Introduction: When Citizens Become Documentarians of Their Own Government

Something shifted in January 2025 when a sitting governor took to primetime television and asked his constituents to do something that would've been unthinkable just years ago. He asked them to film federal agents.

Governor Tim Walz of Minnesota stood before cameras and invited Minnesotans to document what he called "atrocities against Minnesotans," specifically targeting the operations of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The goal wasn't social media virality or public shaming in the traditional sense. Instead, Walz positioned the footage as evidence for future prosecution, imagining a moment when the courts would demand accountability for what he characterized as federal abuse of power, as reported by Minnesota Reformer.

This wasn't a casual moment of political theater. It represented something far more consequential: a state government deliberately positioning itself in direct opposition to federal authority, but through a lens that inverted the traditional surveillance state. Instead of the state surveilling citizens, citizens would surveil the state.

Meanwhile, Minnesota's legal team filed suit in federal court challenging what the Trump administration called "Operation Metro Surge," the deployment of approximately 2,000 armed ICE agents to the Twin Cities. The lawsuit wasn't a simple invocation of immigration law or federal-state relations. It was something more ambitious: a constitutional argument rooted in the Tenth Amendment, claiming that Minnesota and its municipalities possessed "inviolable sovereign authority" over their own borders, as detailed by KARE 11.

What unfolded in Minnesota became a test case for a much larger question facing the American system: How much authority can the federal government exercise within state boundaries, and what tools do states actually possess to push back when they believe the federal government has overstepped?

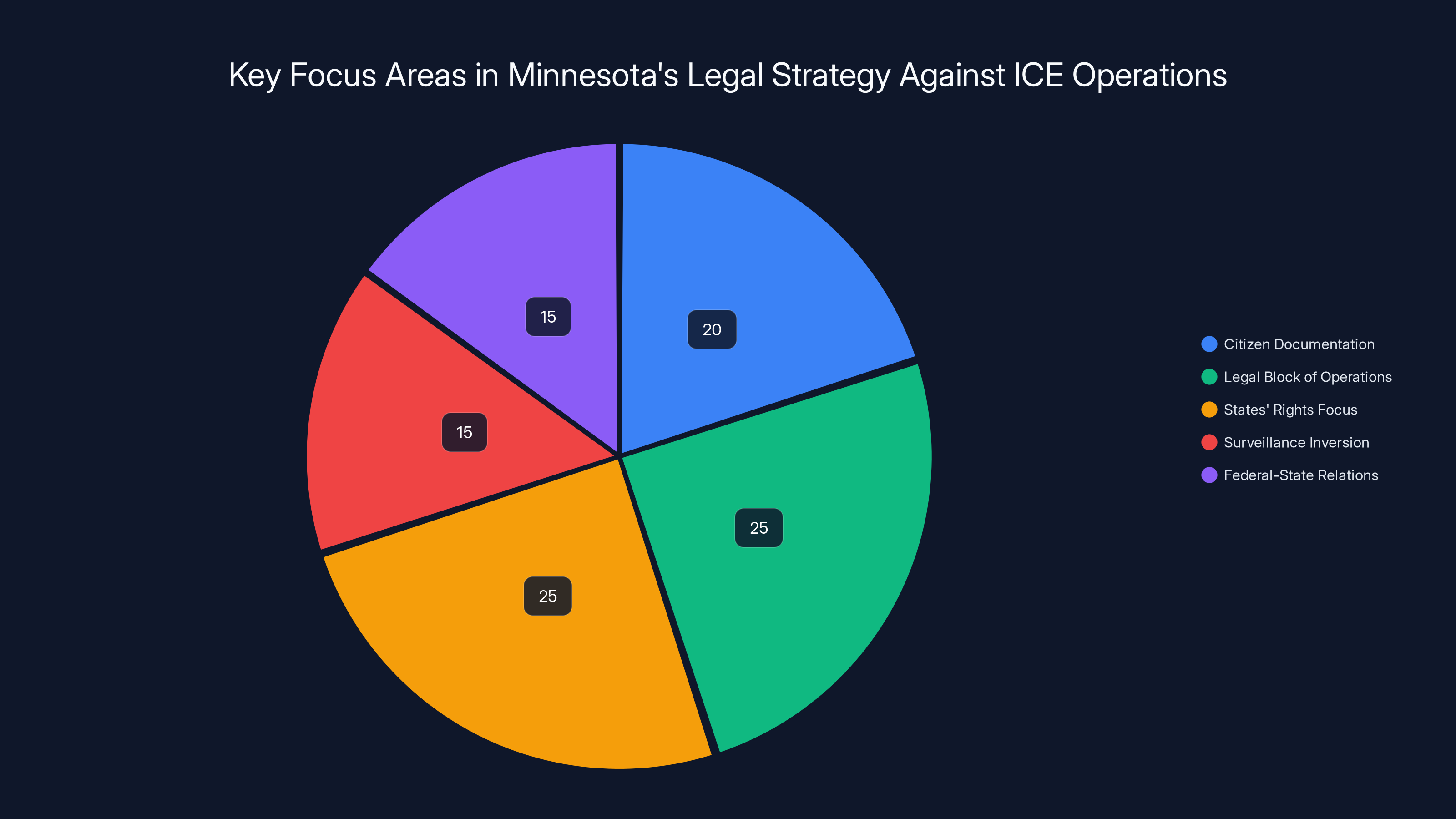

The answer that Minnesota crafted was unconventional. It combined legal challenge, political symbolism, and a direct appeal to citizens to become part of a documentation apparatus. It wasn't revolution. It wasn't even really civil disobedience in the traditional sense. Instead, it was a calculated strategy of attrition, using the tools available to a state government to make federal operations as difficult, costly, and legally vulnerable as possible.

Understanding what happened in Minnesota requires understanding the constitutional framework that governs federal-state relations, the specific legal arguments Minnesota deployed, the tactical implications of asking citizens to film federal agents, and the broader implications for how sanctuary policies might evolve in an era of aggressive federal immigration enforcement.

TL; DR

- Governor Walz asked Minnesotans to film ICE operations, framing citizen documentation as evidence for future prosecution and creating a database of federal actions

- Minnesota sued to block Operation Metro Surge, invoking the Tenth Amendment and claiming the state has inviolable sovereignty over activities within its borders

- The legal strategy focuses on states' rights, not immigration policy, arguing that federal agencies bypassed local authority and created a climate of fear

- Citizen surveillance of government represents an inversion of traditional surveillance state concerns, weaponizing documentation technology in favor of state-level constitutional claims

- The outcome could reshape federal-state relations around immigration enforcement and establish precedent for how aggressively states can resist federal operations

