Meta's VR Studio Closures: What This Means for Virtual Reality's Future

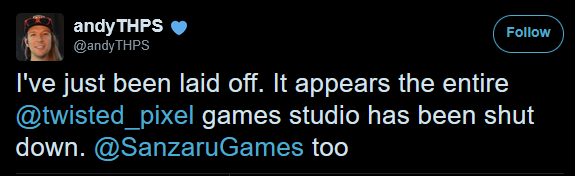

Last month, Meta did something it rarely does openly: admit that its metaverse bet wasn't paying off the way executives hoped. The company closed three of its most ambitious VR studios. We're talking about Armature, Sanzaru, and Twisted Pixel—studios that collectively shipped some of the most polished virtual reality experiences consumers have ever encountered.

But here's the thing that keeps people talking about this news: it's not just about three studios closing their doors. It's a watershed moment for the entire VR industry, one that forces us to ask uncomfortable questions about whether the metaverse narrative ever made sense in the first place.

The Studios Meta Shut Down and What They Built

Armature Studio: The Quest Port Experts

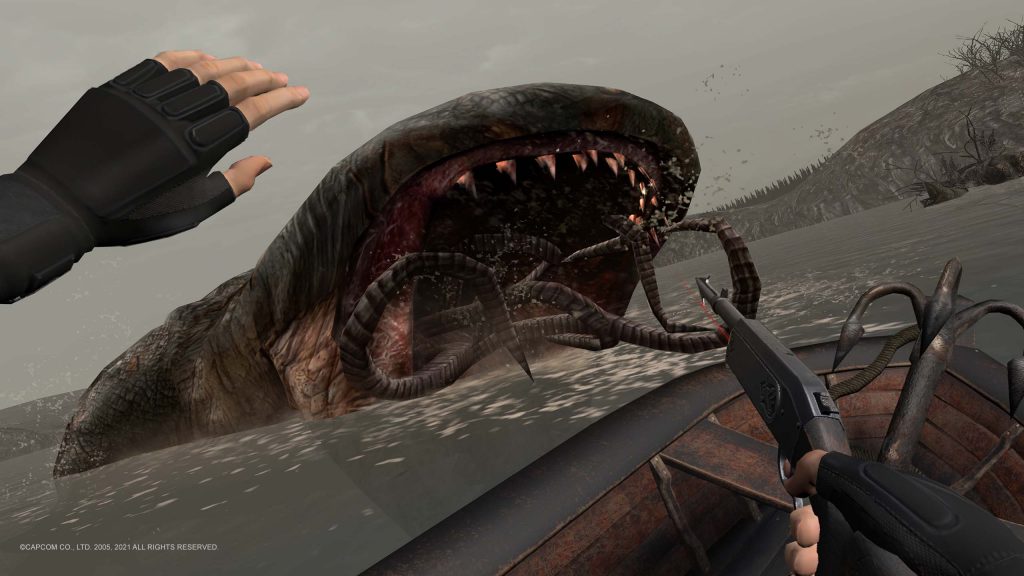

Armature wasn't some niche developer. The studio became synonymous with one specific, difficult task: bringing complex console games to Meta's Quest headsets without destroying what made them good. Their flagship achievement? Resident Evil 4 on Quest. Not a stripped-down mobile version. Not a tech demo. A legit, full-featured port of one of gaming's greatest titles. Released in 2021, it proved that Quest hardware could handle serious games. When you fired up RE4 in VR, you didn't feel like you were playing a compromised version. The headset got out of the way. Gameplay came first.

That matters because porting games is brutally hard. You're not just moving code from one platform to another. You're optimizing graphics, rethinking controls, squeezing performance out of less powerful hardware. Capcom trusted Armature with Resident Evil 4 because the studio had already proven it understood VR game design on a level that most developers simply didn't.

The closure of Armature means Quest users lose the studio that could credibly port AAA experiences. Yeah, other developers exist. But none of them had Armature's track record. This represents a specific, valuable capability leaving the VR ecosystem.

Sanzaru Games: The Asgard's Wrath Legacy

Sanzaru built one of the few VR games that genuinely deserved the label "must-play." Asgard's Wrath combined action gameplay, mythology, and technical ambition in ways that made VR feel special, not just novel.

The studio didn't chase quick cash grabs. They spent years building their game, and it showed. Asgard's Wrath felt like a complete experience, something you could sink 40+ hours into and feel satisfied. That's rare in VR. Most VR titles feel like experiences. Asgard's Wrath felt like a game.

What made Sanzaru different was their philosophy. They believed VR gaming deserved the same serious development resources as traditional gaming. They proved that bet with a title that still holds up today, years after launch.

Closing Sanzaru signals that Meta no longer wants to fund that kind of long-term, ambitious game development. The studio was producing genuine hits, not cash grabs. Yet Meta shut it down anyway.

Twisted Pixel: Marvel's Deadpool VR and the Entertainment Bridge

Twisted Pixel represented something different. This was a studio making big-IP VR experiences, not indie titles. Marvel's Deadpool VR launched in November 2024 to genuine critical acclaim. Players weren't saying "it's great for VR." They were saying "it's a genuinely fun game."

That distinction matters enormously. When a major entertainment company like Marvel commits to a VR game, it signals that the platform is mature enough for serious content. Twisted Pixel made that possible. They proved that blockbuster IP could translate to VR without feeling compromised.

The studio's closure comes just months after Deadpool VR shipped, meaning the team that built the game is now scattered. No sequel. No follow-up. Just a game that exists as a historical artifact of what could have been.

What's particularly telling: Twisted Pixel made the kind of VR experience that casual players might actually try. Deadpool has cultural cache outside gaming circles. His mom's friends know who Deadpool is. That crossover potential is almost gone now.

