Introduction: When Legends Reimagine Computing Fundamentals

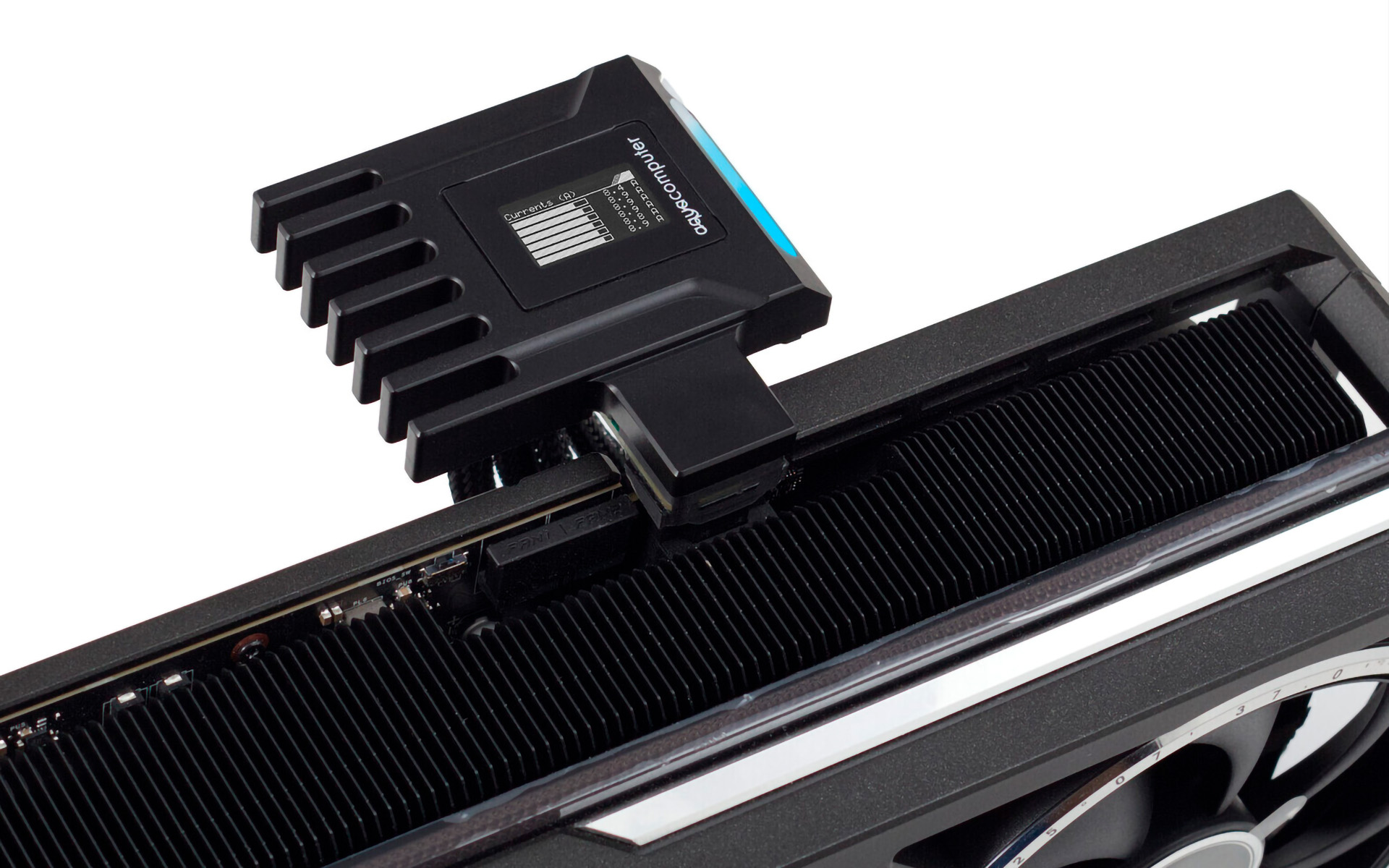

John Carmack has spent his career breaking assumptions. The legendary programmer who co-founded id Software and created the Quake engine has always been the kind of thinker who asks "Why do we do it this way?" instead of accepting industry conventions.

So when Carmack recently proposed replacing RAM entirely with fiber optic cables—thousands of kilometers of them looped in massive circles—nobody paid attention at first. It sounds absurd. It sounds impractical. It sounds like science fiction.

But here's the thing: it might actually work.

The core concept is deceptively simple. Instead of storing data in traditional RAM chips sitting next to your processor, data travels through fiber optic cables at nearly the speed of light. A 200-kilometer loop of fiber could serve as memory, with data circulating continuously until it's needed. You're not replacing the speed of RAM, but you're potentially replacing its capacity at a fraction of the cost and power consumption.

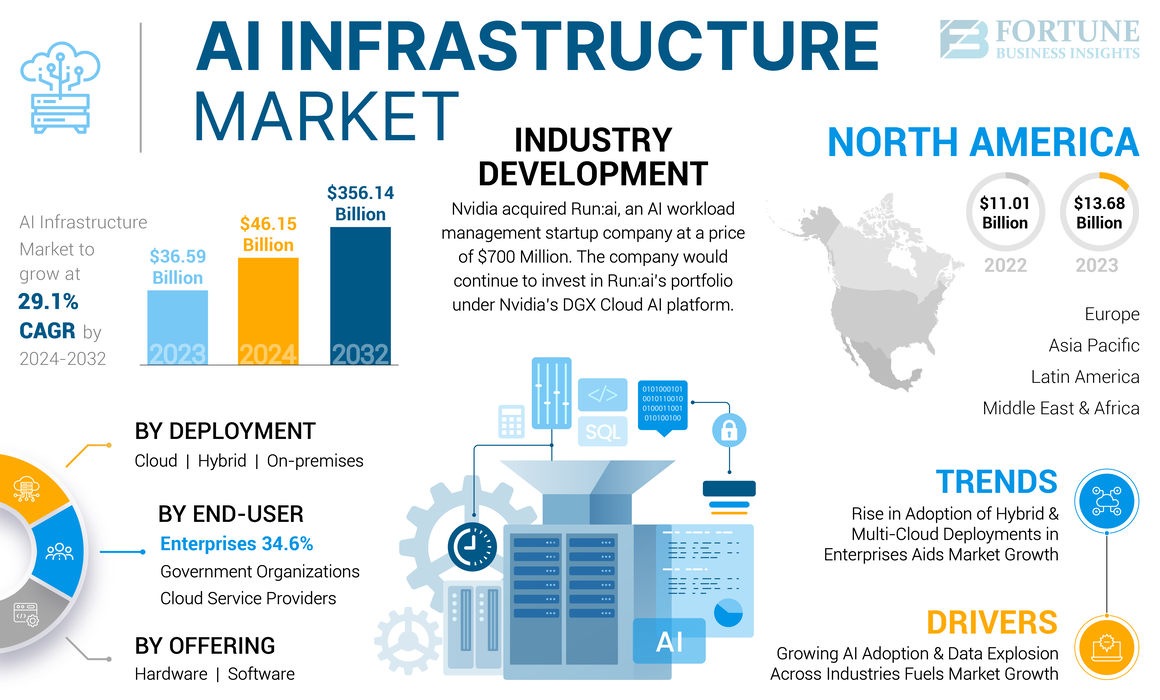

This isn't just theoretical rambling. The AI industry is facing a genuine memory crisis. Training models like GPT-4 or Claude requires insane amounts of memory. We're talking about systems that need terabytes of accessible working memory to function efficiently. Current RAM technology is hitting physical and economic limits. A single GPU with 80GB of HBM3 memory can cost over $10,000, and even then, it's not enough for the largest models in development.

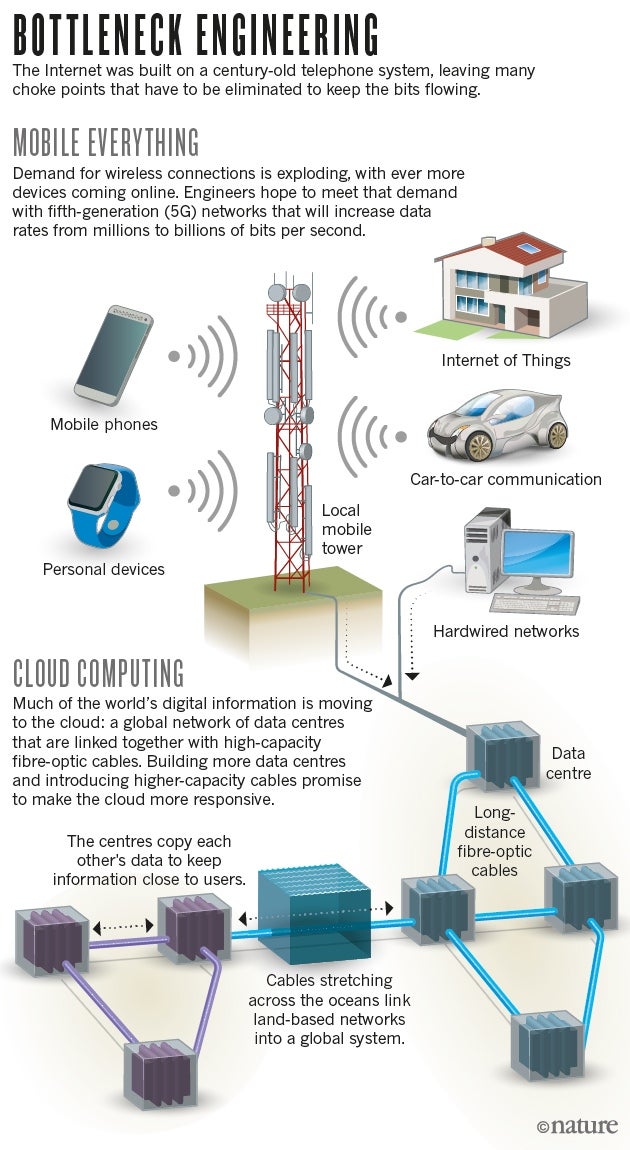

The memory bandwidth problem is equally critical. Moving data between storage and computation is often slower than the actual computation itself. This bottleneck means that even with powerful GPUs, data centers spend enormous amounts of time waiting for information to arrive. It's like having a super-fast chef but ingredients that arrive at a glacial pace.

Carmack's proposal addresses both problems simultaneously: massive capacity through kilometers of fiber, and perpetual availability because data is always in motion, ready when needed. The implications ripple across data centers, AI training infrastructure, and every company trying to build the next generation of large language models.

