Introduction: The Year Selectivity Took Over India's Startup Scene

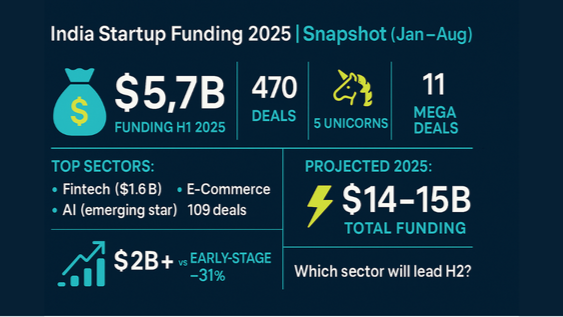

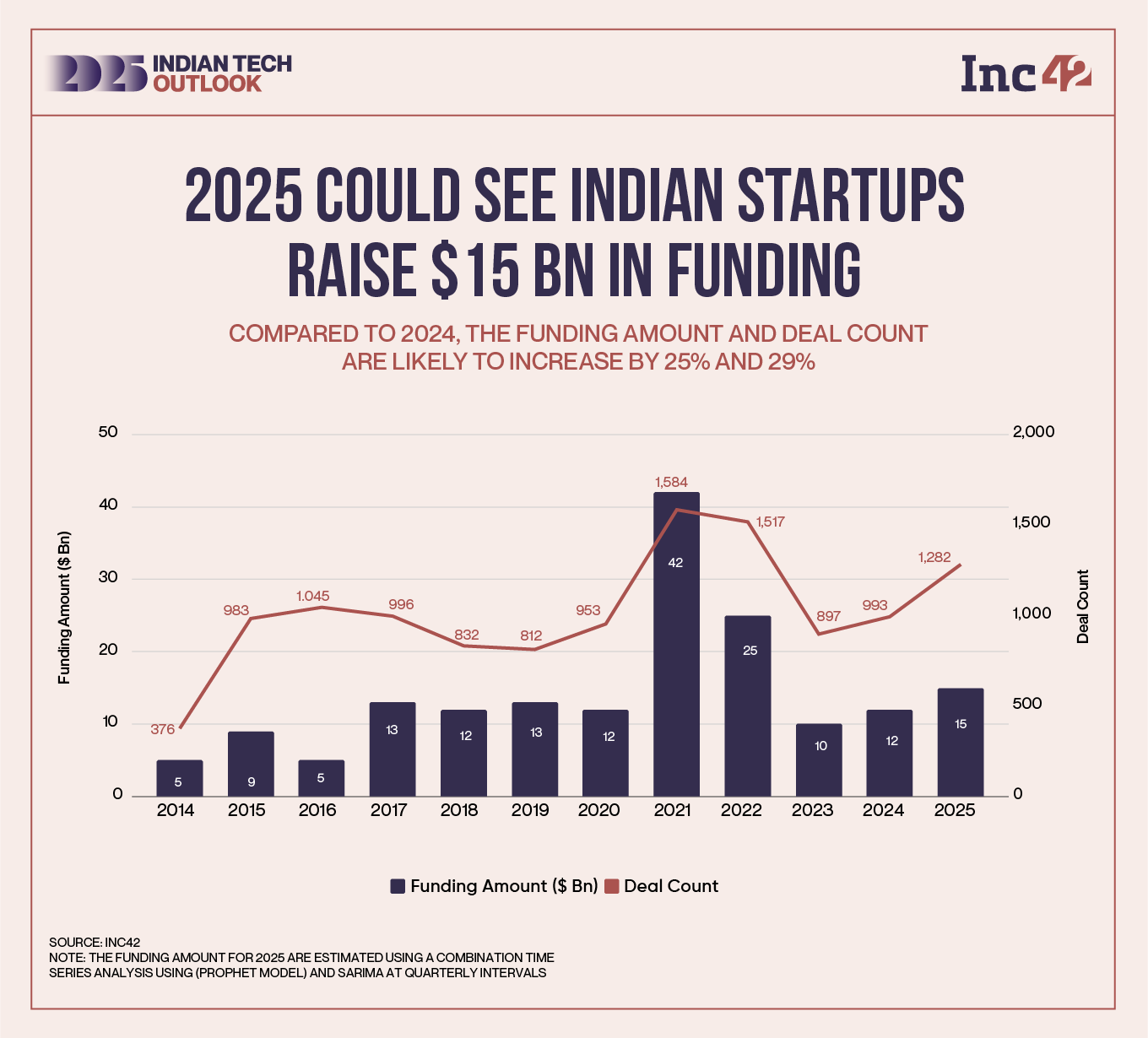

India's startup funding story in 2025 reads like a plot twist nobody saw coming. On the surface, the numbers look okay—nearly $11 billion deployed across the world's third most-funded startup market. But zoom in, and you'll see something shifted fundamentally. Investors stopped writing checks to everyone with a pitch deck. They got ruthless about where capital went.

