Introduction: Understanding ICE's Expanding Regional Detention Strategy

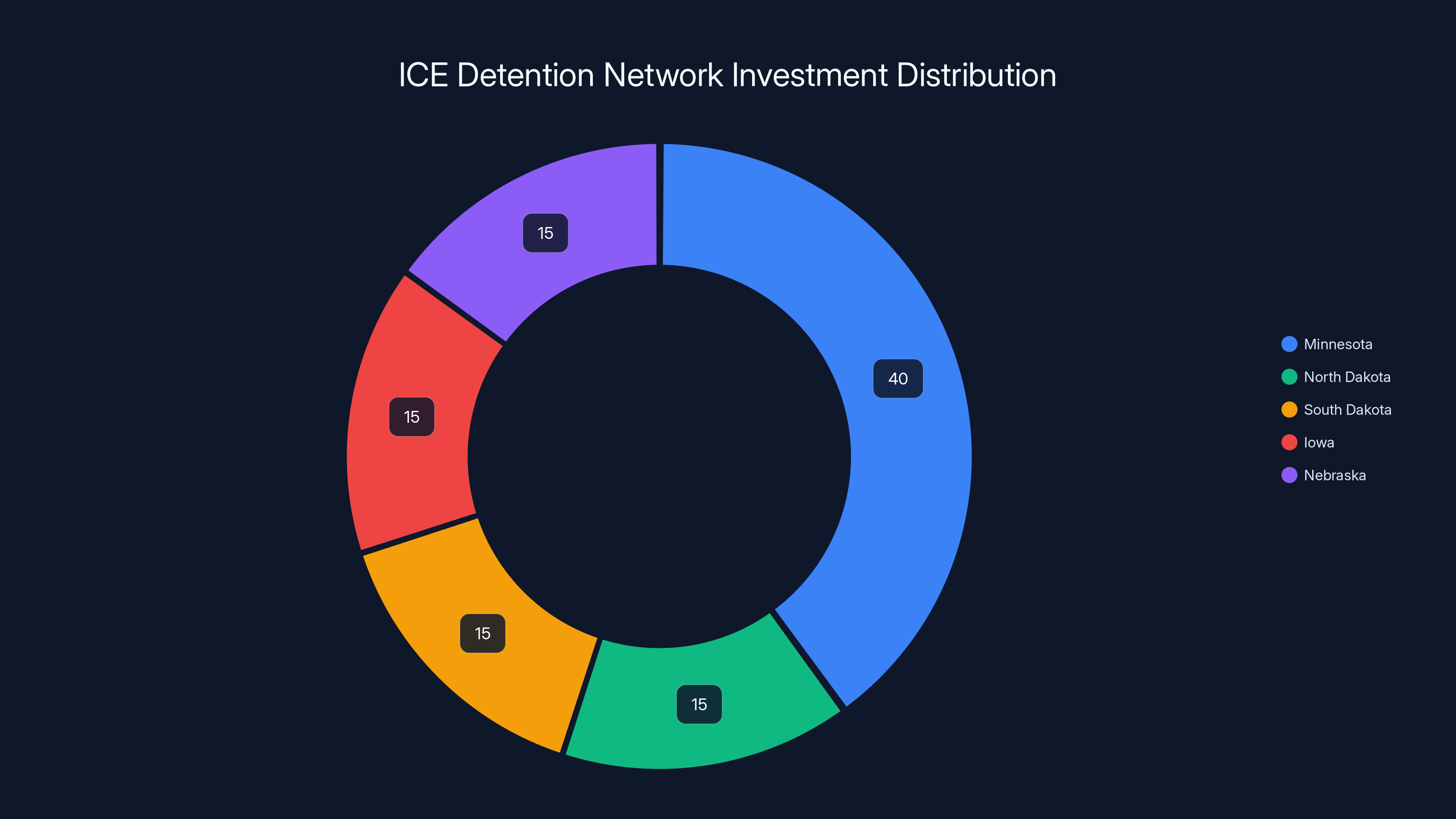

Immigration enforcement in America just got a significant infrastructure upgrade, and most people don't know it happened. Internal planning documents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement show the agency is investing up to $50 million to build what amounts to a regional detention pipeline spanning five states across the Upper Midwest. This isn't just about adding jail beds. It's about creating a system designed to move detained immigrants long distances with minimal transparency, operating across state lines with minimal local oversight.

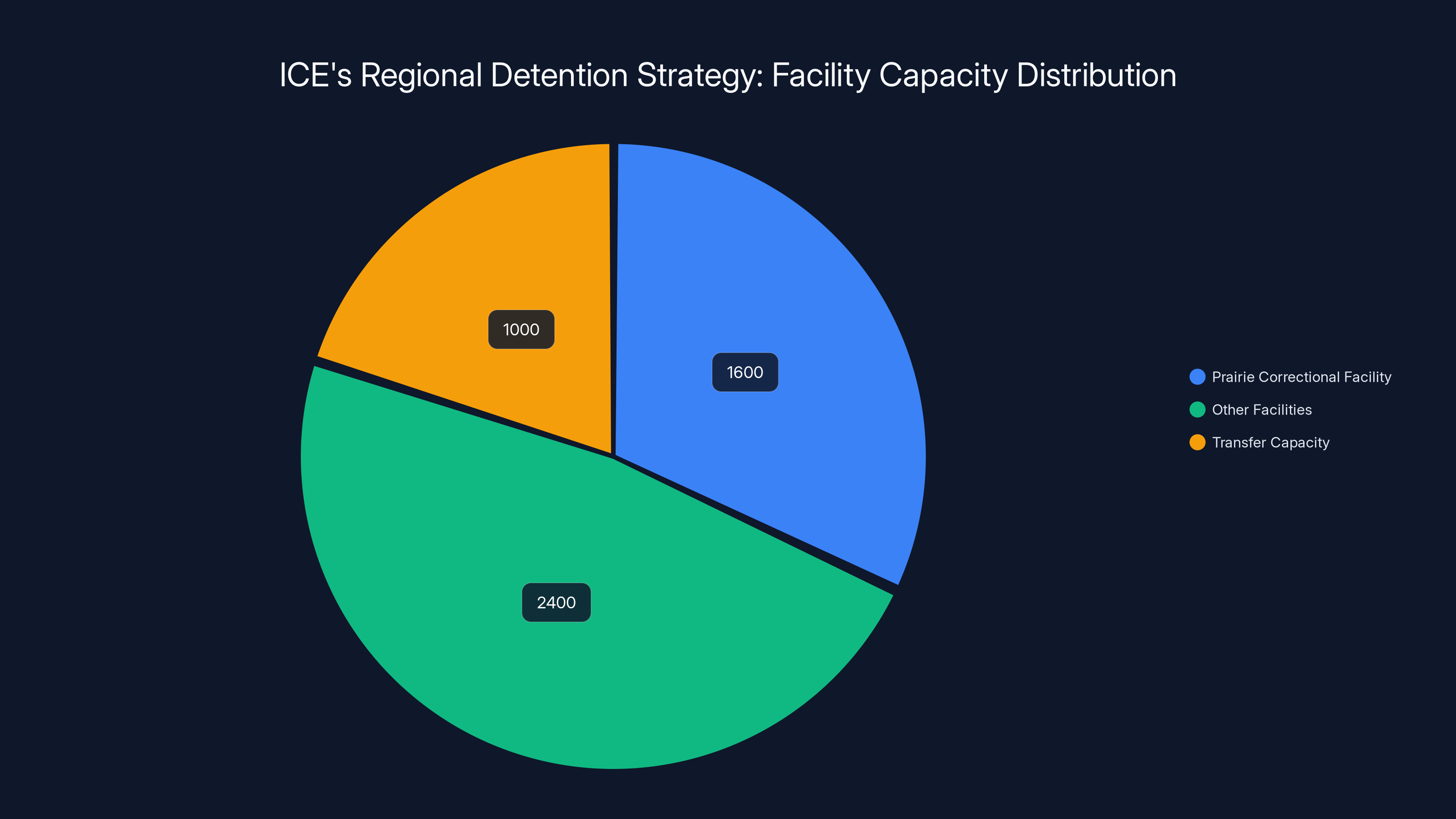

The scale is striking. We're talking about a detention network capable of holding and transferring as many as 1,000 people at any given time, reaching across a 400-mile radius from a central hub. The centerpiece of this expansion is the dormant Prairie Correctional Facility in Appleton, Minnesota, a 1,600-bed private prison that's been mostly empty since 2010. If reopened under ICE contracts, it could become the nerve center of a multi-state detention and transfer operation.

