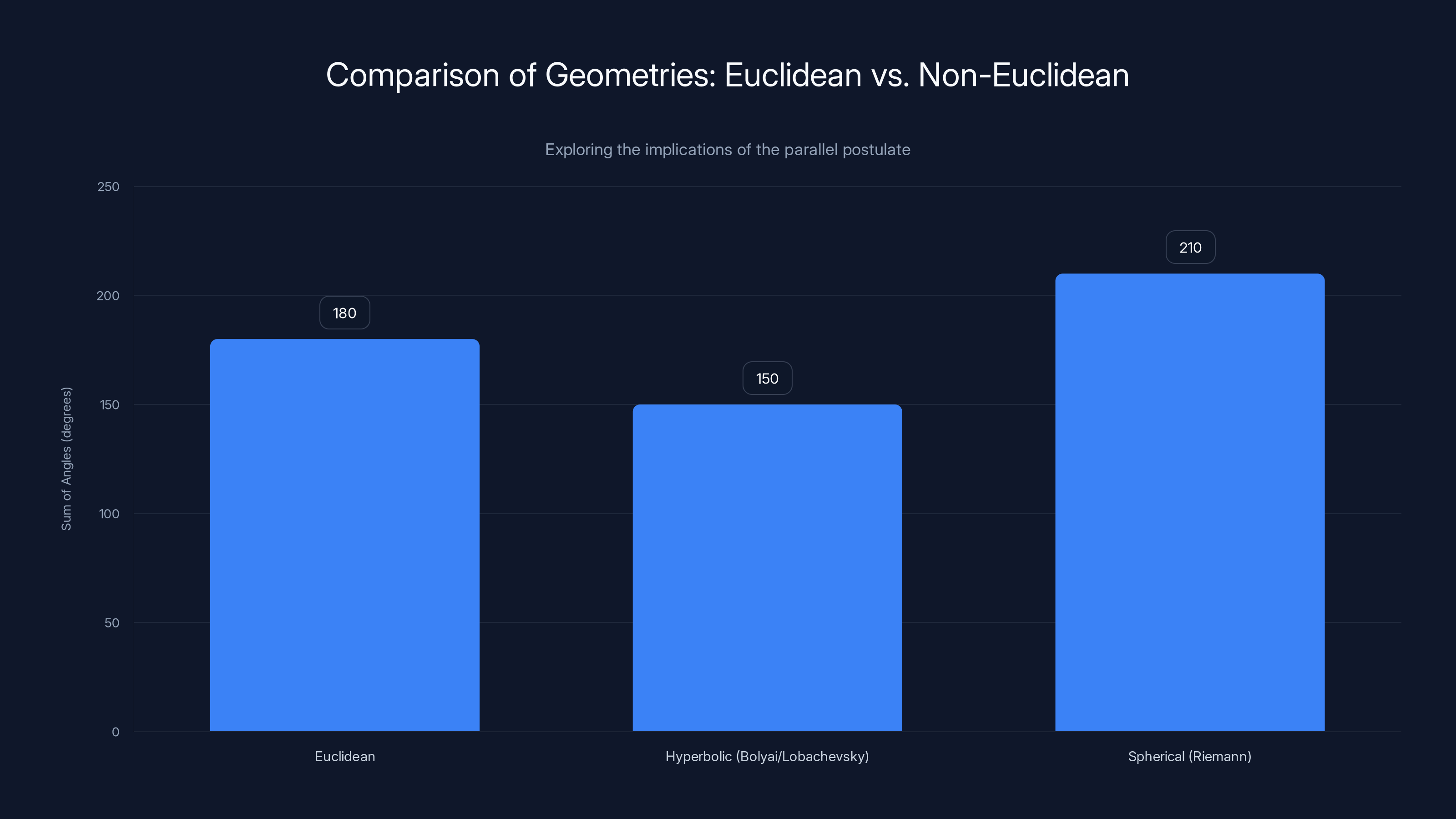

The answers were startling. János Bolyai in Hungary and Nikolai Lobachevsky in Russia independently discovered that if you rejected the parallel postulate, you could create a logically consistent geometry where triangles had angles summing to less than 180 degrees, and parallel lines diverged like the sides of a hyperbola. Meanwhile, Bernhard Riemann showed that if you went the other direction—allowing zero parallel lines—you could construct a geometry where triangles had angles summing to more than 180 degrees, like on a sphere.

These weren't fantasies or mathematical games. They were rigorous, internally consistent systems. But they raised a fundamental question: What is the nature of space itself? Is space inherently Euclidean, or is curvature a more fundamental property?

Enter Bernhard Riemann: A Shy Genius Reimagines Everything

Bernhard Riemann was not the type of person you'd expect to revolutionize mathematics. Born in 1826 in Breselenz, Germany, he was intensely shy, prone to anxiety, and his father had expected him to become a Protestant pastor. By all accounts, Riemann should have taken a quiet path through life, tending a congregation and raising a family.

Instead, he became one of the greatest mathematicians in history.

Riemann's talent emerged slowly. He was sent to study theology at the University of Göttingen, the mathematical center of the German-speaking world. But he kept sneaking into mathematics lectures. After a few months, he asked his father's permission to switch to mathematics. His father reluctantly agreed, probably expecting his son to find moderate success and a decent professorship.

He found genius instead.

Riemann became a student of Carl Friedrich Gauss, one of the few mathematicians of the era capable of understanding the new geometric ideas circulating through Europe. Gauss had been studying the intrinsic geometry of curved surfaces—what their geometry looked like from the inside, regardless of how they were embedded in higher-dimensional space. This was a crucial insight. The geometry of a sphere's surface depends only on the sphere itself, not on the three-dimensional space it happens to sit in.

Riemann pushed this idea to its logical extreme. If you could study the intrinsic geometry of any curved surface, why not study the intrinsic geometry of arbitrarily high-dimensional spaces? Why not create a mathematical framework that could describe any possible geometry in any number of dimensions?

The University of Göttingen required candidates for academic positions to deliver a lecture on a topic of their choosing from a list provided by the faculty. In 1854, the faculty invited Riemann to lecture, and Gauss personally suggested the topic: "On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Foundations of Geometry." It was a gift of a topic, perfectly positioned to let Riemann explain his revolutionary ideas.

On June 10, 1854, despite his well-known fear of public speaking, Riemann stood before the faculty and described a geometric framework so general and abstract that it made everyone's head hurt. He talked about manifolds—though he called them by the German word Mannigfaltigkeit, meaning "variety" or "multiplicity." He described how you could have spaces of any dimension, with any kind of curvature, and still do meaningful mathematics on them.

Gauss was impressed. The faculty was bewildered. And most of the broader mathematical community thought Riemann had lost his mind.