This isn't about replacing RAM for gaming laptops or office PCs. This is about fundamentally redesigning how we architect computing systems at scale. And if Carmack is right, the companies that figure this out first will have an enormous competitive advantage in the AI arms race.

Let's dig into how this actually works, why it matters, and whether it's really the future or just another theoretical concept destined to remain on whiteboards.

TL; DR

- The Fiber Memory Concept: John Carmack proposes using hundreds of kilometers of looped fiber optic cables as a replacement for traditional RAM in AI systems, with data circulating at light speed

- The Memory Crisis: AI model training demands terabytes of working memory, and current RAM technology costs exceed $10,000 per GPU while hitting capacity and power consumption limits

- Bandwidth Revolution: The approach solves both capacity and latency problems by keeping data in constant motion, eliminating expensive data transfers between storage and computation

- Why This Matters: If viable, this could slash AI infrastructure costs by 50-70% and enable training of models three times larger with existing hardware

- Implementation Timeline: Not viable at scale until quantum-speed routing and sub-microsecond switching are solved, likely 5-10 years away for production systems

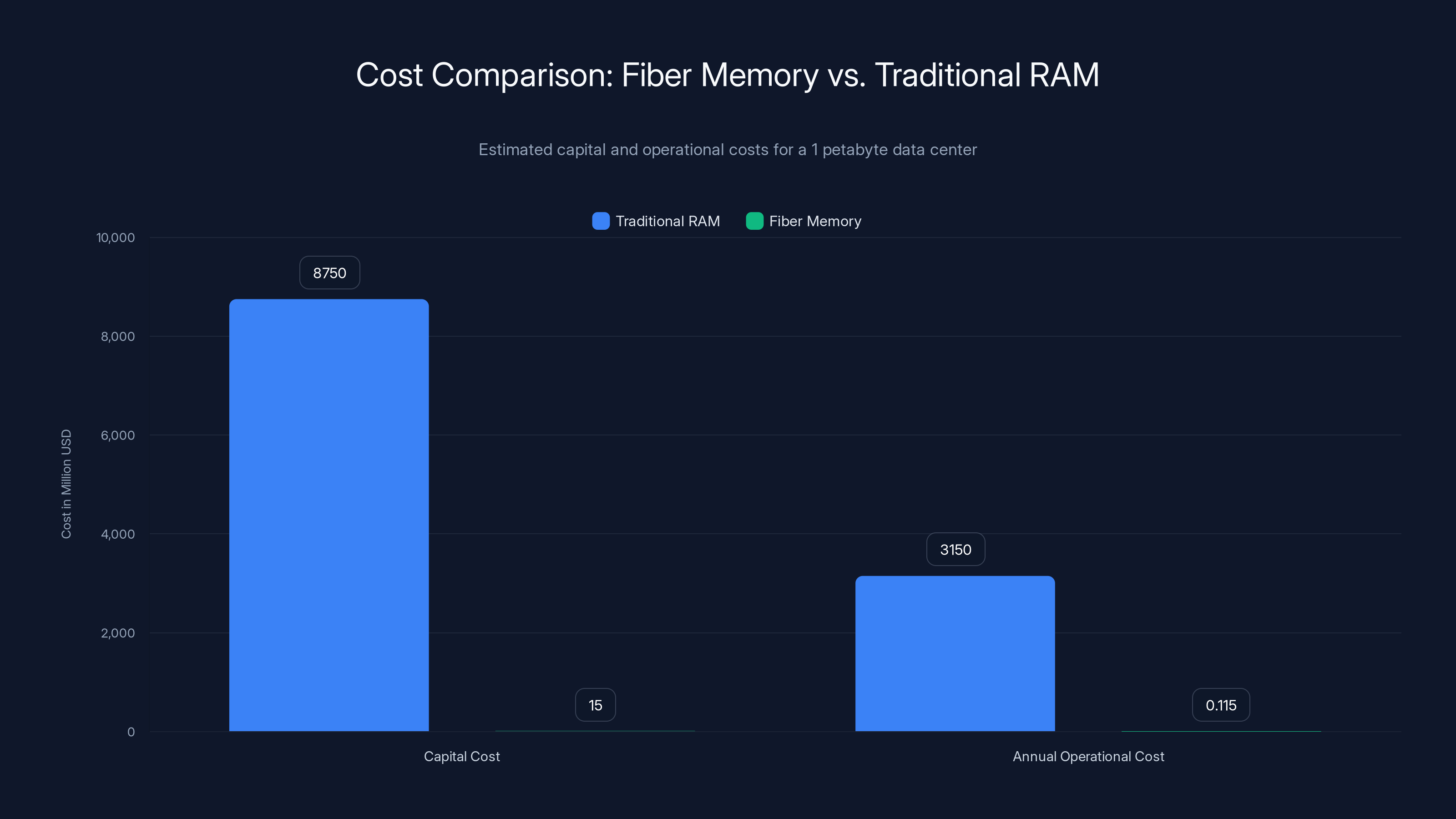

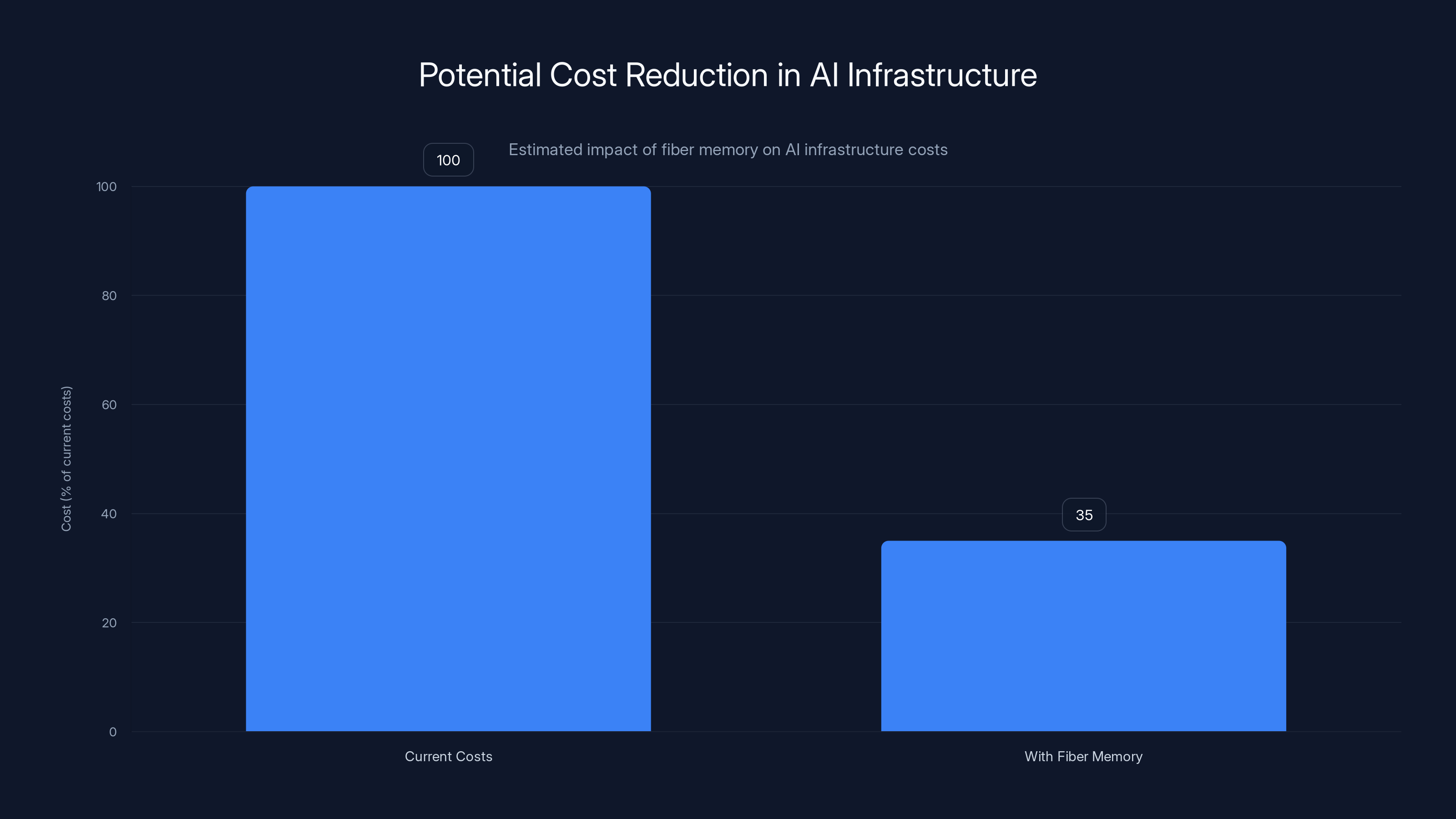

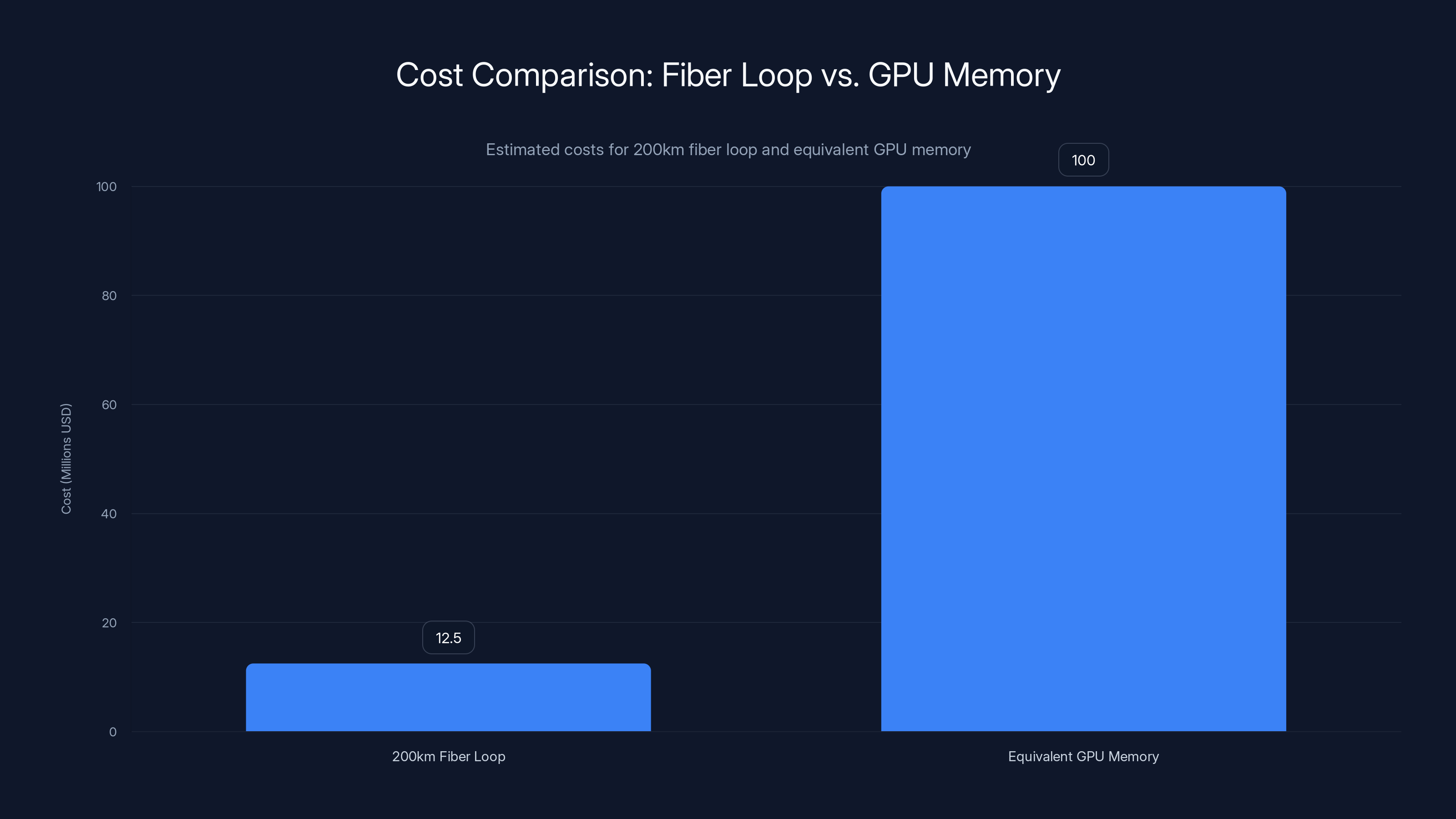

