The Mysterious Russian Space Station Leak: A Six-Year Crisis Finally Resolved

When you're orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour inside a sealed metal tube, any hint of atmospheric loss feels like a ticking clock. For nearly half a decade, engineers at both NASA and Roscosmos have been hunting for something most of us would never see with our naked eyes: microscopic cracks slowly bleeding precious air into the vacuum of space.

The problem wasn't dramatic. No alarms screamed. No cosmonauts scrambled in emergency suits. Instead, it was the kind of creeping concern that keeps mission planners awake at night. Pressure readings showed a subtle but consistent loss of atmosphere from the Pr K module, a small transfer corridor on the Russian segment of the International Space Station. Year after year, the leak persisted despite repeated repair attempts. Then, in 2024, something alarming happened: the rate of atmospheric loss doubled.

That's when NASA officials upgraded their assessment from "manageable problem" to "high likelihood, high consequence risk." Translation: if this got worse, it could compromise the entire station.

But here's where the story shifts. After extensive inspections and a series of sealing operations, something unexpected occurred. The leak stopped. The atmospheric pressure in the transfer tunnel stabilized. After spending roughly six years playing cosmic hide-and-seek with microscopic cracks, the international partnership finally achieved what had seemed impossible.

This breakthrough represents far more than a simple repair success. It's a masterclass in persistence, orbital engineering, and how two space agencies can collaborate even during geopolitical tension. It also raises important questions about the aging infrastructure we depend on and what challenges lie ahead for humanity's foothold in space.

TL; DR

- Six-year leak crisis resolved: Russia's Pr K module on the ISS, which has been slowly losing atmosphere since 2019, finally stopped leaking after recent sealing operations

- Leak rate doubled in 2024: The problem escalated from a manageable issue to a "high consequence" risk when atmospheric loss accelerated, prompting urgent action

- Microscopic cracks caused the problem: Hairline fractures in the transfer tunnel between the Zvezda module and an airlock created the leak sites that cosmonauts spent years trying to locate

- Cosmonauts used dust detection method: Russian crews manually searched for leaks by closing hatches, reopening them, and looking for dust accumulation near cracks

- Patented sealant proved effective: A specially developed sealant called Germetall-1 was repeatedly applied to seal the microscopic fractures

- Aging hardware is the underlying issue: The Zvezda module, launched in 2000, is 25 years old, and engineers still don't understand why the cracks developed

- ISS pad repairs progressing: Russia expects to return the Baikonur Cosmodrome's primary launch pad to service by March 2026 after a mobile platform failure

