Josef Fares on AAA Innovation: How Big Budgets Still Push Gaming Forward

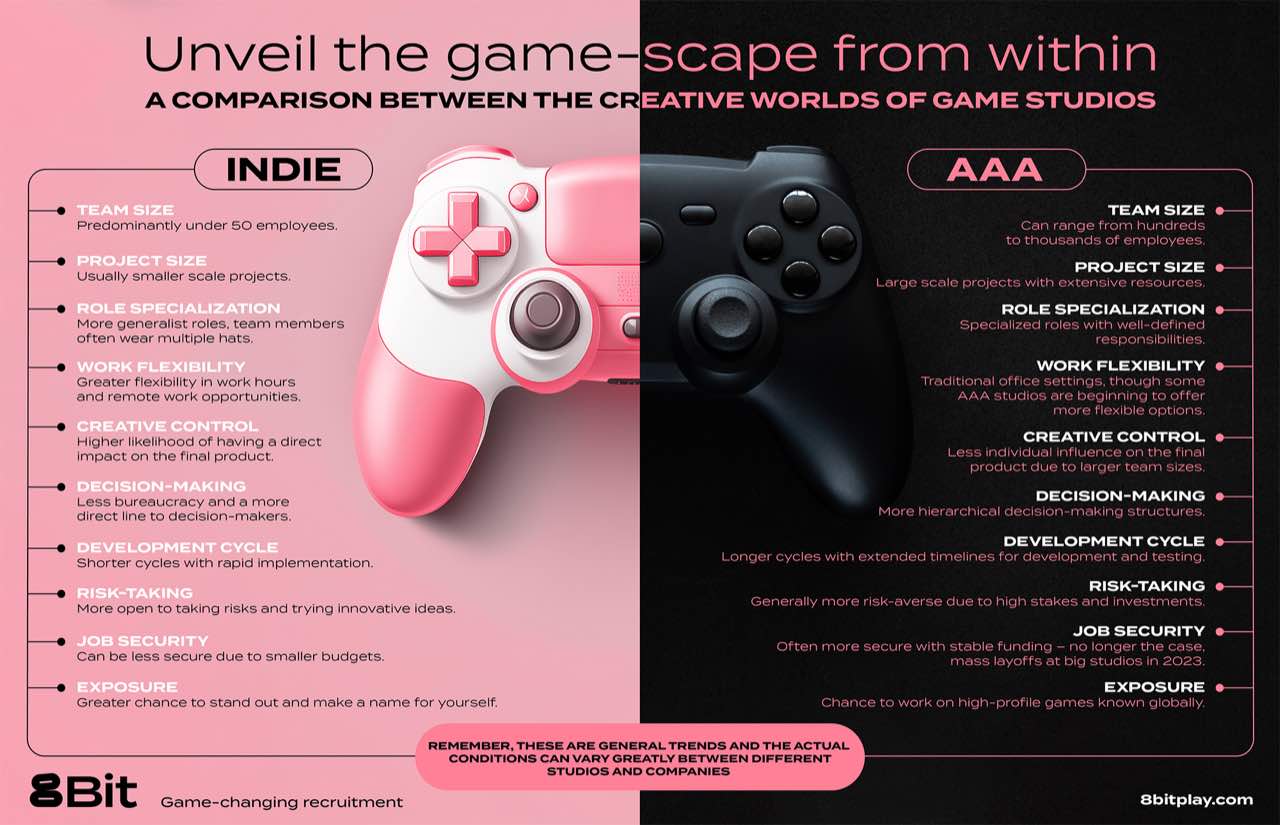

There's this persistent myth in gaming that innovation happens exclusively in indie studios. You know the narrative: scrappy teams with shoestring budgets creating revolutionary experiences while massive AAA publishers play it safe with sequels and live-service games.

But Josef Fares, the director behind cultural phenomenons like It Takes Two and Split Fiction, isn't buying it.

In a recent interview with The Game Business, Fares made a compelling counterargument. He suggested that AAA studios like Naughty Dog, Nintendo, and Rockstar Games are actively pushing the boundaries of what gaming can be, despite (or maybe because of) their massive budgets. It's a statement that feels especially relevant right now, as the industry grapples with questions about development costs, creative risk-taking, and what the future of game design actually looks like.

This isn't just philosophical musing either. Fares has lived the reality on both sides. He runs Hazelight Studios, an EA-published team that's created games like A Way Out and Split Fiction that consistently break conventional design thinking. Split Fiction alone reached 1 million copies sold in its first month and landed a perfect 5-star review in major outlets. So when he says AAA budgets can drive innovation, he's not speaking from theory.

The gaming industry stands at an interesting inflection point. Development budgets have skyrocketed over the past decade. Games that cost over $100 million to produce are becoming increasingly common. At the same time, indie games continue to capture player hearts and critical acclaim with a fraction of those budgets. This has created an ongoing debate: does bigger actually mean bolder, or does it mean blander?

Fares' perspective offers a nuanced answer. Yes, larger budgets create organizational complexity and risk-aversion at certain thresholds. But they also enable technical ambition, creative scale, and the resources to execute genuinely innovative ideas that smaller teams simply couldn't attempt.

Let's dig deeper into what Fares means, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of game development.

Understanding the AAA Innovation Paradox

The biggest misconception about AAA game development is that larger budgets automatically equal less innovation. This idea probably came from legitimate observations: yes, there are AAA games that play it safe. But the logic doesn't follow universally.

When you have $100 million to spend on a game, you can afford to experiment with entire systems that might fail. You can hire specialized talent for experimental features. You can iterate on core mechanics dozens of times. You can build entirely new engine technology if needed. These aren't luxuries available to most indie teams.

Consider the technical side. Games like Red Dead Redemption 2 from Rockstar Games implemented things that were genuinely unrealized in gaming before: the level of environmental interaction, the AI sophistication, the narrative structure built into emergent gameplay. These required resources that only major studios could commit. Similarly, Naughty Dog's work on motion capture, animation blending, and accessibility features in games like The Last of Us Part II represented innovation that required dedicated teams and years of R&D.

Nintendo's approach is slightly different but equally innovative. They consistently prove that innovation isn't about graphical fidelity or raw processing power. Games like Breath of the Wild fundamentally changed how open-world games could work by giving players agency to approach puzzles in any order. That was AAA innovation that came from a specific creative vision and the resources to realize it fully across an entire game world.

But here's where Fares identifies the real constraint: once you cross the threshold into truly massive budgets, the dynamics shift.