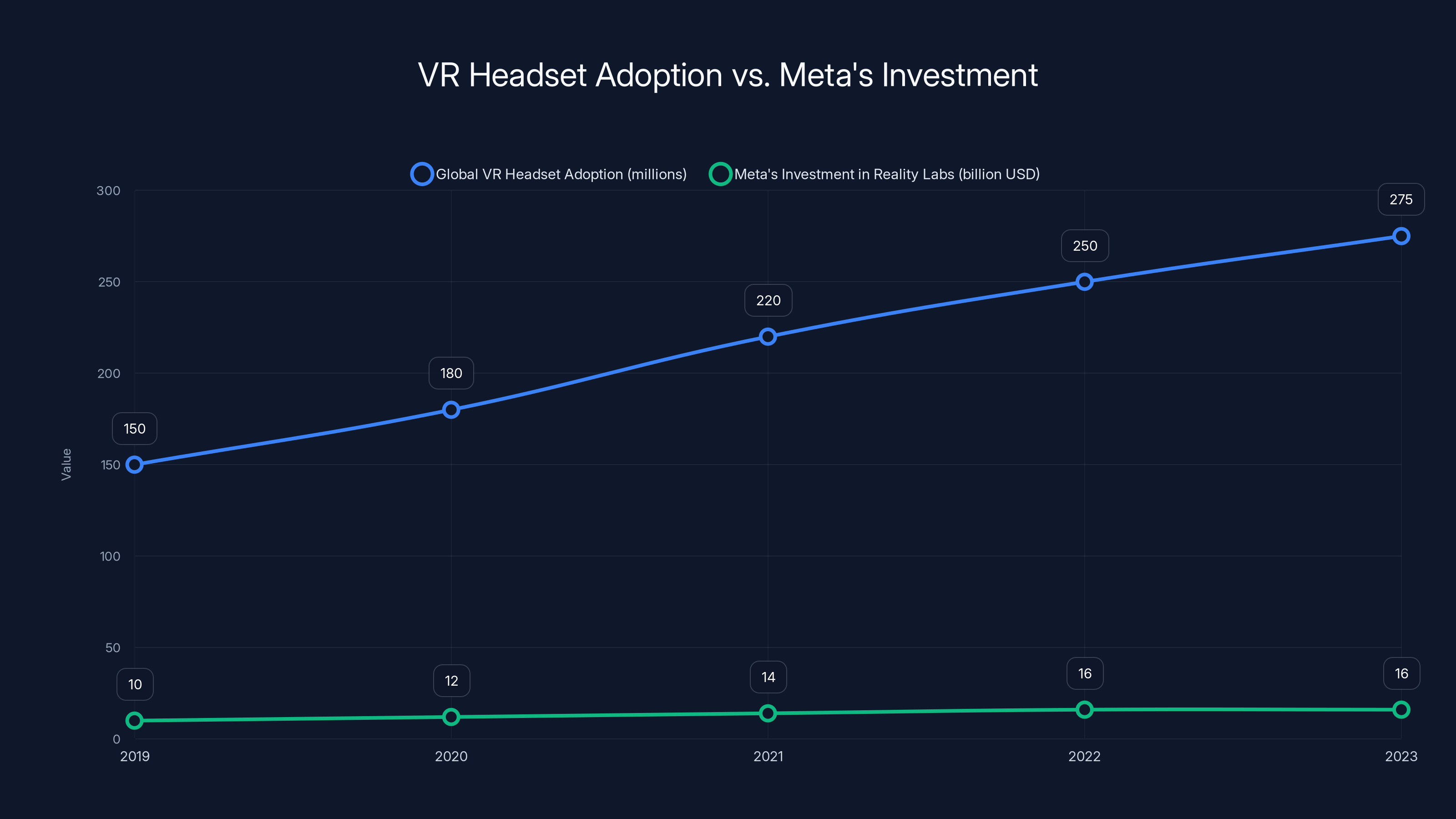

The chart shows that while global VR headset adoption grew steadily, Meta's investment in Reality Labs peaked at $16 billion annually without achieving the expected mass-market VR adoption. (Estimated data)

The Real Story: Meta's Metaverse Pivot

Meta's official explanation is clean and corporate: "We're shifting investment from Metaverse toward Wearables." That's technically true. But the actual story is messier and more interesting.

For years, Mark Zuckerberg bet the entire company on the metaverse. Not just some venture. The whole company. Reality Labs, Meta's division handling VR and AR, spent somewhere in the neighborhood of $16 billion annually. Every strategic decision pivoted around this vision where people would spend their digital lives in virtual spaces.

That didn't happen. More specifically, it didn't happen on the timeline anyone predicted. VR adoption plateaued around 200-300 million headsets globally—respectable, but nowhere near what would justify that level of investment for a company trying to compete with Apple and Google.

So what changed? Several things hit Meta simultaneously. First, they realized that building content (games, apps) costs a lot of money and takes forever. Second, they watched Apple release Vision Pro at $3,500 and realize that high-end spatial computing might not be a mass-market play for years. Third, they noticed that their Reality Labs division was hemorrhaging money with nothing to show for it.

The metaverse narrative cracked. It didn't shatter completely. Meta still believes in spatial computing. But they stopped pretending that expensive, long-term game development was the path forward.

Supernatural: Fitness Apps as the Overlooked Casualty

Maybe the most telling casualty in all of this is Supernatural—a VR fitness app that actually had real users, not just install numbers.

Here's what made Supernatural different: it wasn't trying to simulate a metaverse. It was a tool. You put on your headset, worked out for 30 minutes with a trainer guiding you through routines, and felt like you'd accomplished something. The app had a community. People subscribed. They showed up regularly.

This was one of Meta's few indisputable VR successes—a product with genuine retention and a business model. You'd think that would be safe from cuts. But Meta decided even profitable, successful apps don't fit the new strategy.

Supernaturally continuing to be supported at a maintenance level is almost worse than shutting down completely. Maintenance mode means new features stop, the app slowly becomes outdated, users drift away. It's a slow death rather than a quick one.

What kills you about Supernatural's fate is this: if Meta can't sustain an app that people actively use and pay for, what does that say about the metaverse? It's not a question anyone at Meta is answering directly.