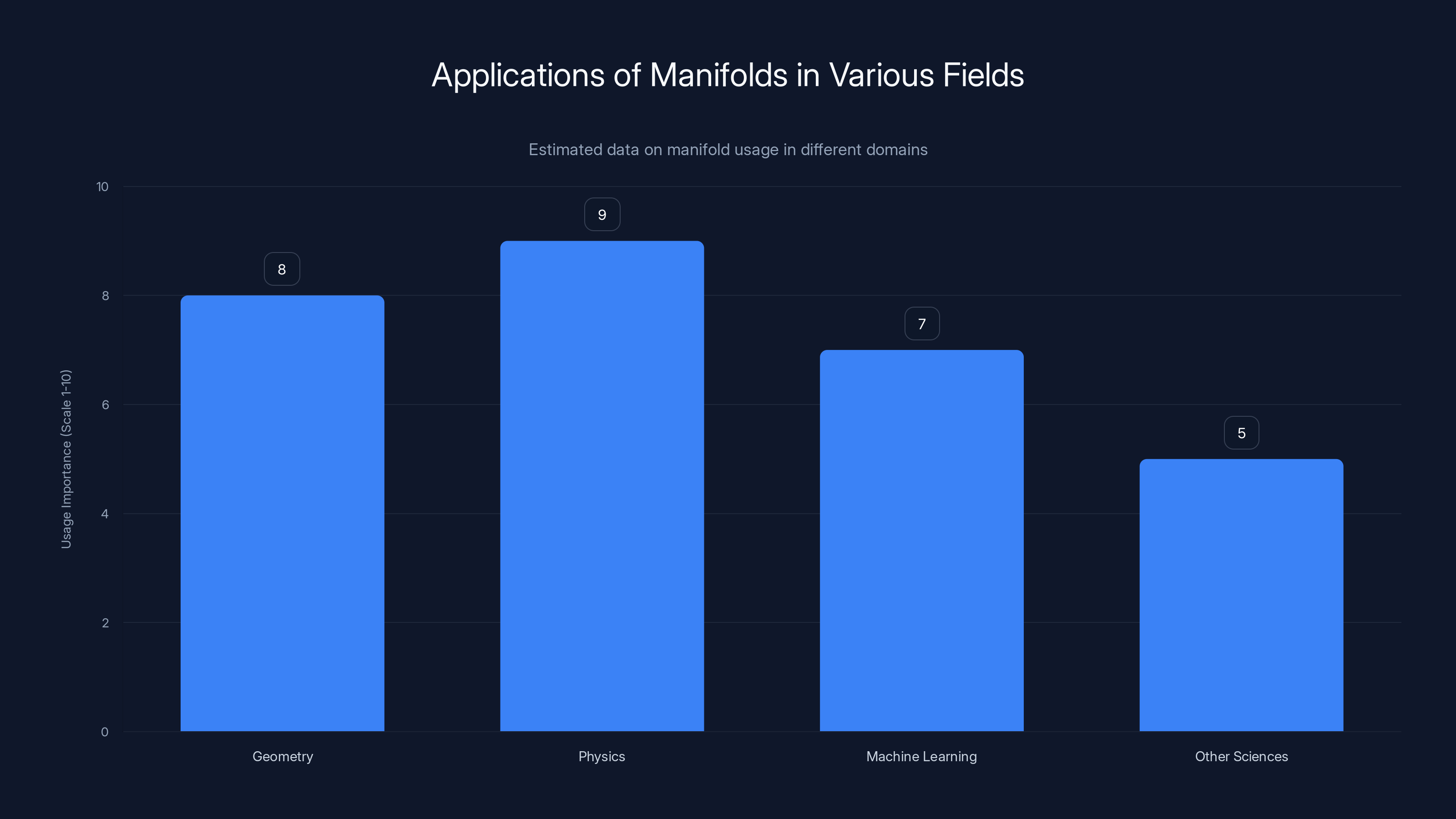

Manifolds play a crucial role in physics and geometry, with significant applications in machine learning. Estimated data.

What Exactly Is a Manifold? The Core Concept Explained

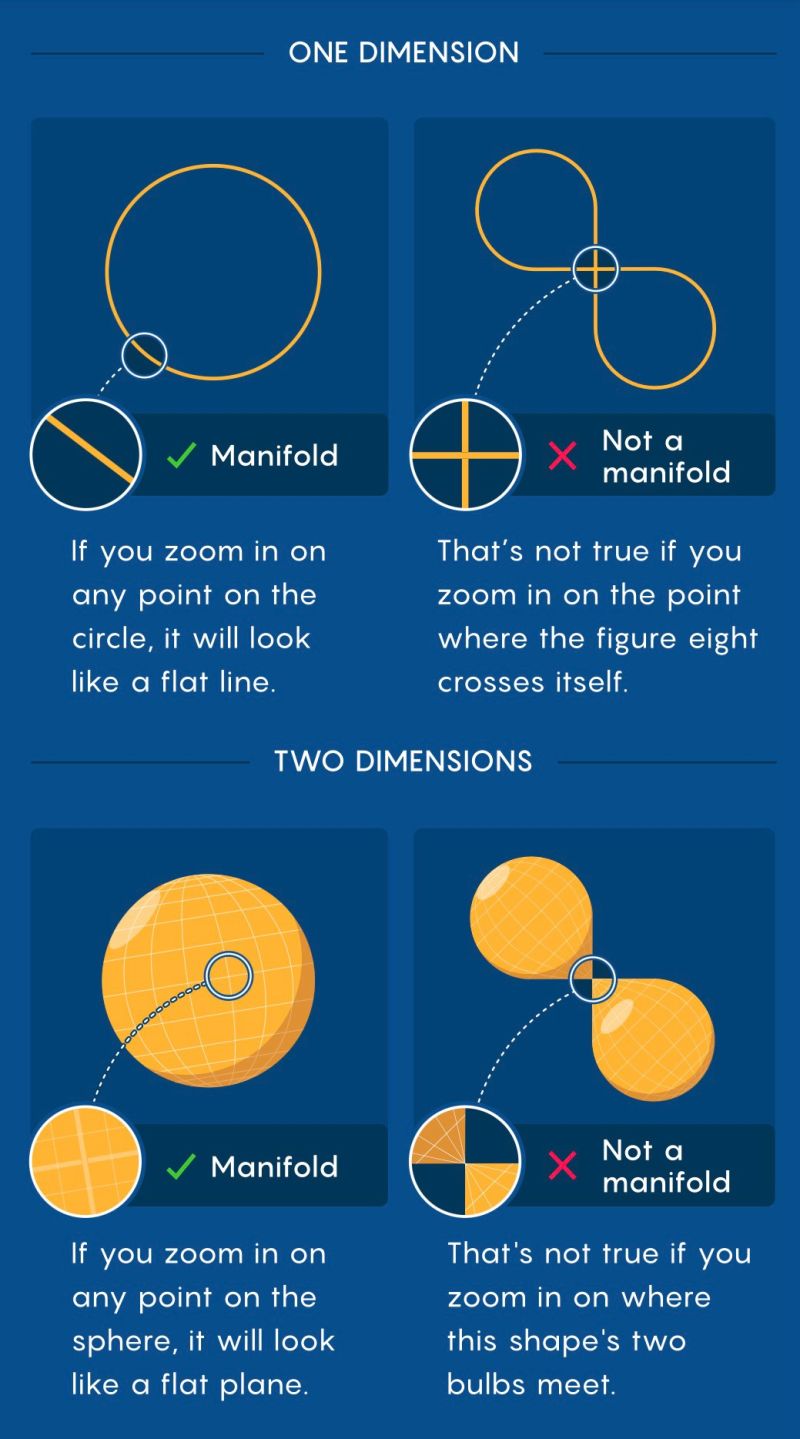

A manifold is a mathematical space that has a very specific property: if you zoom in close enough on any point in that space, it looks Euclidean. It looks flat. Locally, it behaves like the ordinary, predictable space we're familiar with.

But zoom out, and the whole space might be curved, twisted, looped, or shaped in ways that seem impossible.

Think about standing on Earth. From your perspective, the ground around you is flat. You could walk forward for miles and never notice the curvature. A geometric theorem you learned in high school—that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line—works perfectly well at your local scale. But Earth as a whole? That's a sphere. It's curved. If you fly far enough, you'll circle back to where you started.

