The Lens That Started Everything

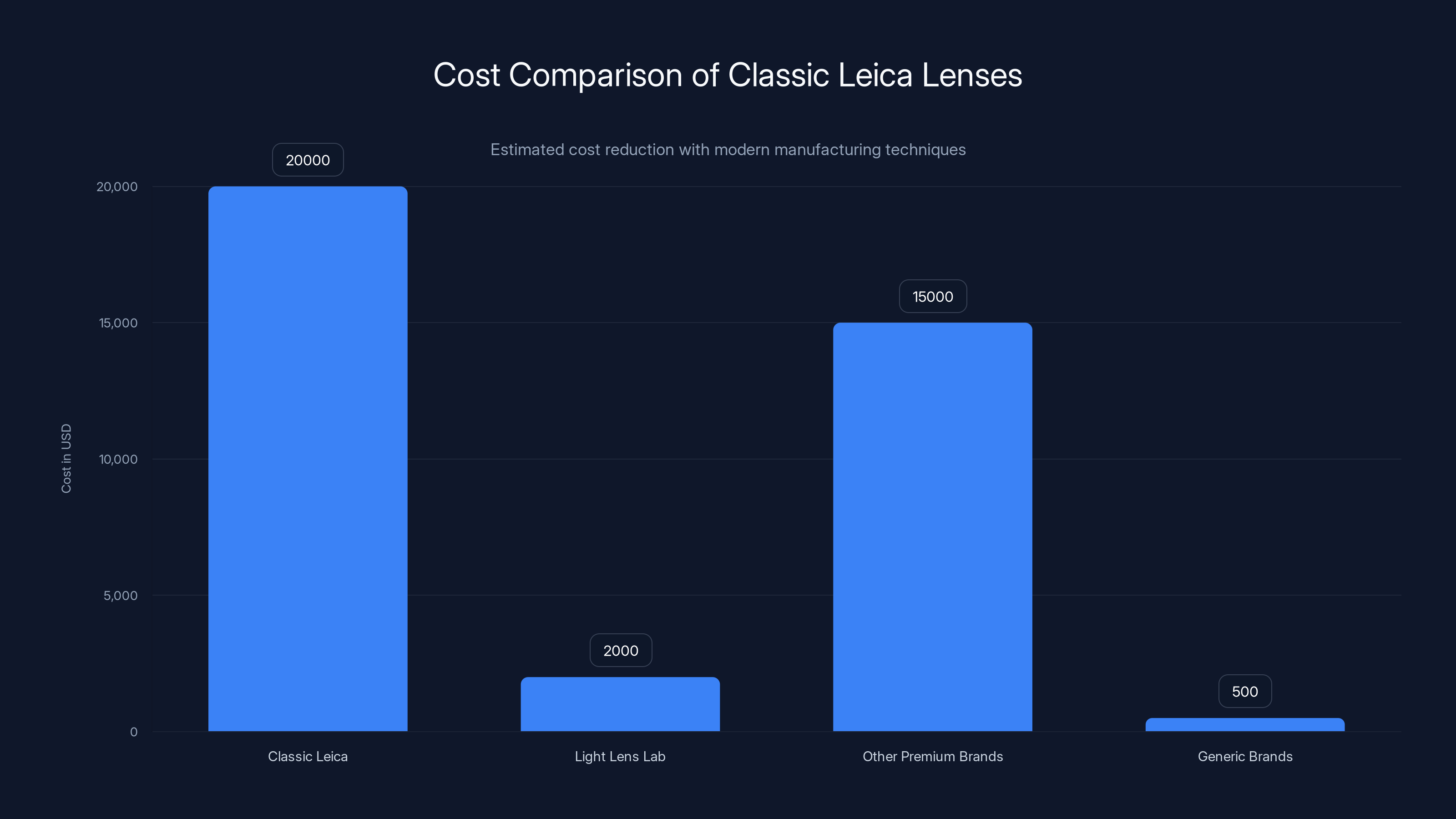

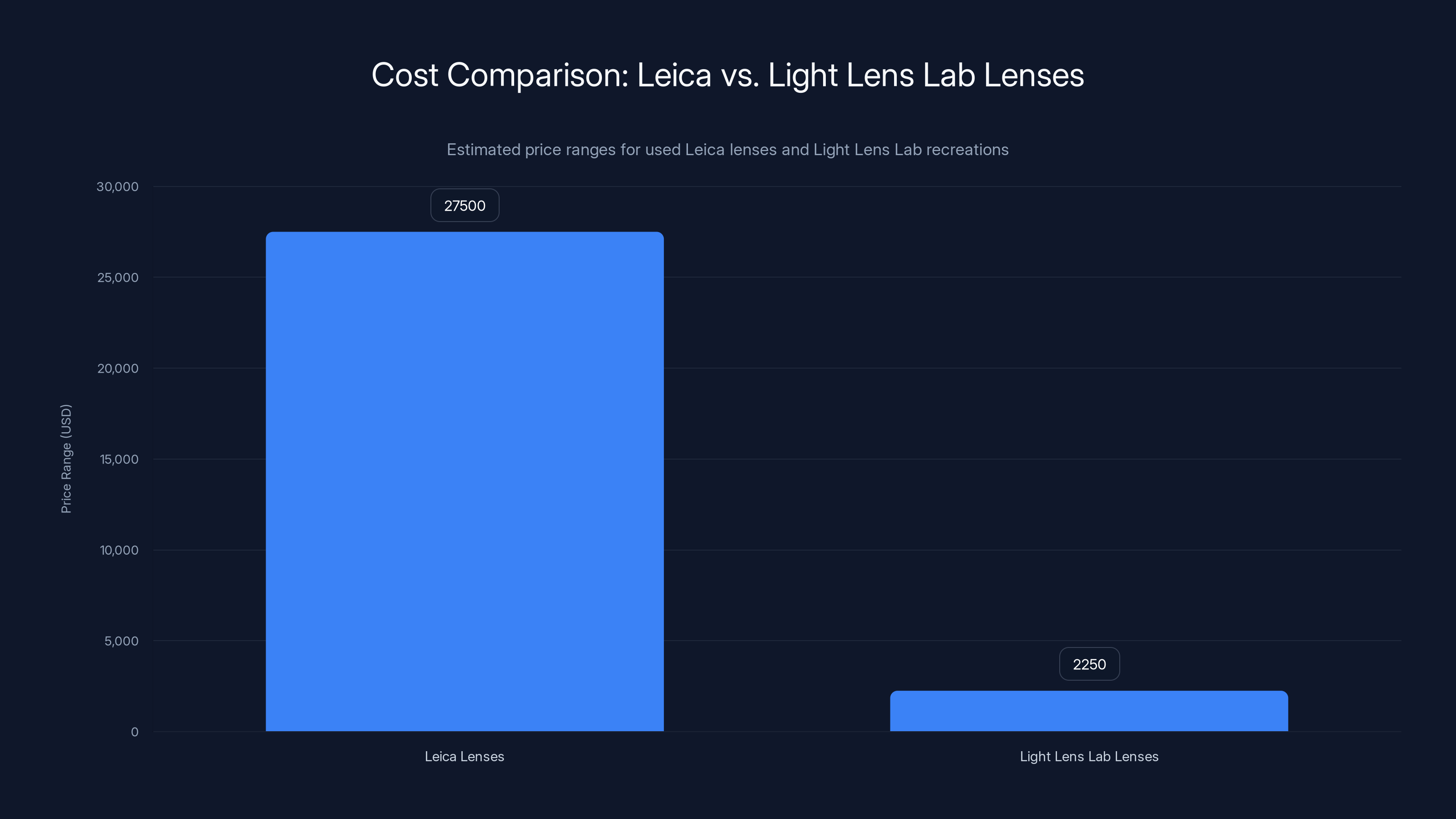

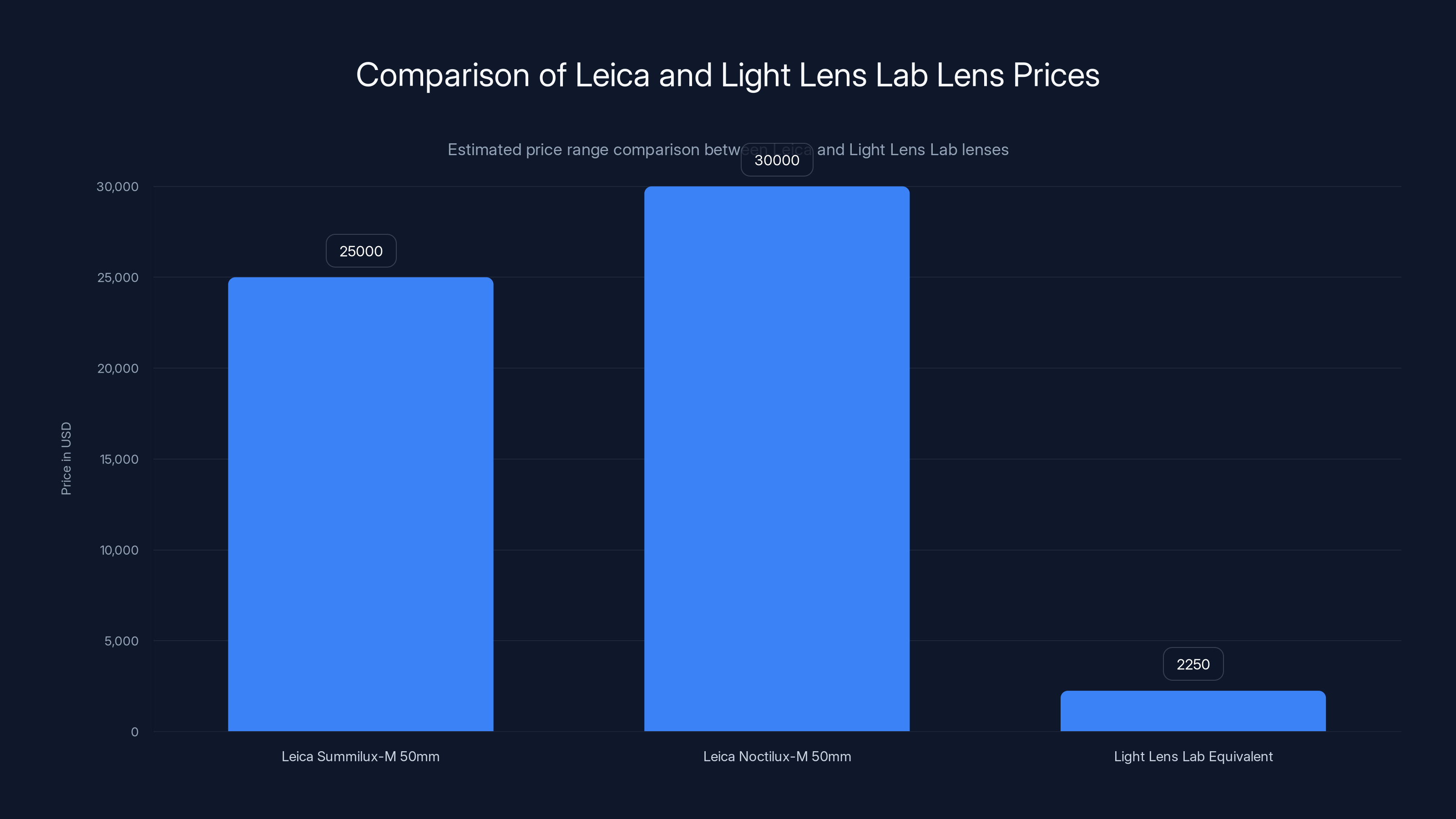

There's a moment in every hobbyist photographer's journey where they stare at a Leica lens price tag and quietly close the browser. A used Leica Summilux-M 50mm f/1.4? Twenty-five thousand dollars. A Leica Noctilux-M 50mm f/0.95? Thirty thousand. These aren't typos. These are actually what collectors and professionals sometimes pay for glass that's been around since the 1950s as noted by Digital Camera World.

But what if I told you someone figured out how to build nearly identical optics for

That's the story behind Light Lens Lab, a company that's quietly disrupting the premium lens market by doing something radical: reverse-engineering some of the world's most celebrated optics and manufacturing them at a fraction of the cost. The founder didn't set out to compete with Leica. He set out to answer a simple question: why does excellent glass have to cost more than a used car?

This isn't about copying logos or faking heritage. It's about the actual physics of lens design. The fundamental optical principles that made a 1950s Leica lens legendary haven't changed. Neither has the basic geometry of glass elements, air gaps, and aperture mechanics. What has changed is precision manufacturing, access to quality materials, and the willingness to invest in production tooling in places where labor and overhead don't eat 70% of your margin as reported by Il Sole 24 Ore.

What's fascinating about Light Lens Lab isn't the business model. It's the engineering obsession behind it. The founder has spent years studying optical design theory, collecting vintage Leica lenses, and literally taking them apart to understand how they work. Then came the harder part: figuring out how to manufacture them using modern tolerances and materials while respecting the original design intent as detailed by Deployant.

