How Microsoft is Tackling the AI Emissions Crisis Through Carbon Removal in India

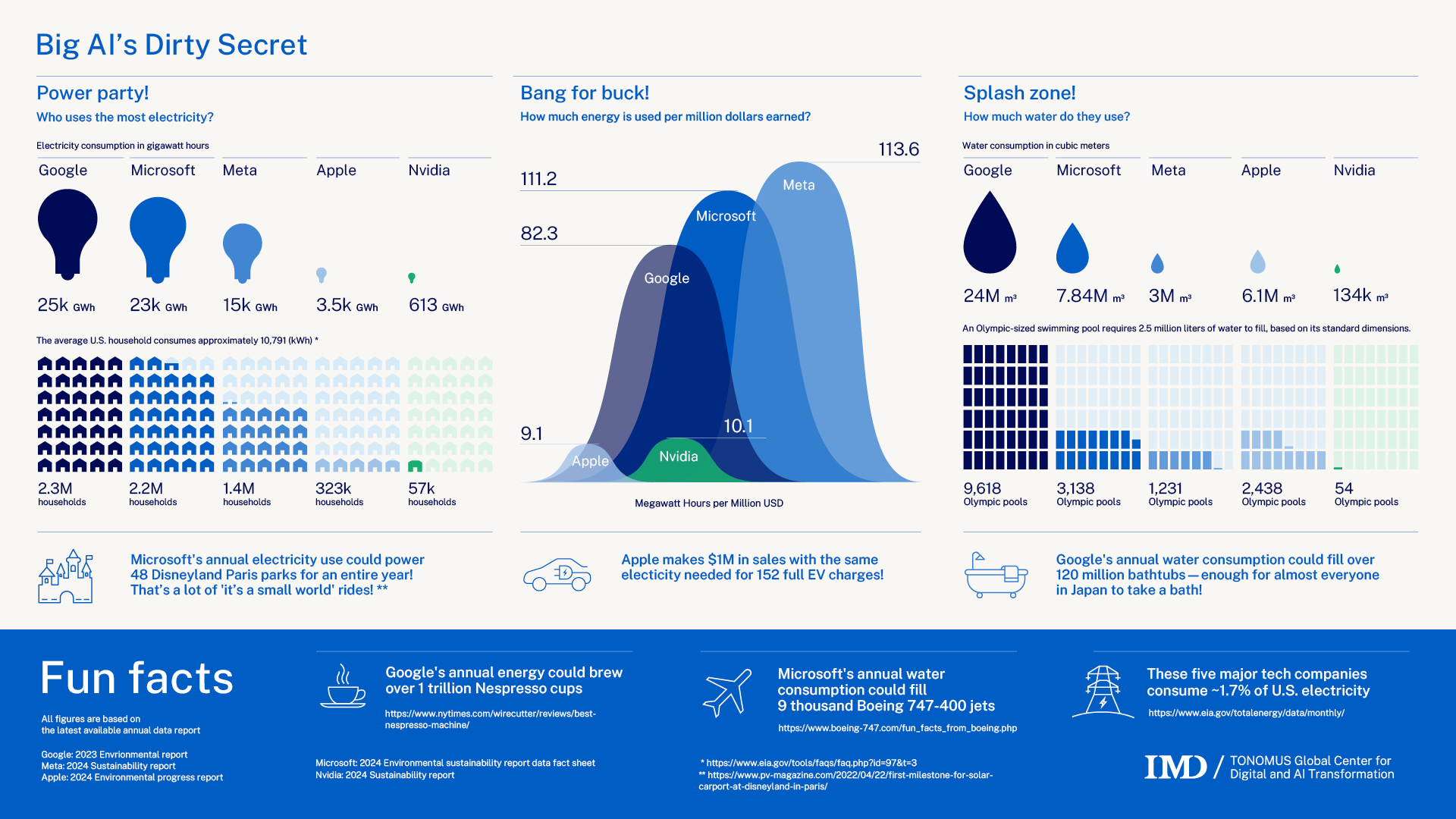

Here's the thing about artificial intelligence: it's incredibly powerful, but it drinks electricity like nothing else. Every Chat GPT query, every recommendation algorithm, every neural network running on Microsoft's servers consumes energy. And energy, at least for now, comes with a carbon cost attached.

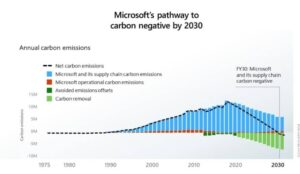

Microsoft knows this. The company's greenhouse gas emissions jumped 23.4% in fiscal year 2024 compared to its 2020 baseline, driven largely by the explosive growth of cloud computing and AI services. That's a problem when you've publicly committed to becoming carbon-negative by 2030.

So the company is getting creative. Instead of just trying to power everything with renewables (which takes time) or reducing energy consumption (which is hard when your business depends on scaling AI), Microsoft is investing heavily in carbon dioxide removal—actual technology that sucks CO2 out of the atmosphere and locks it away permanently. And in January 2026, the company took a major step by signing a historic deal with an Indian startup called Varaha to buy over 100,000 metric tons of carbon removal credits over three years, as reported by TechCrunch.

This isn't just another corporate sustainability announcement. It's a glimpse into how big tech is approaching one of the most pressing problems of the AI era: the carbon footprint of artificial intelligence itself. And it reveals something interesting about where the future of carbon removal might be heading.