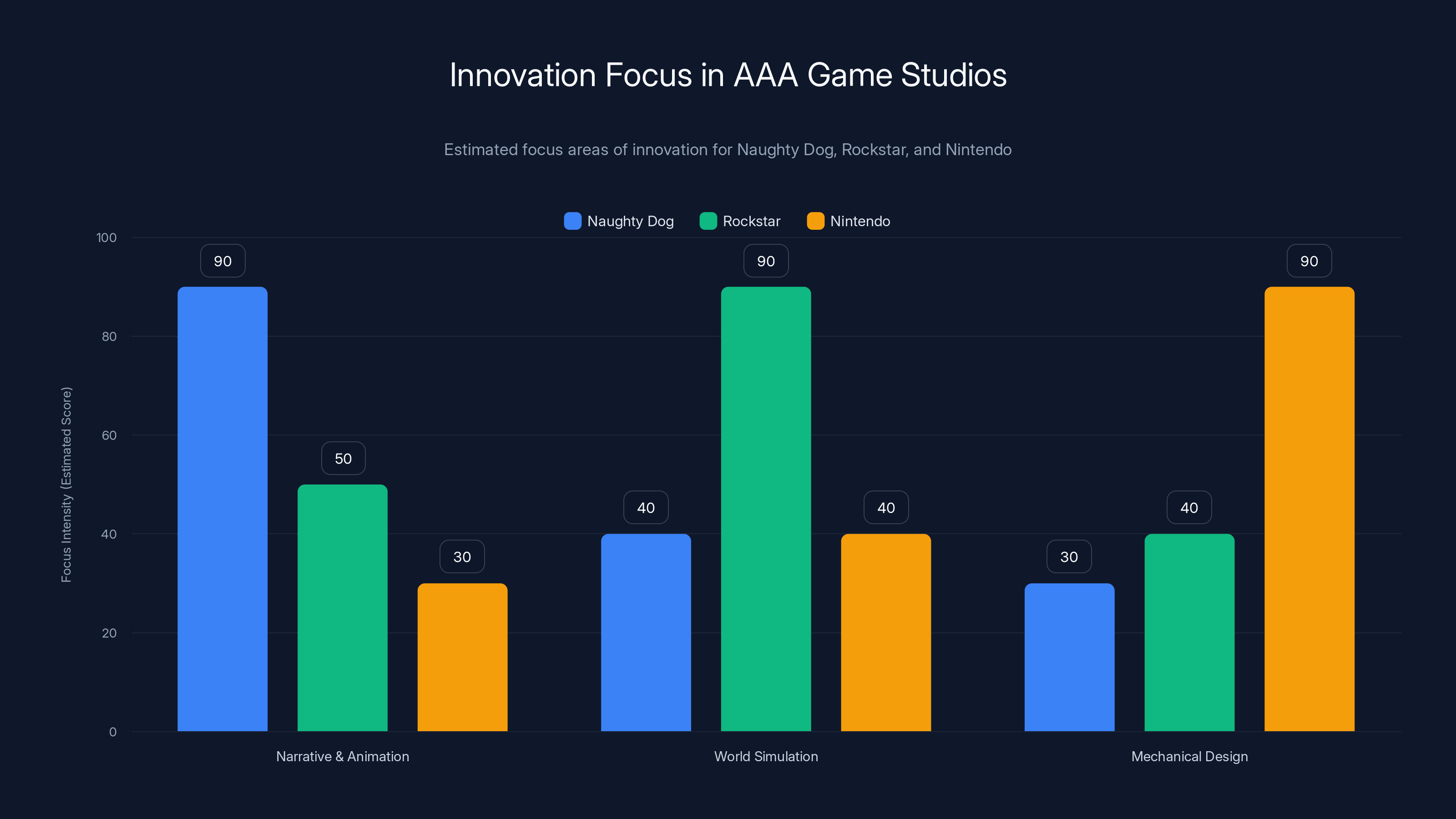

Estimated data shows that Naughty Dog emphasizes narrative and animation, Rockstar focuses on world simulation, and Nintendo prioritizes mechanical design. Each studio innovates in distinct areas within the AAA space.

The $100 Million Problem: Where Risk Meets Reality

Fares doesn't shy away from the complications. He explicitly acknowledges that somewhere beyond the $100 million mark, something changes psychologically in development.

"Once you go over a $100 million dollar budget, you're going to be like, 'okay, sh*t. There's a lot of money on the table'. People are more scared. It's understandable," he explained in the interview.

This is where his nuance becomes important. Fares isn't arguing that all AAA games are innovative or that bigger budgets always lead to bigger creative swings. He's arguing that it's possible to innovate at scale, even when budgets are enormous. The constraint is psychological, not financial.

When you've spent $150 million on a game, you're not thinking about bold creative experiments that might fail. You're thinking about safe design decisions that maximize appeal and minimize the chance of commercial failure. You're thinking about which franchises work, which mechanics are proven, which genres have track records.

This is why you see patterns in AAA games: the cover-based shooter template, the open-world structure with towers and collectibles, the cinematic narrative framework. These emerged because they worked, and once something works at that budget scale, the pressure to repeat it becomes immense.

But Fares' actual point is that Nintendo, Rockstar, and Naughty Dog have found ways to break this pattern. They've managed to take genuine creative risks within AAA budgets. Some of these risks don't pay off commercially (Rockstar's experimental open-world design in Red Dead Redemption 2 was controversial precisely because it valued artistic vision over player agency in some moments). But they remained committed to innovation anyway.

The question becomes: how do they do this when everyone else seems stuck in a loop of safe design?

Naughty Dog: The Animation and Narrative Innovation Model

Naughty Dog represents a specific type of AAA innovation: the artistic and narrative frontier.

Their games, particularly The Last of Us franchise and Uncharted series, don't push boundaries through novel gameplay mechanics. Instead, they innovate in storytelling, character development, and player animation. They made the choice to pursue something that wasn't necessary for commercial success but was worth the investment: the most sophisticated character animation systems in gaming.

When Joel grabs something, his hands wrap around it with individual finger animation. When Ellie moves through tall grass, you see her legs push through it individually. When characters converse, the microexpressions in their faces respond realistically to dialogue. None of this is strictly necessary to tell a story. You could communicate the exact same narrative with simpler animation.

But Naughty Dog believed these details mattered for emotional connection. They created entire departments focused on animation fidelity. They invested in capture technology and post-processing that most studios would consider excessive. They built custom tools to manage animation complexity at a scale most games never approach.

The Last of Us Part II cost approximately $220 million to develop (including marketing). That's not frivolous spending on safe mechanics. That's spending on innovation that doesn't directly feed gameplay but feeds storytelling and atmosphere. It's a choice only AAA budgets can really support, and it's fundamentally innovative in its commitment to one specific aspect of the craft.

Their accessibility features represent another form of innovation. Naughty Dog didn't include detailed accessibility options because they were required. They included them because someone had the resources and the will to spend development time on features that serve a smaller subset of players. This is AAA-scale innovation in service design.