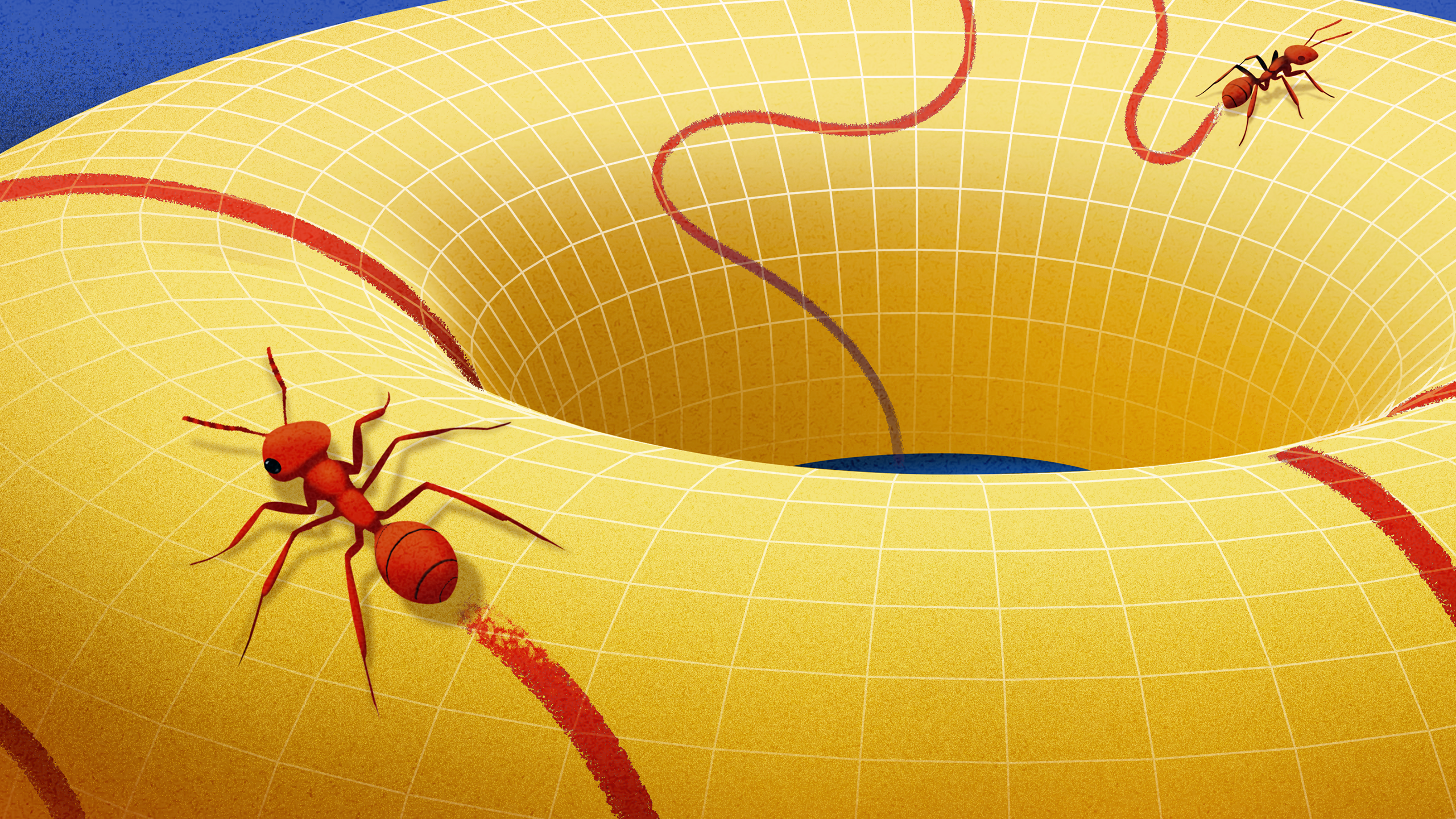

Earth is a 2-dimensional manifold embedded in 3-dimensional space. An ant walking on Earth's surface never experiences the curvature directly. It can only discover Earth is round by traveling far enough and noticing it comes back to the starting point.

A circle is a 1-dimensional manifold. Zoom in on any point on a circle and it looks like a straight line. An ant walking on a circle never notices it's looped back on itself. From the ant's local perspective, the circle is just a line that goes on forever in both directions.

But a figure eight is NOT a manifold. At the intersection point where the two loops cross, no matter how much you zoom in, the space doesn't look Euclidean. It looks like two lines intersecting at a point. An ant at that intersection can tell immediately that something strange is happening. The figure eight fails the manifold test.

The surface of a sphere is a manifold. The surface of a torus (a doughnut shape) is a manifold. The surface of a coffee cup is a manifold. Even the surface of a hyperbolic saddle is a manifold, even though it curves in different directions at different places.

But the surface of a double cone (two cones connected at their tips) is NOT a manifold. At the connection point, the space isn't locally Euclidean anymore.

This seemingly simple property—looking flat locally but potentially curved globally—is the key insight that makes manifolds so powerful. It means you can study any geometric space by understanding how it looks at each individual point, and how those local perspectives fit together.

Why Dimension Matters: The Vocabulary of Manifolds

When we talk about manifolds, dimension is everything. A one-dimensional manifold is a curve. A two-dimensional manifold is a surface. A three-dimensional manifold is a solid. And yes, you can keep going to four dimensions, five dimensions, or any number your mathematics can handle.

Here's where things get wild: we can talk about these higher-dimensional spaces completely rigorously, even though we can't visualize them.

A 1-dimensional manifold could be a circle, a line, a spiral, or an infinitely tangled curve. What matters is that if you zoom in on any point, it looks like a short segment of a line.

A 2-dimensional manifold could be a sphere, a torus, a projective plane, or a Klein bottle. Each has different properties, but they all share the property that zooming in on any point makes them look like a small patch of flat 2D space.

A 3-dimensional manifold is harder to visualize, but you can think of it as something that locally looks like 3D space. The entire universe might be a 3-dimensional manifold, curved in ways we're still trying to figure out.

And 4-dimensional manifolds and higher? These get truly abstract. You can't picture them, but you can write equations that describe them. You can prove theorems about them. You can understand their properties mathematically even if your brain can't create a mental image.

This is the profound power of Riemann's insight. By working with the local structure of spaces rather than trying to embed them in higher dimensions and visualize them, mathematicians could study geometric objects of arbitrary complexity with rigorous precision.

The dimension of a manifold is the minimum number of coordinates you need to specify any point on it uniquely. A circle is 1-dimensional because you just need one number (the angle) to say where you are on it. A sphere is 2-dimensional because you need two numbers (latitude and longitude, though the poles create some weird edge cases). A bagel (torus) is 2-dimensional. The volume of a ball is 3-dimensional.

The Crucial Distinction: Manifolds vs. Everything Else

Not every space is a manifold. This distinction matters because manifolds have special properties that make them mathematically tractable.

Consider a figure eight again. It's a curve in 2D space. It looks locally like a line everywhere except at the crossing point. At that crossing point, if you zoom in, you don't see a line. You see two distinct paths that can be traveled independently. This local structure is fundamentally different from a circle's, so a figure eight isn't a manifold.

Or consider a cone. The surface of a single cone is actually a manifold. Zoom in anywhere on it and it looks flat. But a double cone (two cones stuck together at their tips) has that junction point where the geometry breaks down. That junction point ruins the manifold property.