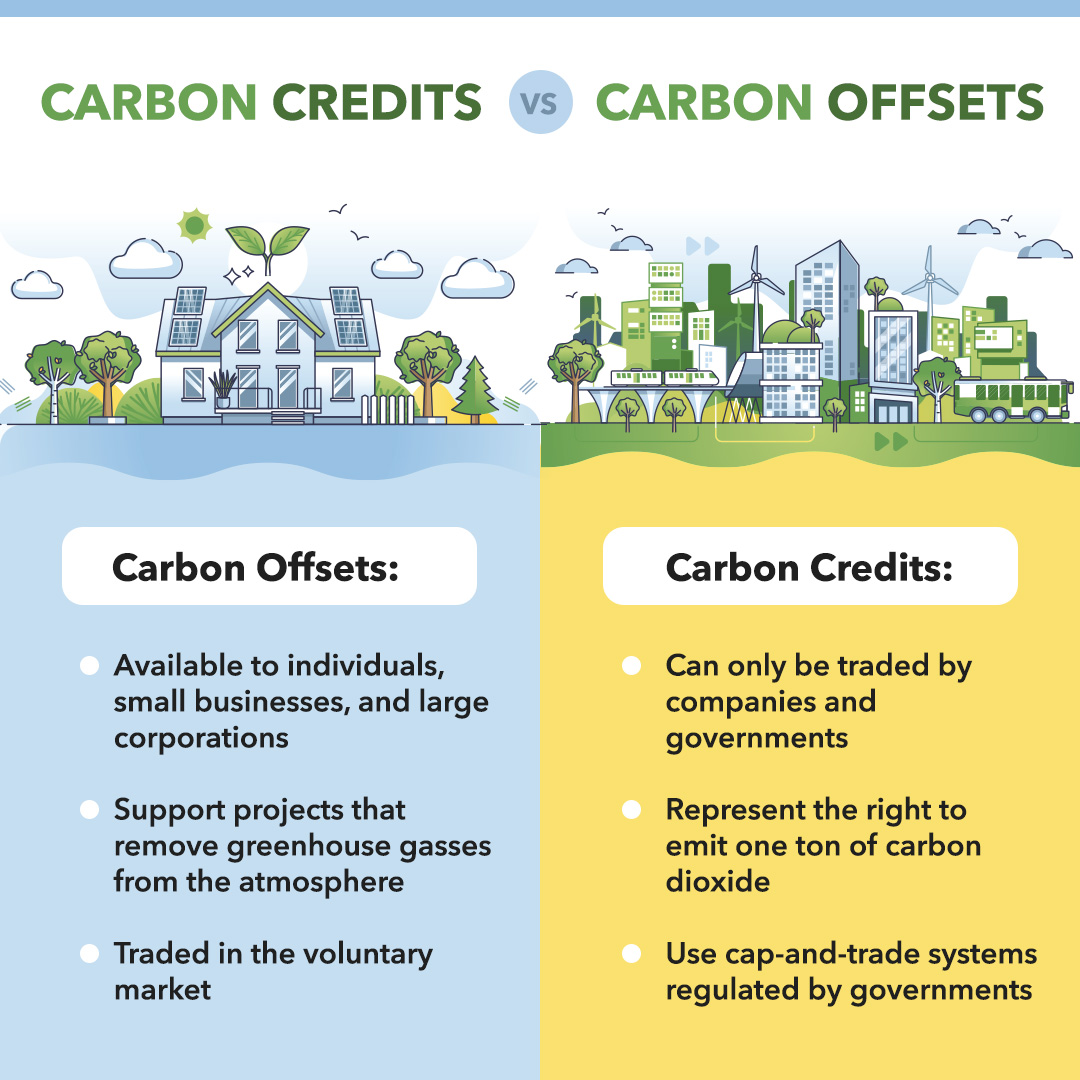

Understanding Carbon Dioxide Removal vs. Carbon Offsets

Let's start with the basics, because this distinction matters more than most people realize.

When companies talk about going "carbon-neutral" or "carbon-negative," they're often throwing around different concepts that sound similar but work very differently. Carbon offsets are one thing. Carbon removal is another entirely.

Carbon offsets are essentially investments in projects that prevent future emissions. Plant a forest, and it absorbs CO2 as it grows. That's an offset. Build a solar farm instead of a coal plant, and you've offset emissions that would have happened. These are valuable, but they don't actually reduce the CO2 already in the atmosphere.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is the opposite approach. Instead of preventing new emissions, CDR technologies physically extract CO2 from the air—either directly through direct air capture machines, or indirectly through natural processes enhanced by human intervention. Once you remove it, you need to store it permanently so it doesn't just get released again.

Microsoft's deal with Varaha is specifically for durable carbon removal. The company isn't just preventing future emissions. It's paying for actual, measurable CO2 removal from the atmosphere.

Why does this matter? Because offsets alone won't solve the climate problem if we're adding more emissions every year. At some point, you need to actually remove carbon. And that's expensive, technically difficult, and relatively new at scale. But as AI energy consumption grows, companies like Microsoft are betting big that CDR will become essential.

The Rise of AI Energy Consumption and Corporate Carbon Commitments

The relationship between artificial intelligence and energy consumption is becoming one of the defining stories of the tech industry. Every major AI model requires massive computational resources. Training a large language model like GPT-4 consumes as much electricity as thousands of homes use in a year. Running these models at scale—across millions of queries daily—requires entire data center clusters dedicated to nothing but AI inference.

Microsoft has embedded AI throughout its entire business. Copilot features are baked into Office 365, Teams, Windows, and Azure. The company's partnership with OpenAI means it's running some of the most demanding AI models on the planet, at scale, every single day.

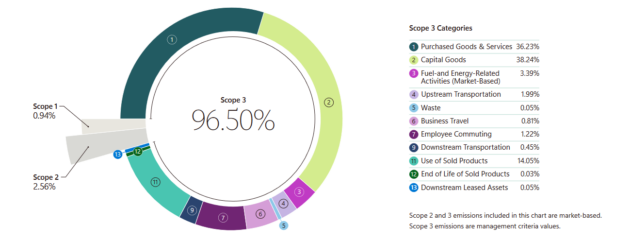

Here's what the numbers look like: Microsoft's total greenhouse gas emissions in FY2024 reached 15.5 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent. The company's value chain emissions (Scope 3)—meaning emissions from suppliers, data center operations, and customer use of products—now represent the largest portion of the company's carbon footprint.

