The Subscription Trap: Why LG's TV Rental Program Signals a Troubling Shift

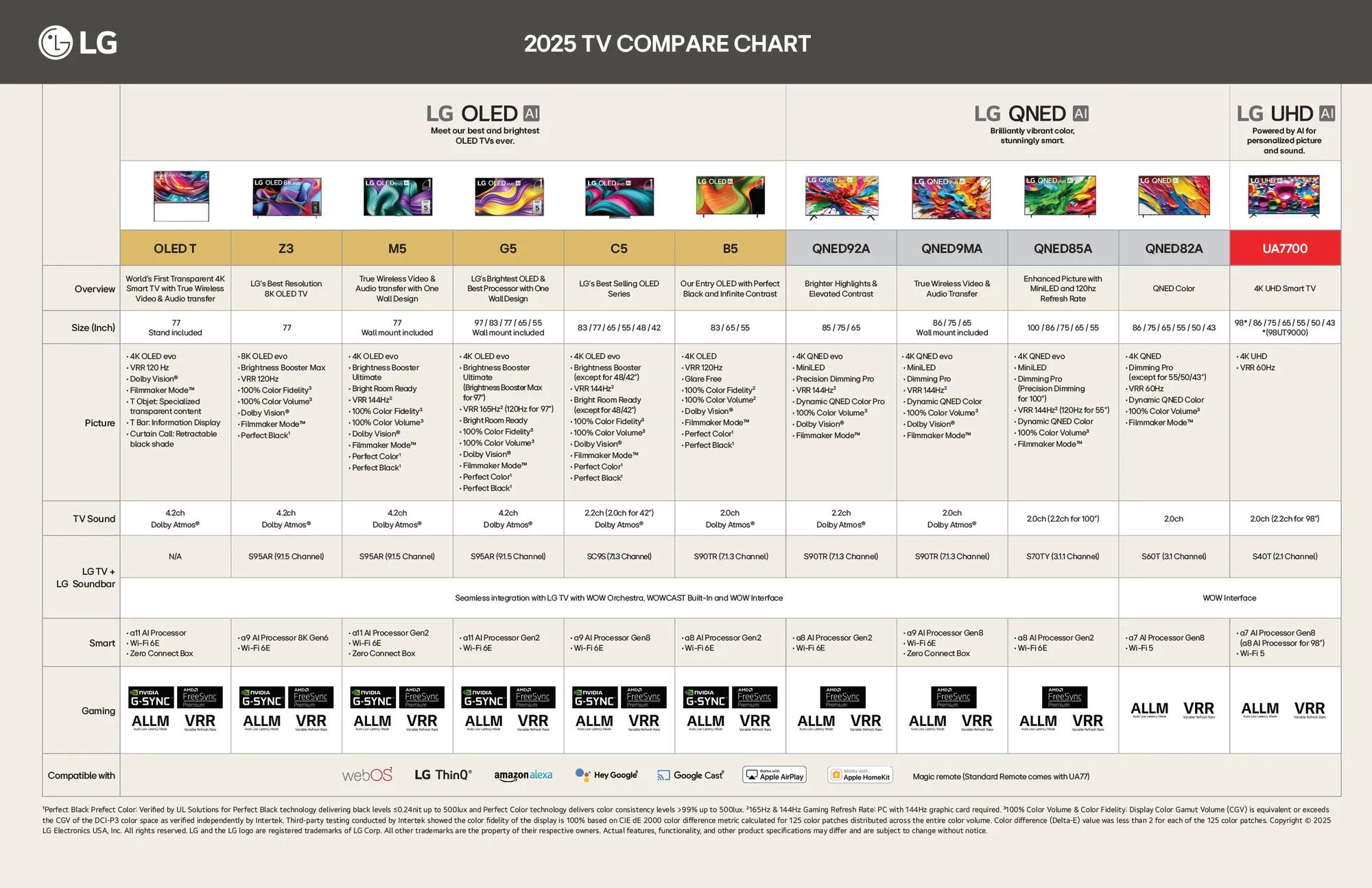

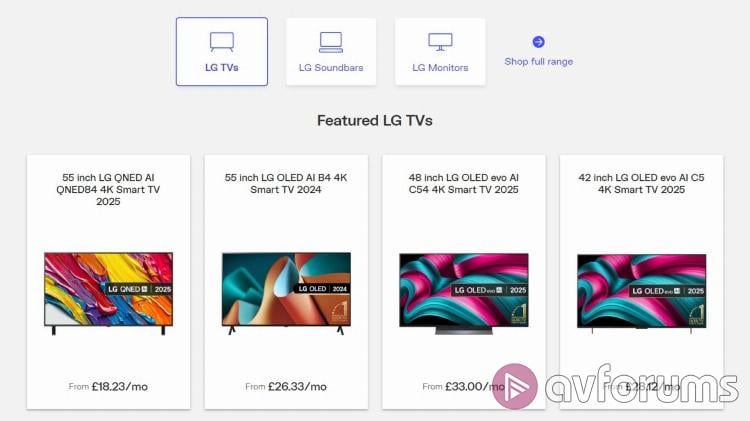

LG just launched something that sounds convenient on the surface but reveals a troubling trend in consumer electronics. The company now offers to rent you a TV for up to £277 per month in the UK. That's roughly $382. For context, you could actually own a solid 55-inch TV for that kind of monthly payment—in just a few months. According to Ars Technica, this move is part of a broader strategy to capitalize on recurring revenue models.

But here's what caught my attention: this isn't some experimental side project. LG is serious enough about the subscription model that they've partnered with Raylo, a device rental platform, to handle fulfillment. They've already tested rental programs in Singapore and Malaysia. And they're not alone. HP rents printers. NZXT rents gaming PCs. Even Logitech's CEO has suggested subscription mice are coming.

The message from these companies is clear: they'd rather build recurring revenue than sell you one TV that lasts a decade. And they're betting that convenience, upgrade paths, and low monthly payments will make you forget the math that actually matters.

Let me show you why that bet is dangerous for your wallet.