Understanding the Pr K Module: The ISS's Vulnerable Transfer Point

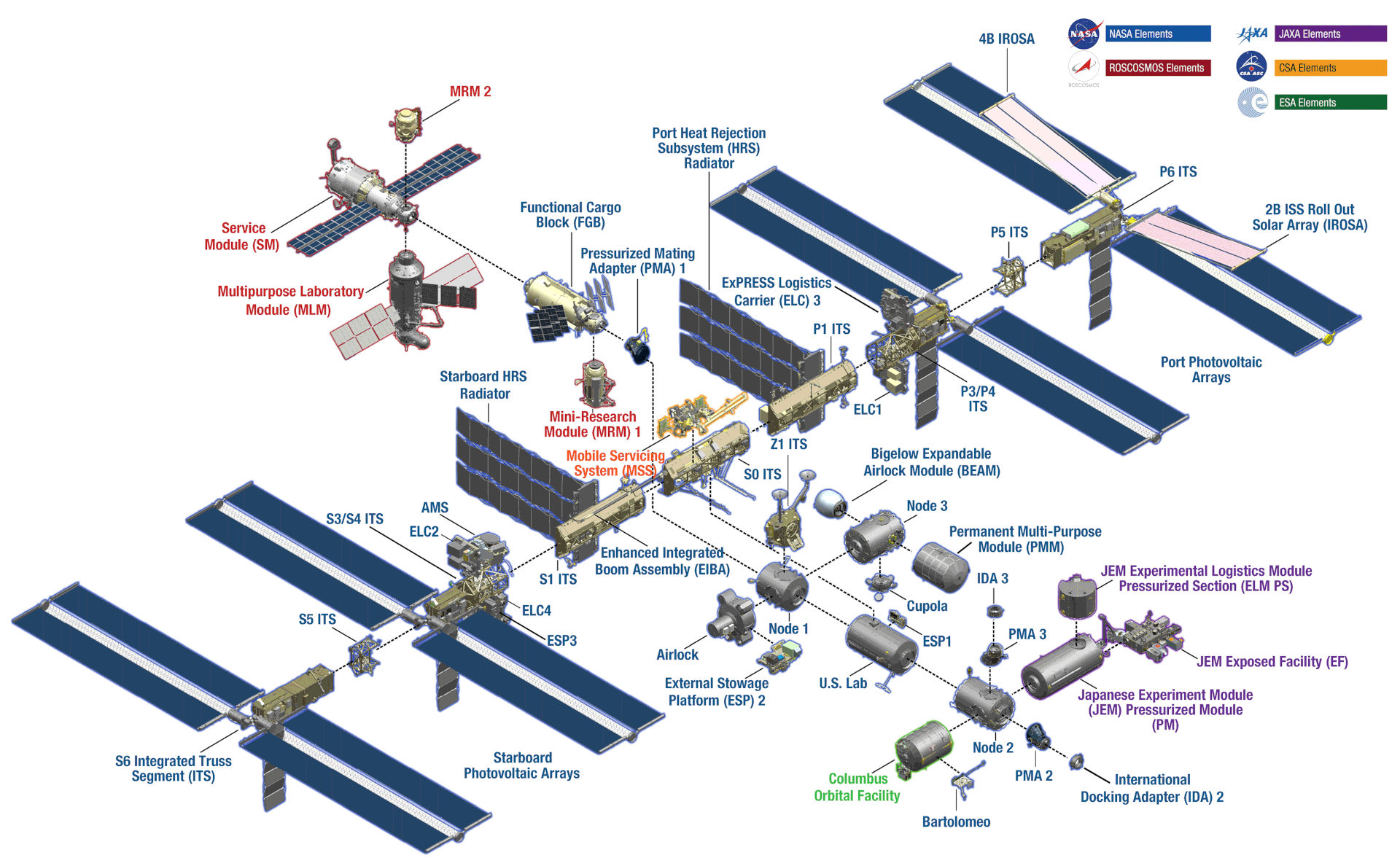

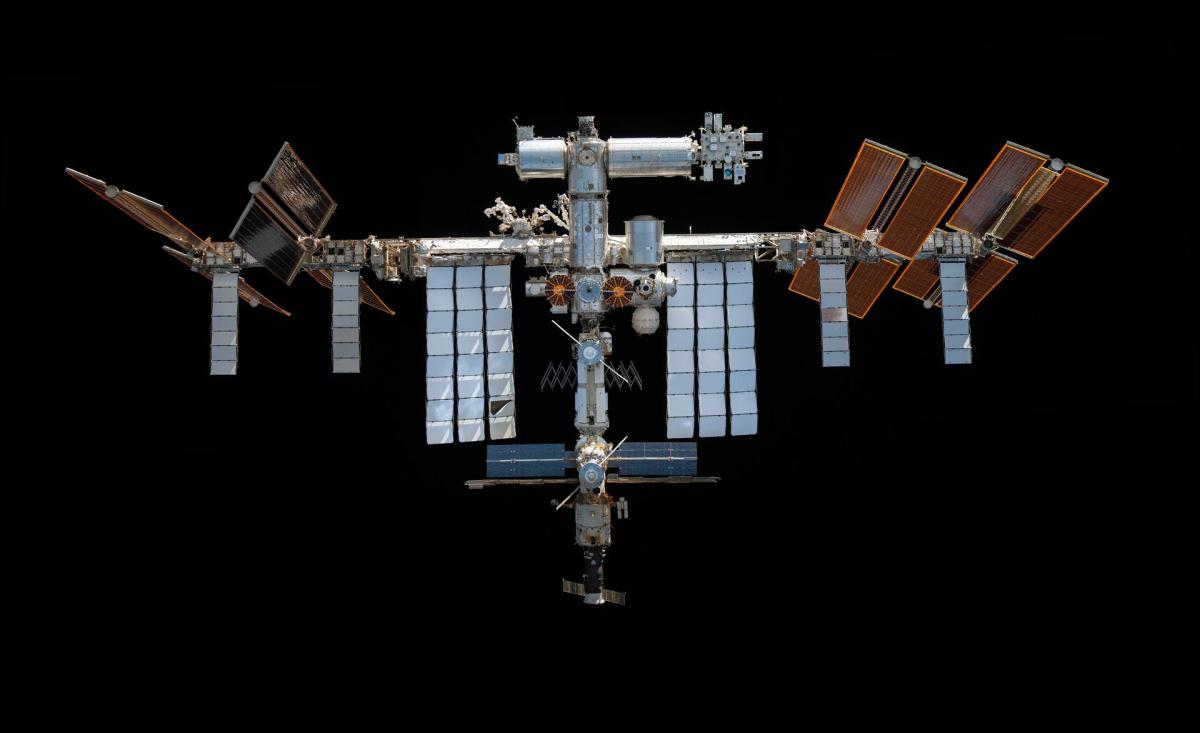

The International Space Station isn't a single unified structure. It's more like a complex puzzle where different national modules connect together, each with its own purpose, systems, and sometimes, its own problems. The Russian segment, managed by Roscosmos, consists of several interconnected modules that provide vital life support, propulsion, and docking capabilities.

The Pr K module sits in a strategically important but mechanically vulnerable position. It functions as a transfer corridor between the Zvezda Service Module and the station's airlock systems. Think of it as the hallway connecting two apartments. Small, often overlooked, but essential for movement and access.

Zvezda itself is one of the oldest continuously occupied modules in the entire station. Launched in July 2000 aboard a Proton rocket from Baikonur, it's older than many of today's smartphones. It houses critical systems including the main computer that manages the Russian segment, environmental controls, and backup propulsion. When Zvezda arrived at the station, it was cutting-edge technology. By 2024, it was approaching a quarter-century of orbital service without the benefit of replacement parts that were never designed for 25-year lifespans.

