Introduction: An Unexpected Discovery in the Details

Sometimes history arrives at your doorstep without warning. In 2010, a space enthusiast purchased what seemed like ordinary promotional items from eBay, bright red tags approximately three inches wide by twelve inches long. They were labeled "Remove Before Flight"—the standard prefix found on thousands of components across NASA's space shuttle program. The listing was unremarkable, marketing them simply as generic examples of KSC Form 4-226, the Kennedy Space Center's official designation for these safety tags. The seller mentioned using them as boat decorations. Nothing suggested these small pieces of fabric and string carried a deeper significance.

But forty years ago, these exact tags were physically attached to something extraordinary. They were fastened to ET-26, the external tank that would carry Space Shuttle Challenger into orbit on January 28, 1986. That morning, at 11:39 AM Eastern Time, Challenger lifted off from Pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center with seven crew members aboard. Seventy-three seconds later, structural failure caused by a compromised O-ring in the right solid rocket booster led to the vehicle breaking apart at 48,000 feet. All seven crew members perished: Commander Dick Scobee, Pilot Michael Smith, Mission Specialists Ronald McNair, Judith Resnik, and Ellison Onizuka, Payload Specialist Gregory Jarvis, and Teacher-in-Space Christa McAuliffe as detailed by Britannica.

The "Remove Before Flight" tags had been removed well before propellant loading, as required by procedure. They were never exposed to the forces that destroyed Challenger. Yet they remain connected to that tragedy by proximity and time—they touched the vehicle that would be lost, marked components that would never complete their mission, and eventually became scattered artifacts of a disaster that reshaped American spaceflight as reported by collectSPACE. The discovery that these seemingly generic items were actually hardware from STS-51L transformed their meaning entirely. What began as curiosity about stamped designations became an investigation into the hidden history of objects that survived when their vehicle did not.

This is the story of how one collector began tracing those tags through decades of institutional memory, storage procedures, and the fog of time that obscures space program artifacts. It's also a broader story about how physical objects connect us to history, how documentation failures affect our ability to preserve memory, and why even small components matter when they carry the weight of collective tragedy.

TL; DR

- The discovery: Collector found eBay-purchased tags stamped ET-26, linking them directly to Challenger's external tank from STS-51L according to Spectrum Local News.

- Confirmation: Cross-referencing NASA flight records and Lockheed Martin documentation confirmed the tags' association with the ill-fated 1986 mission as noted by Britannica.

- The mystery: How these tags were stored, transferred, and eventually sold decades later remains largely undocumented as highlighted by collectSPACE.

- The significance: Only one piece of Challenger is on public display; these tags could provide museums and educators with authentic artifacts to preserve mission memory as reported by the Concord Monitor.

- The challenge: Without complete provenance documentation, museums face accession barriers that prevent proper preservation and display as discussed in Nature.