The Numbers That Should Scare You

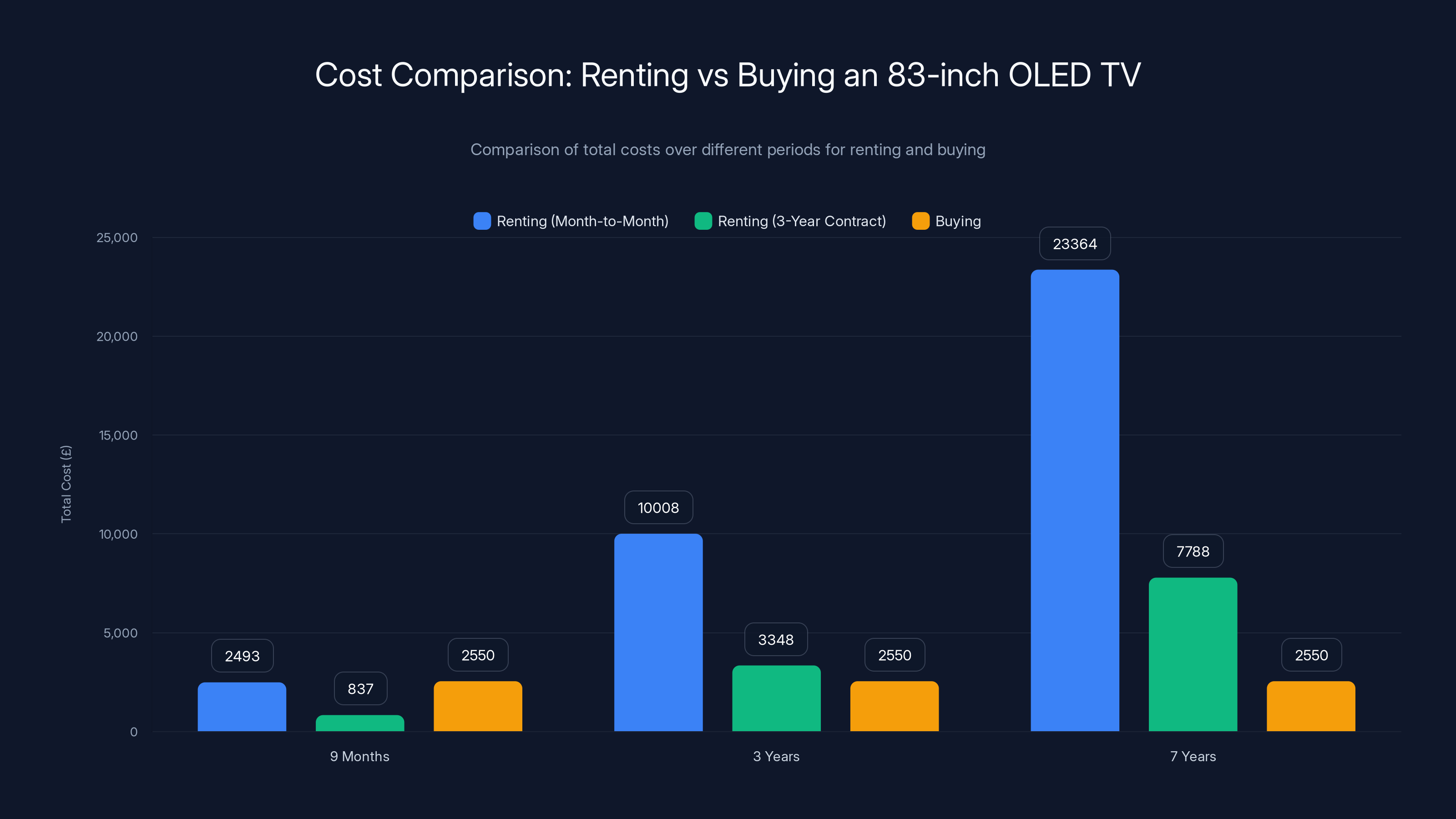

LG's 83-inch OLED B5 costs £2,550 if you buy it outright. That's the reference point. Now let's rent it instead.

If you commit to a three-year rental (the longest option), you pay £93 per month. That sounds reasonable until you do the multiplication: £93 × 36 months = £3,348. You've paid £798 more than the purchase price, and you own nothing at the end.

Wait, it gets worse.

At the highest monthly rate—£277 for a month-to-month commitment—you surpass the full purchase price in just nine months. Nine months. At £93/month on the three-year plan, you hit the purchase price at 27 months. That's barely into your three-year contract.

Here's the formula:

For the 83-inch OLED at £93/month:

This means that after 27 months of a three-year contract, you've paid the full retail price but have zero ownership. The remaining nine months? Pure profit for LG. Your money evaporates into the void.

The soundbar paints a similar picture. The LG 3.1.1 Dolby Atmos soundbar retails for £600. Monthly rental runs £22 to £76. At the three-year rate of £22/month:

Again, you hit the purchase price before your contract ends. Then you keep paying for months you've already paid off the device.