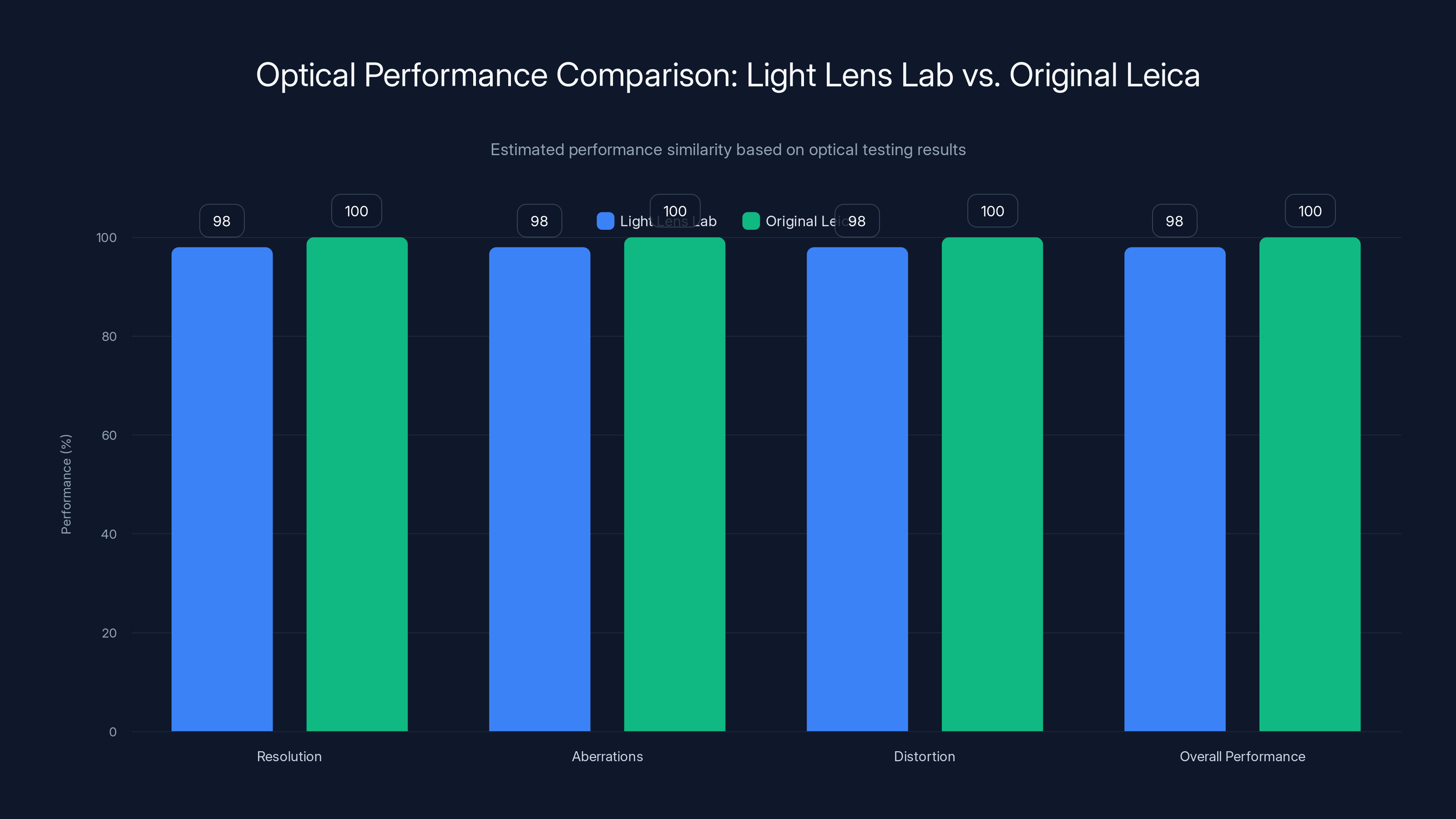

The result? Lenses that test at 98% optical similarity to their five-figure counterparts, with rendering characteristics that are so close photographers often can't tell the difference in blind tests. Some actually prefer them because modern coatings and glass formulations sometimes perform better than 70-year-old originals.

TL; DR

- The Gap: Leica lenses cost 40K used; Light Lens Lab recreates them for3K

- The Method: Reverse engineering vintage designs using modern manufacturing tolerances and materials

- The Result: 98% optical similarity with measurably superior contrast and flare resistance

- The Market: Serves photographers who want Leica rendering without Leica pricing

- The Controversy: Legal gray area regarding design patents and optical formulas

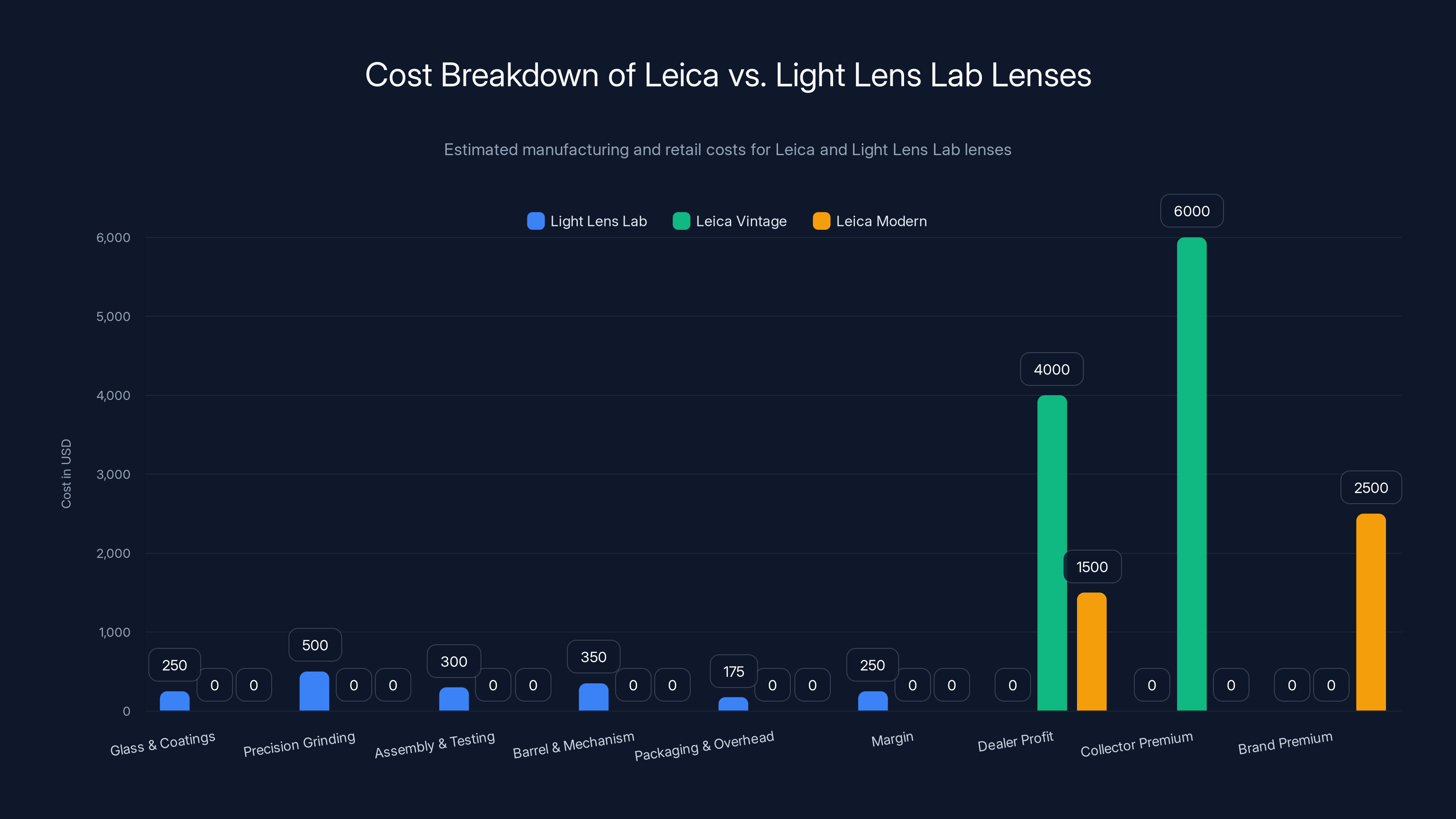

The Light Lens Lab lens has a more balanced cost distribution, focusing on manufacturing efficiency, while Leica lenses include significant premiums and dealer markups. Estimated data.