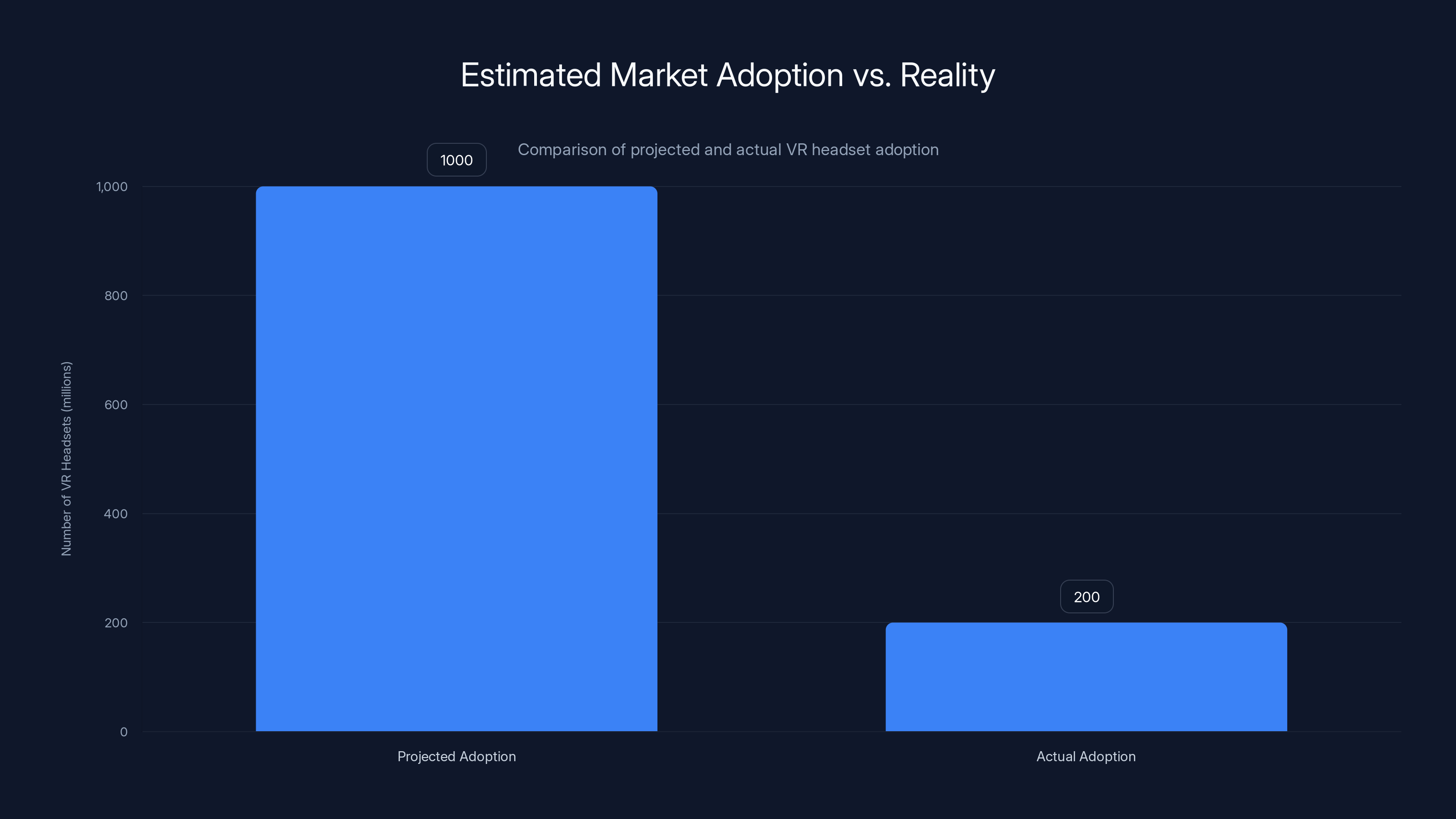

Estimated data shows a significant gap between projected and actual VR headset adoption, highlighting the risk of overestimating market growth.

The Broader VR Industry Impact

Talent Exodus and Industry Consolidation

When major studios close, their employees don't just evaporate. They go somewhere else. In the case of these Meta closures, some talented developers will move to other studios, but many will leave VR entirely.

This matters because VR development has always been niche. The talent pool is smaller than traditional game development. When three studios close simultaneously, you lose institutional knowledge about how to build VR games efficiently. That knowledge doesn't transfer easily to new studios.

Indie developers might benefit. Some of the people leaving Meta studios will start their own companies. But they'll also be less well-funded. The projects they can greenlight will be smaller and scrappier. The big-budget VR games that require sustained development? Those become harder to justify.

The Signal to Third-Party Developers

Meta's official line is that they're "shifting investment to focus on our third-party developers and partners." Here's what that actually means in practice: we're not funding your big games anymore, but please make games for us anyway.

That's a tough sell. Third-party developers look at what happened to Armature, Sanzaru, and Twisted Pixel and think: if this is what happens to Meta's own studios, why would we invest in building for Meta's platform? The economic logic breaks down.

You need something to pull developers to a platform. Apple has iOS's install base. Microsoft has Game Pass. Meta had money. Now Meta is pulling back on that money. The incentive structure that attracted serious developers to Quest just got a lot weaker.

Some developers will still build for Quest because it's a major VR platform and they need to. But the ambitious projects that push the medium forward? Those become questionable bets.

A Pattern of Strategic Retreats

The studio closures aren't happening in a vacuum. They're part of a broader pattern of Meta stepping back from its most ambitious VR plans.

The Horizon OS Pause

Just before announcing the studio closures, Meta "paused" its plans for Asus and Lenovo to release headsets running Horizon OS. These were supposed to be lower-cost alternatives to Meta's own Quest lineup, expanding the potential market.

The pause is interesting language. It suggests maybe they're coming back someday. But everyone in the industry knows that paused projects rarely restart. The companies would need new incentives to revisit the deal, and those incentives aren't currently present.

Why did this matter? Because it suggested Meta believed they could seed an entire ecosystem of manufacturers building VR hardware. That vision is dead now, even if Meta won't say so explicitly.

