The Year Tech Lost Its Mind: A Retrospective on 2025's Most Absurd Moments

If you've been paying attention to the tech world lately, you know it's a circus. We've got brilliant engineers pushing the boundaries of AI dominance, venture capitalists throwing billions at moonshot ideas, and entrepreneurs with genuine visions for changing the world. But we also have a lot of people doing incredibly dumb stuff.

This year was no exception. While the headlines were dominated by serious developments—AI dominance battles, government lobbying by tech billionaires, autonomous vehicles hitting the streets—the internet's underbelly was filled with moments so ridiculous they almost seemed fictional. The kind of stories that make you shake your head, laugh, and wonder how we got here.

Here's the thing: these aren't trivial moments. Sure, they're funny on the surface, but they reveal something deeper about tech culture. They show us how celebrity status, lack of accountability, and the tech industry's tendency toward overhyped personalities can create an environment where genuinely smart people do genuinely dumb things. They expose the gap between the polished image these founders and CEOs project and their actual competence in everyday tasks. They highlight how a name or a reputation can become a commodity, and how social media can transform a simple mistake into a permanent part of your digital legacy.

So let's dive into 2025's greatest hits of incompetence, poor judgment, and unfiltered chaos. Because sometimes, the dumbest moments tell us the most important truths.

Mark Zuckerberg Sues Mark Zuckerberg: A Case of Mistaken Identity Gone Wrong

Let's start with what might be the most absurd legal case of the year: a real person named Mark Zuckerberg, a bankruptcy lawyer from Indiana, actually filed a lawsuit against Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Meta. Yes, you read that correctly. This wasn't a joke. It wasn't performance art. It was a legitimate legal action based on one man's legitimate frustration with another man's global dominance and name recognition.

The lawyer Mark Zuckerberg has been practicing law since before the CEO Mark Zuckerberg even existed. He's had his name longer, earned it through legitimate professional credentials, and established a practice. But once the CEO's Facebook became ubiquitous, everything changed. When people heard "Mark Zuckerberg," they thought of the social media billionaire, not the hardworking attorney in the Midwest.

This created a genuine problem for the lawyer. Try making a restaurant reservation when the host assumes you're prank calling. Try conducting business when people hang up thinking it's a joke. Try living your life when your own name has become synonymous with someone else's billion-dollar empire. The lawyer Mark Zuckerberg actually created a website—iammarkzuckerberg.com—to clarify that he was not the CEO. He documented his frustration: "I can't use my name when making reservations or conducting business as people assume I'm a prank caller and hang up. My life sometimes feels like the Michael Jordan ESPN commercial, where a regular person's name causes constant mixups."

The lawsuit itself was predictable in outcome—Meta's legal team is enormous and well-funded, while the lawyer Mark Zuckerberg is fighting against a global corporation with essentially unlimited resources. But what made this story resonate was what it revealed about modern celebrity culture. When you have a name that matches someone famous, you're not just dealing with casual confusion. You're battling a global brand that has spent decades and billions of dollars making their version of your name the default. You're essentially erased from your own identity.

This lawsuit highlighted a gap in digital identity law. What rights do you have to your own name when someone else has commercialized a version of it globally? How do you reclaim your identity when it's been subsumed by a corporate brand? The lawsuit probably didn't succeed—Meta's lawyers are too good for that—but it raised legitimate questions about digital dominance and identity rights that courts are still figuring out.

The absurdity of the situation masked a real problem. When you can't use your own name professionally without being treated as a fraud, that's not funny anymore. That's a failure of systems designed to protect individual identity while allowing corporate brands to monopolize common names.