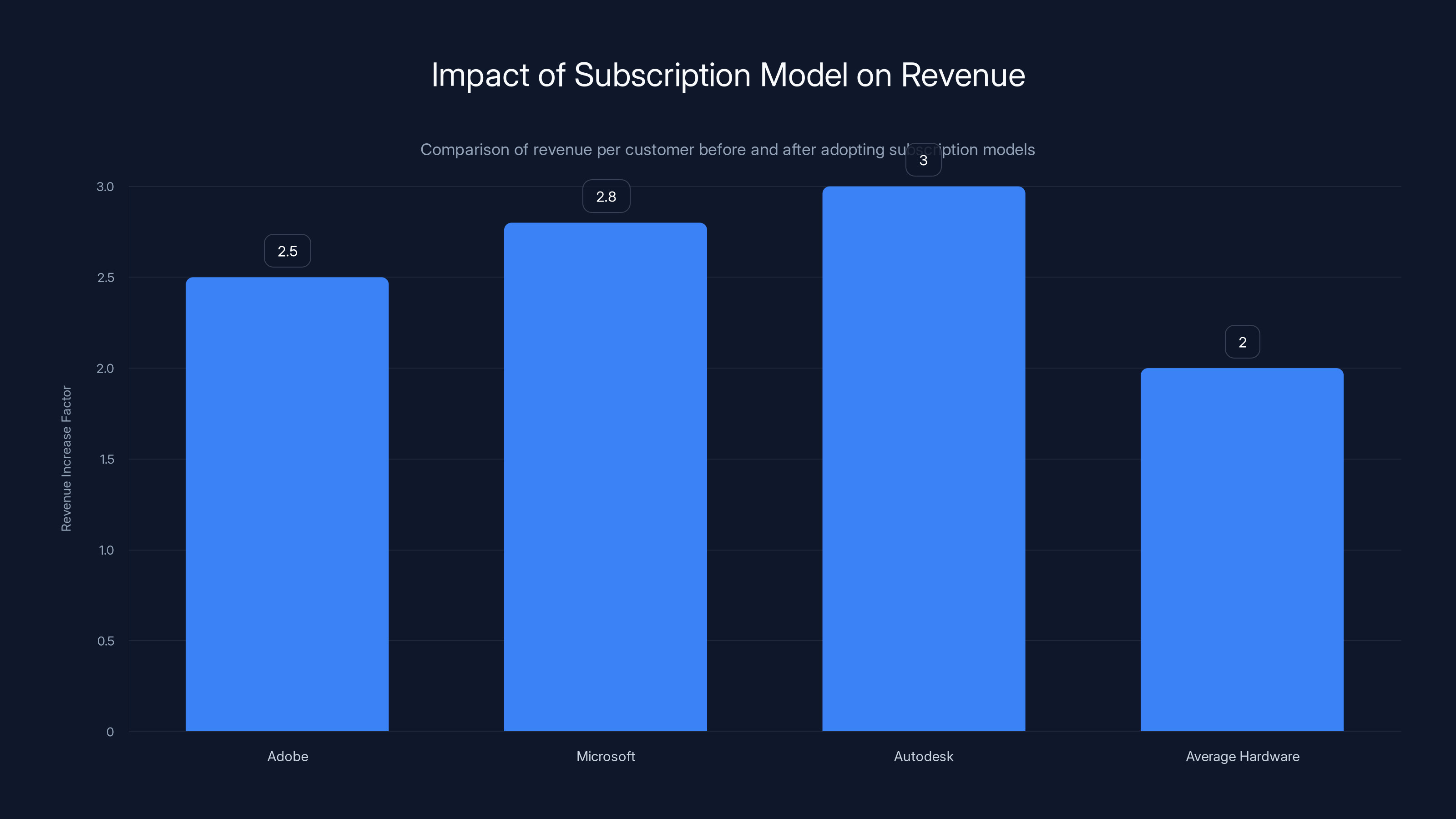

Adopting subscription models has increased revenue per customer by 2-3 times for software companies. Hardware companies like LG are exploring similar models. Estimated data.

Why Companies Love Subscriptions (And You Shouldn't)

From LG's perspective, this is brilliant. Instead of selling one TV every 7-10 years, they get predictable monthly revenue. If 100,000 customers rent an 83-inch TV at £93/month, that's £9.3 million in monthly recurring revenue. That's real money that shows up in predictable chunks, making shareholders happy and stock prices climb.

But the math is equally brutal in the other direction. LG makes more money when you rent than when you buy. The longer you rent, the better for them. The shorter you rent, the better for you—which creates a perverse incentive structure.

Think about what LG wants: customers who rent for 36 months and pay £3,348 for a £2,550 device. From a pure revenue perspective, an 83-inch OLED rented at £277/month is a goldmine, even if the customer only keeps it for three months. That's £831 on a device that costs £2,550 to manufacture and distribute. Profit margins that would make enterprise software companies jealous.

Meanwhile, the customer who buys? They pay once and leave. No follow-up revenue. No upgrade cycle. Just gone.

Companies solve this by making the math incredibly seductive in the short term. Yes, £277/month seems high. But "Yes, you only need £277 this month. Next month? You can return it or keep going." That flexibility is the hook. The sunk cost fallacy is the trap.

The Hidden Costs They Don't Advertise

LG's website says you won't be penalized for "obvious signs of use, such as scratching, small dents, or changes in paintwork." That sounds good. Then they add: "However, if you damage the rental device, LG may charge you for the cost of repair."

What counts as damage? The ambiguity is feature, not a bug. It creates leverage. It also means you need insurance.

Raylo offers accidental damage, loss, and theft coverage. They don't publicize the exact cost on their main page, which is itself a red flag. But based on industry standards, expect £10-20/month for comprehensive device protection. That's an additional £120-240 per year—money that doesn't get you any closer to ownership.

Then there's the removal fee. When you're done renting, LG charges £50 for "full removal service, including dismounting and packaging." For a TV that costs potentially thousands, that's relatively cheap. But it's £50 you don't pay if you own it and decide to move.

Add it up:

- Monthly rental: £93 (best case, three-year contract)

- Insurance: £15/month (estimate)

- Removal fee: £50 (one-time, amortized over 36 months = £1.39/month)

- Total: ~£109.39/month vs. £93 advertised

Over three years, that's £3,938 for a device worth £2,550.

Buying an 83-inch OLED TV is significantly cheaper over time compared to renting. Even with the best rental rate, costs exceed ownership by £798 over three years, and renting becomes 3-5 times more expensive over longer periods.

Upgrade Cycles and the Illusion of Progress

One selling point LG emphasizes: "At the end of your subscription, you can apply for a free upgrade, keep paying monthly, or return your device."

A free upgrade sounds amazing. In reality, it means starting a new three-year contract at current pricing for a new model. If OLED prices drop 20% over three years (they typically do), you've been overpaying the whole time, and now you're locked into new pricing at a newer model.

