Inside the Insight Partners Lawsuit: What Kate Lowry's Case Reveals About Venture Capital Culture

On December 30, 2024, Kate Lowry, a former vice president at Insight Partners, filed a lawsuit in San Mateo County, California, alleging disability discrimination, gender discrimination, and wrongful termination. The case isn't just another employment dispute—it's a window into how power dynamics, compensation inequality, and toxic workplace cultures persist within some of the most prestigious venture capital firms in the country. According to TechCrunch, Lowry's lawsuit highlights these ongoing issues.

Lowry's story reads like a cautionary tale about what happens when institutional power goes unchecked. She arrived at Insight Partners in 2022 after an impressive career trajectory: Meta, McKinsey & Company, and an early-stage startup. She had the resume, the experience, and the credentials that typically promise career success in venture. What she encountered instead was a workplace environment that systematically undermined her contributions, underpaid her compared to market standards, and ultimately terminated her employment weeks after she formally documented her grievances in writing.

The lawsuit is significant because it follows a pattern we've seen before in venture capital. Ellen Pao's landmark 2012 suit against Kleiner Perkins cracked open an industry that had successfully kept its worst practices hidden from public view. Pao's case, despite her loss in court, catalyzed a broader reckoning about how women and underrepresented groups are treated in tech investing. Lowry's case carries similar weight, arriving at a moment when venture capital is under increased scrutiny for diversity, equity, and inclusion failures, as noted by Bloomberg.

What makes Lowry's allegations particularly compelling is the specificity and the timeline. This isn't vague or generalized—the suit documents concrete incidents, supervisor behavior, compensation figures, and a clear chain of retaliation. When she sent a formal letter to Insight's leadership detailing her treatment in May 2025, the company terminated her employment a week later. That timing is almost cartoonishly incriminating and suggests either stunning arrogance or a misunderstanding of retaliation law.

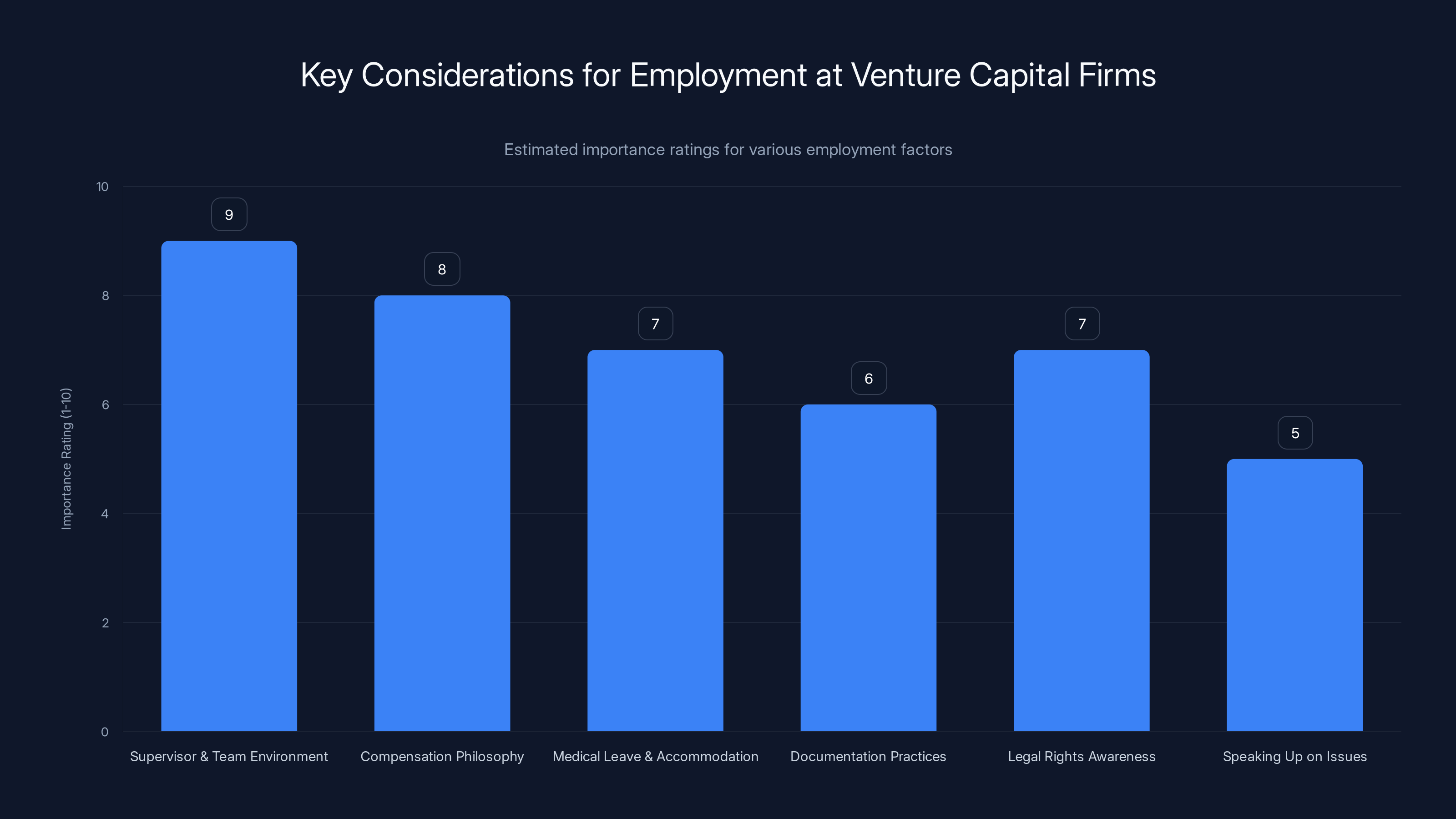

For employees considering roles at venture capital firms, for industry watchers concerned about institutional culture, and for anyone interested in how power operates in tech, Lowry's case offers critical lessons. Let's break down what happened, what it reveals about the venture capital industry, and what it means for the future of workplace accountability in tech.