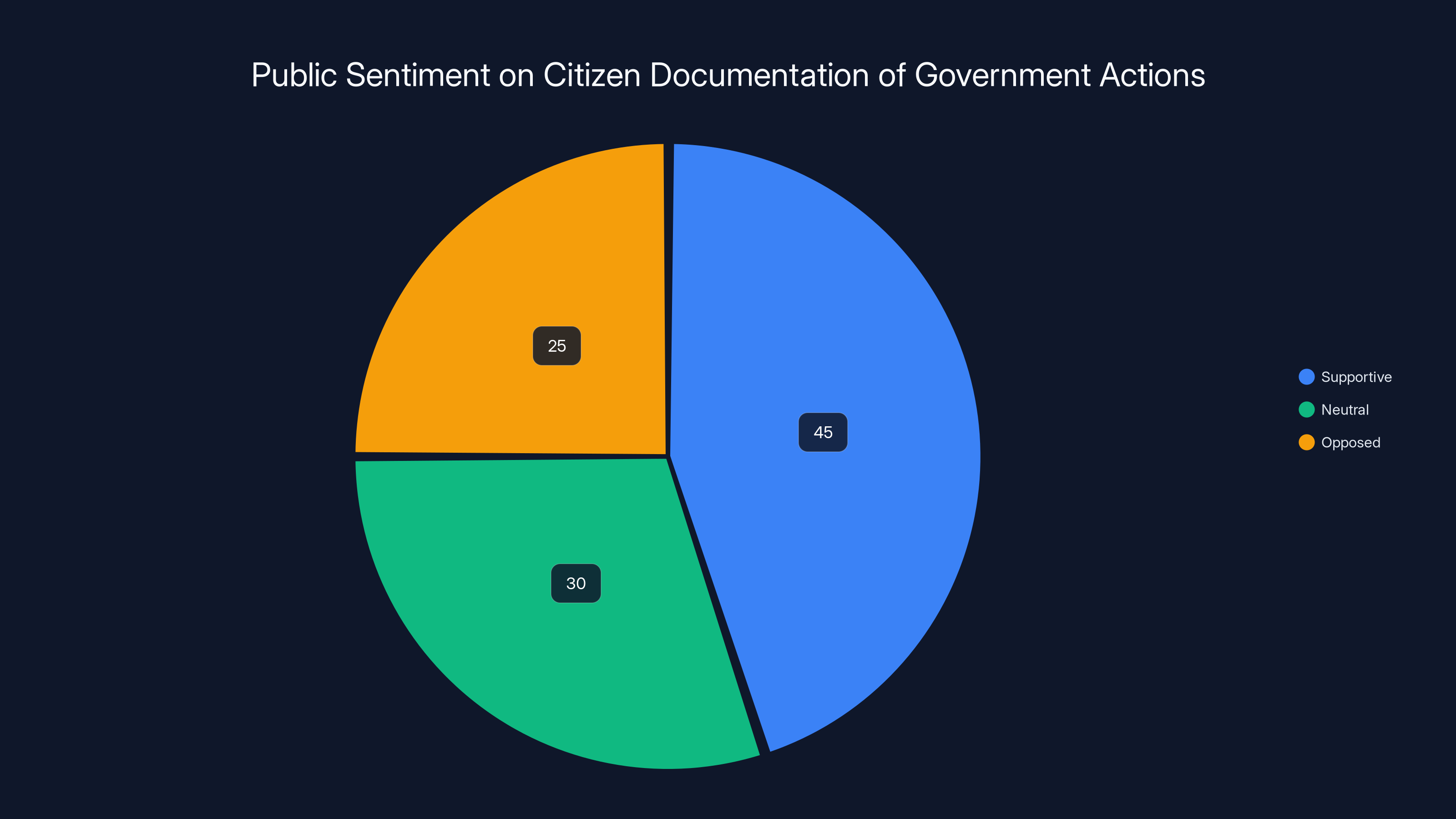

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of Minnesotans supported the initiative to document government actions, reflecting a shift in public trust and engagement.

The Constitutional Architecture of Federal-State Relations

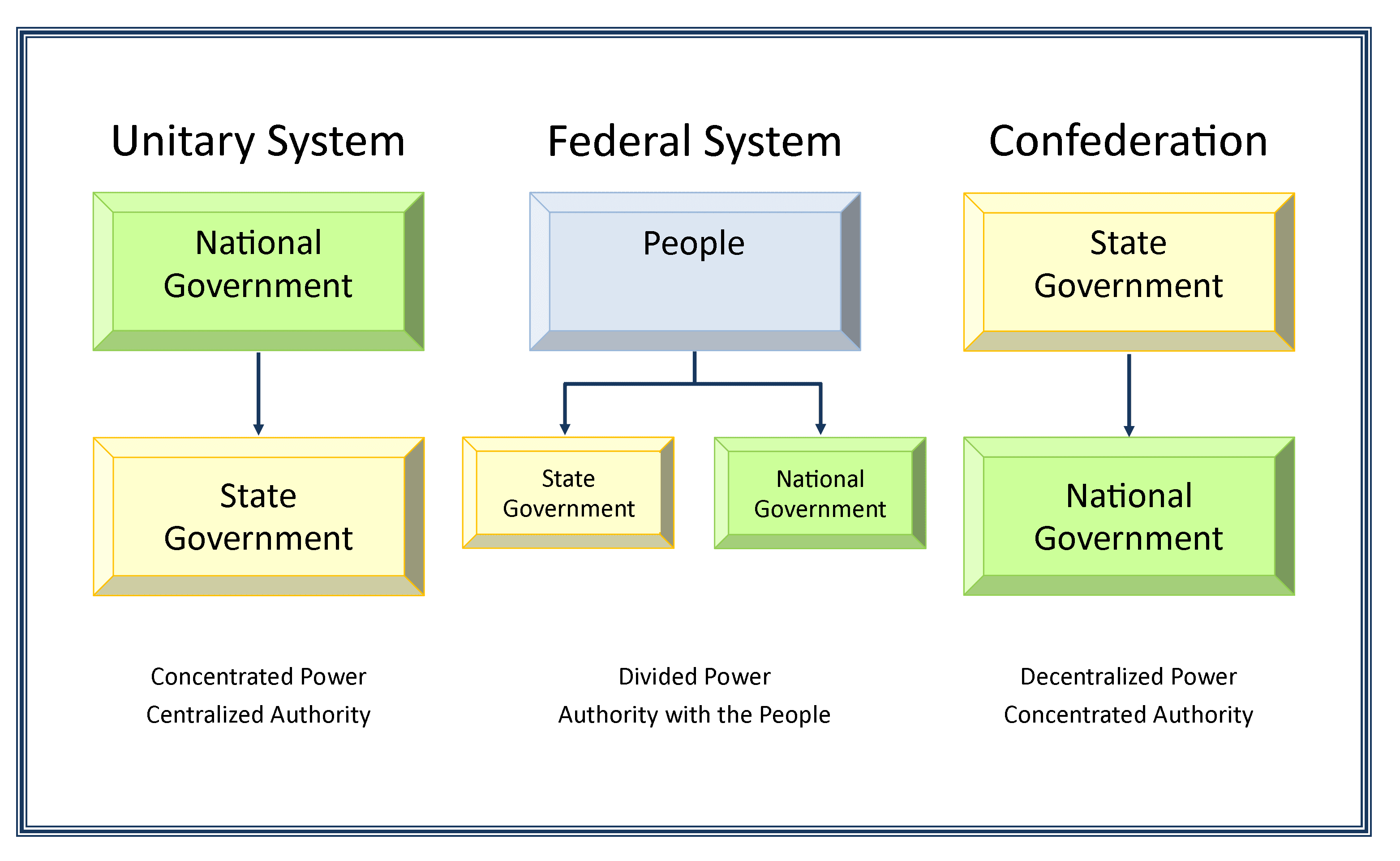

The American constitutional system was designed with deliberate ambiguity about federal versus state power. The Tenth Amendment reserves to the states "the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it." This single sentence has generated centuries of litigation, constitutional scholarship, and political conflict.

The question of immigration enforcement sits precisely in the constitutional gray zone. Immigration is unquestionably a federal power. The federal government controls borders, sets immigration policy, and determines who can enter or remain in the country. No state can nullify federal immigration law or prevent the federal government from enforcing it.

But that absolute federal power doesn't mean states are helpless. States maintain control over their own law enforcement agencies, their own criminal codes, and their own territories. When federal agents operate within a state, the state retains certain rights to know what's happening, to protect its residents from harm, and to ensure that federal actions don't interfere with state functions.

This is where the constitutional rubber meets the road. The tension between federal immigration authority and state sovereignty isn't theoretical. It plays out in practical questions: Can a federal agency conduct large-scale enforcement operations without notifying the governor? Can ICE agents surround a hospital or school without coordination with state authorities? Does the state have the right to refuse local police cooperation with federal agents?

Minnesota's lawsuit attempted to reframe these questions as not primarily about immigration policy, but about federalism itself. The argument was essentially: "You can enforce federal immigration law, but not in a way that invades the sovereign functions of the state."

This represents a doctrinal shift from how sanctuary cities typically argue these cases. Many sanctuary policies focus on prohibiting local police from assisting federal immigration enforcement, arguing that state resources shouldn't be deployed for federal purposes. Minnesota went further, arguing that the federal government had an affirmative obligation to respect state sovereignty in how it conducted its enforcement.

