How Museums Use Ancient Scents to Transform Egyptian Exhibits

Walk into most museums and you're hit with a familiar smell: old books, polished wood, maybe a hint of institutional air conditioning. It's neutral. Safe. Completely disconnected from the artifacts you're looking at.

But what if you could actually smell ancient Egypt?

That's what's happening right now at two major European museums. They're incorporating historically accurate scents into their Egyptian exhibits, and the results are stunning. Visitors aren't just reading about mummification on a placard anymore. They're experiencing it.

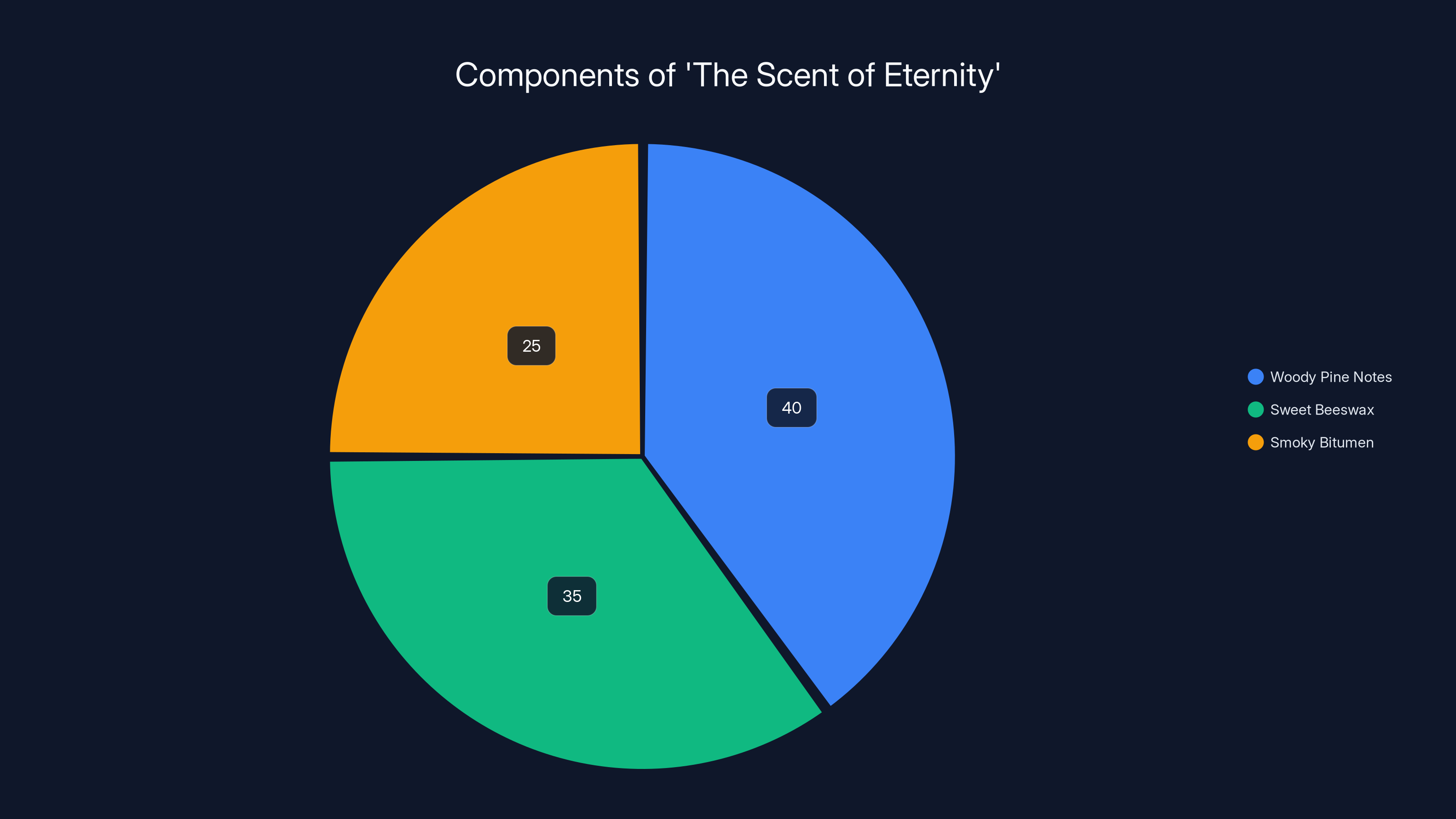

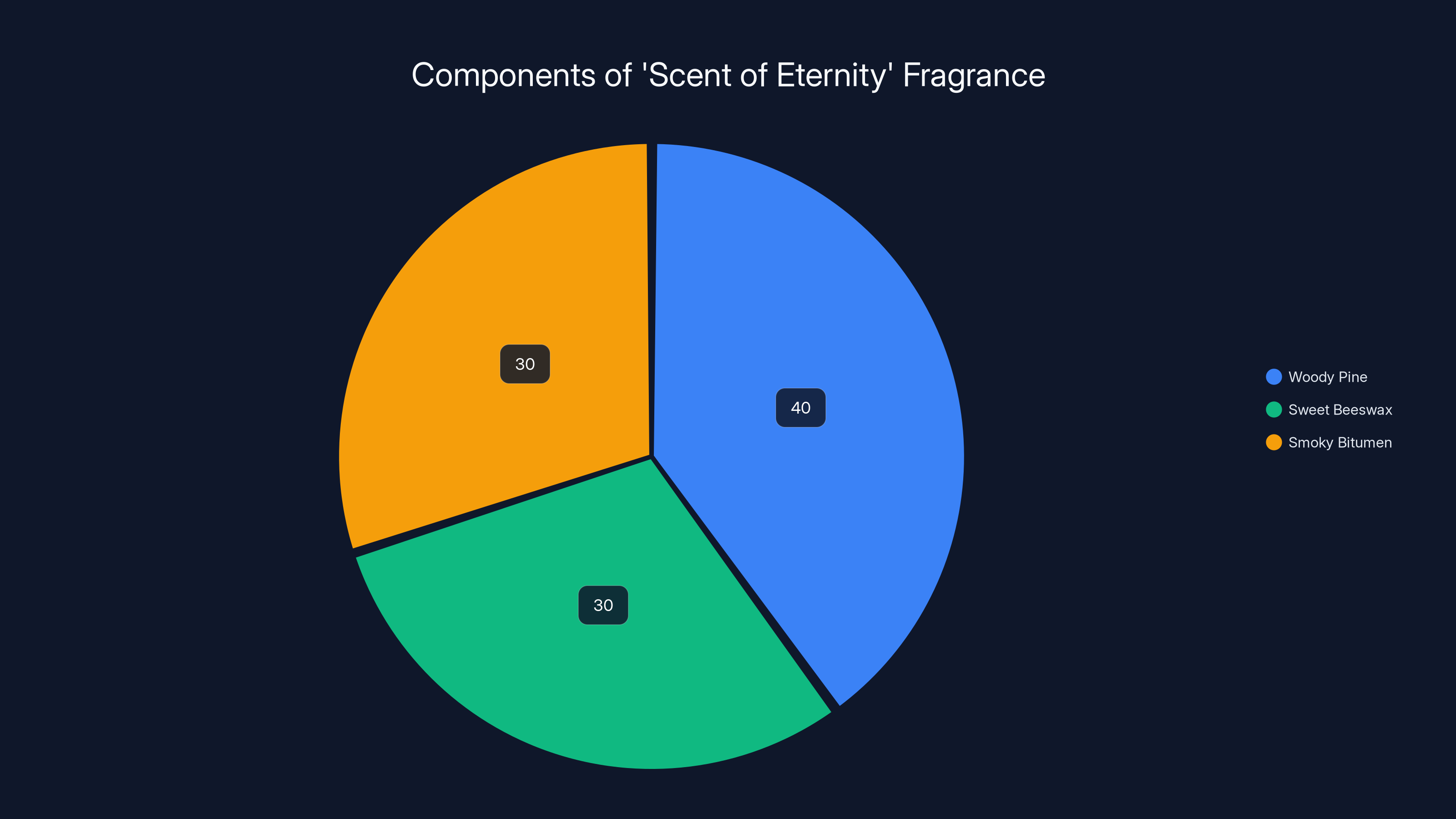

This isn't some gimmick or atmospheric flourish. It's grounded in serious science. In 2023, researchers analyzed the chemical composition of balms used to preserve organs during mummification, identifying complex recipes that included ingredients from across the Mediterranean and beyond. These scientists then partnered with professional perfumers to recreate what they're calling "the scent of eternity." The fragrance combines woody pine notes, sweet beeswax undertones, and smoky bitumen scents that would have filled tombs thousands of years ago.

