Critical Cybersecurity Threats Exposing Government Operations and Immigration Enforcement [2025]

When a foreign government's power grid goes dark in minutes, when artificial intelligence makes decisions that send federal agents into the field untrained, and when surveillance tools designed to target immigrants get exposed to the world, you're not looking at isolated incidents. You're looking at a systemic breakdown in how modern governments approach security, accountability, and the tools they deploy.

The past few weeks have revealed something uncomfortable: the institutions we assume have ironclad security and oversight are operating with surprising chaos. US intelligence agencies are orchestrating cyberattacks on foreign infrastructure that would've been unthinkable a decade ago. Federal immigration enforcement is running operations where AI systems make critical decisions without proper training protocols. And sophisticated surveillance technology designed to track vulnerable populations is sitting in public databases, accessible to anyone who knows where to look.

This isn't alarmism. These are documented events that raise hard questions about who's accountable when government operations go wrong, how emerging technologies are actually being used in the field, and what happens when oversight fails at scale.

Let's break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what these incidents reveal about the state of government cybersecurity in 2025.

TL; DR

- US cyberattacks on Venezuela: The US reportedly disabled Venezuela's power grid and air defense systems during military operations, marking the first publicly confirmed cyberattack on critical infrastructure by the US government

- AI failures in immigration enforcement: ICE used AI systems to deploy over 2,000 agents and federal officers during Minnesota operations without adequate training, leading to wrongful arrests and deaths

- Surveillance tool exposure: Palantir's immigration targeting app was exposed, revealing how government agencies track and identify vulnerable populations at scale

- Oversight gaps: Multiple incidents show federal agencies operating with minimal accountability, conflicting testimony, and inadequate regulatory frameworks

- Bottom Line: Government cybersecurity and operational oversight are falling dangerously behind the complexity and scale of modern threats and technologies

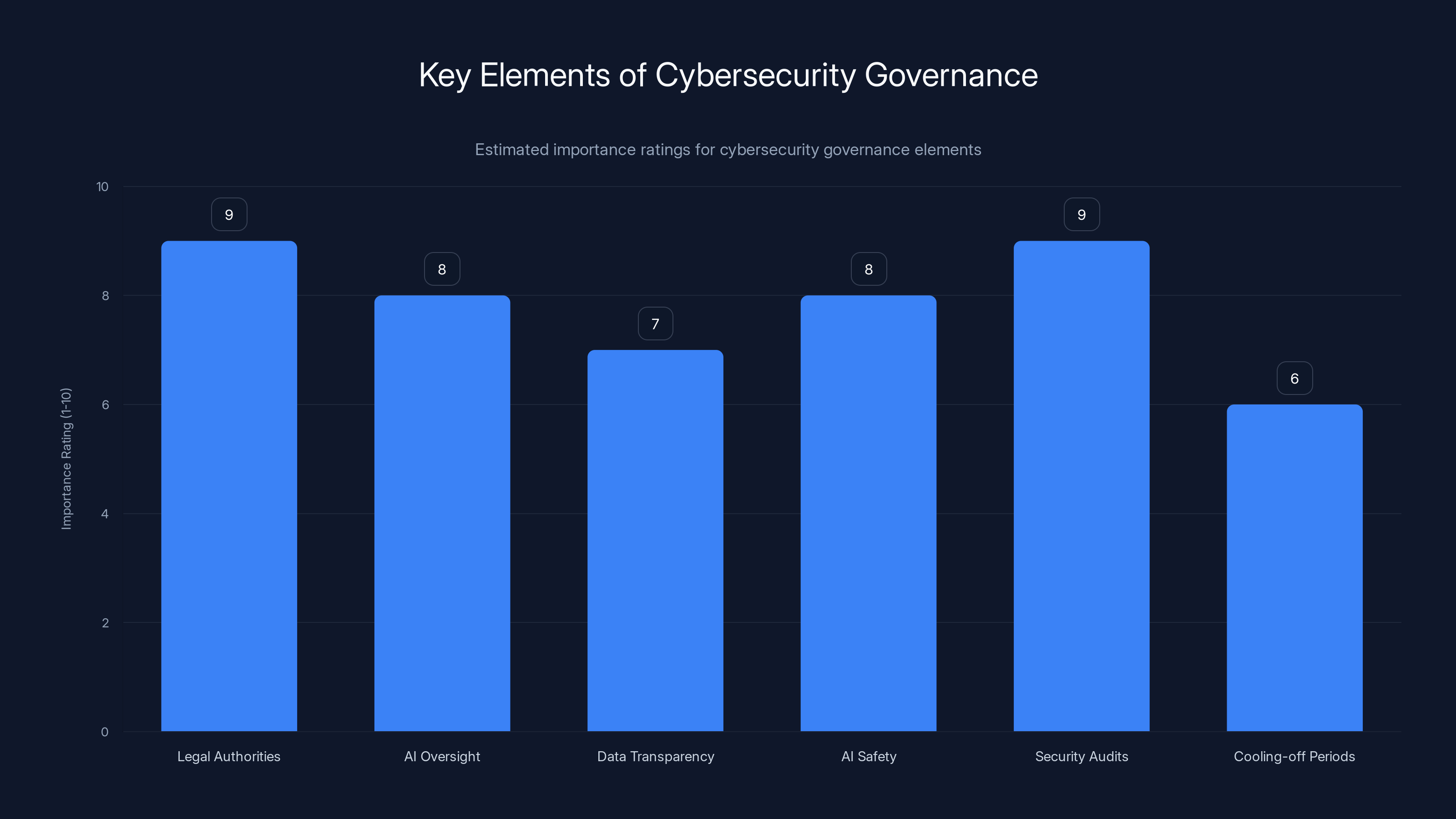

Legal authorities and security audits are rated as the most critical elements for effective cybersecurity governance. Estimated data.