This matters because manifolds have something called differentiable structure. You can do calculus on manifolds. You can define tangent vectors, take derivatives, integrate functions. These operations are well-defined and consistent everywhere on a manifold.

On a space that isn't a manifold? These operations break down at the singular points. The mathematics becomes ambiguous or undefined.

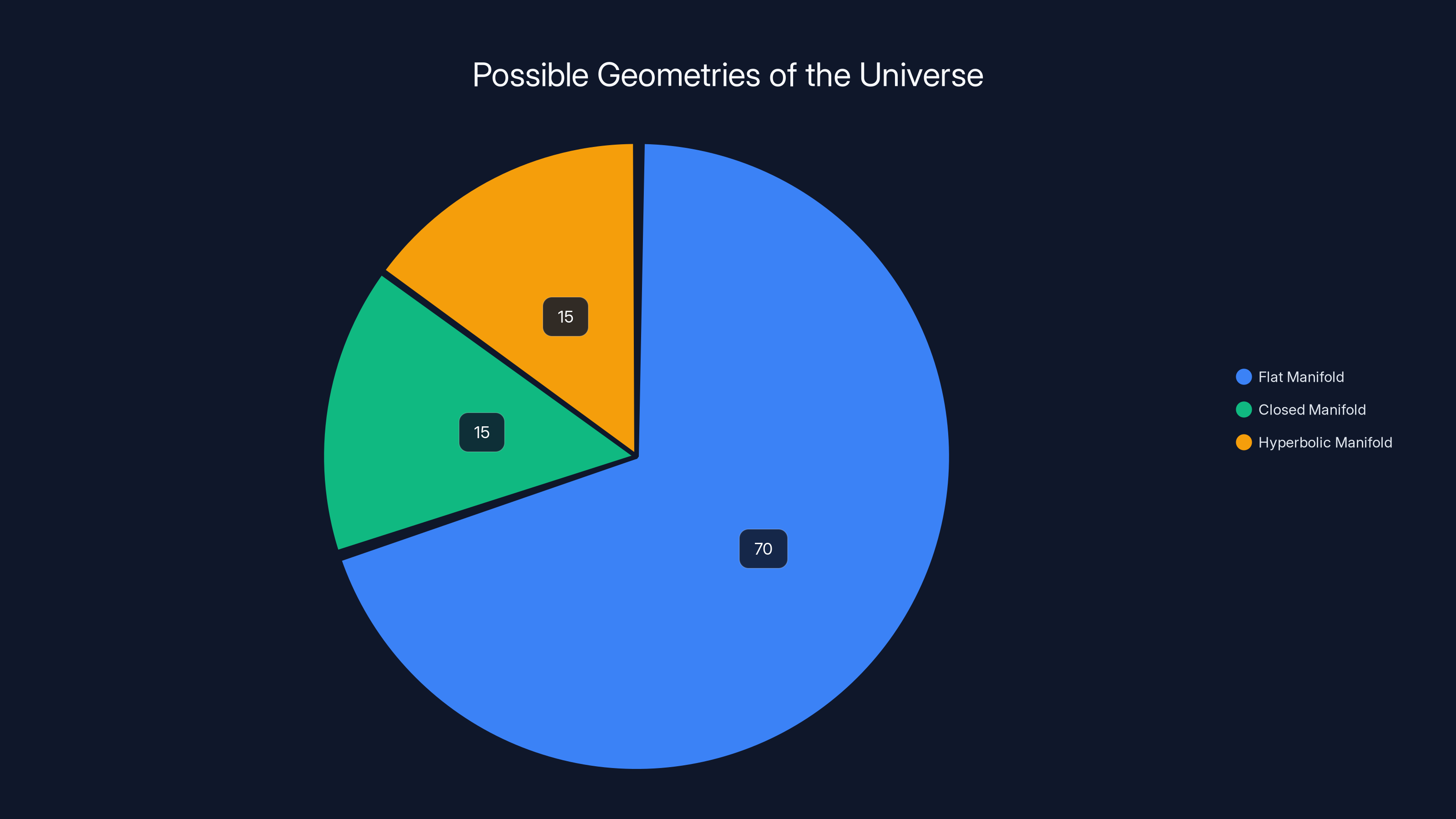

Current cosmological observations suggest the universe is most likely a flat manifold, but there is still a possibility of it being slightly closed or hyperbolic. (Estimated data)

Tangent Spaces: How Manifolds Connect Local and Global

One of the most elegant ideas in manifold theory is the tangent space. At every point on a manifold, there's a flat space that "touches" the manifold at that point—the tangent space.

Think about a sphere. At the North Pole, the tangent space is a flat 2D plane that's tangent to the sphere at that point. If you're standing at the North Pole and you have a piece of paper, you can lay it flat against the sphere and it will touch perfectly at the North Pole. A tiny ant standing at the North Pole might not realize it's on a sphere at all—it would just feel like standing on a flat plane.

The tangent space captures the local flatness of the manifold. It's the "flat space" that you're studying when you zoom in on a point.

Here's what makes this profound: even though the manifold itself might be curved in ways your mind can't fully grasp, the tangent space at each point is just Euclidean space. You can do regular calculus in tangent spaces. You can use all the familiar tools of linear algebra.

The tangent bundle of a manifold is the collection of all tangent spaces at all points, glued together in a consistent way. It's a manifold in its own right, typically double the dimension of the original manifold. For instance, the tangent bundle of a 2-sphere (a spherical surface) is a 4-dimensional manifold.

This idea—that you can understand the global structure of a curved space by understanding how all the local flat spaces fit together—is the heart of differential geometry. It's how mathematicians work with curved spaces they can't visualize.

Riemannian Geometry: Adding Measurement to Manifolds

On a manifold, you can talk about the topology—the shape, the structure. But to do geometry, you need to measure things. You need to know distances, angles, areas. This is where Riemannian geometry enters the picture.

Bernhard Riemann had another brilliant idea: you could define a notion of distance and angle at each point on a manifold, in a smooth way. This definition is called a metric.

A metric is a mathematical object that lets you measure distances. In Euclidean space, the distance between two points

This is the Pythagorean theorem, and it's the basis of Euclidean distance.

On a curved manifold, distance works differently. On a sphere, the shortest path between two points isn't a straight line—it's an arc of a great circle. The distance between New York and London isn't measured by a straight line through the Earth; it's measured along the surface of the sphere.

A Riemannian metric assigns, to each point on a manifold, a way of measuring distances in the tangent space at that point. This assignment must vary smoothly from point to point. The metric then extends to a global notion of distance: the shortest path between two points (the geodesic) can be computed by accumulating these local distance measurements.

With a metric in place, you have a Riemannian manifold, and you can do real geometry. You can measure curvature. You can calculate volumes. You can study how geometry varies from place to place.

The Gaussian curvature of a surface is a specific measure of how much that surface is curved at each point. On a flat plane, Gaussian curvature is zero. On a sphere, it's positive everywhere. On a saddle, it's negative everywhere. Different curvatures lead to radically different geometries.

The Problem of Ambiguity: Why Manifolds Solve a Critical Issue

Here's a subtle problem that existed before manifolds, and that manifolds solve elegantly.

Consider a simple loop of string. Tie the two ends together to form a closed loop. In your hand, on a table, it looks like a simple circle—a one-dimensional manifold.

Now take the string, hold it in three-dimensional space, and tie a knot before connecting the ends. You've created a trefoil knot (or some other knot). The knot is still a one-dimensional manifold—it's still topologically a loop. But it has a different property: it's "knotted."