The transfer tunnel's location makes it particularly important. Cosmonauts need to move between modules frequently to perform maintenance, conduct experiments, and manage station systems. Any restriction in movement due to hazardous conditions cascades throughout the entire facility. When engineers began detecting pressure loss in the Pr K, they weren't just looking at a minor inconvenience. They were facing a situation where the station's operational capacity could be compromised.

The module's design incorporates aluminum and composite materials that, while suitable for space, undergo gradual degradation when exposed to the thermal cycling of orbital environments. Day-night cycles occur every 90 minutes in low Earth orbit, creating thermal stresses that ordinary Earth-based engineering never accounts for. Metal expands and contracts. Micro-stresses accumulate. Sometimes, after two decades, tiny cracks appear in places engineers never anticipated.

The Timeline: How a Six-Year Problem Developed

The first hint of trouble emerged in 2019, when technicians noted unusual pressure readings in the transfer tunnel. Initially, the loss was minimal, measured in fractions of a percent per day. It seemed manageable. Engineers assumed it might be a slow micro-meteoroid strike or perhaps a minor manufacturing defect finally showing itself after 19 years in space.

But atmospheric leaks don't magically fix themselves. The pressure continued to drop at a steady, predictable rate. This consistency was actually informative: it told engineers the problem wasn't a single dramatic event like a meteoroid impact, but rather chronic leakage from one or more small sources.

Roscosmos assigned cosmonauts to investigate. This is where the story becomes genuinely interesting. Finding a microscopic leak in a sealed module orbiting 250 kilometers above Earth isn't like finding a leak in a garden hose. You can't just listen or feel for it. You can't see it. You need to be clever.

The technique cosmonauts developed was elegant in its simplicity: isolation and dust detection. They would close the hatch to the Pr K module, effectively sealing it from the rest of the station. Then they'd wait and monitor pressure. After sufficient time, they'd reopen the hatch and carefully examine the module's interior, looking for tiny accumulations of dust or oxidation patterns that might indicate where air was escaping.

This process, repeated many times over months and years, is the definition of painstaking work. You're looking for something smaller than a human hair in an environment where dust particles behave differently due to microgravity. Success requires immense patience and meticulous attention to detail.

When cosmonauts identified suspected leak sites, they applied a specially formulated sealant called Germetall-1. This compound was specifically developed for orbital use and eventually received patent protection due to its unique properties. The sealant had to withstand vacuum, thermal cycling, and the physical stresses of orbital mechanics while remaining effective for years.

The process would then repeat. Close the hatch. Monitor pressure. Open the hatch. Search for more leaks. Apply more sealant. This cycle continued for years, creating a frustrating pattern where each repair seemed to be only a temporary bandage rather than a permanent solution.

The Acceleration of 2024: When the Problem Got Worse

For the first four years, the leak rate remained relatively constant, even if the absolute pressure loss was concerning. Engineers tracked it, managed it, and made plans to eventually address it comprehensively. But 2024 brought an unwelcome development: the rate of atmospheric loss doubled.

This acceleration was significant for several reasons. First, it suggested the underlying problem was worsening, not stabilizing. Second, it indicated that the existing cracks might be expanding, or new cracks might be developing. Third, it created genuine concern about cascade failures where one growing crack could lead to others.

When NASA reviewed this development, they reassessed the risk classification. The leak moved from "manageable" to "high likelihood" and "high consequence." In aerospace terminology, this is serious language. It means the problem has a realistic probability of occurring, and if it does, the consequences could be severe.

A high-consequence leak could force the evacuation of portions of the station. It could impact crew safety. It could compromise research operations. In the worst-case scenario, it could contribute to structural damage that affects the station's long-term viability.

Roscosmos intensified their efforts. More inspection sorties were planned. The sealant application became more aggressive. Engineers began exploring whether there might be design defects in how modules connected to the transfer tunnel, or whether the structural failure was more extensive than initially believed.

The clock seemed to be ticking. Engineers publicly discussed contingency plans. If the leak couldn't be controlled, they might need to restrict access to portions of the Russian segment or implement emergency procedures.

The Breakthrough: What Changed and Why

Details about exactly what operations led to the leak stoppage aren't fully transparent in public statements, but NASA confirmed in early 2026 that after "additional inspections and sealing activities," the pressure in the transfer tunnel stabilized. The atmospheric loss stopped.

Several factors likely contributed to this success. First, the increased frequency of inspection sorties probably meant cosmonauts were identifying and treating leaks more quickly. Second, they may have discovered the primary leak source and applied a more comprehensive seal. Third, environmental factors might have changed. For instance, if the initial cracking was related to structural movement or thermal cycling patterns, any slight change in the station's orientation or thermal management could have affected the leak rate.

It's also possible that the repeated application of Germetall-1 sealant had a cumulative effect. With each application cycle, more sealant accumulated in the microstructure of the cracks, gradually filling them more completely. Eventually, the seal became sufficient to stop atmospheric loss entirely.