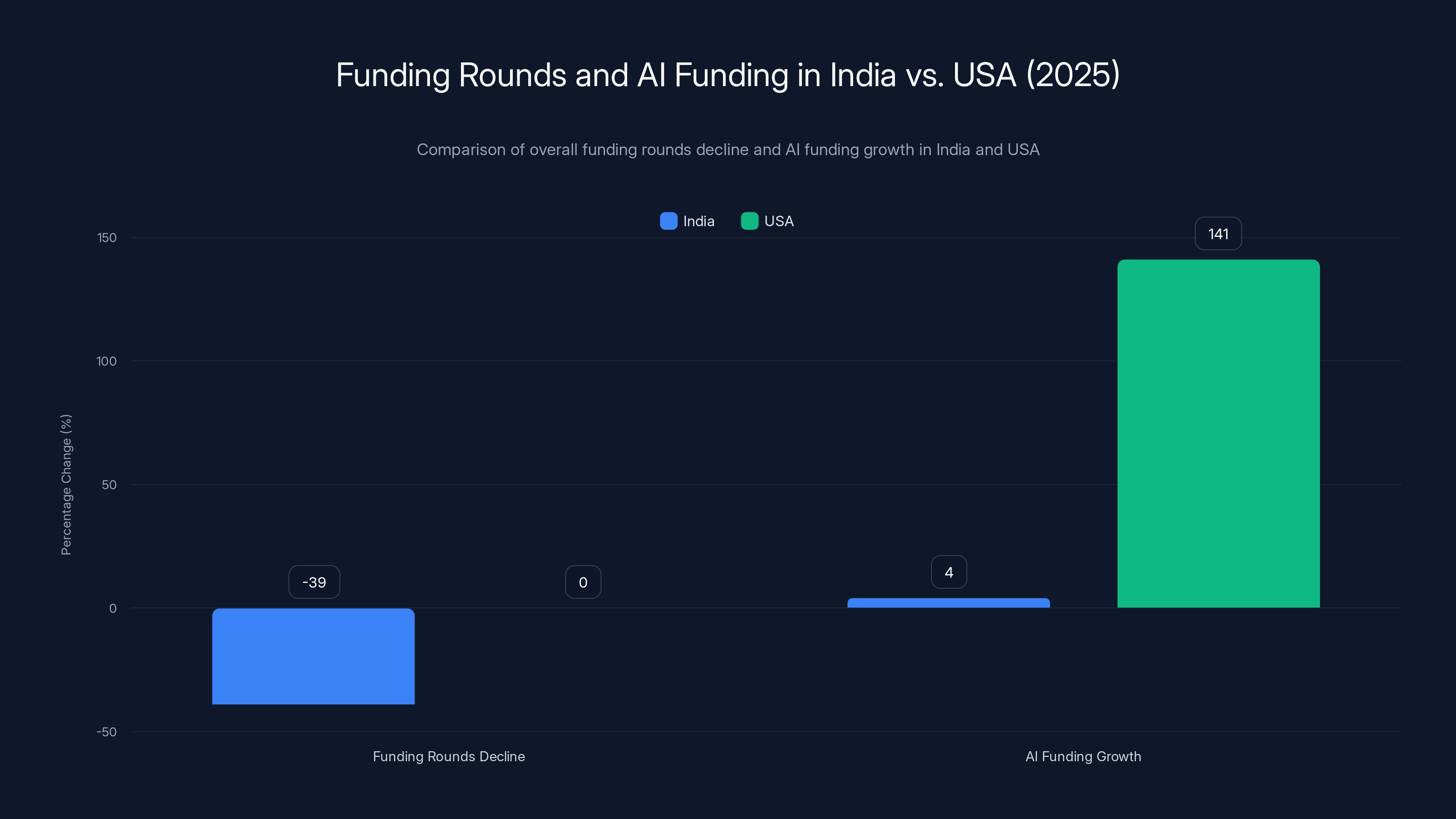

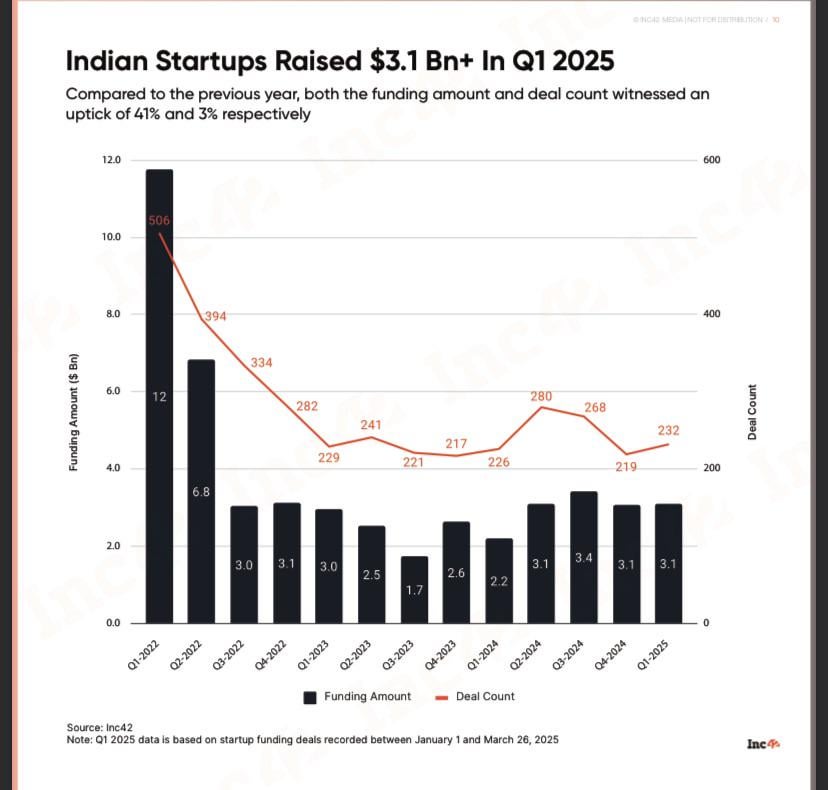

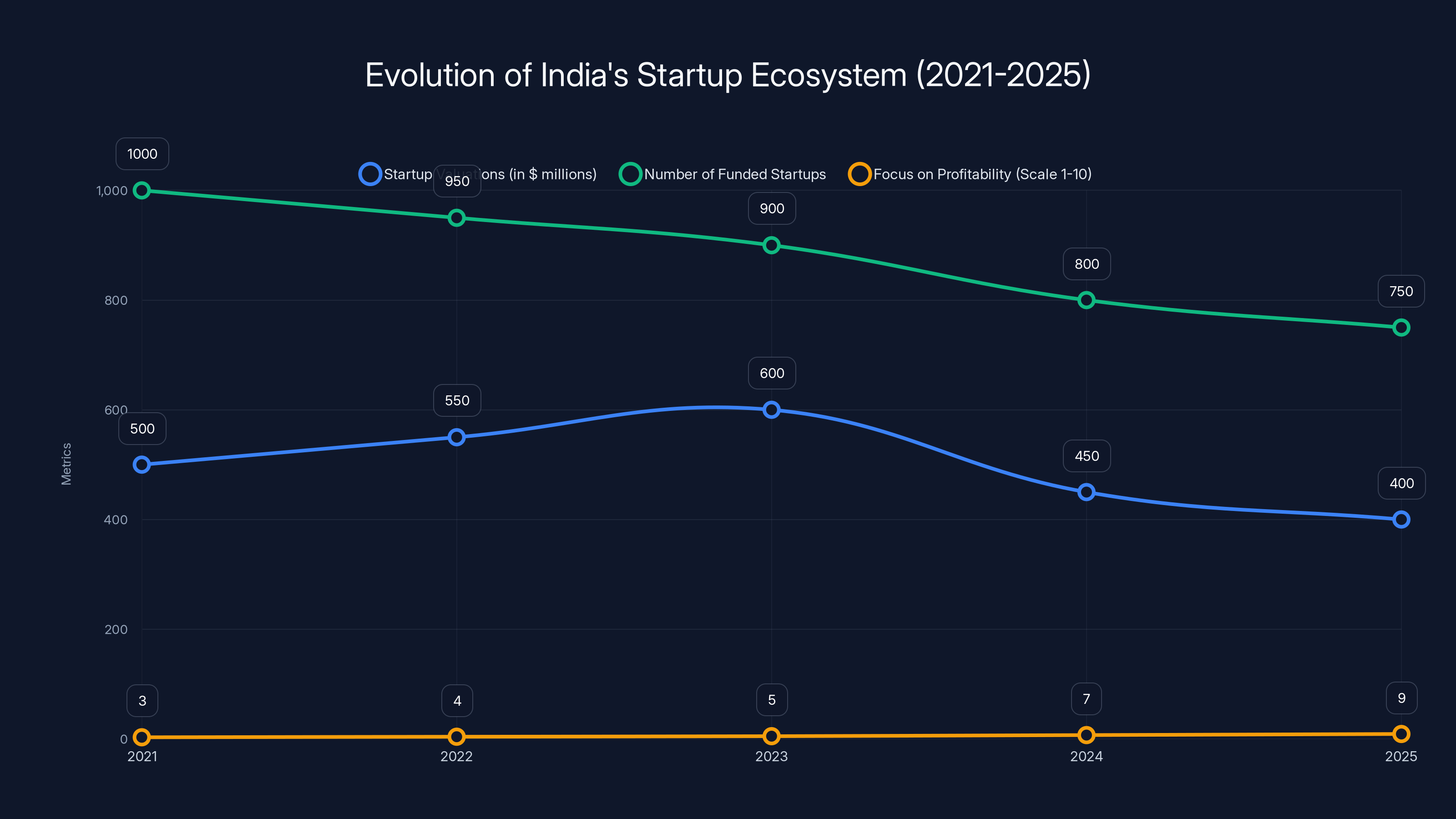

The number of funding rounds fell by nearly 39%, dropping from roughly 2,500 deals in 2024 to just 1,518 in 2025. That's not a small stumble. That's a wholesale recalibration of how capital flows through India's ecosystem. Founders who could demonstrate solid unit economics, real revenue, and clear paths to profitability suddenly had open doors. Everyone else? Much harder conversations.

