How Much Equity to Give First Employees: Real Data & Framework [2025]

You've got a brilliant idea. You've scraped together a small seed round. Now comes the hardest part: convincing someone brilliant to leave a stable job and join you.

The offer? A salary that's probably lower than they'd make at a FAANG company, equity you're trying to convince them will be worth something, and the promise of equity upside. The stakes are enormous. Get the equity split wrong now, and you're still living with those consequences at Series B when you're recruiting your CFO and your option pool is completely underwater.

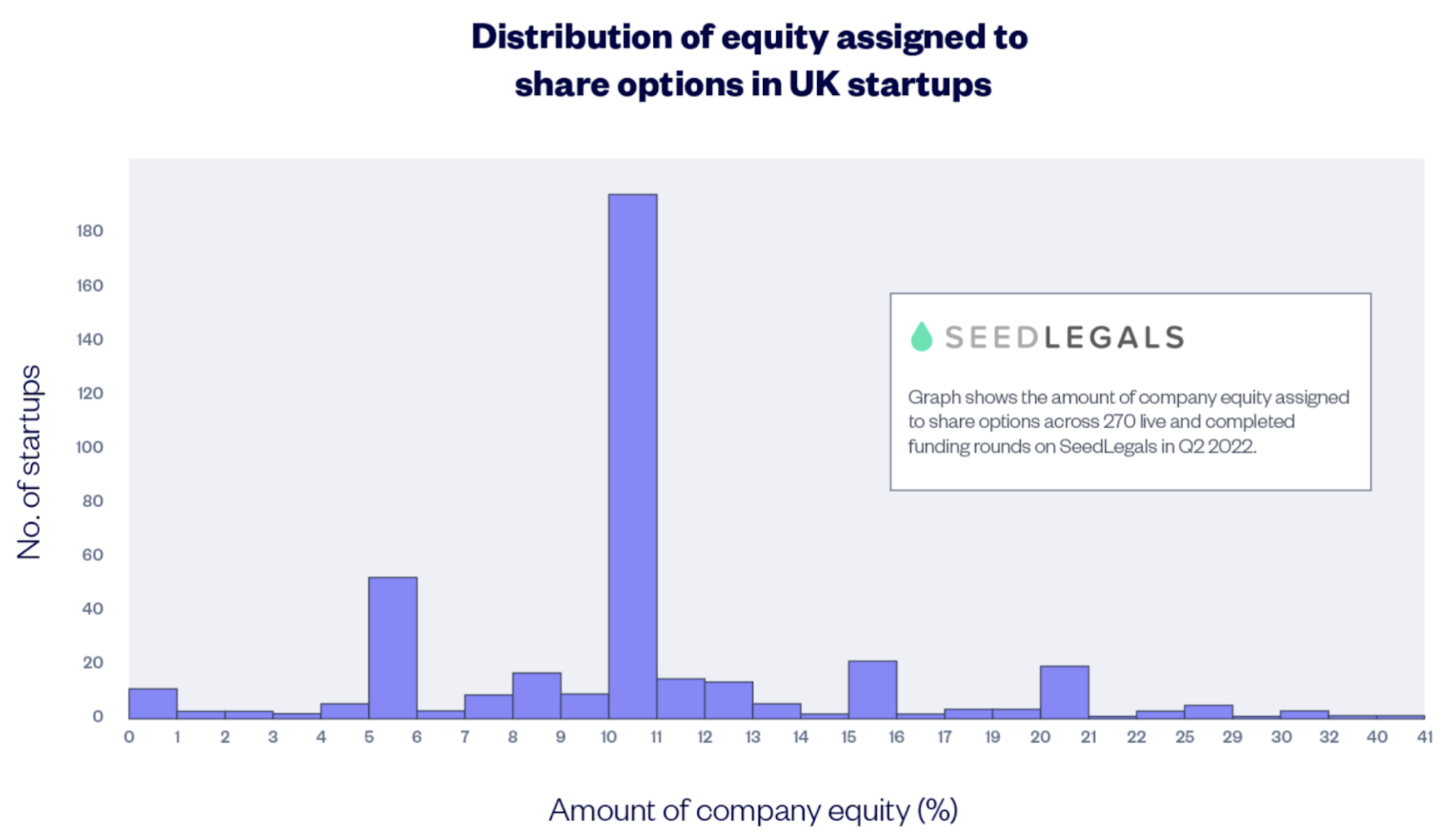

I've watched founders make the same mistakes repeatedly. Some hand out equity like it's candy, only to panic when their Series A dilution math doesn't work. Others are so stingy that they can't attract anyone decent. The truth sits somewhere in the middle, and thankfully, we now have real data to guide these decisions.

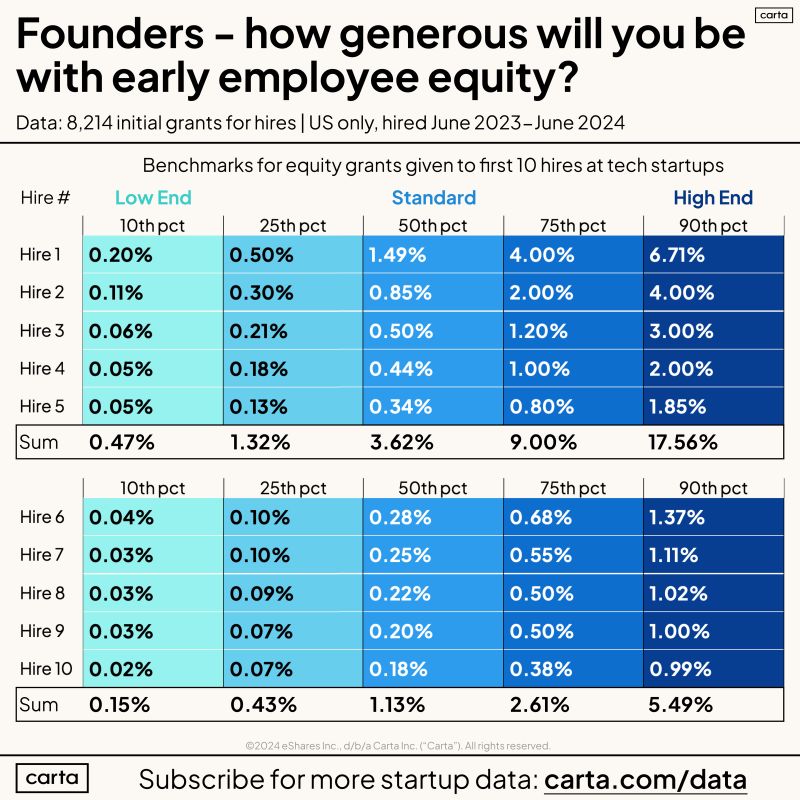

This guide breaks down exactly what successful startups are doing based on analysis of tens of thousands of companies. We're talking real benchmarks, real percentiles, and real mistakes founders actually make. You'll learn the exact ranges for your first five hires, how to think about advisor equity, and the framework for calibrating offers in your specific situation.

Let's start with the headline data and then work backward to understand why these numbers make sense.

The Raw Data: What Your First Five Hires Actually Get

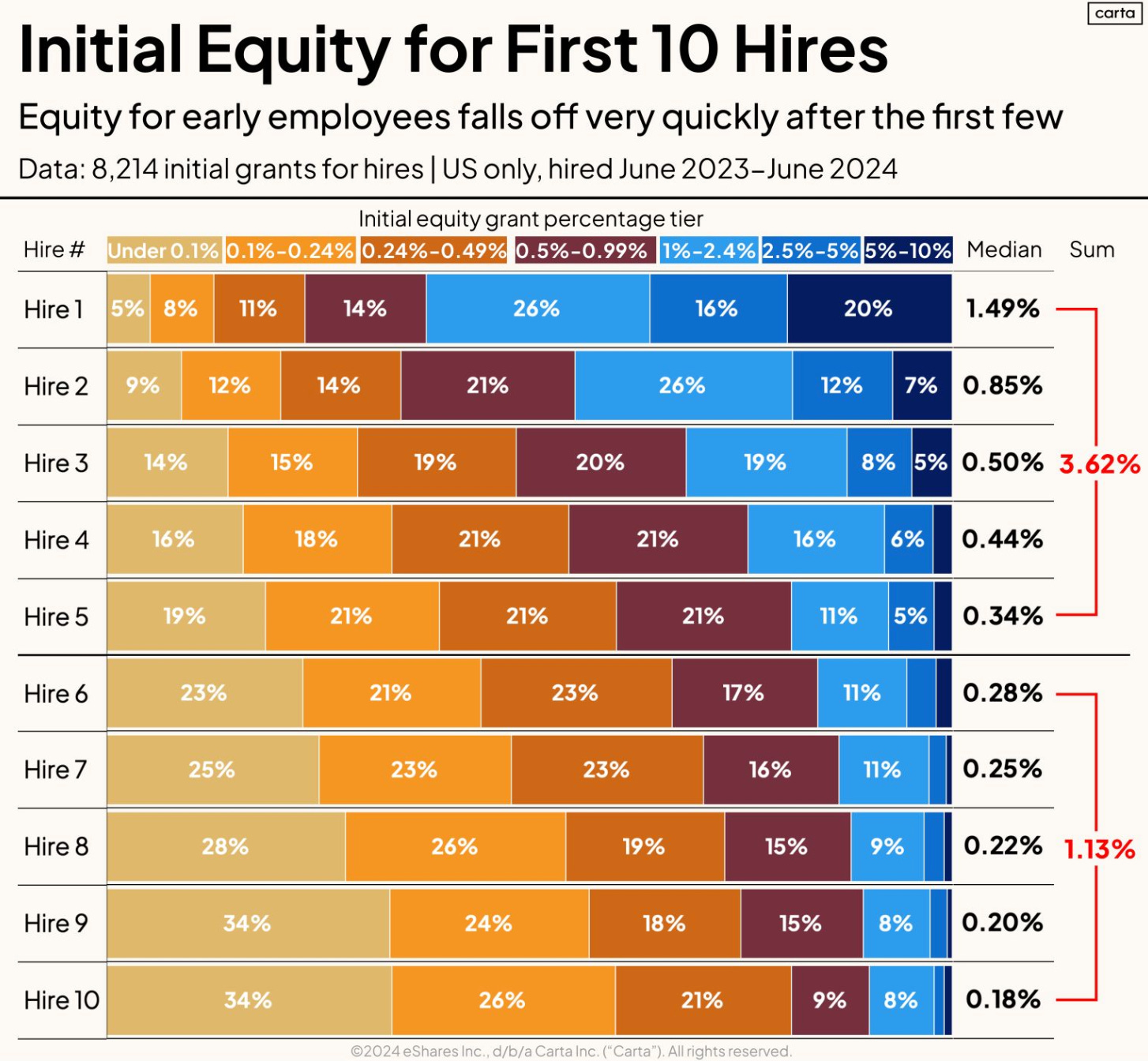

Let's cut straight to it. These are fully diluted equity grants, typically vesting over four years with a one-year cliff. This means the employee gets nothing for the first year, then 25% vests on the one-year anniversary, and the remaining 75% vests monthly over the following three years.