The impact has been dramatic. Museum curators report that smell fundamentally changed how visitors connected with the artifacts. Instead of viewing mummification as a distant historical practice, people suddenly understood it emotionally. The scent transformed abstract knowledge into visceral memory.

This convergence of archaeology, chemistry, and museum curation represents something broader happening across the cultural world. Museums are increasingly recognizing that we don't understand the past through sight alone. We need multiple sensory entry points. We need to feel it, hear it, and yes, smell it.

Let's explore how this ancient science got reconstructed, why smell matters so much for human memory and emotion, and what it means for the future of museum experiences.

TL; DR

- Ancient Egyptian mummification involved complex chemical recipes combining plant oils, resins, bitumen, and aromatic compounds that scientists have now identified using advanced analysis techniques

- Researchers recreated "the scent of eternity" through biomolecular analysis and professional perfumery, combining woody pine, sweet beeswax, and smoky notes

- Museums deploying these scents report transformed visitor experiences, with smell adding emotional depth that traditional labels cannot match

- Scent engages memory and emotion more powerfully than visual information, creating longer-lasting impressions and deeper understanding of historical practices

- This approach represents a shift in museum strategy toward multisensory experiences that honor the full context of artifacts and cultural practices

The 'Scent of Eternity' is primarily composed of woody pine notes, complemented by sweet beeswax and smoky bitumen, reflecting the materials used in ancient Egyptian embalming. Estimated data.

Understanding Ancient Egyptian Mummification

Mummification wasn't invented in a laboratory or mandated by a pharaoh's decree. It emerged gradually from observation and necessity.

Egyptians noticed something simple but profound: the desert preserves. When bodies were buried in sand in the Predynastic Period (around 6000 BCE or earlier), the arid heat naturally desiccated them. The dry climate acted as a natural preservative, preventing decay. Families saw their deceased relatives' bodies remain intact, and something shifted in Egyptian religious thinking. The preservation of the physical body became essential to the afterlife.

But as Egyptian civilization developed, burial practices changed. People moved from simple desert graves to elaborate rock tombs, sealed away from the desiccating sand. Without the natural preservation provided by desert heat, the bodies would decay. Egyptians needed to create their own preservation system.

This is where the chemistry comes in.

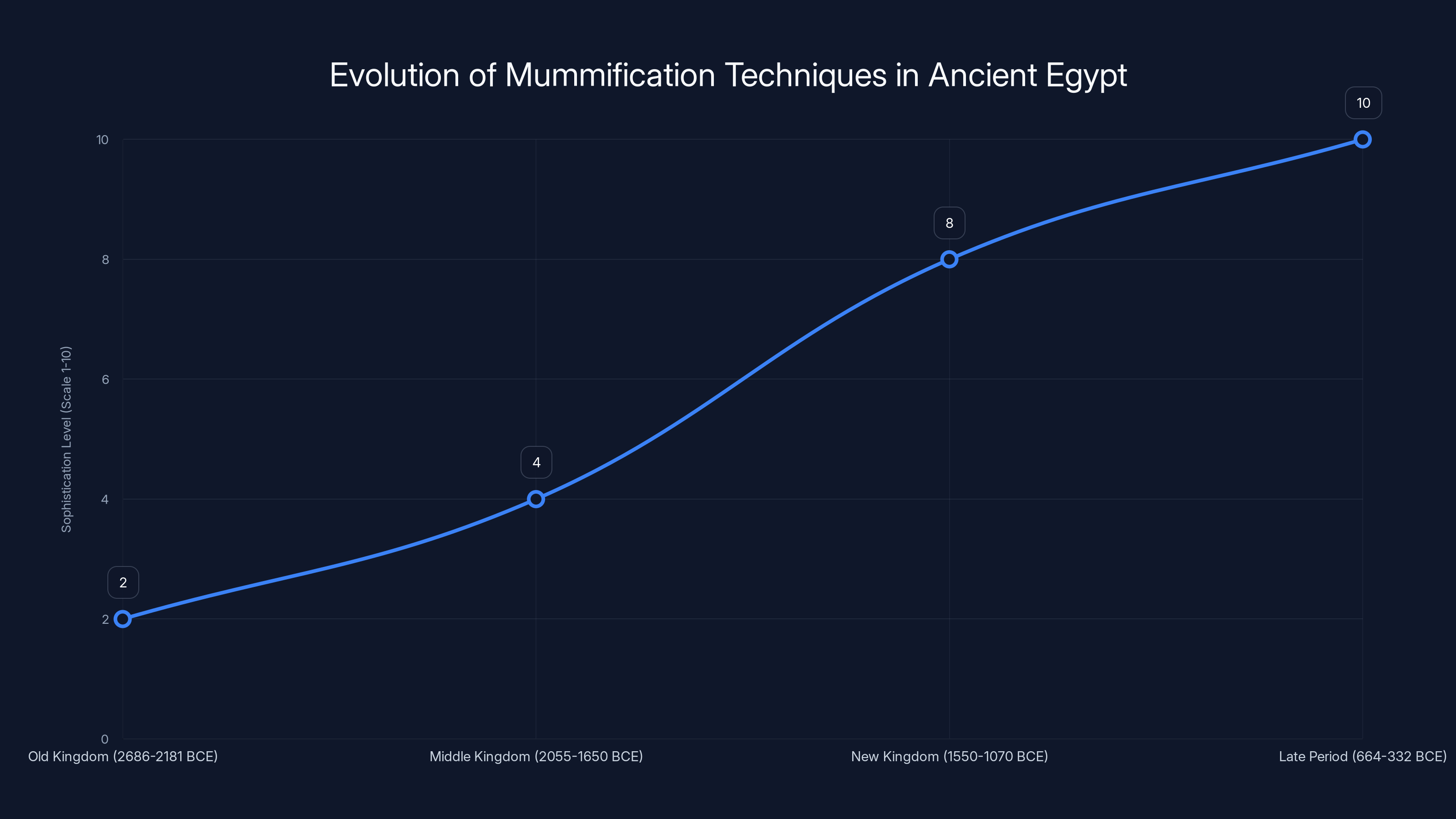

The mummification process became ritualized and refined over roughly 3,000 years, evolving from crude techniques in the Old Kingdom (around 2686-2181 BCE) to sophisticated procedures by the New Kingdom (around 1550-1070 BCE). But the core logic remained consistent: remove what decays, dry what remains, seal it against moisture and air, and protect it with resins and wrappings.

The first step was always the most invasive. The body was laid on a table, and the internal organs were removed. The embalmers used metal hooks to extract the brain through the nostrils, then liquefied the remaining brain tissue with drugs injected through the opening. This might sound horrifying to modern sensibilities, but it made practical sense. The brain has high water content and would decompose quickly. Removing it prevented decay from spreading.

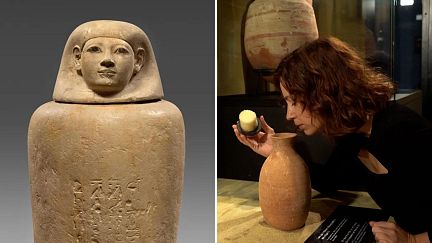

Next came the organs. The liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines were extracted through an incision in the left side of the abdomen. These were the organs most prone to rapid decay. They were cleaned, treated with natron salt and spices, and placed in canopic jars—specially designed ceramic containers that would hold them for eternity. Interestingly, the heart was left inside the body. Egyptians believed the heart was the seat of intelligence and emotion, essential for the afterlife. Removing it would be like removing the person's consciousness.

The body cavity was then washed with spices and palm wine. Palm wine had antimicrobial properties and pleasant smell. The choice wasn't random. These spices and wines served both practical and spiritual purposes.

Then came the waiting. The body was covered in natron salt—a naturally occurring mineral found in Egypt's desert regions. Natron is sodium carbonate mixed with sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulfate. It's hygroscopic, meaning it actively draws moisture from organic material. For forty days, the natron pulled water from the corpse, desiccating it completely. The body lost about 75% of its water weight during this period.

After forty days, the natron was removed, and the body was wrapped in multiple layers of linen cloth. But this wasn't simple cloth. Between the layers, embalmers placed amulets, protective charms, and dried flowers. The wrappings were saturated with resins and plant oils. These served multiple purposes: they waterproofed the mummy, provided antimicrobial protection, and created a fragrant barrier against decay.

Finally, the entire mummy was coated in more resin and placed in a coffin, which was also sealed with resin. Multiple layers of protection. The goal was to create an environment where microbial life couldn't survive and moisture couldn't penetrate.

For nearly 4,000 years, this worked. Bodies buried in sealed tombs remained largely intact, preserved not by any single ingredient but by the entire system working together.