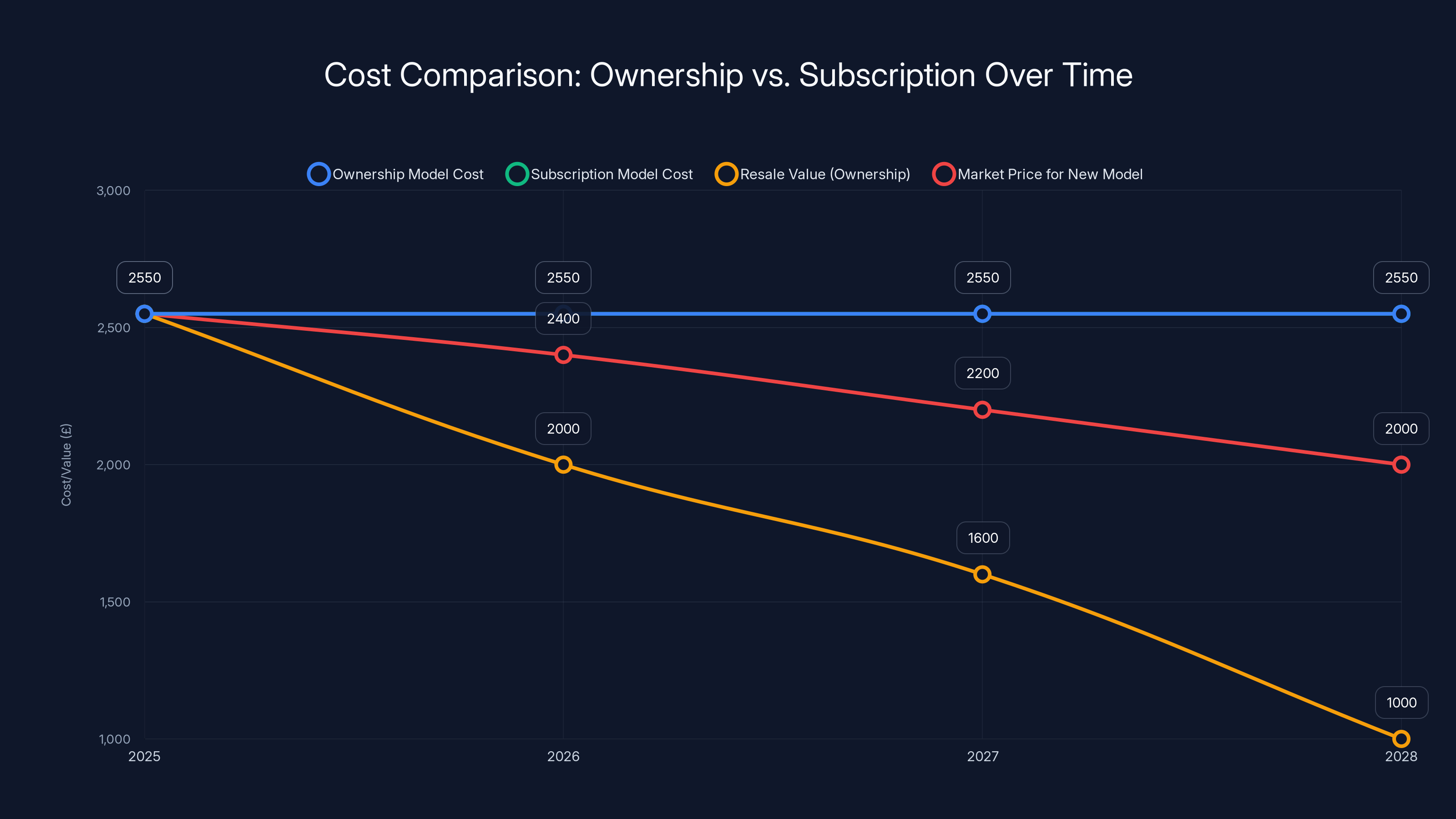

Compare this to the ownership model: buy a TV in 2025 at £2,550. By 2028, equivalent models cost £2,000. You still own your TV. You could sell it for £800-1,200 used, then apply that credit toward a new purchase. You captured some value. Under the rental model? You captured nothing.