But Microsoft has made a bold public commitment: carbon-negative by 2030. That means not just eliminating emissions, but removing more CO2 than the company produces. It's an aggressive target, especially for a company whose emissions are trending upward.

To hit that goal, Microsoft is diversifying its approach. The company continues investing in renewable energy for its data centers, implementing efficiency improvements, and working with suppliers to reduce scope 3 emissions. But it's also recognizing reality: even with all that effort, the company's emissions will probably still exceed zero in 2030. So it needs carbon removal.

The company contracted for approximately 22 million metric tons of carbon removals in FY2024 as part of its carbon-negative strategy. That's a massive commitment—potentially costing hundreds of millions of dollars depending on the price per ton. And it shows just how serious the company is about hitting its targets.

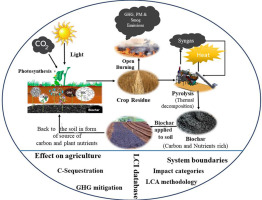

Biochar: Why Agricultural Waste is Becoming a Carbon Removal Asset

Here's where Varaha comes in. The Indian startup doesn't use direct air capture machines or other high-tech approaches. Instead, it transforms agricultural waste into biochar—a charcoal-like material that can be added to soil, where it stores carbon for decades or even centuries.

The process is surprisingly elegant. Farmers in India, particularly cotton farmers, typically burn their crop residue after harvest. It's traditional, it clears the field quickly, but it produces massive amounts of air pollution. Seasonal burning in agricultural regions like Maharashtra creates hazardous air quality that affects millions of people.

Variaha's solution: collect that agricultural waste—cotton stalks, husks, and other biomass—and process it through industrial gasification reactors. These reactors heat the biomass to high temperatures in a low-oxygen environment, breaking it down into biochar (a solid) and syngas (a gas that can be used for energy).

The biochar is then applied to soil. This serves multiple purposes simultaneously. First, the carbon in the biochar is locked in a stable form that resists decomposition. Studies suggest biochar can persist in soil for hundreds of years, storing carbon permanently. Second, biochar improves soil health—it increases water retention, reduces the need for chemical fertilizers, and boosts crop productivity. Third, by using agricultural waste for biochar instead of burning it, the project reduces air pollution that devastates air quality in rural India during burning season.

From a carbon removal perspective, the math is straightforward. The biomass contains carbon that was recently captured from the atmosphere (through photosynthesis while the plants grew). When you convert that biomass to biochar and bury it in soil, you're essentially putting that carbon into long-term storage. The carbon removal credits represent the tons of CO2 that have been removed from the active carbon cycle and stored in a stable form.

It's not flashy technology like direct air capture machines sucking CO2 directly out of the atmosphere. But it works, it's scalable to agricultural economies, and it provides immediate co-benefits (healthier soil, reduced air pollution) alongside the carbon removal.

Varaha's Track Record and Rapid Scaling in India

Variaha wasn't created yesterday. The startup has spent years building out its operations across India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, working with smallholder farmers to implement carbon-removal agriculture practices.

The company currently has 20 projects across three countries, with 14 in advanced stages and six in early development. It works with approximately 150,000 farmers across multiple project types: regenerative agriculture, biochar production, agroforestry, and enhanced rock weathering. Across all these projects, Varaha estimates it will sequester about 1 billion metric tons of CO2 over project lifetimes ranging from 15 to 40 years.

That's the long-term vision. But the growth trajectory over the past year shows just how rapidly the company is scaling its actual delivery.

In 2025, Varaha processed approximately 240,000 metric tons of biomass through its operations. That biomass produced roughly 55,000 to 56,000 metric tons of biochar and generated about 115,000 carbon removal credits. That's a massive jump from 2024, when the company generated around 15,000 to 18,000 credits for the entire year.

Meaning: year-over-year, Varaha increased its carbon credit generation by more than 500%. In a single year.

The company projects even faster growth in 2026. With new contracts coming online (including Microsoft's 100,000-ton deal), Varaha aims to double its 2025 biomass throughput to approximately 500,000 metric tons. If the company hits that target, it will sequester close to 250,000 metric tons of carbon in 2026 alone—more than 2.5 times what it sequestered in 2025.

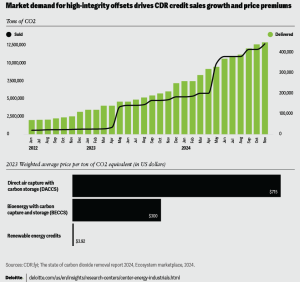

What explains this rapid scaling? Part of it is simple: demand. Corporate commitments to carbon removal are accelerating, and prices for verified carbon removal credits are climbing. For companies trying to hit carbon-negative targets, durable removal credits are worth paying for. Varaha has positioned itself as a supplier that can deliver verified, auditable carbon removal at scale.

The Microsoft-Varaha Agreement: Scale and Duration

Let's break down what the Microsoft deal actually represents.

Microsoft will purchase more than 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide removal credits over three years, through 2029. Those credits will come from Varaha's biochar project, specifically from operations in India's cotton-growing belt. The agreement includes significant infrastructure investment: Varaha will develop 18 industrial gasification reactors that will operate for 15 years. Over the entire 15-year operational period, the project is projected to remove more than 2 million metric tons of CO2 from the atmosphere, as detailed in TechCrunch.

To put that in perspective: Microsoft's 100,000-ton commitment over three years represents an average of about 33,000 metric tons per year. Given that the company contracted for 22 million metric tons of removals in FY2024, the Varaha deal represents less than 0.5% of Microsoft's total CDR commitments. So it's not a massive portion of Microsoft's carbon removal portfolio. But it's significant for other reasons.