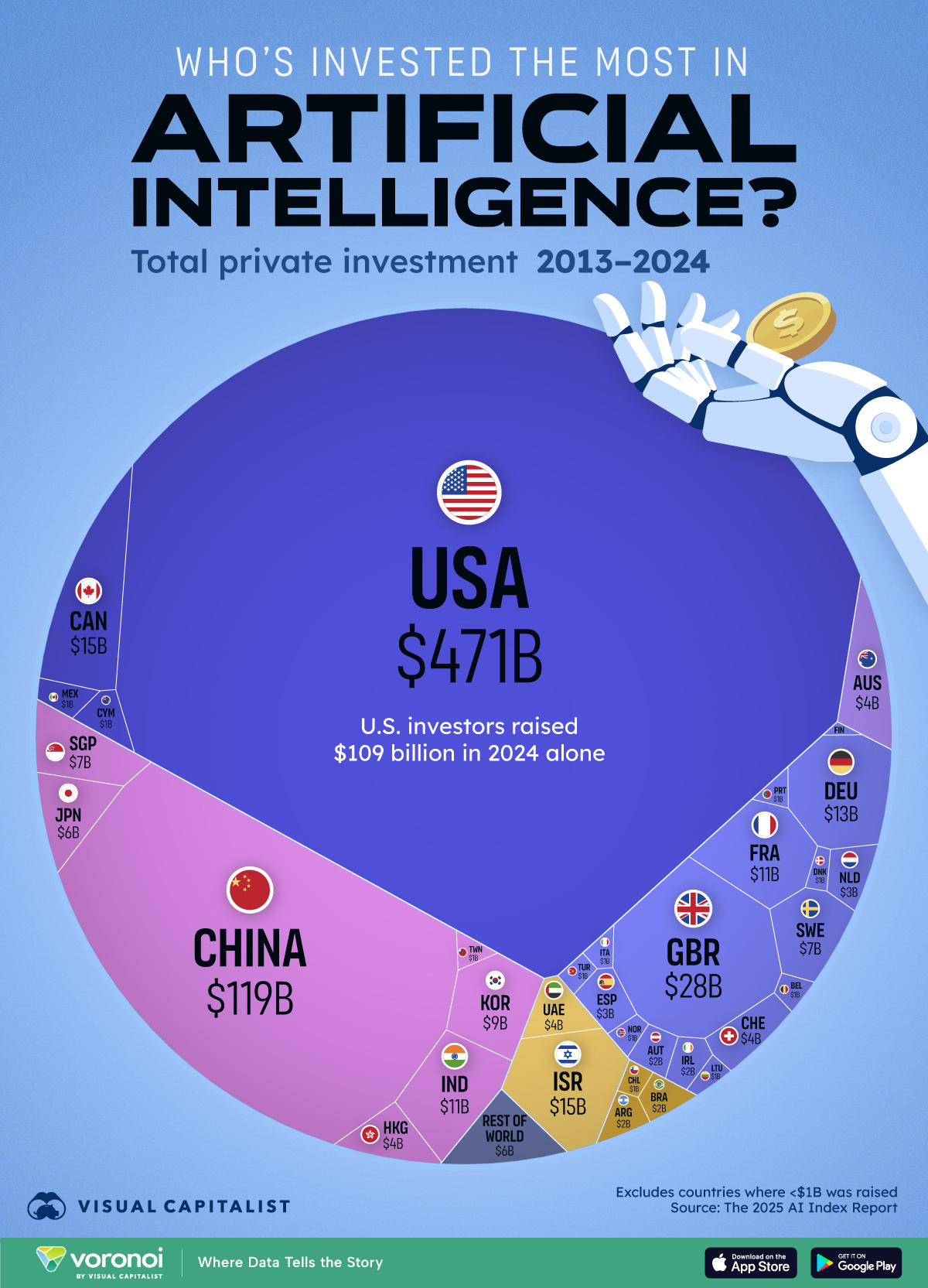

This diverges sharply from what happened in the U.S. over the same period. American venture capital surged past

What makes 2025 particularly interesting is that India's startup ecosystem didn't collapse. It matured. The narrative of "spray and pray" capital allocation gave way to something more sophisticated: capital flowing toward founders who understood their unit economics, had paying customers, and could articulate a path to profitability without burning through $10 million a month.

This shift matters because India's startup future depends on it. The country has the talent, the market size, the technical depth, and the hunger. What it needed was capital discipline. 2025 delivered exactly that.

TL; DR

- Funding rounds plummeted 39% to 1,518 deals in 2025, while total capital fell just 17% to $10.5B, signaling capital concentration

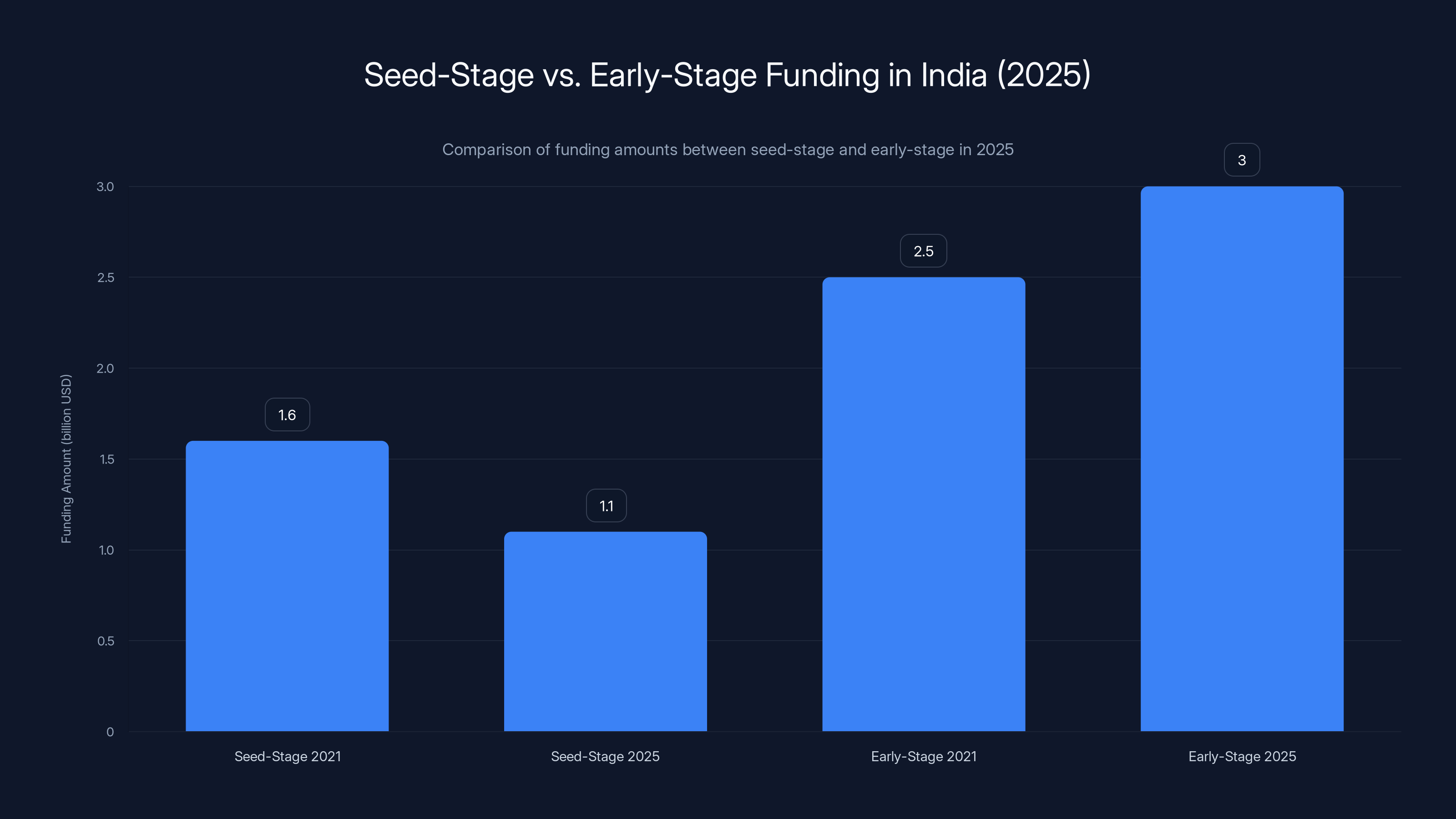

- Seed funding collapsed 30% to $1.1B as investors cut experimental bets, while early-stage funding grew 7%, showing preference for de-risked startups

- AI funding modest at $643M across 100 deals—a 4% increase compared to 141% surge in the U.S., reflecting application-over-model focus in India

