The Email That Changed Everything: Meta's Research Reckoning

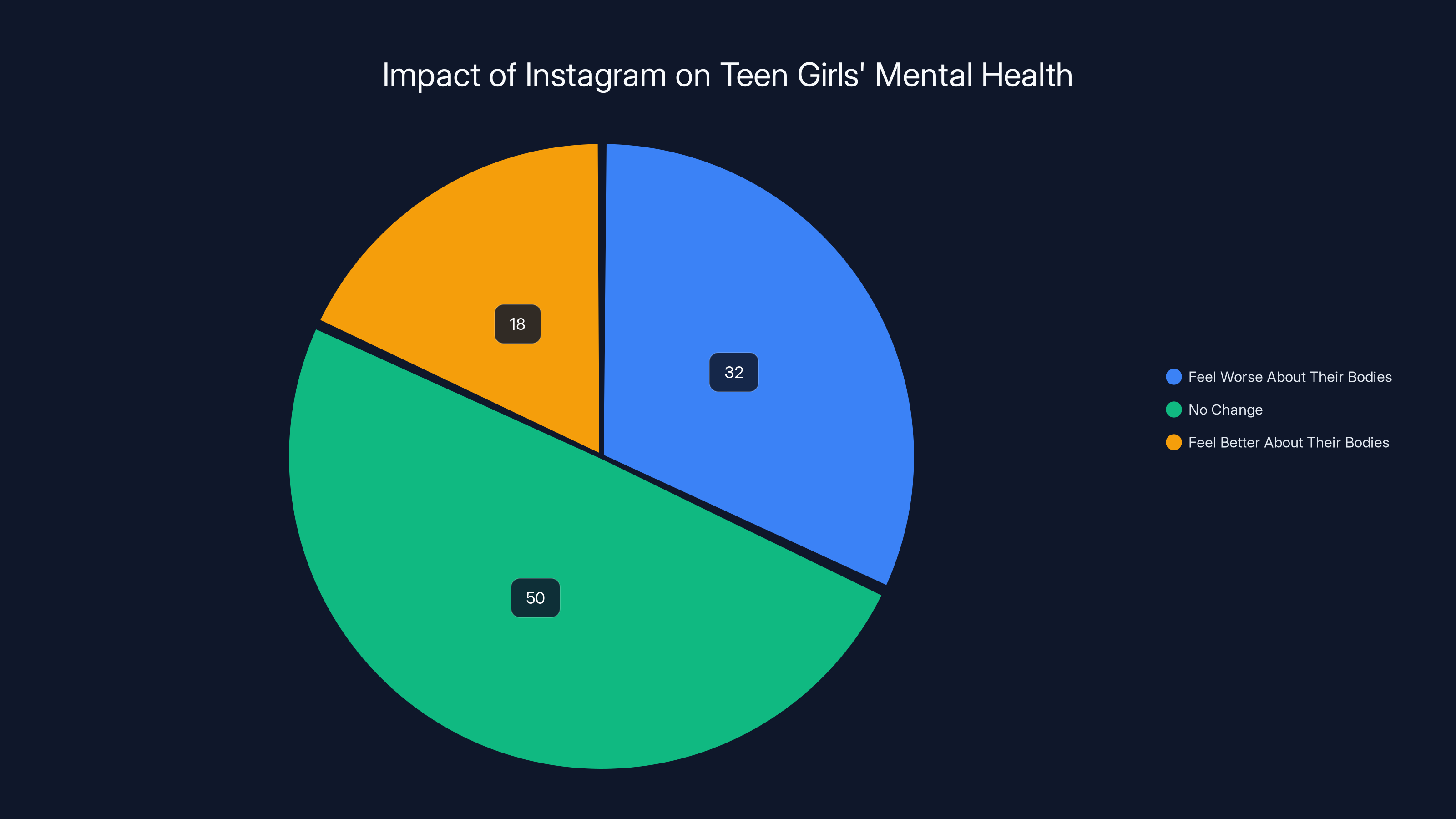

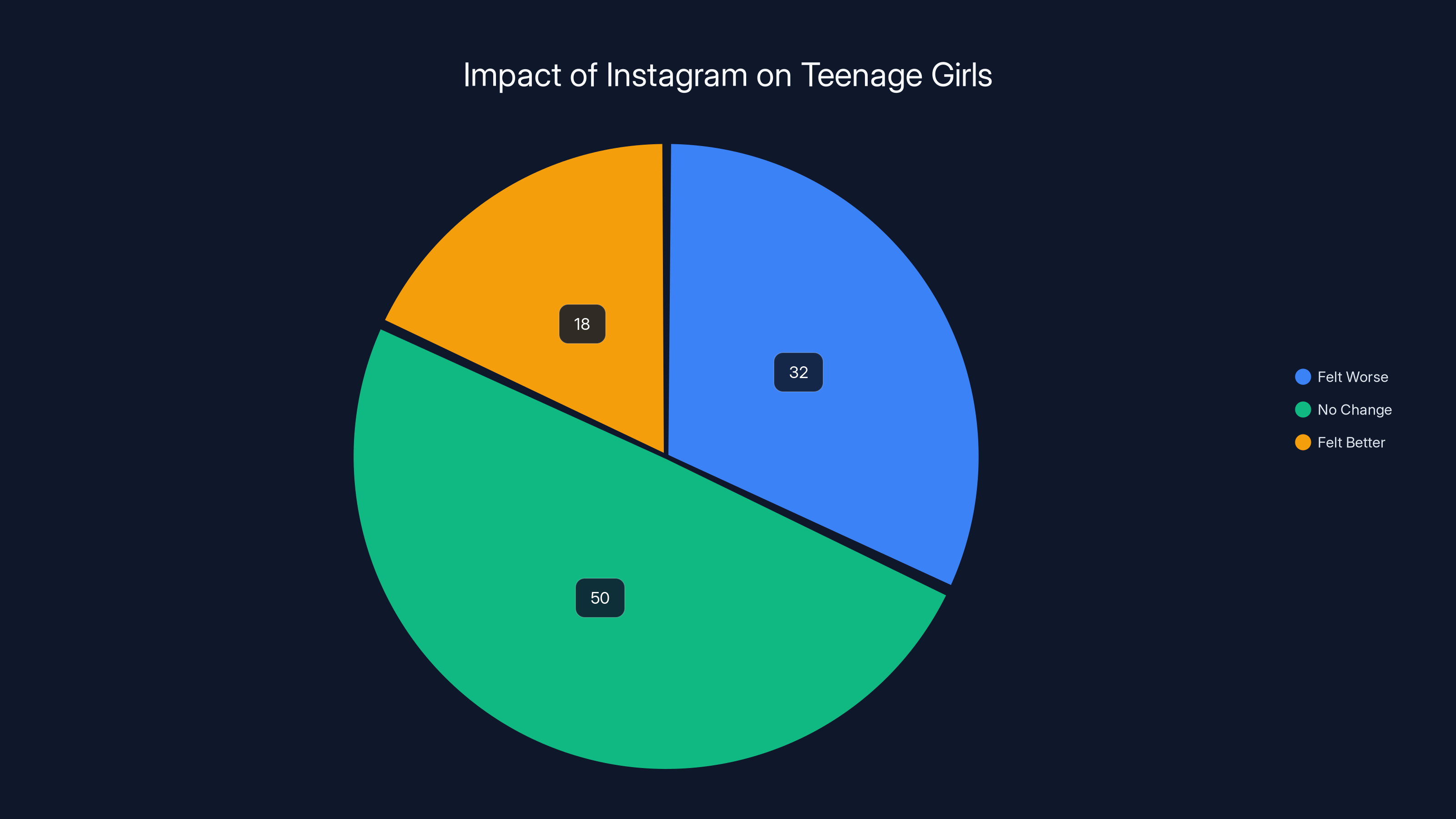

It started with one article. On September 14th, 2021, The Wall Street Journal dropped a bombshell story based on leaked internal documents about Instagram's devastating effects on teen girls' mental health. The data was damning: 32% of teenage girls reported feeling worse about their bodies after using Instagram. Some girls were battling eating disorders they attributed directly to the platform.

The next day, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg sent an email to top executives that would later become a centerpiece in litigation. The subject line read "Social issue research and analytics—privileged and confidential." What he wrote inside was stunning: he wondered whether Meta should fundamentally change how it studied harm on its platforms.

This wasn't a casual thought. This was the CEO of one of the world's most valuable companies considering whether transparency about internal research was actually hurting his company's image. The email was recently unsealed as part of the New Mexico Attorney General's case against Meta, a case alleging the company deliberately misled parents and regulators about the safety of its products for teenagers.

What makes Zuckerberg's email so revealing isn't just what it says about Meta's approach to research, but what it reveals about the entire tech industry's incentive structure. When doing research becomes a liability instead of an asset, when knowing about harm becomes legally and reputationally dangerous, companies face a choice: keep studying and facing criticism, or stop studying and avoid accountability altogether.

This is the paradox at the heart of modern tech governance. The more honest a company is about studying its own harms, the more ammunition it gives regulators, lawyers, and critics. The less it studies, the less it knows—but also the less it can be held accountable for knowing.

Zuckerberg's emails reveal a CEO caught between two deeply uncomfortable positions: continue Meta's reputation-damaging research and face scrutiny, or adopt a strategy of willful ignorance like Apple, which, as Zuckerberg noted, "doesn't seem to study any of this stuff."

