The Ancient Practice Your Immune System Has Been Waiting For

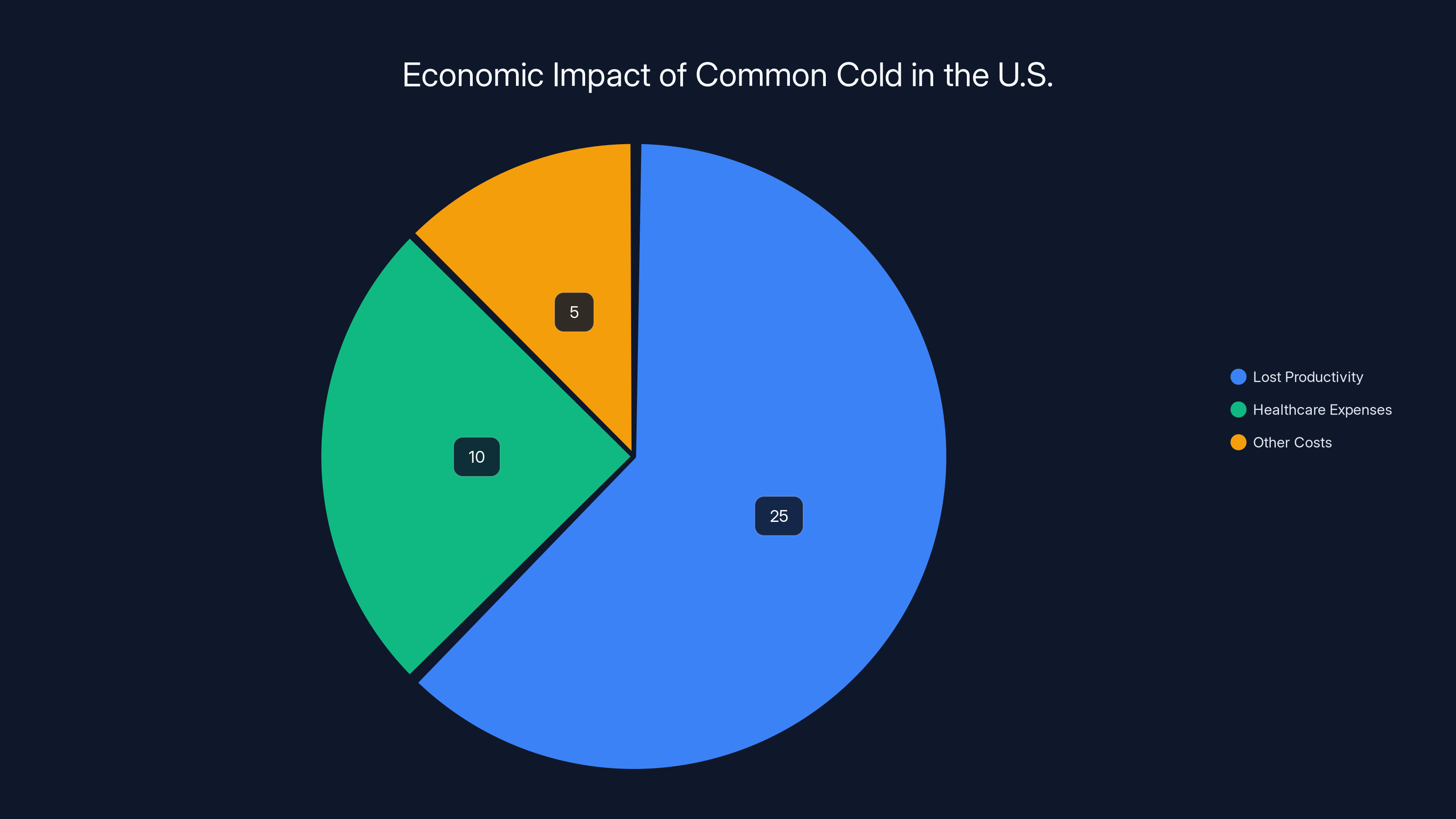

You probably wake up some morning in October feeling that familiar tickle in your throat. You know what's coming. Within hours, the sniffles turn into congestion, the congestion turns into that annoying cough that keeps you up at night, and suddenly you're down for the count for a week. This happens to the average American between two and three times every winter, costing the economy roughly $40 billion annually in lost productivity and healthcare expenses.

Here's what makes this frustrating: we've known how to treat basically every other infectious disease. Antibiotics changed the game for bacterial infections. Vaccines have eliminated smallpox entirely. But the common cold? We're still stuck with chicken soup recommendations and over-the-counter medicines that do almost nothing. The problem is that the common cold isn't actually one disease—it's caused by more than 200 different viral pathogens, making it nearly impossible to develop a single treatment.

But what if the answer isn't some high-tech pharmaceutical breakthrough? What if it's something so simple, so old, and so cheap that modern medicine spent decades dismissing it out of sheer skepticism?

Enter nasal saline irrigation, a practice that originated in Ayurvedic medicine more than 5,000 years ago. For millennia, practitioners in the Indian subcontinent have been washing out nasal passages with saltwater solutions. It wasn't because of rigorous clinical trials or published research—it was because people observed that it worked. That ancient practice is now experiencing a legitimate scientific renaissance, backed by large-scale studies from respected institutions. And the data is compelling enough that even skeptical Western medicine is paying attention.