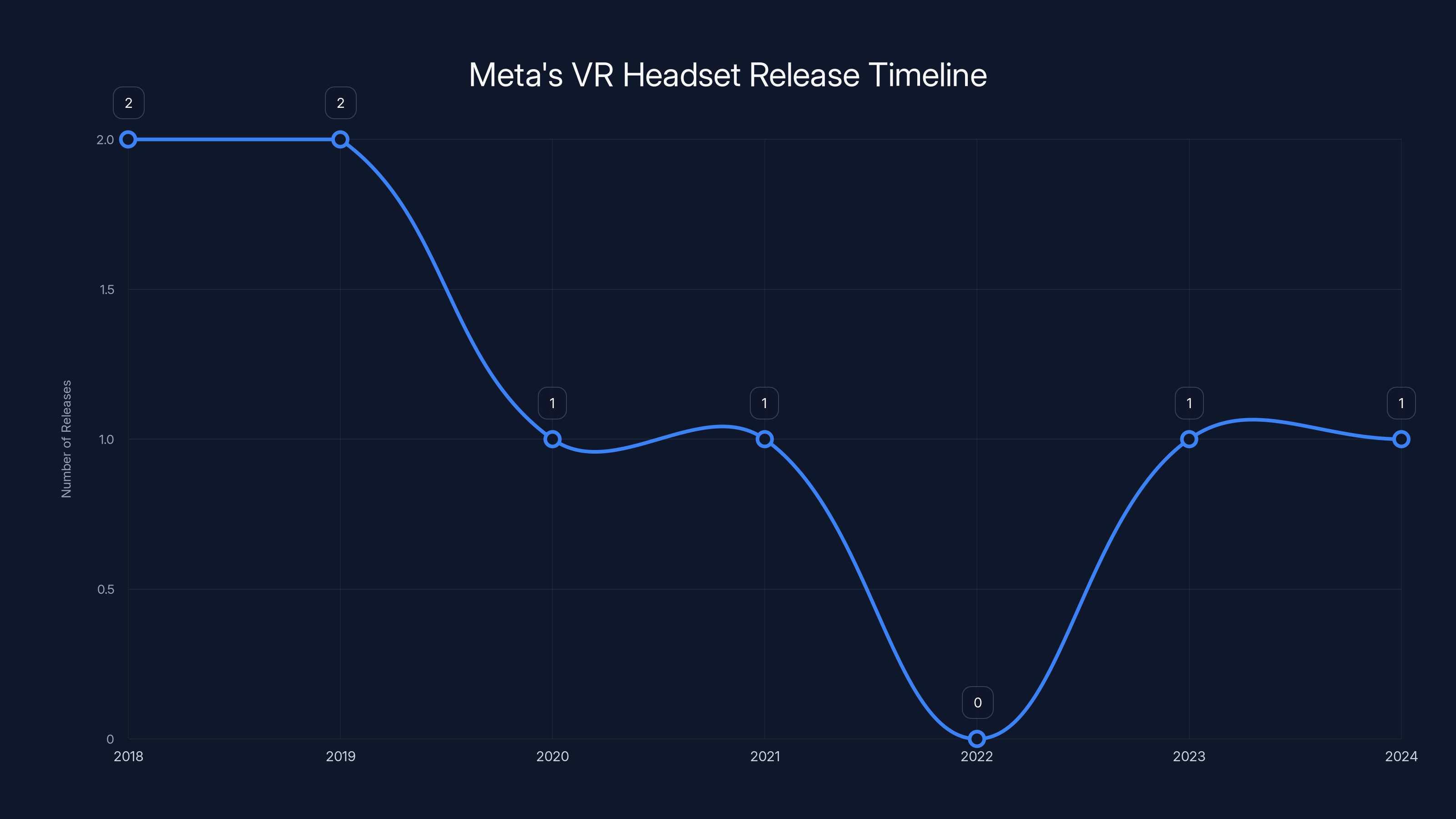

The Headset Release Drought

Meta's last meaningful headset release was the Quest 3S in 2024. Before that, the Quest 3. The company used to release new hardware more frequently. Now they're slowing down.

This is partially strategic—Quest 3S is good enough that there's no urgent need for a replacement. But it's also a symptom of Meta's reduced enthusiasm for VR. If you truly believed VR was the future of computing, you'd be iterating fast, pushing boundaries, releasing new hardware every 18 months. Instead, Meta's releasing new Quest models every few years and calling it good enough.

The message is clear: VR is a successful product line, but it's not a strategic priority anymore. It's maintained, not grown.

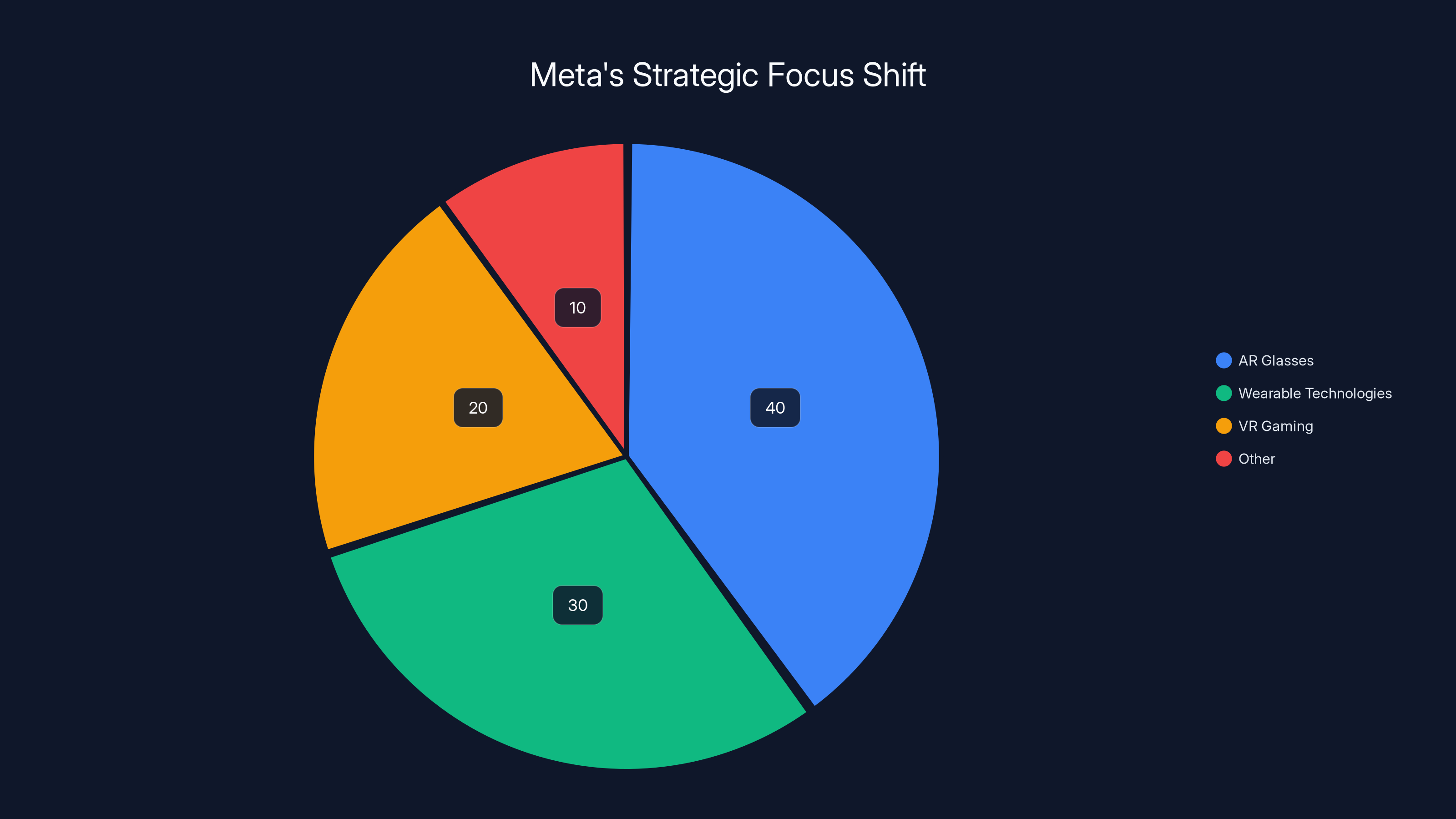

The Wearables Pivot: What Meta Actually Cares About Now

So if Meta's not doubling down on VR, what are they doing instead? Wearables.

Specifically, they're investing in AR glasses and wristband devices—technology that augments reality rather than replacing it. These are devices you wear alongside your normal life, not instead of your normal life.

This is actually a sensible pivot. AR has different economics than VR. You don't need a massive content library to justify owning AR glasses. People will wear them if they make daily life slightly better—directions overlaid on your vision, notifications without checking your phone, hands-free communication.

Meta's betting that wearables become ubiquitous before the metaverse does. That might be right. AR glasses are arguably closer to mainstream adoption than virtual worlds where everyone hangs out together.