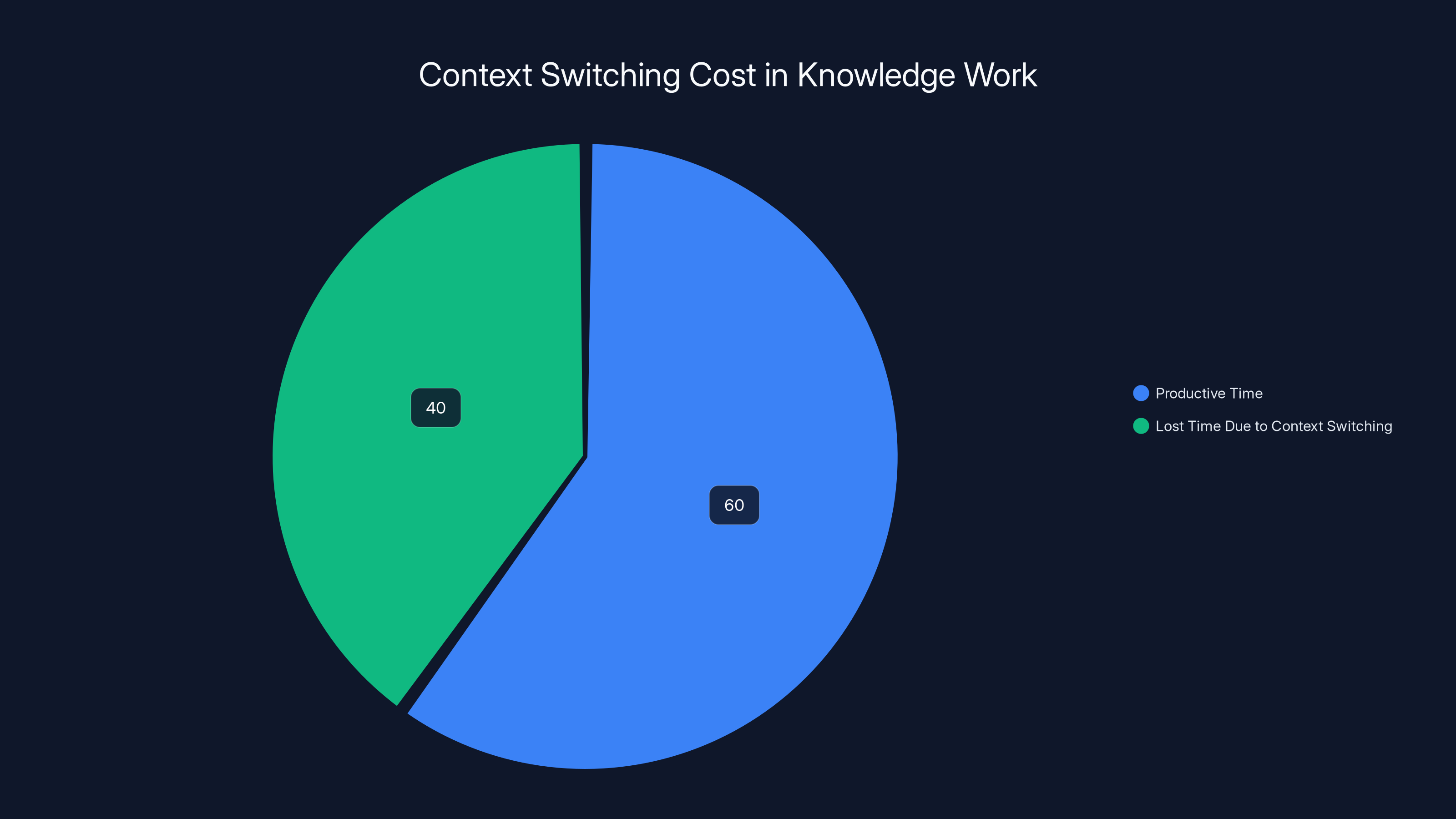

Context switching can account for up to 40% of lost productive time in knowledge work, highlighting the significant impact of multitasking.

Soham Parekh: The Superhuman Interviewer Who Broke the System

Now here's a story that divided the internet like few others: Soham Parekh, an engineer from India who, according to multiple startup founders, managed to work for 3-4 companies simultaneously while convincing each one that he was their full-time employee.

The story broke publicly on X (formerly Twitter) in July when Suhail Doshi, founder of Mixpanel, called out Parekh for working multiple jobs at once. Doshi had hired him, realized within a week that something was wrong, and fired him. But here's where it gets interesting: Doshi wasn't alone. Three other founders reached out that same day to say they were currently employing Parekh. This wasn't a one-off situation. This was a coordinated, sustained operation across multiple startups.

Parekh admitted it was true. He had been working for multiple companies simultaneously, lying to each about his availability and time commitment. By normal standards, this is fraud. You can't take a salary from four companies while only working for one. You can't sign employment contracts with false information about your availability. This should be a straightforward case of deception and dishonesty.

But something unexpected happened. Parts of the tech world didn't call him a scammer. They called him a legend.

Chris Bakke, founder of the job-matching platform Laskie, suggested on X that Parekh was actually a genius. "Soham Parekh needs to start an interview prep company," Bakke wrote. "He's clearly one of the greatest interviewers of all time. He should publicly acknowledge that he did something bad and course correct to the thing he's top 1% at."

This perspective reveals something fascinating about tech culture. We simultaneously claim to value integrity while celebrating impressive feats of deception. Parekh's ability to fool multiple startup founders was treated as an impressive skill, a sign of his persuasiveness and intelligence, rather than what it actually was: systematic fraud. The fact that he did it in an industry obsessed with "hustle" and "breaking the rules" probably helped his case.

Then there's the equity question. If Parekh was supposedly scamming companies for quick cash, why did he consistently choose equity packages over salary? Equity takes years to vest, especially at startups where you might get fired quickly. So what was his actual endgame? Was he really just trying to con people? Or was something else going on?

Some people suggested he might be training an AI agent through accumulated knowledge from multiple companies. Others theorized he was doing market research. The most interesting theory came from Aaron Levie, CEO of Box, who joked: "If Soham immediately comes clean and says he was working to train an AI Agent for knowledge work, he raises at $100M pre by the weekend."

That comment itself is revealing. In tech, the same actions that are fraud when motivated by greed become genius entrepreneurship when motivated by AI research. Parekh's story exposed this double standard and the weird incentive structures that make fraud seem less serious than innovation.