What makes this story complicated isn't just the numbers. It's the timing. These plans were hatched while ICE was simultaneously launching Operation Metro Surge, an aggressive enforcement action that sent thousands of armed agents into Minneapolis and Saint Paul. The operation sparked widespread protests, documented instances of dangerous vehicle interdictions, and led federal judges to impose restrictions on how agents could use force. The backlash turned into a national movement, with over 1,000 protests and rallies calling for ICE operations to end entirely.

The detention network plans reveal something deeper about how immigration enforcement operates at the federal level. They show how bureaucracies work behind closed doors, making permanent infrastructure decisions based on projected needs, often in towns that have little power to refuse. They demonstrate the disconnect between what happens in rural communities and what gets attention in major cities. And they raise serious questions about how private companies profit from immigration enforcement, and what happens to the people caught inside these systems.

This article digs into the details of how this network is supposed to work, where it's located, who's building it, what it will cost, and most importantly, why it matters for immigration policy, criminal justice, and local communities across the Upper Midwest.

TL; DR

- **50 million investment in a detention hub spanning 5 states, capable of transferring 1,000 detainees across a 400-mile radius.

- Appleton Prison: The dormant Prairie Correctional Facility in Minnesota is positioned as the central transfer hub for this network, operated by private company Core Civic.

- Operation Metro Surge: The detention expansion coincides with aggressive ICE raids in Minneapolis-Saint Paul that sparked 1,000+ protests nationwide.

- Private Profit Model: Core Civic and other private prison operators profit directly from contracts to house and transfer detainees, creating financial incentives for detention expansion.

- Limited Local Control: Cities and counties in the network's path have minimal authority to reject or modify ICE detention plans, even when communities oppose them.

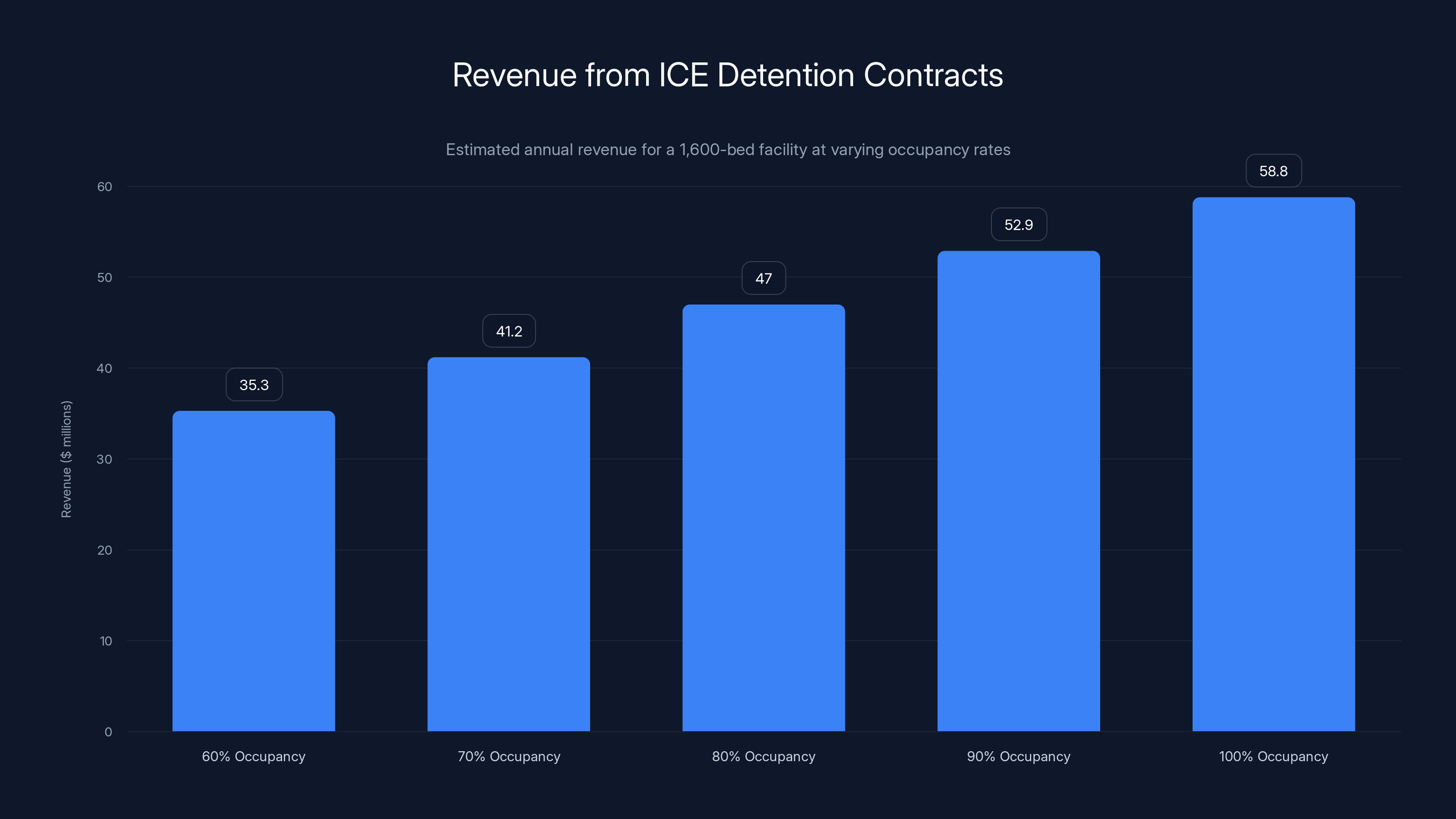

A 1,600-bed facility can generate between

The $50 Million Plan: Mapping ICE's Regional Detention Infrastructure

The numbers tell you right away this is serious infrastructure planning. Between

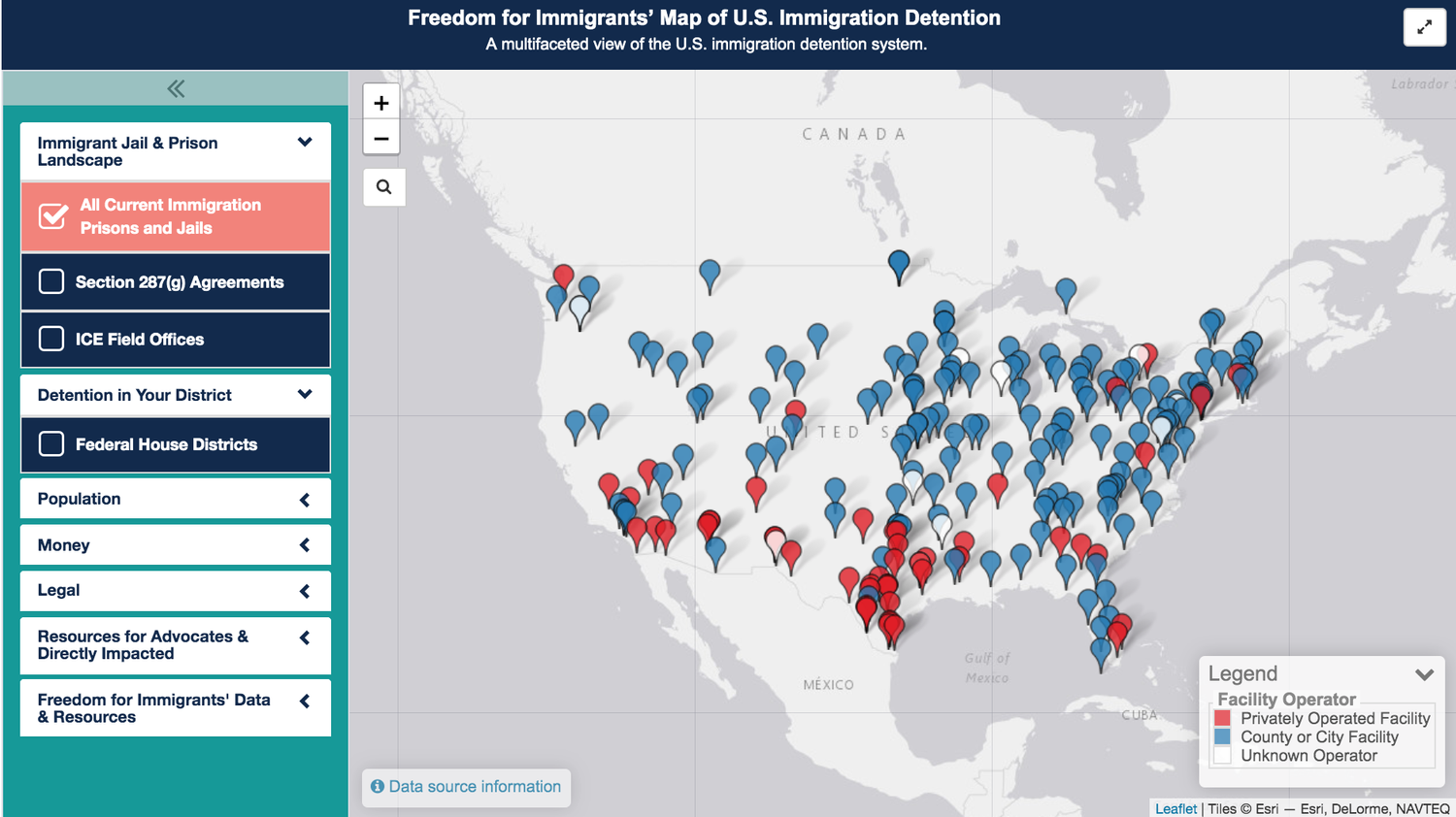

The plan specifies very particular geographic coverage. A "400-mile radius" from the central hub gives you a sense of the scale. From Appleton, Minnesota, that radius covers not just Minnesota itself, but also reaches into North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska. You could fit seven or eight major metropolitan areas inside that circle. The network would create the ability to move people in custody across entire states, transferring detainees far from where they were initially arrested.

