ICE Out of Our Faces Act: Facial Recognition Ban Explained [2025]

Imagine an agent from Immigration and Customs Enforcement scanning your face without your knowledge or consent. Then imagine that data fed into a database labeling you as a "domestic terrorist" simply for observing an immigration raid or protesting government policy.

This isn't science fiction. It's happening right now in America.

In early 2026, Senate Democrats introduced the "ICE Out of Our Faces Act," a legislative response to growing concerns about how federal immigration agencies deploy facial recognition and other biometric surveillance technologies. The bill, led by Senator Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts, represents one of the most aggressive legislative pushbacks against immigration agency surveillance in recent years.

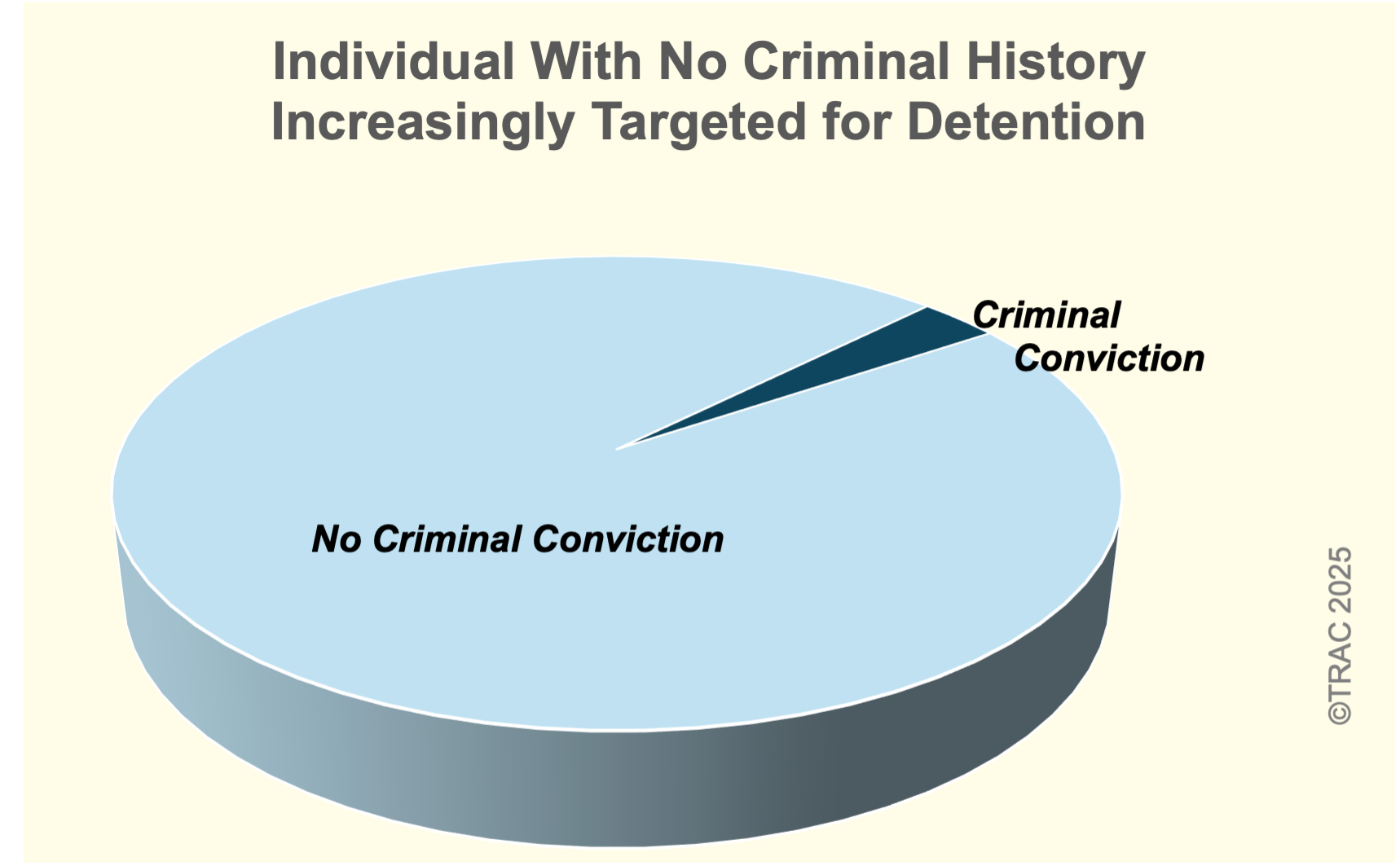

But here's what makes this moment significant: it exposes a fundamental tension in modern governance. Immigration enforcement agencies argue they need advanced surveillance tools to protect national security and catch dangerous criminals. Civil liberties advocates argue these same tools are being weaponized against ordinary Americans exercising First Amendment rights.

This article breaks down everything you need to know about the ICE Out of Our Faces Act, how facial recognition surveillance actually works within immigration agencies, the real-world implications for privacy and civil liberties, and what this means for the future of immigration enforcement in America.

TL; DR

- The Bill: Senate Democrats introduced the ICE Out of Our Faces Act to ban ICE and CBP use of facial recognition and other biometric surveillance technologies, with private right of action for affected individuals.

- Current Reality: Immigration agents are actively using face-scanning technology against protesters, observers, and people exercising First Amendment rights, according to court filings and agency communications.

- Data Collection: Agencies maintain databases linking protesters and observers to "domestic terrorist" labels, raising questions about constitutional protection and government overreach.

- Legal Right: The bill would allow individuals to sue the federal government for financial damages after violations, with state attorneys general able to bring suits on behalf of residents.

- Political Reality: With Republicans controlling Congress, the bill faces nearly zero chance of passage, but signals growing bipartisan concerns about surveillance state expansion.

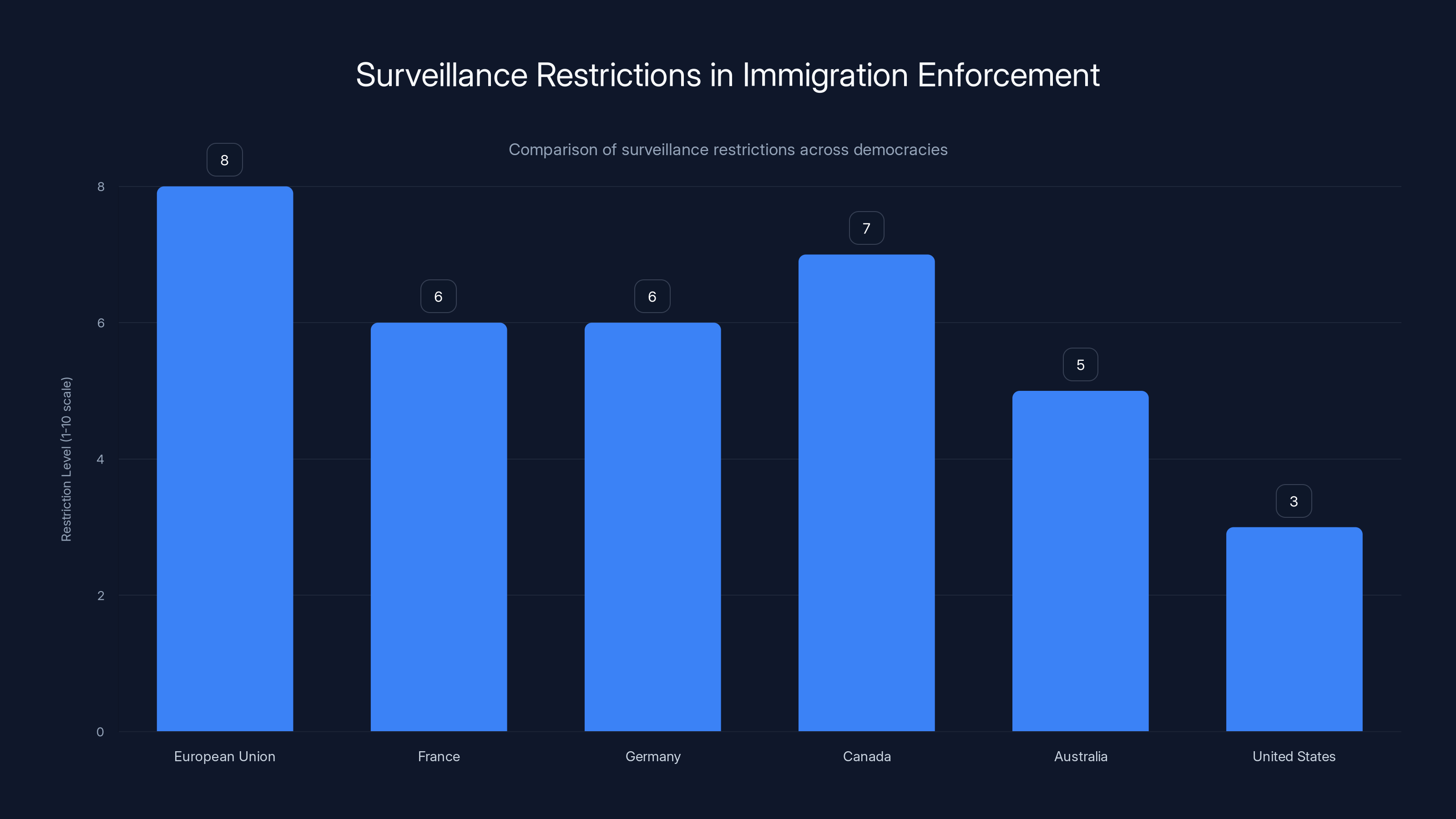

European Union and Canada have higher surveillance restrictions due to strong privacy laws and oversight, while the US has more permissive policies. (Estimated data)

What Exactly Is the ICE Out of Our Faces Act?