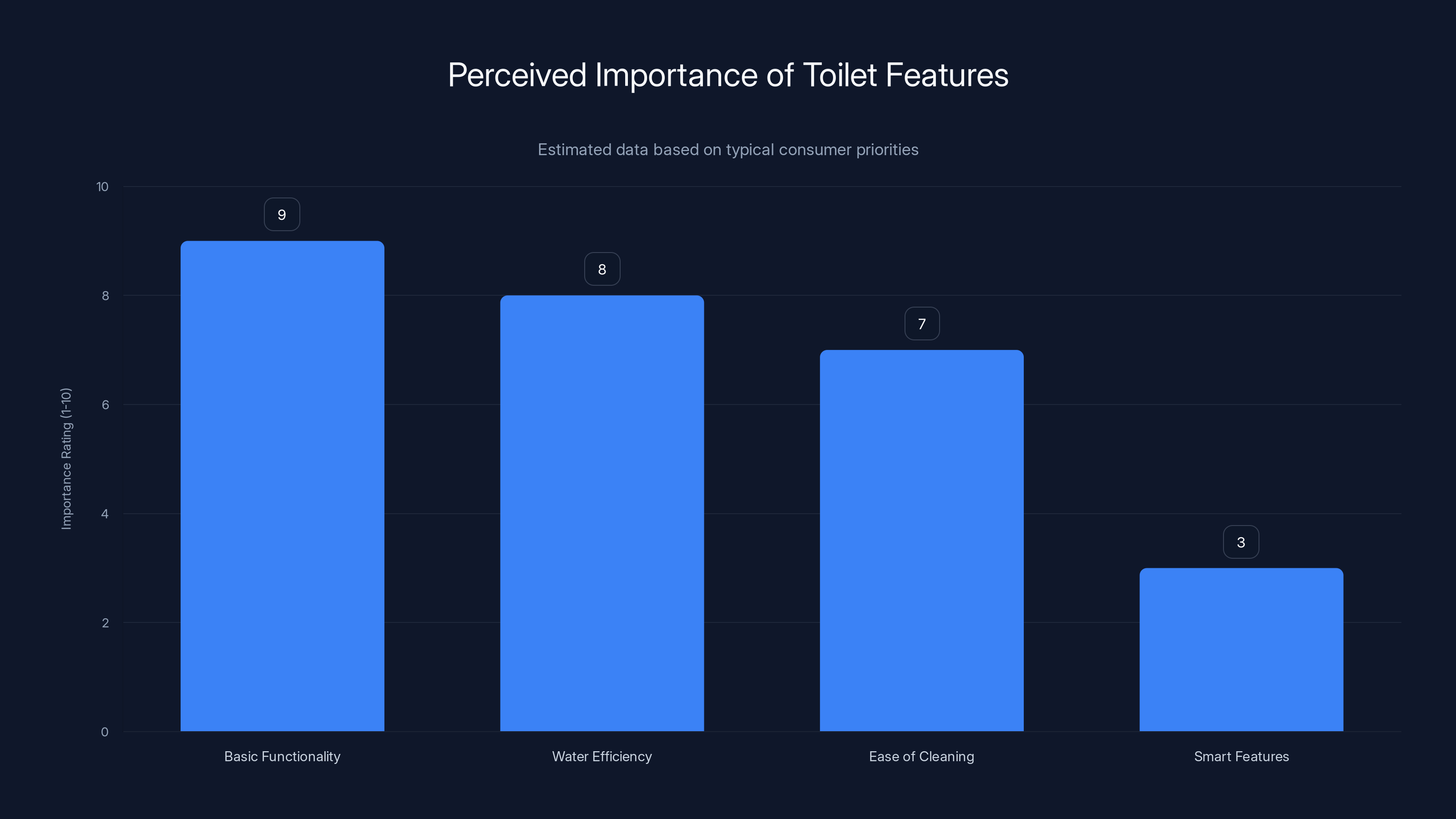

Consumers typically prioritize basic functionality and efficiency over smart features in toilets. (Estimated data)

