The Great AI Divide in Game Development

Last year, something unusual happened in the gaming industry. A CEO mentioned his studio was experimenting with AI tools, and the internet reacted strongly. Not because he was using AI to build the entire game—he wasn't. But because admitting to any AI usage at all became a controversial topic that developers couldn't touch without facing significant backlash.

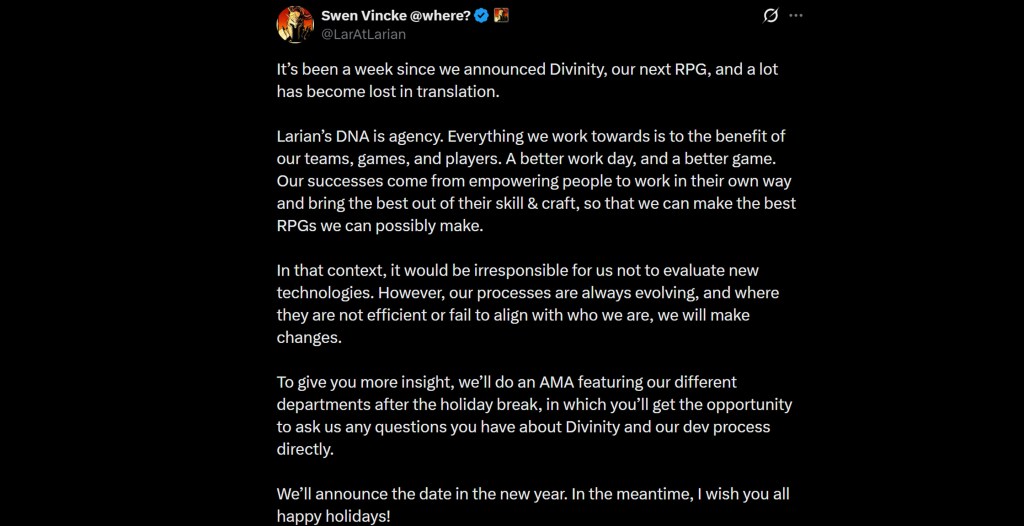

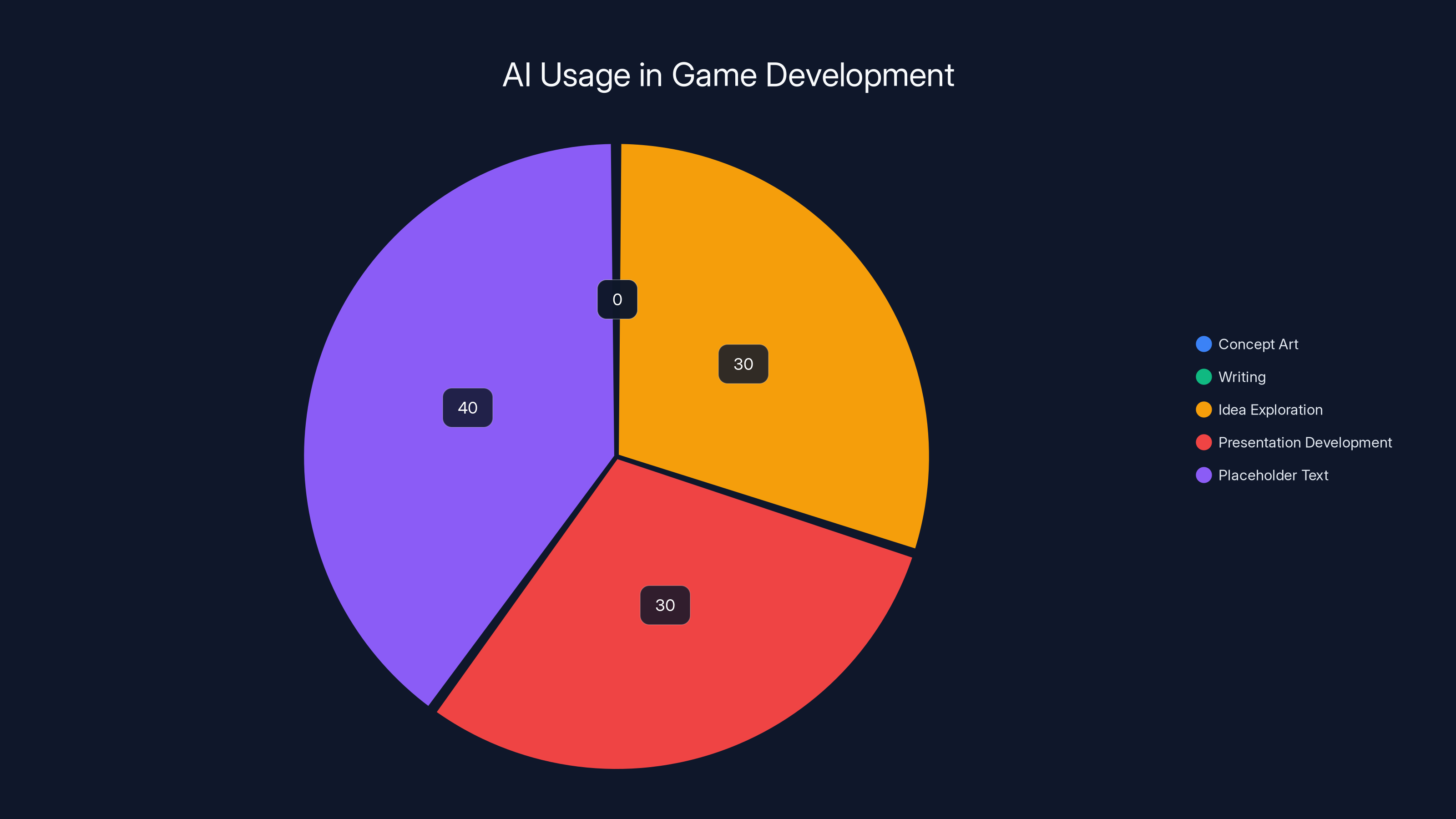

Swen Vincke, CEO of Larian Studios, made comments about using generative AI to "explore ideas, flesh out Power Point presentations, develop concept art and write placeholder text." The backlash was immediate and fierce. Game developers, artists, and fans took to social media platforms with a unified message: don't use AI in our beloved games.

Instead of backing away quietly, Larian engaged with the criticism. They clarified their stance, made specific commitments, and held a Reddit AMA to explain their position on generative AI.

The result? A studio making a deliberate choice to exclude AI from two critical parts of game development: concept art and writing. They're not demonizing AI or claiming it has no place anywhere. They're drawing a line. This line is significant because it reflects how the industry is currently thinking about this technology, rather than the hype often seen in headlines.

