Super Flu (H3N2 Subclade K): Everything You Need to Know About the Outbreak [2025]

Sometime around late August 2025, public health officials started noticing something unusual. Hospital emergency departments in the United States and United Kingdom were filling up faster than normal for flu season. Respiratory illnesses were spiking earlier than they typically do. Media outlets began using the term "super flu" to describe what was happening. But here's the thing: that's not actually the technical name, and the reality is more nuanced than the sensational headlines suggest.

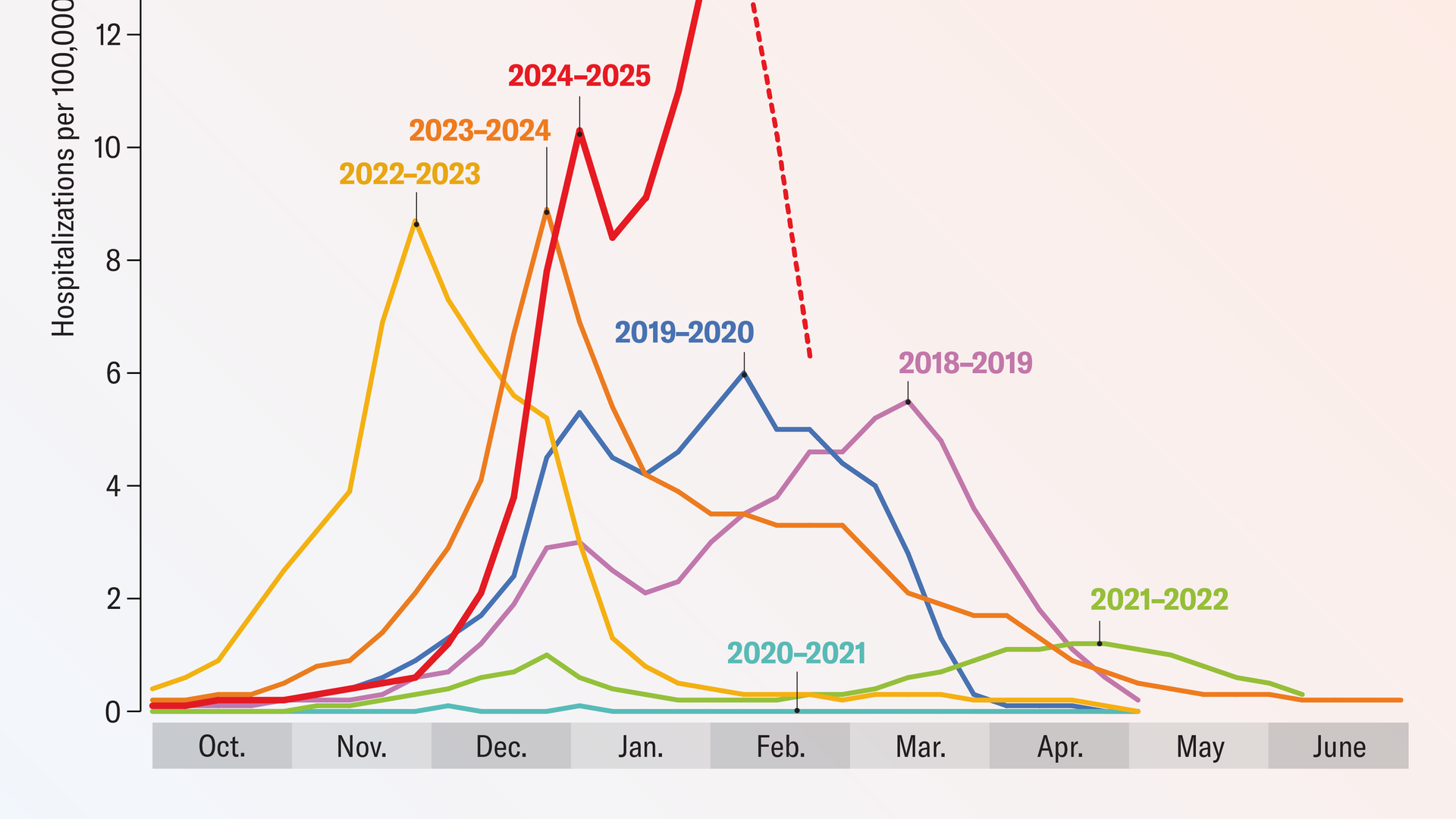

The virus making headlines isn't some entirely new pathogen. It's a new variant of influenza A H3N2 called subclade K, and it's been generating concern among epidemiologists precisely because of how effectively it's spreading, combined with how well it evades existing vaccine immunity. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officially designated the 2024-25 flu season as the most severe since 2017-18. In the United Kingdom, flu cases began circulating earlier than at any point since 2003-04.

But before you panic, understand this: the virus isn't inherently more deadly than conventional H3N2. What makes it noteworthy is its ability to slip past immune defenses that previously protected people. That's the actual story worth understanding. This article breaks down what subclade K really is, why it's spreading so aggressively, whether existing vaccines work, and what you actually need to do to protect yourself and your family.

TL; DR

- Subclade K is a new H3N2 variant: Multiple mutations in the hemagglutinin protein allow it to partially evade vaccine and infection immunity