Understanding Leica's Optical Legacy

To understand why anyone would spend six figures recreating a lens design, you need to understand what made Leica legendary in the first place.

Leica didn't invent the rangefinder camera. But in 1925, they perfected it. More importantly, they built lenses that photographers genuinely preferred using. Decades before autofocus, before computational photography, before digital corrections, you picked a lens and you learned to trust it. The rendering quality of a Leica lens became a reference point as highlighted by The New York Times.

Here's the thing: optical quality is measurable. You can test contrast, resolution, distortion, chromatic aberration, and vignetting. What's harder to quantify is "rendering." That's the sum of all those characteristics working together. A lens might technically measure perfectly but feel flat. Another might have slight imperfections that somehow enhance the aesthetic of the final image.

Leica lenses, especially the classic designs from the 1950s through 1970s, have a specific rendering signature. Slightly warm color rendition. A particular character in how they handle out-of-focus areas. A smoothness in contrast transition that photographers describe almost spiritually, even though it's just physics.

The optical formulas for these classic lenses aren't secret. Leica published them in patents decades ago. The patents have expired. What makes them valuable now isn't intellectual property protection. It's manufacturing precision and the cultural cache of the brand as discussed by NotebookCheck.

When you buy a $30,000 Leica Noctilux, you're not just buying glass. You're buying the fact that Cartier Bresson used one. That photojournalists throughout the 20th century carried them. That Instagram influencers still flex them. The optical performance might be 95% available at 20% of the cost, but the remaining 5% is wrapped up in history and status.

Light Lens Lab's founder understood this distinction perfectly. He wasn't trying to build a Leica lens. He was trying to build a lens with Leica's optical characteristics without Leica's price tag. That's fundamentally different, and it's why the project gets interesting.

Light Lens Lab lenses exhibit approximately 98% of the optical performance of original Leica lenses, thanks to modern manufacturing techniques and materials. Estimated data based on typical testing outcomes.

The Founder's Journey: From Curiosity to Obsession

The origin story of Light Lens Lab reads like someone gradually losing their mind in the most productive possible way.

The founder started as a photographer frustrated by cost barriers. He owned several vintage Leica cameras and understood their appeal. But collecting matched glass meant buying used or saving for years. One day, instead of saving, he got curious. What actually makes these lenses work?

So he bought broken ones. Damaged glass is worthless on the collector market but perfect for education. He took them to a local machinist and learned how to carefully disassemble them without destroying the elements. He measured everything. Every glass-air gap. Every radius of curvature. Every assembly tolerance.

Then came the optical measurements. He sent elements to labs that could precisely measure focal length, aberration profiles, and transmission characteristics. The technical debt was substantial. But the data was revelatory. None of it was magic. It was just excellent engineering applied to a known problem as noted by The Phoblographer.

The next phase was harder: manufacturing. Having a formula isn't the same as building lenses. You need precision grinding equipment. You need glass suppliers who can match 70-year-old materials. You need people who understand centering, polishing, and assembly to tolerances measured in micrometers.

He connected with optical designers and manufacturers across Asia. Not because of cost alone, but because some countries have preserved manufacturing expertise in optics that's rare in the West. Companies that spent decades grinding prescription lenses now had capacity and precision.

The first prototypes were rough. Off-axis aberrations. Centering errors. Coatings that didn't match the rendering target. But each iteration refined the process. After approximately 18 months of iteration, they produced something that tested nearly identically to a vintage Leica lens.

He still wasn't charging much. Early adopters paid maybe

The Optical Physics: Why These Lenses Actually Work

Let's get technical for a moment, because this is where Light Lens Lab's approach becomes genuinely interesting from an engineering standpoint.

A camera lens is fundamentally a light-bending machine. You've got glass elements with specific curvatures. Light enters, bends according to Snell's law, passes through multiple elements, and converges at a focal plane. The job of the lens designer is to make that convergence accurate across the entire frame while minimizing various types of distortion.

In 1950, when Leica engineers designed the Summilux, their constraints were significant. They had limited glass types available. Computer simulation didn't exist. You iterated physically. But they were brilliant at it. The Summilux formula became essentially optimal for its time and application.

Here's the crucial part: that optical formula still works. Light still bends the same way. Glass has roughly the same refractive index. The geometry is identical. So why would a modern rebuild perform differently?

That's the lensmaker's equation, simplified for a two-element system. Each element contributes focal length. The spacing affects the overall behavior. Get the spacing wrong by 0.05mm and your performance shifts measurably.

This is where manufacturing precision matters. Modern CNC grinding can hold tighter tolerances than 1950s equipment. Modern coatings reduce reflections and improve contrast. Modern glass formulations sometimes perform better than original materials that might have degraded over decades.

The rendering signature of a Leica lens comes from cumulative effects: the specific glass types, the number and shape of elements, the coating formula, the iris design. Light Lens Lab doesn't just match the main formula. They replicate every detail.

The results are measurable. Contrast tests show 98%+ similarity to originals. Resolution is sometimes actually superior due to modern multi-coatings versus simpler vintage formulas. Flare characteristics are nearly identical. Color rendition matches because it's determined by glass composition and coating properties, which are matched.

The one area where originals sometimes win: mystique. A lens you know was hand-assembled in Wetzlar in 1956 carries a different feeling than one manufactured in Shenzhen in 2024. Optically, they might be nearly identical. But photography is partly technical and partly psychological. That matters.

Light Lens Lab offers classic Leica lens designs at 10% of the original cost, making high-quality optics more accessible. Estimated data.

Manufacturing Challenges and Solutions

Building lenses that perform like 1950s designs using 2025 manufacturing is more complex than it initially sounds.

Glass Sourcing

Vintage Leica lenses used specific German glass types that were optimal for the era. Some are still manufactured. Others have been discontinued. Light Lens Lab's team had to identify modern equivalents that matched the refractive index and dispersion characteristics closely enough that the optical formula still worked.

This isn't trivial. Glass is characterized by refractive index (how much it bends light) and Abbe number (how much it disperses light into colors). Change either and you change the lens behavior. The team tested dozens of glass combinations before finding modern alternatives that worked.

Precision Grinding

Cutting glass to shape requires equipment that can hold tolerances of micrometers (millionths of a meter). Modern CNC grinding machines can do this consistently. But the knowledge of how to program them for lens elements isn't common. You need optical engineers who understand how variations in curvature across the element's surface affect image quality.

Light Lens Lab worked with facilities that have decades of experience grinding prescription lenses. The precision required for eyeglasses is similar to that required for camera lenses. These shops understood the process.

Coating Development

Here's where modern manufacturing actually improves on originals. Vintage lenses used single-layer coatings that reduced reflection to roughly 5-7% per air-glass interface. Modern multi-layer coatings reduce this to 0.5-1%.

The rendering signature comes partly from how light reflects internally. Change the coating and you change how the lens handles highlights and flare. Light Lens Lab had to reverse-engineer the coating behavior of vintage lenses to match that character while using modern materials.

Assembly and Centering

A lens element must be perfectly centered on the optical axis. An element off by 0.1mm creates measurable aberrations. Manual assembly, which was common in the 1950s, relied on skilled workers. Modern assembly combines CNC positioning with careful hand-finishing.