But here's the strategic tension: wearables and VR are cannibalizing each other for development resources. Every engineer Meta reassigns to AR glasses is an engineer not building VR content. Every dollar spent on wearable research is a dollar not spent on VR games.

Meta has limited resources relative to the scope of what they're trying to accomplish. They're choosing to concentrate resources on wearables, which means VR gets deprioritized.

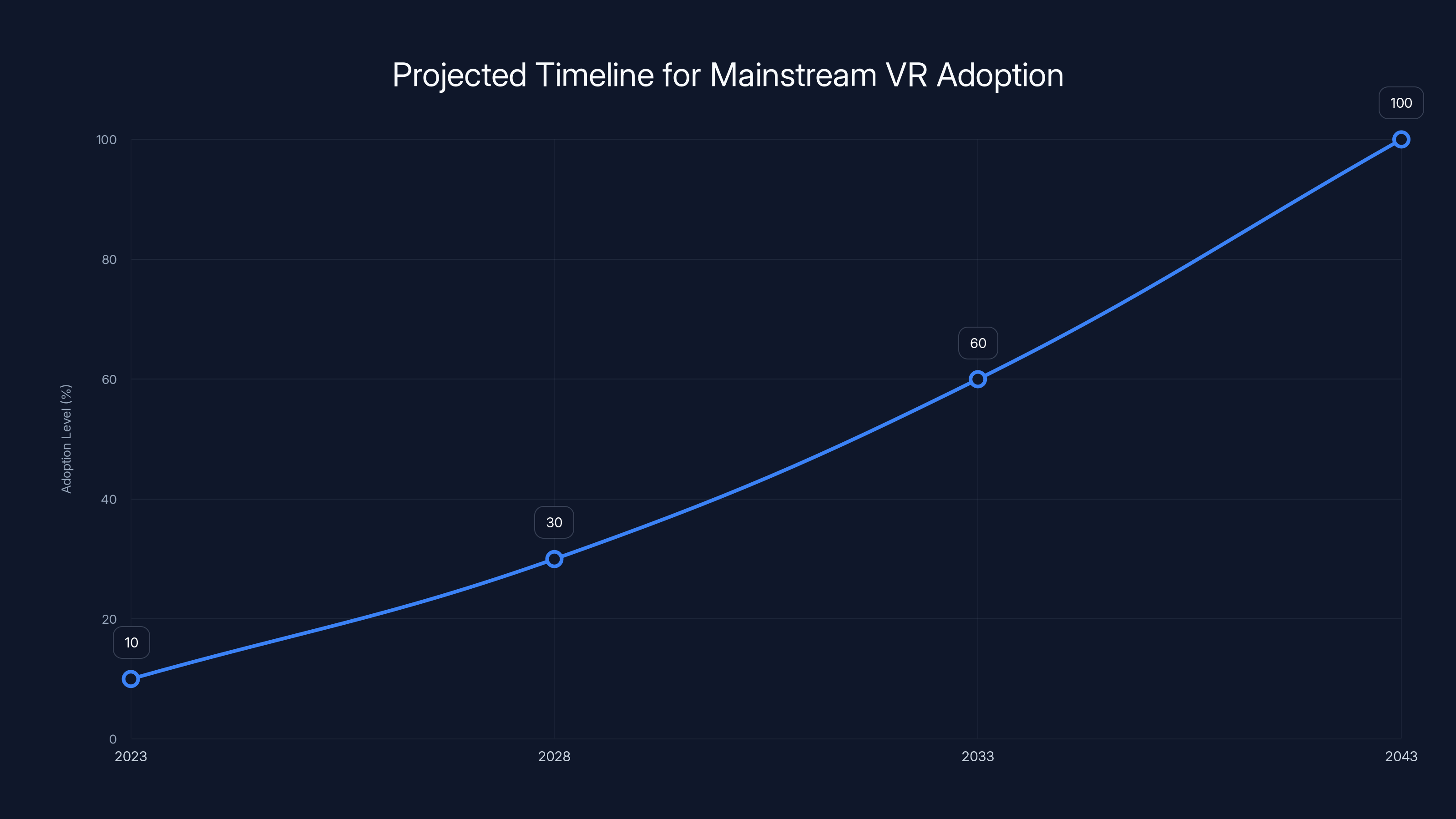

Estimated data suggests that VR could become mainstream in 20 years as hardware improves and prices drop.

What This Reveals About VR Market Maturity

The Content Problem Is Real

Meta spent billions trying to solve VR's core problem: there aren't enough quality games to justify owning a headset for most people. The plan was simple on paper—throw money at studios, develop great games, watch adoption soar.

It didn't work. The games Meta funded were good. Some were genuinely great. But they didn't drive mass-market adoption. People didn't buy Quest headsets in huge numbers because of Asgard's Wrath or Resident Evil 4. They bought them because they already liked VR or were curious enough to spend the money.

This suggests something uncomfortable: the content problem isn't solvable with money. You can't spend your way out of a chicken-and-egg situation where people won't adopt the platform until there's better content, but developing better content requires a larger user base to be profitable.

Meta's conceding that it can't solve this problem through internal game development. So they're pulling back. That's a significant admission.

Market Size Reality

Meta's cuts also signal something about their internal projections for VR market size. If they genuinely believed VR would become a $1 trillion industry, they'd be investing aggressively. The fact that they're cutting suggests their internal models show VR stabilizing at something much smaller.

Global VR headset shipments are expected to reach around 12 million units annually. That's healthy but not revolutionary. It's less than Apple watches, less than high-end gaming hardware, less than what you'd need to justify $16 billion annual spending.