First, it's geographically significant. This is Microsoft's first major carbon removal offtake in Asia. The company has previously signed large carbon removal agreements elsewhere—like the Louisiana project with Atmos Clear to remove 6.75 million metric tons over 15 years. But Asia represents a massive opportunity for carbon removal because of agricultural scale, biomass availability, and the sheer volume of smallholder farmers.

Second, the project demonstrates commitment to what's called "durable" carbon removal. The credit verification process is stringent. You can't just claim that you removed carbon—you need independent verification, measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems that prove it. For agricultural projects involving tens of thousands of smallholder farmers across rural India, that's genuinely complicated logistics.

Variaha had to build custom digital systems for monitoring, tracking, and verification that work with smallholder farmers who may not have reliable internet connectivity or sophisticated equipment. The company had to develop procedures for collecting, processing, and tracking biomass from 40,000 to 45,000 different farms. This level of operational complexity is why not every startup can deliver carbon removal at scale.

The Challenge of Monitoring and Verification at Agricultural Scale

Here's where the real difficulty of carbon removal becomes apparent: it's not just about building reactors and turning waste into biochar. It's about proving that you actually did it, that the carbon actually stayed sequestered, and that no shenanigans happened along the way.

In the United States or Europe, many biochar projects operate at centralized sites. A single biomass source gets processed at one facility. Tracking is relatively straightforward. But Varaha's project involves thousands of farms spread across India's cotton-growing regions. Biomass comes from many sources, farmers have varying practices, and the logistics of collection and tracking become exponentially more complex.

Microsoft's carbon removal requirements forced Varaha to implement rigorous digital monitoring systems. The company had to develop ways to track biomass from field collection, through transportation, through processing, to final biochar application in fields. It needed to document farmer participation, measure biochar quantity and quality, and verify that the carbon actually stayed in the soil.

This is expensive. Building bespoke verification systems across thousands of farms requires serious technical capability and infrastructure investment. It's why established players like Varaha have a competitive advantage over new entrants. The company has already sunk the capital into building these systems, training staff, and establishing trust with auditors and credit verification organizations.

It's also why carbon removal credits cost more than traditional carbon offsets. A ton of durable, verified carbon removal might cost

Co-Benefits: Soil Health, Air Quality, and Farmer Income

One of the smartest things about the Varaha project is that it doesn't depend entirely on carbon credit revenue. Yes, the carbon credits are valuable. But the project generates additional value through multiple channels.

First: soil health improvement. Biochar application to agricultural soil has been studied extensively. The material increases water-holding capacity, which matters enormously in regions where water scarcity affects yields. It improves soil structure and microbial activity. Over time, farmers who use biochar see improved crop productivity and reduced fertilizer requirements. Some studies show yield improvements of 10% to 30%, depending on soil conditions and climate.

For smallholder farmers in India, that's real economic value. If a farmer can reduce fertilizer costs by 20% and increase yields by 15%, the economic benefit might exceed the income they receive from carbon credit participation. This is crucial because it means the project has resilience. Even if carbon credit prices fall, farmers benefit from improved soil productivity.

Second: air quality improvement. The burning of agricultural residue in India creates massive air pollution events, particularly in northern regions like Punjab and Haryana. The haze from these fires affects millions of people, increases respiratory diseases, and reduces visibility and traffic safety. By converting crop residue to biochar instead of burning it, the project eliminates this pollution source entirely for participating farms.

Quote from Phil Goodman, Microsoft's carbon dioxide removal program director: "This offtake agreement broadens the diversity of Microsoft's carbon removal portfolio with Varaha's biochar project design that is both scalable and durable."

Third: farmer income stability. Carbon credit revenue provides additional income to farming communities. While the revenue may not be enormous per farmer (perhaps

The combination of these benefits—improved soil productivity, reduced pollution exposure, additional income, and positive environmental impact—is why projects like this gain support from governments, NGOs, and corporate partners.

Comparing Biochar to Other Carbon Removal Approaches

Biochar is just one carbon removal approach in a growing toolkit. Understanding how it compares helps explain why Microsoft is diversifying its carbon removal portfolio.