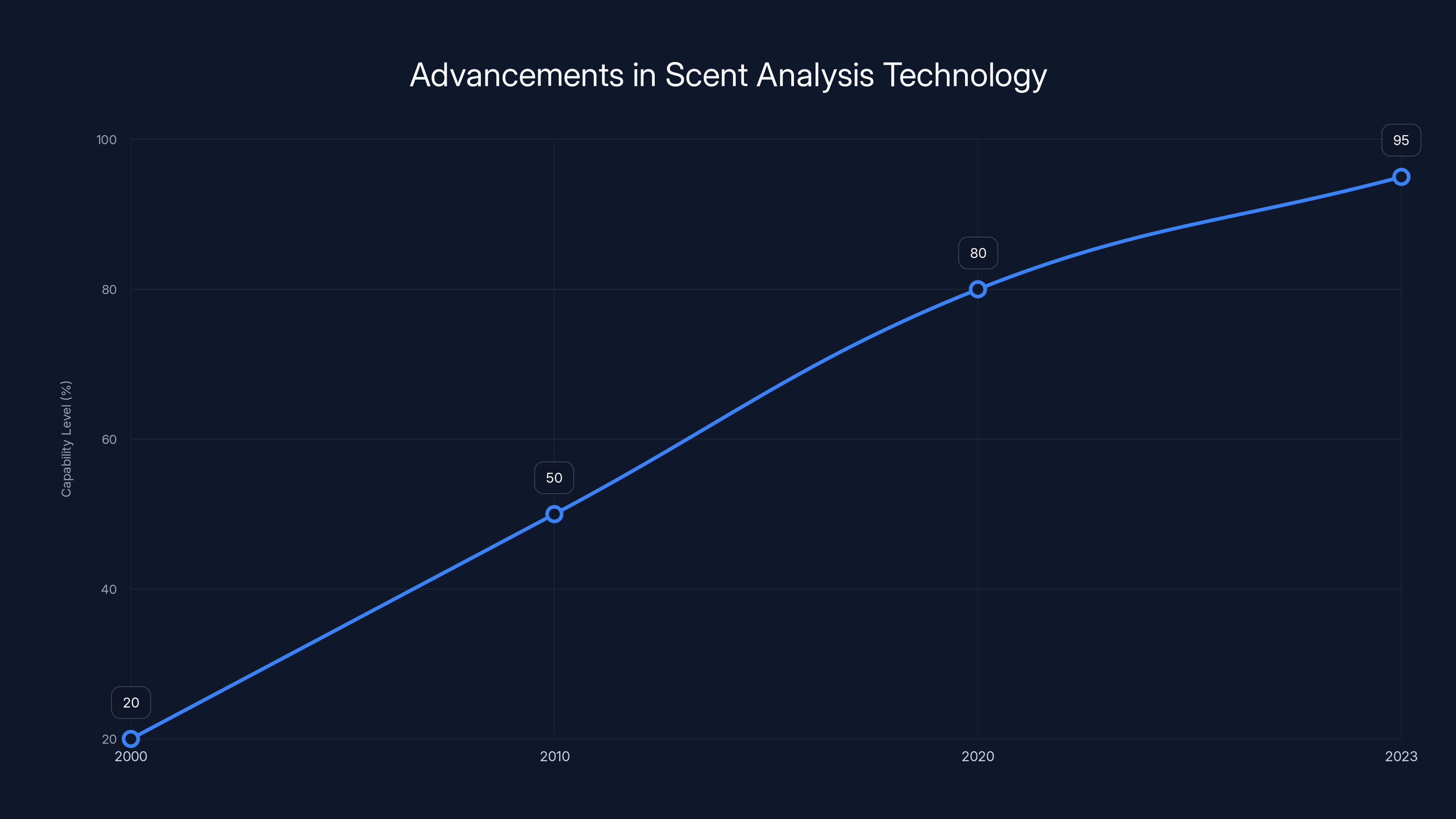

Estimated data shows significant advancements in scent analysis technology over the past two decades, with capabilities nearing full potential by 2023.

The Chemistry Behind Ancient Preservation

For centuries, our understanding of mummification came from a handful of sources. The Ritual of Embalming, an ancient Egyptian document, provided some instructions. The Greek historian Herodotus described what he observed, including the use of natron to dehydrate bodies. But these texts lacked crucial detail. Which specific spices were used? What proportions? Where did rare ingredients come from? What did the balms actually contain?

Science couldn't answer these questions with speculation. It needed physical evidence.

That's where biomolecular analysis comes in. Starting in the late 20th century, scientists began analyzing residues on mummy wrappings, inside canopic jars, and on the bodies themselves. They used techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), which separates chemical compounds and identifies them precisely.

In 2018, researchers analyzing organic residues from mummy wrappings found something fascinating. The wrappings were saturated with a specific mixture: plant oil, aromatic plant extract, gum or sugar, and heated conifer resin. This wasn't a simple single substance. It was a deliberate formulation, balanced for specific properties.

But the real breakthrough came more recently when researchers focused not on the wrappings but on the balms used in canopic jars. These containers held the organs—the most important items requiring preservation. If embalmers were going to use their finest formulations anywhere, it would be here.

When scientists analyzed the residues from these balms, they found a sophisticated mixture. Let's break down what they discovered:

Beeswax: A natural preservative with antimicrobial properties. It's hydrophobic, meaning it repels water. Beeswax also has a sweet, slightly honey-like smell that would have been pleasant in the tomb.

Plant oils: Primarily from seeds and nuts. These provided moisture-resistant properties and prevented wooden containers from drying and cracking. They also contributed aromatic compounds.

Animal fats: Possibly from cattle or birds. These added waterproofing and created a protective barrier around the organs.

Bitumen: A naturally occurring tar-like substance found in the Dead Sea region. This was exotic, expensive, and traveled great distances to reach Egypt. Bitumen has strong antimicrobial properties and creates an almost waterproof seal. It also has a distinctive, powerful smoky scent.

Coniferous tree resins: From pines, larches, and similar trees. These don't grow in Egypt. They came from the Levant or further north, traveling along ancient trade routes. Coniferous resins have multiple benefits: strong antimicrobial properties, waterproofing, pleasant woody fragrance, and they harden over time, creating a protective shell.

Aromatic compounds: Including vanilla-scented coumarin found in cinnamon and pea plants, and benzoic acid from fragrant resins and gums derived from trees and shrubs.

What surprised researchers was how non-local this recipe was. Egypt produced natron, linen, and some plant oils. But beeswax came from apiculture. Bitumen came from the Dead Sea. Coniferous resins came from Mediterranean forests. Cinnamon came from even farther away—possibly India or Sri Lanka via long-distance trade routes.

This wasn't a recipe someone developed locally. It was the result of intentional sourcing from across the known world. The Egyptians, or at least the wealthy nobility, had access to the best preservative ingredients available. They were willing to pay for them and incorporate them into their mummification process.

The proportions also matter. These weren't random ingredients thrown together. The ratios were deliberate. More bitumen creates stronger antimicrobial protection but a smokier scent. More coniferous resin provides better waterproofing but a woodier smell. The balance suggests these formulations were refined over generations, tested and adjusted for optimal preservation and, yes, pleasant aroma.

The implications are significant. Mummification wasn't just a religious ritual. It was applied chemistry, informed by empirical observation about what works best for long-term preservation. The ancient Egyptians understood preservation at a chemical level, even if they couldn't articulate it using modern chemical nomenclature.

The Science of Reconstructing Ancient Scents

Once researchers identified the chemical composition of ancient balms, a new question emerged: could these scents be recreated? And more importantly, should they be?

The challenge is more complex than simply combining ingredients. When you heat bitumen, the volatile organic compounds change. When plant oils oxidize over centuries, they transform. The scent that filled a tomb 3,000 years ago isn't the same as the scent of the raw materials today.

This is where biomolecular analysis becomes forensic work. Scientists identified the volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—the specific molecules that carry smell—in the residues. They distinguished between compounds that came from the original embalming ingredients and compounds that arose from chemical degradation over time. Some of those degradation products would have been present in the original scent; others were artifacts of aging.

The research team conducted a sophisticated analysis. They sampled balms and mummy tissues broadly, not just from one mummy but from multiple sources. This allowed them to see patterns. Which scents appeared consistently across different mummies? Which varied based on regional practices or time periods? Which were likely from degradation rather than original ingredients?