So Meta's making a rational decision to invest less in content for a

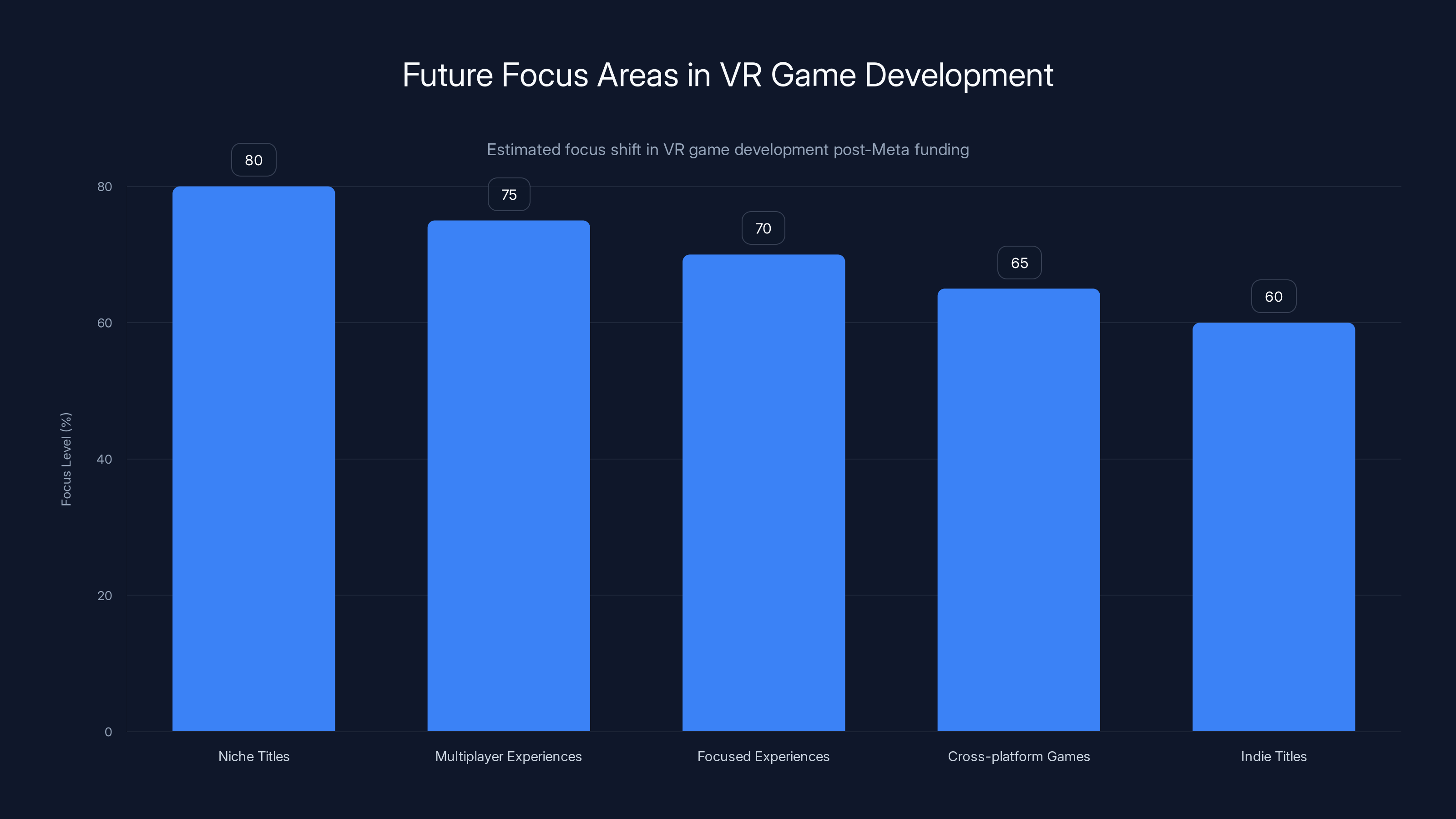

The Long-Term Implications for VR Development

Where VR Gaming Goes From Here

Without Meta's funding, VR game development becomes harder for ambitious projects. Studios will need to find alternative funding or prove they can be profitable on smaller budgets.

This probably means more focus on:

- Niche titles that serve specific communities (rhythm games, tactical shooters, exercise apps)

- Multiplayer experiences where the game serves as a platform for social interaction

- Smaller, more focused experiences rather than sprawling story-driven games

- Cross-platform games that make sense on both VR and flat screens

- Indie titles built by smaller teams with lower budgets

What probably happens less:

- Big-budget single-player campaigns requiring 200+ person teams and 5+ year development timelines

- Licensed IP experiences unless they're funding themselves through entertainment revenue

- Experimental VR gameplay that's too niche to sustain a team

The ecosystem adapts. It doesn't disappear. But it changes shape.

The Apple Wildcard

While Meta's pulling back, Apple's Vision Pro exists as a $3,500 proof that there's interest in spatial computing among wealthy consumers.

Apple's not publishing as many games as Meta. That's partly because Vision Pro's user base is tiny compared to Quest, and partly because Apple doesn't see VR/spatial computing as a gaming platform primarily. It's a computing device.

But Apple's presence matters. It signals to developers that spatial computing is real enough that serious companies are betting on it. If Vision Pro eventually comes down in price and finds a wider audience, you might see serious game development renewed—not for Meta's platform, but for Apple's.

That would be the irony: Meta invests billions, fails to crack the code, pulls back. Then Apple does something smaller, smarter, and it actually works.

The Reality Labs Question: What's It Actually For Now?

Meta still has Reality Labs, the division that handles VR and AR. But what's its mandate now?

The metaverse dream is effectively dead. Horizon Worlds, Meta's virtual world platform, has been quietly deprioritized. The company stopped talking about it as much. It exists, people use it, but it's not a strategic focus.

If Reality Labs isn't developing the metaverse and isn't investing heavily in VR games, what are they doing? Mostly wearables R&D and maintaining existing products.

This is a meaningful reduction in scope. Reality Labs went from trying to reinvent the internet to maintaining a product line and exploring emerging technologies. That's a fundamental shift in organizational purpose.

Internally, this probably means Reality Labs is smaller, has less autonomy, and needs to prove ROI faster. It's no longer the company's grand bet. It's a division.

Estimated data suggests Meta is prioritizing AR glasses and wearable technologies over VR gaming, reflecting a strategic shift in focus.

Lessons for the Broader Tech Industry

The Danger of Betting Too Big on One Vision

Meta's VR/metaverse push is a textbook case of concentration risk. The company bet so heavily on one vision of the future that when it didn't materialize on expected timelines, the entire strategy needed resetting.

A more diversified approach—investing in VR, AR, wearables, and other emerging tech simultaneously—might have been safer. You don't put all your resources into one bet, no matter how confident you are.

For other companies watching this play out: this is a cautionary tale. When your CEO becomes personally identified with a bet, it's harder to pivot when that bet isn't working.

The Underestimated Cost of Long Development Cycles

Game development takes forever. Great VR game development takes even longer because the medium is newer and you can't just port existing solutions.

Meta funded studios to build games over 3-5 year cycles. By the time those games shipped, the market landscape had changed. Meanwhile, the company was burning cash on R&D, infrastructure, and ongoing operations.

The math breaks down when adoption isn't growing as fast as predicted. If you assume 1 billion VR headsets and games sell for

The Importance of Platform Effects

Meta thought money could compensate for platform effects. They could just fund better content and pull people in.

But platform effects are real. iOS succeeded partly because Apple had tight integration between hardware, OS, and killer apps. Android succeeded partly because it was the default on smartphones. VR doesn't have those inherent platform effects. You need to build them.

That's harder than Meta apparently believed. You can't just throw money at it.

What Happens to Existing VR Games

One often-overlooked question: what happens to the games Meta funded that are still around?