Sam Altman's Olive Oil Disaster: When CEOs Cook

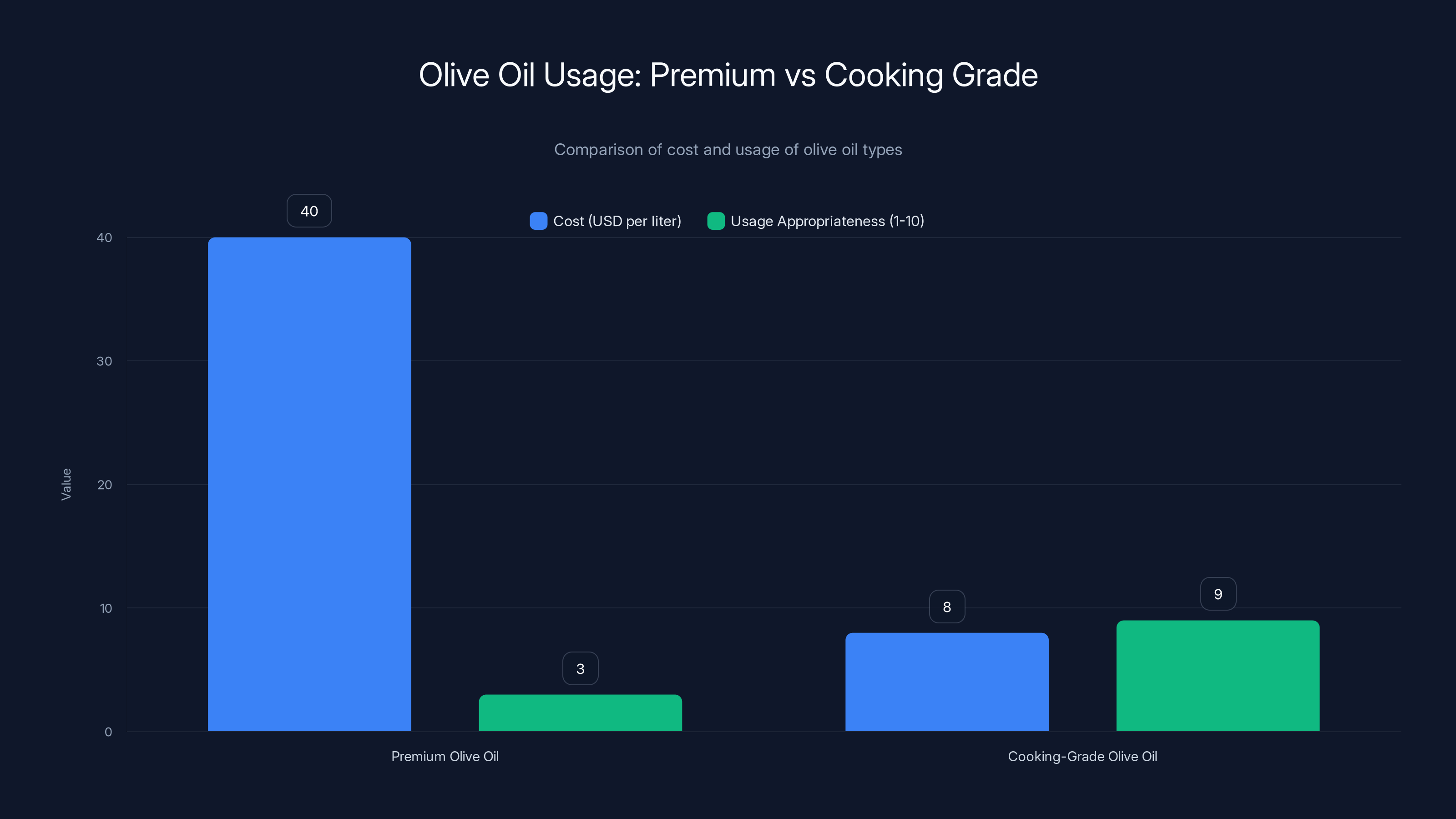

Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI, probably didn't expect his participation in the Financial Times' "Lunch with the FT" series would result in culinary criticism. But when he was filmed making pasta, food and tech intersected in the most ridiculous way possible. Not because his cooking was bad. Not because his pasta was mediocre. But because he fundamentally misunderstood how to use olive oil.

Here's the setup: Altman used a trendy olive oil brand called Graza, which markets two products. The first is "Sizzle," designed for cooking at high heat. The second is "Drizzle," designed for finishing dishes and toppings. This distinction exists because olive oil loses its flavor when heated to high temperatures. You don't want to use a $40 bottle of premium, cold-pressed olive oil for sautéing vegetables—you'd be wasting the flavor properties that justify the premium price. Instead, you want a neutral oil for cooking and reserve the fancy stuff for situations where the flavor will shine.

Altman used Sizzle (the cooking oil) correctly. But the criticism wasn't about Sizzle. It was about something deeper: his kitchen itself. According to Financial Times writer Bryce Elder, Altman's kitchen was a "catalogue of" expensive, luxury food items. The kind of kitchen that suggests someone who cares about premium quality, yet uses those premium products in completely wrong ways.

This is where the absurdity becomes a metaphor. Altman is worth billions. He can afford the absolute best ingredients. But having access to premium products doesn't mean you understand how to use them. It's not necessarily about incompetence—it's about not caring enough to learn. You have money, you buy expensive things, you use them however seems convenient at the moment.

The criticism also exposed something about tech wealth. There's this pattern where the ultra-rich buy the appearance of sophistication without developing actual sophistication. They purchase expensive items as status symbols, not because they understand the craftsmanship, history, or proper use case for those items. They read the price tag, not the instructions.

What makes this story perfect for understanding 2025's absurdity is that it matters so little and so much simultaneously. On one level, who cares how Sam Altman uses his olive oil? He's the CEO of one of the most powerful AI companies in the world. His olive oil technique doesn't affect Open AI's products or his leadership ability. On another level, it reveals a kind of obliviousness that's endemic to a certain class of tech billionaire. The idea that you can be successful at the highest levels while remaining fundamentally indifferent to things outside your narrow domain of expertise.

The Toilet CEO and Bathroom Innovation Theater

We promised you a story about toilets, and here it is. This year, a startup CEO decided to make headlines by redesigning the humble toilet. Not for any practical reason. Not because there was actually a market problem. But because bathroom innovation sounds important and futuristic.

The toilet redesign included various "smart" features that solved problems nobody was asking about. The kind of innovation that exists because venture capital can fund ideas, not because those ideas are actually needed. The company raised funding, got media coverage, and positioned itself as disrupting an industry that, frankly, doesn't need disruption.

This is a recurring theme in tech. We obsess over optimizing things that are already pretty good. Toilets work fine. They've been engineered to work reliably for over a century. Do they need AI capabilities? A smartphone connection? Probably not. But when you're a venture-backed startup with millions of dollars and the pressure to show usage metrics and growth, suddenly everything needs disruption.

The bathroom toilet story represents the absurdist endpoint of tech thinking: when optimization becomes divorced from actual need, when innovation becomes innovation for its own sake, when every product must be disrupted regardless of whether disruption improves anything.