The stabilization is genuinely good news, but it's not without caveats. Engineers remain cautious. The underlying structural cracks are still present. They haven't disappeared. They've simply been sealed. This means the fundamental vulnerability persists, and new cracks could develop in the future.

NASA and Roscosmos committed to continuing monitoring and investigation. This isn't bureaucratic language. It reflects genuine uncertainty about what caused the cracking and whether additional cracks might develop elsewhere in the module.

The Underlying Question: Why Did the Cracks Develop?

Here's where the story becomes genuinely puzzling: despite six years of investigation, engineers still don't fully understand why the Zvezda module developed structural cracks in the first place.

This isn't a simple oversight. The module was designed by expert engineers, built to specifications, and thoroughly tested before launch. Yet something about its design, the materials used, or its operational environment caused microscopic fractures to develop.

Several hypotheses exist. The thermal cycling in low Earth orbit is extreme. The module experiences 16 complete day-night cycles per 24 hours, with temperatures ranging from deep cold in shadow to significant heat in direct sunlight. Over 25 years, this creates millions of thermal stress cycles. The accumulated effect on metal structures can be surprising.

Second, there's the issue of material degradation. Aluminum and composite materials don't simply age gracefully in space. They're exposed to solar radiation, ultraviolet light, and atomic oxygen bombardment. These environmental factors can weaken material properties in ways that ground-based testing doesn't fully replicate.

Third, there's the possibility of manufacturing defects that only appeared after years of stress cycling. A microscopic flaw in the material or welding could have been dormant for two decades before becoming apparent.

Fourth, the station's operational stresses are different from what was modeled. The combined mass, the way modules connect, the forces from docking events and propulsion burns all create stresses that real-world operation might intensify in ways simulations didn't predict.

The honest answer is that engineers are still investigating. The lack of a definitive explanation isn't a failure of analysis; it's a reflection of how complex orbital mechanics and material science interact in ways that even sophisticated engineering can't fully predict.

The Inspection Process: How Cosmonauts Hunt Invisible Leaks

The leak hunting process deserves its own examination because it reveals something important about how humans operate in space and the limitations of even sophisticated technology.

Cosmonaut leak detection relies partially on modern sensors and instrumentation, but also heavily on analog techniques developed through practical experience. The process typically begins with pressure monitoring. Instruments track whether the sealed module is losing atmospheric pressure and at what rate.

Once technicians confirm a leak exists, they must find it. This is where the process becomes genuinely challenging. The leak sites are likely very small, possibly measured in fractions of a millimeter. They're invisible. They might be in hard-to-reach areas. They might be obscured by other equipment.

Cosmonauts employ several detection methods. One involves introducing a tracer gas, which escapes through the leak and can be detected with sensors. Another involves dust tracers: cosmonauts release fine powder or dust particles, which follow air currents toward the leak. In microgravity, this requires skill because dust doesn't behave like it does on Earth.

Another technique involves visual inspection combined with what might be called "experience intuition." Cosmonauts who've worked on spacecraft for years develop an almost instinctive sense of where problems are likely to occur. They know which connections are prone to stress, which materials degrade faster, and which areas experience the most thermal cycling. This knowledge, combined with systematic visual inspection, has proven remarkably effective.

Once a leak is located, the sealant application process begins. Germetall-1 is carefully applied to fill the microscopic cracks. The application must be precise. Too little, and it won't seal the leak. Too much, and it might create other problems like outgassing or structural weakness.

After application, the cosmonauts close the hatch and wait for the sealant to cure. Different environmental conditions can affect cure time. In the vacuum of space, with temperature variations and no atmospheric pressure to assist the process, cure times can be different from ground-based applications.

Then comes the verification: reopening the hatch and checking whether pressure remains stable. If it does, the repair is successful, at least temporarily. If not, more leaks await discovery.

The entire process is repetitive, labor-intensive, and requires exceptional attention to detail. The fact that it took multiple cycles over years reflects how challenging it is to identify and repair microscopic structural flaws in an environment where humans can only perform maintenance during carefully planned spacewalks.

The Germetall-1 Innovation: A Patented Solution

The sealant used to address the leak deserves recognition because it represents genuine innovation in materials science. Germetall-1 isn't just a standard epoxy or adhesive. It's specifically engineered for orbital environments.

The development of specialized sealants for spacecraft reflects a broader reality: space has requirements that Earth-based applications don't. Standard sealants and adhesives often outgas in vacuum, releasing volatile compounds that can contaminate optical surfaces or degrade nearby electronics. They can become brittle in the extreme cold of shadow or too soft in direct sunlight.

Germetall-1 was formulated to solve these problems. It maintains its properties across the temperature range experienced on the ISS. It doesn't outgas significantly. It bonds effectively to metal and composite surfaces. It remains flexible enough to accommodate structural movement and thermal cycling.

The fact that Germetall-1 achieved patent protection indicates that its formulation and properties were genuinely novel. Patent offices don't grant patents for trivial modifications of existing products. This sealant represents real innovation in materials engineering.