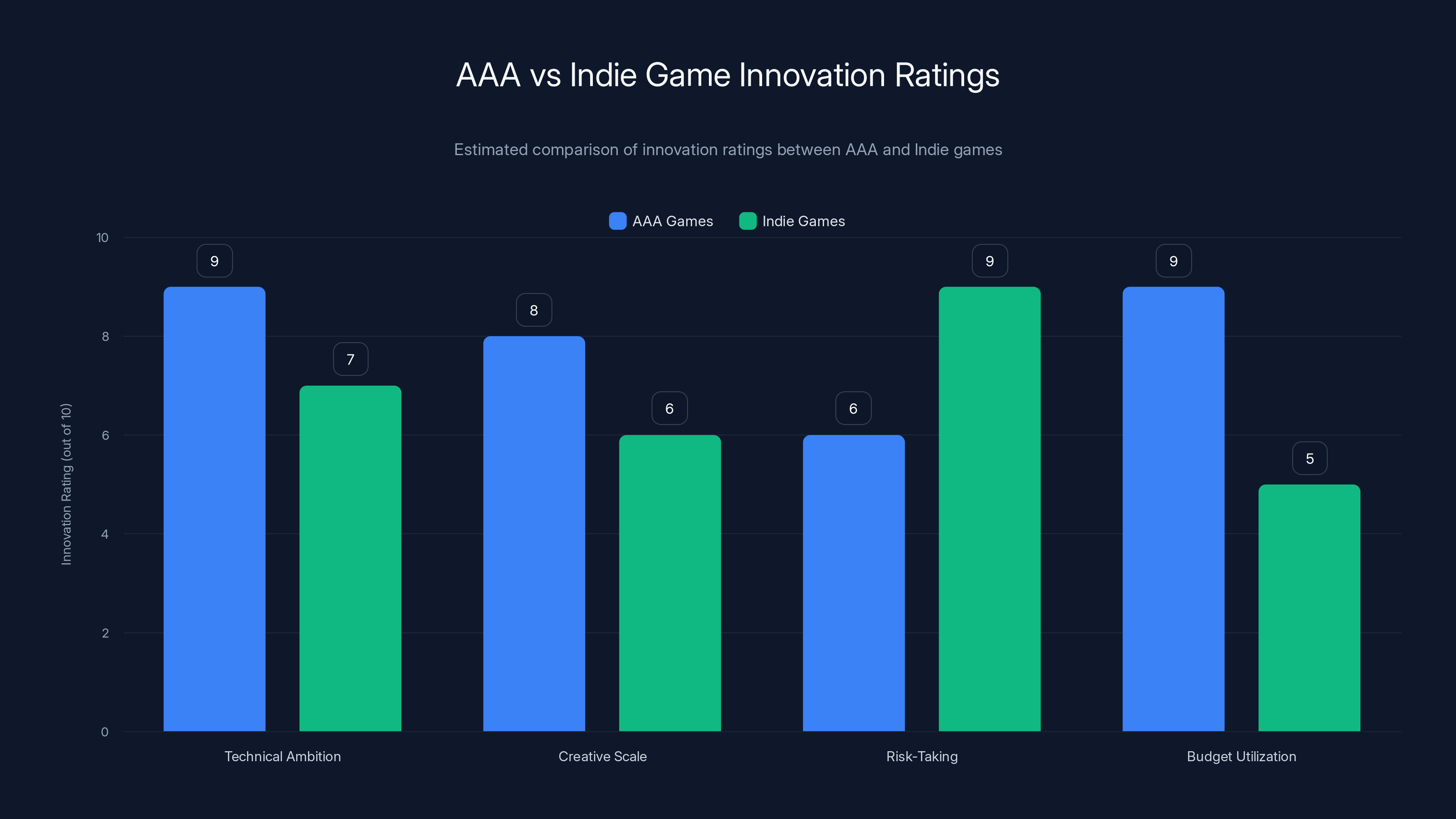

AAA games often excel in technical ambition and budget utilization, while indie games lead in risk-taking. Estimated data highlights the strengths of each sector.

Rockstar Games: The Emergent Systems and Scale Innovation

Rockstar represents a different model: systems-level innovation at massive scale.

Red Dead Redemption 2 is a four-year development cycle that consumed over 3,000 hours of developer time. That scale of commitment allowed Rockstar to build staggeringly complex simulation systems underneath the narrative experience.

The game doesn't just have animals in the world. It has an actual ecosystem where predators hunt prey, where populations migrate seasonally, where you can track animals and interact with them in dozens of different ways. This level of simulation required building systems that most studios never even attempt.

Rockstar also innovated in the relationship between story and player agency. Traditional AAA narrative games put you on rails during story moments. Red Dead Redemption 2 blended story scripting with emergent simulation in ways that created unique moments for every player. Your particular decisions, your approach to missions, your choices in how to handle situations—these all created variations in how story beats played out.

Was it always successful? Not necessarily. Some players felt the game prioritized cinematic vision over player agency. But that tension itself was an innovation: exploring the boundaries of where cinematic design and player choice can coexist.

The sheer scale of the game world—with detailed interiors for buildings you might only visit once, with NPCs that have daily routines you'll never fully witness, with environmental storytelling that rewards exploration—this all represents AAA innovation. You simply cannot create this level of world simulation on a smaller budget.

Rockstar's latest Grand Theft Auto 6 trailer showcased similar commitment to simulation and environmental detail. The world feels alive in ways that required massive resources to achieve.

Nintendo: The Mechanical and Design Innovation Standard

Nintendo's approach to innovation looks different from Naughty Dog or Rockstar, but it's no less genuine.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild fundamentally changed open-world design. This wasn't an incremental improvement on existing formulas. It was a rethinking of how open-world games should work. Nintendo committed resources to exploring a vision where players could approach challenges in any order, where physical systems matter more than quest markers, where the game never restricts your path.

This required innovation in several directions simultaneously: level design that works when approached from any angle, AI systems that react to unpredictable player approaches, environmental physics that enable multiple solutions to puzzles. These weren't luxuries. They were fundamental to the vision.

Super Mario Bros. Wonder represented similar innovation in the 2D platformer space. The game wasn't a safe iteration on existing Mario mechanics. It introduced entirely new power-up systems and transformation mechanics that fundamentally changed how levels could be designed.

Nintendo's approach tends toward mechanical and design innovation rather than graphical or narrative innovation. But it's no less ambitious. In fact, it might be more constrained by requiring that the innovation actually serve gameplay in meaningful ways.

Switch as a platform itself is an innovation story. The decision to build a mobile-capable home console was considered insane by much of the industry. But Nintendo had the resources and the willingness to take that risk. It paid off commercially, but before launch, it was a genuine gamble that only a company with resources could make.

Josef Fares and Hazelight Studios: The Midpoint Perspective

Hazelight Studios operates in an interesting middle ground. They're EA-published, which gives them AAA resources and publishing reach. But they maintain significant creative autonomy and operate with budgets much smaller than the true AAA blockbusters (likely in the $20-50 million range based on industry estimates).

This position gives Fares unique insight into both worlds. It Takes Two and Split Fiction both demonstrate how AAA-scale budgets can support genuine innovation without requiring $150+ million spend.

It Takes Two innovated by making co-op the core mechanic rather than an afterthought. This required building every single game system around the assumption that two players would be present. It required level design that worked specifically for co-op, storytelling that incorporated player partnership, and mechanics that fundamentally couldn't work in single-player.

Split Fiction continued this philosophy with romance-focused storytelling integrated into co-op gameplay. Neither game was a safe iteration on established franchises. Both required creative vision backed by sufficient budget to realize that vision fully.

Fares' position is that what Hazelight does proves the point: you don't need massive budgets to innovate at AAA scale, but you do need sufficient resources to realize creative vision. A game needs enough budget to polish, to iterate, to build systems that work the way the designers intended.

The distinction matters. It's not that bigger budgets automatically enable innovation. It's that innovation at any scale requires sufficient resources to execute vision properly. Sometimes that's

Naughty Dog's significant investment in animation and storytelling highlights their commitment to narrative innovation. Estimated data.

The Risk Management Problem in AAA Development

One reason large budgets create conservative design is organizational rather than financial. When you're spending $150 million, you need approval structures, committees, risk assessment frameworks. You're probably answering to shareholders or parent companies. You have marketing teams that have tested what audiences want. You have quarterly earnings to consider.