Who Is Kate Lowry and Why Does Her Background Matter

Kate Lowry didn't walk into Insight Partners as a junior employee uncertain about her value. She came with a pedigree that most professionals would envy. Her career included stints at Meta (formerly Facebook), one of the world's largest technology companies; McKinsey & Company, the elite management consulting firm; and an early-stage startup, where she presumably gained exposure to the venture-backed entrepreneurial ecosystem.

This background is important because it establishes that Lowry wasn't hired for her potential—she was hired for her proven capability. She had navigated complex organizations, managed cross-functional teams, and contributed to companies at different stages of maturity. She understood both corporate structure and startup dynamics. By any reasonable standard, she was qualified for a vice president role at a venture capital firm.

The position at Insight Partners presumably represented a career move that felt like a logical progression. Venture capital roles often attract people from strong operational backgrounds. Firms look for partners and professionals who understand how companies work, can help portfolio companies with strategic challenges, and can identify investment opportunities based on deep industry knowledge. Lowry's background checked all those boxes.

What's particularly relevant is that Lowry came from Meta, a company with substantial resources dedicated to compliance, HR infrastructure, and legal review. She had experience working in an environment with formal processes, documented policies, and (theoretically) accountability mechanisms. She likely had an expectation that a venture capital firm, despite being smaller, would operate with basic professional standards. That expectation appears to have been violated almost immediately upon her hiring.

The fact that she'd also worked at a startup is crucial because it meant she understood the intensity and demands of that world. She wasn't naive about long hours or high pressure. But there's a massive difference between the intensity that serves a business mission and the intensity that serves managerial control and domination. Her history suggests she understood that distinction.

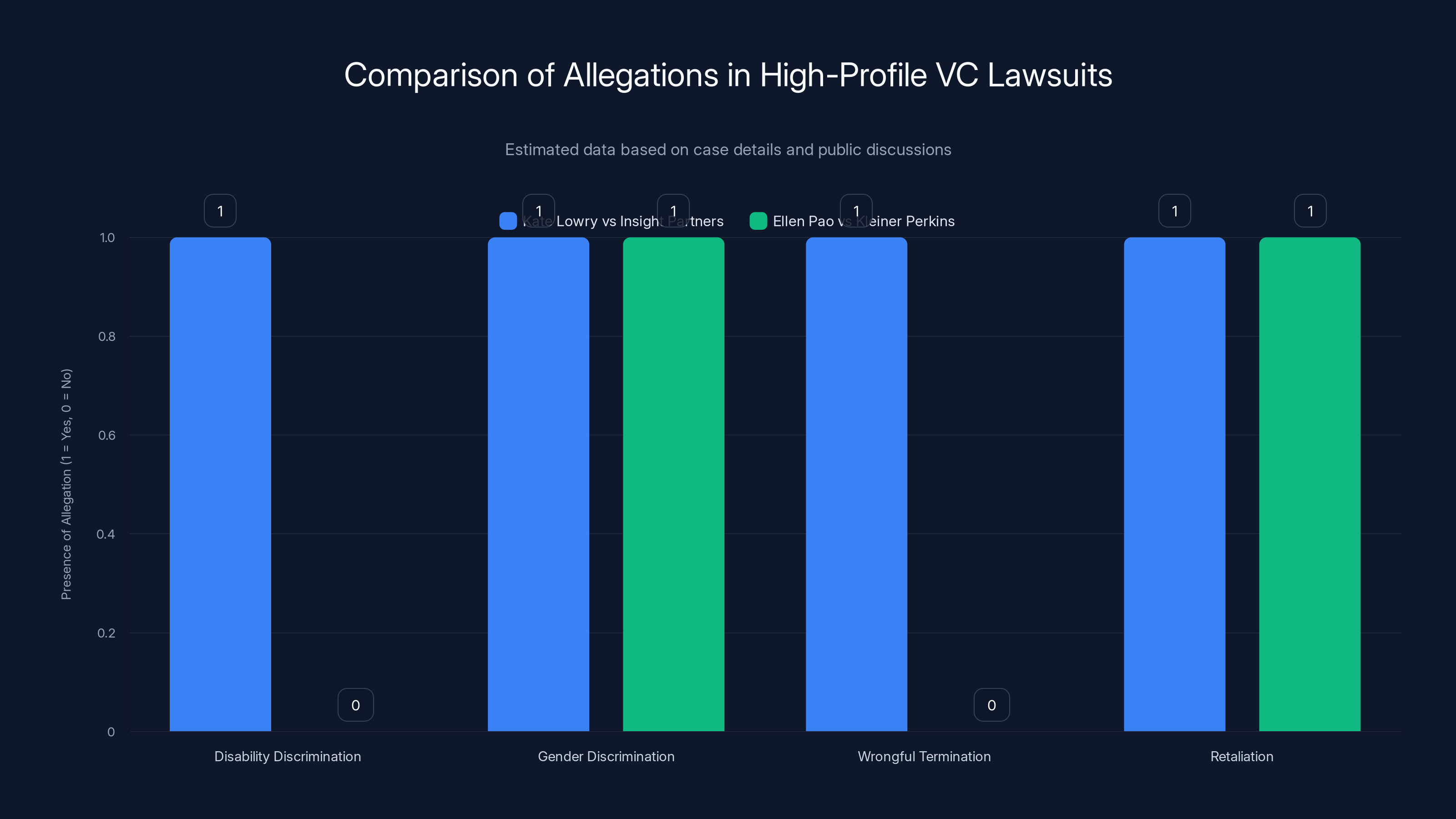

Both cases highlight gender discrimination and retaliation, but Lowry's case also includes disability discrimination and wrongful termination. Estimated data based on case details.

The Hiring Bait and Switch: When the Job Isn't the Job You Accepted

One of the first red flags in Lowry's suit is what happened immediately upon her arrival at Insight Partners. During her interview process, she was told she would report to a specific supervisor. Upon actually starting, she was assigned to a different supervisor entirely.

This is more than just an administrative mix-up. The supervisor assigned during the interview process likely has different management style, priorities, and expectations. If Lowry had serious reservations about a particular manager, she might have declined the role. The fact that Insight swapped supervisors after hiring suggests either incompetence in the onboarding process or deliberate deception during recruitment.