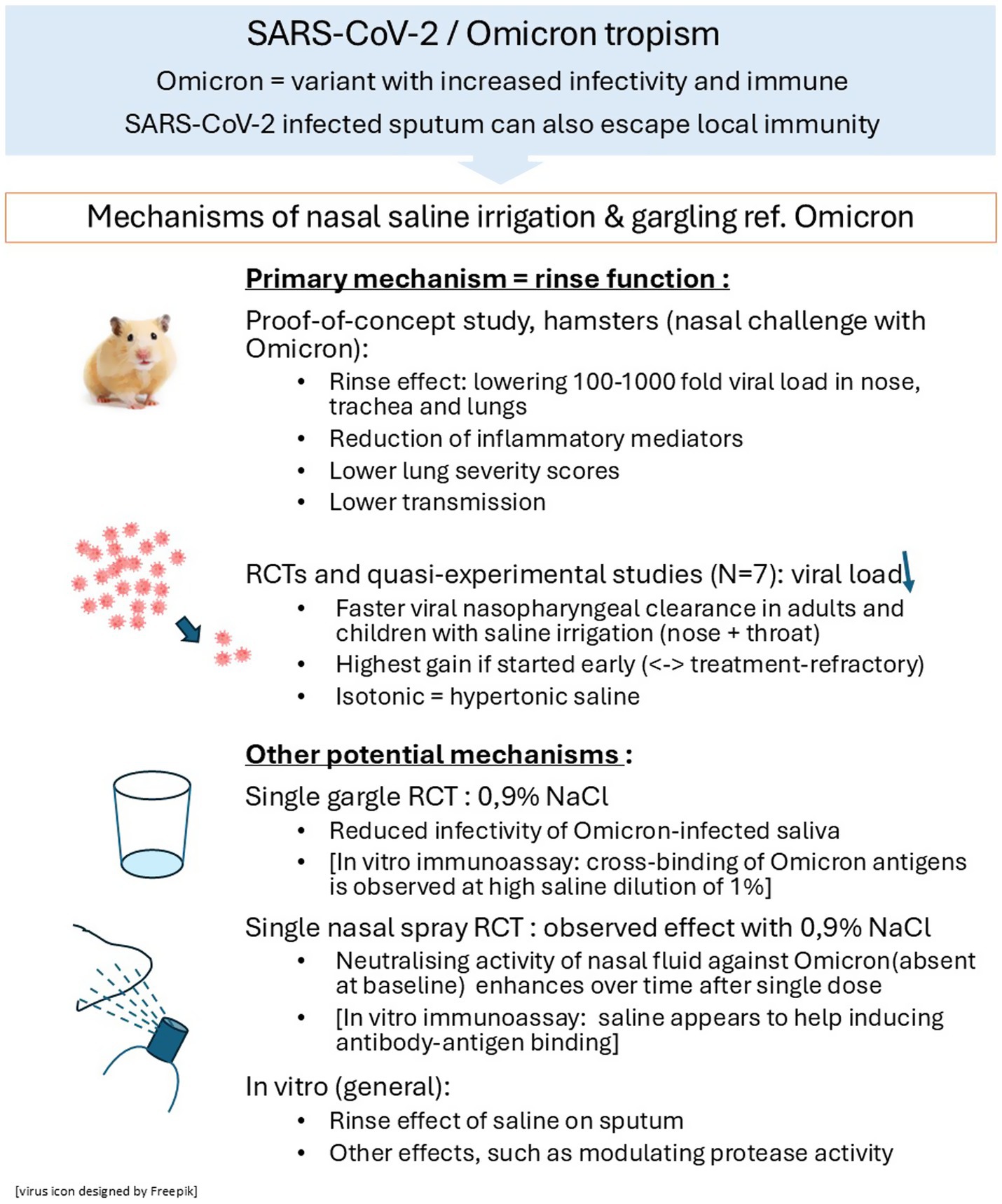

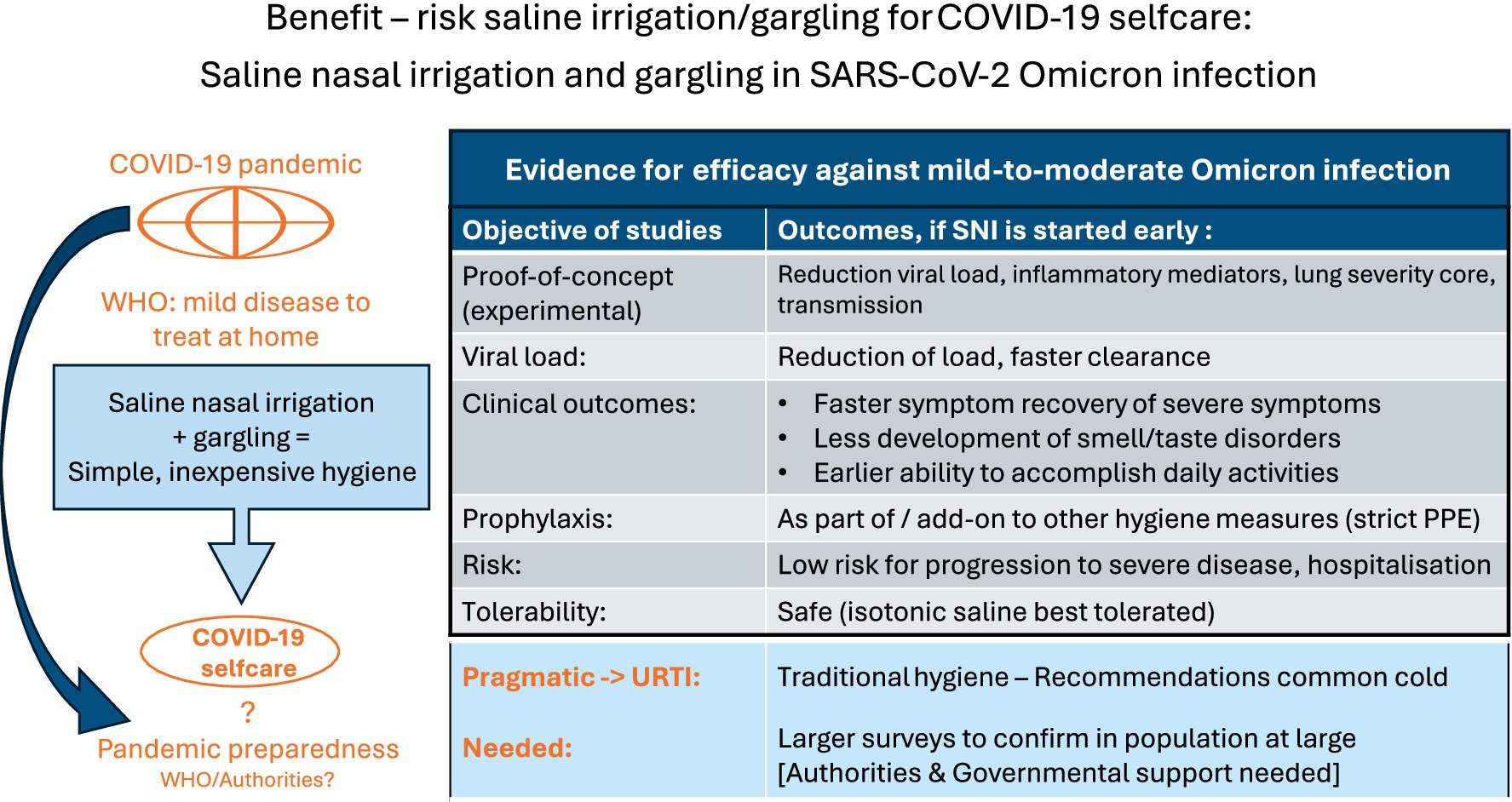

The shift happened gradually, then suddenly. For decades, nasal saline irrigation was relegated to the fringes of alternative medicine, viewed with the same skepticism people reserve for untested homeopathic remedies. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced researchers to consider every potential defense against respiratory viruses, including some they'd previously ignored. The results surprised everyone involved.

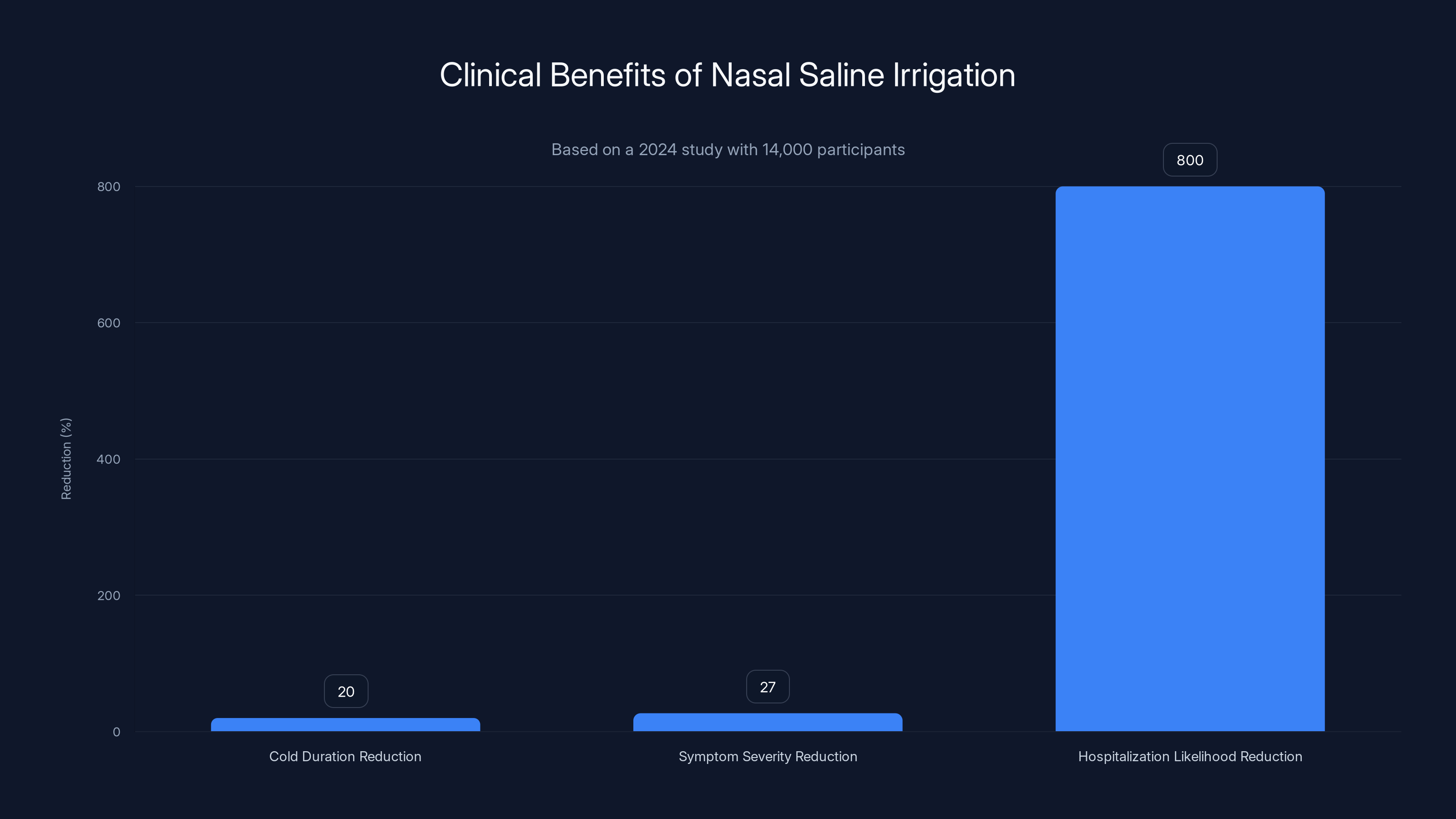

Today, we have evidence from hundreds of published studies, including several large randomized controlled trials involving thousands of participants, demonstrating that regular saline nasal irrigation actually works. This isn't a mild effect either. We're talking about measurable reductions in illness duration, decreased hospitalization rates, and lower severity of symptoms. All from saltwater and a simple spray bottle or neti pot.