Fiber memory systems are significantly cheaper in both capital and operational costs compared to traditional RAM, with potential savings of $3.14 million annually in operational expenses alone (Estimated data).

The Memory Crisis in Modern AI: Why RAM Isn't Keeping Up

The Scale of Modern AI Memory Requirements

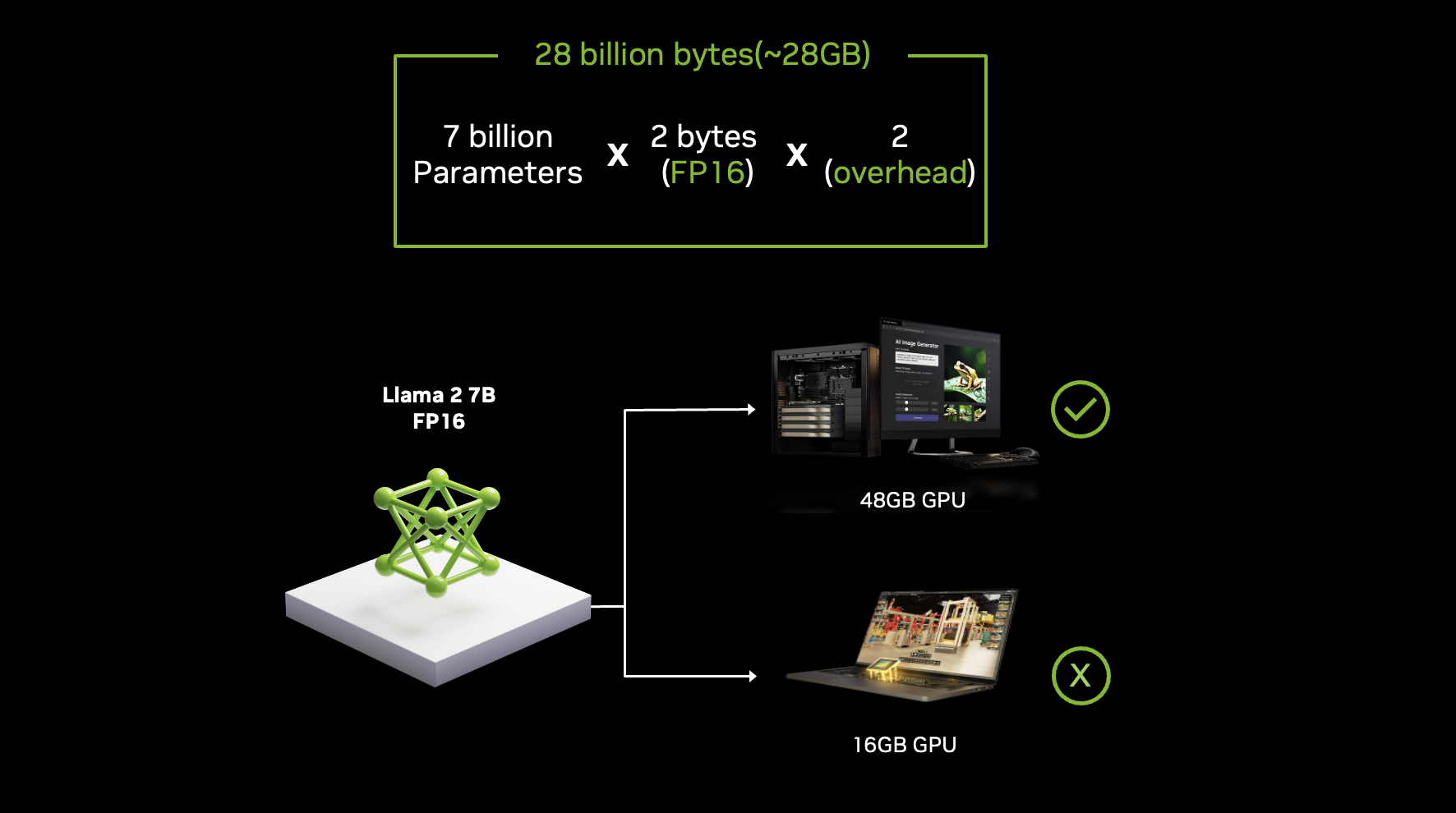

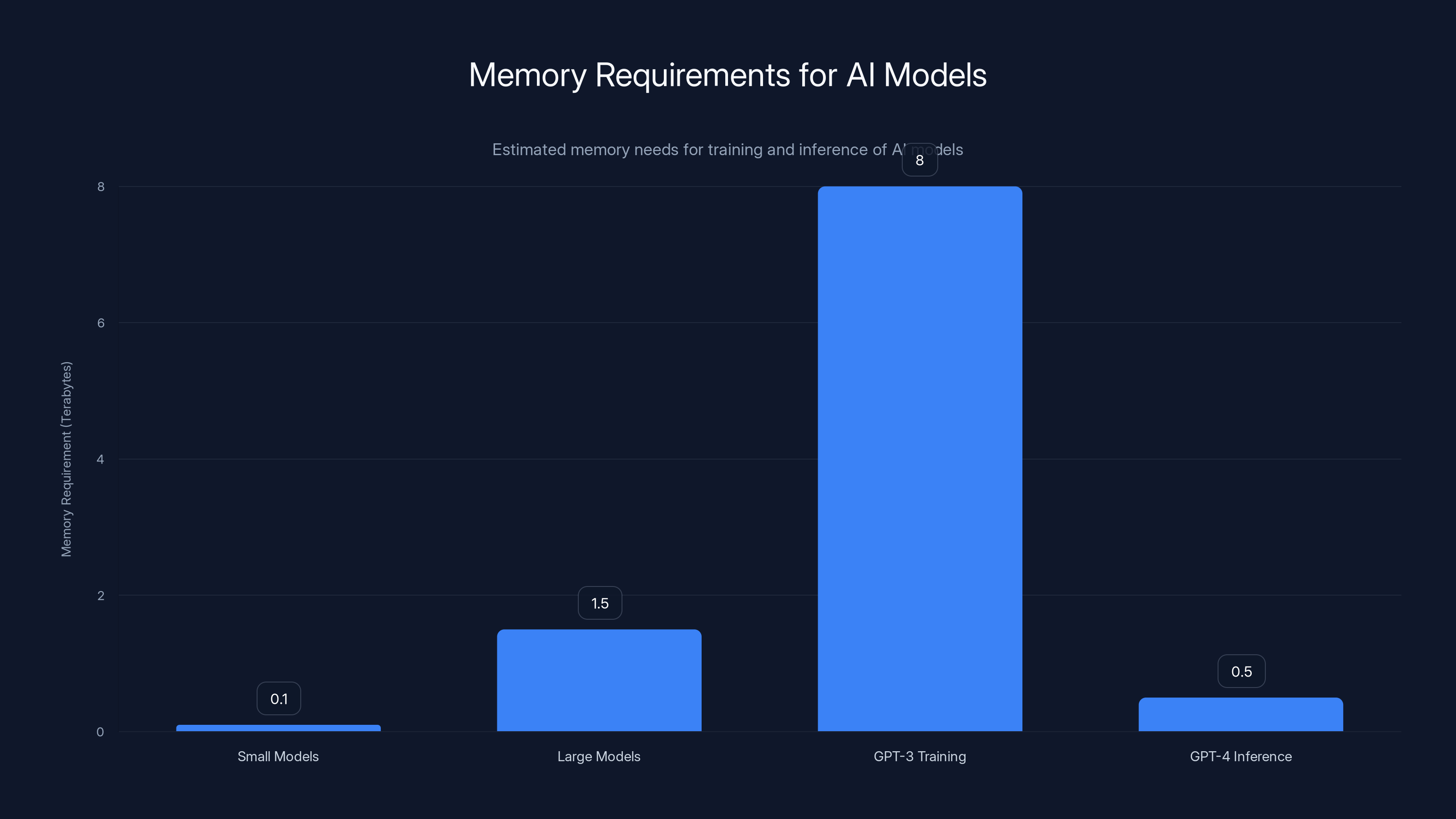

Let's get concrete about what we're dealing with. When Open AI trained GPT-3 with 175 billion parameters, they needed to keep massive amounts of model state, optimizer state, and gradient information in memory simultaneously. We're not talking about gigabytes. We're talking about hundreds of gigabytes for small models, terabytes for the largest ones.

A single instance of training a modern large language model requires somewhere between 1.5 to 8 terabytes of immediately accessible, high-speed memory depending on batch size, model size, and training methodology. That's not theoretical. Companies like Meta and Google are building data centers specifically designed around these constraints.

The problem gets worse when you consider inference. Serving Chat GPT to millions of simultaneous users requires keeping multiple copies of the model in memory across distributed systems. Each copy needs to be instantly accessible. The memory footprint of a single GPT-4 instance is somewhere in the gigabytes per model, and when you're running thousands of inference servers, this adds up catastrophically.