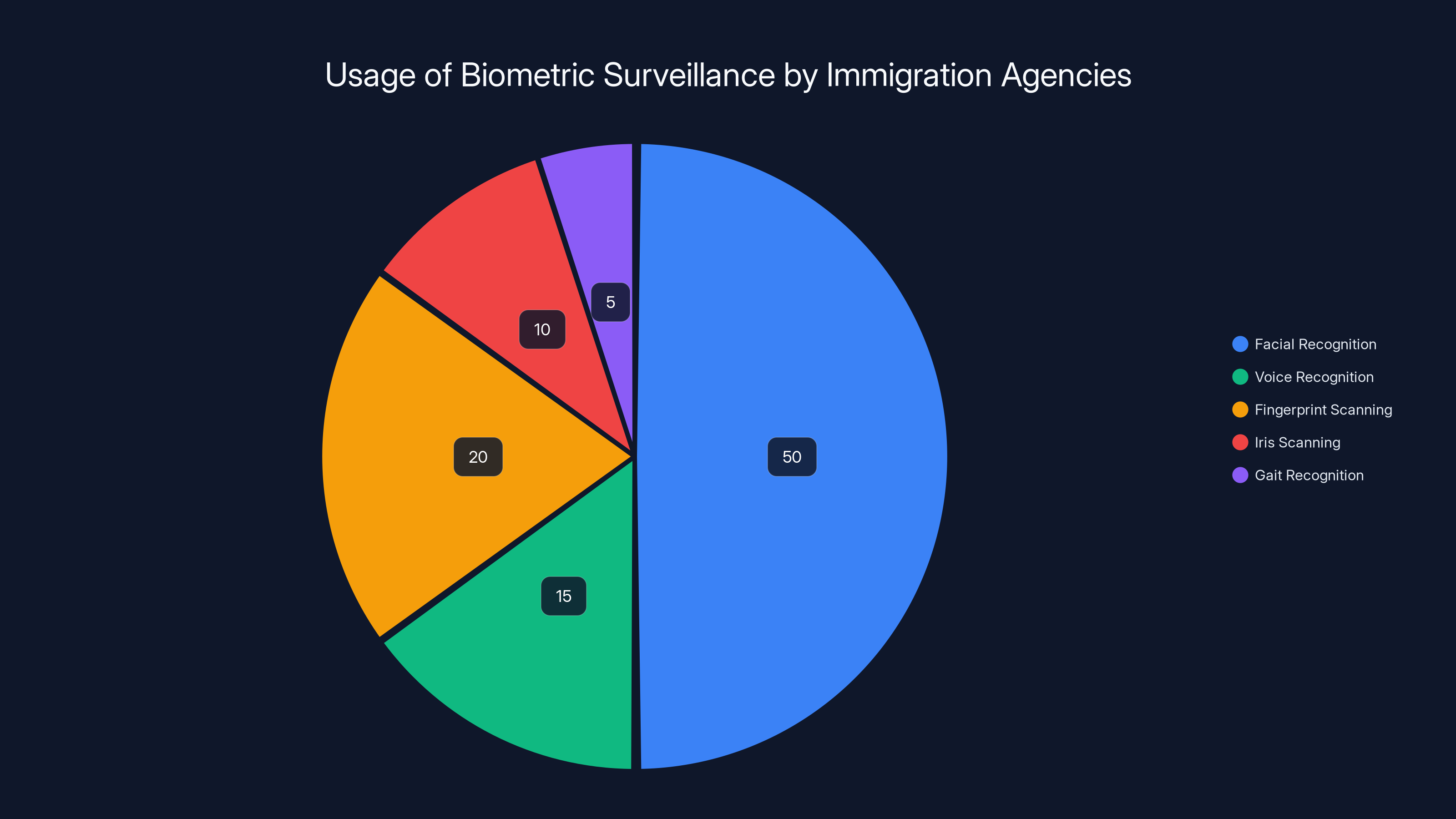

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act is a proposed federal law that would fundamentally restrict how Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection deploy surveillance technology. But it's more than just facial recognition—the bill takes aim at an entire ecosystem of biometric surveillance systems.

The core provision makes it "unlawful for any covered immigration officer to acquire, possess, access, or use in the United States" any biometric surveillance system, or information derived from such systems operated by any other entity. This means ICE and CBP officers couldn't just use their own facial recognition tools. They also couldn't access facial recognition data from state DMVs, local law enforcement databases, or other federal agencies.

That's a meaningful distinction. Currently, immigration agencies have workarounds. They can't always deploy facial recognition directly, but they can request data from partners or obtain access through informal information sharing. The bill would close those loopholes.

The legislation goes beyond facial recognition. It covers voice recognition technology, fingerprint scanning, iris scanning, and any other biometric identification system. This is important because agencies have been expanding their toolkit. Voice recognition could identify someone from recordings of phone calls or public statements. Iris scanning could work at borders or checkpoints. The bill treats all these tools equally as prohibited surveillance methods.

Perhaps most radically, the bill requires the federal government to delete all historical data collected from biometric surveillance systems. That means facial recognition databases currently maintained by ICE would have to be purged. This creates a real problem for agencies that have already built massive surveillance infrastructure.

The bill also prohibits using biometric surveillance data in court cases or investigations. Even if an agent illegally scanned someone's face, they couldn't use that information as evidence in a prosecution. This creates a powerful disincentive for abuse.

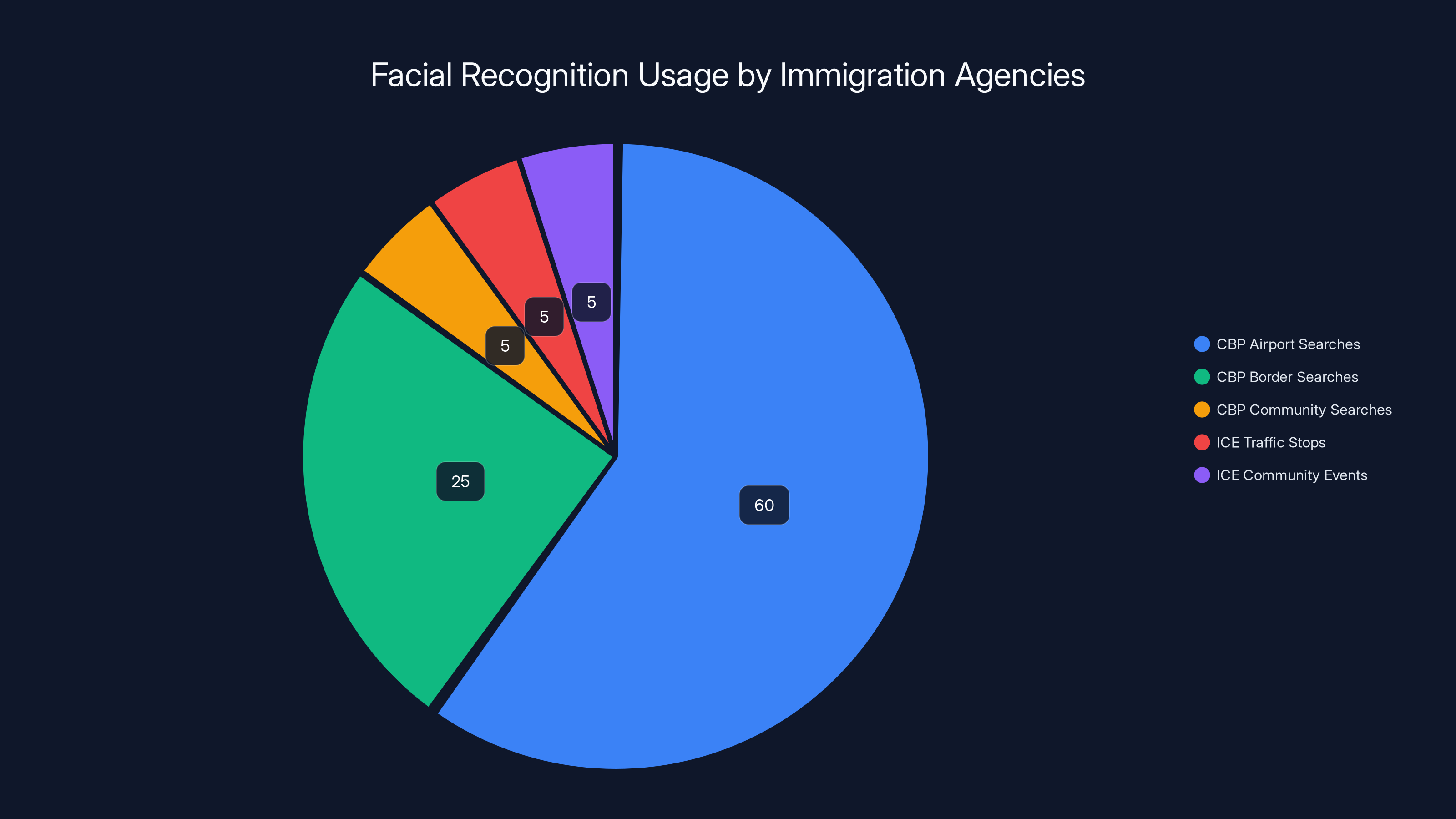

Facial recognition is the most used biometric surveillance method by immigration agencies, estimated at 50% of all biometric methods. Estimated data.

The Surveillance Arsenal: How Immigration Agencies Currently Use Facial Recognition

To understand why Senator Markey calls ICE and CBP's surveillance toolkit an "arsenal," you need to understand what these agencies are actually doing with facial recognition technology.