The Strategic Vulnerability of Transparency

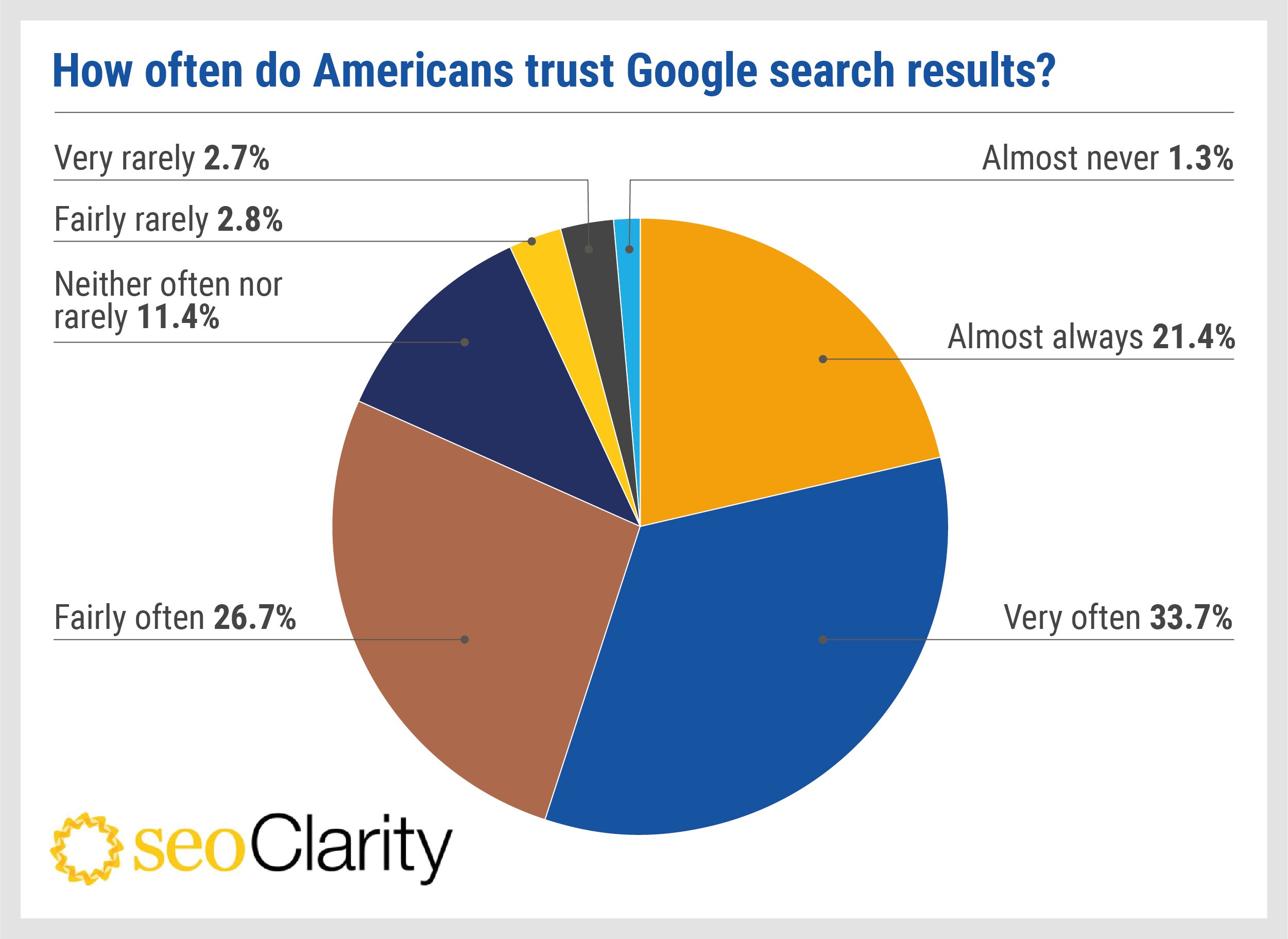

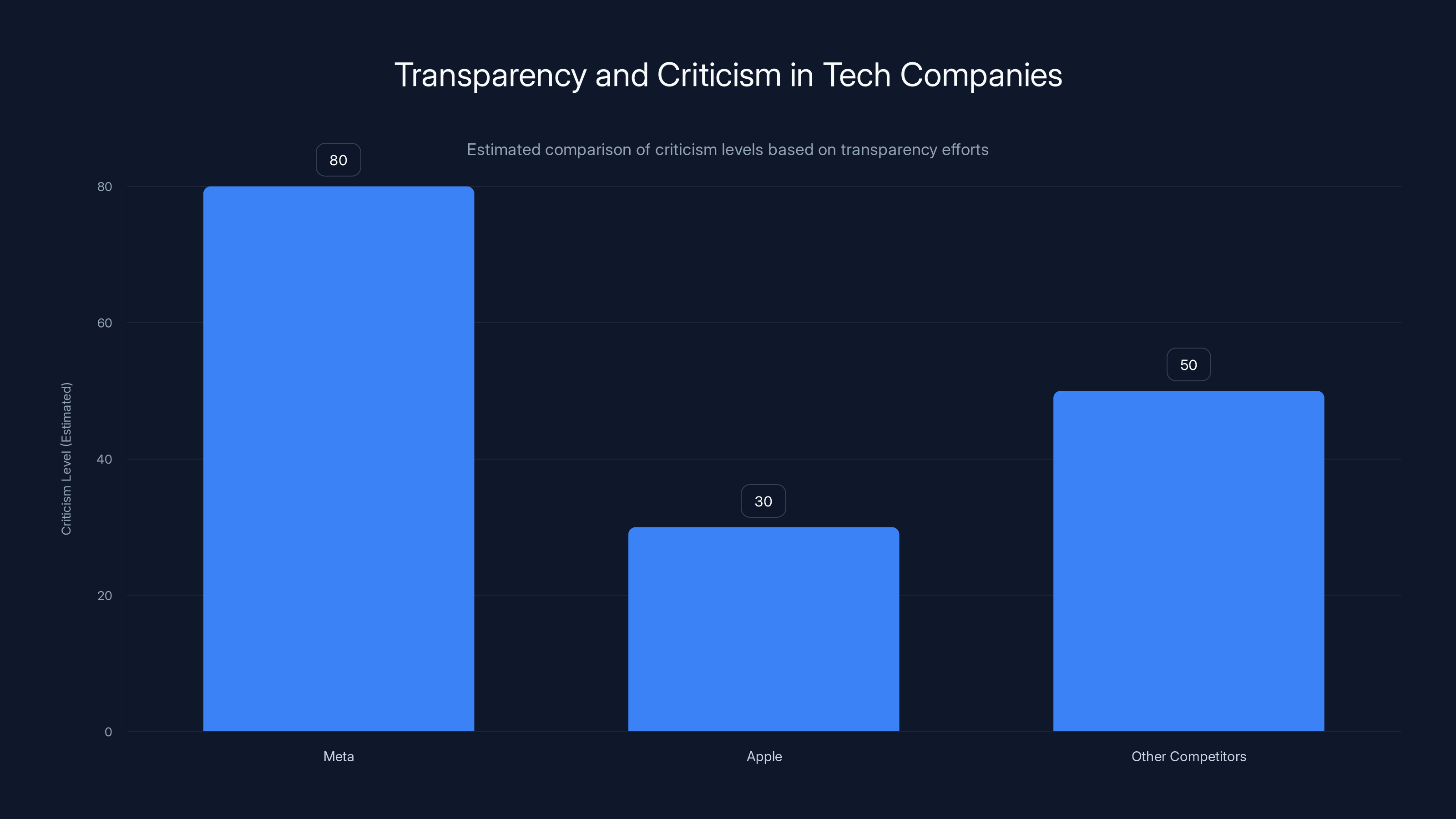

Zuckerberg's core argument in the email was surprisingly simple: transparency is a trap. He observed that Meta seemed to get more criticism precisely because it was researching and reporting on harms. Meanwhile, competitors like Apple managed to avoid similar criticism by doing essentially nothing.

"Apple, for example, doesn't seem to study any of this stuff," Zuckerberg wrote. "As far as I understand, they don't have anyone reviewing or moderating content and don't even have a report flow in iMessage."

This observation cuts to the heart of a perverse incentive in tech governance. If a company conducts rigorous research on the harms its platform causes, that research becomes discoverable in litigation. It can be used against the company in court. It can be cited by regulators. It can be leaked to journalists. It becomes evidence of knowledge and negligence.

But if a company simply chooses not to study these questions carefully, it can argue that it lacked knowledge of any problems. It can claim ignorance as a defense. From a purely defensive legal and reputational standpoint, not knowing is better than knowing.

Zuckerberg pointed to Apple's 2021 announcement about scanning iCloud Photos for child sexual abuse material (CSAM). Apple faced immediate backlash from privacy advocates who argued the system could be repurposed for mass surveillance. Apple later shelved the program. The irony wasn't lost on Zuckerberg: when Apple tried to do something about harm on its platform, it got criticized. When Apple did nothing, it avoided scrutiny entirely.

The email also addressed what Zuckerberg saw as Meta's unique vulnerability. Because Meta conducts extensive research on harms and actually reports findings (at least internally), and because its content moderation policies are more active than competitors', it appears to have more problems. "We faced more criticism because we report more CSAM," he wrote, "which makes it seem like there's more of that behavior on our platforms."