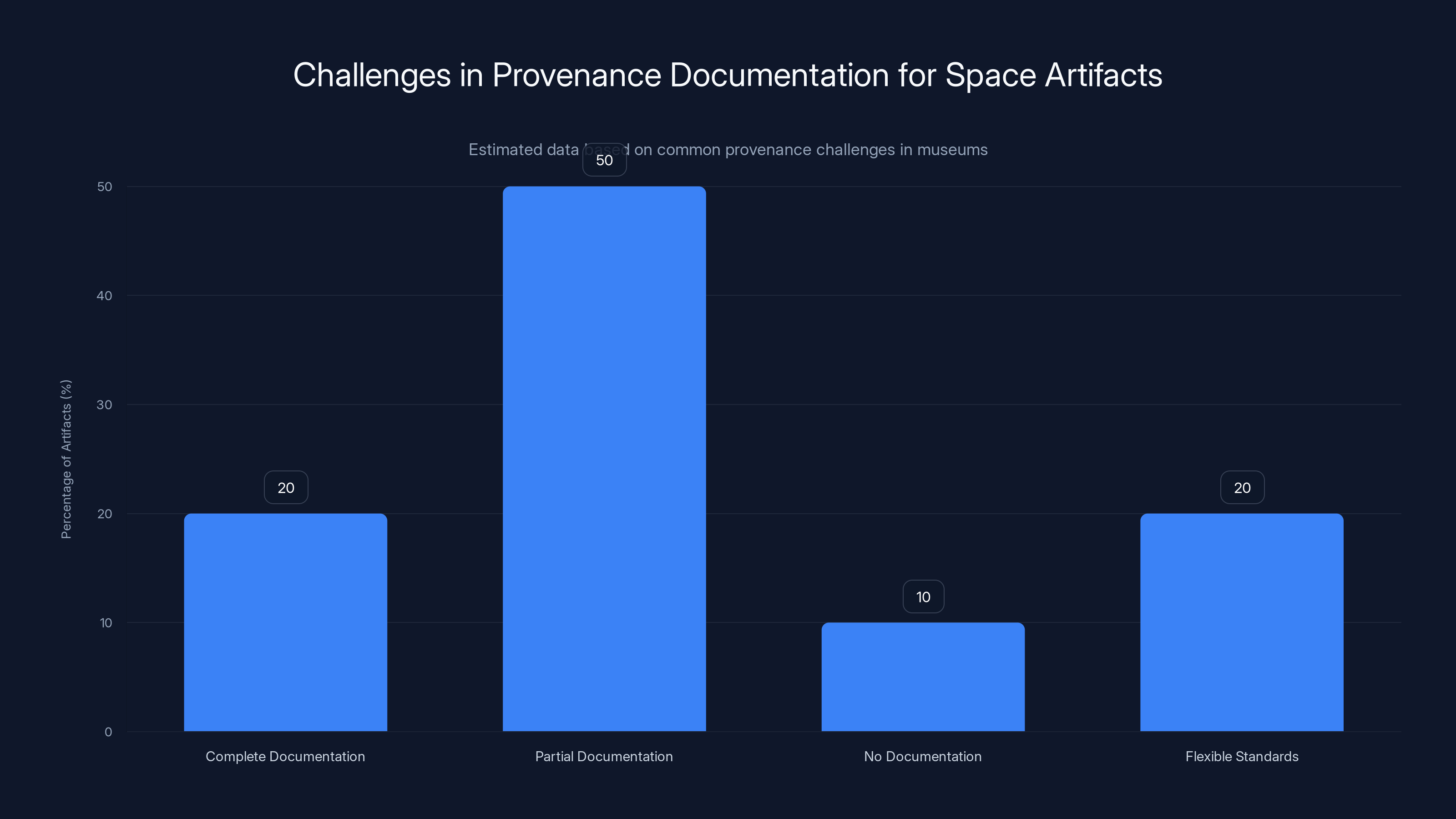

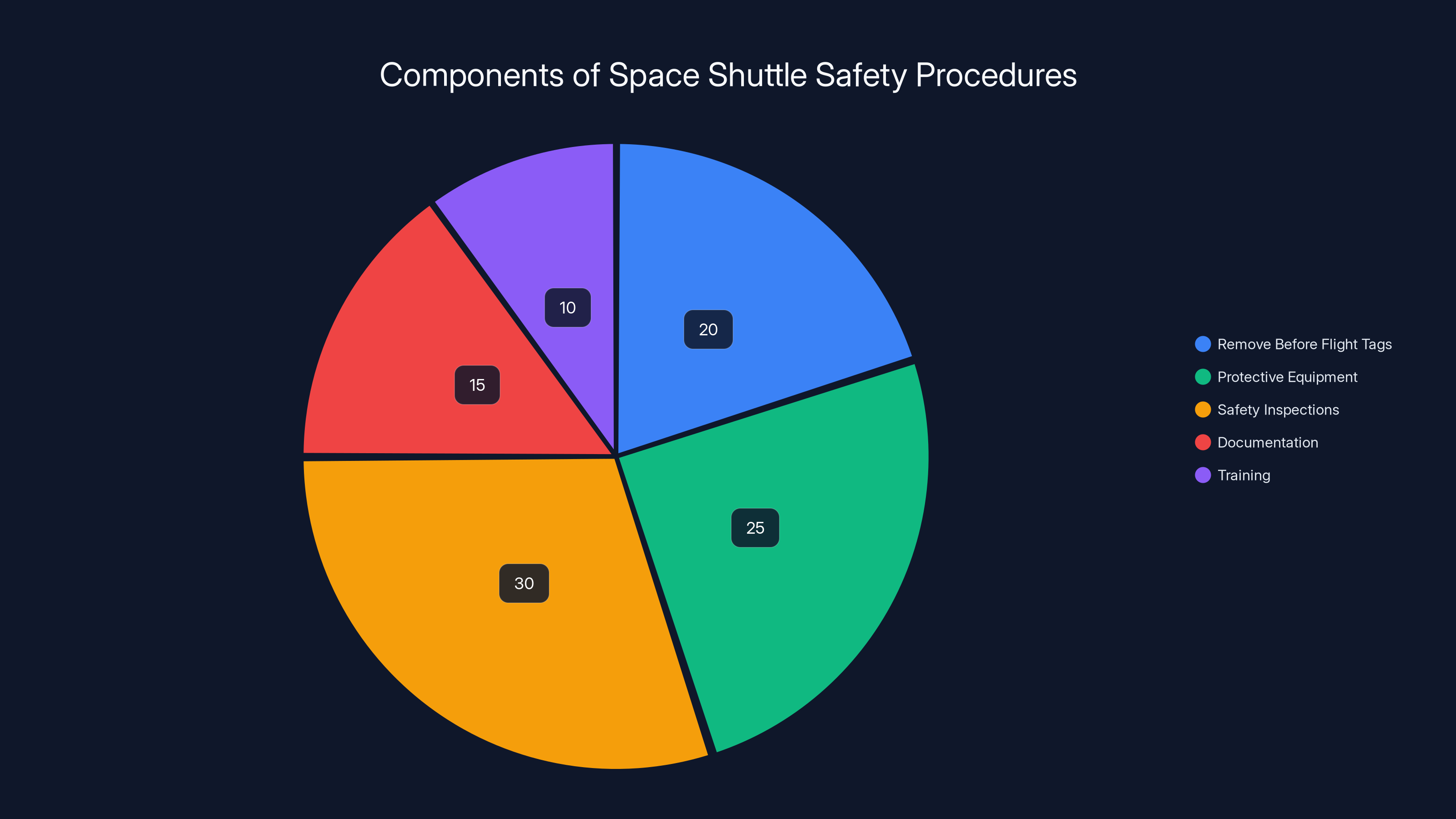

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of space artifacts have partial documentation, posing challenges for museums in meeting accession standards.

The Journey from eBay to Discovery: Understanding the Initial Purchase

When the tags first arrived in 2010, they seemed perfectly functional for an intended purpose. The collector who purchased them planned to distribute them as promotional items at space conferences, astronaut autograph events, space memorabilia shows, and classroom visits. These physical artifacts—pieces of real space hardware, even if they'd never actually reached orbit—could spark curiosity in young people and casual space enthusiasts. The tags represented tangible connection to the space program, a way to hold something that had been part of the largest and most complex vehicle humans had ever built.

The eBay listing provided minimal context. There was no claim about mission history, no mention of Challenger, no indication these weren't simply surplus manufacturing stock. For approximately a year after they arrived, the tags remained unremarkable in the collector's possession. They were stored alongside other space memorabilia, promising but not exceptional. The breakthrough came when the collector noticed something easy to overlook on the first examination: tiny ink stamps at the bottom edge of each tag.

The stamps were precise and small, the kind applied by ground crew members during manufacturing or assembly operations. They read "ET-26" followed by sequential numbers. The first tag in the clipped-together stack bore the stamp "ET-26-000006." Each subsequent tag had similar markings with different trailing numbers, suggesting they were part of a batch assigned to the same external tank. At that moment, the investigation began. What was ET-26? Which shuttle mission used this external tank? Was it still flying, or had it been part of a failed mission?

The detective work that followed relied on publicly available NASA documentation. A fact sheet prepared by Lockheed Martin, the aerospace contractor responsible for building external tanks at the Michoud Assembly Facility near New Orleans, provided the answer. The document listed every space shuttle launch paired with its corresponding external tank number and date. Tracing down the list revealed the grim confirmation: STS 51-L, January 28, 1986, ET-26. The tags had been attached to Challenger's external tank during assembly in New Orleans, remained with the tank throughout processing at Kennedy Space Center, and were removed as part of standard pre-flight procedures in the days or weeks before launch as reported by collectSPACE.

The realization transformed everything. What had seemed like generic surplus inventory became physical evidence of a tragedy. The tags themselves played no role in the accident—they were merely safety equipment marking points where protective covers or access doors needed to be removed before flight operations. But their association with that specific external tank, that specific mission, that specific date, gave them unexpected historical weight.

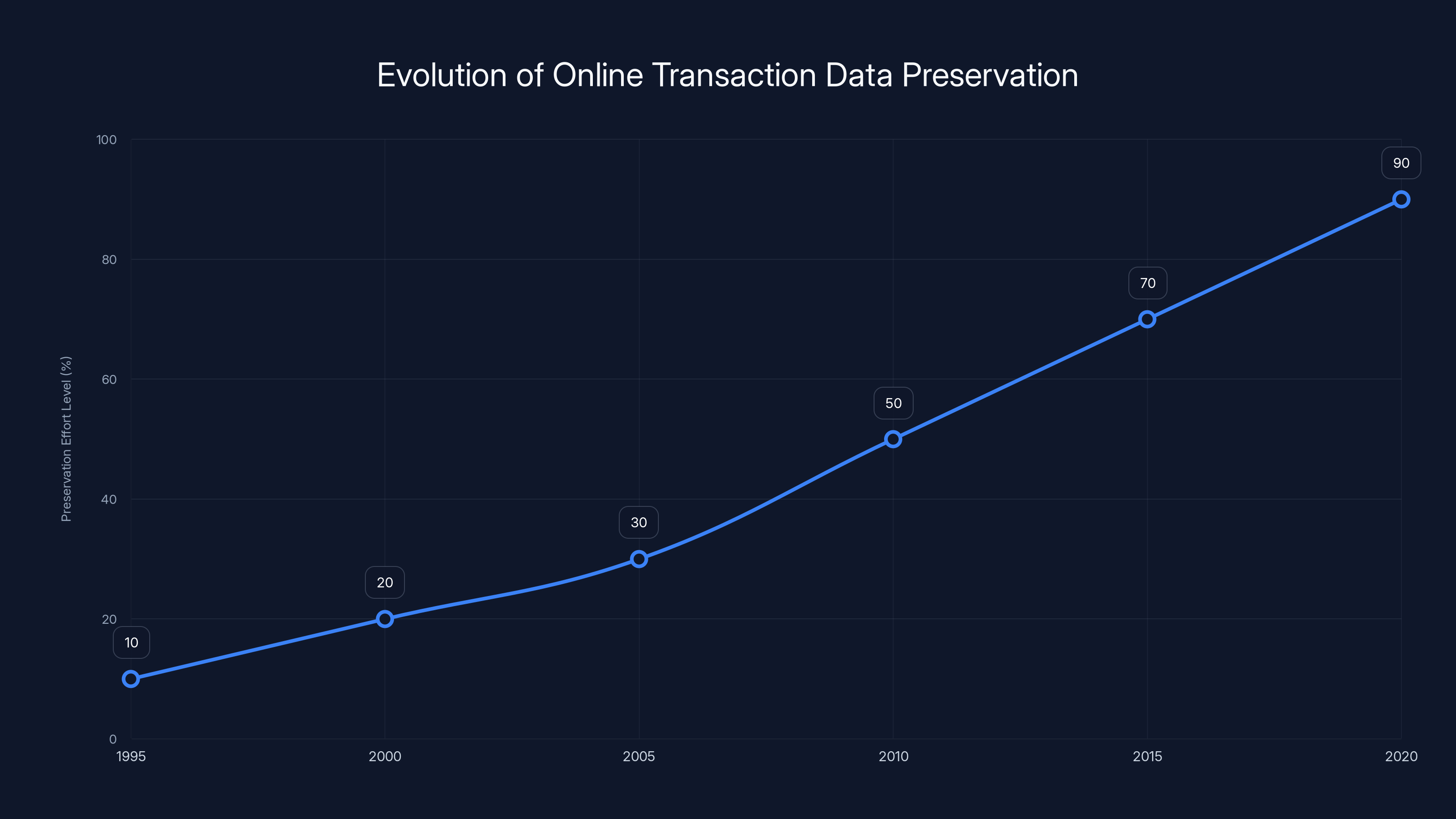

The chart illustrates the gradual increase in efforts to preserve online transaction data, with significant growth in the last decade. Estimated data.