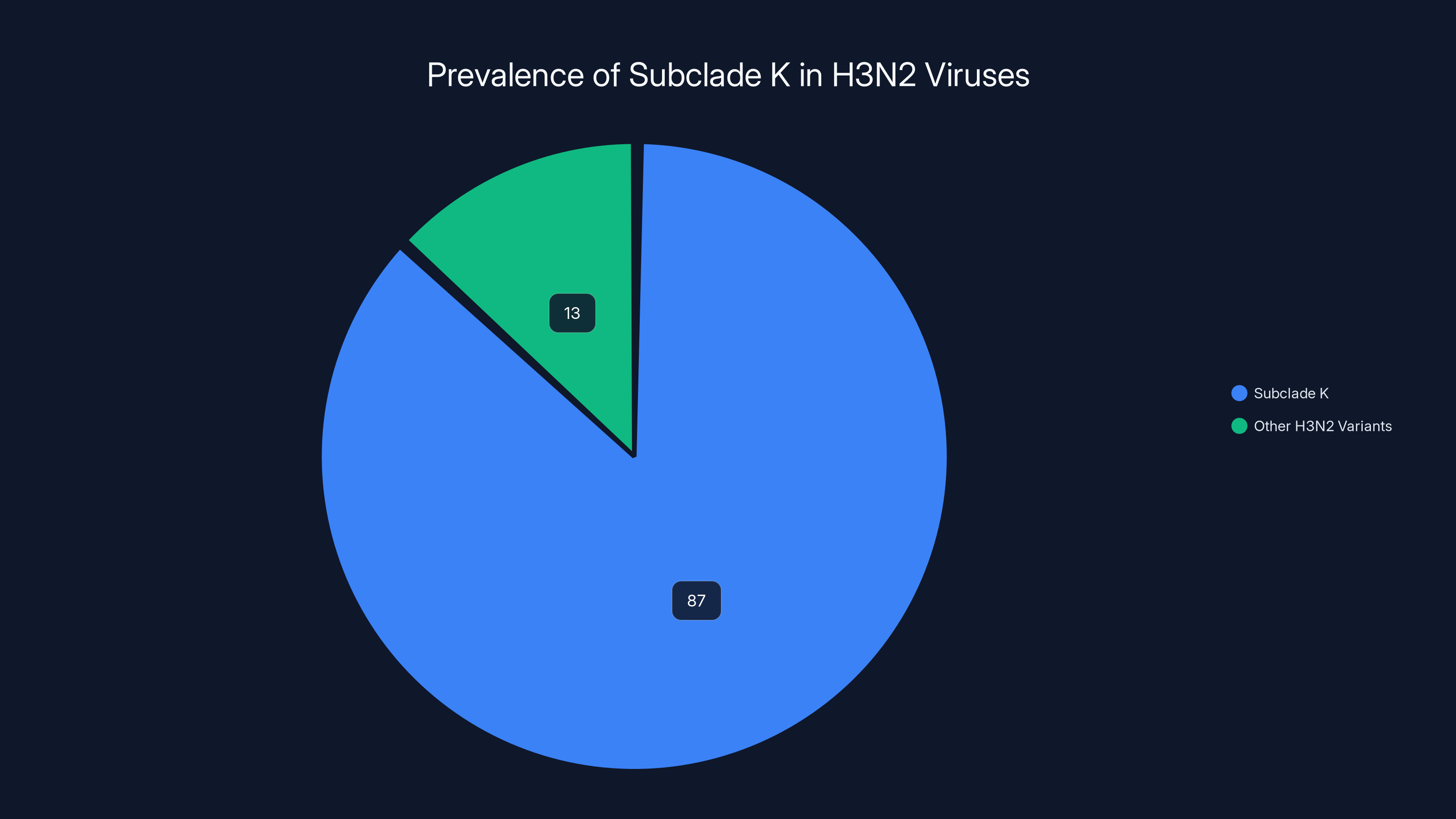

- It's spreading earlier and faster: The 2024-25 flu season is the most severe since 2017-18, with 87% of detected H3N2 viruses being subclade K

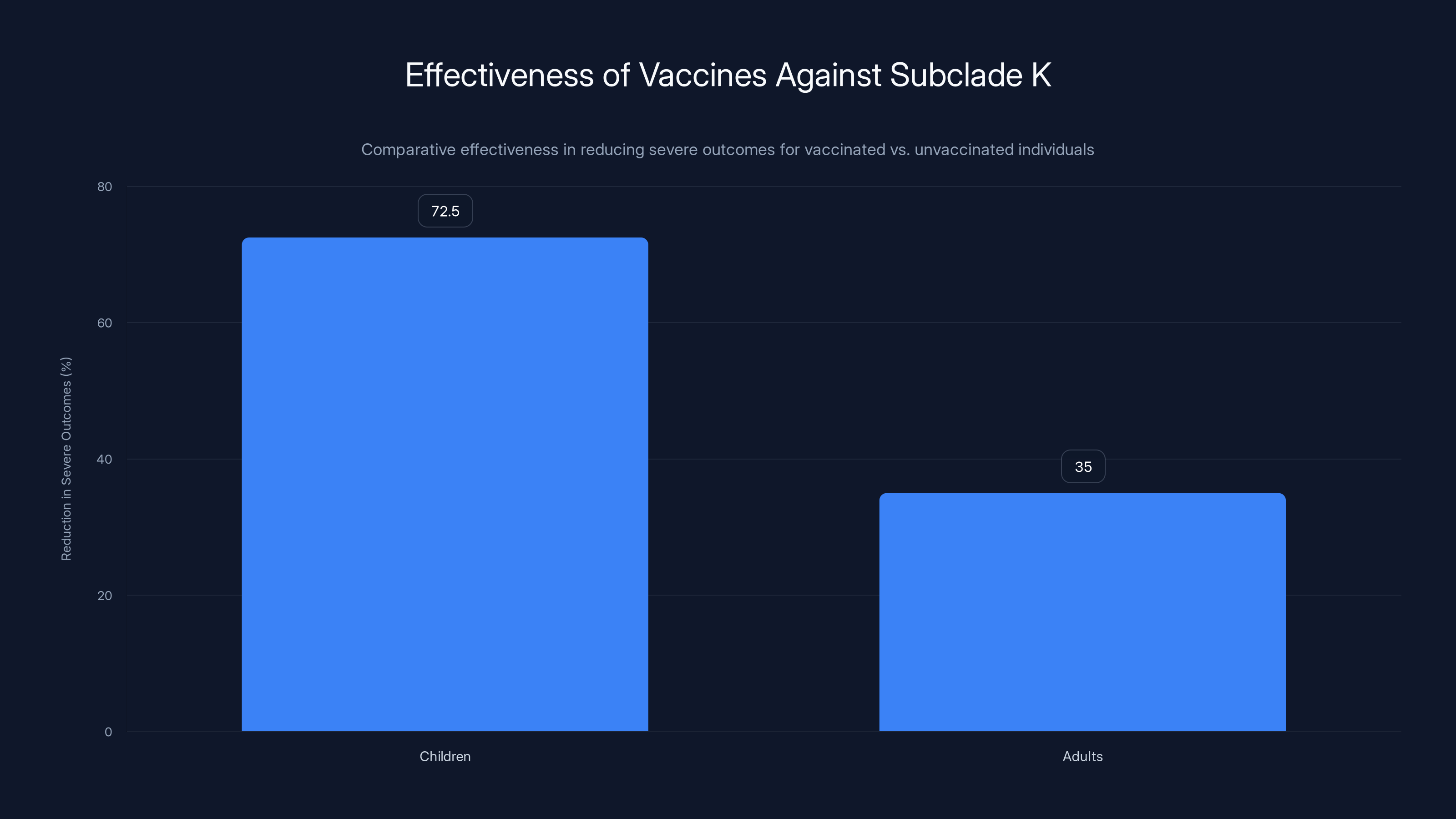

- Vaccines still provide protection: They're 70-75% effective at preventing hospitalizations in children and 30-40% effective in adults

- Prevention remains standard: Vaccination, hand hygiene, masks in crowds, and staying home when sick are your best defenses

- Bottom line: This is a serious flu season, not a "super" threat—respond with science-based caution, not fear