The successful deployment of Germetall-1 for the Pr K leak repair demonstrates how space challenges drive innovation that eventually finds applications in other fields. Materials and techniques developed for orbital use have historically been adapted for use in aerospace, automotive, and industrial applications on Earth.

However, Germetall-1's success with the Pr K leak also highlights a limitation: the sealant addresses the symptom, not necessarily the underlying cause. The cracks still exist. They're simply sealed. This distinction matters because it means the vulnerability persists, even if it's currently contained.

Structural Aging on the ISS: A Broader Concern

The Pr K leak isn't an isolated problem specific to one module. It's a symptom of a broader reality: the International Space Station is aging. Components launched in the 1990s and early 2000s are now approaching or exceeding their original design lifespans.

The Zvezda module, source of the leak, was launched in 2000. Other critical modules are similarly aged. The station was originally designed for a ten-year operational life. Instead, it's been continuously occupied for more than two decades, with planning extending into the 2030s.

This longevity is a testament to engineering excellence and maintenance efforts. But it also means dealing with problems that designers never anticipated would occur. Materials degrade in ways that ground-based testing can't fully predict. Systems that were supposed to need replacement after ten years are still operating after twenty-five.

Space agencies have invested in upgrading components where possible. But not all hardware can be easily replaced. Some modules are too integral to station structure to be modified without major operations. Some systems were built with no replacement capability in mind.

The Pr K leak exemplifies this challenge perfectly. It's not an easy problem to solve because the leak source is elusive, the repair techniques are limited, and the underlying structural issue remains incompletely understood.

Managing an aging spacecraft requires different thinking than managing new hardware. Engineers must balance safety against operational capability, investment in repairs against investment in replacement, and long-term planning against near-term problem-solving.

The Geopolitical Dimension: Cooperation Despite Tension

The significance of solving the Pr K leak extends beyond engineering. It represents a successful collaboration between NASA and Roscosmos at a time when relations between the United States and Russia have been strained by geopolitical conflict.

The International Space Station is fundamentally a cooperative venture. The Russian segment provides critical capabilities, including propulsion, life support, and docking capability that the American segment depends on. Similarly, the American segment provides power generation, thermal management, and research capacity that benefits the entire facility.

When the Pr K leak became a serious problem in 2024, both agencies had incentive to solve it. A catastrophic failure or loss of critical functionality would affect both programs. Neither agency could afford to have a critical module become uninhabitable or nonfunctional.

The successful repair represents engineers on both sides working effectively together, sharing data, coordinating efforts, and achieving a common goal. This kind of cooperation isn't automatic. It requires professional relationships that survive political tensions, shared commitment to safety, and prioritization of technical excellence over geopolitical posturing.

That said, the cooperation has limits. Certain information sharing is restricted. Joint planning must account for different national interests. The ability to work together on the ISS doesn't extend to many other aspects of the space programs.

The leak repair is a reminder that space exploration can be a venue for cooperation, even amid broader tensions. It's also a reminder of how dependent the ISS is on this cooperation. If relations deteriorated to the point where Russia withdrew from the partnership, or vice versa, it would force a complete restructuring of how the station operates.

Baikonur Cosmodrome: Parallel Challenges and Recovery

Around the same time the Pr K leak was being addressed, another critical problem was affecting Russian space operations: damage to the primary launch facility at Baikonur.

In late November 2025, Roscosmos launched a Soyuz rocket carrying cosmonauts Sergei Kud-Sverchkov and Sergei Mikayev, along with NASA astronaut Christopher Williams, on an eight-month mission to the ISS. The launch itself was successful, but it exposed a serious issue.

Below the launch pad, a large mobile platform that provides structural support and flame deflection had not been properly secured before launch. The rocket's exhaust and the extreme vibrations of launch caused the platform to shift and crash into the flame trench below. The pad, designated Site 31 at Baikonur, was immediately taken offline.

This kind of damage to launch infrastructure can take months to repair. Site 31 is one of Russia's primary launch facilities for human missions and cargo resupply. Its loss impacts the entire cadence of ISS operations.

Initially, estimates for the pad's return to service were unclear. Recovery timelines could have extended into late 2026 or beyond, potentially creating gaps in ISS resupply and crew rotation schedules.

However, recent developments suggest recovery is progressing faster than initially feared. Based on NASA's updated internal schedules, the next Progress cargo vehicle is expected to launch on March 22, 2026, with a follow-up mission on April 26. The next crewed Soyuz mission, designated MS-29, is scheduled for July 14, 2026, carrying NASA astronaut Anil Menon.

These dates suggest that Baikonur repair efforts are on track for a March 2026 return to flight. If achieved, this would represent a compressed repair timeline, achieved through focused engineering efforts and the prioritization of returning critical launch capability.

The Baikonur situation illustrates how ISS operations are dependent on multiple vulnerable points. The station itself must remain operational. The Russian segment must function. Launch facilities must be available. Spacecraft must launch on schedule. Any disruption in any of these areas cascades through the entire system.

The Significance of Stabilizing a Critical Module

Why does the successful sealing of the Pr K leak matter so much? On the surface, it's a local repair to a small module. But the implications are broader and more consequential.