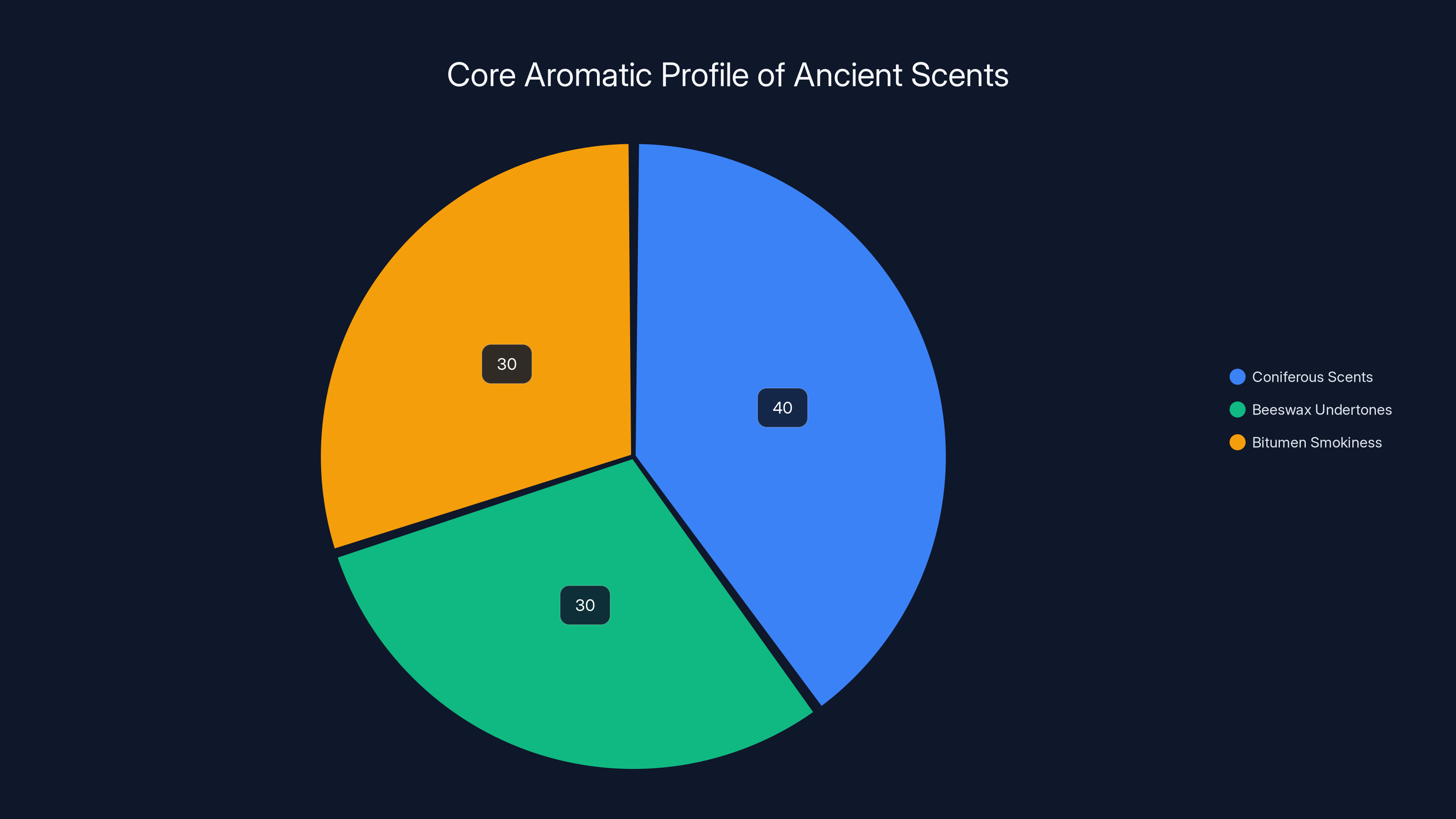

They identified the core aromatic profile: the strong, woody, pine-like scent of the conifers, mixed with the sweeter, warmer undertones of beeswax, and the heavy, smoky scent of bitumen. This combination would have been present from the moment the balms were applied.

But recreating scent is an art, not just a science. Chemical data tells you what molecules are present, but it doesn't tell you how the human nose perceives them in combination. That's where perfumery comes in.

The research team collaborated with Carole Calvez, a professional perfumer with expertise in historical fragrance reconstruction. Calvez faced a genuinely difficult creative challenge. She had the chemical data. She knew the approximate percentages of each component. But she also knew that translation matters.

"The real challenge lies in imagining the scent as a whole," Calvez explained. "Biomolecular data provide essential clues, but the perfumer must translate chemical information into a complete and coherent olfactory experience that evokes the complexity of the original material, rather than just its individual components."

This is crucial. If you simply combined the raw materials in the exact proportions they found, you wouldn't get the original scent. Some compounds are odorless or nearly odorless; they serve preservation functions but contribute little to smell. Other compounds need adjustment because modern bitumen or modern resins might smell different from ancient versions. The perfumer needs to think holistically about the olfactory experience.

Calvez created a formulation that captured the essence of the original scent while being suitable for museum environments. It needed to be stable—not changing over days or weeks. It needed to be safe—not allergenic or irritating. And it needed to be evocative without being overwhelming.

The resulting fragrance is complex. It doesn't smell like a single ingredient. It's a layered experience. When you first encounter it, the bright, woody pine notes hit first—clean and slightly sharp. Then, as the scent develops on your skin or in the air, the sweeter beeswax notes emerge. Finally, the deeper, more mysterious bitumen base note comes through, adding earthiness and smoke.

It's genuinely unusual. Most modern fragrances aim for harmony and balance. This scent is intentionally complex and somewhat challenging. It's supposed to smell ancient, unfamiliar, powerful. And that's exactly what makes it effective in a museum context.

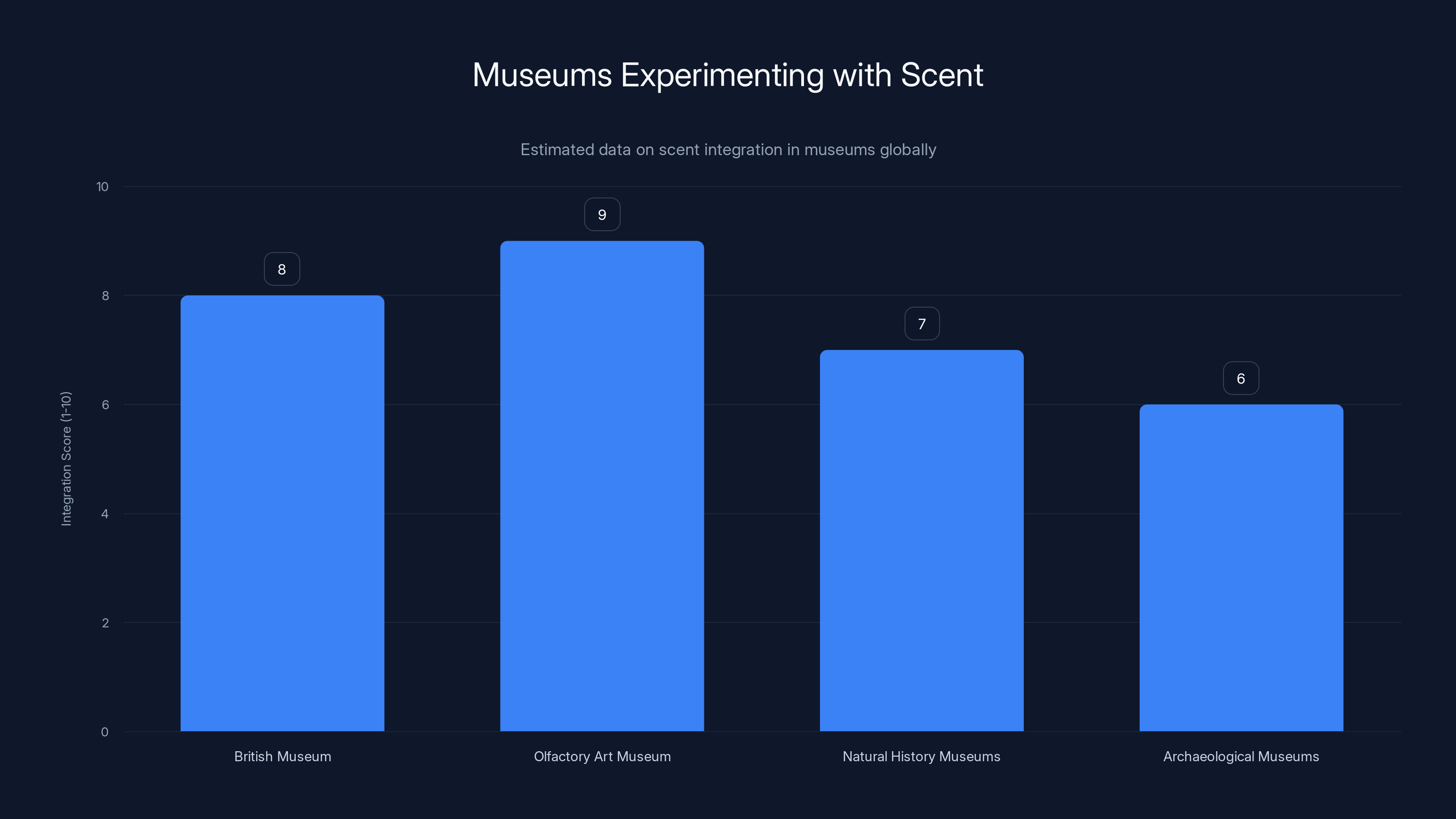

Estimated data suggests that museums like the Olfactory Art Museum and the British Museum lead in scent integration, with high scores for thoughtful and historically grounded implementation.