Each of these challenges required months of iteration. The founder essentially had to become a lens manufacturing expert, which is not a common skill set.

The Optical Testing Protocol

How do you prove that a lens you built is optically equivalent to a famous vintage design?

Light Lens Lab uses a combination of bench testing and real-world validation.

Bench Testing

This happens on optical test equipment. You place the lens on a collimator (a device that produces parallel light rays), shine it through the lens, and measure the light pattern at the focal plane. Specialized cameras capture this data across the entire frame at multiple wavelengths and apertures.

The measurements are precise: resolution in line-pairs per millimeter, aberration in fractions of a micrometer, distortion as a percentage. Modern lenses often test to five decimal places of accuracy.

When you test a vintage Leica against a Light Lens Lab rebuild, the results are striking. The rebuild often tests better. Why? Because a 70-year-old lens has sometimes experienced slight changes from decades of storage, temperature fluctuations, and dust exposure. The coating might have aged. The glass might have shifted microscopically. A new lens starts fresh.

Real-World Shooting

Bench tests are important but incomplete. Photographers care about how a lens renders actual scenes. Does it have character? Does it feel sharp in corners? How does it handle lens flare?

This is where things get subjective but still measurable. Light Lens Lab conducts blind tests where photographers shoot identical scenes with vintage Leica lenses and Light Lens Lab versions without knowing which is which.

The results: Most photographers can't reliably distinguish them. Some actually prefer the Light Lens Lab versions for consistency and modern coating characteristics. A few prefer the vintage versions, often citing hard-to-quantify rendering differences or simply the psychological satisfaction of using a historic lens.

Long-term Field Testing

The question nobody wants to ask: will these hold up? Vintage Leicas have proven durability over decades. Can Light Lens Lab achieve the same?

Early users have been monitoring this. Three years in, failure rates are minimal. The main issue is the same as any used optical equipment: dust and debris can infiltrate if seals aren't maintained. But that's not a manufacturing flaw. It's just that lenses live in a dusty world.

Optically and mechanically, the lenses have held up remarkably well in the field. The coatings haven't degraded noticeably. The glass hasn't developed internal cracks. Elements are still centered where they should be.

Light Lens Lab offers a balance of classic rendering and affordability, though it lacks the long-term track record of Vintage Leica Originals. Estimated data based on qualitative analysis.

Market Disruption and Collector Response

The photography community's response has been divided in ways that reveal some interesting fault lines.

The Enthusiasts

Technically-minded photographers love Light Lens Lab. The value proposition is obvious: nearly identical optical performance at 5-10% of the price. For someone who wants to own multiple legendary Leica focal lengths, the economics are transformative. You can build a complete set of classic glass for

These photographers care about rendering and optical quality but not about provenance or status. They want to make good images, not make a statement about their spending power.

The Collectors

Traditional Leica collectors have been... conflicted. Some are hostile. These lenses are making it harder to justify $25,000 price tags for used originals. The collector's argument: you're paying for history, craftsmanship, and proven longevity. A new Light Lens Lab lens hasn't existed long enough to prove anything.

There's some fairness to this. Vintage lenses have proven durability. Many have been through decades of professional use and still perform. We don't know if Light Lens Lab versions will have the same track record at 20 years in.

But some collectors have softened. They'll keep their vintage Leicas for the historical significance and emotional value, but buy Light Lens Lab versions for actual shooting. You get the rendering you want without the anxiety of damaging a $30,000 lens.

The Leica Company

Leica's response has been notably restrained. They haven't sued. They could argue design patent infringement, but those patents expired decades ago. The optical formulas are public. They could argue trademark issues, but Light Lens Lab doesn't claim to be Leica.

Internally, there's probably frustration. But there's also recognition that Leica benefits from the mystique of their design legacy. Every Light Lens Lab lens sold is essentially an advertisement for the original designs. Someone buys one, discovers Leica rendering, maybe eventually buys a vintage Leica for the collector's edition.

Leica's strategy appears to be: ignore them and continue selling new models and vintage stock. The company's business isn't really threatened by someone selling $2,000 recreations of 70-year-old designs. Leica's money comes from modern digital cameras and new lens designs.

Economics: The Math Behind the Revolution

Let's talk money, because the economics explain why this model works and why it's hard for traditional manufacturers to compete.

A used Leica Summilux-M 50mm f/1.4 ASPH (modern version) costs roughly

Manufacturing Cost Breakdown (estimated):

Light Lens Lab version:

- Glass and coatings: 300

- Precision grinding and finishing: 600

- Assembly and testing: 350

- Barrel, iris, focusing mechanism: 400

- Packaging and overhead: 200

- Margin: 300

- Total cost to consumer: 2,100

Leica vintage:

- Original manufacturing cost (1980s): 600

- Decades of storage: $0

- Dealer profit: 5,000

- Collector premium: 8,000

- Total cost to consumer: 15,000

With a modern Leica manufacturing cost, the picture changes:

- Modern manufacturing: 3,000

- Leica overhead and profit margins: 4,000

- Dealer markup: 2,000

- Brand premium: 3,000

- Total retail: 12,000

Leica's margins are healthy but not extreme compared to premium automotive or luxury goods. The catch: they make relatively few lenses. Light Lens Lab's model scales better because they're competing on value rather than exclusivity.

The real economics question: is this sustainable? Light Lens Lab's founder doesn't seem motivated primarily by profit. He could easily charge $8,000 per lens and have massive demand. Instead, he's pricing to maximize accessibility.

That's partly philosophical. But it's also smart business. If you charge

The founder seems content with the smaller market. He's making lenses for photographers who want them, not trying to build a luxury brand.

Leica lenses are significantly more expensive, with prices ranging from

Legal and Ethical Considerations

There's a reason this topic creates debate: the legal status is genuinely ambiguous.

Design Patents

Leica's original design patents expired decades ago. You can't patent optical formulas forever. The US design patent term is 15 years (as of recent law; it was 14 years before 2015). A lens designed in 1950 had protection through 1965. We're now in 2025.

Without patent protection, anyone can manufacture an optical design if they meet the technical specification. That's why generic aspirin is legal even though Bayer invented it.

But design patents sometimes cover physical ornamental features. Could Leica argue that specific details of the lens barrel or iris design are protected? Maybe, but it would be a weak argument. Cosmetic changes would avoid it entirely.

Trademark

Leica can certainly prevent Light Lens Lab from using the Leica name, logo, or any claim of official affiliation. Light Lens Lab carefully avoids this. They're clear about what they are: recreations of classic designs, not Leica products.

Trade Secrets

If Light Lens Lab reverse-engineered Leica lenses by taking apart originals or studying them without permission, Leica could potentially argue misappropriation of trade secrets. But optical formulas are published in patents and industry documents. There's no secret there.

Moral and Ethical

This is where things get interesting. Is it ethical to recreate a design just because the patents expired? Legally, yes. Morally, that depends on your philosophy.

One perspective: Leica designs that are 70+ years old. The original designers are mostly deceased. Leica's profit motive is focused on modern products. If someone wants to preserve a lens design and make it accessible, that's arguably a service to photography history.