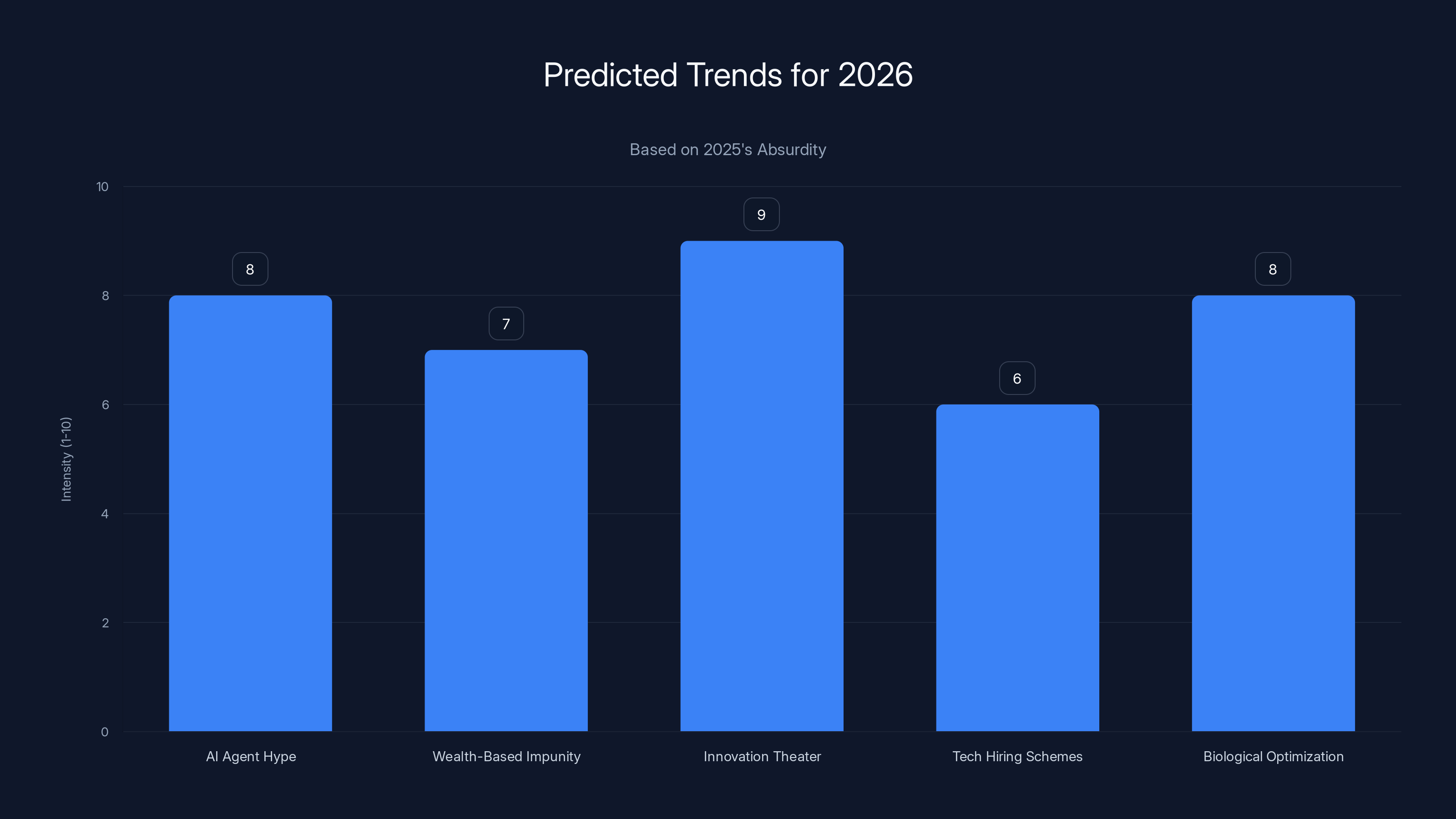

Predictions for 2026 suggest an increase in AI agent hype, innovation theater, and biological optimization, with continued wealth-based impunity and tech hiring schemes. Estimated data based on 2025 trends.

Bryan Johnson's Biological Age Obsession: Transhumanism Meets Narcissism

Bryan Johnson, the founder of Kernel and OS Fund, has become one of tech's most visible transhumanists. He spends millions annually trying to reduce his biological age, documenting every experiment, every diet change, every supplement, every measurement. His goal is simple but absurd: achieve a biological age younger than his chronological age.

The concept of biological age versus chronological age is real—certain lifestyle factors genuinely affect aging. But Johnson has taken this concept and weaponized it into a vanity project disguised as scientific research. He's spending millions on blood tests, supplements, and treatments, all tracked and shared publicly, all driven by the fundamental belief that he can optimize his way to immortality.

What makes this absurd isn't that Johnson is interested in longevity. What's absurd is the public theater of it. He posts photos and videos of his body, documents his cellular markers, discusses his supplement regimen—all to prove that he's essentially winning at being human. That with enough money and obsession, you can literally age backward.

The problem? Most of his claims are unverifiable, and some of his methods are questionable. He's spending millions on treatments with limited evidence, all while positioning himself as a pioneer in biological optimization. If it works, great. If it doesn't, he's just a billionaire who wasted money on supplements. Either way, the messaging is a masterclass in performative optimization.

Tech culture loves this. It loves the idea that with enough capital and determination, you can solve anything, even death. Never mind that the research backing biological age reversal is limited. Never mind that Johnson's specific interventions might not be generalizable to the broader population. The narrative is seductive: smart, rich person discovers the path to immortality.

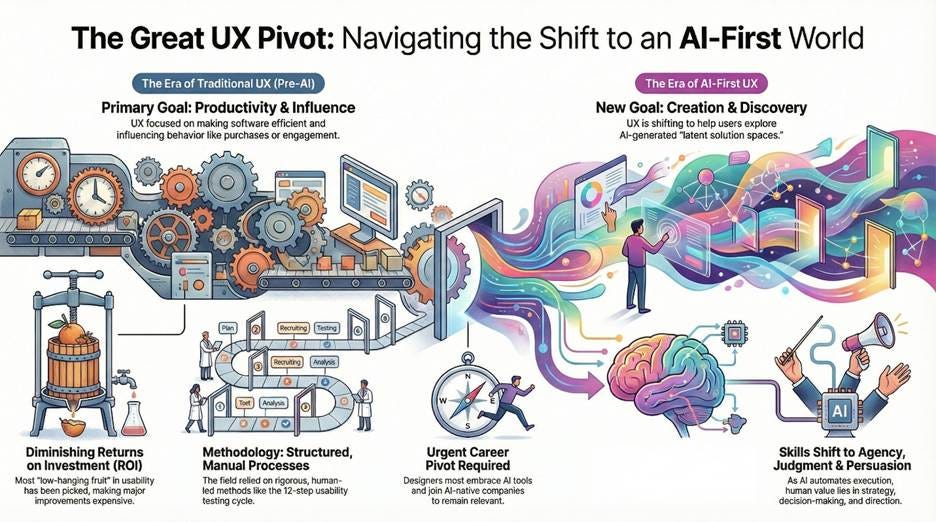

The AI Agent Moment: When Tools Become Workers

Much of the absurdity in tech this year revolved around AI agents—the idea that artificial intelligences could work as autonomous agents, taking jobs, conducting business, and making decisions independently. This concept became a meme, a joke, and simultaneously a genuine area of investment.