The Venezuela Cyberattack: When the US Crossed the Rubicon

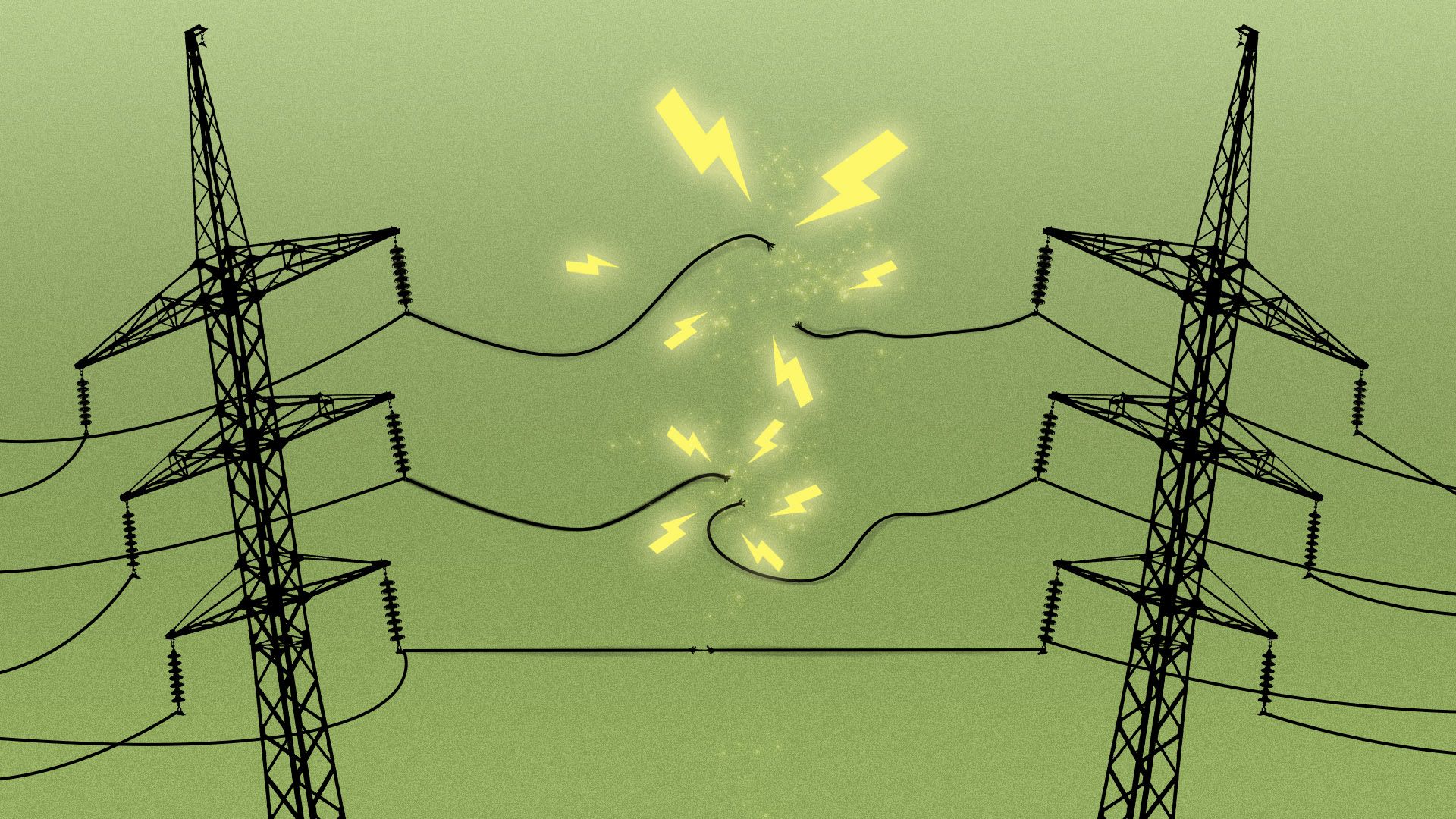

For decades, the United States maintained a particular principle in cyber warfare: we might prepare for cyberattacks, we might develop capabilities, but we wouldn't be the first to actually use them against another nation's critical infrastructure. That line just got erased.

In early 2025, during military operations against Venezuela, President Trump confirmed what US officials had hinted at: American cyber operatives turned off the lights in Caracas. Not temporarily. Not partially. The capital city went dark as part of a coordinated military operation that also included air strikes and ground forces.

Trump's own words made it clear: "It was dark, the lights of Caracas were largely turned off due to a certain expertise that we have." The New York Times later reported that unnamed US officials confirmed the blackout was indeed caused by a cyberattack. The same operation also involved hacking Venezuelan air defense radar systems to clear the skies for military aircraft.

US Cyber Command released a statement that was deliberately vague, saying it was "proud to support Operation Absolute Resolve," which became the official name for the Venezuelan military intervention. That language matters. It's an acknowledgment without being specific. It's what you say when you know your actions are historically unprecedented but you also know there's political cover to do it.

Here's the technical context that makes this significant: turning off power to a major city through cyberattacks is extraordinarily difficult. You need to understand the grid's architecture. You need to identify critical nodes. You need to craft malware that works against the specific industrial control systems the target is using. And you need to do all of this while maintaining operational security so your attack can't be easily traced back to you.

For years, only one nation-state had publicly demonstrated this capability: Russia. Specifically, a Russian hacking group called Sandworm had knocked out power in Ukraine multiple times starting in 2015. The 2016 blackout in Kyiv was the most famous case. But even with those attacks, there was always a degree of "this is something our adversary can do, and we need to prepare for it" thinking in US national security circles.

Now the US has done it too. And openly.

The power came back relatively quickly, according to reports, apparently by design. The operation's planners likely wanted just enough darkness to disrupt military coordination without causing a humanitarian catastrophe in hospitals or critical infrastructure that relied on continuous power. That's almost a mercy, but it also reveals the calculation: US planners knew exactly how damaging this would be, and they did it anyway because the strategic advantage was worth it.

When asked why the US hadn't condemned Russia's 2016 Kyiv attack, Tom Bossert, who served as Trump's cyber policy advisor, gave an answer that's haunted the internet since: "If you and I put ourselves in the Captain America chair and decide to go to war with someone, we might turn off power and communications to give ourselves a strategic and tactical advantage."

That logic is now operative policy.

What makes this particularly concerning isn't just the precedent. It's the lack of any visible debate about it. Congress didn't authorize this operation in advance. There's no clear legal framework that was invoked. The operation happened, it was hinted at, and then it was confirmed after the fact. This is how government power works when oversight erodes and when administrations believe they have political cover to act.