Smaller studios often have decision-making power concentrated in hands of people with genuine creative authority. Bigger studios distribute it across dozens of stakeholders. This isn't inherently wrong—it allows for scaling production and managing complex projects. But it creates natural friction toward bold choices.

Fares acknowledges this but argues it's not inevitable. He points to studios that have maintained creative autonomy even at large scale. Naughty Dog has historically had strong leadership that could make decisions. Nintendo operates with clear creative vision from the top. Rockstar has had consistent leadership that prioritizes their artistic vision over other concerns.

These aren't accidents. They're deliberate choices about organizational structure and decision-making authority. When leadership prioritizes innovation over risk-minimization, innovation happens even with massive budgets.

The challenge is that this requires leadership willing to absorb financial risk. Not every publisher or studio is comfortable with that. Some prefer the predictability of proven formulas. That's a valid business choice, but it's not a constraint of AAA development itself.

How Budget Constraints Actually Spark Different Innovation

Interestingly, Fares' argument doesn't diminish indie innovation. It actually recontextualizes it. Indie games innovate under different constraints, which often produces different types of innovation.

With limited budgets, indie developers must innovate in design, art direction, and conceptual focus. They can't build massive worlds, so they build more intentional ones. They can't hire orchestras, so they develop more creative audio design with limited resources. They can't iterate for years, so they make bolder choices faster.

This produces genuine innovation. Games like Hades, Hollow Knight, and Celeste represent real breakthroughs in design thinking. They happened because developers worked within constraints creatively.

But the question Fares raises is: does this mean AAA games can't innovate? His answer is clearly no. The constraints are different, but they don't prevent innovation. They just produce different kinds of innovation.

AAA games can innovate by pursuing scale: building game worlds so detailed and alive that simulation itself becomes the innovation. They can innovate by pursuing fidelity: making animation so precise that emotional communication changes. They can innovate by pursuing systems: building mechanical depth that emerges across 60+ hours of gameplay.

None of these are possible at smaller scales. But they're not less innovative than what indie games do. They're differently innovative.

The challenge isn't that AAA development prevents innovation. The challenge is that innovation is risky, and risk management becomes harder as budgets increase. Fares' actual argument is that this is surmountable through leadership and organizational choice.

The Generative AI Question: Fares' Vision for Future Innovation

The interview with Fares also touched on generative AI and its role in game development. His perspective here is notably measured.

"I don't see AI taking over. I don't. But it's really hard to answer. Who knows what happens in the future?"

This matters because it shows how someone thinking deeply about innovation actually approaches potentially disruptive technology. He's not dismissive, but he's skeptical of apocalyptic narratives. He's open to possibility while maintaining healthy doubt.

What Fares likely understands is that AI in game development will follow a pattern we've seen with other technologies: it will handle certain tasks remarkably well, it will be useful as a tool for human developers, and it will create new bottlenecks somewhere else.

AI might make asset creation faster. It might help generate level layouts or narrative variations. It might assist with quality assurance testing. These are genuine improvements. But games also require taste, judgment, and intentionality about what experience players should have. AI is better at execution than at vision.

The innovative games ten years from now will probably use AI somewhere in the pipeline. But the innovation will still come from teams making bold creative choices about what games should be. The tools change. The core human activity remains.

Fares' skepticism about AI "taking over" suggests he understands this distinction. Innovation requires vision, and vision is still a human capability.

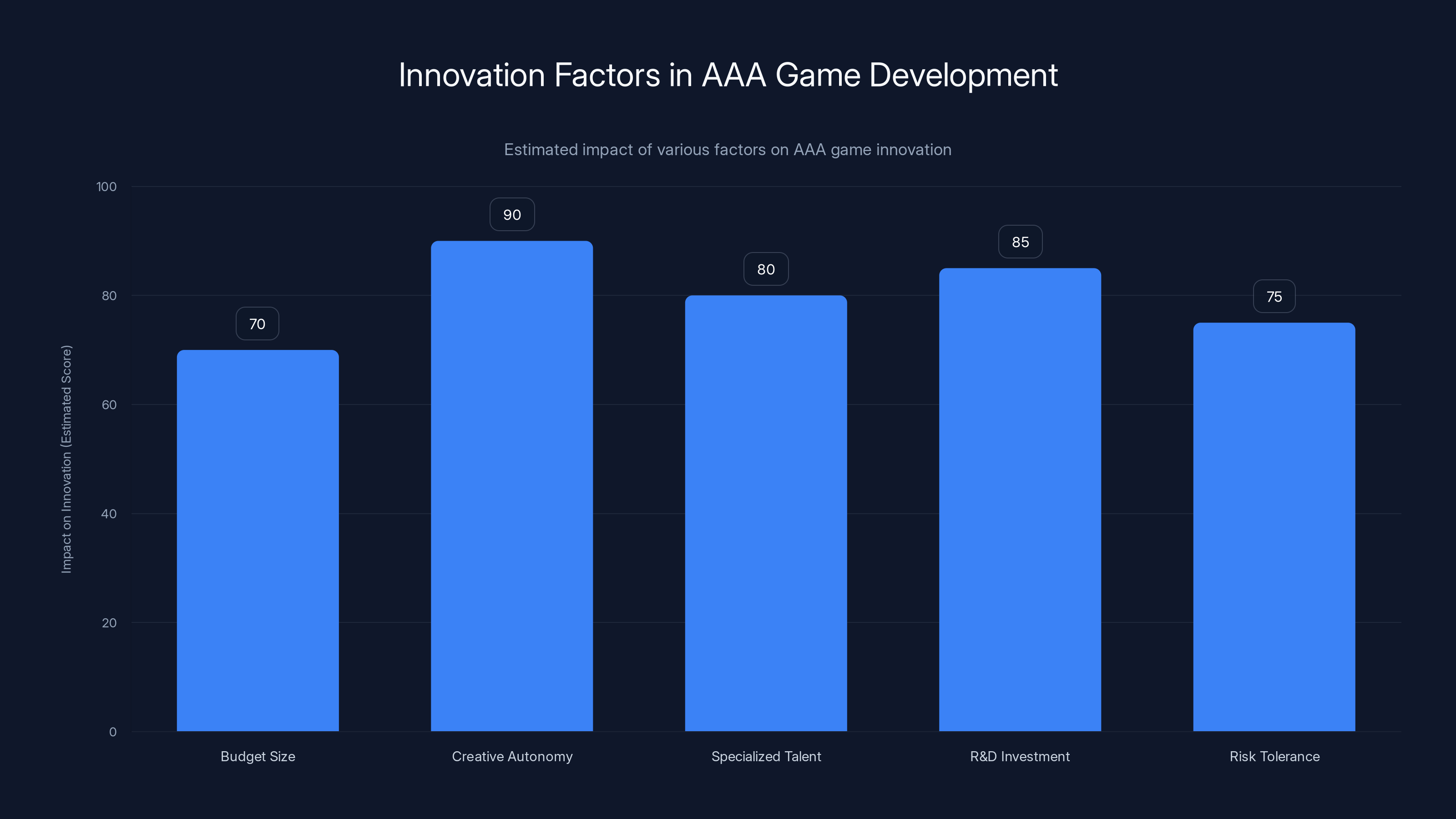

Creative autonomy and specialized talent are estimated to have the highest impact on innovation in AAA game development, surpassing even budget size. Estimated data.