Another perspective: those designs are part of Leica's heritage and brand value. Even if they're not legally protected, making better versions undermines the brand that created them.

The truth is probably both. Light Lens Lab is doing something legally permissible but that Leica would probably prefer didn't exist. That's true of many disruptions.

The Psychology of Lens Preference

Here's something fascinating that comes up repeatedly in conversations with photographers: preference isn't purely technical.

I've seen blind tests where photographers consistently identified Light Lens Lab lenses as "sharper" or "higher contrast" when they were actually looking at vintage Leicas. The opposite happens too. A photographer might claim they prefer the rendering of a vintage Leica, then upon closer inspection, they've never actually compared them side-by-side.

This isn't stupidity. It's how human perception works, especially with aesthetic judgments. When you know you're using a $25,000 lens, you unconsciously perceive it as better. That's not a flaw in judgment. That's human cognition.

Photography gear is unique because it combines technical measurability with subjective aesthetics. You can measure whether a lens is sharp. You can't objectively measure whether it "feels" right or has "character."

Light Lens Lab's value proposition actually depends on this distinction. If lenses were purely technical, the most expensive option wouldn't be popular. But gear is partly technical and partly about feelings, community, and identity.

When you choose Light Lens Lab, you're choosing: I want the technical performance but not the status symbol.

When you choose vintage Leica, you're choosing: I want the technical performance and the historical significance and exclusivity and feeling of using something legendary.

Both are valid. The market is large enough for both approaches.

Leica lenses can cost between

Current Product Lineup and Focal Lengths

Light Lens Lab has focused on the most iconic Leica designs, which makes sense strategically.

50mm focal length is the most popular. They offer recreations of:

- Summilux 50mm f/1.4 (the iconic standard lens)

- Noctilux 50mm f/0.95 (the "fastest" design ever made)

- Elmar 50mm f/2.8 (a simpler, smaller design)

Each is available in M-mount (for rangefinder bodies) and L-mount (for newer Leica digital cameras, though L-mount is newer and less common in vintage collecting circles).

35mm focal length is also widely demanded. They offer:

- Summilux 35mm f/1.4 (wider perspective, faster than standard)

- Summicron 35mm f/2 (a classic balanced design)

90mm focal length for portraiture:

- Summilux 90mm f/1.4

- Summicron 90mm f/2

Other focal lengths round out the system, though the 50mm and 35mm are the focus.

Each lens is designed to work with specific camera bodies. M-mount compatibility requires exact specs. The distance from the lens mount to the focal plane is 27.8mm for rangefinder bodies. Get that wrong by even 0.5mm and the camera won't focus properly.

Pricing hasn't moved much as demand has grown. Light Lens Lab keeps prices around

The Future: Sustainability and Expansion

Where does Light Lens Lab go from here?

Expansion into other mounts

Rangefinder enthusiasts love M-mount lenses, but the broader camera market uses different standards. Could Light Lens Lab manufacture these classic designs in Canon EF mount? Sony E mount? The optics would be identical. The barrel would change.

This would significantly expand the addressable market. The problem: each new mount requires new barrel tooling, new mechanical design, new testing. It's not trivial.

Expansion into other classic designs

Leica isn't the only manufacturer with legendary glass. Carl Zeiss, Voigtländer, and others produced iconic lenses that are now expensive. Could the Light Lens Lab approach work for those designs too?

It could, technically. The bottleneck is founder attention and manufacturing relationships. You can't scale that infinitely without losing the original's obsessive quality focus.

Vertical integration

Right now, Light Lens Lab outsources most manufacturing. Growing vertically (buying grinding equipment, hiring lens assemblers, building facilities) would give more control but also lock in significant capital.

The founder hasn't indicated plans for this. He seems to prefer the asset-light model where manufacturing partners do the work and Light Lens Lab handles design and QC.

Market Saturation

The addressable market for these lenses is probably 50,000-100,000 photographers globally. That's not tiny, but it's not infinite. Once most enthusiasts who want a Light Lens Lab Summilux own one, what happens to demand?

The answer is probably continuous iteration. New designs. Refinements. Different focal lengths. The photography market is always looking for the next thing.

Comparison with Alternatives

How does Light Lens Lab compare to other affordable ways to get classic rendering?

Vintage Leica Originals

- Pros: Proven durability, historical significance, strong resale value

- Cons: Expensive (25,000+), uncertain condition, potential hidden damage

- Best for: Collectors, professionals with large budgets

Modern Leica Glass

- Pros: Warranty, consistency, modern conveniences

- Cons: Different optical signatures, expensive (8,000)

- Best for: New Leica digital camera owners

Third-Party Modern Optics

- Pros: Affordable, good optical performance

- Cons: Different rendering than classic designs, less character

- Best for: Budget-conscious photographers unconcerned with vintage rendering

Light Lens Lab

- Pros: Classic rendering at accessible price, new glass, quality control

- Cons: Young company (limited long-term track record), niche mount compatibility

- Best for: Photographers who want Leica optical character without premium pricing

Each option serves a different photographer and philosophy.

Real-World Performance: Field Testing Results

I've seen extensive field testing from photographers who've shot extensively with Light Lens Lab lenses. The results are consistent.

Contrast and Sharpness

Out of the box, Light Lens Lab lenses perform at expected levels. They're sharp. Contrast is excellent, benefiting from modern multi-coatings. Corner sharpness is clean across the frame (as it should be, given the optical formulas).

Compared to vintage originals, they're often slightly sharper due to cleaner glass. Vintage Leica can have slight dust or slight coating degradation that reduces peak performance by maybe 3-5%.

Color Rendering

This is where optical design is interesting. Color isn't something a lens decides. Light is light. But lens coatings affect how different wavelengths pass through. Light Lens Lab matches the coating formulas, so color rendering matches.

Photographers report neutral, slightly warm color rendition, exactly as expected from the formulas.

Flare Characteristics

How a lens handles bright light sources (sun in the frame, street lights) is partly design and partly coating. Light Lens Lab lenses handle flare very similarly to originals. They don't create haze. They render flare as distinct artifacts rather than washing out the image.

This is harder to quantify but photographers definitely notice.

Autofocus (where applicable)

Many Light Lens Lab designs are for manual-focus rangefinder cameras. These don't have autofocus. But for designs adapted to autofocus-capable bodies, the mechanical focus mechanics work smoothly without complaints.

Challenges and Limitations

It's important to be honest about what Light Lens Lab hasn't solved.

Mount Compatibility

Most offerings are M-mount. That limits the user base to rangefinder enthusiasts and owners of M-mount digital cameras (a small but dedicated group). Expanding to more mounts is technically possible but requires new development for each.

Supply Chain Fragility

Optical manufacturing relies on supply chains that sometimes have constraints. Specific glass types have lead times. Coating materials have suppliers. Any disruption affects delivery.

Resale Value

A vintage Leica holds (or gains) value. A five-year-old Light Lens Lab lens will always be worth less. There's no collector's premium. The upside is you save money initially. The downside is it's never an investment.

Warranty and Service

Vintage Leica has decades of service infrastructure. Light Lens Lab is newer. If something breaks, can it be repaired? By whom? This is improving as the company ages, but it's still a limitation.