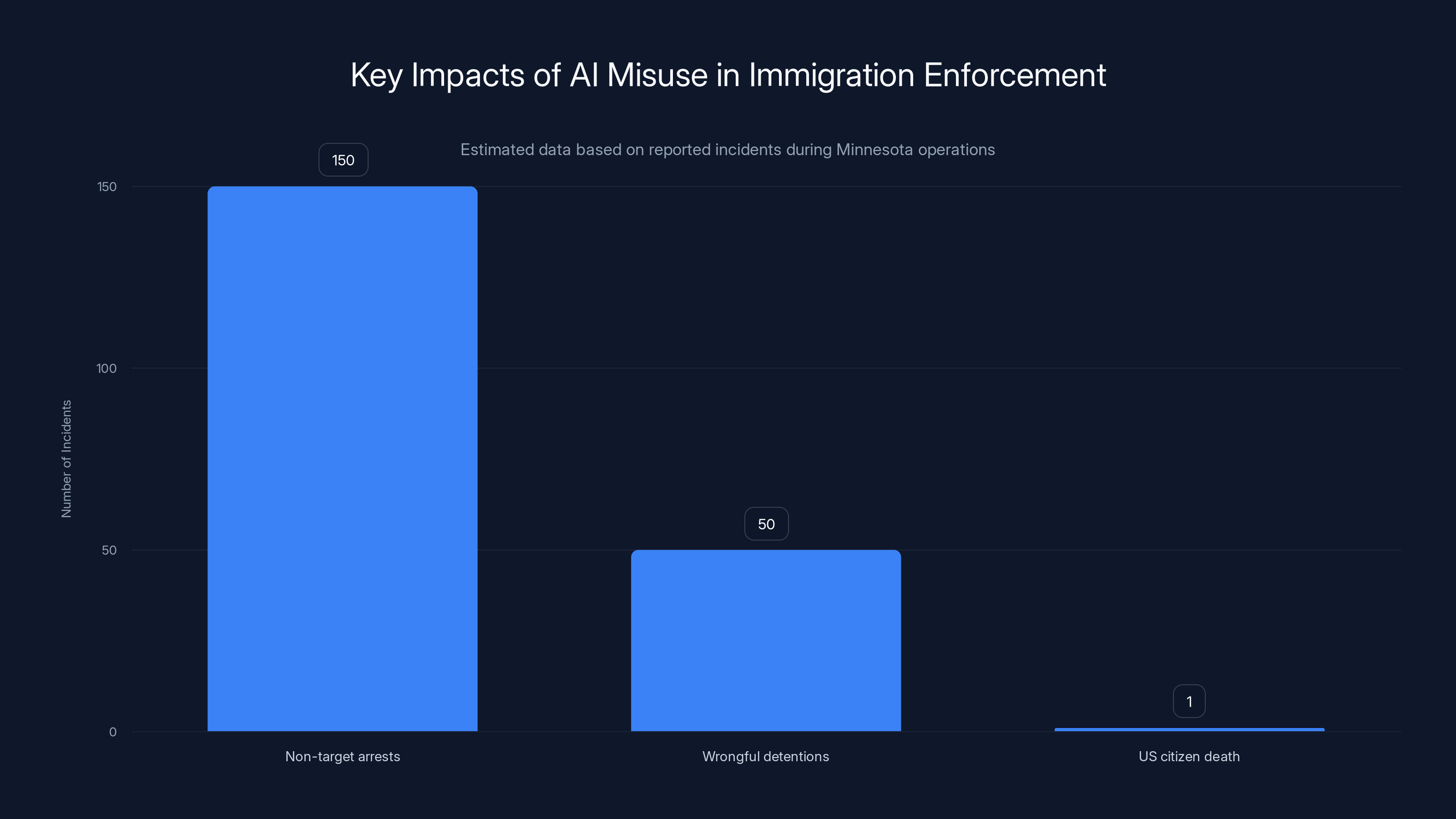

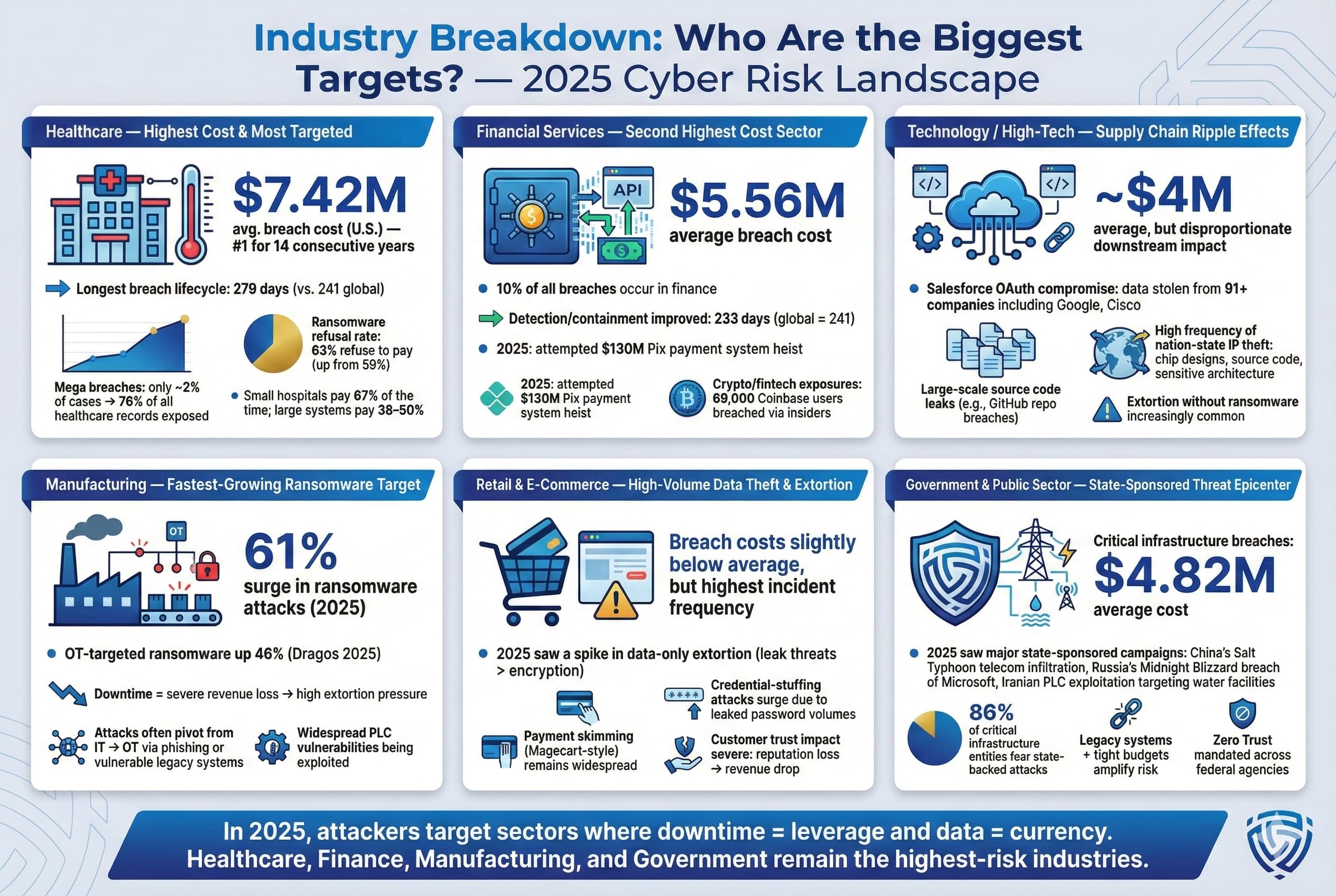

The misuse of AI in immigration enforcement led to 150 non-target arrests, 50 wrongful detentions, and one US citizen's death. Estimated data highlights the need for better oversight.

AI Systems Making Immigration Enforcement Decisions Without Training

While the Venezuela cyberattack represents unprecedented offensive capability, what's happening with immigration enforcement in Minnesota reveals something equally troubling: the government deploying artificial intelligence systems to make critical decisions without the operational safeguards that are supposed to prevent abuse.