The Specific Allegations: Fear, Dysfunction, and Siege Tactics

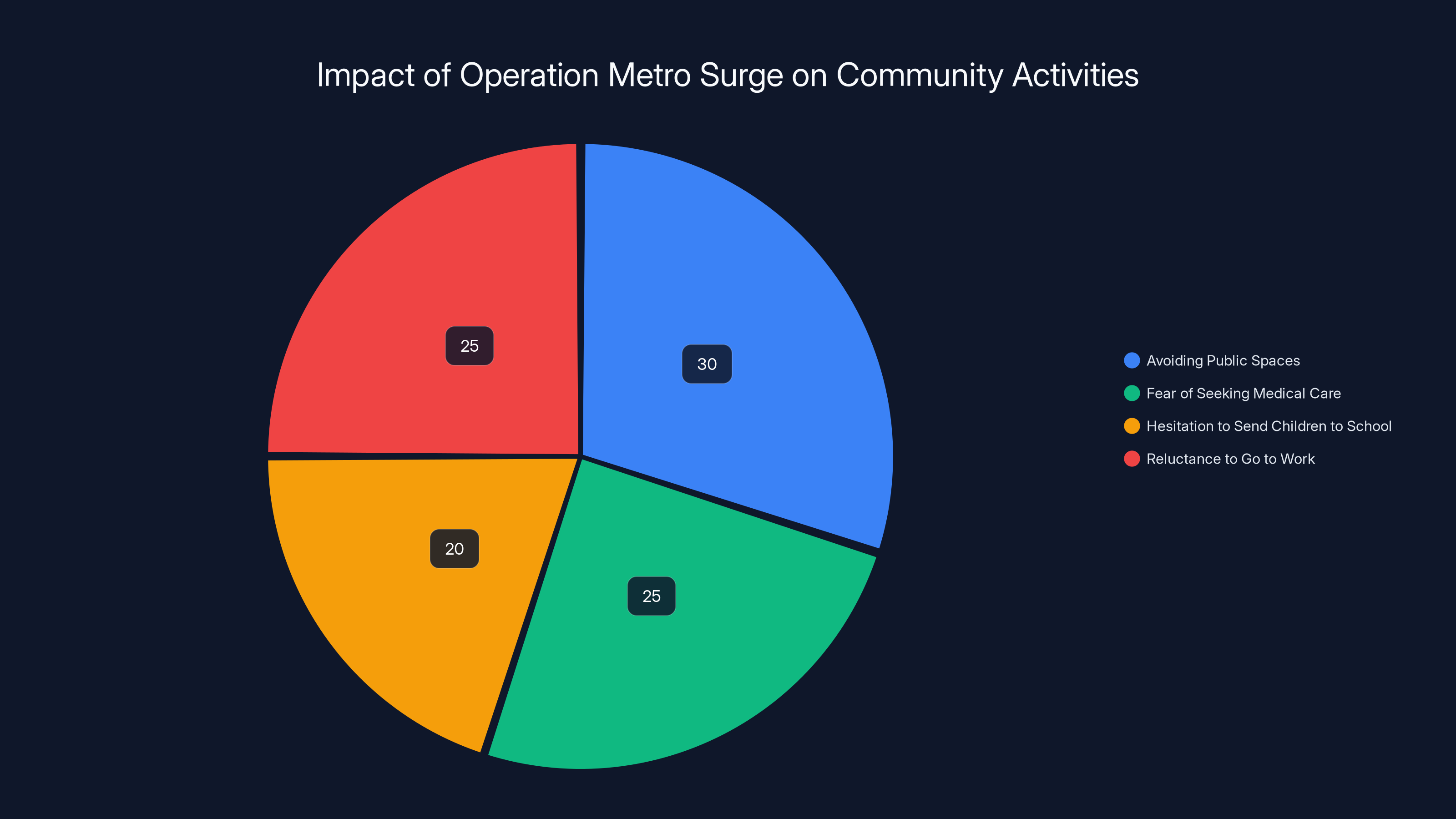

Minnesota's complaint against the Trump administration painted a vivid picture of federal overreach through specificity. The lawsuit didn't rely on abstract constitutional principles alone. Instead, it catalogued the concrete effects of Operation Metro Surge on Minnesota communities.

The ICE surge, according to the complaint, targeted hospitals, school bus stops, and retail locations. The state argued that this pattern wasn't accidental or necessary for effective immigration enforcement. Instead, it appeared deliberately designed to maximize fear and disruption. When federal agents in full combat armor suddenly appear at a school bus stop, the goal isn't purely administrative enforcement. It's intimidation, as noted by The Wall Street Journal.

Minnesota characterized the operation as creating "terror" among residents. This language is significant. The lawsuit moved beyond claiming that federal actions were procedurally improper or jurisdictionally overreaching. It argued that federal conduct was creating a pattern of harm to Minnesota residents specifically targeted because they reside in Minnesota.

The complaint also emphasized that the Trump administration had publicly complained about losing Minnesota in each of his presidential elections. This detail served a crucial rhetorical function. If the ICE surge was designed partially as political retaliation against a state that didn't support the president, it might constitute an abuse of federal power that violates constitutional protections against official action motivated by animus.

Further, Minnesota highlighted that similarly intensive ICE operations had been directed at Democratic-led cities like Los Angeles, Portland, and Chicago, all of which had Democratic mayors and sanctuary policies. This geographic pattern suggested to Minnesota's lawyers that the enforcement operations were politically selective, which could undermine their legitimacy.

The state also argued that the federal government had effectively paralyzed municipal governance. When the federal government unilaterally conducts large-scale law enforcement operations without coordination with local authorities, local government becomes unable to provide basic services. Police resources get diverted to managing the fallout. Public health and social services struggle to serve residents who are now afraid to interact with government. Schools see students absent because parents fear that their children might be subject to detention.

This argument framed federal action not as a legitimate exercise of federal immigration authority, but as an invasion of state sovereign territory. The state's core claim was straightforward: "You have the authority to enforce immigration law. You don't have the authority to conduct that enforcement in a way that destroys the state's ability to govern itself."

Sousveillance strategies are highly effective in creating political assets and evidence, with moderate effectiveness in deterrence. (Estimated data)

The National Guard Shadow Docket Decision: Trump's First Legal Setback

Understanding Minnesota's lawsuit requires understanding what happened just days before. In late December, the Supreme Court issued a shadow docket decision in cases challenging Trump's deployment of National Guard troops to various cities. The decision was significant because it was one of the rare instances in which the Supreme Court ruled against Trump in the early weeks of his administration.

Trump had attempted to deploy National Guard forces to conduct immigration enforcement in Chicago and Portland. The governors of those states objected, arguing that while the federal government could request National Guard assistance, it couldn't simply commandeer state military forces for federal purposes without state cooperation. The Supreme Court, in an unsigned decision, sided with the governors.

This decision was limited in scope. It didn't generally constrain Trump's ability to conduct immigration enforcement. But it did establish that even when federal goals are legitimate, federal agents can't simply override state sovereignty in executing those goals.

The Trump administration responded by announcing a "withdrawal" from Chicago and Portland, though critics argued that the withdrawal was more semantic than substantive. The administration simply shifted tactics, moving away from National Guard deployment and toward ICE operations.

Within days, the focus shifted to Minnesota. The timing was suggestive. Having lost in court on National Guard deployment, the administration chose a different tool to achieve similar effects: direct ICE operations conducted unilaterally, without National Guard involvement and therefore without triggering the same judicial questions.

But Minnesota's legal team saw continuity where the administration saw tactical adjustment. If the Supreme Court had said that federal officials couldn't simply override state sovereignty for National Guard operations, didn't the same principle apply to ICE operations? The state's lawsuit essentially argued that the Supreme Court's National Guard decision had broader implications than the administration was willing to acknowledge.

The Sousveillance Strategy: Inverting Surveillance Power

Governor Walz's call for Minnesotans to film ICE operations represented something conceptually significant: the deployment of sousveillance as a strategy of state resistance. Sousveillance is the practice of watching the watchers, of subordinates using cameras and documentation technology to monitor those in positions of power.

Traditionally, surveillance has been a tool of state power. The state monitors citizens for purposes of law enforcement, national security, and public administration. But Walz inverted this relationship. Instead of the state monitoring citizens, citizens would monitor the state, specifically monitoring federal agents acting within the state.

The strategic logic was threefold. First, documentation creates evidence. If federal agents violated law, if they engaged in excessive force, if they acted outside their authority, there would be a record. That record could be used in litigation, both at the state and federal level, to demonstrate patterns of abuse.

Second, documentation creates deterrence. Federal agents might be more cautious about how they conduct enforcement if they know they're being filmed. The risk of misconduct being captured on video and disseminated publicly increases the cost of aggressive tactics.