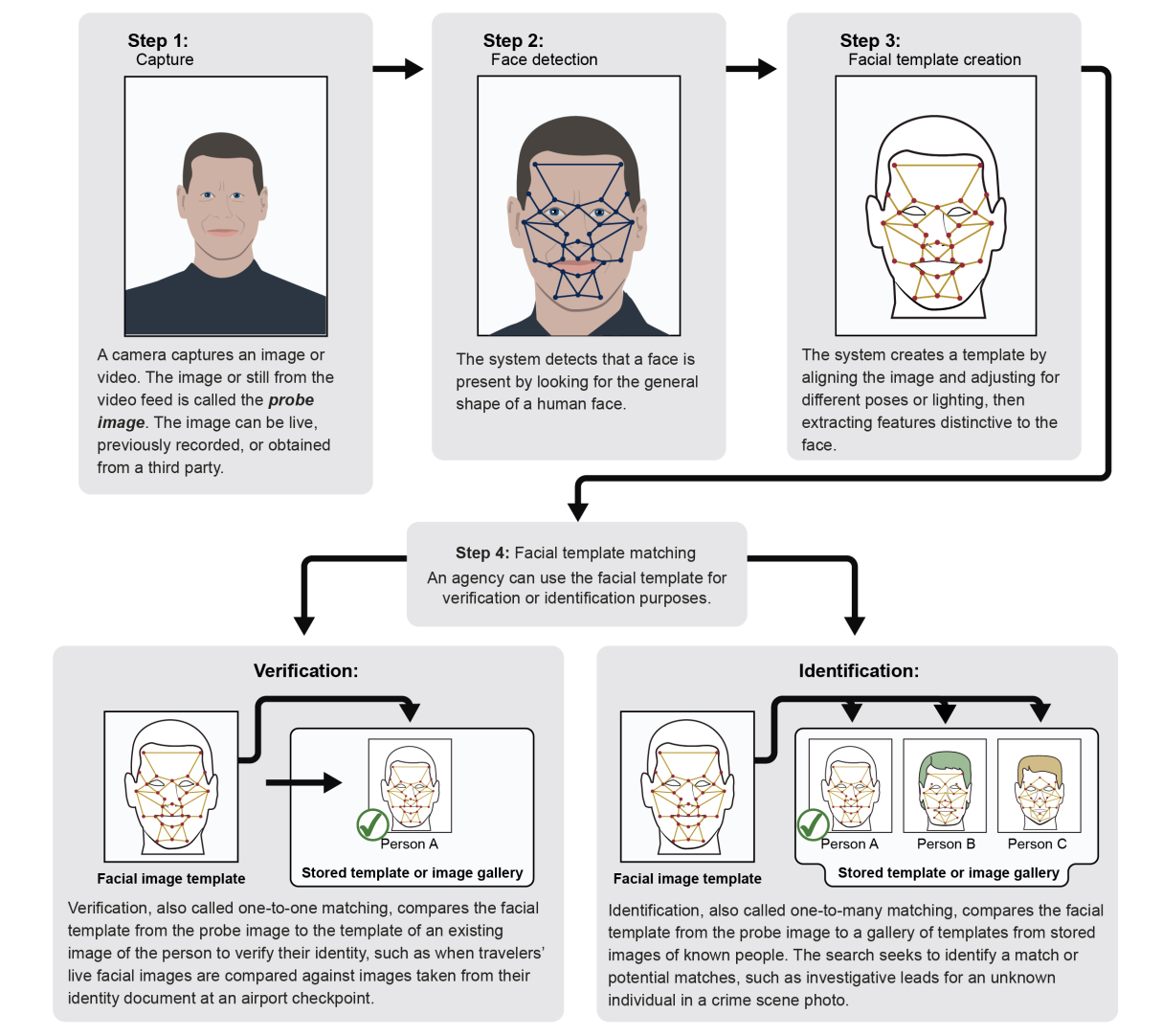

ICE has been deploying facial recognition technology for years, often in ways the public doesn't know about. The technology scans photos and videos, comparing faces against databases to identify individuals. At borders, checkpoints, and airports, facial recognition systems can verify identity in seconds. These tools integrate with broader immigration enforcement operations.

But here's where it gets concerning. The technology doesn't just work at official ports of entry. ICE has been using facial recognition against people in everyday situations: at traffic stops, at community events, in photos taken by surveillance cameras. The system works by cross-referencing against multiple databases, including driver's license photos, passport images, and mugshots.

CBP operates the largest facial recognition program among federal immigration agencies. The agency conducted facial recognition searches on approximately 234 million traveler photos in 2023 alone, according to congressional requests and agency data. Most of these searches happened at airports and border crossings. But CBP has also used the technology in community settings.

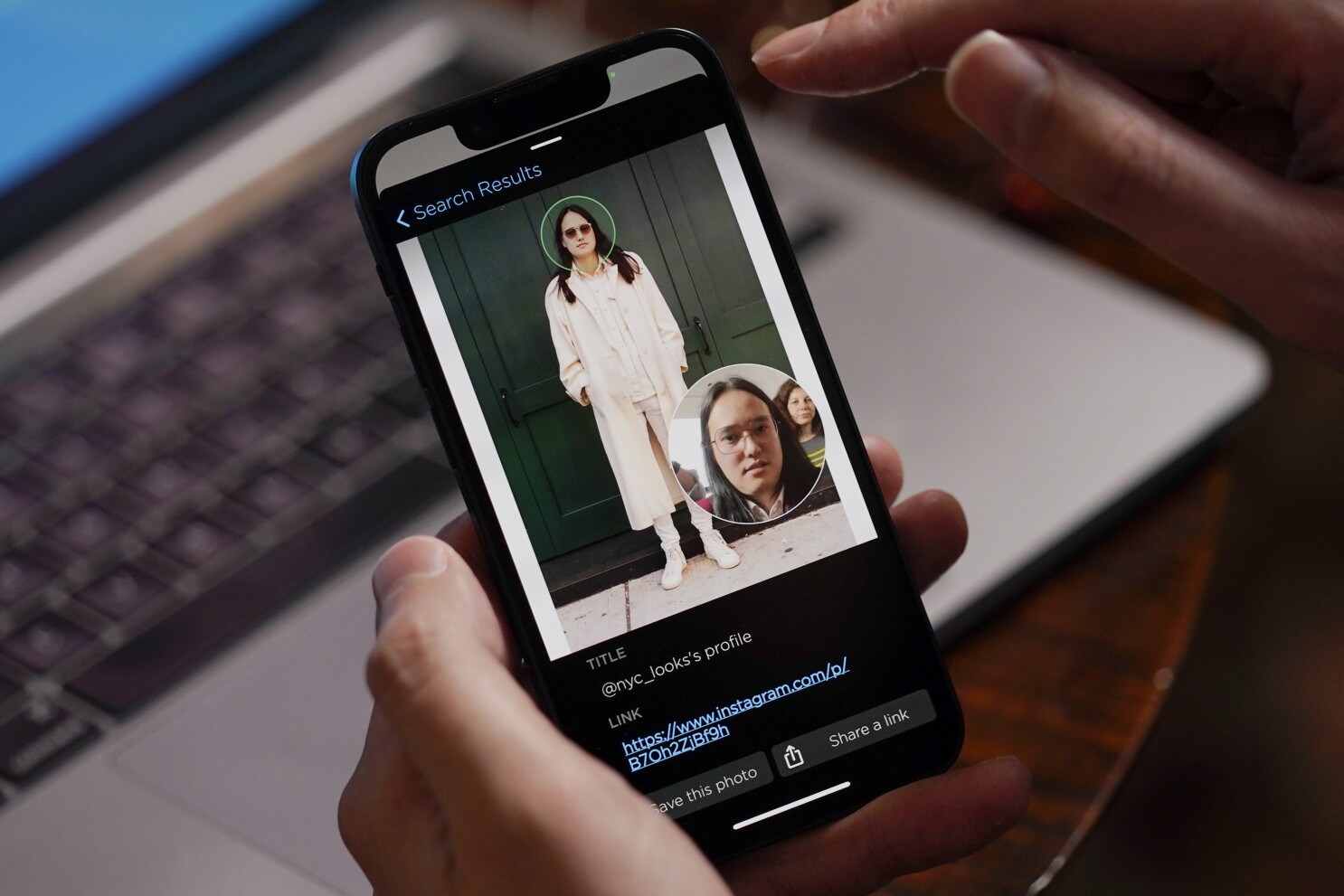

The real problem emerges when you look at how these systems have been deployed against protesters and observers. In Minnesota, an ICE observer reported that her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check privileges were revoked three days after an agent scanned her face during an immigration enforcement action. She wasn't arrested, wasn't suspected of a crime, wasn't doing anything illegal. She was observing government agents performing their duties.

In Portland, Maine, a video observer filming ICE activity had an agent tell her directly: "We have a nice little database and now you're considered a domestic terrorist." This isn't hypothetical. This is documented in police reports and communications released to journalists.

Internal agency communications make the pattern explicit. An ICE memo obtained by news outlets told agents in Minneapolis to "capture all images, license plates, identifications, and general information on hotels, agitators, protestors, etc., so we can capture it all in one consolidated form." The memo essentially instructs agents to photograph everyone present during enforcement operations, feed that data into facial recognition systems, and maintain comprehensive databases.

This represents a fundamental shift in surveillance scope. Traditional law enforcement surveillance targets suspects. Modern immigration agency surveillance casts an impossibly wide net, capturing everyone present, classifying people as threats based on their location, and maintaining permanent digital records.