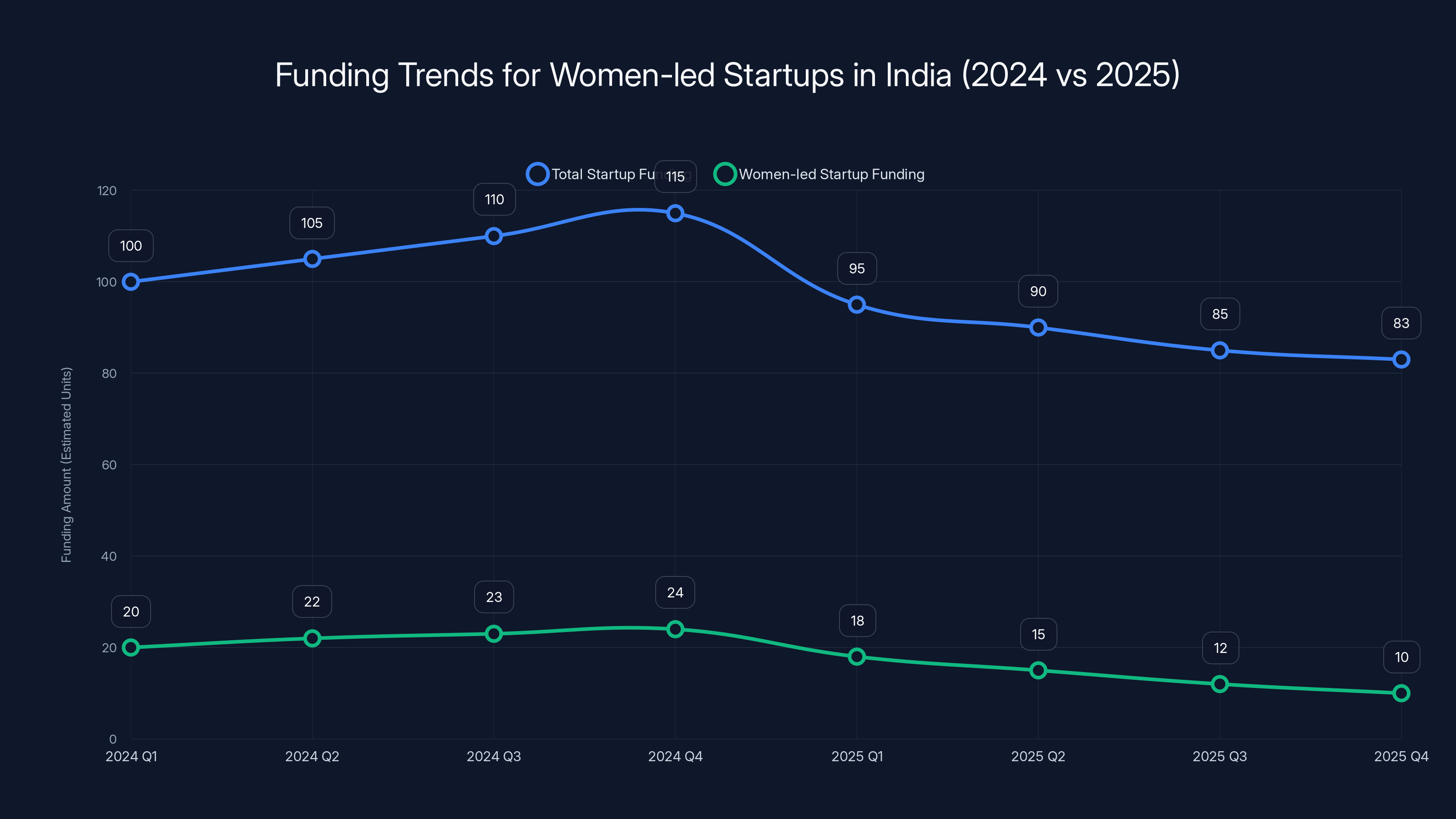

- Women-led startups faced tighter capital access, with funding declining as investors narrowed their thesis

- Manufacturing and deep-tech emerged as high-conviction areas where India had clear competitive advantages vs. global capital

In 2025, India saw a 39% decline in funding rounds, while AI funding grew by 4%. In contrast, the USA experienced a 141% increase in AI funding, highlighting differing investment focuses. Estimated data for funding rounds decline in the USA.

The Deal Count Collapse: What 39% Fewer Rounds Actually Means

Here's what keeps most people up at night: fewer funding rounds don't sound as bad as they actually are. A 39% drop in deal count is catastrophic for founders trying to raise capital. It means competition intensified overnight. It means the bar moved higher. It means your pitch deck has to sing.

In practical terms, what happened is this: in 2024, if you had a decent team, a problem worth solving, and a halfway credible product demo, you could probably get a meeting with five or six seed-stage investors. Some would pass. Some would ask for more data. But you'd get checks. By 2025, those same metrics barely got you a first coffee.

Investors became fixated on three things: revenue (even if small), unit economics (specifically how much it costs to acquire each customer versus what they pay you), and retention (are customers coming back, or is this a one-time transaction?). These aren't unreasonable asks—they're just metrics that require months of real customer traction to demonstrate. Which means founders couldn't raise on potential alone anymore.

The seed-stage pullback tells the story most clearly. Seed funding crashed from

This created a bifurcated market. Startups with existing revenue, proven metrics, or strong founder pedigree (prior exits, Tier 1 education, previous success) could still raise. Everyone else faced a desert. The median time to close a seed round extended from roughly four months to closer to six or seven. Some rounds that would have closed in two or three weeks in 2021 took three or four months in 2025.

What's fascinating is that early-stage funding (Series A, some Series B) actually grew 7% to $3.9 billion. That's not a typo. The earliest rounds got harder. The next stage up got easier, but only if you came with traction. This suggests investors were comfortable moving capital from "many bets at early stage" to "concentrated bets at companies showing real momentum."

The psychology here matters. When capital is scarce (or perceived as scarce), investors cluster around proven signals. They follow what's working. They avoid unproven bets. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where founders with traction raise more capital, while founders without traction struggle to get meetings. It's not evil—it's just capital allocation during uncertainty.

The chart illustrates a sharper decline in funding for women-led startups in India from 2024 to 2025, compared to the overall funding trend. Estimated data reflects reported trends.

The AI Paradox: Why India's AI Funding Looks Quiet Compared to the U.S.

Here's where things get interesting and slightly depressing if you're betting on India becoming an AI superpower overnight. AI startups in India raised $643 million across 100 deals in 2025. That sounds decent until you compare it to the U.S. market.

In America, AI funding exceeded $121 billion across 765 rounds in 2025—a 141% jump from 2024. So India's AI funding went up 4%. The U.S. went up 141%. That's not just different trajectories. That's different universes.

But here's what's important: that disparity doesn't mean India's missing the AI wave. It means India's approaching it differently.

The venture capitalists I've talked to in India point to a simple reason for the gap: there's no Indian equivalent of Open AI, Anthropic, or Meta's AI research division. India doesn't have foundational model companies training billion-parameter models on massive datasets. Building that layer requires insane capital (

Instead, India's AI money went to application-layer companies. Startups building AI customer service tools, AI tools for medical imaging, AI solutions for content creation, AI-powered logistics optimization. These are businesses that can generate revenue in year one, don't require researchers with Ph Ds publishing in Nature, and solve real problems in India's economy.

The data backs this up. Early-stage AI funding in India totaled

This isn't a failing. It's being pragmatic. An Indian startup building a Gen AI customer service tool using GPT-4's API can start making revenue in months. An Indian startup trying to build a foundational model to compete with GPT-4 would burn through a billion dollars and might still lose. Indian investors looked at that calculation and chose the former.

The catch is that this puts India in a vulnerable position long-term. If all your AI innovation is application-layer, you're dependent on the platforms that control the foundation. If Open AI changes their API pricing, or decides to build their own customer service tool, you're suddenly competing with someone with infinite resources. But for 2025, application-layer focus is the rational call.

What's worth watching is whether India can build breakthroughs in AI application categories where it has unique advantages: healthcare (300+ million underserved patients), agriculture (70% of rural population depends on farming), and logistics (scaling to reach 1.4 billion people). If Indian AI startups can dominate those segments and build defensible moats, then the lower absolute AI funding becomes almost irrelevant.

The Great Separation: Seed-Stage Collapse vs. Early-Stage Growth

Investing isn't supposed to work this way. The idea is you take bigger risks at earlier stages and progressively reduce risk as companies mature. That's the venture capital thesis: back 100 seed-stage companies, 20 make it to Series A, 5 make it to Series B, and one becomes a unicorn. The numbers don't add up, so you load up on early bets and hope compounding works.

2025 broke that model in India. Instead of a pyramid, you got an hourglass. Seed-stage got compressed. Early-stage got wider. Late-stage tightened again.

Seed-stage funding dropped from

Why did this happen? Three reasons, in order of importance:

First, seed-stage investors—especially micro-VCs and angel syndicates—lost money at scale in 2021 and 2022. Companies they backed at

Second, founders began getting smarter about when to raise. Some skipped seed rounds entirely and found angel networks, corporate partnerships, or customer revenue to bootstrap to Series A. Others took smaller seed rounds than they would have in 2021 (say,

Third, investors became obsessed with "de-risking." They wanted to see customer traction before funding. That pushed the definition of "seed" further along the company lifecycle. What qualified as seed in 2024 (idea + team + prototype) now qualifies as "pre-seed" or "founder stage." What qualifies as Series A (team + MVP + initial traction) got rebranded as "Series A." Everyone moved up the maturity curve to reduce risk, which ironically increased risk by eliminating early-stage capital.

The bright spot is that early-stage funding grew 7%, from

Late-stage funding also cooled, slipping from

What this creates is a bottleneck. If seed-stage capital shrinks, fewer companies graduate to early-stage. If fewer graduate to early-stage, fewer graduate to late-stage. The funnel gets narrower at every level. This explains why even though total funding only dropped 17%, deal count dropped 39%. Capital got concentrated into fewer companies.

In 2025, seed-stage funding in India dropped by 30% to $1.1 billion, while early-stage funding increased, reflecting a shift in investment focus. Estimated data.