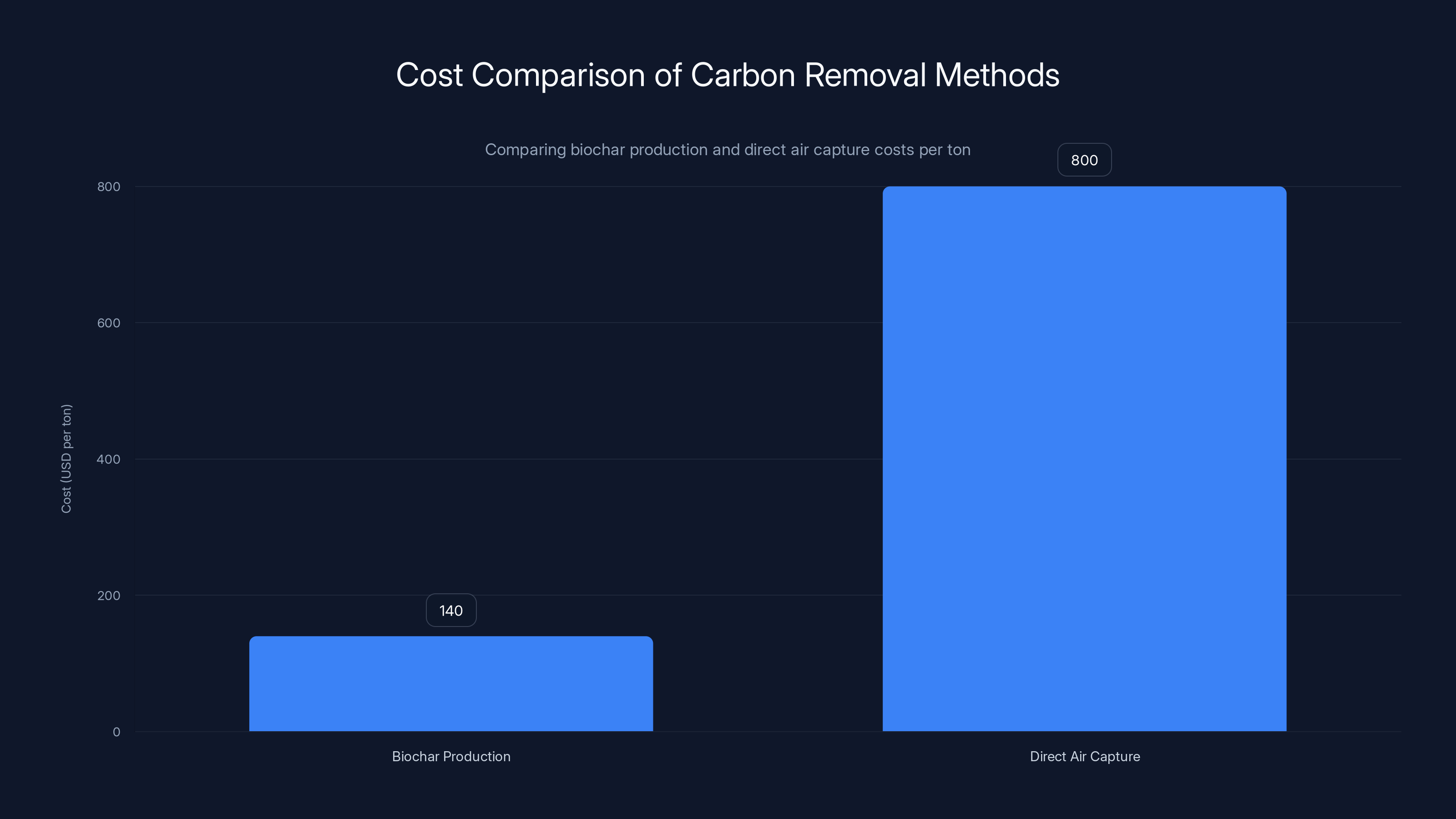

Direct Air Capture (DAC) represents the other major category. These technologies use machines to directly extract CO2 from the air using chemical sorbents or solvents. Companies like Carbon Engineering and Climeworks have deployed pilot DAC facilities. The advantage: you can deploy DAC anywhere, even in cities, and the process is proven at small scale. The disadvantage: it's extremely energy-intensive and expensive. Current DAC costs run

Enhanced Weathering involves spreading crushed silicate rocks on agricultural land. These rocks naturally absorb CO2 as they weather, and the process locks the carbon in rock minerals. It's scalable and inexpensive (roughly

Afforestation and Reforestation involve planting trees to absorb CO2. It's natural, proven, and creates co-benefits (wildlife habitat, timber value). But it requires large amounts of land, trees take decades to mature, and carbon credit permanence can be uncertain if forests burn or are harvested.

Ocean-based solutions like kelp farming or ocean alkalinity enhancement are emerging but largely unproven at scale and carry unknown environmental risks.

Biochar sits in an interesting middle ground. It's more expensive than enhanced weathering or afforestation but far cheaper than DAC. It's proven and scalable. It creates immediate co-benefits through soil improvement. And for agricultural regions with abundant biomass, it aligns economic incentives with environmental outcomes.

That's why Microsoft is investing across multiple approaches. The company is hedging its bets, supporting multiple technologies as they scale and improve. The portfolio approach acknowledges that no single technology will solve the problem.

The Broader Implications for Tech Industry Carbon Strategy

Microsoft's carbon removal push, exemplified by deals like the Varaha agreement, reflects a broader shift in how tech companies approach sustainability.

For years, corporate climate commitments focused on renewable energy and efficiency. Build more solar farms, make data centers more efficient, reduce energy waste. These approaches still matter, but they have limits. You can only improve efficiency so much. And transitioning entire energy grids to renewables takes decades.

But artificial intelligence has accelerated energy demands in ways that make incremental efficiency improvements insufficient. Training a large language model uses enormous amounts of electricity over months. Running inference at scale requires constant power. As AI becomes more ubiquitous—embedded in products across Microsoft's entire suite—energy consumption will keep climbing.

Companies could respond by slowing down AI deployment. But that's not happening. AI is too valuable, too integral to competitive advantage. Instead, companies are accelerating carbon removal investments as a way to offset growing emissions.

This has several implications. First, it means carbon removal becomes a permanent part of tech's operating costs. As emissions from AI grow, companies will need to spend more on carbon removal to maintain carbon-neutral or negative targets. This creates a steady market for carbon removal, which incentivizes investment in the technology and infrastructure.

Second, it means tech companies have strong financial incentives to fund carbon removal innovation. Microsoft's investments in startups like Varaha help prove business models, demonstrate scalability, and drive down costs. As more tech companies make similar commitments, carbon removal at scale becomes more viable economically.

Third, it suggests that pure decarbonization might be insufficient for heavy tech users. Instead, the model emerging is "emissions + carbon removal." You emit X tons of CO2, but you remove X tons through carbon removal projects. Net result: zero or negative emissions.

This is pragmatic and might be the realistic path forward given energy demands. But it also means the world needs massive scaling of carbon removal capacity. Currently, carbon removal at scale is limited. Varaha's target to remove 2 million tons over 15 years is meaningful but small compared to global emissions. The world needs to scale carbon removal to billions of tons annually to make a real dent in atmospheric CO2.

India as a Strategic Hub for Carbon Removal Projects

Why does Microsoft specifically target India for this major deal? The answer involves geography, economics, and agricultural structure.

India has several characteristics that make it ideal for carbon removal projects. First: massive agricultural sector. India has over 145 million farms, most of them smallholder operations producing crops like cotton, rice, wheat, and sugarcane. This creates enormous volumes of agricultural residue—biomass that's currently often burned or left to decompose.