First, it removes a constraint on operations. As long as the leak was active and accelerating, it represented a ceiling on how long the Russian segment could operate without additional crew or maintenance. The leak was manageable with current resources, but if it had accelerated further, it might have required emergency measures.

Second, it demonstrates that the aging hardware of the station can still be repaired and maintained effectively. This is important psychologically for mission planners who need to have confidence that unexpected problems can be addressed through resourcefulness and hard work.

Third, it buys time. The station was originally planned to operate through the 2020s, with discussions about potential extensions into the 2030s. Solving critical problems like the Pr K leak makes those extended timelines more plausible. Each successful resolution of a major problem increases the probability that the station can continue operating productively.

Fourth, it validates the development of specialized repair techniques and materials. The successful application of Germetall-1 sealant in a space environment demonstrates that custom-engineered solutions can work for problems that standard approaches can't address.

Fifth, it highlights the value of sustained human presence in space. Humans can improvise, adapt, and develop creative solutions in ways that robotic systems sometimes can't. The cosmonauts' methodical approach to finding and sealing microscopic leaks is a reminder that human spaceflight capability, while expensive and complex, offers unique advantages.

The Role of Continuous Monitoring in Space Operations

Now that the leak has been sealed, both NASA and Roscosmos have committed to continuous monitoring. This isn't a temporary measure that will be discontinued once the problem seems solved.

Continuous monitoring of the Pr K module serves several purposes. It confirms that the seal remains effective. It detects any new leaks that might develop. It provides data about the module's long-term stability and helps engineers understand whether the underlying structural problem is static or might progress further.

This kind of ongoing monitoring is typical for critical infrastructure in space. Multiple sensors track pressures, temperatures, vibrations, and structural properties. Data is continuously transmitted to ground stations where engineers review it regularly.

If monitoring detected a recurrence of leakage, engineers would need to decide whether to repeat sealing operations or implement more comprehensive repairs. Options might include depressurizing the module completely to prevent sudden failures, restricting access to certain areas, or potentially scheduling more extensive repair or replacement operations.

The commitment to monitoring also reflects the uncertainty that persists about the underlying cause. As long as engineers don't fully understand why the cracks developed, they must remain vigilant for signs that the problem is recurring or worsening.

Future Risks and Hardware Degradation

The successful sealing of the Pr K leak doesn't eliminate the underlying hardware degradation that affects the aging ISS. Other modules, systems, and components continue to age. Some will fail. Others will require repairs. Some vulnerabilities might not become apparent until they cause problems.

Specific areas of concern include:

Thermal Management Systems: Radiators and coolant loops have been operating for 20+ years. They're showing signs of degradation. Micrometeorite impacts have damaged some panels. Fluid degradation is a concern.

Solar Arrays: The power-generating arrays were designed for ten-year lifespans. They've been operating for more than twice that period. Degradation of individual cells is expected and is being compensated for by replacing arrays, but aging hardware always carries risk.

Docking Mechanisms: These are subject to wear from repeated use. Hundreds of spacecraft have docked and undocked over the station's lifetime. Mechanisms that operate perfectly thousands of times may eventually fail.

Hatch Seals: Throughout the station, hatches maintain pressure boundaries between modules. Seals degrade with use and with exposure to thermal cycling. Each hatch seal failure creates the potential for atmospheric loss.

External Systems: Anything exposed to the vacuum environment experiences accelerated aging. Material degradation from ultraviolet exposure, atomic oxygen bombardment, and thermal cycling creates cumulative damage.

Managing these risks requires sustained investment in inspection, maintenance, and planned replacements. It also requires accepting that unexpected problems will arise and maintaining the capacity to respond to them.

The Pr K leak is significant not because it's unique, but because it represents the kind of problem that space agencies will continue facing as the station ages. Success in addressing one problem increases confidence in the ability to address others.

The Human Element: Why Cosmonauts Were Essential

It's worth noting explicitly that the successful repair of the Pr K leak depended on human cosmonauts. Robotic systems alone couldn't have solved this problem.

While robots excel at performing precisely defined tasks in controlled environments, they struggle with troubleshooting, adaptation, and problem-solving in unfamiliar situations. Finding a microscopic leak in a complex module and applying a specialized sealant required the judgment, creativity, and adaptability that humans bring to technical challenges.

Cosmonauts could:

- Make judgment calls about where to look for leaks based on experience and intuition

- Adapt inspection techniques based on what they discovered

- Work with specialized tools and materials that weren't pre-programmed into any robot

- Communicate observations to ground teams who helped guide additional investigation

- Make real-time decisions about repair strategies based on what they found

- Troubleshoot when initial approaches didn't work

A robotic system designed to find and seal leaks would need to be incredibly sophisticated, with advanced sensing, multiple contingency algorithms, and the ability to handle unexpected configurations. Such a system would be extraordinarily expensive and complex.

Instead, NASA and Roscosmos relied on trained humans with extensive experience in spacecraft operations. This reliance on human capability is one of the strongest arguments for maintaining human presence on the ISS rather than transitioning to exclusively robotic operations.