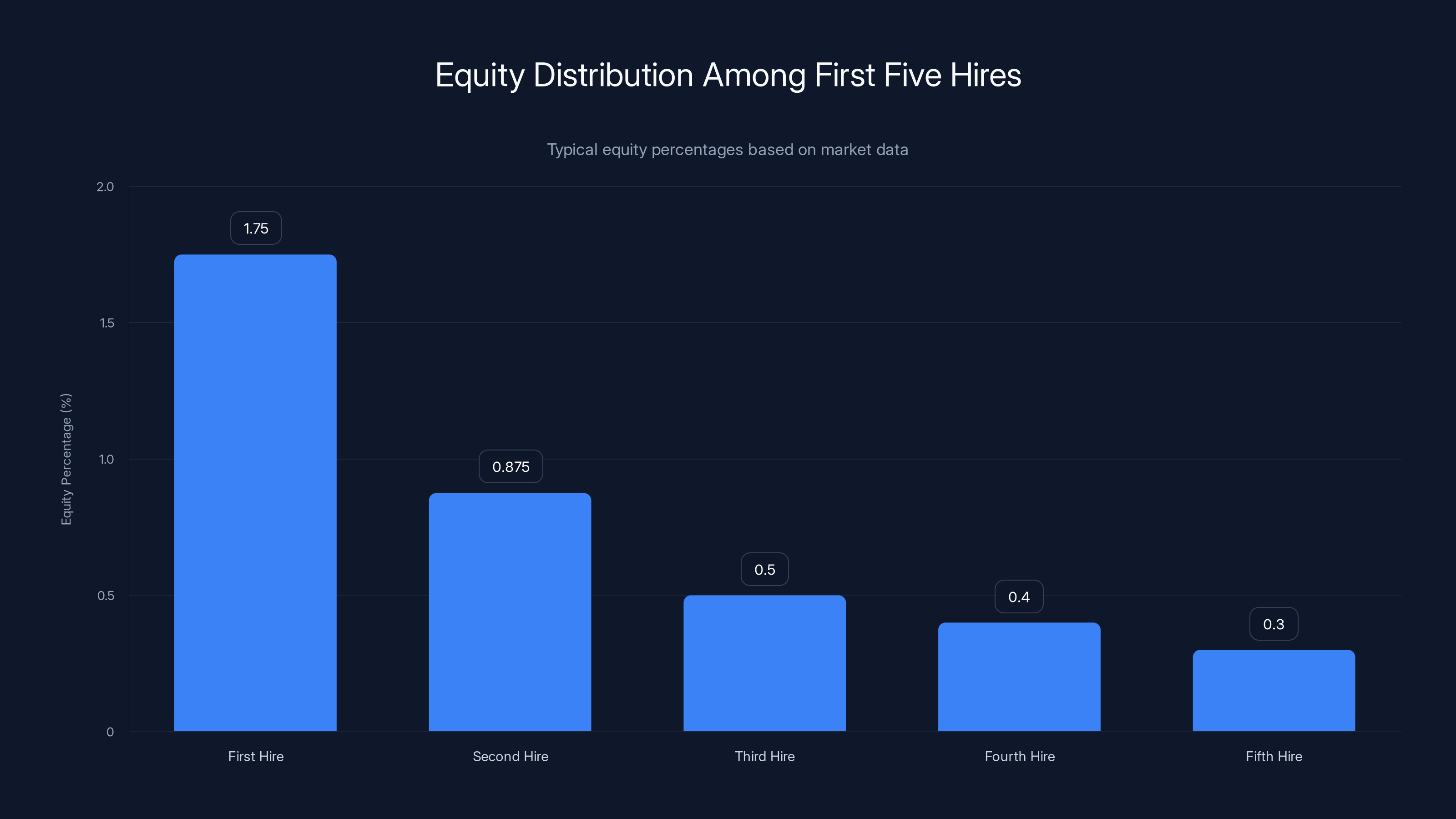

Hire #1: The Special One (1.50% Median)

Your first employee gets 1.50% at median. But here's where it gets interesting. The 25th percentile sits at 0.50%, while the 75th percentile reaches 4.00%. That's an eight-fold spread depending on context.

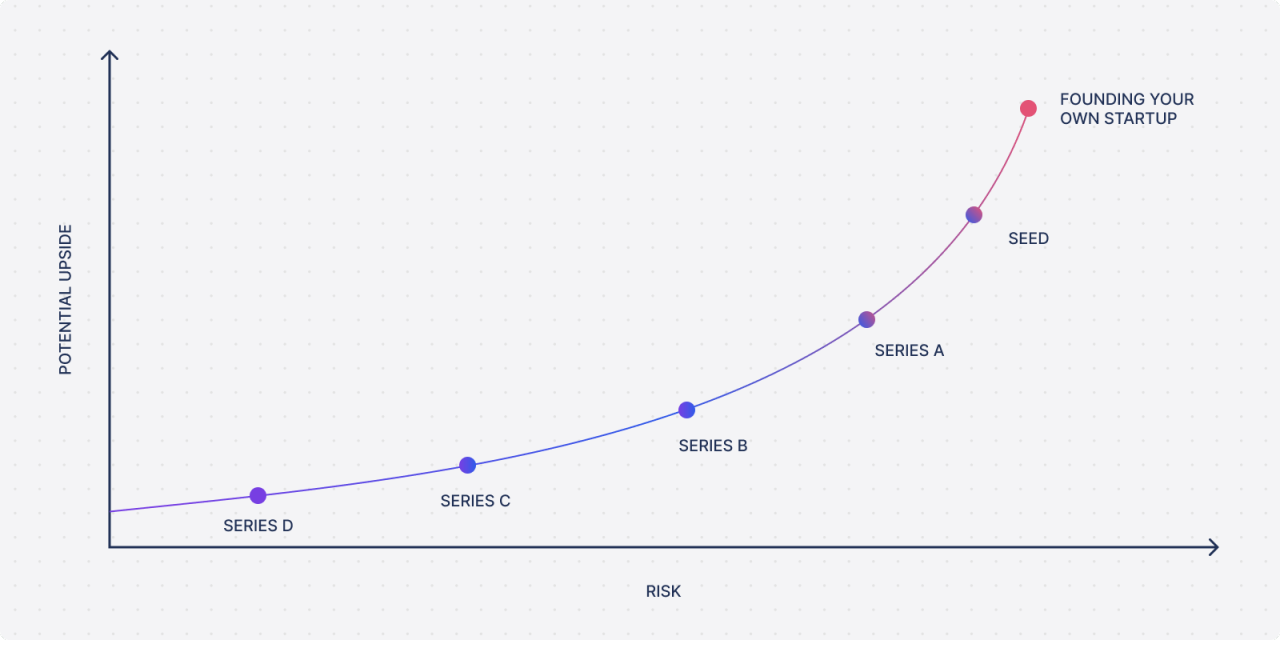

This person is taking the maximum risk. There's no proof of concept, no paying customers (usually), and they're betting on you personally. They're probably walking away from stock options that are underwater at their current company, or a promotion track that was set for them. They need to believe in you and the idea enough to accept that risk.

The range matters because it depends on the person's background. A former CTO from a successful exit? You're probably closer to 2-3% at median. A talented but unproven engineer fresh out of a bootcamp? Closer to 0.75%. Location, salary level, and how desperately you need this role all factor in.

Hire #2: Where It Drops (0.85% Median)

Your second hire gets 0.85% at median. That's a 43% drop from hire #1. Forty-three percent. That's not a small difference.

Why? Because the second hire has something the first one didn't: proof that at least one person competent enough to say yes. The second employee can see that you weren't crazy enough to be completely alone in this. You've de-risked the venture slightly just by successfully convincing someone competent to join.

The percentile range is 0.30% to 2.00%. Still a significant spread, but the downside is lower than hire #1. You're probably not giving someone 0.30% unless they're a junior hire for a very niche role, or you're already further along than true seed stage.

Hire #3: Breaking Below 1% (0.50% Median)

Hire #3 gets 0.50% at median. You've now broken below the 1% threshold. This is what "normal employee" equity looks like for early stage startups. The range is 0.20% to 1.20%, and by this point, you're starting to see real differentiation based on role and seniority rather than just "how risky is this?"

This is the point where you start thinking more carefully about the person's expertise and less about whether you're the first bet on the company. A senior person might get 1%, a mid-level person gets 0.5%, a junior person gets 0.20%.

Hire #4 and #5: The New Normal (0.44% and 0.33% Median)

By hire #4, you're at 0.44% at median. By hire #5, it's 0.33%. The curve is clearly flattening. You've moved from "founding employee" territory into "early employee" territory. The equity isn't quite as much about de-risking the venture and more about competitive compensation for the role.

The pattern stabilizes here. If you're hiring your tenth employee, they're probably getting somewhere in the 0.3-0.5% range at median unless they're a senior hire (VP-level), in which case they might get 0.5-1%.