Games like Echo VR, The Thrill of the Fight, and others continue to exist. They might get updates from skeleton crews, but they're not getting the same level of investment. Some will eventually be discontinued. Some will be maintained indefinitely.

Users of these games face uncertainty. You can't know which titles will survive and which will eventually be shut down.

This is a broader problem with digital products. When the company stops supporting something, it's gone. That's different from physical games where you own the cartridge forever. It's a reminder that digital ownership comes with conditions.

The Employee Impact and Industry Health

The human side of this story matters. When Meta closes studios, people lose jobs. Not everyone finds new work easily. Some leave the industry entirely.

But there's also a secondary effect: the people who stay become aware that their projects can be killed quickly. That affects morale and retention industry-wide. Developers become more cautious about long-term projects. They prioritize stability over ambition.

That could subtly harm VR game quality. The developers willing to take risks, commit to long-term projects, and push creative boundaries are the same ones who left VR after Meta's cuts. That leaves the industry with more conservative developers.

Meta's VR headset release frequency has decreased over the years, indicating a shift from rapid iteration to a more cautious approach. Estimated data.

The Meta Statement and What It Actually Means

Meta's official statement emphasized that they're "committed" to VR and gaming. They're "shifting investment" to third-party developers. It's the kind of language companies use when they're clearly retreating but want to minimize the perception of retreat.

Oculus Studios director Tamara Sciamanna's memo was more honest: "These changes do not mean we are moving away from video games." The phrasing "do not mean" suggests they realized people would interpret the closures as Meta leaving gaming entirely. So they're saying that's not true.

But the facts contradict the statement. You're closing studios. You're stopping app updates. You're pausing hardware partnerships. That sounds like moving away, even if technically you're not abandoning the entire category.

The gap between Meta's official statements and their actual actions is the real story here.

Competitive Implications: Sony, HTC, Valve

Sony's Play Station VR Strategy

Sony's been quieter about VR than Meta, but they're still supporting it. PlayStation VR2 exists, games are being developed for it, and Sony's treating VR as a valuable but niche part of their gaming portfolio.

Sony's advantage: they don't have to make VR work. They make most of their money from traditional consoles. VR is supplementary. So they can be patient. They don't need massive adoption next year.

Meta's problem was that they needed VR to work immediately. Reality Labs had to be a massive driver of the company's growth. That pressure led to overly aggressive investment and then overcorrection.

HTC and Valve's VR Ecosystems

HTC Vive and Valve's VR efforts have always been smaller, more focused, and less evangelical than Meta's. They're succeeding, quietly, without trying to convince the entire world to adopt VR.

Vive Cosmos targets enthusiasts. Steam VR targets PC gamers. Neither is trying to be the metaverse. They're building platforms for people who already want VR. That's a more sustainable model.

Meta's failure partly stems from trying to create demand for something people didn't inherently want yet. HTC and Valve just serve existing demand.

What Could Have Gone Differently

Speculative, but worth considering:

If Meta had diversified: instead of betting everything on the metaverse, they could have funded VR gaming alongside other projects. Less concentrated risk.

If they'd been patient: VR adoption was always going to take decades. Meta acted like it would happen in 5 years. Different assumptions would lead to different strategies.

If they'd focused on content: instead of trying to build the entire VR ecosystem, focus on becoming the best platform for games. Let others build social experiences.

If Zuckerberg had different priorities: much of Meta's VR commitment came from personal conviction at the top. Different leadership might have made different bets.

None of this happened. But it illustrates how many decision points could have led to a different outcome.

Estimated data suggests a shift towards niche, multiplayer, and cross-platform VR games as developers adapt to reduced funding from Meta.

The Metaverse's Reputation Damage

The biggest casualty of Meta's VR pullback might be the word "metaverse" itself.

For a few years, the metaverse was this exciting, future-forward concept. Now it's become a punchline. "Remember when Meta was building the metaverse?" people ask with a slight laugh. The term itself has become associated with failure.

That's not entirely fair. The concept of virtual worlds might still matter. But the specific vision Meta sold—everyone living and working in persistent virtual spaces—is effectively dismissed now.

It'll take new companies, new technologies, and new leadership with credibility to rebuild interest in spatial computing and virtual worlds. Meta's damaged that brand significantly.

Future VR Outlook: Realistic Assessment

Where We Actually Stand

VR is a real category with real users. Millions of people own headsets. Thousands of developers build VR content. It's a functioning market.

But it's also a mature market that's stabilized at a particular size. It's not going to be the next platform revolution. It's a niche that serves particular use cases well: gaming, training, entertainment, medical applications.

That's fine. Not everything needs to be revolutionary. Some products can just be good, useful things that serve their market well.

The Actual Timeline for Mainstream Adoption

When might VR become truly mainstream? Probably 10-20 years away, once hardware gets cheaper, better, lighter, and wireless. Once the content library is massive. Once enough content creators use VR that it becomes part of culture.

Meta was betting on that happening in 5 years. Reality is more patient.

What Actually Drives Next-Gen VR

The things that will actually drive VR forward:

- Better hardware: lighter headsets, better optics, longer battery life, wireless everything

- Standalone experiences: games and apps that are compelling on their own, not relying on metaverse or social features

- Killer app: something genuinely novel that only VR can do, something that makes people buy headsets

- Price: 500-3000

- Comfort: all-day wearability without fatigue

Meta's approach (throwing money at developers, building social platforms, pushing hardware) doesn't actually move any of these needles. Some would require different companies, different technologies, different timelines.

Expert Perspectives on What's Changed

Industry observers have had interesting reactions to Meta's pullback. Some see it as inevitable. Others see it as premature. Most agree on one thing: this is a turning point.

The consensus seems to be that VR's not going away, but the timeline for mainstream adoption got longer. And the company that was most confident about that timeline just admitted uncertainty.

That changes expectations across the entire industry.

The Broader Metaverse Concept Beyond Meta

Here's something worth noting: the metaverse concept exists separate from Meta's interpretation of it.

Roblox, Fortnite, and other games are kind of metaverse-like. Decentralized platforms are exploring virtual worlds. Gaming continues to evolve toward more immersive, persistent experiences.

Meta's version—Horizon Worlds, persistent avatars, virtual workplaces—is failing. But the broader concept of shared virtual spaces and virtual identities will probably continue evolving, just slower and differently than Meta imagined.

So the metaverse isn't dead. Meta's metaverse is dead. That's different.

Strategic Lessons for Building Emerging Tech Platforms

Don't Confuse Technology Readiness with Market Readiness

VR hardware was ready for gaming and entertainment years ago. The market wasn't ready to embrace it as the future of computing. Meta confused these things.

Having working technology is necessary, not sufficient. You also need the market to want it. Meta had the tech. They didn't have the want.