Second: labor and operational costs are lower than in developed countries. Building and operating biochar facilities costs less in India than equivalent operations in the US or Europe. Similarly, working with thousands of farmers requires labor, and those labor costs are lower. This improves project economics and makes carbon removal more cost-effective.

Third: policy environment. The Indian government is actively encouraging agricultural innovation and carbon management practices. The country has expressed commitment to carbon reduction targets and supports projects that reduce open burning and improve soil health.

Fourth: environmental urgency. Air pollution from agricultural burning is a massive public health problem in India, affecting hundreds of millions of people. Projects that reduce this pollution have immediate social benefits alongside carbon removal benefits.

Fifth: biochar specifically has strong potential in Indian soils. Many Indian agricultural soils are degraded from intensive farming. Biochar can help restore soil health while sequestering carbon. The co-benefits are real and valuable.

All these factors explain why India has become a major focus for carbon removal companies and why Microsoft's investment in Varaha specifically targets India rather than developed markets.

The Question of Carbon Credit Verification and Permanence

Here's a thorny issue that doesn't get enough attention: how do you verify that carbon removed actually stayed removed?

For biochar, the verification question has several layers. First, you need to verify that the biomass actually became biochar (not that it was burned or left to decompose). This requires monitoring at processing facilities and documentation of quantities.

Second, you need to verify that the biochar actually got applied to soil in the quantities claimed. Varaha's digital tracking systems attempt to do this, but it requires cooperation from thousands of farmers and tracking across distributed geographical areas.

Third—and this is the contentious part—you need assurance that the biochar stays in the soil and doesn't just get burned or removed in a few years. Studies suggest biochar persists for centuries, but that's based on research, not direct observation over centuries. The project duration is 15 years, which provides some confidence in persistence, but not certainty.

Fourth, you need to account for indirect emissions. Growing and harvesting the crops, transporting biomass, operating the reactors—all of this uses energy and produces emissions. The net carbon removal is biomass carbon sequestered minus these operational emissions. Proper carbon accounting requires quantifying all of these.

Carbon credit verification organizations (like Verra or Gold Standard) have developed methodologies to address these questions, but they involve assumptions and estimates. Different projects use different methodologies, leading to different credit quantities for similar removal activities.

This creates both opportunity and risk. Opportunity: as methodologies improve and verification becomes more rigorous, carbon removal credits become more reliable and valuable. Risk: if verification standards are loose, you might purchase carbon removal credits that don't represent real, permanent removal.

Microsoft's large commitment to Varaha suggests the company is confident in the verification approach. The company has sophisticated teams evaluating carbon removal projects and wouldn't make nine-figure commitments to projects with weak verification. But it's worth recognizing that some uncertainty remains.

The Economics: What Does Carbon Removal Actually Cost?

Let's talk money. What does 100,000 metric tons of carbon removal actually cost?

Variha and Microsoft haven't disclosed the contract price. But you can estimate based on market rates. Durable carbon removal credits (biochar, direct air capture, enhanced weathering) typically range from

If you assume

These are significant commitments, but not enormous for a company of Microsoft's scale. The company's annual revenue exceeds

What's more important is the trajectory. As Microsoft scales its carbon removal commitments—the company aims for 22 million metric tons in FY2024 and presumably higher in subsequent years—the company is committing to spending potentially hundreds of millions annually on carbon removal.

For context, if average costs are

This creates economic incentives for carbon removal innovation. When large corporations commit to spending billions on carbon removal, startups and established companies have clear business opportunities. The market expands. Competition drives down costs and improves technology. That's the theory, anyway.

For Varaha specifically, the Microsoft contract is tremendously valuable. It provides a large, multi-year revenue stream and validates the company's model at scale. It also provides capital (or signals to investors that capital should flow) for infrastructure investment—those 18 reactors won't build themselves.

Challenges in Scaling Agricultural Carbon Removal Projects

Despite the promise of agricultural carbon removal, scaling to meaningful levels faces real obstacles.

Smallholder farmer coordination is genuinely difficult. Varaha works with 40,000 to 45,000 farmers for the Microsoft project alone. Each farmer has independent land, independent decisions, independent financial pressures. Getting consistent participation, high-quality biochar application, and accurate documentation across thousands of farms requires sophisticated systems, training, and ongoing support.

Logistical complexity of collecting biomass from distributed sources and processing it centrally is operationally challenging. Cold supply chains in developed countries are hard enough; managing biomass supply chains across rural India is orders of magnitude more complex.

Weather and climate variability affects both biomass availability and biochar application timing. Droughts reduce biomass production. Monsoons make field access and application difficult. Projects need to account for variable years and still meet carbon removal commitments.

Economic dependency on smallholders creates vulnerability. If carbon credit prices collapse, farmer participation might drop. If farming becomes less profitable for other reasons, farmers might abandon participation. The project's viability depends on sustained farmer engagement.

Political and regulatory risk in countries like India is real. Policy changes, restrictions on agricultural practices, or shifts in government priorities could disrupt project operations.

Credit verification and audit costs are significant. Maintaining rigorous monitoring, reporting, and verification systems across thousands of farms is expensive. These costs reduce the net carbon removal per dollar spent.

These challenges explain why carbon removal projects require significant upfront capital investment and operational expertise. They also explain why established companies like Varaha have competitive advantages—they've already solved many of these problems.

Microsoft's Broader Carbon Removal Portfolio Strategy

The Varaha deal is one piece of a much larger puzzle. Microsoft has signed multiple major carbon removal agreements in recent years, and the company's strategy reveals how serious tech companies are about CDR.

Beyond the Varaha biochar project, Microsoft has backed Atmos Clear's Louisiana project to remove 6.75 million metric tons over 15 years. That's a direct air capture project—using machines to extract CO2 directly from air and store it underground. It's expensive (likely over $600 per ton), but it provides high certainty and permanence.