The obsession with AI agents revealed something important about tech's relationship with labor. Rather than building tools that augment human workers, the goal seemed to be building replacements. AI wasn't supposed to help Mark Zuckerberg make better reservations. It was supposed to make the reservation itself, understand the context, communicate with restaurants, and take full responsibility for the interaction.

The problem? Most AI agents don't actually work that way yet. They're far less capable than the hype suggests. They make mistakes, misunderstand instructions, and fail at tasks that seem simple to humans. But the narrative persisted anyway. Every startup seemed to claim they were building AI agents. Every investor seemed to believe it was the next paradigm shift. The disconnect between hype and reality was massive.

When the Soham Parekh story broke, suddenly people started suggesting that maybe he wasn't committing fraud—maybe he was training an AI agent to work multiple jobs. That joke worked because it captured something true about tech culture: we'll attribute any achievement to AI development before we'll credit actual human effort or, frankly, admit that something was just fraud.

Premium olive oils are significantly more expensive but less appropriate for high-heat cooking compared to cooking-grade oils. Estimated data.

The Intersection of Wealth, Celebrity, and Stupidity

What connects most of these stories is wealth. Mark Zuckerberg's lawsuit happened because another Mark Zuckerberg lacked the resources to fight a global brand. Soham Parekh could commit sustained fraud because tech hiring is so chaotic that verification failed. Sam Altman bought expensive olive oil because he's rich enough to not care about using it correctly. Bryan Johnson could spend millions on biological age optimization because he had the capital. The toilet CEO could raise millions for an unnecessary product because venture capital is designed to fund ideas regardless of viability.

Tech culture has created a system where wealth insulates you from consequences. You can sue the person who shares your name. You can defraud multiple startups. You can misuse expensive ingredients on a global platform. You can spend millions trying to prove immortality. And somehow, it all remains part of the quirky narrative that makes tech interesting.

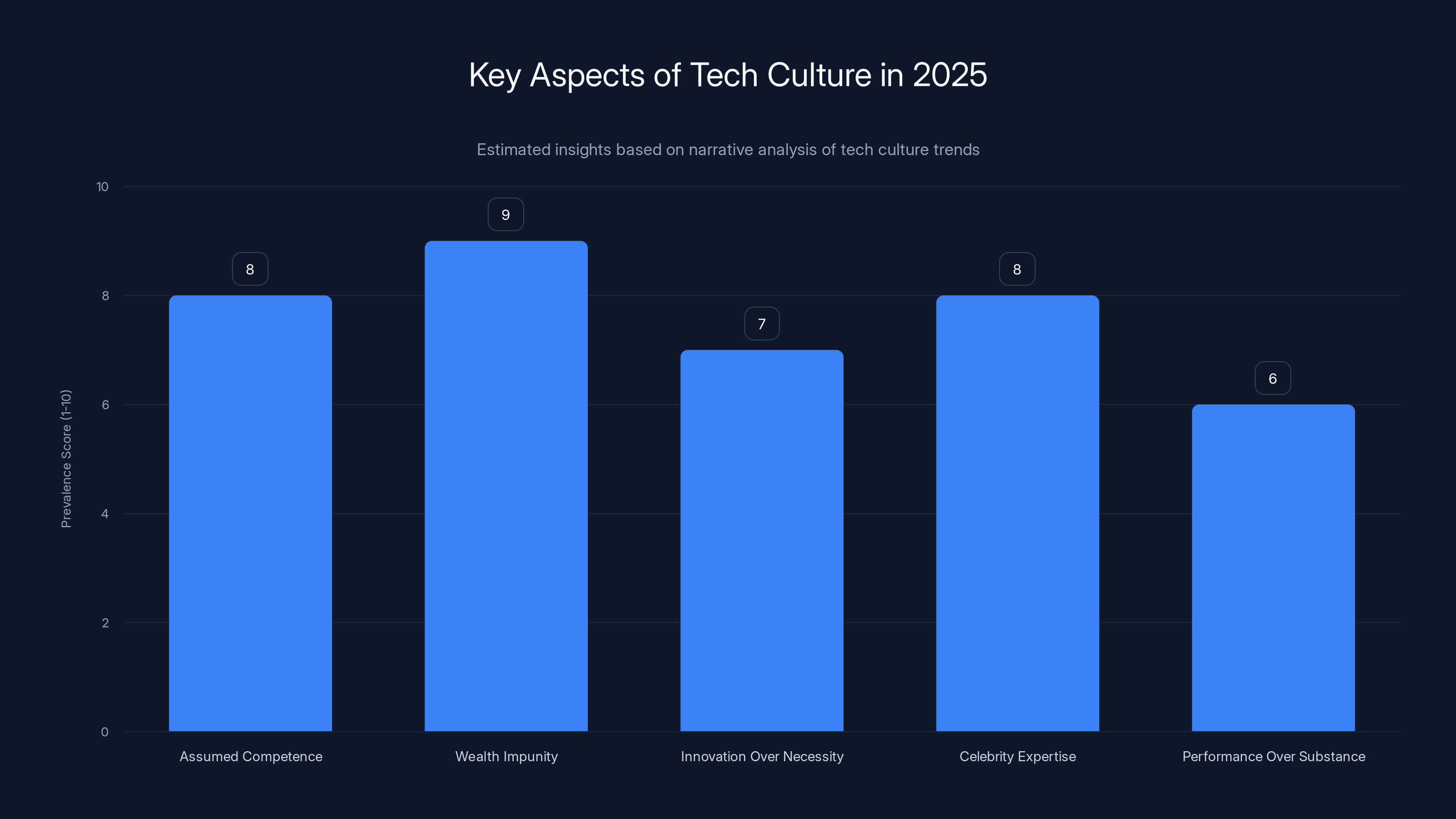

What These Moments Reveal About Tech Culture

If we zoom out, these absurd moments tell us something important about how tech culture works in 2025. We've created an industry where:

Competence is assumed but rarely verified. Soham Parekh could fool multiple founders because startups move so fast that basic verification falls through the cracks. We assume that if someone got hired at a good company, they must be competent. We skip the actual due diligence.