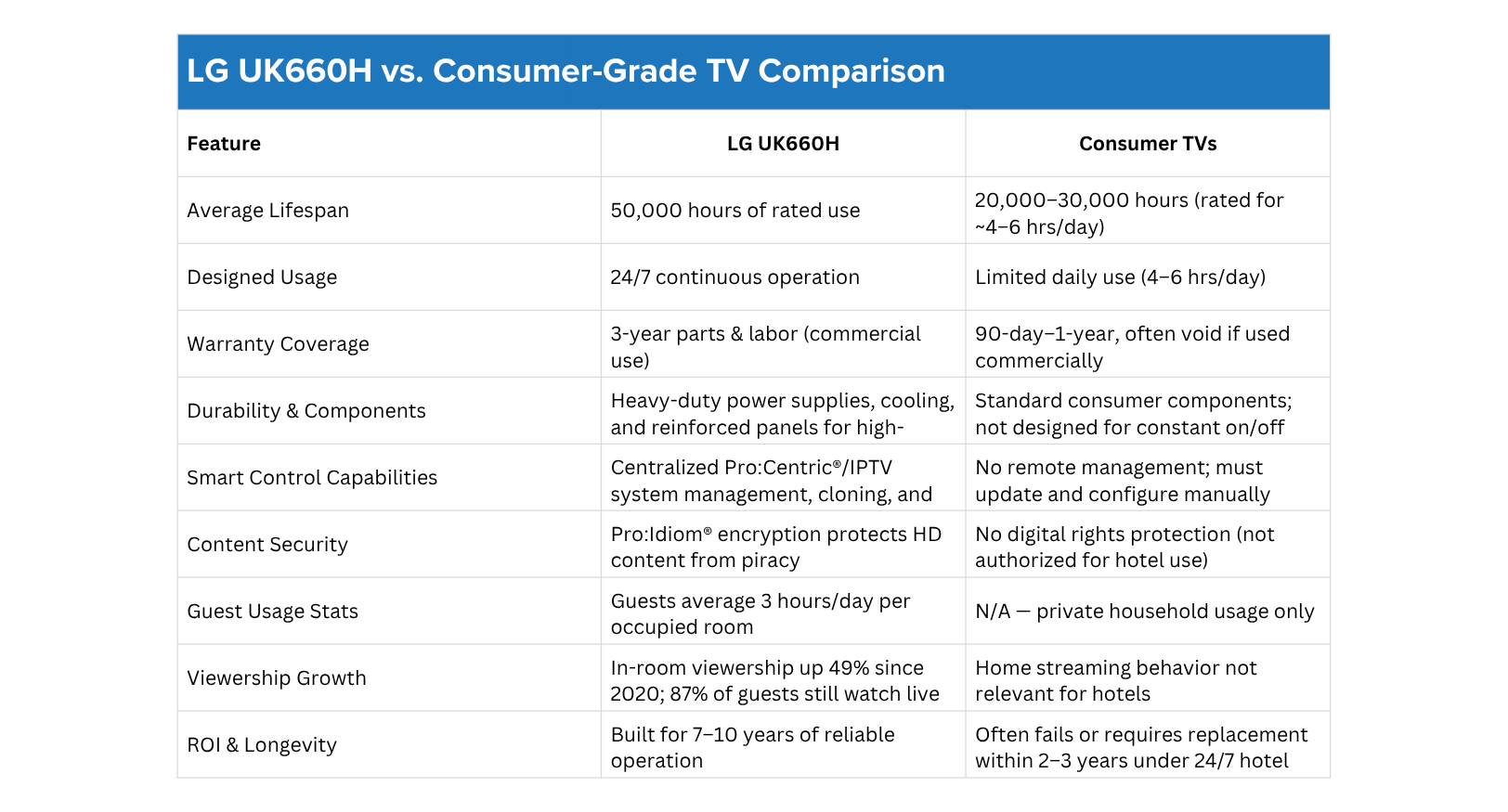

Upgrade cycles are designed for companies that need the latest hardware to stay competitive. Film production studios. Design agencies. Data centers. Gamers who need performance gains are a fringe case. Your 2022 55-inch TV is still a 2022 55-inch TV in 2025. It hasn't gotten worse. It hasn't become obsolete. You're being sold artificial urgency.

The Real Use Case: When Rental Actually Makes Sense

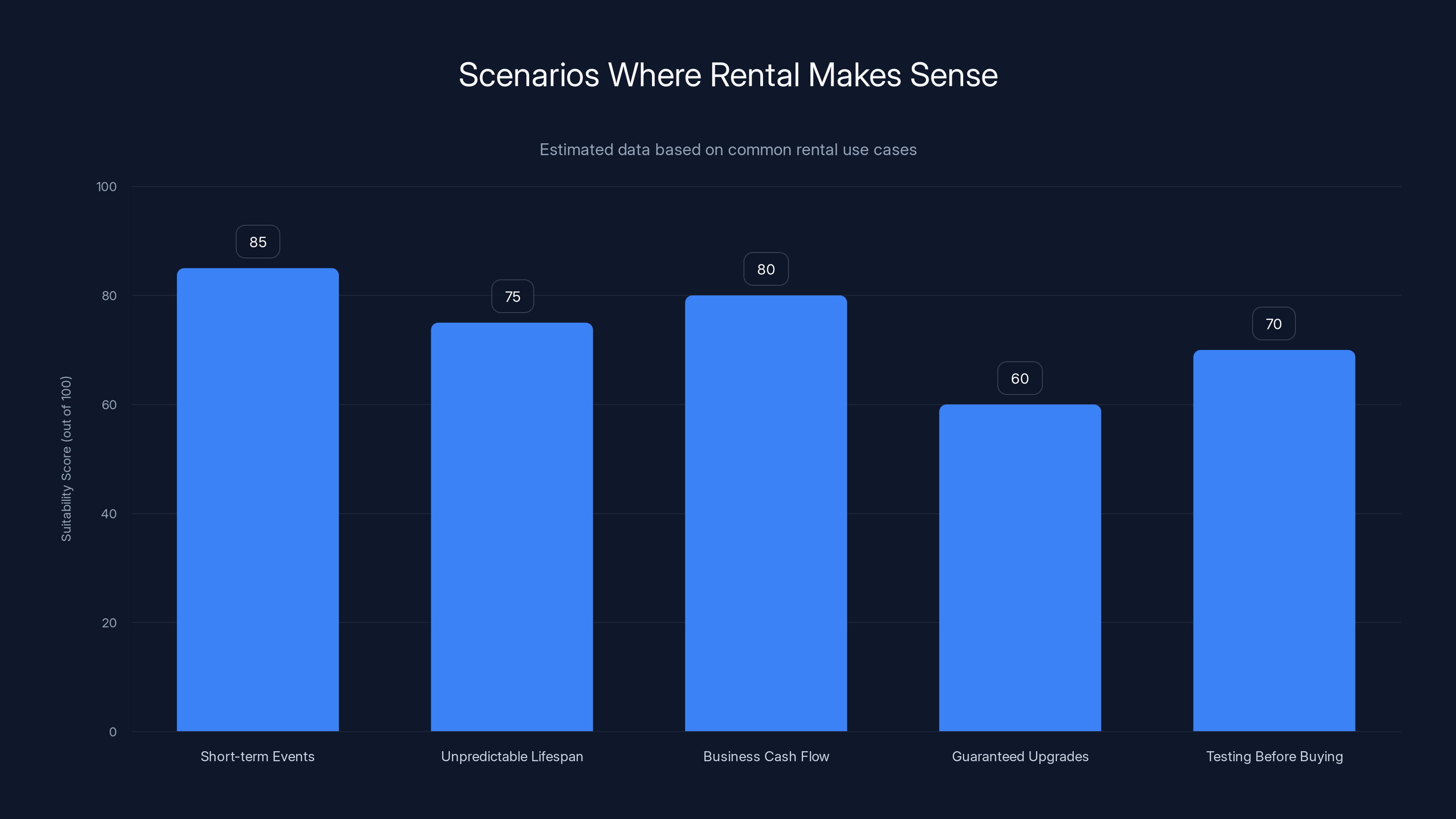

I need to be fair here. Rental isn't universally bad. There are legitimate scenarios.

Short-term events: Conferences, pop-up stores, temporary offices. If you need a TV for six months, buying and selling is wasteful. Rental wins.

Unpredictable lifespan: Outdoor events, harsh environments, places where equipment gets damaged regularly. Rental shifts the risk to the company offering it.

Business cash flow: Small businesses sometimes need expensive equipment but lack upfront capital. Rent-to-own structures (where rental payments build equity toward purchase) solve real problems.

Guaranteed upgrades: If you're willing to pay a premium for guaranteed annual upgrades and don't care about ownership, rental might fit your life. This is honest and rare.

Testing before buying: Rent for a month, decide if you love it, then buy. This is legitimate. But LG's pricing makes this expensive—one month at £277 is a steep test drive.

For everyone else—people who want to own a TV for 7-10 years—rental is a value trap disguised as flexibility.

Why This Trend Is Accelerating (And Why It Matters)

LG isn't being greedy. They're desperate. Here's why.