In established companies with functional HR departments, this doesn't happen. There's a position, a reporting structure, and an onboarding process that ensures consistency between the job description and reality. That these basic standards failed at Insight Partners suggests either the firm's operations are chaotic or there was intentional misrepresentation.

The bait-and-switch approach creates a psychological disadvantage for new hires. You've already accepted the role, signed documents, potentially relocated, and made other commitments. Reversing the reporting structure now creates friction that a new employee may feel pressure to accept. "We made a change, hope you understand" is a lot harder to push back on than "I'm not comfortable with this arrangement" during the interview process.

This initial move set the tone for the relationship between Lowry and her first supervisor—a tone of deception and unstated expectations. It's the kind of small violation that creates a foundation for larger ones.

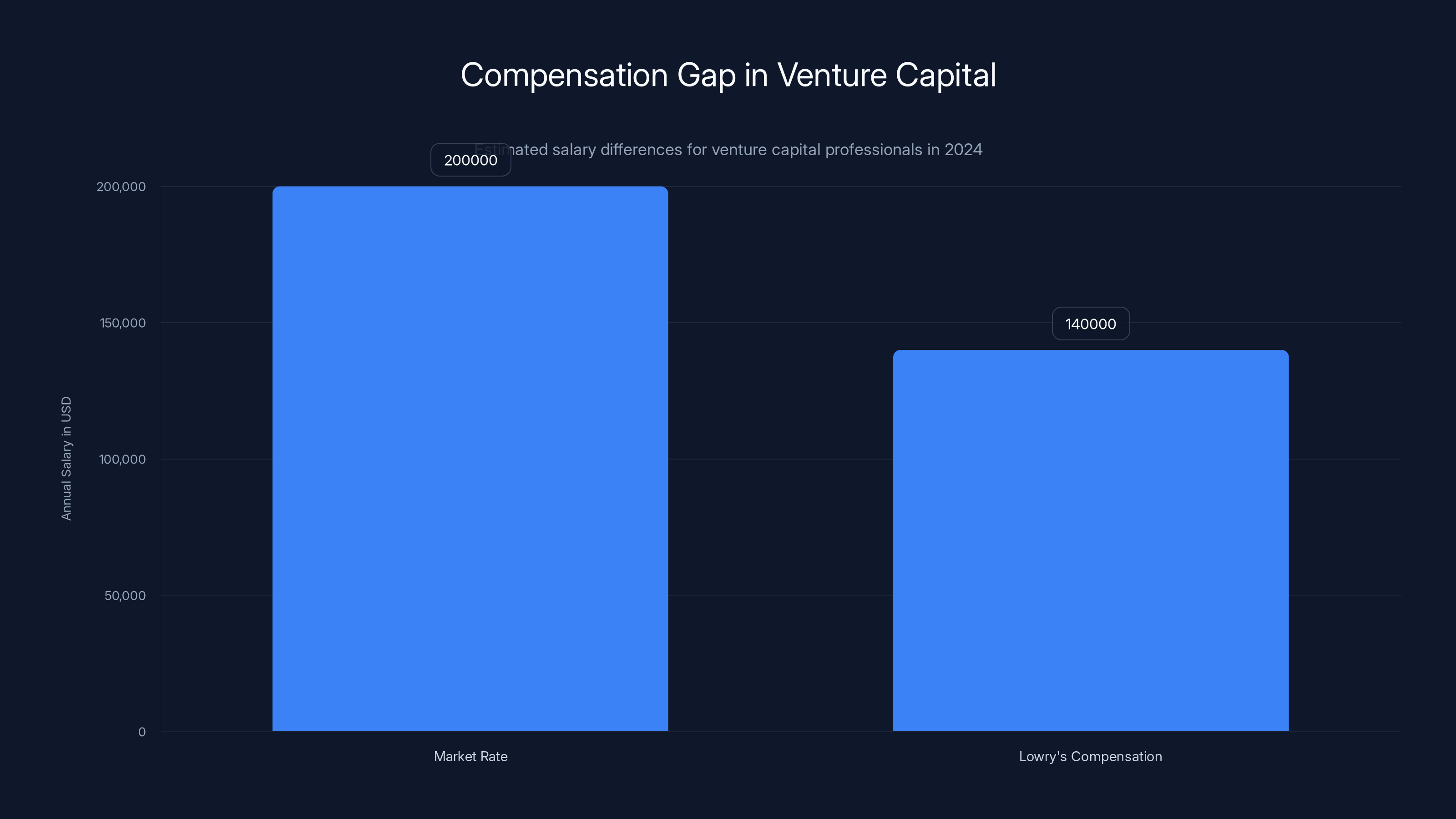

Estimated data shows a 30% compensation gap, with Lowry earning approximately $60,000 less than the market rate in 2024.

Extreme Availability Demands and the Performance Theater of Overwork

The work requirements imposed on Lowry are a centerpiece of her lawsuit, and for good reason. According to the suit, her supervisor demanded that Lowry be "online all the time, including PTO, holidays, and weekends," and required her to respond to communications between 6 a.m. and 11 p.m. daily.

Let's be clear about what this means: Lowry was essentially expected to be available 17 hours a day, seven days a week, including when she had taken paid time off or was supposed to be on vacation. This isn't a demanding schedule. This is a schedule that's designed to eliminate boundaries between work and personal life.

Venture capital is known for intensity. Partners often work long hours, are responsive to portfolio company crises, and are on call for time-sensitive deals. But there's a difference between the natural intensity of a job and the manufactured intensity imposed by a manager who's using availability as a control mechanism.

The 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. window is particularly telling. That's not about business necessity—that's about establishing authority and dominance. A legitimate business need wouldn't require response at 6 a.m. on weekends or at 11 p.m. on Thanksgiving. This requirement serves no purpose except to demonstrate power and to exhaust the employee.

The suit also alleges that the supervisor spoke openly about applying different standards to different team members—specifically, that hazing would be "longer and more intense" for Lowry than for male employees. This statement, if true, is powerful evidence of intentional discrimination. It's not an accident or a difference in communication style. It's a direct statement that Lowry would be treated more harshly because of her gender.

This kind of environment doesn't just create stress—it creates conditions for physical and mental health deterioration. Which is exactly what happened to Lowry, according to her account.