Wealth creates impunity. Mark Zuckerberg can sue another Mark Zuckerberg. Sam Altman can misuse expensive ingredients on camera. Bryan Johnson can spend millions on unproven treatments. None of them face real consequences because they have sufficient capital and platform to absorb criticism.

Innovation is valued over necessity. The toilet CEO could raise money not because toilets needed innovation, but because "disruption" is the default narrative in tech. We build things not because they're needed, but because we can, and because building something gives us a story to tell.

Celebrity and expertise are conflated. We treat tech billionaires as experts on everything—politics, science, AI, you name it. Sam Altman's opinion on olive oil shouldn't matter, but because he's the CEO of Open AI, someone's critiquing his technique.

Performance matters more than substance. Bryan Johnson's documented biological age experiments matter not because they're scientifically rigorous, but because they're documented and shareable. The theater of optimization matters more than actual optimization.

Estimated data suggests that wealth impunity and assumed competence are the most prevalent aspects of tech culture in 2025, reflecting a focus on superficial metrics over substantive verification.

The Role of Social Media in Amplifying Absurdity

None of these stories would have achieved the cultural resonance they did without social media. X (formerly Twitter) specifically became the platform where tech absurdity got amplified, memed, and discussed constantly. Every stupid moment became a conversation. Every ridiculous situation became a trend.

This served a purpose. Social media gave voice to legitimate grievances (Mark Zuckerberg's name issue) and exposed fraud (Soham Parekh). But it also transformed these moments into entertainment. We laughed at Sam Altman's olive oil mistake. We debated whether Soham Parekh was a genius or a criminal. We treated tech billionaires' personal decisions as public spectacle.

The absurdity became the point. Tech was no longer just building products and companies. It was also producing content, drama, and memes. Every founder was simultaneously a business leader, a public personality, and a source of entertainment content.

How These Moments Predict Future Tech Trends

If 2025's absurd moments tell us anything, it's what tech will focus on going forward. The obsession with AI agents suggests we'll continue building worker replacements rather than worker augmentation tools. The Soham Parekh situation suggests that hiring and verification will remain chaos that bad actors can exploit. The Bryan Johnson longevity obsession suggests we'll continue conflating wealth with wisdom, and consumption of products with actual achievement.

The fact that these moments are absurd, yet nobody in tech seems embarrassed by them, suggests that the industry has lost its ability to distinguish between important problems and performative optimization. Everything is an opportunity. Everything is disruption. Everything requires innovation.

Maybe that's the real absurdity. Not any single moment, but the fact that in an industry supposedly built on logic and reason, we've created systems that reward the irrational, protect the powerful, and celebrate the absurd.

Learning From Tech's Absurdity

For those outside tech looking in, these moments might seem inconsequential. Who cares if Sam Altman uses olive oil wrong? Who cares if a startup builds an unnecessary toilet? These are rich people doing rich people things, and they don't affect the rest of us.

But they do, indirectly. Tech culture sets trends for the rest of business. If tech treats verification as optional, other industries will follow. If tech celebrates fraud when done skillfully, other industries might too. If tech conflates celebrity with expertise, society will continue doing the same. If tech builds solutions to problems that don't exist, that becomes the default approach to innovation everywhere.

The absurd moments of 2025 weren't just funny. They were cautionary tales about what happens when an industry prioritizes growth and disruption over actual utility. They showed us what happens when wealth creates impunity. They demonstrated why we need better systems for verification and accountability.

Most importantly, they reminded us that even the most successful people in tech are just people. They use olive oil wrong. They fight about names. They get taken in by people who interview well. They spend millions trying to beat death. And somehow, all of that continues to be celebrated as innovation.

The Meta-Absurdity: Tech Commenting on Its Own Absurdity

Perhaps the most absurd part of 2025's tech moments was how the industry responded. Rather than taking a step back and asking whether we'd gone too far, tech doubled down. We turned every stupid moment into a lesson, a business opportunity, or a meme. We extracted value from absurdity itself.

When Soham Parekh's story broke, within hours there were people suggesting it was a clever AI training strategy. When Sam Altman used olive oil wrong, people made it a lesson about kitchen design and luxury goods. When Bryan Johnson spent millions on biological optimization, investors saw a new market segment.

Tech isn't just absurd. It's absurd about its absurdity. The industry has developed a self-aware humor about its own excesses, which somehow makes those excesses continue. We laugh at the stupidity while funding more of it.

This might be the truest observation about 2025's tech culture: we've become so sophisticated at discussing our own dysfunction that we've lost the ability to actually fix it. We're like a person who makes elaborate jokes about their terrible habit while continuing the habit anyway.

What 2026 Might Bring: Predictions Based on 2025's Absurdity

If past is prologue, 2026 will likely feature more of the same, but escalated. We'll probably see:

More AI agent claims with less actual functionality. The hype around AI agents will continue despite the technology not working as promised. Companies will build "AI agent platforms" that are mostly just tools with better marketing.

Continued wealth-based impunity. Tech billionaires will continue making mistakes, and we'll continue treating those mistakes as learning opportunities rather than failures. The systems that insulate them from consequences won't change.