The fascinating part isn't just that it works—it's understanding why it works at a cellular level. It turns out that salt isn't just passively washing away viruses. It's triggering your body's own antiviral defense mechanisms. And that mechanism, once you understand it, makes you wonder why this wasn't standard medical practice decades ago.

TL; DR

- Ancient roots with modern proof: Nasal saline irrigation, practiced for 5,000+ years in Ayurvedic medicine, now has peer-reviewed studies confirming its effectiveness

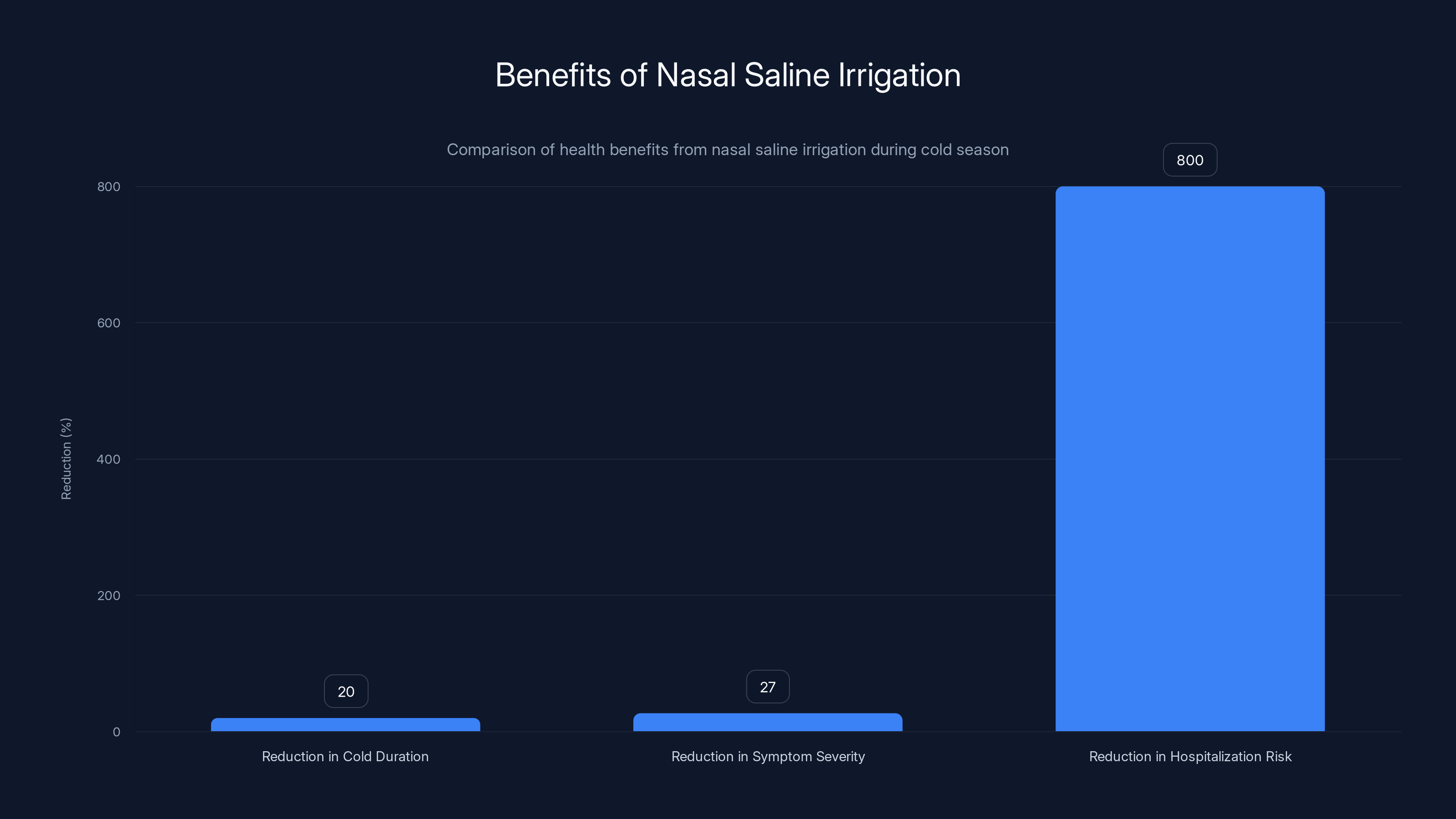

- Significant clinical benefits: Large 2024 study of nearly 14,000 people found saline nasal sprays reduce cold duration by ~20% and hospitalization risk by 8x in COVID cases

- The mechanism matters: Salt triggers production of hypochlorous acid in nasal cells, which directly inhibits viral replication at the cellular level

- Simple and safe: Requires no prescription, costs pennies, and has virtually no side effects—making it accessible to virtually everyone

- Bottom line: Starting saline nasal irrigation at the first sign of infection is one of the highest ROI preventive health practices available

The common cold costs the U.S. economy approximately $40 billion annually, with the majority attributed to lost productivity. Estimated data based on typical distribution.

Understanding Nasal Saline Irrigation: What Actually Happens Inside Your Nose

Before we discuss effectiveness, you need to understand what nasal saline irrigation actually is, because it's simpler than you might think. Despite sounding like some complicated medical procedure, it's essentially just saltwater going up your nose. The "irrigation" part just means rinsing or flushing.

There are multiple ways to do this. The traditional method involves a neti pot, which looks like a teapot with a long spout. You fill it with lukewarm saline solution, tilt your head, and pour the solution into one nostril while it drains out the other. It's not exactly comfortable the first time you try it, and it definitely feels weird, but most people adjust quickly.

The more modern approach uses a saline nasal spray—the kind you can grab at any pharmacy for a couple of dollars. You just spray it into each nostril, and the saline coats your nasal passages. No special equipment required. No learning curve. You just push the pump.

The concentration matters, though. For effective saline solutions, you're looking at isotonic saline, which means the salt concentration is roughly equivalent to what you'd find in human blood and tissues. This is typically around 0.9% sodium chloride by weight. Some people use hypertonic solutions (higher salt concentration), which can be more effective but also more irritating to the delicate nasal tissue. Isotonic tends to be the sweet spot for regular daily use.

If you want to make your own solution—and honestly, it's absurdly cheap to do—you mix half a teaspoon of salt with 8 ounces of distilled or boiled water. That's it. You now have a saline solution that costs maybe one cent. The convenience factor of buying a spray bottle is worth more than the penny you save, but the point is that this is not expensive medicine. It's not even really medicine, technically. It's just salt and water.

The key insight that surprised researchers is that this simple saline solution isn't just passively washing away viruses. When you introduce saline into your nasal passages, several things happen simultaneously, and together they create a hostile environment for respiratory viruses.