Why this matters operationally is important to understand. When ICE detains someone, where they're held determines everything about their case. Distance from home means harder access to legal representation. Distance from family means harder visiting. Distance from community support systems means someone loses their job, their housing, everything that might help them fight deportation. A person detained 400 miles from where they were arrested becomes far more vulnerable to the system moving them toward removal.

The documents also specify transfer capacity, not just detention capacity. That's the key distinction. ICE isn't just looking for places to hold people. They're looking for the ability to move people efficiently. A transfer hub is a logistics center. It's designed for flow, not for stable housing. People move through transfer hubs on their way to somewhere else. The somewhere else, in most ICE detention cases, is either a deportation flight or a detention facility closer to a port of removal.

The timing of these plans is worth examining. These documents were developed over the course of 2024 and early 2025, precisely when ICE leadership was coordinating what became Operation Metro Surge. That operation was explicitly designed to be large, visible, and aggressive. Thousands of armed agents flooding a major metropolitan area wasn't accidental. It was planned. And the detention infrastructure planning seems designed to handle the volume of detainees that an operation like Metro Surge was expected to generate.

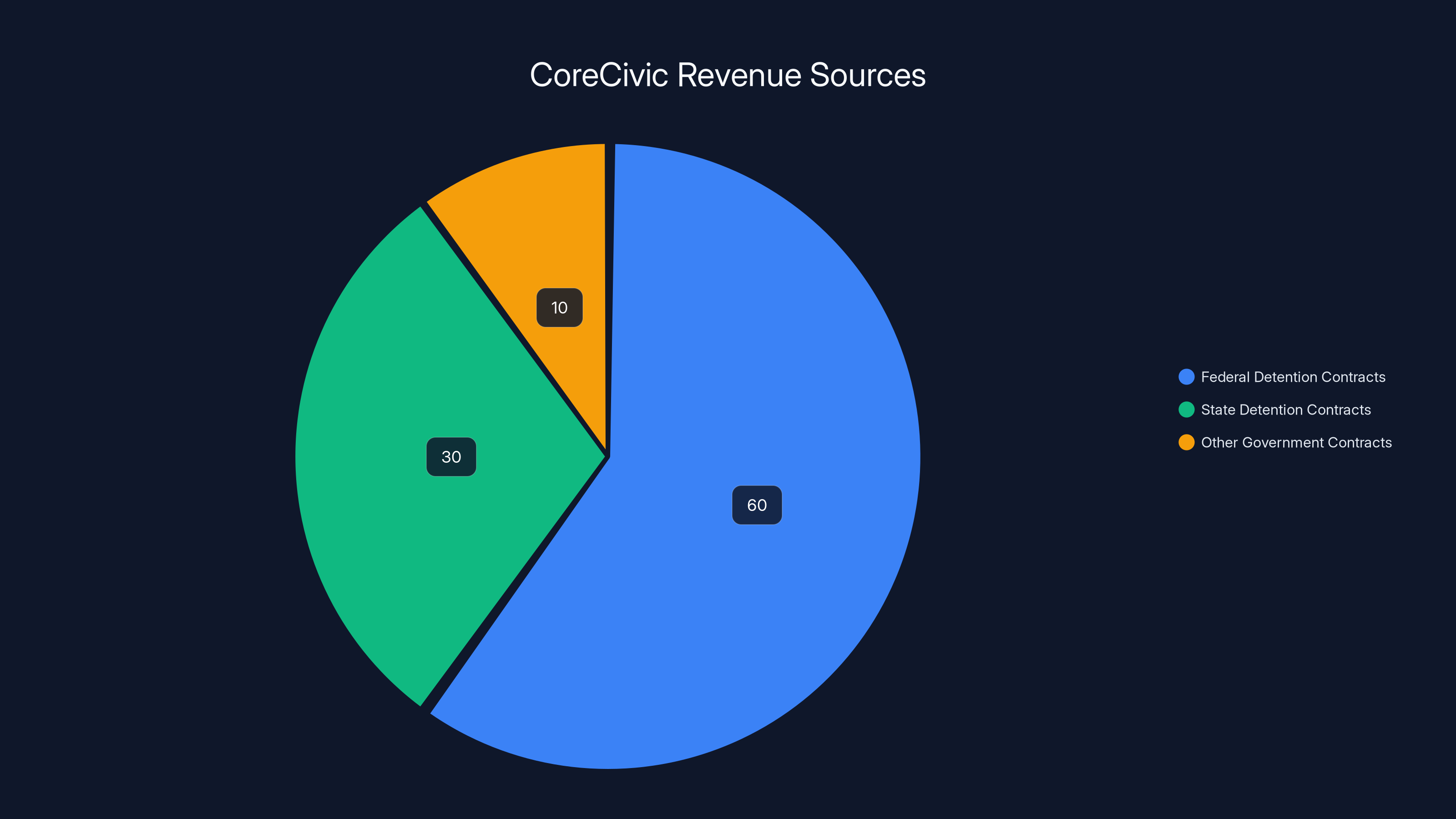

The financial architecture is also revealing. The funding spans multiple potential sources, including direct federal appropriations and contracts with private detention operators. Core Civic, the largest private prison company in America, is intimately involved in these plans. When you understand that Core Civic's business model depends on federal contracts and detention volume, the connection between enforcement operations and infrastructure expansion becomes clearer. More enforcement operations generate more detainees, which justifies higher contract values, which benefits the private operator.

CoreCivic's revenue is heavily reliant on federal detention contracts, estimated at 60% of total revenue, highlighting the company's financial incentive to support policies that increase detention volumes. Estimated data.