What This Means for Gaming's Future

If Fares is right—and the evidence from studios he points to suggests he is—then the industry's future might look different than some pessimists predict.

The narrative of AAA stagnation suggests gaming's most innovative work happens outside major publishers. But Fares argues that narrative misses important reality. Nintendo, Rockstar, and Naughty Dog continue pushing boundaries. Their budgets enable that pushing.

This doesn't mean every AAA game is innovative. Many prioritize profit and safety. But some don't, and the existence of those games proves that innovation at scale is possible.

The real issue might be that consumers don't always reward AAA innovation. Red Dead Redemption 2 was commercially successful, but many players wanted more agency and less rigid narrative structure. Naughty Dog's games are acclaimed, but some players find them too linear and cinematic. Nintendo's innovations always sell, but that's partly because they have incredible brand loyalty.

If innovation always maximized profit, we'd see more of it. The fact that Fares has to argue for the possibility suggests that many studios don't believe it's worth the risk-reward. That's the real constraint: cultural and economic beliefs about what AAA games should be, not anything inherent to large budgets.

The Split Fiction Case Study: Proof of Concept

Fares' argument gains credibility from Split Fiction itself. The game launched in March 2025 to critical acclaim and strong sales, proving his philosophy works in practice.

Split Fiction is explicitly designed around innovation in storytelling and co-op mechanics. It tackles romance as a narrative framework for a game, something most titles avoid. It's a deliberately artistic choice backed by sufficient resources to execute it fully.

The game isn't cheap to make, but it's not a $200 million blockbuster either. It exists in the space where Fares' argument lives: sufficient budget to innovate, but not so much that risk-aversion becomes inevitable.

The critical response was overwhelmingly positive, with outlets praising its willingness to take narrative and mechanical risks. Players engaged with it deeply. It sold over 1 million copies in its first month. This is the proof that AAA innovation works commercially.

Split Fiction doesn't represent the only path for AAA innovation, but it demonstrates that the path exists. You can make a big-budget game with genuine creative vision, and audiences will respond.

Comparing AAA Innovation Models: Different Approaches, Same Commitment

What's interesting when you compare Naughty Dog, Rockstar, and Nintendo is that they innovate in completely different directions while maintaining the same commitment to pushing boundaries.

Naughty Dog pushes toward emotional storytelling and animation fidelity. Rockstar pushes toward world simulation and emergent gameplay. Nintendo pushes toward mechanical design and accessibility. These aren't the same type of innovation, but they're all genuine innovation backed by serious resources.

A smaller studio might innovate in one direction simply because they lack resources for others. A five-person indie game team can't build a world simulation like Rockstar's. But they might create brilliant mechanical innovation that gets overlooked because it's not flashy.

AAA studios have the luxury of pursuing multiple innovation directions simultaneously. This isn't always used well—many AAA games are massive but mechanically shallow. But when it's used intentionally, it produces something genuinely special.

The distinction matters: innovation capacity is different from innovation execution. AAA budgets enable capacity. Whether that capacity produces actual innovation depends on leadership vision and creative willingness to take risks.

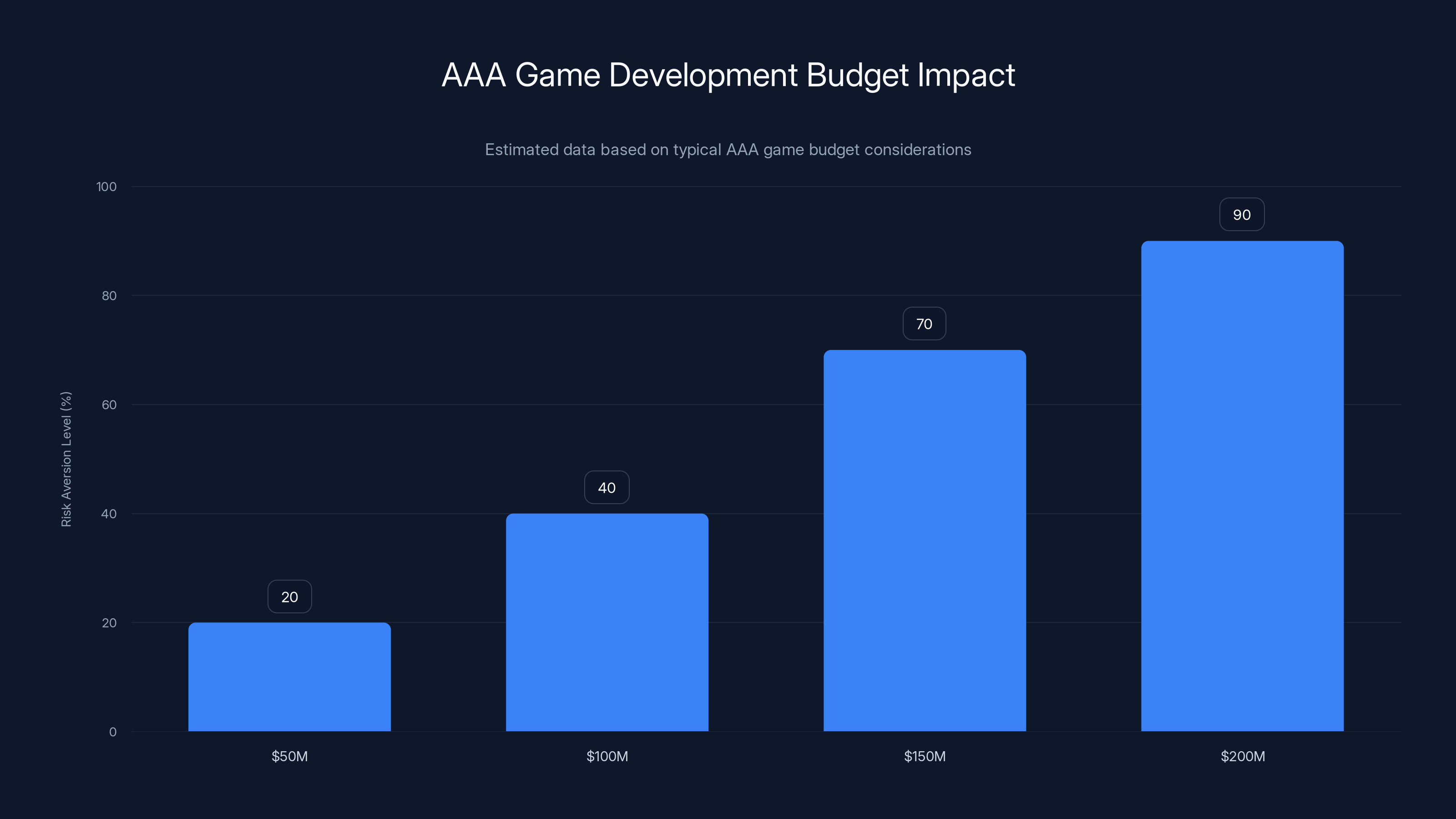

As AAA game budgets increase, developers tend to become more risk-averse, focusing on proven design templates. Estimated data.