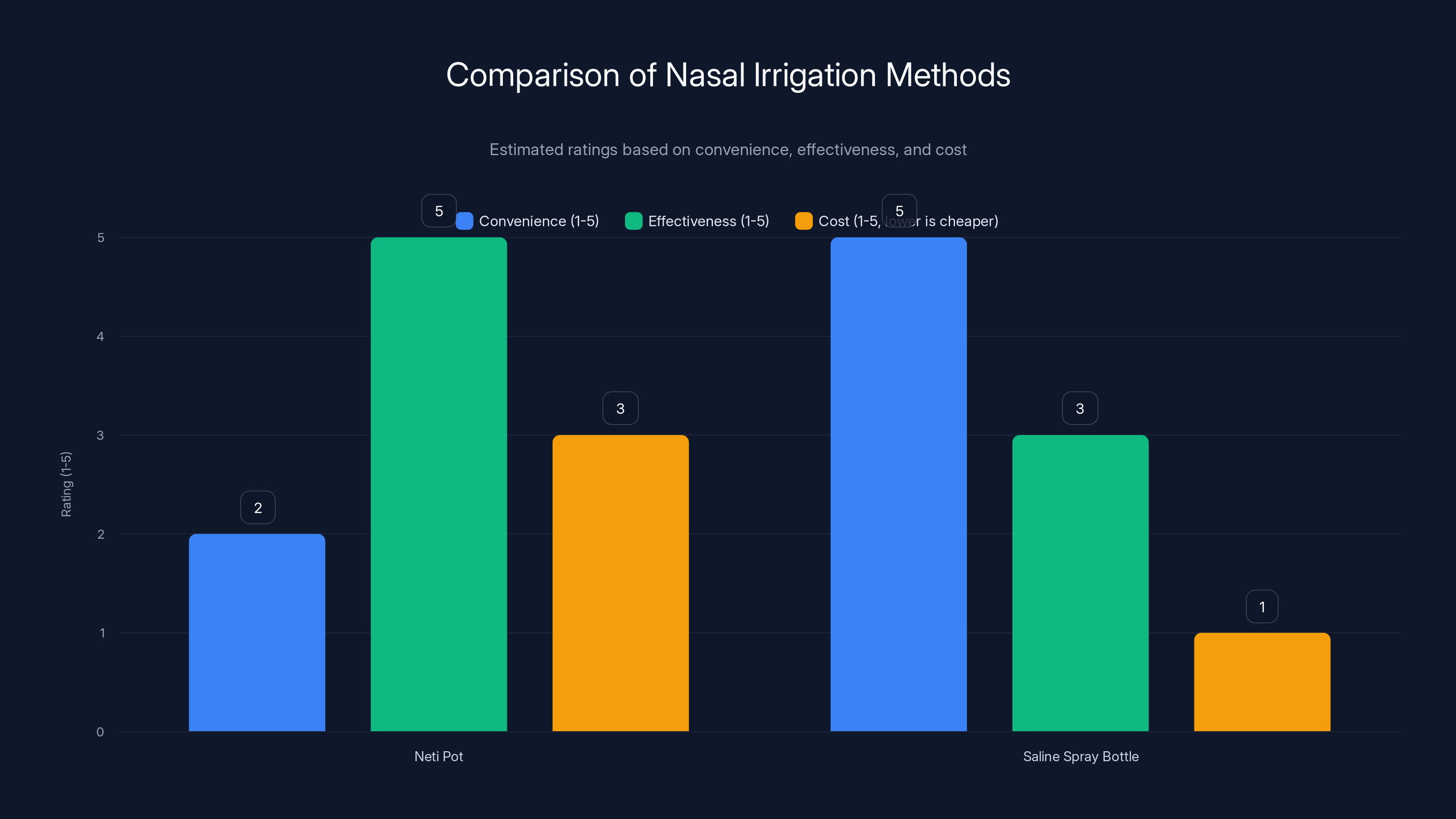

The saline spray bottle method scores higher in convenience and cost, while the neti pot is more effective. Estimated data based on typical user experiences.

The Cellular Mechanism: How Salt Literally Stops Viruses From Replicating

Here's where things get genuinely interesting from a biochemistry perspective. When saline enters your nasal passages, the sodium chloride doesn't just sit there being salty. Your nasal cells actually take up the chloride ions and convert them into something much more aggressive: hypochlorous acid, which is essentially a natural disinfectant that your immune system can produce but often in insufficient quantities.

This was the breakthrough discovery that convinced skeptical researchers this wasn't just placebo effect. A researcher named Paul Little, who leads the primary care research program at the University of Southampton, ran the most comprehensive study on nasal saline irrigation published to date. His team recruited nearly 14,000 participants, gave some of them saline nasal spray and the others a placebo, and tracked outcomes for the entire cold season.

The results were unambiguous. Participants who used saline nasal spray starting at the first sign of infection—spraying three to six times daily—experienced approximately 20% reduction in illness duration. In practical terms, if you'd normally suffer through a cold for 10 days, saline could cut that down to 8 days. That doesn't sound revolutionary until you imagine that multiplied across the entire population. If even 10% of Americans used saline regularly during cold season, that would translate to millions of workdays recovered and billions in economic productivity.

But the COVID data was even more striking. One study examining people who tested positive for COVID-19 found that those who performed saline nasal irrigation for two weeks after testing positive were more than 8 times less likely to be hospitalized compared to the control group. That's not a marginal improvement. That's a dramatic difference in clinical outcomes. While you need to account for various confounding variables and the fact that this was a smaller study than Little's recent work, the magnitude of the effect was impossible to ignore.

The mechanism explaining this involves multiple layers. First, the hypochlorous acid directly attacks viral particles in your nasal passages, inhibiting their ability to replicate. But that's just the opening act. Saline also enhances the activity of your neutrophils, which are a type of white blood cell responsible for fighting off pathogens. Think of neutrophils as your body's first-responder defense force. They patrol your nasal passages looking for trouble. When you use saline, you essentially give them better working conditions to do their job.

Second, well-hydrated nasal tissue produces more robust mucus, and this mucus works like a physical trap for viruses. Imagine trying to catch something slippery with your bare hand versus trying to grab it with a sticky web. The mucus essentially encapsulates the virus, preventing it from latching onto your nasal cells and forcing its way inside. A pediatrician at Augusta University named Amy Baxter explained it in a useful analogy: hydrated mucus works like soap. Just as soap surrounds dirt particles and makes them easier to wash away, well-hydrated mucus surrounds viruses and either allows your body to swallow them (where stomach acid destroys them) or cough them up.

Third—and this is perhaps the most elegant mechanism—viruses need to attach to specific receptors on your nasal cells to penetrate and infect them. Different viruses target different receptors. Many coronaviruses, for instance, seek out something called the ACE2 receptor. Research has shown that when these receptors are stiff and dehydrated, they're much easier targets for viruses to grab onto. When they're surrounded by liquid and relatively mobile, they're harder for viruses to latch onto. It's the difference between hitting a stationary target and hitting a moving one. The virus has a much harder time establishing a grip.

Together, these mechanisms create a multiplicative defensive effect. You're not just washing away viruses. You're inhibiting their replication, enhancing your immune cells' ability to fight them, making them harder to attach to your cells, and ensuring they're trapped in mucus if they do get close. It's almost like having three different security layers, all activated simultaneously.

The Historical Skepticism: Why Western Medicine Dismissed This for So Long

If nasal saline irrigation is so effective, you might wonder why it's not universally recommended. Part of the answer lies in how Western medicine works and the cultural divide between conventional medical practice and traditional medicine systems like Ayurveda.

For much of the 20th century, Western medicine operated on the assumption that if something came from traditional medicine systems, it probably didn't work and was based on superstition rather than physiology. This wasn't entirely irrational—plenty of traditional remedies don't hold up to scrutiny. But the assumption also meant that researchers didn't seriously investigate practices that might have genuine merit simply because of where they originated.

Archived medical journals from the 19th century show that nasal saline irrigation was actually examined by Western doctors back then, but the field largely abandoned it. It was considered ineffective or at least not proven enough to warrant serious attention. The preference in modern medicine shifted toward pharmaceutical interventions—drugs that could be patented, studied in controlled trials, and sold at profit. A saline solution that anyone could make at home didn't fit that model.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced a recalibration. Suddenly, researchers were looking at every possible intervention to prevent or mitigate respiratory viral infection, including things they might have previously dismissed. That's when interest in nasal saline irrigation resurged, this time with serious funding and rigorous methodology.

The skepticism didn't disappear overnight. Early in the pandemic, the World Health Organization actually listed nasal saline irrigation on its COVID "myth buster" page, grouping it with thoroughly debunked therapies. But as the research accumulated—study after study showing benefits—the WHO quietly removed it from that list. They didn't make a big announcement about it. They just updated the page.

What's interesting is that this same thing happened with masks, hydroxychloroquine, and several other interventions during COVID. Sometimes the skepticism was warranted (hydroxychloroquine really didn't work). Sometimes it wasn't (masks did work). The saline irrigation situation falls into the second category. It worked. The evidence just took a while to accumulate and gain acceptance.

Investing

The Major Studies: What the Research Actually Shows

Let's dig into the actual research, because the evidence has gotten quite strong, and you should understand what we're basing this on.

The landmark study, published in 2024, was led by Paul Little and his team. They conducted a randomized controlled trial involving nearly 14,000 participants followed throughout the cold season in the UK. The participants were split into two groups: one received saline nasal spray, the other received placebo spray. The key detail is that participants were told to start using the spray "at the first sign of infection," and to use it between three and six times daily.

The results: 20% reduction in cold duration, and a 27% reduction in symptom severity at the peak of illness. Those numbers might not sound dramatic if you're not used to reading medical literature, but in the context of cold treatment, they're substantial. For reference, most over-the-counter cold medicines show efficacy rates in the 5-10% range. Saline was roughly 2-3 times more effective than the typical pharmacy cold medicine.

The study's follow-up, published in 2025, examined whether saline spray could prevent infection entirely, not just reduce duration. The hypothesis was that regular use of saline in the days after exposure to someone with a cold might prevent you from getting sick at all. The results were more modest than the treatment scenario, but still meaningful. Regular prophylactic saline use reduced the risk of developing symptoms by approximately 13% after known exposure.

Why wasn't the preventive effect stronger? Likely because while saline helps, it's not a complete barrier. If someone sneezes on you, you're getting viral load directly into your nasal passages. Saline can reduce your risk, but it can't eliminate it entirely. But once the virus has a foothold and you're actually developing symptoms, saline becomes much more effective because you're now fighting an active infection rather than trying to prevent one from establishing.

The COVID-specific research was conducted at a hospital in India and published in 2021. Researchers identified patients who had tested positive for COVID-19 and assigned them to either a control group or an intervention group that performed nasal saline irrigation twice daily for two weeks. The outcome measure was hospitalization rate.