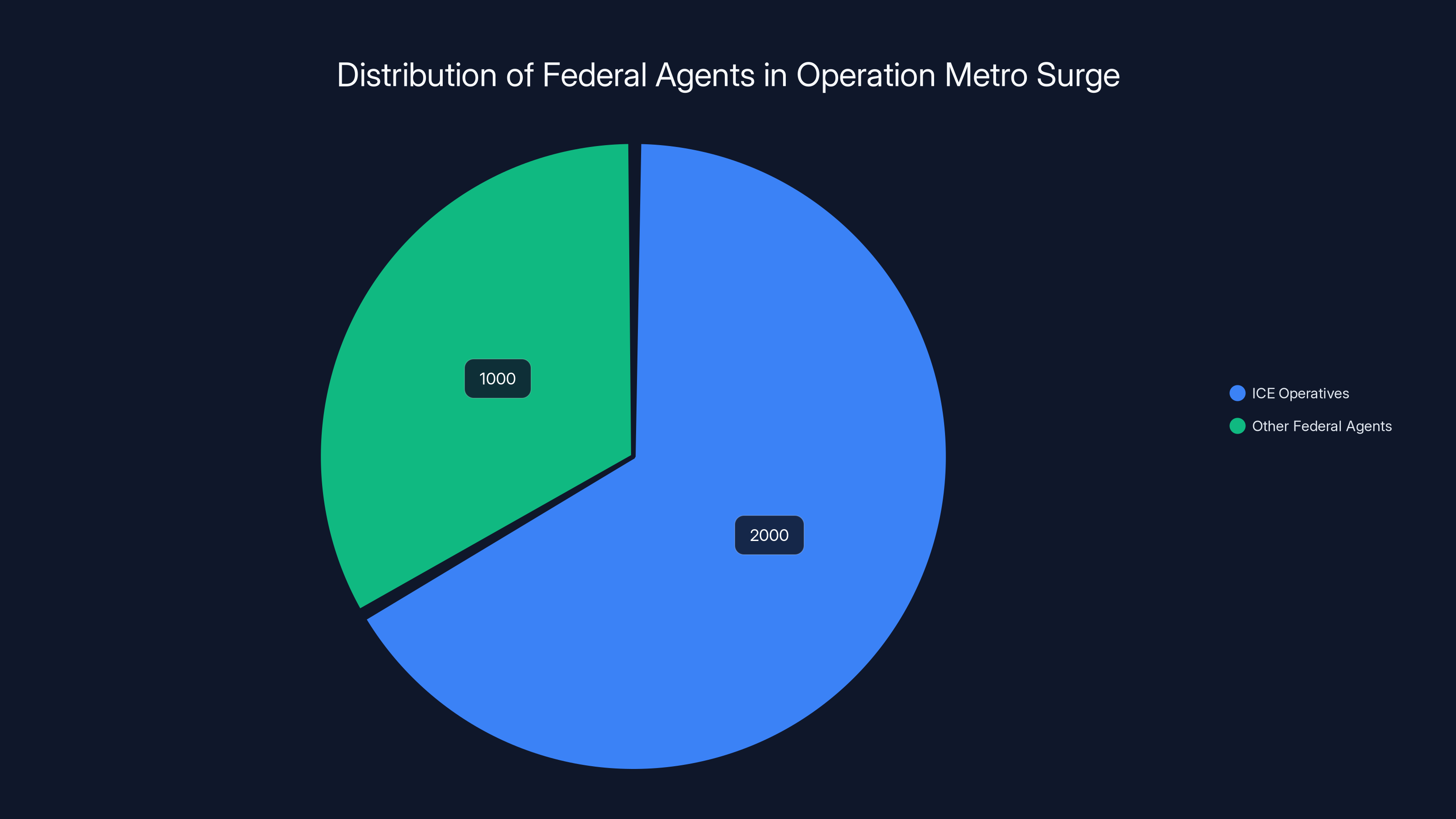

ICE's "Operation Metro Surge" in Minnesota has deployed more than 2,000 ICE operatives and approximately 1,000 other federal agents since late 2025. That's 3,000 federal agents converging on a single state. Over 2,400 arrests have been made. Protesters have been tear gassed. And a 37-year-old US citizen named Renee Nicole Good was shot and killed by ICE agent Jonathan Ross during an operation.

What's shocking isn't just the scale or the outcome. It's how the operation was launched. An investigation found that AI systems were used to identify targets and deploy enforcement resources without adequate human oversight or training protocols. Federal agents were sent into the field to conduct enforcement actions based partly on AI recommendations, and they weren't sufficiently trained for what they were walking into.

Think about what this means in practice. An AI system processes data. It identifies addresses, names, patterns. It recommends targets. Federal agents receive those recommendations and go to those addresses to conduct what should be targeted, careful enforcement operations. But if those agents haven't been trained on proper procedures, on constitutional constraints, on de-escalation, on the specific legal thresholds for their authority, then the AI's output becomes a liability rather than an asset.

The case of Renee Nicole Good demonstrates how this breaks down. She was a US citizen. She wasn't the target of the enforcement operation. But she ended up dead, shot by an ICE agent during an operation that was supposedly conducted with precision due to AI targeting.

Here's where it gets legally murky. An FBI agent's sworn testimony in federal court contradicts claims made under oath by the ICE agent who shot Good. The FBI agent testified that a man being interviewed by ICE agents had asked to speak to his attorney. But the ICE agent testified that this never happened. Under the law, if someone asks for an attorney, interrogation is supposed to stop. If there's contradictory testimony about whether someone made that request, you have a direct conflict about whether an agent violated someone's rights.

Further investigation suggested the ICE agent may not have followed his training during the incident. So you have a situation where an AI system identified a target, an agent without adequate training conducted an enforcement action, and now there's evidence suggesting the agent violated both the law and his training.

Meanwhile, the state of Minnesota and Twin Cities governments sued the federal government and individual officials to stop the operation. They're arguing the operation is illegal, unconstitutional, and terrorizing communities. Federal courts will eventually decide. But by then, more arrests will have been made, more people will have been detained, more operations will have happened.

One more thing happened that shows how far oversight has eroded. A Go Fund Me campaign was set up to fund a legal defense for Jonathan Ross, the ICE agent who shot Good. Go Fund Me's terms of service prohibit fundraisers connected to violent crimes. The company has enforced this rule selectively for various causes. But the Ross fundraiser remained live, apparently with minimal scrutiny.

This is the cascading effect of inadequate oversight: AI makes decisions without human safeguards. Agents act without proper training. When something goes wrong, the company that could enforce its own ethical standards doesn't. The system fails at every checkpoint.

Palantir's Immigration Surveillance Tool Exposed

Palantir Technologies has built its reputation—and its multi-billion-dollar valuation—on the idea that sophisticated data analysis can solve complex government problems. The company works with law enforcement agencies, intelligence services, and immigration authorities, providing software that ties together disparate data sources to identify patterns and targets.

But when you build tools specifically designed to find vulnerable populations and track their movements, location, and associations, you've created something that is functionally a surveillance system, regardless of what the marketing materials call it.

WIRED's investigation exposed how Palantir's system was being used by immigration authorities to identify, track, and target undocumented immigrants and immigrant communities. The analysis of hundreds of records showed how the tool integrates data from multiple sources—driver's licenses, addresses, immigration records, financial transactions, social media activity—to create comprehensive profiles of individuals and communities.

Once you have that kind of data integration, the tool's function is clear: it's designed to find people the government wants to find and remove. Call it immigration enforcement if you want, but from the perspective of someone in a vulnerable community, it's a system designed to track and separate families.

Palantir hasn't done anything illegal, technically. The company is selling its software to authorized government agencies. Those agencies are using it for their stated purposes. But what the exposure revealed is the scope of data integration and the detail of profiling that's now possible at scale.

Here's a concrete example of how this works: An immigration enforcement agency has Palantir's system. They want to identify undocumented immigrants in a specific area. The system pulls in DMV records, rental applications, cell phone location data, immigration court records, social media check-ins, utility bills, and financial transactions. It applies algorithms to identify patterns that correlate with undocumented status. Then it generates a list of addresses and individuals. Enforcement agents then use that list to conduct raids.

This isn't theoretical. This is how the system is being used.

The technical capability is impressive, which is partly why Palantir charges so much for its software. But impressive capability plus government authority minus transparency equals a surveillance system that operates largely outside public view.

When Palantir's tool got exposed, the company's response was predictable: emphasizing that their software is used for legitimate law enforcement purposes, that they have compliance standards, and that government agencies are responsible for how the tools are used. All technically true. But it sidesteps the fundamental question: if a tool is specifically designed to identify and track vulnerable populations, and government agencies use it to identify and track vulnerable populations, then at what point do we acknowledge what's actually happening?