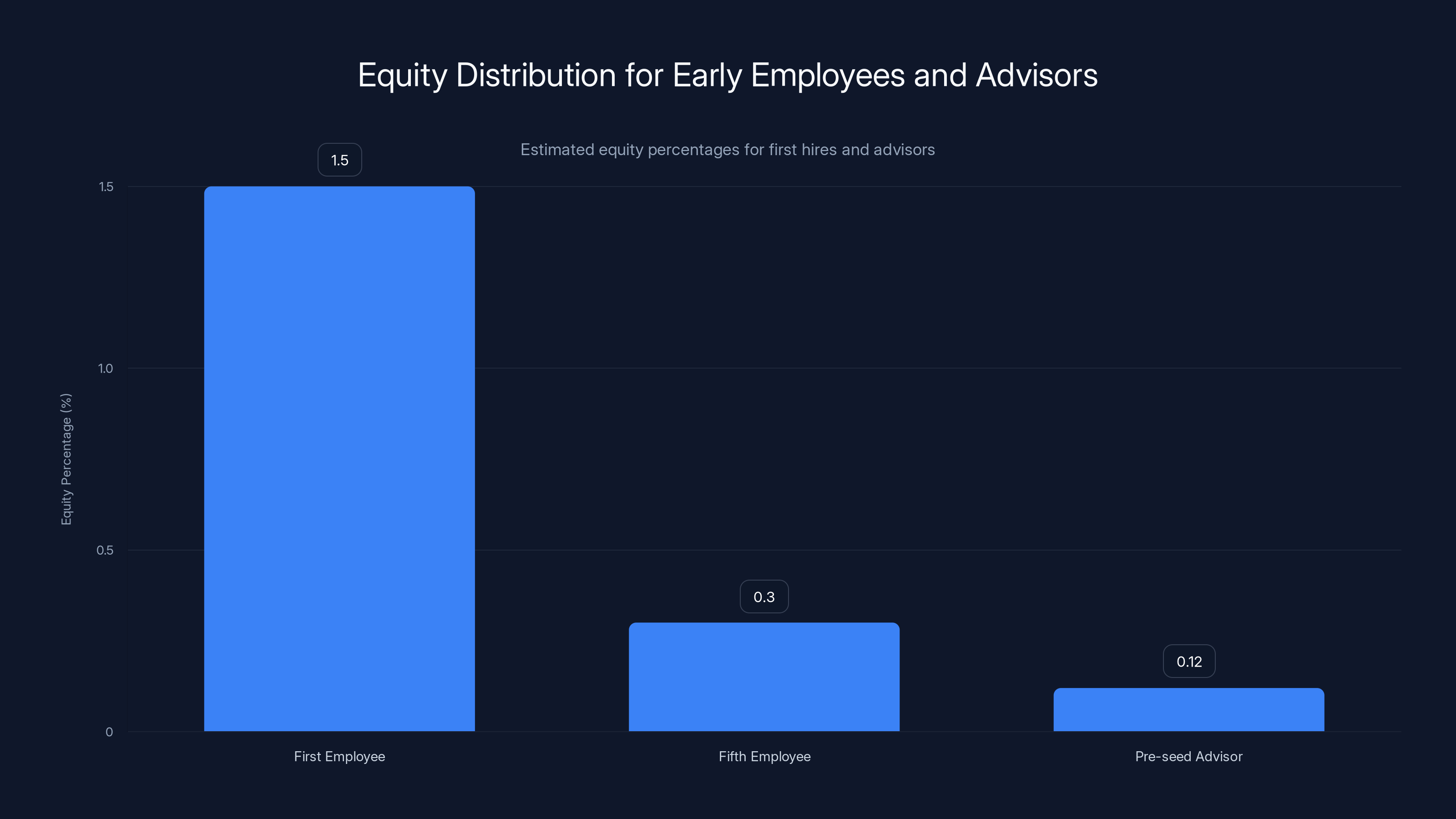

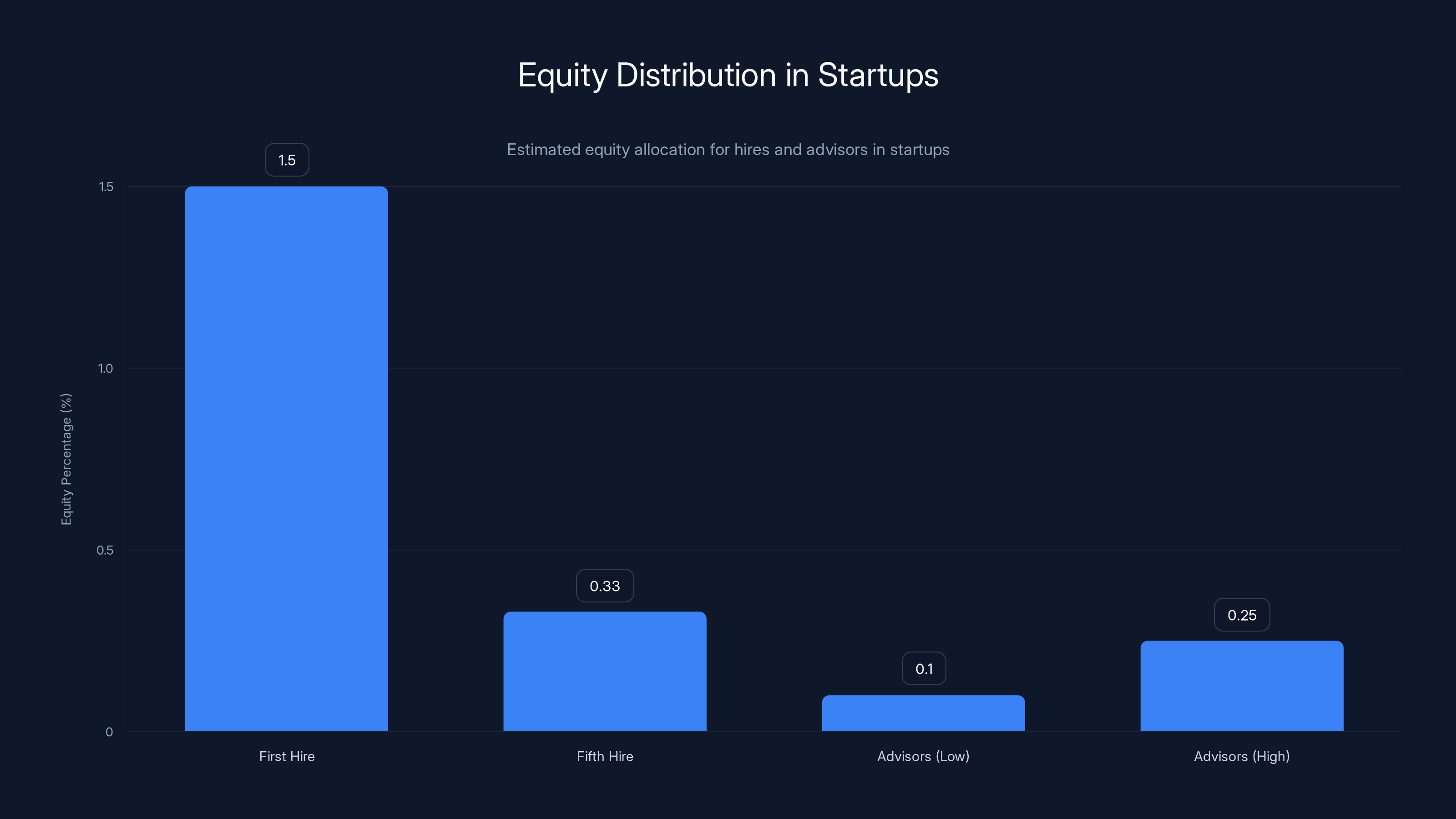

First employees typically receive around 1.5% equity, which is significantly higher than the 0.3% for the fifth hire and 0.12% for pre-seed advisors. Estimated data based on typical startup practices.

Understanding the Equity Drop-Off: Why It Matters

The steep decline from hire #1 to hire #5 isn't arbitrary. It reflects real changes in what you're actually offering as the company scales slightly.

Your first hire is making a binary bet on you and your idea. There's no company yet. There are no customers, no revenue, no social proof. Just you, an idea, and some money that might run out. That person is sacrificing certainty for the chance to build something. They deserve substantial equity.

Your fifth hire is joining a company that has hired four other good people. There's now some organizational proof. You've likely landed at least a few customers (even if they're not paying much). The risk is markedly lower. The decision to accept a lower equity offer is easier because the venture looks more real.

Consider the math another way. If you're giving away the following:

- Hire #1: 1.50%

- Hire #2: 0.85%

- Hire #3: 0.50%

- Hire #4: 0.44%

- Hire #5: 0.33%

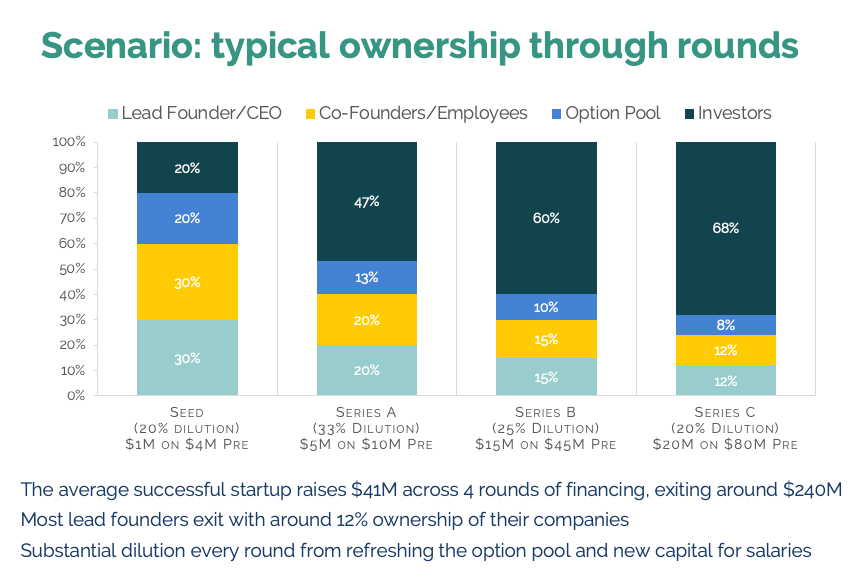

That's 3.62% total across your first five hires. You still have roughly 4-6% typically reserved for your option pool for future employees. You're not at risk of running out of equity to offer senior people at Series A.

But if you gave everyone 1.5%, you'd be at 7.5% across five hires, and you'd be in serious pain when recruiting a VP of Engineering who needs 0.75-1.5% because "that's what the market pays."

The Advisor Equity Trap: You're Probably Over-Granting

Advisors are where founders consistently blow it. You meet someone impressive at a networking event. They seem genuinely interested. You're excited and you offer them a board seat (or just the vague title of "advisor"). Then you give them equity.

The data paints a clear picture of what's actually happening in the market:

Pre-Seed Advisor Equity:

- 25th percentile: 0.09%

- Median: around 0.12%

- 75th percentile: 0.50%

- 90th percentile: 1.00%

Only 10% of pre-seed advisors get more than 1%. Read that again. Only 10%. If someone is asking for 1% or more as an advisor at seed stage, they better be bringing something extraordinary: a key customer, a critical early hire, domain expertise you literally cannot get elsewhere, or a deep investor connection that leads to a check.

Most of your advisors should be in the 0.1-0.25% range with a two-year vest (compared to the four-year vest for employees).

The harsh truth? Many advisors don't actually do anything. They take the equity, maybe introduce you to someone, and then you never hear from them again. When that's the case, you've just paid them something valuable for minimal work.

How to Think About Advisor Grants

Before you hand anyone equity, ask yourself three hard questions:

-

Will this person actively help us recruit our next three hires? If the answer is "maybe" or "probably not," that's a warning sign.

-

Do we have a specific, time-bound project or commitment they're backing up with this equity? "Advisory" shouldn't be vague. It should be: "Help us close our Series A in the next eight months" or "Introduce us to 10 enterprise prospects in the next six months."

-

Could we get this same value from someone else without giving up equity? Sometimes the answer is yes. That person might get a small advisory fee instead of equity.

If you're excited about someone as an advisor, anchor to 0.15% as your starting offer. If they have a legitimate track record with exits or investor networks, you might go to 0.25-0.50%. Anything above 0.50% for a pre-seed advisor should come with real material contributions to the business or board.