Health Consequences and Medical Leave: When the Job Becomes Harmful

According to the lawsuit, Lowry's health deteriorated under these working conditions. The suit alleges that she became "increasingly ill" due to the work environment, and her physician advised that she take a medical leave of absence. She was granted leave and took it from February through July 2023—a six-month period.

A six-month medical leave is not a vacation. It signals significant health issues—whether physical, psychological, or both. For Lowry to be absent for that long suggests her condition was serious enough that her doctor believed she needed extended recovery time away from work.

The fact that Insight Partners granted the leave is potentially relevant. It suggests the firm recognized there was a problem or didn't want to engage in a legal fight over denying FMLA-protected leave. But what's crucial is what happened when Lowry returned.

Upon returning from medical leave in late July 2023, Lowry was placed on a different team. This is described neutrally in the suit, but it's worth examining: does returning from medical leave typically result in being moved to a different team? Or is that a way of signaling that the original placement didn't work?

More damaging is what the head of human resources allegedly told Lowry: "If the new team did not like her, she would be fired." This statement is extraordinary in its implications. It's essentially saying, "You're now on a team that has been given veto power over your continued employment." This removes any job security and puts Lowry in a position where she must immediately prove herself to a new group—right after returning from medical leave when she's presumably vulnerable and needs stability.

In September 2023, Lowry suffered a concussion and took another medical leave, which lasted until late 2024. When she returned again, the suit alleges her poor treatment continued, now under a new supervisor due to team departures.

What's remarkable about this timeline is that Insight Partners had two opportunities to improve the situation (after each medical leave) and apparently did neither. Instead, the firm appears to have continued or escalated the problematic dynamics that necessitated medical leave in the first place.

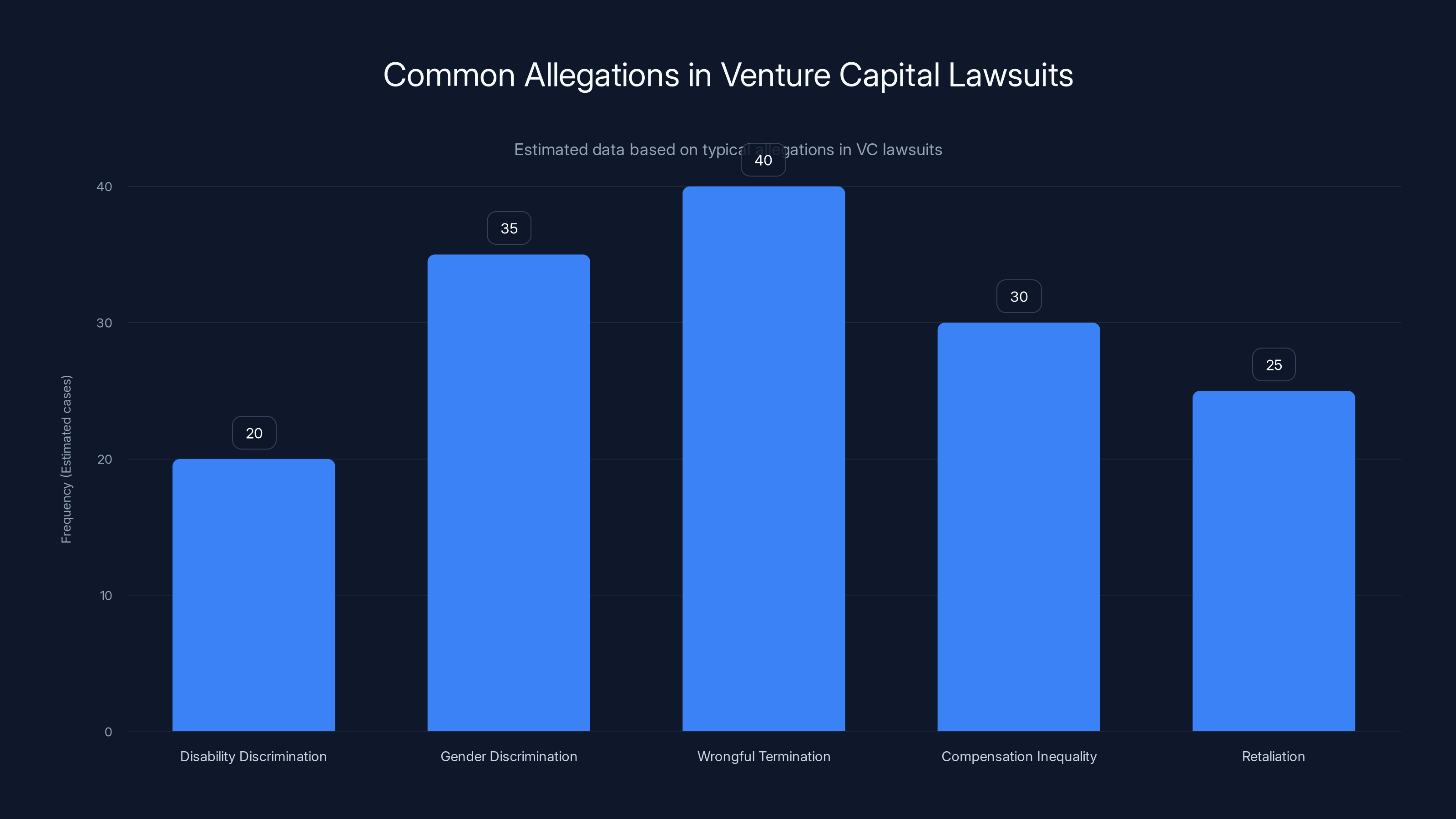

The chart highlights common allegations in venture capital lawsuits, with gender discrimination and wrongful termination being the most frequent. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Compensation Inequality: The 30% Market Discount

One of the most concrete allegations in Lowry's suit is that her compensation was approximately 30% below market rate in 2024. By April 2025, she was informed that her compensation would be cut further.

A 30% compensation gap is not a rounding error or a difference in how two firms value the role. It's substantial. It suggests either that Lowry was hired at an artificially low rate (which raises questions about why) or that her compensation wasn't adjusted as market rates evolved.