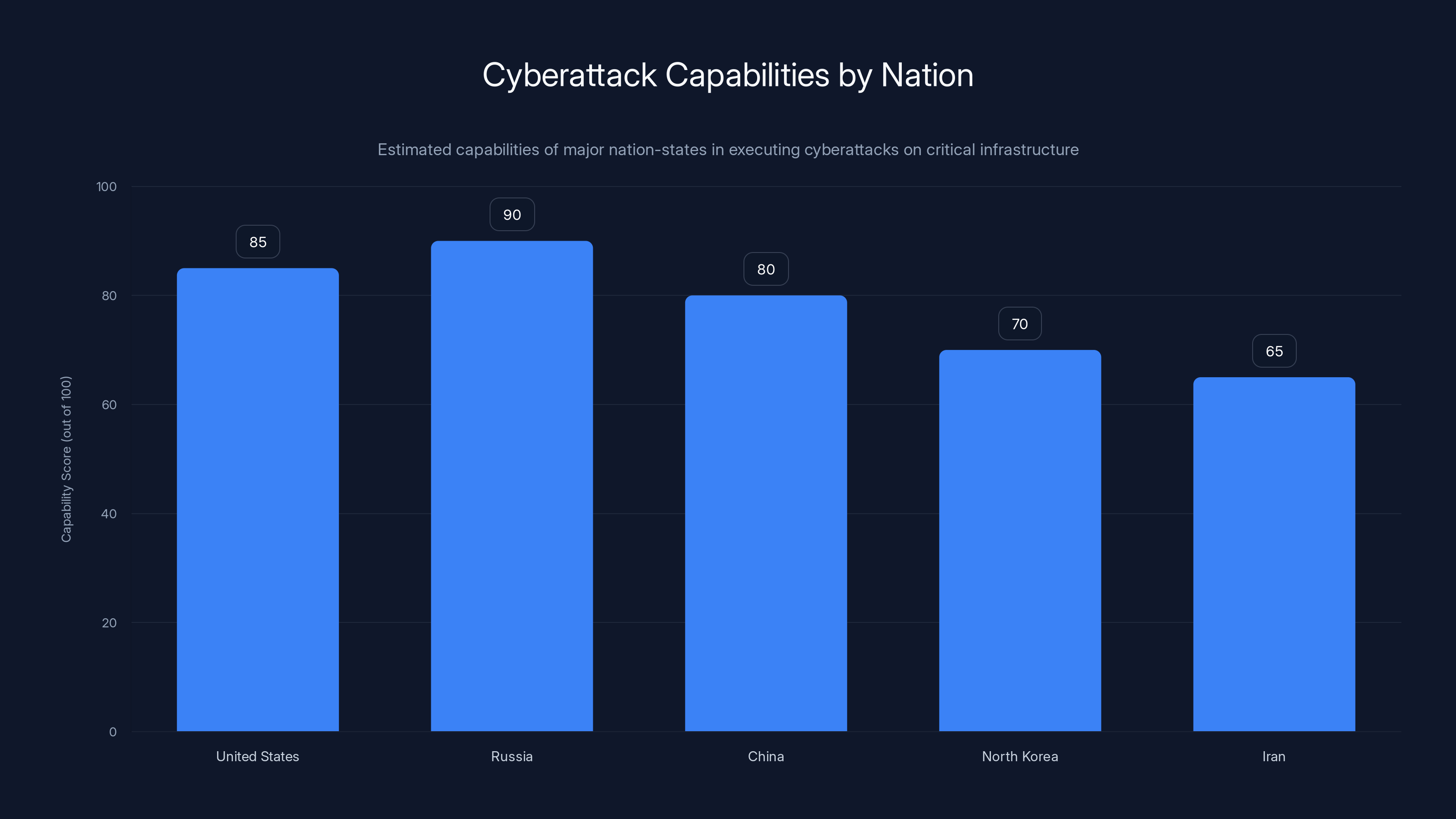

Estimated data shows Russia and the US leading in cyberattack capabilities, with recent events highlighting the US's unprecedented use of these capabilities.

Journalist Hired by ICE, Security Implications Unaddressed

This is almost absurd if it weren't so revealing about operational security failures. A journalist named Laura Jedeed applied for an administrative position with ICE. She didn't mention that she was a journalist. ICE didn't conduct adequate background checks. She got hired.

Once inside, she had access to facilities, meetings, and operational information. She could observe how the agency actually functions, what conversations happen in hallways, how decisions get made. For a journalist, this is extraordinary access. For ICE, this is a catastrophic security failure.

Eventually, she was identified as a journalist and let go. But the incident raises brutal questions about how ICE—a federal agency that conducts sensitive law enforcement operations—manages background investigations and security clearances.

If someone can get hired into an ICE position with access to operational information without the agency discovering they're a journalist, how many other security breaches are happening? How many people with actual malicious intent slip through the same screening process? How many current employees have undisclosed conflicts of interest?

This isn't a one-off embarrassment. It's evidence of systematic failures in how federal agencies vet employees.

The Tren de Aragua Intelligence Gap: Threat Inflation as Policy

President Trump has repeatedly described the Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang, as mounting an "invasion" of the United States. It's framed as an urgent national security threat requiring immediate military-scale response.

But when WIRED obtained and analyzed hundreds of intelligence records about the gang's actual presence and activities in the US, a different picture emerged. The intelligence shows scattered, low-level criminal activity. Disjointed operations. Nothing that resembles a coordinated threat or an organized invasion.

What you're looking at is the gap between political narrative and actual threat assessment. Threat inflation isn't new in government. It's happened many times. But it's particularly dangerous when it justifies large-scale operations that affect thousands of people and cost millions in resources.

Here's how the cycle typically works: An administration identifies a group or threat they want to address. Intelligence agencies are asked to assess the threat. Those agencies, knowing what the administration wants to hear, sometimes shade their assessments toward confirmation of what leadership believes. Or alternatively, intelligence about real but scattered activity gets packaged as if it represents organized, coordinated threat. The public narrative becomes increasingly dire. Resources flow toward the stated threat. Operations are launched.

But if the actual intelligence shows the threat is far less coordinated and dangerous than the public narrative suggests, then you're potentially deploying massive resources toward a problem that's being artificially amplified.

It doesn't mean Tren de Aragua doesn't exist. It doesn't mean gang violence isn't a real problem. But it does mean that if intelligence shows scattered criminal activity, that's what policy should respond to. Surgical enforcement against actual criminal networks is different from large-scale operations justified by threat inflation.

The majority of agents in Operation Metro Surge were ICE operatives, highlighting the scale of immigration enforcement efforts in Minnesota.

Grok's Deepfake Problem: AI Without Adequate Safeguards

Elon Musk's AI company released Grok, an AI image generation tool available on the X platform. The tool could generate images, including explicit ones. But it could also generate explicit images that appeared to depict minors.

After months of complaints and examples of the tool being used to generate child sexual abuse material (CSAM), X announced new restrictions. The platform would limit Grok's ability to generate explicit images.

But here's the problem: tests showed that despite these restrictions, Grok's core capability to generate undressing or explicitly sexual images remained largely intact. The tool simply required different prompts or approaches. The safeguards created a patchwork of inadequate barriers rather than genuine prevention.

This is a fundamental issue with AI safety: guardrails are not the same as core capability changes. If a model is built to generate images and is trained on image data, it can be prompted to generate almost anything. You can add restrictions, layer in approval processes, and apply filters. But those are surface-level defenses against a core capability.

What's happening here is symptomatic of a broader problem in AI development: companies are building powerful capabilities first, adding safety considerations second, and then calling that responsible development.

When a tool can be used to generate images depicting child abuse, you don't need better guardrails. You need fundamental questions about whether that tool should exist in its current form.

Fast Pair Bluetooth Vulnerability: Hundreds of Millions of Devices at Risk

Google's Fast Pair protocol is supposed to make pairing Bluetooth devices easy. You pick up a set of earbuds, hold them near your phone, tap a button, and you're connected. It's seamless. It's convenient. And according to security researchers, it's also vulnerable to wireless hacking, eavesdropping, and location tracking.