The Biometric Surveillance Ecosystem: More Than Just Facial Recognition

When people hear "facial recognition," they think of cameras comparing faces against databases. That's part of it. But the broader biometric surveillance ecosystem is far more sophisticated and invasive.

Biometric surveillance encompasses multiple overlapping technologies that together create a comprehensive surveillance web. Facial recognition scans still images and video. Voice recognition identifies individuals from recordings. Fingerprint scanning captures identification from prints. Iris scanning uses eye patterns. Gait recognition analyzes how someone walks. Together, these systems create multiple layers of identification.

The problem with plural biometric systems is that they're harder to escape and easier to exploit. If you can avoid cameras, biometric systems might capture your voice. If you wear a mask or sunglasses, iris or gait recognition might work. Each technology has different blind spots. Combined, they leave almost no blind spots.

Immigration agencies have been quietly expanding their biometric toolkit. Voice recognition technology has particular potential for immigration enforcement because it could work with phone recordings, public statements, social media videos, or any audio recording. An agent could identify someone from a protest video or a phone call without that person knowing they've been identified.

Iris scanning is being deployed at some border crossings. The technology requires people to look into a scanner, but the process is quick and becoming normalized. As more border crossings adopt iris scanning, the system becomes another layer in the biometric dragnet.

Gait recognition is still emerging, but the technology is advancing rapidly. Gait recognition software can identify individuals from video surveillance footage without their knowledge or cooperation. Immigration agencies haven't deployed this widely yet, but the technology exists and continues improving.

The ecosystem creates what privacy advocates call "function creep." Systems deployed for one purpose gradually expand to cover additional purposes. Facial recognition initially deployed at airports expands to community surveillance. Voice recognition initially used for interviews expands to analyzing protest recordings. Each expansion is incremental, but together they create comprehensive surveillance.

In 2023, CBP conducted the majority of facial recognition searches at airports (60%) and border crossings (25%), while ICE utilized the technology in community settings and traffic stops (5% each). Estimated data.

Why Senators Introduced This Bill Now: The Growing Privacy Backlash

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act didn't emerge in a vacuum. It reflects years of accumulating evidence that immigration agencies are abusing surveillance tools against protesters, observers, and citizens exercising constitutional rights.

Senator Markey, who led the bill's introduction, has a track record of challenging surveillance overreach. He's the same senator who investigated Amazon's Ring surveillance partnerships with police departments, raising questions about how consumer technology integrates with law enforcement. He brings substantive skepticism to surveillance expansion.

But Markey isn't alone. The bill is cosponsored by Senators Ron Wyden, Angela Alsobrooks, and Bernie Sanders. This represents meaningful bipartisan concern about immigration agency surveillance. Wyden, in particular, has spent years investigating federal surveillance programs. His involvement signals that this isn't partisan theater—it's grounded in genuine concern about government overreach.

Representative Pramila Jayapal amplified the message in press conference statements, connecting facial recognition abuse to broader ICE and CBP actions. She framed the issue as "a very dangerous intersection of overly violent and overzealous activity from ICE and Border Patrol, and the increasing use of biometric identification systems."

The timing matters because it follows specific documented incidents of surveillance abuse. The Global Entry revocation case provided concrete evidence of facial recognition being weaponized against people exercising First Amendment rights. The "domestic terrorist" database incident showed how agencies label ordinary observers. These aren't hypothetical concerns—they're documented abuses.

Congressional Democratic leaders, including Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer and House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries, sent formal demands to Republican leadership requesting ICE reforms. Significantly, their initial demands didn't include a facial recognition ban, but they did request prohibitions on tracking databases and First Amendment activity surveillance. This suggests the conversation is evolving.

Markey went further, demanding that Acting ICE Director Todd Lyons confirm or deny the existence of a "domestic terrorists" database listing US citizens who protest immigration enforcement. The fact that this question needs asking demonstrates how opaque these agencies have become regarding their surveillance activities.

The Constitutional Questions: First Amendment and Due Process Implications

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act isn't just about privacy. It raises fundamental constitutional questions about First Amendment protection, due process, and government authority.

When immigration agents scan faces of people exercising First Amendment rights—attending protests, observing government operations, recording video—they're creating surveillance records of protected political activity. The First Amendment protects people's right to petition government and assemble peacefully without government retaliation. Facial recognition databases of protesters potentially chill that right.

Chilling effect is a legal concept that courts recognize. If people know government agents are photographing them at protests and feeding their faces into databases, some people might decide protesting isn't worth the risk. That reduction in political participation, even if no explicit punishment occurs, violates the First Amendment's protective purpose.

The due process implications are equally concerning. Due process requires government to follow fair procedures before restricting rights or liberties. When immigration agents label someone a "domestic terrorist" based on their presence at a location, without notice, without opportunity to contest the label, without judicial review, that appears to violate due process protections.

The fact that being labeled a "domestic terrorist" in an agency database can result in tangible consequences—like TSA Pre Check revocation—makes this more than a labeling problem. These aren't purely internal government records. They produce real-world harm to the people labeled.

Equalitarian and anti-discrimination arguments also apply. Facial recognition systems, particularly systems trained on biased datasets, can misidentify people at higher rates depending on race, gender, and age. When immigration agencies deploy these inherently biased systems against vulnerable populations, that exacerbates existing discrimination.

Fourth Amendment questions about unreasonable search and seizure also arise. When agents photograph people's faces without consent, without warrant, without reasonable suspicion, are they conducting searches under the Fourth Amendment? Courts have inconsistently answered this question, but facial recognition creates strong Fourth Amendment concerns.

The bill's private right of action directly addresses these constitutional concerns by allowing individuals to seek judicial relief for violations. Instead of relying on government enforcement, individuals can sue federal agents and agencies for damages.

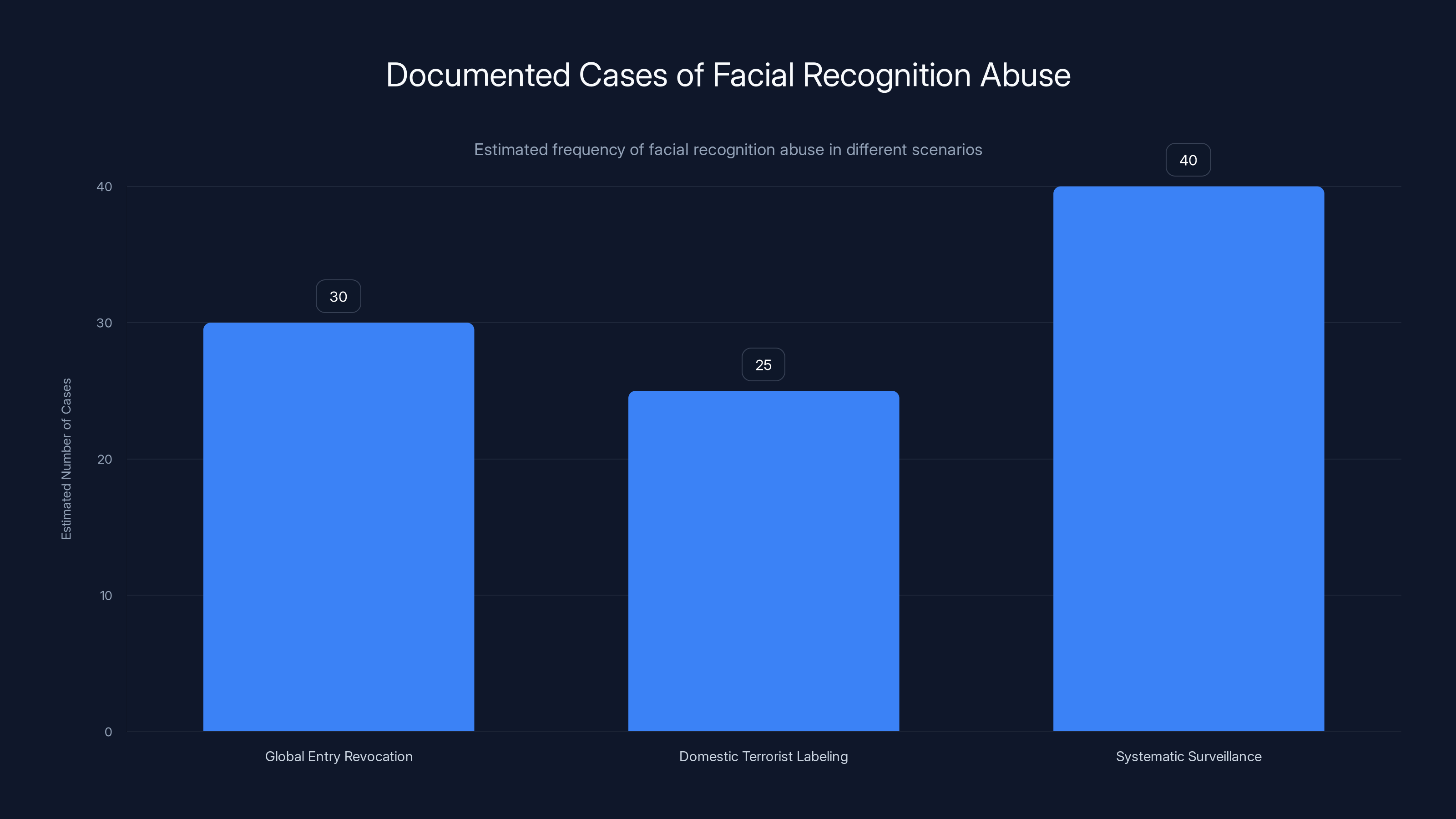

Facial recognition abuse is estimated to occur frequently, with systematic surveillance being the most common. Estimated data.