The Cultural Shift Needed in AAA Development

If Fares is arguing that AAA innovation is possible but underutilized, then the question becomes: how do we see more of it?

Partially through market signals. Games like Split Fiction that take genuine risks and succeed commercially show publishers that audiences respond to innovation. Every successful novel AAA game makes the next one slightly less risky.

Partially through leadership. Studios that have clear creative vision and leadership willing to protect that vision from committee decisions make better games. This isn't about eliminating collaboration—Naughty Dog, Rockstar, and Nintendo all emphasize team creativity. It's about having clear direction and trusting the team to execute toward it.

Partially through industry culture. When development communities celebrate innovation and discuss it seriously, it influences what people pursue. If "AAA games are safe" becomes the dominant narrative, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If "AAA studios innovate differently than indie studios" becomes the narrative, it opens space for different types of innovation.

Fares' interview does cultural work by pushing back on the stagnation narrative. He's arguing that the emperor might be wearing clothes, and we've just been distracted by flashy indie alternatives.

None of this means every AAA game should be wildly experimental. There's genuine value in well-executed traditional games. But the idea that AAA budgets prevent innovation is demonstrably false. They enable different forms of innovation, pursued in different ways.

Where AAA Innovation Happens: The Pockets of Possibility

If you look at where genuine AAA innovation happens, it's almost always in studios that have:

- Clear creative vision: Leadership articulates what the game is trying to do.

- Time to experiment: Development cycles long enough to try things and iterate.

- Technical investment: Resources devoted to solving hard technical problems.

- Organizational autonomy: Decision-making authority that doesn't require constant committee approval.

- Publisher support: Publishers that understand risk and give teams space to fail.

Nintendo checks all five boxes. Naughty Dog checks four and a half (the publisher support is internal, but Play Station Studios has given them remarkable autonomy). Rockstar checks all five.

Many AAA studios check none of these boxes. They operate on established franchises, short development cycles, proven technical pipelines, rigid approval structures, and publishers focused on quarterly earnings. In that context, innovation becomes nearly impossible not because budgets prevent it, but because the organizational structure doesn't permit it.

The question isn't whether AAA development enables innovation. The question is whether specific studios structure themselves to enable it. Fares' point is that some do, and that matters.

This also suggests a path forward for more AAA innovation: studios need to make structural choices that permit risk-taking. That might mean longer development cycles. It might mean more organizational autonomy. It might mean publishing partners willing to absorb financial risk.

These are choices, not constraints. Some studios are making them. More could if they chose to.

The Economics Behind AAA Risk-Taking

Underlying all of this is an economic reality: innovation is risky, and risk becomes more terrifying at larger scales.

If you spend

This isn't irrational risk-aversion. This is prudent business management. The question is whether publishers and studios structure themselves in ways that balance risk management with innovation possibility.

Some do this through portfolio approaches: having both safe franchise entries and experimental projects. Some do it through smaller-budget innovation, like what Hazelight does. Some do it through IP variation, like how Nintendo uses established characters (Mario, Link, Donkey Kong) in new mechanical contexts.

The economic structure shapes innovation possibility. But the structure is chosen. Publishers could decide to allocate more budget to experimental AAA projects. Publishers could decide to fund more mid-tier games like Split Fiction. Publishers could decide that innovation is worth the financial risk.

Some do. Most don't. This isn't about capability. It's about priority and risk appetite.

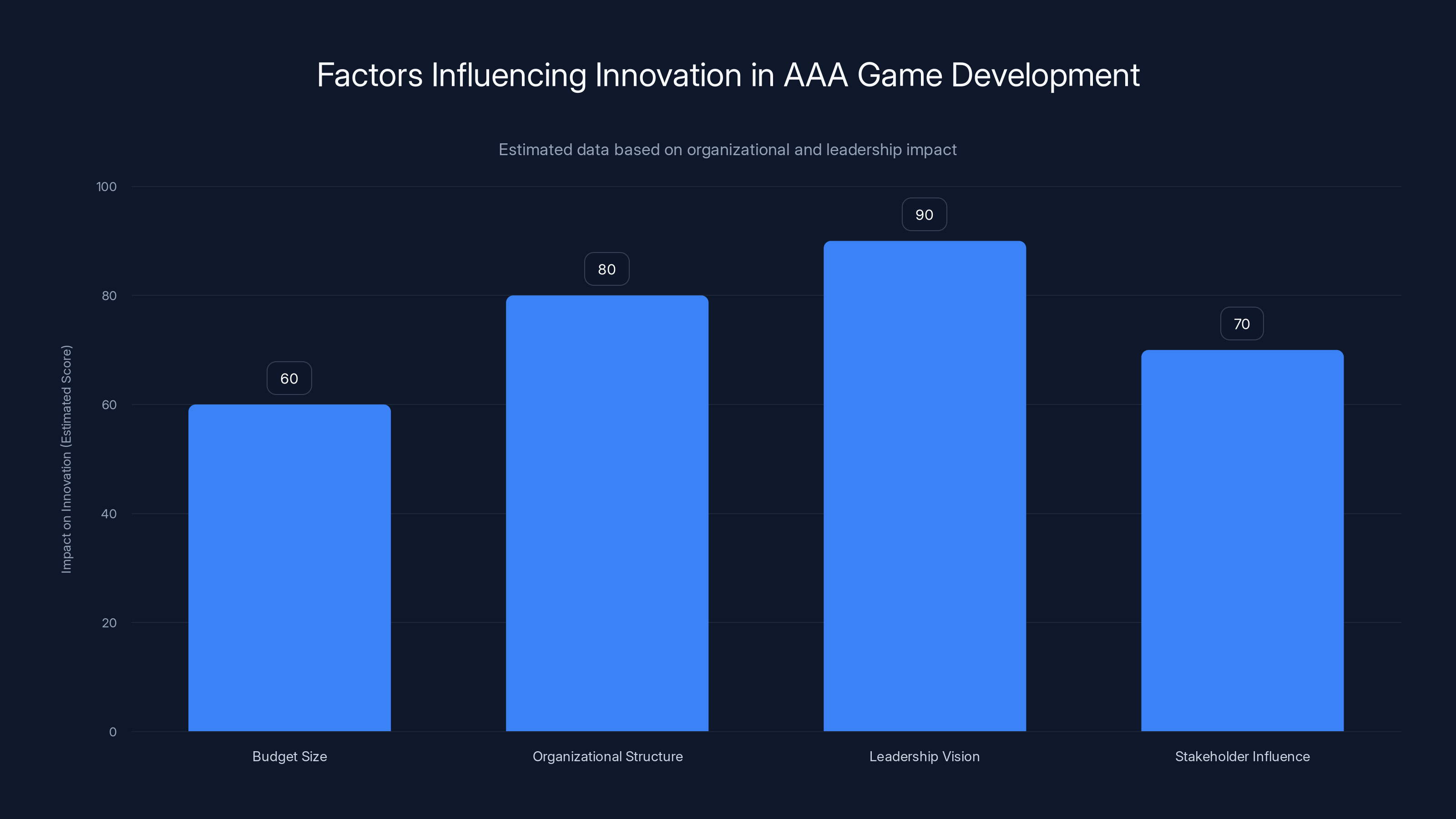

Leadership vision and organizational structure have a higher estimated impact on innovation in AAA game development than budget size alone. Estimated data.