Understanding Larian's position requires understanding the stakes. This isn't about whether AI is good or bad in an abstract sense. It's about what happens when you use it in ways that undermine the core craft of game development. Outsourcing the thinking to a machine results in a loss of something essential. That's not romantic nonsense; it's a legitimate technical and artistic concern.

The gaming industry is at an inflection point. Major studios are experimenting with AI, while indies use it to stretch thin budgets. However, players have drawn a clear line in the sand: they don't want outsourced creativity for the parts that matter. Concept art and writing aren't just decoration; they're the foundation that everything else is built on. If those foundations come from a language model, it shows.

Larian's decision is pragmatic. They tested AI tools, measured them against their standards, and concluded that AI wasn't helping them make better games in these critical areas. That's the opposite of dogmatism; it's engineering.

What Larian Actually Said About AI

The details matter, so let's walk through what happened and what Larian communicated.

First, the initial controversy. In an interview with Bloomberg, Vincke mentioned that the team was experimenting with AI "to explore ideas, flesh out Power Point presentations, develop concept art and write placeholder text." The mention of developing concept art with AI became the catalyst for backlash. To many in the gaming and art communities, it sounded like "replacing artists with robots."

The pushback was swift. Game developers took to Twitter and Reddit, arguing this was how the decline of creative industries starts. Artists emphasized that concept art is the soul of game development and can't be automated. Former Larian employees supported the criticism. The pressure was real.

Vincke responded with a clarification, stating they were using AI "as something artists could use to iterate on ideas faster." This distinction is crucial. He wasn't saying "we're replacing concept artists," but rather "we're giving artists a tool to move faster." These are genuinely different things, but the messaging got tangled.

During the Reddit AMA, Vincke made it clear: "So first off - there is not going to be any Gen AI art in Divinity." That's unambiguous. Not "we're exploring the possibility," but a clear statement of current intent.

He further stated: "We've decided to refrain from using gen AI tools during concept art development. That way there can be no discussion about the origin of the art." This sentence is crucial. He's not saying AI-generated art is inherently bad; he's saying that the discussion about where the art came from is a problem they don't want to have. It creates doubt, so rather than navigate that minefield, they're avoiding it.

Vincke left a caveat: "If we use a Gen AI model to create in-game assets, then it'll be trained on data we own." Translation: they're not closing the door on AI entirely. They're saying it won't be used for the creative foundation (concept art), but down the road, maybe for in-game assets, maybe with proprietary models. This is a more nuanced position than "no AI ever," but it's also more realistic about where the technology might eventually fit.

On the writing side, writing director Adam Smith was equally clear. "We don't have any text generation touching our dialogues, journal entries or other writing in Divinity." That's the same hard line. No AI text in the final product.

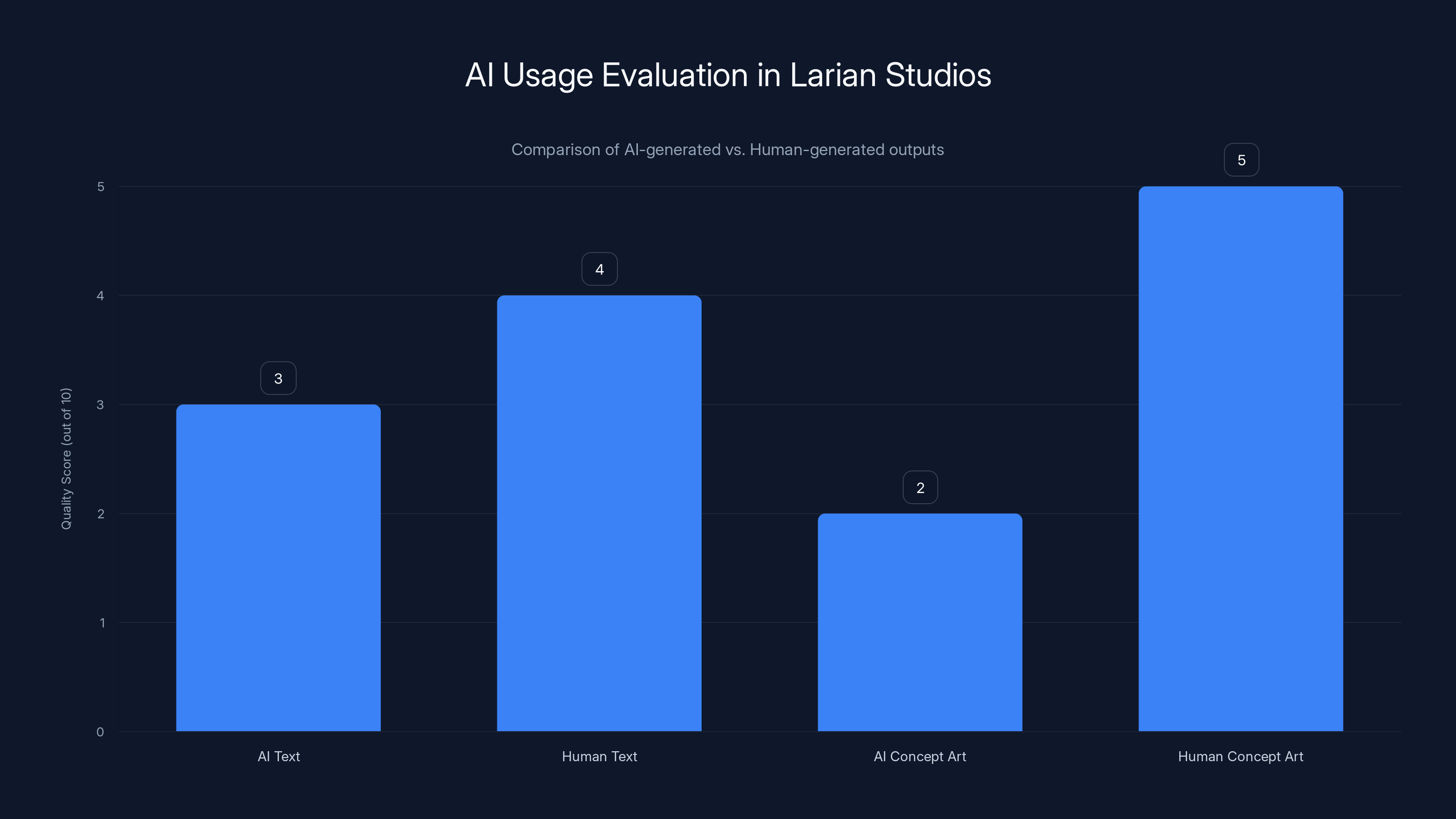

Smith also shared insights about their experimentation. He said a small group tested text generation tools, and the results were "3/10 at best." He compared that to his own first drafts, which are "at least a 4/10." The gap between even rough human writing and the output of these tools was massive, and the iteration required to get individual lines to acceptable quality was prohibitive.