How Museums Are Implementing Scent Experiences

Once the scent formulation was perfected, researchers faced a practical challenge: how do you actually incorporate scent into a museum exhibit? It can't be intrusive. It can't interfere with other exhibits. It can't be overwhelming. And it needs to be sustainable—not requiring constant reapplication or creating mess.

The research team, working with museum curators, developed two different approaches, each suited to different museum contexts and audiences.

The Portable Scent Card Approach

The first implementation happened at the Museum August Kestner in Hanover, Germany. The museum chose a low-tech but highly effective approach: scented cards.

These aren't scratch-and-sniff cards, which would be too gimmicky and too temporary. Instead, they're small cardstock cards impregnated with the fragrance formulation. The scent is stable in the material and doesn't degrade quickly.

How does this work in practice? Visitors on guided tours are given the card at the relevant point in the exhibit. The guide explains the historical context: what the balms contained, why these specific ingredients were chosen, how the embalmers would have used them. Then, visitors are invited to hold the card close and experience the scent while looking at the artifacts.

This approach has several advantages. First, it's completely non-invasive. Visitors who don't want to engage with the scent don't have to. They can skip the card or pass it by. Second, it's easily distributed and controlled. The museum staff knows exactly how many people are experiencing the scent at any given time. Third, it's flexible. The cards work with different exhibit designs without requiring structural changes.

But there are limitations. The scent card experience is temporary and personal. Only the person holding the card gets the full effect. Other visitors nearby might catch a whiff, but they won't have the controlled, guided experience. It's also more performative—holding a card while looking at artifacts is a distinct gesture that breaks the flow of museum visiting.

The Fixed Scent Station Approach

The second implementation occurred at the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. This museum took a bolder approach: a dedicated scent station.

The station is positioned near artifacts related to mummification and burial practices. It's essentially a small architectural element—think of it as a sculptural form with a functional purpose. The scent is dispensed gently and continuously, creating an immersive zone.

Visitors walking through the exhibit naturally encounter the scent. They don't have to pick up a card or perform any action. The fragrance is simply present in the environment, creating an atmospheric layer to the exhibit.

This approach is more immersive. The scent becomes part of the spatial experience, not a separate element you choose to engage with. As museum curator Steffen Terp Laursen noted, "The scent station transformed how visitors understood embalming. Smell added an emotional and sensory depth that text labels alone could never provide."

But the fixed station approach requires more planning. The scent needs to be dispensed at the right intensity—strong enough to be noticed but not so strong that it overwhelms other exhibits. The technology needs to be reliable and discreet. And the museum needs to be thoughtful about how the scent zone interacts with traffic patterns and visitor flow.

Both approaches have merit. The portable cards work well for guided tours and for museums with limited space or multiple competing exhibits. The fixed stations work better for creating an immersive zone and for museums with the space and resources to dedicate to scent integration.

Interestingly, there's no "correct" approach. Different museums are choosing different methods based on their specific contexts, budgets, and curatorial goals. What matters is that both approaches are grounded in rigorous science and designed with visitor experience in mind.

Why Scent Matters for Memory and Emotion

Maybe you've experienced this: you catch a whiff of something—a perfume, a food, a particular plant—and suddenly you're transported to a specific moment from years ago. The memory is vivid and emotional, not just intellectual. You don't just remember what happened; you feel it again.

This isn't random. It's neuroscience.

The olfactory system is directly connected to the limbic system, the part of your brain that processes emotion and memory. When you smell something, the signal travels from the olfactory receptors in your nose directly to the piriform cortex and amygdala. There's no intermediate filtering. The signal doesn't go through the thalamus first, like visual or auditory information does. Smell bypasses the logical processing centers and goes straight to the emotional centers.

This means smell engages emotion in a way that sight doesn't. You can look at an artifact and process it intellectually. You can read a label and understand the facts. But when you smell something, you feel it.

Research in cognitive psychology has demonstrated this repeatedly. Scent-based memories are more emotionally intense than memories formed through other senses. They're also more resistant to forgetting. In one study, participants were shown images and told stories. Some participants experienced related scents; others didn't. Weeks later, participants who had experienced scents remembered not just the images but the emotional context more vividly than those who hadn't.

This phenomenon is called olfactory-mediated encoding. The scent serves as a powerful memory hook, binding the experience to emotion and making it more memorable.

For museums, the implications are profound. A museum exhibit is fundamentally about communicating information and fostering understanding. But museums also serve an emotional function. They help us feel connected to human history, to our ancestors, to the continuity of human experience across time.

When a visitor smells the actual fragrance that an ancient Egyptian noble smelled 3,000 years ago, something shifts in their understanding. Mummification stops being a historical practice described in academic language. It becomes something personal. The visitor is momentarily occupying the same sensory space as the ancient people they're learning about. The temporal distance collapses.

This is particularly powerful in the context of mummification, which deals directly with death and the afterlife. These are profound human concerns. Mummification was driven by intense emotion—love for the deceased, fear of death, hope for the afterlife. Engaging visitors' emotions through scent helps them understand not just the mechanics of mummification but its meaning to the people who practiced it.

The sophistication of mummification techniques evolved significantly over time, reaching its peak during the New Kingdom. Estimated data based on historical analysis.

The Broader Trend Toward Multisensory Museum Experiences

Scent-enhanced Egyptian exhibits aren't isolated experiments. They're part of a larger movement in museum curation toward multisensory experiences.

For most of the 20th century, museums were primarily visual spaces. You looked at artifacts behind glass. You read labels. You might listen to an audio guide. But you didn't touch anything. You certainly didn't taste or smell anything. The sensory experience was deliberately limited, focused entirely on sight and the intellectual processing that comes from reading.

This approach made sense for artifact preservation. Objects can't be touched or tasted without damage. But it also limited how deeply visitors could engage with the material.

Over the past couple of decades, museums have been experimenting with expanding beyond visual experience. Some museums have added soundscapes—audio recordings that recreate the auditory environment of the historical period being displayed. Visitors experiencing medieval manuscripts might hear Gregorian chanting. A Vietnam War exhibit might include actual sounds from the period.

Other museums have experimented with tactile experiences, letting visitors handle replica objects or materials relevant to the exhibit. Touch matters. It creates a different kind of understanding. When you hold a Roman clay pot, you understand its weight, its balance, how it was meant to be used. That understanding is different from what you get from looking at it behind glass.

More recently, museums have begun exploring taste, though this is less common and more fraught with practical challenges. A few museums have offered historical food experiences—tasting foods that would have been eaten during the period being exhibited. It's risky (food allergies, sanitation) but powerful when done thoughtfully.

Scent fits naturally into this expansion. It's more practical than taste (fewer allergens, easier to dispense). It's more intimate than sound. It has unique emotional power. And critically, it's underutilized. Most museums don't incorporate scent. Those that do stand out.

The movement reflects a changing understanding of how people learn and engage with historical material. Museums are recognizing that visitors aren't just intellects absorbing information. They're embodied beings with all five senses. When you engage multiple senses, learning becomes deeper, more memorable, and more emotionally resonant.

This is particularly important for younger visitors. Children learn through sensory exploration. Adding scent to exhibits makes them more accessible and engaging for kids. Parents report that their children remember scent-enhanced exhibits far better than they remember typical exhibits. The scent serves as a memory marker.

But it's also valuable for adult visitors. In an increasingly digital world, physical museum experiences matter. When you encounter an artifact in person and engage multiple senses, you're having an experience that a website or video can't replicate. Museums are leaning into that advantage.

Challenges in Scent-Enhanced Museum Curation

Despite the clear benefits, scent integration presents genuine practical challenges that museums have to navigate carefully.