The Cost-to-Capacity Problem

Right now, the only way to get massive amounts of fast memory is to buy High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) chips. These are expensive. A single NVIDIA H100 GPU with 80GB of HBM3 costs around

When you build a data center with thousands of these GPUs, memory cost becomes one of the largest capital expenditures. A 100-GPU cluster needs 8 terabytes of HBM memory. At current prices, you're spending

For companies training the largest AI models, memory costs represent 30-40% of total infrastructure spending. Every dollar spent on memory is a dollar not spent on additional compute capacity or other infrastructure improvements.

The Bandwidth Bottleneck

There's another problem that many people don't immediately recognize: bandwidth saturation. Moving data from storage to memory to GPU and back again is incredibly expensive in terms of both time and energy.

Consider this formula for theoretical memory bandwidth:

Where:

- = bandwidth in bytes per second

- = frequency in Hz

- = bus width in bytes

Modern GPU memory can achieve around 3.9 terabytes per second of bandwidth between GPU and its local memory. That sounds insane until you realize the actual computation happening on modern GPUs can theoretically exceed 1.4 petaflops (quadrillions of operations per second). The ratio between computation and memory bandwidth is staggeringly imbalanced.

This means that in many AI workloads, the GPU is sitting idle, waiting for data to arrive from memory. It's like having a factory with machines that can produce 1,000 units per hour but a supply chain that can only deliver materials for 100 units per hour. No matter how fast your machines are, you're bottlenecked by incoming material.

The Power Consumption Nightmare

Moving data is expensive in terms of power. Transferring one byte of data from far away in a data center to a GPU requires roughly 100 times more energy than performing a simple arithmetic operation on data already in the GPU's memory.

When you're training AI models 24/7 in massive data centers, this power cost becomes astronomical. A single large-scale training run can consume megawatt-hours of electricity. Somewhere between 20-30% of that energy goes to moving data around, not actually computing anything useful.

This creates a vicious cycle: you need more memory to fit the model, which means more data movement, which means more power consumption, which means more cooling requirements, which means more power consumption. Data centers training AI models are becoming some of the biggest power consumers on the planet.

Understanding Carmack's Fiber Optic Memory Concept

How Data Would Circulate in a Fiber Loop

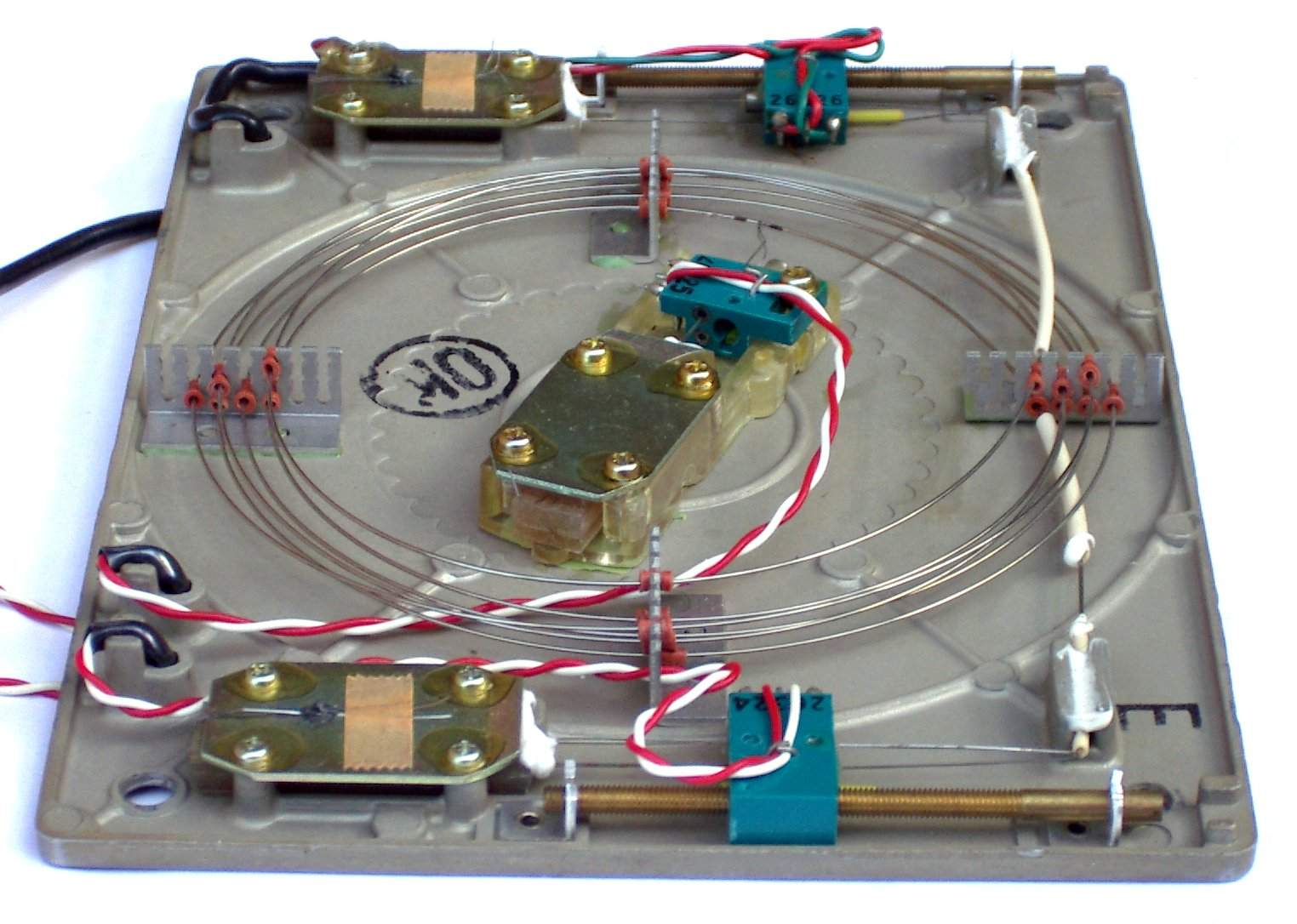

Here's the elegant simplicity of Carmack's idea: instead of storing data statically in RAM chips, you store it in motion within fiber optic cables.

Imagine a loop of fiber optic cable that's 200 kilometers long. Data enters the loop as optical signals. These signals travel around the loop at the speed of light—approximately 200,000 kilometers per second through fiber (which is about 67% the speed of light in vacuum).

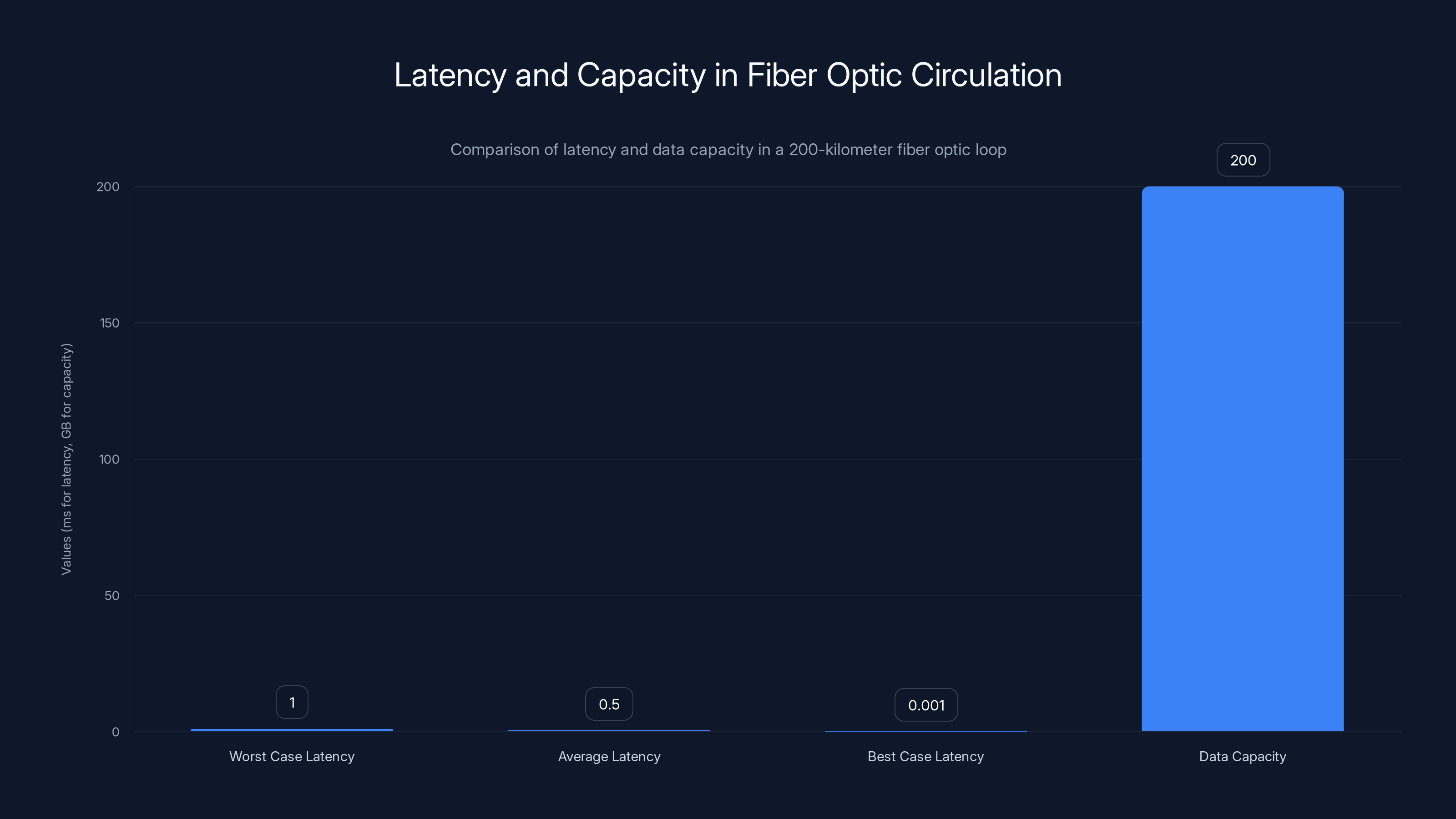

At any given time, you have roughly 1 millisecond of latency waiting for your data to come around the loop again if it's at the opposite side. But here's the brilliant part: you don't necessarily care. The latency is fixed and predictable. More importantly, you can have millions of gigabytes of data circulating through the loop simultaneously.