The Appleton Prison: From Closure to Potential Reopening

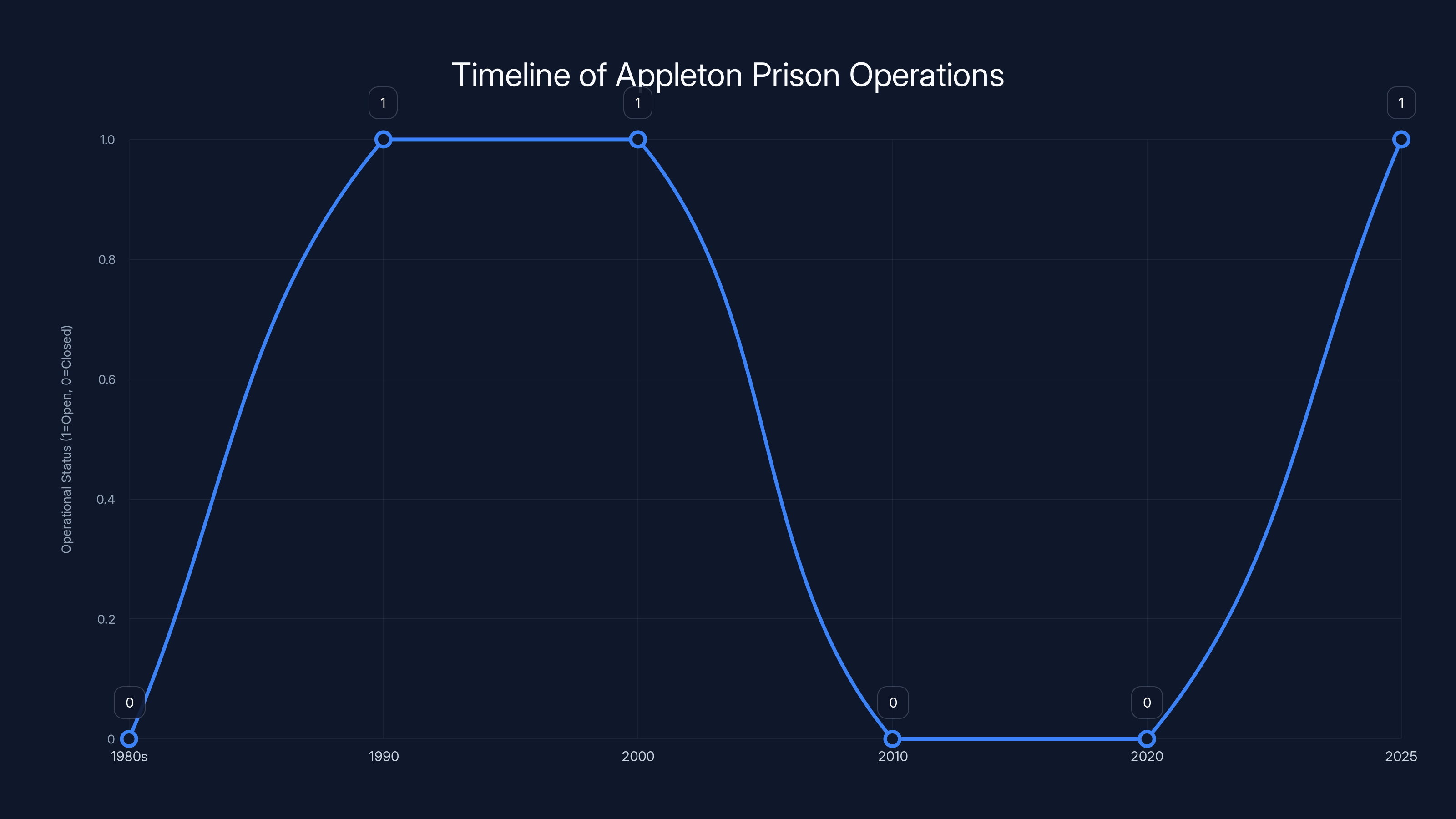

Prairie Correctional Facility in Appleton, Minnesota, isn't some theoretically possible location for ICE detention. It's a specific, real building with a concrete history. Built in the 1980s, the facility was designed to hold about 1,600 people. It operated for roughly 20 years, serving as a regional prison for Minnesota and neighboring states. Then, in 2010, Minnesota changed its approach to criminal justice. The state closed the facility as part of a broader effort to reduce its prison population.

For the past 15 years, the building has been mostly empty. Core Civic, the private company that operates it, has maintained the facility, kept it functional, kept the infrastructure in place. That matters because it means reopening isn't a question of extensive renovation. The building is ready to go. The detention systems are in place. The kitchen, the medical facilities, the security infrastructure, it's all maintained and capable of being activated relatively quickly.

The facility's capacity is exactly the kind of scale ICE is looking for. Sixteen hundred beds isn't a jail. It's a mega-facility, the kind that can absorb detainee populations from across an entire region without needing additional locations. For ICE, that's efficient. One location, one contract, one relationship with one private operator. For Core Civic, it's tremendously profitable. A 1,600-bed contract with ICE, even at moderate per-diem rates, generates substantial revenue.

What makes Appleton significant is its geographic position. It's in south-central Minnesota, reasonably positioned as a hub for the Upper Midwest. It's not in a major metropolitan area, which makes it more isolated for detainees. It's near highway access, which makes it efficient for transfers. It's in a rural community where the facility closure in 2010 caused significant economic pain. That's the exact combination that makes a location attractive for ICE expansion, and potentially attractive to local leaders who remember the jobs the facility provided.

The political dynamics around Appleton are instructive. When news emerged in 2024 that ICE was considering the facility, local clergy and immigrant advocates organized opposition. They held meetings. They circulated petitions. They made clear that reopening the facility to hold ICE detainees would be controversial. But here's the critical part: the city had limited power to stop it. Appleton's city administrator made this explicit in interviews. The facility is allowed within the city's zoning rules. Even if the city wanted to reject ICE's plans, it couldn't.

That's not unique to Appleton. It's how the entire system works. Private prisons occupy a gray area between local control and federal authority. A city can't zone federal detention facilities out of existence. A county can't refuse federal contracts. States have more power but still limited tools. The result is that communities end up hosting infrastructure they didn't choose and can't easily exit.

Proponents of the Appleton facility point to economic arguments. The closure in 2010 cost the town jobs. Reopening would mean employment, tax revenue, and economic activity in a rural area that lost significant population and opportunity after the prison shut down. That's a real argument with real weight in communities where the economy contracted and jobs remained scarce. It creates a difficult dynamic where people who benefit from the facility's presence have strong economic incentives to keep it operating.

Core Civic's Business Model and the Profit Incentive in Detention

To understand why the Appleton facility matters, you need to understand Core Civic's business. The company operates private prisons and detention facilities across America. Its revenue comes almost entirely from government contracts. No contracts, no revenue. The company's financial success is directly tied to how many government detention facilities it operates and how many people it holds.

That's a simple but crucial point. Core Civic doesn't profit from rehabilitation, from reducing incarceration, from cutting detention rates, or from any outcome that might reduce detention volume. The opposite is true. Core Civic profits when detention volumes increase. When governments build larger facilities. When contracts expand. When detention durations lengthen. The company's financial incentives are perfectly aligned with detention expansion, not detention reduction.

ICE is one of Core Civic's major clients. A significant portion of the company's revenue comes from federal detention contracts. The Appleton facility represents potential revenue for Core Civic whether it's operating at 50% capacity or 100% capacity. But obviously, the company prefers higher capacity utilization. And obviously, the company has incentives to support policies and enforcement operations that generate higher detention volumes.

This creates a conflict of interest that's baked into the private detention system. The companies that build and operate detention facilities have financial incentives to increase detention. They lobby for policies that expand detention. They provide infrastructure that makes detention operations easier and more efficient. And they profit from the expansion of enforcement operations like Operation Metro Surge.

Core Core's statement about the Appleton facility is revealing. The company says it's exploring "opportunities with government partners" for which the facility "could be a viable solution." That's corporate language for "we're interested in ICE contracts if the volume justifies the investment." The company isn't trying to hide anything. It's openly acknowledging that it sees the facility as potentially useful for federal detention purposes.

The financial terms aren't publicly disclosed, but you can estimate them. ICE typically pays between

The broader question is whether private detention is actually cheaper than government operation, as private companies claim. The research is mixed. Some studies find private facilities operate at lower cost. Others find that when you account for escapes, misconduct, and facility failures, private detention isn't actually more cost-effective. What's clear is that private detention creates industries and constituencies with powerful financial incentives to expand detention itself. Removing that profit motive would likely change enforcement policy significantly.

Estimated data suggests Minnesota receives the largest share of the $20-50 million investment due to the Appleton hub's central role.

Operation Metro Surge: The Enforcement Context for Infrastructure Expansion

You can't understand the detention network plans without understanding Operation Metro Surge, and you can't understand Metro Surge without recognizing it as a coordinated federal enforcement operation executed with political intent. This wasn't random, decentralized enforcement. This was planned, resourced, and executed with precision.

The operation sent thousands of armed immigration agents into Minneapolis and Saint Paul. That's a significant military-scale deployment to a civilian city. The agents conducted street-level stops, vehicle interdictions, workplace raids, and community sweeps. The operation was designed to be visible and consequential. People knew it was happening because it was meant to be a show of force.

The consequences of that enforcement intensity were immediate. Hundreds of people were detained. That detention volume created a need for detention infrastructure. And that's where the planning documents connect to the real-world enforcement. ICE doesn't just arrest and detain on impulse. It plans for detention capacity based on projected enforcement volume. Metro Surge generated detention volume that justified the infrastructure expansion already in planning.

The operation also generated significant resistance. Protests erupted in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. Organizers mobilized quickly. The movement expanded beyond Minnesota to become a national action. Over 1,000 protests and rallies took place nationwide calling for ICE operations to end. That grassroots resistance is important because it shows how the detention network became a flashpoint for broader opposition to immigration enforcement.

In court, the operation faced legal challenges. Plaintiffs argued that ICE agents were using excessive force against protesters and observers. A federal judge agreed and imposed restrictions on how agents could use force during the operation. Those restrictions represent a rare legal win against federal enforcement, though the Trump administration appealed the ruling, suggesting the government intended to continue enforcement with fewer constraints if legally possible.

The operation demonstrates how federal enforcement and detention infrastructure work together. Large enforcement operations require detention capacity. Detention capacity that doesn't exist has to be built. And once the infrastructure exists, it creates pressure to utilize it, to keep it operating at the capacity for which it was designed. It becomes self-perpetuating. The existence of the infrastructure justifies continued enforcement that keeps the infrastructure full.

Multi-State Coordination: How ICE Plans to Operate Across State Lines

One of the most significant aspects of this detention network is its explicitly multi-state nature. ICE isn't building a facility for Minnesota detention. It's building a regional system for the Upper Midwest. That requires coordination mechanisms that operate across state boundaries and, critically, that minimize state and local government involvement.