Real-World Impact: Documented Cases of Facial Recognition Abuse

Understanding the ICE Out of Our Faces Act requires looking at specific documented cases of how immigration agencies have abused facial recognition technology.

The Minnesota Global Entry Case provides the clearest example. An observer of ICE enforcement activity had her face photographed by agents during the enforcement operation. Days later, her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check privileges were revoked. These are significant travel conveniences that require background checks and substantial fees to obtain. Having them revoked without explanation or opportunity to contest the decision represents tangible harm. The observer filed a legal challenge, arguing the face scanning and credential revocation violated her rights.

The Portland "Domestic Terrorist" Incident illustrates how agencies label people based on presence alone. A masked agent explicitly told an observer recording video that she was now in "a nice little database" and "considered a domestic terrorist." This wasn't an arrest or formal designation. It was an agent informally telling someone she'd been categorized as a threat because she filmed government operations. The incident appeared in police reports and was later disclosed to journalists.

The Minneapolis Memo Incident revealed systematic instructions to photograph everyone at enforcement operations. An internal ICE memo instructed agents to "capture all images, license plates, identifications, and general information on hotels, agitators, protestors, etc., so we can capture it all in one consolidated form." The memo shows this isn't incidental surveillance—it's systematic intelligence gathering on everyone present.

These cases matter because they demonstrate that concerns about facial recognition abuse aren't theoretical. They're happening repeatedly across different geographic areas and different operational contexts. When similar incidents occur in Minnesota, Maine, and elsewhere, you're not looking at isolated bad actors. You're looking at systematic practice.

The incidents also show an escalation pattern. Initial facial recognition use at borders expanded to community enforcement operations. Initial use in enforcement expanded to surveillance of observers and protesters. Initial use for identification expanded to maintenance of threat databases. Each step seemed incremental, but together they created comprehensive surveillance of people exercising constitutional rights.

Political Reality: Why This Bill Faces a Hard Road

Senator Markey's bill addresses genuine concerns about immigration agency surveillance. But here's the hard reality: the bill faces virtually zero chance of becoming law in the current political environment.

Republicans control both chambers of Congress. Republicans have shown strong support for expanded immigration enforcement authority and have been skeptical of restrictions on surveillance tools. While some Republicans have expressed general concerns about surveillance in other contexts, few have prioritized limiting immigration agency tools.

The Trump administration—relevant because the Senate has included immigration hardliners in cabinet positions—has consistently advocated for expanded immigration enforcement authority and more aggressive deportation operations. Limiting facial recognition and biometric surveillance directly contradicts this enforcement-first approach.

Even within the Democratic caucus, not all members have rallied behind the bill. House Democratic leaders Schumer and Jeffries sent reform demands to Republicans that notably didn't include a facial recognition ban. This suggests party leadership isn't necessarily unified behind this specific approach, even though individual senators like Markey are pushing hard.

The bill does, however, signal something important: growing congressional concern about immigration agency surveillance practices. When multiple senators and representatives speak publicly about surveillance abuse and propose legislative restrictions, that creates political space for future action. If control of Congress changes, or if public pressure builds, the bill provides a legislative framework ready to implement.

The real power of the bill might not be in its current passage prospects, but in what it reveals about emerging consensus. Senators from both parties, elected officials across the spectrum, and civil liberties advocates agree that immigration agency surveillance has exceeded appropriate bounds. That consensus matters politically.

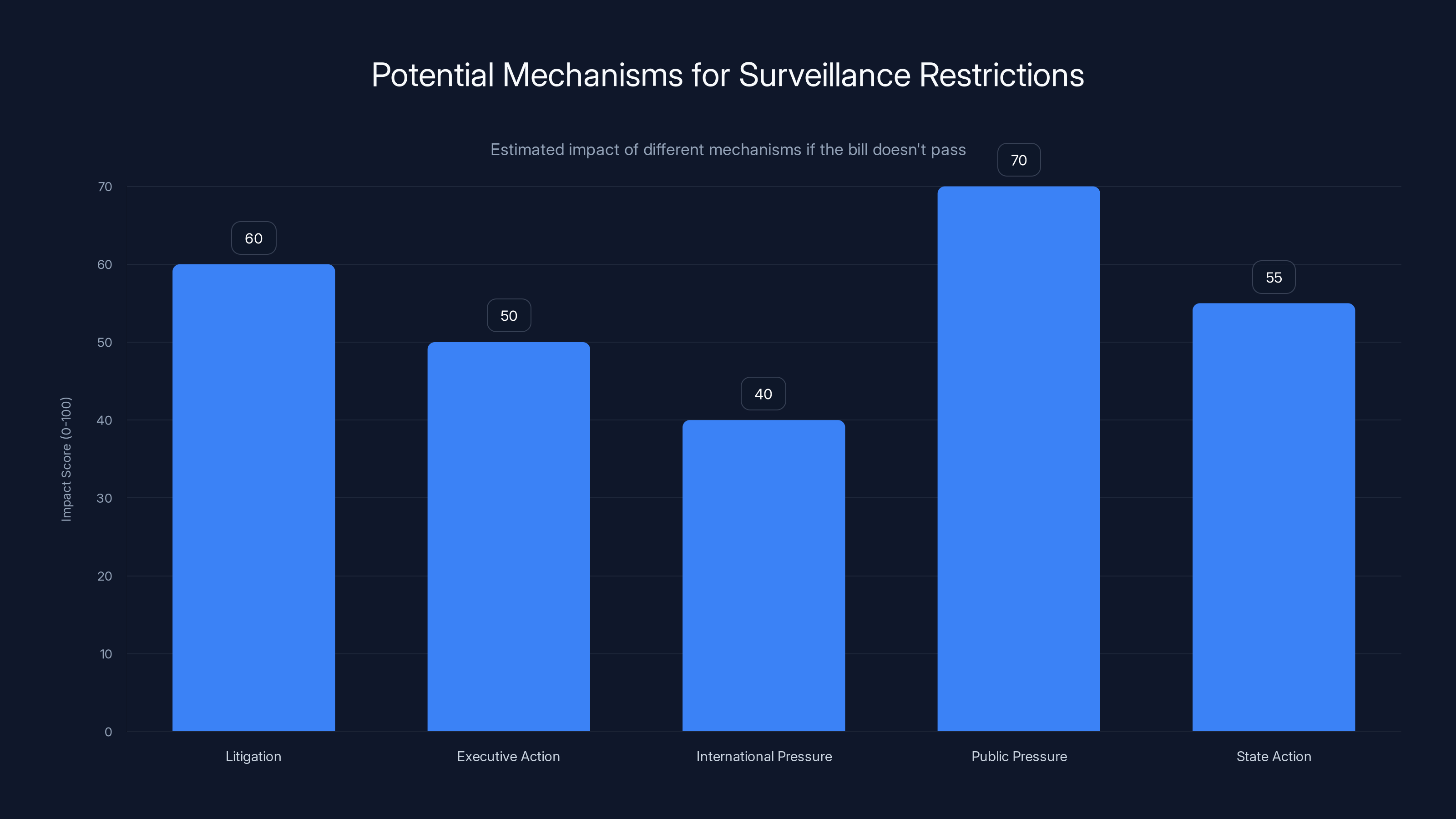

Public pressure and litigation are estimated to have the highest potential impact on restricting surveillance if the bill doesn't pass. Estimated data.

Comparing Approaches: How This Bill Differs From Other Surveillance Limitations

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act takes a particular legislative approach to limiting surveillance, and understanding how it differs from other approaches helps explain its significance.

Some surveillance restrictions use narrow targeting, limiting specific tools in specific contexts. For example, a law might prohibit facial recognition at airports but allow it at borders. This approach is incremental and less disruptive to law enforcement operations, but it leaves major loopholes.

Other restrictions use transparency requirements, mandating that agencies disclose their surveillance practices and submit to oversight. This approach assumes informed oversight can correct abuses, but it requires functioning oversight mechanisms and can be circumvented through classified operations.

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act uses blanket prohibition. It says no facial recognition, no voice recognition, no biometric surveillance by these agencies, period. No exceptions, no special circumstances, no narrow contexts where it's allowed. This is the most aggressive legislative approach.

Blanket prohibition has tradeoffs. It's easier to enforce because there's no ambiguity about what's prohibited. It prevents incremental function creep because the tool is simply unavailable. But it also potentially prevents legitimate uses, like identifying actual criminals or verifying traveler identity.

Comparable bills addressing other agencies have used different approaches. Police surveillance bills often use transparency and oversight rather than blanket prohibition. This reflects different political dynamics and different baseline acceptance of police authority.

The fact that immigration agencies specifically trigger such an aggressive legislative response says something about public concern regarding these agencies. When Congress moves toward blanket prohibition, that reflects judgment that normal oversight isn't working.

The private right of action component also distinguishes this bill. Some surveillance legislation relies on government enforcement through federal agencies or inspector general reviews. This bill lets individuals sue directly, creating enforcement decentralized across countless potential litigants. That's potentially more effective but also more costly to defendants.

Data Deletion Requirements: The Radical Dimension

One provision of the ICE Out of Our Faces Act deserves special attention: the requirement that all historical data collected from biometric surveillance systems must be deleted.

This isn't a modest restriction on future collection. It's a mandate to destroy existing databases. That's genuinely radical in government surveillance context, where data collection is essentially irreversible once it occurs.

ICE and CBP have been maintaining facial recognition databases for years. These databases contain millions of faces. Deleting them would mean destroying institutional assets that agencies have invested in building.