It's a frustrating observation for Zuckerberg: doing more to address problems actually makes those problems more visible. A company that actively reports child abuse is seen as complicit in child abuse. A company that pretends not to have these systems at all avoids the criticism entirely.

Estimated data shows that 32% of teenage girls reported feeling worse about their bodies after using Instagram, highlighting significant mental health concerns.

The Competitor Comparison: How Other Tech Giants Avoid Accountability

Zuckerberg's email didn't stop with Apple. He systematically compared Meta's approach to research with that of YouTube, Twitter, and Snapchat—companies that, in his view, took more passive approaches to understanding and addressing harms on their platforms.

"YouTube, Twitter and Snap take a similar approach, to lesser degrees," he noted. The implication was clear: these companies had discovered the same strategic truth that Apple had: less research equals less accountability.

This comparison reveals something crucial about how the tech industry actually functions behind closed doors. While these companies may appear to take different policy approaches in public, Zuckerberg's perspective suggests they're following similar playbooks when it comes to internal research.

YouTube, owned by Google, is perhaps the most relevant comparison. Like Meta, YouTube hosts billions of hours of user-generated content. It's rife with harmful material, from misinformation to child exploitation content to radicalization pipelines. Yet Google doesn't publish nearly as much research on YouTube's harms as Meta does about Facebook and Instagram. This wasn't an accident—it was strategy.

Twitter, before its acquisition by Elon Musk, similarly avoided extensive internal research on platform harms. The company would occasionally commission outside researchers, but it didn't maintain the vast internal research infrastructure that Meta did. Twitter faced less regulatory scrutiny than Meta, at least partly because there was less internal documentation of what it knew about the platform's problems.

Snapchat, the smallest player in this comparison, has historically published almost nothing about harm research. The company maintained an image as a more private, ephemeral platform with fewer content moderation concerns, at least in public perception.

Zuckerberg's real insight wasn't about the quality of these platforms or their actual safety. It was about the legal and reputational incentives. Companies that don't study harms don't have to disclose those studies. They're not vulnerable to having their own research used against them. They can plausibly claim ignorance if and when a lawsuit comes.

Meta, by contrast, had created an enormous paper trail documenting what it knew about Instagram's effects on teen mental health, the spread of misinformation, the ability of predators to exploit young users, and dozens of other harms. Every memo, presentation, and research finding was potentially discoverable evidence.

Meta's research found that 32% of teenage girls felt worse about their bodies after using Instagram. Estimated data for 'No Change' and 'Felt Better' categories.

The Frances Haugen Leak: Transparency as Litigation Risk

The timing of Zuckerberg's email is crucial to understanding what he was responding to. The Wall Street Journal's story that prompted his reflection wasn't based on Meta's public statements or published research. It was based on internal documents leaked by Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager who had methodically copied thousands of documents before leaving the company.

Haugen had been a true believer in Facebook's mission. She joined as a junior PM and worked on ranking algorithms and content distribution systems. But as she learned more about the research the company had conducted—research that showed how these systems were harming teenage girls, destabilizing democracies, spreading dangerous misinformation—she became convinced that Facebook needed to fundamentally change.

When the company refused, Haugen did something extraordinary. She compiled thousands of documents—all of them Meta's own internal research—and systematically leaked them to the Wall Street Journal. The resulting series of stories, collectively known as the "Facebook Papers," became some of the most significant tech journalism in years.

What made these leaks so devastating wasn't that they revealed information Meta was hiding from the public. It was that they revealed information Meta was hiding from itself—or more accurately, choosing not to act on despite knowing it.

The research showed that Instagram's algorithm, designed to maximize engagement, was systematically promoting content that made teenage girls feel worse about their bodies. The company's own researchers had flagged this. The company's own internal metrics showed the problem getting worse. And yet, instead of addressing the root issue (the engagement-maximizing algorithm itself), Meta made minor tweaks to the user experience—recommendations for mental health resources, for instance—that did little to address the fundamental problem.

Zuckerberg's email can be read as his response to this crisis. The leak had transformed Meta's internal research from a private strategic advantage into public evidence of the company's knowledge of harms. What had previously been confidential deliberations about tradeoffs were now documented in the public record.

For a CEO, this is a nightmare scenario. Not because the company is uniquely bad, but because all companies have these conversations. All platform companies know about the harms their platforms cause. All tech executives face the same tension between engagement (which drives revenue) and harm reduction (which reduces engagement). The difference is that most companies don't have as much internal documentation of this tension.

Meta, because it had invested heavily in research infrastructure, had created exactly the kind of paper trail that plaintiffs' lawyers dream about.

The New Mexico Case: When Internal Documents Become Evidence

The New Mexico Attorney General's case against Meta, which brought these emails into public view, alleges something specific: that Meta deliberately misled parents and regulators about the safety of its platforms for teenagers, despite knowing that design choices were harmful.

The complaint argues that Meta made public statements proclaiming its platforms "safe" for teens while internally acknowledging the opposite. The company knew about the mental health effects. It knew about predatory behavior enabled by its algorithms. It knew about exposure to eating disorder content and self-harm material. And yet its public messaging suggested these concerns had been addressed or that they were manageable through minor features like parental controls.

Zuckerberg's email fits perfectly into this narrative. Here's the CEO of the company, responding to the revelation of internal research showing harm, by asking whether Meta should change "how it studies its platforms' potential harms." The implication isn't subtle: maybe the problem isn't the harms themselves, but the fact that the company is studying and documenting them.

In discovery, these kinds of emails are toxic for defendants. A jury can read Zuckerberg's words and draw a conclusion: the CEO was worried that research into harms was hurting the company's reputation, so he was considering whether to stop doing that research.

It doesn't matter that Zuckerberg framed it as a strategic question about "approach" rather than an explicit decision to stop research. The jury can read between the lines. And the plaintiffs' lawyers will help them read very deliberately between those lines.

The email also matters because it shows consciousness of guilt. If Meta truly believed its platforms were safe, why would Zuckerberg be worried about the effects of studying potential harms? The very fact that he felt compelled to address this issue suggests he understood that the research revealed problems.