Microsoft has also invested in enhanced weathering projects and other approaches. The company is deliberately building a diversified portfolio that includes multiple carbon removal technologies, multiple geographies, and multiple price points.

This portfolio approach makes strategic sense. No single technology will solve the problem. Different technologies have different trade-offs in cost, scalability, permanence, and co-benefits. By investing across multiple approaches, Microsoft hedges technological risk and supports the overall development of the carbon removal sector.

It also signals to the market that Microsoft is a credible buyer of carbon removal. Startups and established companies considering carbon removal investments know that Microsoft—with deep pockets, technical expertise, and brand reputation—will purchase verified credits. That confidence attracts investment to the sector.

The 2030 Carbon Negative Target: Is It Achievable?

Microsoft's commitment to become carbon-negative by 2030 is ambitious. With current emissions trending upward due to AI growth, the company faces a challenging target.

Let's do some math. Microsoft's FY2024 emissions were 15.5 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent. If emissions continue growing at 5% to 10% annually due to AI expansion, by 2030 the company might be emitting 20 to 23 million metric tons annually.

To be carbon-negative, Microsoft needs to remove more than it emits. So the company might need to remove 25 to 30 million metric tons annually by 2030 to achieve negative emissions.

The company says it has contracted for 22 million metric tons of removal in FY2024. If the company can maintain or increase this rate over the next five years, hitting 25 to 30 million metric tons by 2030 is theoretically possible. But it requires flawless execution, continued access to capital, and that carbon removal projects actually deliver as promised.

There are scenarios where Microsoft falls short. Carbon removal credits might become more expensive as demand increases. Project delays or verification failures might reduce credit supply. New competing buyers might drive up prices. Climate or political changes might disrupt projects.

But there are also scenarios where Microsoft succeeds. Carbon removal technology might improve faster than expected, reducing costs. New projects might exceed delivery expectations. Partnerships with companies like Varaha might prove more productive than anticipated.

The most likely outcome: Microsoft achieves something close to carbon-negative by 2030, though perhaps not perfectly. The company might end up 95% carbon-negative or 90% carbon-negative rather than 100%. But even reaching that level would be extraordinary for a company of Microsoft's scale and would represent a genuine decoupling of business growth from carbon emissions growth.

What This Means for the Future of Corporate Climate Action

The Varaha deal is a signal. It shows that major tech companies are moving beyond pledges and into actual capital deployment for carbon removal. This has several implications.

First, it validates that carbon removal markets are real and growing. Startups have had a hard time fundraising for carbon removal projects because the business model was uncertain. A major Microsoft deal removes that uncertainty. Other startups in the space will find it easier to raise capital, attract talent, and secure offtake agreements.

Second, it raises the bar for corporate climate commitments. If Microsoft is spending hundreds of millions on carbon removal to hit carbon-negative, other large tech companies will face pressure to do the same. This creates a kind of competitive dynamic in climate action—companies don't want to be seen as less committed to sustainability than competitors.

Third, it suggests that complete emissions elimination might not be the path forward for energy-intensive industries. Instead, the model emerging is: reduce emissions where practical (efficiency, renewable energy), then remove remaining emissions (carbon removal). This "emissions + removal" approach is more realistic than insisting on absolute zero emissions for power-hungry industries like AI.

Fourth, it highlights the importance of developing carbon removal capacity in emerging economies. The Varaha deal is in India, a developing nation with different cost structures and agricultural systems than developed countries. As carbon removal scales, it will depend heavily on projects in developing countries where agricultural biomass is abundant and costs are lower.

Fifth, it underscores the economic transformation happening in agriculture. Farmers are increasingly viewed not just as food producers but as potential stewards of ecosystem services and carbon management. Payments for carbon removal, soil health, and pollination services could fundamentally change farm economics over the next decade.

Conclusion: The Intersection of AI, Emissions, and Carbon Removal

Microsoft's 100,000-ton carbon removal deal with Varaha isn't just a corporate sustainability announcement. It's a window into how the tech industry is reckoning with the environmental consequences of artificial intelligence and cloud computing at massive scale.

The company is being honest about a basic problem: its emissions are growing because its business is growing. AI is energy-intensive. Data centers consume enormous amounts of electricity. You can't solve that problem with efficiency alone, at least not quickly enough to hit 2030 carbon-negative targets.

So Microsoft is turning to carbon removal. The company is investing in multiple technologies, multiple geographies, and partnerships with established players like Varaha that have proven ability to deliver verified carbon removal at scale.

The Varaha partnership specifically demonstrates a few important things. First, that agricultural carbon removal in developing countries can work economically and at scale. Second, that tech companies are willing to pay premium prices for durable, verified carbon removal. Third, that carbon removal projects can create multiple benefits simultaneously—carbon sequestration, soil improvement, air pollution reduction, and farmer income stability.

This doesn't solve climate change. A company removing emissions that its own operations produce is better than doing nothing, but it's not a path to global decarbonization. Real decarbonization requires transforming energy systems, manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture. Carbon removal is a tool, not a solution.

But it's a tool that's becoming increasingly important and valuable. And deals like the Microsoft-Varaha agreement show that the tool is moving from theoretical possibility to practical reality, backed by real money and real corporate commitment.

For founders in the carbon removal space, investors considering climate tech, and policymakers trying to understand where climate solutions are coming from, this moment is significant. The carbon removal market, which barely existed five years ago, is now attracting major corporations and billions in capital. The technology is unproven at massive scale, verification standards are still evolving, and economic viability depends on sustained corporate demand.

But the trajectory is clear: carbon removal is transitioning from niche to mainstream. And as AI energy consumption accelerates, that transition will accelerate as well.

TL; DR

- Microsoft commits to removing 100,000 metric tons of CO2 through India's Varaha over three years, marking the company's first major Asia-based carbon removal purchase as AI emissions surge.