This is data. This is what they learned from actual experimentation. It's not ideology; it's engineering. They tried it, and it didn't work well enough to justify the effort, so they stopped.

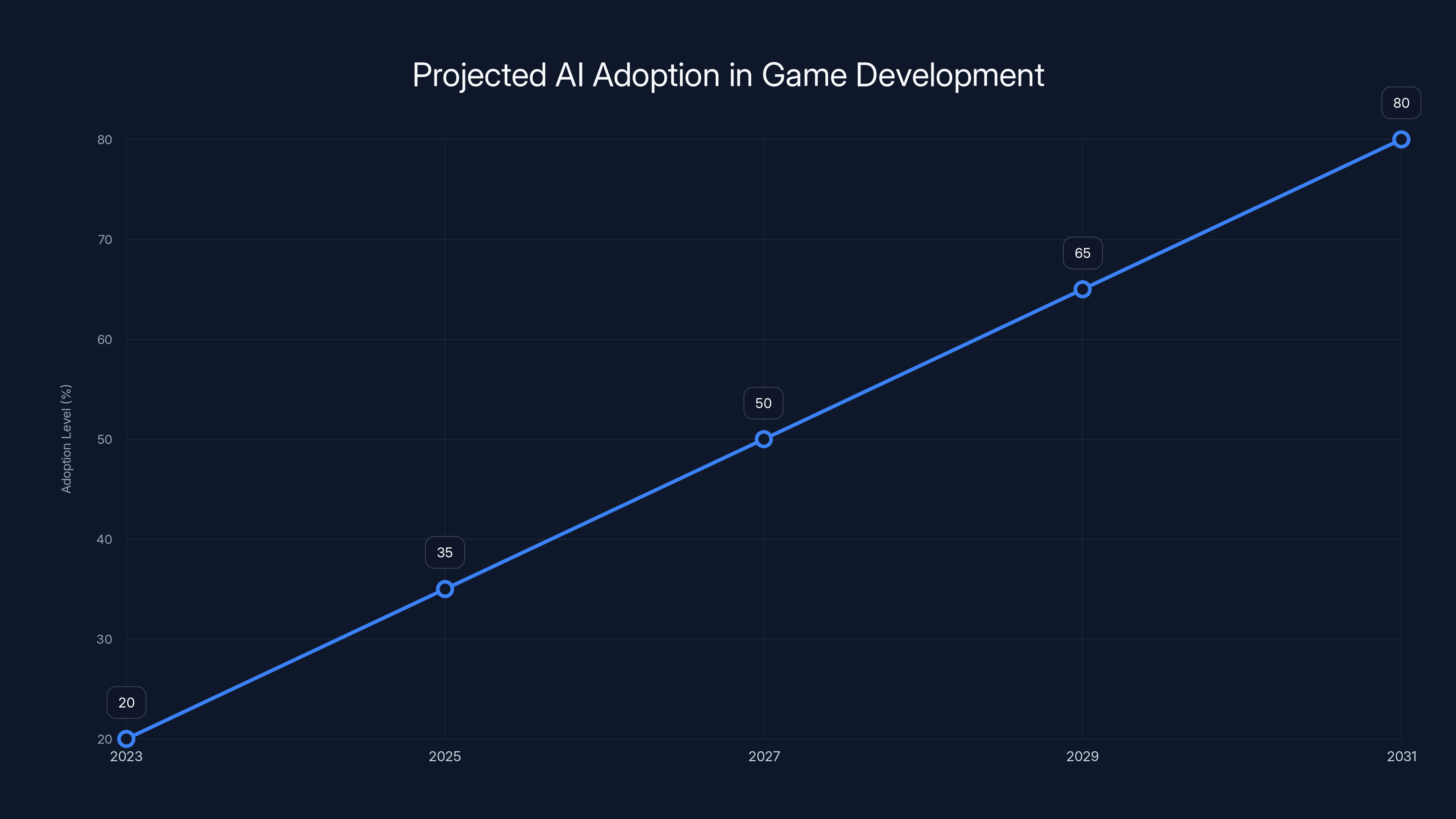

Estimated data suggests a gradual increase in AI adoption in game development, particularly in non-creative roles, over the next decade.

The Artist and Writer Perspective

To understand why this decision resonates so strongly, you need to understand what concept artists and writers actually do in game development.

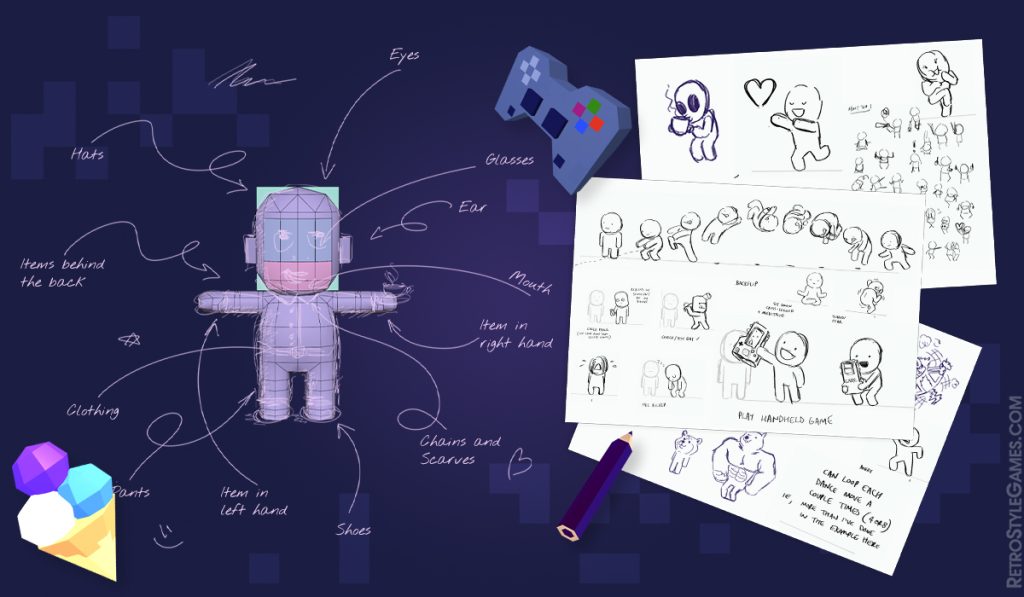

Concept art is where games are born. Before a single 3D model exists, before programmers write a line of code, artists are drawing. They're drawing characters, environments, props, UI elements, lighting moods, color palettes. Everything. Every visual decision gets made in concept first. This art becomes the blueprint that every other department follows.