The Instagram algorithm significantly impacts teen mental health by promoting content that increases body image issues and engagement, while adjustments for user well-being remain minimal. Estimated data.

The CSAM Problem: Where Transparency Backfires

One of the most interesting parts of Zuckerberg's email involves his discussion of child sexual abuse material (CSAM). He observed that Meta "faces more criticism" because it "reports more CSAM," which "makes it seem like there's more of that behavior on our platforms."

This is genuinely frustrating from Meta's perspective, even if the underlying logic is perverse. If Meta has better detection systems and reports more CSAM to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), that's actually a sign the company is doing a better job. But from a PR standpoint, it makes Meta look worse.

Zuckerberg then pivoted to Apple's CSAM announcement: "When Apple did try to do something about CSAM, they were roundly criticized for it, which may encourage them to double down on their original approach."

Apple's 2021 proposal was genuinely controversial. The company proposed client-side scanning of iCloud Photos, which would scan files on users' devices before they were uploaded to Apple's servers. The system would be able to detect known CSAM images using a hash database. The privacy implications were enormous, and Apple ultimately shelved the plan after intense criticism from privacy advocates and technologists.

But Zuckerberg's observation misses an important distinction. Apple was criticized for the method it proposed (client-side scanning), not for trying to address CSAM at all. The criticism was specific: this particular technical approach created unacceptable privacy risks that could be repurposed for surveillance.

Zuckerberg seemed to interpret the criticism as a general warning against doing anything about CSAM. His conclusion was that the lesson Apple should take away is: don't try to address these problems because you'll face criticism anyway.

This reveals something about how Zuckerberg (and presumably others in the tech industry) process criticism. They see it not as feedback on specific technical approaches, but as a sign that any effort in a given direction will backfire. Better to avoid the space entirely.

The Privilege Question: Should Research Be Confidential?

Zuckerberg's email had a subject line that's worth examining: "Social issue research and analytics—privileged and confidential." The use of the word "privileged" isn't accidental. It's a legal term.

In American law, attorney-client privilege protects communications between lawyers and clients from being disclosed in litigation. There's also work product privilege, which protects materials prepared by a lawyer in anticipation of litigation. Companies often claim that internal research and deliberations are protected by these privileges if they were created at the direction of in-house counsel or with litigation in mind.

By marking the email "privileged and confidential," Zuckerberg was attempting to protect it from discovery in future lawsuits. The theory would be that this was a confidential communication about legal strategy, and therefore shouldn't be discoverable.

But here's the problem: the email is about business strategy, not legal strategy. It's Zuckerberg asking whether Meta should change how it does research. While it touches on legal implications, it's fundamentally a business decision, not a legal one. Courts have consistently held that claiming privilege doesn't work when a document is about business strategy, even if it was sent to or discussed with lawyers.

The unsealing of this email suggests the court didn't buy Meta's privilege argument. The document was deemed discoverable, and now it's part of the public record in the New Mexico case.

This has significant implications for how tech companies approach internal deliberations about harm. If you write an email discussing whether your company should research potential harms, and that email gets dragged into litigation, that's devastating evidence. It doesn't matter whether you wrote it to a lawyer or a business executive. The content alone is damaging.

Estimated data suggests that mental health effects and exposure to harmful content are significant concerns in Meta's platform for teens.

The Broader Pattern: Institutional Ignorance as Strategy

What's remarkable about Zuckerberg's email is how clearly it lays out a strategic choice that's becoming increasingly common in tech: institutional ignorance.

The logic is: if we don't study it carefully, we can't know about it. If we can't know about it, we can't be held liable for it. If we can't be held liable for it, we can avoid the costs of fixing it.

This isn't unique to Meta. It's an industry-wide pattern. Google has resisted calls for transparent research on YouTube's recommendation algorithm. Amazon has minimized research on algorithmic bias in its hiring systems. Microsoft has been cautious about publishing research on potential harms from its language models.

Why? Because research creates documentation. Documentation creates liability. Liability creates costs.

Companies that want to avoid these costs have learned that the safest strategy is to not look too closely at what their systems are doing.

It's worth noting that this strategy works—at least in the short term. Companies that don't publish much research on their platforms' harms do face less regulatory pressure and fewer lawsuits than companies that do. Meta's willingness to research and document harm has made it a target for regulators and plaintiffs' lawyers in ways that YouTube or Twitter (at least historically) haven't faced.

But this strategy is unstable. Eventually, external researchers, whistleblowers, or leaked documents will reveal what the company was too cautious to study. And when that happens, the revelation is even more damaging because it's accompanied by the implication that the company knew it should study these questions but chose not to.

It's a version of the paradox that Zuckerberg didn't fully grapple with in his email: transparency about knowing about harm is better than being exposed for avoiding knowledge of harm. At least with transparency, you can argue you're trying to address the problem. With willful ignorance, you're just ignoring it.

The Teen Mental Health Crisis: What the Research Actually Showed

To understand why Zuckerberg's email matters so much, it's important to understand what the underlying research actually revealed. This wasn't vague speculation about social media's effects on teens. This was specific, quantified data from Meta's own systems about real harms.

The research that Frances Haugen leaked showed that Instagram's algorithm was uniquely effective at promoting content that made teenage girls feel bad about their bodies. The algorithm didn't do this by accident. It did it because that content drove engagement—likes, comments, shares—and engagement is what Meta's systems are designed to maximize.

The algorithm learned that content showing impossibly beautiful women in perfect outfits, with perfect bodies, in perfect settings, generated enormous engagement. And so it showed more of that content to teenage girls who were most interested in fashion and fitness. The algorithm had essentially created a feedback loop: show content that triggers body insecurity and shame, which increases engagement, which trains the algorithm to show even more of that content.

Meta's own researchers had flagged this dynamic. But fixing it would require changing the algorithm itself—reducing the weight of engagement metrics, perhaps prioritizing user well-being over engagement. That would reduce Meta's ad revenue, which is ultimately what Instagram is designed to maximize.

So instead of fixing the fundamental problem, Meta applied band-aids. It added features like "Take a Break," which prompts users to step away from Instagram after they've been on it for a while. It added resources for users struggling with eating disorders. It adjusted the algorithm slightly to reduce the promotion of ultra-thin body imagery.

None of these measures addressed the core issue: Instagram's algorithm is optimized for engagement, not well-being, and those optimization metrics are fundamentally at odds when it comes to mental health.