Lessons for Aspiring Game Developers and Studios

Fares' perspective offers practical lessons for anyone working in game development.

First: innovation at any scale requires sufficient resources. You can't innovate while the budget runs out. You need enough money to polish your vision and iterate toward it.

Second: innovation requires vision. You need clarity about what you're trying to accomplish and why it matters. This is harder in committee structures but possible with strong creative leadership.

Third: innovation risks failure. Not every experimental idea works. You need organizational structures that can absorb failure without killing the entire project.

Fourth: different types of innovation look different. The mechanical innovation of a small indie game and the scale innovation of a massive AAA title are both innovation, just differently oriented.

Fifth: market success isn't guaranteed for innovation. But lack of innovation almost guarantees mediocrity. You're better off risking failure on something bold than succeeding incrementally on something safe.

Fares has applied these lessons across three successful games. It's made him one of the few AAA developers willing to publicly argue for more innovation. His voice matters because he's actually doing the thing he's arguing for.

The Role of Artistic Vision in Large-Scale Projects

What unites Nintendo, Rockstar, and Naughty Dog is strong artistic vision. Each studio has clear ideas about what games should be, and they're willing to pursue those ideas even when they're unconventional.

This is harder than it sounds. Artistic vision requires confidence in your ideas. It requires willingness to ignore conventional wisdom. It requires patience to pursue something nobody has asked for.

In large organizations, this requires protection. You need leadership that shields creative teams from market pressure and committee decisions. You need structures that permit "no" when compromises would dilute the vision.

Nintendo's president Shigeru Miyamoto is famous for simplifying game concepts and removing features that don't serve the core vision. Rockstar's creative leadership has fought for artistic direction even when publishers pushed for different choices. Naughty Dog's leadership has maintained consistent creative philosophy across decades.

This isn't about being difficult or refusing feedback. It's about maintaining clarity of purpose while incorporating critique. It's about having strong enough vision that compromises are chosen for good reasons, not default reasons.

Fares embodies this in his work. It Takes Two's focus on co-op as core mechanic wasn't something audiences asked for. It was something Fares believed mattered. Split Fiction's focus on romance and relationship in co-op gameplay was similarly not market-driven. It was artistically motivated.

When artistic vision succeeds commercially, it validates the approach. This encourages more studios to take similar risks. This is how industry culture shifts.

What the Future Might Hold for AAA Innovation

If Fares is right, and the evidence suggests he is, then AAA game development might see more innovation going forward.

Market signals matter. Every successful innovative AAA game makes the next one slightly less risky. Split Fiction's success shows that audiences engage with relationship-focused co-op games. Breath of the Wild's success showed that open-world design could work without traditional quest systems. These prove that innovation sells.

Generational change matters too. Developers coming into the industry now have grown up with independent games and understand different design philosophies. They might bring that sensibility into AAA studios and advocate for different approaches.

Technological change creates opportunity. New engines, new tools, and new capabilities enable kinds of innovation that weren't possible before. But tools alone don't drive innovation—vision does. Tools enable vision.

Cultural conversation matters. When industry figures like Fares publicly argue for AAA innovation, it shifts what's considered normal. It becomes easier to propose innovative projects when the culture supports it.

None of this is inevitable. The industry could continue following patterns of franchises and sequels. But the possibility space has expanded. Innovation at AAA scale is demonstrated to be possible. More studios could choose to pursue it.

Addressing the Skeptics: Why the Stagnation Narrative Persists

Despite evidence that AAA innovation exists, many believe the narrative that AAA games have become creatively exhausted. Why?

Partly because the innovation often happens in games you don't notice. When a game succeeds commercially, we attribute success to known factors: franchise recognition, marketing, genre appeal. When innovation succeeds, we might not recognize that innovation as the reason for success.

Partly because the failures are visible. When AAA studios try to innovate and fail commercially, everyone hears about it. When innovation succeeds, it's sometimes attributed to other factors.

Partly because indie games are more visible to certain audiences. Gaming discourse often emphasizes indie innovation more prominently than AAA innovation, creating perception bias.

Partly because the sheer volume of safe AAA games overwhelms the innovative ones. When 90% of AAA releases are franchise entries or proven mechanics, the 10% that innovate can seem like exceptions rather than evidence of a trend.

Fares' argument pushes back on this perception. He's saying: look more carefully. Innovation is happening at AAA scale. You might not notice it because you're looking for one specific type of innovation.

The Distinction Between Innovation Types

It's worth being specific about what innovation means, because it's contested.

Mechanical innovation: New game mechanics and systems (examples: Breath of the Wild's physics-based puzzle-solving, Hades' roguelike structure).

Narrative innovation: New approaches to storytelling (examples: Naughty Dog's cinematic integration, Disco Elysium's skill-based dialogue).

Artistic innovation: New visual or audio approaches (examples: Celeste's pixel art, Journey's audio design).

Scale innovation: Doing things at scale nobody has attempted (examples: Red Dead Redemption 2's world simulation, Cyberpunk 2077's cityscape density).

Technological innovation: Pushing technical boundaries (examples: using new engine capabilities, creating new tools for development).

Design innovation: New approaches to how games structure player experience (examples: Fortnite's live service evolution, Among Us's social deduction integration).

When people say AAA games aren't innovative, they often mean mechanical innovation specifically. That's a fair observation—most AAA games use proven mechanical frameworks. But by other measures, AAA games are consistently innovative.

Fares' argument accommodates this complexity. He's not claiming all AAA games are innovative across all dimensions. He's claiming that AAA budgets enable certain types of innovation that would be impossible at smaller scales, and studios that commit to innovation can achieve it.

This nuance matters because it focuses discussion on real tradeoffs. What types of innovation matter to you? What types do you want to see more of? Are there budget and organizational structures that better serve your preferred innovation types? These are useful questions.

Connecting Back to Hazelight's Philosophy

Understanding Fares' argument makes Hazelight's game design philosophy clearer. It Takes Two and Split Fiction both demonstrate intentional choices about what to prioritize.

They're not pursuing mechanical innovation through new systems. They're pursuing design and narrative innovation through genre-bending storytelling integrated with co-op gameplay. This requires sufficient budget to iterate on relationship mechanics and narrative integration.

They're not pursuing scale innovation. They're not building massive worlds. They're pursuing depth in more focused experiences.

They're pursuing the types of innovation that match their studio's strengths and vision. That's the practical application of Fares' argument. Don't try to innovate in every direction. Choose where you want to push boundaries and commit resources to that.

This approach seems to work. Both games found audiences, received critical acclaim, and succeeded commercially. This validates that you don't need massive budgets to innovate—you need sufficient budgets and clear vision about where you're innovating.

The Broader Industry Implications

If more studios followed Fares' approach, AAA development might look different.

We might see fewer franchises and more IP exploration. We might see more mid-tier games with distinctive vision. We might see studios choosing depth in specific areas rather than competence across all areas.

We might see different publishing structures. Publishers might fund more experimental projects alongside safe franchise entries. This is already happening at studios like Double Fine (now part of Xbox Game Pass strategy) and at Nintendo, which funds both experimental projects and franchise entries.

We might see longer development cycles for ambitious projects, shorter cycles for proven mechanics. Development time would match design ambition rather than publisher deadlines.