TV sales are flat to declining in developed markets. Everyone who wants a TV owns one. The upgrade cycle is 7-10 years. That's a boring, predictable business. Investors hate boring. Wall Street rewards companies that find new revenue streams, recurring revenue, and subscriber growth. Rental does all three.

LG is following the playbook that worked for tech software. Adobe shifted to subscriptions. Microsoft shifted to Game Pass and Microsoft 365. Autodesk ditched perpetual licenses. These companies went from "buy once, use forever" to "pay every month or lose access." Revenue per customer went up 2-3x. Investors celebrated.

Now hardware companies want the same game. HP, Logitech, NZXT, and LG are testing whether consumers will accept it. They'll watch the data closely. If enough people rent instead of buy, the playbook becomes standard. One day, owning a TV might feel like choosing desktop software over cloud subscriptions—quaint and increasingly difficult.

This is already happening in phones. Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile have normalized phone financing. Most people don't realize they're renting phones at $30-50/month instead of buying them. It's presented as "installments," but functionally, you're subscription-paying for hardware while the carrier captures residual value.

Consumer electronics manufacturers want the same thing with TVs, monitors, and speakers.

Estimated data shows that by 2028, the ownership model allows capturing resale value, whereas subscription costs remain constant. Market prices for new models decrease over time.

The Environmental Argument (That Doesn't Hold Up)

Rental companies often claim that subscription models are more sustainable. "Instead of discarding old TVs, we refurbish them and rent them again. Less waste."

It sounds good. The environmental math doesn't work.

Supply chains are optimized for purchase cycles. Manufacturing, shipping, and distribution are built for efficiency at scale. A TV manufactured once and used for seven years has a smaller carbon footprint than:

- The same TV manufactured for you

- Shipped to you

- Used for three years

- Shipped back to a facility

- Refurbished (disassembled, components replaced, reassembled, tested)

- Shipped to someone else

- Used for two more years

- Shipped back again

- Recycled or dismantled

That's more handling, more transportation, more energy. The refurbishment process itself consumes electricity and water. Components that could last 10 years get stressed by transit and customer mishandling.

Studies on device rental and sustainability are mixed, but the halo effect is real. Companies frame subscriptions as green. Consumers assume it's better. Neither assumption is proven.

The Return Logistics Nightmare

One thing LG glosses over: returning a TV is hard. They charge £50 for dismounting, packaging, and pickup. But before that, you need to:

- Schedule the removal (how long do you wait?)

- Clear the space (what if you've already mounted new furniture?)

- Deal with the physical TV (it's heavy, fragile, takes up space during removal)

- Track the return (does it ship safely? Who's responsible if it arrives damaged?)

LG claims they'll handle removal, but the responsibility transfer is murky. If the TV gets damaged during pickup, who pays? If it doesn't arrive at the facility, who's liable? These details matter, and the rental agreement is where the risk falls on you.

Compare this to ownership: you own the TV. Damage is your responsibility. Disposal is your choice. You can sell it, donate it, or recycle it. You have agency.

Under rental, you're dependent on LG's logistics. Delays, damage during transit, lost packages—all become customer service battles. The £50 removal fee is the price they charge to absorb the logistics cost. You're paying for convenience, but it's artificial convenience they've created by requiring rental in the first place.

Comparison: Rent vs. Buy vs. Finance

Let's map out the three paths for an 83-inch OLED TV worth £2,550.

Path 1: Buy Outright

- Cost: £2,550 upfront

- Ownership: Immediate

- Maintenance: Your responsibility

- Warranty: Typically 2-3 years

- Residual value after 7 years: ~£400-600

- Total cost over 7 years: £2,550 - £500 (average residual) = £2,050

- Cost per month (amortized): £24.40

Path 2: Rent at £93/Month (3-Year Contract)

- Cost: £93 × 36 = £3,348

- Ownership: None

- Maintenance: LG's responsibility (included)

- Warranty: Full coverage

- Residual value: £0

- Total cost over 3 years: £3,348

- Cost per month: £93

- Cost per month vs. ownership: 3.8x more expensive

Path 3: Finance at £60/Month (Interest-Free)

- Cost: £60 × 48 months = £2,880

- Ownership: After 4 years

- Maintenance: Your responsibility

- Warranty: Typical 2-3 years

- Residual value after 7 years: £300-500

- Total cost over 7 years: £2,880 - £400 = £2,480

- Cost per month (amortized): £35.43

The math is stark. Ownership is dramatically cheaper. Even finance deals beat rental. LG offering interest-free financing on the same TV undercuts their own rental program's value proposition. They're literally selling you two competing products where one is substantially better for customers.

They offer both because they know some people will choose the more expensive option if it feels simpler in the moment.

Renting an 83-inch TV for 36 months costs nearly four times more than purchasing it outright. Estimated data.

The Psychological Anchoring That Makes Rental Attractive

This is where psychology meets business strategy. LG quotes £277/month for month-to-month rental. That's high and anchors the perception of what rental costs. Then they drop to £93/month with a three-year commitment. It feels like a deal. £93 sounds low. It's "only" a tenth of the purchase price per month.

But that anchor—the £277 price—is a psychological trick. Nobody is meant to pay it. It exists to make £93 look cheap by comparison. Behavioral economists call this anchoring bias. You're not evaluating £93 on its own merits. You're evaluating it relative to £277.

If LG's only option was £93/month, fewer people would rent. Because £93/month is objectively expensive. It's just cheap relative to an inflated anchor.

Add in the language of flexibility: "You can return it anytime. Keep it as long as you want. Upgrade whenever you're ready." These are real benefits. They're also cheap to provide when the rental price is inflated. It costs LG nothing to let you return the TV—they've already captured the rental margin. Flexibility is a feature that feels valuable to customers but costs the company very little to offer.

The psychological wins are:

- Low monthly number (£93 looks small)

- Flexibility (no long-term commitment feels safe)

- Upgrade path (new tech without new cost feels good)

- Maintenance included (one payment, no surprises)

- Convenience (they handle everything)

All five are real benefits. None of them justify the price. But together, they create an emotional narrative that overcomes rational math. That's where companies want you operating—in emotion, not numbers.