The 400-mile radius gives ICE enormous flexibility in where it houses detainees and where it transfers them. Someone arrested in Minneapolis could be transferred to Appleton, then transferred again to a facility in South Dakota or Nebraska. The person could end up hundreds of miles from where they were originally detained, making it harder to maintain legal representation, harder for family to provide support, and generally making it easier for ICE to move people toward removal without the kind of oversight that closer proximity to home would enable.

This multi-state approach also spreads the infrastructure needs across multiple jurisdictions, which distributes the controversy. Instead of one community hosting a large detention facility, multiple communities host portions of the system. The Appleton facility becomes the hub, but other detention space comes from agreements with existing jails in North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska. That means the burden and the controversy are spread across multiple states and multiple communities.

The coordination also matters for transfer logistics. A true hub-and-spoke system requires vehicles, drivers, routes, and timing coordination. The planning documents specify the capability to move people within this 400-mile radius efficiently. That requires pre-planned transfer routes, relationships with multiple facilities across state lines, and logistics infrastructure that can operate across jurisdictional boundaries.

From ICE's perspective, this multi-state approach is efficient. It reduces the need for negotiating with individual states that might have policies opposing certain detention practices. It spreads the infrastructure across multiple economies so no single location bears the full burden. And it creates operational flexibility where people can be moved to whichever facility has available capacity, without regard to where they were originally detained or arrested.

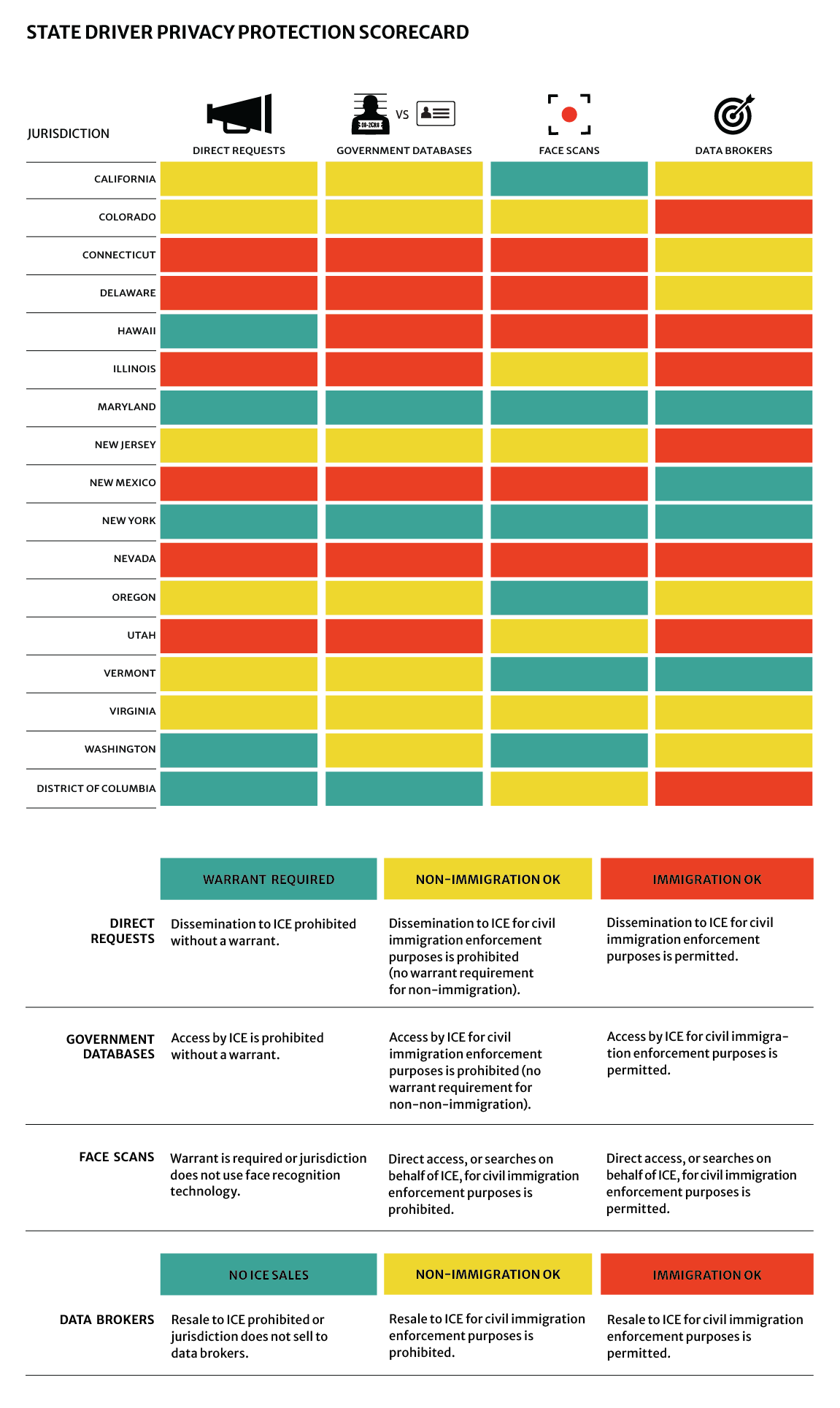

From a policy perspective, it reveals something important about how federal enforcement operates. ICE doesn't need state permission to operate detention facilities. The agency can contract directly with private companies and local jails. States can pass laws limiting cooperation, but those laws are limited in scope and easy to work around. The federal government has sufficient financial resources to incentivize cooperation even from jurisdictions that might otherwise object.

The multi-state coordination also makes oversight harder. When detention happens in one jurisdiction, that jurisdiction's courts, attorneys, and advocates can engage. When detention is spread across five states and multiple facilities, oversight becomes fragmented. A lawyer in Minnesota might not know where their client was transferred to in South Dakota. A family in Minneapolis might not be able to visit someone held 300 miles away. The fragmentation serves the detention system's interests by making it harder to coordinate resistance or legal challenges.

The Prairie Correctional Facility could hold 1,600 beds, forming a significant part of ICE's 5-state detention network, with other facilities and transfer capacity making up the rest. Estimated data.

The Detention Process: How Detainees Move Through the Network

Understanding the detention network requires understanding how people actually move through it. This isn't a system where someone is arrested and held in one place until resolution. It's a system where people are moved multiple times for various operational reasons.

The typical flow works something like this. Someone is detained by ICE in Minneapolis or another Twin Cities location. They're taken to an initial holding facility, which might be a local jail or an ICE facility. While there, they're processed, their information is entered into systems, and ICE determines what removal flight or transfer facility will ultimately receive them. That process can take days or weeks.

During that time, ICE might transfer the person to a facility with available capacity. If the Twin Cities area is at capacity, that person gets transferred to a facility in the Appleton hub or to a facility in another state within the network. The transfer is logged, but it doesn't guarantee that the person's family or legal representatives are informed. In many cases, people are transferred without notice, and their whereabouts become unknown to people trying to help them.

Once at the regional hub, the person might be held there for additional processing, security screening, and determination of appropriate removal location. Or they might be transferred again to a facility closer to a deportation airport. Each transfer increases distance from legal representation and family support. Each transfer also creates records that might not be easily accessible to people trying to locate or help the detained person.

This cascade of transfers, enabled by the infrastructure, is partly how the system separates people from support. A person detained in Minneapolis might end up in a facility in Appleton they've never heard of, 250 miles away. Their family might spend weeks trying to find them. Their lawyer might not receive proper notice of transfers. By the time the legal system catches up, the person might already be on a removal flight.

The system also creates opportunities for what researchers call "disappearance by bureaucracy." A person is held, then transferred, then transferred again. Records don't perfectly sync. Someone looking for them might check one facility and be told the person isn't there, not realizing they were transferred a day earlier. The infrastructure enables this fragmentation by design, even if it's not always intentional.

The detention facilities themselves operate under varying standards. Some are county jails that house ICE detainees as a secondary function. Others are dedicated ICE facilities. The private facilities like Appleton have their own operational standards. The variation in conditions, staffing, and rules across the network means that detainee experience depends partly on which facility in the network they land in at which moment.

Legal and Constitutional Questions Raised by the Network

This detention network raises serious constitutional and legal questions that haven't been fully litigated. The multi-state transfer approach, the use of private detention operators, the lack of local oversight, and the sheer volume of people moving through the system create several legal issues that civil rights organizations are monitoring.

The first issue is due process. When someone is transferred multiple times across state lines, do they receive adequate notice of their location? Can they access legal representation? Can they communicate with family? The constitutional requirement of due process includes the right to know where you're being held and the right to challenge your detention. When the infrastructure is designed for speed and efficiency rather than transparency, these rights become harder to exercise.