A concept artist's job isn't just to make pretty pictures. It's to solve problems. A character needs to look intimidating but not cartoonish. An environment needs to feel ancient but not unnavigable. A weapon needs to be recognizable at distance but detailed up close. These are design problems that require human judgment, iteration, and problem-solving.

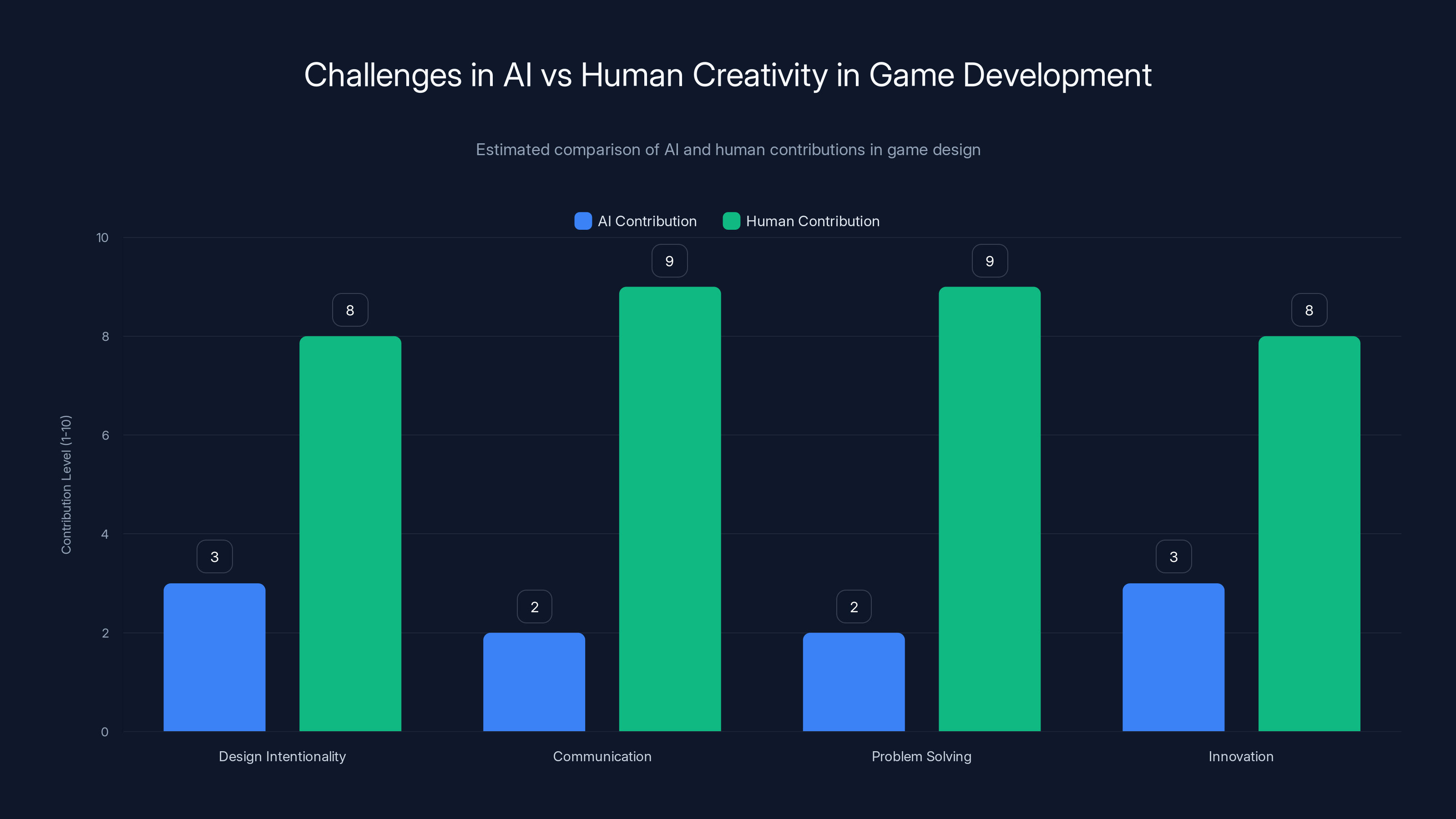

When you hand these problems to an AI, a few things happen. First, you lose the design intentionality. The AI generates something that looks okay, but doesn't solve the specific problems you're trying to solve. It's derivative, not innovative. Second, you lose the communication layer. When an artist sketches something quickly, they're communicating their thinking to the team. That process of externalization and feedback is how ideas get refined. Third, you lose the constraint-based problem solving that makes design interesting.

Now, could an AI-generated sketch be a starting point that a human artist then refines? Theoretically, sure. But in practice, it's usually faster to just start from scratch than to take something generated and fix it. And psychologically, starting from an AI output carries baggage. You're not ideating. You're correcting. That's a fundamentally different creative process.

For writers, it's a different but equally valid problem. Game writing isn't just dialogue. It's branching narrative, environmental storytelling, UI text, journal entries, item descriptions, NPC flavor text. All of this needs to:

- Match the established tone and voice of the game

- Feel authentic to the world and character

- Fit technical constraints (line length, localization issues, etc.)

- Work with the game systems and mechanics

- Surprise players and reward exploration

AI language models are trained to generate plausible-sounding text. But "plausible" is not the same as "good." Adam Smith's point about the 3/10 quality is spot on. An AI will generate something that's grammatically correct and reads like English, but it won't nail the voice. It won't make players laugh or feel something. It won't reward exploration with a clever reference or unexpected depth.

The temptation is always to say "well, we'll just use AI for the filler text—item descriptions, minor NPC dialogue, placeholder stuff." But here's the trap: if you let AI write the filler, you've just given your game 30% of its dialogue without the same care and intentionality you'd apply to the main story. And in games, it's often the filler that makes the world feel alive. A throwaway NPC line can be the moment that makes a player love the game. You can't automate that.

Larian's writers faced this exact pressure. Could they have used AI to generate minor NPC flavor text and saved time? Almost certainly. But Smith's willingness to admit that even his first drafts are better than AI output shows the bar they're holding.

The artist and writer communities took Larian's decision as a validation of their concerns. It's not that technology can't help. It's that the help needs to be in the right places. In iteration speed, in exploration, in brainstorming. Not in replacing the core thinking and feeling that makes art and writing human.