Data never sits idle. It's constantly moving, constantly available, and the entire capacity of the loop is usable working memory. A 200-kilometer loop at light speed contains the equivalent of perhaps 1-2 terabytes of actively circulating data at any given moment.

The Optical Switching Problem

The tricky part isn't moving data around a fiber loop. That's essentially solved. The problem is: how do you get data out of the loop when you need it, and how do you put new data in?

This requires optical switches that can redirect signals with nanosecond to microsecond latency. You need to be able to inject data into the loop and extract data from the loop without disrupting the data already circulating.

Modern optical switches exist, but they're slow by the standards Carmack's concept requires. Current commercial optical switches have switching latencies in the milliseconds. You'd need to improve this by 1,000 to 10,000 times to make the system practical.

But here's the thing: optical component manufacturers have been steadily improving switching speeds. Each generation of optical switches gets faster. The technology might not exist today at the required speed, but it's not physically impossible.

Why Fiber Instead of Copper?

Fiber optic cables transmit data as pulses of light, while copper cables transmit electrical signals. Why does Carmack prefer fiber for this application?

Signal degradation: Copper signals degrade over distance. After a kilometer or so, you need expensive repeaters to boost the signal. Fiber signals can travel tens of kilometers before needing amplification, and when you do amplify, it's simpler and cheaper.

Bandwidth: Fiber can carry significantly more data simultaneously than copper. Multiple wavelengths of light can travel through a single fiber at the same time, a technique called wavelength division multiplexing (WDM). A single fiber can carry hundreds of terabits per second with modern equipment.

Power efficiency: Moving optical signals requires less power than moving electrical signals, especially over long distances.

Cost at scale: When you're talking about 200 kilometers of cable, the economic difference becomes massive. Fiber cables are surprisingly cheap compared to equivalent copper infrastructure.

Estimated data shows that training large AI models like GPT-3 can require up to 8 terabytes of memory, while inference for models like GPT-4 requires significant memory as well. Estimated data.

The Physics Behind Light-Speed Memory Circulation

Understanding Light Propagation in Fiber

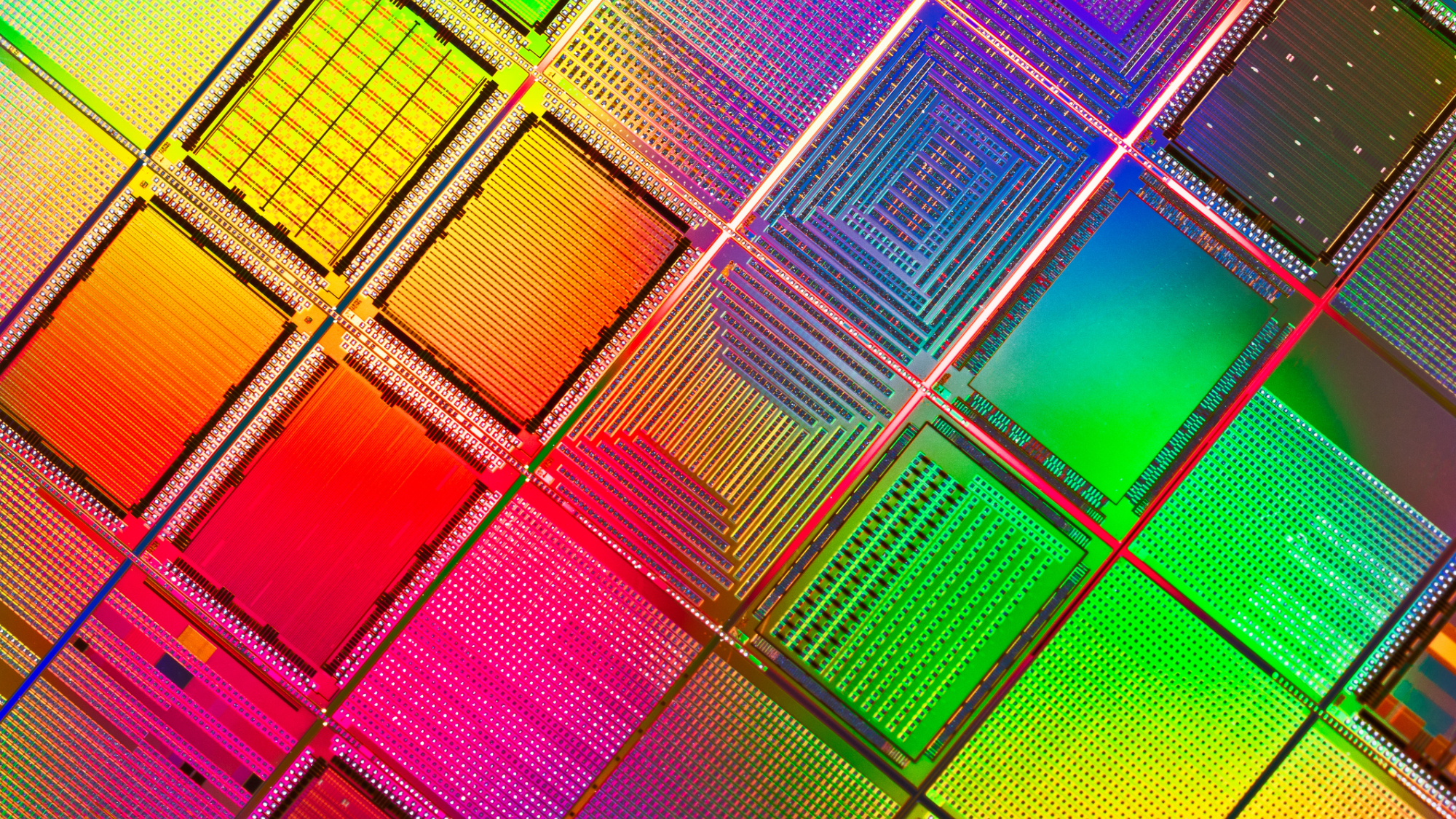

When we say data travels at "light speed" through fiber, we need to be precise about what that actually means. Light in a vacuum travels at approximately 299,792 kilometers per second. In fiber optic cables, light travels at about 200,000 kilometers per second (roughly 67% of the speed of light in vacuum), because the refractive index of glass is approximately 1.5.

This creates a predictable latency formula:

Where:

- = latency in seconds

- = distance in meters (cable length)

- = refractive index of fiber (approximately 1.5)

- = speed of light in vacuum (299,792 km/s)

For a 200-kilometer loop:

So your absolute worst-case latency for accessing data that just passed your access point is 1 millisecond. Your best case (data arrives immediately) is microseconds. Your average case is around 0.5 milliseconds.

This latency is actually acceptable for many AI workloads. Modern GPUs can issue new work instructions while waiting for data from memory. The key is that this latency is predictable and consistent, unlike traditional storage where latency varies wildly based on access patterns and system load.

Capacity Calculations

How much data can actually circulate in this loop? That depends on the data transmission rate and the time it takes to complete one full circulation.

If you're transmitting data at 1.6 terabits per second (a realistic number for modern fiber infrastructure), and the data takes 1 millisecond to complete one loop:

With multiple wavelengths (which modern systems support), you could achieve multiple terabytes of circulating capacity. If you use wavelength division multiplexing with 80 different wavelengths, you're looking at potentially 16 terabytes of high-speed, accessible working memory in a single fiber loop.

The Optical Amplification Challenge

Over 200 kilometers, even in fiber, optical signals degrade. You need optical amplifiers—devices that boost the signal strength without converting it back to electrical form.

Modern erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs) can amplify signals over hundreds of kilometers and are remarkably efficient. However, they introduce noise into the signal. The longer the distance and the more amplifications required, the more noise accumulates, eventually corrupting the data.

For a fiber memory system, you'd need incredibly low-noise amplification—probably pushing the limits of current technology. You might need amplifiers every 30-40 kilometers and they'd need to be significantly better than current commercial amplifiers.

This is solvable through engineering but not trivial.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Economics of Fiber Memory vs. Traditional RAM

Capital Expenditure Comparison

Let's build a financial model. Compare two approaches: traditional GPU memory and Carmack's fiber memory system, both for a 1 petabyte data center.

Traditional Approach with HBM Memory:

- 1 petabyte = 1,000 terabytes

- Current HBM3 cost approximately $125 per gigabyte at volume

- Total memory cost: $125 billion (obviously impossible, but this shows the scale of the problem)

- In practice, nobody buys 1PB of HBM. Instead, data centers use tiered storage with hotly accessed data in fast memory

- Realistically, maybe 5% of data is in HBM at any time = 50TB = $6.25 billion

- Plus infrastructure, cooling, power delivery: add another 40% = $8.75 billion

Fiber Memory Approach:

- 200km of fiber cable: approximately 200,000

- Optical switching equipment: $5-10 million

- Amplifiers and monitoring: $2-3 million

- Total initial infrastructure: roughly $10-15 million

The fiber approach is 500-1000x cheaper in terms of raw capital expenditure. But wait, there's a catch: the fiber system is slower to access and has different performance characteristics.

Operational Cost Implications

Once infrastructure is in place, the operational differences matter:

HBM Memory System:

- Power consumption for memory: approximately 250-300 watts per GPU (memory accounts for ~30% of GPU power)

- 10,000 GPUs consuming 3 megawatts just for memory operations

- Over a year: 26,280 megawatt-hours

- At 3.15 million annually

Fiber Memory System:

- Optical amplifiers consume approximately 1-2 watts per amplifier

- 200km loop needs roughly 5-6 amplifiers: ~10 watts

- Optical switches and routing: ~100 watts

- Total power: approximately 110 watts vs. 3 megawatts

- Annual cost: roughly $115

- Savings: $3.14 million per year

If the fiber system remains operational for 10 years, the operational cost savings alone exceed $30 million, plus the massive capital expense reduction.

When the Economics Work

Fiber memory makes economic sense for:

- Very large data centers (100+ petabytes of data) where capital costs are astronomical

- Long-running AI training jobs where the system operates 24/7 for weeks or months

- Continuous inference systems where data is accessed repeatedly in predictable patterns

- Energy-constrained environments where power consumption is a limiting factor

It probably doesn't make economic sense for:

- Consumer devices or small servers where 200km of fiber is impractical

- Latency-critical applications where microsecond differences matter

- Random access patterns where you can't predict what data you'll need

Technical Barriers and Unsolved Problems

The Optical Switching Latency Problem

The biggest unsolved challenge is the speed of optical switches. Current commercial optical switches have switching latencies in the 10-100 millisecond range. Carmack's concept requires switches with nanosecond to low-microsecond switching times.