The second issue is the use of private detention operators. Courts have examined whether private companies have the authority to detain people on behalf of the federal government. Most courts have found that private detention is permissible if the government maintains ultimate authority. But the question remains whether private companies have incentives that conflict with constitutional obligations. If a company profits from high detention volume, does that create an unconstitutional conflict of interest? That question hasn't been definitively resolved.

The third issue is whether states can limit ICE's use of facilities within their borders. Some states have passed laws limiting cooperation with ICE. But ICE can contract directly with private companies and local jails. States have limited power to prevent that. The question of where state sovereignty ends and federal authority begins remains contested.

The fourth issue is whether the detention network violates principles of equal protection. If the network is designed to make detention easier and removal more likely, and if that's done selectively against certain nationality groups, does that raise constitutional concerns? That's a harder question legally, but immigrant advocates argue that enforcement operations and detention infrastructure are disproportionately applied to certain communities.

Civil rights organizations have filed lawsuits challenging various aspects of Operation Metro Surge, including the use of force against protesters and the conditions of detention. Those lawsuits suggest that legal challenges to the detention network are coming. The courts haven't yet addressed the specific question of whether a multi-state detention network designed for efficiency and transfer is compatible with constitutional limitations on detention authority.

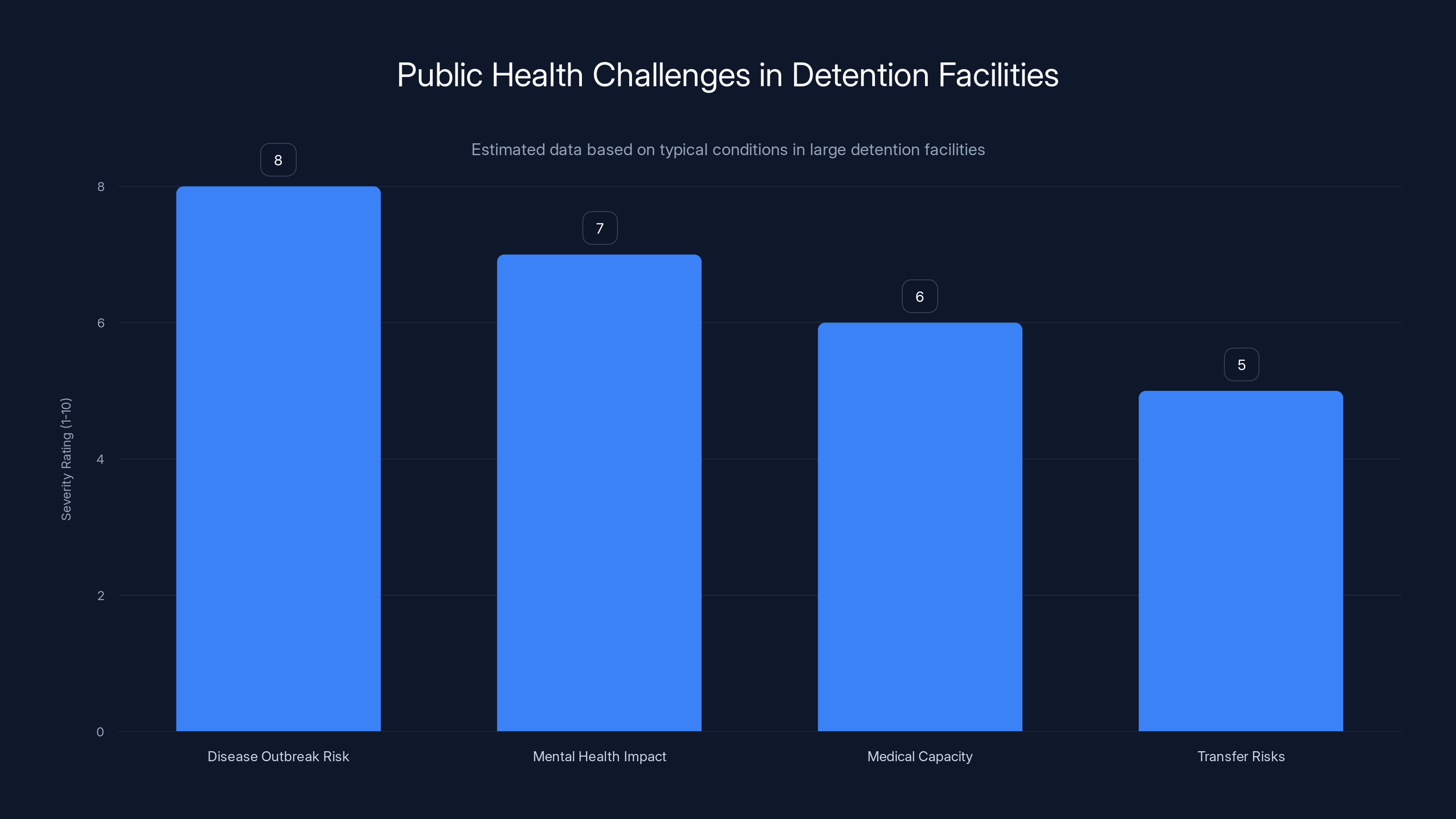

Detention facilities face significant public health challenges, with high risks of disease outbreaks and mental health impacts. Estimated data highlights key areas of concern.

Local Community Response and Resistance

The detention network has generated organized opposition at the local level, particularly in Appleton where the Prairie Correctional Facility reopening is most directly proposed. The response reveals how communities are grappling with the infrastructure expansion.

Clergy and immigrant advocates organized opposition to the Appleton facility in 2024. They held community meetings. They circulated petitions. They made clear that reopening the facility for ICE detention would be controversial within the religious and immigrant-serving communities. Their argument was straightforward: reopening would bind a rural town to detention decisions made elsewhere, normalize the idea that rural communities should host detention facilities, and create economic and social costs that local residents didn't choose.

Proponents of the facility offered a different argument. They pointed to the economic benefits of reopening. The closure cost jobs in a rural community where opportunity was already limited. Reopening would bring employment, tax revenue, and economic activity. They argued that the moral concerns about detention were reasonable but shouldn't override the economic needs of the community. It's a tension that exists in many rural communities, where opposition to an industry might mean accepting continued economic decline.

The city government's position was constrained. The administrator made clear that the city can't reject the plan because the facility is allowed under zoning rules and federal authority supersedes local zoning when detention is involved. That limitation on local power is important because it shows how federal detention infrastructure can be imposed on communities whether they want it or not.

Beyond Appleton, the broader ICE expansion has generated national opposition. The "ICE Out for Good" weekend of action in 2025 mobilized over 1,000 protests and rallies nationwide. The movement isn't just about detention infrastructure. It's about opposition to ICE operations, enforcement practices, and the entire detention and deportation system. But the physical infrastructure of detention becomes a focal point because it's tangible and local.

Communities across the Midwest are beginning to understand that they could host ICE detention facilities. Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska might all see proposals to house ICE detainees in existing facilities or new construction. The movement against the detention network is trying to preemptively organize opposition in those communities before the proposals become concrete.

The Business of Immigration Detention: Revenue Models and Contracts

The detention network represents hundreds of millions of dollars in potential revenue for private detention operators. Understanding the financial incentives is crucial to understanding why the system is expanding the way it is.

ICE detention contracts typically specify per-diem rates, meaning the government pays a fixed amount per day for each person held. The rates vary by facility type and region, but generally range from

Those are substantial numbers for a company like Core Civic. The Appleton contract alone could represent 10-15% of the company's total revenue if it reaches full capacity. That explains why Core Civic has an incentive to maintain the facility during periods when it's not operating, and why the company is actively pursuing ICE contracts.

The contracts also typically include base fees and performance-based payments. A facility might earn a certain amount per bed per day for detention space, plus additional payments for services like medical care, food service, and security. Some contracts include utilization guarantees, where the government pays for a certain minimum occupancy whether the beds are full or not. Those guarantees protect the private operator's revenue even if detention volume drops.

From ICE's perspective, private detention is supposedly more cost-effective than government-run facilities. The argument is that competition drives down costs and incentivizes efficiency. But research on private detention costs is mixed. Some studies find private facilities cost less. Others find the differences are negligible or that hidden costs make private detention more expensive overall. What's indisputable is that private detention creates powerful constituencies with incentives to expand detention.

The detention business also extends beyond just housing detainees. Private companies provide food service, medical care, security, and transportation. Those contracts create additional revenue streams and additional constituencies with interests in detention expansion. A food service company contracts with the detention facility. A medical services company contracts to provide healthcare. Transportation companies contract to move detainees. The entire ecosystem benefits from detention expansion.

The business model also explains some of the system's characteristics. Private operators have incentives to minimize costs, which sometimes leads to inadequate staffing, poor conditions, and insufficient services. They have incentives to maximize bed utilization, which means they're generally not eager to see detention volume decrease. And they have incentives to maintain contracts, which means they lobby for policies that sustain enforcement operations.