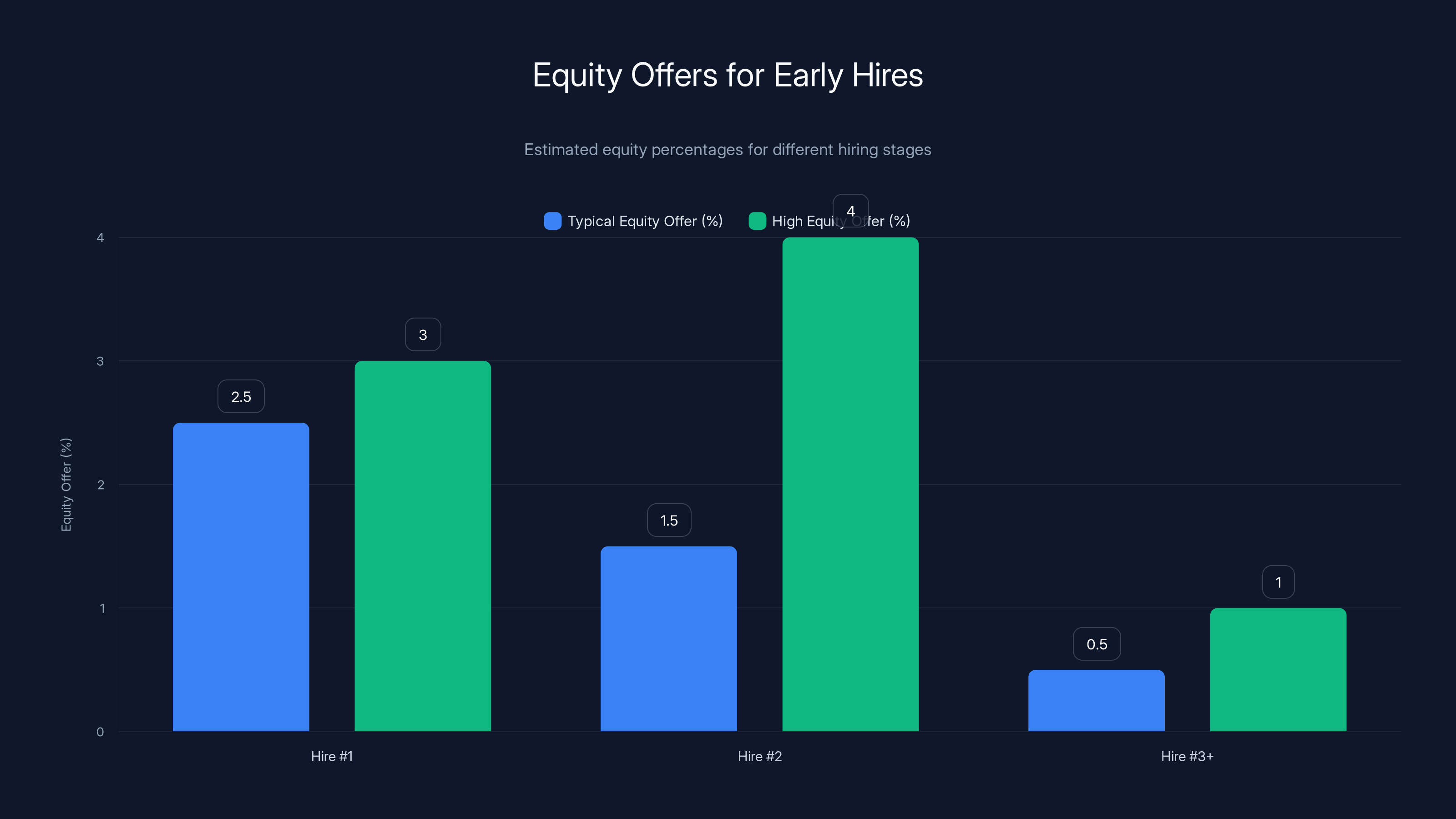

The first hire typically receives significantly more equity (1.5-2%) compared to subsequent hires, reflecting their critical role and contribution. Estimated data based on common equity distribution practices.

The Founder's Four Biggest Equity Mistakes

After looking at thousands of data points, a few patterns emerge. Founders make the same mistakes over and over. Here's how to avoid them.

Mistake #1: Treating Your First Five Hires Like They're All the Same

This is the most common error. You think: "I'll just give everyone on my founding team 1%." Or you give everyone 0.5% because you want to preserve equity.

But the data says the right person at the right time is worth wildly different amounts. Your first employee should get roughly 4-5x what your fifth gets. That's not arbitrary. That's market reality across thousands of companies.

When you flatten this curve, two things happen. First, you under-compensate your first hire, which makes them feel undervalued later ("Why did you only give me 0.75% when you gave person #5 that much?"). Second, you create a precedent that makes it hard to give your third and fourth hires less than your second, even when the data says you should.

Instead, embrace the curve. Your first hire gets 1.5-2%. Your second gets 0.75-1%. Your third gets 0.4-0.6%. Your fourth and fifth get 0.3-0.5%. Make it clear in your head (and ideally in conversation with each hire) why the equity differs.

Mistake #2: Over-Granting to Advisors and Board Members

We've covered this, but it bears repeating. I've watched founders give 1% to someone who sent one email introduction. Or offer board seats with 0.75% equity to people who've never actually built a company.

The median pre-seed advisor is getting 0.12%. Use that as your anchor. If someone is above that number, they should be delivering material value. If they're asking for 1%, they should have a proven track record or a specific, valuable contribution.

When you over-grant to advisors, you're taking equity from the option pool you need to hire your VP of Engineering later. It's shortsighted.

Mistake #3: Not Leaving Room for Senior Hires

You recruit your founding team and hand out the following:

- Hire #1: 1.5%

- Hire #2: 1.0%

- Hire #3: 0.75%

- Hire #4: 0.60%

- Hire #5: 0.50%

- Hires #6-#10: 0.4% each

Total: 7.65% to your first 10 employees.

Now it's Series A. You've raised $2 million. Your board is saying: "We need a VP of Engineering. That person will come from Google or another top startup. They'll need 0.75-1.5% in fully diluted equity."

Where does that equity come from? Your option pool was probably 10-15% to begin with. You've allocated 7.65%. The math doesn't work unless you create new shares, which dilutes everyone.

The lesson: don't give away everything to your first 10 hires. Use the median benchmarks as your guide, but stay a bit conservative. You want to keep 3-4% in reserve for senior hires at Series A and Series B.

Mistake #4: Ignoring the Range and Over-Adjusting for Candidates

The opposite mistake: you see the benchmarks, you panic, and you think every candidate needs to be at the 75th percentile because "we're in San Francisco" or "the market is competitive."

The data shows the range because context matters. A first hire who's a former director of engineering at a Series B startup is worth more than a talented but unproven engineer. A pre-seed advisor with a successful exit under their belt should get more than someone who's never exited.

But don't use "the market is competitive" as an excuse to blow out your budget on every hire. Some of your best early employees will join for less equity because they believe in the mission or they're in a season of life where stability matters less.

Use the data as a framework, not a ceiling. If the 25th-75th percentile range for hire #2 is 0.30-2.00%, and you're recruiting a solid mid-level person, 0.50-0.75% is probably right. You don't need to offer 2%.