Olfactory Adaptation

One of the biggest challenges is olfactory adaptation. Your nose gets used to a smell. If you're exposed to the same scent for more than about 15 minutes, your olfactory receptors adapt. The smell seems to fade away. This is a neurological adaptation, not a physical one. The scent is still there, but your brain stops processing it as a novel stimulus.

For museums, this is a real problem. A visitor might experience the scent station at the beginning of their visit, but if they linger in that area for a while, the scent adaptation kicks in. Newer visitors entering the space will get the full experience, but long-term visitors won't.

Museums address this in a few ways. Some vary the intensity of the scent based on time of day. Busier times get lighter scent dispersal, while quieter times get stronger release. The idea is to ensure that the broadest range of visitors gets an optimal experience.

Others use scent stations that are positioned to require movement. Visitors pass through the scent zone, experience it, then move on. They don't sit and linger. This natural flow prevents adaptation from becoming an issue.

The portable card approach solves this partially. Visitors hold the card when instructed and then put it away. The interrupted exposure prevents adaptation. But it also creates a less immersive experience.

Allergies and Sensitivities

Another challenge is individual variation in scent perception and reaction. People have different sensitivities to fragrant compounds. Some people have fragrance allergies. Others have migraine triggers related to strong scents. Some people simply dislike certain smells.

Museums using scent have to be thoughtful about this. They need to provide clear warnings so that people with sensitivities can avoid the scent zone. They need to make engagement optional, not mandatory. And they need to choose scents that are unlikely to trigger common reactions.

The historical "scent of eternity" formulation is actually well-chosen for this. Bitumen is powerful but not typically allergenic. Coniferous resin scents are generally well-tolerated. Beeswax has a gentle, warm quality. The formulation was deliberately designed to be complex and interesting without being aggressive or potentially problematic.

But museums still need to test extensively before implementation. Different visitor populations might react differently. Age, health status, cultural background, and individual variation all matter.

Interference with Other Exhibits

Unless carefully designed, a strong scent in one area of a museum can drift to adjacent spaces and interfere with other exhibits. Imagine a delicate textile exhibit right next to a scent-enhanced Egyptian exhibit. The fragrance could overwhelm visitors of the textile exhibit and make their experience worse, not better.

This is why fixed scent stations need to be designed with ventilation in mind. They're often positioned in alcoves or with careful air flow management to keep the scent localized. The intensity also matters. The goal is presence, not overwhelming olfactory dominance.

Some museums solve this by using scent only during specific times or for specific tours, then turning it off for other times. This prevents interference and manages the experience more carefully.

Cost and Sustainability

Implementing a scent program requires ongoing investment. The fragrance formulation needs to be made by a professional perfumer, which costs money. Scent cards need to be produced in sufficient quantity. Fixed scent stations require equipment that dispenses fragrance reliably and in appropriate doses. Staff need training on how to explain the scent program to visitors.

Then there's the question of sustainability. How long does a scent formulation remain stable? How often does it need to be refreshed? For portable cards, the scent can last months or even years. For fixed stations, it might need more frequent replenishment.

Museums are generally well-funded institutions, but they still operate with constraints. A scent program that requires expensive equipment or frequent expensive refreshing might not be feasible for smaller museums or those with limited budgets.

Some museums are developing more cost-effective approaches. DIY scent dispensers using simple materials. Partnerships with fragrance companies to subsidize costs. Rotating scent programs that aren't permanent installations.

The economics are improving as more museums adopt these programs and share best practices about cost-effective implementation.

Cultural Sensitivity

One more subtle but important consideration is cultural sensitivity. Scent is culturally significant. Fragrance preferences vary across cultures. A scent that feels authentic and evocative to visitors from one cultural background might feel wrong or artificial to visitors from another.

For ancient Egyptian mummification, this is less fraught than it might be for exhibits dealing with contemporary cultural practices. But it still matters. The researchers worked carefully to ground the scent in historical evidence, not modern assumptions about what ancient Egypt "should" smell like.

More broadly, museums using scent need to think about whether the scent represents the culture accurately. Is it historically grounded? Was it developed with input from cultural experts? Does it risk exoticizing or essentializing the culture in question?

These are genuinely important questions, and thoughtful museums take them seriously.

The 'Scent of Eternity' fragrance used in museum exhibits is composed of woody pine (40%), sweet beeswax (30%), and smoky bitumen (30%), enhancing visitor connection with ancient Egyptian artifacts. Estimated data.

The Research Behind Modern Scent Analysis

The technology that makes scent reconstruction possible didn't exist a few decades ago. Understanding how researchers can identify and recreate ancient scents requires understanding the analytical methods they use.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, or GC-MS, is one of the primary tools. Here's how it works: a sample is heated so that its chemical compounds volatilize (turn into gas). These gases are then passed through a long, thin column filled with a special material that separates different compounds based on how they interact with the column material. Lighter compounds move through faster; heavier ones move through slower. This separates the complex mixture into individual components.

At the end of the column, a mass spectrometer analyzes each individual compound. The spectrometer measures the mass and molecular structure of each compound, creating a unique signature for identification. By comparing these signatures to known databases of chemical compounds, researchers can identify what's present in the sample.

The process is elegant and powerful. A tiny sample of an ancient mummy's wrapping or the residue from a canopic jar can be analyzed to reveal its complete chemical composition.

But the analysis doesn't stop there. Researchers also need to understand which compounds are likely to be odorous—carrying smell—and which are not. They use instruments called olfactometers that can detect and measure very small concentrations of volatile organic compounds. They combine this chemical data with sensory evaluation. Trained olfactory specialists smell the samples and describe what they perceive.

The goal is to build a comprehensive picture: what compounds are present, which are odorous, and what scent profile they create together.

This level of analytical sophistication is relatively new. Twenty years ago, museums couldn't do this. Ten years ago, it was still very expensive and technically challenging. Now it's becoming more accessible, which is why we're seeing more museums incorporating historical scents into their exhibits.

As the technology improves and costs decrease, we can expect to see more sophisticated and specific scent reconstructions. Future museums might recreate the scent of a Roman marketplace, or a medieval kitchen, or a Victorian perfumery. Each would be grounded in actual chemical analysis of historical materials.

Other Museums Experimenting with Scent

The Egyptian mummification scents at Museum August Kestner and Moesgaard Museum aren't the only museum scent projects underway. Across Europe and increasingly globally, museums are experimenting with how to integrate scent into exhibits.

The British Museum in London has experimented with scent in various exhibits, including recreation of historical fragrances and their role in trade and culture.

The Olfactory Art Museum in Barcelona is dedicated entirely to olfactory experiences, exploring smell across art, history, and science. While not a traditional museum, it demonstrates growing interest in scent as a curatorial medium.

Some natural history museums have added scent to exhibits about plants and medicinal history. Visitors can smell the herbs and spices that were used historically, helping them understand trade networks and medicinal practices.

Archaeological museums in the Mediterranean region have started incorporating scents related to specific excavations or time periods they focus on.

The approaches vary widely. Some museums use scent cards like Kestner. Others use diffusers or scent stations like Moesgaard. Some conduct extensive research before implementing anything. Others use more intuitive approaches based on what seems historically plausible.

Not all experiments work equally well. Some museums find that scent integration feels gimmicky if not done with care and scientific grounding. Others find that visitors love the multisensory experience. The emerging consensus seems to be that scent works best when it's:

- Historically and scientifically grounded

- Optional, not mandatory

- Integrated thoughtfully into the exhibit design

- Clearly explained so visitors understand the reasoning

- Tested extensively before full implementation

Museums that follow these principles report significant positive visitor responses. Those that treat scent as a gimmick without proper grounding often see more mixed results.

Estimated data shows that ancient scents were primarily composed of coniferous scents (40%), beeswax undertones (30%), and bitumen smokiness (30%).

The Neuroscience of Smell and Memory

To understand why scent-enhanced exhibits are so effective, it helps to understand the neuroscience of olfaction and how smell connects to memory and emotion.

Your sense of smell works differently from your other senses. When you see something, light enters your eye, strikes the retina, and triggers signals that travel through several processing stages before reaching the visual cortex in the back of your brain. When you hear something, sound waves trigger hair cells in your inner ear, and those signals travel through multiple relay stations before reaching the auditory cortex.

Smell is different. Volatile organic compounds enter your nasal cavity, dissolve in the mucus layer covering your olfactory epithelium, and bind to olfactory receptors on specialized neurons. These neurons send signals directly to the olfactory bulb, which then sends signals directly to the piriform cortex and amygdala, regions involved in emotion and memory.

This direct connection to the emotional centers of the brain is why smell is so powerfully linked to emotion and memory. There's less processing, less filtering, less time for logical analysis. The scent signal goes straight to the emotional system.