Third, documentation creates a political asset. Video evidence of federal agents in combat armor surrounding children at a school bus stop generates powerful imagery. That imagery can be deployed in political argument, in litigation, and in appeals to public opinion. It tells a story without relying on abstract constitutional claims.

Walz explicitly framed the documentation project in terms of future accountability. He invoked the Nuremberg trials, the post-World War II prosecutions of Nazi officials. The implication was clear: if federal officials were acting outside their authority and causing harm to Minnesota residents, there would be a reckoning. The videos would provide evidence for that reckoning.

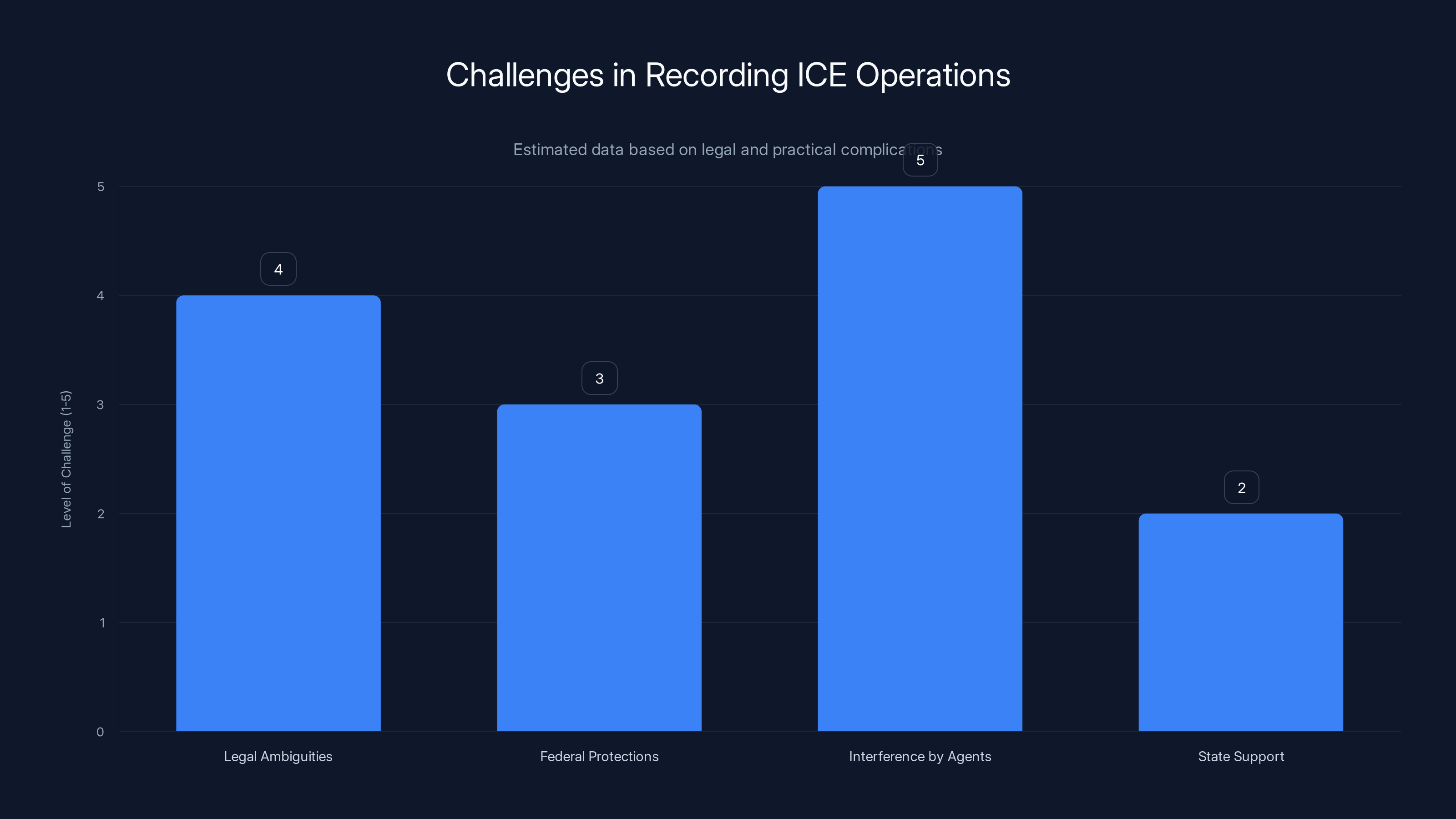

This strategy raised interesting questions about the legality of filming federal agents. In general, citizens have a right to record police and government officials performing their public duties in public spaces. However, federal law has sometimes been interpreted as providing greater protection to federal agents than to state and local police, particularly when national security is at stake. The question of whether citizens could legally film ICE operations, and whether they could do so without risk of federal interference, remained somewhat ambiguous.

But Walz's endorsement provided political cover. If the governor of Minnesota was explicitly asking citizens to film federal operations, and if the state was willing to defend that right in litigation, then ordinary citizens could participate in the documentation project with some confidence that the state would support them if federal authorities challenged the practice.

The Tenth Amendment Foundation: States' Rights in Federalism

Minnesota's lawsuit was explicitly grounded in the Tenth Amendment. The complaint opened with a direct invocation: "The Tenth Amendment gives the State of Minnesota and its subdivisions, including the Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, inviolable sovereign authority to protect the health and wellbeing of all those who reside, work, or visit within their borders."

This language is significant because it moves beyond negative rights (the state's right to not be commanded to enforce federal law) toward affirmative rights (the state's right to actively protect its residents from federal action). The Tenth Amendment is typically understood as a reservation of power: states retain powers not delegated to the federal government. Minnesota stretched this to claim that states retain sovereign authority to protect their residents from federal harm.

The legal question was whether federal immigration enforcement, when conducted in a particular manner and at a particular scale, violates the sovereign authority that the Tenth Amendment preserves. This is a harder legal claim than simply saying the state should have had notification or coordination opportunities. It's claiming that certain federal actions are unconstitutional precisely because they invade inviolable state sovereignty.

Courts have been reluctant to find federal actions unconstitutional on Tenth Amendment grounds, particularly when the federal government is exercising its clearly delegated powers. Immigration is unquestionably federal. So the question becomes whether the Tenth Amendment imposes any constraint on how the federal government exercises its immigration authority.

Minnesota's answer was yes, but with a specific limiting principle. The federal government can enforce immigration law. But it must do so in a way that respects the continuing sovereignty of the state. It cannot unilaterally conduct large-scale operations that effectively place a state under siege, that prevent state and local government from functioning, and that target residents in ways that suggest political motivation rather than neutral law enforcement.

This is a nuanced Tenth Amendment argument, and it's not clear how courts would evaluate it. Federal courts have been skeptical of Tenth Amendment claims when they seem to restrict federal exercise of clearly delegated powers. But the argument has some doctrinal support in cases establishing that states retain certain sovereign immunities and that federal actions cannot be structured in ways that commandeer or override state government.

The National Guard cases provided some precedent. If the federal government can't simply commandeer National Guard forces, can it completely circumvent state government in conducting large-scale law enforcement? That was Minnesota's essential question.

Estimated data suggests that interference by agents poses the highest challenge to citizens recording ICE operations, followed by legal ambiguities and federal protections.

Pattern and Practice: Why Minnesota and Why Now

One of the more compelling aspects of Minnesota's complaint was its documentation of why Minnesota had become a target. The state explicitly noted that Trump had complained about losing Minnesota in each of his presidential elections. The complaint also noted that other major ICE operations had been directed at Democratic-led sanctuary cities: Los Angeles, Portland, and Chicago.

This raised a crucial question about federal agency motivation. If ICE operations were being directed primarily at states and cities that had opposed Trump politically, did that suggest improper motivation? Could immigration enforcement be legitimate in its legal authority but unconstitutional in its actual motivation?

There's a line of constitutional law established in cases like Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp. that examines the motivational basis for government action. Even if an action is authorized by law, it can be unconstitutional if it's motivated by factors that shouldn't influence government decision-making, like race, religion, or political opposition.

Minnesota's argument seemed to hint at this possibility without quite going there. The complaint documented the political targeting without explicitly arguing that the ICE operations were unconstitutional because they were motivated by political animus. But the implication was present: if the Trump administration was deploying ICE operations selectively against Democratic states while leaving Republican states untouched, that pattern might indicate improper motivation that could taint the entire operation.