For context, venture capital professionals typically earn salaries in the

The timing of the compensation reduction attempt (April 2025) is significant. This is shortly before Lowry sends her formal complaint letter in May 2025. Was the compensation cut an attempt to pressure her to accept worse terms? Was it a signal that the firm was preparing to exit her? The suit doesn't specify Insight's motivation, but the timing is suspicious.

Compensation discrimination disproportionately affects women and underrepresented groups in tech. When someone is paid below market rate, they're not just losing direct income—they're building less retirement savings, have less to invest, and have less financial flexibility. Compound this over decades, and the gap becomes enormous. Research from organizations like the National Women's Law Center has consistently documented that women, particularly women of color, face significant pay gaps in tech and finance.

The fact that Lowry had the market knowledge to know she was being underpaid, and had the professional experience to object, likely made her a problem for Insight Partners. An employee who doesn't know she's underpaid is easier to retain. An employee who knows and is willing to fight is a liability—at least in the eyes of managers who operate from a position of dominance rather than collaboration.

The Formal Complaint and the Retaliation That Followed

In May 2025, Lowry and her attorneys sent a formal letter to Insight Partners documenting her allegations of discrimination, unfair treatment, and compensation inequality. This is a critical moment in the timeline because what happened next is precisely what retaliation law is designed to prevent.

A week after sending that letter, Insight Partners terminated Lowry's employment.

The timing alone is damaging to Insight Partners' position. Retaliation occurs when an employer takes adverse action against an employee in response to the employee reporting illegal conduct or asserting legal rights. When an employee complains in writing and is terminated within days, courts look at that timing as evidence of retaliation.

There's an important distinction between firing someone and firing someone who just filed a complaint. The former is within an employer's rights (in most at-will employment states). The latter is illegal under federal law. The one-week gap between complaint and termination strongly suggests the latter.

This is where Insight Partners' legal exposure becomes acute. Even if the firm believes it has a defense against the discrimination allegations, the retaliation claim is much harder to defend. You either terminated Lowry because of her complaints (retaliation) or you terminated her for cause (unrelated to the complaints). Insight will need to articulate what that cause is. And that cause will need to be convincing enough to overcome the temporal proximity between the complaint and the termination.

Lowry's decision to send a formal letter through attorneys was strategically sound. It created a documented record of her complaints and established a clear timeline. When she was then fired, there was no ambiguity about when the firm learned of the problems.

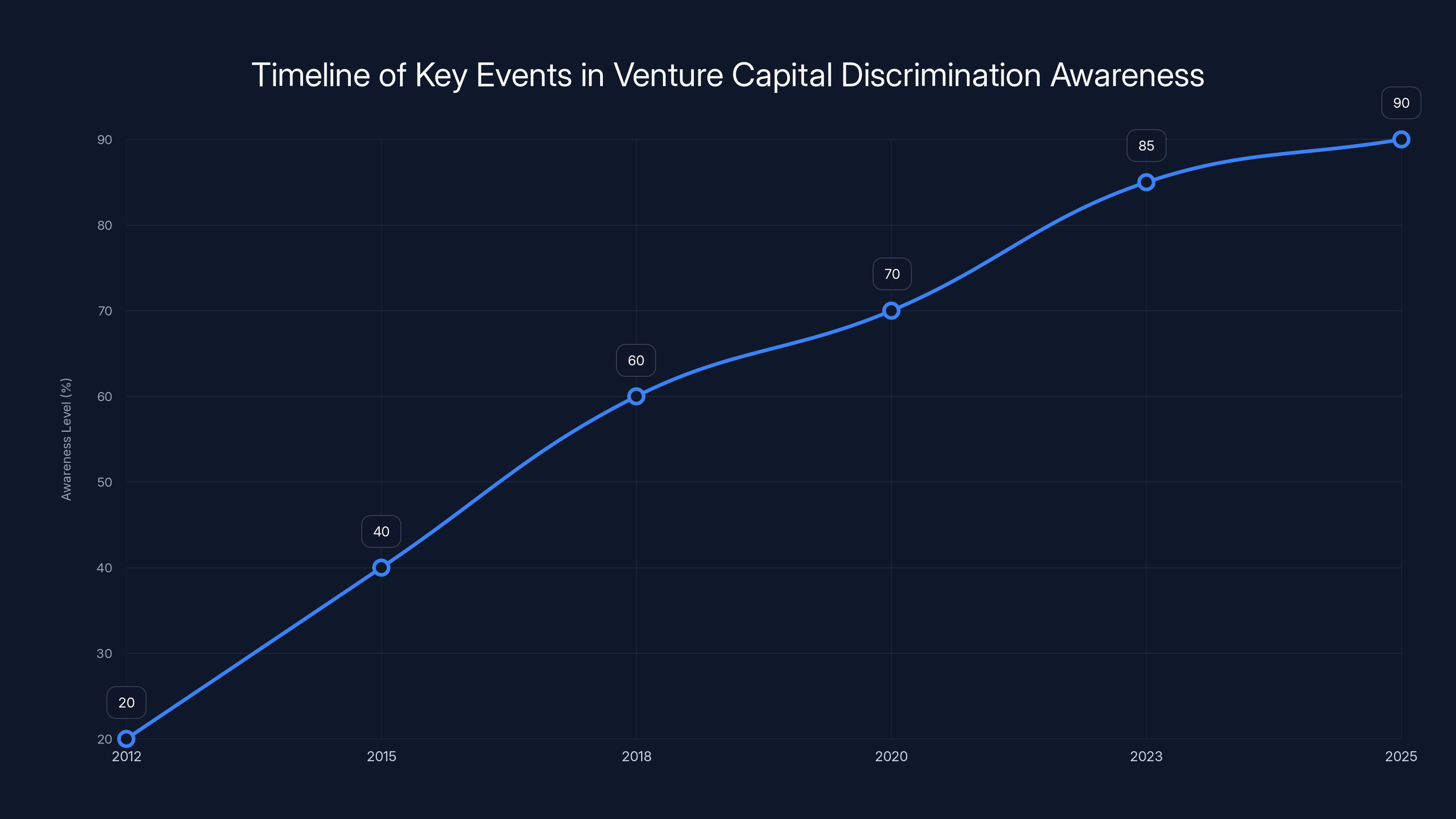

Estimated data shows a significant increase in awareness of discrimination issues in the venture capital industry from 2012 to 2025, influenced by key lawsuits and cultural movements like #MeToo.