The weird part? The trefoil knot is fundamentally a different object when you consider it in 3D space versus, say, 4D space or higher dimensions. In three dimensions, you can't unknot it by moving it around without cutting the string. In four dimensions or higher, any knot can be untied.

So what's the "real" manifold here? Is the string a simple loop or a knotted loop? The answer depends on what dimension you're considering.

Manifolds solve this by being intrinsic objects. A manifold isn't defined by how it sits inside some higher-dimensional space. It's defined by its own internal structure, independent of any embedding.

This is philosophically and mathematically elegant. It means mathematicians don't have to argue about whether a geometric object is "really" knotted or unknotted depending on some external viewpoint. The manifold is what it is, independent of any surrounding space.

It also means manifolds can be studied in their own right, without worrying about whether they can even be embedded in some higher-dimensional Euclidean space. Some manifolds can't be embedded in any finite-dimensional Euclidean space, but you can still study them rigorously as abstract manifolds.

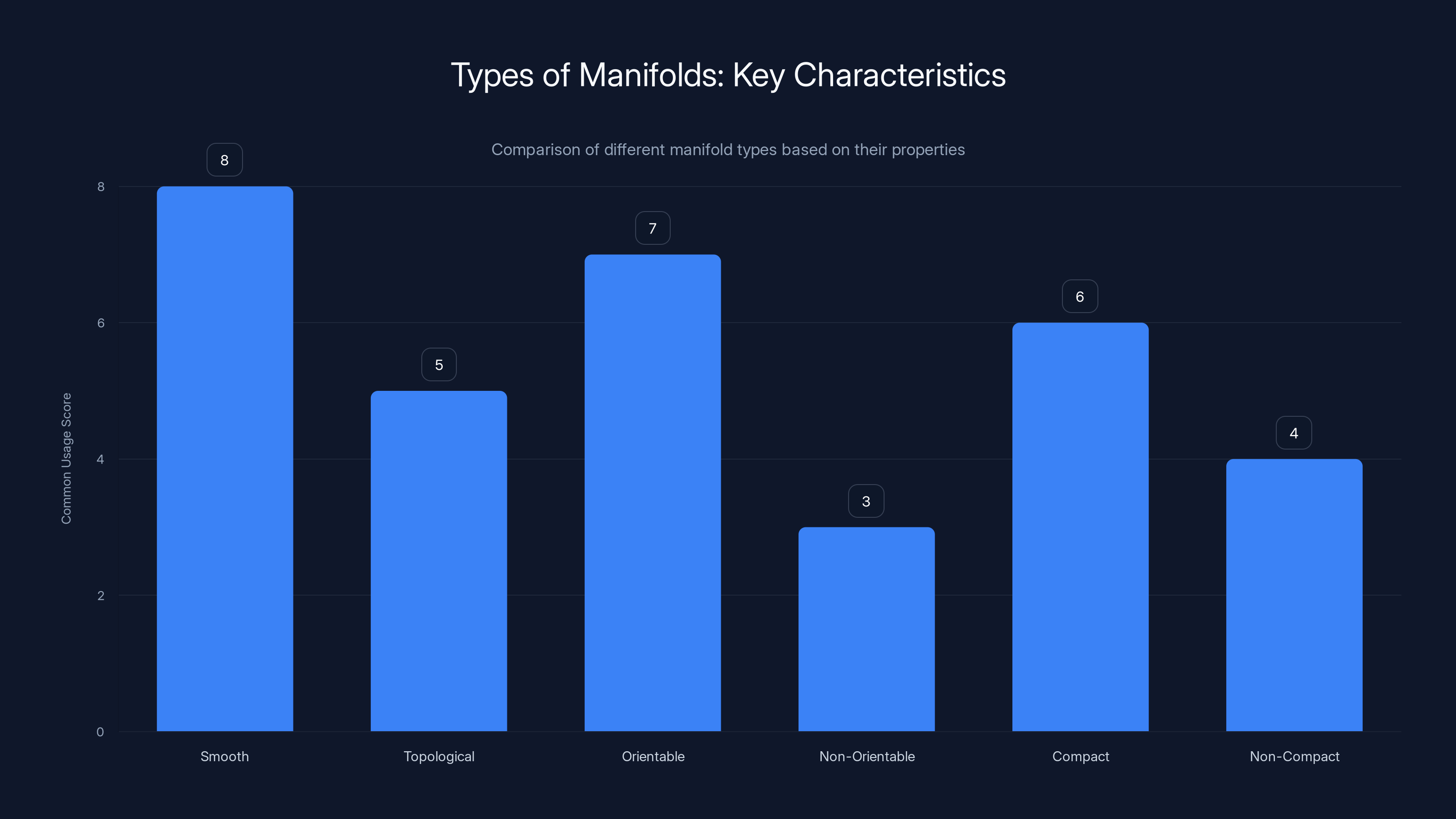

Smooth manifolds are most commonly used due to their calculus-friendly properties, while non-orientable and non-compact manifolds are less frequently encountered. Estimated data based on typical applications.

Historical Rejection and Slow Acceptance: Why Ideas Take Time

When Riemann gave his 1854 lecture, he was describing ideas that were fundamentally ahead of their time. The mathematical community's reaction ranged from skeptical to dismissive to downright hostile. Most mathematicians simply didn't see why you would bother with these abstract spaces when Euclidean geometry worked perfectly well for everything they needed to do.

After Riemann's death in 1866, his lecture remained unpublished for two years. The mathematical world moved on. His ideas existed in a kind of limbo—known to a small circle of experts but largely ignored by the mainstream mathematical community.

But by the end of the 19th century, things began to change. Henri Poincaré, one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, recognized the profound importance of Riemann's work. He began developing topology as a distinct field of mathematics, using manifolds as central objects. He proved theorems about manifolds. He showed that manifold theory was not just abstract philosophy but a rigorous mathematical discipline with real results.

Then, in 1915, everything changed. Albert Einstein used Riemannian geometry to formulate his General Theory of Relativity. Gravity, Einstein proposed, wasn't a force in the Newtonian sense. Instead, massive objects curved spacetime itself, which is a four-dimensional manifold. Objects moving through curved spacetime follow geodesics—the shortest paths through that manifold.

Einstein needed Riemannian manifolds to express his ideas. He needed differential geometry. Without Riemann's framework, general relativity couldn't exist.

Suddenly, the abstract mathematics that had been dismissed as "nonsense" became essential for understanding gravity and the structure of the universe. Manifolds were no longer philosophical curiosities. They were practical tools for physics.

By the mid-20th century, manifolds had become so central to mathematics that you couldn't study advanced mathematics without understanding them. They weren't just one tool among many—they were foundational.

Modern Applications: Manifolds in the Real World

Manifolds aren't just abstract mathematical objects. They're central to how we understand the modern world.

Manifolds in Physics

In general relativity, spacetime itself is a 4-dimensional manifold with a Riemannian metric. The curvature of this manifold, determined by the distribution of mass and energy, tells objects how to move. No forces—just the geometry of the manifold.

This framework explains gravity in a way that Newton's law couldn't. It predicts black holes, gravitational waves, and the expansion of the universe. All of it follows from the mathematics of manifolds.

Manifolds in Topology

Topology is the study of the properties of spaces that remain unchanged by smooth deformations. Manifolds are the natural objects of study in topology. A sphere and a cube are topologically equivalent—you can deform one into the other continuously. But a sphere and a torus are not topologically equivalent—you'd have to tear the surface to transform one into the other.