This argument had both strengths and weaknesses. The strength was that it documented a real pattern. ICE operations had indeed been more intensive in sanctuary cities and Democratic-led jurisdictions. The weakness was that there could be legitimate explanations for this pattern. Sanctuary cities have more restrictive immigration policies, which might justify more intensive federal enforcement to fill the gap left by state policy. Population density, immigration demographics, and other factors could explain geographic variation in enforcement intensity without requiring a finding of improper motivation.

But the pattern was suggestive enough to create legal vulnerability for the administration. If a court found that immigration enforcement had been partially motivated by political opposition to certain states, that would constitute a significant constitutional violation that could potentially invalidate the entire enforcement operation.

The Procedural Dimensions: Notice, Coordination, and Local Knowledge

Beyond constitutional theory, Minnesota's lawsuit raised practical questions about how federal law enforcement should coordinate with state and local authorities. These procedural questions might seem less dramatic than constitutional claims, but they can be equally important in litigation.

Minnesota argued that the federal government had effectively shut out state and local law enforcement from the planning and execution of Operation Metro Surge. This created multiple problems. First, it meant that local authorities couldn't provide valuable intelligence about community conditions, gang activity, and public safety risks that might affect how enforcement should be conducted. Second, it prevented local authorities from making preparations to maintain public services and safety during large-scale federal operations. Third, it eliminated opportunities for coordination that might make enforcement more effective while causing less collateral damage.

The argument was that even if the federal government has the authority to conduct enforcement unilaterally, good governance and constitutional respect for state sovereignty suggest that coordination is appropriate. And if coordination is appropriate, then deliberately excluding state authorities from coordination is problematic.

This is a relatively modest procedural claim compared to the sweeping Tenth Amendment argument. But it might be more likely to succeed in court. Federal courts might be reluctant to hold that federal immigration enforcement is unconstitutional simply because it makes a state unhappy. But federal courts might be more receptive to arguments that federal law enforcement should operate with some level of notice to and coordination with state authorities.

Further, the procedural argument creates opportunities for judicial remedies that don't require invalidating the entire enforcement operation. A court could order that future operations proceed with notice to state authorities, that local law enforcement be afforded opportunities to participate, or that procedures be established to prevent federal agents from unreasonably interfering with state and local functions. These are more modest remedies than shutting down immigration enforcement entirely, but they might be more achievable in litigation.

The Fear Factor: When Enforcement Becomes Intimidation

Minnesota's complaint characterized Operation Metro Surge as creating a climate of terror in Minnesota communities. This language might seem hyperbolic, but it reflected something real: a genuine change in the felt safety and security that Minnesota residents experienced.

When 2,000 armed federal agents in combat armor conduct large-scale operations at schools, hospitals, and public spaces, the effect extends far beyond those who are directly targeted by enforcement. It creates a chilling effect throughout immigrant communities. People become afraid to leave their homes, to seek medical care, to send children to school, or to go to work.

Minnesota argued that this effect wasn't incidental to enforcement; it was the apparent goal. If the administration genuinely wanted to enforce immigration law efficiently, it could target known enforcement priorities with precision. Instead, the mass operations at public locations created maximum visibility and maximum fear.

From a legal perspective, the question was whether this fear-generating effect violated the Tenth Amendment. Minnesota's argument was that the state has a sovereign right to ensure that its residents can safely participate in the basic functions of life: seeking healthcare, educating children, working. When federal law enforcement undermines that ability, it invades state sovereign authority.

This is a relatively novel legal argument. Federal courts haven't traditionally held that federal law enforcement violates the Tenth Amendment simply because it creates fear or disrupts the normal functioning of society. But in the context of post-2024 political conflict, courts might be more receptive to arguments that federal law enforcement has crossed from legitimate enforcement into something that more resembles persecution.

Minnesota's position was that there was a constitutional difference between enforcing immigration law and using immigration enforcement as a tool of political intimidation. Even if the administration had the legal authority to enforce immigration law, it exceeded that authority if it used enforcement as a mechanism for politically punishing states that opposed the president, as discussed in The New York Times.

Minnesota's strategy against ICE operations is multifaceted, with significant emphasis on states' rights and legal challenges. Estimated data.

Alternative Federal Theories: Due Process and Equal Protection

While the Tenth Amendment argument provided the framework for Minnesota's lawsuit, the complaint also invoked other constitutional theories that might provide alternative paths to relief. These included due process and equal protection arguments.

The due process argument rested on a relatively straightforward premise: Minnesotans have a due process right to know that federal agents won't conduct operations at hospitals or schools without some legal process. Due process requires that government action affecting individual rights follow certain procedural steps. If federal agents are conducting large-scale operations that affect the rights of Minnesota residents, due process might require notice, opportunity to be heard, and some form of judicial or administrative process.

Minnesota didn't argue that due process requires prior judicial approval for every federal law enforcement action. That would be extreme. But it argued that mass-scale operations conducted in ways clearly designed to maximize disruption and fear went beyond what due process permits, especially when the target appears to be political opponents of the administration rather than categories of people actually subject to immigration enforcement.

The equal protection argument rested on the observation that Democratic-led jurisdictions were being targeted more intensively than Republican-led jurisdictions. If federal enforcement resources were being allocated based on the political opposition of a state's leadership, that might constitute illegal discrimination. Equal protection doctrine generally forbids the government from treating similarly situated people differently based on suspect classifications like race, religion, or political opinion.

Of course, the Trump administration would argue that Democratic-led cities have sanctuary policies that prevent local cooperation with federal enforcement, which justifies more intensive federal operations. But Minnesota's response would be that this reasoning could justify more intensive federal action in any state that opposes federal policies, which would effectively give the federal government authority to invade any state that disagrees with it politically.

These alternative constitutional arguments provided additional angles of attack if the Tenth Amendment claim didn't succeed. They also provided political support for Minnesota's position by invoking broader constitutional principles about equal protection and due process rather than relying solely on federalism arguments.

The Broader Sanctuary Landscape: How Other States Positioned Themselves

Minnesota wasn't alone in resisting the Trump administration's immigration enforcement. Other Democratic-led states and cities initiated their own legal challenges, and the cumulative effect was significant.

California, New York, and Illinois all filed lawsuits challenging various aspects of federal immigration enforcement operations. These states had established sanctuary policies earlier, restricting the use of state and local law enforcement resources for federal immigration purposes. But the lawsuits represented a new escalation: states weren't just refusing to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement; they were affirmatively fighting in court against federal enforcement operations themselves.

Each state tailored its arguments to its particular circumstances and strengths. California emphasized its large immigrant population and the economic importance of immigrants to the state. New York emphasized the burden federal enforcement placed on state healthcare and social services. Illinois emphasized the violence and disorder that federal operations created in Chicago communities.

But all of these states shared a common framework: federal immigration enforcement is legitimate, but not when it's conducted in a way that invades state sovereignty, destroys the functioning of state government, or appears motivated by political opposition to the state.

This alignment suggested that a new constitutional doctrine around federal-state relations in immigration enforcement might be emerging. Federal government has clear immigration authority, but state governments retain certain sovereign prerogatives that federal authorities must respect. The specific dimensions of that relationship might be worked out through litigation as courts evaluated the various state challenges.

The cumulative effect of multiple state challenges was significant. If courts sided with even a few of the states, it would create constraints on federal immigration enforcement that would be difficult for the administration to overcome. Conversely, if courts sided with the federal government on all fronts, it would establish clear precedent that federal immigration enforcement authority essentially trumps state sovereignty, at least in contexts where federal officials claim immigration authority.