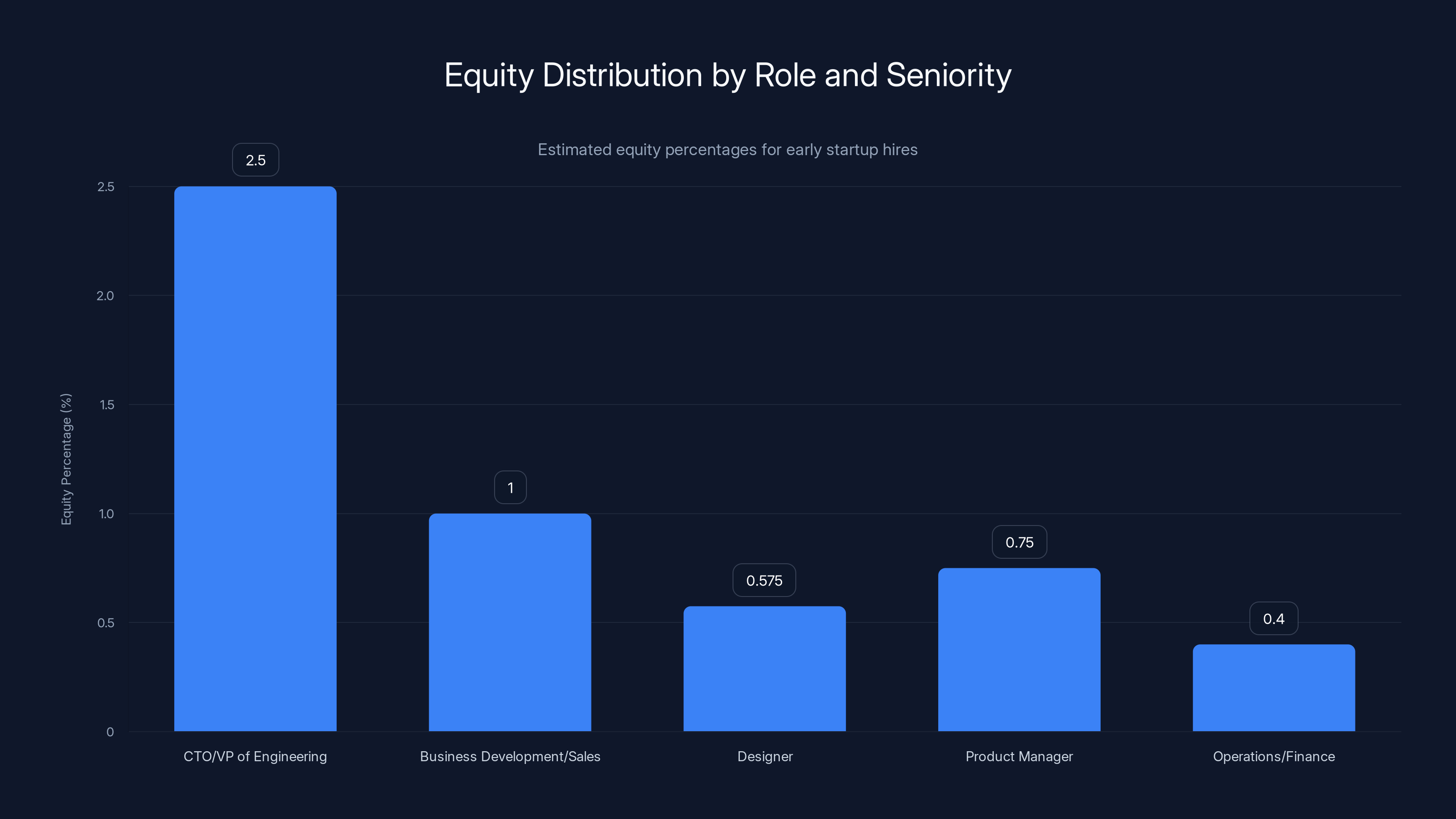

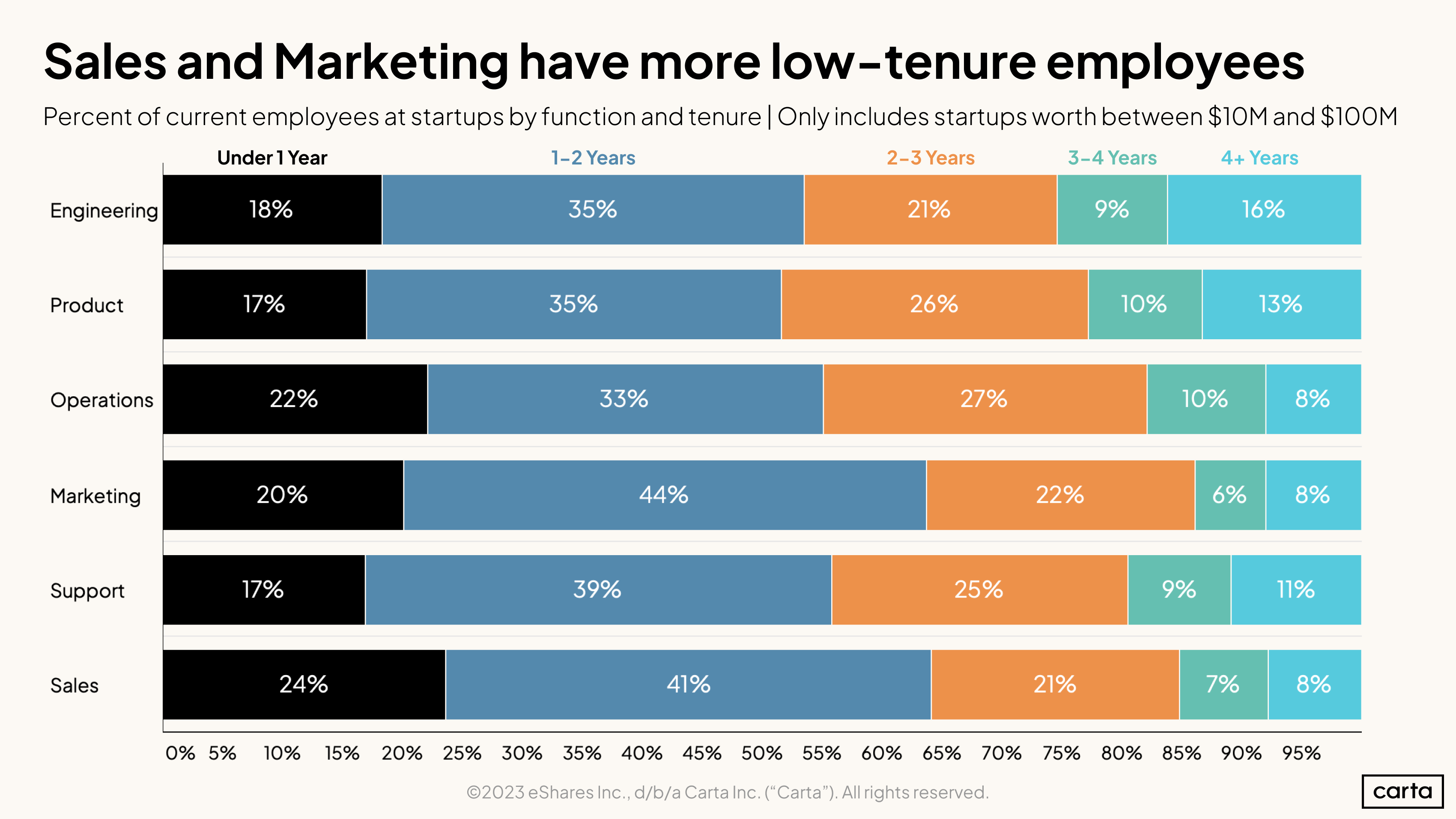

Calibrating Equity by Role and Seniority

The benchmarks give you a starting point, but you need a second layer of thinking: what does this person actually do, and how senior are they?

The CTO or VP of Engineering Early Hire

Your first technical hire might be your VP of Engineering, or at least someone in that direction. This person is building the entire engineering function from zero. They're making architectural decisions that will impact the company for five years.

This person should be at the higher end of the range for hire #1. You're probably offering 2-3%, not 1.5%. Why? Because you're asking them to do the work of three people. They're writing code, recruiting the next engineers, setting up processes, and thinking about infrastructure when it barely matters yet (but will matter in 18 months).

The Business Development or Sales Person

Your first business hire might come at hire #2 or #3. This person is responsible for finding customers and closing deals. They're essentially doing everything pre-sales and sales at a company with zero sales infrastructure.

They should be slightly below the engineering hire but still substantial. If your first hire (the CTO) got 2%, your first sales person might get 0.75-1.2%. Why lower? Because sales equity is often augmented with commission structures. Engineers don't usually get commission (yet), but salespeople do, so the equity is less of the total compensation package.

The Designer or Product Manager

If you're recruiting a designer or product person early (say, hire #2 or #3), they should be in the normal range for that position. A designer gets probably 0.4-0.75%. A product person gets 0.5-1.0% depending on seniority. You're not giving them a massive premium, but you're also not short-changing them.

The Operations or Finance Person

You probably don't hire for operations or finance at the very beginning. But when you do (usually around hire #5-#10), they should be in the 0.3-0.5% range. These are important roles, but you're not getting the same risk premium as your first hire.

That said, if you're hiring someone at this stage who has VC experience and serious investor connections, you might go higher (0.5-0.8%) because they're likely to directly facilitate fundraising.

The Intern or Junior Person

Sometimes you hire young people without much experience. An intern might get 0.05-0.15%. A junior engineer might get 0.1-0.25%. These are real equity grants, but they're smaller because you're essentially paying for training more than experience.

The Fully Diluted Equity Question

When companies talk about equity percentages, they usually mean fully diluted. That means you're counting all shares, including option pools and shares reserved for future fundraising.

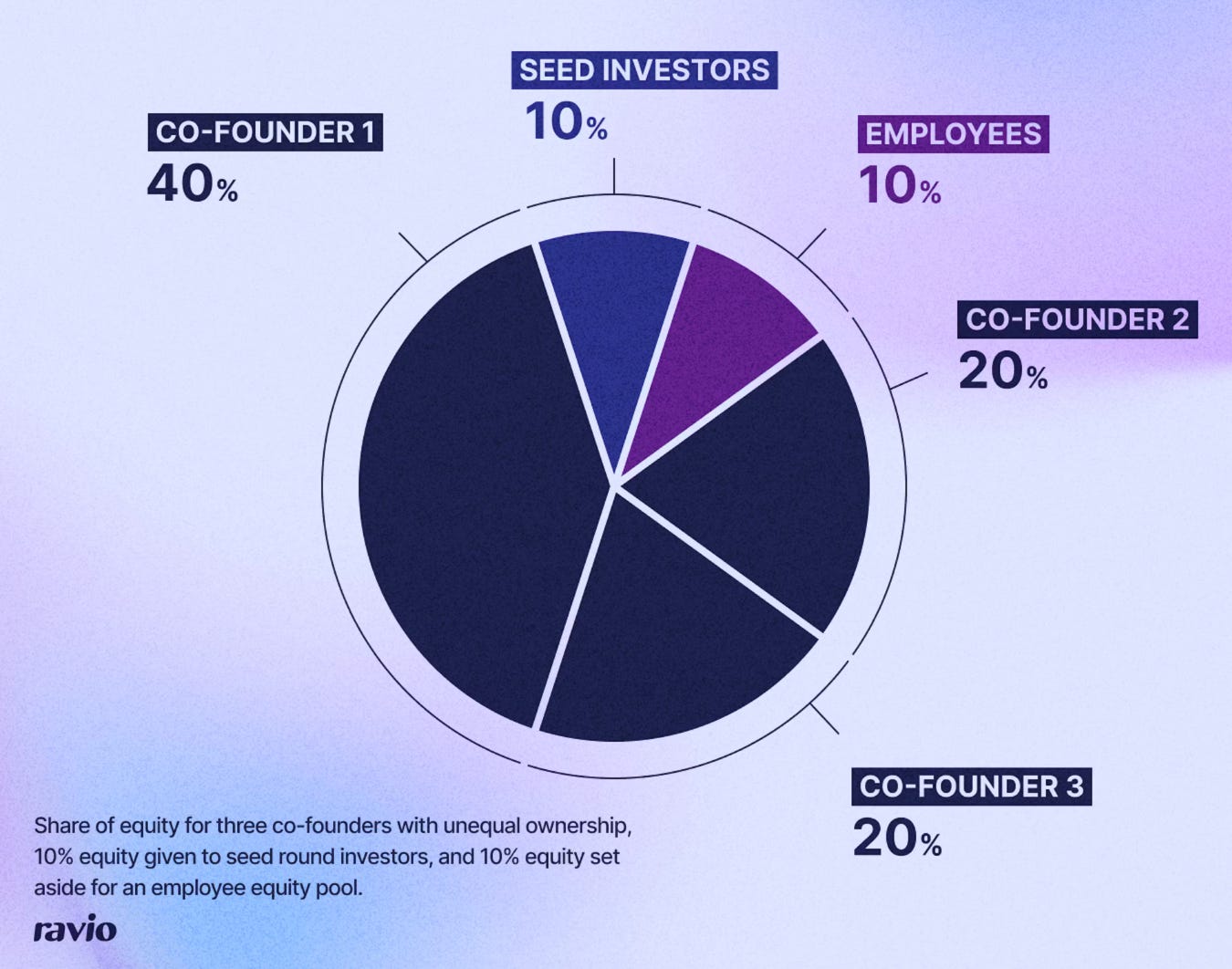

But here's the catch: your current cap table might be different. If you're at seed and haven't raised yet, you might be 100% founders. You then decide you'll have a 10% employee option pool and a 15% future investor option pool. That means you're diluting founders down to 75%, and all your equity grants come from the 25% you've reserved.

So when you say "Hire #1 gets 1.5% fully diluted," you mean 1.5% of the fully diluted cap table (including all future raises and option pools). That's the right way to think about it because it's the number they care about.

If you instead offered them 1.5% of current fully diluted and then raised a Series A that doubled the share count, their 1.5% is now 0.75% (because of dilution). That's not a pleasant surprise.

Always be clear about whether you're talking about fully diluted or current capitalization. The benchmarks in this guide are fully diluted, which is the standard in the industry.