Larian Studios found AI-generated text scored 3/10, below human drafts at 4/10. AI concept art was rated 2/10, while human art scored 5/10. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Technology They're Actually Using

Here's something important that often gets lost: Larian said they're NOT using AI for concept art or writing, but they ARE still experimenting with AI. They didn't say "we hate AI" or "AI has no place in games." They said "we're being specific about where and how we use it."

Vincke said they hope AI "can aid us to refine ideas faster, leading to a more focused development cycle, less waste, and ultimately, a higher-quality game." That's not anti-AI. That's pro-intentionality. They're looking for places where AI actually saves time without compromising quality.

So where might that be? Larian mentioned Power Point presentations. That's actually a good example. If your studio is using AI to generate slides for internal presentations—prototyping ideas, showing progress, explaining systems to the team—that's a legitimate time-saver. Nobody's art is being outsourced. You're just using a tool to speed up communication.

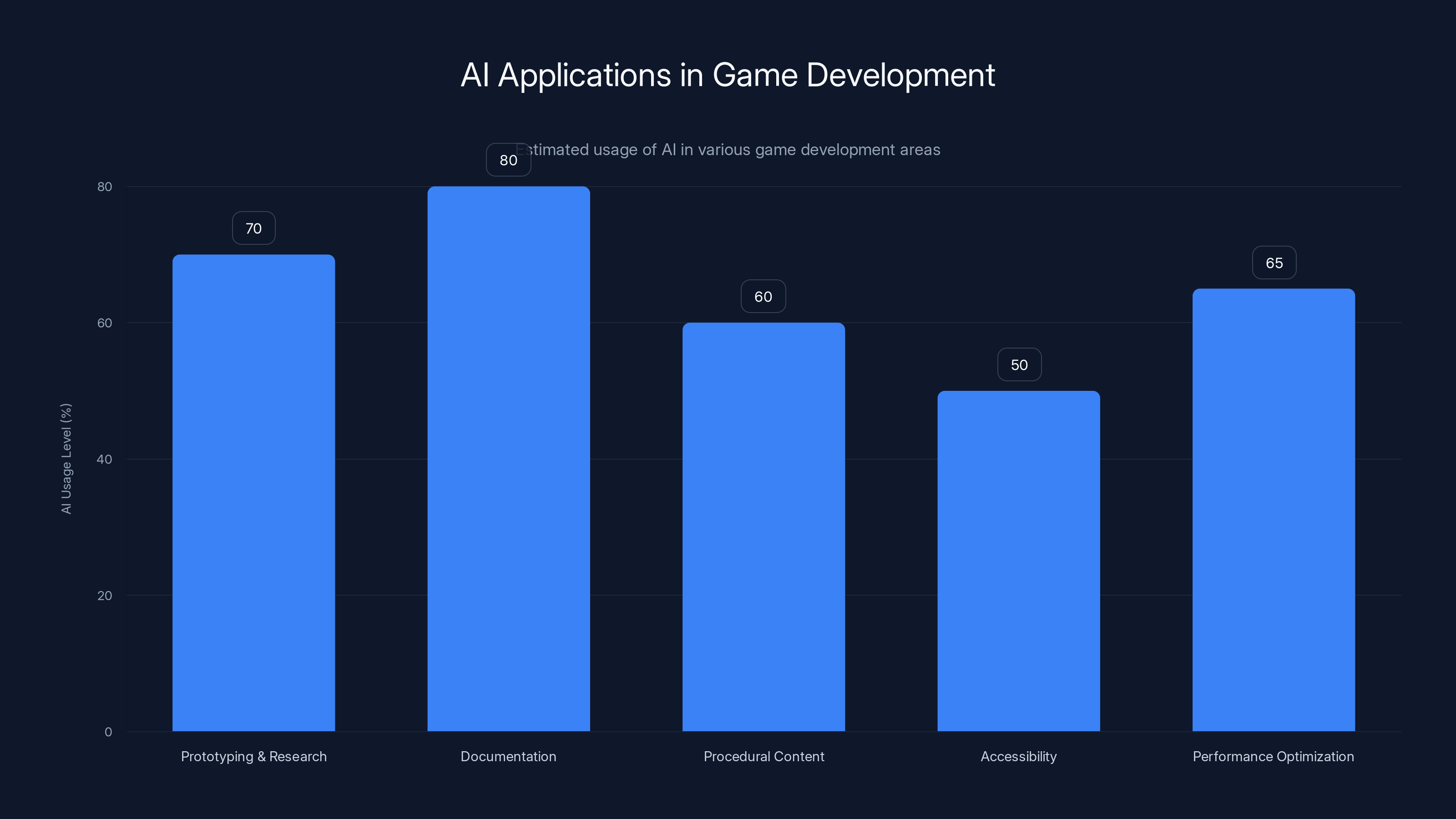

Other places where game studios legitimately use AI without controversy:

Prototyping and Research: AI tools can help designers quickly test ideas and feasibility. "What if we made this mechanic work this way?" You can prototype faster.

Documentation: Generating technical documentation, design docs, meeting transcripts. This is valuable work, but it's not creative. AI can handle it.

Procedural Content Generation: This is a gray area, but it's different from concept art. Using AI to help generate variations of terrain, vegetation, or other systematic elements is different from having AI design your main character.

Accessibility Features: AI can help generate captions, audio descriptions, or other accessibility enhancements. That's genuinely valuable and doesn't replace human creativity.

Performance Optimization: AI tools can help analyze performance data and suggest optimizations. That's engineering support, not creative replacement.

The key variable in all of these is: does using AI here actually save time without compromising the quality that matters? Larian's decision to exclude concept art and writing suggests they've tested it in enough places to know where the answer is "yes" and where it's "no."

Why This Matters for Game Quality

Let's be direct: this decision exists because of game quality. That's the actual bottom line.

When you use generative AI for concept art, you're not just replacing an artist. You're changing the design process in ways that make it harder to create coherent, intentional design. Concept art isn't the final product. It's the thinking made visible. If the thinking comes from a machine, the downstream design suffers.