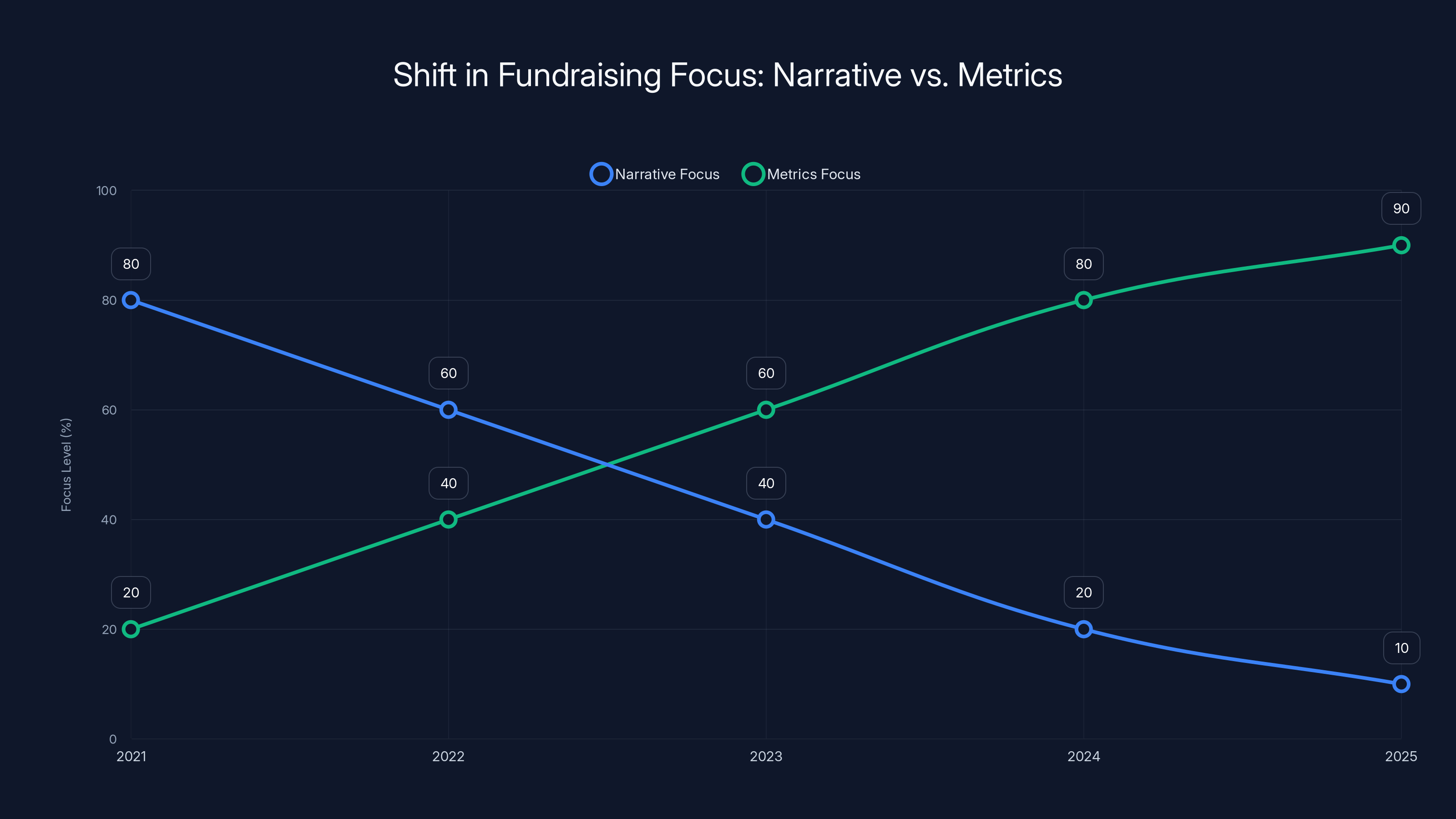

The Investor Thesis Shift: From "Size of Market" to "Unit Economics"

Talk to venture capitalists in 2024 and they'd say things like, "India has 1.4 billion people. E-commerce penetration is only 4%. We're backing companies in an ocean of TAM (total addressable market)." It was true, and it justified lots of capital being deployed into consumer businesses.

Talk to the same VCs in 2025 and the conversation shifted. "We want companies with $5 million ARR. We want them with positive unit economics. We want to see them achieve 40% gross margins. Then we'll talk Series B."

The shift from TAM-based thesis to metrics-based thesis is profound. It means the romantic notion of "we're building for a billion people, therefore valuation can be anything" is dead. The age of narrative venture capital is over. The age of metrics-driven venture capital is here.

This thesis shift had real consequences for founders. It meant that companies in consumer segments (like quick commerce or consumer services) that had previously raised on TAM arguments now had to prove unit economics. It meant that a Series B was no longer a "scale and optimize" round but a "you've already optimized and proven you can scale profitably" round.

Some founders adapted beautifully. They understood that investors wanted to see cohort analysis (breaking down customer acquisition cost by acquisition channel, by geography, by month), unit economics dashboards, and CAC payback period calculations. These founders raised successfully. Others were still pitching TAM and market size, wondering why doors closed.

The implication is that startup success in 2025 required not just product sense but financial discipline and analytical rigor. You needed to understand your numbers cold. You needed to know your CAC, your LTV (lifetime value), your churn rate, your gross margin. A founder who couldn't articulate these metrics in Q1 2025 was essentially unable to fundraise.

This is actually healthy long-term. It means less capital goes to companies with broken unit economics, which means more capital survives to deploy again later. It means the startups that do raise are more likely to reach profitability or successful exit, which means better returns, which means more capital flows into venture, which means a virtuous cycle forms.

But short-term, it's harsh. It's harder for founders who don't have finance backgrounds. It's harder for founders building in categories where unit economics take time to materialize (like deep-tech or biotech). It's harder for founders in secondary cities who don't have access to experienced advisors who can help them think about these metrics.

Late-Stage Reality Check: The Profitability Mandate

Late-stage capital didn't just shrink. It got conditional. In 2024, a Series D round at a "unicorn" valuation (over $1 billion) was almost automatic if you had decent traction. In 2025, late-stage investors wanted to see a path to profitability within 24-36 months. Some wanted to see it sooner.

This manifested in a few ways. First, some startups that expected

Third, and most dramatically, some startups simply couldn't raise. They had good traction, strong teams, and impressive metrics, but late-stage investors looked at their burn rate, their path to profitability, and their market size, and concluded the risk-reward didn't make sense. Those founders had to pivot to profitability, cut teams, or find corporate acquirers.

The profitability mandate makes sense when you think about what happened in venture. In 2020-2021, there was roughly $200+ billion in dry powder (capital committed to venture but not yet deployed) at major firms. LPs were writing huge checks. Everyone wanted to capture the next big thing. Capital was abundant.

By 2025, that dynamic had shifted. LPs had seen plenty of failures. Venture returns in 2021-2023 were mediocre (lots of write-downs and flat returns). They started asking tougher questions about deployment, returns, and timelines to exit. Venture firms responded by being more selective and demanding faster paths to profitability.

For deep-tech startups (biotech, hardware, energy), this was brutal. These categories often require 7-10 years to profitable. Late-stage investors that would have backed them in 2021 became much more conservative in 2025. Some deep-tech startups found themselves unable to raise even at lower valuations, because the thesis simply didn't fit the profitability mandate.

In 2024, 4% e-commerce penetration in India highlighted market size focus. By 2025, a shift to unit economics with a 40% gross margin requirement marked a new investment thesis. Estimated data.

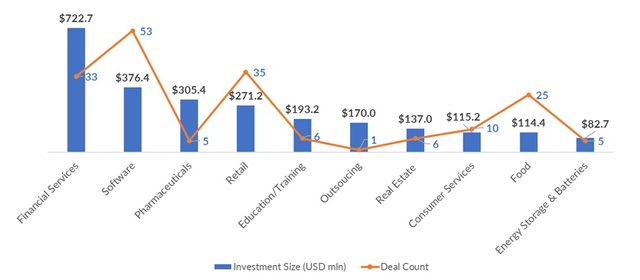

Manufacturing and Deep-Tech: India's Unfair Advantage Finally Mattering

Here's something weird that happened in 2025: manufacturing startups got capital. Not a ton, but real capital. And deep-tech startups building advanced materials, semiconductors, and manufacturing solutions got investors excited.

Why? Because India has something the U.S. doesn't: a cost structure advantage, a talent advantage, and a customer advantage, all simultaneously.