Understanding Remove Before Flight Tags: Their Purpose and Evolution

The bright red tags bearing the "Remove Before Flight" designation might seem self-explanatory, but their role in space shuttle operations reflects decades of engineering culture and safety procedures developed across the aerospace industry. These tags didn't originate with NASA. They emerged from military aviation as a method for communicating urgent information to ground crews and pilots. The concept is straightforward: attach a visible warning to any component, cover, protective device, or plug that must be removed before the vehicle can operate safely.

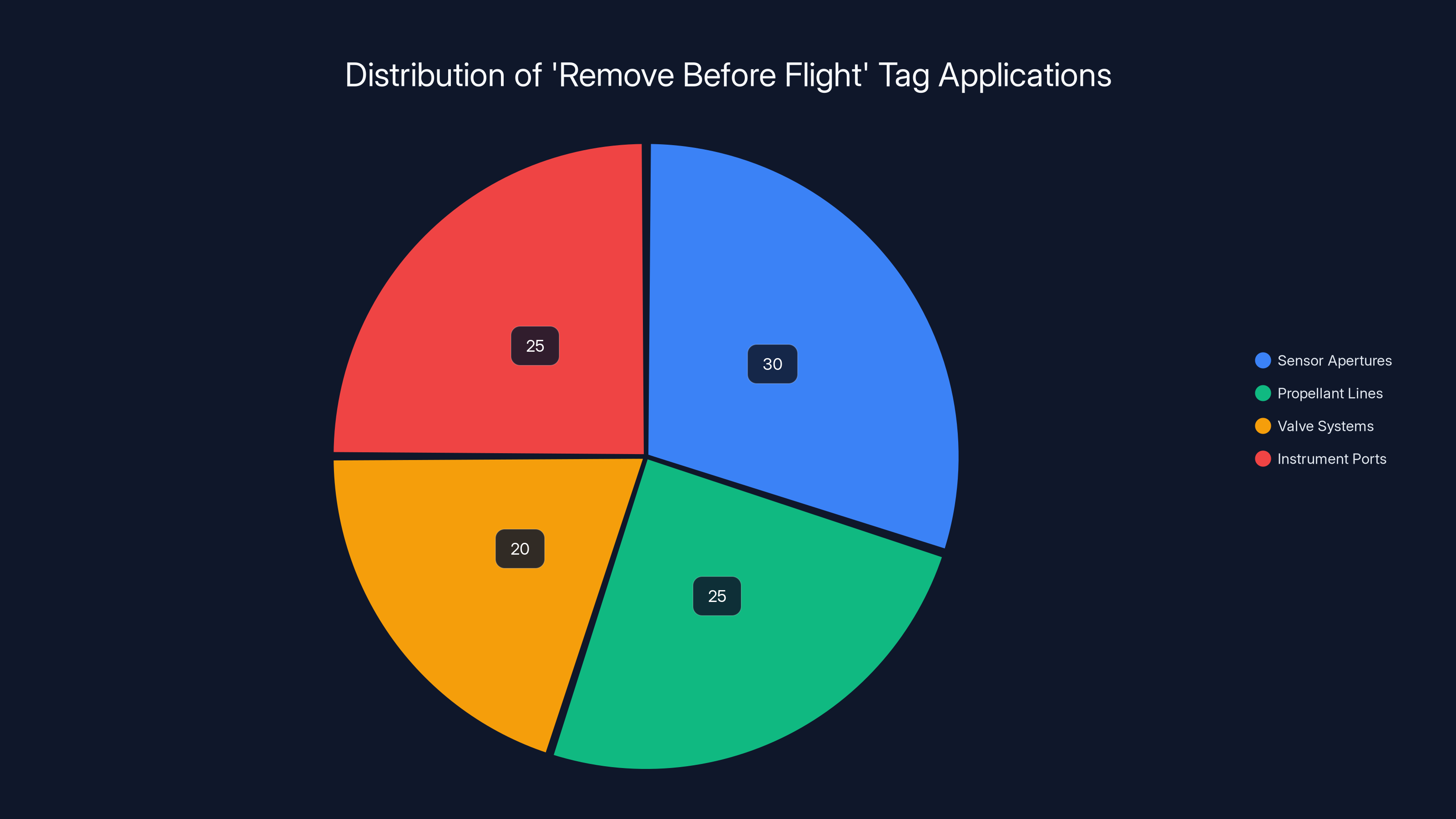

Space shuttle "Remove Before Flight" tags were attached to dozens of points across the entire vehicle stack. They marked the protective covers on sensor apertures, the caps on propellant lines, the blanking plugs in valve systems, the dust covers on instrument ports, and countless other access points that could expose sensitive equipment to contamination or damage. The external tank ET-26 would have carried these tags at locations where ground support equipment was connected or where protective measures were in place. Each tag served as a visual checkpoint for ground crews following pre-flight checklists.

The red fabric tag with eyelet holes allowed tags to be easily attached to equipment with string or wire, then removed cleanly without leaving adhesive residue. The bright red color provided high visibility against the external tank's burnt orange thermal protection. The reversible design meant crew members could see the warning from multiple angles. This simple design persisted across decades because it worked—it was reliable, reusable, and impossible to miss during final walkdowns. Ground crews working pre-flight procedures would physically locate every single "Remove Before Flight" tag, verify the corresponding checklist item, and remove the tag before the vehicle could be cleared for launch.

The KSC Form 4-226 designation represented the official NASA specification for these tags. The form number indicated this was a Kennedy Space Center-standardized component, approved for use across all space shuttle missions. Lockheed Martin, United Space Alliance, and various subcontractors all used identical tag designs manufactured to these specifications. Thousands of these tags were produced over the space shuttle program's thirty-year operational period. After tags were removed from a vehicle, the normal procedure was to keep them with associated ground support equipment paperwork, or in some cases, they were simply discarded as consumable items.

When the shuttle program generated spare or replacement tags, standard inventory management protocols would eventually move surplus items into the General Services Administration's excess property channels. These are the institutional mechanisms that eventually put random government-owned items into the civilian marketplace. Most space shuttle era surplus never commanded high prices because there were large quantities available. Only items with clear mission provenance—flight-qualified hardware that actually flew to orbit—attracted serious collectors. Tags that happened to be associated with a lost vehicle were even rarer, though many collectors didn't realize what they possessed.

ET-26: The External Tank for STS-51L

Understanding ET-26 requires understanding the role of the external tank in shuttle architecture. The external tank was the largest single structure in the entire space shuttle stack, a rust-colored or burnt orange cylinder roughly 154 feet tall and 27.5 feet in diameter. It served as the structural backbone of the assembled vehicle, holding not only the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants that fed the main engines, but also bearing the mechanical loads of the two solid rocket boosters strapped to its sides and the shuttle orbiter mounted on top.

ET-26 was one of the earliest external tanks, manufactured at the Michoud Assembly Facility during the middle years of the space shuttle development program. The tank arrived at Kennedy Space Center before STS-51L, was subjected to extensive ground processing, and had its protective thermal insulation applied. The insulation on this tank was initially painted white, though later photographs show the characteristic rust-colored appearance after reprocessing for flight. The tank underwent ordnance installation, pressurization system checks, sensor calibrations, and countless inspections before being mated to the solid rocket boosters and orbiter in late January 1986.