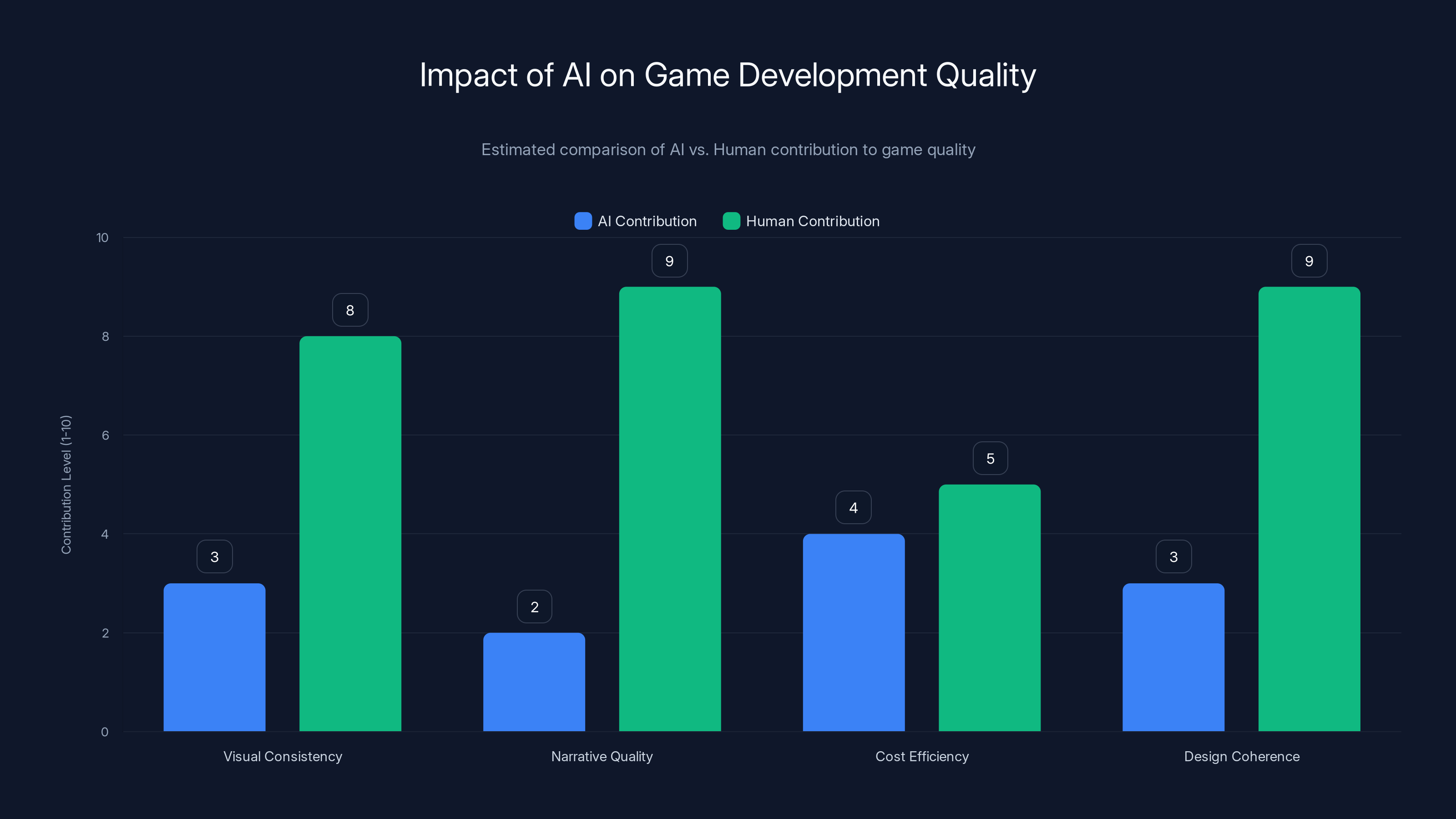

In Baldur's Gate 3 specifically, the visual consistency of the game is extraordinary. Every character feels like they belong in that world. Every environment tells a story. This isn't accident. It's because the concept art was created by people who understood the vision and could execute it with intention. That kind of coherence is almost impossible to achieve if you're patchworking AI-generated pieces together.

The same applies to writing. Baldur's Gate 3's writing is often cited as a benchmark for game narrative quality. The dialogue is sharp. The characters have voice. The story branches feel meaningful. This comes from writers who deeply understand the world and have refined their craft. That's not something AI currently does well. It generates competent text. It doesn't generate surprising, delightful, moving text.

Here's the economic argument: using AI for these parts doesn't save money in the long run. It looks like it does on paper. "Use AI to generate concept art, save X artist-hours." But in practice, you're just moving the cost downstream. You'll need more concept refinement. You'll need more iteration. You'll need more cleanup. By the time you factor in all of that, you might break even—and you've compromised quality in the process.

Larian's position suggests they've done the math and concluded that the traditional approach actually works better. Hire good artists and writers. Let them do their job. Use AI only where it genuinely accelerates work without introducing more problems than it solves.

This has implications for the entire industry. If Baldur's Gate 3 ships with fantastic art and writing, and the studio publicly committed to not using AI for those elements, then other studios will take note. Not because AI is bad, but because the results matter. Quality sells games. Compromised vision doesn't.

Human artists and writers significantly outperform AI in design intentionality, communication, and problem-solving, highlighting the importance of human creativity in game development. Estimated data.

The Backlash and Why It Happened

When Vincke first mentioned AI in the Bloomberg interview, the response was visceral. Let's understand why that happened and what it reveals about how people in the gaming community think about AI.

There are a few layers to the backlash. The first is pure anxiety. AI is here, it's capable of doing creative work, and creators are rightfully worried about what that means for their careers. A concept artist looks at AI art generation and thinks about job security. That's not irrational. That's a real concern.

The second layer is about authenticity and craftsmanship. Games are made by people. When you play Baldur's Gate 3, you're experiencing the result of hundreds of humans thinking, creating, and collaborating. There's something meaningful about that. Using AI to shortcut that process feels like it cheapens it. Not in a snobby way, but in a real way. The care shows. Audiences can feel when something was made with intention.

The third layer is about the specific framing. When Vincke said they were using AI to "develop concept art," the word "develop" triggered people. In creative industries, "developing" art means making fundamental design choices. That's different from "iterating on a concept sketch" or "exploring variations." The word choice made it sound like AI was doing the thinking, not just providing tools.

Final layer: precedent. In other industries, AI adoption has often meant job losses and quality reduction. Writers saw what happened with content mills and AI-generated articles. Musicians saw AI voice synthesis. Artists saw AI art generators. In each case, the corporate response was to use it to reduce costs, not to enhance human creativity. So when a game studio mentioned AI, people's instinct was based on real historical precedent.

The backlash wasn't irrational. It was informed by legitimate concerns about how technology gets used in creative industries. That context matters. When Larian responded with specificity and commitment, people respected it. Not because AI is suddenly good, but because the studio demonstrated they were thinking about craft, not just efficiency.

Practical Implementation: How Larian Drew the Line

Drawing a clear line on AI usage requires more specificity than most studios have managed. Let's walk through how Larian actually did it.

First, they identified the critical creative areas: concept art and writing. These are the foundation. Everything else in the game is built on these decisions. You can't compromise here without compromising the whole game.