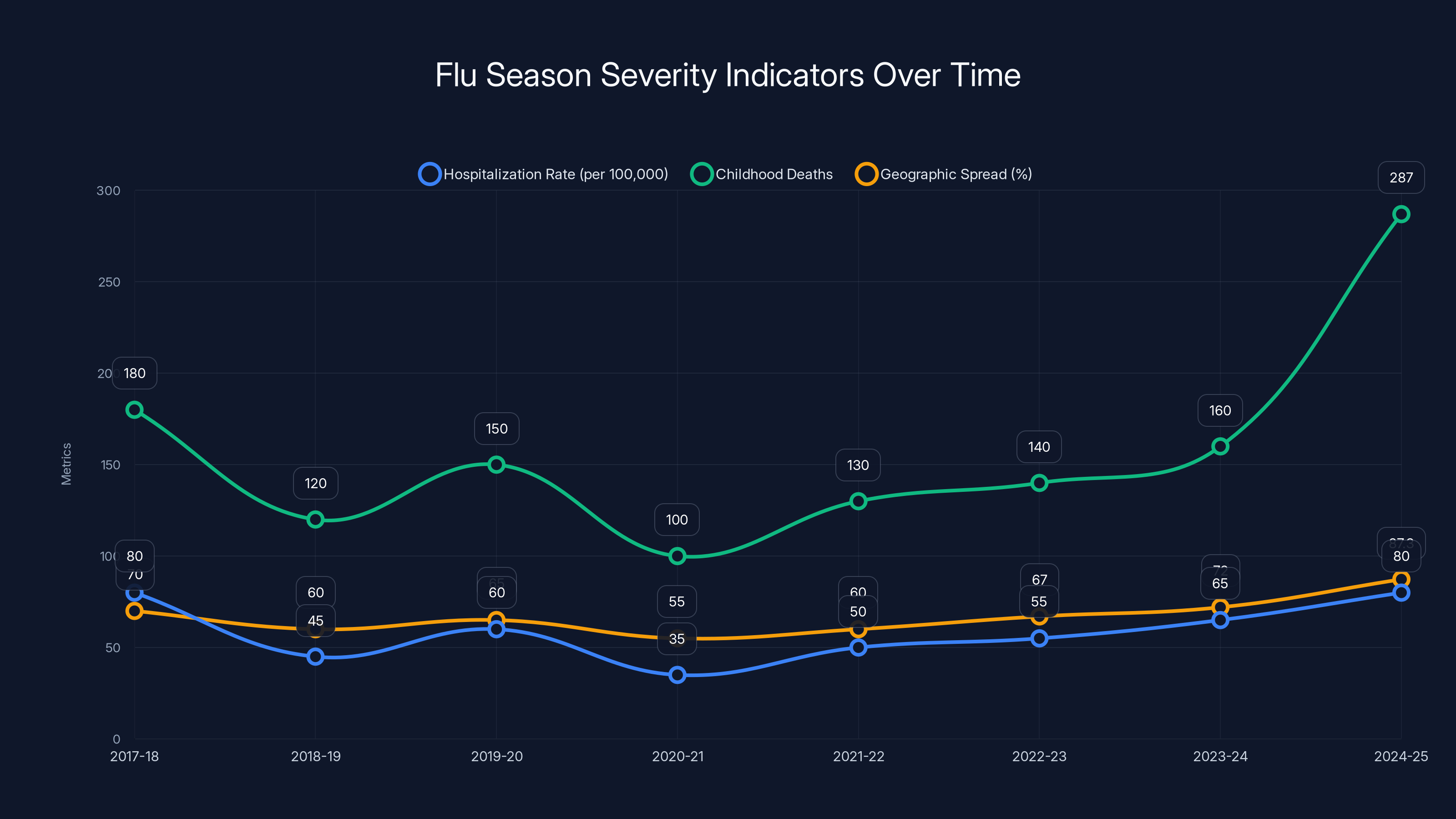

The 2024-25 flu season saw hospitalization rates and geographic spread comparable to the severe 2017-18 season, with childhood deaths reaching the higher end of the typical range.

What Exactly Is Subclade K? Understanding the Virus Behind the Headlines

The term "super flu" sounds dramatic, and that's exactly why media outlets use it. But it's not an official medical designation. Virologists and epidemiologists refer to this virus as subclade K, which is a specific genetic variant of influenza A H3N2.

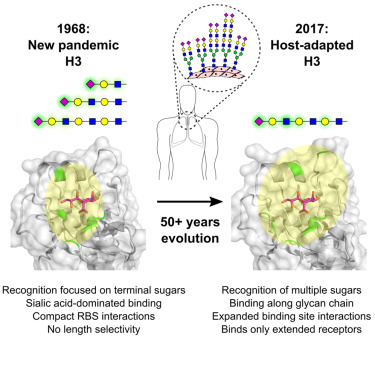

To understand what makes subclade K different, you need to understand how flu viruses work. The surface of an influenza virus is studded with proteins called hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. These proteins are what your immune system recognizes and attacks. They're also what the virus uses to infect cells in your respiratory tract. Vaccine developers use information about the current circulating strains to predict which variants will dominate in the upcoming season and design vaccines accordingly.

Subclade K has undergone multiple mutations in its hemagglutinin protein compared to the strains used to formulate the current season's vaccines. These changes make it antigenically different. In practical terms, this means the virus looks sufficiently different to your immune system that antibodies from previous flu shots or prior infections don't recognize it as effectively as they would recognize earlier variants.

This is called immune escape, and it's the primary reason subclade K has been able to spread so widely. Your body's immune defenders are essentially working from an outdated photo of the suspect. Genetic analysis conducted by the UK Health Security Agency found that 87% of H3N2 viruses detected since late August 2025 were subclade K. This rapid replacement of older variants suggests a significant selective advantage.

It's worth emphasizing: subclade K isn't a new influenza virus type. It's not jumping between species like avian flu does. It's not fundamentally more deadly than previous H3N2 variants. What makes it noteworthy in epidemiological circles is precisely this ability to partially evade population immunity through accumulated mutations. The virus is following the script that influenza viruses have followed for decades.

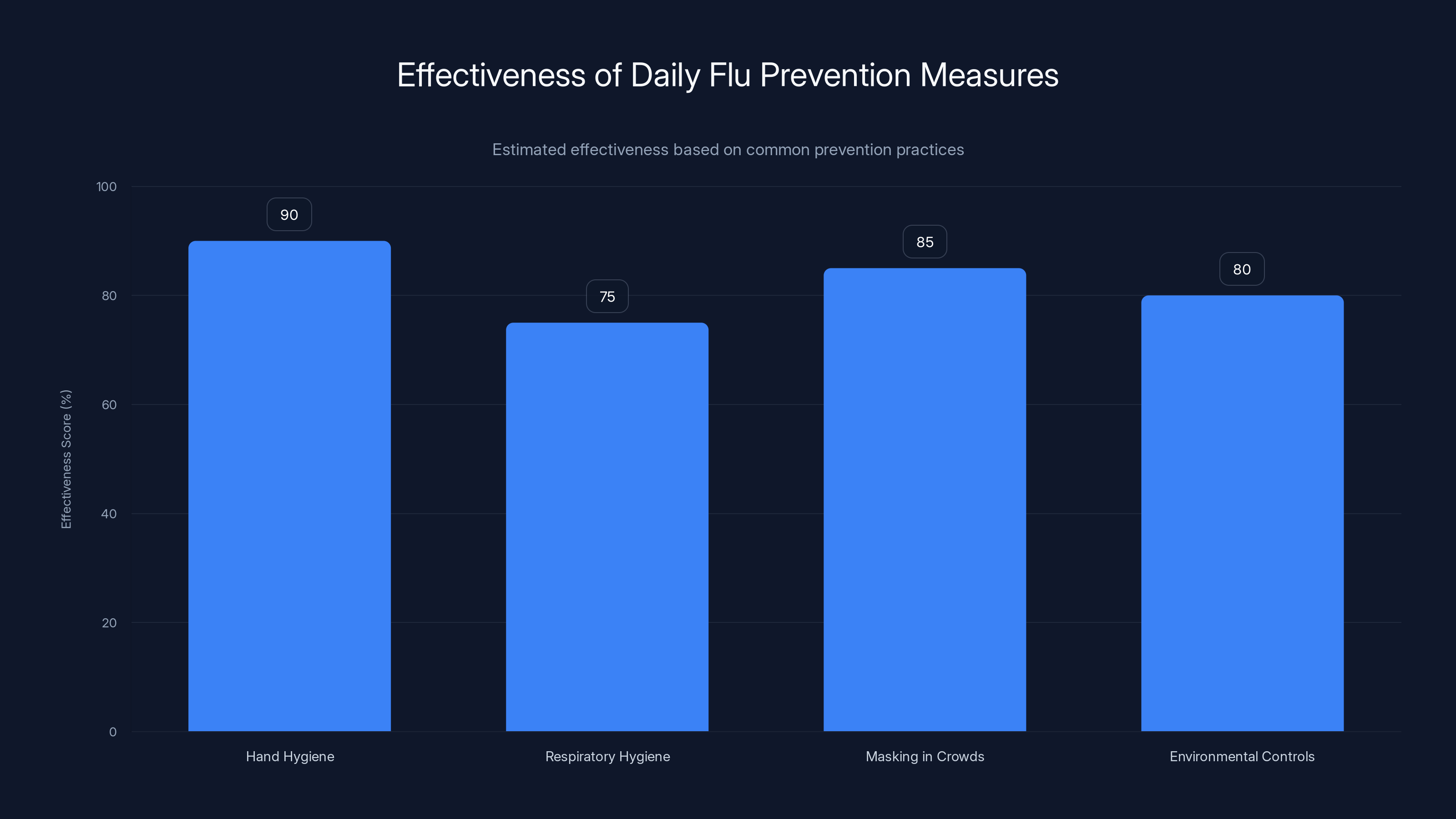

Hand hygiene is the most effective daily prevention measure against flu, with an estimated effectiveness score of 90%. Estimated data based on typical prevention practices.