The Appleton Prison operated from the 1980s until its closure in 2010. It remains closed but maintained, with potential for reopening in the near future. Estimated data.

Capacity Planning and Detention Projections

The planning documents that outline the detention network include specific capacity projections. ICE is planning for a system that can hold and transfer as many as 1,000 people at any given time. That's not a small number. To put it in context, the largest local jails in America hold somewhere between 3,000 and 8,000 people on any given day. A thousand people at any given time in the Upper Midwest region represents a significant detention population.

Those projections come from somewhere. They're based on ICE's estimates of how many people it expects to detain in the Upper Midwest region over a given period. Those estimates, in turn, are based on enforcement priorities, staffing levels, and expected removal volume. In other words, ICE projected enforcement intensity and then calculated the detention capacity needed to support that intensity.

The projections also inform the infrastructure design. A system designed for 1,000 people at any given time means multiple facilities, multiple transfer routes, and redundant capacity. It means the network is built larger than the projected need in order to handle peaks and variability. That excess capacity, in turn, creates pressure to utilize it, to keep the system running at or near full capacity because maintaining infrastructure requires ongoing funding.

Those capacity projections are also relevant to understanding what enforcement intensity ICE expects. If the agency is planning detention infrastructure for 1,000 people in the Upper Midwest, that implies expectations of substantial enforcement operations. Operation Metro Surge generated detention volume consistent with those projections. The enforcement and the infrastructure are coordinated, not separate decisions.

The planning also includes considerations of peak capacity and seasonal variation. Enforcement isn't constant throughout the year. Some months have higher enforcement intensity than others. The detention infrastructure needs to handle peaks without being massively oversized for baseline operations. That requires a network of facilities with varying capacity rather than one enormous facility. It also requires transfer capability to move people between facilities based on real-time capacity needs.

Transportation Infrastructure and Logistics

The multi-state network requires transportation infrastructure that's often overlooked in discussions of detention. Moving people across a 400-mile radius requires vehicles, drivers, routes, and logistics coordination. That infrastructure is part of what the $50 million investment covers.

ICE operates its own transportation fleet, but the agency also contracts with private companies for transportation services. Those contracts include everything from individual vehicle transport to large-scale movement on aircraft. The detention network requires reliable transportation capacity to move detainees between facilities, to move detainees to removal flights, and to handle emergency relocations if a facility has problems.

The transportation aspect also creates opportunities for detainee harm. Cases of detainees dying during transport, detainees being subjected to dangerous driving, and detainees being transported in inadequate conditions have all been documented. The emphasis on efficiency and moving people quickly through the system sometimes comes at the cost of safety and dignity.

Transport drivers can determine conditions during transport. How long someone sits in a vehicle, what access they have to water or restrooms, how they're physically handled, these details depend on driver training, supervision, and incentive structures. Private transportation companies, like private detention facilities, have incentives to minimize costs, which can mean inadequate staffing, minimal training, and insufficient safety measures.

The transportation infrastructure also creates coordination problems across state lines. A person being moved from Minnesota to Nebraska requires coordination between multiple ICE field offices, multiple transportation services, and multiple receiving facilities. That coordination can break down. People get lost in the system. Records don't sync. The logistical complexity creates opportunities for failures that harm detainees.

Digital Infrastructure and Data Systems

Behind the physical detention network is a digital infrastructure that tracks people, manages transfers, and coordinates operations. Understanding this digital layer is important because it's where the system's discrimination and errors become embedded in code and algorithms.

ICE operates the ENFORCE database, which tracks detainees, their cases, transfer history, and removal status. That system feeds information to other systems used by immigration courts, detention facilities, and removal operations. In theory, the system creates transparency and coordination. In practice, the system is often inaccurate. People are listed in the system under wrong names. Their locations are inaccurately recorded. Their case status is misstated. The errors compound when people are transferred multiple times, as the detention network enables.

The digital infrastructure also implements algorithmic decision-making about detention and removal priorities. ICE uses scoring systems that determine which cases are prioritized for prosecution and removal. Those scoring systems incorporate information about criminal history, immigration status, family ties, and other factors. Research on similar algorithms in criminal justice has found that they often embed bias and discrimination. The same risks exist in ICE's systems.

The detention network increases reliance on these systems. When detainees are moving through multiple facilities, the digital tracking becomes even more critical. If the system is inaccurate or biased, those errors scale up across the network. A person listed under the wrong name in one facility might not be found when their lawyer searches for them. A person with an inaccurate case status might be moved toward removal despite having pending legal claims.

The digital infrastructure also enables the kind of efficiency that the detention network is designed to achieve. By automating aspects of detention management, the system can process more people faster. That efficiency comes at a cost to individual attention and review. The more automated the system becomes, the harder it is to catch errors and the more likely those errors are to proceed through the system unchecked.

Public Health and Detention Conditions

Large detention facilities create public health challenges that are relevant to the network's design. The Prairie Correctional Facility in Appleton has been empty for 15 years. Reopening a facility that's been vacant requires substantial preparation. Water systems need to be tested. Biological hazards might have developed. The facility needs to be thoroughly cleaned and inspected before it can safely hold people.

Beyond the initial reopening, operating a 1,600-bed facility creates ongoing public health challenges. Large detention facilities are prone to disease outbreaks. Crowding, poor ventilation, inadequate medical care, and stress create conditions that enable rapid disease transmission. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed those vulnerabilities in detention facilities across the country.

The multi-facility network also creates public health coordination challenges. If a disease outbreak occurs in one facility, the system's transfer capability means the disease can be spread to other facilities. A person from an infected facility transferred to another location could introduce infection to that facility. The network's emphasis on mobility and efficiency creates public health risks.

Detention conditions also affect mental and physical health. People held for extended periods experience deterioration in mental health. The stress of detention, separation from family, and uncertainty about outcomes create psychological harm. The longer someone is detained, and the further they are from family and support systems, the more severe the health consequences.

The Appleton facility's medical capacity is one question that hasn't been fully addressed. If the facility operates at full capacity, it will need substantial medical services. ICE contracts for medical care are sometimes inadequate to cover detainee health needs. Private medical companies maximize profits by minimizing costs, which can mean inadequate staffing and insufficient services.

The Political Context: Immigration Enforcement Policy Changes

The detention network plans were developed in a political context where immigration enforcement became increasingly aggressive. The Trump administration prioritized enforcement operations and detention expansion. That political context made the detention infrastructure plans possible and necessary.

ICE's operating philosophy under Trump administration officials emphasized enforcement of all applicable immigration law, not just cases involving criminal convictions. That expanded the potential detention population from people convicted of crimes to anyone determined to be in the country without proper documentation. The expanded enforcement focus created a need for expanded detention capacity, which generated the planning for the detention network.

The shift in enforcement philosophy also affected how resources were allocated. Operations like Metro Surge required thousands of agents deployed to a single city. That concentration of enforcement resources was made possible by priorities set at the policy level. Similarly, the detention infrastructure expansion reflected a policy decision that detention volume would be substantial enough to justify the investment.

The political context also affects what happens next. If enforcement priorities shift, if a future administration de-emphasizes detention operations, the infrastructure built for expansion might become unnecessary. Alternatively, if enforcement continues at current levels or intensifies further, the infrastructure might quickly reach capacity and demand additional expansion.

The political negotiations around the detention network also involve state and local officials. Some state governments have policies opposing certain detention practices. Some local governments have declared themselves sanctuary jurisdictions. The federal detention network is partly a way to work around those state and local limitations by building infrastructure that doesn't depend on local cooperation.

Looking Forward: Expansion, Legal Challenges, and Resistance

The detention network plans specify an expected contract award in early 2026. That means the process of formal solicitation, contract negotiation, and facility activation could happen quickly once the decision is made to proceed. Understanding what happens next requires looking at multiple dimensions of how the system might develop.

From ICE's perspective, the goal is to have the Appleton facility and the regional network operational and at substantial capacity within 12-18 months. That means engaging with Core Civic to prepare the facility, negotiating agreements with other facilities in the network, and setting up transfer logistics. None of that is particularly difficult from a technical perspective. The obstacles are more likely to be political and legal.

Legal challenges are virtually certain. Civil rights organizations have committed to litigation against the detention network. The lawsuits will likely focus on due process violations, conditions of detention, and the constitutionality of private detention operations. Those lawsuits could delay implementation and create public record evidence of the system's operations.

Political opposition will likely intensify. The organized resistance that emerged around Operation Metro Surge has created networks of advocates, legal organizations, and community groups prepared to challenge detention infrastructure expansion. The movement will likely attempt to prevent facility reopening through political pressure, protests, and community organizing.