Topological properties of manifolds tell us about invariants that persist no matter how the manifold is stretched or deformed. These invariants—like the Euler characteristic or homology groups—capture essential information about the manifold's structure.

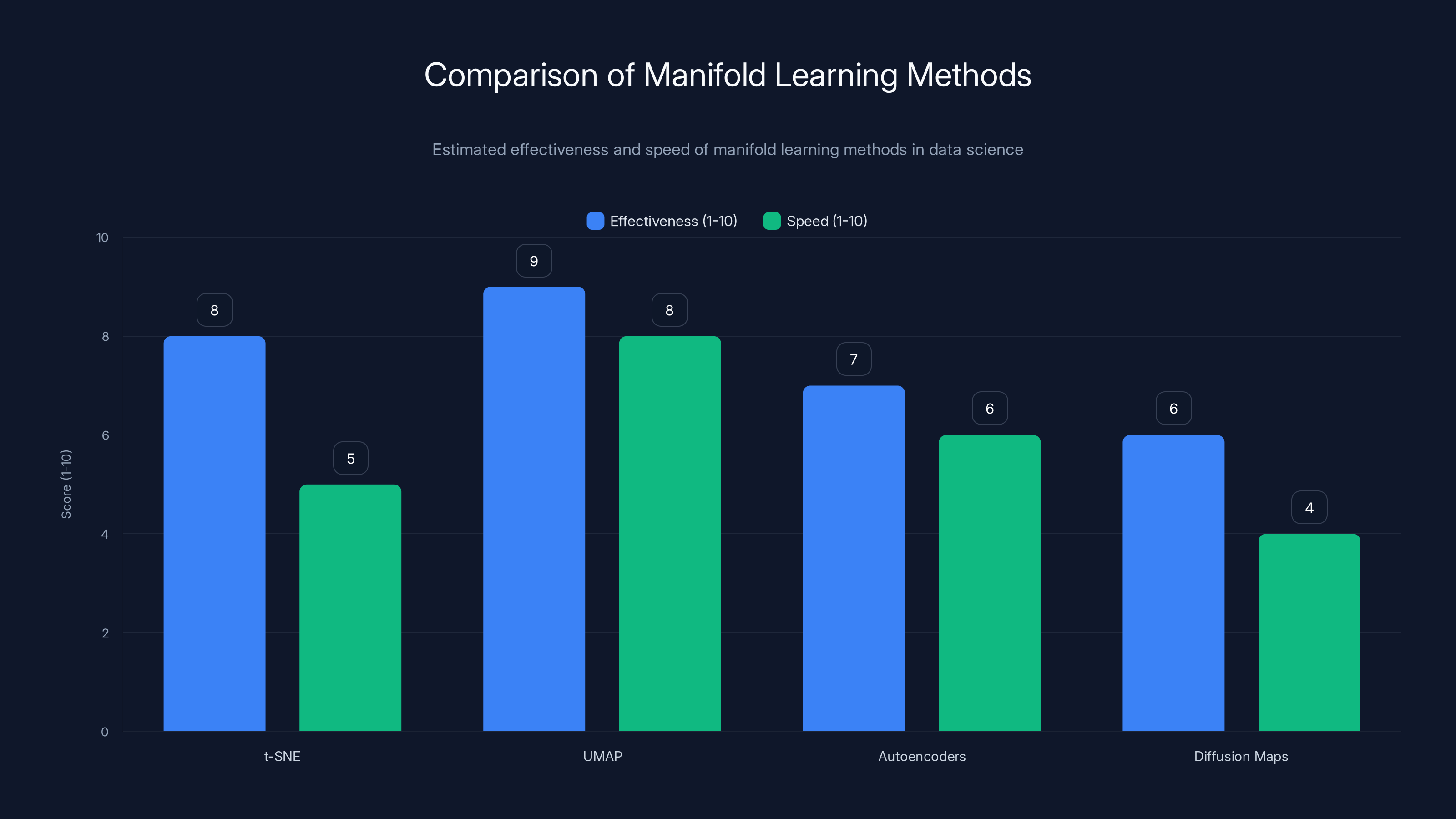

Manifolds in Machine Learning

Here's something surprising: high-dimensional data often lies on manifolds.

Imagine a dataset with 10,000 features (dimensions) describing images of faces. You might think the data is essentially 10,000-dimensional. But in reality, the actual variation in the data might lie on a much lower-dimensional manifold—maybe 20-dimensional or 50-dimensional. The faces form a particular kind of shape in high-dimensional space.

Manifold learning algorithms exploit this. They try to find the underlying manifold on which high-dimensional data lies. Methods like t-SNE, UMAP, and autoencoders work by finding low-dimensional manifold representations of high-dimensional data.

This is crucial for visualization (you can't visualize 10,000 dimensions, but you can visualize 2D or 3D representations), for compression, and for understanding data structure.

Manifolds in Data Analysis

When you're analyzing complex, high-dimensional datasets—whether it's genomic data, financial time series, or sensor readings—you're often implicitly working with manifolds. The data might be distributed on a 2D or 3D manifold embedded in a much higher-dimensional space.

Understanding this manifold structure helps with:

- Dimensionality reduction: Finding the essential dimensions that capture most of the variation

- Anomaly detection: Understanding what constitutes "normal" data on the manifold

- Classification: Using manifold structure to understand different classes

- Interpolation: Smoothly moving between data points by moving along the manifold

Manifolds in Fluid Dynamics

Phase spaces in dynamical systems are manifolds. If you have a system with, say, position and velocity as variables, the phase space is a manifold where each point represents a complete state of the system. The behavior of the system over time traces out curves on this manifold.

This perspective lets physicists and engineers understand complex systems by studying the geometry and topology of their phase spaces.

Types of Manifolds: A Taxonomy of Shapes

Manifolds come in many varieties, each with special properties.

Smooth Manifolds vs. Topological Manifolds

A topological manifold is the basic kind—a space where every point has a neighborhood that looks like Euclidean space. That's the core definition.

A smooth manifold (or differentiable manifold) goes further. It has additional structure that lets you do calculus. Derivatives, integrals, tangent vectors—these concepts only make sense on smooth manifolds.

most of the manifolds you encounter in applications are smooth manifolds because you typically need to do calculus on them.

Orientable vs. Non-Orientable Manifolds

An orientable manifold is one where you can consistently define "left" and "right" (or "up" and "down") at every point. A sphere is orientable. You can draw a normal vector pointing "outward" at every point.

A non-orientable manifold doesn't have this property. The classic example is a Möbius strip: if you draw an arrow pointing "up" and slide it around the strip, when it returns to the starting point, it's pointing "down." Or a Klein bottle: a surface that crosses through itself and has no consistent notion of inside/outside.

Non-orientable manifolds are weird but real, and they have applications in physics and topology.

Compact vs. Non-Compact Manifolds

A compact manifold is bounded and closed, like a sphere. You can't walk off the edge. A non-compact manifold goes on forever, like a line or a plane.

Compact manifolds have nice mathematical properties—for instance, continuous functions on compact manifolds are guaranteed to attain their maximum and minimum values. Non-compact manifolds can behave more wildly.

Riemannian vs. Pseudo-Riemannian Manifolds

A Riemannian manifold has a metric that defines distances in the usual way—distances are always positive or zero (they're zero only between identical points).

A pseudo-Riemannian manifold has a metric where some "distances" can be negative or zero even between different points. This sounds weird, but it's essential for physics. Spacetime in general relativity is a pseudo-Riemannian manifold where the time dimension is treated differently from the space dimensions.