What This Means for the Future of Consumer Electronics

If LG's rental program succeeds in the UK, expect expansion. The model scales beautifully. New markets, new devices, new commitment periods. LG will optimize based on customer behavior. Which rental periods drive uptake? Which price points maximize lifetime customer value? How many people upgrade before the contract ends?

Within three years, I'd expect rental programs from most major TV manufacturers. That's not pessimism—that's how businesses work. If it works, it spreads.

This creates a cascade effect. If every manufacturer offers rental, the social norm shifts. People stop asking "Should I rent?" and start asking "Which rental program is best?" The comparison framework changes, making expensive rental seem normal.

We're already seeing this with phones. Few people buy outright anymore. Most finance or lease through carriers. The phone-renting generation doesn't remember when you bought a phone and owned it forever. For them, monthly payments are normal. TV rental will follow the same path.

The long-term concern isn't LG's rental program. It's a world where ownership of consumer electronics becomes rare, and renting becomes the norm. That world is more profitable for manufacturers and more expensive for consumers. Rights shift. You don't own your TV, so you can't repair it with third-party components. You can't modify it. You can't jailbreak it. You lose control.

Manufacturers love that. Consumers should be wary.

Interest-Free Financing: A Better Alternative

Here's what LG doesn't want you to notice: they offer interest-free financing on the same TV you can rent.

If you can qualify for a 48-month interest-free loan at roughly £53/month, you own the TV completely. After four years, it's yours. The loan is done. You keep using the TV. No more payments.

Compare:

- Rent at £93/month for 36 months: Pay £3,348, own nothing

- Finance at £53/month for 48 months: Pay £2,544, own it

The financing option costs less, takes slightly longer, and leaves you with an asset. It's strictly better. Why would anyone choose rent?

One answer: qualification. Not everyone qualifies for a £2,550 loan. Credit checks, income verification, debt-to-income ratios—financial barriers exist. Rental lowers the barrier to entry. You don't need good credit to rent a TV. You just need a UK address and a payment method.

For people with poor credit or limited financial history, rental is access. That's real. It's also a subprime lending mechanism dressed up as convenience. You're paying 30% more for the same device because you can't qualify for traditional financing. That's not new; that's how subprime works across all consumer products.

LG isn't being evil. They're being pragmatic. Rental programs capture customers that traditional financing can't. More customers means more revenue. Shareholders are happy.

But ethically, it's worth noting: LG's rental program is effectively serving as a high-cost subprime lender. The interest rate is embedded in the rental price. It's just not called interest. It's called the convenience of paying month-to-month.

Rental is most suitable for short-term events and unpredictable environments, with a high suitability score of 85 and 75 respectively. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Subscription Creep Across All Categories

LG isn't alone. This is industry-wide.

Printers: HP's printer rental program exists because printer sales are declining and cartridge refilling is where margins live. Rent the printer, own the cartridge subscription. Revenue streams compound.

Gaming: NZXT's gaming PC rental program costs £25-45/month. You can buy similar-spec gaming PCs for £800-1,200. Breakeven is 20-50 months. It's the same math as TVs.

Furniture: IKEA has tested furniture subscription. Rent a sofa, return when bored, get a new one. It sounds sustainable (reuse instead of disposal). It's actually meant to drive upgrade cycles in the middle-income segment that currently buys IKEA once and keeps it 10 years.

Software: This is the template. Adobe, Microsoft, Autodesk, and others moved entirely to subscription. The result: software that's never finished, constantly updated, always requiring payment. It's more profitable. Users have less control.

Streaming: Entertainment subscriptions normalize monthly entertainment costs. Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV+. Collectively, you're paying

Now it's hardware's turn. The template is proven. The playbook is clear. Expect every consumer electronics category to follow the same path over the next five years.

How to Protect Yourself

If rental programs proliferate, you need a decision framework.

Ask these questions before signing any rental agreement:

-

What's the breakeven point? Multiply monthly rent by contract length. Does it exceed the purchase price before the contract ends? If yes, don't rent.

-

What's the ownership value? At the end, you own nothing. What would you own if you'd bought instead? (Equipment, equity, flexibility.) Is that value worth the premium?

-

What's the insurance really cost? Get damage, loss, and theft coverage in writing. Add it to monthly rent. Recalculate breakeven. Does it still make sense?

-

What happens if I want to return early? What are early termination fees? Is there a minimum period? Can you get out if your circumstances change?

-

What's my alternative financing? Interest-free loans, store credit cards, payment plans. Compare them head-to-head on total cost. Make sure rental is actually cheaper, not just easier.

-

How stable is the company? If Raylo or LG goes under, what happens to your TV? Who handles returns and refunds? Understand the legal structure.

-

Do I actually need upgrades? Rental's value proposition is frequent upgrades. If you're happy keeping a TV five years, ownership is better. Be honest about your upgrade frequency.

-

Can I buy it out? Some rental programs let you buy the device at the end for a fixed price. If LG offers buyout pricing, compare: monthly rent × months + buyout price vs. purchasing today. Sometimes buyout makes sense.

If you can answer these questions and still choose to rent, you've made an informed decision. Most people won't ask these questions. That's why rental is profitable for LG.

The Resale Value Wild Card

One variable I haven't fully explored: used equipment markets.

When you buy a TV, it depreciates. A £2,550 TV is worth £800-1,200 used after three years. That £1,000+ is real residual value. It reduces your true cost of ownership.

Rental programs damage resale markets. If LG is flooding the market with "certified refurbished" TVs from returned rentals, the used TV market gets compressed. Why buy a used TV from a private seller for £1,000 when you can rent a newer one for £93/month?

LG benefits twice: rental revenue from new customers and pricing pressure on the used market (which they don't participate in). You lose in both directions. Fewer people buying used means lower resale value when you eventually try to sell your owned TV.

This is why rental is so attractive for manufacturers. It's not just the recurring revenue. It's the market structure change that makes ownership less attractive by shifting the competitive landscape.

International Perspective: Why This Started in the UK

LG started rental in the UK, then Singapore and Malaysia. Why not the US or Germany first?

A few theories:

Regulatory environment: UK consumer protections are strong but less prescriptive than EU regulations. Less liability for "accidental damage" claims. EU would require clearer disclosures.

Market penetration: The UK has high TV saturation (~95% of households). Growth must come from upgrades and new revenue models. Rental is a growth play in a mature market.