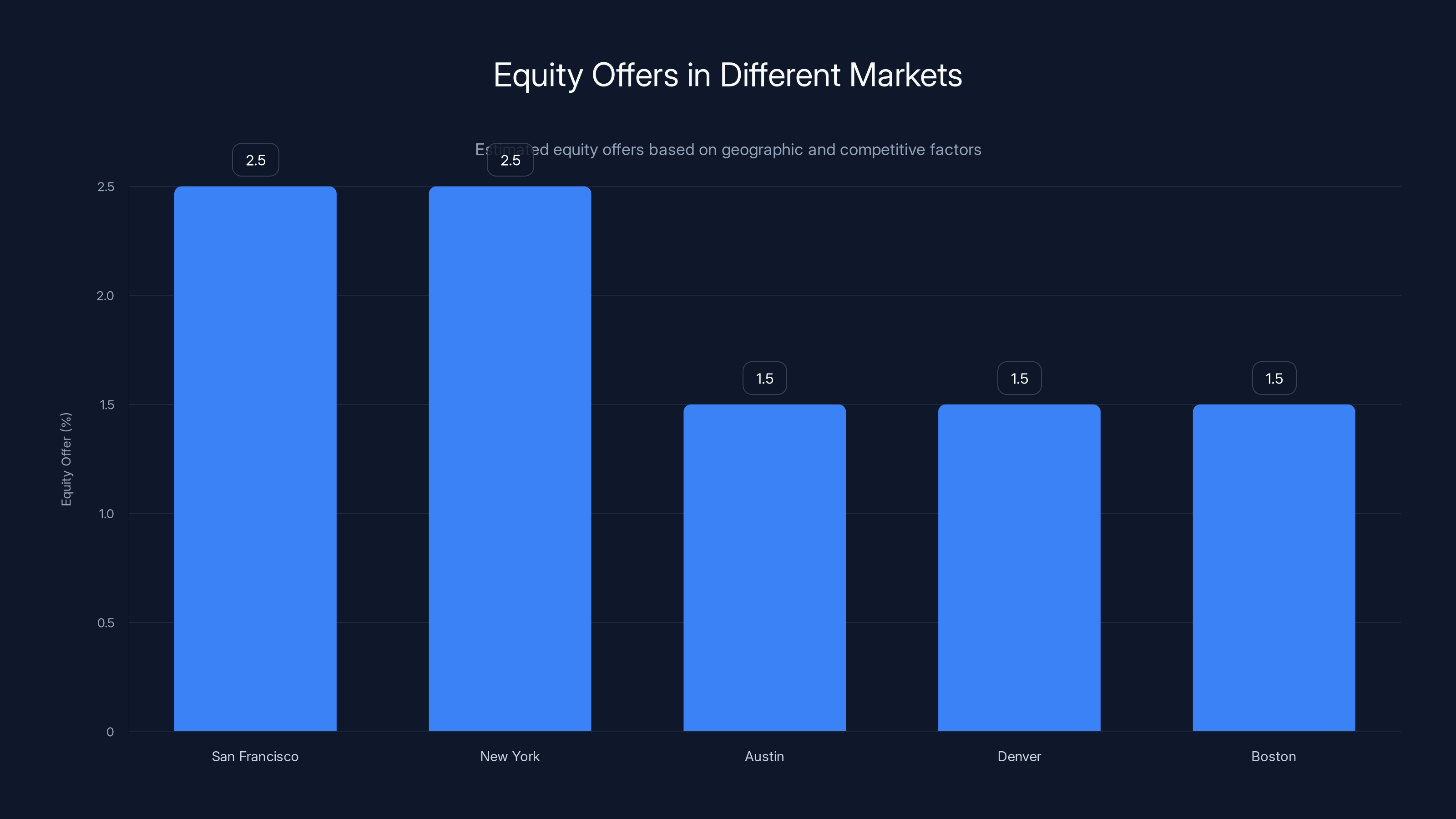

Equity offers tend to be higher in competitive markets like San Francisco and New York, estimated at 2-3%, compared to secondary markets like Austin, Denver, and Boston, where offers are closer to 1.5%. Estimated data.

The Vesting Schedule: Standard Structures and Variations

Before we move on, let's clarify vesting because it impacts how employees think about their equity.

The Standard 4-Year / 1-Year Cliff

Most employee equity uses this structure:

- Total vesting period: 4 years

- Cliff: 1 year (you get nothing if you leave before 12 months)

- After cliff: monthly vesting for the remaining 3 years

Math: If an employee gets 1%, they receive 0.25% on their one-year anniversary, then 0.0208% per month (0.75% / 36 months) for the next three years.

This structure protects the company from paying out equity to people who leave quickly, and it gives employees a strong incentive to stay at least one year.

Advisor Vesting (2-Year / No Cliff)

Advisors typically use different terms:

- Total vesting period: 2 years

- No cliff (sometimes 3-6 month cliff)

- Monthly or quarterly vesting

Advisors get a shorter vesting period because the expectation is that the advice is upfront and ongoing (not concentrated over time like an employee).

Accelerated Vesting Scenarios

Most equity grants have a single-trigger acceleration clause: if the company is acquired or goes IPO, all remaining unvested equity vests immediately. This is standard and expected.

Some offers include a double-trigger acceleration: if the company is acquired and the employee is fired (or quits for good reason), their remaining vesting accelerates. This is less common at seed stage but sometimes included for senior hires.

Geographic and Competitive Considerations

The benchmarks we've discussed are aggregate data. But context matters. Your situation isn't average.

Are You in San Francisco or New York?

Competitive markets see higher equity grants. If you're recruiting a first hire in San Francisco and you're competing with Google, Apple, and three dozen other startups, that person can command a premium. You might offer 2-3% instead of 1.5%.

Conversely, if you're in a secondary market (Austin, Denver, Boston), you might offer closer to the 25th percentile of the range. The person might be locally competitive even with lower equity.

This isn't absolute. Great people are everywhere, and many people choose to work on an interesting problem even if the salary and equity are local-market rates rather than San Francisco rates.

What Stage Are Your Competitors At?

If every other startup in your space is backed by a mega-fund at Series B with much more capital, your salary and equity budget might need to be higher to compete. If your competitors are all bootstrapped, you might be able to get away with less equity.

But be honest with yourself. If you're trying to recruit the same person that a better-funded startup is recruiting, and that person is worth more to you than to them (because of the role or the opportunity), you might need to pay up.

Founder Runway and Burn Rate

If you've got 24 months of runway and you're unlikely to fundraise, you can offer more equity because it's genuinely risky. If you've got 36+ months or a clear path to fundraising, you might offer less because the risk profile is lower.

Be honest about this. Don't offer massive equity to people joining a company that's clearly going to run out of money in 12 months unless that person understands and accepts that risk.

The Negotiation: When Candidates Ask for More

You've made an offer. It's within the benchmarks. And then the candidate comes back and asks for more equity.

How do you handle it?

If They're in Hire #1-#2 Territory

If this is your first or second hire and they're asking for more, step back and ask yourself: do I actually need this person that badly? If the answer is genuinely yes, the data might support offering more. Your first hire is special, and sometimes the right person is worth 2.5-3% instead of 1.5%.

But if they're asking for 4% for hire #2 and that's the 75th percentile, that's a real decision point. Is this person worth that much premium? Can you get similar value from someone else at a lower equity grant?

If They're in Hire #3+ Territory

If this is hire #3 or later and they're asking to break significantly above the range, you have more leverage. The market has spoken. If they don't want to accept 0.5% for hire #3 when the data shows 0.2-1.2%, they can look elsewhere.

That said, sometimes you find someone exceptional at hire #3 who's also talking to bigger companies. In that case, you might stretch to 0.75-1%. But do it with eyes open that you're above market, and it'll set expectations for future hires.

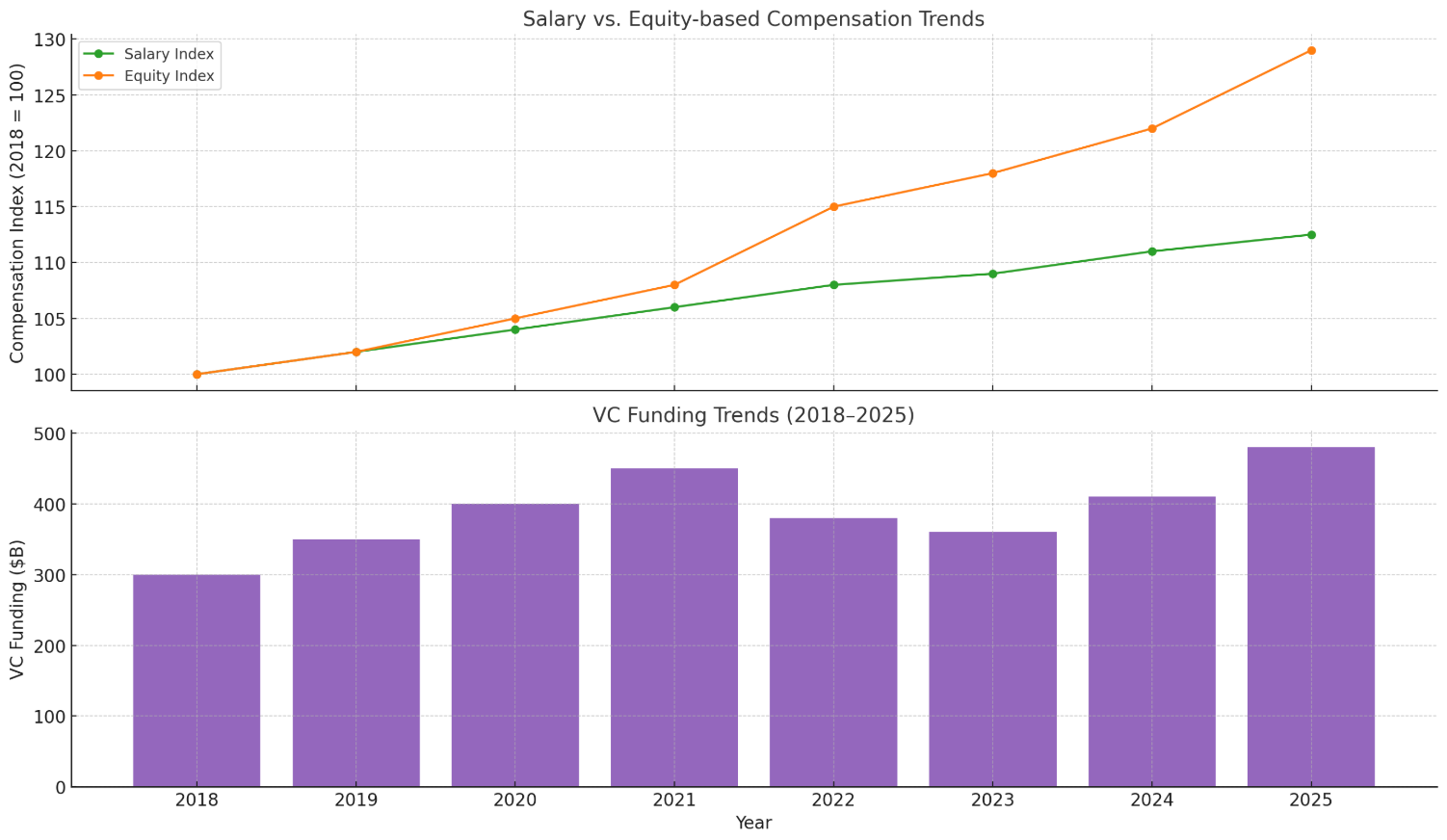

The Salary vs. Equity Trade-Off

When someone asks for more equity, sometimes the answer is: "We can go higher on salary instead." This works if you have cash runway but not if you're strapped.