The Broader Industry Parallels: Ellen Pao and the Venture Capital Reckoning

The lawsuit has been compared to Ellen Pao's 2012 suit against Kleiner Perkins, and those comparisons are apt. Pao, who was a partner at Kleiner Perkins, sued the firm for discrimination and retaliation after being terminated. Though she lost the case in court, the suit became a watershed moment for how the venture capital industry was perceived.

Kleiner Perkins, one of the most prestigious venture capital firms in the world, was forced to disclose information about its hiring practices, compensation structures, and workplace culture. The lawsuit revealed uncomfortable truths about how the firm treated women partners and professionals. Even though Pao lost legally, the reputational damage was significant. The case opened a conversation about whether venture capital was genuinely committed to diversity or was simply paying lip service.

Following Pao's case, other women sued major tech and finance companies. The venture capital industry, which had operated with very little public scrutiny, suddenly faced broader questions about its practices.

Lowry's case arrives in a different era. We've had over a decade of increased awareness about discrimination in tech. The #Me Too movement has created a cultural framework for discussing workplace abuse. There's been a proliferation of employment attorneys specializing in discrimination cases. Social media means that details of lawsuits spread faster and reach broader audiences.

But have institutional practices actually changed? That's the deeper question Lowry's case raises. Pao's lawsuit happened in 2012. Here we are in 2025, and a prominent venture capital firm is allegedly engaging in many of the same practices that Kleiner Perkins was accused of. This suggests that legal consequences alone haven't been sufficient to change the industry's culture.

Gender Dynamics in Venture Capital and the Supervisor Factor

One detail worth examining carefully: Lowry's first supervisor, the one who allegedly imposed the extreme availability demands and spoke about applying different standards to women versus men, was a woman.

This is not unusual in discriminatory environments. Women managers can and do perpetuate gender discrimination. Sometimes, they do so to prove loyalty to male-dominated power structures. Sometimes, they do so because they internalized the same problematic values that created the environments they worked in. Sometimes, they do so because they view other women as competitors rather than colleagues.

Why does this matter? Because it complicates the narrative of a male-dominated firm discriminating against women. If Lowry is suing for gender discrimination, and her primary oppressor was a woman, then the firm's defense might argue that gender wasn't the motivating factor. The firm might say the supervisor was simply a bad manager.

But discrimination law doesn't require that the person committing discrimination be motivated primarily by animus. It requires that the discrimination occurred. A woman manager enforcing higher standards for women employees is still discriminating based on gender. The fact that the enforcer shares the gender of the victim doesn't make it less discriminatory.

This detail also raises a question about institutional culture. If the firm had created an environment where a woman manager felt she needed to treat women employees more harshly, that suggests a deeper cultural problem. It suggests that the firm's leadership had communicated—explicitly or implicitly—that women weren't fully trusted or were subject to different standards.

Supervisor and team environment are rated as the most critical factors for future employment at venture capital firms, highlighting the importance of interpersonal dynamics. (Estimated data)

Disability Discrimination: The Medical Leave Context

The lawsuit alleges disability discrimination in addition to gender discrimination. This likely stems from how Insight Partners handled Lowry's medical leaves.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, employers are required to make reasonable accommodations for employees with disabilities. If Lowry disclosed any disability or health condition that required accommodation, the firm was legally obligated to work with her to find appropriate solutions.

The suit alleges that upon her return from medical leave, she was placed on a different team and told that if the team didn't like her, she'd be fired. This could be characterized as a failure to accommodate. Instead of helping Lowry reintegrate into her role, the firm created an unstable situation where her continued employment depended on the approval of a new team.

Additionally, if the work environment that caused her health issues in the first place continued after her return, that could constitute a failure to accommodate or a hostile work environment based on disability.

Disability discrimination claims are sometimes easier to prove than general discrimination claims because the accommodations and modifications required are often documented. If Lowry requested specific accommodations after her medical leave (reduced hours, modified responsibilities, flexibility, etc.), and Insight denied them, that creates a clear record of the alleged discrimination.

The Venture Capital Industry's Structural Issues

While Lowry's case is specific to Insight Partners, it raises broader questions about how venture capital operates as an industry. Several structural factors make venture capital prone to the kind of problems alleged in this lawsuit.

First, venture capital is an industry with enormous information asymmetries. Limited partners (the investors who fund venture funds) have limited visibility into how those funds are managed internally. They see returns and portfolio performance. They don't see compensation practices, management dynamics, or workplace culture. This creates space for bad practices to persist.

Second, venture capital has historically been an insular industry. Many partners know each other, went to similar schools, and move in similar social circles. This creates networks that are difficult for outsiders to penetrate and makes it easier for problematic individuals to move between firms. If you have a reputation issue at one firm, you can sometimes simply move to another firm within the same network.

Third, venture capital compensation is heavily tilted toward partners and away from other professionals. Associates and vice presidents at venture firms make good salaries by most standards, but they make far less than the partners who control the firm. This creates a power dynamic where junior professionals are economically dependent on partners and have limited leverage.

Fourth, venture capital hasn't historically faced the same regulatory scrutiny as other financial services. Banks are regulated. Investment managers are regulated. But venture capital operates in a more permissive environment. This has allowed industry practices to evolve without external constraints.

These structural factors don't excuse Insight Partners' alleged behavior, but they help explain why such behavior persists in the industry.

Lowry was expected to be available for 17 hours daily, significantly exceeding the typical 8-hour workday. Estimated data.

Insight Partners' Silence and Legal Strategy

When Lowry's lawsuit was filed, Insight Partners did not immediately respond to requests for comment. This silence is a strategic choice. In litigation, defendants often face a decision about whether to respond publicly to allegations.

From a legal perspective, silence is sometimes the right choice. Anything the firm says can be used against it later. Public statements can be characterized as admissions or can create inconsistencies that plaintiffs' attorneys exploit. Firms often instruct employees and leaders to make no public comment while litigation is ongoing.