Mike Cianilli, who later served as manager of NASA's Apollo, Challenger, and Columbia Lessons Learned Program, explained the typical timeline for tag removal. "They were removed later in processing at different times but definitely all done before propellant loading," Cianilli stated. "To make sure they were gone, final walkdowns and closeouts by the ground crews confirmed removal." This meant the tags associated with ET-26 were removed days or even weeks before January 28. They were not among the final items touched before launch. The Challenger accident investigation would later focus intensely on every component of the external tank, as structural analysis proved that the tank itself had been compromised by hot gases burning through the structure as reported by Spectrum Local News.

The proximate cause of Challenger's loss was the failure of an O-ring seal in the right solid rocket booster, a failure enabled by unusually cold weather on the morning of launch. That O-ring failure allowed hot combustion gases to escape, impinging on the external tank's wall. Over the course of fifty-nine seconds of flight, these hot gases gradually burned through the tank structure and the attachment strut connecting the booster to the tank. Approximately seventy-three seconds into the flight, when aerodynamic stresses peaked during the transonic flight regime, the structural failure became catastrophic. The external tank separated from the orbiter, and the vehicle broke apart. The tags bore no responsibility for this chain of events as detailed by Britannica.

After the accident, approximately twenty percent of ET-26 was recovered from the Atlantic Ocean floor. The recovered components were retrieved by specialized salvage operations and eventually transported to the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, now known as Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. There, pieces of ET-26, along with hardware from the solid rocket boosters and the orbiter Challenger itself, were placed into storage in two retired intercontinental ballistic missile silos. These silos maintained environmental controls sufficient to preserve the hardware indefinitely, protecting it from weather and contamination. The location remains secure, though small portions of recovered Challenger hardware have been made available for museum exhibitions and educational purposes over the past four decades as noted by collectSPACE.

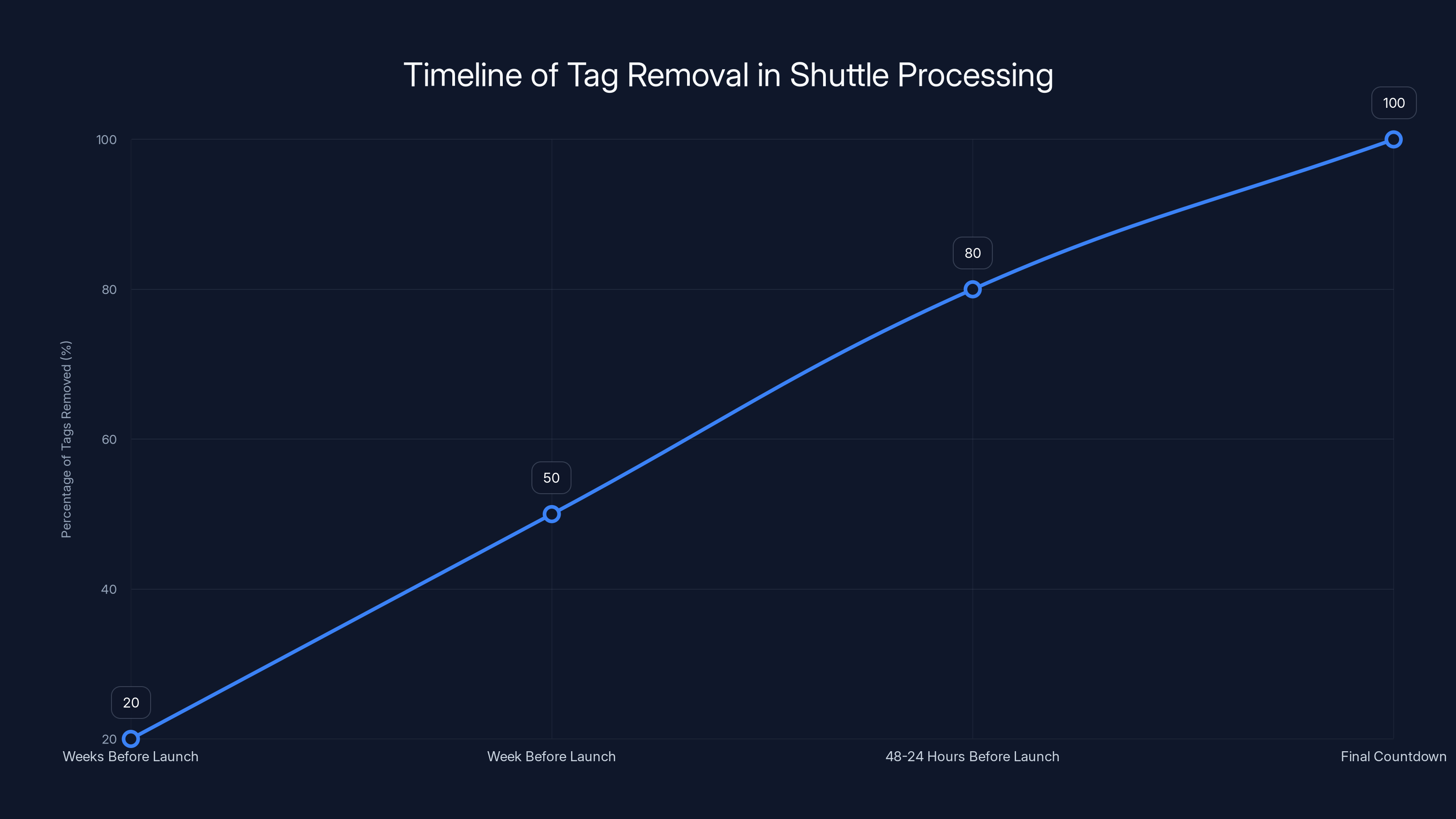

Tag removal was a gradual process, with most tags removed in the final week before launch. Estimated data.

The Discovery Process: Connecting Ink Stamps to History

The moment a collector holds a stamped artifact and begins the process of verification is essentially a mini-research project with real stakes. Getting the answer wrong could mean spreading misinformation about space history. Getting it right requires cross-referencing multiple authoritative sources and understanding the documentation systems that track shuttle-era equipment. In this case, the collector pursued a methodical approach, beginning with the most accessible public resources.

Lockheed Martin, the primary contractor responsible for external tank design and manufacture at the Michoud Assembly Facility, maintained and published fact sheets documenting every Space Shuttle flight paired with its corresponding external tank number. These documents were not classified and were available to space historians through multiple channels. The collector obtained one and methodically cross-referenced the ET-26 stamp. The search revealed exactly one match: STS 51-L, carrying Space Shuttle Challenger, scheduled for launch on January 28, 1986. There was no ambiguity in the record. Each external tank number appeared only once in the entire thirty-year space shuttle program because tanks were not reused between missions.

This confirmation created a moment of weight and responsibility. The tags were no longer simple promotional items. They were artifacts of one of the worst disasters in space exploration history. The collector recognized immediately that casual distribution as conference giveaways would be inappropriate. These items deserved a higher purpose. If their complete history could be documented—where they had been stored, by whom, through what institutions, and why they eventually ended up on eBay—they could potentially be transferred to museums, educational institutions, and astronautical archives. Proper provenance documentation is critical for any museum accession. Without a clear chain of custody, even authentic artifacts face barriers to acquisition and public display.

The challenge became apparent almost immediately. The original eBay listing was gone, archived in eBay's system in a way that prevented easy retrieval even decades later. An eBay spokesperson confirmed the company's policy: "eBay does not retain transaction records or item details dating back over a decade, and therefore we do not have any information to share with you." The seller's name, the exact date of purchase, the listing photographs, and the seller's stated provenance were all lost. The transaction existed only in the collector's memory and personal records. Attempting to reconstruct the tags' path through the surplus disposal system proved equally challenging.