The U.S. venture capital market is obsessed with software and AI because software and AI have infinite scaling potential. You build it once, you sell it globally, you don't have unit economics problems. Manufacturing is the opposite: every unit costs money to make, you have supply chain complexity, and you're competing against China (which has been manufacturing for decades).

But India's venture capitalists woke up in 2025 to something that should have been obvious: manufacturing innovation doesn't need to compete with China on cost. It needs to compete on innovation, efficiency, and solving specific problems. And India has advantages in all three.

Advanced manufacturing startups—companies building better factory automation, smarter robotics, AI-driven quality control, new materials production—started attracting capital. The number of such startups increased nearly tenfold over the past four to five years, and by 2025, investors saw a clear pattern: these companies were profitable or near-profitable, had proven customer bases (other Indian manufacturers or exporters), and had defensible tech that was hard to replicate.

Why does this matter? Because it's a category where India doesn't face huge global capital competition. Venture capital in the U.S. barely touches manufacturing. In Europe, it's similar. In China, all the manufacturing innovation is happening within existing conglomerates. India can own this category globally if it executes.

Deep-tech more broadly saw capital concentration. Energy tech (especially renewable energy infrastructure, energy storage, and grid optimization), biotech (especially for diseases that disproportionately affect Indians), and advanced materials all saw investor interest. Not mega-rounds, but solid Series A and Series B rounds from serious investors.

The thesis is simple: if you're building deep-tech in a category where India has unique advantages (cost of production, access to customers, talent depth), and you're not competing with well-funded U.S. or European startups, you can raise capital. If you're trying to build something that competes head-to-head with U.S. deep-tech startups that have already raised $100+ million, you'll struggle.

This is actually brilliant capital allocation. India's venture market is maturing enough to understand its own advantages. Instead of trying to copy Silicon Valley (build another B2B SaaS company, build another consumer app), India's smart investors are saying: what can we build that's uniquely Indian, that leverages our advantages, and that plays to our strengths?

The answer is becoming clear: manufacturing innovation, deep-tech with local applications, and businesses that leverage India's scale and density (quick commerce, hyperlocal services, agricultural tech). Not because these are easy, but because India can win.

Consumer-Facing Startups: The Quick Commerce Boom and On-Demand Addiction

While deep-tech was getting serious capital, consumer-facing startups—particularly quick commerce and on-demand services—were also thriving. This might seem contradictory to the story of capital selectivity, but it's not. It's exactly what you'd expect when investors get smart about allocating capital to categories where they can actually win.

Quick commerce (15-minute deliveries of essentials) exploded in India in 2024-2025. Companies like Blinkit, Zepto, and others scaled to massive scale (hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue). By 2025, the venture question wasn't "should we fund quick commerce?" but "which quick commerce company should we back to build adjacent categories?"

Why did quick commerce work so well? Several reasons. First, India's urban density makes 15-minute delivery logistics feasible. In New York or San Francisco, you can't build a warehouse model for quick commerce that works economics-wise. In Bangalore, Mumbai, or Delhi, you absolutely can. Second, India's labor costs meant delivery economics worked. Third, consumer behavior had shifted—people got addicted to the convenience.

Venture capital followed. Startups building logistics infrastructure for quick commerce raised capital. Startups building fulfillment automation raised capital. Startups building unit economics software to help quick commerce companies manage delivery routes raised capital.

On-demand services saw similar logic. Companies offering household services (cleaning, repairs, plumbing), delivery jobs, and skilled services over an app raised capital. Not all of them. The winners were companies that managed unit economics (the cost of the service vs. the margin they captured) and had geographic density.

What's important is that this wasn't random capital deployment. These were rational bets on categories where India's unique characteristics (density, labor costs, consumer behavior) gave them structural advantages. The investors weren't saying "consumer is hot," they were saying "quick commerce and on-demand services work in India and probably nowhere else, so let's own this category globally."

The implication is that consumer startups that couldn't prove unit economics or geographic expansion potential had a much harder time raising. Generic consumer apps still faced skepticism. But consumer startups with a real insight about India-specific behavior and unit economics that proved out could raise.

Estimated data shows a significant shift from narrative-driven to metrics-driven fundraising from 2021 to 2025. By 2025, metrics became the dominant focus for investors.

The Female Founder Funding Gap: A Step Backward in 2025

Here's a statistic that stings. Women-led startups in India faced tighter capital access in 2025. Funding to women-led startups declined, even as overall startup funding was supposedly stable (down 17%, which isn't great but not a collapse either).

This happened for a specific reason: when capital gets selective, it gets selective toward characteristics that past exits have shown. And most past successful exits in India were led by male founders. So when investors started concentrating capital into "lower risk" bets, they unconsciously (or consciously) de-prioritized women-led startups.

It's the classic venture capital problem. The industry claims to want diversity, but when the pressure is on (capital is tight, returns are mediocre, LPs are asking tough questions), capital flows toward patterns that feel safe. And the safe pattern, historically, has been male founders.

The data backs this up. Women-led startups got a lower percentage of total funding in 2025 compared to 2024. The number of women-led startups that raised is harder to quantify, but reports suggest the decline was sharper than the overall decline in funding.

What's tragic about this is that women-led startups on average had better traction requirements to raise. A women-led startup needed stronger metrics to get a check than a male-led startup. This is documented in multiple studies. So the selectivity premium that male founders benefited from ("we back founders with this pedigree") became a penalty for female founders ("we back founders with stronger metrics").

The implication is that some talented female founders probably didn't get funded in 2025 even though they would have succeeded. They're building companies, growing them to profitability, and will eventually exit. But they did it with less venture capital, which means they either stayed bootstrapped longer, raised from non-traditional sources, or took on higher personal risk.

This is salvageable, but it requires intentionality. VCs in India need to actively work against their base case bias ("this founder reminds me of successful founders I know, who tend to be male") and look at metrics. A women-led startup with

IPO Market Dynamics: The Path Back to Public Markets

One of the silver linings of 2025 was that some startups actually made it public. The IPO window reopened. Companies that had been waiting for favorable market conditions started filing.

The significance of IPOs is understated. When a startup goes public, it's not just one exit. It's proof that the entire category can generate returns. It's a signal to LPs that venture capital can work. It's momentum that attracts more capital to the ecosystem.

India's IPO market in 2025 saw several startup exits, though the exact number varies by source. What mattered is that the narrative shifted from "venture capital is only about acquisition" to "venture capital can generate massive returns through public markets too."

For late-stage investors, this is crucial. A late-stage investor deploying capital in 2024-2025 wanted to see a plausible IPO path or acquisition path for their portfolio companies. IPOs happened in 2025, which validated the thesis that some of these companies could genuinely build independent, public companies.

The IPOs also set valuations. When you see a startup go public at a certain valuation, that information ripples backward. Late-stage companies that had privately valued at a multiple of their latest funding got a reality check. Secondary markets (where existing investors could sell shares) also started to clear at realistic prices, which gave everyone better information about what things were actually worth.

For early-stage investors, IPOs also matter because they're the ultimate upside. While everyone talks about 100x returns, the truth is that venture returns follow a power law: a few investments return 100x, many return 5-10x, and many return 0.5-2x. IPOs tend to be in the 10-100x category. More IPOs mean more instances of venture capital generating venture returns.

The Indian startup ecosystem is maturing with a focus on profitability and selective funding. Estimated data reflects a shift from high valuations to sustainable growth.

The Shift from Narrative to Metrics: How Fundraising Changed

If you were a startup founder fundraising in 2021, you could tell a story. You could talk about the problem you were solving, the massive market, your vision for changing the world. Investors would get excited and write checks.

In 2025, that story doesn't work. Or rather, it works only if you have metrics to back it up. The conversation structure completely shifted.

In 2021: "We're building for a billion-person market." Investor response: "That's amazing. How much do you need?"

In 2025: "We're building for a billion-person market." Investor response: "Great. Show me your CAC, LTV, churn rate, gross margin, and your path to profitability."

This isn't hypothetical. Every successful founder I know who raised in 2025 came prepared with a metrics deck. CAC trends over time. LTV calculations. Unit economics by cohort. Churn projections. Burn rate. Runway. Most of them spent more time on these slides than on the market opportunity slides.

What changed is that investors got burned in 2022-2023. They backed companies with amazing narratives that turned out to have broken unit economics. The company would grow 300% year-over-year but lose money on every transaction. Growth at all costs stopped being a thesis and became a cautionary tale.

So investors got defensive. They wanted repeatable, measurable proof that the business model worked before deploying capital to scale it. This is actually healthy discipline. It just means founders need to be much more analytical and rigorous.