The Litigation Strategy: Where the Case Might Go

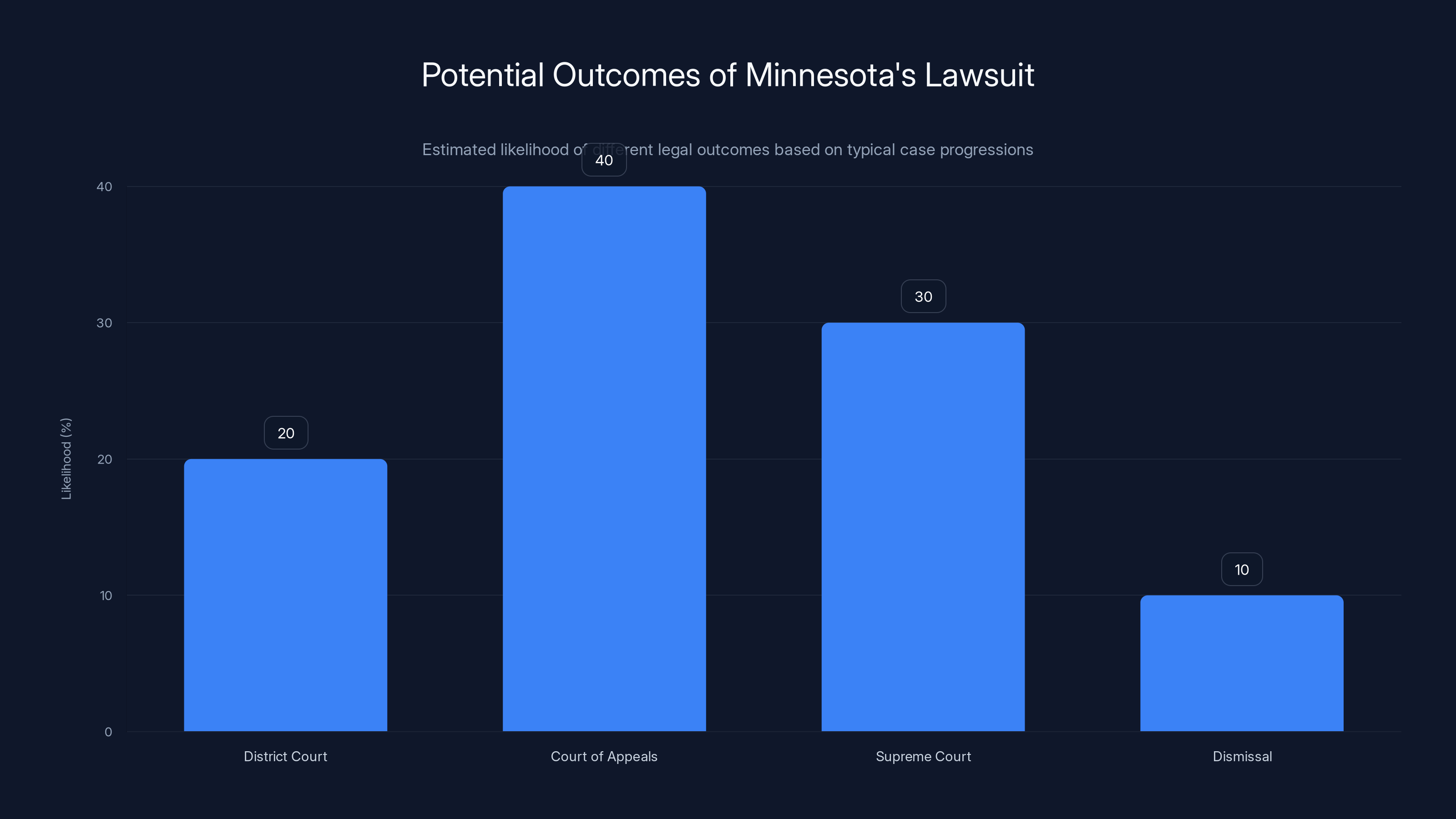

Minnesota's lawsuit was filed in federal district court, but everyone understood that the ultimate resolution would likely come from the Court of Appeals and possibly the Supreme Court. The constitutional questions were too significant and the political stakes too high for the case to remain in the district court system.

The first question would be whether Minnesota even had standing to sue. This is a technical doctrine issue, but it matters. The federal courts ask whether a plaintiff has suffered a concrete injury that the courts can remedy. Did Minnesota, as a state, suffer an injury from federal immigration enforcement operations? Or did only individual residents suffer injury, and only those individual residents could sue?

This question has important implications. If only individual residents can sue for injuries from federal enforcement, then there's no unified state lawsuit. Instead, there would be many individual lawsuits brought by affected residents. These would be harder to coordinate and might receive less media attention and political support. But if the state itself can sue for injuries to its sovereign interests, then the state can speak with a unified voice in defending the rights of all its residents.

There are good arguments on both sides. Federal courts have allowed states to sue to defend state interests and state sovereignty. The National Guard cases, for instance, involved state officials suing to defend state authority over state military forces. But immigration is different from National Guard authority. Immigration is unmistakably a federal power, and states don't have independent immigration authority to defend.

Assuming Minnesota survived the standing question, the next major issue would be the merits of the Tenth Amendment claim. Would a federal court hold that the Tenth Amendment constrains how the federal government can exercise its immigration authority? This is uncharted territory. Federal courts have generally been reluctant to find that the Tenth Amendment constrains federal exercise of clearly delegated powers. But times and judicial composition change, and the constitutional claims presented by Minnesota's litigation were novel and compelling.

If Minnesota lost on the merits, it could appeal to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. If the case involved sufficiently important constitutional questions, it might reach the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court had recently shown willingness to limit federal power in the National Guard cases, suggesting that the current Court might be receptive to federalism arguments.

Conversely, if Minnesota prevailed in district court, the Trump administration would almost certainly appeal, and the case would go through the appellate process. The administration had strong incentives to overturn any district court decision constraining its immigration enforcement authority.

Operation Metro Surge reportedly caused significant fear, leading to avoidance of public spaces and essential activities. Estimated data based on community feedback.

The Politics of States' Rights: An Ironic Reversal

There was an ironic dimension to Minnesota's states' rights argument. Historically, states' rights have been invoked to resist federal enforcement of civil rights and desegregation. Southern states claimed states' rights when federal courts tried to enforce racial integration. Conservatives invoked states' rights to resist federal regulation.

Now, a Democratic-led state was invoking states' rights to resist what it characterized as federal tyranny. The political alignment had reversed, but the underlying constitutional principle remained: sometimes states have legitimate reasons to assert their sovereignty against federal overreach.

This inversion was significant because it suggested that states' rights doctrine might have broader application than purely conservative invocations. If states could claim sovereignty to resist federal enforcement of civil rights, could they equally claim sovereignty to resist federal enforcement of immigration law? The constitutional logic suggested yes, though the political implications would be contentious.

For Republican-led states that had traditionally emphasized states' rights, Minnesota's argument posed a dilemma. Some Republican leaders recognized that if federal immigration enforcement could override state sovereignty, then federal environmental or healthcare enforcement could do the same. States' rights should work both ways. Other Republican leaders, however, saw immigration enforcement as uniquely important and were willing to support federal authority in this domain even if it meant compromising broader federalism principles.

This internal Republican division reflected deeper tensions in conservative political thought about federal power, immigration, and states' rights. These tensions would likely play out in the litigation and in the political response to judicial decisions.

Practical Implications: How Immigration Enforcement Might Change

If Minnesota's litigation succeeded, either fully or partially, it would change how immigration enforcement could be conducted. At minimum, it might require that federal agencies provide notice to state authorities before conducting large-scale operations. It might require that federal agencies coordinate with local authorities and take into account local law enforcement needs and public safety concerns.

It might also constrain where federal agents could conduct enforcement. If federal operations at schools and hospitals were found to violate state sovereignty or to create unconstitutional fear, then federal agencies would need to find alternative enforcement strategies that didn't involve operations at sensitive locations.

These constraints wouldn't eliminate federal immigration enforcement. They would simply make it harder, more cumbersome, and requiring more coordination with state authorities. For the Trump administration, this would mean that aggressive immigration enforcement would require more cooperation from state and local authorities, including Democratic-led states that opposed the administration's policies.

From Minnesota's perspective, this was the desired outcome. Not to eliminate immigration enforcement, but to ensure that it was conducted in ways that respected state sovereignty and didn't create a climate of terror in Minnesota communities.

If Minnesota's litigation failed, the implications would be equally significant in the opposite direction. It would establish that federal immigration authority essentially trumps state sovereignty, that states have no meaningful ability to constrain how federal agents conduct enforcement within state boundaries, and that the Trump administration could conduct immigration enforcement operations as intensively as it wished without regard to state objections or state sovereignty.

The Citizen Documentation Project: Legal and Practical Complications

Governor Walz's call for Minnesotans to film ICE operations raised its own set of legal and practical complications. While citizens generally have a right to record police and government officials in public, federal law creates some ambiguities.