Why Did This Outbreak Start Earlier Than Usual?

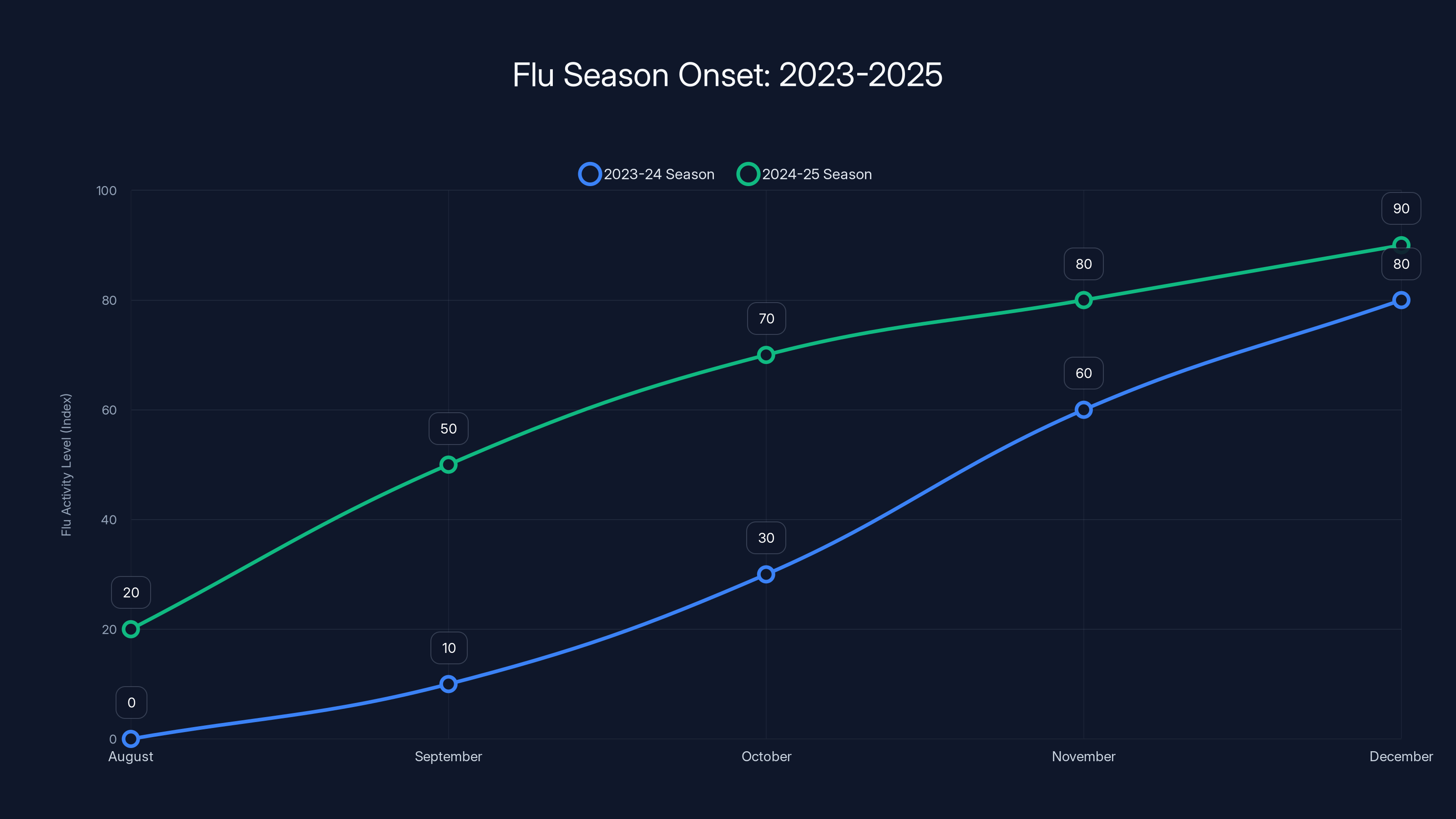

One of the most striking aspects of the 2024-25 flu season is its timing. The flu doesn't arrive on a predictable schedule, but patterns do emerge over decades. In most years, flu activity in the Northern Hemisphere begins ramping up in November and peaks in January or February. In 2025, flu activity reached significant levels by early September. In the United Kingdom, cases began appearing in August, earlier than any documented year since 2003-04.

Multiple factors converged to create these unusual conditions. Public health experts point to several key causes. First, during the three-year period of the COVID-19 pandemic, influenza transmission was heavily suppressed by lockdowns, mask-wearing, social distancing, and remote work. For millions of people, the 2020-2023 period meant little to no exposure to circulating flu viruses. This created a population with lower baseline immunity.

When social restrictions eased and life returned to normal, there was a large cohort of people—particularly children born during or after the pandemic—who had minimal prior flu exposure. Their immune systems had no "memory" of previous flu encounters. From the virus's perspective, this represented an enormous opportunity for transmission. This phenomenon is sometimes called immunity gap.

Second, there's evidence that COVID-19 itself may have caused some lasting effects on immune function in infected individuals. Research has documented instances where COVID-19 infections appear to temporarily suppress certain immune responses, potentially making people more susceptible to secondary infections including influenza.

Third, 2025 brought record-breaking heat waves to multiple regions. In Japan, where health ministry data provided detailed early tracking, temperatures shattered historical records. Heat stress reduces overall immune function and increases susceptibility to infection. When combined with lower baseline population immunity, the result is accelerated transmission.

Fourth, the emergence and rapid spread of subclade K itself amplified transmission. When a new variant escapes existing immunity more effectively, it spreads faster than older variants would have. This accelerated spread then creates more opportunities for further mutations. It's a feedback loop that seasonal flu creates every year, but the scale varies depending on how different the new variants are from what the population has encountered before.

The Severity Picture: Numbers That Matter

When public health officials label something "the most severe season since 2017-18," they're basing that on specific metrics. Understanding these numbers helps separate actual risk from media sensationalism.

The CDC tracks multiple indicators throughout the flu season. These include the percentage of clinical specimens that test positive for influenza, the number of respiratory illnesses reported, hospitalization rates, and mortality data. For the 2024-25 season, hospitalizations reached levels comparable to the 2017-18 season, which was notably severe.

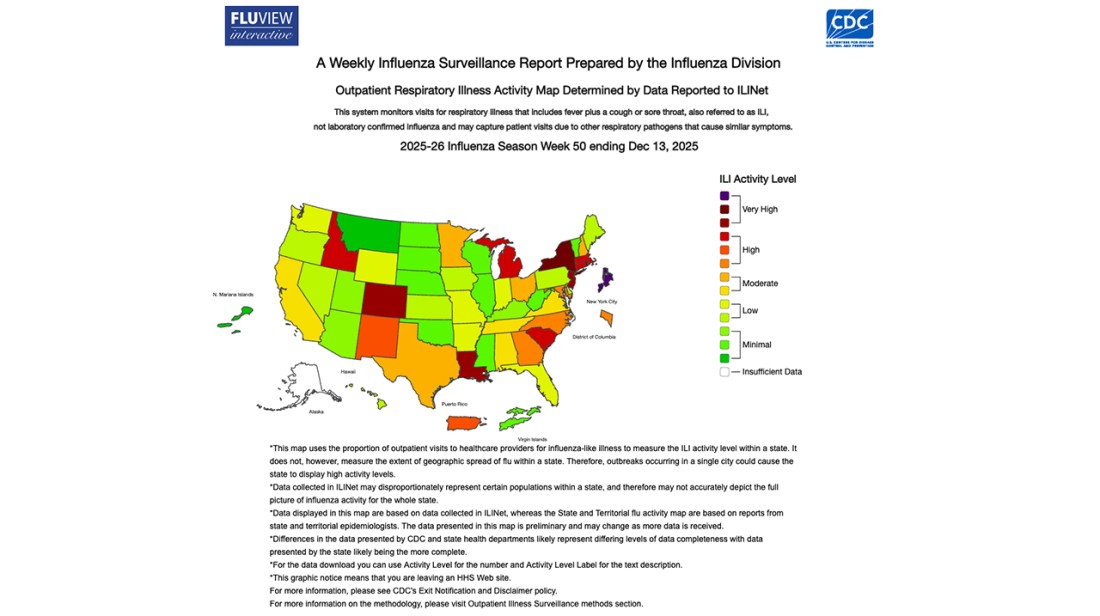

In the United States, by early 2025, active epidemics were occurring in 87.3% of the country simultaneously. That's extraordinarily high—in many years, flu remains geographically spotty, hitting certain regions hard while others escape relatively unscathed. For 11 consecutive weeks, more than 50% of the country reported high epidemic levels. This consistency across geography and time is what makes the season notable.