Apple scores higher in privacy focus and regulatory advantage due to minimal content moderation and internal research, while Meta excels in content moderation and research but faces greater regulatory challenges. Estimated data.

The Ripple Effect: Why This Email Matters Beyond Meta

Zuckerberg's email isn't just significant because it reveals Meta's internal thinking. It's significant because it establishes a pattern that regulators, lawmakers, and the public can point to across the entire tech industry.

Other tech companies have undoubtedly had similar conversations. CEOs at YouTube, TikTok, Snapchat, and other platforms have surely discussed the strategic costs and benefits of research. But most of them have been more careful about documenting these conversations. Meta's paper trail gives us a rare glimpse into how these strategic calculations actually happen at the highest levels of tech companies.

The email has already been cited in multiple regulatory and legislative contexts. State AGs in other jurisdictions are using it as evidence that big tech companies deliberately hide research on harms. Lawmakers pushing for stronger regulation can point to Zuckerberg's words as proof that transparency requirements are necessary—because companies won't voluntarily share what they know.

The email also matters because it challenges a common defense that tech companies use: "We didn't know that our products were causing this harm." Zuckerberg's email, combined with the research itself, shows that this defense isn't credible for Meta. The company knew. It studied the harms extensively. And it chose to implement band-aid solutions rather than fundamental changes.

That's potentially worse than ignorance from a liability standpoint. Ignorance might be a defense. But knowledge combined with failure to act is negligence.

The Legal Exposure: What the New Mexico Case Could Mean

The New Mexico case that brought these emails to light isn't an isolated action. Similar cases have been filed by AGs in California, Florida, and other states. They all make similar arguments: Meta knew its platforms were harmful to teens and misrepresented them as safe anyway.

If Meta loses these cases, the financial consequences could be severe. State AGs are seeking penalties that could reach billions of dollars. More importantly, they're seeking injunctions that would force Meta to change how it designs its platforms—to prioritize user safety over engagement, for instance.

Zuckerberg's email would be presented as key evidence that Meta knew better. Here's the CEO of the company, in September 2021, explicitly acknowledging that the company had research showing harms and wondering whether to change how it studied those harms. If that's not consciousness of guilt, plaintiffs' lawyers would argue, what is?

The email also matters in the context of Meta's public statements. During the same period, Meta was making public claims about its commitment to teen safety. The company published blog posts about new teen account features. It announced parental controls. It commissioned outside research to suggest that Instagram wasn't uniquely harmful to teens.

Meanwhile, internally, Zuckerberg was asking whether Meta should reduce its research on harms. The contrast between public statements and private deliberations is exactly what plaintiffs' lawyers use to prove deception.

Estimated data suggests that companies like Meta, which engage in transparency and research, face higher criticism levels compared to those like Apple, which do not publish similar research.

The Competitor Comparison Revisited: Apple's Strategic Advantage

Zuckerberg's observation about Apple deserves deeper examination because it reveals something important about how regulation and oversight actually work.

Apple's approach to content moderation and harm research is fundamentally different from Meta's. Apple largely doesn't moderate content on its platforms. The company positions itself as a privacy-first company that doesn't monitor what users do with their devices or services. As a result, Apple doesn't have the same paper trail of internal research that Meta does.

This is genuinely an advantage from a regulatory perspective. Without that research, regulators can't point to Apple's own data showing harm. Plaintiffs can't cite internal memos where Apple acknowledged problems.

But there's a cost to this approach. It means Apple doesn't actually know—or at least, doesn't systematically document—what's happening on its platforms. That lack of knowledge might be a legal defense, but it's not actually better for users. If Apple isn't studying potential harms, it's not addressing them either.

Zuckerberg seemed to understand this dynamic. He recognized that Apple's strategy (do minimal research, claim minimal responsibility) was working better politically and legally than Meta's strategy (do extensive research, take responsibility for addressing issues). The question he was grappling with, implicitly, was whether Meta should adopt Apple's approach.

This reveals the perverse incentive structure in tech regulation. The company that's most transparent about harms gets punished. The company that claims ignorance avoids liability. From a pure business standpoint, ignorance is profitable.

But from a user safety perspective, this is backwards. We want companies to study potential harms. We want them to have robust research operations. The legal and reputational risks shouldn't be the cost of knowing about your product's effects.

The Research Suppression Problem: Is Zuckerberg Actually Proposing Less Research?

It's worth pausing here to ask: what exactly was Zuckerberg proposing when he wrote about changing Meta's "approach to research and analytics around social issues"?

He wasn't explicitly saying "stop researching harms." He was asking whether the company should change its approach. The email itself doesn't spell out what that new approach would be.

Meta's defense, in the New Mexico case and elsewhere, is that Zuckerberg never actually implemented any change to research operations. Meta continued studying potential harms on its platforms. It continued publishing findings. The company is arguing that this email was just a moment of reflection, not a decision to suppress research.

There's something to this argument. An email discussing whether to change policy isn't the same as actually changing policy. We don't have evidence that Zuckerberg issued orders to reduce research efforts.

But the email is still damaging because it shows the CEO explicitly worried about the strategic costs of research. That's consciousness that research was becoming a liability. Even if the company didn't formally change its research operations, the email shows that the leadership was thinking about whether it should.

Moreover, the tone of the email is concerning. Zuckerberg seemed to be looking for validation for his worry. He was pointing out that competitors were doing less research. He was noting that this gave them a strategic advantage. The subtext is clear: shouldn't Meta consider doing the same?

The Broader Question: When Does Knowledge Become Responsibility?

Underlying all of this is a deeper question that goes beyond Meta specifically: when a company conducts research showing its product causes harm, what responsibility does that create?

There are several possible frameworks:

The strict liability framework would say: if you know harm is happening, you're responsible for it. You must address it, even if addressing it reduces profitability. This is roughly how we treat pharmaceutical companies—if a drug causes harm, the company is liable even if the harm was unforeseen.

The negligence framework would say: you're responsible if you knew about harm and failed to act reasonably to address it. You don't have to eliminate harm entirely, but you have to make good-faith efforts proportional to the severity of the problem.

The caveat emptor framework would say: the company has no special responsibility. It's up to users, parents, and regulators to make their own decisions about whether the product is safe. The company's job is to sell the product, not to prevent all possible harms.