First, there's the question of whether citizens can legally record ICE agents. ICE is a federal agency, and federal law provides some protections to federal agents that don't apply to state and local police. In particular, federal law prohibits the transmission of certain information about federal agent operations, and there are some restrictions on photographing federal buildings and facilities. The question of whether these restrictions apply to ordinary citizens filming ICE agents in public wasn't entirely clear.

Second, there's the practical reality that federal agents, like police officers, might try to interfere with citizen recording, even if such interference is legally improper. If a citizen tried to film ICE operations and a federal agent ordered them to stop, demanded they delete the footage, or even arrested them, the citizen would need to be willing to fight that in court later. Not everyone has the resources, legal knowledge, or courage to stand up to federal agents in the moment, even if standing up would be legally correct.

Governor Walz's public endorsement of the documentation project provided some protection against this risk. If the state government had officially asked citizens to document federal operations, then the state might be willing to defend citizens in litigation if federal authorities tried to stop them from recording. The state could file motions to suppress evidence obtained through unconstitutional seizures of recordings, could file amicus briefs in criminal cases against citizens who were prosecuted for recording, or could initiate civil litigation against federal agents who violated citizens' recording rights.

This is where the sousveillance project became more than just symbolic. It became a mechanism for distributing the burden of resistance. Instead of relying solely on state government litigation, the governor mobilized ordinary citizens to become part of the resistance apparatus. Citizens became documentarians of federal overreach, and the state government committed to supporting them legally.

Of course, this strategy had risks. If federal authorities decided to aggressively prosecute citizens who recorded ICE operations, they could create a chilling effect that would discourage future recording despite the governor's endorsement. Citizens wouldn't want to risk federal prosecution even with the promise of state legal support.

But the documentation project also created potential political costs for the administration if it tried to prosecute citizens for recording. A prosecution of a Minnesota citizen for filming federal agents in public spaces would generate intense political opposition and would undermine the administration's claim to be operating within legal boundaries. It would look like authoritarian suppression of free speech.

Estimated data suggests the case is most likely to progress to the Court of Appeals, with a significant chance of reaching the Supreme Court. Dismissal is less likely.

Long-Term Constitutional Implications: Federalism for the 21st Century

Minnesota's litigation represented part of a broader reconfiguration of American federalism. For decades, federalism has been understood primarily through the lens of federal power to regulate interstate commerce, environmental protection, and civil rights enforcement. Federal power has generally expanded, and state sovereignty has been correspondingly constrained.

But immigration enforcement raises different federalism questions because immigration is clearly federal, but its effects are local. When federal agents conduct enforcement operations within state boundaries, state interests are directly affected. The question of how to balance federal immigration authority with state sovereignty isn't settled in existing constitutional law.

Minnesota's lawsuit suggested one possible framework: federal authority is supreme in its domain, but state sovereignty constrains how federal authority can be exercised. The federal government can't conduct enforcement in ways that effectively place a state under siege or that invade the core sovereign functions of state government.

This framework, if accepted by courts, would apply beyond immigration. It could constrain federal law enforcement operations more broadly, federal environmental enforcement, federal tax enforcement, and any domain where federal and state authority intersect. It could establish that there are limits to how aggressively federal agencies can exercise federal authority within state boundaries without regard to state sovereignty.

Alternatively, courts might reject Minnesota's framework and hold that federal immigration authority is essentially absolute, that states have no meaningful ability to constrain federal immigration enforcement, and that the federal government can conduct enforcement as intensively as it wishes. This would establish clear federal supremacy in the immigration domain.

The outcome of Minnesota's litigation would likely establish a template for how federal-state relations around enforcement would be governed for the foreseeable future. If courts sided with Minnesota, it would validate a new federalism doctrine. If courts sided with the Trump administration, it would clarify the limits of state sovereignty in the face of federal enforcement authority.

International Dimensions: How Other Democratic Nations Handle Federal-State Immigration Enforcement

While American constitutional law is unique, it's instructive to consider how other federal democracies handle the tension between national immigration authority and state or provincial sovereignty.

Canada has a federal system where immigration is primarily federal jurisdiction. However, Quebec has negotiated special immigration powers that allow the province to select its own immigration applicants within the federal system. This represents a compromise between federal authority and provincial interest in shaping immigration patterns.

Australia similarly has federal immigration authority, but Australian states have maintained the ability to set conditions on how federal immigration enforcement operates within state territory. States can require notification and coordination with state authorities before major enforcement operations.

Germany's federal system gives substantial authority to Länder (states) over police and law enforcement within their territories. While immigration is federal, the enforcement of immigration law often involves state police, which means state governments have leverage to shape how enforcement is conducted.

These international examples suggest that there are models for balancing federal immigration authority with state sovereignty. Federal government retains ultimate authority over immigration policy, but state governments retain meaningful ability to constrain how federal authority is exercised within state territory.

Minnesota's lawsuit could be understood as reaching for a similar balance. Not denying federal immigration authority, but insisting that such authority be exercised in ways that respect state sovereignty and involve state government coordination.

The Media and Public Opinion Dimensions

Minnesota's litigation took place in a intense media environment. The call for citizen documentation of federal operations, the claims of federal overreach, and the broader conflict between the Trump administration and Democratic-led states received significant media coverage.

This media environment affected both the litigation and the political stakes. Media coverage of ICE operations at schools and hospitals generated public concern about federal conduct. Photos and videos of armed federal agents in combat armor became powerful symbols of federal overreach. The state's framing of the issue as a matter of states' rights and constitutional governance shaped public understanding of what was at stake.

Media coverage also affected the administration's incentives. If federal conduct was being documented and criticized in the media, the administration faced pressure to either constrain its operations or justify them more effectively. The administration's communication strategy would need to address concerns about federal overreach and explain why intensive immigration enforcement operations in Minnesota were necessary and appropriate.

The citizen documentation project was partially a media strategy. By asking Minnesotans to film federal operations, Walz was ensuring that there would be video evidence of what federal agents were doing. That video evidence could be disseminated through social media, news outlets, and political communications. It would shape public perception of federal conduct.

Conversely, the administration had incentives to limit documentation. If federal operations were being constantly filmed and the footage disseminated publicly, it would undermine the administration's framing of its actions. The administration might try to discourage citizen recording, might conduct operations in ways less susceptible to documentation, or might conduct significant portions of enforcement operations in ways less visible to public observation.

This dynamic between the state's documentation strategy and the administration's incentives to limit visibility created an ongoing tension that would play out throughout the litigation and the enforcement operations themselves.

Alternative Legal Theories and Future Developments

Beyond the specific claims Minnesota raised, there were other potential legal theories that might be developed in future litigation. These included theories based on constitutional restrictions on bills of attainder (laws punishing specific individuals or groups without trial), theories based on the right to travel, and theories based on the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Each of these theories would require Minnesota to frame the litigation differently, but they all pointed toward a common principle: federal power, even when clearly delegated to the federal government, has constitutional limits. It can't be exercised in ways that cross into unconstitutional punishment, that interfere with constitutional rights to travel and freedom of movement, or that conduct searches and seizures without constitutional warrant.

Future litigation might develop one or more of these alternative theories as courts became more familiar with the substantive issues raised by intensive federal immigration enforcement in states opposed to federal policies.

The Unresolved Question: What Does Federal Supremacy Actually Mean?

Underlying Minnesota's lawsuit and the broader federal-state conflict over immigration was a fundamental constitutional question about what federal supremacy means. The Supremacy Clause of the Constitution states that federal law is the supreme law of the land. But what does that actually mean for federal law enforcement operations?

One interpretation is that federal supremacy means federal law prevails in case of conflict, but it doesn't necessarily mean federal agencies can conduct operations however they wish within state territory. Federal supremacy could be understood as supremacy over the substance of law, not necessarily supremacy over the processes and procedures by which federal authority is exercised.

Another interpretation is that federal supremacy means federal authority is essentially unlimited within the federal government's delegated domains. Immigration is federal, so the federal government can conduct immigration enforcement however it wishes, without constraint from state government.

Minnesota's lawsuit rested on the first interpretation. The Trump administration would presumably argue for the second.

This is ultimately a question about how to reconcile federal authority with federalism, how to understand the balance between the Supremacy Clause and the Tenth Amendment, and what it means to live in a federal system where power is divided between national and state governments.