Childhood deaths reached 287 by the season's peak, a significant number that understandably alarmed parents and public health officials. This figure, however, requires context. While tragic, seasonal influenza routinely kills children in the United States—the number typically ranges from 100 to 600 per season depending on how severe that year's strains are. The 2024-25 number falls within the historically expected range, though toward the higher end.

The key point here: high severity numbers reflect the scale of the epidemic (more people infected), not necessarily an increase in the lethality of the virus itself. When twice as many people get infected compared to an average season, you expect roughly twice as many hospitalizations and deaths, even if the virus is no more dangerous to each individual.

In Australia, which enters flu season earlier than the Northern Hemisphere, the 2025 season was the highest recorded in 19 years of tracking. This global pattern strongly suggested that the Northern Hemisphere would face a similarly severe season—which is exactly what happened.

Subclade K accounts for 87% of H3N2 viruses detected since August 2025, indicating a significant selective advantage.

How Effective Are Current Vaccines Against Subclade K?

This is the question people ask first: Did you get the vaccine? Does it still work? The honest answer is: yes, but less completely than we'd like.

Vaccine formulation decisions happen months in advance. Scientists examine which flu strains are circulating globally, predict which ones will dominate in the upcoming season, and work with manufacturers to produce vaccines based on those predictions. The 2024-25 vaccines were formulated based on virus data from early 2024. Subclade K emerged and began spreading later in the year, meaning the vaccines weren't specifically designed to target its unique mutations.

When researchers conducted real-world studies comparing illness outcomes between vaccinated and unvaccinated people in the UK, they found that vaccination provided significant protection against severe outcomes. In children who were vaccinated, the risk of emergency room visits or hospitalization after infection was reduced by 70-75% compared to unvaccinated children who got infected. For adults, the protection was more modest at 30-40% reduction in severe outcomes.

These numbers sound lower than ideal, but context matters. Even a 30% reduction in hospitalization risk in a severe season prevents thousands of people from needing hospital care. A 70% reduction in children is substantial protection. Most importantly, these figures show that even though subclade K evades vaccine immunity partially, vaccinated people still have some protection against the worst outcomes.

Some vaccinated people still got infected and experienced illness. This is expected—vaccines reduce risk, they don't eliminate it completely. Think of a vaccine like a better immune training program. Vaccinated people's immune systems recognize the virus faster and mount a stronger response, reducing the duration and severity of illness.

The mechanism is this: when you're vaccinated, your body produces antibodies (proteins that directly attack the virus) and develops memory B cells and T cells that can rapidly reactivate if you encounter the virus later. If you get infected despite being vaccinated, these primed immune cells spring into action faster than they would in an unvaccinated person. The viral load doesn't grow as high before your immune system gains control. Fewer cells get infected. Less damage occurs to respiratory tissues. You're less likely to develop pneumonia or need supplemental oxygen.

Symptoms of Subclade K Influenza: What to Watch For

Here's what nobody tells you about the flu: there's nothing visually distinctive about subclade K compared to any other H3N2 variant. You can't look at a sick person and identify which flu strain they have. The symptoms are, in a word, the same as regular flu.

Characteristic flu symptoms typically appear one to four days after viral exposure. The illness usually starts abruptly—this is a key distinction from the common cold, which develops gradually. Most people with influenza experience fever (often in the 101-103°F range), body aches, fatigue, cough, and sore throat. Children sometimes experience nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, though respiratory symptoms are most common.

The cough in influenza tends to be persistent and somewhat dry at first, though it may become productive (producing mucus) later in the illness. Fatigue can be profound—people describe it as exhaustion that makes simple activities feel overwhelming. This fatigue commonly persists for weeks even after fever and cough resolve, a phenomenon sometimes called post-viral fatigue.

What distinguishes flu from the common cold is the speed of onset and the prominence of systemic symptoms. A common cold usually causes primarily nasal and throat symptoms and develops gradually. The flu causes whole-body symptoms and arrives suddenly.

Most people recover within 5-7 days for fever and cough, though some symptoms linger for 2-3 weeks. However, some people develop complications. Pneumonia—either primary viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia—is the most serious complication. Older adults, very young children, pregnant women, and people with chronic medical conditions face higher risk.

Warning signs that warrant immediate medical attention include difficulty breathing, chest pain, confusion, persistent high fever, and severe weakness. These suggest possible pneumonia or other serious complications.