Be explicit about the trade-off. "We can offer you

Equity offers vary by hiring stage, with early hires potentially receiving higher percentages. Estimated data based on typical startup practices.

What Happens at Series A: Dilution and Secondary Rounds

Your first hires are now vested for a year or more. They've believed in you. They've worked hard. And then you raise a Series A.

Let's say you raise at a $10M post-money valuation and the VCs take 20% of the company. Everyone's equity gets diluted by 20%. Your first hire's 1.5% becomes 1.2%. Their options are now worth less.

This is inevitable and expected, but it's worth discussing with your team when you raise. Be transparent about dilution. Show them the math. Explain that it's normal and that the company is now worth more even though their percentage is smaller.

Some founders include a secondary round at Series A where existing shareholders can sell a small percentage of their equity (like 10-20% of their vested shares) to new investors. This gives early employees some liquidity and a chance to take some chips off the table. It's not required but it's increasingly common and it's a good sign of founder respect for early team members.

Special Cases: The Solo Founder and the Co-Founder

We've been assuming a team of co-founders. But sometimes you're a solo founder, and you need to hire your first person.

As a solo founder, your first hire gets even more important equity because they're simultaneously early employee AND (partially) co-founder. You might offer 2-3% instead of 1.5% for someone truly exceptional joining a solo founder, because the risk is higher.

You might also consider converting that first person to a co-founder instead of an employee. If they're genuinely a peer and you want to split the company 50-50, that's a different conversation entirely. But that's beyond the scope of this guide.

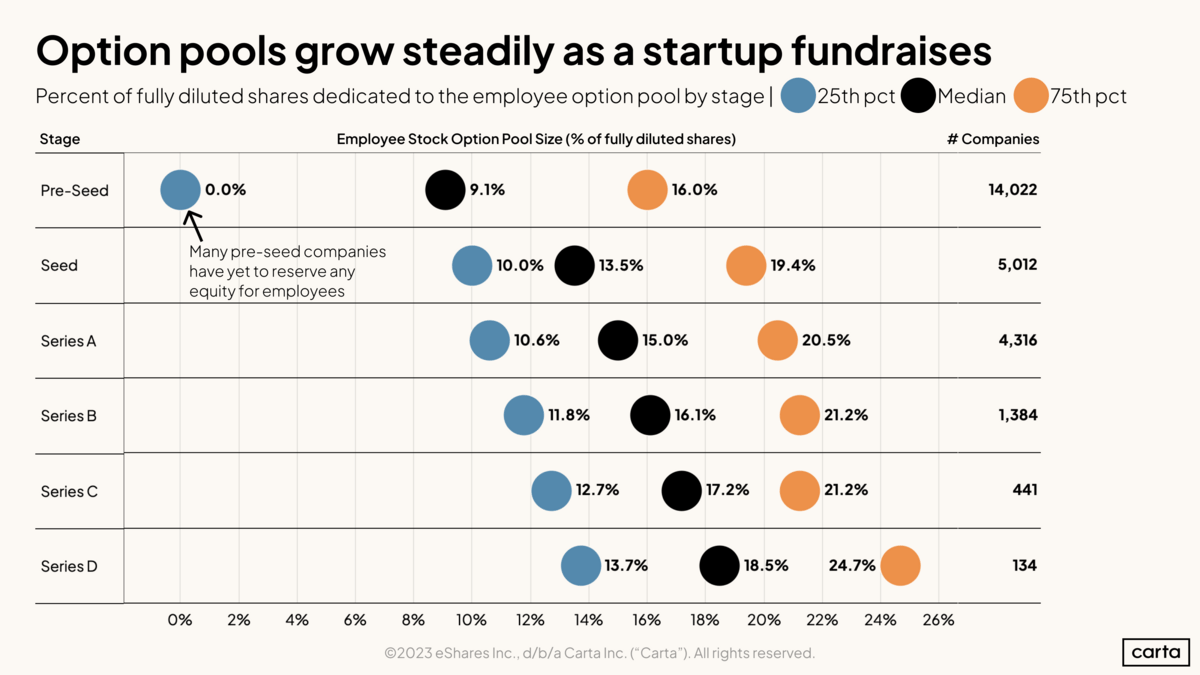

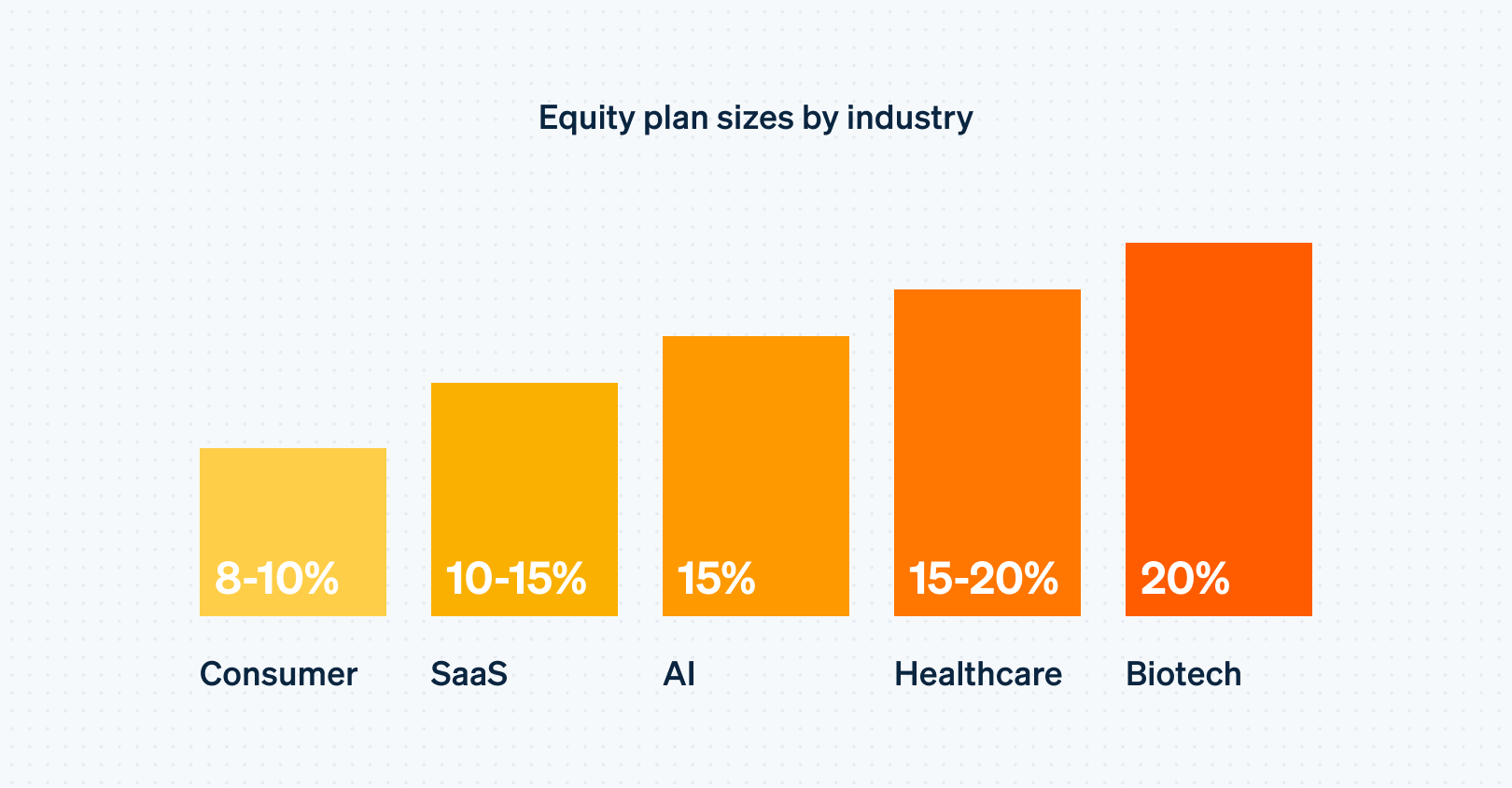

The Option Pool and Future Hiring

When VCs invest, one of the first things they'll ask about is your option pool. They want to make sure you have equity reserved for future hires, and that you haven't given away so much to early employees that there's nothing left for senior people.

A typical option pool is 10-15% of the post-money valuation at seed stage. You use this to hire employees in the first year or two.

If you've given away 7-8% across your first 10 hires and you've got a 12% option pool, you've got 4-5% left for your next 20 hires. That's workable, but it's getting tight. If your founder equity is 72%, your investor owns 12%, and your employee pool is 15%, and you've allocated 8%, you've got 7% in reserves. That's thin.

When you're granting equity to early hires, keep an eye on the total. You want to leave room to recruit senior people without creating new shares.

CTO/VP of Engineering typically receives the highest equity (2-3%) due to their critical role in early development, while roles like Operations/Finance receive less (0.3-0.5%) as they are hired later. Estimated data based on typical startup practices.

The Paperwork and Legal Stuff

Once you've decided on an equity grant, you need to document it properly.

The Offer Letter

Your offer letter should specify:

- Number of shares (or options) granted

- Vesting schedule (4 years, 1-year cliff for employees)

- Strike price (usually the fair market value on the grant date)

- Accelerated vesting provisions (usually single-trigger on acquisition)

- Any other terms (clawback clauses are rare at seed stage)

The Stock Option Plan (ESOP)

You need an actual equity plan that governs all of this. This is a legal document that defines how equity works at your company. It's worth spending $1-2K with a startup lawyer to set this up properly instead of copying a template from the internet.

The ESOP defines:

- Number of shares in the company

- How options are granted and vested

- What happens if someone leaves

- What happens if the company is acquired

- The option exercise price and how it's calculated

Tax Implications (For Employees)

Stock options at startups have tax implications. When an employee exercises their options (buys them at the strike price), they pay taxes on the difference between the strike price and the fair market value. This can get complicated if the company is worth a lot but has no way to pay the taxes.

There are two types of options: incentive stock options (ISOs) and non-qualified options (NSOs). ISOs have better tax treatment, but they have limitations on who can receive them and in what amounts. Most seed-stage startups use ISOs for employees and NSOs for advisors and consultants.

This is a conversation to have with a good startup tax accountant, not something to figure out yourself.

The Psychology and Culture Impact

Here's something the data doesn't capture: how your equity decisions affect company culture.

If your first hire finds out you gave your fifth hire almost as much equity as them, they feel undervalued. If an advisor walks away thinking they're getting equity for introductions and then the CEO never follows up, they feel resentful.

The best founders are transparent about equity from the start. They explain the ranges, they show the data, they make clear why hire #2 gets less than hire #1. They're generous with advisors who deliver value and conservative with those who don't.