In the control group, 45 out of 100 patients required hospitalization. In the saline irrigation group, only 5 out of 100 patients required hospitalization. That's the 8x reduction we mentioned earlier. Now, it's important to note that this was a smaller study, and the control group's hospitalization rate was quite high compared to other COVID studies, which suggests there might have been other factors at play. But even accounting for that, the magnitude of the effect is impressive.

What's remarkable about these studies is not just that they show benefits, but that the benefits appeared across diverse populations with different risk profiles. The studies included young healthy people, older adults, people with chronic conditions, immunocompromised individuals, and more. The consistent finding across populations suggests the mechanism is fairly robust.

Variations in Application: Finding Your Method

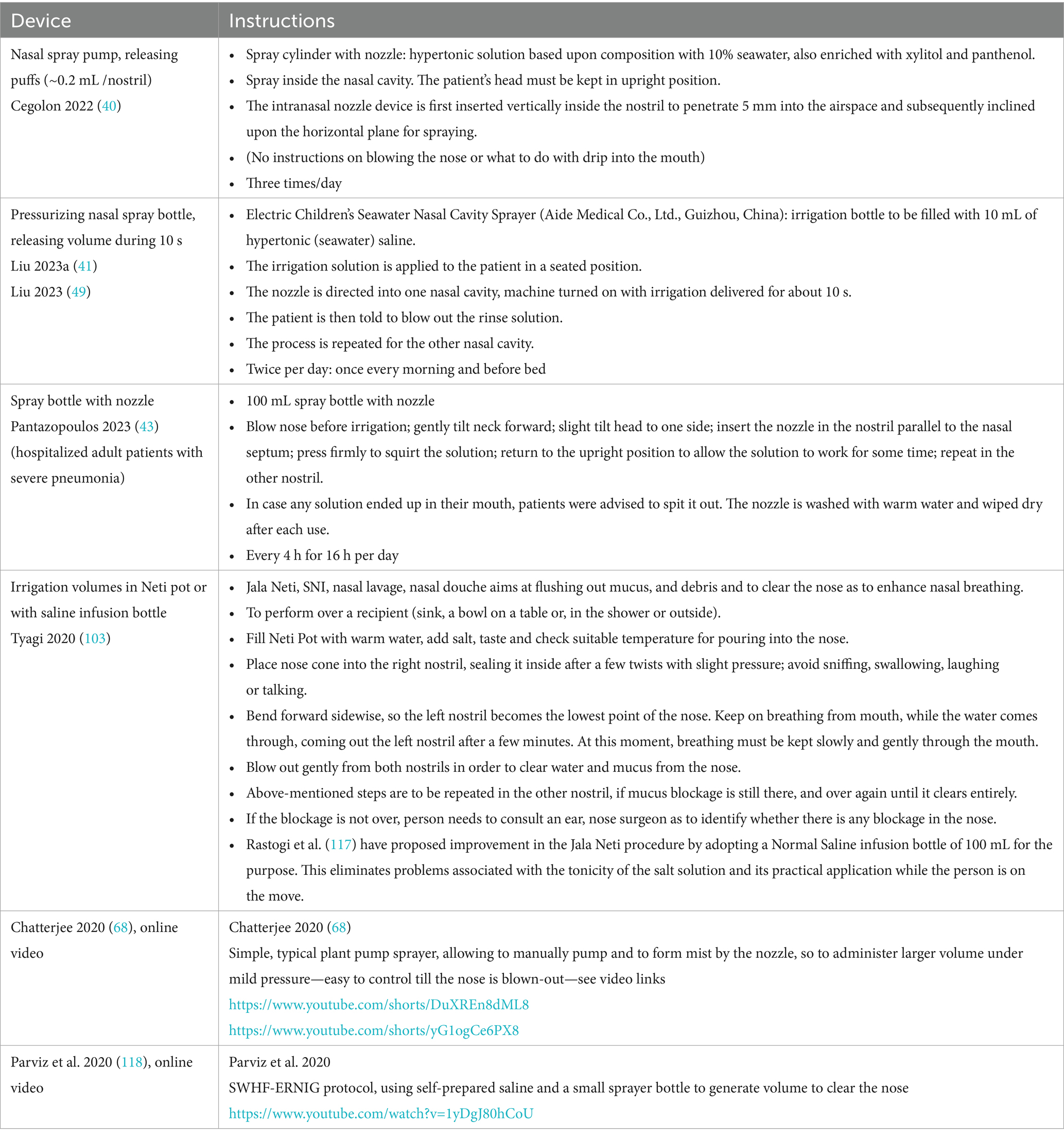

One of the practical challenges with nasal irrigation is that there are multiple ways to do it, and they're not all equally convenient. The right method depends on your lifestyle, comfort level, and how frequently you're willing to use it.

The Neti Pot Method

The traditional approach using a neti pot has been around for millennia and remains popular today. The process involves tilting your head over a sink, inserting the spout into one nostril, and letting the saline solution flow through and drain out the other nostril. Then you repeat on the other side.

Advantages: It's thorough, flushing out a substantial volume of saline, and many people find it deeply cleaning and satisfying. The higher volume means better clearing of mucus and debris. Some people genuinely enjoy the ritual aspect.

Disadvantages: It has a learning curve. Your first attempt will probably feel awkward, and there's a brief window where you might accidentally inhale saline (not dangerous, but uncomfortable). The process is messier than spray methods, requiring you to be near a sink. It's less convenient for on-the-go use, which matters if you want to use it at work or during the day.

The solution concentration and temperature matter more with neti pots. You want the solution to be at body temperature or slightly warmer. Too cold and it causes nasal irritation. Too hot and it risks damaging tissue. Room-temperature saline works but is less comfortable.

The Saline Spray Bottle Method

This is what most of the major research studies used, and it's what you'll find on pharmacy shelves everywhere. It's a small spray bottle, sometimes mechanical (requires pumping) and sometimes electronic.

Advantages: Dead simple to use. You just aim at your nostril and spray. No learning curve whatsoever. Takes about 30 seconds total. Can be used anywhere, anytime. Compact enough to carry in your pocket or bag. Extremely cheap, often under $3 for a bottle.

Disadvantages: It's less thorough than a neti pot, covering less surface area with a lower total volume of saline. The spray can sometimes feel harsh on sensitive nasal tissue if you're not careful with technique. The bottles are often single-use plastic, which isn't great for the environment.

Paul Little's study, remember, used spray bottles and still achieved the 20% reduction in cold duration. So while spray is less thorough, it's sufficient for significant benefit. Most people find spray more practical for daily use, which matters because consistency is important.

The Saline Mist Diffuser Method

Some people use small electric diffusers that create a fine mist of saline, which you then breathe in. This is less invasive than either of the above methods and might be appealing to people who find neti pots intimidating or saline spray uncomfortable.

Advantages: Very gentle. No sensation of liquid entering your nasal passages. Can be used while watching TV or working. Creates ambient saline mist that you gradually inhale.

Disadvantages: Less efficient at getting saline where you need it (directly coating the nasal passages where viruses attach). The saline disperses into the air rather than concentrating in your nasal passages. Studies specifically examining this method show modest benefits, suggesting it's less effective than direct nasal spray or neti pot irrigation.

If you're choosing a method, the research suggests: neti pot is most effective, saline spray is second, and mist diffusers are least effective. But saline spray is probably the sweet spot for most people because it's effective enough and convenient enough that you'll actually use it consistently.

Nasal saline irrigation can reduce cold duration by 20%, symptom severity by 27%, and significantly lower hospitalization likelihood by over 800% in COVID-19 patients.

Salt Concentration and Dosage: The Details Matter

One of the interesting areas still being researched is the optimal parameters for nasal saline use. Not all saline solutions are equal, and the concentration affects both effectiveness and comfort.

Isotonic saline (0.9% Na Cl) is the standard recommendation and what most studies used. It matches the salt concentration of your blood and tissues, which means it's physiologically neutral and doesn't cause irritation. You can use isotonic saline multiple times daily without discomfort. It's also the kind you'll find in most commercial saline sprays.

Hypertonic saline (1.5-3% Na Cl) is more concentrated and tends to be more effective at clearing congestion, but it's also more irritating to nasal tissue. The higher salt concentration actually draws fluid out of swollen nasal tissues, which helps with congestion. Some studies show hypertonic saline provides slightly better symptom relief, but many people find it uncomfortable if used frequently.

The general recommendation for regular daily use is isotonic. If you want to use hypertonic, reserve it for occasional deep cleansing rather than daily spray.