The Stakes for Democratic Governance and Federal-State Relations

The outcome of Minnesota's litigation would have implications extending far beyond immigration enforcement. It would establish principles about how the federal government can exercise its authority in ways that affect state interests, how states can challenge federal action, and what it means to maintain a federal system where power is genuinely divided between national and state governments.

If courts sided with Minnesota, it would validate a model where federal authority is constrained by federalism principles, where states retain meaningful ability to protect their residents from federal overreach, and where federal agencies must operate with some consideration for state sovereignty and state interests.

If courts sided with the Trump administration, it would establish that federal authority essentially trumps state sovereignty in domains where the federal government has clear constitutional authority. It would mean that states and cities opposed to federal policies have limited tools to constrain federal enforcement operations.

This choice between models of federalism would shape American governance for years or decades to come. It would affect not just immigration enforcement, but federal regulation more broadly, federal law enforcement, and the practical balance of power between national and state governments.

Conclusion: A War of Attrition in American Federalism

Governor Walz's invocation of a "war of attrition" captured something true about the strategy Minnesota adopted. The state wasn't trying to eliminate federal immigration authority. It was trying to make that authority harder, more expensive, more legally vulnerable, and more politically costly to exercise.

The documentation project served this strategy by creating evidence of federal conduct, evidence that could be used in litigation and in public argument. The lawsuit served this strategy by raising constitutional questions about federal authority and state sovereignty. The combination of litigation, documentation, political communication, and media engagement created a comprehensive resistance strategy that aimed to change the costs and benefits of aggressive federal immigration enforcement.

It's not clear whether this strategy would ultimately succeed. Courts might side with Minnesota, or they might side with the Trump administration. Media coverage might pressure the administration to moderate its enforcement operations, or the administration might press forward regardless of media criticism.

But what was clear was that Minnesota had identified a framework for understanding the federal-state conflict over immigration enforcement, had mobilized legal, political, and popular resources to challenge that enforcement, and had framed the issue in constitutional terms that resonated with broader American concerns about federal power and state sovereignty.

The litigation would unfold over months or years. The documentation project would continue as long as citizens were willing to film federal operations. The political communication would escalate as the 2025-2026 period unfolded. The broader question about how federal and state power should be balanced in a federal system would gradually work its way through courts, legislatures, and public opinion.

What Minnesota demonstrated was that despite federal supremacy in immigration, states and cities opposed to federal policies had more tools available than simple non-cooperation. They could sue, they could mobilize their residents, they could generate evidence of federal overreach, and they could frame federal conduct in constitutional and human rights terms that challenged its legitimacy.

Whether these tools would prove sufficient to constrain federal enforcement or whether federal authority would ultimately prevail would depend on judges, juries, and public opinion. But Minnesota had clearly demonstrated that the relationship between federal immigration authority and state sovereignty was not settled, that the legal arguments were substantial, and that the stakes for American federalism extended far beyond the specific question of ice enforcement in the Twin Cities.

The state's approach—combining litigation, citizen participation, public symbolism, and constitutional argument—represented a model for how political communities opposed to federal policies could mobilize resistance. Whether similar strategies would emerge in other domains of federal-state conflict remained to be seen. But Minnesota had shown that the constitutional foundations of American federalism were active battlegrounds where fundamental questions about federal power, state sovereignty, and democratic governance were still being contested and decided.

FAQ

What is Operation Metro Surge?

Operation Metro Surge refers to the Trump administration's deployment of approximately 2,000 armed ICE agents to the Twin Cities area of Minnesota. The operation was announced as an intensive immigration enforcement initiative targeting undocumented immigrants in Minnesota communities, but critics argued it was broader in scope and effect than standard immigration enforcement, including operations at schools, hospitals, and public spaces.

Why did Minnesota sue the Trump administration over ICE operations?

Minnesota sued claiming that the federal government violated the state's Tenth Amendment rights by conducting large-scale law enforcement operations without state coordination or notification, creating a climate of fear among residents, and potentially targeting the state for political reasons. The state argued that while the federal government has immigration authority, it must exercise that authority in ways that respect state sovereignty and don't prevent the state from governing itself.

What is sousveillance and how did Governor Walz use it as a strategy?

Sousveillance is the practice of using cameras and documentation technology to watch and record those in positions of power. Governor Walz asked Minnesota citizens to film ICE operations as a way to create evidence of federal conduct, deter federal overreach through the risk of public exposure, and document potential federal violations for use in future litigation and prosecution. This inverted the traditional surveillance dynamic where the state monitors citizens.

What is the Tenth Amendment and how does it apply to immigration enforcement?

The Tenth Amendment reserves to the states the powers not delegated to the federal government. While immigration is clearly a federal power, Minnesota argued that the Tenth Amendment still preserves state sovereignty and prevents the federal government from conducting immigration enforcement in ways that effectively place a state under siege or prevent the state from fulfilling its core functions of protecting resident safety and providing basic services.

How does Minnesota's legal strategy differ from typical sanctuary city policies?

Traditional sanctuary policies prohibit local police from assisting federal immigration enforcement. Minnesota went further, arguing that the federal government itself has an affirmative constitutional obligation to respect state sovereignty in how it conducts enforcement. The state didn't just refuse to cooperate with federal enforcement; it affirmatively challenged federal enforcement operations as violating state constitutional rights.

Could Minnesota's lawsuit succeed and what would victory look like?

Minnesota's lawsuit faces significant legal obstacles since immigration is clearly federal jurisdiction. However, if successful, it could establish that federal immigration enforcement must proceed with state coordination, cannot occur at sensitive locations like schools and hospitals, and cannot be motivated by political opposition to the state. Victory would likely involve a court order requiring federal agencies to notify state authorities, coordinate operations, and avoid creating conditions of terror in the community.

What happened with the Supreme Court's National Guard decision and how does it relate to Minnesota?

The Supreme Court ruled that the Trump administration couldn't simply commandeer National Guard forces for immigration enforcement without state cooperation. Minnesota's lawsuit extended this logic, arguing that if the federal government can't unilaterally deploy National Guard forces, it similarly can't unilaterally conduct large-scale ICE operations that effectively place a state under siege without respecting state sovereignty.

Do citizens have a legal right to film ICE agents?

Citizens generally have a constitutional right to record police and government officials performing their duties in public spaces. However, there are some ambiguities regarding federal agents and potential restrictions under federal law. Governor Walz's public endorsement of citizen documentation provided political cover and a commitment that the state would defend citizens legally if federal authorities tried to stop them from recording.

How does this conflict reflect broader tensions in American federalism?

The Minnesota case represents a fundamental tension in the American federal system between federal supremacy in delegated domains like immigration and state sovereignty preserved by the Tenth Amendment. It raises the question of whether federal authority is essentially unlimited within federal jurisdiction, or whether federalism principles constrain how aggressively federal agencies can exercise their authority within state boundaries.

What are the implications if the federal government prevails in this litigation?

If the Trump administration prevails, it would establish that federal immigration authority is essentially unconstrained by federalism principles, that states have no meaningful ability to protect their residents from federal enforcement operations, and that the federal government can conduct immigration enforcement as intensively as it wishes regardless of state objections or the effects on state governance.

Key Takeaways

- Minnesota invoked the Tenth Amendment to argue that federal immigration enforcement violated state sovereignty when conducted without coordination with state authorities and in ways that created terror among residents

- Governor Walz's call for citizen documentation of ICE operations represented sousveillance, inverting traditional surveillance power by asking residents to record federal agents as evidence for future prosecution

- The lawsuit was strategically filed after the Supreme Court limited Trump's authority to deploy National Guard forces without state cooperation, suggesting similar federalism constraints should apply to unilateral ICE operations

- Operation Metro Surge targeted Democratic-led sanctuary cities including Minnesota, Los Angeles, Portland, and Chicago, a pattern Minnesota cited as evidence of politically motivated enforcement rather than neutral immigration policy

- The litigation outcome will establish whether federal immigration authority essentially trumps state sovereignty, or whether federalism principles constrain how aggressively federal agencies can conduct enforcement within state boundaries

![Minnesota's ICE Sousveillance Strategy: States' Rights vs. Federal Power [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/minnesota-s-ice-sousveillance-strategy-states-rights-vs-fede/image-1-1768660612150.jpg)