Second, they made that commitment public and specific. Not "we're thoughtful about AI" (vague, meaningless). But "no Gen AI art in Divinity" and "no text generation in our dialogues." You can measure this. You can hold them accountable.

Third, they left room for evolution. Vincke didn't say "AI will never be used in any part of game development." He said they're not using it for these parts now, and if they use it for assets, it'll be trained on proprietary data. This prevents the commitment from becoming an obstacle to better tools in the future.

Fourth, they explained the rationale. Smith's comment about the 3/10 quality is important because it's not ideological. It's pragmatic. They tested it. It didn't work well enough. So they stopped. That's the kind of reasoning that holds up over time.

For other studios trying to navigate AI, this model works:

-

Identify your critical creative areas. What parts of your game would be worse if outsourced? Those are off-limits.

-

Test everything else rigorously. Don't assume AI won't help. But measure the actual time savings and quality impact.

-

Be transparent about your decisions. Players will respect clarity. They'll be skeptical of vagueness.

-

Measure against your actual standards. Not industry standards or marketing promises. Your standards. Larian's standard for writing is "at least a 4/10" even on first drafts. If AI can't meet that, it doesn't matter how fast it is.

-

Make decisions based on craft, not cost. The money argument for AI is always there. But if the end product suffers, you've lost the plot.

AI is widely used in documentation and prototyping, with moderate use in procedural content generation and performance optimization. Estimated data.

The Broader Industry Implications

Larian's stance matters beyond Baldur's Gate 3. It signals something important to the rest of the gaming industry about where this technology actually fits.

Right now, there's a gold-rush mentality around AI in gaming. Publishers are hungry to cut costs. Studios are under pressure to do more with less. The pitch is always the same: "AI can handle the grunt work, free up your human creators for the high-level stuff." But Larian's experience suggests that the "grunt work" is often essential to the overall vision.

If Baldur's Gate 3 ships and critics rave about how the art and writing are exceptional, and the industry knows that Larian excluded AI from those areas, it creates a reputation advantage. Quality becomes a selling point. And other studios will follow because players care about it.

Conversely, if other studios start shipping games with AI-generated concept art and writing, and those games feel incoherent or soulless, the backlash will be severe. Players will explicitly call out that the game feels like it was designed by algorithm. That's a reputational disaster.

The financial incentives for AI are real. But so are the quality incentives. Larian's decision suggests they believe quality will win the day. And looking at their track record with Baldur's Gate 3, they have credibility to make that argument.

There's also a talent acquisition angle. Top concept artists and writers can choose where they work. If you're publicly committed to not outsourcing to AI, you're more attractive to human talent. If you're using AI to replace artists, you'll struggle to hire the best people. Larian is positioning themselves as the studio that respects craft.

For indie developers, this is complicated. They don't have the resources of AAA studios. Using AI to stretch budgets is tempting. But Larian's approach suggests that if you're going to use AI, use it in places where it genuinely helps without undermining your core vision. Don't use it to replace the thinking. Use it to speed up the thinking.

The Future of AI in Game Development

Larian's decision isn't a "no AI forever" statement. It's a "not yet, and maybe not in these ways" statement. What does that imply about the future?

AI will likely become more useful in game development over time. Better models, trained on better data, with more nuance and control. But even as capabilities improve, the fundamental problem remains: output that's generated doesn't carry the same intentionality as output that's designed.

One interesting scenario is proprietary AI models trained on a studio's own work. If Larian trained an AI model on all their concept art, could that model be useful for creating variations or exploring directions? Maybe. That's different from using public AI art models. It would be in the style of that studio, informed by that studio's aesthetic. That might actually be valuable.

Another scenario is AI as a starting point for human iteration. Not "use AI to generate concept art," but "use AI to generate 100 rough thumbnails, and humans pick the best 10 and refine them." That's a workflow that could work if the AI output is good enough to be useful.

But the most likely scenario is that AI finds its place in game development in the places it already is: tools for programmers, documentation generators, optimization assistants, accessibility features. The creative core—art and writing—remains human for quite a while. Maybe forever.

Vincke's comment about proprietary AI models is forward-thinking. As AI gets more capable and studios build proprietary models, the calculus might change. But that's years away, and it requires capabilities that don't exist yet.

Estimated data suggests that human contribution significantly enhances game quality in areas like visual consistency and narrative, compared to AI.

What This Means for Players

From a player's perspective, Larian's commitment means something simple: the game you're playing was created by humans making deliberate choices.

That doesn't mean it's perfect. Humans make mistakes. But it means the mistakes are intentional. The design is coherent. The vision is consistent. The art and writing reflect the sensibilities of creators, not the statistical patterns of a language model.

It also means you can trust the craft. You know that when a character speaks in a particular way, it's because a writer made that choice. When an environment looks a certain way, it's because artists designed it. That matters more than people sometimes realize.

There's also a message about respect for the art. Larian is saying: we respect the craft of concept art and writing enough to do it properly. We're not cutting corners. We're not using robots to do human work. We're investing in human talent and giving them the space to do their job well.

That's not anti-technology. It's pro-excellence. And it's a stance that players respond to. You see it in reviews and word of mouth: "The writing in this game is exceptional." That becomes part of the game's reputation.

For players who care about the ethics of AI, there's also clarity. You can play Baldur's Gate 3 knowing that the content you're experiencing wasn't generated by an algorithm in ways that might undermine human creators. That peace of mind matters to some people.

The Conversation Continues

Larian's decision isn't final. They said they're still experimenting. They said they might use AI for certain in-game assets if they train the models on proprietary data. The conversation is ongoing.

But the line they've drawn is clear enough to matter. No concept art. No writing. Everything else is open to testing, but only if it actually improves quality and speed without compromising the vision.

That's a thoughtful stance. It's not anti-AI dogmatism. It's not uncritical AI adoption. It's engineering pragmatism applied to creative decisions. "Does this tool make us better or faster without making the game worse? If not, why use it?"

The gaming industry is watching. Not just other studios, but players, critics, artists, and writers. Baldur's Gate 3 will be a test case. If the game ships with exceptional art and writing, and that's attributed in part to human-centric development decisions, then Larian wins the PR game and the quality game simultaneously.

If other studios start facing backlash for AI usage, they'll point to Baldur's Gate 3 as proof that the traditional approach works. And they'll make similar commitments.

That's how industry standards shift. One thoughtful decision at a time. One clear commitment at a time. One excellent product at a time.

Larian Studios excludes AI from concept art and writing, focusing on idea exploration, presentation development, and placeholder text. Estimated data.

FAQ

What did Larian Studios initially say about AI usage?