This is also why smell-based memories are different from memories formed through other senses. A visual memory might be more detailed or clear, but a smell-based memory is more emotionally intense and more resistant to forgetting. If you experienced a scent during an important or emotional event, that scent will trigger vivid memory of that event years or even decades later.

For museum visitors experiencing a scent that connects them to an ancient practice, this has profound implications. The scent creates an emotional connection across thousands of years. The visitor isn't just learning about mummification as a historical fact. They're imaginatively experiencing it. The scent shortcuts the analytical part of their brain and goes straight to the emotional, embodied part.

This is why museum curators have found that scent-enhanced exhibits create more memorable, more moving experiences for visitors. The emotional engagement is deeper. The memory trace is stronger.

Research in cognitive psychology supports this. When people learn information while experiencing relevant sensory cues, they remember the information better. They also find the learning more meaningful and more emotionally significant.

One study had participants learn historical information about different time periods. Some participants learned the information while experiencing period-appropriate scents. Others learned the same information without scents. When tested a week later, participants who had experienced scents during learning remembered more information and reported greater emotional engagement with the material.

This suggests that scent-enhanced exhibits aren't just pleasant add-ons. They actually improve learning outcomes and deepen understanding.

How Scent Gets Dispersed in Museum Spaces

Implementing a scent-enhanced exhibit requires practical engineering. How do you actually get the scent into the air in a controlled, non-invasive way?

There are several technologies museums use:

Passive scent cards: As used at Museum August Kestner, these cards are impregnated with fragrance and naturally release scent through evaporation. This is the simplest approach, requiring no electricity or equipment. The downside is that the scent intensity depends on temperature and humidity, and it gradually fades over time.

Active diffusers: These use a small pump or heating element to actively disperse scent into the air. They can be programmed to release scent on a schedule, ensuring consistent intensity. They're more reliable than passive cards but require electricity and more maintenance.

Scent injection into HVAC: Some museums inject scent directly into their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. This distributes scent throughout a space very evenly. The downside is that it's permanent and affects all visitors, not just those at the exhibit.

Scent stations with directional nozzles: As used at Moesgaard Museum, these create a localized scent zone. Scent is released through small nozzles positioned to direct the fragrance toward visitors without affecting surrounding areas. This requires careful ventilation design.

Microencapsulated fragrances: Some museums use microencapsules of fragrance embedded in materials or on cards. The capsules break open when handled or rubbed, releasing scent on demand. This gives visitors active control over the experience.

Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. Passive cards are cheapest and simplest but least controlled. Active diffusers and scent stations are more expensive but offer better control. HVAC integration is most thorough but least flexible.

Museums choose based on their specific needs, budgets, and the type of exhibit. For guided tours with portable cards, passive cards work fine. For permanent installations, active systems make sense.

Future Possibilities for Scent in Museums

As technology improves and museums gain experience with scent-enhanced exhibits, what comes next?

Some possibilities on the horizon:

More specific historical scent recreations: As researchers continue analyzing materials from different cultures and time periods, we'll see scent recreations beyond Egyptian mummification. Medieval markets, Renaissance perfumeries, colonial spice trade routes—all are potential subjects for historical scent reconstruction.

Personalized scent experiences: Museums might eventually use technology to customize scent based on visitor preferences or information. Someone interested in culinary history might experience scents related to food. Someone interested in trade might experience scents related to spices.

Scent combined with other technologies: Augmented reality or virtual reality combined with appropriate scents could create deeply immersive historical experiences. Imagine using VR to experience a Roman marketplace while experiencing actual period-appropriate scents.

Temporal scent narratives: Museums might create scent experiences that change over time, telling a story through shifting aromas. The scent of fresh embalming materials might shift to the aged, smoky scent of a sealed tomb.

Accessibility improvements: As museums gain experience, they'll develop better ways to make scent exhibits accessible to people with olfactory impairments or sensitivities.

Cross-institutional scent databases: Museums might develop shared databases of historical scent formulations, allowing other museums to implement similar experiences without conducting independent research.

The technology and curator thinking in this space is still relatively new. As more museums experiment and share results, the field will mature. What works and what doesn't will become clearer. Best practices will emerge.

The fundamental insight—that engaging multiple senses, particularly smell, creates deeper learning and more memorable experiences—is likely to remain central to museum curation going forward.

The Broader Implications for Historical Understanding

Scent-enhanced exhibits might seem like a specific curatorial innovation relevant only to museums. But they actually point to something broader about how we understand and relate to history.

History is often taught through text and images. We read about the past, look at pictures, and form intellectual understanding. But humans experience the world through all five senses. We exist in bodies that taste, smell, touch, hear, and see simultaneously.

When we limit historical engagement to text and images, we're reducing it to a two-dimensional representation. We're engaging only the parts of our brain involved in abstract thinking and visual processing. We're leaving out the emotional, embodied dimensions of experience.

Scent-enhanced exhibits acknowledge something important: the past was sensory. People didn't experience history in a disembodied way. They experienced it through their bodies, through their senses. Mummification wasn't an abstract practice. It was a sensory experience. It smelled a certain way. It sounded a certain way. It felt a certain way to the people doing it and to the people honoring the dead.

When museums can recreate some of those sensory dimensions, they help visitors understand history in a richer, more embodied way. They help collapse the temporal distance. They help visitors imaginatively inhabit a moment from the past.

This has implications beyond museums. It suggests that historical understanding benefits from engaging multiple senses whenever possible. It suggests that the most complete understanding of the past comes from engaging our full selves—our emotions, our bodies, our senses—not just our intellects.

It also suggests something about human nature. We're not disembodied minds floating in an abstract realm. We're embodied beings shaped by sensory experience. Our emotions are tied to our bodies. Our memories are stored not just as abstract information but as sensory and emotional impressions.

Museums that recognize this and adapt their curation accordingly are offering something profound. They're not just transferring information. They're creating experiences that change how we understand ourselves and our relationship to human history.

Challenges and Considerations for Modern Museums

While scent-enhanced exhibits have tremendous potential, museums implementing them face real challenges that go beyond the technical issues already discussed.

Budget constraints: Most museums operate with limited budgets. Research, fragrance development, installation, and ongoing maintenance of scent programs cost money. For many museums, this is a luxury they can't afford, even if they want to.

Expertise requirements: Developing a successful scent exhibit requires expertise in archaeology, chemistry, perfumery, and museum curation. Most museums don't have all these skill sets in-house. Partnerships and collaborations are necessary but can be complex to arrange.

Visitor expectations management: If a museum adds scent to one exhibit, visitors might expect it everywhere. Managing expectations about what scent experiences are available and why they're selective is important.

Documentation and reproducibility: Museums value being able to document their collections and methods. Scent is ephemeral. How do you document a scent for future reference? How do you ensure that a scent formulation can be reproduced if it needs to be refreshed?

Evaluation and impact measurement: Museums are increasingly interested in measuring the impact of their exhibitions. How do you measure whether a scent-enhanced exhibit created better learning outcomes or more memorable experiences? It's possible but requires careful research design.

Insurance and liability: Adding scent to exhibits raises new insurance and liability questions. What if a visitor has an allergic reaction? Who's responsible? Museums need to think through these legal issues.

These challenges aren't insurmountable, but they're real. Museums that successfully implement scent programs tend to be larger institutions with dedicated education and research staff, or smaller museums that partner with universities or research institutions.

What Visitors Are Saying About Scent-Enhanced Exhibits

The best way to understand the impact of scent-enhanced exhibits is to look at actual visitor feedback from museums that have implemented them.

At Museum August Kestner, visitor surveys showed strong positive response. Visitors reported that the scent made the exhibit more memorable. They reported feeling more emotionally connected to the artifacts and to the historical context. Comments like "I felt like I was there" and "This made it real" were common.

Particularly interesting was how families with children responded. Parents reported that their children were significantly more engaged with exhibits that included scent. Kids who might have rushed through an exhibit while reading labels stopped, engaged more carefully, and asked more questions.

At Moesgaard Museum, the feedback was even more enthusiastic. Curator Steffen Terp Laursen reported that visitor time in the scent-enhanced area increased significantly. People lingered longer, spent more time looking at artifacts, and engaged more deeply with the interpretive materials.

Many visitors reported that the scent made them think about mummification in a new way. Instead of seeing it as an abstract historical practice, they understood it as something connected to human emotion and care for the deceased. Parents explained it to children as "a way of saying goodbye, of keeping someone safe forever."

Some visitors reported that the scent was initially surprising or even off-putting—it's not a conventionally pleasant fragrance. But almost all of them reported that once they understood what they were smelling and why, their perception shifted. The "strangeness" became part of the appeal, helping them feel connected to something genuinely ancient and unfamiliar.