The implication for fundraising in 2025 was that technical and financial literacy became competitive advantages. Founders who understood CAC, LTV, payback period, and gross margin could communicate with investors in their language. Founders who didn't understand these concepts struggled to raise, even if they had traction.

Global Capital Dynamics: Why the U.S. Surge Didn't Spill Over to India

In Q4 2025 alone, U.S. venture funding hit $89.4 billion. That's roughly what India's entire startup ecosystem raised in the full year. How is that possible? Why didn't all that capital flow to India?

The answer is that venture capital, despite being "global," is actually surprisingly local. Capital flows to where investors have conviction, expertise, networks, and regulatory comfort. And in 2025, investor conviction in the U.S. was dominated by one thing: AI.

AI companies in the U.S. were raising rounds at valuations that made no sense on traditional venture metrics. A Series B company raising

Indian investors looked at that same thesis and concluded: that race is already being won by American companies. Open AI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and a handful of others are in the lead. An Indian startup trying to build a competing foundational model would need $1-5 billion to compete, and even then success wasn't assured. The ROI on that bet, from an investor's perspective, looked poor.

So Indian investors did something smarter (arguably): they bet on applications. They said, "GPT-4 and other foundational models exist. Let's build India-specific applications on top of them." This required much less capital, time-to-revenue was faster, and the competition from American startups was lower (because American investors were all focused on foundational models, not applications).

The divergence between U.S. and Indian capital allocation in 2025 actually reveals something important about how venture capital works. It's not truly global. It's geolocalized toward different theses, competitive dynamics, and risk profiles in each market. U.S. capital did what made sense for the U.S. (bet big on AI infrastructure). Indian capital did what made sense for India (bet on applications and categories where India had advantages).

This is healthy. It means both markets are allocating capital rationally, even if the absolute numbers look imbalanced. India didn't fail to capture U.S. capital. India's investors correctly identified that competing with U.S. AI infrastructure startups was a bad bet and redirected toward opportunities that made sense locally.

Secondary Markets and Down Rounds: The Unspoken Reality of 2025

Here's what nobody talks about much: a lot of the funding numbers in 2025 aren't new capital. They're secondary transactions and down rounds. A secondary transaction is when an existing investor sells their stake to another investor at a certain price, with no new capital coming into the company. A down round is when a company raises at a valuation lower than its previous round.

Both happened in 2025, probably more than any recent year.

Secondary markets exist to give liquidity to early investors. You invest in a startup in Series A at a $50 million valuation. Three years later, that startup is still private, still hasn't exited, and you want to redeploy your capital to new investments. You sell your shares in the secondary market to a later-stage investor or a crossover fund. The transaction price indicates what people think the company is worth. If it's lower than the valuation from the previous round, prices are falling.

Down rounds were relatively common in 2024-2025. A startup that raised at

Why does this matter? Because it means that founder and investor expectations got recalibrated. Companies that thought they were billion-dollar potential realized they might be $100 million businesses. That's not failure, but it's a meaningful reality check. And on a spreadsheet, if capital is concentrated into fewer companies, and some of those companies get repriced downward, the total capital number stays high even though the number of winners shrinks.

For founders holding shares in a company that down rounds, it's painful but survivable. For investors who invested at the higher price, it's a loss (or at least unrealized losses until they sell). The effect is that wealth gets concentrated. Early investors in winners stay wealthy. Everyone else feels the pressure.

The Regulatory Environment: Background Context for Capital Selectivity

One thing that shaped the funding environment in 2025 (but is rarely discussed) is regulation. India's regulatory environment changed in subtle ways that made certain startup categories easier or harder to finance.

Fintech, for example, faced stricter regulatory scrutiny. Startups building payments, lending, or investment platforms had to navigate RBI (Reserve Bank of India) rules, which became more stringent. This meant fintech startups needed more compliance resources, which increased burn. It also meant some investor categories (international venture capital) became more cautious about India fintech because of regulatory risk.

Data privacy regulations (inspired by GDPR and other global standards) also affected startups. Any consumer-facing startup had to be careful about how it collected, stored, and used data. This increased legal costs and compliance complexity, which made it harder for small seed-stage startups to raise (because they lacked the resources to build compliant systems).

On the flip side, manufacturing and deep-tech startups benefited from government incentives and policy support. India's push for manufacturing self-sufficiency created tailwinds for startups in this space. Government contracts and policy support made these categories more attractive to investors.

The net effect is that the startup landscape in 2025 was shaped not just by venture capital selectivity but also by regulatory dynamics. Startups in favorable regulatory environments found capital. Startups in regulated or newly-regulated categories had to be more careful.

Founder Survival Strategies: How to Raise in a Selective Market

Okay, so you're a founder trying to raise in a market where deal counts are down 39% and investors are ruthless. What do you actually do?

First, you need traction. Not "we have a prototype and a thousand signups." Traction means: we have customers paying for our product, we have a sense of retention, and we have a path to more customers. This is the minimum. If you don't have this, most investors in 2025 will not take a meeting.

Second, you need to know your numbers cold. You need to understand your CAC, your LTV, your gross margin, and your payback period. If an investor asks, "What's your CAC?" and you hesitate or don't know, the meeting ends. You should be able to rattle off: "Our CAC is

Third, you need narrative discipline. Your story needs to be tight, compelling, and grounded in your metrics. Not "we're building for a billion-person market" but "we're solving X problem for Y customer segment in India's Z market. We've proven the unit economics with A customers and B revenue. We're raising to scale to C customers and D revenue."

Fourth, you need to be selective about investors. Don't spray your pitch to 50 investors. Do deep research on 5-10 investors who actually care about your category and have a track record of investing in it. Personalize your outreach. Show them you've done research. Get warm introductions. In a selective market, cold outreach is basically useless.

Fifth, you need to de-risk where possible. If you can reach profitability or a key milestone before raising, do it. If you can get a pilot customer at a major company, do it. If you can show traction in one geography before raising, do it. Anything that reduces risk makes investors more comfortable with you.

Sixth, consider non-dilutive funding. Grants, government programs, corporate partnerships, customer contracts that include upfront payments. These let you build to traction without giving up equity.

Seventh, if you're raising late-stage capital, have a clear path to profitability. Not "we'll get there eventually." Show the math. Show when you'll break even and how. Late-stage investors want to see the spreadsheet that gets you there.

Eighth, if you're male and founding a startup, be aware that you have an advantage in capital fundraising (it's documented). Use that advantage to build something great, not just to capture mediocre value. If you're female, know that you have a harder road, and that the metrics requirement is higher. This is unfair, but it's real, so plan accordingly.

Looking Ahead: What 2026 Likely Holds

Crystal-ball-gazing is a bad idea, but we can extrapolate from trends. Here's what I think we'll see in 2026:

First, capital will remain selective. The days of easy fundraising are not coming back. Founders should plan for a world where raising capital is hard and stay focused on building sustainable unit economics from day one.

Second, AI will continue to draw capital, but the mix will shift. More money will flow to AI applications and AI-enabled businesses, and less to competing with Open AI on foundational models. This should be good for India specifically.

Third, manufacturing and deep-tech capital will increase. Investors are realizing that India can own these categories globally. Expect to see more capital flowing to advanced manufacturing, energy tech, biotech, and deep-tech.

Fourth, consolidation will happen. Startups that raised in 2021-2023 at unsustainable valuations will get acquired below their valuation or wind down. Some will surprise everyone and become profitable. Most will find a middle ground (acquired at a price between their valuation and zero).

Fifth, international capital will move into India for specific categories. Rather than compete with Indian VCs on broad consumer bets, international VCs will focus on deep-tech, biotech, and manufacturing—categories where they have global expertise.

Sixth, founder-friendly capital (syndicates, rolling funds, alternative structures) will grow. As traditional VC gets scarcer, other forms of capital will become more important.

Seventh, exits will be important. IPO markets will remain open, and acquisitions will continue. Every successful exit creates narrative momentum and attracts more capital.

The fundamental shift is that startup markets are maturing. India's startup ecosystem is becoming more like the U.S. in the 1990s and early 2000s: selective, metrics-driven, and capital-efficient. That's not a bad thing. It's actually the sign of a healthy market.

The Real Story: Capital Got Smart

If you zoom out, here's the story of 2025 in India's startup ecosystem: capital got smart.

Investors stopped writing checks to everything that looked interesting. They started asking hard questions about unit economics, path to profitability, and why this particular startup should get capital instead of some other startup. Founders had to get disciplined about their metrics, their unit economics, and their path to scale.