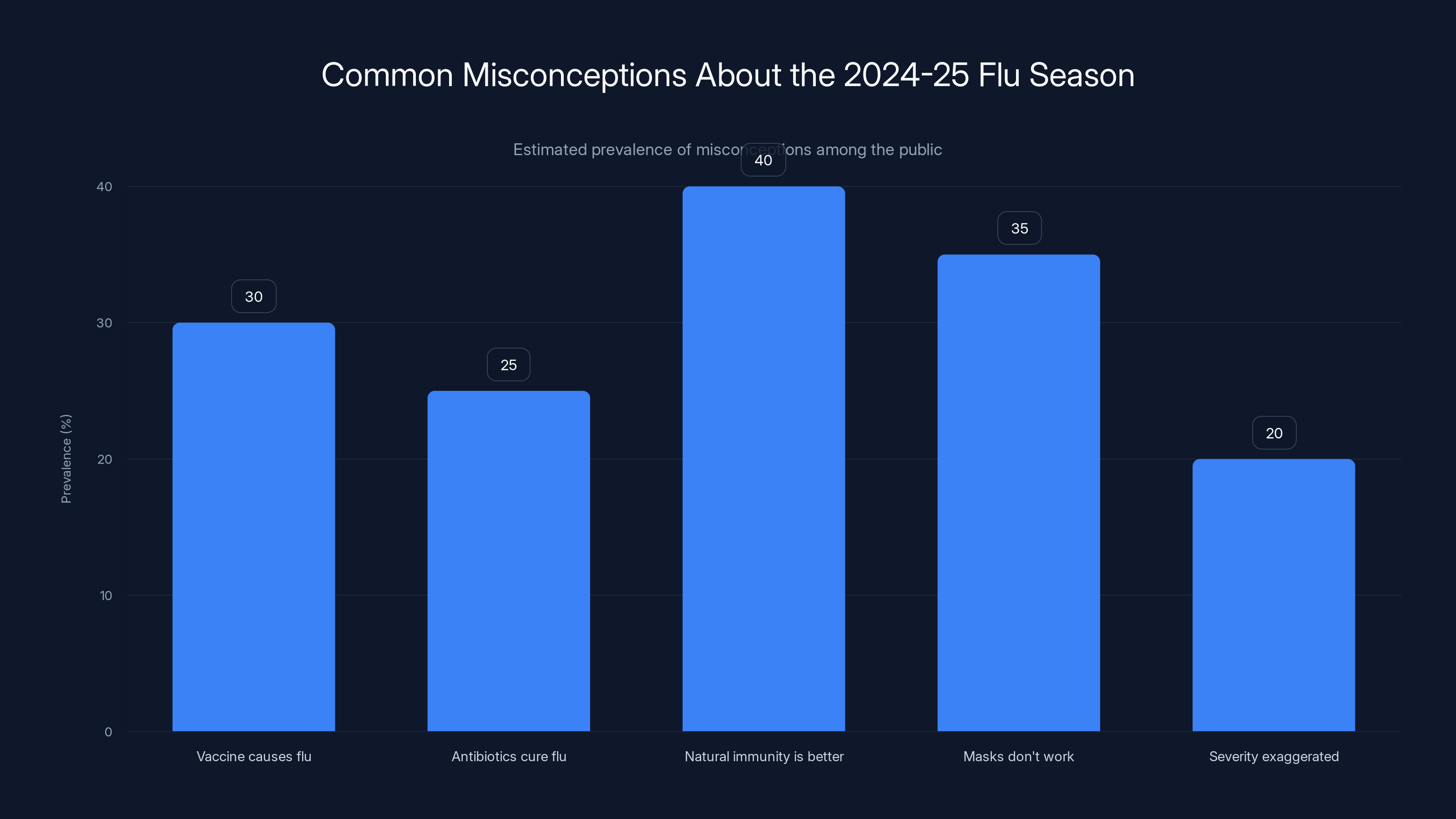

Estimated data shows that misconceptions about flu vaccines and natural immunity are most prevalent. Addressing these can improve public health outcomes. (Estimated data)

High-Risk Groups: Who Needs to Be Most Careful?

Influenza doesn't affect everyone equally. Age, underlying health conditions, pregnancy status, and occupation create different risk profiles.

Adults aged 65 and older face exponentially higher risk of severe disease and death from influenza. This isn't controversial—it's consistently demonstrated across decades of data. Immune function naturally declines with age, a process called immunosenescence. Older adults' vaccine responses are also typically weaker than younger adults' responses, though vaccination still provides substantial benefit.

Very young children (particularly those under age 5) also face higher risk. Their immune systems are still developing, and children under 6 months are too young for flu vaccination. Hospitalization rates in young children during severe flu seasons can be alarming.

People with chronic health conditions including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, and immune system disorders face higher complication rates. The flu can destabilize these conditions and trigger serious exacerbations.

Pregnant women, particularly those in the second and third trimester, have been documented to experience more severe influenza illness compared to non-pregnant women. The hormonal changes and physical changes of pregnancy alter immune function. Additionally, infants born to vaccinated pregnant women receive passive immunity through antibodies transferred across the placenta, providing protection in the vulnerable first months of life.

Healthcare workers and other people who work with vulnerable populations (teachers, daycare workers, nursing home staff) face exposure and have ethical obligations to reduce transmission.

Vaccination Strategy: Timing, Effectiveness, and Best Practices

Getting vaccinated sounds straightforward, but the actual strategy matters for optimal timing and effectiveness.

The CDC recommends flu vaccination from October through November, before the season peaks. In 2025, given the earlier emergence of subclade K, getting vaccinated earlier in the fall was advisable. Immunity develops over approximately 10-14 days after vaccination, so timing your shot to be protected before peak transmission is logical.

One vaccine dose is typically sufficient for most adults. However, children who have never been vaccinated before should receive two doses, spaced 28 days apart, during their first year of vaccination. This two-dose regimen gives their immune systems a stronger training stimulus.

Multiple vaccine options exist. Traditional flu vaccines are inactivated (containing killed virus) and come in different formulations: standard-dose, high-dose (for older adults), cell-based, egg-free, and recombinant. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), administered as a nasal spray, is an option for some healthy children and adults. Each formulation has specific indications and contraindications.

For older adults and those with weakened immune systems, high-dose vaccines provide stronger immune responses. These contain four times the antigen (the component that trains the immune system) compared to standard vaccines.

One critical point: vaccination does not guarantee you won't get the flu. What it does guarantee, with substantial probability, is that if you do get infected, you're much less likely to develop severe illness requiring hospitalization. This distinction is crucial for managing expectations.

People sometimes get mild influenza-like symptoms within days of vaccination. This isn't the flu—it's the immune system responding to the vaccine. The flu vaccine does not contain live virus capable of causing infection.

Vaccination reduces severe outcomes by 70-75% in children and 30-40% in adults against Subclade K. Estimated data based on real-world studies.

Antiviral Medications: Your Second Line of Defense

If you develop influenza despite vaccination, antiviral medications can reduce the severity and duration of illness when started early.

Two main antiviral medications are available: oseltamivir (Tamiflu, oral) and baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza, oral). Both work by inhibiting the neuraminidase protein on the virus surface, which the virus needs to escape from infected cells and spread to new cells. By blocking this, antivirals reduce viral replication rate.

The critical factor is timing. These medications are most effective when started within 48 hours of symptom onset. If you wait until day three of illness, the antiviral benefit is minimal because viral replication has already peaked. This is why symptoms warrant prompt evaluation rather than waiting to see if you'll improve on your own.

Studies show that antiviral treatment reduces the duration of fever by approximately one day and reduces the risk of complications including pneumonia. For high-risk individuals (older adults, pregnant women, people with chronic conditions, hospitalized patients), the complications prevention alone can be substantial.

Antivirals don't cure influenza—they modestly reduce viral replication. Your immune system still does most of the work fighting the virus. But that marginal improvement can mean the difference between a bad week of illness and pneumonia requiring hospitalization.

Some concern has been raised about antiviral resistance. If antivirals are overused or misused, the virus can develop resistance, reducing their effectiveness. To minimize this risk, antivirals should be reserved for confirmed influenza in high-risk patients or people who develop severe illness, not given prophylactically or for suspected mild illness.

Daily Prevention Measures: The Unglamorous Foundation

Vaccination gets most of the attention, but daily infection control remains the unglamorous foundation of flu prevention.

Hand hygiene is extraordinarily effective and costs nothing. Influenza spreads through respiratory droplets and through surfaces contaminated with respiratory secretions. If an infected person sneezes and contaminates their hands, then touches a doorknob, they've left virus on that surface. If you touch that doorknob and then touch your face, you've just inoculated yourself with virus. Thorough handwashing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds disrupts the virus's lipid envelope and prevents infection even if virus-containing material is on your hands when you wash. The simple act of hand hygiene, done consistently, provides profound protection.

Respiratory hygiene involves coughing and sneezing into your elbow, not your hands. It requires carrying tissues and disposing of them immediately after use. These practices seem obvious but are routinely neglected. When someone sneezes in a meeting or on public transportation without covering their mouth, they're aerosolizing virus-containing droplets that settle on surfaces and in the air for minutes. Anyone nearby becomes potential infected person.

Masking in crowds has proven effective at reducing transmission. During the COVID-19 pandemic, data clearly demonstrated that mask-wearing reduces respiratory virus transmission. The effect is most dramatic when sick people wear masks—masks primarily protect others from the wearer rather than protecting the wearer from others. However, properly fitted respirators (N95 or KN95 masks) do provide some protection to the wearer.

Environmental controls including ventilation and humidity management suppress viral activity. Influenza viruses survive longer and spread more efficiently in cold, dry air compared to warm, humid air. This is partly why flu is seasonal. During winter months in temperate climates, outdoor air is cold and dry. When this air is brought indoors and heated, humidity drops further. Installing humidifiers or running ultrasonic diffusers to maintain indoor humidity in the 40-60% range can suppress influenza transmission.

Proper ventilation—bringing fresh outdoor air indoors rather than recirculating stale air—also matters. HEPA filtration and UV sterilization of recirculated air can reduce airborne virus concentration.