We might see more collaboration across studios. If innovation is harder in isolation, sharing resources, ideas, and talent could improve outcomes.

None of this is guaranteed. But Fares' argument opens space for these possibilities by claiming innovation is possible at AAA scale and demonstrating it in his own work.

Conclusion: The Case for Continued AAA Innovation

Josef Fares makes a simple but powerful argument: AAA budgets don't prevent innovation. They enable different types of innovation. The constraint isn't financial—it's organizational and cultural.

When studios like Naughty Dog, Nintendo, and Rockstar choose to innovate, they do so at scales that smaller studios couldn't achieve. Their innovation looks different, but it's no less genuine. These studios prove the possibility.

Fares' position is that more studios could make similar choices. More could prioritize vision over risk-minimization. More could use AAA budgets to push boundaries rather than refine proven mechanics.

This requires specific choices: clear creative leadership, sufficient time for iteration, organizational structures that permit artistic risk, and publisher support that understands innovation requires acceptance of failure.

These conditions aren't available everywhere. But they're available somewhere, and what's available somewhere can become available elsewhere through deliberate choice.

The gaming industry's future might not look like either exclusive futures proposed by pessimists (AAA stagnation) or optimists (AAA continues dominating). It might look like an industry with multiple innovation paths: indie games innovating through constraint, AA games innovating through focused vision, and AAA games innovating through scale and resources.

All three types of innovation can coexist. The question is whether enough studios choose to pursue it.

Fares is arguing they should. His work demonstrates they can. Whether the industry listens might determine what games look like five years from now.

TL; DR

- AAA budgets enable innovation: Fares argues that studios like Naughty Dog, Nintendo, and Rockstar consistently push boundaries using AAA budgets, proving that size doesn't prevent creativity.

- **The 100 million, risk-aversion increases psychologically, but it's surmountable through strong leadership and clear vision.

- Different studios innovate differently: Naughty Dog pursues narrative and animation innovation, Rockstar pursues systems and scale innovation, Nintendo pursues mechanical design innovation—all genuine, all requiring AAA resources.

- Organizational structure shapes possibility: The constraint on innovation isn't money, it's organizational choice—whether studios prioritize artistic vision over risk-minimization and whether publishers support that priority.

- Market success validates risk-taking: Games like Split Fiction prove that innovative AAA titles find audiences and succeed commercially, encouraging more studios to take similar risks.

FAQ

What does Josef Fares mean by AAA innovation?

Fares argues that games with large budgets and major publishers can still pursue genuine creative risks and push artistic boundaries. He specifically points to studios like Naughty Dog, Nintendo, and Rockstar as examples of AAA developers who innovate rather than simply refining proven formulas. His claim is that innovation at AAA scale looks different than indie innovation, but it's equally valid.

Why does budget size affect innovation differently in AAA games?

Larger budgets create more complex organizational structures, more stakeholders involved in decisions, and higher financial risk if projects fail. This naturally encourages conservative design choices. However, Fares argues that studios with clear creative vision and leadership willing to protect innovation can overcome this. The psychological shift happens around $100 million in budget—beyond that threshold, people become more cautious with spending, but it's not an inevitable constraint.

How do Naughty Dog, Rockstar, and Nintendo innovate within AAA budgets?

Naughty Dog focuses on narrative, animation fidelity, and character development, investing heavily in motion capture and accessibility features. Rockstar pursues world simulation and emergent systems that create unique moments for every player. Nintendo emphasizes mechanical design and finding new ways to use established franchises (Breath of the Wild's open-world redesign, Super Mario Bros. Wonder's new power systems). Each pursues different innovation types, but all require substantial resources.

What's the difference between AAA and indie game innovation?

Indie games innovate through constraint—limited budgets force creativity in design, art direction, and concept. AAA games can innovate through scale—building massive worlds, pursuing technical depth, or creating simulation systems that aren't possible with smaller teams. Both are legitimate innovation paths, just oriented differently. Indie innovation is usually conceptual or mechanical; AAA innovation is often systemic or scale-based.

Is Split Fiction an example of successful AAA innovation?

Yes. Split Fiction demonstrates Fares' philosophy in practice. The game innovates in narrative (romance-focused storytelling) and design (co-op mechanics integrated with story), sold over 1 million copies in its first month, and received critical acclaim. It operates with a AAA budget sufficient to realize its vision but isn't an ultra-expensive blockbuster like $150+ million titles. It proves that audiences respond to innovative AAA games.

What organizational factors enable AAA innovation?

Innovation in AAA development requires: clear creative vision from leadership, sufficient time for iteration and experimentation, organizational autonomy in decision-making, technical resources to solve hard problems, and publisher support willing to accept risk and potential failure. Studios that lack these conditions tend toward safer design. These are choices studios and publishers can make, not inevitable constraints of large-scale development.

Why do people think AAA games are less innovative than indie games?

Partially because indie innovation is more visible to certain audiences, partially because the volume of safe AAA games (franchises, sequels, proven mechanics) overwhelms the innovative ones, and partially because innovation succeeds quietly while failures are discussed loudly. Additionally, innovation types differ—indie games' mechanical innovation is more noticeable to players than AAA games' scale or systems innovation. Fares' argument asks people to look more carefully at what AAA studios actually accomplish.

Will AI change how AAA innovation happens?

Fares is skeptical of narratives about AI "taking over" game development. AI will likely become a tool for handling specific tasks (asset generation, quality assurance, etc.), but innovation still requires vision—understanding what game experience you want to create and why it matters. AI is good at execution but not at artistic direction. Games using AI will still be shaped by human creative choices about what those games should be.

What can game studios do to enable more innovation?

Studios can make structural choices: protect creative leadership from excessive committee oversight, allocate sufficient time for iteration, fund diverse projects (both safe franchises and experimental titles), and maintain organizational autonomy from publisher pressure for quick returns. Publishers can support risk-taking by understanding that innovation sometimes fails and that failure is acceptable cost of growth. Industry culture can shift by celebrating and discussing AAA innovation seriously rather than dismissing it.

Does AAA innovation require massive budgets?

No. Fares himself runs Hazelight Studios on budgets substantially smaller than true AAA blockbusters. What matters is sufficient budget to realize creative vision—sometimes that's

Key Takeaways

- AAA budgets enable scale and artistic innovation that indie studios cannot achieve, including massive world simulation, sophisticated animation systems, and mechanical depth across 60+ hour experiences

- The real constraint on AAA innovation is organizational and psychological, not financial—studios that maintain creative autonomy and leadership vision can innovate even with $100M+ budgets

- Naughty Dog, Rockstar, and Nintendo demonstrate different innovation models: narrative/artistic, systems/simulation, and mechanical design respectively, all requiring AAA resources

- Josef Fares proves this philosophy works commercially with Split Fiction's success: over 1 million sales in month one and critical acclaim, using moderate AAA budgets for genuine creative risk

- Future AAA innovation depends on industry culture shifts and market signals validating risk-taking—studios choosing artistic vision over risk-minimization, and publishers supporting that choice

![Josef Fares on AAA Innovation: How Big Budgets Still Push Gaming Forward [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/josef-fares-on-aaa-innovation-how-big-budgets-still-push-gam/image-1-1768390720236.jpg)