But that's actually the point. The bill treats these databases as illegally collected evidence that should be destroyed. By that logic, even though the collection might have been legal when it occurred, the data shouldn't be stored or maintained because the tool itself is prohibited.

Data deletion creates several practical problems for agencies. Agents become accustomed to relying on these tools for investigative leads. Deleting the data disrupts operational practices that have been built around database access. The deletion also eliminates evidence that might be relevant to ongoing investigations or prosecutions.

But data deletion also creates powerful protections for individuals. If historical facial recognition data is deleted, then ICE agents can't access years of historical scans to track individuals over time. They can't maintain persistent surveillance records. Each enforcement operation starts fresh without the accumulated facial recognition history.

The data deletion requirement reflects a judgment that some tools are so problematic that even their existing use creates unacceptable surveillance infrastructure. Rather than merely restricting future use, the bill requires destroying the problematic infrastructure.

This approach has precedent in other privacy contexts. When certain recording practices have been deemed impermissible, courts have occasionally ordered destruction of recorded material. But applying that logic comprehensively to federal biometric surveillance databases would be unprecedented.

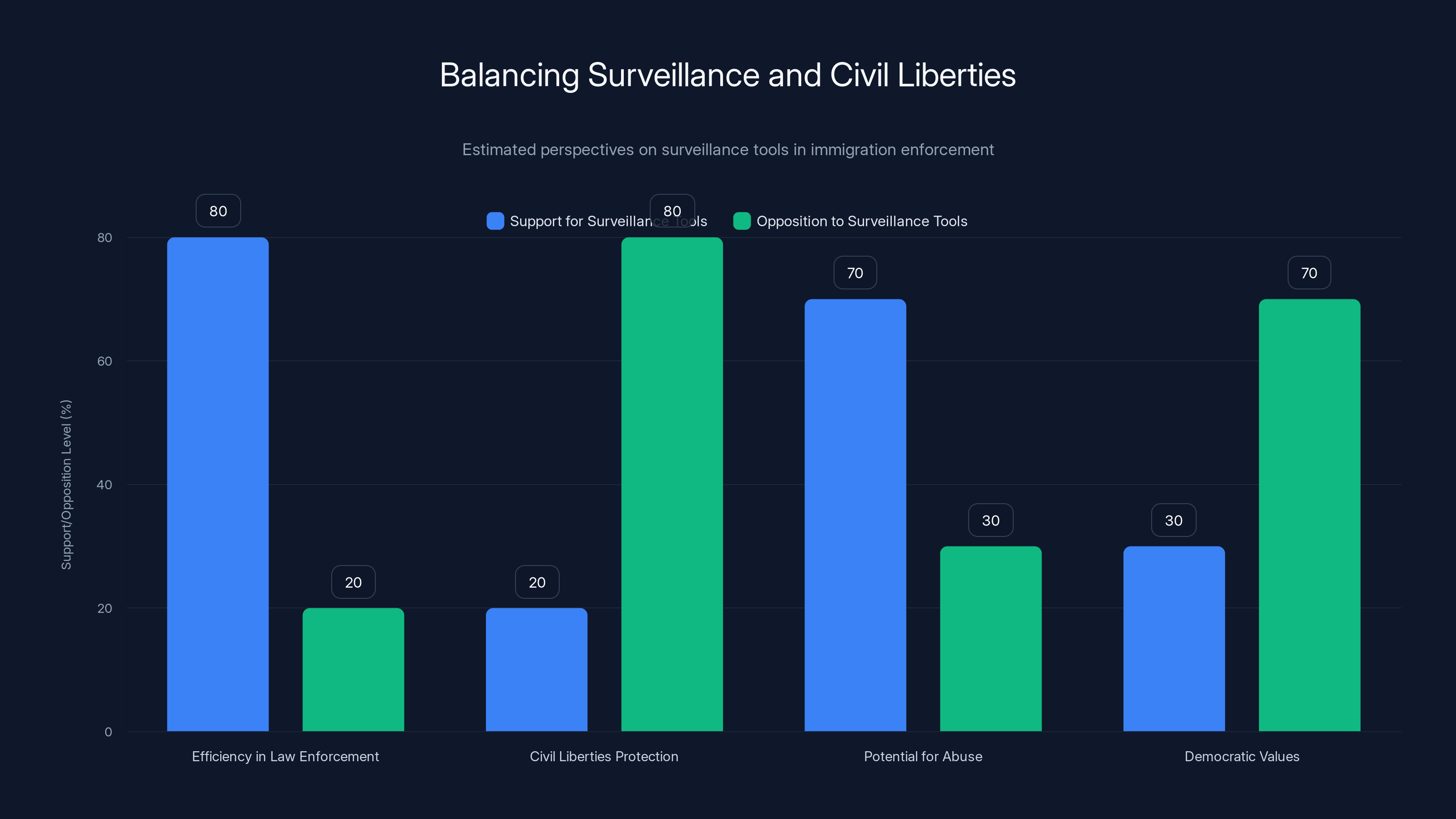

Estimated data shows a stark division: supporters emphasize enforcement efficiency, while opponents stress civil liberties and potential for abuse.

The Enforcement Question: How Would Violations Be Remedied?

A law is only as strong as its enforcement mechanisms. The ICE Out of Our Faces Act includes specific provisions designed to ensure meaningful enforcement.

The private right of action allows any individual whose rights are violated to sue the federal government for financial damages. This is powerful because it doesn't depend on government enforcement. If an ICE agent illegally uses facial recognition, the person whose face was scanned can sue directly for damages.

Private rights of action create several incentives. First, they create direct financial consequences for violations. Government agencies must account for damage awards in their budgets. Repeated violations become expensive, creating institutional pressure to comply.

Second, private lawsuits can establish legal precedent. A successful lawsuit against ICE establishes that the facial recognition use violated law, creating pressure on other agencies and other agents to comply.

Third, private litigation creates deterrence. When agents know they can be personally sued for damages, they become more cautious about pushing surveillance boundaries.

The bill also authorizes state attorneys general to bring suits on behalf of state residents. This creates another enforcement mechanism. State officials have political incentives to protect residents' rights. If federal agencies are violating state residents' privacy, state attorneys general can sue on their behalf.

However, enforcement mechanisms have limits. Getting actual damages awarded can be difficult. Federal government usually has robust legal defenses. Proving that facial recognition use caused specific damages requires showing concrete harm. If someone's Global Entry was revoked but they can demonstrate government liability, they might recover costs, but quantifying the harm can be complex.

Also, government agencies have qualified immunity in many circumstances. This legal doctrine shields government officials from personal liability except in clearly established violation of rights. The bill would need to specify how it interacts with qualified immunity, or courts might interpret it narrowly.

Despite these limitations, private rights of action and state attorney general authority create meaningful enforcement possibilities. They decentralize enforcement rather than relying solely on internal agency mechanisms.

Broader Context: Immigration Enforcement and Technology

Understanding the ICE Out of Our Faces Act requires understanding how it fits into broader immigration enforcement and technology adoption patterns.

Immigration agencies have been early adopters of surveillance technology. When new surveillance tools become available, ICE and CBP are typically among the first federal agencies to deploy them. This reflects both the unique investigative challenges immigration enforcement faces and the political reality that immigration is treated as a security issue.

Biometric technology particularly appeals to immigration agencies because immigration enforcement fundamentally involves identifying who people are and whether they're authorized to be in the country. Facial recognition directly addresses this identification challenge.

But immigration agencies have also deployed surveillance more aggressively than other federal agencies. While the FBI uses facial recognition primarily for criminal investigation, ICE uses it for civil immigration enforcement. The distinction matters because civil enforcement has lower due process protections than criminal enforcement.

The agencies have also integrated surveillance into broader enforcement operations in ways that other agencies don't. When ICE conducts a worksite raid, agents photograph everyone present. This surveillance creates collateral impact on people not suspected of immigration violations: coworkers, family members, and bystanders.

Immigration enforcement has also become increasingly militarized in rhetorical and operational terms. Referring to immigrants as invaders, characterizing immigration as invasion, and deploying enforcement operations with military tactics all create context in which extensive surveillance seems justified as security response.

Technology companies have largely accommodated these enforcement demands. Surveillance technology vendors compete for government contracts. Immigration agency customers are desirable because enforcement agencies have substantial budgets and are willing to pay for advanced technology. This creates vendor incentives to develop surveillance capabilities specifically for immigration enforcement.

The broader technology policy context also matters. Unlike European countries with stronger data protection regulations, the United States has relatively permissive policies regarding government surveillance. This creates regulatory space for immigration agencies to develop expansive surveillance programs without the legal constraints that would apply elsewhere.

Legislative Alternatives: What Else Could Address This Problem?

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act represents one approach to immigration agency surveillance concerns. But alternative legislative approaches exist, each with different tradeoffs.

Transparency Requirements would mandate that ICE and CBP disclose their surveillance tools, how they're deployed, success rates, false positive rates, and how data is stored. This approach assumes informed oversight can correct problems. The advantage is that transparency doesn't prohibit tools—it just requires disclosure and oversight. The disadvantage is that classified operations could evade transparency, and oversight has historically been ineffective at constraining agency action.

Narrow Use Restrictions would allow facial recognition but only in specific contexts: border crossings, international airports, known criminal databases. This approach allows beneficial uses while restricting problematic uses. The disadvantage is that it requires bureaucratic line-drawing that's difficult to enforce. What counts as a "known criminal database"? When is something a "border crossing" versus a "community area"?

Accuracy Requirements would mandate that facial recognition systems meet specific accuracy thresholds before deployment. The logic is that more accurate systems cause fewer false identifications and fewer unjustified harms. But accuracy requirements don't address the fundamental surveillance problem—accurate mass surveillance is still mass surveillance.