Staying home when sick is the single most effective transmission prevention. If you're sick, every person you contact becomes a potential new infected person. Responsible behavior when ill—staying home for at least 5 days after fever onset and 2 days after fever resolution—prevents exponential spread. I realize this is often impractical due to work policies and financial pressures, which is exactly why societal-level policies matter. Countries with paid sick leave show lower influenza transmission rates.

The 2024-25 flu season started earlier than usual, with significant activity by September, compared to the typical onset in November. Estimated data based on historical patterns.

Rest and Supportive Care: The Often-Overlooked Recovery Factor

When someone has influenza, supportive care matters more than most people realize.

Rest is not optional—it's a medical necessity. When your body is fighting a viral infection, immune cells are flooding to your respiratory tract, producing cytokines and antibodies, destroying infected cells. This process is metabolically expensive. Your immune system essentially borrows energy from other bodily functions. If you push through illness and go to work or exercise hard, you're competing with your immune system for energy resources. More importantly, you're amplifying viral spread to others.

Hydration is critical. Fever increases insensible fluid loss. If you're coughing and your respiratory tract is inflamed, maintaining adequate mucus hydration prevents mucus from thickening and blocking airways. Dehydration makes viral pneumonia more likely.

Nutrition matters but doesn't need to be elaborate. Your body needs adequate protein to make antibodies and immune cells. Vitamins and minerals support immune function. But studies show that elaborate special diets don't substantially improve flu recovery. Simple nutrition—soup, toast, fruit, adequate calories—suffices.

Sleep is when your immune system does much of its work. Cytokine production increases during sleep. Memory immune cell formation increases during sleep. People who skip sleep during infection have worse outcomes. This is yet another reason that modern "hustle culture" promoting working while sick is harmful at both individual and population levels.

Workplace and School Decisions During Outbreaks

When flu is widespread, decisions about work and school attendance matter at both individual and societal levels.

Traditionally, employers and schools have incentivized showing up sick through attendance bonus policies, perfect attendance awards, and the expectation that only severe illness warrants staying home. This creates a system where people with influenza show up to work and school, spreading virus to coworkers and classmates, who then bring it home to vulnerable family members.

During the 2024-25 season, some forward-thinking organizations modified attendance policies temporarily. They offered remote work options, didn't penalize sick days, and explicitly communicated that staying home while sick was expected and valued. These organizations reported lower overall absenteeism because fewer people got infected in the first place.

For schools, similar logic applies. Sending children with active influenza to school spreads virus to classmates, teachers, and other staff. Some of those people go home and expose elderly grandparents or immunocompromised family members. The CDC recommends excluding students with fever from school until they've been fever-free for 24 hours without fever-reducing medication.

The economic argument against this is straightforward: productivity losses from people working while sick are larger than productivity losses from absent sick people. Studies during COVID-19 showed that remote work capabilities actually increased productivity in many sectors.

When to Seek Medical Care: Red Flags and Timeline

Most people with influenza recover at home without medical intervention. However, some develop complications requiring urgent evaluation.

Seek immediate emergency care if experiencing difficulty breathing, chest pain, persistent high fever lasting more than 5 days despite treatment, confusion, loss of consciousness, or severe weakness. These suggest possible pneumonia or other serious complications.

Seek urgent care (within 24 hours) if you have underlying medical conditions and develop typical flu symptoms. You may be a candidate for antiviral treatment, which is most effective when started early.

Home management is appropriate for previously healthy people with straightforward flu symptoms who don't have the red flags mentioned above. Rest, hydration, over-the-counter fever reduction if desired, and monitoring for complications suffice.

The question about when to wait versus when to seek care hinges on your risk category. If you're in a high-risk group (older adult, pregnant, chronic conditions), earlier evaluation makes sense. If you're a healthy adult with mild illness, home management is appropriate with self-monitoring for warning signs.

One often-overlooked point: secondary bacterial pneumonia sometimes develops after initial viral symptoms improve. A person feels better for 2-3 days, then suddenly develops high fever, worsening cough, and shortness of breath. This biphasic course suggests possible secondary bacterial infection and warrants evaluation and likely antibiotics. The initial virus damages respiratory tissue, creating an environment where bacteria can establish infection.

International Variations: How Different Countries Responded

The 2024-25 flu season's severity varied internationally based on vaccination rates, public health resources, and population immunity patterns.

In the United Kingdom, where early data on vaccine effectiveness emerged, health authorities conducted rapid studies quantifying subclade K vaccine protection. They shared data publicly and communicated transparently about the reduced but still substantial vaccine protection. This transparency allowed both healthcare providers and the public to make informed decisions.

In Japan, early tracking of H3N2 variants provided detailed data on subclade K's prevalence. By November 2025, of the 23 H3 strains that could be fully sequenced from surveillance samples, 22 were subclade K. This rapid variant replacement pattern confirmed that subclade K had become the dominant strain. Japan's healthcare system responded by increasing vaccine availability and communicating the timing guidance emphasizing vaccination before winter peak.

In the United States, despite the severity designation, some regions experienced milder seasons than others. Southern states saw early peaks in September and October, while northern states saw peaks later. Vaccination campaigns ramped up in response to surge data.

Countries with robust public health infrastructure and centralized data collection tracked the outbreak in near real-time. Nations with fragmented health systems had delayed awareness of the severity.

What Experts Predict for Future Seasons

Influenza doesn't disappear. Even after the 2024-25 season ends, influenza will circulate globally indefinitely.

Based on historical patterns, several predictions seem reasonable. First, subclade K (or its descendants with further mutations) will likely remain the dominant H3N2 lineage for the next one to two years unless a substantially different variant emerges. Second, vaccine manufacturers will likely update the 2025-26 vaccine formulation to include subclade K. This will provide better antigenic matching and improved vaccine effectiveness.

Third, population immunity will rebuild through combination of vaccination and natural infection. The 2024-25 season essentially forced exposed people into one or two categories: vaccinated and infected, or infected and unvaccinated. Either way, their immune systems now have recent experience with subclade K. This creates a baseline of immunity even before the next season's vaccine.

Fourth, unless something dramatic changes (a shift in pandemic preparedness resources, climate change, or global health investment), seasonal influenza will continue following patterns of periodic moderate-to-severe seasons alternating with milder seasons.

Longer-term, virologists have discussed the possibility of a universal flu vaccine that protects against multiple influenza types and subtypes rather than requiring annual updates. Such vaccines remain in development but may eventually reduce the burden of seasonal influenza.

Common Misconceptions About the 2024-25 Flu Season

Misinformation spread alongside the virus, so addressing key misconceptions is worth doing explicitly.

Misconception 1: "The vaccine makes you get the flu." False. The inactivated flu vaccine contains killed virus and cannot cause infection. The live nasal spray vaccine contains weakened virus that replicates minimally and cannot cause disease. Some people experience mild symptoms from their immune system's response to the vaccine, but this is not the flu.

Misconception 2: "Antibiotics cure the flu." False. Antibiotics treat bacterial infections, not viral infections. Influenza is caused by virus, which antibiotics cannot touch. Inappropriate antibiotic use for viral infections drives antibiotic resistance, making antibiotics less effective for actual bacterial infections. Antivirals (oseltamivir, baloxavir), not antibiotics, are the medications that specifically treat influenza.

Misconception 3: "Natural immunity is better than vaccine immunity." Partially false. Natural infection does produce strong immunity to that specific strain, but infection carries risks of severe illness, complications, and death. Vaccination produces immunity without those risks. Some research suggests hybrid immunity (vaccination plus natural infection) may provide the strongest protection, but this doesn't mean you should deliberately get infected to boost immunity.

Misconception 4: "Masks don't work." False. Extensive scientific evidence documents that masks reduce respiratory virus transmission. N95 respirators provide substantial protection to the wearer. Surgical masks provide less protection to the wearer but substantial protection to others. The level of protection varies by fit, duration of wear, and variant virulence, but consistent mask-wearing during outbreaks demonstrably reduces transmission.