Innovation theater reaching new heights. Someone will probably raise $100 million to solve a problem that doesn't exist. And we'll all talk about it, debate whether it's genius or stupid, and ultimately treat it as inevitable because that's how tech works.

More Soham Parekhs. The verification systems in tech hiring won't improve significantly, meaning more people will likely pull off similar schemes. Each one will generate debate about whether it's fraud or genius.

Biological optimization becoming more visible. More billionaires will follow Bryan Johnson's path, spending enormous amounts on life-extension treatments and documenting the process. We'll have an entire ecosystem built around wealthy people trying to optimize themselves.

The absurdity isn't ending. It's just getting more creative.

FAQ

What made 2025 such a notable year for tech absurdity?

2025 combined record-breaking venture capital investment, unprecedented AI hype, and a celebrity-driven tech culture that produced numerous moments where billionaires and well-funded startups engaged in behaviors ranging from legally questionable to downright silly. The year was notable not because individual incidents were historically unprecedented, but because the sheer density and visibility of absurd moments exposed systematic issues in how tech culture operates.

Why did people defend Soham Parekh despite his clear fraud?

Soham Parekh's story highlighted a fascinating contradiction in tech culture: we celebrate impressive feats of deception when they demonstrate unusual skill or intelligence. His ability to simultaneously work for multiple companies was viewed not just as fraud, but as an impressive exploit of broken hiring systems. Additionally, some suggested his actions might actually be training an AI agent, which would transform criminal behavior into entrepreneurship in the eyes of tech investors.

Is Sam Altman's olive oil mistake actually important, or just entertainment?

While the olive oil incident itself is trivial, it serves as a metaphor for a larger problem: the tendency of ultra-wealthy tech leaders to purchase the appearance of sophistication without developing actual expertise. Altman's mistake revealed a common pattern where billionaires buy expensive products without understanding how to use them properly. More broadly, it highlights how celebrity CEOs are treated as experts on everything, even things completely outside their domains of knowledge.

What does the Mark Zuckerberg lawsuit reveal about digital identity rights?

The lawsuit between two people named Mark Zuckerberg exposed a genuine gap in digital identity law. When one person has commercialized a name globally through a billion-dollar company, how do other people with that same name protect their individual identity and reputation? The case raises important questions about whether global corporations should have unlimited rights to commercialize common names, and what protections individuals should have when they share names with famous people.

Why is the tech industry so resistant to acknowledging its own absurdity?

The tech industry has developed a sophisticated self-aware humor about its dysfunctions, which paradoxically enables those dysfunctions to continue. By treating absurdity as entertaining rather than problematic, the industry maintains the status quo while appearing self-critical. This allows wealthy founders and investors to continue making questionable decisions without real consequences, because the community treats those decisions as part of the unique and quirky nature of tech culture.

How do these absurd moments reflect larger problems in tech culture?

These moments collectively reveal that tech culture prioritizes growth and disruption over actual utility, that wealth creates impunity from consequences, that verification and accountability systems are broken, and that celebrity status is conflated with expertise. The absurdity isn't random chaos—it's the natural result of systems that reward innovation regardless of necessity, that allow the wealthy to escape accountability, and that treat every idea as worth funding and every billionaire as worth listening to.

What can the broader business world learn from tech's 2025 absurdities?

The rest of the business world can see in tech's absurdities what happens when verification is treated as optional, when growth becomes the only metric that matters, and when celebrity status substitutes for actual expertise. These cautionary tales suggest that sustainable business practices require verification systems, meaningful accountability, and a willingness to distinguish between solutions that create actual value and those that create only the appearance of innovation. The tech industry's failures are the broader economy's warning signs.

The Bottom Line: Why Absurdity Matters

At the end of 2025, the tech industry found itself in a peculiar position. It had achieved remarkable things—AI capabilities that seemed impossible five years prior, companies like Anthropic and Open AI pushing the boundaries of what's possible with language models. Yet simultaneously, it was producing an endless stream of absurd moments that exposed the industry's blind spots, its reliance on celebrity over expertise, and its inability to distinguish between important innovation and performative disruption.

The question for 2026 and beyond isn't whether tech will continue producing absurd moments. It will. The question is whether the industry will develop the self-awareness and accountability structures to actually learn from them, or whether absurdity will simply become another expected feature of how tech operates.

Based on what we saw in 2025, I'm not optimistic. But I'm definitely watching.

Key Takeaways

- 2025 produced an unprecedented density of absurd tech moments that exposed systemic problems with verification, accountability, and innovation incentives

- Wealth creates impunity in tech culture, allowing billionaires and well-funded founders to escape consequences that would affect ordinary people

- The tech industry conflates celebrity status with expertise, treating rich founders as authorities on topics completely outside their domains of knowledge

- Innovation theater—creating solutions to problems that don't exist—remains heavily funded because growth and disruption matter more than actual utility

- These absurd moments aren't random chaos; they're natural outcomes of systems that reward disruption over necessity and protect the wealthy from accountability

Related Articles

- ChatGPT Judges Impossible Superhero Debates: AI's Surprising Verdicts [2025]

- Rotel DX-5 Review: Compact Integrated Amp Hero [2025]

- Supply Chain, AI & Cloud Failures in 2025: Critical Lessons

- Tech Resolutions for 2026: Master Your Phone Like a Pro [2025]

- Lego CES 2026 Press Conference: How to Watch Live [2025]

- Political Language Is Dying: How America Lost Its Words [2025]

![The Silliest Tech Moments of 2025: From Olive Oil to Identity Fraud [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-silliest-tech-moments-of-2025-from-olive-oil-to-identity/image-1-1767191739521.jpg)