Warrant Requirements would require agents to get warrants before using facial recognition. This would apply traditional Fourth Amendment protections to biometric surveillance. The advantage is that it would create judicial oversight. The disadvantage is that warrant processes can be streamlined, and judges often approve law enforcement requests.

Audit and Liability Requirements would require agencies to conduct regular audits of facial recognition use and establish that officials responsible for unlawful use face accountability. This approach creates incentives for compliance through potential liability. But government officials have qualified immunity, limiting personal liability in many circumstances.

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act's blanket prohibition approach is the most aggressive of these options. It says the problem is so fundamental that some tools shouldn't exist for these agencies at all. This reflects judgment that narrower restrictions don't adequately address the concerns.

Looking Forward: What Happens If the Bill Doesn't Pass?

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act faces difficult political odds. So what happens if it doesn't pass? What's the realistic trajectory for immigration agency surveillance policy?

Historically, surveillance restrictions happen through multiple mechanisms: legislation, litigation, executive action, and public pressure. If legislation fails, other mechanisms might eventually produce restrictions.

Litigation could produce restrictions even without legislation. If civil rights organizations bring suit arguing that facial recognition use violates First Amendment, Fourth Amendment, or due process rights, courts might establish legal restrictions. This would be slower and more piecemeal than legislation, but could eventually constrain agency action.

Executive Action could restrict surveillance without legislation. A future president could direct ICE and CBP to limit facial recognition use. This would be less permanent than legislation because a subsequent administration could reverse the order, but it would demonstrate that restriction is administratively possible.

International Pressure could influence US policy. If other democracies restrict immigration agency surveillance and publicize the reasoning, that could create diplomatic and reputational pressure on the US to follow suit.

Public Pressure could shift political dynamics. If documented cases of surveillance abuse continue and generate public outcry, eventually political pressure could force action even if current Congress doesn't cooperate.

State Action could lead the way. Individual states could restrict state cooperation with federal facial recognition operations. If states refuse to share driver's license photos or refuse to allow immigration agents to conduct facial recognition in state facilities, federal agencies lose access to critical data.

Most likely, surveillance restrictions will eventually happen through some combination of these mechanisms rather than through a single legislative action. The ICE Out of Our Faces Act establishes a legislative framework that could become law if political circumstances change. In the meantime, litigation and public pressure will continue chipping away at surveillance authority.

Why This Matters Beyond Immigration: The Precedent Question

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act has significance beyond immigration policy. It establishes important precedents about what surveillance restrictions are possible at the federal level.

If Congress successfully restricts immigration agency facial recognition, that creates a template for restricting surveillance by other agencies: FBI, DEA, ATF, local police departments. If government can prohibit facial recognition for immigration enforcement, the same logic could apply to criminal law enforcement.

Conversely, if immigration agency surveillance continues expanding unchecked, that establishes a precedent that federal agencies can deploy biometric surveillance broadly without legislative restriction. That precedent makes it harder to later impose restrictions on other agencies.

Surveillance is a ratcheting mechanism. It's much easier to expand surveillance than to restrict it. Once surveillance infrastructure is built, it's normalized. Once agencies become dependent on surveillance tools, they resist giving them up. The longer facial recognition operates, the more institutional dependence develops.

Immigration agencies are essentially laboratories for federal surveillance. Policies developed there often spread to other agencies. If facial recognition works without major restrictions in immigration enforcement, law enforcement agencies argue they should have access to the same tools. The precedent ripples outward.

This is why the ICE Out of Our Faces Act represents something larger than immigration policy. It's a test case for whether democratic societies can successfully restrict government surveillance or whether surveillance just continues expanding until it encompasses all government operations.

International Comparison: How Other Democracies Handle Immigration Surveillance

The United States isn't the only democracy deploying surveillance technology in immigration enforcement. But other democracies have approached surveillance restrictions differently.

The European Union has been more restrictive. EU data protection regulations, particularly the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), impose strict requirements on government surveillance. GDPR restricts automated decision-making, requires transparency, and gives individuals significant rights to know when they're being surveilled and what data is held about them. EU immigration agencies must operate within these constraints.

France and Germany have explored facial recognition in immigration enforcement but faced substantial public opposition and legal challenges. When facial recognition was deployed at borders, civil rights groups challenged it through courts, arguing it violated privacy rights and data protection principles. These legal challenges created pressure to restrict surveillance.

Canada permits facial recognition but with more oversight and transparency requirements than the US. Canadian authorities must justify facial recognition use and report publicly on deployment and accuracy. This transparency creates accountability that US agencies lack.

Australia deployed facial recognition in immigration enforcement more aggressively than many democracies, but eventually faced public backlash. Privacy advocates and opposition politicians challenged the practice, creating political pressure for restrictions.

The general pattern is that democracies with stronger privacy protections or more powerful oversight bodies tend to constrain government surveillance more effectively. The US, with limited statutory privacy protection and weak oversight of immigration agencies, has permitted more expansive surveillance.

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act would move US policy closer to European approaches that prioritize privacy protection and restrict surveillance that affects large populations.

The Civil Liberties Alliance: Who's Supporting This?

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act brings together an unusual coalition of supporters, reflecting that facial recognition concerns cross traditional political lines.

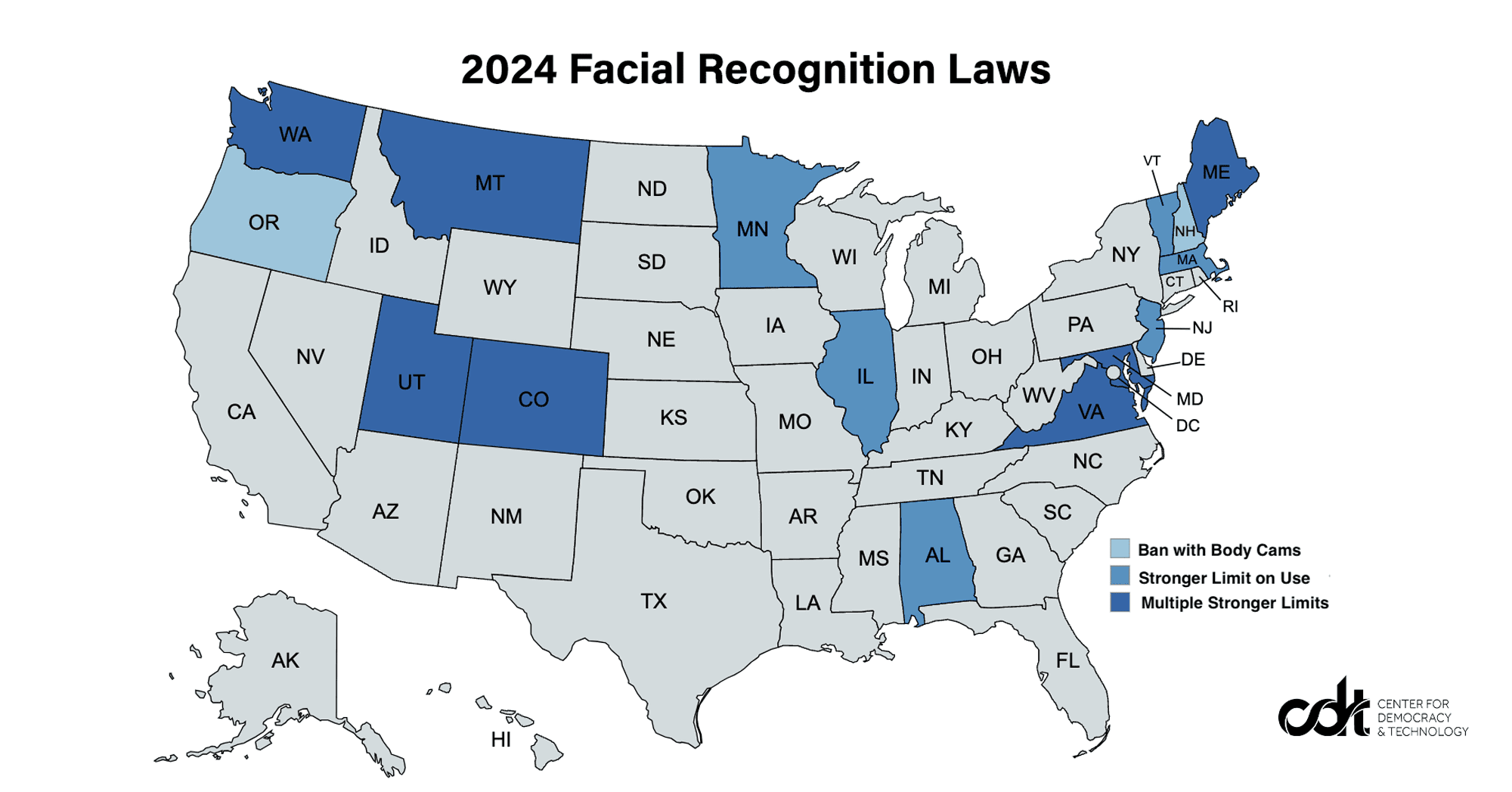

Civil Rights Organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union, Center for Democracy and Technology, and various immigrant rights organizations support the bill. These groups view facial recognition as fundamentally threatening to their constituents and to civil rights generally.

Privacy Advocates from across the political spectrum support restrictions on government facial recognition. Even libertarian groups that don't typically align with progressive Democrats on other issues have joined in opposing government surveillance expansion.

Faith Communities have expressed concern about surveillance that chills First Amendment rights. Religious organizations that assist immigrants or oppose immigration enforcement have particular concerns about surveillance of their communities.