However, silence also has a cost. In the court of public opinion, silence can read as an admission of guilt or as arrogance. For a venture capital firm that depends on attracting talent and maintaining relationships with entrepreneurs and limited partners, being sued by a former executive and saying nothing can damage reputation.

Insight Partners will need to file a response to the lawsuit in court (likely a motion to dismiss or an answer). That response will articulate the firm's position. But public statements are a separate matter. As of the last available information, the firm hasn't chosen to address the allegations publicly.

Implications for Future Employment at Venture Capital Firms

For people considering roles at venture capital firms—particularly women and people from underrepresented groups—Lowry's case offers practical lessons.

First, thoroughly vet your potential supervisor and team. The most important factor in your experience at a firm won't be the firm's reputation or the compensation offered. It will be the person you report to and the team environment you're entering. If possible, speak with current and former employees about specific managers.

Second, understand the firm's compensation philosophy in writing. Don't rely on verbal assurances. Know what the market rate is for your role and experience level, and confirm that your offer aligns with that range. Get any special accommodations or flexibility in writing.

Third, be aware of the medical leave and accommodation process. How does the firm handle employees who need to take time off for health reasons? What accommodations is it willing to make? These questions should be answered before you join.

Fourth, document everything. Keep records of assignments, communications with supervisors, and any feedback you receive. If issues arise, you'll have documentation to support your account.

Fifth, know your legal rights. Familiarize yourself with employment law, particularly as it applies to discrimination and retaliation. Having an employment attorney's contact information isn't paranoid—it's practical.

Sixth, don't stay silent if problems emerge. This is the hardest advice to follow because speaking up carries risks. But as Lowry's case illustrates, documenting problems (ideally through formal channels) creates a legal record that protects you if the situation deteriorates.

The Broader Question: Can Venture Capital Change Its Culture

The venture capital industry has made public commitments to diversity and inclusion over the past decade. Major firms have hired chief diversity officers. Industry organizations have launched initiatives focused on underrepresented groups. Limited partners have increasingly asked about diversity metrics when evaluating funds.

But commitments and metrics don't necessarily translate into changed behavior. The fact that someone can bring a lawsuit alleging discrimination and retaliation at a major venture capital firm in 2025 suggests that the industry's transformation is incomplete.

There are several reasons why cultural change is difficult. First, the economics of venture capital haven't fundamentally shifted. Partners still control the firm and capture most of the returns. This creates power imbalances that are resistant to change. Second, venture capital has historically rewarded a particular management style—aggressive, hierarchical, demanding. Challenging that style means challenging what has worked (at least financially) for successful partners. Third, the industry is relatively small. Many partners have invested together over decades. Changing culture means challenging people and practices that are deeply embedded in professional networks.

Lowry's lawsuit is one data point among many that suggest cultural change in venture capital is proceeding more slowly than public statements might suggest. The question going forward is whether cases like this will accelerate that change or whether venture capital will find ways to insulate itself from legal and reputational consequences.

What Happens Next: The Lawsuit's Trajectory

Lowry's lawsuit will likely take years to resolve. Depending on how aggressively both sides pursue litigation, the case could involve extensive discovery, depositions, and expert testimony. It could settle, proceed to trial, or be appealed if either side loses.

The legal process is slow and expensive. For Lowry, pursuing this lawsuit requires sustained commitment and financial resources. Employment litigation doesn't typically result in massive awards unless the plaintiff can demonstrate significant damages. Lowry will need to quantify her losses (lost wages, lost benefits, emotional distress, career impact) and present that to a judge or jury.

For Insight Partners, the lawsuit creates legal costs, management distraction, and reputational risk. Even if the firm ultimately prevails, the process will be costly. And if the firm loses, the financial judgment could be substantial, and the reputational damage will be significant.

The case will also likely attract attention from other former and current Insight employees. If others have experienced similar treatment, they might come forward. If multiple allegations emerge, it strengthens any narrative that the problems are systemic rather than isolated to a particular manager or circumstance.

Lessons for the Venture Capital Industry and Beyond

Lowry's case offers several lessons for the venture capital industry and for corporate America more broadly.

First, it demonstrates that legal accountability matters. If firms believe they can violate employment law without consequences, they'll continue to do so. Lawsuits, even when they take years to resolve, create financial and reputational costs that incentivize better behavior.

Second, it shows the importance of documentation. Lowry's case is strong in part because she allegedly documented her medical condition, took formal medical leave, and sent a formal complaint letter. Employees who document problems systematically create evidence that's difficult for firms to refute.

Third, it illustrates that retaliation is illegal and that the timing of adverse actions matters. If a firm wants to terminate an employee, it should do so for documented reasons that existed before any complaint was filed. Firing someone a week after they send a formal complaint is legally indefensible.

Fourth, it reminds venture capital firms that insular networks and informal practices create vulnerabilities. Firms that operate without formal HR infrastructure, clear policies, and documented decision-making processes are more vulnerable to discrimination claims.

Fifth, it reinforces that boards and limited partners have a responsibility to ask hard questions about firm culture. If major investors were asking venture capital firms detailed questions about compensation practices, availability demands, and accommodation processes, it would create incentives for better practices.

The Role of Public Discourse in Shaping Accountability

One factor that distinguishes Lowry's case from earlier employment disputes is the role of public media and discourse. When details of her lawsuit were reported by TechCrunch and other outlets, the story reached a broad audience. That public attention creates pressure on Insight Partners and signals to other venture capital firms that similar behavior might face scrutiny.

Public discourse also validates people who have experienced similar treatment but may not have felt confident coming forward. When one person publicly alleges discrimination, it sometimes emboldens others to speak out.

However, public discourse can also be complicated for the parties involved. Lowry is now publicly associated with her lawsuit, which could affect her ability to find employment elsewhere (fairly or unfairly). Insight Partners is publicly characterized as a firm that allegedly engaged in discrimination and retaliation, which could affect its ability to recruit talent and attract investors.

The tradeoff between publicity and privacy is never easy. But in cases where one party has significantly more power (a major venture capital firm versus an individual employee), public discourse can be an important mechanism for accountability.