Different legal systems and different judges weight these frameworks differently. But the trend in recent years has been moving toward some version of the negligence framework: companies that know about potential harms have a responsibility to address them proportionally.

Zuckerberg's email is important because it suggests Meta understands this framework and is trying to game it. If the company can avoid knowing about harms, it can avoid responsibility. If it must know about harms (because users or external researchers keep revealing them), then it should at least be careful about documenting that knowledge, because documentation creates liability.

This is a rational response to the incentive structure. But it's also a response that harms users. It means companies are motivated to not study potential problems. It means problems go unaddressed longer. It means vulnerable populations (like teenage girls) suffer preventable harms.

The Teen Mental Health Crisis: What Happened After the Leaks

It's worth tracking what actually happened after the Frances Haugen leaks and Zuckerberg's email. Did Meta change course? Did it fundamentally alter how Instagram works to prioritize teen mental health?

The answer is: not really.

Meta did implement some new features. The "Take a Break" feature would remind users to step away from Instagram after a certain amount of time. The company adjusted the algorithm to reduce the promotion of ultra-thin body imagery. It created more parental controls so parents could monitor their teens' Instagram use.

But the core algorithm remained unchanged. Instagram still optimizes for engagement. It still uses machine learning to figure out what content keeps users scrolling. It still recommends accounts that it predicts will drive high engagement, even if that means recommending accounts that promote disordered eating or other harmful behaviors.

In other words, Meta applied band-aids to a systemic problem. The underlying issue—that the platform's engagement-maximization algorithm is fundamentally at odds with teen mental health—remained unaddressed.

This isn't unique to mental health. It's true across the board. Meta has made various adjustments to reduce misinformation spread, hate speech, and other harms. But the fundamental architecture of the platform—designed to maximize engagement and ad revenue—hasn't changed.

Zuckerberg's email actually predicted this outcome. He noted that Meta "faced more criticism" than competitors precisely because it was researching and addressing harms while competitors did minimal research. If Meta fundamentally changed the algorithm to prioritize safety over engagement, the platform would become less addictive, fewer people would use it, and Meta's ad revenue would drop.

From a business perspective, that's unacceptable. From a user perspective, that's exactly what's needed.

The Regulatory Response: What Lawmakers Are Doing With This Information

Zuckerberg's email has become ammunition for regulators and lawmakers who want to push for stronger rules around tech companies' responsibilities.

Several state attorneys general have cited the email as evidence that the Protect Kids Online Act (a proposed bill that would impose specific obligations on social media platforms) is necessary. The argument is straightforward: companies won't voluntarily change their practices to prioritize teen safety. They'll continue optimizing for engagement unless they're forced to do otherwise.

The email also features prominently in arguments for a right of discovery for the FTC. Regulatory agencies want the power to subpoena internal documents from tech companies and examine what they know about potential harms. Zuckerberg's email is exactly the kind of document that would be valuable in those investigations.

At the federal level, lawmakers have proposed bills that would specifically address the gap between internal knowledge and public responsibility. Some proposals would require companies to study potential harms and publicly report findings. Others would impose liability for harms that companies knew about or should have known about.

The concern among tech companies is that these rules would create perverse incentives: if companies know that research will be discoverable and create liability, they might respond by doing less research. That's the exact concern Zuckerberg's email raises.

But that's also why regulators want to close the loophole. They want to make sure that the incentive structure points toward more transparency and responsibility, not less.

The Platform Accountability Debate: Competing Frameworks

Zuckerberg's email sits at the center of a larger debate about how we should think about platform accountability. There are a few competing frameworks worth understanding:

The platform-as-publisher framework treats social media platforms like traditional media companies. Under this view, platforms are responsible for the content they distribute, similar to how newspaper editors are responsible for the articles they publish. This would give platforms strong incentives to moderate content aggressively and to know what's being distributed on their services.

The platform-as-infrastructure framework treats social media platforms like telephone companies. Under this view, platforms are neutral conduits for user speech. They shouldn't moderate content, and they shouldn't be held responsible for what users do with their services. This would give platforms almost no responsibility for harms.

The platform-as-business framework, which is sort of the default position, treats platforms like any other business. They're responsible for harms they deliberately cause, or that they negligently fail to prevent, but they have no responsibility for harms they couldn't reasonably foresee.

Zuckerberg's email reveals tension between these frameworks. Meta acts somewhat like a publisher—it moderates content, it studies harms, it makes decisions about what to recommend. But it also claims the protections of the infrastructure framework—it's just a neutral conduit, users choose what to engage with. And it wants the lack of responsibility of the business framework—we can't be expected to prevent all possible harms.

What Zuckerberg's email suggests is that Meta wants the benefits of all three frameworks without the costs of any of them. It wants to moderate content aggressively (because that drives engagement), but not be held responsible for the results. It wants to study harms (because that helps it optimize the platform), but not have to address them (because that would reduce engagement and revenue).

The legal and political battles over platform accountability are, in many ways, battles over which framework wins. And the evidence in Zuckerberg's email will be crucial to those battles.

The Institutional Knowledge Problem: When Companies Know Too Much

Zuckerberg's email also raises an interesting institutional question: is it actually bad for companies to study potential harms?

From a purely internal business perspective, the answer might be yes. If you study harms, you create documentation of those harms. If you have documentation, you create legal liability. From a risk management perspective, not studying harms looks attractive.

But from a user perspective, the answer is clearly no. More research means better understanding of harms. Better understanding means better ability to address harms. Users benefit when companies study what their products are doing.

The current legal and regulatory system creates perverse incentives where companies benefit from not studying harms. That's a problem we need to solve, but it's a harder problem than it sounds.

One approach would be to offer companies some shield from liability if they conduct robust research on potential harms and make good-faith efforts to address them. The idea would be that transparency and effort would reduce liability exposure, making research attractive instead of unattractive.

Another approach would be to separate the knowledge-gathering function from the liability function. Maybe companies would be required to research potential harms, but internal research findings wouldn't be discoverable in litigation if the company made good-faith efforts to address them. That would reward transparency and harm reduction while not punishing companies for knowing about problems.

Both of these approaches face implementation challenges and could have unintended consequences. But they're the kinds of frameworks we need to think about if we want to create incentives for companies to study and address harms rather than hide from them.