Misconception 5: "The government is exaggerating the severity to push vaccines." This reflects fundamental misunderstanding of how vaccine incentives work. Vaccine manufacturers make more money by producing more doses, not by having outbreaks. Public health officials benefit from lower disease burden, not higher. The severity data is independently verifiable through hospital admission records, mortality data, and surveillance systems that operate across multiple countries and organizations.

Preparing Your Home and Workplace for Future Flu Seasons

Lessons from the 2024-25 season suggest practical preparations for future outbreaks.

Home level: Maintain a stockpile of basic supplies—acetaminophen, ibuprofen, tissues, hand sanitizer, cleaning supplies—so you're not shopping while sick. Know where your nearest urgent care is. Discuss medication allergies and preferences with family members. Create a sick room or isolation plan if you have vulnerable household members.

Workplace level: Implement sick leave policies that don't penalize employees for illness. Offer remote work when possible. Provide hand sanitizer and respiratory etiquette information. Coordinate with occupational health about rapid vaccine availability when the season begins.

Community level: Support vaccine programs that reach low-income populations who face barriers to vaccination. Advocate for paid sick leave legislation so people aren't forced to choose between infection control and financial survival. Support investment in pandemic preparedness.

The Bottom Line: Managing Risk, Not Eliminating Fear

The "super flu" terminology was sensational and somewhat misleading, but the underlying concern was legitimate. The 2024-25 flu season was genuinely severe. The emergence of subclade K genuinely represented a challenge to existing vaccine effectiveness. Hospital systems were genuinely strained.

But here's the key insight: responding to legitimate risk with science-based measures is fundamentally different from responding to fear with panic. Vaccination plus basic infection control measures—hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, staying home when sick, antiviral treatment for high-risk patients—demonstrably reduced harm.

The 2024-25 season was an extension of traditional influenza, not a fundamental departure. Understanding this distinction is crucial. We don't need new categories of panic. We need reliable funding for annual vaccine updates, paid sick leave policies that let people make the right choice, and consistent messaging that treats respiratory viruses seriously without catastrophizing.

Subclade K is the flu. Take it seriously, get vaccinated, use preventive measures, and don't panic. That's the entire recommendation. Simple, evidence-based, and proven effective across decades of influenza seasons.

FAQ

What is subclade K?

Subclade K is a genetic variant of influenza A H3N2 that has multiple mutations in its hemagglutinin protein, allowing it to partially evade immunity from previous vaccination or infection. It emerged and began circulating widely in late August 2025, becoming the dominant H3N2 variant globally. The name "super flu" is media terminology; the official designation is subclade K.

How does subclade K differ from regular H3N2 flu?

Subclade K carries specific mutations in the hemagglutinin protein that make it antigenically distinct from earlier H3N2 variants. This means your immune system's antibodies from prior flu shots or previous infections are less effective at recognizing and attacking subclade K compared to earlier variants. The virus itself isn't more deadly—it's simply better at partially escaping existing immunity, allowing it to spread more widely.

Are the current flu vaccines effective against subclade K?

Yes, but with reduced effectiveness compared to perfectly matched vaccines. Studies from the UK found that vaccines provided 70-75% protection against hospitalization in children and 30-40% protection in adults. This means vaccinated people were still substantially protected against severe outcomes even though the vaccine wasn't perfectly matched to the variant. Any protection against hospitalization is meaningful during a severe season.

Why did the 2024-25 flu season start so early?

Multiple factors contributed: suppressed flu transmission during COVID-19 lockdowns left a large portion of the population with lower baseline immunity, particularly children; heat waves compromised immune function; and subclade K's ability to evade existing immunity allowed it to spread faster. The combination created conditions for earlier and more extensive transmission than typical seasons.

What should I do if I think I have the flu?

If you have fever, cough, body aches, and sore throat that came on suddenly, you likely have influenza. Stay home to avoid transmitting to others. Rest, drink fluids, and monitor your symptoms. If you're in a high-risk group (older than 65, pregnant, chronic medical conditions) or develop warning signs like difficulty breathing or chest pain, contact a healthcare provider promptly—antiviral medications like oseltamivir or baloxavir are most effective when started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

Can I get the flu vaccine if I'm allergic to eggs?

Yes. Modern flu vaccines come in non-egg formulations including cell-based and recombinant options. Contact your pharmacist or healthcare provider about these alternatives rather than skipping vaccination due to egg allergy. The protection is worth the accommodation.

Is the flu vaccine safe during pregnancy?

Absolutely. The inactivated flu vaccine is safe during all trimesters of pregnancy and is explicitly recommended. Beyond protecting the pregnant person, antibodies cross the placenta and provide protection to infants during the vulnerable first months of life when they're too young for their own vaccination.

How long should I stay home if I have the flu?

The CDC recommends staying home for at least five days after fever onset or until you've been fever-free for 24 hours without using fever-reducing medications, whichever is longer. After you can return to work or school, continue practicing respiratory hygiene and avoiding close contact with vulnerable people for several days. Cough can persist for weeks after fever resolves, but it doesn't necessarily mean active viral shedding.

Can I get both COVID-19 and flu vaccines at the same time?

Yes, you can safely receive COVID-19 and flu vaccines during the same visit at different injection sites. They don't interfere with each other's effectiveness. This is convenient timing since both respiratory viruses circulate during fall and winter.

Will the flu vaccine protect me from getting sick entirely?

No. Vaccines reduce risk of infection and severity if you do get infected, but they don't eliminate risk completely. Think of the vaccine as training your immune system to respond faster and more effectively. If you're exposed to the virus, your trained immune system controls the infection faster, reducing viral load and severity. Many vaccinated people still get infected but experience milder illness and lower risk of complications.

Conclusion: Learning from a Severe Season

The 2024-25 flu season will be remembered as one of the more challenging recent seasons. The emergence of subclade K, the suppressed immunity from years of COVID-19 isolation, and the convergence of multiple environmental factors created conditions for early and severe transmission. But the response—vaccination programs, antiviral treatment, and public health messaging—ultimately prevented the severe outcomes we would have seen without those interventions.

What's most important to understand going forward is that this is how seasonal influenza works. Viruses constantly evolve. Every few years, a particularly transmissible variant emerges and spreads widely. Some seasons are mild, others are severe, and patterns aren't entirely predictable. This is the reality of living with an endemic respiratory virus.

The tools we have—vaccines, antivirals, infection control measures, and public health infrastructure—are genuinely effective. They don't make influenza disappear, but they meaningfully reduce harm. The key is using these tools consistently and equitably rather than responding reactively to crisis conditions.

Vaccinate before the season, practice hand hygiene, stay home when sick, and seek care when warranted. These simple actions, collectively implemented across a population, transform severe seasons into manageable ones. That's not fear-based thinking—it's evidence-based risk management. And that's ultimately the lesson of subclade K: not that we face a new threat requiring panic, but that we have proven methods for managing the threats we've always faced.

Key Takeaways

- Subclade K is a H3N2 variant with mutations enabling partial immune escape, not a fundamentally new threat requiring panic

- The 2024-25 season was the most severe since 2017-18 with 87.3% of US regions experiencing active epidemics simultaneously

- Existing vaccines still provided 70-75% protection against hospitalization in children and 30-40% in adults despite reduced antigenic match

- Combination of suppressed population immunity from COVID-19 lockdowns and heat waves created conditions for earlier and faster transmission

- Science-based prevention—vaccination, hand hygiene, masking in crowds, staying home when sick, and antivirals for high-risk patients—meaningfully reduced harm

![Super Flu (H3N2 Subclade K): What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/super-flu-h3n2-subclade-k-what-you-need-to-know-2025/image-1-1767350145266.jpg)