The detention network also faces practical obstacles. Rural communities might organize opposition. Law enforcement and county officials might resist having ICE detention facilities in their jurisdictions. The legal and political landscape could shift with election results. What seems possible in 2025 might be more difficult in 2026 or 2027.

At the same time, the federal government has substantial resources to make the network happen. ICE can fund the infrastructure. Core Civic can operate it. Federal law requires cooperation from local facilities receiving ICE detainees. The political will to expand detention exists within the Trump administration. The main question is whether legal and political opposition will be sufficient to stop or significantly delay implementation.

The detention network also sets a template for future enforcement operations. If the Appleton facility becomes operational and the multi-state network functions as planned, it will demonstrate a model that could be replicated in other regions. The federal government could establish similar detention hubs in the Southwest, Texas, California, and other regions. Each region would have its own private hub facility connected to surrounding detention locations through transfer protocols. Over time, that could create a nationwide detention infrastructure designed for efficiency rather than local accountability.

Implications for Immigration Policy and Criminal Justice

The detention network represents a substantial shift in how immigration enforcement and detention operations are conceived and implemented. Rather than detention being an incidental aspect of enforcement, detention becomes the central infrastructure that enables enforcement. The detention network is planned before enforcement operations, and the enforcement operations are designed to fill the detention capacity.

That reversal matters for policy analysis. When detention capacity is the starting point, enforcement becomes shaped by the need to utilize that capacity. Immigration policy becomes less about determining who should be removed and more about removing whoever detention infrastructure can hold and process. The existence of the infrastructure creates pressure to use it.

The privatization of detention also matters significantly. Private operators have financial incentives to maximize detention volume and duration. Those incentives can be at odds with fair and humane immigration enforcement. A system designed to serve the detained person's interests would minimize detention duration, maximize their access to legal representation, and focus on humane resolution. A system designed to serve private operator profits would do the opposite.

The multi-state coordination also changes how immigration enforcement operates geographically. Rather than detention happening at the local level where enforcement occurs, detention becomes regional and coordinated. That change makes local oversight harder and makes it easier for federal enforcement priorities to supersede local preferences.

The detention network also has implications for criminal justice more broadly. Mass detention infrastructure designed for one enforcement context often gets repurposed for others. The facility could end up housing federal criminal detainees, immigration detainees, and state detainees at different times depending on federal and state priorities. That flexibility maximizes the facility's revenue but creates unpredictability for communities.

Conclusion: The Permanence of Infrastructure Decisions

Infrastructure decisions matter because they're remarkably permanent. A detention facility built today will likely operate for decades. The Appleton facility was built in the 1980s and operated for 20 years, then sat empty for 15 years, and is now being considered for another 20+ years of operation. That 60-year arc shows how infrastructure outlasts political administrations and policy shifts.

The detention network being planned now will likely outlast the Trump administration. Future administrations, even if they want to de-emphasize detention, will face existing infrastructure that was expensive to build and would be costly to shut down. The facility will have employees who depend on it. The surrounding community will have become accustomed to its revenue. The federal government will have made contractual commitments. The path dependency created by infrastructure becomes increasingly difficult to reverse over time.

That's why the decisions being made now, in 2025 and 2026, matter so much. If the detention network is built, it will shape immigration enforcement for decades. If it's prevented or delayed, different approaches become possible. The stakes are high because infrastructure decisions are essentially permanent.

The detention network also reveals something important about how federal power operates. Immigration enforcement is a federal function, but detention happens at the local level, in local communities, often over local objections. Federal financial resources allow the federal government to impose infrastructure decisions on communities that lack the power to refuse. That dynamic, repeated across multiple communities and regions, creates a nationwide detention system shaped by federal priorities rather than local consent.

For communities across the Upper Midwest, the immediate question is whether the detention network will become operational. For the detained people and families affected by it, the immediate question is how the network will function and what impact it will have on their lives. For immigration policy and criminal justice more broadly, the question is whether the detention infrastructure becomes permanent and whether other similar networks are built in other regions.

The resistance to the detention network is significant and growing. But the resources available to build and operate the network are also substantial. The outcome will depend on whether organized opposition proves sufficient to stop or substantially delay a federal initiative backed by significant financial resources and political commitment. That struggle will play out over the next 12-24 months as the detention network moves from planning documents to concrete infrastructure.

FAQ

What exactly is the ICE detention network being planned in the Upper Midwest?

The network is a $20-50 million investment in detention infrastructure spanning Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska, designed to hold and transfer up to 1,000 detained immigrants at any given time across a 400-mile radius. The centerpiece is the dormant Prairie Correctional Facility in Appleton, Minnesota, a 1,600-bed private prison that has been mostly empty since 2010, which would serve as a transfer hub coordinating detainee movements across the region.

How does the detention network function operationally?

The network operates as a hub-and-spoke system where detainees arrested in the Twin Cities or other locations are initially held at local facilities, then transferred to the Appleton hub if needed, then potentially transferred again to facilities in neighboring states depending on available capacity and removal flight schedules. This structure allows ICE to move detainees efficiently across large geographic distances, though it also makes it harder for detainees to maintain legal representation and family contact during transfers.

Why is the multi-state transfer capability important?

The ability to transfer detainees across state lines and up to 400 miles away serves several operational purposes for ICE. It maximizes utilization of detention beds by moving people to wherever space is available, increases efficiency of removal operations by positioning detainees near deportation flights, and significantly complicates the ability of detainees' families and lawyers to locate them and provide legal representation. The distance between initial detention and the hub also isolates detainees from community support systems that might otherwise help them fight removal.

Who profits from the detention network and what are their financial incentives?

Core Core, the nation's largest private prison company operating the Appleton facility, stands to profit substantially from ICE contracts worth potentially $47 million annually at full capacity. The company's financial interests are directly aligned with expansion of detention volume, longer detention durations, and continued government enforcement operations. Additionally, companies providing food service, medical care, and transportation for detainees also benefit financially from detention system expansion.

What legal and constitutional questions does the detention network raise?

The network raises significant questions about due process rights for transferred detainees, whether private detention operators have constitutional conflicts of interest given their profit incentives, the extent to which states can limit ICE detention within their borders despite federal supremacy, and whether enforcement and detention practices that disproportionately affect certain nationality groups violate equal protection principles. Multiple civil rights organizations have indicated they plan litigation challenging various aspects of the detention network.

What is the timeline for the detention network becoming operational?

ICE planning documents specify an anticipated contract award in early 2026, which would likely lead to facility activation and network implementation within 12-18 months thereafter. However, legal challenges, political opposition, and community organizing could substantially delay or prevent implementation. The exact timeline depends on whether organized resistance proves sufficient to stop or delay the project despite federal government commitment and resources.

How does this detention network connect to Operation Metro Surge?

Operation Metro Surge, the aggressive ICE enforcement operation deployed to Minneapolis-Saint Paul, generated substantial detention volume that justified the detention infrastructure planning already underway. The enforcement operation and detention infrastructure expansion are coordinated elements of the same federal strategy rather than separate decisions. The detention network's capacity projections are based partly on the enforcement intensity demonstrated by Metro Surge.

Can local communities reject the detention network?

No. While some cities and states have policies opposing certain ICE detention practices, they lack legal authority to prevent federal detention facility operation within their jurisdictions. ICE can contract directly with private companies and existing facilities without requiring local approval. City zoning rules cannot be applied to federal detention facilities. States have limited tools to resist, primarily limited to restricting cooperation beyond minimum requirements, but cannot prevent federal operations.

Key Takeaways

- ICE planning documents outline a $20-50 million multi-state detention network spanning 5 Upper Midwest states with capability to transfer 1,000 detainees within a 400-mile radius.

- The dormant Prairie Correctional Facility in Appleton, Minnesota serves as the proposed central hub for the detention network, operated by private company CoreCivic.

- The detention network was planned in coordination with Operation Metro Surge, an aggressive enforcement operation that generated detention volume justifying infrastructure expansion.

- Private detention operators like CoreCivic have direct financial incentives to maximize detention volume, creating conflicts of interest with fair and humane immigration enforcement.

- Local communities and states have limited legal authority to reject federal detention facilities, despite substantial opposition from immigrant advocates and community organizations.

Related Articles

- Minnesota Sues to Stop ICE 'Invasion': Legal Battle Over Operation Metro Surge [2025]

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

- Minnesota's ICE Sousveillance Strategy: States' Rights vs. Federal Power [2025]

- How Political Media Targets Marginalized Communities [2025]

- ICE Agents and Qualified Immunity: Why Accountability Remains Elusive [2025]

- Trump's Immigration Enforcement Playbook Targets Blue States [2025]

![ICE's $50M Minnesota Detention Network Expands Across 5 States [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-s-50m-minnesota-detention-network-expands-across-5-state/image-1-1768937842519.jpg)