The Future of Tech Accountability: What Comes After Zuckerberg

Zuckerberg's email won't be the last such document. Similar emails, memos, and presentations will emerge from other companies as more lawsuits proceed through discovery. Eventually, we'll have a fuller picture of how tech companies actually think about harms and accountability.

What will be interesting to see is whether other companies have been smarter about covering their tracks. Did they avoid documenting their knowledge? Did they separate research from business operations to create some legal distance? Did they use external researchers to shield internal deliberations from liability?

Some companies may have. But eventually, whistleblowers, regulators, and leaked documents will reveal what was actually happening inside these companies. The era of corporate opacity is ending, not because companies have become more transparent, but because the cost of opacity (in legal liability, regulatory scrutiny, and public trust) has become too high.

Zuckerberg's email is just the beginning. The real reckoning will come when we have comprehensive documentation of what tech companies knew about their products' harms, when they knew it, and what they chose to do about it.

The question facing Meta, and the broader tech industry, is whether they'll learn the right lesson from Zuckerberg's email. The wrong lesson would be to become more careful about documenting knowledge, to hide research deeper, to separate internal deliberations from liability exposure. That would make things worse, not better.

The right lesson would be to recognize that the incentive structure needs to change. Companies should be rewarded for transparency, for studying harms, for making genuine efforts to address problems. The legal system should create frameworks where knowing about harms and trying to address them actually reduces liability exposure, not increases it.

Until that happens, companies will continue to face pressure to hide what they know. And users will continue to be harmed by products that companies understand are harmful but have no financial incentive to fix.

Zuckerberg's email reveals the system as it actually works, stripped of PR spin and strategic messaging. It shows a CEO wrestling with how to balance user welfare against business interests, and ultimately choosing business interests. It shows a company with knowledge of harms choosing to document some of those harms while doing minimal actual remediation.

It's uncomfortable reading for anyone who believed tech companies were genuinely committed to user safety. But it's also important reading, because it shows exactly what we need to change to make the incentives right.

FAQ

What was the Wall Street Journal story that prompted Zuckerberg's email?

On September 14th, 2021, the Wall Street Journal published an investigation based on internal documents leaked by former Facebook product manager Frances Haugen. The story revealed that Meta's own research had found that 32% of teenage girls felt worse about their bodies after using Instagram. This documented evidence of platform harm directly prompted Zuckerberg's internal reflection about Meta's research strategy.

Why did Zuckerberg consider changing Meta's research approach?

Zuckerberg was concerned that Meta's transparent research on platform harms was creating legal and reputational liability. He observed that competitors like Apple avoided similar scrutiny by conducting minimal research on potential harms. His email suggests he wondered whether Meta should adopt a similar strategy of limited internal research to reduce documented evidence of problems.

How did these internal emails become public?

The emails were unsealed as part of discovery in the New Mexico Attorney General's case against Meta. The AG is alleging that Meta deliberately misled parents and regulators about platform safety despite internal knowledge of harms. Documents obtained during litigation discovery, including Zuckerberg's email, were made part of the public court record.

What does "privileged and confidential" mean in the context of Zuckerberg's email?

Zuckerberg marked his email "privileged and confidential" hoping to shield it from discovery in lawsuits by claiming attorney-client privilege. However, courts determined that the email was about business strategy, not legal strategy, and therefore wasn't actually privileged. The document was deemed discoverable and entered the public record.

What is the New Mexico case about?

The New Mexico Attorney General alleges that Meta engaged in deceptive practices by publicly claiming its platforms were safe for teens while internally knowing about harmful design features and effects on mental health. The case argues Meta failed to disclose research showing platform harms and made false claims about safety features. Similar cases have been filed by attorneys general in California, Florida, and other states.

How did Frances Haugen obtain these internal documents?

Frances Haugen was a product manager at Facebook who had access to internal research and corporate documents. Concerned that the company wasn't addressing harms it knew about, she systematically copied thousands of internal documents before leaving the company and leaked them to the Wall Street Journal, leading to the "Facebook Papers" series of investigations.

What does the email reveal about the tech industry more broadly?

The email suggests that across the tech industry, companies may be facing similar incentives to avoid transparent research on potential harms. Zuckerberg's observation that competitors do less research and face less scrutiny suggests this may be a systemic strategy, not unique to Meta. The email reveals how knowledge of harms can become a strategic liability rather than an asset for companies.

What are the potential consequences for Meta if the New Mexico case goes to trial?

If Meta loses, the company could face significant financial penalties reaching billions of dollars, plus court-ordered changes to how it designs its platforms. The email would be presented as evidence that Meta knew about harms and deliberately chose to misrepresent platform safety. Such a loss could set precedent for similar cases filed in other states.

How does this email relate to broader tech regulation debates?

The email has become key evidence in arguments for stronger tech regulation. Advocates point to it as proof that companies won't voluntarily prioritize user safety over profit maximization, and that legal requirements and enforcement mechanisms are necessary. The email is frequently cited in discussions about regulating algorithmic recommendation systems and mandating transparency about platform harms.

What changes has Meta made to Instagram's design since these revelations?

Meta introduced features like "Take a Break" (which prompts users to step away after extended use), adjusted algorithms to reduce promotion of ultra-thin body imagery, and created parental controls. However, the fundamental engagement-optimization algorithm that prioritizes time-on-platform remains unchanged, addressing symptoms rather than root causes of harm.

Key Takeaways

- Zuckerberg's unsealed email shows the CEO considering whether Meta should reduce research on platform harms—revealing how legal liability creates perverse incentives across tech

- Meta's transparent harm research created discoverable evidence used in litigation, while competitors doing minimal research faced less regulatory scrutiny

- The current legal system inadvertently rewards companies that know less about their products' harms and punishes those that research problems transparently

- Meta's band-aid solutions (parental controls, take-a-break features) addressed symptoms but left the core engagement-optimization algorithm unchanged

- Multiple state attorneys general are using these internal emails as evidence of deceptive practices in cases seeking billions in penalties and forced design changes

![Meta's Research Dilemma: Zuckerberg's Unsealed Emails Reveal Strategic Shift [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-research-dilemma-zuckerberg-s-unsealed-emails-reveal-/image-1-1770320358807.jpg)