Why is this a problem? If you have data circulating in a loop and you want to extract it, you send a signal to an optical switch saying "extract this data now." The switch needs to respond in time to catch the right data pulse as it comes around. Miss the window by even a microsecond and the data zips past and you have to wait another millisecond for it to come around again.

Modern research in photonic switching shows promise. Silicon photonics companies are developing switching architectures that could achieve microsecond-level latencies. But this is still largely in the research phase, not yet at commercial scale.

Signal Integrity and Bit Error Rates

When you have data traveling hundreds of kilometers through fiber and bouncing off optical switches, you introduce opportunities for signal degradation. Bit errors become a real problem.

Modern fiber systems achieve bit error rates around 1 error in 10^15 bits transmitted. For a system transmitting terabits per second, this translates to roughly one error every few seconds.

For traditional data transmission, this is acceptable because you can use error correction codes. For memory, it's more problematic. If your memory system is returning corrupted data with any regularity, your applications crash, and your training runs fail.

You'd need error correction codes (like Reed-Solomon codes) baked into the fiber memory system, which adds complexity and overhead. Perhaps 5-10% of your bandwidth gets consumed by error correction rather than actual data.

The Cooling Problem

One aspect people overlook: fiber amplifiers generate heat. A 200-kilometer loop with amplifiers every 30 kilometers generates scattered heat along the entire length. You can't cool this the same way you cool a data center server rack.

You'd need distributed cooling along the fiber path. In a data center, you might have the fiber looped around the facility and then through a cooling system. This adds infrastructure complexity.

Alternatively, you design the amplifiers for ultra-low power consumption, which is technically challenging.

The Routing and Switching Architecture Problem

With a simple single loop, you can only store one "stream" of data. In practice, you'd need multiple loops, multiple switch points, and complex routing logic.

Imagine you have:

- 10 different fiber loops

- 100 different computation nodes that need to access data

- Random access patterns from various AI training jobs running simultaneously

Now you need a routing architecture to direct data from the right fiber loop to the right compute node, and you need a scheduling system to optimize memory access patterns. This is essentially building a new memory controller architecture from scratch.

Traditional DRAM has sophisticated controllers that handle caching, prefetching, and access optimization. You'd need an optical equivalent, and it would need to operate at optical speeds (nanoseconds), not traditional electronic speeds (microseconds).

Implementing fiber memory could potentially reduce AI infrastructure costs by 50-70%, making it a transformative technology for AI model training. (Estimated data)

How AI Training Would Adapt to Fiber Memory Architecture

Rethinking Data Access Patterns

Traditional AI training assumes fast, random access to memory. You're constantly jumping around to different parts of your model, optimizer state, and gradient data.

With fiber memory, you'd want to optimize for sequential access patterns. Think of it like old-school tape memory or modern sequential SSDs: you want to minimize the number of times you wait for data to come around the loop.

This means restructuring your training algorithms to be more "memory-aware." Rather than random access, you'd structure computation in ways that access data sequentially or predictably.

Many modern AI training techniques already work this way. Transformer models, for example, can be structured to process data in sequential chunks. You'd want to optimize your training pipeline to process everything about a particular batch before requesting the next batch, rather than constantly jumping between different parts of memory.

Prefetching and Predictive Memory Access

Without the ability to do true random access, you'd need aggressive prefetching strategies. The system would need to predict what data you'll need next and start circulating it toward the access point in advance.

Modern CPUs do this with prefetchers that predict access patterns. A fiber memory system would need much more sophisticated prefetching because the cost of missing a prefetch prediction is higher (you wait an extra millisecond instead of a few nanoseconds).

Machine learning models could predict access patterns based on the structure of your neural network. You'd train the system on typical access patterns for your architecture, and then use those predictions to optimize prefetch scheduling.

Batching and Synchronization

AI training already uses batching extensively. With fiber memory, batching becomes even more important. You want to process large batches of data sequentially before accessing different parts of the model.

The training loop would look something like:

- Load next batch of training data from fiber memory (one sequential access)

- Compute forward pass on entire batch

- Compute backward pass on entire batch

- Update gradients

- Write updated parameters back to fiber memory

This is actually compatible with how modern GPUs already work. The difference is that instead of assuming you have random access to memory, you're explicitly managing which data is in transit.

New Optimization Algorithms

Training algorithms might need to adapt. Current optimizers like Adam or SGD assume they can access any parameter at any time. With latency-bound memory access, you'd want optimizers that:

- Accumulate gradients locally before writing back to memory

- Work with stale gradient estimates (computing on data from the previous loop cycle)

- Exploit temporal locality (parameters updated together tend to be accessed together)

Research in asynchronous stochastic gradient descent shows that you can still converge effectively even when working with slightly stale data, as long as the staleness is bounded and predictable.

Competing Technologies and Alternative Solutions

Phase-Change Memory (PCM) and Emerging Technologies

Fiber memory isn't the only wild idea being explored. Phase-change memory, which stores data by switching materials between crystalline and amorphous states, offers potential advantages:

- Lower latency than fiber memory (microseconds instead of milliseconds)

- Massive capacity (theoretically petabytes per device)

- Better power efficiency than DRAM

Companies like Intel and Micron have experimented with PCM technology. The challenge: PCM is slower than DRAM for write operations and has limited endurance (it can be written to maybe a million times before it degrades).

For AI training where you're constantly rewriting model parameters, PCM might not be ideal. But for inference where you're reading a fixed model repeatedly, PCM could be interesting.

3D DRAM and Advanced Memory Packaging

Current memory density is limited partly by how you can physically stack chips. 3D DRAM stacks memory vertically, potentially offering terabytes in a smaller footprint.

Companies are experimenting with stacking DRAM chips much more aggressively than traditional single- or dual-layer approaches. The benefits:

- Higher density without needing new fiber infrastructure

- Faster access than any optical system (still nanosecond latencies)

- Compatible with existing architectures

The problem: power consumption and heat dissipation in dense stacks are serious challenges. You can't efficiently cool a stack of 100 DRAM layers all consuming power simultaneously.

Quantum Computing and Quantum Memory

This is speculative, but quantum systems might approach memory differently. Quantum memory could potentially access superpositions of states rather than requiring sequential access to classical data.

But quantum computing is decades away from practical, large-scale applications. For the next 5-10 years, it's not relevant to the fiber memory discussion.

Specialized Custom Silicon

What if instead of trying to redesign memory, we redesign the compute hardware to work with existing memory constraints? Custom silicon designed specifically for AI training could:

- Maximize data reuse (reading the same parameter multiple times from memory)

- Use on-chip caching more aggressively

- Trade memory bandwidth for additional on-chip computation

This is actually what NVIDIA, Google TPUs, and other AI accelerators already do. Each generation gets better at working within memory constraints.

Implementation Timelines and Realistic Scenarios

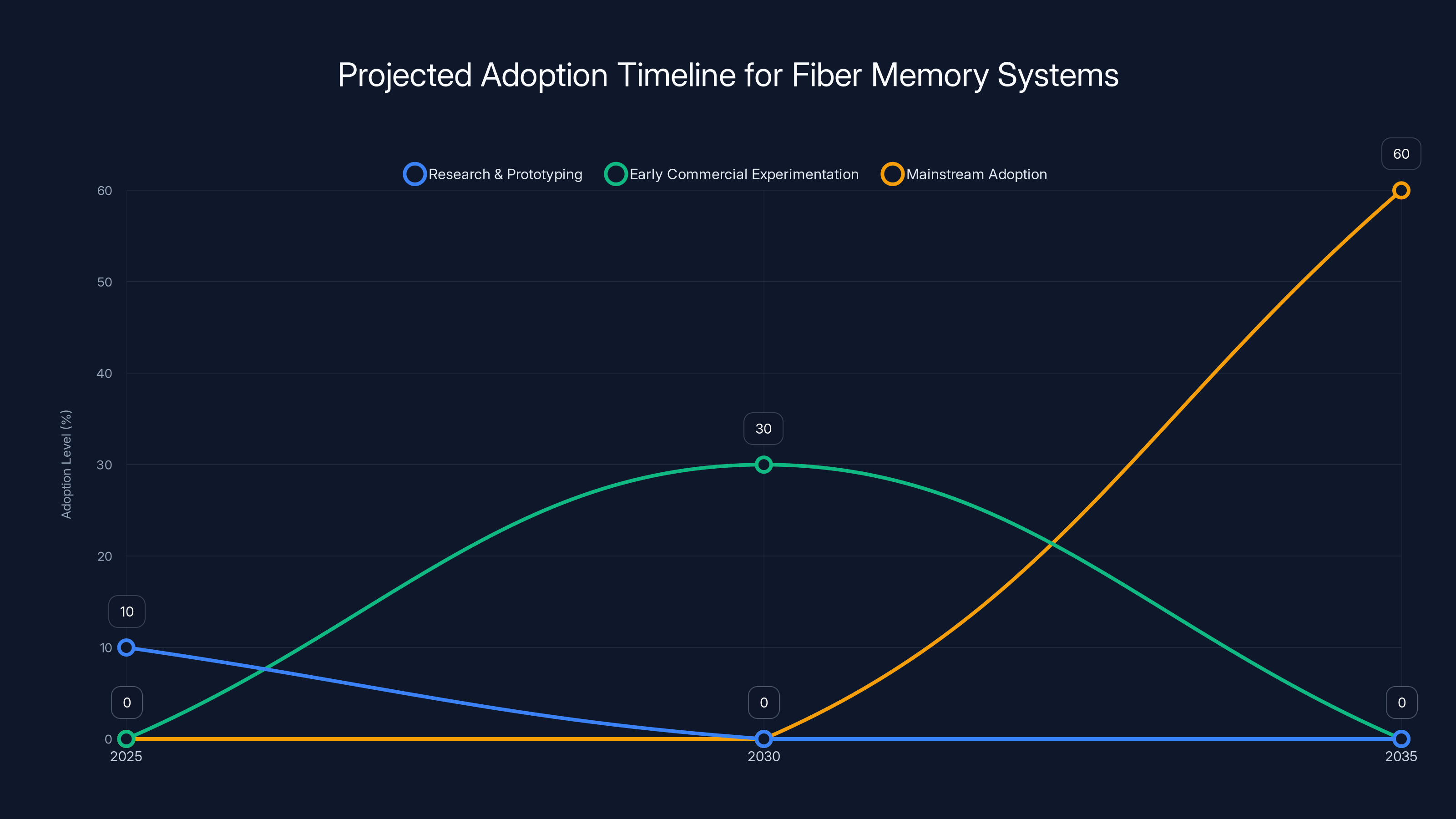

The 2-3 Year Horizon: Research and Prototyping

In the next couple of years, we'll see academic research labs build proof-of-concept fiber memory systems. These will be small (maybe 1-10 kilometer loops) and used for specific research purposes.