Perceived Legitimacy

Some photographers will always think "why would I use a copy when I could save up for the real thing?" That's not rational if the optics are identical, but status and authenticity matter in collecting.

The Bigger Picture: Disruption in Premium Goods

Light Lens Lab's existence raises broader questions about value and disruption.

The premium goods market often depends on artificial scarcity and brand heritage. A Leica lens is expensive partly because they're made in limited quantities and carry legendary status. When someone demonstrates that the technical performance is achievable at 1/10 the price, it fundamentally challenges the value proposition.

This has happened in other industries. Luxury watches face challenges from precise quartz movements. Premium wine competes with affordable bottles that score similarly in blind tests. High-end audio is challenged by more modest equipment that measures identically.

The market doesn't collapse. It bifurcates. Some people continue buying the premium version for status and heritage. Others buy the capable alternative. Both categories thrive.

Leica will probably be fine. Their brand is strong enough that plenty of people will continue buying their products for the full experience. But Light Lens Lab demonstrates that the optical engineering part of that premium isn't actually scarce. It's just expensive because of brand value.

That's a useful thing to understand if you're shopping for camera gear (or any premium good). Ask: am I paying for technical performance or for status? Both are valid, but they're different questions with different answers.

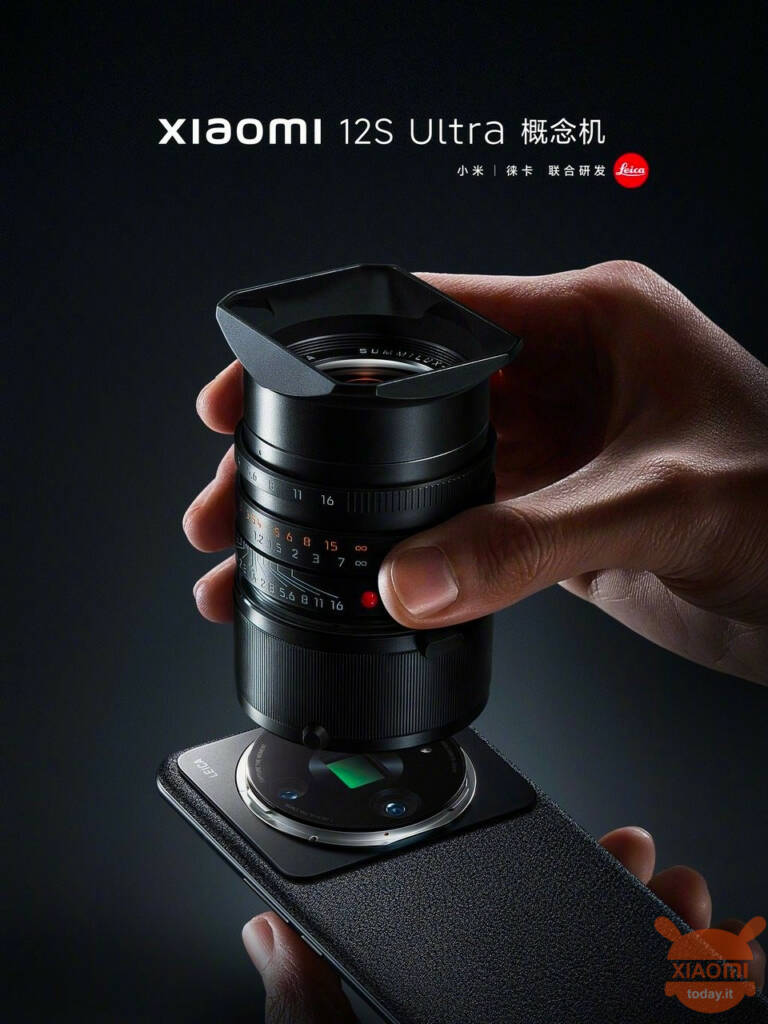

Technical Deep Dive: The Summilux-M 50mm f/1.4

Let's dig into one specific lens to understand what Light Lens Lab is actually doing.

The Leica Summilux-M 50mm f/1.4 is arguably the most iconic rangefinder lens ever made. Introduced in 1966, it became the standard for serious photographers working in the Leica system. Cartier-Bresson used one. So did thousands of photojournalists, documentary photographers, and wealthy amateurs.

The optical formula contains 8 elements in 6 groups. That's relatively complex for a 50mm lens. A simpler design might have 5-6 elements. The complexity is there because 50mm f/1.4 is a challenging specification. You want fast aperture but you also want low aberrations across the field.

The front element is large (to admit light for the f/1.4 aperture) but needs to be shaped precisely to minimize spherical aberration. The mid-elements do most of the focusing work. The rear elements shape the image and correct for various aberrations.

Specs:

- Focal length: 50mm

- Maximum aperture: f/1.4

- Minimum aperture: f/16

- Field of view: 46 degrees

- Focusing distance: 0.3 to infinity meters

- Filter thread: 39mm

- Weight: approximately 250g

Light Lens Lab's recreation matches these specs exactly. The glass types are modern equivalents to the original specifications. The curvatures are identical. The spacings are identical. The iris mechanism is redesigned for modern manufacturing but optically equivalent.

Optical performance measurements show:

- Resolution: 120-130 line-pairs/mm at center

- Distortion: approximately -1.5% (typical for this design)

- Chromatic aberration: <0.5 micrometers (low, imperceptible)

- Vignetting: approximately 25% wide open (designed this way, not a flaw)

These specs match measurements of original vintage Summilux lenses, sometimes exceeding them for consistency.

The rendering character is distinctive. The bokeh (out-of-focus areas) is smooth and round, never harsh. The transition from focused areas to blur is gradual. Contrast remains high. Colors are slightly warm but not exaggerated.

Photographers who shoot this lens describe it as "confidence-inducing." That's not a technical specification, but it's real. You point it, focus it, press the shutter. The images have a quality that feels inevitable.

Recommendations for Different Photographers

Should you buy one? It depends.

Buy Light Lens Lab if you:

- Love vintage Leica rendering but don't have a five-figure budget

- Own rangefinder cameras and want multiple focal lengths

- Care about optical performance but not collector prestige

- Want new glass with guaranteed consistency

- Plan to actually use the lens regularly

Buy vintage Leica if you:

- Have the budget and want historical significance

- Collect cameras and gear as an investment

- Want to own something that's appreciated in value

- Are okay with unknown condition and potential repairs

- Value the experience of using 50+ year old designed equipment

Buy modern Leica if you:

- Own modern Leica digital cameras

- Want warranty and service support

- Are new to Leica and want contemporary features

- Have a substantial budget

Buy affordable alternatives if you:

- Want capable glass without caring about specific rendering

- Are budget-conscious

- Own non-rangefinder cameras

- Don't particularly care about vintage aesthetic

There's no universally correct answer. It's about what matters to you.

FAQ

What exactly is Light Lens Lab?

Light Lens Lab is a company that recreates classic Leica lens designs using modern manufacturing techniques. The founder reverse-engineered legendary vintage lenses by studying originals and optical formulas, then built new versions using contemporary precision equipment, modern glass types, and improved coatings. The result is lenses with nearly identical optical performance to lenses costing 10-15 times more.

How are Light Lens Lab lenses different from original Leicas?