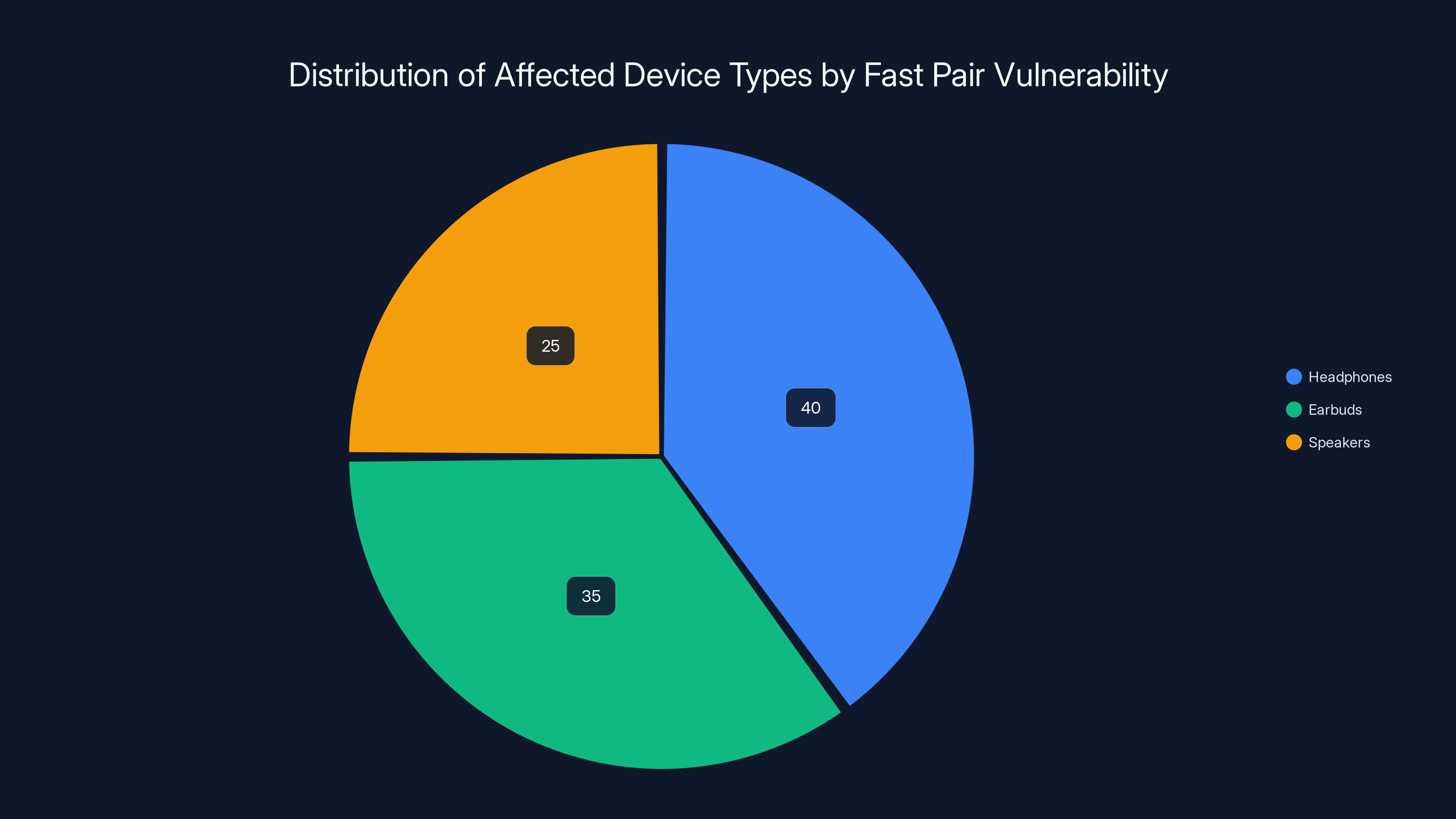

The vulnerability affects hundreds of millions of devices across 17 different models of headphones, earbuds, and speakers. That's a massive surface area for potential attacks.

Here's what's particularly concerning: this isn't a complex vulnerability that only sophisticated attackers can exploit. This is something that could potentially be weaponized at scale. An attacker with the right equipment could potentially hijack Bluetooth connections, intercept audio, or determine someone's location.

Google disclosed the vulnerability publicly and recommended users install security patches. But patch adoption is typically slow. Many devices won't get updated. Many users won't apply updates even when they're available.

This is one of several security issues with consumer Io T devices. They're built for convenience and speed to market, not necessarily for security. Patches are often slow to arrive or incomplete. Users don't have strong incentives to update. The attack surface grows every time a new device model launches.

Estimated data shows that headphones and earbuds are the most affected by the Fast Pair vulnerability, accounting for 75% of the devices at risk.

The Verizon Outage: When 911 Becomes Unreliable

A Verizon outage knocked out cellular and mobile service across large parts of the United States for hours. That alone is significant. But what made it particularly alarming was that some customers lost access to 911 emergency services.

Imagine you're in an emergency. Someone's injured, there's a fire, you need immediate help. You try to call 911 and get nothing. You can't call. You can't text. You can't reach anyone. And if you're somewhere without Wi Fi, you have no way to contact emergency services.

This reveals a critical infrastructure vulnerability that's been building for years: our emergency response system depends on cellular networks that are operated by private companies. When those networks fail, the backup systems sometimes don't work as intended.