Technology Companies have mixed positions. Some technology companies support facial recognition restrictions because they're concerned about government procurement of surveillance tools and the precedent that creates. Others are neutral or mildly supportive if restrictions on government surveillance don't affect private sector surveillance.

Immigrant Rights Groups obviously support restrictions that limit immigration enforcement tools. These groups view facial recognition as disproportionately affecting their communities and enabling aggressive enforcement operations.

Immigration Attorneys support the bill because it would limit tools used against their clients. Lawyers challenging immigration enforcement rely on fourth and fifth amendment arguments, and facial recognition restrictions would support those arguments.

This coalition doesn't typically align on policy issues. It reflects that facial recognition concerns transcend traditional policy divides. When civil rights organizations, libertarians, faith communities, and technology companies agree that something is problematic, that suggests the problem is genuinely significant.

Potential Compromises: What Could Build Broader Support?

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act takes an aggressive stance: no facial recognition for immigration agencies, period. But if political circumstances change, compromise alternatives might be more legislatively viable.

Narrower Scope Compromise would prohibit facial recognition against protesters and observers but allow it at borders and in criminal investigations. This would protect First Amendment activities while allowing some enforcement tool use.

Transparency and Oversight Compromise would allow facial recognition but require extensive reporting on deployment, accuracy, results, false positives, and how data is used. This would preserve tool availability while creating accountability.

Data Retention Limit Compromise would allow facial recognition but require deletion of data after a specific period (30 days, 90 days, one year). This would prevent the persistent surveillance databases that currently concern advocates.

Accuracy Standard Compromise would allow facial recognition only systems meeting specific accuracy thresholds. This would eliminate the most error-prone systems while allowing accurate tools.

Warrant Requirement Compromise would require agents to obtain warrants before using facial recognition. This would create judicial oversight without completely prohibiting the tool.

Each compromise trades some level of protection for broader political viability. An aggressive ban gets maximum protection but minimal chance of passage. Narrow compromises might pass but provide minimal protection.

The optimal strategy might be proposing the aggressive bill now, then negotiating toward compromise if political circumstances change. That allows advocates to stake out a strong position rather than starting from a compromised position.

Conclusion: The Surveillance Choice America Faces

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act represents more than immigration policy. It crystallizes a fundamental choice about what kind of surveillance state America should permit.

On one side, immigration agencies argue they need surveillance tools to enforce immigration law effectively. Facial recognition makes investigations more efficient, helps identify criminals, and helps verify traveler identity. From this perspective, restricting tools constrains necessary enforcement capability.

On the other side, civil liberties advocates argue that surveillance has expanded without meaningful oversight, that tools are being weaponized against people exercising constitutional rights, and that comprehensive surveillance creates a police state that contradicts democratic values. From this perspective, facial recognition represents a line that should not be crossed.

Both perspectives have merit. Immigration enforcement is a legitimate government function. Protecting civil liberties and preventing surveillance overreach are also legitimate. The question is how to balance these concerns.

The documented abuse cases—Global Entry revocation for observing enforcement operations, "domestic terrorist" databases for protesters, systematic surveillance of everyone at enforcement operations—demonstrate that current safeguards aren't working. Agencies have developed surveillance capabilities beyond what existing law contemplated.

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act proposes a solution: remove the capability entirely. Make facial recognition unavailable for immigration enforcement. If you can't use the tool, you can't abuse it.

This is a stark choice. It eliminates potential beneficial uses (identifying actual criminals, verifying traveler identity) to prevent potential abuses (comprehensive surveillance of protesters and observers).

But that's sometimes what democratic governance requires. Some tools create dangers that outweigh their benefits. Some capabilities should simply be unavailable to government.

Whether Congress eventually agrees with that judgment remains to be seen. But the introduction of the ICE Out of Our Faces Act signals that surveillance concerns are reaching a critical point. When senators across the political spectrum recognize that immigration agencies have "built an arsenal of surveillance technologies," when documented abuse cases keep emerging, when civil liberties organizations, technology companies, and faith communities join in opposing the tools, that creates political momentum that's difficult to ignore long-term.

The bill may not pass this Congress. But it establishes a template for future action. It creates legislative language that could become law if political circumstances change. Most importantly, it names the problem explicitly: immigration agencies are deploying surveillance too aggressively, and restrictions are necessary.

In democracies, those kinds of statements matter. They establish that the surveillance practices are contested, that restrictions are possible, that expansion is not inevitable. They create political space for eventual change.

FAQ

What exactly does the ICE Out of Our Faces Act prohibit?

The bill would make it unlawful for ICE and CBP officers to acquire, possess, access, or use any biometric surveillance system, including facial recognition, voice recognition, fingerprint scanning, iris scanning, and related technologies. It also prohibits using data derived from such systems operated by other entities. All historical biometric surveillance data would have to be deleted, and biometric information couldn't be used in court cases or investigations. Individuals would have the right to sue for damages, and state attorneys general could bring suits on behalf of residents.

How are immigration agencies currently using facial recognition?

Immigration agencies use facial recognition at borders, airports, and in community enforcement operations. CBP conducted facial recognition searches on approximately 234 million traveler photos in 2023 alone. Agents also use facial recognition against protesters and observers at immigration enforcement operations, often creating databases that label people as threats. Documented cases show agents using facial recognition against people exercising First Amendment rights, leading to consequences like revocation of travel privileges or being labeled as "domestic terrorists" without notice or opportunity to contest the designation.

What's the difference between facial recognition and broader biometric surveillance?

Facial recognition specifically scans faces in photos or video. Biometric surveillance encompasses multiple technologies including voice recognition (identifying people from audio recordings), fingerprint scanning, iris scanning, and gait recognition (identifying people by how they walk). Together, these create overlapping surveillance systems. The ICE Out of Our Faces Act restricts the entire biometric surveillance ecosystem, not just facial recognition alone, to prevent agencies from simply switching to alternative biometric tools.

Why does the bill require deletion of historical facial recognition data?

The bill treats existing facial recognition databases as problematic surveillance infrastructure that should be destroyed rather than merely restricted from future use. Deleting historical data prevents agencies from accessing years of accumulated facial recognition records to track individuals over time. This eliminates the persistent surveillance infrastructure while allowing future collection to be prohibited. Data deletion is more aggressive than typical surveillance restrictions but creates stronger privacy protection.

What is a private right of action and why does it matter?

A private right of action allows individuals whose rights are violated to sue the federal government directly for financial damages without waiting for government enforcement. This is powerful because it doesn't depend on agencies policing themselves. If an ICE agent illegally uses facial recognition, the person scanned can sue directly. Private lawsuits create financial consequences, establish legal precedent, and deter future violations. This is often more effective than relying on internal government compliance mechanisms.

What are the political prospects for this bill becoming law?

The bill faces very difficult political odds. Republicans control Congress and have generally supported expanded immigration enforcement authority and been skeptical of surveillance restrictions. The Trump administration and other administration officials have advocated for expanded immigration enforcement capabilities. However, the bill's introduction signals growing bipartisan concern about immigration agency surveillance. While it likely won't pass in the current Congress, it establishes legislative language and creates political space for future action if political circumstances change.

How does this bill compare to restrictions on other federal agencies' surveillance?

The ICE Out of Our Faces Act takes a more aggressive approach than most surveillance restrictions. It uses blanket prohibition rather than narrow targeting or transparency requirements. Most police surveillance legislation relies on transparency and oversight rather than complete prohibition. The fact that immigration agencies specifically trigger aggressive restrictions reflects public concern that these agencies have more power and less accountability than traditional law enforcement. The bill represents judgment that normal oversight mechanisms aren't sufficient to constrain immigration agency surveillance.

What real-world cases demonstrate why this bill is necessary?

Multiple documented cases show immigration agents using facial recognition against people exercising constitutional rights. In Minnesota, an observer of ICE operations had her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check revoked three days after an agent scanned her face—without any explanation, notice, or opportunity to contest. In Portland, Maine, an agent told a video observer she was now in "a nice little database" and "considered a domestic terrorist" simply for recording government operations. An internal ICE memo instructed agents to photograph everyone at enforcement operations and maintain consolidated databases. These aren't theoretical concerns—they're documented systematic abuse.

Key Takeaways

- The ICE Out of Our Faces Act proposes blanket prohibition on facial recognition and biometric surveillance by immigration agencies, representing the most aggressive legislative surveillance restriction approach

- Documented cases show ICE agents using facial recognition against protesters and observers, labeling them as "domestic terrorists" and revoking travel privileges without notice or opportunity to contest

- CBP conducted 234 million facial recognition searches in 2023 alone, demonstrating the massive scale of current surveillance infrastructure

- The bill includes private right of action allowing individuals to sue for damages and authorization for state attorneys general to bring suits, creating decentralized enforcement mechanisms

- While unlikely to pass in the current Republican-controlled Congress, the bill establishes legislative template and signals growing bipartisan concern about immigration agency surveillance overreach

Related Articles

- ICE Domestic Terrorists Database: The First Amendment Crisis [2025]

- Switzerland's Data Retention Law: Privacy Crisis [2025]

- Inside Federal Immigration Enforcement: Agent Concerns & Operational Reality [2025]

- ExpressMailGuard: AI-Powered Email Aliases & Spam Protection [2025]

- iPhone Lockdown Mode Explained: How Apple's Ultimate Security Works [2025]

- Surfshark VPN Deal: 87% Off Two-Year Plans [2025]

![ICE Out of Our Faces Act: Facial Recognition Ban Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-out-of-our-faces-act-facial-recognition-ban-explained-20/image-1-1770325676433.jpg)