Subscription precedent: UK consumers are accustomed to phone financing through carriers. The mental model of "monthly device payments" already exists. Rental feels natural.

Weaker dollar competition: The US has stronger competition from generic brands and market-rate competition on used devices. UK retail is more consolidated, making rental easier to position as premium.

Expect expansion to other English-speaking markets before continental Europe. Regulatory hurdles will delay or prevent EU adoption. The US will be next, likely within 12-24 months.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you need a TV:

Buy it. Seriously. Purchase price, ownership, done. Use it for 7-10 years. When you're ready to upgrade, sell the old one and put the proceeds toward a new one. You'll pay roughly £24-30/month (amortized) for a premium TV. That's a tenth of rental cost.

If you absolutely need flexibility:

Rent for one month to try it. Pay the high price. Decide if you love it. Then buy a slightly cheaper alternative that you've confirmed works for you. The rental month is an expensive test drive but worth it if it prevents buying the wrong device.

If you have poor credit and can't qualify for financing:

Consider rental as your option, not your first choice. It's expensive, but it might be accessible to you. Just understand what you're paying for and plan your exit (buying a cheaper alternative or saving for a down payment on financed purchase).

The broader point: Stay aware of the trend. Subscription and rental are coming to every consumer category. You can't avoid them entirely. But you can recognize the model, do the math, and make informed decisions. Most people won't. They'll see the low monthly payment and rationalize it away. That's exactly what LG is counting on.

FAQ

How does LG's TV rental program work?

LG's rental program, operated through partner Raylo, allows UK customers to rent TVs, soundbars, monitors, and speakers with monthly payments. Customers choose contract lengths (month-to-month, one-year, or three-year), with prices declining as commitment increases. At the end, you can upgrade to a newer model, keep paying monthly, or return the device. LG charges £50 for return removal and dismounting, and optional insurance covers accidental damage, loss, and theft.

Is it cheaper to rent or buy a TV?

Buying is dramatically cheaper. For an 83-inch OLED TV (£2,550 purchase price), month-to-month rental costs £277/month, making the device paid-off in nine months. Even at the best three-year rental rate of £93/month, you'll pay £3,348 total—£798 more than ownership—yet own nothing at the end. Ownership amortizes to roughly £24-30/month over a seven-year lifespan when you account for residual resale value. Rental is 3-5 times more expensive.

What are the hidden costs in LG's rental program?

Beyond advertised monthly rates, rental includes: optional insurance for accidental damage (estimated £10-20/month), a £50 return removal fee, wear-and-tear damage charges if significant, and potential early termination fees. Adding insurance increases effective monthly costs by 15-25%. These hidden costs aren't advertised upfront and significantly worsen the rental value proposition. Always request itemized costs before committing.

Should I consider interest-free financing instead of renting?

Interest-free financing is almost always better than rental. LG offers interest-free financing on the same TVs available for rent. At roughly £53-60/month for 48 months, you pay approximately the same as rental but own the device completely at the end. Financing requires credit qualification but is substantially better for anyone who can qualify. Calculate total cost over your expected ownership period; ownership almost always wins.

Why are companies like LG pushing rental and subscription models?

Manufacturers prefer rental because it converts one-time purchases into recurring revenue. Instead of selling one TV every 7-10 years, companies capture monthly payments, predictable customer lifetime value, and reduced competition from used markets. For investors, recurring revenue is more valuable than sporadic sales. LG has already tested rental in Singapore, Malaysia, and the UK; expansion to other regions is likely within 12-24 months as the model proves profitable.

What are legitimate use cases for TV rental?

Rental makes sense in specific scenarios: short-term events (pop-up stores, temporary offices, conferences), uncertain usage duration, high-damage-risk environments, and genuinely temporary needs. For permanent or long-term household use—which is 95% of consumer TV purchases—rental is a value trap. Businesses needing frequent equipment upgrades or temporary setups are the actual target market, not typical households. If you're keeping a TV more than three years, buying is categorically better.

Will subscription rentals become the standard for consumer electronics?

Most likely, yes. The rental playbook has already succeeded for software (Adobe, Microsoft), streaming (Netflix, Disney+), and phones (carrier financing). Hardware manufacturers are following the same path. HP has printer rentals, NZXT has gaming PC rentals, and Logitech is exploring subscription mice. Within five years, expect rental options from most major electronics manufacturers in developed markets. This shifts the default from ownership to access, making long-term savings harder and manufacturer control stronger. Staying informed about the economics now will help you navigate that future.

Conclusion: The Subscription Trap Is Real

LG's rental program isn't a mistake or a test. It's a calculated business strategy to extract more revenue from customers than they'd pay through traditional sales. The company isn't being hostile or predatory—they're following the playbook that worked for software, streaming, and phones.

But the math is simple: renting a TV costs 3-5 times more than buying one when you amortize costs over realistic ownership periods. The convenience, flexibility, and upgrade paths are real benefits. They're just priced so high that they don't justify the cost for typical consumers.

You have agency here. You can choose to buy, finance, or rent. But you have to make that choice with eyes open. Don't let the low monthly payment anchor your thinking. Calculate total cost. Compare alternatives. Ask the hard questions about insurance, early termination, and residual value.

Most importantly, recognize the trend. Subscription and rental are coming to everything. The companies pushing them aren't stupid—they're simply following the incentive structure that maximizes their revenue. Your job is to resist the narrative and follow the math instead.

The math says: buy the TV. Use it for seven years. Sell it for £400. Own your stuff. Don't rent it back to yourself at 3x the cost.

That's not cynicism. That's math.

Key Takeaways

- LG's TV rental costs 3-5 times more than ownership when you amortize costs over realistic usage periods (7-10 years)

- At £93/month (three-year contract), you pay the £2,550 purchase price by month 27 but keep paying with zero ownership value

- Hidden costs (insurance, removal fees, damage charges) increase effective monthly rental by 15-25%, worsening the value proposition

- Interest-free financing is almost always better than rental—similar monthly costs but you own the device at the end

- Subscription and rental models are expanding across all consumer electronics as manufacturers prioritize recurring revenue over one-time sales

![LG TV Subscription Rentals: Why £277/Month Doesn't Make Financial Sense [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/lg-tv-subscription-rentals-why-277-month-doesn-t-make-financ/image-1-1769540956315.jpg)