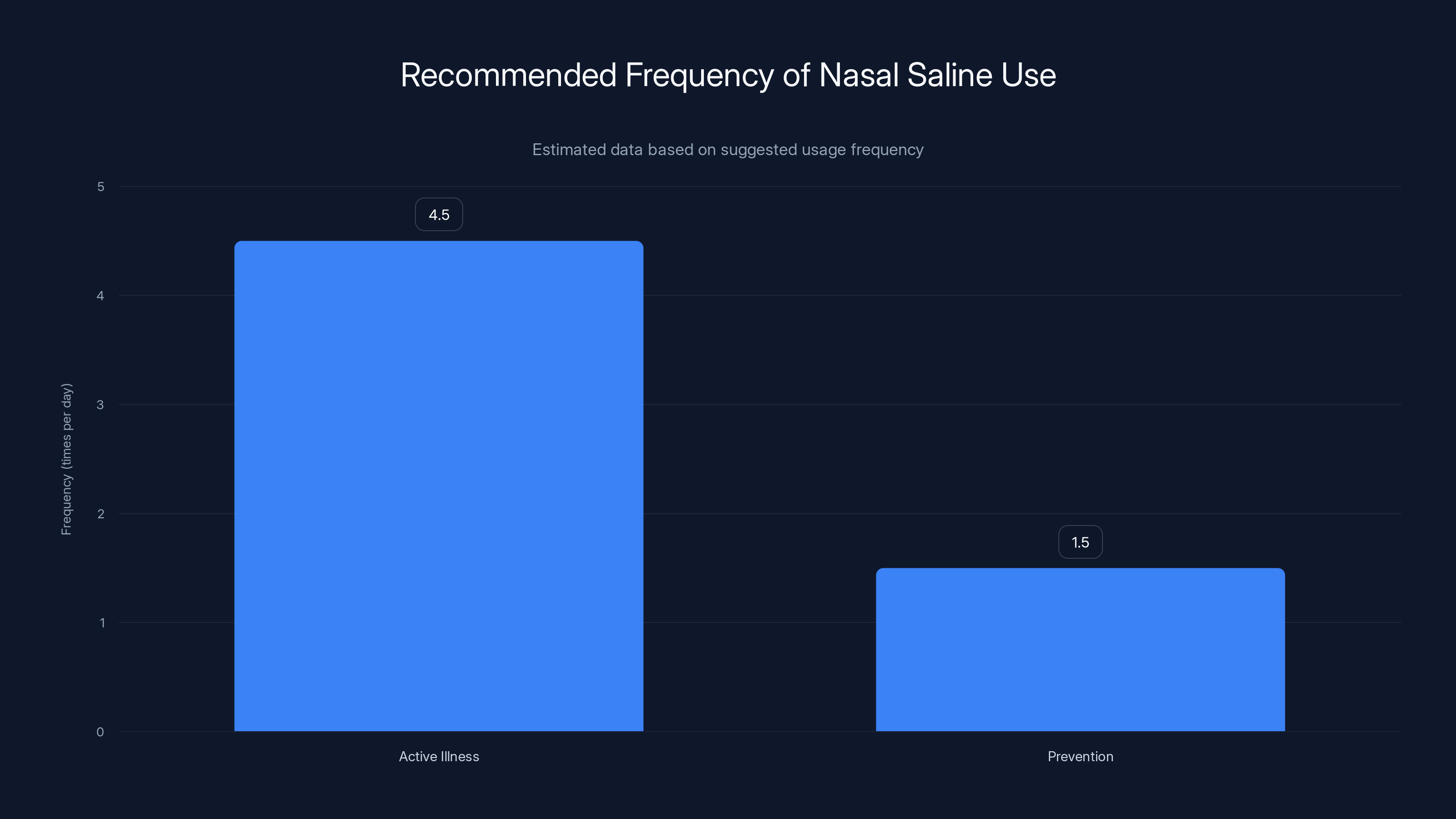

Regarding frequency, the Little study used saline three to six times daily for treatment, with the most consistent benefits appearing at the higher end of that range (five to six times daily). For prevention, the follow-up study used less frequent application, typically once to twice daily. The takeaway is that more frequent use during active illness provides more benefit.

During treatment of an active cold, three to six times daily seems optimal. That means you're applying saline roughly every three to four waking hours. Once you're past the acute phase and just dealing with residual congestion, you can reduce to two to three times daily.

Why Older Men Seem to Benefit Most

One of the interesting findings from the research is that not everyone benefits equally from nasal saline irrigation. Older men, particularly those who are overweight or obese, seem to see the biggest improvement in outcomes.

The explanation is anatomical. Older men tend to have larger nasal passages—more surface area where viruses can establish infection. When you have a bigger nasal cavity, you're essentially giving viruses more real estate to colonize. This naturally leads to higher viral load and potentially more severe infection.

If you want to use a mathematical framework to understand this: viral load increases roughly proportionally with the exposed surface area in your nasal passages. An older male with naturally larger nasal passages has maybe 30-40% more surface area than the average person. This means higher viral load for the same exposure and more virus for your immune system to fight. The relationship isn't perfectly linear because your immune system also scales somewhat with body size, but the relationship is strong.

When you apply saline to those larger nasal passages, you're coating more total area, which in absolute terms means you're delivering more hypochlorous acid precursors and more antiviral protection. You're also trapping more virus in the enhanced mucus layer across that larger surface area.

The implication is practical: if you're an older male, particularly if you're carrying extra weight, you should probably be using nasal saline irrigation during cold season as a matter of routine. The benefit is likely to be substantially larger than for other demographics.

Similarly, people with chronic congestion—whether from allergies, structural issues, or other causes—might benefit more because they're starting from a position of compromised nasal function. Saline can restore some of that function.

Nasal saline irrigation offers significant health benefits, including a 20% reduction in cold duration, 27% reduction in symptom severity, and an 8x reduction in hospitalization risk for serious respiratory infections.

Water Quality and Safety: The Critical Detail

Here's something that almost never makes it into mainstream discussions about nasal saline irrigation but is genuinely important: the water quality you use matters for safety.

In developed countries with reliable municipal water systems, this is mostly not a concern. But it's worth understanding. The risk is bacterial contamination of your homemade saline solution, which could lead to a nasal infection. Far worse, there's a microscopic parasite called Naegleria fowleri—sometimes called the "brain-eating amoeba"—that lives in warm freshwater and can cause a fatal infection if it enters your nasal passages.

Before you panic: this is extraordinarily rare, particularly in the United States and other developed countries. There are usually only 1-3 cases per year in the entire US, and most occur in people who are swimming in warm bodies of water, not from nasal irrigation. But it is a real risk in some parts of the world with less reliable water systems.

The solution is simple: use distilled water, boiled water, or sterile water specifically labeled for nasal irrigation. You can boil water and let it cool, which takes about 10 minutes total. You can buy distilled water at any grocery store for about a dollar per gallon. Neither option is inconvenient. Many commercial saline products use sterilized water, so there's no risk with those.

If you're traveling in areas with questionable water safety and want to make your own saline, boil the water first. The amoeba (and virtually all pathogens) cannot survive boiling. Let the water cool to body temperature, add salt, and you're safe.

The Evidence in Respiratory Viral Infections Beyond Colds

While most of the research focused on the common cold and COVID-19, the underlying mechanism suggests nasal saline irrigation should help against other respiratory viruses. And indeed, the limited research we have suggests this is true.

For influenza, a few smaller studies have examined whether saline can reduce duration or severity. The results are encouraging, showing roughly similar benefit to what we see with common cold—about 15-20% reduction in illness duration. Influenza is mechanically similar to rhinovirus and coronavirus in how it infects nasal tissue, so the mechanism should be similar.

For respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which particularly affects young children and elderly people, early studies suggest nasal saline irrigation might provide some protection, though the research is less robust than for colds and COVID.

The point is that the mechanism—enhancing mucosal immunity, producing antimicrobial compounds, trapping viruses in mucus—isn't unique to any single virus. As long as a virus is respiratory and primarily enters through the nasal passages, saline irrigation should provide some degree of protection.

During active illness, using nasal saline 3-6 times daily is recommended, averaging to about 4.5 times. For prevention, 1-2 times daily suffices, averaging to 1.5 times. Estimated data.

Combining Saline With Other Preventive Measures: A Layered Approach

Nasal saline irrigation is effective, but it's not a cure-all, and it's certainly not a replacement for other basic preventive measures. The most robust defense against respiratory infection comes from combining multiple strategies.

Hand hygiene remains fundamental. Respiratory viruses spread through respiratory droplets and fomites—contaminated surfaces. You touch a doorknob that someone with a cold touched, then you touch your face, and the virus gets transferred. The simple solution: wash your hands frequently, particularly after being in public spaces and before touching your face. This prevents viruses from reaching your respiratory system in the first place.

Vaccination provides protection for seasonal influenza and now for COVID-19 (and potentially other respiratory viruses in the future). Vaccination primes your immune system in advance, so if you're exposed to the virus, your body can mount a faster and more effective response. Saline irrigation works on the front lines of infection. Vaccination prepares your immune system to fight back. Together, they're more effective than either alone.