NASA's normal procedure for surplus ground support equipment involved the General Services Administration, the federal agency responsible for excess property management. After items were declared surplus, they would be catalogued in GSA systems and offered for sale through established channels. For items from Kennedy Space Center in the 1990s and 2000s, disposal records might exist in GSA archives, but accessing and searching through decades of records for a specific batch of tags would require institutional resources and cooperation. The collector lacked both. What remained was documentation of the tags' existence, their physical characteristics, their serial numbers, and their irrefutable connection to ET-26 based on the engineering stamps they bore as highlighted by collectSPACE.

NASA's Process: When Tags Get Removed Before Flight

The actual removal of tags from Challenger occurred as part of a carefully choreographed sequence of operations that took place over weeks. Space shuttle processing was not a compressed activity—it was methodical, deliberate, and documented at every step. External tanks arrived at Kennedy Space Center weeks before scheduled launch. They underwent extensive testing and preparation. Protective covers were installed for launch operations. Ordnance systems were installed and armed. Pressurization packages were attached. The complete assembly was subjected to cryogenic tests, separation system checks, and structural load tests.

Throughout this processing, numerous "Remove Before Flight" tags would be attached at locations where protective equipment, launch supports, or ground connections were in place. Some of these tags would be removed during middle processing—for example, when protective covers over sensor ports were taken off and the sensors calibrated. Other tags would remain until very late in the countdown sequence. The tags indicating which ground support equipment connections needed to be disconnected would likely remain until the final hours before launch.

The Challenger accident investigation generated extensive documentation of pre-flight procedures, though most of this analysis focused on propellant loading, ordnance arming, and the final mechanical connections rather than on tag removal. Mike Cianilli's statement about removal timing reflected standard shuttle operations: tags were removed at different times during processing, but definitely completed before propellant loading began. Propellant loading occurred typically within the final 24 to 48 hours before launch, after which the vehicle was considered "loaded and ready" and only final system checks and countdown operations remained.

For the tags bearing ET-26 stamps, removal would have occurred sometime in the week before January 28. The process would have involved a ground crew member stationed at the tank's location, systematically locating each tagged item on the pre-flight checklist, verifying the protective item or connection was properly removed or checked, and then removing the tag itself. These tags would have been collected by the ground crew. Some might have been retained as part of launch documentation. Others might have been immediately discarded. The lack of formal inventory procedures for these consumable items meant that once they left the vehicle, their institutional tracking essentially ended.

This gap in documentation is crucial to understanding why reconstructing the path from Kennedy Space Center to an eBay seller two decades later proved so difficult. Ground support equipment and associated consumables often moved through informal channels once missions were concluded. If a contractor employee purchased surplus tags for personal use or as souvenirs, they would simply take them home. Years later, when moving or cleaning out collections, such items might appear on eBay or be donated to secondary markets. The formal tracking systems that documented flight hardware through multiple flights simply did not extend to consumable items like removable tags as noted by WebProNews.

Estimated data shows that 'Remove Before Flight' tags were evenly distributed across various critical components, ensuring comprehensive safety checks.

Recovery and Storage: What Happened After the Disaster

The recovery of Challenger debris occupied months of intensive effort. The disaster occurred at approximately 46,000 feet of altitude, roughly 73 seconds after launch. Wreckage was scattered across a wide area of the Atlantic Ocean, much of it sinking to depths of 800 to 2,000 feet. The United States Navy, working with NASA, deployed specialized salvage vessels, submersibles, and underwater recovery teams. The process was simultaneously a rescue operation, an investigation, and a recovery mission. The crew compartment, which authorities hoped might provide evidence about the final moments, was among the first major pieces located and recovered.

Over the following months, approximately twenty percent of the external tank ET-26 was recovered from the ocean. The remainder was either still on the ocean floor or had been destroyed beyond recognition. The recovered components included sections of the tank structure, insulation material, portions of the intertank region, and some attached plumbing and wiring. The recovery was photographed, documented, and carefully handled as evidence. Eventually, the recovered hardware was transported by specially equipped vehicles to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, approximately forty minutes north of Kennedy Space Center.

At Cape Canaveral, NASA maintained two retired Minuteman ICBM silos that had been repurposed for long-term storage of sensitive hardware. These silos provided environmental protection—controlled temperature, controlled humidity, and protection from weather and external contamination. The silos were secured and accessible only to authorized personnel. Pieces of Challenger, the solid rocket boosters, and ET-26 were carefully placed into storage in these silos. The facility became a de facto memorial and archive, containing the physical remains of the disaster. Over subsequent decades, small portions of the Challenger hardware have been made available to museums for exhibition, particularly to major institutions like the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.

NASA established strict protocols for the disposition of recovered Challenger hardware. The physical remains were treated with respect appropriate to a mass casualty event. No components were sold or transferred to private individuals. All recovered material was catalogued and stored as part of the investigation record and historical archive. This policy continued through the subsequent Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, when similar protocols governed the recovery and storage of Columbia debris. The fundamental principle was clear: hardware from a lost vehicle represented sacred artifacts of tragedy and belonged in institutional custody, not private hands.

However, the tags that were removed before flight never entered this formal recovery and storage system. They were never part of the vehicle at launch. They had been detached during processing, likely collected by ground crews, and entered whatever institutional disposal processes existed for consumable items. That these tags survived decades in institutional or private storage before appearing on eBay represents a kind of accident in itself—the kind of accident that gave a collector the opportunity to discover history by chance as highlighted by collectSPACE.

The Challenge of Provenance Documentation

Museum accession standards require what is known as "provenance"—a documented chain of custody explaining how an artifact passed from its original source through various holders until arriving at the institution seeking to acquire it. For authenticated artifacts from the space program, this documentation is critical. A piece of hardware claiming to be from a specific space shuttle mission must be able to demonstrate how that claim is supported. For flight-qualified hardware, this is often straightforward because NASA and contractors maintain meticulous records of every component that flew.

But for ground support equipment and consumables like tags, the documentation gaps are substantial. The tags bearing ET-26 stamps could be definitively linked to the external tank through their markings. But their complete history from removal during pre-flight processing through storage, surplus disposition, transfer to the secondary market, and eventual sale on eBay remained incompletely documented. The original seller's identity, the exact removal date, which contractor or facility held the tags during the intervening years, and why they eventually entered the surplus system all remained unknown.

Museum professionals face genuine dilemmas when assessing such items. Authenticating the artifact itself is possible through physical inspection, stamp analysis, and comparison with known examples. Authenticating its mission association is straightforward given the ET-26 stamps and cross-reference with flight records. But assessing whether every step of the chain of custody meets accession standards is difficult without complete documentation. Some museums have more flexible standards than others. Major institutions often require near-perfect provenance. Smaller institutions or those focused specifically on space history may be more accepting of artifacts with partial documentation if the artifact itself is undeniably authentic.

The collector who discovered the tags recognized that completing the documentation chain was essential if the artifacts were ever to find a proper institutional home. The logical first step would be attempting to identify the original eBay seller and reconstruct their acquisition of the tags. The second step would involve researching GSA surplus records to understand how the tags entered the civilian marketplace. The third step would involve correlating removal procedures with likely time frames for tag disposal. Each of these steps faced substantial obstacles.

Attempts to retrieve the original eBay listing through archival services or eBay's internal systems failed. eBay's policy of not retaining transaction details beyond a decade meant that formal records simply did not exist. Reaching out to potential surviving witnesses—ground crew members or contractors who might have been present during Challenger's processing—was speculative. Most of these individuals have either retired or passed away during the four decades since 1986. Their personal memories and records might exist somewhere, but locating them would require extensive networking through space shuttle community channels.

Estimated data showing the distribution of various safety components in space shuttle operations, highlighting the role of 'Remove Before Flight' tags.

Public Display and Preservation: The Broader Context

One of the most striking facts about Challenger's legacy is how little of the actual vehicle is available for public viewing. Only one physical piece of Space Shuttle Challenger is on permanent public display: a crew cabin window displayed in the exhibition "Forever Remembered" at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. This single artifact represents all that most of the American public will ever see of the orbiter that carried seven crew members to their deaths. The restraint in public display reflects NASA's philosophy that the recovered hardware deserves respect and that excessive public exhibition might be perceived as exploitative.