Expect papers published on:

- Optical switching at higher speeds than currently commercial

- Novel routing architectures for fiber memory

- AI training algorithms optimized for fiber memory constraints

No production systems. No real-world deployment. Just exploration of feasibility.

The 5-Year Horizon: Early Commercial Experimentation

Optimistically, by 2030, the first brave data center might experiment with a fiber memory system for specific, non-critical workloads. This would be like early Google using Map Reduce or AWS using custom Trainium chips—early adopters taking a risk for potential advantages.

At this point:

- Optical switching speeds might improve to sub-microsecond latencies

- Error correction mechanisms would be mature

- Software would exist to optimize training for fiber memory

- Infrastructure would exist to install and maintain the systems

Expect cost reductions of 20-30% for memory-intensive workloads, offset by complexity overhead.

The 10-Year Horizon: Potential Mainstream Adoption

If the technology matures, by 2035 larger data center operators might standardize on hybrid approaches:

- Small amount of traditional HBM for ultra-latency-sensitive operations

- Fiber memory for bulk working memory in AI systems

- Different pooling and switching architectures for different workload types

At this point, fiber memory might handle 50-70% of data center memory workloads and represent a genuine paradigm shift.

Potential Dead-End Scenarios

Alternatively, fiber memory might never materialize at scale because:

- Optical switching never gets fast enough, remaining the bottleneck

- Alternative technologies (3D DRAM, better PCM, quantum) solve the memory problem differently

- New algorithms that don't require massive working memory become dominant

- Economics never favor fiber despite theoretical advantages

This is actually pretty likely. The history of computing is littered with theoretically superior technologies that never achieved widespread adoption due to economic or practical constraints.

Estimated data suggests a 200km fiber loop costs around

The Broader Implications for AI Infrastructure

Data Center Architecture Evolution

If fiber memory does become viable, it would fundamentally change how data centers are designed. Instead of massive racks of GPU servers with local memory, you might have:

- Distributed compute nodes scattered throughout the data center

- Centralized fiber memory loops spanning the facility or multiple facilities

- Intelligent routing that moves data to wherever computation needs it

This is actually closer to how mainframes worked decades ago, except at AI scale and with optical technology instead of electrical buses.

Data centers would look less like dense racks of identical servers and more like interconnected hubs with varying specialization. Some hubs would handle compute, others would handle routing, others would be pure memory infrastructure.

Geographic Distribution of AI Training

One fascinating implication: with fiber memory, you could distribute the physical location of memory far from computation.

Imagine fiber loops running between cities, even between countries. Data circulates in the fiber, but computation happens wherever you want. You could train AI models using memory infrastructure located thousands of kilometers away from where the actual GPUs are running.

This opens possibilities for:

- Putting computation where electricity is cheap

- Putting memory where cooling is naturally available

- Building fault-tolerant systems where memory and compute are decoupled

- Sharing expensive memory infrastructure across multiple compute clusters

Environmental Impact

If fiber memory reduces power consumption by 10x as estimated, the environmental implications are massive. AI data centers currently consume roughly 2-3% of global electricity. Reducing that by even 10% across the board means preventing construction of additional power plants and associated grid infrastructure.

Fiber is also passive (once installed, it doesn't consume power to move data around like traditional systems do). This is fundamentally different from DRAM which constantly consumes power for refresh cycles and access operations.

The Business Model Implications

Systems that are cheaper to operate than existing infrastructure fundamentally change competitive dynamics. If fiber memory costs a tenth of current approaches, companies with access to this technology have a massive advantage in training larger models or offering cheaper services.

This could accelerate AI development because the economic barriers lower significantly. Smaller companies and research institutions could afford larger-scale training if the infrastructure cost drops by 10x.

Critical Perspectives: Why Some Experts Are Skeptical

The Latency Problem Isn't Actually Solved

While Carmack's proposal reduces latency variance, it doesn't eliminate it. A 1-millisecond worst-case latency sounds manageable until you consider that modern GPUs can execute millions of instructions per nanosecond.

In the time it takes for data to come around a 200km fiber loop, a GPU could have performed billions of computations. You're creating a scenario where the GPU is drastically underutilized, waiting for data that's always taking the long way around.

Optimized batch processing and prefetching might mitigate this, but skeptics argue you're never going to get the computational efficiency you have with low-latency DRAM.

Manufacturing and Infrastructure Challenges Are Understated

Installing 200 kilometers of fiber optic cable with optical amplifiers, cooling systems, and switching infrastructure in a data center is non-trivial. You need:

- Specialized contractors

- Custom infrastructure that doesn't exist yet

- Ongoing maintenance and monitoring

- Redundancy and fault tolerance (what happens if the fiber breaks?)

Compare this to buying standard GPUs with memory. GPUs are commodity hardware, well-understood, with existing supply chains. Fiber memory would require building entirely new infrastructure.

For a company like Open AI or Google, this might be manageable. For most organizations, it's probably unrealistic.

The "Keep It Simple" Argument

Perhaps the strongest skeptical argument is the elegance of continued DRAM improvements. DRAM density has roughly doubled every two years (following something like Moore's law) for decades. Optical amplifiers and optical switches are improving too, but not as predictably.

Why take on the complexity of fiber memory when continued incremental improvements in traditional memory might solve the same problems? By 2030, HBM memory might be half the cost and double the density of today. That's not as dramatic as the fiber memory promise, but it's also much more certain.

Economic Skepticism

Critics point out that Carmack's concept assumes fiber infrastructure is the main bottleneck, but maybe it's not. When you factor in:

- Infrastructure installation and setup

- Ongoing maintenance

- Specialized engineers needed to design and optimize systems

- Risk of the technology not working as expected

The actual cost advantage might be much smaller than theoretical calculations suggest. Maybe instead of 10x cheaper, it's 2x cheaper after all the real-world complications.

What Carmack Might Be Missing: Practical Constraints

The Speed of Light Problem

People often forget that while light is fast, it's not infinitely fast. If you need data that's currently at the opposite end of a 200km loop, you're waiting a minimum of 1 millisecond. With traditional DRAM, you're waiting tens of nanoseconds.

This is a million-times difference. Sure, DRAM might have bottlenecks and contention that sometimes make it slower, but on average, the speed advantage of traditional memory is enormous.

Some AI workloads can absorb this latency penalty through parallelism and careful scheduling. Other workloads simply can't.

Heat Dissipation Along Extended Routes

A fiber loop that's 200km long doesn't exist in a compact space. It's spread out over a geographic area. Dissipating heat from optical amplifiers scattered across this distance is genuinely difficult.

You can't build a nice data center cooling system that circulates cold water near all your hardware if the hardware is spread across dozens of kilometers.

Redundancy and Fault Tolerance

What happens when a section of fiber gets damaged? Your entire memory system could become inaccessible or degraded.

Traditional memory is in a single location with active redundancy and backup systems. Fiber memory would need distributed redundancy mechanisms that don't exist yet.

Quantum Computing Threat

If quantum computers become viable, they might break the encryption and error correction systems that fiber memory depends on. This isn't an immediate concern, but it's worth considering.

Latency in a 200-km fiber loop ranges from 0.001 to 1 ms, with an average of 0.5 ms. The loop can circulate up to 200 GB of data at 1.6 Tbps.

Practical Alternatives to Fiber Memory

Improving GPU Memory Controllers

GPUs are already getting better at managing memory efficiently. Newer architectures include better caching, prefetching, and memory scheduling algorithms.

As these improve, the gap between theoretical and actual memory performance closes. Maybe we don't need radical new architectures—just smarter use of existing ones.

Custom Silicon for AI

Instead of designing memory systems to fit existing algorithms, design algorithms to fit memory systems you can actually build.

Companies like Google (with TPUs) and Amazon (with Trainium chips) are already doing this. Each generation gets better at extracting value from available memory.

Edge AI and Distributed Training

Instead of centralizing everything in one massive data center, distribute training across many smaller clusters. Each cluster needs less memory, which might be more economically feasible with traditional approaches.

Federated learning and other distributed techniques might prove more practical than centralized mega-data-centers relying on experimental infrastructure.

Memory Pooling and Disaggregation

Instead of fixed memory attached to each GPU, pool memory resources and allocate dynamically to whoever needs it. This requires networking infrastructure but not fiber loops.

Companies like Microsoft are actively experimenting with disaggregated memory architecture. It might be the practical solution before fiber memory is ready.

Case Studies: Where Similar Rethinking Succeeded and Failed

Success: GPUs for AI Training

Twenty years ago, people thought you needed massive CPUs on high-speed interconnects for AI training. NVIDIA's bet on GPUs seemed weird. Why use gaming hardware for scientific computing?

But GPUs had something CPUs didn't: massive parallelism at lower cost. When the math aligned (and algorithms were written to exploit parallelism), GPUs became dominant.

Similar pattern to fiber memory: alternative architecture, lower cost, requires rethinking algorithms, eventually proves dominant if the technology matures.

Success: Solid State Drives Replacing Mechanical Storage

During the 2000s, many experts said SSDs would never be fast enough for servers. Mechanical drives had proven reliability and vast capacity advantages.

But SSDs improved exponentially. Within a decade, they dominated. The replacement was driven by:

- Rapid technology improvement

- Clear performance advantages (even if latency was higher, throughput and reliability improved)

- Economic shift as manufacturing scaled

- Software optimization to work with SSDs

Fiber memory could follow a similar trajectory.

Failure: Optical Computing

For decades, researchers bet on optical computing—using photons instead of electrons to do computation. All the theoretical advantages were there:

- Photons move faster

- Optical circuits could operate at higher frequencies

- Less heat generation

Why didn't it dominate? Because:

- The engineering was harder than expected

- Traditional electronics kept improving faster

- The ecosystem advantage (chips, software, tools) favored electronics

- Economics never worked out

Optical computing is still researched but never became mainstream.

Fiber memory might follow this path.

Failure: 3D Crossbars for Memory

In the 1990s, researchers proposed massive 3D crossbar architectures for memory, allowing true random access to enormous memory spaces.

Theoretically superior. Never deployed at scale because:

- Complexity exceeded benefits in practice

- Existing DRAM improvements solved the problems more incrementally

- Building 3D systems was harder than predicted

The Role of Software Optimization

Compiler Optimization for Fiber Memory

If fiber memory becomes viable, compilers would need to optimize for it specifically. Modern compilers are optimized for:

- CPU cache hierarchies

- GPU memory hierarchies

- Bandwidth limitations

Fiber memory has its own unique constraints. Compilers would need to:

- Predict memory access patterns far in advance

- Schedule data prefetching optimally

- Reorganize computation to minimize latency impact

- Reorder operations to maximize prefetch effectiveness

This is specialized work. You'd need compiler research specifically targeting fiber memory architecture.