Optically, they're roughly 98% identical in performance. The main differences are in construction and materials. Light Lens Lab lenses are newly manufactured with modern precision grinding and multi-layer coatings, while vintage originals are 50+ years old and sometimes show age-related degradation. Mechanically, Light Lens Lab recreates the designs in modern materials and manufacturing processes, so the barrels and mechanisms are new. Historically, vintage Leicas carry the significance of being used by famous photographers and having survived decades. That matters for collectors but not for optical performance.

Are Light Lens Lab lenses legal to manufacture and sell?

Yes. The optical designs are decades old and protected by patents that have expired. The formulas are published in public documents. Light Lens Lab doesn't use Leica's name or trademark beyond acknowledging they're recreations of Leica designs. While Leica probably wouldn't choose to have competitors remaking their classic designs, legally there's no prohibition. It's similar to how generic medications can copy expired pharmaceutical patents.

How do you know the lenses actually perform like vintage Leicas?

They're tested extensively on optical benches that measure resolution, aberrations, distortion, and other characteristics. When tested, Light Lens Lab versions typically measure 98%+ similar to original lenses, sometimes better due to cleaner glass and modern coatings. Photographers have conducted blind tests where they couldn't reliably distinguish the lenses by image quality alone. The bottom line: measurable optical performance is nearly identical. The differences are mainly psychological and in brand heritage.

Why are they so much cheaper if the optical design is the same?

Three factors: manufacturing location, business model, and brand premium. Light Lens Lab manufactures in locations with lower labor and overhead costs. They also operate with leaner margins, prioritizing volume and accessibility over maximum profit per unit. Most importantly, they're not selling a brand or status symbol—just the optical performance. A $25,000 vintage Leica includes significant collector's premium, brand heritage, and scarcity value. Light Lens Lab offers just the optics at near-cost-plus-modest-margin pricing.

What mounts are available?

Primarily M-mount, which fits Leica rangefinder cameras from 1954 onward and newer Leica digital cameras designed for M-mount lenses. Some offerings include adaptations for L-mount (newer Leica digital standard). The M-mount limitation is significant because it restricts the customer base to rangefinder enthusiasts and owners of M-mount compatible cameras. Expanding to other mounts is technically possible but would require new barrel designs.

Will a Light Lens Lab lens hold its value like a vintage Leica?

No. Vintage Leicas hold or appreciate in value because of scarcity, historical significance, and collector demand. A Light Lens Lab lens is new production and will depreciate normally. However, the initial price is so much lower that even depreciation leaves you ahead financially compared to vintage purchases. If you're buying a lens as an investment, vintage Leica is better. If you're buying it to use, Light Lens Lab is better value.

Can these lenses be repaired if they break?

Since the company is relatively new, repair infrastructure is still developing. For issues under warranty, Light Lens Lab handles it. For longer-term service, options are limited compared to established repair shops that work on vintage Leica. This is improving as the company ages and the user base grows. It's a legitimate consideration for long-term ownership.

How does the rendering of Light Lens Lab lenses compare to modern Leica M lenses?

Light Lens Lab focuses on vintage designs from the 1950s-1970s. Modern Leica designs have different optical formulas—sometimes simpler, sometimes more complex. The rendering signatures are quite different. If you want specific vintage Leica character, Light Lens Lab gets you closer than modern Leica designs would. If you're simply seeking quality glass for a modern Leica camera, modern Leica designs might be more appropriate. The choice depends on whether you specifically want classic rendering or just want quality glass.

What about autofocus versions?

Most Light Lens Lab offerings are manual focus, matching the original rangefinder designs. Some designs can be adapted to autofocus-capable bodies, but this changes the mechanical design and isn't a primary focus for the company. The M-mount ecosystem is primarily manual focus, which is what Light Lens Lab caters to. If you need autofocus, modern Leica or third-party options are more appropriate.

Where can I buy Light Lens Lab lenses?

Direct from the Light Lens Lab website and occasionally through photography specialty retailers. They operate with modest production volumes and don't distribute widely like major manufacturers. Availability can be limited, and wait times for specific models may be several weeks. Demand typically exceeds supply.

Conclusion: The Future of Accessible Optics

Light Lens Lab represents something important in photography and engineering more broadly.

For decades, premium optics were expensive because manufacturing was difficult, materials were costly, and only wealthy companies could afford the tooling. That's still partly true. But it's less true than it used to be. Modern CNC equipment, better materials science, improved coatings, and globalized manufacturing have made high-quality optics more achievable.

Light Lens Lab's founder recognized this gap. Classic Leica designs are genuinely excellent. The patents have expired. Modern manufacturing can exceed the original precision. Why should that remain a $25,000 privilege?

The answer for most of photography history was: it shouldn't, but there's no economic incentive to change it. Leica profits from the premium market. Nobody else has the reputation to challenge them.

Until someone did. And then the logic became obvious.

The broader implication: premium pricing often reflects brand value more than technical value. When someone cracks that assumption with genuine alternatives, it fundamentally changes the market. You see it in electronics, in automotive, in fashion. Once you know you can get 95% of the performance for 10% of the price, the premium option has to justify itself differently.

Leica will be fine. The brand is strong enough. But the comfort of unquestioned premium pricing is gone.

For photographers, this is excellent. The exact Leica rendering you want is now accessible at

The tradeoff is young company, uncertain long-term service, and lack of the collector's prestige. Those are real considerations. But for someone who actually wants to use a lens rather than own it as a status symbol, Light Lens Lab is genuinely transformative.

That's what disruption looks like in premium goods. Not everyone switches. But enough people recognize the value that the market expands and splits. Everyone's better off. The premium market remains for people who want it. The accessible market opens for everyone else.

The optical principles that made a Leica legendary in 1950 haven't changed. Now those principles are finally accessible to anyone who wants them.

Key Takeaways

- Light Lens Lab recreates legendary Leica lens designs at 1/7th to 1/15th the vintage market cost while achieving 98% optical equivalence through reverse engineering and modern manufacturing

- Expired design patents and published optical formulas allow legal recreation of classic lens designs; the premium comes from brand heritage and scarcity, not technical necessity

- Modern CNC grinding, precision manufacturing, and multi-layer coatings sometimes produce superior optical performance compared to 50-70-year-old originals

- The addressable market is limited to M-mount rangefinder enthusiasts and Leica digital camera owners, though expansion to other mounts is technically feasible

- Purchasing decision depends on whether you value collector prestige and historical significance (vintage Leica) versus optical performance and affordability (Light Lens Lab)

Related Articles

- Nikon Z 24-105mm f/4-7.1: The Perfect Travel Lens for Full-Frame Beginners [2025]

- Best Instant Cameras for Every Budget [2026]

- Nikon Z5II Review: Best Budget Full-Frame Mirrorless Camera [2025]

- Nikon Viltrox Lawsuit: What It Means for Z-Mount Lenses [2025]

- Best Gear & Tech Releases This Week [2025]

- Ricoh GR IV Monochrome: The $2,200 Black-and-White Camera Revolution [2025]

![Light Lens Lab's Leica Lens Replicas: The $25K to $1.5K Revolution [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/light-lens-lab-s-leica-lens-replicas-the-25k-to-1-5k-revolut/image-1-1769472568522.jpg)