Yet this restraint creates a challenge for educators, museums, and institutions seeking to help people understand the reality of space exploration. Physical artifacts carry power that photographs or video cannot replicate. Holding an object that was actually involved in a significant historical event—or in this case, being in the presence of such an object—creates a different kind of understanding than abstract learning. The collectors, museums, and educators who were given small pieces of Challenger during the early years after the disaster understood this principle. Each of the fifty United States was presented with a small American flag and mission patch that had been aboard Challenger at the time of the tragedy. These items now reside in state museums and institutions across the country.

The Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex maintains extensive collections related to the shuttle program, but the physical constraints on display space and the philosophical decisions about appropriate exhibition mean that most of these collections are in storage rather than on public view. Museum curators regularly face decisions about whether an artifact is worthy of acquisition and display, what story it tells, whether it fills a gap in the existing collection, and whether the museum has the resources to properly care for it. For artifacts with clear mission association and historical importance, these decisions become easier. For items with partial provenance documentation, the decisions become harder.

The tags bearing ET-26 markings could serve important educational purposes. In a classroom setting, holding an object that was actually attached to Challenger—even though it was removed days before launch—could make the reality of space shuttle operations tangible for students. The tags could demonstrate how ground crews worked, what safety procedures looked like, and how even small components carried meaning in a complex system. In a museum context, the tags could be displayed alongside educational materials explaining the space shuttle stack, the role of the external tank, and the importance of pre-flight procedures. They could serve as jumping-off points for conversations about the Challenger disaster itself.

Several major space museums and institutions have expressed interest in artifacts with clear Challenger provenance. The Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum maintains extensive space shuttle collections but has limited display space. Regional space centers, science museums with aerospace exhibits, and educational institutions focused on STEM would likely have interest in acquiring such artifacts if proper documentation could be provided. The challenge lies in getting the documentation complete enough to meet accession standards. The collector who owns the tags faces a decision: continue attempting to reconstruct the complete chain of custody, or approach institutions with the documentation that does exist and hope that the clear artifact authentication and mission association are sufficient to overcome provenance gaps.

Space Program Material Culture: Why These Tags Matter

There's a broader discussion in space history about how we remember the space program through physical objects. In academic history, this falls under the umbrella of "material culture studies"—the understanding that objects encode meaning, reflect the values and practices of the people who created them, and provide primary evidence about how complex systems actually functioned. The "Remove Before Flight" tags are humble objects. They're made of simple materials. They carry no advanced technology. They were expendable and replaced routinely. Yet they embody crucial aspects of space shuttle culture.

The tags represent safety consciousness built into daily operations. They represent the standardization and consistency that aerospace engineering demands. They represent documentation and accountability. Each tag stamped with ET-26 and a number created a tracking point, a moment where a ground crew member was forced to engage with that specific item as part of the pre-flight checklist. This kind of deliberate, systematic engagement with every component is what makes space operations work at all. The contrast between how carefully these tags were used during pre-flight processing and how casually they were eventually discarded highlights the temporal nature of space operations—these items served their purpose and then had no further value, until years later when their association with a tragedy made them historically significant.

Collecting space memorabilia is a widespread hobby, but it raises interesting questions about appropriate ownership and stewardship of space-related artifacts. Should items associated with the space program be in institutional or private hands? How do we preserve space history in ways that respect both institutional needs and individual collectors? The person who owns these ET-26 tags faces these questions in practical form. Keeping them in private collection, even well-intentioned, means they're available only to that individual and their immediate circle. Transferring them to an appropriate museum or archive means they become accessible to researchers, students, and the public, but it requires surrendering personal ownership.

Many space enthusiasts and collectors accept this trade-off willingly. They understand that major institutions can provide the resources, expertise, and public access that private collectors cannot. The challenge is usually finding the right institution and ensuring that the artifact meets that institution's accession standards. For items with clear provenance, this is straightforward. For items like these tags, where the provenance is partial, the process becomes more complex. But it's not impossible. Institutions acquire items with partial documentation regularly. What matters is transparency about what is known and what is not known, honest assessment of what the artifact actually demonstrates, and clear documentation of the physical evidence that supports the attribution.

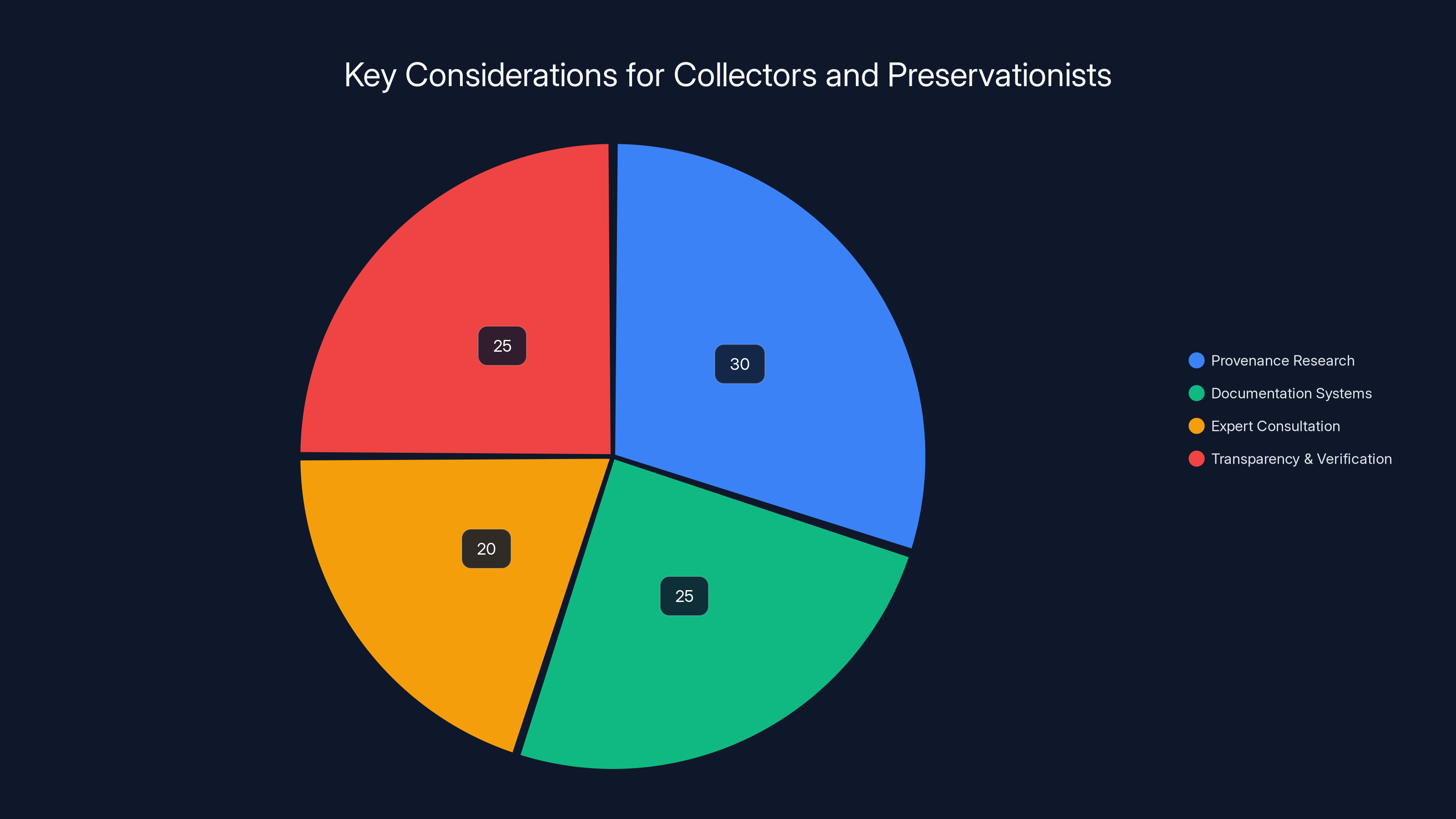

Estimated data shows that provenance research and transparency are equally important for collectors and preservationists, each comprising 30% of their focus.