The Broader Context: ISS at a Crossroads

The successful resolution of the Pr K leak occurs at a significant moment for the ISS. The station is at a crossroads where decisions about its future will shape space exploration for decades.

Originally planned as a ten-year facility, the ISS has already exceeded that lifespan more than twofold. Each year that it continues operating represents a choice to invest in maintenance and repair rather than investing in replacement infrastructure.

Some argue that continued investment in the aging ISS detracts from development of next-generation orbital facilities. Others contend that the station remains productive and irreplaceable for certain kinds of research and technology development.

The lease agreement for the Russian segment extends into the late 2020s, though there's been discussion about possible extension. The American segment's operational plans extend into the 2030s in some scenarios, though the final timeline hasn't been determined.

Problems like the Pr K leak are part of this decision-making context. Each time a significant problem is successfully resolved, it strengthens the argument for continued investment. Each time a problem emerges that can't be easily addressed, it creates pressure to consider alternatives.

The successful repair demonstrates that the station can continue operating effectively with proper maintenance and investment. It also demonstrates that the station requires increasingly intensive maintenance and that unexpected problems will continue to emerge.

Planning for the Next Generation

While the ISS remains operational, planning is underway for next-generation orbital infrastructure. Commercial space stations are being developed by companies including Axiom Space, with support from NASA. These facilities will eventually replace or supplement the ISS.

The experience with the ISS, including challenges like the Pr K leak, informs the design of next-generation facilities. Engineers know that hardware will age, that unexpected problems will emerge, and that maintenance will be necessary. Design decisions reflect these lessons.

Next-generation commercial stations will likely incorporate:

- More accessible components designed for easier maintenance and replacement

- More extensive redundancy in critical systems

- Materials and coatings selected for improved long-term durability

- Design features that anticipate the kinds of problems the ISS has experienced

- More comprehensive monitoring systems that detect problems earlier

- Modular designs that allow individual sections to be replaced rather than repaired

The lessons from the ISS's 25+ years of operation will directly influence how future facilities are designed, built, and maintained.

International Cooperation in Space: The ISS Model

The Pr K leak resolution also highlights the model of international cooperation that the ISS represents. Multiple nations collaborating on a shared facility, sharing costs, coordinating operations, and working together to solve problems.

This cooperation model isn't universal in space. Some space programs pursue national goals with limited international collaboration. But the ISS demonstrates that complex, ambitious projects can be undertaken through cooperative partnerships.

The stability and success of ISS operations depend on this cooperation continuing, even through periods of geopolitical tension. The fact that the Pr K leak was successfully addressed demonstrates that this cooperation, while sometimes strained, remains functional.

However, the future of this cooperation is uncertain. Changes in political relationships, shifts in national priorities, or disagreements about ISS management could potentially disrupt the partnership. The success in resolving the Pr K leak shouldn't be taken as guarantee that cooperation will continue indefinitely.

Conclusion: A Victory Against Orbital Entropy

The successful sealing of the Pr K leak represents a genuine technical achievement. It's not a dramatic, headline-grabbing accomplishment like a Mars landing or a first in space. Instead, it's the kind of problem-solving that keeps complex systems functioning year after year.

For six years, engineers and cosmonauts worked methodically to locate, understand, and address a problem that was almost impossible to see. They developed inspection techniques, created custom sealant materials, and executed repairs in an environment where mistakes can't be easily corrected.

The leak has stopped. The atmospheric pressure is holding steady. The Pr K module remains operational and fully integrated into the station's systems.

But this success comes with caveats. The underlying structural cracks that caused the leak still exist. They're sealed, not removed. New cracks could develop. The Zvezda module continues to age. Other problems will inevitably emerge.

The Pr K leak is ultimately a story about persistence, resourcefulness, and the value of human expertise applied to technical challenges. It's also a story about the realities of operating complex systems far from Earth, where problems must be solved with limited resources and limited ability to replace damaged components.

As the International Space Station continues its slow aging in orbit, similar challenges will arise. Each one represents an opportunity to apply lessons learned, develop new capabilities, and demonstrate that aging infrastructure can continue operating effectively with proper attention and investment.

The successful resolution of the Pr K leak doesn't mean the ISS has been "fixed." Rather, it demonstrates that the station can be maintained in operational condition through sustained effort and technical innovation. How long that remains true depends on continued investment, continued international cooperation, and continued commitment to solving the problems that inevitably emerge when humans maintain a complex facility in the harsh environment of low Earth orbit.

For now, the station is stable. Pressure is holding. Cosmonauts and astronauts continue their work. The victory against this particular leak is complete. But the broader challenge of maintaining an aging orbital facility continues, one technical problem at a time.

FAQ

What is the Pr K module on the International Space Station?

The Pr K is a small transfer corridor module on the Russian segment of the ISS that connects the Zvezda Service Module to airlock systems. It's strategically important for allowing cosmonauts and astronauts to move between modules and for maintaining the physical connections that integrate the Russian segment with the rest of the station. Its small size made it particularly vulnerable to pressure loss from microscopic structural cracks.

How did cosmonauts detect and locate the microscopic leak?