In an interview with Bloomberg, CEO Swen Vincke stated that Larian was experimenting with AI "to explore ideas, flesh out Power Point presentations, develop concept art and write placeholder text." The mention of concept art and writing immediately sparked significant backlash from the gaming community, artists, and developers who expressed concerns about outsourcing creativity to algorithms.

Why did Larian exclude AI from concept art and writing?

After testing AI tools, Larian determined that the quality and efficiency benefits didn't justify the approach. Writing director Adam Smith reported that AI-generated text scored only 3/10, worse than their baseline human first drafts (4/10), with enormous iteration requirements. For concept art, Larian concluded that using AI undermined design intentionality and the iterative thinking process essential to creating coherent visual worlds. They chose to exclude AI to eliminate the discussion about origin and maintain artistic control.

How does Larian plan to use AI in game development now?

Larian explicitly stated they won't use AI for concept art or writing in Divinity. However, they're continuing to explore AI applications where it can genuinely improve efficiency without compromising quality. This includes areas like Power Point presentations for internal communication, documentation, and potentially in-game assets trained on proprietary data. CEO Swen Vincke emphasized that AI should "aid us to refine ideas faster, leading to a more focused development cycle, less waste, and ultimately, a higher-quality game."

What's the difference between using AI as a creative tool versus a creative replacement?

Using AI as a tool means leveraging it to accelerate human decision-making, iterate faster, or explore variations—while humans maintain creative control and intentionality. Using it as a replacement means outsourcing the thinking to the algorithm. Larian's stance is that AI in creative foundations (art and writing) crosses from tool to replacement, where the algorithm is making fundamental design choices rather than assisting human creators. This distinction is crucial to understanding their position.

Why did the gaming community react so strongly to Larian's initial AI comments?

The backlash stemmed from multiple concerns: job security for artists and writers, questions about authenticity and craftsmanship in games, skepticism about corporate AI adoption based on historical precedent in other industries, and the specific phrasing that suggested AI was "developing" concept art (implying design responsibility) rather than merely assisting. The community had legitimate reasons based on how AI has been used to cut costs and reduce human involvement in other creative fields.

What does Larian's decision mean for other game studios?

Larian's approach provides a practical template for how studios can be intentional about AI adoption: identify critical creative areas, test thoroughly, measure against actual quality standards (not marketing claims), be transparent with stakeholders, and make decisions based on craft rather than cost reduction. Their willingness to exclude AI from areas where it doesn't genuinely improve quality sets a precedent that could influence industry standards. If Baldur's Gate 3 ships with exceptional art and writing attributed to human-centric development, other studios will face pressure to adopt similar practices.

Could proprietary AI models change Larian's stance in the future?

Yes. Vincke specifically mentioned that if they use AI for in-game assets, they'll train models on data they own rather than using public AI services. Proprietary models trained on a studio's own work might be more useful and raise fewer ethical concerns than public AI generators. However, this remains experimental, and Larian has made no commitments to implement proprietary AI for concept art or writing in the foreseeable future.

How do game writers feel about AI text generation in games?

Professional game writers share Larian's assessment that current AI writing doesn't meet quality standards for shipped products. The consensus is that AI can generate grammatically correct but emotionally flat text, while game writing requires nuance, character voice, world-building coherence, and the ability to surprise and reward players. These capabilities require human judgment and experience. AI might eventually improve, but current technology doesn't match the craft standards that experienced writers maintain.

What about concept art in other industries? Is AI more acceptable there?

The same tensions exist. In entertainment, design, and architecture, concept art serves as foundational thinking made visible. Using AI-generated concept art raises the same concerns about design intentionality, visual coherence, and the loss of iterative problem-solving. However, industries outside games have been slower to develop explicit commitments about AI usage. Larian's public stance is relatively rare because most studios avoid the topic entirely rather than making specific exclusions.

How will we know if Larian's decision pays off?

The clearest signal will be critical and player reception of Divinity (their next game) and any subsequent titles. If games developed with Larian's human-centric approach receive praise for artistic vision, writing quality, and world coherence, the approach validates itself. Conversely, if games from other studios using AI for concept art or writing receive criticism for incoherent design or generic writing, Larian's position strengthens. The market will ultimately decide whether quality justifies the traditional development approach versus efficiency gains from AI automation.

Wrapping Up: The Real Conversation About AI and Games

Larian Studios' decision to exclude AI from concept art and writing isn't about being anti-technology. It's about being pro-quality and pro-craft. These are different things.

The real conversation isn't whether AI is good or bad. It's about what tools serve your actual goals. Larian's goal is to make the best game possible. They tested AI. They measured it. They concluded it doesn't serve that goal in these critical areas. So they're not using it.

That's the reasoning that actually matters. Not principle. Not ideology. Pragmatism applied to craft.

The rest of the industry will watch. Studios will make their own decisions based on their own priorities and constraints. Some will use AI more aggressively. Some will follow Larian's path. Players will respond accordingly. That's how markets work.

But what Larian did right was make the choice explicit, explain the reasoning, and stand by the commitment. That builds trust. Not just with players, but with the creators who make these games. When a studio publicly says "we respect your craft enough to do it right," that matters.

The future of AI in game development will be shaped by decisions like this one. Not by AI capability alone, but by how studios choose to deploy it. Larian chose intentionality. That choice is worth paying attention to.

Key Takeaways

- Larian Studios explicitly excluded AI from concept art and writing for Divinity after testing showed the technology undermined creative quality and design intentionality.

- Writing director Adam Smith reported AI text generation scored only 3/10 quality versus 4/10 baseline human first drafts, requiring prohibitive iteration.

- The initial backlash wasn't anti-technology dogmatism but legitimate concerns about outsourcing creative thinking and following industry precedent of AI replacing human workers.

- Larian remains open to AI experimentation in areas like documentation, presentations, and proprietary in-game assets, but only where genuine quality and efficiency improvements occur.

- The gaming industry is watching this precedent closely—if Baldur's Gate 3 ships with exceptional art and writing, Larian's human-centric approach becomes a competitive advantage.

Related Articles

- 2025 Steam Awards Winners: Complete Breakdown [2025]

- Stop Typing: The Best Free Speech-to-Text Apps Like Handy [2025]

- Satya Nadella's AI Scratchpad: Why 2026 Changes Everything [2025]

- GTA 6 Delays & Game Announcements: Why Early Reveals Hurt [2025]

- 007 First Light Delayed to May 2026: What We Know [2025]

- Public Domain 2026: Betty Boop, Pluto, Nancy Drew [2025]

![Larian Studios AI Policy: No Gen-AI Art or Writing for Baldur's Gate 3 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/larian-studios-ai-policy-no-gen-ai-art-or-writing-for-baldur/image-1-1767980168498.jpg)