Algorithmic Changes for Latency-Tolerant Computing

AI algorithms might need to fundamentally change. Current algorithms are:

- Memory-intensive

- Require frequent random access

- Assume latency is minimal

Algorithms optimized for fiber memory would be:

- More compute-intensive relative to memory access

- Use sequential access patterns

- Tolerate higher latencies

Research into "latency-tolerant" algorithms is already happening. If fiber memory becomes viable, this research accelerates.

Runtime Systems and Scheduling

Systems software (operating systems, runtime environments) would need to understand and optimize for fiber memory. This includes:

- Memory scheduling to maximize prefetch effectiveness

- Job scheduling that aligns memory access patterns

- Load balancing across memory pools

- Dynamic reconfiguration based on workload characteristics

You'd essentially be building specialized operating systems for fiber memory infrastructure.

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in fiber memory adoption, starting with research and prototyping by 2025, early commercial experimentation by 2030, and potential mainstream adoption by 2035.

Future Hybrid Architectures

The Practical Middle Ground

Realistic deployments might not be pure fiber memory or pure traditional RAM. Instead, you'd see hybrid systems:

- Tier 1: Traditional HBM or GDDR for ultra-latency-sensitive operations

- Tier 2: Fiber memory for large working datasets

- Tier 3: NVMe SSDs for spill and checkpointing

- Tier 4: Cloud object storage (S3, etc.) for long-term data

This tiering already exists, just at different price-performance points. Fiber memory would insert itself into the hierarchy.

Adaptive Memory Systems

Systems that dynamically choose which memory tier to use for different operations:

- Frequently accessed data: traditional memory

- Occasionally accessed bulk data: fiber memory

- Rarely accessed checkpoints: storage

This requires:

- Profiling and analysis of memory access patterns

- Dynamic migration of data between tiers

- Intelligent prefetching

- Runtime adaptation

Machine learning could help optimize these decisions automatically.

Disaggregated Architecture

Completely separate compute, memory, and storage into independent pools:

- Compute nodes (GPUs, TPUs)

- Memory nodes (fiber-based memory systems)

- Storage nodes (NVMe arrays, S3-compatible object storage)

- Interconnect (high-speed network)

This approach:

- Allows independent scaling

- Enables resource sharing

- Facilitates fault isolation

- Permits geographic distribution

Microsoft and other cloud companies are exploring this now. Fiber memory could be a key component.

Investment Implications and Startup Potential

Which Companies Should Be Interested?

Definitely interested:

- NVIDIA (memory bandwidth is a GPU bottleneck)

- Google, Microsoft, Meta (massive data center operators)

- Open AI, Anthropic (training the largest models)

Potentially interested:

- Optical component manufacturers

- Data center infrastructure companies

- New startups focused on disaggregated memory

Less interested:

- Traditional memory manufacturers (threatens their market)

- Cloud companies with commodity infrastructure focus (complexity concerns)

Startup Opportunities

If fiber memory becomes viable, opportunities exist for:

- Optical switching startups developing ultra-fast switches

- Memory system architects designing fiber-specific systems

- Software optimization companies building compilers and runtime systems

- Infrastructure service providers offering fiber memory as managed service

- Research institutions funded to solve fundamental problems

Research Funding Outlook

This is the kind of moonshot project that gets funded by:

- DARPA (military applications)

- NSF (basic research)

- Private tech companies' research labs

- Well-funded startups

Expect increasing research funding in this area as the memory crisis becomes more acute and AI training demands grow.

The Bigger Picture: Rethinking Computing Fundamentals

Why Do We Design Systems This Way?

Carmack's fiber memory proposal forces us to ask fundamental questions about why computing systems are structured as they are. We have:

- CPUs with L1, L2, L3 caches

- Main memory (DRAM)

- Disk storage (SSDs, HDDs)

- Network storage (cloud)

This hierarchy evolved for historical reasons. Maybe it's not optimal for AI workloads.

Rethinking the Memory Hierarchy

If we started from scratch designing systems for AI training in 2025, would we choose this architecture? Probably not. We might choose:

- Massive parallel compute

- Bulk sequential memory

- Intelligent prefetching and caching

- Fault-tolerant design

- Geographic distribution

Fiber memory is one way to achieve "bulk sequential memory" at scale.

Paradigm Shifts in Computing

History shows periodic shifts in computing paradigms:

- 1970s-80s: Minicomputers replacing mainframes

- 1980s-90s: Personal computers replacing minicomputers

- 2000s: Cloud computing introducing new paradigms

- 2010s-20s: AI/ML driving specialized hardware

- 2025+: ???

Fiber memory might be part of the next shift. Or it might be a dead-end explored in academic papers. Either way, it represents the kind of fundamental rethinking that drives progress.

Conclusion: John Carmack's Fiber Vision and the Future of Computing

John Carmack's proposal for fiber optic memory is simultaneously impractical and visionary. It's impractical because the technology doesn't exist yet, the engineering challenges are formidable, and the economic case depends on assumptions that might not hold.

It's visionary because it correctly identifies the real bottleneck in AI infrastructure—memory capacity and cost—and proposes a fundamentally different approach to solving it.

The memory crisis in AI is real. Companies training large models spend millions on memory infrastructure. The economics of scaling to ever-larger models with current approaches become increasingly challenging. Something has to give.

Carmack's fiber memory isn't necessarily the answer. It might be an evolutionary improvement in traditional memory. It might be a completely different approach we haven't thought of yet. It might be specialized algorithms that reduce memory requirements.

But the vision is important: we shouldn't accept current constraints as permanent. If a problem costs too much and consumes too much power, it's worth reconsidering from first principles.

Over the next 5-10 years, watch for:

- Academic research in optical switching improving latency

- Startups exploring novel memory architectures

- Cloud providers experimenting with disaggregated infrastructure

- Algorithm research in latency-tolerant computing

- Economic pressure driving adoption of alternative approaches

One of these threads might lead to something resembling Carmack's vision. Or they might lead somewhere entirely different.

What's certain is that the future of AI will be limited by infrastructure choices we make today. The companies and researchers who tackle the memory problem—whether through fiber, through new algorithms, or through approaches we haven't imagined—will shape the next decade of AI development.

Carmack's proposal might not work exactly as conceived. But it's the right kind of thinking for an industry that's about to hit fundamental limits.

FAQ

What is fiber optic memory storage?

Fiber optic memory uses looped fiber cables to continuously circulate data at the speed of light as a form of working memory, replacing traditional RAM chips. Instead of storing data statically in silicon, data travels through kilometers of optical fiber and returns to an access point repeatedly.

How would fiber optic memory improve AI training?

Fiber optic memory could reduce the cost of memory infrastructure by 10-100x and lower power consumption dramatically by eliminating expensive HBM memory and constant data movement. This would allow training of larger models and reduce operational costs for data centers, though with tradeoffs in access latency.

What are the main technical challenges preventing fiber memory deployment?

The primary challenges include optical switching latencies that aren't yet fast enough (microseconds needed instead of current milliseconds), maintaining signal integrity over long distances, distributing cooling along extended fiber paths, and building routing architectures that optimize memory access for fiber systems.

Could fiber memory replace traditional RAM completely?

Probably not completely for consumer systems where small form factor and instant access are essential. However, for large-scale AI data centers and enterprise computing, fiber memory could handle the bulk of working memory while traditional memory handles latency-sensitive operations.

When might fiber memory become commercially available?

Realistically, production systems are probably 5-10 years away at the earliest. We're currently in the theoretical and early research phase. Academic prototypes might emerge in 2-3 years, but scaling to practical data center deployment requires solving multiple technical challenges.

How does the cost of a 200km fiber loop compare to current GPU memory costs?

A 200km installed fiber loop costs roughly

Would artificial intelligence algorithms need to change for fiber memory?

Yes, AI training algorithms would need optimization for fiber memory's access patterns. Current random-access algorithms would become sequential or predictively-prefetched algorithms. This requires specialized compiler optimizations and potentially new algorithmic approaches designed for latency-tolerant computing.

What alternatives to fiber memory exist for solving the AI memory crisis?

Alternatives include advanced 3D DRAM stacking, phase-change memory (PCM) with better write endurance, improved GPU memory controllers with better prefetching, disaggregated memory architectures over high-speed networks, and algorithms designed to reduce overall memory requirements.

Could fiber memory work across geographic regions?

Theoretically yes—you could have fiber loops spanning cities or countries with data circulating remotely while computation happens locally. This could enable cost arbitrage by separating memory infrastructure location from compute location, though synchronization and fault tolerance become more complex.

What would happen if a fiber cable breaks in the system?

A single break would likely degrade the system significantly, as data is constantly circulating through the loop. You'd need redundancy mechanisms such as dual parallel loops, mirrors, or rapid reconstruction algorithms—adding complexity and reducing the cost advantage of the system.

Related Concepts for Deeper Learning

For readers interested in exploring related technologies and concepts, consider researching:

- Optical switching architectures and Silicon Photonics

- Disaggregated data center infrastructure

- Memory-efficient training techniques for neural networks

- Wavelength Division Multiplexing (WDM) in fiber optics

- Custom hardware for AI (Google TPUs, AWS Trainium)

- Asynchronous training algorithms for distributed systems

- Photonic neural networks and optical computing research

- Data center power optimization and liquid cooling

- Hardware-aware algorithm design for memory-constrained systems

- Fiber optic infrastructure in modern data centers

Key Takeaways

- John Carmack proposes replacing RAM with fiber optic loops that circulate data at light speed—a radical architecture that could cost 100x less than current HBM memory approaches

- The AI memory crisis is real: training large language models requires terabytes of high-speed memory, with costs exceeding $6-8 billion for 1PB of HBM capacity in a single data center

- Fiber memory could reduce infrastructure costs by 10x and power consumption by 30x, but requires optical switching speeds 1000x faster than currently available—technology that won't be production-ready for 5-10 years

- Implementation would fundamentally change AI training algorithms from random-access to sequential patterns, requiring specialized compilers and completely redesigned data center architectures

- Alternative technologies like 3D DRAM, phase-change memory, and algorithm optimization might solve the memory problem before fiber optic systems become viable, despite fiber's theoretical advantages

![John Carmack's Fiber Optic Memory: Could Cables Replace RAM? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/john-carmack-s-fiber-optic-memory-could-cables-replace-ram-2/image-1-1770756291897.jpg)