- Biochar production from agricultural waste is cheaper and more scalable than direct air capture, offering 180 per ton versus1,000+ per ton, while providing soil health and air quality co-benefits.

- Microsoft's emissions jumped 23.4% in 2024 despite carbon-neutral pledges, forcing the tech giant to invest heavily in carbon dioxide removal as a complement to energy efficiency and renewable energy.

- Varaha scaled carbon credit generation by 500% year-over-year in 2025, demonstrating that verified agricultural carbon removal can be delivered at meaningful scale with proper infrastructure.

- The deal signals growing market confidence in carbon removal as a viable business model, attracting capital to the sector and establishing corporate carbon removal as a permanent operating cost for energy-intensive tech companies.

FAQ

What is carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and how does it differ from carbon offsets?

Carbon dioxide removal physically extracts CO2 from the atmosphere and stores it permanently, while carbon offsets prevent future emissions (like renewable energy projects). CDR is more expensive and complex but actually reduces atmospheric carbon, making it essential for companies aiming for carbon-negative status. The Varaha biochar project is CDR because it locks carbon in soil for centuries rather than just preventing emissions.

How does Varaha's biochar process work to remove carbon?

Variaha collects agricultural waste like cotton stalks that farmers would normally burn, processes them through industrial gasification reactors at high temperatures in low-oxygen environments, and converts the biomass into biochar (a charcoal-like material). This biochar is then applied to soil where it stores carbon for centuries while improving soil health, reducing fertilizer needs, and eliminating air pollution from burning. The carbon came from the atmosphere during plant growth and stays locked in the stable biochar rather than being released through burning or decomposition.

Why is India strategically important for carbon removal projects?

India has 145 million farms producing massive volumes of agricultural waste that's currently burned (creating air pollution), lower operating costs than developed countries, favorable government policy, and degraded soils that benefit significantly from biochar improvement. These factors make India ideal for carbon removal projects—high biomass availability, economic viability, environmental urgency, and co-benefits like air quality improvement alongside carbon sequestration make projects like Varaha far more effective per dollar spent than equivalent operations in the US or Europe.

What does carbon removal cost and why is it so expensive?

Durable carbon removal typically costs

Will Microsoft actually achieve carbon-negative status by 2030 given rising AI emissions?

It's achievable but challenging. Microsoft's emissions grew 23.4% in 2024 due to AI expansion, but the company contracted for 22 million metric tons of carbon removal in that same year. If Microsoft maintains or increases removal capacity while moderating emissions growth through efficiency improvements, hitting carbon-negative by 2030 is possible. However, carbon removal credit prices could increase, projects might underperform, or new competing buyers could emerge, creating risks to the target. Most likely Microsoft achieves 90-95% carbon-negative rather than perfectly negative.

What happens if agricultural carbon removal projects fail or farmers stop participating?

Variha's carbon removal depends on sustained farmer participation across 40,000+ farms, reliable biomass supply, consistent biochar application, and accurate monitoring. Project failure risks include carbon credit price collapse reducing farmer incentives, weather disruption affecting biomass availability, policy changes disrupting agricultural practices, or verification failures disqualifying credits. This is why Varaha focuses on co-benefits like soil improvement and reduced fertilizer costs—these economic benefits sustain farmer participation even if carbon credit values fluctuate.

How is carbon removal verified and what proves the carbon actually stayed removed?

Verification organizations like Verra and Gold Standard audit projects using specific methodologies that account for biomass collection, processing, application, and indirect emissions (energy used in operations). For biochar, verification includes tracking from farm collection through field application using digital monitoring systems, independent audits, and long-term soil monitoring. However, some uncertainty remains—biochar is believed to persist for centuries based on research but hasn't been directly observed for centuries. Project durations of 15 years provide confidence but not absolute certainty about permanent sequestration.

Why is Microsoft investing in carbon removal when it could just use renewable energy?

Renewable energy transition takes decades, and current grids can't supply 100% renewable power to all data centers even with investment. Microsoft's AI business is growing so fast that energy consumption is outpacing efficiency improvements and renewable deployment. Carbon removal provides an immediate solution to offset growing emissions while renewable transitions continue. The "emissions plus removal" model acknowledges that energy-intensive industries like AI can't completely eliminate emissions in the short term, so removal of remaining emissions becomes necessary.

Quick Tips for Understanding Corporate Carbon Removal Strategy

Key Takeaways for Industry Decision-Makers

The Microsoft-Varaha deal signals several important trends in corporate climate action:

Carbon removal is moving from promise to practice. Companies are now deploying hundreds of millions in capital toward verified carbon removal, creating a real market where once there was speculation.

Agricultural carbon removal is economically viable at scale. Biochar projects can deliver carbon removal profitably while creating soil health and pollution reduction co-benefits, making them attractive investments for both corporations and startups.

Asia represents the frontier for carbon removal scaling. With abundant agricultural biomass, lower operating costs, and severe environmental challenges from burning, developing countries like India will drive the majority of future carbon removal capacity.

Energy-intensive tech companies will spend billions on carbon removal as a permanent operating cost. If Microsoft is committing hundreds of millions annually, other cloud and AI companies will follow, creating sustained demand that attracts innovation and investment.

Verification and permanence remain unsolved challenges. Carbon removal credit quality depends on rigorous monitoring and verification systems that are still evolving. Investment in verification infrastructure will be as important as investment in removal technology itself.

For tech companies, this means: carbon removal is no longer optional for reaching sustainability targets. For startups, it means opportunity in carbon removal, verification, and monitoring technologies. For policymakers, it suggests that market mechanisms can scale climate solutions faster than regulation alone.

![Microsoft's Carbon Removal Strategy: Inside Varaha's Asia-First Deal [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-carbon-removal-strategy-inside-varaha-s-asia-fir/image-1-1768469816862.jpg)