Deal counts fell because capital got concentrated into companies with stronger signals of success. Total capital fell modestly because the reduction in deal count overwhelmed the increase in deal size. Winners got bigger checks. Losers got nothing.

This is what mature capital markets look like. This is healthy. It means venture capital in India is moving toward allocating capital to startups that are most likely to succeed, instead of spreading capital widely and hoping something sticks.

For founders, it's harder. For investors, it's cleaner. For the ecosystem, it's better long-term.

The question for 2026 and beyond is whether India's startup ecosystem will leverage this maturity into actual dominance in some categories. Manufacturing? Deep-tech? AI applications? If the answer is yes, then 2025 was the year the training wheels came off, and India's startup ecosystem showed it could run.

FAQ

What caused the 39% decline in funding rounds in India in 2025?

The sharp decline in funding rounds resulted from investor consolidation of capital into fewer, higher-quality companies. Investors became more selective and metrics-driven, requiring startups to demonstrate traction, unit economics, and customer retention before deploying capital. Seed-stage funding fell particularly sharply (30%) as investors pushed founders to prove product-market fit before backing them, effectively extending the timeline and increasing the barrier to early-stage capital. This represents a shift away from the "spray and pray" capital allocation of 2021-2023.

How did India's AI funding compare to the United States in 2025?

India's AI funding reached

What does "unit economics" mean and why did it become so important in 2025?

Unit economics refers to the revenue generated from each customer minus the cost of acquiring and serving that customer. Specifically, investors in 2025 focused on CAC (customer acquisition cost) and LTV (lifetime value), the ratio of which indicates whether a business model is sustainable. When venture capital became selective in 2025, unit economics became the primary metric for evaluating early-stage companies, because it's a predictive signal of whether a startup can scale profitably. Startups that couldn't demonstrate positive unit economics at small scale faced extreme difficulty raising capital, regardless of their market size or growth rates.

Why did early-stage funding grow 7% while seed-stage funding dropped 30%?

This apparent contradiction reflects investors pushing the risk forward in the funding timeline. Rather than back early, unproven founders with seed capital, investors required founders to reach some level of traction first (customer acquisition, revenue, or market proof), then raised bigger checks at the Series A stage for companies that had de-risked themselves. This created a bottleneck where fewer seed-stage startups got funded, but those that did and reached traction found Series A capital more available. The net effect is that the entry point for venture capital moved later in the company lifecycle, reducing the number of startups that can access venture capital.

What is a "down round" and why did they happen in 2025?

A down round occurs when a startup raises capital at a lower valuation than its previous funding round. For example, a startup that raised at a

Why did manufacturing and deep-tech startups attract more capital in 2025?

Manufacturing and deep-tech startups attracted capital because India has structural advantages in these categories that American and European venture capital cannot easily replicate: lower labor and production costs, technical talent depth, and first access to local customers. Investors realized that these were categories where India could compete globally without directly facing well-funded American competitors (who were focused on different opportunities). Additionally, the number of advanced manufacturing startups increased nearly tenfold over four to five years, proving viability and attracting follow-on investment. These categories offered better unit economics and clearer paths to profitability than many consumer-focused startups.

How did women-led startups fare in 2025's selective funding environment?

Women-led startups faced disproportionate pressure in 2025's selective environment. When investors became more conservative and focused on "proven" signals of success, they unconsciously (or consciously) favored founders who resembled successful founders from the past, most of whom were male. This meant women-led startups had to demonstrate stronger metrics and traction to get the same funding as male-led startups. Studies show women founders are more likely to be asked questions about risk mitigation, while male founders are asked about growth opportunities, creating different narratives and funding outcomes. Women-led startup funding declined in 2025 even as total funding was relatively stable, indicating a step backward in diversity.

What is the significance of India seeing IPO activity in 2025 despite tight funding?

IPO activity in 2025 demonstrated that the Indian startup ecosystem could generate traditional venture returns through public markets, not just acquisitions or failures. This is important because it validates the venture capital thesis: if you back high-potential companies early, you can see returns ranging from 10x to 100x+ through IPO exits. Additionally, IPO exits give information about what public market investors think these companies are worth, which ripples backward into private valuations and secondary markets. Each successful IPO generates narrative momentum and signals to LPs that venture capital deployment in India can work, attracting more capital to the ecosystem.

What strategy should founders use to raise capital in a selective market like 2025?

Founders should: (1) develop real traction (paying customers, retention data, revenue) before approaching investors; (2) master their unit economics (CAC, LTV, payback period) and be able to articulate them instantly; (3) tell a metrics-grounded narrative focused on your specific customer segment and business model, not generic market size; (4) be selective about investor targets and get warm introductions instead of cold outreach; (5) reduce risk before raising (reach profitability, get pilot customers, expand geographically); (6) consider non-dilutive funding (grants, partnerships, prepaid customer contracts); and (7) if raising late-stage capital, have a detailed path to profitability with clear timing and milestones. The key is demonstrating that you've de-risked yourself as much as possible before asking investors to write a check.

Conclusion: The New Reality of India's Startup Ecosystem

2025 was the year India's venture capital market grew up. The days of "if you can pitch well, you can raise" ended. The era of "show me the metrics" began.

This shift wasn't sudden or random. It was the inevitable result of market dynamics. Investors got burned in 2021-2023 with companies that had incredible growth narratives but broken unit economics. They watched startup valuations inflate beyond reason. They saw companies raise at $500 million valuations and fold two years later. They learned hard lessons.

So they got defensive. They demanded traction. They required metrics. They wanted founder teams with relevant experience. They wanted to see clear paths to profitability. They concentrated capital into fewer companies instead of spreading it widely.

From an investor's perspective, this is wise. From a founder's perspective, it's brutal. From an ecosystem perspective, it's healthy but painful.

Here's what matters going forward:

First, the Indian startup ecosystem has enough capital. It's not starving. But capital is discriminating. If you're building something that makes sense (good unit economics, clear market, experienced team, achievable path to scale), capital is available. If you're not, capital is scarce.

Second, the startup ecosystem is maturing toward India's actual advantages. Deep-tech, manufacturing, AI applications, consumer services leveraging density. Not everything that worked in Silicon Valley will work in India. The smart capital is figuring out what will work in India and concentrating there.

Third, founder quality matters more than ever. The best founders (most coachable, most analytical, most resilient) are raising capital and building companies. The average founders are facing a harder path. This will lead to better outcomes long-term because the average founders will either up-level or move on to other endeavors.

Fourth, the Indian startup ecosystem is becoming more like mature venture markets (the U.S., Europe). This is not a bad thing. Mature markets have lower overall returns (because there's less low-hanging fruit), but the returns are more predictable and the capital is more efficiently deployed.

For founders reading this: you're not in a bad time to build. You're in a disciplined time to build. If your idea is good, your execution is sound, and your metrics are strong, capital exists. You just have to earn it.

For investors reading this: the selective approach is paying off. Capital is more concentrated. Winners are becoming clearer. Exits are happening. The power law is reasserting itself. Continue to be disciplined, but also continue to bet on India. The next generation of massive companies will likely be Indian, and they're being built right now.

For everyone else: this is the time to understand whether your startup idea actually has good unit economics, can reach scale profitably, and solves a real problem. Because in 2025's environment, those are the only startups that matter.

The startup lottery is over. The startup meritocracy has begun.

Key Takeaways

- Funding rounds collapsed 39% to 1,518 deals while total capital fell only 17%, showing extreme investor concentration into fewer companies

- Seed-stage funding dropped 30% as investors demanded traction before deploying capital, pushing the entry point for venture capital later in company lifecycle

- India's AI funding grew only 4% (vs. U.S. growth of 141%) because investors focused on applications over foundational models, leveraging existing platforms like GPT-4

- Manufacturing and deep-tech startups attracted capital because India has structural advantages (cost, talent, customer access) where global competition is lower

- Investor thesis shifted from market size narratives to metrics-driven evaluation, requiring founders to master CAC, LTV, churn, and payback period calculations

- Women-led startups faced disproportionate funding decline, requiring higher metrics standards to access the same capital as male-led founders

- Late-stage investors mandated clear paths to profitability within 24-36 months, eliminating growth-at-all-costs capital deployment

- Founders must now demonstrate real traction (paying customers, revenue, retention) before most investors will take meetings, eliminating the prototype-only funding era

![India Startup Funding 2025: Why Investors Got Selective [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/india-startup-funding-2025-why-investors-got-selective-2025/image-1-1766886018433.jpg)