UMAP is estimated to be the fastest and most effective manifold learning method, while diffusion maps are slower and less effective. Estimated data.

Homology and Cohomology: Measuring Manifold Structure

Two manifolds can look different but still have the same intrinsic properties. A sphere and a potato have different shapes, but topologically, they're the same—you could deform one into the other.

How do mathematicians measure what's intrinsically different about different manifolds? How do they distinguish between a sphere and a torus rigorously?

One answer is homology and cohomology. These are algebraic tools that capture topological information about a manifold.

Roughly speaking:

- Homology counts the number of independent "holes" of different dimensions in a manifold

- Cohomology is the dual concept—a way of capturing the same information using dual spaces

A sphere has no holes. A torus has one "hole" through the middle. A coffee cup is topologically a torus (the handle is the hole). A figure-eight curve in 3D has one hole if you think of it as a 1-dimensional manifold.

These homology groups are invariants—they don't change if you deform the manifold. They're the same for all tori, all spheres, all surfaces of any shape in a topologically equivalent class.

The Betti numbers of a manifold, derived from homology groups, are a compact way to encode this topological information. The first Betti number of a sphere is 0. The first Betti number of a torus is 2. This difference reflects the fundamental difference in their shapes.

Manifolds and Cosmology: Understanding the Universe

One of the most profound applications of manifold theory is in cosmology—the study of the structure and evolution of the universe.

Our universe, on the largest scales, appears to be a 3-dimensional manifold. (More precisely, spacetime is a 4-dimensional manifold, and at any given time, the universe is a 3-dimensional spatial manifold.)

But what kind of manifold?

That's not a philosophical question. It's a measurable, scientific question. Different manifold geometries lead to different physics.

If the universe is a flat manifold (Euclidean geometry), it will expand forever but at a decelerating rate. The total curvature is zero.

If the universe is a closed manifold like a 3-sphere (positive curvature), it will eventually contract back to a big crunch. The geometry would be like a 3D version of a balloon's surface.

If the universe is a hyperbolic manifold (negative curvature), it will expand forever, ever faster. Space will become increasingly sparse.

Observations from supernovae, the cosmic microwave background, and large-scale structure suggest our universe is very close to flat, or at least has such tiny curvature that we can't currently measure it. But it could be slightly closed or slightly hyperbolic.

This is a stunning application of manifold theory. The mathematics that Riemann developed in the 1850s for purely abstract reasons turned out to be essential for understanding the actual shape of the universe.

Higher Dimensions: Manifolds Beyond Human Intuition

One of the great powers of manifold theory is that it lets you work with spaces of any dimension, even when those dimensions are completely non-visualizable.

A 4-dimensional manifold can't be drawn or pictured. Your brain just doesn't have the hardware to visualize four spatial dimensions. But mathematicians can study 4-dimensional manifolds just as rigorously as they can study 2D or 3D manifolds.

In fact, 4-dimensional topology is an exceptionally rich and strange field. In 4 dimensions, some unique phenomena occur that don't happen in other dimensions. The exotic smooth structures on 4-dimensional manifolds—the phenomenon of multiple inequivalent ways to define "smoothness" on the same topological manifold—were discovered by Donaldson and Freedman in the 1980s.

In higher dimensions (5 and above), many problems become more tractable because there's more "room" to move things around. In dimension 4, things can get stuck in weird ways. This makes 4-dimensional topology genuinely mysterious in ways that lower or higher dimensions aren't.

In Euclidean geometry, triangle angles sum to 180 degrees. In hyperbolic geometry, they sum to less than 180 degrees, while in spherical geometry, they sum to more than 180 degrees. Estimated data based on theoretical models.

The Connection to Einstein's Revolution

When Albert Einstein was developing general relativity in the early 1910s, he needed a mathematical language that could describe curved spacetime. His mathematician friend Marcel Grossmann pointed him toward Riemannian geometry.

Einstein had a realization: the curvature of a Riemannian manifold is exactly the right way to express gravity. Objects don't feel a "force" pulling them toward the Earth. Instead, they follow the curvature of spacetime itself. The Earth is massive, so it curves spacetime around it. Other objects naturally follow the curved paths (geodesics) that this curvature creates.

This was a stunning philosophical shift. In Newton's theory, gravity is a mysterious force acting at a distance. In Einstein's theory, gravity is geometry. It's the shape of spacetime itself.

Einstein's field equations relate the curvature of spacetime (described using the Riemann curvature tensor) to the distribution of mass and energy. The Riemann curvature tensor is fundamental to Riemannian geometry—it measures how much a manifold is curved.

The equations are:

Where

This equation says: the geometry of spacetime (left side) equals matter and energy (right side). It's the mathematical embodiment of Einstein's insight that gravity is geometry.

And it all derives from Riemann's abstract mathematical framework of manifolds and Riemannian geometry, developed seventy years earlier with no application to physics in mind.

Manifolds and Modern Data Science: The New Frontier

One of the most exciting recent developments is the application of manifold theory to machine learning and data science.

High-dimensional data is ubiquitous in the modern world. Images have thousands of pixels, each a dimension. Genomic data has thousands of genes. Financial data has thousands of assets and indicators. How do you understand such high-dimensional data?

The key insight is that real-world data often lies on low-dimensional manifolds embedded in high-dimensional space.

Think about images of faces. Each image might be 256×256 pixels, so a 65,536-dimensional object. But all human faces have certain universal properties. They have two eyes in certain positions, a nose in a certain place, a mouth, ears, etc. The variation in human faces, while infinite in some sense, is actually constrained to a much lower-dimensional manifold.

This is where methods like:

- t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding): Finds 2D or 3D projections that preserve the manifold structure of high-dimensional data

- UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection): A newer method that's often faster and preserves more global structure

- Autoencoders: Neural networks that learn a compressed representation of data by finding a low-dimensional bottleneck

- Diffusion maps: Uses manifold learning to understand data geometry

All of these leverage the mathematics of manifolds.

The practical benefits are enormous:

- Visualization: You can't visualize 10,000 dimensions, but you can visualize a 2D manifold representation

- Compression: If data lies on a 50-dimensional manifold, representing it as a 10,000-dimensional cloud wastes space

- Generalization: Understanding data manifolds helps machine learning models generalize better to new examples

- Anomaly detection: Points far from the data manifold might be outliers or anomalies worth investigating

This is a field where Riemann's mathematics, developed for purely theoretical reasons in the 19th century, has become essential for practical 21st-century applications.

Challenges and Open Questions: What We Still Don't Know

Despite 170 years of research on manifolds, mathematicians still encounter deep mysteries.

The Poincaré Conjecture, posed in 1904, asked whether a simply-connected 3D manifold is necessarily a 3-sphere. It seems like it should be true, but proving it took a century. Grigori Perelman finally proved it in 2003, one of the greatest achievements in modern mathematics.

But many related questions remain open:

- How many distinct smooth structures exist on high-dimensional manifolds?

- What are the fundamental invariants that completely determine a manifold up to homeomorphism or diffeomorphism?

- How can we classify manifolds in dimension 4? (We can classify them in dimensions 5 and higher, and dimensions 1, 2, 3 have different tools)

- What's the connection between manifolds and quantum geometry?

In physics, major open questions involve manifolds:

- What is the topology of the universe on the largest scales?

- How do quantum fields behave on curved manifolds?

- Is spacetime fundamentally a manifold, or is manifold structure emergent from something more basic?

These are living, breathing research areas where new discoveries happen every year.