Sleep and stress management might seem unrelated, but they're critical because they affect your immune function. When you're sleep-deprived or chronically stressed, your immune system is suppressed. You're more likely to get infected and more likely to get severely infected. If you're using saline irrigation but also chronically sleep-deprived, you're working against yourself.

General hydration and nutrition matter too. Your immune system runs on nutrients. Being deficient in vitamin D, zinc, or other micronutrients compromises immune function. Staying well-hydrated supports mucus production and immune cell function. These aren't novel insights—they're straightforward physiology.

The research suggests that saline irrigation adds to these foundational measures. It's not either-or. It's another tool in your preventive toolkit.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Why This Should Be Standard Practice

Let's do some practical math here, because the cost-benefit of nasal saline irrigation is genuinely favorable.

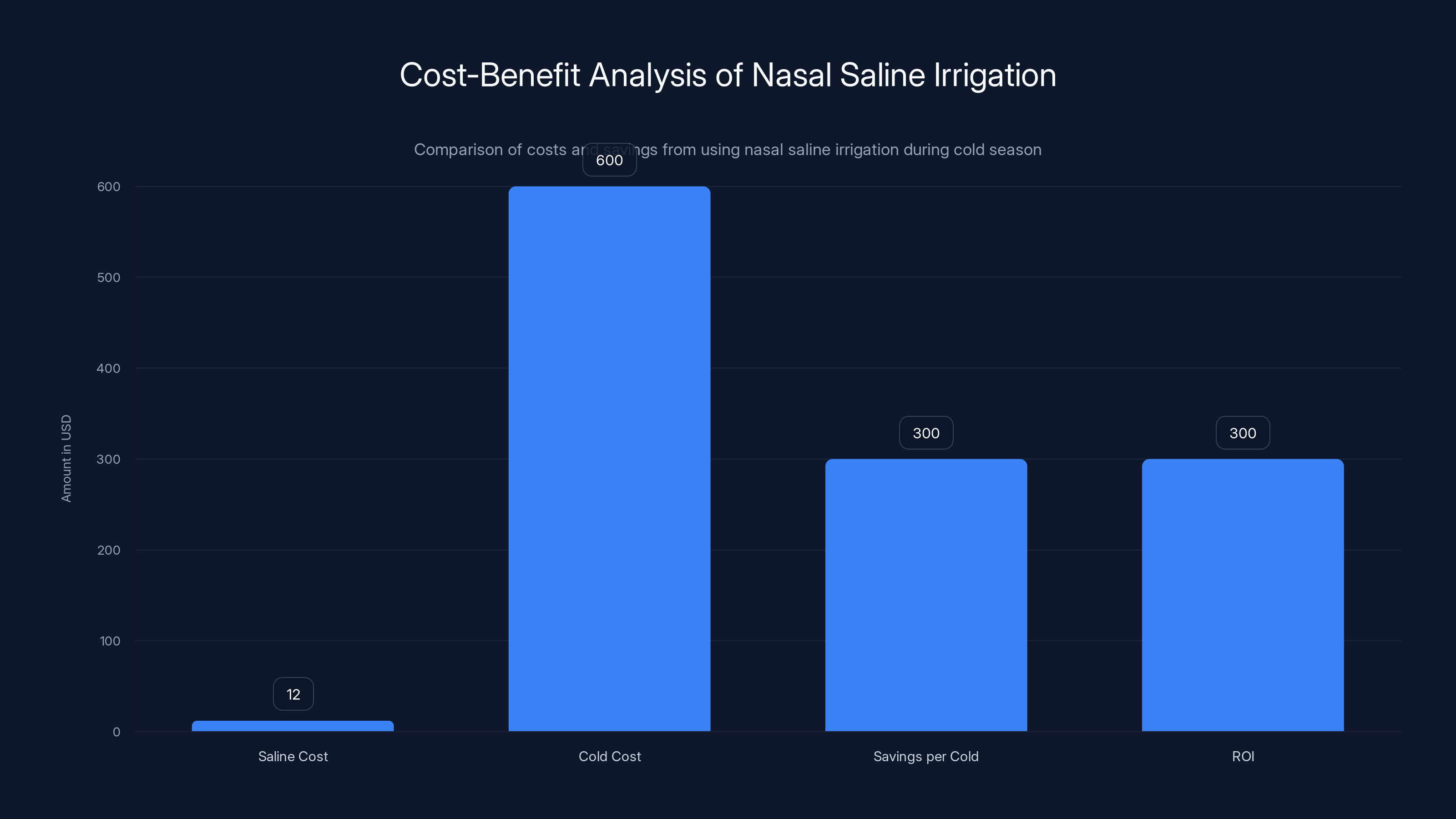

Cost of saline nasal spray:

Cost of getting a cold: This varies, but research puts it at about

Impact of 20% reduction: If saline reduces cold duration by 20%, and you'd normally have 2-3 colds per season, you're preventing one full cold every 2-3 seasons on average. That's a savings of roughly $300 per cold prevented. Even if saline only reduces severity rather than preventing infection entirely, reducing illness duration by 2-3 days per cold has real value in terms of work productivity and quality of life.

The math: You're spending

Compare this to the cost-benefit of other preventive health measures. Most people spend far more on gym memberships that they don't use consistently. Most insurance plans cost hundreds per month. Saline irrigation costs $12 and requires 90 seconds of your time per day.

There's also a massive public health argument here. If even 20% of Americans used nasal saline irrigation during cold season, the reduction in respiratory viral transmission would be measurable at the population level. Healthcare systems would save billions in hospitalization costs, antibiotic prescriptions (many of which are unnecessary and contribute to antibiotic resistance), and lost productivity.

Implementation Guide: How to Actually Start This Practice

Here's a practical guide to incorporating nasal saline irrigation into your routine:

Step 1: Choose your method. For most people, a saline nasal spray from the pharmacy is the most practical choice. Look for products with 0.9% sodium chloride and no additives. Brands are less important than the saline concentration. The generic versions are chemically identical to brand-name products and cost less.

Step 2: Get the timing right. Start using saline at the very first sign of a cold—that initial throat tickle, the very first sniffle, the moment you feel something coming on. The earlier you start, the more effective it is. If you wait until you're already congested, it still helps, but less so.

Step 3: Use the correct frequency during active illness. Three to six times daily is the studied protocol. That's roughly every 3-4 waking hours. Morning, midday, afternoon, and evening covers it. It's not burdensome—you're spending maybe 30 seconds per application.

Step 4: For prevention, use lower frequency. If you're not currently sick but want to reduce your risk during cold season, one to two times daily is sufficient. Morning and evening is reasonable.

Step 5: Proper technique matters. Tilt your head back slightly, insert the spray tip into one nostril, spray, then repeat with the other nostril. Don't sniff hard afterward—just let it coat your nasal passages. Some people prefer to spray while bent over a sink in case of drips, but it's not necessary.

Step 6: Stay consistent. The benefits accumulate with consistent use. One spray every few days won't provide much benefit. Regular use does.

Potential Side Effects and Contraindications

The good news: nasal saline irrigation is remarkably safe. In the massive 14,000-person study, there were essentially no adverse events reported. No hospitalizations. No serious complications. No unexpected interactions.

Minor side effects are possible and mostly relate to technique or personal sensitivity rather than saline itself. Some people report mild nasal irritation, though this is usually temporary and often resolves within a few uses. If you're using hypertonic saline (more concentrated), irritation is more common.

Some people experience brief nasal stinging when they first use saline, particularly if they have active inflammation from an existing cold. This usually passes quickly and indicates the saline is reaching inflamed tissue, which is actually where you want it.

Very rarely, people report getting fluid in their ears if they use saline in a neti pot with overly aggressive technique. This is usually temporary and completely harmless, but it's uncomfortable. Gentler application prevents this.

The main contraindication is untreated nasal surgery recovery. If you've had nasal surgery in the past 1-2 weeks, check with your doctor before starting irrigation.

There's a theoretical concern about overusing saline and somehow disrupting normal nasal flora, but the research doesn't support this being a real issue. Your nasal microbiome is resilient, and saline irrigation doesn't cause dysbiosis the way antibiotics can.

There's also a theoretical concern that saline might impair mucociliary clearance (the body's ability to move mucus), but again, the research doesn't show this in practice. Well-hydrated nasal tissue actually has better mucociliary clearance than dry tissue.

The Future: Where Nasal Saline Research Is Heading

The field is actively investigating several new directions. Some researchers are exploring whether adding active compounds to saline—like lysozyme (an antimicrobial enzyme) or specific phage-derived peptides—could enhance effectiveness. These modified formulations would combine the mechanical benefit of saline irrigation with additional antimicrobial activity.