Cosmonauts used a methodical approach involving module isolation and dust detection. They would seal the Pr K module from the rest of the station, wait for pressure to indicate leakage, then reopen the hatch and carefully examine the interior for dust accumulations or oxidation patterns that would indicate where air was escaping. This process, repeated multiple times over years, eventually identified leak locations.

Why did the Zvezda module develop structural cracks after 25 years of operation?

Engineers still don't fully understand the root cause of the cracking. Likely contributing factors include extreme thermal cycling (16 day-night cycles per Earth day causing temperature swings from -120°C to +120°C), material degradation from solar radiation and atomic oxygen exposure, and the accumulated stresses of orbital operations exceeding the module's original ten-year design life. Manufacturing defects or unforeseen stresses from how the module is actually used in orbit may also have played roles.

What is Germetall-1 and why was it effective for sealing the leak?

Germetall-1 is a specially developed, patented epoxy-based sealant engineered specifically for orbital environments. Unlike standard sealants, it doesn't outgas in vacuum, maintains its properties across extreme temperature ranges, and remains effective in the harsh space environment. Repeated applications of this sealant to microscopic cracks eventually achieved a vacuum-tight seal that stopped atmospheric loss.

How did the leak rate acceleration in 2024 change the situation?

When the atmospheric loss rate doubled in 2024, NASA reassessed the risk from manageable to "high likelihood, high consequence," indicating the problem could potentially compromise critical station operations. This escalation prompted more intensive inspection and repair efforts. The acceleration suggested the underlying structural problem was worsening, not stabilizing, making urgent action necessary.

What happened to the Baikonur Cosmodrome launch pad, and how does it affect ISS operations?

During a Soyuz launch in November 2025, a mobile platform below the pad wasn't properly secured and crashed into the flame trench, damaging the launch facility. Site 31 at Baikonur is one of Russia's primary launch pads for ISS crew rotation and cargo resupply. Repair efforts are progressing on schedule for a March 2026 return to flight, according to updated NASA schedules showing Progress launches in March and April 2026 and a crewed Soyuz mission in July 2026.

Why is continuous monitoring of the Pr K module necessary even after the leak stopped?

Continuous monitoring confirms that the seal remains effective, detects any recurrence of leakage, and provides data about the module's long-term structural stability. Since the underlying cause of the original cracking remains incompletely understood, engineers must remain vigilant to catch any signs that the problem is recurring or that new structural issues are developing in other parts of the aging module.

How does the ISS leak repair demonstrate why human presence in space remains important?

The successful repair required creative problem-solving, judgment calls about where to search for leaks, adaptation of techniques based on discoveries, and real-time decision-making about repair strategies. These cognitive tasks are difficult to fully automate. While robots excel at precisely defined tasks, they struggle with the troubleshooting and adaptation that this repair demanded, making trained cosmonauts invaluable for maintaining complex orbital infrastructure.

What does the Pr K leak resolution mean for the International Space Station's operational future?

The successful repair strengthens the argument for continued ISS investment and extended operational timelines, demonstrating that the station can be maintained in operational condition despite aging hardware. However, it also demonstrates that the station requires increasingly intensive maintenance and that unexpected structural problems will continue to emerge. The repair validates continued investment in ISS operations while highlighting the ongoing challenges of maintaining aging infrastructure in space.

How will the experience with ISS aging problems influence the design of next-generation space stations?

Next-generation commercial space stations will incorporate design lessons from the ISS, including more accessible components for easier maintenance, greater redundancy in critical systems, more durable materials, modular designs allowing component replacement rather than repair, and more comprehensive monitoring systems. The challenges faced by the ISS, including problems like the Pr K leak, directly inform how future orbital facilities will be designed to remain operational and maintainable for decades.

Key Takeaways

- Russia's PrK module atmospheric leak stopped after six years of intensive repairs and the leak rate had doubled in 2024, triggering NASA's high-consequence risk designation

- Cosmonauts used dust detection methodology and visual inspection combined with specialized Germetall-1 sealant to locate and seal microscopic structural cracks that design engineers still don't fully understand

- The Zvezda module, launched in 2000, demonstrates how orbital hardware exceeds design lifespans by 2.5 times, creating ongoing degradation challenges that require continuous maintenance

- Baikonur Cosmodrome's launch pad repairs are on track for March 2026 return to flight, supporting ISS resupply and crew rotation schedules dependent on uninterrupted launch capability

- Human cosmonauts proved essential for solving the leak problem through troubleshooting and adaptation, capabilities that are difficult to automate completely in space environments

Related Articles

- Tesla Loses EV Crown to BYD: Market Shift Explained [2025]

- NYT Strands Game #671 (January 3): Hints, Answers & Strategy Guide

- Best Movies & TV Shows Streaming This Weekend [January 2025]

- Quordle Hints, Answers & Strategy Guide [2025]

- NYT Connections Hints & Strategy Guide [2025]

- Pebble Round 2: The Smartwatch Comeback That Fixes Everything [2025]

![International Space Station Russian Segment: Leak Mystery Solved [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/international-space-station-russian-segment-leak-mystery-sol/image-1-1767370336523.jpg)