They also understand that equity is just one part of total compensation. Sometimes salary, title, or responsibility matters more. A senior person might take 0.5% equity for

Know what motivates each person and structure the offer accordingly.

Common Errors and How to Avoid Them

Error #1: The Over-Generous First Round

You're excited. You think your first hire is amazing. You offer 3%. Then your second hire is also amazing. You offer 2%. Then your fifth hire looks at the vesting cliff and realizes they're getting nearly as much as your first hire and they're furious.

Avoid this by anchoring to the data upfront. You're not being cheap by offering 1.5% to hire #1 and 0.33% to hire #5. You're following what successful companies do.

Error #2: The Vague Option Grant

You tell someone "you'll get some equity" but you never write down the details. A year later, when they ask for the actual paperwork, you're scrambling.

Fix: put it in the offer letter. Make it specific. "You will receive an option grant of [X] shares representing [Y]% fully diluted equity, vesting over 4 years with a 1-year cliff."

Error #3: The Advisor Who Vanishes

You grant 0.5% to an advisor. They never deliver anything. Now you're stuck with them on your cap table, and you can't issue new equity without diluting them.

Fix: set advisor agreements with specific terms. "You're an advisor for 12 months, advising on business development. We'll check in quarterly. If this isn't working after 6 months, we'll revisit the arrangement." This gives you an out if the person is truly not helpful.

Error #4: The Cliffhanger

Your first hire leaves after 11 months (just before the vesting cliff). They get nothing. It's technically legal, but it sours the relationship and it's bad for your reputation.

Some forward-thinking founders negotiate cliff waivers: "If you leave before the cliff but we part on good terms, we'll vest [X]% of your equity." This costs you a small amount of equity but it's goodwill money that's often worth it.

Equity allocation decreases significantly from the first to the fifth hire, reflecting changes in company risk and employee value. Advisors typically receive between 0.1% and 0.25%, highlighting the importance of careful equity planning. Estimated data.

Planning Your Option Pool for the First Year

Let's say you're raising a $500K seed round and you're planning to hire 8-10 people in the next year. How much equity should you set aside?

A typical option pool is 10-15% of the post-money valuation. If you're raising a

You might reserve 12% of the post-money for employees, advisors, and option pool. That gives you:

- 240K in fully diluted equity to allocate

If you hire 8 employees and 3 advisors, and you're allocating roughly:

- Hire #1: 1.5% ($30K value)

- Hire #2: 0.85% ($17K value)

- Hires #3-8: 0.3-0.5% each ($6-10K each)

- Advisors: 0.1-0.25% each ($2-5K each)

You're around

If you'd given away 2% to each of your first 8 hires, you'd be at $320K, which is more than your entire pool. Now you can't hire anyone else without diluting existing shareholders.

The Future: Series A and Beyond

As your company grows, equity becomes less of your total compensation package and more about alignment and incentive.

At Series A, you're hiring senior executives who come with market demands. A VP of Engineering from a Series B company expects 0.75-1.5% depending on the size of the new raise. That's just the market.

At Series B, equity is even less of the total package. People are looking at cash salary, benefits, and the probability of an exit. The equity is important, but it's not the driver.

By Series C+, equity is largely symbolic (though meaningful if there's a real path to exit). People want cash salary and they want to know the company is headed toward a good outcome.

But it all traces back to how you handled your first five hires. Get that right and you've got the runway. Get that wrong and you're constrained.

Your Equity Framework Going Forward

Let's synthesize all of this into a practical framework you can use.

Step 1: Know Your Benchmarks

- Hire #1: 1.5% (range 0.5-4%)

- Hire #2: 0.85% (range 0.3-2%)

- Hire #3: 0.5% (range 0.2-1.2%)

- Hire #4: 0.44% (range 0.18-1%)

- Hire #5: 0.33% (range 0.13-0.8%)

Advisor: 0.12% (range 0.05-1%)

Step 2: Calibrate for Your Situation

Are you in a competitive market? Go higher. Secondary market? Go lower. Do you have long runway? Can offer more. Burning fast? Be conservative.

Step 3: Adjust for the Specific Person

Is this hire exceptional or good? Are they taking a step down from their current role or a step up? Have they exited before? Do they have important relationships?

Use the benchmark range to position the offer.

Step 4: Structure Vesting Carefully

- Employees: 4 years, 1-year cliff

- Advisors: 2 years, monthly vesting

- Single-trigger acceleration on acquisition (standard)

Step 5: Plan Your Option Pool

Reserve 10-15% of post-money valuation for employees. Be conservative in your early hiring. Leave room for senior people later.

Step 6: Be Transparent

Explain your reasoning. Show the benchmarks. Make it clear why hire #2 is getting less than hire #1. People respect clarity more than they resent lower numbers.

Key Takeaways

The data from thousands of startups is clear: equity drops fast, advisors get less than you think, and the curve matters more than the absolute numbers. Your first hire gets roughly 1.5% at median. By hire five, they're at 0.33%. That 4-5x difference reflects real changes in company risk and employee value.

Most advisors should be at 0.1-0.25%, not 0.5-1%. Over-granting to advisors is one of the most common founder mistakes.

Use the benchmarks as a framework, but calibrate for your specific situation. A hot market in San Francisco allows for higher equity. A secondary market or slow fundraising allows for lower. Exceptional people might get above-range offers. Good people should get market offers.

Plan your option pool before you start hiring. You want to leave 3-4% in reserve for senior hires later. Running out of equity is a real constraint that limits your ability to recruit senior executives.

Be transparent with your team about dilution, vesting, and why equity differs. Early employees care less about their absolute percentage and more about feeling like they were treated fairly in the moment.

FAQ

What percentage of equity should I give my first employee?

Your first employee should receive between 0.5% and 4% fully diluted equity, with a median of around 1.5%. The exact number depends on their seniority, background, and what you're asking them to build. A first hire who's a former director of engineering gets more than a junior engineer joining as hire #1. Use the median as an anchor and adjust upward if the person is exceptional or downward if they're earlier in their career.

How much equity should I give an advisor?

The median pre-seed advisor gets about 0.12% in equity with a two-year vesting schedule and no cliff. Only about 10% of pre-seed advisors get more than 1%. Unless someone is bringing a key customer, critical hire, or significant investor connection, they should be in the 0.1-0.25% range. Avoid the common mistake of over-granting to advisors who only send one introduction.

Why does equity drop so much between my first and fifth hire?

Equity drops because the company is de-risking. Your first hire has no proof the company will succeed—they're betting purely on you and the idea. By your fifth hire, you have four other competent people on the team, you likely have some customers or at least customer interest, and the venture is objectively less risky. The market reflects this by offering less equity. A 4-5x difference between hire #1 and hire #5 is normal and expected across thousands of data points.

Should I use the same equity percentage for all my early employees?

No. Using the same percentage for different hires is a common mistake. Your first hire should get roughly four to five times what your fifth hire gets at median. The data clearly shows this curve exists across thousands of successful startups. Flattening the curve means under-compensating your first hire and setting bad expectations for later hires. Instead, embrace the curve and be transparent about why equity differs.

What happens to my employees' equity when I raise a Series A?

When you raise a Series A, all shareholders (including employees with vested equity) get diluted proportionally. If investors take 20% of the company, everyone's percentage drops by about 20%. This is normal and expected. If an employee had 1%, it becomes 0.8% after the round. However, the company is now worth more, so the actual value of their equity may have increased even though the percentage is lower. Be transparent with your team about how dilution works before you raise.

How much equity should I reserve for my option pool?

Most startups reserve 10-15% of the post-money valuation for employees, advisors, and the option pool. This allows you to hire 10-20 people in the first year or two without creating new shares. Be conservative in your early hiring to leave room for senior executives at Series A and Series B, who will typically require 0.5-1.5% in equity. If you give away too much to your first five hires, you'll have nothing left for senior people later.

What vesting schedule should I use for equity?

The standard is four years with a one-year cliff for employees. This means they get nothing if they leave before 12 months, then 25% vests on the one-year anniversary, and the remaining 75% vests monthly over the next three years. Advisors typically use a two-year vesting schedule with no cliff or a shorter cliff. Include a single-trigger acceleration clause so all remaining equity vests immediately if the company is acquired or goes public.

Is it better to offer more salary or more equity?

This depends on the person and your runway. If you have 24+ months of cash runway, you can afford to offer a competitive salary and reasonable equity. If you're burning fast and might run out of money, the equity is riskier and you might need to be more generous with it as compensation for the risk. Some people prefer salary and stability; others prefer equity upside. Structure the offer to match what motivates each specific hire. You might offer the same total compensation in different ratios:

What's the difference between incentive stock options and non-qualified options?

Incentive stock options (ISOs) have better tax treatment for employees but they have limitations on who can receive them and in what amounts. Non-qualified options (NSOs) can be given to anyone with worse tax treatment. Most seed-stage startups use ISOs for employees and NSOs for advisors and consultants. The difference matters for tax purposes, but it's a conversation to have with a startup accountant, not something to figure out alone.

Should I accelerate vesting if an employee leaves after they've vested for a year but before the cliff?

This is optional but increasingly common. Some founders include a cliff waiver that says: "If you leave before the cliff but we part on good terms, we'll vest 25% of your equity anyway." This costs a small amount of equity but it's goodwill money that prevents resentment. If someone leaves at month 11 and gets nothing, they'll remember you negatively. If you vest 25% and they feel treated fairly, they might refer customers or future employees to you.

How do I know if I'm being generous or stingy with equity?

Use the benchmarks. If you're offering within the 25th-75th percentile range for the specific hire number, you're roughly in the market. If you're below the 25th percentile, you're probably being stingy and you'll have trouble recruiting. If you're consistently above the 75th percentile, you're being generous (and you'll run out of equity quickly). The right approach is to be selectively generous for exceptional people and more conservative for solid but typical hires.

Conclusion

Equity decisions haunt founders. You make the offer, the person accepts, and for the next three to five years you're living with the consequences. It affects company culture, your ability to recruit later, and ultimately whether this person feels respected and valued.

The good news? You don't have to guess anymore. Thousands of successful startups have shared their data. The pattern is crystal clear. Your first hire gets roughly 1.5%. By hire five, it's 0.33%. Advisors get 0.12% at median. The ranges exist because context matters, but the aggregate data is solid.

Use this data as your framework. Know the benchmarks for each hire. Calibrate for your specific situation. Leave room in your option pool for senior people later. Be transparent with your team about why equity differs between people. And remember: equity is important, but it's just one part of why someone joins your company. Belief in the mission, respect for the founder, and the opportunity to build something real matter too.

Get your equity offers right, and you'll attract great people who'll stay with you through the hard parts. Get them wrong, and you'll spend the next three years fighting about who got what.

Choose wisely.

![How Much Equity to Give First Employees: Real Data & Framework [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-much-equity-to-give-first-employees-real-data-framework-/image-1-1767368278439.jpg)