Other researchers are investigating whether nasal saline could be effective as a preventive measure for healthcare workers or others with high exposure risk. If you're a nurse on a COVID ward or a teacher managing 30 kids, can regular nasal saline irrigation substantially reduce your infection risk?

There's also interest in whether nasal saline could help with long COVID symptoms—the persistent issues that some people develop after acute COVID infection. While the research here is still preliminary, the mechanism (enhancing mucosal immunity and clearing viral particles) could theoretically help.

Finally, there's practical research into product delivery systems. If you could combine saline irrigation with a pleasant aroma or flavor, would that improve compliance? If you used an electronic diffuser instead of manual spray, would that be more acceptable to elderly people? These quality-of-life improvements might seem minor, but they directly affect whether people use the treatment consistently.

The point is that researchers now take nasal saline irrigation seriously. It went from being a dismissed alternative therapy to being funded by major health research institutions and published in prestigious journals. That shift in credibility matters.

FAQ

What exactly is nasal saline irrigation?

Nasal saline irrigation is the practice of flushing your nasal passages with a salt-water solution (saline) to help clear congestion, reduce virus load, and support immune function. It can be done using a neti pot, nasal spray bottle, or electronic diffuser, and involves using an isotonic saline solution (typically 0.9% sodium chloride) mixed with distilled or boiled water.

How does nasal saline irrigation work to prevent or reduce colds?

When saline enters your nasal passages, your nasal cells convert the chloride ions into hypochlorous acid, which directly inhibits viral replication. Additionally, saline hydrates your nasal tissue, enhancing mucus production that traps viruses, increasing the activity of white blood cells called neutrophils that fight infection, and making viral attachment to nasal cells more difficult by keeping receptors in a hydrated, moving state rather than stiff and stationary.

What are the clinical benefits of nasal saline irrigation according to research?

A major 2024 study of nearly 14,000 participants funded by the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Research found that saline nasal spray used three to six times daily at the first sign of infection reduced cold duration by approximately 20% and reduced symptom severity by 27%. A separate study of COVID-19 patients found that those who performed saline nasal irrigation twice daily for two weeks after testing positive were more than 8 times less likely to require hospitalization compared to a control group.

Is homemade saline solution safe, and how do I make it?

Homemade saline is safe if you use proper water. Mix half a teaspoon of salt with 8 ounces of distilled, boiled, or otherwise sterilized water to create an isotonic saline solution. Never use untreated tap water, as it could contain bacteria or parasites. The cost of homemade saline is minimal—less than one cent per batch—but commercial saline sprays are inexpensive enough that the convenience factor often justifies the small cost difference.

How often should I use nasal saline irrigation?

For treatment of an active cold or respiratory infection, use saline three to six times daily, starting at the very first sign of symptoms. For prevention during cold season when you're not currently sick, one to two times daily is sufficient. Consistent use provides better results than occasional use, so finding a method you'll actually use regularly is more important than finding the "perfect" frequency.

Are there any side effects or safety concerns with nasal saline irrigation?

Nasal saline irrigation is remarkably safe with very few side effects reported in large clinical trials. Some people may experience minor nasal irritation or stinging, particularly with hypertonic (more concentrated) saline solutions, but these effects are usually temporary. The main safety consideration is using proper water (distilled, boiled, or sterile) rather than untreated tap water to avoid rare bacterial or parasitic contamination. Consult with a doctor if you've had recent nasal surgery before starting irrigation.

Why did it take so long for Western medicine to accept nasal saline irrigation?

Nasal saline irrigation originated in Ayurvedic medicine over 5,000 years ago and was examined by Western doctors in the 19th century but was largely abandoned in the 20th century. Traditional medicine practices were often dismissed without rigorous investigation. The COVID-19 pandemic prompted researchers to reconsider many overlooked interventions, and the subsequent research demonstrating saline's effectiveness led to broader acceptance. Early in the pandemic, the WHO even listed saline irrigation on its "myth buster" page before removing it as evidence accumulated.

What's the difference between isotonic and hypertonic saline?

Isotonic saline contains 0.9% sodium chloride and matches the salt concentration of human tissue, making it gentle for frequent daily use without irritation. Hypertonic saline contains 1.5-3% sodium chloride, is more concentrated, and draws fluid out of swollen nasal tissues to provide better congestion relief, but it's more irritating and should be used less frequently. For regular daily use, isotonic saline is typically recommended; hypertonic is reserved for occasional deep cleansing.

Which age groups or populations benefit most from nasal saline irrigation?

While nasal saline irrigation benefits most people, research indicates that older men—particularly those who are overweight—see the largest improvements. This is because they have larger nasal passages (more surface area), which allows for higher viral load from the same exposure. Using saline on larger nasal passages provides more absolute protection. People with chronic congestion from allergies or structural issues also benefit substantially.

Can nasal saline irrigation help with viruses other than the common cold and COVID-19?

While most detailed research focuses on cold and COVID, the underlying mechanism of saline (enhancing mucosal immunity, producing antimicrobial compounds, trapping viruses) applies to other respiratory viruses. Limited studies suggest saline provides similar benefits (15-20% reduction in illness duration) for influenza and possible benefits for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), though research is less robust than for colds and COVID.

Conclusion: Why Ancient Wisdom and Modern Science Align on This One

What started as a 5,000-year-old health practice born from Ayurvedic medicine has evolved into one of the most evidence-backed preventive interventions available. That journey from dismissal to validation tells us something important about both traditional wisdom and scientific rigor. Some ancient practices work. Others don't. The only way to know is to test them carefully, which is exactly what happened with nasal saline irrigation.

The evidence is now substantial enough that every person should probably be using saline irrigation during cold season. Not maybe. Probably. The cost is trivial—under $15 per season. The time commitment is minimal—less than two minutes per day. The safety profile is essentially perfect. The benefits are meaningful and measured: 20% reduction in cold duration, 27% reduction in symptom severity, and 8x reduction in hospitalization risk for serious respiratory infections.

When you step back and look at the return on investment, it's hard to argue with the math. You're spending the cost of two fancy coffee drinks per winter season to potentially avoid being sick for multiple days. From a pure productivity and quality-of-life perspective, that's one of the best health bargains available.

The fascinating part is understanding why it works. It's not magic. It's not superstition. It's solid biochemistry. Your nasal cells have the ability to produce antimicrobial compounds. Saline provides the substrate for that production. Your immune cells are more effective when they have proper working conditions. Saline creates those conditions. Your mucus becomes a better trap for viruses when it's properly hydrated. Saline provides that hydration. Every benefit has a molecular explanation.

That's what convinced skeptical researchers. It's not that saline is some mysterious miracle cure. It's that once you understand the mechanisms—how it triggers hypochlorous acid production, how it enhances neutrophil activity, how it optimizes the physical trapping of viruses—the effectiveness makes complete sense.

The implication is profound. For most of human history, people couldn't understand why saline irrigation worked. They just observed that it did, and they kept doing it. Now we can explain the mechanism in detail. That doesn't change the fact that it works, but it does change how we think about it. This isn't an outlier. This isn't a fluke. This is a straightforward application of human physiology that we finally have the tools to measure and prove.

So here's the practical recommendation: during cold season, keep a saline spray bottle accessible. Use it once or twice daily as a preventive measure. If you start feeling the first sign of a cold, increase to three to six times daily for the duration of the illness. It's not complicated. It's not expensive. It's not a pharmaceutical intervention that requires navigating healthcare systems. It's just saltwater and basic preventive medicine.

Your immune system will thank you. Your wallet will thank you. And you'll probably spend fewer days this winter feeling miserable, which is really the whole point.

The ancient practice wasn't abandoned because it didn't work. It was abandoned because we forgot about it, got distracted by newer approaches, and somehow lost track of the fact that sometimes the simplest solutions are the best ones. Now that we've rediscovered it and proven it works, there's no good reason to ignore it. Your nose has been waiting thousands of years for modern science to catch up. You might as well take advantage of that now.

Key Takeaways

- Nasal saline irrigation, a 5,000-year-old Ayurvedic practice, has been validated by modern science to reduce cold duration by approximately 20% and hospitalization risk by 8x in COVID cases

- The mechanism works at the cellular level: saline triggers production of hypochlorous acid in nasal cells, which directly inhibits viral replication while enhancing immune function

- Cost-benefit analysis shows approximately 25:1 return on investment, spending 300+ per prevented or reduced cold

- Older men with larger nasal passages see the greatest benefits, as they have more surface area for viral colonization and thus benefit more from saline's protective coating

- Starting saline spray at the very first sign of infection (within 24 hours) is critical; using 3-6 times daily during active illness provides optimal results

![Nasal Saline Rinse for Cold Prevention: Ancient Ayurvedic Remedy Proven by Modern Science [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasal-saline-rinse-for-cold-prevention-ancient-ayurvedic-rem/image-1-1767803868310.jpg)