The eBay Transaction and Lost Information: A Documentation Failure

The fact that the original eBay listing could not be retrieved forty years after the transaction highlights a broader problem in how we preserve information about transactions and transfers of artifacts. eBay was founded in 1995 and became the dominant platform for collecting goods of all kinds, including space memorabilia. The site's lack of long-term data retention reflects its design as a transaction platform rather than an archive. Each transaction was treated as a temporary event, completed and then abandoned from the platform's perspective. The seller's reputation and transaction history remained visible only as long as the seller maintained an account. Once a seller abandoned their account or deleted transaction history, the detailed information disappeared.

This is typical of early-stage internet commerce. Platforms were designed for the current transaction, not for future historians. The principle of information preservation simply didn't factor into the architecture. Only in recent years have platforms, institutions, and archivists begun systematically preserving online transactions and digital records for future research. The Library of Congress now maintains the "Wayback Machine" and other digital archive projects, but these systems only capture snapshots of content that was publicly visible on websites. eBay listing details have only been partially captured, depending on when the Wayback Machine happened to crawl the site.

For space memorabilia sellers, eBay was and remains a common marketplace. Items would appear from sources ranging from former contractor employees liquidating collections, to estate sales of deceased enthusiasts, to individuals who inherited space-related items without understanding their significance. Tracing the origins of items sold through eBay typically requires either contacting the seller directly—if they can be identified and if they remember the transaction—or relying on information provided in the original listing, which the buyer hopefully recorded or photographed at the time of purchase.

The collector who purchased these tags was fortunate to have the presence of mind to photograph the physical tags and document their appearance and markings. The eBay listing itself was not preserved, but the physical evidence on the tags—the KSC Form 4-226 designation, the ET-26 stamps, the sequential numbering—provided sufficient information for later verification. This underscores the importance of collectors maintaining detailed records of their acquisitions. A photograph of the original listing, the seller's name, the date of the transaction, and the exact price paid would have been valuable pieces of provenance information. Without these details, the documentation chain begins with the collector's possession rather than with the marketplace transaction.

For anyone acquiring artifacts through online marketplaces, the lesson is clear: document everything while the listing is still visible. Screenshot the full listing with all available details. Record the seller's username and feedback rating. Save the exact date and time of the transaction. Keep receipts and payment confirmations. The more documentation created at the moment of acquisition, the easier it becomes later to verify authenticity and establish proper provenance if the artifact later proves to have historical significance.

Future Possibilities: Museums and Educational Impact

Looking forward, several pathways exist for these ET-26 tags to eventually reach appropriate institutional homes. The most direct approach would be reaching out to the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, which maintains the most extensive Challenger-related collections and exhibitions. The curatorial staff there is deeply familiar with Challenger artifacts and understands the accession requirements for items with mission associations. They could assess whether these tags meet the standards for acquisition, what additional documentation might be helpful, and how the items might be integrated into existing exhibitions.

Alternatively, the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum could be approached. The museum maintains vast collections of space shuttle-related materials, though much is in storage rather than on display. The curators there have experience with acquisition of artifacts with partial provenance documentation and understand the historical significance of items that pre-date the disaster even though they were never flown. The museum might be interested in acquiring the tags specifically because of their rarity—objects that were actually processed with a specific space shuttle vehicle but never flew are uncommon.

Regional institutions focused on space history, science centers with aerospace exhibits, or educational institutions with strong STEM programs represent additional possibilities. A smaller institution might have greater flexibility in acquisition standards and might be particularly interested in items that could serve educational purposes. The tags could be displayed alongside explanatory materials about shuttle processing procedures, with the full history—including the discovered connection to Challenger—explained in the exhibition text. This would make the partial provenance gap transparent while highlighting what the artifact does demonstrate.

Another possibility involves collaborative approaches. The collector might work with space history researchers or archivists to publish documentation of the tags' discovery and the methodology used to establish their connection to ET-26. Such publication would create permanent scholarly documentation of the artifact and its significance. This published record could then serve as provenance documentation that institutions could reference in their accession records. The story itself—how the tags were acquired, how the discovery was made, what challenges remain in the documentation—becomes part of the artifact's historical significance.

The broader impact of these tags becoming more widely known involves public engagement with space history. If the tags eventually find their way into exhibitions, they would represent a tangible connection for visitors to the Challenger mission and the space shuttle program more broadly. School groups, students, and researchers could interact with authentic artifacts from the actual space program. The story of how the tags were discovered, what challenges exist in preserving space program materials, and what these small objects tell us about how NASA operated could inspire interest in space history among new generations. This is precisely the kind of impact the original collector envisioned when considering how to best use the tags.

Lessons for Collectors and Preservationists

The experience of discovering that casually purchased items carry significant historical meaning offers lessons applicable far beyond space program memorabilia. The principle is broadly relevant: objects in the commercial marketplace can carry histories that are not apparent from their initial presentation. Collectors, archivists, and institutions all benefit when individuals take time to research and document the items they possess. The challenge of reconstructing provenance—establishing how an item moved through time from its origin to the present—is common across all collecting disciplines.

For space memorabilia collectors specifically, the lesson is to understand the basic documentation systems that track space hardware. Knowing the differences between flight-qualified hardware and ground support equipment, understanding how external tanks were numbered, and being familiar with the basic chronology of the space shuttle program provides frameworks for authenticating acquired items. When uncertainty exists, consulting with space history experts, reaching out to NASA personnel or contractors who might have relevant knowledge, and publishing research through community channels can help establish facts.

For institutions and archivists, the lesson involves balancing strict provenance standards against the reality that important artifacts sometimes enter the marketplace with incomplete documentation. The question is not whether to accept such items, but how to do so responsibly. Transparency about documentation gaps, honest assessment of what can and cannot be verified, and clear presentation of physical evidence all contribute to responsible acquisition. The tags' ET-26 stamps and sequential numbering are physical evidence that can be examined by multiple experts. Cross-referencing with NASA's flight records provides corroboration. These elements together establish a strong case for authenticity and mission association even if the complete chain of custody remains undocumented.

For digital preservation, the lesson is the critical importance of capturing transaction records and marketplace listings. The specific details from the original eBay listing—the seller's description, the claimed provenance, the date of listing, the price—would all be valuable pieces of information. While major institutions now understand the importance of preserving digital records, individual collectors and small institutions can also participate by documenting and archiving information about their acquisitions. A simple database or spreadsheet recording when and where items were acquired, what documentation existed at the time of purchase, and what subsequent research revealed would preserve information that otherwise disappears.

Broader Reflections: Objects, Memory, and Meaning

Physical artifacts carry power in ways that abstract information cannot fully capture. A photograph of a "Remove Before Flight" tag communicates certain information about its appearance and design. Holding an actual tag—feeling the weight of the fabric, seeing the actual ink stamps, reading the precise designations in the creator's handwriting—creates a different kind of understanding. This is why museums collect physical objects rather than simply displaying photographs. The direct encounter with an authentic artifact creates a connection to history that is more immediate and more memorable than any representation.

When that artifact carries association with a tragedy like the Challenger disaster, the power of this connection intensifies. Standing in front of an object that was actually handled by ground crew members preparing a vehicle that would be lost, seeing the careful technical designations that indicate how seriously the work was taken, and understanding the gap between normal competence and exceptional catastrophe—all of this becomes tangible and visceral in a way that words alone cannot convey. This is why even small pieces of lost spacecraft matter. They carry meaning that extends far beyond their physical substance.

The discovery that casual eBay purchases could carry this weight, this meaning, this connection to tragedy and history suggests something important about how we encounter the past. History is not confined to museum exhibitions or academic publications. It moves through the world in physical forms. It appears in unexpected places. It requires attention and curiosity to recognize. The collector who noticed the ET-26 stamps on the bottom of those tags demonstrated the kind of engaged curiosity that allows history to be preserved and understood.