Negative feedback was minimal. A small percentage of visitors reported that the scent was too strong or that they didn't like it. But even among those visitors, there was appreciation for the intent and innovation. The museums' clear messaging about the scent and the option to skip it or avoid the area meant that even people who didn't enjoy the scent didn't report feeling bothered by it.

Overall, visitor response has been enthusiastically positive. This bodes well for the future of scent-enhanced exhibits. As more museums see success with these programs, more are likely to implement them.

The Role of Scientific Collaboration in Curatorial Innovation

The scent-enhanced Egyptian exhibits represent a model for how museums can partner with scientists to enhance their curatorial practice.

This didn't happen by accident. It resulted from intentional collaboration. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute conducted the analytical work, identifying the chemical composition of ancient balms. Museums reached out to these researchers, interested in taking their findings and implementing them in a public-facing way. Museum curators, researchers, and perfumers worked together to translate scientific data into museum experience.

This kind of collaboration is increasingly common. More museums are partnering with universities and research institutions. More scientists are interested in public engagement and in seeing their research applied in ways that reach broader audiences.

The benefits go both directions. Museums gain access to cutting-edge research and scientific expertise. Scientists gain access to authentic artifacts and the opportunity to contribute to public understanding of their work. The public gets exhibits that are more rigorous and more thoughtfully designed.

For museums considering similar partnerships, there are lessons here:

-

Start with genuine research questions: The best partnerships begin with museums or scientists asking real questions they want to answer, not with an agenda to create something novel for novelty's sake.

-

Invest in translation: The gap between scientific research and public communication is real. Someone needs to do the work of translating findings into something meaningful to a general audience. Perfumers in this case played that translation role.

-

Test extensively: Before implementing anything publicly, test thoroughly. Gather feedback. Refine. The museums and researchers tested the fragrance formulation extensively before putting it in public exhibits.

-

Document everything: Partnerships are temporary. Relationships change. Jobs change. Document the process thoroughly so that the work can be continued, refined, and applied elsewhere.

-

Plan for sustainability: Think through how the program will be maintained over time. Will staff need training? Will materials need replenishment? What happens if key people leave?

Museums that follow these principles tend to have more successful partnerships and more sustainable programs.

Conclusion: The Future of Multisensory Museum Experiences

Standing in a museum exhibit and experiencing a scent that connects you to a moment 3,000 years in the past is a strange and wonderful thing. It's a reminder that human experience, while separated from us by millennia, isn't entirely foreign. We share embodied experiences. We respond to fragrance. We care for our dead. We try to preserve what matters to us.

Scent-enhanced exhibits aren't just a curatorial gimmick or a novel way to attract visitors. They represent a genuine shift in how museums think about their role. Museums are no longer content to be repositories of information about the past. They're becoming spaces where visitors can imaginatively inhabit the past, engage with it through multiple senses, and understand it more completely.

This shift reflects broader changes in museum philosophy. Visitors increasingly expect museums to engage them actively, not just passively present information. They want experiences, not lectures. They want to understand the human dimensions of history, not just the facts.

Scent is one tool among many for creating these richer experiences. Sound, touch, taste, and spatial design all play roles. But scent is particularly powerful because of its direct connection to emotion and memory. It offers something unique.

As museum professionals gain experience with scent-enhanced exhibits, the technology will improve. Costs will decrease. Best practices will emerge. More museums will adopt these approaches. We'll see scent recreations of historical periods and places we haven't yet imagined.

But beyond the specific applications, the broader lesson is important: understanding the past requires engaging our full selves. Our emotions, our bodies, our senses—all of these are pathways to understanding. History isn't abstract. It was lived. Lived by people who ate and drank and smelled and felt. When museums help us access those sensory dimensions, they help us understand history more deeply and more truly.

The scent of eternity, wafting through museum galleries, is doing more than adding atmosphere. It's bridging time. It's helping us understand that we're connected to people who lived thousands of years ago not just through abstract ideas, but through embodied human experience. And that connection matters.

FAQ

What exactly is "the scent of eternity" mentioned in museums?

"The scent of eternity" is a fragrance formulation developed by perfumer Carole Calvez based on scientific analysis of the balms used in ancient Egyptian mummification. The scent combines woody pine notes from coniferous tree resins, sweet undertones from beeswax, and smoky notes from bitumen, creating an olfactory profile grounded in actual chemical compounds identified in archaeological samples of ancient Egyptian mummification materials.

How did researchers identify what ancient Egyptian embalming actually smelled like?

Researchers used advanced analytical chemistry techniques, particularly gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), to analyze chemical residues from mummy wrappings and the balms stored in canopic jars. These analyses identified specific volatile organic compounds—the molecules that carry smell—that were present in the original embalming materials. They then distinguished between original scent compounds and those that had formed through chemical degradation over millennia, reconstructing what the original fragrance would have been.

Why is smell such a powerful tool for museum exhibits?

Smell has a unique neurological pathway. Olfactory signals travel directly to the limbic system, the brain's emotional and memory centers, without passing through the logical processing filters that visual and auditory information must traverse. This means scent engages emotion and memory more powerfully and directly than other senses. Scent-based memories are also more emotionally intense and more resistant to forgetting than memories formed through other sensory channels.

How do museums actually deliver scent to visitors without overwhelming them?

Museums use different approaches depending on their needs. Portable scent cards, as used at Museum August Kestner in Hanover, let visitors engage with fragrance on demand during guided tours. Fixed scent stations, like at Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, use carefully designed ventilation and directional nozzles to create a localized scent zone. Active diffusers with programmable release mechanisms help control intensity. The key principle is that engagement is optional and carefully managed.

What are the practical challenges of adding scent to museum exhibits?

Museums face several challenges including olfactory adaptation (people's noses get used to a smell after about 15 minutes), individual variation in scent sensitivity and allergic reactions, cost and sustainability of fragrance production and dispersal, preventing scent from interfering with adjacent exhibits, and managing visitor expectations. Solutions include rotating scent intensity, providing clear warnings, positioning exhibits thoughtfully, and testing extensively before public implementation.

Are there other historical scents that museums are trying to recreate?

While the Egyptian mummification scents are the most publicly prominent, museums are experimenting with scent recreations across many historical periods and contexts. Possibilities include medieval marketplace scents, Renaissance perfumery fragrances, scents from colonial spice trade routes, and historical medicinal plant preparations. The field is still relatively new, but as technology improves and costs decrease, we're likely to see more sophisticated and specific scent recreations.

How can visitors with olfactory impairments or fragrance sensitivities still engage with scent-enhanced exhibits?

Responsible museums provide clear information about which exhibits include scent, allowing visitors to plan their experience accordingly. Alternatives might include detailed descriptions of what the scent contains and why it's significant, even for visitors who can't smell it. Some museums develop tactile or visual representations to convey information that might otherwise be communicated through smell. The key principle is accessibility and inclusion, ensuring that no visitor feels excluded by sensory enhancements.

What does the research say about whether scent actually improves learning and memory in museum contexts?

Cognitive psychology research consistently shows that learning information while experiencing related sensory cues improves both memory retention and emotional engagement with the material. Studies of museum visitors experiencing scent-enhanced exhibits report significantly longer engagement with artifacts, more questions asked, and better recall of information weeks later compared to visitors experiencing traditional exhibits without scent. The evidence strongly supports the educational value of multisensory museum experiences.

This article explores how museums are revolutionizing the visitor experience by incorporating historically accurate scents into their exhibits, grounded in cutting-edge archaeological science and cognitive psychology.

Key Takeaways

- Researchers identified the complex chemical composition of ancient Egyptian mummification balms using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, discovering ingredients sourced from across the Mediterranean including coniferous resins, bitumen, beeswax, and aromatic compounds

- Two major European museums now integrate historically accurate scents into Egyptian exhibits using different delivery methods: Museum August Kestner uses portable scent cards for guided tours, while Moesgaard Museum employs a fixed scent station with directional ventilation

- Smell engages the brain's emotional and memory centers more directly than other senses because olfactory signals bypass logical processing and travel straight to the limbic system, creating more emotionally intense and longer-lasting memories

- Visitor feedback from scent-enhanced exhibits shows significantly increased engagement, longer time spent examining artifacts, more questions asked, and better recall of information weeks later compared to traditional exhibits

- The trend toward multisensory museum experiences represents a shift in curatorial philosophy, recognizing that people learn and remember better when engaging multiple senses simultaneously, particularly with emotionally resonant materials like those involving death and afterlife

![How Museums Use Ancient Scents to Transform Egyptian Exhibits [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-museums-use-ancient-scents-to-transform-egyptian-exhibit/image-1-1770269883279.jpg)