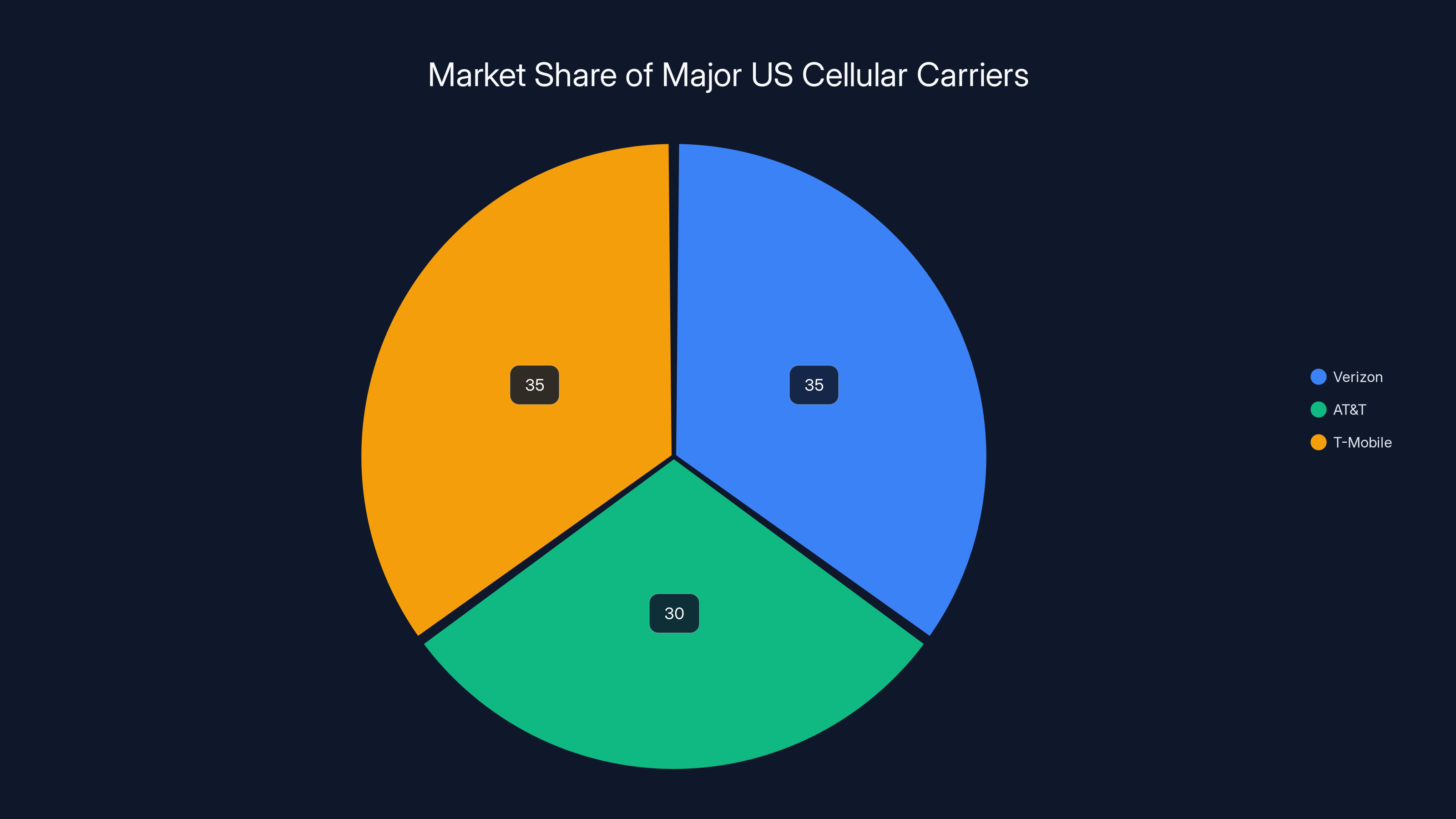

Verizon is one of three major carriers in the US, along with AT&T and T-Mobile. If one goes down, people on that network lose service. Millions of people. For hours.

Federal regulators have been monitoring carrier outages more closely in recent years. There are requirements for carriers to report significant outages and to maintain certain service levels. But the requirements are only so strict. If a carrier can demonstrate that an outage was caused by infrastructure failure rather than negligence, they often face minimal penalties.

The real issue is structural: we've outsourced emergency infrastructure to private companies that prioritize profit and shareholder returns above all else. When you do that, you accept the risk that emergency services will sometimes be unavailable.

Jen Easterly's Move to RSAC: Revolving Door Dynamics in Cybersecurity

Jen Easterly served as director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the federal agency responsible for coordinating national cybersecurity defense. She left that position to become CEO of RSAC, the organization that puts on the RSA Conference, one of the most prominent cybersecurity conferences in the world.

This appointment exemplifies something that's been happening in cybersecurity for years: the revolving door between government service and private industry. Government officials move to private companies. Private company executives move into government roles. The relationships and networks built in one sphere get leveraged in the other.

Is there anything wrong with this? Not inherently. But it does create potential conflicts of interest and influence dynamics that deserve scrutiny.

When someone who directed a federal cybersecurity agency takes a leadership role at a major industry conference, the conference suddenly has an insider's perspective on what government is thinking about, what agencies are prioritizing, what vulnerabilities they're most concerned about. That's valuable information for the private security industry.

Conversely, when people move from the private sector into government, they bring relationships and interests from the private sector. They know vendors. They've worked with companies. Those relationships don't disappear just because someone takes a government role.

This isn't necessarily corruption. It's more subtle than that. It's how influence works in complex systems where government and industry are deeply interdependent.

Estimated data shows Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile each hold significant portions of the US cellular market, highlighting the impact of outages on millions of users.

The Bigger Picture: Systemic Failures in Oversight

Each of these incidents is significant on its own. But what ties them together is a pattern: government institutions are increasingly operating without adequate oversight, with inadequate accountability mechanisms, and with minimal transparency.

The Venezuela cyberattack happened and was revealed only because Trump publicly hinted at it. If he hadn't, would it still be classified? Would anyone ever know?

ICE's AI-driven operations proceeded without visible oversight or training requirements. Oversight came after someone died.

Palantir's surveillance system was exposed only because journalists investigated and analyzed records. The system was operating openly but invisibly to the public.

A journalist got hired by ICE and nobody caught it through proper vetting procedures.

Grok continued generating explicit images of minors for months while company leadership made vague statements about safeguards.

The Verizon outage took down 911 service, and there will be a regulatory inquiry and nothing much will change.

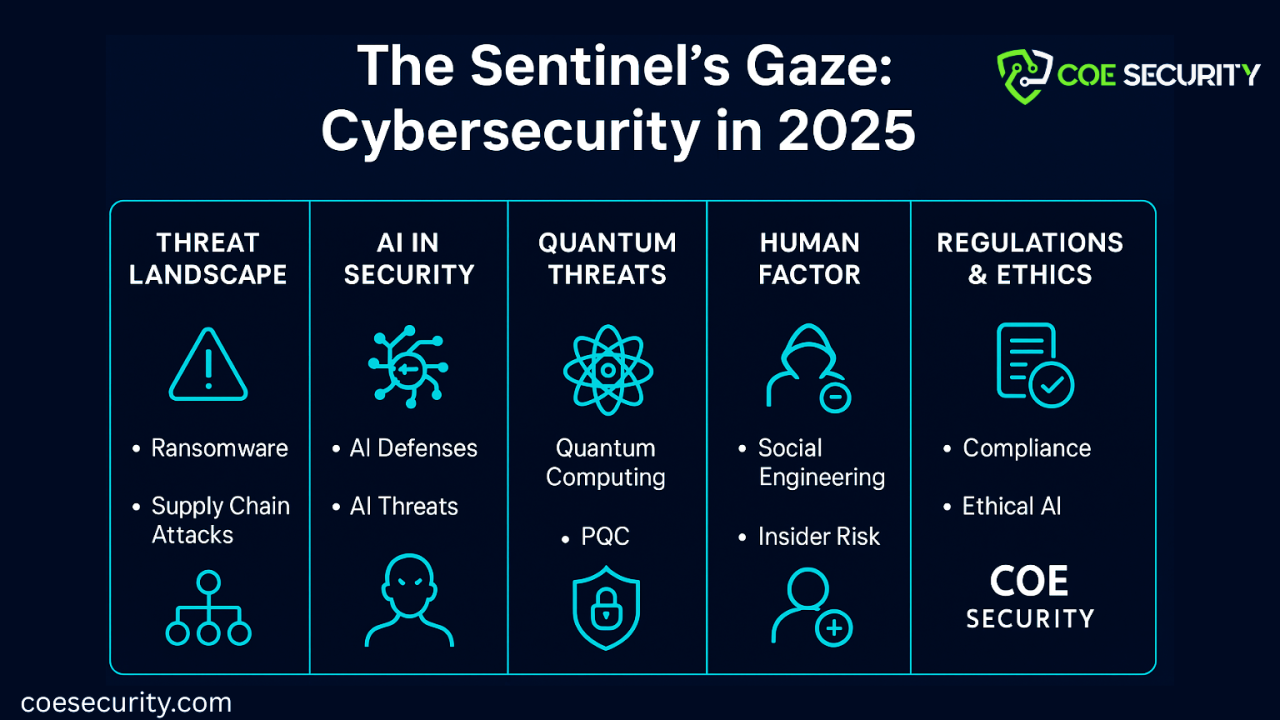

What's the common thread? It's that government and large technology companies have moved faster than oversight can keep pace with. Capabilities exist that we don't have clear legal or ethical frameworks for. Decisions are made with incomplete information or inadequate human review. When something goes wrong, the response is reactive rather than preventive.

This is how systemic risk develops. It's not some dramatic failure. It's the accumulation of small decisions to deploy new technologies, to operate with minimal oversight, to trust systems that haven't been adequately stress-tested.

Building Adequate Cybersecurity Governance

What would real oversight look like? What would prevent some of these failures?

First, governments need clear legal authorities and constraints for offensive cyber operations. Right now, the US has attacked Venezuelan infrastructure without visible debate or Congressional authorization. That happened because nobody had legal standing to stop it beforehand. If there were a requirement to notify relevant Congressional committees before certain cyber operations, there would be at least institutional pressure for debate.