Conclusion: What Venture Capital Must Do Now

Kate Lowry's lawsuit against Insight Partners is ultimately a case about power, accountability, and the persistence of systemic problems in an industry that has made public commitments to change.

The allegations—extreme availability demands, compensation inequality, retaliation for complaining about discrimination—paint a picture of an environment where institutional power was used to dominate rather than to collaborate. Whether those allegations ultimately prevail in court, they represent a significant challenge to how Insight Partners and the broader venture capital industry conduct themselves.

For venture capital firms, the lesson is clear: the old model of informal practices, insular networks, and manager autonomy is no longer defensible. Employees increasingly understand their legal rights. Attorneys specializing in employment discrimination are more accessible. And public media is more interested in how the industry treats its people.

Firms that want to attract the best talent, maintain their reputations, and operate sustainably need to invest in formal HR infrastructure, clear policies, documented decision-making, reasonable work expectations, and transparent compensation practices.

For the venture capital industry as a collective, Lowry's case is a reminder that diversity and inclusion aren't just about metrics and hiring. They're about creating workplace environments where people from all backgrounds can actually succeed without facing discrimination, retaliation, or abuse.

The question before Insight Partners, and before the broader venture capital industry, is whether this lawsuit will catalyze real change or whether it will be treated as an isolated incident to be managed through litigation. The answer to that question will tell us a lot about whether venture capital is genuinely committed to transformation or whether public commitments to diversity and inclusion are simply window dressing.

Lowry's decision to pursue this case publicly, despite the personal costs and risks, is a form of whistleblowing. It's meant to expose problems and create pressure for change. Whether it succeeds in that goal will depend on how the venture capital industry responds.

FAQ

What are the main allegations in Kate Lowry's lawsuit against Insight Partners?

The lawsuit alleges disability discrimination, gender discrimination, and wrongful termination. Specifically, Lowry claims she was required to maintain extreme availability (6 a.m. to 11 p.m. daily, including holidays and PTO), was told by her supervisor that hazing would be more intense for her than for male employees, suffered health consequences requiring medical leave, was informed her compensation was 30% below market rate, and was terminated a week after formally documenting her complaints.

How does Kate Lowry's case compare to Ellen Pao's lawsuit against Kleiner Perkins?

Both cases involve allegations of discrimination and retaliation at prominent venture capital firms. Ellen Pao's 2012 case against Kleiner Perkins opened public discussion about how women are treated in venture capital, even though she ultimately lost the court case. Lowry's case, arriving over a decade later, raises the question of whether the industry has genuinely changed its practices or whether similar discrimination persists despite increased public awareness.

What is retaliation and why is the timing significant in this case?

Retaliation occurs when an employer takes adverse action against an employee in response to the employee reporting illegal conduct or asserting legal rights. In Lowry's case, the timing is significant because she was terminated approximately one week after sending a formal complaint letter to Insight Partners detailing her allegations. This narrow temporal gap is legally problematic for the firm because it suggests the termination was motivated by the complaint rather than by legitimate business reasons.

What are the legal implications of a 30% compensation gap for a woman employee in the venture capital industry?

A 30% compensation gap violates equal pay principles and can constitute gender discrimination. Beyond the immediate financial loss, wage discrimination compounds over a career through reduced retirement savings, limited investment capacity, and decreased financial flexibility. This gap is particularly significant in venture capital where salaries typically range from

How common are discrimination allegations against venture capital firms?

While comprehensive data is limited, there has been a documented increase in discrimination lawsuits against venture capital and tech firms over the past decade, particularly following Ellen Pao's case. Research from organizations focused on workplace equity indicates that women and underrepresented groups in venture capital and finance face persistent barriers to advancement, equitable compensation, and respectful work environments. However, not all workplace discrimination results in lawsuits—many instances go unreported or are resolved through confidential settlements.

What should employees consider before accepting a vice president role at a venture capital firm?

Prospective employees should thoroughly vet their potential supervisor and team dynamics, understand compensation philosophy in writing, clarify the medical leave and accommodation process, document communications and feedback systematically, familiarize themselves with relevant employment law, and be prepared to formally document and report concerns if they arise. Additionally, speaking with current and former employees about specific managers and firm culture can provide valuable insights beyond official recruiting materials.

What changes could venture capital firms implement to prevent discrimination and retaliation?

Firms could invest in formal HR infrastructure with clear policies, establish transparent compensation practices with documentation, implement structured decision-making processes for hiring and termination, provide regular training on discrimination and retaliation law for all managers, create independent channels for reporting concerns, conduct periodic compensation audits to identify pay gaps, and establish accountability mechanisms that hold managers responsible for violations. These measures would reduce legal vulnerability while creating healthier workplace environments.

How does limited partner oversight affect venture capital firm practices?

Limited partners, who invest capital into venture funds, typically have limited visibility into internal firm management, compensation practices, or workplace culture—they primarily monitor returns and portfolio performance. By increasing scrutiny of these areas, asking detailed questions about HR practices and compensation equity, and making their investments contingent on demonstrated commitment to fair workplace practices, limited partners could create strong economic incentives for venture capital firms to improve their internal operations and culture.

Key Takeaways

- Kate Lowry's lawsuit against Insight Partners alleges disability discrimination, gender discrimination, and wrongful termination, with specific claims about extreme availability demands and 30% compensation below market rate

- The firm terminated Lowry one week after she sent a formal complaint letter, creating strong legal evidence of retaliation under employment law

- The case parallels Ellen Pao's 2012 Kleiner Perkins lawsuit, suggesting that despite a decade of diversity commitments, venture capital still struggles with systemic discrimination

- Extreme availability requirements (6 a.m. to 11 p.m. daily, including holidays), combined with differential treatment based on gender, created a hostile work environment that caused medical leave

- Venture capital firms must implement formal HR infrastructure, transparent compensation practices, clear policies, and accountability mechanisms to prevent discrimination and retaliation

![Insight Partners Sued: Inside Kate Lowry's Discrimination Case [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/insight-partners-sued-inside-kate-lowry-s-discrimination-cas/image-1-1767656153284.jpg)