There's also something poignant about the journey these tags took. They were manufactured as functional safety equipment. They served their purpose during processing operations. They were removed from Challenger days before launch, detached from the vehicle that would carry them no further. They entered institutional disposal systems and eventually moved into private hands through the civilian marketplace. For more than a decade, they were held unknowingly by someone who appreciated them for the wrong reasons—as generic promotional items rather than as artifacts of a specific historical event. Then, at a moment of casual attention to detail, they were recognized for what they actually were. That recognition transformed them from items of minor significance to artifacts worthy of preservation and study.

The Ongoing Quest for Documentation

The collector who owns these ET-26 tags continues working to establish a complete provenance record. The process involves multiple lines of inquiry, each with limitations but potentially adding pieces to the puzzle. Reaching out to former Kennedy Space Center employees and contractors through space enthusiast communities, searching GSA surplus records through Freedom of Information Act requests, consulting with museum curators about accession standards, and exploring options for publishing documentation of the discovery all represent possible paths forward.

The reality is that a completely perfect chain of custody may never be reconstructed. The information gap between when the tags were removed from Challenger in January 1986 and when they appeared on eBay in the mid-2000s may never be completely filled. Some documentation may have been lost to the simple passage of time, institutional records disposal, or the deaths of individuals who were present when the tags were handled. But documenting what can be known, publishing that documentation through appropriate channels, and being transparent about what cannot be verified creates an acceptable and responsible approach to the artifact's provenance.

This is how historical records are actually built. Not through perfect documentation that emerges cleanly from institutions, but through the patient assembly of partial records, the thoughtful analysis of physical evidence, and the collaborative work of collectors, institutions, and researchers who recognize the value of the material and commit to preserving it. The tags themselves are silent witnesses. They cannot tell their own story. But the person who recognizes their significance, the researchers who verify the connection, and the institution that eventually accepts responsibility for their preservation all participate in the process of translating physical objects into historical documentation.

Conclusion: Where History Meets Chance

The story of the Challenger "Remove Before Flight" tags is ultimately a story about how history moves through the world in unexpected ways. A functional piece of equipment manufactured decades ago, processed with a specific space shuttle vehicle, removed before flight operations, and then lost in the machinery of institutional surplus disposal suddenly emerges into consciousness as historically significant. The transformation happened not through any deliberate act of preservation but through the chance combination of the tags eventually reaching a collector who paid attention to details, noticed the stamps, and took the time to research what they meant.

Forty years after the Challenger disaster, when most Americans encounter the event through historical documentation and remembrance, a small collection of physical objects that touched the space shuttle suddenly becomes available for deeper study and potential preservation. These tags represent more than curiosities or collectibles. They embody the careful, methodical work of thousands of people who processed Challenger for launch. They carry the weight of understanding that even in the best-run operations, catastrophe remains possible. They demonstrate the importance of documenting and preserving the physical record of human spaceflight, including the small components that most people never see.

If and when these tags eventually reach a museum or archive, they will represent a successful conclusion to a journey that began with an eBay purchase and continued through years of patient research and documentation. They will serve as educational tools helping visitors understand how space operations actually work, what care and attention ground crews bring to their work, and how we preserve the memory of tragedy through physical objects. They will also stand as a reminder that history is not just something that happens in textbooks or museums. It moves through the world in physical forms, waiting to be recognized by people who pay attention.

The challenge now lies in completing the documentation in ways that meet institutional standards while being honest about the gaps that may never be filled. The opportunity lies in converting what began as casual curiosity into serious historical preservation. The responsibility falls on collectors, institutions, and researchers to work together to ensure that even humble artifacts—small tags that no one would have paid attention to under normal circumstances—receive the care and attention that their connection to significant events demands. This is how history is really preserved: not through perfect systems, but through the collective attention of people who recognize significance and commit to remembering.

FAQ

What are "Remove Before Flight" tags and why do they matter?

"Remove Before Flight" tags are bright red safety identification markers used throughout aerospace to identify temporary protective equipment, covers, plugs, and connections that must be removed before a vehicle can operate safely. On the Space Shuttle, hundreds of these tags marked protective devices during ground processing. They matter because they represent the meticulous safety culture of space operations and connect us to the physical reality of how spacecraft are prepared for flight.

How were the tags connected to Challenger?

The collector discovered ink stamps reading "ET-26" on the bottom of the purchased tags. Cross-referencing this designation against Lockheed Martin's documentation of Space Shuttle flights revealed that ET-26 was the external tank used for STS-51L, the ill-fated Challenger mission on January 28, 1986. The tags had been attached to this specific tank during assembly and processing at Kennedy Space Center.

What role did these tags play in the Challenger disaster?

The tags had no role in the accident. They were removed from the vehicle during pre-flight processing, days or weeks before launch, well before the O-ring failure in the solid rocket booster that led to structural failure. The tags simply represent the normal preparation procedures that preceded the mission.

Why is the provenance of these tags difficult to establish?

The original eBay listing is no longer accessible, as the platform does not retain transaction details beyond a decade. The seller's identity and the path the tags took through institutional storage or surplus disposal systems remain undocumented. This gap between removal in 1986 and appearance on eBay in the 2000s represents a period where the tags' whereabouts and handling are largely unknown.

Could these tags eventually become museum exhibits?

Yes, though it requires meeting institutional accession standards. The Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum, or regional space museums could potentially acquire the tags if documentation proves satisfactory. The collector has been working to establish proper provenance and explore acquisition opportunities with appropriate institutions.

Why should institutions care about small items like tags when so much Challenger hardware remains in storage?

These tags are rare artifacts that were actually processed with the specific vehicle. They can serve important educational purposes, helping visitors understand shuttle operations and create tangible connections to the space program. Physical artifacts carry pedagogical power that photographs or videos cannot replicate, particularly when addressing historical events as significant as the Challenger disaster.

What do these tags tell us about space program culture?

The tags embody the systematic, methodical approach to safety that characterizes professional aerospace operations. The fact that each item was marked, tracked, and verified during checklists demonstrates the attention to detail and accountability that guides space operations. This culture of systematic care is what allows complex systems to function reliably despite their inherent risks.

Could items I own be historically significant without my knowing it?

Possibly. Items purchased through secondary markets or online platforms may carry histories not apparent from initial descriptions. Researching serial numbers, designations, manufacturer marks, and cross-referencing with official records can reveal surprising connections. If you own items potentially related to significant historical events, consulting with subject matter experts can help establish what you possess.

What is the broader significance of preserving space program artifacts?

Physical objects provide direct connection to historical events in ways that abstract information cannot. When artifacts are lost, opportunities for education, remembrance, and understanding are diminished. Preserving even small items like these tags ensures that future generations can encounter and learn from authentic evidence of human spaceflight history.

What should collectors do if they discover their items have unexpected historical significance?

Document everything available about acquisition: where purchased, when, from whom, original listing details if possible, and any documentation that accompanied the item. Research systematically using available resources. Consider consulting with relevant institutions or experts. Be transparent about what is and isn't documented. Think seriously about whether institutional custody might better serve the artifact's long-term preservation and educational impact.

Key Takeaways

- A collector discovered that eBay-purchased tags from 2010 bore ET-26 stamps, linking them to Challenger's external tank from the STS-51L mission as reported by collectSPACE.

- The tags were removed during pre-flight processing days or weeks before launch and played no role in the disaster itself as noted by Britannica.

- Complete provenance documentation remains challenging due to missing eBay records and undocumented institutional storage from 1986 to the 2000s as highlighted by collectSPACE.

- Museums could acquire these artifacts to provide tangible educational tools about Space Shuttle operations and preserve memory of the disaster as reported by the Concord Monitor.

- This discovery highlights how space program artifacts exist in unexpected places and the importance of careful documentation by collectors as discussed in Nature.

![The Challenger Remove Before Flight Tags: A 40-Year Mystery [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-challenger-remove-before-flight-tags-a-40-year-mystery-2/image-1-1769625465592.jpg)