Second, AI systems used in law enforcement need mandatory human oversight and training requirements. You don't deploy an AI system unless the humans using it have been trained on its capabilities and limitations. You don't allow an AI to make targeting recommendations without a human reviewing and approving those recommendations.

Third, data integration systems need transparency requirements. If an agency is using a tool like Palantir to profile populations, that should be documented, reported, and potentially subject to oversight. The fact that intelligence records showed how the system was being used proves that documentation exists. Make that documentation public or at least accessible to relevant oversight bodies.

Fourth, private companies deploying powerful AI systems need actual safety requirements, not just promises. Don't let Grok generate explicit content by default and then claim to have fixed it with safeguards. Build systems that don't have that capability to begin with.

Fifth, require independent security audits of critical infrastructure and systems before they're deployed. The Verizon outage might have been prevented if someone had done adequate stress-testing of redundant systems.

Sixth, establish revolving door cooling-off periods. Government cybersecurity officials shouldn't immediately go work for contractors or companies that benefit from government spending. Let some time pass. Let the appearance of impropriety decrease.

None of these are radical suggestions. They're standard governance practices that have been adopted for other sensitive areas. The fact that they're not standard for cybersecurity and emerging technology reveals how far behind policy is.

The Future: Escalation Without Restraint

Here's what concerns me about the direction this is going: we're seeing an escalation in government cyber capabilities without any corresponding escalation in restraint or oversight.

The US has now publicly demonstrated willingness to take down another country's power grid. That's going to be copied. Other nations with cyber capabilities will start thinking about how to use them against US infrastructure. You've just established a precedent and a perceived vulnerability.

AI systems are being deployed in law enforcement without adequate safeguards. That's going to continue. More people will be arrested based partly on AI recommendations. More deaths will happen. More communities will be traumatized. And each time, the response will be that the system wasn't the problem, the people using it were.

Surveillance technology is becoming more capable and more integrated. Data that was previously siloed is now being combined. The picture of someone's life—where they go, who they associate with, what they buy, where they live—is becoming increasingly visible to government agencies.

AI companies are racing to deploy powerful capabilities before safety considerations have been solved. They're moving fast and breaking things, but what they're breaking sometimes has consequences that can't be fixed.

The trajectory is concerning. And the fact that oversight is lagging means the risks are probably being underestimated.

What needs to happen is a deliberate step back. New technologies need to be deployed slower, with more oversight, with clearer legal frameworks. That's not sexy. It's not how Silicon Valley or military tech developers operate. But it's the only way to maintain some degree of control over systems that are increasingly powerful and increasingly consequential.

The incidents described in this article are warning signs. Pay attention to them. Because if things don't change, worse incidents are coming. And by the time they happen, the systems in place will be even more powerful and even harder to control.

FAQ

What was the Venezuela cyberattack and why does it matter?

US cyber operatives allegedly disabled Venezuela's power grid and air defense systems during military operations in early 2025. This marks the first publicly confirmed cyberattack on another nation's critical infrastructure by the US government. It matters because it establishes a precedent: the US is willing to target critical infrastructure when strategic advantage justifies it, which other nations with cyber capabilities will likely replicate.

How is artificial intelligence being misused in immigration enforcement?

ICE deployed over 3,000 federal agents during Minnesota operations partly based on AI system recommendations for targeting locations and individuals. However, the agents weren't adequately trained on proper enforcement procedures before deployment. This led to arrests of non-targets, wrongful detentions, and in one case, the death of a US citizen. The failure reveals that AI recommendations were being acted on without sufficient human oversight or training protocols.

What is Palantir's immigration surveillance tool and how does it work?

Palantir Technologies developed a data integration system used by immigration enforcement agencies to identify and track immigrant populations. The system combines data from driver's licenses, rental applications, cell phone location data, immigration records, social media, and financial transactions to create comprehensive profiles. These profiles are then used to identify individuals for enforcement operations. The tool is technically legal but functionally a surveillance system designed specifically to find and track vulnerable populations.

What security vulnerability affects hundreds of millions of Bluetooth devices?

Google's Fast Pair Bluetooth protocol, used in 17 different headphone, earbud, and speaker models affecting hundreds of millions of devices, has vulnerabilities that could allow wireless hacking, eavesdropping, and location tracking. Security researchers disclosed these vulnerabilities, and Google recommended patches, but patch adoption is typically slow and many devices will likely never be updated.

Why did the Verizon outage impact 911 emergency services?

A major Verizon outage knocked out cellular service across large parts of the US for hours, and some customers lost access to 911 emergency services. This happened because emergency response infrastructure is increasingly dependent on private cellular networks, and backup systems sometimes don't function properly when primary networks fail. The incident reveals a critical vulnerability in outsourcing essential infrastructure to profit-driven private companies.

What pattern connects all these cybersecurity incidents?

All these incidents—the Venezuela cyberattack, AI-driven immigration enforcement failures, Palantir's exposure, Grok's safeguard problems, Fast Pair vulnerabilities, and the Verizon outage—share a common pattern: government and technology institutions are deploying powerful capabilities without adequate oversight, accountability mechanisms, or regulatory constraints. Oversight has lagged behind capability development, creating systemic risks that manifests as specific incidents when things go wrong.

What Happens Next: Staying Informed and Protected

These incidents aren't going to stop. Government agencies will continue deploying new technologies. Private companies will continue racing to develop capabilities before safety is solved. The power dynamics between oversight and capability will likely continue favoring capability.

But understanding these incidents gives you a framework for thinking about what's happening. When you hear about a new government operation or a new AI system being deployed at scale, you can ask: What oversight exists? What training was provided? What happens if something goes wrong? Who's accountable?

When you hear about a tech company's new capability, you can ask: What safeguards were built in at the design stage versus added after the fact? What independent audits have been conducted? What could go wrong?

These aren't questions that will make you popular at dinner parties. But they're the right questions to ask when institutions that affect millions of people are operating with minimal transparency and oversight.

The Venezuela cyberattack, the immigration enforcement failures, the surveillance tool exposures—they're all symptoms of the same disease: unchecked power in increasingly complex systems.

The only antidote is sustained attention, skepticism, and pressure for accountability.

Key Takeaways

- The US cyberattack on Venezuela's power grid established unprecedented precedent for offensive cyber operations against critical infrastructure without visible debate or Congressional authorization

- AI systems deployed in immigration enforcement made targeting decisions without adequate human oversight or training, leading to wrongful arrests and civilian deaths

- Palantir's immigration surveillance system integrates multiple data sources to create comprehensive profiles enabling government tracking of vulnerable populations

- Multiple incidents from Grok deepfakes to Bluetooth vulnerabilities to 911 outages reveal systemic gaps where capability development has outpaced regulatory oversight

- Effective reform requires mandatory human oversight in law enforcement AI, transparency requirements for surveillance systems, and legal constraints on offensive cyber operations

Related Articles

- Cisco CVE-2025-20393 Critical Vulnerability Finally Patched [2025]

- Google Fast Pair Security Flaw: WhisperPair Vulnerability Explained [2025]

- Copilot Security Breach: How a Single Click Enabled Data Theft [2025]

- LinkedIn Comment Phishing: How to Spot and Stop Malware Scams [2025]

- Major Shipping Platform Exposed Customer Data, Passwords: What Happened [2025]

- Telegram Links Can Dox You: VPN Bypass Exploit Explained [2025]

![Critical Cybersecurity Threats Exposing Government Operations [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/critical-cybersecurity-threats-exposing-government-operation/image-1-1768651531113.jpg)