Third-Party Developers Can't Be Forced

Meta tried to fund studios hoping the games would pull in users and inspire other developers. That doesn't work. Developers follow users, not the other way around.

You need organic developer interest first. Throwing money at the problem when developers are skeptical just means your money burns and the developers still don't believe.

Concentration Risk in Corporate Strategy

Meta's entire strategic identity became wrapped up in the metaverse bet. When it didn't work, the company needed to reset. That's expensive and disruptive.

Healthy companies maintain multiple strategic bets. Some succeed, some fail. When one fails, you adjust. Meta acted like VR/metaverse was too big to fail, so they didn't adjust until they were forced to.

What Happens to Meta's VR Strategy Going Forward

The Most Likely Path

Meta probably continues supporting VR as a product line. They maintain Quest. They fund some development. They keep the ecosystem alive.

But it's no longer a strategic priority. It gets resources and attention proportional to its revenue, not proportional to its potential.

This is probably fine for Meta. VR is profitable enough. They don't need to grow it explosively. They just need to maintain it.

Possible Surprises

Some scenarios that could change this:

- Apple succeeds with Vision Pro and forces Meta to respond: if Apple creates genuine mass-market demand for spatial computing, Meta might re-engage with higher investment

- Killer app emerges: some application of VR nobody predicted becomes suddenly essential, driving adoption

- Hardware breakthrough: a fundamental advancement in VR hardware (holographic, neural interface, etc.) changes the equation

- New leadership: if Zuckerberg steps back from direct involvement in metaverse projects, priorities might shift

None of these seem likely in the next 2-3 years, but they're possible.

The Human Cost Rarely Discussed

Thousands of people lost their jobs when Meta closed these studios. Some had families, mortgages, student loans. Some had turned down other job offers to work on VR games.

The industry often focuses on strategic implications and market signals, but the human cost matters. These were people who believed in VR's potential and committed years to building it.

That's worth acknowledging, even if it doesn't change the strategic analysis.

FAQ

Why did Meta close Armature, Sanzaru, and Twisted Pixel studios?

Meta closed these three VR studios as part of a broader strategic shift away from the metaverse and toward wearables. The company decided that funding expensive, long-term game development wasn't an efficient way to drive VR adoption. Instead, Meta is reallocating resources to AR glasses and other wearable technologies, which the company views as higher-priority for its future.

What was Supernatural and why did it stop getting new content?

Supernaturally was Meta's VR fitness app that provided guided workout experiences in virtual reality. It had active users and a subscription model, making it one of Meta's more successful consumer VR applications. Even though the app was profitable and well-used, Meta stopped funding new content updates as part of the broader deprioritization of VR gaming, though the existing app continues to be maintained at a basic level.

What does this mean for VR gaming in 2025?

The studio closures signal that the era of massive corporate funding for VR games is ending. Developers will need to focus on more niche titles with smaller budgets, multiplayer experiences that sustain themselves through communities, and games that work across multiple platforms. While VR gaming will continue, the landscape will shift toward indie developers and smaller-scope projects rather than big-budget, story-driven games.

Is Meta abandoning VR entirely?

No, Meta is not abandoning VR entirely. The company continues to support Quest hardware and maintains some internal development capabilities. However, Meta is clearly deprioritizing VR in favor of investing in wearables like AR glasses. VR has shifted from being Meta's primary strategic bet to being a maintained product line that generates revenue but isn't a focus for new investment or growth.

How does this affect the broader VR ecosystem?

Meta's pullback creates uncertainty for independent developers who were relying on Meta's funding and platform support. Other companies like Sony, HTC, and Valve are continuing their VR efforts, but at smaller scales. The overall effect is likely a consolidation of the VR market around smaller, more sustainable projects rather than ambitious, long-cycle game development. The ecosystem doesn't disappear, but it becomes niche-focused rather than consumer-mass-market-oriented.

What was Meta's metaverse vision and why didn't it work?

Meta envisioned the metaverse as a persistent virtual world where people would spend significant portions of their daily lives working, socializing, and entertaining themselves in immersive virtual spaces. This didn't happen because the technology wasn't sufficiently compelling, the social dynamics were harder to build than expected, adoption rates were slower than predicted, and alternative technologies (like traditional social media and AR glasses) remained more practical for daily use. The gap between the vision and market reality proved too large.

Will other companies succeed where Meta failed?

Possibly. Apple's approach with Vision Pro is different—focused on computing and augmented reality rather than virtual worlds. Gaming platforms like Roblox and Fortnite continue to evolve toward more immersive experiences. But most analysts believe that true mainstream adoption of VR and virtual worlds is 10-20 years away, not the 5-year timeline Meta was betting on. Success will likely require hardware breakthroughs, different business models, and more organic market demand.

What about the people who made these games?

Employees from Armature, Sanzaru, and Twisted Pixel were laid off or reassigned. Some will find work at other VR studios or game companies. Others will leave the gaming industry entirely. The closures represent a significant loss of experienced VR development talent and institutional knowledge about how to build games for the platform.

Is VR dead?

No, VR isn't dead. It's a functioning market with millions of active users, continuous hardware development, and ongoing content creation. What's dead is the specific vision of VR becoming the primary platform for computing and social interaction within the next few years. VR will likely remain a niche technology for gaming, training, entertainment, and specialized applications for the foreseeable future.

What should developers do if they're considering building VR games?

Developers should be realistic about market size and adoption. Focus on niches where VR provides genuine value rather than chasing mainstream adoption. Consider cross-platform development that works on both VR and traditional screens. Be cautious about pursuing massive, multi-year projects without clear revenue models. Prioritize sustainability over scale, and build for communities that actively want VR experiences rather than betting on mass-market adoption.

How will this affect VR hardware development?

Meta's reduced investment in VR content and partnerships might slow hardware development slightly, as there's less pressure to create cutting-edge platforms. However, companies like Apple, Sony, HTC, and Valve continue their own hardware initiatives. The overall trajectory of VR hardware will be shaped more by technological progress in displays, processing power, and battery life than by any single company's strategic decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Meta closed three major VR studios (Armature, Sanzaru, Twisted Pixel) as part of a strategic shift from metaverse investment to wearable technology

- The closures signal that VR market adoption has plateaued at 200-300 million headsets globally, far below Meta's initial $1 trillion+ projections

- Even profitable VR products like Supernatural were deprioritized, indicating Meta no longer believes game development is the path to mainstream adoption

- The VR industry will likely shift toward niche applications and independent developers rather than ambitious, long-cycle AAA game development

- Alternative approaches from companies like Apple (Vision Pro) and traditional platforms like PlayStation VR may prove more sustainable long-term than Meta's all-in metaverse bet

![Meta's VR Studio Closures: The Metaverse Reality Check [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-vr-studio-closures-the-metaverse-reality-check-2025/image-1-1768338529109.jpg)