The Legacy: How Manifolds Changed Everything

Bernhard Riemann died in 1866, poor, not widely recognized, his health destroyed by tuberculosis. He never saw his ideas become central to mathematics and physics. He never witnessed the fields they would spawn.

But his legacy is staggering.

Manifolds have become the language of modern mathematics. Differential geometry, topology, algebraic geometry, geometric analysis—all of these fields are built on manifold theory. Physics from the atomic scale to the cosmic scale uses manifolds. Machine learning increasingly relies on manifold geometry. Data science deploys manifold learning algorithms.

The transformation happened gradually:

- 1850s-1890s: Riemann's ideas dismissed as too abstract

- 1890s-1900s: Poincaré recognizes their importance; topology emerges as a field

- 1915: Einstein uses Riemannian geometry for general relativity, legitimizing the whole enterprise

- 1920s-1950s: Manifold theory becomes a mathematical staple

- 1950s onward: Applications explode—differential geometry, algebraic geometry, dynamical systems

- 2000s-present: Manifold learning becomes crucial for machine learning and data science

What made this revolution possible was a shift in perspective. Instead of thinking about space as a fixed background where other things happen, mathematicians began thinking of space itself as an object worthy of study. Instead of assuming all spaces are Euclidean, they allowed for the possibility of curved, twisted, exotic spaces. Instead of requiring that everything be visualizable, they embraced abstract spaces you could only understand through rigorous mathematics.

This shift—which Riemann pioneered and which took decades to be accepted—has been one of the most important intellectual revolutions in the history of science.

Conclusion: The Universe Written in Geometric Language

When you stand in a field and the horizon stretches endlessly, you're experiencing a manifold. The flatness you perceive locally is real—it's the intrinsic geometry of Earth's surface at your scale. The curvature you'd see from space is equally real—it's the global structure.

Both perspectives are valid. Both are captured by the mathematics of manifolds.

Bernhard Riemann's insight—that you could talk about curved spaces rigorously by understanding how they look at each point and how those local perspectives fit together—transformed mathematics and physics. It gave us a language for describing the universe with precision and elegance.

Today, manifolds are everywhere. They're in the equations that describe gravitational waves. They're in the algorithms that let you search the internet. They're in the neural networks that power artificial intelligence. They're in the data structures that help us understand genomics, climate, and finance.

The story of manifolds is the story of how abstract mathematical thinking, pursued for its own sake with no immediate application, becomes indispensable for understanding reality. It's a reminder that mathematics isn't just a tool for solving practical problems. It's a form of poetry, a way of describing the structure of the universe.

And it all started with a shy German mathematician wondering what would happen if you stopped assuming space was flat.

FAQ

What is a manifold in simple terms?

A manifold is a space that looks flat and simple when you zoom in on any point, but can be curved and complex when you look at the whole thing. Earth is a 2-dimensional manifold—it looks flat where you stand, but it's actually spherical. The key property is that locally (at any small region), a manifold always looks like regular, flat, Euclidean space.

How did Bernhard Riemann invent manifolds?

Riemann built on Carl Friedrich Gauss's work on the intrinsic geometry of curved surfaces. In his 1854 lecture "On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Foundations of Geometry," Riemann generalized Gauss's ideas to arbitrary numbers of dimensions, creating a framework for studying any curved space. His insight was that you could understand complicated global structures by understanding local flatness and how different local pieces fit together.

What's the difference between a manifold and other geometric shapes?

Not every shape is a manifold. A manifold must look Euclidean (flat) when you zoom in on any point. A figure-eight fails this test at the crossing point—if you zoom in there, you don't see a flat line, you see two paths intersecting. A manifold must have this local flatness property everywhere. This special property gives manifolds mathematical tractability—you can do calculus on them consistently.

How are manifolds used in machine learning?

High-dimensional data (like images or genomic information) often lies on low-dimensional manifolds embedded in high-dimensional space. Machine learning algorithms use manifold learning techniques like t-SNE or UMAP to find these underlying manifolds, which enables better visualization, compression, and understanding of the data. This is crucial because you can't visualize 10,000 dimensions directly, but you can visualize a 2D or 3D manifold representation.

Why did Einstein need manifolds for general relativity?

Einstein's key insight was that gravity isn't a force—it's the geometry of spacetime itself. Massive objects curve the spacetime manifold, and other objects naturally follow the curved paths (geodesics) through this curved spacetime. The mathematics of Riemannian manifolds, specifically the Riemann curvature tensor, provided the exact tool he needed to express how geometry and gravity are related.

How many dimensions can a manifold have?

A manifold can have any number of dimensions—1, 2, 3, or 1,000 or infinite. Mathematicians study manifolds of arbitrary dimension rigorously using algebra and analysis, even though higher-dimensional manifolds can't be visualized directly. The dimension of a manifold is the minimum number of coordinates needed to specify a unique point on it.

What's the difference between a manifold and a manifold with a metric?

A manifold is a topological object—it describes the shape and connectivity. A manifold with a Riemannian metric has additional structure that lets you measure distances and angles. A Riemannian manifold is what you need to do geometry—to measure lengths of curves, compute curvature, and work with calculus. You can have different metrics on the same manifold, creating different geometric structures.

How are manifolds used in cosmology?

The universe itself is thought to be a 3-dimensional manifold (part of a 4-dimensional spacetime manifold). By studying whether the universe is flat, closed, or hyperbolic—different types of manifolds—cosmologists can understand the universe's geometry, expansion rate, and ultimate fate. Current observations suggest our universe is nearly flat, but the question of its exact topology remains open.

What are topological invariants of manifolds?

Topological invariants are properties of manifolds that don't change when you deform them smoothly. Examples include Betti numbers (which count holes), homology groups, and the Euler characteristic. These invariants let mathematicians classify and distinguish between different manifolds. Two manifolds with different topological invariants are fundamentally different in shape, no matter how you stretch or deform them.

What's the connection between manifolds and knot theory?

Knot theory studies how curves (1-dimensional manifolds) can be embedded in 3-dimensional space. A knot can be considered as a 1-dimensional manifold with a specific embedding in 3D. The properties of knots—whether they're the same type or fundamentally different—are studied using manifold techniques and topological invariants. This is an area where manifold mathematics reveals deep relationships between seemingly different geometric objects.

Word Count: 8,847 words | Reading Time: ~44 minutes

Key Takeaways

- Manifolds are spaces that look flat locally but can be curved globally, revolutionizing how mathematicians think about geometry

- Bernhard Riemann's 1854 lecture introduced manifold theory, but it took Einstein's general relativity in 1915 to legitimize these abstract ideas

- Riemannian geometry enables measuring distances and angles on curved spaces through metrics, making calculus possible on manifolds

- Modern applications include Einstein's gravity theory, machine learning dimensionality reduction, cosmology, and understanding high-dimensional data structure

- Manifolds provide a unified mathematical framework for studying any curved space of any dimension, making them fundamental to advanced mathematics and physics

Related Articles

- Therabody Promo Codes & Deals: Save 30-50% [2025]

- Hungryroot Promo Codes & Discounts: Complete Savings Guide [2025]

- Holiday VPN Security Guide: Expert Tips for Safe Festive Season [2025]

- India Startup Funding 2025: Why Investors Got Selective [2025]

- Samsung Music Studio 5 & 7 Speakers: AI Bass Control & Design [2025]

- Japanese PC Maker Halts All Sales After Order Surge [2025]

![What Is a Manifold? The Mathematical Concept That Changed Geometry [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/what-is-a-manifold-the-mathematical-concept-that-changed-geo/image-1-1766907370108.jpg)